Collaborative Problem Solving: What It Is and How to Do It

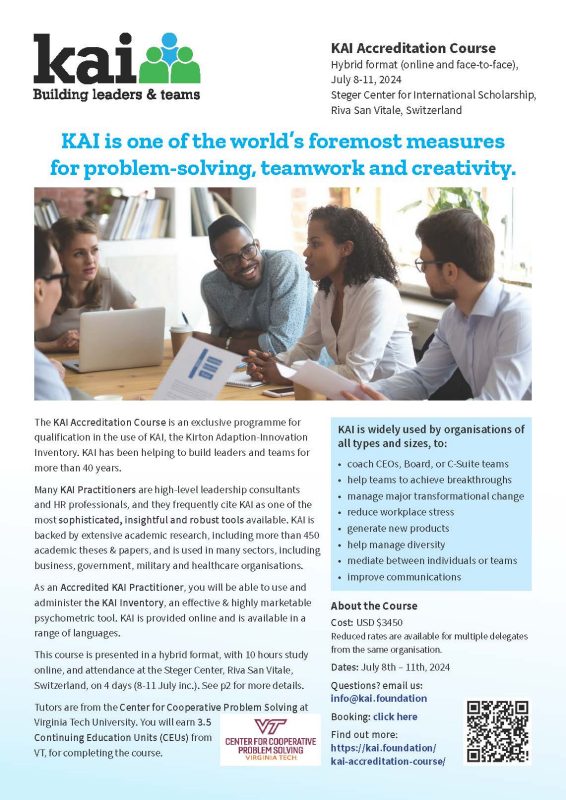

What is collaborative problem solving, how to solve problems as a team, celebrating success as a team.

Problems arise. That's a well-known fact of life and business. When they do, it may seem more straightforward to take individual ownership of the problem and immediately run with trying to solve it. However, the most effective problem-solving solutions often come through collaborative problem solving.

As defined by Webster's Dictionary , the word collaborate is to work jointly with others or together, especially in an intellectual endeavor. Therefore, collaborative problem solving (CPS) is essentially solving problems by working together as a team. While problems can and are solved individually, CPS often brings about the best resolution to a problem while also developing a team atmosphere and encouraging creative thinking.

Because collaborative problem solving involves multiple people and ideas, there are some techniques that can help you stay on track, engage efficiently, and communicate effectively during collaboration.

- Set Expectations. From the very beginning, expectations for openness and respect must be established for CPS to be effective. Everyone participating should feel that their ideas will be heard and valued.

- Provide Variety. Another way of providing variety can be by eliciting individuals outside the organization but affected by the problem. This may mean involving various levels of leadership from the ground floor to the top of the organization. It may be that you involve someone from bookkeeping in a marketing problem-solving session. A perspective from someone not involved in the day-to-day of the problem can often provide valuable insight.

- Communicate Clearly. If the problem is not well-defined, the solution can't be. By clearly defining the problem, the framework for collaborative problem solving is narrowed and more effective.

- Expand the Possibilities. Think beyond what is offered. Take a discarded idea and expand upon it. Turn it upside down and inside out. What is good about it? What needs improvement? Sometimes the best ideas are those that have been discarded rather than reworked.

- Encourage Creativity. Out-of-the-box thinking is one of the great benefits of collaborative problem-solving. This may mean that solutions are proposed that have no way of working, but a small nugget makes its way from that creative thought to evolution into the perfect solution.

- Provide Positive Feedback. There are many reasons participants may hold back in a collaborative problem-solving meeting. Fear of performance evaluation, lack of confidence, lack of clarity, and hierarchy concerns are just a few of the reasons people may not initially participate in a meeting. Positive public feedback early on in the meeting will eliminate some of these concerns and create more participation and more possible solutions.

- Consider Solutions. Once several possible ideas have been identified, discuss the advantages and drawbacks of each one until a consensus is made.

- Assign Tasks. A problem identified and a solution selected is not a problem solved. Once a solution is determined, assign tasks to work towards a resolution. A team that has been invested in the creation of the solution will be invested in its resolution. The best time to act is now.

- Evaluate the Solution. Reconnect as a team once the solution is implemented and the problem is solved. What went well? What didn't? Why? Collaboration doesn't necessarily end when the problem is solved. The solution to the problem is often the next step towards a new collaboration.

The burden that is lifted when a problem is solved is enough victory for some. However, a team that plays together should celebrate together. It's not only collaboration that brings unity to a team. It's also the combined celebration of a unified victory—the moment you look around and realize the collectiveness of your success.

We can help

Check out MindManager to learn more about how you can ignite teamwork and innovation by providing a clearer perspective on the big picture with a suite of sharing options and collaborative tools.

Need to Download MindManager?

Try the full version of mindmanager free for 30 days.

Or search by topic

Number and algebra

- The Number System and Place Value

- Calculations and Numerical Methods

- Fractions, Decimals, Percentages, Ratio and Proportion

- Properties of Numbers

- Patterns, Sequences and Structure

- Algebraic expressions, equations and formulae

- Coordinates, Functions and Graphs

Geometry and measure

- Angles, Polygons, and Geometrical Proof

- 3D Geometry, Shape and Space

- Measuring and calculating with units

- Transformations and constructions

- Pythagoras and Trigonometry

- Vectors and Matrices

Probability and statistics

- Handling, Processing and Representing Data

- Probability

Working mathematically

- Thinking mathematically

- Mathematical mindsets

- Cross-curricular contexts

- Physical and digital manipulatives

For younger learners

- Early Years Foundation Stage

Advanced mathematics

- Decision Mathematics and Combinatorics

- Advanced Probability and Statistics

Published 2011

Co-operative Problem Solving: Pieces of the Puzzle Approach

What is the pieces of a puzzle approach.

- You are responsible for your own work and behaviour

- You must be willing to help any group member who asks

- You may only ask the teacher for help if everyone in the group has the same question

- Risk taking - pupils are more likely ask questions of each other and put forward ideas in a small group situation, particularly with Rule 2 in place.

- Mathematical language development - usually the clues for the tasks are communicated with words. The group needs to negotiate their interpretation of the mathematical vocabulary. They also must talk to each other, listen to others and explain their ideas clearly.

- Peer coaching - pupils are able to clarify their understanding of mathematical concepts, correct misconceptions and test out ideas during the process of finding a collective solution to the problem.

- Teacher's role as a facilitator and observer - the independence of the groups gives the teacher freedom to move around the class, observe language and strategies, interact with groups as required and assess their progress.

- Effective learning - the tasks generally incorporate the manipulation of physical objects to produce a final product, which promotes the linking of verbal knowledge with visual imagery.

- Mixed ability class teaching - the features listed above combine to make this approach particularly suited to use with mixed ability classes. Every child should be able to make a contribution to the problem solving process, learn from the activity and have received attention from the teacher when needed.

Forming the Groups

There are, of course, many ways to organise children into groups. Unless the teacher has specific reasons for doing otherwise, a random mix method is best for this type of co-operative problem solving.

Random Mix by the Cards

Here is one way to achieve a random mix of pupils using a pack of ordinary playing cards. To form seven groups of four children, use all four card suits from one (Ace) to seven. Shuffle this pack and have each child choose a card. All the sevens form a group, all the sixes form a group and so on.

- Diamonds - team manager - responsible for assisting teacher to get group's attention at specified signal and reminding the group of the 'rules';

- Spades - equipment manager - responsible for collecting and returning materials, and ensuring all group members have access to the materials;

- Hearts - recorder - noting significant information, steps in solution, or preparation of finished product (such as the model, drawing or chart);

- Clubs - spokesperson - responsible for reporting the group's efforts and/or solutions

Lesson Structure

Introduction: This type of problem solving activity is well suited to developing and clarifying mathematical ideas that have already been introduced in other lessons. Therefore, in introducing the task to the class, the teacher can make links to previous work. If the mathematical vocabulary contained in the problem is of particular concern, then key terms should be revised.

Group work: The groups are formed and each child in a group is given one clue card. To maintain 'ownership' of the piece of information, the child may not physically give away the clue-card, but must be responsible for communicating the content to the group. Each pupil's role is now to work within his/her group to solve the puzzle, following the set of work rules. The teacher must also take care to follow these rules, and not take back responsibility for the task by interfering with the problem-solving processes or offering help before being asked by the whole group.

As always, it is advisable to have an extension question ready for a group that finishes before the others. It is also useful to have one or two 'extra' clues ready. These can be used to allow the inclusion of an extra group member, to give help to a group that is 'stuck', or to assist 'checking' when a group thinks it has finished the task.

Plenary - It is important for groups to report on their problem-solving processes as well as confirming the correctness of their end product. The teacher can use questions focus on particular issues and highlight points that have been observed during the session. For example:

Examples of Problems

(More than one answer is possible until Clues E & F are incorporated)

Stick Figures

Each group needs a handful of sticks, all of the same length - such as matches, ice-cream or lolly sticks, or drinking straws. The aim is to arrange some of the sticks to make either a single shape or shapes-combinations (depending on the level of complexity).

Fractured Shapes

The clues in this type of problem are non-verbal. In the example below, the squares are cut up by the teacher and each member of a group-of-four is given three pieces marked with the same letter. The aim is for the group to make four complete squares.

Each group needs a set of digit cards (two or three copies of the digits 0-9) and a template of the algorithm, in this example a two-column sum

Burns, M. (1992) About Teaching Mathematics , Maths Solution Publications: California Erickson, T. (1989) Get It Together, EQUALS: University of California.

Gould, P. (1993) Co-operative Problem Solving in Mathematics , Mathematical Association of N.S.W. Australia. ISBN 0-7310-1371-9 (Available through the Australian Association of Mathematics Teachers Catalogue code MAN466 - http://www.aamt.edu.au/ )

- Model UN Guide

- Sample Documents

Research Resources

- Publications

- Secretary-General’s Message

- Competitive Bargaining vs. Cooperative problem solving

- Overview of this Guide

- How Decisions are Made at the UN

- How a State Becomes a UN Member

- UN Emblem and Flag

- UN Structure

- The 4 pillars of the United Nations

- UN Family of Organizations

- History of the United Nations

- Agenda, Workplan, Documents and Rules of Procedure

- Leadership Positions in the GA

- Leadership Positions in the Secretariat

- Leadership Positions in the Security Council

- Selecting Candidates for Leadership Positions

- Oversight of the Conference - Things to Consider

- Roles and Responsibilities of Elected Officials

- Delegate Preparation

- Pre-Conference

- During the Conference

- Action Phase: Making Decisions

- Adoption of Agenda and Work Programme

- Discussion Phase -- General Debate

- Opening and Closing of Plenary

- Plenary vs. Committee Meetings

- Differences Between GA Rules and some Model UN Rules of Procedure

- Significance of Groups

- The Purpose of Consultations

- General Considerations and Denationalization

- Procedural Roles of the Chairman: A Step-by-Step

- Substantive Role of the Chair

- The Chair's Activities in Guiding the Work of a Committee

- Drafting Resolutions

- Characteristics of Winning Proposals

- Fundamentals of Negotiation

- Making Consultations Happen

- The Process of Negotiation

- Groups of Member States

- Changing Audience and Cultural Sensitivity

- Engaging the Audience

- Forms of Address

- Preparation, Purpose and Structure

- General Information about the United Nations

- United Nations General Assembly

- United Nations Security Council

- United Nations Documents

- Other Online Resources

Competitive Bargaining vs. Cooperative Problem-Solving

One of the biggest challenges of negotiation is that there are two different approaches that call for opposite strategies: competitive bargaining and cooperative problem-solving. This section gives an overview of both approaches and provides a rationale for why only one of them is appropriate for international conferences.

Competitive Bargaining

Historically, the word negotiation means “business,” and negotiation has a major role in business transactions.

The crudest form of negotiation in an international conference resembles crude commercial negotiations, for example, when you are trying to buy or sell a second-hand car and the only point at issue is the price. In that case, the buyer wants to pay as little as possible, while the seller wants to receive as much as possible. A gain by one party means an equal loss by the other. This type of negotiation is sometimes referred to as “competitive bargaining.” It has been extensively studied over the centuries by traders everywhere and, more recently, in business schools.

You probably already understand this form of negotiation. The essential feature is that each party receives something that they accept as the outcome of the negotiation. At the simplest, they would receive equal shares; but the issues before international conferences are generally far too complex for that and the needs and capabilities of the nations concerned are too varied for any simple equilibrium. Instead, at the international level, the balance to be found is between trade-offs, in which not only the quantity but also the nature of what different parties receive is different.

Each party is concerned primarily to maximize its own gains and minimize the cost to themselves.

Then some important tactical principles come to the fore:

- Always ask for more than you expect to get. Think of some of the things asked for as “negotiating coin” that you can trade away in order to achieve your aim. You can also assume that the other party does not expect to get everything they ask for and that some of their requests are only negotiating coin.

- You might even start by demanding things you do not really hope to achieve, but which you know other parties strongly oppose. By doing so, you may hope that the other parties will make concessions to you just to refrain from pressing such demands.

- Always hide your “bottom line.” Because the other party’s aim is to concede to you as little as possible, you may get more if they are not aware of how little is acceptable to you.

- Take early and give late. Negotiators often undervalue whatever is decided in the early part of the negotiation and place excessive weight on whatever is agreed towards the end of the negotiation.

- As the negotiation progresses, carefully manage the “concession rate.” If you “concede” things to the other party too slowly, they many lose hope of achieving a satisfactory agreement; but if you “concede” too fast, they could end up with more than you needed to give them.

- The points at issue are seen as having the same worth for both sides—although they rarely do.

Precepts of this kind can readily generate a competitive or even combative spirit and encourage negotiators to consider a loss by their counterparts as a gain for themselves. It should be evident that such sentiments at the international level are harmful to relations and thus to the prospects of cooperation and mutual tolerance.

Cooperative Problem-Solving

An entirely different style of negotiation is more common in international conferences than “competitive bargaining,” both because it is generally more productive and is widely seen as more appropriate in dealings between representatives of sovereign States. This style of negotiation starts from the premise that you both have an interest in reaching agreement and therefore an interest in making proposals that the other is likely to agree to. In other words, each has an interest in the other(s) also being satisfied.

Achieving your objective requires that you also work to achieve the objectives of the other party (or parties)—to the extent that such effort is compatible with your objectives. The same applies to your counterpart(s): it is in their interest to satisfy you to the maximum extent possible. This makes negotiation a cooperative effort to find an outcome that is attractive to all parties.

To succeed in this type of negotiation, principles apply which are quite contrary to those that apply in “competitive bargaining,” namely:

- It is important not to request concessions from the other side that you know are impossible for them. If you do so, they will find it difficult to believe that you are genuinely working for an agreement.

- It is in your interest that the other party should understand your position. Indeed, perhaps they should even know your “bottom line.” If they understand how close they are to that “bottom line” on one point, they will also understand the necessity to include other elements that you value to give you an incentive to agree.

- Sometimes it is in your interest to “give” a lot to the other side early in the negotiation process to give them a strong incentive to conclude the negotiation and therefore “give” you what you need to be able to reach agreement.

- The “concession rate” may not be important.

- There is a premium on understanding that the same points have different values for different negotiators and on finding additional points on which to satisfy them.

- The Chair's Activities in Guiding the Work of a Committee

- ‹ Negotiation

- Characteristics of Winning Proposals ›

Model United Nations

- How to Organize a MUN Conference

- Get the Model UN Guide Book

- Frequently Asked Questions

Updates from the UN

- Security Council

- General Assembly

- Sustainable Development

- Human Rights

- UN Member States

- UN Documents

- UN iLibrary

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

Youth Opportunities

- Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- UN Volunteers

- United Nations Academic Impact

Center for Cooperative Problem Solving

Developing leaders and teams.

Individuals associated with the Center for Cooperative Problem Solving are working to advance the teaching, research, and outreach of Adaption-Innovation (A-I) theory and the corresponding measure, Kirton’s Adaption-Innovation Inventory (KAI).

Upcoming Events

Apply for the next KAI Accreditation Course, online, April 15-26.

Apply for the Switzerland KAI Accreditation Course, July 8-11.

For More Information email us at [email protected]

Encyclopedia of Couple and Family Therapy pp 1–11 Cite as

Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS)

- Benjamin Rosen 4

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 24 November 2020

37 Accesses

Collaborative and Proactive Solutions (CPS)

Introduction

The Collaborative Problem Solving model (CPS) was developed by Dr. Ross Greene and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry. The model was created as a reconceptualization of the factors that lead to challenging or oppositional behaviors, and a shift in the targets of intervention for these behaviors. Dr. Greene published the book The Explosive Child in 1998, which was the first detailed description of CPS. Multiple research studies (detailed below) have followed in the time since the book’s publication.

In the subsequent years there was a split between Dr. Greene and Massachusetts General Hospital. Massachusetts General Hospital has continued its work on CPS via the “Think:Kids” program under the direction of Dr. Stuart Ablon, who had previously collaborated with Dr. Greene. Dr. Greene has founded a nonprofit organization called “Lives in the Balance” to further his work on CPS, which...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Becker, K., Chorpita, D., & Daleiden, B. (2011). Improvement in symptoms versus functioning: How do our best treatments measure up? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38 (6), 440–458.

Article Google Scholar

Bill of Rights for Behaviorally Challenging Kids. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.livesinthebalance.org/bill-rights-behaviorally-challenging-kids

Drilling Cheat Sheet. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.livesinthebalance.org/sites/default/files/Drilling%20Cheat%20Sheet%20060417.pdf

Greene, R. (2010). Collaborative problem solving. In Clinical handbook of assessing and treating conduct problems in youth (1st ed., pp. 193–220). New York: Springer.

Google Scholar

Greene, R., & Winkler, J. (2019). Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS): A review of research findings in families, schools, and treatment facilities. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22 (4), 549–561.

Greene, R. W., Ablon, J. S., Goring, J. C., Raezer-Blakely, L., Markey, J., Monuteaux, M. C., Henin, A., Edwards, G., & Rabbitt, S. (2004). Effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in affectively Dysregulated children with oppositional-defiant disorder: Initial findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72 (6), 1157–1164.

Ollendick, T. H., Greene, R. W., Austin, K. E., Fraire, M. G., Halldorsdottir, T., Allen, K. B., Jarret, M. A., Lewis, K. M., Smith, M. W., Cunningham, N. R., Noguchi, R. J. P., Canavera, K., & Wolff, J. (2016). Parent management training and Collaborative & Proactive Solutions: A randomized control trial for oppositional youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45 (5), 591–604.

Pollastri, A., Epstein, L., Heath, G., & Ablon, J. (2013). The collaborative problem solving approach: Outcomes across settings. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21 (4), 188–199.

PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Family Institute at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Benjamin Rosen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benjamin Rosen .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

The Family Institute at Northwestern, Evanston, IL, USA

Anthony Chambers

Douglas C. Breunlin

Section Editor information

The Family Institute at Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Jay L. Lebow Ph.D.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Rosen, B. (2020). Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS). In: Lebow, J., Chambers, A., Breunlin, D.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Couple and Family Therapy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15877-8_1160-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15877-8_1160-1

Received : 11 February 2020

Accepted : 12 February 2020

Published : 24 November 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-15877-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-15877-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Cooperative Group Problem Solving

- Cooperative Learning

Original module developed by Rebecca Teed , John McDaris , and Cary Roseth

- What is Cooperative Learning?

Cooperative Learning involves structuring classes around small groups that work together in such a way that each group member's success is dependent on the group's success. There are different kinds of groups for different situations, but they all balance some key elements that distinguish cooperative learning from competitive or individualistic learning.

Cooperative learning can also be contrasted with what it is not. Cooperation is not having students sit side-by-side at the same table to talk with each other as they do their individual assignments. Cooperation is not assigning a report to a group of students where one student does all the work and the others put their names on the product as well. Cooperation involves much more than being physically near other students, discussing material, helping, or sharing material with other students. There is a crucial difference between simply putting students into groups to learn and in structuring cooperative interdependence among students. Learn more about cooperative learning

- Why Use Cooperative Learning?

- Students who engage in cooperative learning learn significantly more, remember it longer, and develop better critical-thinking skills than their counterparts in traditional lecture classes.

- Students enjoy cooperative learning more than traditional lecture classes, so they are more likely to attend classes and finish the course.

- Students are going to go on to jobs that require teamwork. Cooperative learning helps students develop the skills necessary to work on projects too difficult and complex for any one person to do in a reasonable amount of time.

- Cooperative learning processes prepare students to assess outcomes linked to accreditation.

- How to Use Cooperative Learning

Cooperative learning exercises can be as simple as a five minute in class exercise or as complex as a project which crosses class periods. These can be described more generally in terms of low, medium, and high faculty/student time investment.

- Cooperative Learning Techniques

- Testimonials and Videos

- Bibliography of useful books and articles about cooperative learning.

- Web Resources which provide additional information on cooperative learning.

- Examples of ways to use cooperative learning in your classroom.

Next Page »

- Campus Living Laboratory

- ConcepTests

- Conceptual Models

- Web Resources

- References and Resources

- Earth History Approach

- Experience-Based Environmental Projects

- First Day of Class

- Gallery Walks

- Indoor Labs

- Interactive Lecture Demonstrations

- Interactive Lectures

- Investigative Case Based Learning

- Just in Time Teaching

- Mathematical and Statistical Models

- Peer Review

- Role Playing

- Service Learning

- Socratic Questioning

- Spreadsheets Across the Curriculum

- Studio Teaching in the Geosciences

- Teaching Urban Students

- Teaching with Data

- Teaching with GIS

- Teaching with Google Earth

- Teaching with Visualizations

- Undergraduate Research

- Using an Earth System Approach

- About this Site

- Accessibility

Citing and Terms of Use

Material on this page is offered under a Creative Commons license unless otherwise noted below.

Show terms of use for text on this page »

Show terms of use for media on this page »

- None found in this page

- Last Modified: February 26, 2024

- Short URL: https://serc.carleton.edu/10838 What's This?

Supporting physics teaching with research-based resources

- Expert Recommendations

Developed by: University of Minnesota Physics Education Research Group

Teaching Materials

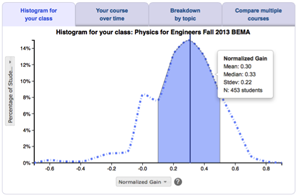

What? Students work in groups using structured problem-solving strategy to solve complex, context-rich problems that are too difficult to solve individually.

Why? Unlike earlier traditional "group learning", Cooperative Group Problem-Solving rewards both individual and team accomplishments and allows all group members to rotate leadership roles. If implemented well, this method promotes collaborative skills valued in most work settings.

Why not? Assigning students appropriately to achieve heterogenous grouping is challenging at the undergraduate level. It takes time and effort to construct tasks with clear expectations for both individual and group responsibilities, and to teach relevant interpersonal skills required for group success.

Student skills developed

- Conceptual understanding

- Problem-solving skills

- Making real-world connections

- Using multiple representations

Instructor effort required

Resources required.

- Tables for group work

The University of Minnesota has created a free online archive of context-rich problems , where you can find problems for many topics in introductory mechanics and electromagnetism to use with cooperative group problem-solving.

You can also use the cooperative group problem-solving approach with many other types of research-based activities .

- at least 1 of the "based on" categories

- at least 1 of the "demonstrated to improve" categories

- at least 1 of the "studied using" categories

Research Validation Summary

Based on research into:.

- theories of how students learn

- student ideas about specific topics

Demonstrated to Improve:

- conceptual understanding

- problem-solving skills

- beliefs and attitudes

- retention of students

- success of underrepresented groups

- performance in subsequent classes

Studied using:

- cycle of research and redevelopment

- student interviews

- classroom observations

- analysis of written work

- research at multiple institutions

- research by multiple groups

- peer-reviewed publication

- P. Heller, T. Foster, and K. Heller, Cooperative group problem solving laboratories for introductory classes , presented at the The changing role of physics departments in modern universities: International Conference on Undergraduate Physics Education, College Park, MD, 1996.

- P. Heller and M. Hollabaugh, Teaching Problem Solving Through Cooperative Grouping. Part 2: Designing Problems and Structuring Groups , Am. J. Phys. 60 (7), 637 (1992).

- P. Heller, R. Keith, and S. Anderson, Teaching Problem Solving Through Cooperative Grouping. Part 1: Group Versus Individual Problem Solving , Am. J. Phys. 60 (7), 627 (1992).

Compatible Methods

Similar method, physport data explorer.

Home | Expert Recommendations | Teaching Methods | Assessment | Workshops | Data Explorer | About | Help | Contact | Terms | Privacy | My Account

Pi Day is Giving Day: arXiv depends on donations to operate and keep science open for all. Give back to arXiv on 3.14.24!

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computation and Language

Title: greater than the sum of its parts: the role of minority and majority status in collaborative problem-solving communication.

Abstract: Collaborative problem-solving (CPS) is a vital skill used both in the workplace and in educational environments. CPS is useful in tackling increasingly complex global, economic, and political issues and is considered a central 21st century skill. The increasingly connected global community presents a fruitful opportunity for creative and collaborative problem-solving interactions and solutions that involve diverse perspectives. Unfortunately, women and underrepresented minorities (URMs) often face obstacles during collaborative interactions that hinder their key participation in these problem-solving conversations. Here, we explored the communication patterns of minority and non-minority individuals working together in a CPS task. Group Communication Analysis (GCA), a temporally-sensitive computational linguistic tool, was used to examine how URM status impacts individuals' sociocognitive linguistic patterns. Results show differences across racial/ethnic groups in key sociocognitive features that indicate fruitful collaborative interactions. We also investigated how the groups' racial/ethnic composition impacts both individual and group communication patterns. In general, individuals in more demographically diverse groups displayed more productive communication behaviors than individuals who were in majority-dominated groups. We discuss the implications of individual and group diversity on communication patterns that emerge during CPS and how these patterns can impact collaborative outcomes.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Download PDF

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

DIFFERENT LENSES, DIFFERENT PRACTICES, AND DIFFERENT OUTCOMES

Help kids solve the problems that are causing their concerning behavior…without shame, blame, or conflict.

WHERE COMPASSION AND SCIENCE INTERSECT

Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS) is the evidence-based, trauma-informed, neurodiversity affirming model of care that helps caregivers focus on identifying the problems that are causing concerning behaviors in kids and solving those problems collaboratively and proactively. The model is a departure from approaches emphasizing the use of consequences to modify concerning behaviors. In families, general and special education schools, inpatient psychiatry units, and residential and juvenile detention facilities, the CPS model has a track record of dramatically improving behavior and dramatically reducing or eliminating discipline referrals, detentions, suspensions, restraints, and seclusions. The CPS model is non-punitive, non-exclusionary, trauma-informed, transdiagnostic, and transcultural.

And this website is the hub of free resources on the CPS model.

WHAT YOU NEED TO GIVE KIDS WHAT THEY NEED

Parents & families, educators & schools, pediatricians & family physicians.

15 Main Street, Suite 200, Freeport, Maine 04032

Lives In the Balance All Rights Reserved. Privacy Policy Disclaimer Gift Acceptance Policy

Sign up for our Newsletter CPS Methodology Podcasts about the CPS Model Connect with our Community Research

Why We’re Here Meet the Team Our Board of Directors Higher Ed Advisory Board

Get in Touch Make a Donation

- PARENTS & FAMILIES

- EDUCATORS & SCHOOLS

- PEDIATRICIANS & FAMILY PHYSICIANS

- CPS WITH YOUNG KIDS

- WORKSHOPS & TRAININGS

- CPS PAPERWORK

- PUBLIC AWARENESS

- SCHOLARSHIPS

- BECOME AN ADVOCATOR

- RESOURCES FOR ADVOCATORS

- TAKE ACTION

- Get IGI Global News

- Language: English

- All Products

- Book Chapters

- Journal Articles

- Video Lessons

- Teaching Cases

Shortly You Will Be Redirected to Our Partner eContent Pro's Website

eContent Pro powers all IGI Global Author Services. From this website, you will be able to receive your 25% discount (automatically applied at checkout), receive a free quote, place an order, and retrieve your final documents .

What is Cooperative Problem Solving (CPS)

Related Books View All Books

Related Journals View All Journals

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

The Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Cooperative Agreement Program

The Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving (EJCPS) Cooperative Agreement Program provides financial assistance to eligible organizations working to address local environmental or public health issues in their communities. The program assists recipients in building collaborative partnerships with other stakeholders (e.g., local businesses and industry, local government, medical service providers, academia, etc.) to develop solutions to environmental or public health issue(s) at the community level.

The EJCPS Program requires selected applicants, or recipients, to use the EPA's Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Model to address local environmental or public health issues in a collaborative manner with various stakeholders such as communities, industry, academic institutions, and others. The case studies listed in the resources section below highlight some of the successful strategies of previous projects.

Is My Organization Eligible?

2023 selectees.

- Pre-Application Assistance Calls and Webinars

Eligible entities include:

- a community-based nonprofit organization (CBO); or

- a partnership of community-based nonprofit organizations *

* A partnership must be documented with a signed Letter of Commitment from the community-based nonprofit organization detailing the parameters of the partnership, as well as the role and responsibilities of the partnering community-based organizations.

EPA has selected 98 EJCPS awardees to receive a total of $43.8 million in Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funding for community-based nonprofit organizations to help underserved and overburdened communities across the country. Awardees will receive up to $500,000 in grant funding. EJCPS grants will fund a variety of projects to serve critical environmental justice communities and issues including wildfires, health impact assessments, air monitoring, indoor/outdoor air quality, food access, community planning, community revitalization, community agriculture, green jobs and infrastructure, emergency preparedness and planning, toxic exposures, water quality, and healthy homes projects, wood burning stove replacement, solar panel installation, assessments, and water sampling and monitoring. Twenty-three projects will take place in rural areas and 60 will address climate change, disaster resiliency, and/or emergency preparedness.

Learn more about the 2023 EJCPS Selectees (pdf) (442.2 KB)

Read the press release announcing the 2023 EJCPS Selectees

This competition was launched in order to meet the goals and objectives of two Executive Orders ( EO 14008 and EO 13985 ) issued by the Biden Administration that demonstrate the EPA’s and Administration’s commitment to achieving environmental justice and embedding environmental justice into Agency programs.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act created the Environmental and Climate Justice block grant program in section 138 of the Clean Air Act (CAA) and provided EPA with $2.8 billion in grant funding for the program for projects to benefit communities with environmental justice concerns.

Review the Amended EJCPS Request for Applications for specific guidance and eligible project examples. (pdf) (1.2 MB)

For more information, please contact Jacob Burney .

- Informational Video on the Environmental and Climate Justice Communities Grants Program

Pre-Application Assistance Calls & Webinars

Applicants were invited to participate in conference calls and webinars with EPA to address questions about the CPS Program and this solicitation.

EJCPS Live Webinars

- Passcode: 46598050

- Slides from the February 2, 2023 EJCPS webinar (pdf) (817 KB)

- Passcode: 85564988

- Slides from the January 24, 2023 EJCPS webinar (pdf) (780.1 KB)

If EPA schedules any additional assistance webinars, details will be posted here and sent out by the EPA-EJ Listserv and the EPA Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights X account .

- Frequently Asked Questions for the FY2023 EJCPS opportunity (pdf) (216 KB)

- Review previous project descriptions by state or review project descriptions by year .

- Review prior year requests for applications (RFAs).

- EPA’s Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Model Guide (pdf) (1.2 MB) A guide to EPA's EJ Collaborative Problem-Solving program.

- Case Studies from the Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Program (pdf) (3.6 MB) In-depth descriptions of five successful CPS awards.

- Fact Sheet on Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Cooperative Agreement Program (pdf) (405.7 KB)

- Environmental Justice Program Funded Projects (2014 to 2020).

- The Power of Partnerships : 45-minute video of EPA's EJ CPS Model at work in Spartanburg, SC featuring interviews of key EJ stakeholders and community members explaining their roles in successfully addressing EJ concerns in the area.

- Environmental Justice (EJ) Home

- Learn About Environmental Justice

- Equity Action Plan

- Grants and Resources

- National Environmental Justice Advisory Council

- White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council

- EJ in Your Community

- EJ and National Environmental Policy Act

- EJ and Title VI

- EJ for Tribes and Indigenous Peoples

- Equitable Development and EJ

- Community Voices on EJ

Kids with challenging behavior are tragically misunderstood. It’s time for a more compassionate and effective approach.

About Collaborative Problem Solving ®

At Think:Kids, we recognize that kids with challenging behavior don’t lack the will to behave well. They lack the skills to behave well.

Our Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) approach is proven to reduce challenging behavior, teach kids the skills they lack, and build relationships with the adults in their lives.

Anyone can learn Collaborative Problem Solving, and we’re here to show you how.

73% reduction in oppositional behaviors during school.

Parents report improvements in parent-child interactions.

86% average reduction in physical restraint.

reduction in school office referrals.

Significant improvements in children’s executive functioning skills.

71% fewer self-inflicted injuries.

6 out of 10 teachers report reduced stress.

Significant reductions in parents’ stress.

60% of children exhibited improved behavior

Subscribe to our newsletter, privacy overview.

To meet East Ramapo's challenges, we must embrace collaborative problem-solving

3-minute read.

Regarding "East Ramapo monitors seek transportation cuts as banks refuse to lend money to district," lohud.com, Feb. 19:

We find it necessary to provide an additional and more accurate perspective on the situation as the sponsors of legislation aimed at addressing the unique challenges faced by the East Ramapo School District.

Rather than fostering a constructive dialogue, we contend that the article prioritized blame over collaborative problem-solving, which is what is needed to address this situation.

It is crucial to acknowledge the distinctive nature of the East Ramapo School District. With approximately 33,000 private and 11,000 public school students, it is a demographic unparalleled in any other district across the state. This uniqueness requires tailored solutions rather than generic approaches to ensure the well-being of all students.

While it is true that budget votes in East Ramapo have faced challenges, it is counterproductive to castigate the voters. The voters may not want higher taxes. Does anyone? The voters may feel they are not getting the services for which they are eligible. Our offices hear this from struggling parents frequently.

Lecturing the voters has proven ineffective, and doing so only prolongs the issue indefinitely. We must shift our focus towards collaborative problem-solving to benefit the 11,000 public school students in the district.

The explosive cost of transportation is swamping the budget and negatively impacting the educational experience of public-school students. Despite this, we firmly disagree with the proposal to cut busing! In our opinion, and the opinions of many, that will only worsen the situation and result in more failed budgets.

Past state interventions have not fixed the problem, so why not try something different? With that in mind, we advocate for a more proactive and equitable solution. Recognizing the transportation law imposed by New York State requiring transportation for both public and private schools, we have introduced legislation in both legislative chambers (Senate Bill S4510A and Assembly Bill A4020A). This legislation aims to transfer the responsibility for transportation costs from the district to the state.

We urge members from both parties to support and sign onto this legislation and encourage the New York State Education Department and the Board of Regents to lend their support. By doing so, we can collectively address the hurdles the East Ramapo School District faces and work towards a positive resolution that will fix the problem.

State Sen. Bill Weber represents District 38.

Assemblyman Karl Brabenec, the minority whip, represents District 98 .

Automated Collaborative Problem Solving Through Dialogues Between Specialized Large Language Models

Sean mondesire.

- SMCS Members: Free IEEE Members: $11.00 Non-members: $15.00 Length: 00:14:47

Automated Collaborative Problem-Solving through Dialogues between Specialized Large Language Models Dr. Sean Mondesire, School of Modeling Simulation and Training, the University of Central Florida (UCF) A person wearing glasses and a suit Description automatically generatedDr. Sean Mondesire is an Assistant Professor at the University of Central Florida's (UCF) School of Modeling, Simulation, and Training (SMST). He is a part of the Knights Digital Twin Initiative, directs the Human-centered Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (HAIL), and co-directs UCF’s Advanced Research Computing Center (ARCC) for high-performance computing. His research specialties are machine learning and big data analytics for real-time recommender systems and autonomous decision-making at scale. Abstract: This presentation examines the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) in dialogic self-play for complex problem-solving. By assigning specialized roles to each LLM, we explore their capacity to tackle logic puzzles and improve NPCs in serious gaming. We focus on the efficiency of these AI dialogues in discovering innovative solutions and research questions, highlighting minimal human-in-the-loop approaches. This method demonstrates significant time-saving and creative potential, offering new insights into autonomous AI collaboration and its impact on advancing AI research and applications.

More Like This

- SMCS Members: Free IEEE Members: $11.00 Non-members: $15.00

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) At Think:Kids, we recognize that kids with challenging behavior don't lack the will to behave well.They lack the skills to behave well. Our Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) approach is proven to reduce challenging behavior, teach kids the skills they lack, and build relationships with the adults in their lives.

The findings show that (1) collaborative problem solving is an effective teaching approach to foster students' critical thinking, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.82, z = 12.78, P ...

Cooperative Problem Solving at it is used by many professors teaching thousands of students and different institutions. Cooperative Problem Solving can be used as the major focus of a course, or as a supplement in combination with other teaching tools. What is Cooperative Problem Solving (CPS)? This book is designed to answer this question.

Collaborative problem solving (CPS) has been receiving increasing international attention because much of the complex work in the modern world is performed by teams. However, systematic education and training on CPS is lacking for those entering and participating in the workforce. In 2015, the Programme for International Student Assessment ...

What is collaborative problem solving? As defined by Webster's Dictionary, the word collaborate is to work jointly with others or together, especially in an intellectual endeavor.Therefore, collaborative problem solving (CPS) is essentially solving problems by working together as a team. While problems can and are solved individually, CPS often brings about the best resolution to a problem ...

Collaborative problem solving (CPS) is a critical and necessary skill used in education and in the workforce. While problem solving as defined in PISA 2012 (OECD, 2010) relates to individuals working alone on resolving problems where a method of solution is not immediately obvious, in CPS, individuals

Defining collaborative problem solving. Collaborative problem solving refers to "problem-solving activities that involve interactions among a group of individuals" (O'Neil et al., Citation 2003, p. 4; Zhang, Citation 1998, p. 1).In a more detailed definition, "CPS in educational setting is a process in which two or more collaborative parties interact with each other to share and ...

The PISA 2015 Collaborative Problem Solving assessment was the first large-scale, international assessment to evaluate students' competency in collaborative problem solving. It required students to interact with simulated (computer) in order to solve problems. These dynamic, simulated agents were designed to represent different profiles of ...

The complex research, policy and industrial challenges of the twenty-first century require collaborative problem solving. Assessments suggest that, globally, many graduates lack necessary ...

The content of this article is largely drawn from an Australian publication by Peter Gould that has been a source of many successful mathematics lessons for both children and student-teachers. It presents a style of problem-solving activity that has the potential to benefit ALL children in a class, both mathematically and socially, and is readily adaptable to most topics in mathematics curricula.

Cooperative problem solving with peers plays a central role in promoting children's cognitive and social development. This article reviews research on cooperative problem solving among preschool-age children in experimental settings and social play contexts.

Cooperative Problem-Solving. An entirely different style of negotiation is more common in international conferences than "competitive bargaining," both because it is generally more productive ...

Developing Leaders and Teams. Learn more about the center. Individuals associated with the Center for Cooperative Problem Solving are working to advance the teaching, research, and outreach of Adaption-Innovation (A-I) theory and the corresponding measure, Kirton's Adaption-Innovation Inventory (KAI).

The Collaborative Problem Solving model (CPS) was developed by Dr. Ross Greene and his colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital's Department of Psychiatry. The model was created as a reconceptualization of the factors that lead to challenging or oppositional behaviors, and a shift in the targets of intervention for these behaviors. ...

Students in two other classrooms worked only occasionally in groups. In the classrooms where cooperative learning was a regular practice, students engaged in group problem solving in mathematics two to four times each week. Often cooperative-learning sessions followed large-group introductions to topics.

Why Cooperative Group Problem Solving. Students in introductory physics courses typically begin to solve a problem by plunging into the algebraic and numerical solution -- they search for and manipulate equations, plugging numbers into the equations until they find a combination that yields an answer (e.g. the plug-and-chug strategy).

Each category includes a number of potential structures to guide the development of a cooperative learning exercise. For example, the category of problem-solving helps to develop strategic and analytical skills and includes exercises such as the send-a-problem, three-stay one-stray, structured problem solving, and analytical teams.

The University of Minnesota has created a free online archive of context-rich problems, where you can find problems for many topics in introductory mechanics and electromagnetism to use with cooperative group problem-solving. You can also use the cooperative group problem-solving approach with many other types of research-based activities.

Collaborative problem solving is a key skill for program managers, especially when dealing with complex and uncertain situations. It involves bringing together diverse perspectives, knowledge, and ...

Collaborative problem-solving (CPS) is a vital skill used both in the workplace and in educational environments. CPS is useful in tackling increasingly complex global, economic, and political issues and is considered a central 21st century skill. The increasingly connected global community presents a fruitful opportunity for creative and collaborative problem-solving interactions and solutions ...

1. Introduction It is widely believed that a group of cooperating agents engaged in problem solving can solve a task faster than either a single agent or the same group of agents working in ...

Collaborative & Proactive Solutions (CPS) is the evidence-based, trauma-informed, neurodiversity affirming model of care that helps caregivers focus on identifying the problems that are causing concerning behaviors in kids and solving those problems collaboratively and proactively. The model is a departure from approaches emphasizing the use of ...

What is Cooperative Problem Solving (CPS)? Definition of Cooperative Problem Solving (CPS): Is a way of social interaction where a group of autonomous entities work together to achieve a common goal. In the context of optimization problems, this situation can be seen as follows: the goal is to find the "best" solution for the problem at hand, while the "entities" can be thought as ...

The EJCPS Program requires selected applicants, or recipients, to use the EPA's Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Model to address local environmental or public health issues in a collaborative manner with various stakeholders such as communities, industry, academic institutions, and others. The case studies listed in the ...

About Collaborative Problem Solving ®. At Think:Kids, we recognize that kids with challenging behavior don't lack the will to behave well. They lack the skills to behave well. Our Collaborative Problem Solving® (CPS) approach is proven to reduce challenging behavior, teach kids the skills they lack, and build relationships with the adults ...

We must shift our focus towards collaborative problem-solving to benefit the 11,000 public school students in the district. The explosive cost of transportation is swamping the budget and ...

Solutions for the Community The University of Maryland Extension is a statewide, non-formal education system that provides resources and problem-solving assistance to citizens. Our areas of expertise include but are not limited to agricultural production and nutrient management, water quality, natural resources, food safety, nutrition and healthy lifestyles, youth development, volunteer ...

Automated Collaborative Problem-Solving through Dialogues between Specialized Large Language Models Dr. Sean Mondesire, School of Modeling Simulation and Training, the University of Central Florida (UCF) A person wearing glasses and a suit Description automatically generatedDr. Sean Mondesire is an Assistant Professor at the University of ...