Innovative Education in VT

A blog exploring innovative, personalized, student-centered school change

8 methods for reflection in project-based learning

It’s where the learning is.

So, what can this look like? Here are 8 methods for reflection in project-based learning.

Reflection in project and service based learning is often where the big learning happens. Dewey even said, ” We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.”

What are we looking for in a reflection?

Think about having students describe (as inspired by the questions posed on this post at The University of Minnesota):

- WHAT happened

- and NOW what.

Reflection can cover some pretty wide ground.

They can do this in many different ways. This post links the reasons to the Experiential Learning Theory and provides many ideas for how to help students reflect.

1. Exit Tickets

This can be a simple as a notecard where a student quickly responds to a prompt. These are often used as a formative assessment, but can also be used for reflection. The prompt can be content-based, such as drawing an equilateral triangle, to assessing how your group is working at a team (or not). You can also use the exit ticket to have students constantly reflecting back to the driving question. If done regularly, you’ll get to see progress over time.

2. Journals

This old school but very effective tool can be used for a regular reflection activity. Weekly during PBL, students can answer questions such as:

- What have you learned about yourself as a learner this week?

- How can you connect what you are learning to your life?

- And what new questions do you have based on your work this week?

A lot of PBL work is grounded in or draws from a strong STEM background. If this holds true for your PBL project, think about presenting the journal idea as a “lab notebook”: what pieces of data do you want learners to capture, and more importantly, what do you want them to extrapolate from that data?

Students can reflect in the form of a short video that they take themselves on a Chromebook, or with their own devices. You can supply the prompt and students can start talking!

To structure the interview above, the student was asked to answer five questions:

- What’s your project about?

- What has been the most challenging thing about working on this project so far?

- What has been the most satisfying thing about it?

- What advice would you give teachers who want to do this project with their students?

- What advice would you give other students just starting on this project?

When you watch the video, you can see this learner articulate ideas about her learning style as she responds to the prompts. Powerful!

Reflection is not only the written word. It is easy to get stuck into thinking reflection has to be paragraph and pages of text. The student can do a sketch or other piece of art that reflects their feelings, new learning, and how the group work is going. Collages, sewing (paper circuitry?) or painting all offer opportunities to create a reflection on PBL work.

5. Sketchnoting?

Speaking of art, students can sketchnote their reflections. I personally adore this mode of thinking and reflection (as you can see one of my sketchnotes here ). Sketching helps me process and organize new information in a way that writing notes just with words does not.

6. Blogging

Students can write blog posts about their weekly PBL work and include videos, pictures, and link to sites and their work. It can be part of their PLPs, can serve as formative instruction, and can communicate about the project with parents. Win-win!

7. Technology tools that show thinking

There are so many great tech tools that can showcase student reflection. Tools like Wordle can turn concepts into interesting shapes, and Thinglink can illustrate a concept with embedded links. Padlet can show brainstormed or linked topics, and students can make mind maps in Coogle or Prezi.

8. Gallery Walks

Once students have some part of their project completed, gallery wants are a great tool. Students set out their work and peers walk by in rounds, placing sticky notes on or near the work, reflecting about what they liked and still wonder.

The Buck Institute has a great guide as to exactly how to structure a gallery walk around project-based learning .

How do you help student reflect regularly in project based learning?

What works for you? Or what questions do you have?

Related Posts

All about service learning

#vted Reads: The Standards-Based Classroom

How do you measure success with project-based learning?

#vted Reads: with Bill Rich

Trust the Science: Using brain-based learning to upgrade our educational OS

Increasing Student Self-Direction

- ← 3 ways to use Google Forms to streamline your workflow

- Why do action research? →

Katy Farber

Farber joined TIIE after 17 years as a classroom teacher in central Vermont. She is passionate about promoting student and teacher voice, engaging early adolescent students, sharing the power of service learning, and creating inclusive communities where joy, courageous conversations and kindness are the norm. She lives in central Vermont with her husband and two daughters and loves being outside with family and friends, listening to music, writing about the world, and jumping into Vermont ponds and lakes.

4 thoughts on “ 8 methods for reflection in project-based learning ”

Pingback: Project-based learning: Extreme weather PBL unit - Innovation: Education

Pingback: What Makes a Good Exit Ticket | Albert.io

Pingback: Go global with your PBL - Innovation: Education

The closing and/or reflection is one of my weaknesses. I chose this to help and have been given several ideas. I like the thought of asking the students, “What has been the most challenging?”

What do you think? Cancel reply

Support Student Reflection, Critique, and Revision in Project-Based Learning

Let’s go deeper into the key elements of project-based learning and explore strategies to support student reflection, critique, and revision.

Have you ever spent hours of time reflecting on student work? Have you critiqued an assignment or assessment and provided feedback that some students perhaps ultimately never looked at, internalized, or used to make revisions to their work? When students only reflect and receive feedback at the end of a project, this is exactly what happens. Why would students go back and revise anything when the grade is already in and the changes don’t seem to matter? Why reflect on something if the reflection doesn’t result in some type of change?

Project-based learning (PBL) provides an authentic reason for students to actively reflect on what they are doing, seek and provide critique and feedback, and then use that information to revise and change their project in order to improve it. In PBL, reflections, critique, and revisions are not just between a single student and the teacher at the end of the project; students are working together in groups and creating a public product, not just something for themselves. Reflection, critique, and revision are key components of PBL that should be utilized throughout the process, not just at the end.

In PBL, reflection is not just done at the end of a project. We should reflect on where we started, where we ended, and everything in between. In other words, reflection should be ongoing and done throughout the entirety of the project. There are many reasons why reflection is so important in PBL. Below are just a few of the ways in which reflection allows for deeper understanding for students.

- Reflection in PBL allows for deeper understanding. Reflection can happen authentically and multiple times in project-based learning because students have the opportunity to work on answering a driving question over a long period of time. Students are allowed multiple opportunities to reflect, critique, and revise their thinking and work. This allows for much deeper reflection because all of the smaller components relate to the bigger picture or driving question.

- Reflection provides students an authentic opportunity to analyze information, problem-solve, and make decisions. In other words, the reflection matters and will be used to critique and then make revisions. This skill helps prepare students for their careers and future.

- Students are able to identify and explain why they are doing what they are doing and how it is supporting their final project, how they need to change their path so that they are able to achieve their final product, or how they may need to modify their final project. Once again, the reflection leads to critique and revision.

- Students are able to make personal connections to the work they are engaged in, making it more authentic and increasing student ownership and engagement. When students are reflecting on their own work and the work of their group around a public project they are creating, they develop a personal connection to the work and will almost always be more engaged in the project.

- When students reflect on how they were able to persevere and solve a problem that at first seemed so large and complex, they develop perseverance and skills, strategies, and confidence to tackle large (and small) problems. Students have to figure out how to break apart problems into more manageable pieces, ask the right questions to solve the problem, and then design and execute a plan to gather credible information to answer the questions or solve the problem. For more ideas on how to support students searching and seeking information, consider reading the AVID Open Access article, Search and Seek Credible Information: Step 3 of the Searching for ANSWERS Inquiry Process .

When planning out PBL, you should always allow and encourage reflection after any significant learning or creation of work. You can try and preplan these opportunities as much as possible, but remember to also be flexible in creating and encouraging reflection opportunities when appropriate. You and your students might use a project assessment map to identify points of reflection. Consider creating and allowing students to practice specific reflection processes. Below are several ideas that you might consider using with your students.

- Google Docs

- Microsoft Word

- Microsoft OneNote

- Google Slides

- Microsoft PowerPoint

- Google Sites ( Tips )

- Seesaw ( Tips )

- Seesaw Blogs

- Give students an opportunity to reflect on what they used to think as well as how their thinking has changed as a result of inquiry. They can capture this thinking in their learning journal or blog, or they can share their thinking with a partner or small group.

- Use Google Forms , Microsoft Forms , or SurveyMonkey to gather student reflections or have students use one of these programs to gather and organize their own reflections.

- The teacher presents a topic or question, and each student in turn shares something that they have learned about that topic or question.

- In pairs or groups, one student pretends that the others have no idea about a topic and shares or explains what they have learned.

- The teacher asks a reflection question and gives 1 minute for students to think of a response. Then, students are given time to write down what they are thinking. Lastly, students share their thinking in partner pairs or small groups.

Critique and Revision

Reflection becomes more meaningful when it leads to action, and critique and revision are the action portions of the reflection process. However, students need to be taught how to critique work and how to receive feedback, before then using that feedback to revise their work. Teachers need to provide multiple opportunities for students to engage in this work in a safe environment, so they are able to engage in the process effectively on their own once they are in college and working in their careers. Teachers might think about providing an opportunity for students to engage in a low-stakes critique before having them critique each other’s work. For example, ask students to create the classroom layout, and then model how you might use the critique that students provide to revise the classroom layout.

Provide students with a clear understanding of what feedback looks like and sounds like. Feedback should be specific, helpful, and thoughtful. If students make a claim, they need to provide evidence to support their claim. For example, if a student provides feedback saying that something is not very appealing, require them to explain why and offer suggestions to help improve it. Below are several strategies and tools to support critique and revision in PBL.

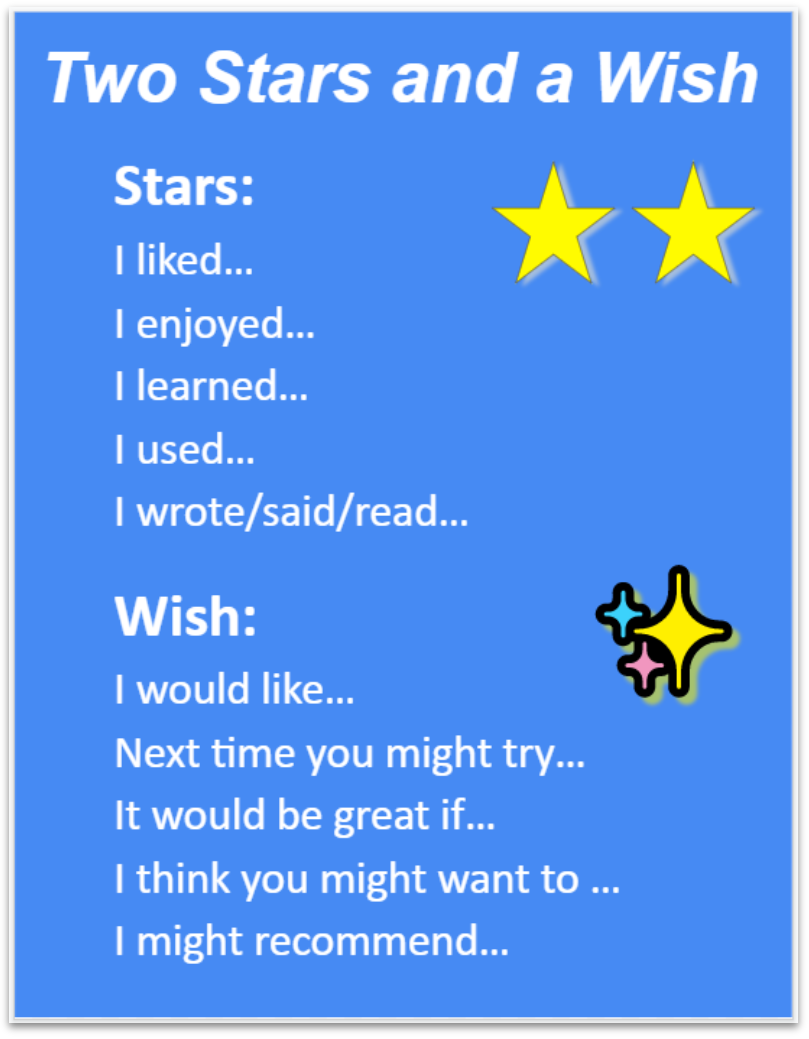

- When giving feedback, students provide the recipient of the feedback with two stars (positive feedback) and a wish (something they wish would be different or changed). You can share this Two Stars and a Wish poster, which includes sentence stems, when engaged in this protocol:

- Students can either share work or present work to a peer or group of students. The students providing feedback can use the Pluses and Wishes template and are given 1–3 minutes to fill in the Pluses column of the worksheet with positive comments and feedback. Students are then given 1–3 minutes to fill in the Wishes column of the worksheet with things that they think there should be more of or less of, or things they think should be changed.

- Analog and digital Gallery Tours allow students to be both givers and receivers of feedback. Consider using this article from PBLWorks to guide you through using Gallery Tours or variations with your students.

- Tuning Protocol: Overview (National School Reform Faculty)

- Tuning Protocol Overview Video (PBLWorks)

- Students Use Tuning Protocol for Critique and Revision in PBL (PBLWorks)

- There are many tools that can support students with critique and revision. Shared documents in Google Workspace (Google Docs, Google Slides, Google Sheets, etc.) and Microsoft 365 (Microsoft Word, Microsoft PowerPoint, Microsoft Excel, etc.) allow multiple people to access, edit, and/or comment on the same document and even at the same time.

- Discussion tools can help manage the sharing of ideas and feedback in virtual conversation threads. Most learning management systems (Canvas, Schoology, Google Classroom, etc.) offer discussion tools with text, audio, and video response options. Some platforms, like Flip ( Tips ), are specifically designed to be video-based. Another example is VoiceThread , where ideas are presented in a slideshow-style format, and participants can respond with audio, text, or video comments.

- Padlet ( Tips )

Throughout the reflection, critique, and revision process in PBL, create opportunities to celebrate students who intentionally reflect on their work, provide good feedback to themselves and others, and use feedback to revise their thinking and make changes to their project. As teachers, we also need to reflect, critique, and revise. We can model reflection, critique, and revision in our work for students and model how we never stop learning and growing. Make sure and provide opportunities for students to provide feedback on different aspects of the PBL process. Ask for feedback on what is going well and what needs to be changed and why. Once you receive feedback, use it to revise your project and future projects. We can continually make PBL better for ourselves and our students if we practice what we teach. For more ideas on how to support students with reflection, critique, and revision, consider reading the AVID Open Access articles or listening to the podcast episodes below:

- Structure Student Reflection Activities Effectively for Remote Learning (article)

- Support Student Reflection With Live Virtual Strategies and Tools (article)

- Support Student Reflection With Self-Paced Virtual Strategies and Tools (article)

- Develop Your Students’ Digital Organization Skills: eFiles, eBinders, and ePortfolios (article)

- Develop Your Students’ Time Management Skills (article)

- Learn and Manage Your Digital Learning Environment (article)

- Establish a Feedback System to Keep Everyone Informed (article collection)

- Collect, Reflect, and Recollect: The Power of eBinders and ePortfolios (podcast episode)

- Engage Students with Project-Based Learning (podcast episode)

- Teacher Insights with Annie Tremonte (podcast episode)

Extend Your Learning

- Critique Protocols Strategy Guide (PBLWorks; sign up to receive this free resource)

- Best Student-Collaboration Tools (Common Sense Education)

- Tools for Project-Based Learning (Common Sense Education)

- Critique and Revision of Student Work in Remote PBL (PBLWorks)

Topic Collections

This course is part of the following collections:.

Did you find this resource useful?

Your rating helps us continue providing useful content in relevant subject areas.

- System Status

- Rest Assured Policy

Select from the list below to add to one of your Journeys, or create a new one.

You haven't created a Journey yet.

Stay in the Know!

Sign up for our weekly newsletter and be the first to receive access to best practice teaching strategies, grab-and-go lessons, and downloadable templates for grades K-12.

PBL in the Mirror: Planning for Student Reflection

WHY should I plan for reflection?

By definition, reflection is serious thought and consideration about an idea or experience. In PBL classrooms, I’ve found the benefits of reflection are astounding! Students experience:

- deepened learning , via

- sharpened analytical skills and

- integration of new knowledge with previous knowledge & experiences

Students who are able to explain why they are completing a task or why the activity is important to their final product are one step closer to the integration of new knowledge.

Upon WHAT should students reflect?

Reflection should be ongoing and throughout the project, not solely at the end once the project is complete. As project designers, we can anticipate many of students’ "Need to Know” questions for the project, to inform our thinking about what students can reflect on. To anticipate the “Need to Know” questions consider:

- What are the necessary questions students will need to pose?

- Which content-based questions do you expect, knowing your students' skill sets?

- What product-based questions may arise?

Let’s look at how some BIE project planning forms can help. Planning with the end in mind is easier when we have already considered what we expect students to experience. The anticipated “Need to Know” questions:

- stem from the Key Knowledge listed on the Project Assessment Map we create;

- help us choose an effective question focus when using the Question Formulation Technique to spark inquiry as we gather students' questions; and

- help us select standard-based checkpoints and learning targets

For example, take a look at the Medical Interns Project Assessment Map (on the BIE website here ) below:

The Key Knowledge, Understanding, and Success Skill listed for the final product are informational writing, circulatory system, and critical thinking. These are the three main areas where we’d anticipate students’ content-based and product-based questions to arise and thereby drive instruction. Herein lie the key learning experiences upon which we can plan for students to reflect. Look closely and we can notice that the key knowledge about the circulatory system is going to be formatively assessed via reflective journal writing.

Let's look deeper into the Medical Interns project design forms to explore this question of planning for student reflection.

HOW will students reflect?

Student reflection can occur both informally and overtly throughout a project. We can integrate reflection into our design:

- On page 2 of the Project Design: Overview form in the Reflections Methods section, individuals, teams, and whole classes can perform any of the following strategies to reflect on the key learning experiences:

- Journal/Learning Logs

- Whole Class Discussions (e.g. Harkness Discussions & Socratic Seminars)

- Focus Groups

- Fishbowl Discussions

- On the Project Design: Student Learning Guide form, Checkpoints/Formative Assessments are important for reflection planning. For each Learning Outcome/Target on the Student Learning Guide, we can strategically scaffold the final products' anchor learning targets by associating each checkpoint with a reflection strategy based on the Key Understanding or Skill.

For example, in the Medical Interns project (above sample is also here), for the Learning Outcome/Target "I can write a report to inform a patient of his/her diagnosis,” reflective journal writing is incorporated as a Checkpoint/Formative Assessment method.

We can also build the culture of our classrooms to incorporate strategies such as the Think-Pair-Share strategy. Think-Pair-Share can be employed to “breadcrumb” students through the reflection process. When given a problem or prompt, students can individually think on their reflection, pair with a partner to discuss their responses and then share aloud to the class where their reflections are similar or where they diverge.

- Once the project is complete, we can use the Self-Reflection on Project Work Handout to help students look into the mirror and reflect on their experience as a whole.

John Dewey said it best: "...we learn from reflecting on experience." Creating a learning experience is all the more purposeful with strategic reflection. Happy Designing!

Don't miss a thing! Get PBL resources, tips and news delivered to your inbox.

Design Education Today pp 61–90 Cite as

Enabling Meaningful Reflection Within Project-Based-Learning in Engineering Design Education

- Thea Morgan 4

- First Online: 17 May 2019

808 Accesses

2 Citations

Group project-based-learning (PBL) is a form of experiential learning in which students develop tacit knowledge about creativity, critical thinking, collaboration and communication, in addition to deepening and contextualising core subject knowledge. Students construct this tacit knowledge by reflecting on their lived experience of meaningful group project work, or rather on their ‘perceptions’ of this lived experience, meaning their prior knowledge, worldview(s) and previous experience will have a strong influence on the outcomes of learning from group PBL. Students of engineering design are heavily influenced by the positivist learning paradigm of engineering science, and so many students struggle to learn effectively from group PBL design experiences, because the constructivist paradigm that underpins this type of learning is not in accord with their cognitive structure. Pedagogical aids to reflection are required to support learning in group PBL design courses in engineering design education. Aids that reveal the underlying learning paradigms within this subject, and their conflicting nature, allowing students to place their own learning in the appropriate epistemological context. It is proposed here that the teaching of philosophy of design , combined with use of reflective learning journals structured using a constructivist inquiry framework, might potentially allow students to access a deeper level of understanding of their own individual approaches to design, by enabling reflection at an ontological level. Philosophy of design serves the purpose of emancipating students from a restrictive worldview by making them aware of multiple paradigms of learning. This chapter presents the argument for such an approach to supporting group PBL and describes a study within a second-year PBL engineering design course, in which this approach has been trialled. The results indicate that a positive impact on reflection and learning has been achieved. Philosophy of design appears to give the students a language and a conceptual structure with which to reflect on personal design activity in constructivist terms, and the reflective learning journals provide an appropriate means to externalise and enhance this reflection through the representation of learning.

- Project-based-learning

- Engineering design

- Philosophy of design

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Adams R, Aleong R, Goldstein M, Solis F (2018) Rendering a multi-dimensional problem space as an unfolding collaborative inquiry process. Des Stud

Google Scholar

Atman C, Eris O, McDonnell J, Cardella M, Borgford-Parnell J (2015) Chapter 11—engineering design education. In: Cambridge handbook of engineering education research, pp 201–226. Cambridge University Press

Ausubel DP, Robinson FG (1969) School learning: an introduction to educational psychology. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

Boyd EM, Fales AW (1983) Reflective learning: key to learning from experience. J Humanist Psychol 23:99–117

Article Google Scholar

Cambridge Dictionary (2015) Cambridge dictionaries online

Chappell A (2006) Using the ‘grieving’ process and learning journals to evaluate students’ responses to problem-based learning in an undergraduate geography curriculum. J Geogr High Educ 30(1):15–31

Crawley EF, Malmqvist J, Lucas WA, Brodeur DR (2011) The CDIO syllabus v2. 0. An updated statement of goals for engineering education. In: Proceedings of 7th international CDIO conference, Copenhagen, Denmark

Cross N (2007) From a design science to a design discipline: understanding designerly ways of knowing and thinking. In: Design research now, pp 41–54. Birkhäuser Basel

Dorst K (2006) Design problems and design paradoxes. Des Issues 22(3):4–17

Dorst K (2015) Frame innovation: create new thinking by design. MIT Press

Downey G, Lucena JUAN (2003) When students resist: ethnography of a senior design experience in engineering education. Int J Eng Educ 19(1):168–176

Dym CL, Agogino AM, Eris O, Frey DD, Leifer LJ (2005) Engineering design thinking, teaching, and learning. J Eng Educ 94(1):103–120

Eisner EW (1993) Forms of understanding and the future of educational research. Educ Res 22(7):5–11

English MC, Kitsantas A (2013) Supporting student self-regulated learning in problem-and project-based learning. Interdiscip J Prob Based Learn 7(2):6

Edström K, Kolmos A (2014) PBL and CDIO: complementary models for engineering education development. Eur J Eng Educ 39(5):539–555

Findeli A (2001) Rethinking design education for the 21st century: theoretical, methodological, and ethical discussion. Des Issues 17(1):5–17

Galle P (2002) Philosophy of design: an editorial introduction. Des Stud 23(3):211–218

Holland D (2014) Process, precedent and community: new learning environments for engineering design. PhD thesis, University of Dublin

Holland D, Walsh C, Bennett GJ (2012) Troublesome knowledge in engineering design courses. In: 6th annual conference of the national academy for the integration of research, teaching and learning, and the 4th biennial threshold concepts conference

Illeris K (2007) How we learn: learning and non-learning in school and beyond. Routledge

Jaskiewicz T, van der Helm A (2017) Progress cards as a tool for supporting reflection, management and analysis of design studio processes. In: DS 88: proceedings of the 19th international conference on engineering and product design education (E&PDE17), Oslo, Norway, 7 & 8 Sept 2017, pp 008–013

Johnson DW, Johnson RT, Smith KA (1998) Active learning: cooperation in the college classroom. Interaction Book Company, 7208 Cornelia Drive, Edina, MN 55435

Kolb D (1984) Experiential learning as the science of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs NPH:editor1984

McDonnell J, Lloyd P, Valkenburg RC (2004) Developing design expertise through the construction of video stories. Des Stud 25(5):509–525

Moon JA (2013) Reflection in learning and professional development: theory and practice. Routledge

Morgan T (2017) Constructivism, complexity, and design: reflecting on group project design behaviour in engineering design education. PhD thesis, University of Bristol

Morgan T, McMahon C (2017) Understanding group design behaviour in engineering design education. In: DS 88: proceedings of the 19th international conference on engineering and product design education (E&PDE17), Oslo, Norway, 7 & 8 Sept 2017, pp 056–061

Morgan T, Tryfonas T (2011) Adoption of a systematic design process: a study of cognitive and social influences on design. In: DS 68–7: proceedings of the 18th international conference on engineering design (ICED11), vol 7

Savin-Baden M (2003) Facilitating problem-based learning. McGraw-Hill Education (UK)

Schön DA (1984) The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Basic Books

Sheppard SD, Macatangay K, Colby A, Sullivan WM (2008) Educating engineers: designing for the future of the field, vol 2. Jossey-Bass

Simons H (2009) Case study research in practice. SAGE publications

Thorpe K (2004) Reflective learning journals: from concept to practice. Reflective Pract 5(3):327–343

Van Manen M (1991) The tact of teaching: the meaning of pedagogical thoughtfulness. New York Press

Wang T (2010) A new paradigm for design studio education. Int J Art Des Educ 29(2):173–183

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CAME School of Engineering, University of Bristol, Clifton, BS8 1TR, UK

Thea Morgan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Thea Morgan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Division of Industrial Design, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Dirk Schaefer

School of Engineering, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK

Graham Coates

School of Engineering and Innovation, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK

Claudia Eckert

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Morgan, T. (2019). Enabling Meaningful Reflection Within Project-Based-Learning in Engineering Design Education. In: Schaefer, D., Coates, G., Eckert, C. (eds) Design Education Today. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17134-6_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17134-6_4

Published : 17 May 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-17133-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-17134-6

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Reflective Practice in Project-based Culture Learning: Content and Quality of Reflection

2019, English Language Teaching

Kim, Mi Kyong. (2019). Reflective practice in project-based culture learning: Content and quality of reflection. English Language Teaching, 31(4), 67-94. Culture learning (CL) needs alternatives beyond traditional teacher-transmitted approaches for reflective practice and intercultural development. This study explored the potential of project-based learning (PBL) as an alternative CL to practice reflection through student-driven inquiry. Specifically, the study examined content and quality of reflection, adapting two conceptual frameworks: focusing areas of reflection-public theory, private theory, feelings, action plan, and feedback (Bain, Ballantyne, Packer, & Mills, 1999) and reflective indicators-'additional perspectives'; 'own values'; and 'larger contexts' (Jay & Johnson, 2002). The study used three data sources from eleven students: journals, written reflections, and interviews. The results showed as follows. First, PBL helped the students focus on four contents of reflection other than public theory (i.e., non-reflection): private theory particularly while problematizing cultural topics; feelings about student-centered inquiry toward knowledge construction and insights into cultural content; action plans to pursue deeper cultural knowledge, overall language proficiency, and plans of PBL classes in future classrooms; and communication with teacher such as seeking views on cultural issues. Second, the student-driven inquiry approach helped the students gain 'additional perspectives' on learning about three areas: cultural content, English and presentation skills, and PBL as a teaching approach. Similarly, the approach fostered the students to apply their 'own values' in learning about the above three areas. The inquiry approach also promoted the students to examine their learning about primarily culture content in 'larger contexts.' (228 words)

Related Papers

Springer eBooks

Margrit E Kaufmann

Paula Garrett-Rucks

Fostering and assessing language learners’ cultural understanding is a daunting task, particularly at the early stages of language learning with target‐language instruction. The purpose of this study was to explore the development of beginning French language learners’ intercultural understanding in a computer‐mediated environment where students discussed online cultural instruction among peers, in English, outside of formal instructional time. Discourse analyses of the discussion transcripts revealed sizable growth in learners’ development of intercultural sensitivity in response to different types of online instructional materials. Volunteer participants provided additional insight into the influences of the instructional materials on changes in their worldviews in post‐discussion interviews. In addition to providing evidence of effective uses of technology to resolve conflicts between target language use and deep cultural learning in the beginning world language curriculum, findings from this study document the application of an assessment model used to measure learners’ development of intercultural understanding.

Canadian Journal of Education

Anna Kirova

This study investigates the infusion of intercultural inquiry into subject-area curriculum courses in a teacher education program. Drawing from data that include questionnaires, student assignments, and interviews, the research focuses on how student teachers responded to critical explorations of diversity within curriculum courses in second language education, early childhood education, and art education. The findings indicate that most student teachers had limited prior experiences with diversity, leading to anxiety and uncertainty about their preparedness to work in diverse classrooms. Although many were receptive to intercultural inquiry and perceived its value, some resisted efforts to critically challenge social inequality and privilege. Key words: teacher education, diversity, multicultural education, intercultural inquiry Cet article porte sur l'integration de la recherche interculturelle dans un programme de formation a l'enseignement. Puisant dans des donnees tiree...

Arona Dison

This research was undertaken as the first cycle of an' action research project. The aim was to develop a course within the English Language 1 for Academic Purposes (ELAP) course at _ Rhodes University, which would facilitate the conceptual development of students in relation to the topic of Culture. The implementation of the course was researched, ~ using students' writing, interviews, staff meeting discussions and video-taping of certain classes. Ten students volunteered to 'be researched'. The types of initial 'commonsense' understandings of culture held by students are outlined and the conceptual development which they underwent in relation to Culture is examined. Students' perceptions of the approaches to learning required in ELAP and the Culture course in particular are explored. The involvement of the ELAP tutors in the course and in the research was a learning experience for them, and this became-another focus of the research._ .... -." The fi...

Mandy Hommel

Reflection in classroom learning leads to a deeper understanding and helps to connect knowledge with application situations. Socially initiated reflection can be observed as a lesson event embedded in Review, Elaboration, and Summarization. Questions constitute a primary catalyst for stimulating reflection, particularly in classroom settings. This study 1 investigates reflection events and related questioning behaviour of students and teachers by undertaking a comparative analysis of video data from the Learner's Perspective Study (LPS; Clarke, Keitel, & Shimizu 2006) in classrooms in Australia, Germany, Japan, and the USA.

International Journal of Educational Research

Marie Himes

REGISTER JOURNAL IAIN Salatiga

ENGLISH ABSTRACT Culture is an integral part of language study, but the field has yet to put forward a coherent theoretical argument for how culture can or should be incorporated in language education. In an effort to remedy this situation, this paper reviews literature on the teaching of culture, drawing on Larzén's (2005) identification of three pedagogies used to teach about culture within the language classroom: through a pedagogy of information, a pedagogy of preparation, and a pedagogy of encounter. The pedagogy of information takes a cognitive orientation, framing culture as factual knowledge, with a focus on the teacher as the transmitter of knowledge. The pedagogy of preparation portrays culture as skills, and aims to help students develop the sociocultural, pragmatic, and strategic competence necessary for interactions with native speakers. The pedagogy of encounter takes an intercultural approach, with an affective orientation, and aims to help students develop tolerance, empathy, and an awareness of their own and others' perspectives, and the emergent nature of culture. Using these three pedagogies as a conceptual framework, this paper reviews scholarship in support and critique of each type of cultural teaching. Because each of these three pedagogies continues to be used in various contexts worldwide, a clear understanding of the beliefs systems underpinning the belief systems of teachers and learners is essential. INDONESIAN ABSTRACT Budaya merupakan bagian integral dari studi bahasa, namun khalayak belum mengemukakan argumen teoritis yang koheren untuk Tabitha Kidwell 222 bagaimana budaya dapat atau harus digabungkan dalam pendidikan bahasa. Dalam upaya memperbaiki situasi ini, makalah ini mengulas literatur tentang ajaran budaya, dengan mengacu pada identifikasi tiga pedagogi Larzén (2005) yang digunakan untuk mengajarkan tentang budaya di dalam kelas bahasa: melalui pedagogi informasi, pedagogi persiapan, dan pedagogi perjumpaan Pedagogi informasi mengambil orientasi kognitif, membingkai budaya sebagai pengetahuan faktual, dengan fokus pada guru sebagai pemancar pengetahuan. Pedagogi persiapan menggambarkan budaya sebagai keterampilan, dan bertujuan untuk membantu siswa mengembangkan kompetensi sosiokultural, pragmatis, dan strategis yang diperlukan untuk interaksi dengan penutur asli. Pedagogi pertemuan mengambil pendekatan antar budaya, dengan orientasi afektif, dan bertujuan untuk membantu siswa mengembangkan toleransi, empati, dan kesadaran akan perspektif mereka sendiri dan orang lain, dan sifat budaya yang muncul. Dengan menggunakan ketiga pedagogi ini sebagai kerangka konseptual, makalah ini mengulas pustaka untuk mendukung dan mengkritik setiap jenis pengajaran budaya. Karena masing-masing dari ketiga pedagogi ini terus digunakan dalam berbagai konteks di seluruh dunia, pemahaman yang jelas tentang sistem kepercayaan yang mendasari sistem kepercayaan guru dan pelajar sangat penting.

The 14th International Conference on Chinese Language Pedagogy proceedings

Kaishan Kong

This paper described a Five-Dimension Reflective Pedagogy Model used in a professional development program on Chinese culture teaching. It examined impacts of the Model on teachers' attitudes towards reflection in teaching and understanding of culture teaching in Chinese as a second language classrooms. Data included pre-and post-program reflections, video-taped cultural road map presentations, daily reflective writing, and lesson plans. The Model led to teachers' positive attitudes towards the use of reflection in teaching, enhanced confidence in culture teaching, and complicated understandings of culture.

Javelo Jones

During this action research study of Algebra I teachers at a high school in the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex, I have presented information related to the implementation of inquiry-based learning (IBL) and the findings from classroom observations and a focus group interview. The purpose of this study was to identify the effect of IBL instructional practices on the cultural and academic environment in mathematics classrooms. I sought first to understand teachers’ perceptions of the usefulness of past professional development sessions, the climate and culture of their classroom, and their perceptions about how African American students learn. Teachers then participated in professional developments to learn to implement IBL practices effectively. After observing teachers utilizing the methods in their classrooms, teachers provided feedback on their experience and changes to their perceptions, modifications, and improvements to professional development, and providing culturally responsive...

Janet Sayers

This paper discusses the rapid internationalization (mainly by Chinese students) of a business degree and its impact on one course in that degree programme. The purpose of the course is to develop reflective capabilities in students and the paper considers how staff involved in the course reflected on their own practice and made changes to the course to accommodate the new contingent of students from outside the host country. Initial perceptions by staff of the Chinese-originating students are described, as are tensions that emerged regarding the philosophical/cultural assumptions under-pinning the course. The paper shows how staff reconsidered their teaching practices and assessment tools and reports on an empirical study conducted to explore how students experienced the courses’ teaching methods and assessment. The course’s reflective philosophy was adjusted to accommodate the new student cohort.

RELATED PAPERS

Open Journal of Statistics

MUHAMAD SAFIIH LOLA

Journal of Medicinal Chemistry

Arianna Granese

Mathematical and Computer Modelling of Dynamical Systems

Lino Marques

Jurnal Kesmas Jambi

hairil akbar

Pedro Henrique Gonçalves

Zoo de cristal

Nieves García-Tejedor

Journal of Korean Powder Metallurgy Institute

Sung-Soo Ryu

Iranian Journal of Ichthyology

tapan barik

AEU - International Journal of Electronics and Communications

Georgia Tsirimokou

European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology

Tamar Peretz

Pakistan Journal of Nutrition

Muhammad Farhan

European Respiratory Journal

Jurnal Dinamika Hukum

Tenang Haryanto

International Journal of Information Technology

preeti kaur

Clinical Cancer Research

Macarena Vargas

Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology

Jian-jiang Zhong

Catalysis Letters

Jong Wun Jung

European Journal of Social Psychology

Journal of Alloys and Compounds

Ladislav Havela

Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International

Advanced Materials Interfaces

Nobuhiro Kosugi

José María DAGNINO PASTORE

bestiboo official

Sulma Paola Vera Monroy

Advances in Interventional Cardiology

Nikola Topuzov

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Our Mission

A Simple, Effective Framework for PBL

This plan was designed to guide teachers who haven’t had formal training in project-based learning.

Teachers trying their hand at project-based learning (PBL) may be uncertain as to how to strengthen their project ideas and make them the best possible learning experiences for students. For teachers without access to training, a research-informed framework for PBL and a few strategies for defining and organizing the student experience can considerably improve outcomes.

The High Quality PBL (HQPBL) framework , when executed effectively, provides elements like authenticity, project management, and public products for educators to use for creating the conditions for learning to stick and continue after projects.

For example, content or elective teachers can increase authenticity in projects by bringing in industry experts (e.g., engineers, environmental scientists, computer programmers, activists) at the launch to introduce the type of work that students will be learning to do.

Teachers can also help students improve their work by having them develop public products with a call to action advocating for causes they care about and instructing audiences of community members on the next steps to take.

Before diving into the framework, let’s quickly dispel two of the biggest misconceptions and roadblocks to attempting PBL that I’ve heard from educators.

Common PBL Hurdles

1. I have to prepare my students for exams (or cover lots of content) and can’t dedicate an entire school year or semester to planning or teaching this way. I agree—do not abandon the teaching practice you have carefully honed. Instead, implement one project a semester, connect it to learning in your area as best as possible, and implement it for no more than two to three weeks at a time.

2. I’m a content teacher and am not exactly sure how to make real-world projects. I admit this can be tricky the first time around. Focus on important problems in the community (e.g., health, financial inclusion, environment ). Let the kids pick the issue(s) they want to tackle and develop a plan for knowing their topic inside and out, along with solutions.

See this video example where educator Jose Gonzalez of Compton Unified School District in California implemented a terrific interdisciplinary project: allowing students to choose their path to advocate for change in their communities.

Using the High Quality PBL Framework

Established in 2018, the HQPBL framework is a consensus of both the research and the accumulated practice of PBL leaders and experts worldwide. It can be used with learners of all ages, but it’s particularly well-suited to middle and high school students who are passionate about solving meaningful problems.

The framework is designed to provide educators who have no access to formal training with resources that enable them to enact PBL practices on their own by setting the criteria for the student experience using the following six elements.

1. Intellectual challenge and accomplishment. Students investigate challenging problems or issues over an extended period of time. I recommend two to three weeks for teachers new to the process. Throughout this period, they should develop the essential content knowledge and concepts central to academic disciplines. Therefore, I encourage teachers to have students use the thinking routines and problem-solving strategies they typically use (e.g., Blooms, design thinking, scientific Inquiry, computational thinking) to think critically in their content area.

2. Authenticity. Projects focus on real-world connections that are meaningful to students—including their cultures and backgrounds . Additionally, the tools and techniques they employ mimic those used by career professionals. By inviting experts into the classroom and having students assume authentic career roles (e.g., engineer, doctor, auto technician), they can learn valuable career pathway options and see how their work and the solutions they develop impact others.

3. Public product. The students’ final products are presented to the public as a culminating event. This means the work they produce is seen and discussed with the broader community—including parents, industry professionals, other classes, administrators, and community members.

When students know that others will see their work, this may motivate them to put their best foot forward. Public products are not limited to presentation nights—student work can be displayed as public art, as exhibits, or online via social media, YouTube, and safe school websites.

4. Collaboration. Working with others is a PBL hallmark where students collaborate with both adults and their peers in a number of different ways. Adults serve as mentors and guides and can include teachers, community members, or outside experts. In teamwork between students , each learner contributes their individual skills and talents. I find that learners of all ages need good collaboration tools— team contracts and task lists are an excellent place to start.

5. Project management. Students help manage the project process, using tools and strategies similar to those used by adults. I’ve seen teachers using several tools for assisting learners in keeping their work organized—good ones include scrum boards , using design thinking during the ideation process, and maintaining important documents in Google Classroom and Schoology.

I’ve also found that some learners benefit greatly from keeping a daily schedule before attempting to help manage projects. As students’ capacity for self-management increases, teachers take on the role of facilitator, helping guide students through the process rather than directing it.

6. Reflection. The learning process is enhanced by frequent reflections that help students think about their progress and how to improve their work. I like to have them complete products in drafts and jump-start reflection through critique protocols —this helps learners retain content and skills longer and gives them the awareness of how they learn best by using reflection for metacognition. Other methods for reflection may include journaling, the 3-2-1 strategy , and the one-minute paper .

“Framework first, mindset second” is a powerful principle I use for helping colleagues understand that having good general guidelines for doing something new is the prerequisite to developing second-nature expertise. The HQPBL framework can be a good place to start for beginning to use PBL as a research-informed instructional approach.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Reflective writing is a process of identifying, questioning, and critically evaluating course-based learning opportunities, integrated with your own observations, experiences, impressions, beliefs, assumptions, or biases, and which describes how this process stimulated new or creative understanding about the content of the course.

A reflective paper describes and explains in an introspective, first person narrative, your reactions and feelings about either a specific element of the class [e.g., a required reading; a film shown in class] or more generally how you experienced learning throughout the course. Reflective writing assignments can be in the form of a single paper, essays, portfolios, journals, diaries, or blogs. In some cases, your professor may include a reflective writing assignment as a way to obtain student feedback that helps improve the course, either in the moment or for when the class is taught again.

How to Write a Reflection Paper . Academic Skills, Trent University; Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8.

Benefits of Reflective Writing Assignments

As the term implies, a reflective paper involves looking inward at oneself in contemplating and bringing meaning to the relationship between course content and the acquisition of new knowledge . Educational research [Bolton, 2010; Ryan, 2011; Tsingos-Lucas et al., 2017] demonstrates that assigning reflective writing tasks enhances learning because it challenges students to confront their own assumptions, biases, and belief systems around what is being taught in class and, in so doing, stimulate student’s decisions, actions, attitudes, and understanding about themselves as learners and in relation to having mastery over their learning. Reflection assignments are also an opportunity to write in a first person narrative about elements of the course, such as the required readings, separate from the exegetic and analytical prose of academic research papers.

Reflection writing often serves multiple purposes simultaneously. In no particular order, here are some of reasons why professors assign reflection papers:

- Enhances learning from previous knowledge and experience in order to improve future decision-making and reasoning in practice . Reflective writing in the applied social sciences enhances decision-making skills and academic performance in ways that can inform professional practice. The act of reflective writing creates self-awareness and understanding of others. This is particularly important in clinical and service-oriented professional settings.

- Allows students to make sense of classroom content and overall learning experiences in relation to oneself, others, and the conditions that shaped the content and classroom experiences . Reflective writing places you within the course content in ways that can deepen your understanding of the material. Because reflective thinking can help reveal hidden biases, it can help you critically interrogate moments when you do not like or agree with discussions, readings, or other aspects of the course.

- Increases awareness of one’s cognitive abilities and the evidence for these attributes . Reflective writing can break down personal doubts about yourself as a learner and highlight specific abilities that may have been hidden or suppressed due to prior assumptions about the strength of your academic abilities [e.g., reading comprehension; problem-solving skills]. Reflective writing, therefore, can have a positive affective [i.e., emotional] impact on your sense of self-worth.

- Applying theoretical knowledge and frameworks to real experiences . Reflective writing can help build a bridge of relevancy between theoretical knowledge and the real world. In so doing, this form of writing can lead to a better understanding of underlying theories and their analytical properties applied to professional practice.

- Reveals shortcomings that the reader will identify . Evidence suggests that reflective writing can uncover your own shortcomings as a learner, thereby, creating opportunities to anticipate the responses of your professor may have about the quality of your coursework. This can be particularly productive if the reflective paper is written before final submission of an assignment.

- Helps students identify their tacit [a.k.a., implicit] knowledge and possible gaps in that knowledge . Tacit knowledge refers to ways of knowing rooted in lived experience, insight, and intuition rather than formal, codified, categorical, or explicit knowledge. In so doing, reflective writing can stimulate students to question their beliefs about a research problem or an element of the course content beyond positivist modes of understanding and representation.

- Encourages students to actively monitor their learning processes over a period of time . On-going reflective writing in journals or blogs, for example, can help you maintain or adapt learning strategies in other contexts. The regular, purposeful act of reflection can facilitate continuous deep thinking about the course content as it evolves and changes throughout the term. This, in turn, can increase your overall confidence as a learner.

- Relates a student’s personal experience to a wider perspective . Reflection papers can help you see the big picture associated with the content of a course by forcing you to think about the connections between scholarly content and your lived experiences outside of school. It can provide a macro-level understanding of one’s own experiences in relation to the specifics of what is being taught.

- If reflective writing is shared, students can exchange stories about their learning experiences, thereby, creating an opportunity to reevaluate their original assumptions or perspectives . In most cases, reflective writing is only viewed by your professor in order to ensure candid feedback from students. However, occasionally, reflective writing is shared and openly discussed in class. During these discussions, new or different perspectives and alternative approaches to solving problems can be generated that would otherwise be hidden. Sharing student's reflections can also reveal collective patterns of thought and emotions about a particular element of the course.

Bolton, Gillie. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development . London: Sage, 2010; Chang, Bo. "Reflection in Learning." Online Learning 23 (2019), 95-110; Cavilla, Derek. "The Effects of Student Reflection on Academic Performance and Motivation." Sage Open 7 (July-September 2017): 1–13; Culbert, Patrick. “Better Teaching? You Can Write On It “ Liberal Education (February 2022); McCabe, Gavin and Tobias Thejll-Madsen. The Reflection Toolkit . University of Edinburgh; The Purpose of Reflection . Introductory Composition at Purdue University; Practice-based and Reflective Learning . Study Advice Study Guides, University of Reading; Ryan, Mary. "Improving Reflective Writing in Higher Education: A Social Semiotic Perspective." Teaching in Higher Education 16 (2011): 99-111; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8; What Benefits Might Reflective Writing Have for My Students? Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse; Rykkje, Linda. "The Tacit Care Knowledge in Reflective Writing: A Practical Wisdom." International Practice Development Journal 7 (September 2017): Article 5; Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning . Center for Writing, University of Minnesota.

How to Approach Writing a Reflection Paper

Thinking About Reflective Thinking

Educational theorists have developed numerous models of reflective thinking that your professor may use to frame a reflective writing assignment. These models can help you systematically interpret your learning experiences, thereby ensuring that you ask the right questions and have a clear understanding of what should be covered. A model can also represent the overall structure of a reflective paper. Each model establishes a different approach to reflection and will require you to think about your writing differently. If you are unclear how to fit your writing within a particular reflective model, seek clarification from your professor. There are generally two types of reflective writing assignments, each approached in slightly different ways.

1. Reflective Thinking about Course Readings

This type of reflective writing focuses on thoughtfully thinking about the course readings that underpin how most students acquire new knowledge and understanding about the subject of a course. Reflecting on course readings is often assigned in freshmen-level, interdisciplinary courses where the required readings examine topics viewed from multiple perspectives and, as such, provide different ways of analyzing a topic, issue, event, or phenomenon. The purpose of reflective thinking about course readings in the social and behavioral sciences is to elicit your opinions, beliefs, and feelings about the research and its significance. This type of writing can provide an opportunity to break down key assumptions you may have and, in so doing, reveal potential biases in how you interpret the scholarship.

If you are assigned to reflect on course readings, consider the following methods of analysis as prompts that can help you get started :

- Examine carefully the main introductory elements of the reading, including the purpose of the study, the theoretical framework being used to test assumptions, and the research questions being addressed. Think about what ideas stood out to you. Why did they? Were these ideas new to you or familiar in some way based on your own lived experiences or prior knowledge?

- Develop your ideas around the readings by asking yourself, what do I know about this topic? Where does my existing knowledge about this topic come from? What are the observations or experiences in my life that influence my understanding of the topic? Do I agree or disagree with the main arguments, recommended course of actions, or conclusions made by the author(s)? Why do I feel this way and what is the basis of these feelings?

- Make connections between the text and your own beliefs, opinions, or feelings by considering questions like, how do the readings reinforce my existing ideas or assumptions? How the readings challenge these ideas or assumptions? How does this text help me to better understand this topic or research in ways that motivate me to learn more about this area of study?

2. Reflective Thinking about Course Experiences

This type of reflective writing asks you to critically reflect on locating yourself at the conceptual intersection of theory and practice. The purpose of experiential reflection is to evaluate theories or disciplinary-based analytical models based on your introspective assessment of the relationship between hypothetical thinking and practical reality; it offers a way to consider how your own knowledge and skills fit within professional practice. This type of writing also provides an opportunity to evaluate your decisions and actions, as well as how you managed your subsequent successes and failures, within a specific theoretical framework. As a result, abstract concepts can crystallize and become more relevant to you when considered within your own experiences. This can help you formulate plans for self-improvement as you learn.

If you are assigned to reflect on your experiences, consider the following questions as prompts to help you get started :

- Contextualize your reflection in relation to the overarching purpose of the course by asking yourself, what did you hope to learn from this course? What were the learning objectives for the course and how did I fit within each of them? How did these goals relate to the main themes or concepts of the course?

- Analyze how you experienced the course by asking yourself, what did I learn from this experience? What did I learn about myself? About working in this area of research and study? About how the course relates to my place in society? What assumptions about the course were supported or refuted?

- Think introspectively about the ways you experienced learning during the course by asking yourself, did your learning experiences align with the goals or concepts of the course? Why or why do you not feel this way? What was successful and why do you believe this? What would you do differently and why is this important? How will you prepare for a future experience in this area of study?

NOTE: If you are assigned to write a journal or other type of on-going reflection exercise, a helpful approach is to reflect on your reflections by re-reading what you have already written. In other words, review your previous entries as a way to contextualize your feelings, opinions, or beliefs regarding your overall learning experiences. Over time, this can also help reveal hidden patterns or themes related to how you processed your learning experiences. Consider concluding your reflective journal with a summary of how you felt about your learning experiences at critical junctures throughout the course, then use these to write about how you grew as a student learner and how the act of reflecting helped you gain new understanding about the subject of the course and its content.

ANOTHER NOTE: Regardless of whether you write a reflection paper or a journal, do not focus your writing on the past. The act of reflection is intended to think introspectively about previous learning experiences. However, reflective thinking should document the ways in which you progressed in obtaining new insights and understandings about your growth as a learner that can be carried forward in subsequent coursework or in future professional practice. Your writing should reflect a furtherance of increasing personal autonomy and confidence gained from understanding more about yourself as a learner.

Structure and Writing Style

There are no strict academic rules for writing a reflective paper. Reflective writing may be assigned in any class taught in the social and behavioral sciences and, therefore, requirements for the assignment can vary depending on disciplinary-based models of inquiry and learning. The organization of content can also depend on what your professor wants you to write about or based on the type of reflective model used to frame the writing assignment. Despite these possible variations, below is a basic approach to organizing and writing a good reflective paper, followed by a list of problems to avoid.

Pre-flection

In most cases, it's helpful to begin by thinking about your learning experiences and outline what you want to focus on before you begin to write the paper. This can help you organize your thoughts around what was most important to you and what experiences [good or bad] had the most impact on your learning. As described by the University of Waterloo Writing and Communication Centre, preparing to write a reflective paper involves a process of self-analysis that can help organize your thoughts around significant moments of in-class knowledge discovery.

- Using a thesis statement as a guide, note what experiences or course content stood out to you , then place these within the context of your observations, reactions, feelings, and opinions. This will help you develop a rough outline of key moments during the course that reflect your growth as a learner. To identify these moments, pose these questions to yourself: What happened? What was my reaction? What were my expectations and how were they different from what transpired? What did I learn?

- Critically think about your learning experiences and the course content . This will help you develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding about why these moments were significant or relevant to you. Use the ideas you formulated during the first stage of reflecting to help you think through these moments from both an academic and personal perspective. From an academic perspective, contemplate how the experience enhanced your understanding of a concept, theory, or skill. Ask yourself, did the experience confirm my previous understanding or challenge it in some way. As a result, did this highlight strengths or gaps in your current knowledge? From a personal perspective, think introspectively about why these experiences mattered, if previous expectations or assumptions were confirmed or refuted, and if this surprised, confused, or unnerved you in some way.

- Analyze how these experiences and your reactions to them will shape your future thinking and behavior . Reflection implies looking back, but the most important act of reflective writing is considering how beliefs, assumptions, opinions, and feelings were transformed in ways that better prepare you as a learner in the future. Note how this reflective analysis can lead to actions you will take as a result of your experiences, what you will do differently, and how you will apply what you learned in other courses or in professional practice.

Basic Structure and Writing Style

Reflective Background and Context

The first part of your reflection paper should briefly provide background and context in relation to the content or experiences that stood out to you. Highlight the settings, summarize the key readings, or narrate the experiences in relation to the course objectives. Provide background that sets the stage for your reflection. You do not need to go into great detail, but you should provide enough information for the reader to understand what sources of learning you are writing about [e.g., course readings, field experience, guest lecture, class discussions] and why they were important. This section should end with an explanatory thesis statement that expresses the central ideas of your paper and what you want the readers to know, believe, or understand after they finish reading your paper.

Reflective Interpretation

Drawing from your reflective analysis, this is where you can be personal, critical, and creative in expressing how you felt about the course content and learning experiences and how they influenced or altered your feelings, beliefs, assumptions, or biases about the subject of the course. This section is also where you explore the meaning of these experiences in the context of the course and how you gained an awareness of the connections between these moments and your own prior knowledge.

Guided by your thesis statement, a helpful approach is to interpret your learning throughout the course with a series of specific examples drawn from the course content and your learning experiences. These examples should be arranged in sequential order that illustrate your growth as a learner. Reflecting on each example can be done by: 1) introducing a theme or moment that was meaningful to you, 2) describing your previous position about the learning moment and what you thought about it, 3) explaining how your perspective was challenged and/or changed and why, and 4) introspectively stating your current or new feelings, opinions, or beliefs about that experience in class.

It is important to include specific examples drawn from the course and placed within the context of your assumptions, thoughts, opinions, and feelings. A reflective narrative without specific examples does not provide an effective way for the reader to understand the relationship between the course content and how you grew as a learner.

Reflective Conclusions

The conclusion of your reflective paper should provide a summary of your thoughts, feelings, or opinions regarding what you learned about yourself as a result of taking the course. Here are several ways you can frame your conclusions based on the examples you interpreted and reflected on what they meant to you. Each example would need to be tied to the basic theme [thesis statement] of your reflective background section.

- Your reflective conclusions can be described in relation to any expectations you had before taking the class [e.g., “I expected the readings to not be relevant to my own experiences growing up in a rural community, but the research actually helped me see that the challenges of developing my identity as a child of immigrants was not that unusual...”].

- Your reflective conclusions can explain how what you learned about yourself will change your actions in the future [e.g., “During a discussion in class about the challenges of helping homeless people, I realized that many of these people hate living on the street but lack the ability to see a way out. This made me realize that I wanted to take more classes in psychology...”].

- Your reflective conclusions can describe major insights you experienced a critical junctures during the course and how these moments enhanced how you see yourself as a student learner [e.g., "The guest speaker from the Head Start program made me realize why I wanted to pursue a career in elementary education..."].

- Your reflective conclusions can reconfigure or reframe how you will approach professional practice and your understanding of your future career aspirations [e.g.,, "The course changed my perceptions about seeking a career in business finance because it made me realize I want to be more engaged in customer service..."]

- Your reflective conclusions can explore any learning you derived from the act of reflecting itself [e.g., “Reflecting on the course readings that described how minority students perceive campus activities helped me identify my own biases about the benefits of those activities in acclimating to campus life...”].

NOTE: The length of a reflective paper in the social sciences is usually less than a traditional research paper. However, don’t assume that writing a reflective paper is easier than writing a research paper. A well-conceived critical reflection paper often requires as much time and effort as a research paper because you must purposeful engage in thinking about your learning in ways that you may not be comfortable with or used to. This is particular true while preparing to write because reflective papers are not as structured as a traditional research paper and, therefore, you have to think deliberately about how you want to organize the paper and what elements of the course you want to reflect upon.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not limit yourself to using only text in reflecting on your learning. If you believe it would be helpful, consider using creative modes of thought or expression such as, illustrations, photographs, or material objects that reflects an experience related to the subject of the course that was important to you [e.g., like a ticket stub to a renowned speaker on campus]. Whatever non-textual element you include, be sure to describe the object's relevance to your personal relationship to the course content.

Problems to Avoid

A reflective paper is not a “mind dump” . Reflective papers document your personal and emotional experiences and, therefore, they do not conform to rigid structures, or schema, to organize information. However, the paper should not be a disjointed, stream-of-consciousness narrative. Reflective papers are still academic pieces of writing that require organized thought, that use academic language and tone , and that apply intellectually-driven critical thinking to the course content and your learning experiences and their significance.

A reflective paper is not a research paper . If you are asked to reflect on a course reading, the reflection will obviously include some description of the research. However, the goal of reflective writing is not to present extraneous ideas to the reader or to "educate" them about the course. The goal is to share a story about your relationship with the learning objectives of the course. Therefore, unlike research papers, you are expected to write from a first person point of view which includes an introspective examination of your own opinions, feelings, and personal assumptions.

A reflection paper is not a book review . Descriptions of the course readings using your own words is not a reflective paper. Reflective writing should focus on how you understood the implications of and were challenged by the course in relation to your own lived experiences or personal assumptions, combined with explanations of how you grew as a student learner based on this internal dialogue. Remember that you are the central object of the paper, not the research materials.

A reflective paper is not an all-inclusive meditation. Do not try to cover everything. The scope of your paper should be well-defined and limited to your specific opinions, feelings, and beliefs about what you determine to be the most significant content of the course and in relation to the learning that took place. Reflections should be detailed enough to covey what you think is important, but your thoughts should be expressed concisely and coherently [as is true for any academic writing assignment].