Kindergarten Four Frame Program: Problem Solving and Innovating

- Belonging and Contributing

- Music and Movement!

- Demonstrating Literacy and Mathematics Behaviours

- Problem Solving and Innovating

- Parents & Friends

The learning encompassed by this frame supports collaborative problem solving and bringing innovative ideas to relationships with others.

Curriculum Expectations

This frame encompasses children's learning and development with respect to:

- exploring the world through natural curiosity, in ways that engage the mind, the senses, and the body;

- making meaning of their world by asking questions, testing theories, solving problems, and engaging in creative and analytical thinking;

- the innovative ways of thinking about and doing things that arise naturally with an active curiosity, and applying those ideas in relationships with others, with materials, and with the environment.

Check out our databases!

For login in information for our board resources and databases, please ask your LCI or teacher!

K-Gr. 6: Teacher Resources

I Love Computers!

Colour changing milk.

Fun to read

Check with your Learning Commons Informationist or public library to see if this title is available to borrow.

Fun Science for Kinders!

Computer Technology

All about COMPUTERS!!

Mouse Practice

Activities to help practice mouse manipulation.

Keyboarding Skills

Activities to practice keyboard skills and alphabet recognition.

iPads & Tablets

iPads & tablets ~ goals for JK/SK students:

-Use the iPad (Drag items across the screen, tap items on the screen)

-vocabulary development

-letter/number/shape/alphabet recognition

-expressive language/speech practice

- << Previous: Demonstrating Literacy and Mathematics Behaviours

- Next: Parents & Friends >>

- Last Updated: Nov 8, 2023 2:42 PM

- URL: https://vlc.ucdsb.ca/kindergarten

New Designs for School Teaching Kindergarteners Critical Thinking Skills: Lessons from Two Rivers Deeper Learning Cohort

Jeff Heyck-Williams with Chelsea Rivas and Liz Rosenberg Two Rivers Deeper Learning Cohort in Washington, D.C.

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

The stories of two kindergarten teachers illustrate the power of providing an opportunity for 5 and 6 year-olds to think critically.

I’ve argued elsewhere that yes, we can define, teach, and assess critical thinking skills , but I know what you are probably thinking. These skills are all good for middle and high school students and maybe upper elementary kids, but kindergarteners? However, I was in a kindergarten class recently where five and six year-olds were making evidenced-based claims and critiquing the arguments of each other. Kindergarteners were thinking critically!

Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., is wrapping up our second Deeper Learning Cohort. Twenty-four educators from schools across the city participated to learn how to deepen their students’ thinking through the use of thinking routines with aligned rubrics and performance assessments.

This group of dedicated teachers from prekindergarten through 8th grade gathered at convenings over the course of this past school year to explore what it means to help students think more deeply about what they are learning. Specifically, we learned about three thinking routines that provide a structure for helping students think critically and problem-solve. We dived into understanding how the language of rubrics can be used to define these constructs but have limitations when applied across multiple contexts. We developed understanding of performance task design and how that translates into the experiences we provide for students everyday. Finally, we learned how analyzing student thinking as exhibited in student work can be leveraged to deepen our students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills .

The power of this work has been highlighted for all of us as we saw kindergarten students demonstrate an ability to formulate reasoned arguments with specific support. The stories of two kindergarten teachers illustrate the power of providing both an opportunity for five and six year-olds to think critically and the structure to support that thinking.

Teaching Kindergarteners to Be Effective Reasoners

Chelsea Rivas, Kindergarten Teacher at Two Rivers Public Charter School

When Two Rivers invited educators to participate in a Deeper Learning Cohort last summer I jumped on the opportunity. I began working at Two Rivers in the fall of 2018 and had a lot to learn my first year about the “Two Rivers Way,” so I didn’t feel like I was able to dive into thinking routines in a way I wanted. This cohort allowed me to do just that!

We began our journey by learning about and experiencing the thinking routines and then choosing one to focus on all year with our class. As a kindergarten teacher, I decided I wanted my students to grow into people who reason effectively, so I chose to focus on the “Claim-Support-Question” routine.

I introduced the effective reasoning thinking routine of Claim-Support-Question with a fun think-aloud. I showed a portion of a picture on our board and had students make “claims,” or guesses, as to what the whole picture might be. I then had them support their claim with evidence from the picture and their own personal experience. Last, I showed my students how we can challenge or question our claim by saying what someone else might think.

My students loved this challenge so much that we made it part of our morning routine two to three times a week. Once students became comfortable using this routine in the context of the mystery picture of the day, I extended the use of this routine to reading literature. I modeled making claims and using evidence from the text to support my claim, as well as stating how someone could disagree with my claim. I had students begin making claims, using valid support, and challenging their claim in guided reading.

My students have moved from just stating their opinion, or claim, to always having valid support for their opinions. The word “because” is ingrained in their five and six-year old vocabulary. It’s become easier for many to empathize with other people’s opinions because they have gotten into the routine of challenging their own thinking. However, this is probably the toughest part of the effective reasoning thinking routine and many of my students are still working to get better at the question aspect of the Claim-Support-Question routine.

My students are critical thinkers, problem solvers, and able to consistently think outside the box. Parents have told me how impressed they are that their children are able to think this deeply about a topic. My biggest take-away from this experience has been that my kindergarteners can do a lot more than what people expect!

Thinking Routines in Kindergarten

Liz Rosenberg, Kindergarten Teacher at Creative Minds International Public Charter School

As I was looking for professional development opportunities over the summer in 2019, I happened to come across an online post for the Deeper Learning Cohort through Two Rivers. I had heard of thinking routines in the past but never really had the structure to implement them in my classroom. After spending only a few days together in July with this cohort of passionate, invested, skilled group of D.C. teachers, I felt inspired and empowered to push my students’ thinking before they even arrived in my classroom in August.

It is so easy as a teacher to get bogged down by the pressures of Common Core—we want our students to read, write, and solve math problems so they can be successful and score well on PARCC. While those content areas are of course very important, teaching for me has always been deeper than that. I want my students to grow up to be contributing members of society, who can think critically about the world and express their ideas and beliefs with conviction and confidence. To be successful in this world, they need to be able to communicate their thinking to others, making it visible to their audience, whether that audience is their classmates in a college course or their spouse later in their adult life. I want my students to understand the world from a global perspective, which includes truly comprehending that others may see the world differently than them and how that fact makes the world better, richer, and more diverse. So often we see adults who are not able to separate their thinking from their own lived experiences. I want more for my students and fight for that every day.

I have extremely high expectations of myself and those in my life—and that includes my students. I was surprised to learn as I progressed through this cohort of deeper learning that my students are capable of even more than I thought, that I can raise my expectations of them even higher! My students can make statements, support their claim with evidence, and think of a counterclaim. They can look at a set of choices, list criteria for a decision, and see if their choices meet the criteria. Many years ago, when I asked my students, “How do you know?” they would respond with answers like, “I thought it in my brain” or “my mom told me.” No longer is that acceptable in my classroom because I provided my students with the scaffolding so they can now make their thinking visible without as much support. They can problem solve by thinking about what they already know, what they want to know, and what ideas they should think about to drive their learning. And my five year-olds can communicate in meaningful ways through writing and pictures. They know their voices matter and what they have to say matters.

This is just the beginning. The values and lessons my students are learning are setting the foundation for them to be lifelong learners who question, think critically, back up their thinking with evidence, and be thoughtful and effective problem solvers. This is the world I want to live in and, together with my students, we are creating it.

Photo at top courtesy of Two Rivers Public Charter School.

Jeff Heyck-Williams with Chelsea Rivas and Liz Rosenberg

Two rivers deeper learning cohort.

Jeff Heyck-WIlliams is director of curriculum and instruction at Two Rivers Public Charter School.

Chelsea Rivas is a kindergarten teacher at Two Rivers Public Charter School.

Liz Rosenberg is a kindergarten teacher at Creative Minds International Public Charter School.

Read More About New Designs for School

NGLC Invites Applications from New England High School Teams for Our Fall 2024 Learning Excursion

March 21, 2024

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

How to Nurture Diverse and Inclusive Classrooms through Play

Rebecca Horrace, Playful Insights Consulting, and Laura Dattile, PlanToys USA

March 5, 2024

Accessibility Skip to :

- Accessibility Policy

- Main Content

- Ontario Teachers' Federation

- Past Webinars

Framing Learning: Problem Solving and Innovation in Kindergarten

- Joel Seaman

The Ontario Kindergarten Program is viewed through the lens of Four Frames of Learning. In this session, participants will dig deep into one of these frames: Problem Solving & Innovation. What does the frame look like in our classrooms? How can we facilitate purposeful, inquiry-based learning to strengthen problem solving skills? How can we document, observe, and assess innovation as it appears naturally in children’s play? Through both an exploration of the front matter of the program and practical examples from the classroom, this session will provide participants with an opportunity to think carefully about the frame of Problem Solving and Innovation in Kindergarten.

Presenter: Joel Seaman

Audience: Kindergarten

- The Kindergarten Program (Ministry of Education)

- Getting Started with Student Inquiry (Ministry of Education)

- Natural Curiousity (2 nd Edition)

- Engaging Children’s Minds: The Project Approach (Lilian Katz)

- Loose Parts: Inspiring Play in Young Children (Lisa Daly)

- STEM Play: Integrating Inquiry into Learning Centres (Deirdre Englehart)

- @JoelSeaman

- @IPSKindergarten (#Room109)

- Joel’s Blog:

- Rubics Cube Video

- Queen's University Library

- Research Guides

Kindergarten Resources

- Problem Solving & Innovation

- Children's Books

- Teacher Resources

- Picture Books

- Recommended Reading

Problem Solving and Innovating

This frame explores how can learn naturally in an open-ended environment. Children can learn through inquiry which is huge is kindergarten classrooms. Outdoor education is important because children can learn about nature which can lead to engagement in creative thinking, questioning, problem solving, observing, and perhaps interacting with classmates. Something children might be interested is plants. The teacher may enhance their curiosity by providing them with books, videos, art activities involving plants. Students may benefit from sensory play and hands-on exploring.

- << Previous: Teacher Resources

- Next: Picture Books >>

- Last Updated: Mar 3, 2024 2:52 PM

Kindergarten Lessons

Involve me and I learn...

Math Teaching/Learning

KINDERGARTEN PROBLEM SOLVING

Learning how to approach and solve problems early in life, not only helps children enjoy and look forward to sorting them out, it also helps them make and keep friends.

Preschool and kindergarten problem solving activities give children an opportunity to use skills they have learned previously and give you an opening to teach new problem solving strategies.

Introduce the vocabulary of solving problems with stories, puppets and everyday situations that occur. “We only have 10 apples but there are 20 students. This is a problem . Let’s think of some ways that we can solve this problem ?”

Use terms like, “a different way, let’s brainstorm, that’s a challenge, let’s think of some different solutions”.

How do I develop a problem solving approach?

Asking children questions such as , “How would you…?” or “Show me how you could…?”, help set the stage for teaching with a problem solving approach. Keep problem solving topics about subjects that interest the students. Kids are constantly trying to problem solve as they play.

Students are learning to:

- Identify problems or challenges

- Fact find (what do I know, what have I tried)

- Think of ways to solve the problem (brainstorm, creative thinking, generate ideas)

- Test their ideas

What preschool and kindergarten problem solving strategies can I teach?

Young children need real objects, pictures, diagrams, and models to solve problems. Start with real objects and move slowly to diagrams and pictures. Any of the following problem solving strategies will help them work through the four steps above:

- using objects

- acting the problem out

- looking for patterns

- guessing and checking

- drawing pictures

- making a graph

- teach with projects

Play creates classroom opportunities for problem solving

Perhaps a child is getting frustrated as he/she plays with blocks. To help him/her focus on the problem ask questions such as:

- What are you trying to do with your blocks?

- What isn’t working?

- What have you tried?

- Can you think of another way to stack the blocks?

- What else can you try?

Encourage creative thinking

Reinforce creative thinking, not results. The ability to solve problems and think creativity is important.

Talk about the different ways the child tried to solve the problem rather than the outcome. “Joe tried three different ways to stack the blocks. That was a great effort, Joe.”

Social classroom problem solving opportunities are abundant

- Identify the problem – Talk about the problem. For instance, some children may be worried because other kids are hiding the center markers for the play center and giving them to their friends. Other kids are not getting turns.

- Fact find – There are only 4 center markers for the play center because it is small and more than 4 kids would be too crowded. Some kids are hiding them so they can play with the same children each time.

- Brainstorm ideas – How can everyone have turns? What ideas do you have? What could we try?

- Test the idea – Let’s try that idea and meet again tomorrow and see how its working.

Investigating and Problem Solving

Using short periods of time examining and investigating objects, such as feathers or rocks, captures children’s attention and challenges them to inquire, to develop mind sets of being problem solvers and to think independently. Find a sample lesson here…

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Karen MacDonald

Mohawk College

This chapter aims to deepen an educator’s understanding of the value of technology in kindergarten classrooms and offers practical ways in which technology can be integrated into kindergarten programs. Although reference is made to Ontario’s Kindergarten Program, information will be beneficial to readers outside of Ontario who have similar education priorities. The integration of technology is discussed with specific support from the Ontario Ministry of Education’s (OME) (2016) Kindergarten Program publication. This establishes the basis for the exploration of how technology can support enhancements in pedagogy, curriculum and assessment. Pedagogical approaches that are explored include: educators as co-learner, learning through exploration, play and inquiry, pedagogical documentation and collaborative inquiry (OME, 2016). Contributing factors to a kindergarten educator’s reluctance to infuse technology into their classrooms are also reviewed. Specific examples of applications are shared to assist educators in exploring ways in which they can enhance their pedagogy, curriculum and assessment through the use of technology. The importance of p roviding opportunities for children to engage in technology-enhanced learning experiences to help develop skills that will prepare them for the future is reinforced. Further research is required in order to assist us, as educators and administrators, to reflect upon and re-evaluate the quality of support we are offering to our kindergarten teachers, our beliefs about the pedagogy of play and what we value as substantiation of a child’s learning.

Keywords: digital play, early childhood education, inquiry-based learning, kindergarten curriculum, kindergarten pedagogy, play-based learning, technology

Introduction

Children are our youngest digital natives, born into a world infused with technology. It is a familiar and natural occurrence in their everyday lives. The pedagogy that drives kindergarten programs in Ontario supports the integration of technology into classrooms as an authentic extension of young students’ learning (OME, 2016). Despite numerous studies supporting the prevalence of technology in a child’s life, as well as it being the chosen means for many children to express themselves and share their thinking, many kindergarten educators are hesitant to embrace the addition of technology into their teaching practice (Palaiologou, 2016). Early Childhood Educators (ECEs) and Kindergarten teachers have a responsibility to gain a deeper understanding of the importance of incorporating technology into the pedagogy and curriculum that supports our earliest learners.

Background Information

Within Ontario’s kindergarten classrooms, pedagogy and curriculum are driven by the OME (2016) document The Kindergarten Program. This document outlines the changes in pedagogical approaches from traditional educator-lead pedagogy to one that is learner centred (OME, 2016). It stresses the importance of developing a curriculum that supports each child as competent, curious and capable of complex thinking and the need to provide learning opportunities that prepare students for an ever-changing world (OME, 2016). It is imperative for educators to be mindful that our role is to prepare students for the future. There has been a pedagogical shift from teacher-lead classrooms with theme-based curriculum to one that supports play and inquiry-based learning driven by the interests and abilities of students. Edwards (2013) argues that we need to bridge the gap between how children naturally engage with technology outside of the classroom and our understanding of the pedagogy of play as the foundation of our Kindergarten programs.

Students in our kindergarten classrooms will need to work in a world where technology will advance at a rate we cannot yet comprehend (Prensky, 2010). It is argued that educators need to take a closer look at opportunities to make digital play an integral piece of early years pedagogy (Nolan & McBride, 2014) and that educators’ current beliefs about play-based learning impedes the practice of embracing technology as a fundamental component of an early learning environment (Palaiologou, 2016). Educators argue that the hesitancy is due to accessibility, where every child may not have equal means to access technology. Other factors influencing the lack of willingness to embrace technology in the early years are the beliefs that it causes social isolation and promotes a sedentary lifestyle in children (Palaiologou, 2016). Some educators believe that a child’s authentic hands-on experiences within their natural environment are impeded when technology is introduced and that they become more isolated learners (Palaiologou, 2016). Teachers’ efficacy, values and beliefs about technology and the lack of professional development and support (Edwards, 2013; Palaiologou, 2016) are additional barriers. The pedagogical freedom for educators to make decisions about when and where to use technology to support their students’ learning have also been found to impede the willingness for educators to embrace technology as an integral component of their pedagogy (Edwards, 2013).

Influencing Pedagogy

Pedagogical approaches that guide the kindergarten curriculum include: educators as co-learner, learning through exploration, play and inquiry, pedagogical documentation and collaborative inquiry (OME, 2016). The first two approaches will be further explored with the focus on how technology can support and enhance these initiatives within the kindergarten classroom. The latter two will be explored under the heading of Assessment.

Educators as Co-learners

In order to gain a deeper understanding of the interests, skills and abilities of their learners, educators are moving from the role as the keeper of all knowledge to the role of head learner in kindergarten classrooms (OME, 2016). Educators must focus on questioning, guiding, coaching and providing context (Prensky, 2010). Students today want an educational leader who will respect their ability to learn beyond limitations and to provide opportunities to engage with technological tools to build knowledge and relationships (Prensky, 2010). This is most successfully accomplished by kindergarten educators through the facilitation, intentional planning of and engagement in children’s play experiences. Digital applications can be used to share consistent feedback between student and educator, offer tools to collect documentation of students’ learning, and to respectfully share resources to increase students’ self-efficacy and motivation.

Learning Through Exploration, Play and Inquiry

Inquiry based learning occurs when educators embrace the natural curiosity of their learners. In kindergarten classrooms, children should be encouraged to ask questions and wonder about topics that they are interested in to uncover curriculum expectations. Through consistent play, inquiry and free exploration, children gain 21 st century skills such as critical, creative and complex thinking, innovative design, problem solving and collaboration (OME, 2016). Prensky (2010) also supports this necessity stating that our pedagogy should reflect a strong support of such skills as finding information, manipulating that information to make sense of it, creating new ideas and solving problems in unique ways. Similarly, Fullan (2013) states that “the interest in and ability to create new knowledge and solve new problems is the single most important skill that all students should master today” (Fullan, p. 24).

The incorporation of technology is most successful when it is paired with a pedagogy that supports the intentions of its use (Prensky, 2010). Many times, the pedagogy of play is seen as a separate entity from the use of technology, which instead, is viewed as a tool to support the skills of learners (Edwards, 2013). Digital Play should be a naturally occurring, integral part of a classroom setting, not a separate learning area. When given the opportunity, children can merge digital technology into their play in ways that “expand the range of identities they explore and the tools and practices with which to explore them” (McGlynn-Stewart, 2019, p. 52). Through inquiry, based on naturally occurring interests of children in the classroom, students are able to solve problems to gain a greater understanding of their world. When educators stand aside and let the learning happen, children achieve greater skills because they have been given the opportunity to seek answers on their own or through collaboration with their peers, rather than being taught the solution first (Brown, P.C. Roediger, H.L. & McDaniel, M. A., 2014). Palaiologou (2016) argues that we need to provide digital means for children to extend possibilities within their play in order to accomplish this task.

Application.

Apps such as Khan Academy Kids (Khan Academy, n.d.), National Geographic Kids (National Geographic, n.d.) and Explain Everything (Explain Everything, n.d.) provide interactive online environments supporting students’ inquiry .

Influencing Curriculum

The Kindergarten Program (OME, 2016) uses the following four frames to help organize how we think about children’s thinking and the assessment of their learning: Belonging and Contributing, Self-Regulation and Well-Being, Demonstrating Literacy and Math Skills and Problem Solving and Innovating (OME, 2016). Technology positively influences all frames, but the latter frame will be focused on in this section.

Problem-solving and Innovating

In this frame, children demonstrate their unique ways of solving problems or relating to ideas by exploring things they are naturally curious about (OME, 2016). Students may ask questions, test theories and engage in analytical thinking while educators design a learning area that includes various tools that allow children a choice in what methods would best support the development of these skills. Educators offer opportunities for collaborative learning and should create spaces where children can express their thinking and learning. This is supported through the technology-related expectations that are stated with the Kindergarten Program (OME, 2016) including: using technology to solve problems independently or with others, plan, question, construct new knowledge and analyze and communicate thinking (OME, 2016).

The integration of technology may support a child’s understanding of concepts in literacy and math through practical application, problem-solving and collaboration (Palaiologou, 2016). Researchers have also found that engaging in digital game-based programs promotes collaboration, problem-solving, communication and experimentation among kindergarten students and suggest that allowing students to behave more autonomously in game play, leads to higher engagement and motivation (Nolan & McBride, 2014). Practical examples of applications that support the enhancement of problem-solving and innovation are listed below.

An open-ended app such as 30 Hands (30 Hands Learning n.d.) enables children to document their thinking by way of drawing pictures and recording voice to write their own stories. This app provides students a means to share their thoughts beyond the limitations they would have displayed without the use of digital technology (McGlynn-Stewart, Brathwaite, Hobman, Maguire & Mogyorodi, 2018). The 30 Hands app also allows children to save and revisit their work allowing reflection on their learning and the deeper complexity of their thinking (McGlynn-Stewart et al., 2018). Similarly, apps such as Thinglink (Thinglink, n.d.) and Shadow Puppet Edu (Seesaw Learning Inc. (n.d.) allow students to capture, organize and communicate their thinking in unique and interesting ways. An app such as Gamestar Mechanic (Gamestar Mechanic, n.d.) allows early learners to begin developing skills in coding and game creation and an app such as Blokify (Blokify, n.d.) can help students as young as 4 or 5 years to design, create, problem-solve and collaborate within a Makerspace environment.

Influencing Assessment

Learners today think, communicate and use different means to share what they know in ways that are different from students in past decades. Donovan, Bransford and Pellegrino (2002) state that, with our newest learners, we must move beyond traditional testing to incorporate understanding through frequent formative assessments that make learning visible (Donovan et al., 2002). It is imperative that we enhance our traditional methods of assessment with technology-based assessment in order to provide more enriched feedback to our learners.

Pedagogical Documentation

Pedagogical documentation is defined as the gathering of and analysis of evidence of a student’s thinking (OME, 2016). Educators aim to make a student’s learning visible to both the child and family, and use knowledge gained from observations to drive further programming. Within kindergarten classrooms, pedagogical documentation provides the means to which assessment for, as and of learning is made (OME, 2016). In a play-based environment, educators should gather frequent and meaningful observations of children that incorporate the child’s voice so that reflections can be made about how a child interprets, understands and interacts with their world (OME, 2016). Pedagogical documentation, which technology has the capability to enhance, provides a means of formative assessment of a child’s learning and, in turn, should drive future curriculum planning (Rintakorpi, 2016).

Application.

Apps that allow students to organize and record their process of learning (as described above) captures visible documentation that can be saved, shared, revisited and revised which allows children to develop an in-depth understanding of curriculum. These applications provide a diary of the progression of a child’s journey in reaching outcomes; a story of each child’s learning.

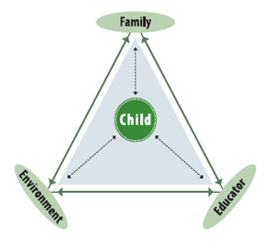

Reflective Practice and Collaborative Inquiry

In early learning environments, the relationship between parent, child and educator helps build an important foundation for a child’s learning. Educators both independently reflect on and collaborate with peers, families and children about the pedagogical documentation they have collected OME, 2016) in order to learn from the experiences of each student. By including parents in these conversations, an educator gains insight into a child’s previous knowledge and experiences at home. Research has shown that using documentation empowers educators and nurtures their relationship with children and parents by providing an important tool for communicating and understanding a child’s perspective (Rintakorpi, 2016).

Apps such as Brightwheel (Brightwheel, n.d.) and Storypark (Storypark, n.d.) provide a platform to capture a child’s learning through pedagogical documentation that can be shared and securely accessed by children and their families.

Conclusions and Future Recommendations

Although it is supported through expectations laid out by our Ministry of Education (2016) in The Kindergarten Program publication, many kindergarten educators remain reluctant to embrace technology as an integral part of their pedagogy and curriculum. One of the most prevalent factors contributing to this is an educator’s belief about the pedagogy of play and what they value as evidence of a child’s learning. Palaiologou (2016) believes there is a need to challenge the current ideology of what we believe about a child’s play and that only then can educators embrace technology within their kindergarten classrooms. The addition of technology-based pedagogy into pre-teaching programs as well as increased professional development for current educators could close the gap between what educators believe about how a child learns and understanding how technology does not hinder but enriches the quality of this learning. Further research is needed to examine the relationship between traditional and digital play as well as the influence that digital technology has on a child’s learning experiences within play and inquiry-based environments.

Blokify. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from http://blokify.com

Brightwheel. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://brightwheel.com

Brown, P.C., Roediger, H.L. & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Learning is misunderstood in Make it stick (pp. 1-22). Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Donovan, M.S, Bransford, J. D., & Pellegrino, J.W. (2002). Key findings in How people learn: Bridging research & practice (pp. 10-24). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Edwards, S. (2013). Digital play in the early years: a contextual response to the problem of integrating technologies and play-based pedagogies in the early childhood curriculum. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21 (2), 199-212. doi:10.1080/1350293x.2013.789190

Explain Everything. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://explaineverything.com

Fullan, M. (2013). Pedagogy and change: Essence as easy. In Stratosphere (pp.17-32). Toronto, Ontario: Pearson

Gamestar Mechanic. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://gamestarmechanic.com/

30 Hands Learning. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from http://30hands.com/

Khan Academy. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/kids

McGlynn-Stewart, M., Brathwaite, L., Hobman, L., Maguire, N., & Mogyorodi, E. (2019). Open-Ended Apps in Kindergarten: Identity Exploration Through Digital Role-Play. Language and Literacy, 20 (4), 40-54. doi:10.20360/langandlit29439

Muis, K. R., Ranellucci, J., Trevors, G., & Duffy, M. C. (2015). The effects of technology-mediated immediate feedback on kindergarten students’ attitudes, emotions, engagement and learning outcomes during literacy skills development. Learning and Instruction , 38, 1-13. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.02.001

National Geographic. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2016). The kindergarten program . [Web page]. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/kinderprogram.html

Palaiologou, I. (2016). Teachers’ dispositions towards the role of digital devices in play-based pedagogy in early childhood education. Early Years , 36 (3), 305-321. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1174816

Prensky, M. (2010). Partnering. Teaching digital natives. Partnering for real learning (pp. 9-29). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Rintakorpi, K. (2016). Documenting with early childhood education teachers: pedagogical documentation as a tool for developing early childhood pedagogy and practises. Early Years , 36 (4), 399-412. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1145628

Seesaw Learning Inc. (2014, June 26). ‘Shadow Puppet Edu. [Software application]. Retrieved from https://apps.apple.com/us/app/shadow-puppet-edu/id888504640

Storypark. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.storypark.com/ca/

ThingLink. (n.d.). [Web page]. Retrieved from https://www.thinglink.com/

Technology and the Curriculum: Summer 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Karen MacDonald is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Kindergarten

- Problem Solving and Innovating

Problem Solving and Innovating Learning Activity

- Minds On: Introduces the learning concepts to be explored in the Learning Activity.

- Action: Offers a focused activity to explore the content and discover key concepts.

- Consolidation: Provides students with an opportunity to deepen understanding and reflect on learning.

- choosing a selection results in a full page refresh

- press the space key then arrow keys to make a selection

Ontario.ca needs JavaScript to function properly and provide you with a fast, stable experience.

To have a better experience, you need to:

- Go to your browser's settings

- Enable JavaScript

1.1 Introduction

Vision, purpose, and goals.

The Kindergarten program is a child-centred, developmentally appropriate, integrated program of learning for four- and five-year-old children. The purpose of the program is to establish a strong foundation for learning in the early years, and to do so in a safe and caring, play-based environment that promotes the physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development of all children.

The primary goals of the Kindergarten program are:

- to establish a strong foundation for learning in the early years;

- to help children make a smooth transition from home, child care, or preschool settings to school settings;

- to allow children to reap the many proven benefits of learning through relationships, and through play and inquiry;

- to set children on a path of lifelong learning and nurture competencies that they will need to thrive in the world of today and tomorrow.

The Kindergarten program reflects the belief that four- and five-year-olds are capable and competent learners, full of potential and ready to take ownership of their learning. It approaches children as unique individuals who live and learn within families and communities. Based on these beliefs, and with knowledge gained from research and proven in practice, the Kindergarten program:

- supports the creation of a learning environment that allows all children to feel comfortable in applying their unique ways of thinking and learning;

- is built around expectations that are challenging but attainable;

- is flexible enough to respond to individual differences;

- self-regulation;

- health, well-being, and a sense of security;

- emotional and social competence;

- curiosity, creativity, and confidence in learning;

- respect for diversity;

- supports engagement and ongoing dialogue with families about their children's learning and development.

The vision and goals of the Kindergarten program align with and support the goals for education set out in Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario (2014) – achieving excellence, ensuring equity, promoting well-being, and enhancing public confidence.

The importance of early learning

[Early childhood is] a period of momentous significance … By the time this period is over, children will have formed conceptions of themselves as social beings, as thinkers, and as language users, and they will have reached certain important decisions about their own abilities and their own worth. (Donaldson, Grieve, & Pratt, 1983, p. 1)

Evidence from diverse fields of study tells us that children grow in programs where adults are caring and responsive. Children succeed in programs that focus on active learning through exploration, play, and inquiry. Children thrive in programs where they and their families are valued as active participants and contributors. From How Does Learning Happen? (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014c, p. 4)

Early childhood is a critical period in children's learning and development. Early experiences, particularly to the age of five, are known to "affect the quality of [brain] architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for all of the learning, health and behavior that follow" (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2007).

Children arrive in Kindergarten as unique individuals shaped by their particular cultural and social background, socio-economic status, personal capabilities, and day-to-day experiences, and at different stages of development. All of these factors influence their ability to reach their full potential. Experiences during the early years strongly influence their future physical, mental, and emotional health, and their ability to learn.

For these reasons, children's early experiences at school are of paramount importance. Quality early-learning experiences have the potential to improve children's overall health and well-being for a lifetime. By creating, fostering, and sustaining learning environments that are caring, safe, inclusive, and accepting, educators can promote the resilience and overall well-being of children. The cognitive abilities, skills, and habits of mind that characterize lifelong learners have their foundation in the critical early years.

In addition, it is essential for programs to provide a variety of learning opportunities and experiences based on assessment information that reveals what the children know, what they think and wonder about, where they are in their learning, and where they need to go next. Assessment that informs a pedagogical approach suited to each child's particular strengths, interests, and needs will promote the child's learning and overall development.

The importance of early experiences for a child's growth and development is recognized in the design of The Kindergarten Program, which starts with the understanding that all children's learning and development occur in the context of relationships – with other children, parents and other family members, educators, and the broader environment.

Figure 1. Learning and development happen within the context of relationships among children, families, educators, and their environments.

A shared understanding of children, families, and educators

The understanding that children, families, and educators share about themselves and each other, and about the roles they play in children's learning, has a profound impact on what happens in the Kindergarten classroom. footnote 1 [1] The view of children, families, and educators provided in the following descriptions is at the heart of Ontario's approach to pedagogy for the early years. When educators in early years and Kindergarten programs reflect on and come to share these perspectives, and when they work towards greater consistency in pedagogical approach, they help strengthen and transform programs for children across the province.

All children are competent, capable of complex thinking, curious, and rich in potential and experience. They grow up in families with diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. Every child should feel that he or she belongs, is a valuable contributor to his or her surroundings, and deserves the opportunity to succeed. When we recognize children as competent, capable, and curious, we are more likely to deliver programs that value and build on their strengths and abilities.

Families are composed of individuals who are competent and capable, curious, and rich in experience. Families love their children and want the best for them. Families are experts on their children. They are the first and most powerful influence on children's learning, development, health, and well-being. Families bring diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. Families should feel that they belong, are valuable contributors to their children's learning, and deserve to be engaged in a meaningful way.

Educators are competent and capable, curious, and rich in experience. They are knowledgeable, caring, reflective, and resourceful professionals. They bring diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. They collaborate with others to create engaging environments and experiences to foster children's learning and development. Educators are lifelong learners. They take responsibility for their own learning and make decisions about ways to integrate knowledge from theory, research, their own experience, and their understanding of the individual children and families they work with. Every educator should feel he or she belongs, is a valuable contributor, and deserves the opportunity to engage in meaningful work.

The Kindergarten Program flows from these perspectives, outlining a pedagogy that expands on what we know about child development and invites educators to consider a more complex view of children and the contexts in which they learn and make sense of the world around them. This approach may require, for some, a shift in mindset and habits. It may prompt a rethinking of theories and practices – a change in what we pay attention to; in the conversations that we have with children, families, and colleagues; and in how we plan and prepare.

The manner in which we interact with children is influenced by the beliefs we hold. To move into the role of co-learner, educators must acknowledge the reciprocal relationship they are entering: the child has something to teach us, and we are engaged in a learning journey together, taking turns to lead and question and grow as we encounter new and interesting ideas and experiences. The view of the child presented above recognizes the experiences, curiosities, capabilities, competencies, and interests of all learners.

Pedagogy and programs based on a view of children as competent and capable

Pedagogy is defined as the understanding of how learning happens and the philosophy and practice that support that understanding of learning. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 90)

When educators view children as competent and capable, the learning program becomes a place of wonder, excitement, and joy for both the child and the educator. (Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 9)

Educators' beliefs about children are foundational to sound pedagogy and a high-quality learning program. Over the years, the image of children has evolved, and the cultural view – the one that is "shaped by the values and beliefs about what childhood should be at the time and place in which we live" (Fraser, 2012, p. 20) – has shifted. When educators believed that children were "empty vessels to be filled", programs could be too didactic, centred on the educator and reliant on rote learning, or they involved minimal interaction between children and educators; in either case, they risked restricting rather than promoting learning.

When programs are founded on the image of the child presented above and when educators apply knowledge and learning gained through external and classroom research, early learning programs in Ontario, including Kindergarten programs, can establish a strong foundation for learning and create a learning environment that allows all children to grow and to learn in their unique, individual ways.

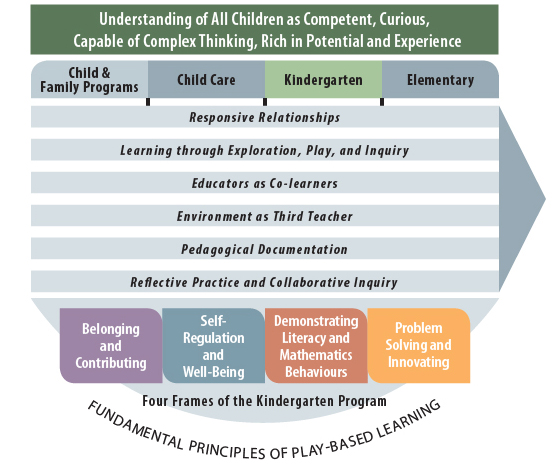

Pedagogical approaches

The pedagogical approaches that work best for young children are similar to strategies that work for learners of all ages, from infancy to adulthood. Evidence from research and practice shows that these approaches are the most effective ways to nurture and support learning and development among both children and adult learners.

- Responsive relationships – Evidence from research and practice shows that positive interactions between teacher and student are the most important factor in improving learning (Hattie, 2008). An awareness of being valued and respected – of being seen as competent and capable – by the educator builds children's sense of self and belonging and contributes to their well-being, enabling them to be more engaged in learning and to feel more comfortable in expressing their thoughts and ideas.

- Learning through exploration, play, and inquiry – As children learn through play and inquiry, they develop – and have the opportunity to practise every day – many of the skills and competencies that they will need in order to thrive in the future, including the ability to engage in innovative and complex problem-solving and critical and creative thinking; to work collaboratively with others; and to take what is learned and apply it in new situations in a constantly changing world. (See the "Fundamental Principles of Play-Based Learning" in the following section, and Chapter 1.2, "Play-Based Learning in a Culture of Inquiry" . )

- Educators as co-learners – Educators today are moving from the role of "lead knower" to that of "lead learner" (Katz & Dack, 2012, p. 46). In this role, educators are able to learn more about the children as they learn with them and from them.

- Environment as third teacher – The learning environment comprises not only the physical space and materials but also the social environment, the way in which time, space, and materials are used, and the ways in which elements such as sound and lighting influence the senses. (See Chapter 1.3, "The Learning Environment" .)

- Pedagogical documentation – The process of gathering and analysing evidence of learning to "make thinking and learning visible" provides the foundation for assessment for , as , and of learning. (See Chapter 1.4, "Assessment and Learning in Kindergarten: Making Children's Thinking and Learning Visible" .)

- Reflective practice and collaborative inquiry – Educators develop and expand their practice by reflecting independently and with other educators, children, and children's families about the children's growth and learning.

These pedagogical approaches, outlined in How Does Learning Happen?, are central to the discussion in Part 1 of this document. Throughout the document, they are understood to be foundational to teaching that supports learning in Kindergarten and beyond.

Fundamental principles of play-based learning

Global conversations and perspectives on learning from various fields – neuroscience, developmental and social psychology, economics, medical research, education, and early childhood studies – confirm that, among the pedagogical approaches described above, play-based learning emerges as a focal point, with proven benefits for learning among children of all ages, and indeed among adolescent and adult learners. The following fundamental principles have been developed to capture the recurring themes in the research on beneficial pedagogical approaches, from the perspective of play-based learning.

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes "the right of the child … to engage in play … appropriate to the age of the child" and "to participate freely in cultural life and the arts". footnote 2 [2]

- Play is essential to the development of children's cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being. The Association for Childhood Education International (ACEI) recognizes play as necessary for all children and critical to children's optimal growth, learning, and development from infancy to adolescence. footnote 3 [3]

- Educators recognize the benefits of play for learning and engage in children's play with respect for the children's ideas and thoughtful attention to their choices.

- In play-based learning, educators honour every child's views, ideas, and theories; imagination and creativity; and interests and experiences, including the experience of assuming new identities in the course of learning ( e.g. , "I am a writer!"; "I am a dancer!").

- The child is seen as an active collaborator and contributor in the process of learning. Together, educators and learners plan, negotiate, reflect on, and construct the learning experience.

- Educators honour the diversity of social, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds represented among the children in the classroom, and take each child's background and experiences into account when interpreting and responding to the child's ideas and choices in play.

- Play and inquiry engage, challenge, and energize children, promoting an active, alert, and focused state of mind that is conducive to learning.

- Children's choices in play are the best starting points for the co-construction of learning with the child.

- questioning;

- provoking; footnote 4 [4]

- providing descriptive feedback;

- engaging in reciprocal communication and sustained conversations;

- providing explicit instruction at the moments and in the contexts when it is most likely to move a child or group of children forward in their learning.

- A learning environment that is safe and welcoming supports children's well-being and ability to learn by promoting the development of individual identity and by ensuring equity footnote 5 [5] and a sense of belonging for all.

- Both in the classroom and out of doors, the learning environment allows for the flexible and creative use of time, space, and materials in order to respond to children's interests and needs, provide for choice and challenge, and support differentiated and personalized instruction and assessment.

- The learning environment is constructed collaboratively and through negotiation by children and educators, with contributions from family and community members. It evolves over time in response to children's developing strengths, interests, and abilities.

- A learning environment that inspires joy, awe, and wonder promotes learning.

- In play-based learning, educators, children, and family members collaborate in ongoing assessment for and as learning to support children's learning and their cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development.

- Assessment in play-based learning involves "making thinking and learning visible" by documenting and reflecting on what the child says, does, and represents in play and inquiry.

The four frames of the Kindergarten program

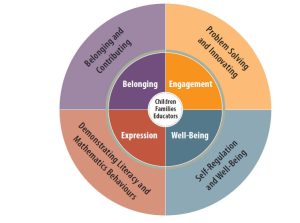

In the Kindergarten program, four "frames", or broad areas of learning, are used to structure thinking about learning and assessment. footnote 6 [6] The frames – Belonging and Contributing, Self-Regulation and Well-Being, Demonstrating Literacy and Mathematics Behaviours, and Problem Solving and Innovating – are designed to support an approach that aligns with the way children's learning naturally occurs and that focuses on aspects of learning that are critical to young children's development. The frames reflect the integrated way in which learning occurs during children's play and inquiry in Kindergarten.

The four frames align with the four foundational conditions needed for children to grow and flourish – Belonging , Well-Being , Expression , and Engagement . These foundations, or ways of being , are central to the pedagogy outlined in the early learning resource How Does Learning Happen? They are conditions that children naturally seek for themselves, and they apply regardless of age, ability, culture, language, geography, or setting.

Figure 2. The four frames of Kindergarten (outer circle) grow out of the four foundations for learning and development set out in the early learning curriculum framework (inner circle). The foundations are essential to children's learning in Kindergarten and beyond . The frames encompass areas of learning for which four- and five-year-olds are developmentally ready.

The four Kindergarten frames grow out of the four foundations for learning and development. The Kindergarten frames are defined more specifically to reflect the developmental and learning needs of children in Kindergarten and beyond.

The overall expectations ( OEs ) of the Kindergarten program are connected with the four frames (see The Overall Expectations, by Frame ). An expectation is associated with the frame that encompasses the aspects of learning and development to which that expectation most closely relates. An expectation that addresses more than one aspect of learning may be connected with more than one frame footnote 7 [7] . (Two of the overall expectations – OE 1 and OE 22 – are associated with all four frames, because they relate to all aspects of learning. For example, OE 1 describes the ability to communicate ideas and emotions in various verbal and non-verbal ways, which is fundamental to all learning.) The grouping of expectations within particular frames also indicates a relationship between and among those expectations.

The four frames may be described as follows:

Belonging and contributing

This frame encompasses children's learning and development with respect to:

- their sense of connectedness to others;

- their relationships with others, and their contributions as part of a group, a community, and the natural world;

- their understanding of relationships and community, and of the ways in which people contribute to the world around them.

The learning encompassed by this frame also relates to children's early development of the attributes and attitudes that inform citizenship, through their sense of personal connectedness to various communities.

Self-regulation and well-being

- their own thinking and feelings, and their recognition of and respect for differences in the thinking and feelings of others;

- regulating their emotions, adapting to distractions, and assessing consequences of actions in a way that enables them to engage in learning;

- their physical and mental health and wellness.

In connection with this frame, it is important for educators to consider:

- the interrelatedness of children's self-awareness, sense of self, and ability to self-regulate;

- the role of the learning environment in helping children to be calm, focused, and alert so they are better able to learn.

What children learn in connection with this frame allows them to focus, to learn, to respect themselves and others, and to promote well-being in themselves and others.

Demonstrating literacy and mathematics behaviours

- communicating thoughts and feelings – through gestures, physical movements, words, symbols, and representations, as well as through the use of a variety of materials;

- literacy behaviours, evident in the various ways they use language, images, and materials to express and think critically about ideas and emotions, as they listen and speak, view and represent, and begin to read and write;

- mathematics behaviours, evident in the various ways they use concepts of number and pattern during play and inquiry; access, manage, create, and evaluate information; and experience an emergent understanding of mathematical relationships, concepts, skills, and processes;

- an active engagement in learning and a developing love of learning, which can instil the habit of learning for life.

What children learn in connection with this frame develops their capacity to think critically, to understand and respect many different perspectives, and to process various kinds of information.

Problem solving and innovating

- exploring the world through natural curiosity, in ways that engage the mind, the senses, and the body;

- making meaning of their world by asking questions, testing theories, solving problems, and engaging in creative and analytical thinking;

- the innovative ways of thinking about and doing things that arise naturally with an active curiosity, and applying those ideas in relationships with others, with materials, and with the environment.

The learning encompassed by this frame supports collaborative problem solving and bringing innovative ideas to relationships with others.

In connection with this frame, it is important for educators to consider the importance of problem solving in all contexts – not only in the context of mathematics – so that children will develop the habit of applying creative, analytical, and critical thinking skills in all aspects of their lives.

What children learn in connection with all four frames lays the foundation for developing traits and attitudes they will need to become active, contributing, responsible citizens and healthy, engaged individuals who take responsibility for their own and others' well-being.

Supporting a continuum of learning

The Ontario Early Years Policy Framework envisages early years curriculum development that helps children make smooth transitions from early childhood programs to Kindergarten, the primary grades, and beyond. All of the elements discussed above – a common view of children as competent and capable; coherence across pedagogical approaches; a shared understanding of the foundations for learning and development, leading into the four frames of the Kindergarten program; and the fundamental principles of play-based learning – contribute to creating more seamless programs for children, families, and all learners, along a continuum of learning and development.

The vision of the continuum is illustrated in How Does Learning Happen? (p. 14). That graphic is adapted here to depict the continuum from the perspective of Kindergarten.

Figure 3. Pedagogical approaches that support learning are shared across settings to create a continuum of learning for children from infancy to age six, and beyond.

The organization and features of this document

This document is organized in four parts:

- Part 1 outlines the philosophy and key elements of the Kindergarten program, focusing on the following: learning through relationships; play-based learning in a culture of inquiry; the role of the learning environment; and assessment for, as, and of learning through the use of pedagogical documentation, which makes children's thinking and learning visible to the child, the other children, and the family.

- Part 2 comprises four chapters, each focused on "thinking about" one of the four Kindergarten frames. Each chapter explores the research that supports the learning focus of the frame for children in Kindergarten, outlines effective pedagogical approaches relevant to the frame, and provides tools for reflection to help educators develop a deeper understanding of learning and teaching in the frame.

- Part 3 focuses on important considerations that educators in Kindergarten take into account as they build their programs, and on the connections and relationships that are necessary to ensure a successful Kindergarten program that benefits all children.

- Part 4 sets out the learning expectations for the Kindergarten program and provides tools for supporting educators' professional learning and reflection. The list of the overall expectations , indicating the frame or frames to which each expectation is connected, is presented in Chapter 4.2. Chapters 4.3 through 4.6 set out the overall expectations and conceptual understandings by frame , along with "expectation charts" for each frame. The expectation charts provide information and examples to illustrate how educators and children interact to make thinking and learning visible in connection with the specific expectations that are relevant to the particular frame.

- The appendix is a chart that lists all of the overall expectations, with their related specific expectations, and indicates the frame(s) with which each expectation is associated.

The document is designed to guide educators as they adopt the pedagogical approaches that will help the children in their classrooms learn and grow. It recognizes the transformational nature of these approaches, as well as the benefits of collaborative reflection and inquiry in making the transition from more traditional pedagogies and program planning approaches. To support and inspire educators as they reflect on and rethink traditional beliefs and practices and apply new ideas from research and proven practice, this document offers a variety of special features:

- Educator Team Reflections and Inside the Classroom: Reflections on Practice – Reflections and scenarios provided by educators from across Ontario, reflecting situations that arose in their own classrooms during the implementation of Kindergarten.

- Professional Learning Conversations – Interspersed throughout the expectation charts in Part 4 and focused on learning in relation to the overall and specific expectations, these conversations illustrate pedagogical insights gained through collaborative professional learning among educators across Ontario.

- Questions for Reflection – Questions designed to stimulate reflection and conversation about key elements and considerations related to the Kindergarten program.

- Misconceptions – Lists of the common misconceptions that abound about children's learning through play and inquiry and that are addressed throughout the chapters of this document.

- Links to Resources – Active links to electronic resources, including videos and web postings, that illustrate pedagogical approaches discussed in the text.

- Internal Links – Active links to related sections or items within The Kindergarten Program .

- footnote [1] Back to paragraph ^ This section is adapted from How Does Learning Happen? (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014c).

- footnote [2] Back to paragraph ^ United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Article 31,“Convention on the Rights of the Child” (Entry into force 2 September 1990).

- footnote [3] Back to paragraph ^ J.P. Isenberg and N. Quisenberry, “A Position Paper of the Association for Childhood Education International – Play: Essential for All Children”. Childhood Education (2002), 79(1), p. 33.

- footnote [4] Back to paragraph ^ In education, the term “provoking” refers to provoking interest, thought, ideas, or curiosity by various means – for example, by posing a question or challenge; introducing a material, object, or tool; creating a new situation or event; or revisiting documentation. “Provocations” spark interest, and may create wonder, confusion, or even tension. They inspire reflection, deeper thinking, conversations, and inquiries, to satisfy curiosity and resolve questions. In this way, they extend learning.

- footnote [5] Back to paragraph ^ Ensuring equity is one of the four goals outlined in the Ministry of Education’s Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario (2014a, p. 8), which states: “The fundamental principle driving this [vision] is that every student has the opportunity to succeed, regardless of ancestry, culture, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, language, physical and intellectual ability, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socio- economic status or other factors.”

- footnote [6] Back to paragraph ^ Children’s learning is also evaluated and communicated in terms of these four frames, as outlined in Growing Success − The Kindergarten Addendum (2016).

- footnote [7] Back to paragraph ^ Note that the inclusion of an expectation in a frame or frames does not mean that the learning outlined in the expectation relates exclusively to that frame or frames.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Problem Solving and Innovating - "Learning to think creatively, analytically and critically is important in all aspects of life. Children are naturally curious. ... Kindergarten Expectations: (15) Demonstrate an understanding of numbers, using concrete materials to explore and investigate counting, quantity, and number relationships. ...

As children progress through the Kindergarten program, they: 1. communicate with others in a variety of ways, for a variety of purposes, and in a variety of contexts. 4. demonstrate an ability to use problem-solving skills in a variety of contexts, including social contexts. 6. demonstrate an awareness of their own health and well-being.

For a wide range of practical examples of how children and educators interact to make thinking and learning about problem solving and innovating visible, in connection with related overall and specific expectations in the Kindergarten program, see the expectation charts for this frame in Chapter 4.6.

The Kindergarten - Four Frame program is a child-centred, developmentally appropriate, integrated program of learning for four- and five-year-old children. ... The learning encompassed by this frame supports collaborative problem solving and bringing innovative ideas to relationships with others. Curriculum Expectations.

PROBLEM SOLVING AND INNOVATING As children progress through the Kindergarten program, they: communicate with others in a variety of ways, for a variety of purposes, and in a variety of contexts demonstrate an ability to use problem-solving skills in a variety of contexts, including social contexts

2.4 THINKING ABOUT PROBLEM SOLVING AND INNOVATING 87. Problem Solving and Innovating: What Are We Learning . from Research? 87 Supporting Children's Development in Problem Solving . ... 4.2 THE OVERALL EXPECTATIONS IN THE KINDERGARTEN PROGRAM, BY FRAME 121. The Expectations and the Frames Expectation Charts121. 4.3 BELONGING AND CONTRIBUTING 125.

2.4 Thinking about problem solving and innovating Part 3: The program in context. 3.1 Considerations for program planning; 3.2 Building partnerships: Learning and working together Part 4: The learning expectations. 4.1 Using the elements of the expectation charts; 4.2 The overall expectations in the Kindergarten program, by frame

Problem Solving and Innovating; In the Kindergarten program, four "frames" are used to structure thinking about learning and assessment. The frames are designed to support a way of thinking that aligns with the way children's learning naturally occurs and that focuses on aspects of learning that are critical to young children's development.

In Ontario, the Kindergarten program is made up of four "frames", or broad areas of learning. This frame captures children's learning and development with respect to: exploring the world through natural curiosity, in ways that engage the mind, the senses and the body; making meaning of their world by asking questions, testing theories ...

Kindergarteners were thinking critically! Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., is wrapping up our second Deeper Learning Cohort. Twenty-four educators from schools across the city participated to learn how to deepen their students' thinking through the use of thinking routines with aligned rubrics and performance assessments.

Through both an exploration of the front matter of the program and practical examples from the classroom, this session will provide participants with an opportunity to think carefully about the frame of Problem Solving and Innovation in Kindergarten. Presenter: Joel Seaman. Audience: Kindergarten.

Coding has increasingly become very popular in schools to support problem-solving and innovation. As students progress through kindergarten, they gain process skills of an inquiry state, such as questioning and predicting (OME, 2016). In this frame, children can develop a sense of appreciation for human creativity and innovation (OME, 2016).

The Kindergarten program is based on four broad learning areas: 1. Belonging and Contributing 2. Self-Regulation and Well-Being 3. Demonstrating Literacy and Mathematics Behaviours 4. Problem Solving and Innovating. These areas focus on aspects of learning that are critical to your child's development.

4. demonstrate an ability to use problem-solving skills in a variety of contexts, including social contexts x x x 4.1 use a variety of simple strategies to solve problems, including problems arising in social situations (e.g., trial and error, checking and guessing, cross-checking - looking ahead and back to find material to add or remove)

This guide offers recommendations for teacher candidates seeking resources for their Kindergarten classrooms and for their own professional learning in early years learning. Classroom and teacher resources that support learning and teaching the expectations associated with the Demonstrating Mathematics Behaviours frame of the Kindergarten program.

Start with real objects and move slowly to diagrams and pictures. Any of the following problem solving strategies will help them work through the four steps above: using objects. acting the problem out. looking for patterns. guessing and checking. drawing pictures. making a graph. teach with projects.

2.4 Thinking about problem solving and innovating Part 3: The program in context. 3.1 Considerations for program planning; 3.2 Building partnerships: Learning and working together Part 4: The learning expectations. 4.1 Using the elements of the expectation charts; 4.2 The overall expectations in the Kindergarten program, by frame

The Kindergarten Program (OME, 2016) uses the following four frames to help organize how we think about children's thinking and the assessment of their learning: Belonging and Contributing, Self-Regulation and Well-Being, Demonstrating Literacy and Math Skills and Problem Solving and Innovating (OME, 2016).

by. Incubate to Innovate. $2.99. Design challenges and problem solving are wonderful ways for students to embrace a problem-solving growth mindset. This ABC Brainstorming Graphic Organizer allows students to truly brainstorm without limits or judgment as they are asked to come up with as many ideas as they can.

Problem Solving and Innovating. Learning Activity. Learning Activities are divided into three sections. Using the text prompts provided, adults should guide children through in the following order: Minds On: Introduces the learning concepts to be explored in the Learning Activity. Action: Offers a focused activity to explore the content and ...

The communication of learning is organized by four areas that reflect how learning happens through children's play and inquiry in kindergarten: belonging and contributing. self-regulation and well-being. demonstrating literacy and mathematics behaviours. problem solving and innovating. In each of these sections educators add personalized ...

2.4 Thinking about problem solving and innovating Part 3: The program in context. 3.1 Considerations for program planning; 3.2 Building partnerships: Learning and working together Part 4: The learning expectations. 4.1 Using the elements of the expectation charts; 4.2 The overall expectations in the Kindergarten program, by frame