My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

Narrative Speech [With Topics and Examples]

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

Narrative Speech Topics

- Your Events, Life Lessons, Personal Experiences, Rituals and Your Identity.

The main point is that you are talking about yourself.

Your thoughts, feelings, ideas, views, opinions and events are the leading ladies in this special public speaking speech writing process.

In this article:

Your Life Lessons

Experiences, narrative speech writing tips, 10 fast showcases.

Here are example narrative speech topics you can share in a speech class or other public speaking assignment in high school, college education. Narrow the speech topics appropriately to the public speaking occasion rules with the specialized checklist I have composed with seven narrative speech writing tips .

The checks and tips also serve as hooks for to narrate a paragraph in an college essay.

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

The backbone of my advice is: try to keep the story devoted and dedicated. If you find it hard to develop speech topics for narration purposes and you are a little bit overwhelmed, then try ten ways I’ve developed to find narrative speech topics .

Most students mark out an event in their speeches and essays. An event that stipulate a great step in life or an important moment that has impact on your prosperity or lifestyle from that particular period:

E.g. An accident or remarkable positive event that changed my life. The birth of my brother, sister or other relative and the impact on our household and family-life. My first day at high school or college. The decision I regret most at my school or in my professional job career. My day of graduation (If you have not yet graduated from an educational institution, describe your hardworking and your planning efforts to achieve the qualification). My first serious date with my boyfriend / girlfriend. A significant family event in the summer. A memorable vacation. A historical event that impressed me. The day I will move overseas. A milestone that seemed bad but turned out to be good. My heroic sports moment at the campus field.

Take personal growth and development as starting point. Widen the horizon of the audience to a greater extent with narrative speech topics on wisdom. Construct a life lesson yourself, based on a practical wisdom acquired by own experience, or one you have been be introduced to by someone else:

E.g. The influence of a special person on my behavior. How I have dealed with a difficult situation. What lessons I have learned through studying the genealogy of my family. A prejudice that involved me. An Eureka moment: you suddenly understood how something works in life you had been struggling with earlier. How you helped someonelse and what you learned from her or him, and from the situation.

For this kind of public speaking training begin with mentioning intuitively the emotions you feel (in senses and mind) and the greater perception of the circumstances that lead to apprehension of a precarious situation:

E.g. My most frustrating moment. How you handled in an emergency situation. How I break up with my love. A narrow escape. A moment when you did something that took a lot of courage. A time when you choose to go your own way and did not follow the crowd. How I stood up for my beliefs. The day you rebelled with a decision concerning you. How you cope with your nerves recently – think about fear of public speaking and how you mastered and controlled it in the end. What happened when you had a disagreement with your teacher or instructor in class, this triggering narrative speech idea is great for speech class, because everyone will recognize the situation.

This theoretic method is close related to the previous tips. However, there is one small but significant difference.

Let’s define rituals as a system of prescribed procedures or actions of a group to which you belong. In that case you have the perfect starters to speak out feelings .

Complement the ritual with your own feelings and random thoughts that bubble up when you are practicing the ritual:

E.g. How you usually prepare for a test at high school or for a personality interview or questionnaire. Your ritual before a sports game. Your ritual before going out with friends – make up codes, choosing your dress or outfit, total party looks. The routines you always follow under certain circumstances on your way to home. Church or other religious rituals you think are important to celebrate. Special meditative techniques you have learned from old masters in East Asia.

These examples are meant to accent the cultural and personal charateristics based on values, beliefs and principles.

What do you think is making life worth living? What shaped your personality? What are the psychological factors and environmental influences?

And state why and how you ground your decisions:

E.g. My act of heroism. The decisions my parents made for me when I was young – school choice, admission and finance. How curiosity brings me where I am now. I daydream of … A place that stands for my romantic moments – a table for two in a restaurant with a great view. My pet resembles my personal habits. A vivid childhood memory in which you can see how I would develop myself in the next ten to fifteen years. Samples of self-reliance in difficult conditions, empathy towards others in society, and your learning attitude and the learning curve.

Make a point by building to a climax at the end of your speech topic, whatever the narrative speech topics may be you want to apply in some sort of public speaking training environment. Build your way to the most intense point in the development or resolution of the subject you have chosen – culminate all facts as narrator to that end point in your verbal account.

Narrative speech tips for organizing and delivering a written description of past events, a story, lesson, moral, personal characteristic or experience you want to share.

- Select carefully the things you want to convey with your audience. Perhaps your public speaking assignment have a time limit. Check that out, and stick to it.This will force you to pick out one single significant story about yourself.And that is easier than you think when you take a closer look at my easy ways to find narrative topics.

- What do you want your audience to remember after the lapse?

- What is the special purpose, the breaking point, the ultimate goal, the smart lesson or the mysterious plot?

- Develop all the action and rising drama you need to visualize the plot of the story: the main events, leading character roles, the most relevant details, and write it in a sequence of steps. Translate those steps into dialogues.

- Organize all the text to speech in a strictly time ordered format. Make a story sequence. Relate a progression of events in a chronologically way.The audience will recognize this simple what I call a What Happened Speech Writing Outline, and can fully understand your goal. Another benefit: you will remember your key ideas better.It can help if you make a simple storyboard – arrange a series of pictures of the action scenes.

- Build in transition sentences, words or phrases, like the words then, after that, next, at this moment, etc. It helps to make a natural flow in your text.

- Rehearse your narrative speech in front of a friend and ask opinions. Practice and practice again. And return to my narrative speech topics gallore if you get lost in your efforts.Avoid to memorize your text to speech. When you are able to tell it in a reasonably extemp manner – everyone can follow you easily – it is okay.

- Finally, try to make eye contact with your listeners when you deliver this educational speech and apply my public speaking tips one by one of course.

- A good place to start finding a suitable narrative speech topic is brainstorming about a memorable moments in your life, a situation you had to cope with in your environment, a difficult setting or funny scene you had to talk your way out.

Try to catch it in one phrase: At X-mas I … and followed by a catchy anf active verb.

E.g. At X-mas I think … I want … I’m going … I was … I stated … I saw … .

After the task verb you can fill in every personal experience you want to share with your public speaking audience in a narration. These 40 speech topics for a storytelling structure can trigger your imagination further.

My most important advice is: stay close to yourself, open all your senses: sight, hearing, taste, and even smell and touch. Good for descibing the memorable moment, the intensity of it.

- A second way to dig up a narrative speech topic is thinking about a leading prophetic or predictive incident in the previous 10 years or in your chidhood. Something that illustrates very well why and how you became who you are right now.

E.g. Your character, moral beliefs, unorthodox manner of behaving or acting or you fight for freedom by not conforming to rules, special skills and qualities.

- The third way I like to communicate here with you is storytelling. Let yourself be triggered for a narrative speech story by incidents or a series of events behind a personal photograph or a video for example.

E.g. Creative writing on a photo of your grand-grandparents, of a pet, a horse, an exciting graduation party, a great architectural design.

- You also can find anecdotal or fictional storylines by highlighting a few of your typical behavior or human characteristics.

E.g. Are you a person that absorbs and acquires information and knowledge, likes to entertain other people or nothing at all? Or are you intellectually very capable in solving comprehensive mathematical calculations? Or are you just enjoying life as it is, and somewhat a live fast die young type?

Or a born organizer – than write speech topics about the last high school or college meeting you controlled and administered.

- The fifth method I would like to discuss is the like or not and why technique. Mark something you absolutely dislike or hate and announce in firm spoken language (still be polite) why. A narrative speech topic based on this procedure are giving insight in the way you look at things and what your references are in life.

It’s a bit like you make a comparison, but the difference is that you strongly defend your personal taste as narrator. It has a solid persuasive taste:

E.g. Speeches about drilling for oil in environmental not secure regions, for or against a Hollywood or Bollywood movie celebrity, our bankingsystem that runs out of trust of you the simple bank account consumer. Or your favorite television sitcom series.

- An exciting, interesting, inspiring or funny experience or event that changed your life is the next public speaking tip I like to reveal now.

E.g.? Staying weekends at your uncle’s farm shaped you as the hardworking person you are nowadays. A narrative speech topic in this category could also be about music lessons, practical jokes. Or troublesome events like divorce, or great adventures like trips at the ocean. Or even finding faith or a wedding happiness.

And what do you think of extreme sports tournaments?

- An important lesson you learned from someone you admire. This is a very classical narrative speech topic.

It tends to be a little bit philosophical, but if you tell you story people will recognize what you mean and compare that with their own stories and wisdom lessons.

Tell the story of a survivor of a traffic accident, and how you admire her or his recovery. Winners of awards, great songwriters, novelists, sportsheroes.

This list is almost exhaustive. Share the wisdom of their fails and achievements.

- The moment in your life you see the light, or that was very insightful. It seems a bit like my number six advice, but focus more on the greatness and happiness of that very moment. A moment’s insight is sometimes worth a life’s experience, American Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes have said.

Magnificent and breath-taking nature phenomenons, precious moments after a day of struggle, final decisions that replenish, lift your spirit.

- A fable or myth that has a moral lesson you try to live to.

Aesop Fables are a great source for a narrative speech topic idea structure. Think about The Dog and His Reflection, The Fox and The Grapes, and Belling the Cat. Talking about fairy tales as an inspiring source: what do you think of a personal story about the moral of The Emperor’s New Clothes?

- The relation between a brief series of important milestones in your life that mold your character is also possible – if catchy narrated storytelling of course :-).

First day of school, first kiss, Prom Night, your high school graduation, wedding, first job interview.

Christening Speeches

Pet Peeve Speech Topics

Leave a Comment

I accept the Privacy Policy

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities

Vivamus integer non suscipit taciti mus etiam at primis tempor sagittis euismod libero facilisi.

© 2024 My Speech Class

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- About me/contact

- examples of narrative speech topics

Examples of narrative speech topics

125 strong ideas for effective personal storytelling speeches

By: Susan Dugdale | Last modified: 12-01-2022

Narrative speech topics are topics especially designed to trigger telling a story.

And who doesn’t love being told a good story? They’re universally appreciated. It’s the oldest, most effective way of emphasizing a point, illustrating an idea or recounting an event.

For as long as there have been people in the world, there have been people telling them stories: story tellers.

What's on this page:

- 125 examples of narrative speech topics: - 40 'first' experiences , - 40 tell-a-story topics , - 35 personal story ideas

- How to best use this page

Choosing the right narrative speech topic

- How to get from topic to speech (with a printable speech outline to download)

A definition of the word 'narrative'

A personal story is a powerful story, the difference between an anecdote and a story.

- Additional resources for storytelling speeches

How to make best use of this page

Browse the topics and make a shortlist of any that appeal to you. (These are the ones that will immediately have you thinking of stories you could share.)

Make sure you download the printable narrative speech outline. Then take what you need from the other information. (If you've never given a narrative or storytelling speech before, read all of it!) It's here to help you put together the best speech you possibly can. ☺

Return to top

The most powerful stories to tell are personal. They’re the game changers, the significant events: meetings, accidents, cultural jolts, and life lessons that have made an impact.

They’re stories about family, our children, love, marriage, politics, education, work, living in society, philosophy, the natural world, ...

In telling these stories we reveal aspects of ourselves: sharing our innermost thoughts and feelings.

To give a good narrative speech, one that fully engages our audience we need to:

- choose a meaningful story with strong characters they can relate to in a situation they’ll recognize and identify with

- use vivid language enabling them to easily picture and feel what’s happening

A spoken or written account of connected events; a story: "a gripping narrative"

Word with similar meanings: account, story, tale, chronicle, history, description, record.

(Definition from Oxford Languages )

Because narrative speeches are often stories about ourselves we need to think carefully about what we share and with whom.

Some subjects are sensitive for many reasons. And what could be completely appropriate in one setting could be quite wrong in another.

As the giver of the speech, you’ll want to be clear about what you’re sharing and why.

Additionally, an emotional narrative speech exposing your own deeply felt and unresolved issues would be difficult for an audience to witness.

They’d want to help, send you to a therapist, leave... People do not want to feel embarrassed or uncomfortable on your behalf.

The right narrative topic idea is one you know your audience will want to hear, fits the speech purpose you’ve been given, and one you feel comfortable sharing.

Should you decide to use someone else's story for your speech be sure to acknowledge whose it is and where you got it from.

Getting from topic to speech

Once you’ve decided on your topic, the next step is developing a story outline. That involves carefully thinking through the sequence of the story, or what you’re going put in it, scene by scene and why, from beginning to end.

To help you do that easily I've put together a printable narrative speech outline. To download it click on the image below. (The pdf will open in a new window.)

The outline will guide you through each of the steps you need to complete. (Instructions are included.)

Rehearsal, rehearsal, rehearsal

Once your outline is done, your next task is rehearsing, and then rehearsing some more. You’ll want to know before you give the speech that it:

- makes sense and can be followed easily,

- grabs and holds the audience’s attention, is relevant to them,

- and easily fits the time you’ve been given.

Rehearsal lets you find out in a safe way where any glitches might be lurking and gives you an opportunity to fix them.

It also gives you time to really work at refining how you tell the story.

For instance, what happens if this part is said softly and slowly? Or if this bit is delivered more quickly, and that has a long pause after it?

And what about your body language? Are you conscious of what you’re actually doing as you speak? Do you ‘show’ with your body and how you use your voice, as well as ‘tell’ with your words?

The way you tell a story makes an enormous difference to how it is received. A good story can be ruined by poor delivery. If you make the time to practice, that’s largely avoidable.

- For more on how to rehearse – a step by step guide to rehearsing well

- For more on the vocal aspects of speech delivery

- For more on developing effective body language

Many people share an anecdote thinking they’re telling a story. They’re not. Although they have similarities, they are different.

An anecdote is a series of facts, a brief account of something that happened. It is delivered without interpretation or reflection. It’s a snapshot cut from a continuum: a slice of life. We’ve taken notice because it was interesting, strange, sad, amusing, attractive, eccentric...to us. It captured our attention in some way.

For example:

"Last night there was a gorgeous girl in the bar wearing a red dress. She ordered a brandy. After she finished her drink, she left."

In contrast, a story develops. It travels from its starting place, goes somewhere else where something happens, and finally arrives at a destination. A story has a beginning, a middle and an end. It moves. Things change.

Here’s the same anecdote example reworked as a very brief story. The person telling it is reminiscing, talking about the past to girl called Amy.

"Last night there was a girl in the bar wearing a red dress—so young, so gorgeous, so full of life. Seeing her whirled me back to us. You and me and that song. Our song: Lady in Red. “The lady in red is dancing with me, cheek to cheek. There's nobody here, it's just you and me. It's where I want to be.”

The complete and abrupt shift from present to past overwhelmed me. Thoughts, feelings, memories... At twenty-five and twenty-six we knew it all and had it all.

When I looked up, she’d finished her drink and gone. Oh, Amy! What did we do?"

Narrative speech topic ideas: 40 firsts

Often the first time we experience something creates deep lasting memories. These can be both very good and very bad which makes them an excellent foundation for a gripping speech.

We love listening to other people’s dramas, especially when they’ve gone through something significant and come out the other side strengthened – armed with new knowledge.

- The first time I stood up for myself.

- The first time I drove a car.

- The first time I rode a bike.

- The first time I fell in love.

- The first time I felt truly frightened.

- The first time I realised my family was different.

- The first time I understood I was different from other kids.

- My first day at a new school.

- The first time I felt truly proud of myself.

- My first date.

- My first job interview.

- The first time I realised no matter how hard I tried I was never going to please, or be liked, by everybody.

- How I got my first paid job.

- What I did with my first pay.

- My first pet.

- My first real fight- what it was about, and what I learned from it.

- The first time I tried hard to achieve something and failed.

- The first time I realised some people are not to be trusted.

- The first time I was away from home on my own.

- The first time I had to ask a stranger for help.

- The first time I experienced what it’s like to have someone close be either seriously ill or die

- The first time I was ill and was taken to hospital.

- The first time I felt utterly filled with happiness.

- The first time I was sincerely impressed and influenced by another person’s goodness.

- My first pin up hero.

- My childhood home – what I remember – the feelings and events I associate with it.

- The first time I realised the color of my skin, or the shape of my body, or my face, or my gender, or anything else about me, made a difference.

- The first time I tried to communicate with someone who did not speak my language.

- The first time I saw snow, the sea, climbed a mountain, camped out under the stars, walked a wilderness trail, caught a wave...

- The first time I visited another country where the language, customs and beliefs were vastly different to my own.

- The first time I understood and experienced the power of kindness.

- The first time I told a lie.

- The first time I understood how fortunate I was to be me.

- The first time I realised my goals and aspirations were attainable.

- The first time I realised having enough money to do whatever I wanted could not buy happiness.

- The first time I realised that some people were always going to be better at some things that I was.

- The first TV show/film/book I loved and why.

- The first time I really understood I was prejudiced.

- The first time someone stepped up for me – what that felt like, and what it changed.

- How first impressions of people and/or an event are not always right.

40 tell-a-story speech topics

Here's another 40 narrative speech suggestions. Give yourself time as go through them to consider suitability of the stories they trigger. Would what you're thinking of suit your audience? Does it fit your overall speech purpose?

- How I learned to stand up for my own beliefs.

- How my name influenced who I am.

- My favorite teacher – why, what did they do? How did that make you feel?

- When and how I learned being adult does not mean being grown up.

- Why winning is important to me.

- What terrified me as a child.

- How I learned to manage my anger.

- What people regularly assume about me and how that makes me feel.

- How having an animal to love made me a better human being.

- How humor defuses tension.

- What it feels like to rebel against authority, and why I do it.

- My learning break through.

- How I discovered what meant the most to me.

- How I learned my family was poor, rich, odd, ...

- When I fully realized the importance and power of community.

- What I learned through living through my parent’s divorce.

- My experience of being an outsider.

- My favorite way to unwind.

- A decision I made that I now regret and why.

- How goal setting has helped me achieve.

- My safe place.

- What being unfairly punished taught me about myself.

- Rituals that serve me well. For example, always cleaning my teeth a particular way, always sorting my clothes out for the following day before I go to bed, always making Christmas presents for my family, ...

- What money means to me and why.

- How being a parent fundamentally changed me,

- What being the underdog taught me.

- Why I chose my own path, and not the one my parents wanted for me,

- Why family celebrations are important to me.

- Why I adopted a child.

- What religion means to me.

- What marriage, friendship,... means to me.

- What needing to be helped has taught me.

- Why and how I support giving back to the community.

- Tricks I use to get myself to do things I know I should do but don’t really want to.

- What I do to manage fear or anxiety of public speaking.

- How I learned to stop biting my finger nails or stop some other behaviour driven by nervous anxiety.

- How I learned to stop feeling like my job in life was to make my parents or anybody else feel happy.

- What having a job as a young person taught me.

- The complications of being the favorite child in your family.

- The difficulties of having to choose between friends.

35 more narrative or personal story speech topics

- The time I made an assumption about a situation or a person and got it entirely wrong.

- What being totally and suddenly out of my depth in a situation felt like and the consequences.

- A lesson I learned the hard way that helped me become a better person. For example: over spending, driving too fast, drinking too much, being caught out in a lie...

- Important things I learned through keeping old people company.

- What I learned through losing a good friend

- What coming face to face with my own mortality taught me.

- How the language of kindness transcends language and cultural differences.

- What being ashamed of my own behaviour taught me.

- How I unknowingly broke local cultural customs while overseas and what happened

- How taking revenge for a wrong did not right it.

- The silliest unnecessary risk I’ve taken.

- How first impressions are not always right.

- How pretending to be strong (fake it until you make it) can work very well.

- What I really wanted my parents to do for me and they didn’t.

- How our clothing influences how other people perceive us.

- My earliest memories: what they were, how they made me feel.

- Why I became disillusioned about politics.

- Why I decided to go into politics.

- The influence of music on my life.

- A personal phobia and how it impacts on my life: fear of spiders, fear of the dark, fear of thunder...

- The impact of peer pressure on decision making.

- What I’ve learned about gratitude.

- How I lied in order to cover for a friend and what happened.

- My most embarrassing moment and how I survived it.

- The worst day of my life: what it taught me.

- How I know peer pressure can make us behave in ways we don’t really want to.

- How I learned to read people.

- Why saying thank you is important.

- Random acts of kindness and generosity.

- Being lost in a strange city.

- What I learned through genuinely apologizing for something I did.

- How the way a person speaks influences what we think about them.

- How a mentor changed my life.

- The most thrilling exciting thing I’ve done.

- How being a leader and being looked up to felt.

Other resources for narrative speeches

Pages on this site:

- 60 vocal variety and body language speech topics - speech ideas to encourage excellent storytelling

- Storytelling setups: what works & why - How to open or lead into a story

- How to effectively use a small story as part of a speech

- Tips and exercises for working with and improving body language

- Simple characterization techniques for compelling storytelling

- 9 aspects of vocal delivery - explanations, tips and exercises to improve your voice

- How to rehearse well - step by step guidance

Offsite storytelling speech resources

- 5 creative storytelling projects recommended by teachers, for everyone | (ted.com)

Toastmasters Project | Connect with storytelling – Level Three

- Connect with Storytelling – District One (district1toastmasters.org)

- 8300-Connect-with-Storytelling.pdf (toastmasters-lightning.org)

speaking out loud

Subscribe for FREE weekly alerts about what's new For more see speaking out loud

Top 10 popular pages

- Welcome speech

- Demonstration speech topics

- Impromptu speech topic cards

- Thank you quotes

- Impromptu public speaking topics

- Farewell speeches

- Phrases for welcome speeches

- Student council speeches

- Free sample eulogies

From fear to fun in 28 ways

A complete one stop resource to scuttle fear in the best of all possible ways - with laughter.

Useful pages

- Search this site

- About me & Contact

- Blogging Aloud

- Free e-course

- Privacy policy

©Copyright 2006-24 www.write-out-loud.com

Designed and built by Clickstream Designs

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

14 Read: Storytelling

Storytelling and public speaking.

Ideas are not really alive if they are confined to one person’s mind.

~Nancy Duarte, Speech coach and author

Learning Outcomes

Students will:.

- Apply storytelling skills to public speaking contexts

- Reflect upon past speaking and listening experiences

- Understand the need to adapt to audiences

- Evaluate nonverbal expressions, especially facial expressions

- Develop asset-based approaches to public speaking perspective

- Practice oral delivery skills and vocal variety for public speaking

This chapter’s Content is fully attributed to Lynn Mead

Introduction, the power of story: the secret ingredient to making any speech memorable.

We love stories because they are engaging, they ignite the imagination, and they have the potential to teach us something. You have likely sat around a campfire or the dinner table telling stories? That is because stories are the primary way we understand the world causing communication scholar and Rhetorical scholar Walter Fisher to call us homo narrans–storytelling humans. Not only is storytelling important in conversation, but it is also important to speechmaking. It is no surprise then, that when researchers looked at 500 TED Talks, they found of the TED talks that go viral, 65% included personal stories.

Professional speakers, college students, politicians, business leaders, and teachers are all beginning to understand the benefits of telling stories in speeches. Increasingly, business leaders are encouraged to move away from the old model of sharing the vision and the mission to a new model of telling the story of the business. Academic literature points out that teachers who use stories can help students understand and recall information. For years, politicians have been coached to include a story in their speeches. They do it because it works, and it is bound in science.

In short, people don’t pay attention to boring things. The story is one way to engage and help ideas come alive. Cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham says, “The human mind seems exquisitely tuned to understand and remember stories—so much that psychologists sometimes refer to stories as ‘psychologically privileged,’ meaning that they are treated differently in memory than other types of material.”

The goal of public speaking is to plant an idea into the minds of your listeners and the most effective way to accomplish that is through a story. I want to share with you three major principles about storytelling and give you concrete ways to incorporate them into your own storytelling.

- Stories, when told properly, will ignite both the reason center and the emotion center of your audience’s brains making them not only more effective in the moment but also more memorable in long run.

- Stories activate the little voices in the audience’s heads and help them think creatively about problems. This activation encourages audiences to act on the idea as opposed to just being passive listeners.

- The best way to tell a story is to connect it to a message, offer concrete details, and follow a predetermined plotline.

(Editorial note: One of the advantages of digital textbooks is I can add videos. In my opinion, the best way to learn about how to write a good story is to see numerous examples of good stories in action. I have provided you with numerous videos illustrating how the story is used in business, used in law, used in entertainment, and used in education so that you can see the many applications. This chapter is different from standard textbooks on the subject because it includes more examples than text. You will only get deep learning if you take the time to watch the video clips.)

Tell me the fact and I’ll learn. Tell me the truth and I’ll believe. But tell me a story and it will live in my heart forever.

–Ancient proverb

Stories Engage the Audience and Make a Point

In under four minutes, Mark Bezos, tells a memorable story. He makes us laugh, allows us to see the situation, and then uses all the emotion and visualization he has created to make a powerful point. A good story draws us in and helps us connect with the person and their idea.

The brain doesn’t pay attention to boring things.

– John Medina, author of Brain Rules

Stories Help Ideas Stick

Stories are sticky. A well-told story “sticks” to our brains and attaches to our emotions. A speaker can tell a story in such a way that the audience “sees” the story in their mind’s eye and “feels” the emotions of the story. In some situations, an audience may become so involved in the story they “react” by making facial expressions or gasping in surprise. By “seeing the story” and physically reacting to the story, the audience is moved from a passive listener to an active participant.

Think about college teachers you have had who told stories as part of their lectures. Did it help you to listen? Did it help you to learn? Chances are it did. Researchers Kromka and Goodby put it to the test on one hundred ninety-four undergraduate students. One group listened to a lecture that included a lesson with a story, while others just heard the lesson’s key points. Students that heard the narrative had more sustained attention to the lecture and they did better on a test of short-term recall. The stories helped them remember the material, but there was an added benefit. The students who heard the narrative liked the teacher more and were more likely to take another course from the instructor in the future.

One of the top TED Talks of all time is My Stroke of Insigh t by Jill Bolte Taylor. In this talk, she weaves a story so engaging that the audience is afraid to blink because they might miss what happens next. Watch as she tells you about the “morning of the stroke.”

On the morning of the stroke, I woke up to a pounding pain behind my left eye. And it was the kind of caustic pain that you get when you bite into ice cream. And it just gripped me — and then it released me. And then it just gripped me — and then it released me. And it was very unusual for me to ever experience any kind of pain, so I thought, “OK, I’ll just start my normal routine.” So I got up and I jumped onto my cardio glider, which is a full-body, full-exercise machine. And I’m jamming away on this thing, and I’m realizing that my hands look like primitive claws grasping onto the bar. And I thought, “That’s very peculiar.” And I looked down at my body and I thought, “Whoa, I’m a weird-looking thing.” And it was as though my consciousness had shifted away from my normal perception of reality, where I’m the person on the machine having the experience, to some esoteric space where I’m witnessing myself having this experience. Jill Bolte Taylor

I’d like to illustrate to you the connection between thinking and doing.

- Imagine you are looking at the Eiffel tower.

- Think of two words that start with “b.”

- Think of two words that start with “p.”

- Imagine that I am cutting a lemon in half and then squeezing the juice in a glass.

- Imagine fingernails running down a chalkboard.

When imagining the Eiffel tower, most people’s eyes scan up.

When thinking of the words that begin with “b” and “p”, most people will mouth the words.

When imagining the lemon, many people will salivate.

When imagining fingernails on a chalkboard, many people will tighten their facial muscles.

We respond physically because a connection exists between our imagination and our physical response. When we say things in our speech that cause a physical response, the audience becomes actively engaged with our talk.

Stories Help the Audience Become Emotionally Engaged

“Emotions are the condiments of speech,” according to speech coach Nancy Duarte. They add spice and flavor to your talk. Emotions such as passion, vulnerability, excitement, and fear are particularly powerful. Researchers at Ohio State have a word for that sense of being carried away into the world of a story. They call it transportation. Their research demonstrated that people can get so immersed in a story they hardly notice the world around them. Audiences can be transported by stories as facts and stories as fiction. Narrative transportation theory proposes that when people lose themselves their intentions and attitudes may change to align with the characters in the story. As speakers, our goal should be to help our audience get lost in the story. Sometimes that means telling our own stories, sometimes it means telling the stories of others, and other times telling a hypothetical story.

You’ve probably heard of an fMRI. It’s the machine that measures blood flow to the brain. Scientists used fMRI machines to measure what happened when someone is telling a story and when someone is listening to that story. What they found is exciting. When they compared the speaker’s brain to the listener’s brains, they noticed the brains were lighting up in the same places. When the speaker described something emotional, the audience was feeling the emotion and the emotional centers of their brains were lighting up. Princeton researcher, Uri Hanson calls this brain synching, “neural coupling.”

Consider a study at Emory University that noticed differences in how brains respond to texture words, “she had a rough day” versus non-texture words “she had a bad day.” The texture words activated sensory parts of the brain. When telling a story, find creative and tactile descriptions to engage your audience.

Texture Words Nontexture words He is a smooth talker He is persuasive The logic was fuzzy The logic was vague She is sharp-witted She is quick-witted She gave a slick performance She gave a stellar performance She is soft-hearted She is kind-hearted

Imagine you pull up to a flashing red stoplight at an intersection. Seeing it in your mind activates the visual part of your brain. Now, imagine a loved one giving you a pat on the back. Once you imagine it, your tactile center will light up. This is quite powerful when you think about it. When you hear a story, you don’t just hear it, but you feel it , visualize it, and simulate it.

Dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins are what David Philips calls the “angel’s cocktail.” He suggests speakers should intentionally create stories to activate each of these hormones. By telling a story in which you build suspense, you increase dopamine which increases focus, memory, and motivation. Telling a story in which the audience can empathize with a character increases oxytocin, the bonding hormone which is known to increase generosity and trust. Finally, making people laugh can activate feel-good endorphins which help people feel more relaxed, more creative, and more focused.

Because of neural coupling (our brain waves synching) and transportation (getting lost in a story), the audience members begin to see the world of the person in the story. Because of hormonal changes, they feel their situation and can empathize. A thoughtfully crafted story has the power to help the audience believe in a cause and care about the outcome.

Time and time, when faced with the task of persuading a group of managers to get enthusiastic about a major change, storytelling was the only thing that worked. Steve Denning, the Leaders Guide to Storytelling

Stories Inspire Action

The conventional view has always been when you speak, you try to get the listeners to pay attention to you. The way you get them to pay attention is to keep the little voice inside their heads quiet. If it stays quiet, then your message will get through. Stephen Denning in The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling suggests an alternative view. He challenges speakers to tell stories to work in harmony with the voices in people’s heads. He says that you don’t want your audience to ignore their voice; you want to tell a story in a way that awakens their little voice to tell its own story. You awaken their voice and then you give it something to do. He advocates using stories as springboards to help the audience think about situations so they can begin to mentally solve problems. In this way, you are not speaking to an audience but rather you are inviting the audience to participate with you.

Consider this story told by Jim Ferrell about the local garbage man and how it engages you and creates both mental images and new ideas.

Stories Help the Ideas Stick in a Way that the Audience Remembers and Understands

Steven Covey, considered one of the twenty-five most influential people by Time Magazine, teaches on business, leadership, and family. In his books and seminars, he uses stories to help the audience remember his lessons. In this video, Green and Clean, he uses a story to help the audience understand servant leadership. As you watch, ask yourself if you will remember this story and the lesson that it offers?

Stories Help Win Law Cases–Example of a Story Analogy

Gerry Spence is considered one of the winningest lawyers and he credits his ability to tell stories to his success. In this video clip, you can see him in action as he tells this jury the story of the old man and the bird. Imagine yourself as a member of the jury, how might this affect you?

“Here’s the story of the bird that some of you wanted to hear again. This is one I’ve used many, many times. It’s a nice method by which you can transfer responsibility for your client to the jury. Ladies and gentlemen, I am about to leave you, but before I leave you I’d like to tell you a story about a wise old man and a smart-alec boy. The smart-alec boy had a plan, he wanted to show up the wise old man, to make a fool of him. The smart-alec boy had caught a bird in the forest. He had him in his hands. The little bird’s tail was sticking out. The bird is alive in his hands. The plan was this: He would go up to the old man and he would say, “Old man, what do I have in my hands?” The old man would say, “You have a bird, my son.” Then the boy would say, “Oldman, is the bird alive or is it dead?” If the old man said that the bird was dead, he would open up his hands and the bird would fly off free, off into the trees, alive, happy. But if the old man said the bird was alive, he would crush it and crush it in his hands and say, “See, old man, the bird is dead.” So, he walked up to the old man and said, “Old man, what do I have in my hands?” The old man said, “You have a bird, my son.” He said, “Old man, is the bird alive or is it dead?” And the old man said, “The bird is in your hands, my son.” Ladies and gentlemen of the jury my client is in yours.” Gerry Spence

Stories Help People Engage With Topics

Alan Alda founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science because he wanted to help scientists learn how to best communicate what they know to a lay audience. In this video clip, he shares his lesson on using stories to draw in an audience.

Example from a Corporate Trainer

The Leader Who Withheld Their Story by Robert “Bob” Kienzle

Our communication training firm was hired to conduct a storytelling workshop for a major client. I quickly realized a major problem: the leader refused to tell a story in the storytelling workshop. We brought the water to the horse and the horse wouldn’t drink. Read the full story of Bob explaining how he taught one of his corporate clients to use storytelling.

Story Changes the Brain Chemistry in Listeners

Paul Zak told audience members a story and then measured the chemicals their bodies released during this story. His conclusion is that story changes brain chemistry and makes individuals more empathetic. In this case, they were more likely to donate money to charity. Watch this video as Zak talks about a universal story structure that includes exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and denouement.

Stories Can Have Drawbacks

While storytelling can be used positively, it can have drawbacks. A story can be more memorable than the point. If the audience remembers your story without the purpose of the story, you missed it. In the teacher’s study mentioned before, students had better short-term recall when the teacher told a narrative. The study also reported that listening to stories increased student cognitive load and some students basically used up their “brainpower” to remembering extraneous information instead of the lesson. The lesson here is to make sure the story reinforces a point and to make sure that the point is clear.

Because stories draw people in emotionally, there can be ethical challenges. Is it ethical to tug at an audience’s heartstrings to get them to donate money? How about giving you money? Speakers need to consider the ethical obligation to consider the impact of the story. Stories tap into emotions and create lasting memories. Stories told with the wrong motives can be manipulative.

The Formula for a Good Story

Tension-release.

So now you see the clear advantage in telling a story, let’s talk about the formula for a good story. A good story should help the audience see the events in their mind’s eye. Your story should play out like a movie in their head. This movie happens because you help them see the setting, characters, and details. To be fully engaged, the audience must feel some sort of tension.

The formula is tension and release.

The best stories create tension or conflict and then in some way resolve conflict. In persuasion, a story can create tension that can be released only by acting on the persuasion. Haven defines a story as “A character-based narration of a character’s struggles to overcome obstacles and reach an important goal.” Notice the focus on struggle and overcoming the struggle. Once you decide on the story that you want to tell, work on helping the audience feel the tension and release.

If the point of life is the same as the point of a story, the point of life is character transformation. If I got any comfort as I set out on my first story, it was that in nearly every story, the protagonist is transformed. He’s a jerk at the beginning and nice at the end, or a coward at the beginning and brave at the end. If the character doesn’t change, the story hasn’t happened yet. And if story is derived from real life, if story is just condensed version of life then life itself may be designed to change us so that we evolve from one kind of person to another. Donald Miller, A Million Miles in a Thousand Years: What I Learned While Editing My Life.

Dale Carnegie’s formula for storytelling includes three parts: Incident, action, and benefit. In the incident phase, the storyteller shares a vivid personal experience relevant to the point. Next, they give the action phrase, and they share the specific action that was taken. Finally, the speaker tells the benefit of taking the action. It still fits the tension-release formula, it just expands it to make sure that the speaker clearly lets the audience know what conclusion they are supposed to draw.

Dave Lieber illustrates this tension and release in his opening story and explains how it works. (You have to watch only the first five minutes to get the point, but I warn you it is hard to stop listening once he has you hooked) According to Dave Lieber, the formula is to meet the character; there is a low part in the story; the hero pushes up against the villain and overcomes.

Good stories represent a change

One part of the tension-release model is how the character changes. Matthew Dick Moth storytelling champion suggests that stories, where no change took place in the storyteller, are just anecdotes, romps, drinking stories, or vacation stories, but they leave no real lasting impression.

The story of how you’re an amazing person who did an amazing thing and ended up in an amazing place is not a story, it is a recipe for a douchebag. The story of how you are a pathetic person who did a pathetic thing and remained pathetic, is also not a story, it is a recipe for a sadsack. You should represent a change in behavior, a change in heart, a change in attitude. It can be a small change or a very large change. A story cannot simply be a series of remarkable events. You must start out as one version of yourself and end as something new. The change can be infinitesimal. It need not reflect an improvement in yourself or your character, but change must happen. Matthew Dick. I once was this, but now I am this I once thought this, but now I think this I once felt this, but now I feel this. I once was hopeful, but now I am not I once was lost, but now I am found I once was happy, but now I am sad I once was sad, but now I am happy I once was uncertain, but now I know I once was angry, but now I am grateful I once was afraid, but now I am fearless I once doubted, but now I believe

Stories Often Follow Common Plots

According to Heath and Heath of Made to Stick , there are common story plots. Each of these can be used in most speech types and can be adapted to the tension-release model.

Challenge Plot

- Underdog story

- Rags-to-riches story

- Willpower over adversity

Challenge plots work because they inspire us to act.

- To take on challenges

- To work harder

Connection Plot

- Focusing on relationships

- Making and developing friendships

- Discovering and growing in love

Connection plots work because they inspire us in social ways.

- To love others

- To help others

- To be more tolerant of others

Creativity Plot

- Making a mental breakthrough

- Solving a longstanding puzzle

- Attacking a problem in an innovative way

Creativity plots work because they inspire us to do something differently.

- To be creative

- To experiment

- To try something new

Elements to a Good Story

For the audience to experience the tension and release, they must be invested in the story. Good stories help the audience see the setting, know the characters, and feel the action.

Think of the setting as a basket to hold your story. If you start with the basket, the audience has a place to hold all the other details you give them. For this reason, many storytellers begin by describing the setting.

2. Characters

When you describe how the characters look or how they felt, we can see them as if we are watching them in a movie. The trick is to tell enough details we can create a mental picture of the character without giving so much information that we get bogged down.

When you describe the action that is taking place, the audience begins to feel the action. If you describe something sad that happened, the audience will feel the sadness. If you describe something exciting that happened to you or a character, the audience will feel that excitement.

Watch the first two minutes of this video and notice how Matthew starts with the setting and the characters and you can see the events unfold. You can see the action take place in your mind’s eye and you become invested in his story.

Flavor Crystals–The Little Extras

As a child, I used to love breath mints that would have blue flecks in them. They were called flavor crystals and they were there as little taste surprises that would enhance the flavor. You can enhance your story with little flavor crystals–little details that make it more interesting. Flavor crystals are those extra details that will impact your audience.

Ruben Gonzalez and Olympic Champion luger is a motivational speaker. As you watch this video clip, notice how he incorporates details in his story so we can see what’s happening.

Make Sure Your Story is Relatable

When you pick your story, make sure that you pick themes others can relate to in some way. Watch World Champion Presiyan Vasilev and notice how he uses little examples that everyone can relate to, like how you always get a flat tire when you are dressed up.

Why do flat tires always happen when you’re dressed up? Is there something collapsed in your life? Your knowledge may be limited. Your skills may be rusty. But no doubt, you will be changed when you reach out.

Lori Halverson-Wente’s Flip Activities for Classroom Use

Students will be assigned homework in their own classes. If you are in Lori Halverson-Wente’s Online Public Speaking course, you will create Flip Discussions similar to the following activities. Please see your course schedule and D2L links for the formal assignments.

FLIP 1 Discussion Activity

Flip 1 – sharing our stories, learning objectives.

This Flip Assignment will address the following learning objectives:

- Practice oral delivery skills and nonverbal expressions in your Flip

- Understand the need to adapt when speaking in public

Preparation

To prepare, complete the following:

- Review the Speech 1 Assignment Sheet .

- Please ask if you have questions.

Post Your Video According to the class schedule

Follow the Directions to open the Flip link for our class and post a 3-minute video discussing the following information:

Answer the following questions. As you do so, remember you are working on your first speech. The questions will help you in your preparation:

- Let us know your name and a way to remember it (what it rhymes with, how to spell it phonetically, etc.) and, if comfortable, share your pronouns (she/her/hers, she/they/them, they/them/theirs, he/his/him, etc.).

- Novelist Chimamanda Adichie shares how she found her authentic cultural voice in this TED talk. How does her statement that there is “more than a single story” relate to you as a speaker preparing messages as well as a listener hearing multiple speeches (stories)? How does her message relate to the need speakers have to “adapt to their audiences?”

- Why look toward our “assets” vs. just our “deficits” when developing skills in public speaking (see chapter reading)? How can we switch the mindset of “struggling” for a topic to “discovering” a topic?” What insight can you take from this video when choosing your own topics?

- Tell us more about yourself and your ideas by responding to at least 1 of the following prompts:

- Please share the basic school information you want to share (major, past schools you’ve gone to, reason in school, career goals, jobs held, etc.).

- What are some of your hobbies and/or interests? What are you passionate about?

- If you could take us anywhere in the world (and money was no object), where would we go and what would we eat? No joke, this is my FAVORITE question.

Flip Replies Due according to the schedule

REPLY to at least 2 classmates in your speech group using the video reply function

In each 1-3 minute video reply, include the following:

- What is a point that you agree with or that you found interesting from a peer?

- Comment upon what information was new to you.

- What is one question you have for your classmate?

- Click here for more Ideas for Replies

Flip 2 Discussion Activity

Flip 2 – discover our assets.

Flip 2 Link

This module will be addressing the following learning objectives:

- Practice oral delivery skills and vocal variety for public speaking.

- Evaluate nonverbal expressions, especially facial expressions.

- Discover your personal assets as a speaker.

- Reflect upon past speaking and listening experiences.

- Apply storytelling skills to public speaking contexts.

- Review the Speech 1 Assignment Sheet . Please ask if you have questions.

Watch the Professional TED talk by Award-winning MN Author Kao Kalia Yang, which is embedded below. Ms. Yang presented this speech in her early career. We will learn more by viewing other videos featuring Ms. Yang over the next two weeks as we prepare for Speech 1.

Tell us your name, pronouns, and speech group.

What about the delivery did you find compelling and effective in the video posted above? What are her assets (strengths) as a speaker and storyteller? Use 4 terms from Chapter 12 as you explain.

What assets do you bring from telling family stories, listening to stories, from books or podcasts, etc.?

How does Ms. Yang pay “tribute” to her family members in the stories she tells?

Finally, discuss your plans for Speech 1 (a Tribute Speech). Consider sharing:

- Who or what has inspired you?

- Who or what motivates you?

- What are your topic ideas for Speech 1?

Flip Replies Due as noted in the schedule

REPLY to at least 2 classmates in your speech group using the video reply function.

- What do you two have in common?

- List three strengths your classmate demonstrated in their Flip Post (e.g., “I thought you had great eye contact as you told us about your grandmother”).

- Give three feedback comments on their ideas for Speech 1.

- What is one question that you have for your classmate?

Flip 3 Discussion Activity

Flip 3 – practice story telling.

Flip 3 Link

This FLIP Assignment will be addressing the following learning objectives:

- Practice oral delivery skills and vocal variety for public speaking,

- Practice nonverbal expressions, especially facial expressions.

- Develop your specific personal assets as a speaker.

- Consider the importance of culture in our messages.

To prepare, complete the following

- Review Assignment 1

- Gather a storybook you would like to read and practice reading it aloud. You might want to read to a pet or a child (you would not video the child for privacy, only your reading).

Watch the Professional Video by Kao Kallia Yang:

Post Flip according to the schedule

Follow the Directions to open the Flip link for our class and post a video discussing this information:

- Tell us your name, pronouns, speech topic, and speech group.

- Comment upon Kao Kalia’s use of nonverbal communication and delivery. Add any reaction you have to her story.

- Now, your turn – READ A STORY!

- Gather a book and tell/read us the story. See the sample we created with our “grand-pup” Pax. You can read to a pet – this is often more fun. You can read to a child (don’t include them physically in the video for safety purposes). You can just read to the camera.

- How are stories like speeches? What skills do we learn when telling or listening to stories?

- When you were younger, what was your favorite book – why?

- When you were younger, did you like reading out loud – why or why not?

- What is your experience hearing stories?

Flip Replies Due as Noted in the Schedule

Reply to at least 2 classmates in your speech group using the video reply function by 11:59 pm next wednesday..

- List three strengths your classmate demonstrated in their Flip Post (e.g., “I thought you used strong vocal variety when you read about the 3 bears.”).

- What do you have in common regarding the video and reading with your classmate?

Flip video Samples

Watch the sample flip assignment created by lori and mark halverson-wente, here mark reads, good night moon.

Here Mark reads, Good Night Loon – Consider how Culture and Stories are Combined

Flip 4 Discussion Activity

Flip 4 – stories and public speaking.

Flip 4 Link

This Flip Assignment will be addressing the following learning objectives:

- Discover how stories and speeches are similar

- Practice creating narratives

- Practice nonverbal communication skills

Video 1: This video was created with Lori, Cindy, and Kao Kalia Yang

Video 2 – How does Cindy include “story” in her speech?

Post Flip as noted in the class schedule

Post a video discussing this information:.

- What is your key takeaway from watching this video?

- What are 2 suggestions that Kao Kalia makes for public speakers that you found helpful?

- How can you use stories in your first speech? Tell us more about your Tribute Speech – what is your topic?

- What are your 3 main points? Share as much as you can.

- If you would like specific feedback, let your classmates know (Remember to reach out directly to Lori if you have specific worries about this assignment).

Video Flip Replies Due as noted in the class schedule

Optional to reply to at least 2 classmates by 11:59 pm, next wednesday..

- What do you have in common with your classmate?

- What feedback do you have for your classmate?

- Add 2 ideas for their speech topic.

Additional Optional Activities for Instructors and Students

Lean Mead suggests the following activities to improve your storytelling skills. Additional activities are suggested and will be assigned by your instructor as noted in your own class.

Do This: Keep a Story Log Notetaking Challenge Matthew Dicks suggests sitting down every day and asking yourself, “What happened today that is storyworthy?” Keep a notebook and write down a few ideas every day. The Magical Science of Storytelling TED Speaker David Philips has a similar suggestion. He encourages people to not only write down your stories but you index them based on the emotional reaction you wanting to get.

Theory Application

Literary theorist Kenneth Burke asks us to think of life as a drama where people are actors on a stage. What is their motivation for what they do and what they say? He offered five strategies for viewing life that he called dramatistic pentad.

- Act: What happened? What is the action? What is going on? What action; what thoughts?

- Scene: Where is the action happening? What is the background situation?

- Agent: Who is involved in the action? What are their roles?

- Agency: How do the agents act? By what means do they act?

- Purpose: Why do the agents act? What do they want?

How does all this relate to telling a story in a speech? The first thing you can do is to use this list when brainstorming how to fully develop your story. You can also use it as a way to evaluate the completeness of your story. The third way to use it is as a tool to evaluate your audience and how they view life. Why do they do what they do and what do they need to hear in order to be inspired, motivated, or persuaded?

In this TED Talk, My Invention that Made Peace with Lions, Richard Turere makes the audience wonder how a problem like lions killing livestock can possibly be solved. Richard draws us into his story and makes us want to know how a young boy could solve such a large problem. Watch this video and see if you can apply each of Burke’s Five Items.

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- A story is a powerful tool because it engages the audience on not just a logical but also an emotional level.

- Good stories offer a setting, a description of the characters, and add enough detail for the audience to see the story take place in their mind’s eye. The action of a story should be told in a way that the audience can see the events unfold in their mind’s eye.

- Good stories have tension and release.

- Good stories have characters and situations that demonstrate a change.

Please share your feedback, suggestions, corrections, and ideas.

I want to hear from you.

Do you have an activity to include? Did you notice a typo that I should correct? Are you planning to use this as a resource and do you want me to know about it? Do you want to tell me something that really helped you?

Click here to share your feedback.

Bonus Features

There is so much information on this topic, that I struggled with what to include and what to leave out or put as optional. Here are a few videos that I like to think of as the BONUS FEATURES. In addition, there is a supplemental chapter on story that includes more videos and activities.

The Magical Science of Storytelling

David Philips uses stories to illustrate how storytelling can activate what he calls the angel’s cocktail: dopamine, oxytocin, and endorphins.

Angel’s Cocktail

- What it does: Increases focus, motivation, memory.

- How to do it: Build suspense, launch a cliffhanger, create a cycle of waiting and expecting.

- What it does: Increases generosity, trust, bonding.

- How to do it: Create empathy for whatever character you build.

- What it does: Increases creativity and focus and people become more relaxed.

- How to do it: Make people laugh.

The Structure of Story

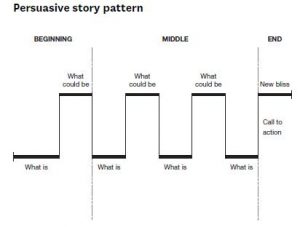

Nancy Duarte studied hundreds of speeches and found the same storytelling technique. In her TED talk, she provides this chart. It is a story that is easy to digest, remember and retell.

Figure 1: Nancy Duarte-Persuasive Story Pattern

INSERT VIDEO: NANCE DUARTE THE SECRET STRUCTURE OF GREAT TALKS

https://www.ted.com/talks/nancy_duarte_the_secret_structure_of_great_talks?language=en

Examples of Storytelling

- Storytelling in a Eulogy: Brook Shield’s Eulogy to Michael Jackson: https://youtu.be/vpjVgF5JDq8

- Storytelling in Business: Steve Denning Discovered the Power of Leadership: https://youtu.be/qiVBcD5M3yc

- Storytelling and Education: Speak Less, Expect More. Matthew Dicks: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sK2P2NEIXUE

chapter Attribution – Lynn Mead

*Thank you to Lynn Mead for your hard work in this chapter material.

Advanced Public Speaking by Lynn Meade is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

*From the attributed author

Alda, A. (2017). If I understood you, would I have this look on my face? Random House.

Alda, A. (2017). Knowing how to tell a good story is like having mind control. Big Think. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4k6Gm4tlXw Standard YouTube License.

Bezos, M. (2011). A life lesson from a volunteer firefighter. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/mark_bezos_a_life_lesson_from_a_volunteer_firefighter?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare Standard YouTube License.

Bolte-Taylor, J.92008). My Stroke of Insight. Ted Talk. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/jill_bolte_taylor_my_stroke_of_insight?language=en Standard YouTube License.

Braddock, K., Dillard, J. P. (25 February 2016). Meta-analytic evidence for the persuasive effect of narratives on beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. Communication Monographs, 83 (4), 446–467. doi:10.1080/03637751.2015.1128555. S2CID 146978687.

Brooks, D. (2019). The lies our culture tells us about what matters–and a better way to live. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.ted.com/talks/david_brooks_the_lies_our_culture_tells_us_about_what_matters_and_a_better_way_to_live?language=en Standard Youtube License.

Burke, K. (1945). A grammar of motive s. Berkeley: U of California Press.

Carnegie, D. (2017). The art of storytelling. Dale Carnegie & Associates ebook.

Covey, S. (2017). Green and Clean. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8MylQ_VPUI Standard YouTube License.

Dahlstrom, M,F. (2014). Using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with nonexpert audiences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(4), 13614–13620. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1320645111

Denning, S. (2005). The leader’s guide to storytelling: Mastering the art and discipline of business narrative. John Wiley and Son.

Denning, S. (2001). The springboard: How storytelling ignites action in knowledge-era organizations. Taylor & Francis.

Dicks, M. (2018). Storyworthy: Engage, teach, persuade, and change your life through the power of storytelling. New World.

Dicks, M. (2016). This is Gonna Suck. Moth Mainstage. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3J4Q5c1C1w Standard YouTube License.

Duarte, N. (n.d.) Fifteen Science-Based Public Speaking Tips to be a Master Speaker, The Science of People. https://www.scienceofpeople.com/public-speaking-tips/ .

Ferrell, J. (2017). An outward mindset for an inward world. Jim Ferrell Keynote. The Arbinger Institute. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_phMQY_3S8 Standard YouTube License.

Fisher, W.R. (2009). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monograph s, 51 (1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390180

Fisher, W.R. (1985). The Narrative Paradigm: In the Beginning, Journal of Communication , 35(4), 74-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1985.tb02974.x

Gallo, C. (2016). I’ve analyzed 500 TED Talks, and this is the one rule you should follow when you give a presentation. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/ted-talk-rules-for-presentations-2016-3

Gershon, N, & Page, W. (2001). What storytelling can do for information visualization. Communication of the ACM, 44, 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1145/381641.381653

Gonzales, R. (2011). Three-time Olympian, peak performance expert. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqMOrjsRUT4. Standard YouTube License.

Green, M. C., & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of personality and social psychology , 79 (5), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701

Green, S. J., Grorud-Colvert, K. & Mannix, H. (2018). Uniting science and stories: Perspectives on the value of storytelling for communicating science. Facets, 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2016-0079

Hasson, U., Ghazanfar, A.A., Galantucci, B., Garrod S, & Keysers C. (2012). Brain-to-brain coupling: a mechanism for creating and sharing a social world. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16 (2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.007

Haven, K. (2007). Story proof: The science behind the startling power of story. Kendall Haven.

Heath, C & Heath, D. (2008). Made to Stick. Random House.

Homo Narrans: Story-Telling in Mass Culture and Everyday Life. (1985). Journal of Communication , 35 (3) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1985.tb02973.x

Kromka, S. M. & Goodboy, A. K. (2019) Classroom storytelling: Using instructor narratives to increase student recall, affect, and attention, Communication Education, 68:1, 20-43. DOI: 10.1080/03634523.2018.1529330

Lacey, S., Stilla, R., & Sathian, K. (2012). Metaphorically feeling: comprehending textural metaphors activates somatosensory cortex. Brain and language , 120 (3), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2011.12.016

Lieber, D. (2013). The power of storytelling to change the world. TEDtalk. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Bo3dpVb5jw Standard YouTube License.

Miller, D. (1994). A million miles in a thousand years: How I learned to live a better story. Thomas Nelson.

Philips, D. (2017). The magical science of storytelling. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nj-hdQMa3uA Standard YouTube License.

Reynolds, G. (2014). Why storytelling matters TED. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YbV3b-l1sZs Standard YouTube License.

Simmons, A. (2001). The story factor: Inspiration, influence, and persuasion through the art of storytelling. Basic Books.

Spencer, G. (1995). How to argue and win every time . St. Martin.

Spence, G. (2018). Persuasive storytelling for lawyers by Alan Howard. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzdoR2PJqYg Standard YouTube License

Turere, T. (2013). My invention that made peace with lions. TED. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RAoo–SeUIk Standard YouTube License.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why Don’t Students Like School?: A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom . Jossey-Bass.

Zac, P.J. (2014). Why your brain loves good storytelling. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/10/why-your-brain-loves-good-storytelling

Zac, P.J. (2012). Empathy, neurochemistry, and the dramatic arc: Paul Zac and the future of storytelling. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1a7tiA1Qzo Standard YouTube License.

Media Attributions

- Sitting around a campfire © Ball Park Brand is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Voices in your head is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Formula for a story © Lynn Meade is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Persuasive Story Pattern

SHARE THIS BOOK

The Public Speaking Resource Project Copyright © 2018 by Lori Halverson-Wente and Mark Halverson-Wente is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Storytelling is a powerful communication tool — here’s how to use it, from TED

Share this idea.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Many of the best TED Talks are built around stories, with speakers’ personal anecdotes helping them bring their ideas to life. Here, TED head curator Chris Anderson provides us with some storytelling dos and don’ts. Plus: news about the TED Masterclass app.

After watching a great talk on TED.com , many of us have wondered: “Could I do it myself? Could I give a TED Talk?”

Now’s your chance to find out.

The new TED Masterclass app — available from the Google Play store and the Apple App store — is designed to help you develop and share your best ideas as a TED-style talk. Guided by TED head curator Chris Anderson and based on his book TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking , the app-based course features 11 animated lessons that break down the public-speaking techniques that TED speakers use to present their ideas. Developed by TED-Ed , the course also features a library of full-length TED Talks from Brené Brown, Bryan Stevenson, Susan Cain and others to reinforce its lessons.

In this post, which is adapted from the TED Masterclass app and his book, Anderson discusses how we can learn to use storytelling to elevate our speeches, presentations and talks.

The best evidence from archaeology and anthropology suggests the human mind evolved with storytelling. About a million years ago our hominid ancestors began gaining control of the use of fire, and it seems to have had a profound impact on their development. It provided warmth, defense against predators, and the ability to cook food (along with its remarkable consequences for the growth of our brains.

But it brought humans something else. Fire created a new magnet for social bonding and drew people together after dark. In many cultures, one form of fireside interaction became prevalent: Storytelling.

It’s no surprise that many of the best TED Talks are anchored in storytelling. But when it comes to sharing a story as part of a presentation or speech, there are four key things for you to remember.

- Base it on a character your audience can empathize with or ar0und a dilemma your audience can relate to.

- Build tension whether through curiosity, intrigue or actual danger.

- Offer the right level of detail. Too little and the story is not vivid; too much and it gets bogged down.

- End with a satisfying resolution, whether it’s funny, moving or revealing.