Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

Published on 15 September 2022 by Tegan George .

Recommendations in research are a crucial component of your discussion section and the conclusion of your thesis , dissertation , or research paper .

As you conduct your research and analyse the data you collected , perhaps there are ideas or results that don’t quite fit the scope of your research topic . Or, maybe your results suggest that there are further implications of your results or the causal relationships between previously-studied variables than covered in extant research.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

What should recommendations look like, building your research recommendation, how should your recommendations be written, recommendation in research example, frequently asked questions about recommendations.

Recommendations for future research should be:

- Concrete and specific

- Supported with a clear rationale

- Directly connected to your research

Overall, strive to highlight ways other researchers can reproduce or replicate your results to draw further conclusions, and suggest different directions that future research can take, if applicable.

Relatedly, when making these recommendations, avoid:

- Undermining your own work, but rather offer suggestions on how future studies can build upon it

- Suggesting recommendations actually needed to complete your argument, but rather ensure that your research stands alone on its own merits

- Using recommendations as a place for self-criticism, but rather as a natural extension point for your work

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

There are many different ways to frame recommendations, but the easiest is perhaps to follow the formula of research question conclusion recommendation. Here’s an example.

Conclusion An important condition for controlling many social skills is mastering language. If children have a better command of language, they can express themselves better and are better able to understand their peers. Opportunities to practice social skills are thus dependent on the development of language skills.

As a rule of thumb, try to limit yourself to only the most relevant future recommendations: ones that stem directly from your work. While you can have multiple recommendations for each research conclusion, it is also acceptable to have one recommendation that is connected to more than one conclusion.

These recommendations should be targeted at your audience, specifically toward peers or colleagues in your field that work on similar topics to yours. They can flow directly from any limitations you found while conducting your work, offering concrete and actionable possibilities for how future research can build on anything that your own work was unable to address at the time of your writing.

See below for a full research recommendation example that you can use as a template to write your own.

The current study can be interpreted as a first step in the research on COPD speech characteristics. However, the results of this study should be treated with caution due to the small sample size and the lack of details regarding the participants’ characteristics.

Future research could further examine the differences in speech characteristics between exacerbated COPD patients, stable COPD patients, and healthy controls. It could also contribute to a deeper understanding of the acoustic measurements suitable for e-health measurements.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

While it may be tempting to present new arguments or evidence in your thesis or disseration conclusion , especially if you have a particularly striking argument you’d like to finish your analysis with, you shouldn’t. Theses and dissertations follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the discussion section and results section .) The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation should include the following:

- A restatement of your research question

- A summary of your key arguments and/or results

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

For a stronger dissertation conclusion , avoid including:

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 15). How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved 12 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/research-recommendations/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion, how to write a results section | tips & examples.

How to write recommendations for the study in a thesis report?

Typically noted as ‘Conclusion and Recommendations for the study’ in thesis reports, the section dedicated to recommendations for the study is brief and direct. In many thesis reports it is also presented as a standalone section. Recommendations for the study do not explain anything as other sections of the research would do. Instead, the focus here is on highlighting what more can be done in that field of study. It also gives direction to fellow researchers to dive into the discussion in the future.

The main themes of this section are:

- Improvement

- Development

The recommendations for the study section present possible areas of improvement for future studies.

Constituents of the recommendations for the study section

Since this section of the thesis report is most often set along with the conclusion of the study, it is better presented in a brief but direct approach. It is introduced by one direct sentence that separates it from the conclusion of the study. The preceding statements should immediately note the recommendations and why these suggestions are important. It should then explain how such suggestions can be achieved in a future research. While writing the recommendations for the study section, it is important that the suggestions are:

- Measurable,

- Attainable,

- Realistic, and

This section can also be presented in bullet points and focus to cover:

While there is no required specific number of recommendations but 4 recommendations for every 20000 words in a thesis report is a general thumb. Limit the number of words in this section up to 5% of the total word count of your thesis report. This is to set a balance as to what else can be done and the current investigation.

What not to do?

Remember that the recommendations for the study section should not be confused with the conclusion or the summary of the study. It should only focus on the suggestions for future possibilities. Do not present new findings or statistical or experimental data. Do not include theoretical concepts. Start with an introductory statement.

This section enlists the recommendations of the study. The purpose is to offer ideas on how the findings of this study can be implemented in academia to further this field of study. It also offers suggestions on how the challenges of the industry or individuals can be addressed for better outcomes.

Thereafter, split the section into three sub-sections as explained above. After writing the recommendations for each sub-section, close the thesis with ‘ Scope for further research ‘.

It is suggested that direct interviews with individuals who have been diagnosed with PNES be pursued in the future to allow the researchers to closely look into the situation more closely. After accomplishing the interview, a few context suggestions on how to improve the lives of the said individuals ought to be given particular attention.

The above recommendation focuses on improving the idea behind exploring the issue of how Psychological Non-Epileptic Seizures affect the functionality of a person suffering from the condition. This recommendation is for a 1000-word research paper on PNES or Psychological Non-Epileptic Seizures. There is only one specific recommendation which is explained in a few statements- which remains true to the idea behind keeping the recommendations section brief and focused.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

research analysis

Proofreading.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion

Published on September 6, 2022 by Tegan George and Shona McCombes. Revised on November 20, 2023.

The conclusion is the very last part of your thesis or dissertation . It should be concise and engaging, leaving your reader with a clear understanding of your main findings, as well as the answer to your research question .

In it, you should:

- Clearly state the answer to your main research question

- Summarize and reflect on your research process

- Make recommendations for future work on your thesis or dissertation topic

- Show what new knowledge you have contributed to your field

- Wrap up your thesis or dissertation

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Discussion vs. conclusion, how long should your conclusion be, step 1: answer your research question, step 2: summarize and reflect on your research, step 3: make future recommendations, step 4: emphasize your contributions to your field, step 5: wrap up your thesis or dissertation, full conclusion example, conclusion checklist, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about conclusion sections.

While your conclusion contains similar elements to your discussion section , they are not the same thing.

Your conclusion should be shorter and more general than your discussion. Instead of repeating literature from your literature review , discussing specific research results , or interpreting your data in detail, concentrate on making broad statements that sum up the most important insights of your research.

As a rule of thumb, your conclusion should not introduce new data, interpretations, or arguments.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Depending on whether you are writing a thesis or dissertation, your length will vary. Generally, a conclusion should make up around 5–7% of your overall word count.

An empirical scientific study will often have a short conclusion, concisely stating the main findings and recommendations for future research. A humanities dissertation topic or systematic review , on the other hand, might require more space to conclude its analysis, tying all the previous sections together in an overall argument.

Your conclusion should begin with the main question that your thesis or dissertation aimed to address. This is your final chance to show that you’ve done what you set out to do, so make sure to formulate a clear, concise answer.

- Don’t repeat a list of all the results that you already discussed

- Do synthesize them into a final takeaway that the reader will remember.

An empirical thesis or dissertation conclusion may begin like this:

A case study –based thesis or dissertation conclusion may begin like this:

In the second example, the research aim is not directly restated, but rather added implicitly to the statement. To avoid repeating yourself, it is helpful to reformulate your aims and questions into an overall statement of what you did and how you did it.

Your conclusion is an opportunity to remind your reader why you took the approach you did, what you expected to find, and how well the results matched your expectations.

To avoid repetition , consider writing more reflectively here, rather than just writing a summary of each preceding section. Consider mentioning the effectiveness of your methodology , or perhaps any new questions or unexpected insights that arose in the process.

You can also mention any limitations of your research, but only if you haven’t already included these in the discussion. Don’t dwell on them at length, though—focus on the positives of your work.

- While x limits the generalizability of the results, this approach provides new insight into y .

- This research clearly illustrates x , but it also raises the question of y .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You may already have made a few recommendations for future research in your discussion section, but the conclusion is a good place to elaborate and look ahead, considering the implications of your findings in both theoretical and practical terms.

- Based on these conclusions, practitioners should consider …

- To better understand the implications of these results, future studies could address …

- Further research is needed to determine the causes of/effects of/relationship between …

When making recommendations for further research, be sure not to undermine your own work. Relatedly, while future studies might confirm, build on, or enrich your conclusions, they shouldn’t be required for your argument to feel complete. Your work should stand alone on its own merits.

Just as you should avoid too much self-criticism, you should also avoid exaggerating the applicability of your research. If you’re making recommendations for policy, business, or other practical implementations, it’s generally best to frame them as “shoulds” rather than “musts.” All in all, the purpose of academic research is to inform, explain, and explore—not to demand.

Make sure your reader is left with a strong impression of what your research has contributed to the state of your field.

Some strategies to achieve this include:

- Returning to your problem statement to explain how your research helps solve the problem

- Referring back to the literature review and showing how you have addressed a gap in knowledge

- Discussing how your findings confirm or challenge an existing theory or assumption

Again, avoid simply repeating what you’ve already covered in the discussion in your conclusion. Instead, pick out the most important points and sum them up succinctly, situating your project in a broader context.

The end is near! Once you’ve finished writing your conclusion, it’s time to wrap up your thesis or dissertation with a few final steps:

- It’s a good idea to write your abstract next, while the research is still fresh in your mind.

- Next, make sure your reference list is complete and correctly formatted. To speed up the process, you can use our free APA citation generator .

- Once you’ve added any appendices , you can create a table of contents and title page .

- Finally, read through the whole document again to make sure your thesis is clearly written and free from language errors. You can proofread it yourself , ask a friend, or consider Scribbr’s proofreading and editing service .

Here is an example of how you can write your conclusion section. Notice how it includes everything mentioned above:

V. Conclusion

The current research aimed to identify acoustic speech characteristics which mark the beginning of an exacerbation in COPD patients.

The central questions for this research were as follows: 1. Which acoustic measures extracted from read speech differ between COPD speakers in stable condition and healthy speakers? 2. In what ways does the speech of COPD patients during an exacerbation differ from speech of COPD patients during stable periods?

All recordings were aligned using a script. Subsequently, they were manually annotated to indicate respiratory actions such as inhaling and exhaling. The recordings of 9 stable COPD patients reading aloud were then compared with the recordings of 5 healthy control subjects reading aloud. The results showed a significant effect of condition on the number of in- and exhalations per syllable, the number of non-linguistic in- and exhalations per syllable, and the ratio of voiced and silence intervals. The number of in- and exhalations per syllable and the number of non-linguistic in- and exhalations per syllable were higher for COPD patients than for healthy controls, which confirmed both hypotheses.

However, the higher ratio of voiced and silence intervals for COPD patients compared to healthy controls was not in line with the hypotheses. This unpredicted result might have been caused by the different reading materials or recording procedures for both groups, or by a difference in reading skills. Moreover, there was a trend regarding the effect of condition on the number of syllables per breath group. The number of syllables per breath group was higher for healthy controls than for COPD patients, which was in line with the hypothesis. There was no effect of condition on pitch, intensity, center of gravity, pitch variability, speaking rate, or articulation rate.

This research has shown that the speech of COPD patients in exacerbation differs from the speech of COPD patients in stable condition. This might have potential for the detection of exacerbations. However, sustained vowels rarely occur in spontaneous speech. Therefore, the last two outcome measures might have greater potential for the detection of beginning exacerbations, but further research on the different outcome measures and their potential for the detection of exacerbations is needed due to the limitations of the current study.

Checklist: Conclusion

I have clearly and concisely answered the main research question .

I have summarized my overall argument or key takeaways.

I have mentioned any important limitations of the research.

I have given relevant recommendations .

I have clearly explained what my research has contributed to my field.

I have not introduced any new data or arguments.

You've written a great conclusion! Use the other checklists to further improve your dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

While it may be tempting to present new arguments or evidence in your thesis or disseration conclusion , especially if you have a particularly striking argument you’d like to finish your analysis with, you shouldn’t. Theses and dissertations follow a more formal structure than this.

All your findings and arguments should be presented in the body of the text (more specifically in the discussion section and results section .) The conclusion is meant to summarize and reflect on the evidence and arguments you have already presented, not introduce new ones.

For a stronger dissertation conclusion , avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the discussion section and results section

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion …”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g., “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation shouldn’t take up more than 5–7% of your overall word count.

The conclusion of your thesis or dissertation should include the following:

- A restatement of your research question

- A summary of your key arguments and/or results

- A short discussion of the implications of your research

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. & McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Conclusion. Scribbr. Retrieved March 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/write-conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, how to write a discussion section | tips & examples, how to write an abstract | steps & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, what is your plagiarism score.

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of exploration. In an era marked by rapid technological advancements and an ever-expanding knowledge base, refining the process of generating research recommendations becomes imperative.

But, what is a research recommendation?

Research recommendations are suggestions or advice provided to researchers to guide their study on a specific topic . They are typically given by experts in the field. Research recommendations are more action-oriented and provide specific guidance for decision-makers, unlike implications that are broader and focus on the broader significance and consequences of the research findings. However, both are crucial components of a research study.

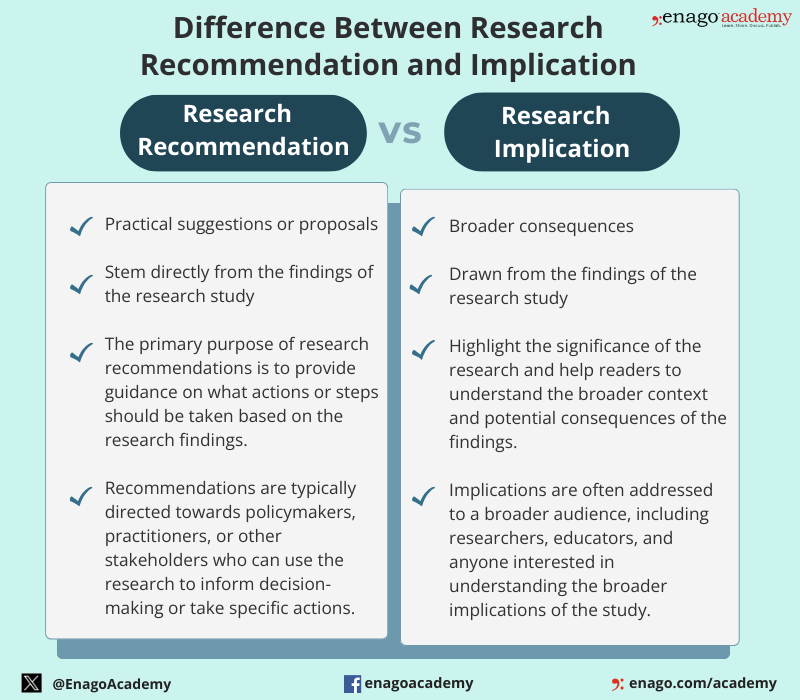

Difference Between Research Recommendations and Implication

Although research recommendations and implications are distinct components of a research study, they are closely related. The differences between them are as follows:

Types of Research Recommendations

Recommendations in research can take various forms, which are as follows:

These recommendations aim to assist researchers in navigating the vast landscape of academic knowledge.

Let us dive deeper to know about its key components and the steps to write an impactful research recommendation.

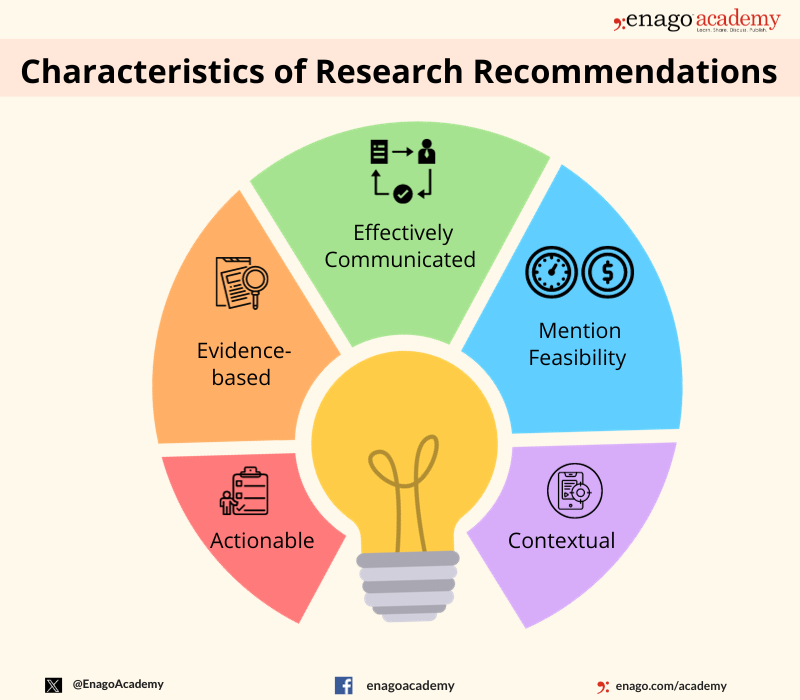

Key Components of Research Recommendations

The key components of research recommendations include defining the research question or objective, specifying research methods, outlining data collection and analysis processes, presenting results and conclusions, addressing limitations, and suggesting areas for future research. Here are some characteristics of research recommendations:

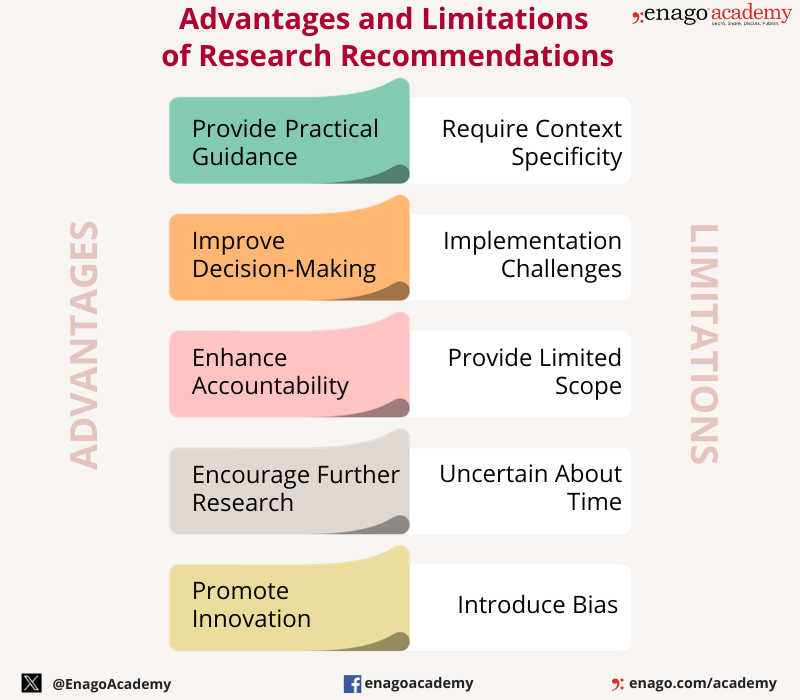

Research recommendations offer various advantages and play a crucial role in ensuring that research findings contribute to positive outcomes in various fields. However, they also have few limitations which highlights the significance of a well-crafted research recommendation in offering the promised advantages.

The importance of research recommendations ranges in various fields, influencing policy-making, program development, product development, marketing strategies, medical practice, and scientific research. Their purpose is to transfer knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, or stakeholders, facilitating informed decision-making and improving outcomes in different domains.

How to Write Research Recommendations?

Research recommendations can be generated through various means, including algorithmic approaches, expert opinions, or collaborative filtering techniques. Here is a step-wise guide to build your understanding on the development of research recommendations.

1. Understand the Research Question:

Understand the research question and objectives before writing recommendations. Also, ensure that your recommendations are relevant and directly address the goals of the study.

2. Review Existing Literature:

Familiarize yourself with relevant existing literature to help you identify gaps , and offer informed recommendations that contribute to the existing body of research.

3. Consider Research Methods:

Evaluate the appropriateness of different research methods in addressing the research question. Also, consider the nature of the data, the study design, and the specific objectives.

4. Identify Data Collection Techniques:

Gather dataset from diverse authentic sources. Include information such as keywords, abstracts, authors, publication dates, and citation metrics to provide a rich foundation for analysis.

5. Propose Data Analysis Methods:

Suggest appropriate data analysis methods based on the type of data collected. Consider whether statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a mixed-methods approach is most suitable.

6. Consider Limitations and Ethical Considerations:

Acknowledge any limitations and potential ethical considerations of the study. Furthermore, address these limitations or mitigate ethical concerns to ensure responsible research.

7. Justify Recommendations:

Explain how your recommendation contributes to addressing the research question or objective. Provide a strong rationale to help researchers understand the importance of following your suggestions.

8. Summarize Recommendations:

Provide a concise summary at the end of the report to emphasize how following these recommendations will contribute to the overall success of the research project.

By following these steps, you can create research recommendations that are actionable and contribute meaningfully to the success of the research project.

Download now to unlock some tips to improve your journey of writing research recommendations.

Example of a Research Recommendation

Here is an example of a research recommendation based on a hypothetical research to improve your understanding.

Research Recommendation: Enhancing Student Learning through Integrated Learning Platforms

Background:

The research study investigated the impact of an integrated learning platform on student learning outcomes in high school mathematics classes. The findings revealed a statistically significant improvement in student performance and engagement when compared to traditional teaching methods.

Recommendation:

In light of the research findings, it is recommended that educational institutions consider adopting and integrating the identified learning platform into their mathematics curriculum. The following specific recommendations are provided:

- Implementation of the Integrated Learning Platform:

Schools are encouraged to adopt the integrated learning platform in mathematics classrooms, ensuring proper training for teachers on its effective utilization.

- Professional Development for Educators:

Develop and implement professional programs to train educators in the effective use of the integrated learning platform to address any challenges teachers may face during the transition.

- Monitoring and Evaluation:

Establish a monitoring and evaluation system to track the impact of the integrated learning platform on student performance over time.

- Resource Allocation:

Allocate sufficient resources, both financial and technical, to support the widespread implementation of the integrated learning platform.

By implementing these recommendations, educational institutions can harness the potential of the integrated learning platform and enhance student learning experiences and academic achievements in mathematics.

This example covers the components of a research recommendation, providing specific actions based on the research findings, identifying the target audience, and outlining practical steps for implementation.

Using AI in Research Recommendation Writing

Enhancing research recommendations is an ongoing endeavor that requires the integration of cutting-edge technologies, collaborative efforts, and ethical considerations. By embracing data-driven approaches and leveraging advanced technologies, the research community can create more effective and personalized recommendation systems. However, it is accompanied by several limitations. Therefore, it is essential to approach the use of AI in research with a critical mindset, and complement its capabilities with human expertise and judgment.

Here are some limitations of integrating AI in writing research recommendation and some ways on how to counter them.

1. Data Bias

AI systems rely heavily on data for training. If the training data is biased or incomplete, the AI model may produce biased results or recommendations.

How to tackle: Audit regularly the model’s performance to identify any discrepancies and adjust the training data and algorithms accordingly.

2. Lack of Understanding of Context:

AI models may struggle to understand the nuanced context of a particular research problem. They may misinterpret information, leading to inaccurate recommendations.

How to tackle: Use AI to characterize research articles and topics. Employ them to extract features like keywords, authorship patterns and content-based details.

3. Ethical Considerations:

AI models might stereotype certain concepts or generate recommendations that could have negative consequences for certain individuals or groups.

How to tackle: Incorporate user feedback mechanisms to reduce redundancies. Establish an ethics review process for AI models in research recommendation writing.

4. Lack of Creativity and Intuition:

AI may struggle with tasks that require a deep understanding of the underlying principles or the ability to think outside the box.

How to tackle: Hybrid approaches can be employed by integrating AI in data analysis and identifying patterns for accelerating the data interpretation process.

5. Interpretability:

Many AI models, especially complex deep learning models, lack transparency on how the model arrived at a particular recommendation.

How to tackle: Implement models like decision trees or linear models. Provide clear explanation of the model architecture, training process, and decision-making criteria.

6. Dynamic Nature of Research:

Research fields are dynamic, and new information is constantly emerging. AI models may struggle to keep up with the rapidly changing landscape and may not be able to adapt to new developments.

How to tackle: Establish a feedback loop for continuous improvement. Regularly update the recommendation system based on user feedback and emerging research trends.

The integration of AI in research recommendation writing holds great promise for advancing knowledge and streamlining the research process. However, navigating these concerns is pivotal in ensuring the responsible deployment of these technologies. Researchers need to understand the use of responsible use of AI in research and must be aware of the ethical considerations.

Exploring research recommendations plays a critical role in shaping the trajectory of scientific inquiry. It serves as a compass, guiding researchers toward more robust methodologies, collaborative endeavors, and innovative approaches. Embracing these suggestions not only enhances the quality of individual studies but also contributes to the collective advancement of human understanding.

Frequently Asked Questions

The purpose of recommendations in research is to provide practical and actionable suggestions based on the study's findings, guiding future actions, policies, or interventions in a specific field or context. Recommendations bridges the gap between research outcomes and their real-world application.

To make a research recommendation, analyze your findings, identify key insights, and propose specific, evidence-based actions. Include the relevance of the recommendations to the study's objectives and provide practical steps for implementation.

Begin a recommendation by succinctly summarizing the key findings of the research. Clearly state the purpose of the recommendation and its intended impact. Use a direct and actionable language to convey the suggested course of action.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Industry News

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Reporting Research

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS style

In today’s digital age, the internet serves as an invaluable resource for researchers across all…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Science under Surveillance: Journals adopt advanced AI to uncover image manipulation

Journals are increasingly turning to cutting-edge AI tools to uncover deceitful images published in manuscripts.…

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Beyond the Podium: Understanding the differences in conference and academic…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

When should AI tools be used in university labs?

How To Write The Conclusion Chapter

The what, why & how explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD Cand). Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | September 2021

So, you’ve wrapped up your results and discussion chapters, and you’re finally on the home stretch – the conclusion chapter . In this post, we’ll discuss everything you need to know to craft a high-quality conclusion chapter for your dissertation or thesis project.

Overview: Dissertation Conclusion Chapter

- What the thesis/dissertation conclusion chapter is

- What to include in your conclusion chapter

- How to structure and write up your conclusion chapter

- A few tips to help you ace the chapter

What exactly is the conclusion chapter?

The conclusion chapter is typically the final major chapter of a dissertation or thesis. As such, it serves as a concluding summary of your research findings and wraps up the document. While some publications such as journal articles and research reports combine the discussion and conclusion sections, these are typically separate chapters in a dissertation or thesis. As always, be sure to check what your university’s structural preference is before you start writing up these chapters.

So, what’s the difference between the discussion and the conclusion chapter?

Well, the two chapters are quite similar , as they both discuss the key findings of the study. However, the conclusion chapter is typically more general and high-level in nature. In your discussion chapter, you’ll typically discuss the intricate details of your study, but in your conclusion chapter, you’ll take a broader perspective, reporting on the main research outcomes and how these addressed your research aim (or aims) .

A core function of the conclusion chapter is to synthesise all major points covered in your study and to tell the reader what they should take away from your work. Basically, you need to tell them what you found , why it’s valuable , how it can be applied , and what further research can be done.

Whatever you do, don’t just copy and paste what you’ve written in your discussion chapter! The conclusion chapter should not be a simple rehash of the discussion chapter. While the two chapters are similar, they have distinctly different functions.

What should I include in the conclusion chapter?

To understand what needs to go into your conclusion chapter, it’s useful to understand what the chapter needs to achieve. In general, a good dissertation conclusion chapter should achieve the following:

- Summarise the key findings of the study

- Explicitly answer the research question(s) and address the research aims

- Inform the reader of the study’s main contributions

- Discuss any limitations or weaknesses of the study

- Present recommendations for future research

Therefore, your conclusion chapter needs to cover these core components. Importantly, you need to be careful not to include any new findings or data points. Your conclusion chapter should be based purely on data and analysis findings that you’ve already presented in the earlier chapters. If there’s a new point you want to introduce, you’ll need to go back to your results and discussion chapters to weave the foundation in there.

In many cases, readers will jump from the introduction chapter directly to the conclusions chapter to get a quick overview of the study’s purpose and key findings. Therefore, when you write up your conclusion chapter, it’s useful to assume that the reader hasn’t consumed the inner chapters of your dissertation or thesis. In other words, craft your conclusion chapter such that there’s a strong connection and smooth flow between the introduction and conclusion chapters, even though they’re on opposite ends of your document.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the conclusion chapter

Now that you have a clearer view of what the conclusion chapter is about, let’s break down the structure of this chapter so that you can get writing. Keep in mind that this is merely a typical structure – it’s not set in stone or universal. Some universities will prefer that you cover some of these points in the discussion chapter , or that you cover the points at different levels in different chapters.

Step 1: Craft a brief introduction section

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, the conclusions chapter needs to start with a brief introduction. In this introductory section, you’ll want to tell the reader what they can expect to find in the chapter, and in what order . Here’s an example of what this might look like:

This chapter will conclude the study by summarising the key research findings in relation to the research aims and questions and discussing the value and contribution thereof. It will also review the limitations of the study and propose opportunities for future research.

Importantly, the objective here is just to give the reader a taste of what’s to come (a roadmap of sorts), not a summary of the chapter. So, keep it short and sweet – a paragraph or two should be ample.

Step 2: Discuss the overall findings in relation to the research aims

The next step in writing your conclusions chapter is to discuss the overall findings of your study , as they relate to the research aims and research questions . You would have likely covered similar ground in the discussion chapter, so it’s important to zoom out a little bit here and focus on the broader findings – specifically, how these help address the research aims .

In practical terms, it’s useful to start this section by reminding your reader of your research aims and research questions, so that the findings are well contextualised. In this section, phrases such as, “This study aimed to…” and “the results indicate that…” will likely come in handy. For example, you could say something like the following:

This study aimed to investigate the feeding habits of the naked mole-rat. The results indicate that naked mole rats feed on underground roots and tubers. Further findings show that these creatures eat only a part of the plant, leaving essential parts to ensure long-term food stability.

Be careful not to make overly bold claims here. Avoid claims such as “this study proves that” or “the findings disprove existing the existing theory”. It’s seldom the case that a single study can prove or disprove something. Typically, this is achieved by a broader body of research, not a single study – especially not a dissertation or thesis which will inherently have significant and limitations. We’ll discuss those limitations a little later.

Step 3: Discuss how your study contributes to the field

Next, you’ll need to discuss how your research has contributed to the field – both in terms of theory and practice . This involves talking about what you achieved in your study, highlighting why this is important and valuable, and how it can be used or applied.

In this section you’ll want to:

- Mention any research outputs created as a result of your study (e.g., articles, publications, etc.)

- Inform the reader on just how your research solves your research problem , and why that matters

- Reflect on gaps in the existing research and discuss how your study contributes towards addressing these gaps

- Discuss your study in relation to relevant theories . For example, does it confirm these theories or constructively challenge them?

- Discuss how your research findings can be applied in the real world . For example, what specific actions can practitioners take, based on your findings?

Be careful to strike a careful balance between being firm but humble in your arguments here. It’s unlikely that your one study will fundamentally change paradigms or shake up the discipline, so making claims to this effect will be frowned upon . At the same time though, you need to present your arguments with confidence, firmly asserting the contribution your research has made, however small that contribution may be. Simply put, you need to keep it balanced .

Step 4: Reflect on the limitations of your study

Now that you’ve pumped your research up, the next step is to critically reflect on the limitations and potential shortcomings of your study. You may have already covered this in the discussion chapter, depending on your university’s structural preferences, so be careful not to repeat yourself unnecessarily.

There are many potential limitations that can apply to any given study. Some common ones include:

- Sampling issues that reduce the generalisability of the findings (e.g., non-probability sampling )

- Insufficient sample size (e.g., not getting enough survey responses ) or limited data access

- Low-resolution data collection or analysis techniques

- Researcher bias or lack of experience

- Lack of access to research equipment

- Time constraints that limit the methodology (e.g. cross-sectional vs longitudinal time horizon)

- Budget constraints that limit various aspects of the study

Discussing the limitations of your research may feel self-defeating (no one wants to highlight their weaknesses, right), but it’s a critical component of high-quality research. It’s important to appreciate that all studies have limitations (even well-funded studies by expert researchers) – therefore acknowledging these limitations adds credibility to your research by showing that you understand the limitations of your research design .

That being said, keep an eye on your wording and make sure that you don’t undermine your research . It’s important to strike a balance between recognising the limitations, but also highlighting the value of your research despite those limitations. Show the reader that you understand the limitations, that these were justified given your constraints, and that you know how they can be improved upon – this will get you marks.

Next, you’ll need to make recommendations for future studies. This will largely be built on the limitations you just discussed. For example, if one of your study’s weaknesses was related to a specific data collection or analysis method, you can make a recommendation that future researchers undertake similar research using a more sophisticated method.

Another potential source of future research recommendations is any data points or analysis findings that were interesting or surprising , but not directly related to your study’s research aims and research questions. So, if you observed anything that “stood out” in your analysis, but you didn’t explore it in your discussion (due to a lack of relevance to your research aims), you can earmark that for further exploration in this section.

Essentially, this section is an opportunity to outline how other researchers can build on your study to take the research further and help develop the body of knowledge. So, think carefully about the new questions that your study has raised, and clearly outline these for future researchers to pick up on.

Step 6: Wrap up with a closing summary

Quick tips for a top-notch conclusion chapter

Now that we’ve covered the what , why and how of the conclusion chapter, here are some quick tips and suggestions to help you craft a rock-solid conclusion.

- Don’t ramble . The conclusion chapter usually consumes 5-7% of the total word count (although this will vary between universities), so you need to be concise. Edit this chapter thoroughly with a focus on brevity and clarity.

- Be very careful about the claims you make in terms of your study’s contribution. Nothing will make the marker’s eyes roll back faster than exaggerated or unfounded claims. Be humble but firm in your claim-making.

- Use clear and simple language that can be easily understood by an intelligent layman. Remember that not every reader will be an expert in your field, so it’s important to make your writing accessible. Bear in mind that no one knows your research better than you do, so it’s important to spell things out clearly for readers.

Hopefully, this post has given you some direction and confidence to take on the conclusion chapter of your dissertation or thesis with confidence. If you’re still feeling a little shaky and need a helping hand, consider booking a free initial consultation with a friendly Grad Coach to discuss how we can help you with hands-on, private coaching.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

17 Comments

Really you team are doing great!

Your guide on writing the concluding chapter of a research is really informative especially to the beginners who really do not know where to start. Im now ready to start. Keep it up guys

Really your team are doing great!

Very helpful guidelines, timely saved. Thanks so much for the tips.

This post was very helpful and informative. Thank you team.

A very enjoyable, understandable and crisp presentation on how to write a conclusion chapter. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Thanks Jenna.

This was a very helpful article which really gave me practical pointers for my concluding chapter. Keep doing what you are doing! It meant a lot to me to be able to have this guide. Thank you so much.

Nice content dealing with the conclusion chapter, it’s a relief after the streneous task of completing discussion part.Thanks for valuable guidance

Thanks for your guidance

I get all my doubts clarified regarding the conclusion chapter. It’s really amazing. Many thanks.

Very helpful tips. Thanks so much for the guidance

Thank you very much for this piece. It offers a very helpful starting point in writing the conclusion chapter of my thesis.

It’s awesome! Most useful and timely too. Thanks a million times

Bundle of thanks for your guidance. It was greatly helpful.

Wonderful, clear, practical guidance. So grateful to read this as I conclude my research. Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Dissertation Recommendations — How To Write Them

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recommendations are crucial to your paper because they suggest solutions to your research problems. You can include recommendations in the discussion sections of your writing and briefly in the conclusions of your dissertation , thesis, or research paper . This article discusses dissertation recommendations, their purpose, and how to write one.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Dissertation Recommendations — In a Nutshell

- 2 Definition: Dissertation recommendations

- 3 How to write dissertation recommendations

- 4 Dissertation recommendations based on your findings

- 5 Purpose of dissertation recommendations

Dissertation Recommendations — In a Nutshell

- Dissertation recommendations are an important aspect of your research paper.

- They should be specific, measurable, and have the potential of future possibilities.

- Additionally, these recommendations should offer practical insights and suggestions for solving real-life problems.

When making your recommendations, please ensure the following:

- Your recommendations are an extension of your work instead of a basis for self-criticism

- Your research stands independently instead of suggesting recommendations that will complete it

- Your dissertation recommendations offer insights into how future research can build upon it instead of undermining your research

Definition: Dissertation recommendations

Dissertation recommendations are the actionable insights and suggestions presented after you get your research findings. These suggestions are usually based on what you find and help to guide future studies or practical applications. It’s best to place your dissertation recommendations at the conclusion.

How to write dissertation recommendations

When writing your academic paper, you can frame dissertation recommendations using one of the following methods:

Use the problem: In this approach, you should address the issues highlighted in your research.

Offer solutions: You can offer some practical solutions to the problems revealed in your research.

Use a theory: Here, you can base your recommendations on your study’s theoretical approach.

Here are some helpful tips for writing dissertation recommendations that you should incorporate when drafting a research paper:

- Avoid general or vague recommendations

- Be specific and concrete

- Offer measurable insights Ensure your suggestions are practical and implementable

- Avoid focusing on theoretical concepts or new findings but on future possibilities

“Based on the study’s outcomes, it’s recommended that businesses and organizations develop mental health well-being frameworks to reduce workplace stress. This training should be mandatory for all employees and conducted on a monthly basis.”

Dissertation recommendations based on your findings

After analysing your findings, you can divide your dissertation recommendations into two subheadings as discussed below:

What can be done?

This section highlights the steps you can use when conducting the research. You may also include any steps needed to address the issues highlighted in your research question. For instance, if the study reveals a lack of emotional connection between employees, implementing dynamic awareness training or sit-downs could be recommended.

Is further research needed?

This section highlights the benefits of further studies that will help build on your research findings. For instance, if your research found less data on employee mental well-being, your dissertation recommendations could suggest future studies.

Purpose of dissertation recommendations

Note: Dissertation recommendations have the following purposes:

- Provide guidance and improve the quality of further studies based on your research findings

- Offer insights, call to action, or suggest other studies

- Highlight specific, clear, and realistic suggestions for future studies

When writing your dissertation recommendations, always remember to keep them specific, measurable, and clear. You should also ensure that a comprehensible rationale supports these recommendations. Additionally, your requests should always be directly linked to your research and offer suggestions from that angle.

Note that your suggestions should always focus on future possibilities and not on present new findings or theoretical concepts. This is because future researchers may use your results to draw further conclusions and gather new insights from your work.

Can I include new arguments in the conclusion of a dissertation

Dissertations follow a more formal structure; hence, you can only present new arguments in the conclusion. Use your dissertation’s concluding part as a summary of your points or to provide recommendations.

How is the conclusion different from the discussion sections?

The discussion section describes a detailed account of your findings, while the conclusion answers the research question and highlights some recommendations.

What shouldn't I include in the dissertation recommendations?

Avoid concluding with weak statements like “there are good insights from both ends…”, generic phrases like “in conclusion…” or evidence that you failed to mention in the discussion or results section.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

Writing the parts of scientific reports

22 Writing the conclusion & recommendations

There are probably some overlaps between the Conclusion and the Discussion section. Nevertheless, this section gives you the opportunity to highlight the most important points in your report, and is sometimes the only section read. Think about what your research/ study has achieved, and the most important findings and ideas you want the reader to know. As all studies have limitations also think about what you were not able to cover (this shows that you are able to evaluate your own work objectively).

Possible structure of this section:

Use present perfect to sum up/ evaluate:

This study has explored/ has attempted …

Use past tense to state what your aim was and to refer to actions you carried out:

- This study was intended to analyse …

- The aim of this study was to …

Use present tense to evaluate your study and to state the generalizations and implications that you draw from your findings.

- The results add to the knowledge of …

- These findings s uggest that …

You can either use present tense or past tense to summarize your results.

- The findings reveal …

- It was found that …

Achievements of this study (positive)

- This study provides evidence that …

- This work has contributed to a number of key issues in the field such as …

Limitations of the study (negative)

- Several limitations should be noted. First …

Combine positive and negative remarks to give a balanced assessment:

- Although this research is somewhat limited in scope, its findings can provide a basis for future studies.

- Despite the limitations, findings from the present study can help us understand …

Use more cautious language (modal verbs may, can, could)

- There are a number of possible extensions of this research …

- The findings suggest the possibility for future research on …

- These results may be important for future studies on …

- Examining a wider context could/ would lead …

Or indicate that future research is needed

- There is still a need for future research to determine …

- Further studies should be undertaken to discover…

- It would be worthwhile to investigate …

Academic Writing in a Swiss University Context Copyright © 2018 by Irene Dietrichs. All Rights Reserved.

Implications or Recommendations in Research: What's the Difference?

- Peer Review

High-quality research articles that get many citations contain both implications and recommendations. Implications are the impact your research makes, whereas recommendations are specific actions that can then be taken based on your findings, such as for more research or for policymaking.

Updated on August 23, 2022

That seems clear enough, but the two are commonly confused.

This confusion is especially true if you come from a so-called high-context culture in which information is often implied based on the situation, as in many Asian cultures. High-context cultures are different from low-context cultures where information is more direct and explicit (as in North America and many European cultures).

Let's set these two straight in a low-context way; i.e., we'll be specific and direct! This is the best way to be in English academic writing because you're writing for the world.

Implications and recommendations in a research article

The standard format of STEM research articles is what's called IMRaD:

- Introduction

- Discussion/conclusions

Some journals call for a separate conclusions section, while others have the conclusions as the last part of the discussion. You'll write these four (or five) sections in the same sequence, though, no matter the journal.

The discussion section is typically where you restate your results and how well they confirmed your hypotheses. Give readers the answer to the questions for which they're looking to you for an answer.

At this point, many researchers assume their paper is finished. After all, aren't the results the most important part? As you might have guessed, no, you're not quite done yet.

The discussion/conclusions section is where to say what happened and what should now happen

The discussion/conclusions section of every good scientific article should contain the implications and recommendations.

The implications, first of all, are the impact your results have on your specific field. A high-impact, highly cited article will also broaden the scope here and provide implications to other fields. This is what makes research cross-disciplinary.

Recommendations, however, are suggestions to improve your field based on your results.

These two aspects help the reader understand your broader content: How and why your work is important to the world. They also tell the reader what can be changed in the future based on your results.

These aspects are what editors are looking for when selecting papers for peer review.

Implications and recommendations are, thus, written at the end of the discussion section, and before the concluding paragraph. They help to “wrap up” your paper. Once your reader understands what you found, the next logical step is what those results mean and what should come next.

Then they can take the baton, in the form of your work, and run with it. That gets you cited and extends your impact!

The order of implications and recommendations also matters. Both are written after you've summarized your main findings in the discussion section. Then, those results are interpreted based on ongoing work in the field. After this, the implications are stated, followed by the recommendations.

Writing an academic research paper is a bit like running a race. Finish strong, with your most important conclusion (recommendation) at the end. Leave readers with an understanding of your work's importance. Avoid generic, obvious phrases like "more research is needed to fully address this issue." Be specific.

The main differences between implications and recommendations (table)

Now let's dig a bit deeper into actually how to write these parts.

What are implications?

Research implications tell us how and why your results are important for the field at large. They help answer the question of “what does it mean?” Implications tell us how your work contributes to your field and what it adds to it. They're used when you want to tell your peers why your research is important for ongoing theory, practice, policymaking, and for future research.

Crucially, your implications must be evidence-based. This means they must be derived from the results in the paper.

Implications are written after you've summarized your main findings in the discussion section. They come before the recommendations and before the concluding paragraph. There is no specific section dedicated to implications. They must be integrated into your discussion so that the reader understands why the results are meaningful and what they add to the field.

A good strategy is to separate your implications into types. Implications can be social, political, technological, related to policies, or others, depending on your topic. The most frequently used types are theoretical and practical. Theoretical implications relate to how your findings connect to other theories or ideas in your field, while practical implications are related to what we can do with the results.

Key features of implications

- State the impact your research makes

- Helps us understand why your results are important

- Must be evidence-based

- Written in the discussion, before recommendations

- Can be theoretical, practical, or other (social, political, etc.)

Examples of implications

Let's take a look at some examples of research results below with their implications.

The result : one study found that learning items over time improves memory more than cramming material in a bunch of information at once .

The implications : This result suggests memory is better when studying is spread out over time, which could be due to memory consolidation processes.

The result : an intervention study found that mindfulness helps improve mental health if you have anxiety.

The implications : This result has implications for the role of executive functions on anxiety.

The result : a study found that musical learning helps language learning in children .

The implications : these findings suggest that language and music may work together to aid development.

What are recommendations?

As noted above, explaining how your results contribute to the real world is an important part of a successful article.

Likewise, stating how your findings can be used to improve something in future research is equally important. This brings us to the recommendations.

Research recommendations are suggestions and solutions you give for certain situations based on your results. Once the reader understands what your results mean with the implications, the next question they need to know is "what's next?"

Recommendations are calls to action on ways certain things in the field can be improved in the future based on your results. Recommendations are used when you want to convey that something different should be done based on what your analyses revealed.

Similar to implications, recommendations are also evidence-based. This means that your recommendations to the field must be drawn directly from your results.

The goal of the recommendations is to make clear, specific, and realistic suggestions to future researchers before they conduct a similar experiment. No matter what area your research is in, there will always be further research to do. Try to think about what would be helpful for other researchers to know before starting their work.

Recommendations are also written in the discussion section. They come after the implications and before the concluding paragraphs. Similar to the implications, there is usually no specific section dedicated to the recommendations. However, depending on how many solutions you want to suggest to the field, they may be written as a subsection.

Key features of recommendations

- Statements about what can be done differently in the field based on your findings

- Must be realistic and specific

- Written in the discussion, after implications and before conclusions

- Related to both your field and, preferably, a wider context to the research

Examples of recommendations

Here are some research results and their recommendations.

A meta-analysis found that actively recalling material from your memory is better than simply re-reading it .

- The recommendation: Based on these findings, teachers and other educators should encourage students to practice active recall strategies.

A medical intervention found that daily exercise helps prevent cardiovascular disease .

- The recommendation: Based on these results, physicians are recommended to encourage patients to exercise and walk regularly. Also recommended is to encourage more walking through public health offices in communities.

A study found that many research articles do not contain the sample sizes needed to statistically confirm their findings .

The recommendation: To improve the current state of the field, researchers should consider doing power analysis based on their experiment's design.

What else is important about implications and recommendations?

When writing recommendations and implications, be careful not to overstate the impact of your results. It can be tempting for researchers to inflate the importance of their findings and make grandiose statements about what their work means.

Remember that implications and recommendations must be coming directly from your results. Therefore, they must be straightforward, realistic, and plausible.

Another good thing to remember is to make sure the implications and recommendations are stated clearly and separately. Do not attach them to the endings of other paragraphs just to add them in. Use similar example phrases as those listed in the table when starting your sentences to clearly indicate when it's an implication and when it's a recommendation.

When your peers, or brand-new readers, read your paper, they shouldn't have to hunt through your discussion to find the implications and recommendations. They should be clear, visible, and understandable on their own.

That'll get you cited more, and you'll make a greater contribution to your area of science while extending the life and impact of your work.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

- Section 3: Home

- Qualtrics Survey Tool

- Statistics Help This link opens in a new window

- Statistics and APA Format This link opens in a new window

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Evaluation of Outcomes

Positioning your Research in the Field

- Hypothesis Testing This link opens in a new window

- Doctoral Project/Dissertation-in-Practice Title Tips

- Proofreading Service in the ASC This link opens in a new window

Findings, Evaluation, Implications, and Recommendations for Research: Positioning your Research in the Field

The third section of your dissertation is where you show how your work fits in the existing field of literature and establishes your position as a scholar and practitioner in the field. This is the culmination of all your work and effort. The results of your research will show how your findings relate to those existing studies about your topic.

Think of the topic you investigated as a giant crossword puzzle. Your work is one piece that will help provide a better understanding of the reasons behind the problem. What does your work mean for others in the field? Your findings may complement existing studies or present new ideas about the problem. What needs to be addressed or changed about how things are being done? Based on your findings and the implications from those findings, what specific things can be done to improve practice? What actions can be taken to make things better?

Your recommendations for others in the field will provide ways to apply the results of your work. Based on your results and implications, they provide examples of practical actions and suggestions for additional research to add to the understanding of the problem you investigated. As a scholar, these are your contributions to the field.

- What did your data reveal?

- What did you find related to the problem?

Evaluation of the Outcomes

- How do your findings confirm or contradict the existing literature?

- What new things did you discover?

Implications

- Where does your work fit?

- What do your findings suggest to those working in the field?

Recommendations for Practice

- Based on your Findings and Implications, what specific actions should be taken to address the problem?

- << Previous: Evaluation of Outcomes

- Next: Hypothesis Testing >>

- Last Updated: Jan 16, 2024 12:09 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013606

How to write recommendations in a research paper

Many students put in a lot of effort and write a good report however they are not able to give proper recommendations. Recommendations in the research paper should be included in your research. As a researcher, you display a deep understanding of the topic of research. Therefore you should be able to give recommendations. Here are a few tips that will help you to give appropriate recommendations.

Recommendations in the research paper should be the objective of the research. Therefore at least one of your objectives of the paper is to provide recommendations to the parties associated or the parties that will benefit from your research. For example, to encourage higher employee engagement HR department should make strategies that invest in the well-being of employees. Additionally, the HR department should also collect regular feedback through online surveys.

Recommendations in the research paper should come from your review and analysis For example It was observed that coaches interviewed were associated with the club were working with the club from the past 2-3 years only. This shows that the attrition rate of coaches is high and therefore clubs should work on reducing the turnover of coaches.

Recommendations in the research paper should also come from the data you have analysed. For example, the research found that people over 65 years of age are at greater risk of social isolation. Therefore, it is recommended that policies that are made for combating social isolation should target this specific group.

Recommendations in the research paper should also come from observation. For example, it is observed that Lenovo’s income is stable and gross revenue has displayed a negative turn. Therefore the company should analyse its marketing and branding strategy.

Recommendations in the research paper should be written in the order of priority. The most important recommendations for decision-makers should come first. However, if the recommendations are of equal importance then it should come in the sequence in which the topic is approached in the research.

Recommendations in a research paper if associated with different categories then you should categorize them. For example, you have separate recommendations for policymakers, educators, and administrators then you can categorize the recommendations.

Recommendations in the research paper should come purely from your research. For example, you have written research on the impact on HR strategies on motivation. However, nowhere you have discussed Reward and recognition. Then you should not give recommendations for using rewards and recognition measures to boost employee motivation.