United States

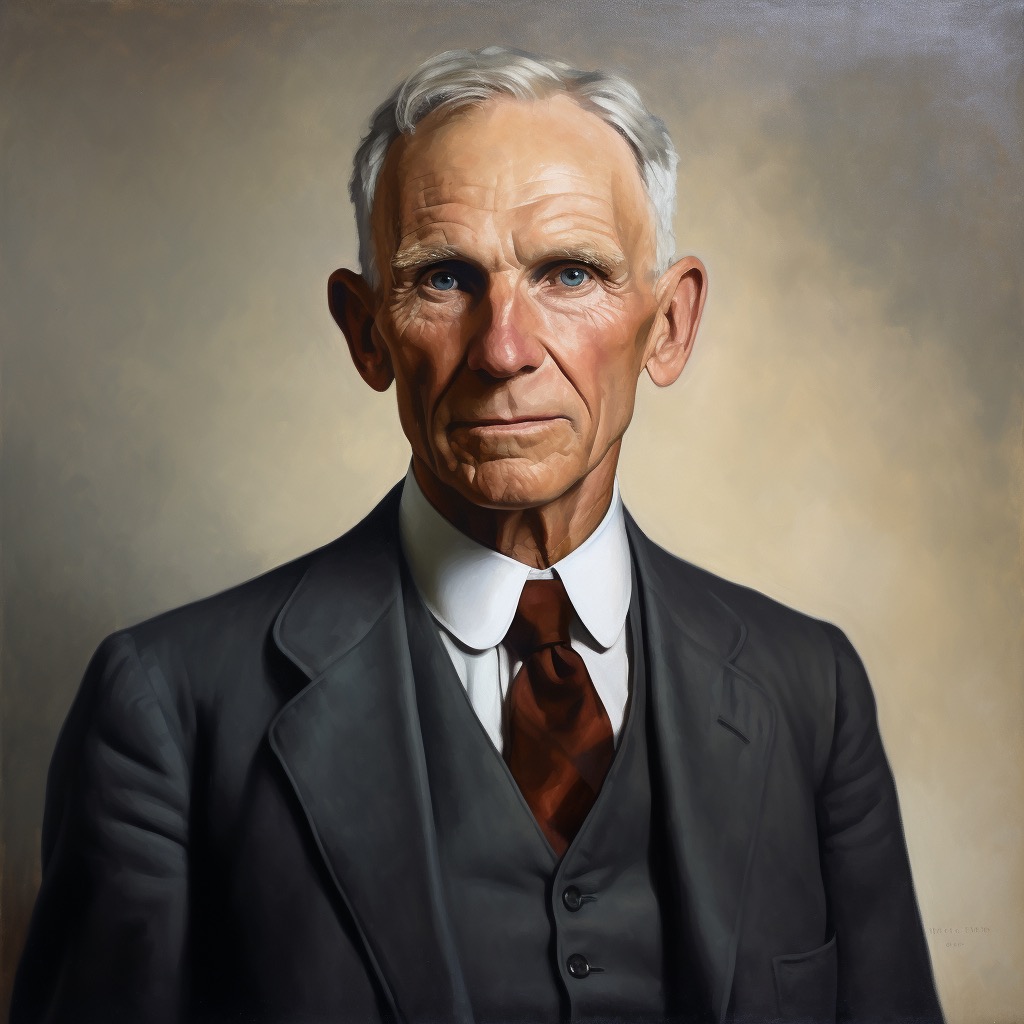

Henry Ford Biography

Ford Motor Company Founder

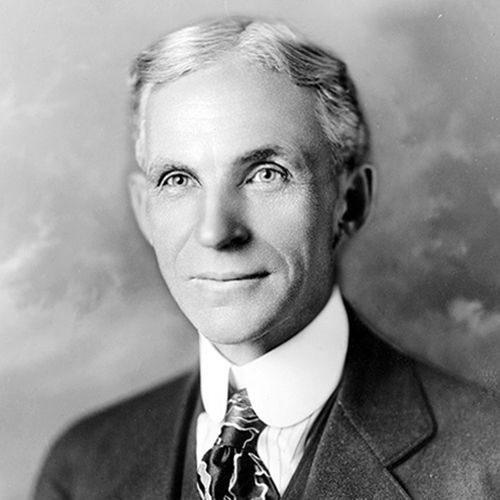

Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company, was born in Springwells Township, Wayne County, Michigan, on July 30, 1863, to Mary (Litogot) and William Ford. He was the eldest of six children in a family of four boys and two girls. His father was a native of County Cork, Ireland, who came to America in 1847 and settled on a farm in Wayne County.

Young Henry Ford showed an early interest in mechanics. By the time he was 12, he was spending most of his spare time in a small machine shop he had equipped himself. There, at 15, he constructed his first steam engine.

Later, he became a machinist’s apprentice in Detroit in the shops of James F. Flower and Brothers, and in the plant of the Detroit Dry Dock Company. After completing his apprenticeship in 1882, he spent a year setting up and repairing Westinghouse steam engines in southern Michigan. In July 1891, he was employed as an engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit. He became chief engineer on November 6, 1893. Thomas Edison would become a lifelong mentor and friend to Henry Ford.

On April 11, 1888, Henry married Clara Jane Bryant of Greenfield, Michigan, the daughter of Martha (Bench) and Melvin Bryant, a Wayne County farmer. Clara lived to the age of 84 and died on September 29, 1950. They had one child, son Edsel Bryant Ford was born on November 6, 1893.

Henry Ford’s career as a builder of automobiles dated from the winter of 1893 when his interest in internal combustion engines led him to construct a small one-cylinder gasoline model. The first Ford engine sputtered its way to life on a wooden table in the kitchen of the Ford home at 58 Bagley Avenue in Detroit. A later version of that engine powered his first automobile, which was essentially a frame fitted with four bicycle wheels. This first Ford car, the Quadricycle, was completed in June 1896.

On August 19, 1899, he resigned from the Edison Illuminating Company and, with others, organized the Detroit Automobile Company, which went into bankruptcy about 18 months later. Meanwhile, Henry Ford designed and built several racing cars. In one of them, called Sweepstakes, he defeated Alexander Winton on a track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan on October 10, 1901. One month later, Henry Ford founded his second automobile venture, the Henry Ford Company. He would leave that enterprise, which would become the Cadillac Motor Car Company, in early 1902. In another of his racing cars, the 999, he established a world record for the mile, covering the distance in 39.4 seconds on January 12, 1904 on the winter ice of Lake St. Clair.

On June 16, 1903, Henry and 12 others invested $28,000 and created Ford Motor Company. The first car built by the Company was sold July 15, 1903. Henry owned 25.5% of the stock in the new organization. He became president and controlling owner in 1906. In 1919, Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford acquired the interest of all minority stockholders for $105,820,894 and became the sole owners of the Company. Edsel, who succeeded his father as president in 1919, occupied that position until his death in 1943, when Henry Ford returned to the post.

In September, 1945, when he resigned the presidency for a second time, Henry Ford recommended that his grandson, Henry Ford II, be elected to the position. The board of directors followed his recommendation.

In 1946, Henry Ford was lauded at the Automotive Golden Jubilee for his contributions to the automotive industry. In July of that same year, 50,000 people cheered for him in Dearborn at a giant 83rd birthday party. Later that year, the American Petroleum Institute awarded him its first Gold Medal annual award for outstanding contributions to the welfare of humanity. The United States government honored him in 1965 by featuring his likeness with a Model T on a postage stamp as part of their Prominent Americans series. In 1999, Fortune magazine named Henry Ford the Businessman of the Century.

In collaboration with Samuel Crowther, he wrote My Life and Work (1922), Today and Tomorrow (1926), and Moving Forward (1930), which described the development of Ford Motor Company and outlined his industrial and social theories. He also published Edison, As I Know Him (1930), with the same collaborator. Doctor of Engineering degrees were conferred on him by the University of Michigan and Michigan State College (now Michigan State University), and he received an honorary Doctor of Law degree from Colgate University.

Henry Ford died at his residence, Fair Lane Estate in Dearborn, at 11:40pm on Monday, April 7, 1947, following a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 83 years old. At his bedside were Clara Ford and members of their household staff. At the time of his death, flooding on the Rouge River, which flows through the grounds of Fair Lane, had cut off electrical power. Old-fashioned kerosene lamps and candles were the only sources of light in the house, creating a scene similar to his birth in the same county many years before.

Funeral services were held at St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral in Detroit, Michigan, and Henry Ford was laid to rest in the family cemetery at St. Martha’s Episcopal Church, in Detroit.

Discover More

You may also like.

A Century of Tailgate Innovation

Women of Ford Part 3: 1990s-2020s

Women of Ford Part 2: 1950s-1980s

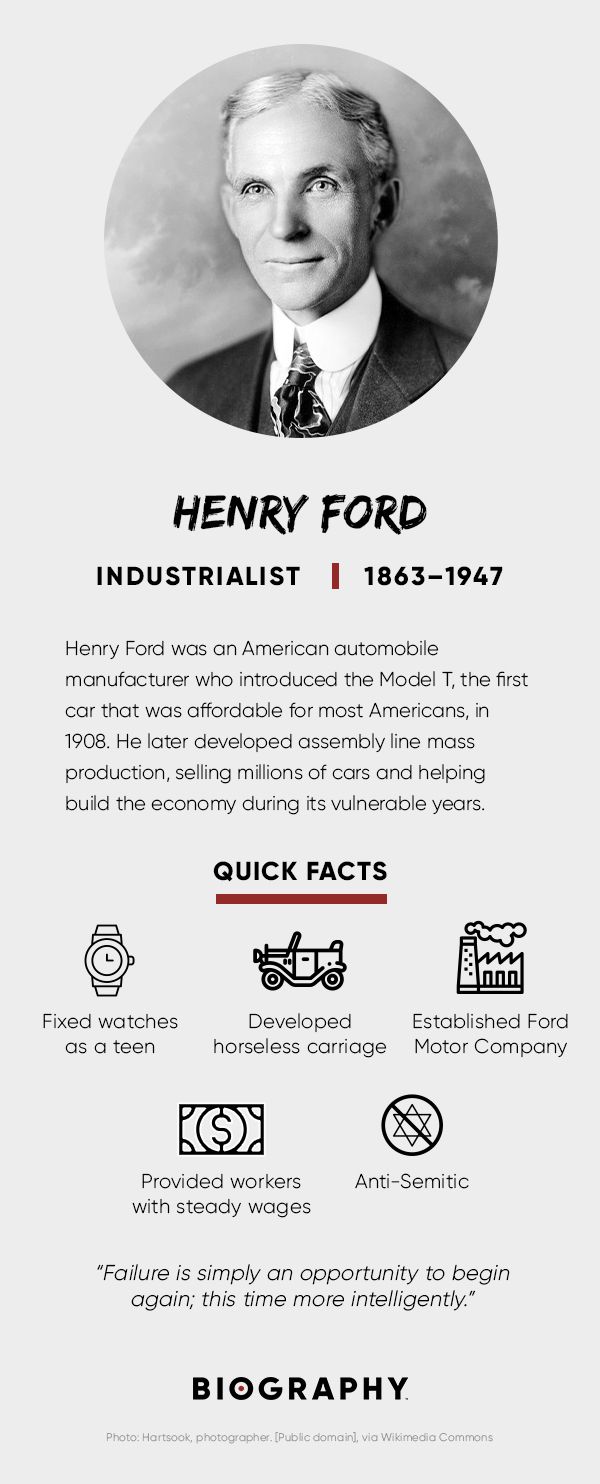

Henry Ford was an industrialist who revolutionized assembly line production for the automobile, making the Model T one of America’s greatest inventions.

(1863-1947)

Who Was Henry Ford?

Henry Ford was an American automobile manufacturer who created the Model T in 1908 and went on to develop the assembly line mode of production, which revolutionized the automotive industry.

As a result, Ford sold millions of cars and became a world-famous business leader. The company later lost its market dominance but had a lasting impact on other technological development, on labor issues and on U.S. infrastructure. Today, Ford is credited for helping to build America's economy during the nation's vulnerable early years and is considered one of America's leading businessmen.

Early Life and Education

Ford was born on July 30, 1863, on his family's farm in Wayne County, near Dearborn, Michigan.

When Ford was 13 years old, his father gifted him a pocket watch, which the young boy promptly took apart and reassembled. Friends and neighbors were impressed and requested that he fix their timepieces too.

Unsatisfied with farm work, Ford left home at the age of 16 to take an apprenticeship as a machinist at a shipbuilding firm in Detroit. In the years that followed, he would learn to skillfully operate and service steam engines and would also study bookkeeping.

In 1888, Ford married Clara Ala Bryant. The couple had a son, Edsel, in 1893.

In 1890, Ford was hired as an engineer for the Detroit Edison Company. In 1893, his natural talents earned him a promotion to chief engineer.

All the while, Ford developed his plans for a horseless carriage. In 1892, Ford built his first gasoline-powered buggy, which had a two-cylinder, four-horsepower engine. In 1896, he constructed his first model car, the Ford Quadricycle.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S HENRY FORD FACT CARD

Ford Motor Company

By 1898, Ford was awarded with his first patent for a carburetor. In 1899, with money raised from investors following the development of a third model car, Ford left Edison Illuminating Company to pursue his car-making business full-time.

After a few trials building cars and companies, Ford established the Ford Motor Company in 1903.

Ford introduced the Model T , the first car to be affordable for most Americans, in October 1908 and continued its construction until 1927. Also known as the “Tin Lizzie,” the car was known for its durability and versatility, quickly making it a huge commercial success.

For several years, Ford Motor Company posted 100 percent gains. Simple to drive and cheap to repair, especially following Ford’s invention of the assembly line, nearly half of all cars in America in 1918 were Model T's.

By 1927, Ford and his son Edsel introduced another successful car, the Model A, and the Ford Motor Company grew into an industrial behemoth.

Henry Ford's Assembly Line

In 1913, Ford launched the first moving assembly line for the mass production of the automobile. This new technique decreased the amount of time it took to build a car from 12 hours to two and a half, which in turn lowered the cost of the Model T from $850 in 1908 to $310 by 1926 for a much-improved model.

In 1914, Ford introduced the $5 wage for an eight-hour workday ($110 in 2011), more than double what workers were previously making on average, as a method of keeping the best workers loyal to his company.

More than for his profits, Ford became renowned for his revolutionary vision: the manufacture of an inexpensive automobile made by skilled workers who earn steady wages and enjoyed a five-day, 40-hour work week.

Philosophy and Philanthropy

Ford was an ardent pacifist and opposed World War I , even funding a peace ship to Europe. Later, in 1936, Ford and his family established the Ford Foundation to provide ongoing grants for research, education and development.

In business, Ford offered profit sharing to select employees who stayed with the company for six months and, most important, who conducted their lives in a respectable manner.

At the same time, the company's "Social Department" looked into an employee’s drinking, gambling and otherwise uncouth activities to determine eligibility for participation.

Henry Ford, Anti-Semite

Despite Ford’s philanthropic leanings, he was a committed anti-Semite. He even went as far as to support a weekly newspaper, The Dearborn Independent , which furthered such views.

Ford published a number of anti-Semitic pamphlets, including a 1921 pamphlet, "The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem.” Ford was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the most important award Nazis gave to foreigners, by Adolf Hitler in 1938.

In 1998, a lawsuit filed in Newark, New Jersey, accused the Ford Motor Company of profiting from the forced labor of thousands of people at one of its truck factories in Cologne, Germany during World War II . The Ford company, in turn, said the factory was under the control of the Nazis, not the American corporate headquarters.

In 2001, Ford Motor Company released a study which found that the company did not profit from the German subsidiary, at the same time promising to donate $4 million to human rights studies focused on slavery and forced labor.

Ford died on April 7, 1947, of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 83, near his Dearborn estate, Fair Lane.

Henry Ford Museum

Ford was an avid collector of Americana, with a particular interest in technological innovations and the lives of ordinary people: farmers, factory workers, shopkeepers and business people. He decided to create a place where their lives and interests could be celebrated.

Opening in 1933, the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, displays the thousands of objects Ford collected and many more-recent additions, such as clocks and watches, an Oscar Mayer Wienermobile, presidential limousines and other exhibits.

Also on display in the expansive outdoor Greenfield Village are operational railroad roundhouses and engines, the Wright Brothers bicycle shop, a replica of Thomas Edison's Menlo Park laboratory and Ford's relocated birthplace.

Ford's vision for the museum was stated as, "When we are through, we shall have reproduced American life as lived; and that, I think, is the best way of preserving at least a part of our history and tradition."

Thomas Edison

"],["

Adolf Hitler

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Henry Ford

- Birth Year: 1863

- Birth date: July 30, 1863

- Birth State: Michigan

- Birth City: Wayne County

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Henry Ford was an industrialist who revolutionized assembly line production for the automobile, making the Model T one of America’s greatest inventions.

- Business and Industry

- Astrological Sign: Leo

- Goldsmith, Bryant & Stratton Business College in Detroit

- Interesting Facts

- Upon Thomas Edison's blessing, Henry Ford sought to make a better car model and eventually started his own company.

- Ford became renowned for his revolutionary vision: the manufacture of an inexpensive automobile made by skilled workers who earn steady wages.

- Despite his pacifism and philanthropy, Ford was strongly anti-Semitic.

- Death Year: 1947

- Death date: April 7, 1947

- Death State: Michigan

- Death City: Dearborn

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Henry Ford Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/business-leaders/henry-ford

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 5, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- The only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history we make today.

- Failure is simply an opportunity to begin again; this time more intelligently.

- The only real mistake is one from which we learn nothing.

- If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said, 'Faster horses.'

- Enthusiasm is the yeast that makes your hopes shine to the stars.

- Vision without execution is just hallucination.

- A business that makes nothing but money is a poor business.

- You don't have to hold a position in order to be a leader.

- Quality means doing it right when no one is looking.

- Don't find fault, find a remedy.

- Whether you think you can, or you think you can't—you're right.

Philanthropists

Tyler Childers

Prince William

Michelle Obama

Oprah Winfrey

Madam C.J. Walker

Alec Baldwin

Prince Harry

Jimmy Carter

Rosalynn Carter

Dolly Parton

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,299 free eBooks

- 2 by Samuel Crowther

- 2 by Henry Ford

My Life and Work by Samuel Crowther and Henry Ford

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 26, 2020 | Original: November 9, 2009

While working as an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit, Henry Ford (1863-1947) built his first gasoline-powered horseless carriage, the Quadricycle, in the shed behind his home. In 1903, he established the Ford Motor Company, and five years later the company rolled out the first Model T. In order to meet overwhelming demand for the revolutionary vehicle, Ford introduced revolutionary new mass-production methods, including large production plants, the use of standardized, interchangeable parts and, in 1913, the world’s first moving assembly line for cars. Enormously influential in the industrial world, Ford was also outspoken in the political realm. Ford drew controversy for his pacifist stance during the early years of World War I and earned widespread criticism for his anti-Semitic views and writings.

Henry Ford: Early Life & Engineering Career

Born in 1863, Henry Ford was the first surviving son of William and Mary Ford, who owned a prosperous farm in Dearborn, Michigan. At 16, he left home for the nearby city of Detroit, where he found apprentice work as a machinist. He returned to Dearborn and work on the family farm after three years, but continued to operate and service steam engines and work occasional stints in Detroit factories. In 1888, he married Clara Bryant, who had grown up on a nearby farm.

Did you know? The mass production techniques Henry Ford championed eventually allowed Ford Motor Company to turn out one Model T every 24 seconds.

In the first several years of their marriage, Ford supported himself and his new wife by running a sawmill. In 1891, he returned with Clara to Detroit, where he was hired as an engineer for the Edison Illuminating Company. Rising quickly through the ranks, he was promoted to chief engineer two years later. Around the same time, Clara gave birth to the couple’s only son, Edsel Bryant Ford. On call 24 hours a day for his job at Edison, Ford spent his irregular hours on his efforts to build a gasoline-powered horseless carriage, or automobile. In 1896, he completed what he called the “Quadricycle,” which consisted of a light metal frame fitted with four bicycle wheels and powered by a two-cylinder, four-horsepower gasoline engine.

Henry Ford: Birth of Ford Motor Company and the Model T

Determined to improve upon his prototype, Ford sold the Quadricycle in order to continue building other vehicles. He received backing from various investors over the next seven years, some of whom formed the Detroit Automobile Company (later the Henry Ford Company) in 1899. His partners, eager to put a passenger car on the market, grew frustrated with Ford’s constant need to improve, and Ford left his namesake company in 1902. (After his departure, it was reorganized as the Cadillac Motor Car Company.) The following year, Ford established the Ford Motor Company.

A month after the Ford Motor Company was established, the first Ford car—the two-cylinder, eight-horsepower Model A—was assembled at a plant on Mack Avenue in Detroit. At the time, only a few cars were assembled per day, and groups of two or three workers built them by hand from parts that were ordered from other companies. Ford was dedicated to the production of an efficient and reliable automobile that would be affordable for everyone; the result was the Model T , which made its debut in October 1908.

Henry Ford: Production & Labor Innovations

The “Tin Lizzie,” as the Model T was known, was an immediate success, and Ford soon had more orders than the company could satisfy. As a result, he put into practice techniques of mass production that would revolutionize American industry, including the use of large production plants; standardized, interchangeable parts; and the moving assembly line. Mass production significantly cut down on the time required to produce an automobile, which allowed costs to stay low. In 1914, Ford also increased the daily wage for an eight-hour day for his workers to $5 (up from $2.34 for nine hours), setting a standard for the industry.

Even as production went up, demand for the Tin Lizzie remained high, and by 1918, half of all cars in America were Model Ts. In 1919, Ford named his son Edsel as president of Ford Motor Company, but he retained full control of the company’s operations. After a court battle with his stockholders, led by brothers Horace and John Dodge, Henry Ford bought out all minority stockholders by 1920. In 1927, Ford moved production to a massive industrial complex he had built along the banks of the River Rouge in Dearborn, Michigan. The plant included a glass factory, steel mill, assembly line and all other necessary components of automotive production. That same year, Ford ceased production of the Model T, and introduced the new Model A, which featured better horsepower and brakes, among other improvements. By that time, the company had produced some 15 million Model Ts, and Ford Motor Company was the largest automotive manufacturer in the world. Ford opened plants and operations throughout the world.

Henry Ford: Later Career & Controversial Views

The Model A proved to be a relative disappointment, and was outsold by both Chevrolet (made by General Motors) and Plymouth (made by Chrysler); it was discontinued in 1931. In 1932, Ford introduced the first V-8 engine, but by 1936 the company had dropped to number three in sales in the automotive industry. Despite his progressive policies regarding the minimum wage, Ford waged a long battle against unionization of labor, refusing to come to terms with the United Automobile Workers (UAW) even after his competitors did so. In 1937, Ford security staff clashed with UAW organizers in the so-called “Battle of the Overpass,” at the Rouge plant, after which the National Labor Relations Board ordered Ford to stop interfering with union organization. Ford Motor Company signed its first contract with UAW in 1941, but not before Henry Ford considered shutting down the company to avoid it.

Ford’s political views earned him widespread criticism over the years, beginning with his campaign against U.S. involvement in World War I . He made a failed bid for a U.S. Senate seat in 1918, narrowly losing in a campaign marked by personal attacks from his opponent. In the Dearborn Independent, a local newspaper he bought in 1918, Ford published a number of anti-Semitic writings that were collected and published as a four volume set called The International Jew. Though he later renounced the writings and sold the paper, he expressed admiration for Adolf Hitler and Germany, and in 1938 accepted the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the Nazi regime’s highest medal for a foreigner.

Edsel Ford died in 1943, and Henry Ford returned to the presidency of Ford Motor Company briefly before handing it over to his grandson, Henry Ford II, in 1945. He died two years later at his Dearborn home, at the age of 83.

HISTORY Vault: The Cars That Made America

Explore the stories of the visionaries who built America’s vehicle landscape.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Henry Ford Autobiography ~ My Life and Work

Video item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by Agent Ludville on May 30, 2016

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Site Search

Search our website to find what you’re looking for.

Select Your Language

You can select the language displayed on our website. Click the drop-down menu below and make your selection.

Founder, Ford Motor Company

Retired curator of transportation at The Henry Ford, Bob Casey admits that he is fascinated with the way Ford approached life. "He was one of these people who didn't take a job because he knew how to do it," says Casey during this lengthy video interview. "He often took jobs because he didn't know how to do them, and they were opportunities to learn. It's a very gutsy way to learn."

- Transcript of Bob Casey's Interview About Henry Ford

Be ready to revise any system, scrap any method, abandon any theory, if the success of the job requires it.

His Early Life as an Inventor

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile. He didn’t even invent the assembly line. But more than any other single individual, he was responsible for transforming the automobile from an invention of unknown utility into an innovation that profoundly shaped the 20th century and continues to affect our lives today.

Innovators change things . They take new ideas, sometimes their own, sometimes other people’s, and develop and promote those ideas until they become an accepted part of daily life. Innovation requires self-confidence, a taste for taking risks, leadership ability and a vision of what the future should be. Henry Ford had all these characteristics, but it took him many years to develop all of them fully.

His beginnings were perfectly ordinary. He was born on his father’s farm in what is now Dearborn, Michigan on July 30, 1863. Early on Ford demonstrated some of the characteristics that would make him successful, powerful, and famous. He organized other boys to build rudimentary water wheels and steam engines. He learned about full-sized steam engines by becoming friends with the men who ran them. He taught himself to fix watches , and used the watches as textbooks to learn the rudiments of machine design. Thus, young Ford demonstrated mechanical ability, a facility for leadership, and a preference for learning by trial-and-error. These characteristics would become the foundation of his whole career.

Ford could have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a farmer. But young Henry was fascinated by machines and was willing to take risks to pursue that fascination. In 1879 he left the farm to become an apprentice at the Michigan Car Company, a manufacturer of railroad cars in Detroit. Over the next two-and-one-half years he held several similar jobs, sometimes moving when he thought he could learn more somewhere else.

He returned home in 1882 but did little farming. Instead he operated and serviced portable steam engines used by farmers, occasionally worked in factories in Detroit, and cut and sold timber from 40 acres of his father’s land. By now Ford was demonstrating another characteristic—a preference for working on his own rather than for somebody else. In 1888 Ford married Clara Bryant and in 1891 they moved to Detroit where Henry had taken a job as night engineer for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company . Ford did not know a great deal about electricity. He saw the job in part as an opportunity to learn.

Henry was an apt pupil, and by 1896 had risen to chief engineer of the Illuminating Company. But he had other interests. He became one of scores of people working in barns and small shops across the country trying to build horseless carriages. Aided by a team of friends, his experiments culminated in 1896 with the completion of his first self-propelled vehicle, the Quadricycle . It had four wire wheels that looked like heavy bicycle wheels, was steered with a tiller like a boat, and had only two forward speeds with no reverse.

A second car followed in 1898. Ford now demonstrated one of the keys to his future success—the ability to articulate a vision and convince other people to sign on and help him achieve that vision. He persuaded a group of businessmen to back him in the biggest risk of his life—a company to make and sell horseless carriages. But Ford knew nothing about running a business, and learning by trial-and-error always involves failure. The new company failed, as did a second. To revive his fortunes Ford took bigger risks, building and even driving racing cars . The success of these cars attracted additional financial backers, and on June 16, 1903 Henry incorporated his third automotive venture, Ford Motor Company .

The Innovator and Ford Motor Company

The early history of Ford Motor Company illustrates one of Henry Ford’s most important talents—an ability to identify and attract outstanding people. He hired a core of young, able men who believed in his vision and would make Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises. The new company’s first car, called the Model A , was followed by a variety of improved models . In 1907 Ford’s four-cylinder, $600 Model N became the best-selling car in the country. But by this time Ford had a bigger vision: a better, cheaper “motorcar for the great multitude.” Working with a hand-picked group of employees he came up with the Model T, introduced on October 1, 1908.

The Model T was easy to operate, maintain, and handle on rough roads. It immediately became a huge success . Ford could easily sell all he could make; but he wanted to make all he could sell. Doing that required a bigger factory. In 1910 the company moved into a huge new plant in Highland Park , Michigan, just north of Detroit. There Ford Motor Company began a relentless drive to increase production and lower costs. Henry and his team borrowed concepts from watch makers, gun makers, bicycle makers, and meat packers, mixed them with their own ideas and by late 1913 they had developed a moving assembly line for automobiles . But Ford workers objected to the never-ending, repetitive work on the new line. Turnover was so high that the company had to hire 53,000 people a year to keep 14,000 jobs filled. Henry responded with his boldest innovation ever—in January 1914 he virtually doubled wages to $5 per day .

At a stroke he stabilized his workforce and gave workers the ability to buy the very cars they made. Model T sales rose steadily as the price dropped. By 1922 half the cars in America were Model Ts and a new two-passenger runabout could be had for as little as $269.

In 1919, tired of “interference” from the other investors in the company, Henry determined to buy them all out. The result was several new Detroit millionaires and a Henry Ford who was the sole owner of the world’s largest automobile company. Ford named his 26-year-old son Edsel as president, but it was Henry who really ran things. Absolute power did not bring wisdom, however.

Success had convinced him of the superiority of his own intuition, and he continued to believe that the Model T was the car most people wanted. He ignored the growing popularity of more expensive but more stylish and comfortable cars like the Chevrolet, and would not listen to Edsel and other Ford executives when they said it was time for a new model.

By the late 1920s even Henry Ford could no longer ignore the declining sales figures. In 1927 he reluctantly shut down the Model T assembly lines and began designing an all-new car. It appeared in December of 1927 and was such a departure from the old Ford that the company went back to the beginning of the alphabet for a name—they called it the Model A .

The new car would not be produced at Highland Park. In 1917 Ford had started construction on an even bigger factory on the Rouge River in Dearborn, Michigan. Iron ore and coal were brought in on Great Lakes steamers and by railroad. By 1927, all steps in the manufacturing process from refining raw materials to final assembly of the automobile took place at the vast Rouge Plant , characterizing Henry Ford’s idea of mass production. In time it would become the world’s largest factory , making not only cars but the steel, glass, tires, and other components that went into the cars.

Henry Ford’s intuitive decision making and one-man control were no longer the formula for success. The Model A was competitive for only four years before being replaced by a newer design. In 1932, at age 69 Ford introduced his last great automotive innovation, the lightweight, inexpensive V8 engine . Even this was not enough to halt his company’s decline. By 1936 Ford Motor Company had fallen to third place in the US market, behind both General Motors and Chrysler Corporation.

In addition to troubles in the marketplace, Ford experienced troubles in the workplace. Struggling during the Great Depression, Ford was forced to lower wages and lay off workers. When the United Auto Workers Union tried to organize Ford Motor Company, Henry wanted no part of such “interference” in running his company. He fought back with intimidation and violence, but was ultimately forced to sign a union contract in 1941.

When World War II began in 1939, Ford, who always hated war, fought to keep the United States from taking sides. But after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor Ford Motor Company became one of the major US military contractors , supplying airplanes, engines, jeeps and tanks.

The influence of the aging Henry Ford, however, was declining. Edsel Ford died in 1943 and two year later Henry officially turned over control of the company to Henry II, Edsel’s son. Henry I retired to Fair Lane, his estate in Dearborn, where he died on April 7, 1947 at age 83.

Henry Ford’s Legacy

Henry Ford had laid the foundation of the twentieth century. The assembly line became the century’s characteristic production mode, eventually applied to everything from phonographs to hamburgers. The vast quantities of war material turned out on those assembly lines were crucial to the Allied victory in World War II. High wage, low skilled factory jobs pioneered by Ford accelerated both immigration from overseas and the movement of Americans from the farms to the cities. The same jobs also accelerated the movement of the same people into an ever expanding middle class. In a dramatic demonstration of the law of unintended consequences, the creation of huge numbers of low skilled workers gave rise in the 1930s to industrial unionism as a potent social and political force. The Model T spawned mass automobility, altering our living patterns, our leisure activities, our landscape, even our atmosphere.

The 10 Best Books on Henry Ford

Essential books on henry ford.

There are countless books on Henry Ford, and it comes with good reason, aside from founding the Ford Motor Company, he developed the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that middle-class Americans could afford, he converted the automobile from an expensive curiosity into an accessible conveyance that profoundly impacted the landscape of the 20th century.

“If money is your hope for independence, you will never have it,” Ford remarked. “The only real security that a man can have in this world is a reserve of knowledge, experience, and ability.”

In order to get to the bottom of what inspired one of history’s most consequential figures to the heights of societal contribution, we’ve compiled a list of the 10 best books on Henry Ford.

I Invented the Modern Age by Richard Snow

Every century or so, our republic has been remade by a new technology: 170 years ago the railroad changed Americans’ conception of space and time; in our era, the microprocessor revolutionized how humans communicate. But in the early twentieth century the agent of creative destruction was the gasoline engine, as put to work by an unknown and relentlessly industrious young man named Henry Ford. Born the same year as the battle of Gettysburg, Ford died two years after the atomic bombs fell, and his life personified the tremendous technological changes achieved in that span.

Growing up as a Michigan farm boy with a bone-deep loathing of farming, Ford intuitively saw the advantages of internal combustion. Resourceful and fearless, he built his first gasoline engine out of scavenged industrial scraps. It was the size of a sewing machine. From there, scene by scene, Richard Snow vividly shows Ford using his innate mechanical abilities, hard work, and radical imagination as he transformed American industry.

In many ways, of course, Ford’s story is well known; in many more ways, it is not. Snow masterfully weaves together a fascinating narrative of Ford’s rise to fame through his greatest invention, the Model T. When Ford first unveiled this car, it took twelve and a half hours to build one. A little more than a decade later, it took exactly one minute. In making his car so quickly and so cheaply that his own workers could easily afford it, Ford created the cycle of consumerism that we still inhabit.

The People’s Tycoon by Steven Watts

How a Michigan farm boy became the richest man in America is a classic, almost mythic tale, but never before has Henry Ford’s outsized genius been brought to life so vividly as it is in this engaging and superbly researched biography.

The real Henry Ford was a tangle of contradictions. He set off the consumer revolution by producing a car affordable to the masses, all the while lamenting the moral toll exacted by consumerism. He believed in giving his workers a living wage, though he was entirely opposed to union labor. He had a warm and loving relationship with his wife, but sired a son with another woman. A rabid anti-Semite, he nonetheless embraced African American workers in the era of Jim Crow.

Uncovering the man behind the myth, situating his achievements and their attendant controversies firmly within the context of early twentieth-century America, Watts has given us a comprehensive, illuminating, and fascinating biography of one of America’s first mass-culture celebrities.

Fordlandia by Greg Gandin

In 1927, Henry Ford, the richest man in the world, bought a tract of land twice the size of Delaware in the Brazilian Amazon. His intention was to grow rubber, but the project rapidly evolved into a more ambitious bid to export America itself, along with its golf courses, ice-cream shops, bandstands, indoor plumbing, and Model Ts rolling down broad streets.

Fordlandia, as the settlement was called, quickly became the site of an epic clash. On one side was the car magnate, lean, austere, the man who reduced industrial production to its simplest motions; on the other, the Amazon, lush, extravagant, the most complex ecological system on the planet. Ford’s early success in imposing time clocks and square dances on the jungle soon collapsed, as indigenous workers, rejecting his midwestern Puritanism, turned the place into a ribald tropical boomtown. Fordlandia’s eventual demise as a rubber plantation foreshadowed the practices that today are laying waste to the rain forest.

More than a parable of one man’s arrogant attempt to force his will on the natural world, Fordlandia depicts a desperate quest to salvage the bygone America that the Ford factory system did much to dispatch. As Greg Grandin shows in this gripping and mordantly observed history, Ford’s great delusion was not that the Amazon could be tamed but that the forces of capitalism, once released, might yet be contained.

Wheels for the World by Douglas G. Brinkley

In this monumental work, one of our finest historians reveals the riveting details of Ford Motor Company’s epic achievements, from the outlandish success of the Model T and V-8 to the glory days of the Thunderbird, Mustang, and Taurus. Brilliant innovators, colorful businessmen, and clever eccentrics, as well as the three Ford factories themselves, all become characters in this gripping drama. Douglas Brinkley is a master at crafting compelling historical narratives, and this exemplary history of one of the preeminent American corporations is his finest achievement yet.

The Vagabonds by Jeff Guin

In 1914 Henry Ford and naturalist John Burroughs visited Thomas Edison in Florida and toured the Everglades. The following year Ford, Edison, and tire maker Harvey Firestone joined together on a summer camping trip and decided to call themselves the Vagabonds. They would continue their summer road trips until 1925, when they announced that their fame made it too difficult for them to carry on.

Although the Vagabonds traveled with an entourage of chefs, butlers, and others, this elite fraternity also had a serious purpose: to examine the conditions of America’s roadways and improve the practicality of automobile travel. Cars were unreliable and the roads were even worse. But newspaper coverage of these trips was extensive, and as cars and roads improved, the summer trip by automobile soon became a desired element of American life.

The Vagabonds is “a portrait of America’s burgeoning love affair with the automobile” (NPR) but it also sheds light on the important relationship between the older Edison and the younger Ford, who once worked for the famous inventor. The road trips made the automobile ubiquitous and magnified Ford’s reputation, even as Edison’s diminished.

My Life and Work by Henry Ford

Widely available via Audible audiobook, this is the original autobiography of Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company. It was originally published in 1922. The autobiography details how Henry Ford started out, how he got into business, the strategies he used to become a successful and immensely wealthy businessman, and how he built a company to last.

The book that has inspired entrepreneurs for generations, not only is My Life and Work by Henry Ford a memoir of an American icon but it also shows the spirit that built America. Written in 1922, this work provides a unique insight into the observations, ideas, and problem-solving skills of this remarkable man.

The Fords: An American Epic by Peter Collier

In The Fords: An American Epic , Peter Collier and David Horowitz tell the riveting story of three generations of Fords, a dramatic story of conflict between fathers and sons played out against the backdrop of America’s greatest industrial empire.

The story begins with the first Henry Ford, the mechanical wizard, tinkerer, and “mad genius” who drove the automobile into the heart of American life and conquered the world with it. An American original, by the end of his life he had become an embittered crank who so possessively loved the company he built that when his son, Edsel, tried to change it to suit the changing times, Henry destroyed him. It was left to Edsel’s son Henry II to avenge him and save the Ford Motor Company in the postwar world.

From the details of the first Henry’s illicit affair and illegitimate son, to the life and loves of “Hank the Deuce” and his celebrated feud with Lee Iacocca, this is an engrossing account of a vital chapter in American history. The authors have added new material to this classic work, showing how Henry II’s line lost out to the line of his brother William Clay Ford in the quest to control this most American of companies in the twenty-first century.

Uncommon Friends by James Newton

James Newton’s Uncommon Friends is “a delightful portrayal of five great men who shared special friendships and common visions” (Booklist). Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, Harvey Firestone, Alexis Carrel, and Charles Lindbergh were twentieth-century giants known personally by very few. In this compelling memoir, James Newton recalls a lifetime of friendship with all of them – a friendship that began when he was only twenty years old and head of development of Edison Park in Fort Meyers, Florida. Based on Newton’s diaries, recollections, and extensive correspondence, this gem among books on Henry Ford is a unique opportunity to share a view of the personal side of some legendary historical figures.

The Public Image of Henry Ford by David L. Lewis

Skillful journalism and meticulous scholarship are combined in the full-bodied portrait of that enigmatic folk hero, Henry Ford, and of the company he built from scratch. Writing with verve and objectivity, David Lewis focuses on the fame, popularity, and influence of America’s most unconventional businessman and traces the history of public relations and advertising within Ford Motor Company and the automobile industry.

Henry Ford and the Jews by Neil Baldwin

This necessary installment among books on Henry Ford shows how he promoted his anti-Semitic views in The Dearborn Independent and other publications and examines the response of the Jewish community in America as well as Ford’s impact on the spread of anti-Semitism in Europe before World War II.

If you enjoyed this guide to the best books on Henry Ford, be sure to check out our list of 20 Inspirational Books Jeff Bezos recommends reading !

- Get Featured

- Our Patreon

- Biographies

Henry Ford: Biography, Success Story, Ford Motor Company

The biography of Henry Ford is an enthralling story of ingenuity, innovation, and indomitable spirit. Henry Ford’s life journey is an inspiring success story that forever altered the course of history. He is a name etched into the chronicles of the time, and his biography is not just a recount of events but a pulsating tale that takes us through the technological renaissance that Ford initiated. He turned once-impossible dreams into tangible realities and paved the way for the automobile industry. This biography navigates his life and explores the myriad facets of a man whose legacy, philosophies, and innovations continue to fuel the engines of present-day visions and beyond.

Table of Contents

Biography Summary

Henry Ford, born on July 30, 1863, in Springwells Township, Michigan, embarked on a journey into the world of automobiles after leaving his family farm at 16 to work in Detroit. His initial encounter with automobiles had occurred a few years earlier, sparking a fascination that would shape the rest of his life. Throughout the late 1880s, Ford commenced his journey in the industry by repairing engines and gradually transitioning into their construction. By the 1890s, he had forged a professional connection with Edison Electric’s automotive division, steadily nurturing his expertise in the field.

Establishing Ford Motor Company

In 1903, after navigating through previous business failures and succeeding in automobile construction, Ford officially founded the Ford Motor Company. The subsequent introduction of the Model T in 1908 not only revolutionized transportation but also had a significant impact on American industry. As the sole owner of Ford Motor Company, he amassed wealth and global recognition, becoming one of the most prosperous and well-known individuals worldwide.

The Impact of “Fordism” on Industry and Labor

Ford’s innovative approach to manufacturing and labor, commonly referred to as “Fordism,” was defined by mass-producing affordable goods while ensuring workers received high wages. He pioneered the establishment of the five-day workweek and ardently believed that consumerism was pivotal to achieving global peace. His unwavering dedication to systematically reducing costs led to numerous technical and business innovations, including a franchise system that expanded dealerships across North America into major cities on six continents.

Contradictions: Peace Advocacy and Antisemitism.

Despite being a known pacifist in the early years of World War I, Ford’s company eventually emerged as a major supplier of weapons during the conflict. He championed the League of Nations, exhibiting a complex and contradictory character. During the 1920s, Ford openly propagated antisemitism through his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent , and the book The International Jew . His opposition to the United States’ entry into World War II was prominent, and for a period, he served on the America First Committee board.

Legacy and Final Years

1943 marked a sorrowful time for Ford, as his son Edsel passed away, prompting him to resume company control. However, his frailty and inability to make decisive decisions swiftly shifted control to his subordinates. By 1945, Ford relinquished the company to his grandson, Henry Ford II. Ford passed away in 1947, leaving most of his wealth to the Ford Foundation and bequeathing control of the company to his family, ensuring that his legacy and influence on the automotive industry and modern industrial practices would endure.

Born in the rural area of Springwells Township, Michigan, on July 30, 1863, Henry Ford was nurtured amidst modest beginnings. His father, William Ford, was an immigrant from County Cork, Ireland, originally hailing from a family that had relocated from Somerset, England, in the 16th century. Conversely, his mother, Mary Ford (née Litogot), was the youngest offspring of Belgian immigrants and was adopted by the O’Herns, neighboring settlers in Michigan, following the premature death of her parents. Henry was the eldest among five children, sharing his childhood with siblings Margaret, Jane, William, and Robert.

His educational journey was brief, concluding his formal studies after completing eighth grade at Springwells Middle School. Subsequent learning ensued through a bookkeeping course at a commercial school, but high school was a path he never ventured upon.

A Natural Aptitude for Mechanics

Henry’s mechanical aptitude manifested early when, at just 12 years of age, he received a pocket watch from his father. He rapidly gained a reputation as a skilled watch repairman among friends and neighbors by meticulously dismantling and reassembling timepieces. His religious commitment was evident through his regular four-mile walks to the Episcopal church every Sunday, even when he was 20.

The death of his mother in 1876 struck a devastating blow to Ford, who had no affection for the farm life his father envisioned for him, stating in retrospection, “I never had any particular love for the farm—it was the mother on the farm I loved.”

Embarking on a Mechanical Journey

In 1879, rejecting the agrarian path laid out for him, Ford vacated the family homestead to immerse himself in the industrial world of Detroit. He apprenticed as a machinist with various companies, including James F. Flower & Bros. and the Detroit Dry Dock Co. By 1882. However, he temporarily returned to Dearborn to tend to the family farm, where he mastered the Westinghouse portable steam engine, later providing servicing for Westinghouse steam engines as an employee.

Intriguingly, two pivotal events at age 12 in 1875 had sown the seeds for Ford’s mechanical future. The gifted watch ignited a lifelong fascination with machinery while observing a Nichols and Shepard road engine, marking his first exposure to a vehicle not dependent on equine power.

Development and Experimentation

In his farm workshop, Ford endeavored to construct a “steam wagon or tractor” and a steam car, albeit with reservations concerning the suitability and safety of steam for lighter vehicles. His early aversions to electricity as a power source were due to the exorbitant cost of trolley wires and the absence of a practical storage battery.

Ford’s mechanical experiments continued to evolve. He repaired an Otto engine in 1885 and fabricated a four-cycle model by 1887. His ventures into automotive engineering took a notable turn in 1892 when he completed his inaugural motor car. It was equipped with a two-cylinder, four-horsepower motor and could reach up to 20 miles per hour. Features such as 28-inch wire bicycle wheels, rubber tires, a foot brake, and a 3-gallon gasoline tank were all present in this rudimentary vehicle. By the spring of 1893, this car was operable, paving the way for further design testing and enhancements on the road. Between 1895 and 1896, Ford piloted the machine for around 1,000 miles, and by 1896, he had embarked on constructing his second car, ultimately crafting three vehicles in his home workshop.

Henry Ford’s story from this point forward reflects a journey of relentless experimentation, failures, and, ultimately, revolutionary success in the automotive industry.

Family Life

On April 11, 1888, Henry Ford married Clara Jane Bryant on a spring day and embarked on a life journey together. Henry was a visionary in the automotive realm and dabbled in various other ventures to sustain his family financially. The Ford family lived modestly, with Henry providing by engaging in farming and overseeing operations at a sawmill.

The couple welcomed their sole child, Edsel Ford, into the world in 1893, a beacon of continuity for the Ford lineage. Edsel, inheriting his father’s inventive and entrepreneurial spirit, would later significantly influence the Ford Motor Company, carving out his legacy while perpetuating the family name in the annals of the automotive industry. Through moments of harmony and hardship, the Ford family navigated the complexities of personal and professional life, binding their names eternally with the epoch-making evolution of transportation.

Early Career and Innovations

In the bustling environment of 1891, Henry Ford embarked on a professional journey with the Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit, securing a position as an engineer. Years later, his enthusiasm and skill facilitated his elevation to Chief Engineer in 1893, providing him with the financial and temporal resources to delve into gasoline engine experiments. Ford’s commitment and innovative spirit birthed a self-propelled vehicle in 1896, christened the Ford Quadricycle, which underwent its inaugural test drive on June 4. The Quadricycle, while a triumph, was seen by Ford as a platform for further refinement and innovation.

Encounters with Thomas Edison

In an intersection of two great minds, 1896 also witnessed Ford being introduced to the renowned Thomas Edison during a meeting with Edison executives. The encounter proved serendipitous as Edison expressed his approval and encouragement of Ford’s vehicular experimentation. Spurred by this, Ford diligently worked to design and actualize a second vehicle by 1898. Subsequently, utilizing the financial backing of Detroit’s lumber baron William H. Murphy, Ford made a pivotal career move. He resigned from the Edison Company, forging a new path in the automotive industry by founding the Detroit Automobile Company on August 5, 1899. Despite ambitions and endeavors, the company faced challenges related to the quality and pricing of the automobiles it produced and eventually dissolved in January 1901.

Accelerating Towards Automotive Success

Navigating through the failed venture, Ford, collaborating with C. Harold Wills, conceived, developed, and triumphantly raced a 26-horsepower automobile in October 1901. This achievement cultivated trust and support from Murphy and other stakeholders, leading to the formation of the Henry Ford Company on November 30, 1901, appointing Ford as chief engineer. However, 1902 brought new challenges as Murphy introduced Henry M. Leland as a consultant, prompting Ford to exit the company, which Leland subsequently rebranded as the Cadillac Automobile Company.

Ford’s tenacity did not wane, and with the alliance of former racing cyclist Tom Cooper, a powerful 80+ horsepower racer named “999” was born, piloted to victory by Barney Oldfield in October 1902. The tapestry of Ford’s career continued to weave with the support of Alexander Y. Malcomson, a coal dealer from the Detroit area. Forming a partnership and adopting the name “Ford & Malcomson, Ltd.”, they aspired to manufacture automobiles that were financially accessible. Ford dedicated himself to designing such a vehicle while leasing a factory and entering a contract with John and Horace E. Dodge’s machine shop for parts supply for $162,500 . Despite slow initial sales and a financial crisis prompted by the Dodge brothers’ payment demand for their first shipment, Ford’s journey in the automotive industry persevered, intertwining his name and legacy with the annals of vehicular evolution.

Ford Motor Company

A momentous gathering occurred in Fort Myers, Florida, on February 11, 1929, where Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and Harvey S. Firestone converged, emblematic of an era where industrial advancements were steering the future.

In a strategic maneuver to safeguard the nascent automotive venture, Alexander Y. Malcomson ushered in a cadre of investors, persuading the Dodge Brothers to take a stake in the burgeoning company. Subsequently, Ford & Malcomson metamorphosed into the Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, backed by a capital of $28,000. The consortium of original investors encompassed figures like Ford himself, Malcomson, the Dodge Brothers, Malcomson’s uncle John S. Gray, secretary James Couzens, and his lawyers, John W. Anderson and Horace Rackham.

Despite Ford’s innovative prowess, his temperament was considered unstable for leadership, leading to Gray being elected as the company president. However, Ford’s inventive spirit was undeterred. On the icy expanses of Lake St. Clair, he unveiled a revolutionary car design, propelling it 1 mile in a mere 39.4 seconds and establishing a new land speed record at 91.3 miles per hour. This event validated Ford’s automotive capabilities and caught the attention of race driver Barney Oldfield.

Captivated by Ford’s engineering marvel, Oldfield dubbed the car “999” in a nod to the era’s fastest locomotive and embarked on a nationwide tour. This journey not only solidified the Ford model “999” as a symbol of automotive prowess but also etched the Ford brand into the consciousness of the United States. Moreover, Ford’s involvement as one of the initial supporters of the Indianapolis 500 underscored the brand’s commitment to innovation and speed, becoming an integral chapter in the annals of American automotive history.

Model T: An Automotive Revolution

On October 1, 1908, a machine that was to become an emblem of its era, the Model T, was unveiled to the world. Priced modestly at $825 ($26,870 in today’s currency), it not only came with the steering wheel on the left – a feature that swiftly became an industry standard – but also boasted an enclosed engine and transmission, a solid block of four cylinders, and a suspension utilizing two semi-elliptic springs. The Model T wasn’t merely a vehicle but a symbol of simplicity, repairability, and affordability. Its unique foot-operated planetary transmission and steering-column-operated throttle-cum-accelerator provided a distinct driving experience, albeit with a learning curve for those acquainted with other vehicles of the time.

Ford orchestrated a prolific publicity machine in Detroit, ensuring stories and advertisements about the Model T permeated every newspaper. The network of local dealers, operating as independent franchises, not only brought wealth to them but also propagated the concept of automobiles throughout North America. Ford’s appeal extended significantly to farmers, who saw the vehicle as a potential asset to their business operations. A surge in sales, sometimes posting 100% gains year-over-year, was a testament to the Model T’s widespread appeal. In 1913, moving assembly belts were introduced into Ford’s plants, enabling a spectacular production upswing, with sales eventually surpassing 250,000 in 1914 and escalating to 472,000 in 1916 as the price dwindled to $360 for the basic touring car model.

By 1918, the Model T dominated the American automotive landscape, accounting for half of all cars in the United States. All new Model Ts were available in one color: black, a policy famously encapsulated by Ford’s statement: “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.” In December 1918, the presidency of Ford Motor Company transitioned from Henry to his son, Edsel Ford, though Henry retained final decision-making authority, often overruling his son. Later, in a strategic play, Henry Ford initiated the Henry Ford and Son Company, strategically coaxing the remaining stakeholders of Ford Motor Company to sell their stakes to him and Edsel, thereby solidifying family control of the company.

New Model Developments

In 1922, the acquisition of Lincoln Motor Co., established by Cadillac founder Henry Leland and his son Wilfred, marked Ford’s entry into the premium car market. Although the Lelands were initially retained for management, they were soon expelled. Henry’s apathy toward luxury vehicles contrasted sharply with Edsel’s vision of expanding Ford into the upscale market, maintaining the original Lincoln Model L in production for a decade before its replacement by the modernized Model K in 1931.

Navigating Through Market Changes and New Challenges

Amidst the burgeoning competition in the mid-1920s, mainly from General Motors (GM) under President Alfred Sloan, Ford found itself at a crossroads. GM’s “price ladder” strategy and its increasing dominance in automotive styling under Harley Earl’s Arts & Color Department posed a significant challenge to Ford’s hitherto unrivaled position in the low-end market. Despite Henry Ford’s reluctance to retire the 16-year-old Model T, competitive pressure, particularly from Chevrolet, coupled with an increasing demand for payment plans and innovative designs, precipitated the development of its successor, the Model A, launched in 1927 after an 18-month production hiatus during which the massive new River Rouge assembly plant was constructed.

Navigating through epochs of tremendous success and periods of competitive challenge, Ford Motor Company, with the Model T as its emblematic product, engineered a remarkable chapter in the annals of American industrial history.

By 1926, the diminishing popularity of the Model T prompted a critical transition within Ford Motor Company, ushering in the era of the Model A. Henry Ford, deeply engrossed in the technical aspects of the engine, chassis, and other mechanical systems, delegated the aesthetic design to his son, despite his self-perception as an engineering specialist. His scant formal training in mechanical engineering, to the extent of being unable to interpret a blueprint, did not stifle his oversight and directional role in Model A’s development, for which a skilled cadre of engineers executed the intricate design tasks. With Edsel’s persistent influence, including a sliding-shift transmission, despite Henry’s initial reservations, came to fruition.

In December 1927, the Ford Model A was introduced, and it saw production until 1931, achieving a remarkable total output exceeding four million units. The Ford company subsequently incorporated an annual model change system, mirroring a strategy recently inaugurated by its rival, General Motors, a system that continues to find utilization amongst modern automakers.

It was not until the 1930s that Ford mollified his aversion towards finance companies, establishing the Ford-owned Universal Credit Corporation as a prominent entity in car financing. Despite this financial innovation, Henry Ford was skeptical toward specific technological advancements such as hydraulic brakes and all-metal roofs, which were only incorporated into Ford vehicles between 1935 and 1936. In contrast, in 1932, the introduction of the flathead Ford V8—the first economical eight-cylinder engine—marked a pivotal moment for the company. Originating from a confidential project initiated in 1930, the flathead V8, whose variants found a place in Ford vehicles for two decades, enhanced Ford’s reputation, rendering it a brand synonymous with performance and adaptability to hot-rodding.

Henry Ford displayed a distinctive disdain for accountancy. Despite accumulating one of the world’s most substantial fortunes, his administration never sought auditing for the company. The absence of a dedicated accounting department led to a peculiar financial management style wherein the company’s financial transactions were estimated, at times, by physically weighing bills and invoices. It wasn’t until 1956 that Ford opened its doors to public trading.

The Introduction of Mercury

In a strategic move significantly driven by Edsel, 1939 witnessed the launch of Mercury, conceptualized as a mid-range brand to contend with Dodge and Buick. Henry Ford, somewhat congruent with his historical tendencies, demonstrated marginal enthusiasm towards this new venture. The introduction of Mercury marked a critical moment in FoFord’sistory, reflecting an attempt to appeal to a broader consumer base and negotiate the competitive automotive landscape with strategic diversification.

From the Model A to the inception of Mercury, FoFord’sourney interweaves technological advancements, strategic shifts, and a complex father-son dynamic, crafting a rich tapestry that underpins the narrative of one of the world-renowned automotive companies. The paradox of innovation and traditionalism within the Ford Motor Company remains emblematic of its founder’s complex persona and the multifaceted path the company would traverse in the automotive industry.

Revolutionary Labor Philosophy

Henry Ford emerged as a vanguard of “welfare capitalism,” an approach architected to elevate the conditions of his workforce and, crucially, mitigate the substantial labor turnover that plagued various departments, compelling them to hire the required workers thrice. The aim is to secure and retain top-tier talent to boost efficiency and productivity.

In a move that dazzled the global stage in 1914, Ford instituted a $5 per day wage, equivalent to $153 in 2023, more than doubling the pay rate for most of his workers. An editorial from a Cleveland, Ohio newspaper metaphorically described the wage announcement as a “blinding rocket” piercing through the gloom of the prevailing industrial depression. This strategy was not merely generous but lucratively strategic: it magnetized Detroit’s crème de la crème of mechanics to Ford, bringing along their invaluable skills and expertise, enhancing productivity, and concurrently reducing training costs. Instituted on January 5, 1914, Ford’s $5-per-day program elevated the minimum daily pay from $2.34 to $5 for eligible male workers.

$5-per-day Wage

Detroit, a city recognized for its high wages, witnessed a cascade effect as competitors, compelled by Ford’s initiative, elevated wages to retain their skilled workforce. Ford’s paradigm demonstrated that augmenting employee wages empowered them to afford the vehicles they manufactured and invigorated the local economy. He envisioned these amplified wages as profit-sharing, rewarding the most diligent and morally upright workers. It’s plausible that James Couzens, a pivotal figure within the company, persuaded Ford to instate the $5-per-day wage.

Employee Lifestyle Scrutiny

The concept extended beyond mere economics: genuine profit-sharing was available to those employed by the company for over six months and, significantly, who led lifestyles approved by Ford’s “Social Department.” This department, employing 50 investigators and support staff, upheld and enforced employee standards, eschewing behaviors such as excessive drinking, gambling, and neglectful parenting. A substantial number of workers could qualify for this “profit-sharing.”

Ford’s venture into scrutinizing his employees’ personal lives was not without controversy. Confronted by the contentious nature of such oversight, Ford retracted from the most invasive aspects of this approach. Reflecting in his 1922 memoir, he acknowledged the misstep of “paternalism” in the industry, asserting that while men may require counsel and assistance, the prevailing “welfare work” that probed into private lives was antiquated. Ford advocated for investment and participation as the linchpin for fortifying the industry and the organization over external social work, albeit maintaining the principle under a modified payment method.

Navigating through Ford’s journey, his innovations in labor philosophy denote a complex amalgamation of economic strategy and moral governance, carving out a path in industrial history that sought to synergize enhanced working conditions with strategic profitability, all while navigating the ethical minefield of employee welfare and privacy. His vision—though at times controversial and paternalistic—indelibly shaped the automotive industry and labor practices, echoing through to modern times.

Five-day Workweek

Henry Ford took a transformative leap in labor relations in an era of relentless industrial toil. Beyond the acclaim for elevating his employees’ wages, Ford introduced an innovative, reduced workweek in 1926, fundamentally altering the temporal landscape of labor in the industrial sector.

Ford and his close collaborator Samuel Crowther envisioned a new workweek schema in 1922, articulated initially as six 8-hour working days, cumulatively forming a 48-hour week. However, a pivotal announcement in 1926 redefined this structure, establishing a paradigm of five 8-hour days, thereby crafting the now-standard 40-hour workweek. This marked a salient departure from the existing norms, whereby Saturday, initially designated as a regular workday, eventually transitioned into a universally accepted day off. On May 1, 1926, factory workers at the Ford Motor Company adopted the five-day, 40-hour workweek model, with the company’s office workers following suit in August of the same year.

Rationale Behind the 40-hour Workweek

Ford’s decision to recalibrate the working week wasn’t merely an act of corporate benevolence but a strategic endeavor to spur productivity by incentivizing workers with additional leisure time. In return for the reduced working hours, an expectation was set: workers would infuse their labor with enhanced vigor and effort. However, the philosophy extended beyond mere productivity metrics. Ford recognized the multifaceted utility of leisure time, not only as a vehicle for worker recovery but also as a conduit to stimulate economic activity, providing workers with the time to purchase and consume goods, thereby lubricating the wheels of the broader economic machine.

Yet, beneath the economic and productivity-driven rationale, a humanitarian ethos also permeated Ford’s decision. He posited, “It is high time to rid ourselves of the notion that leisure for workmen is either ‘lost time’ or a class privilege.” Thus, Ford sought to dismantle the prevailing perception of leisure as a luxury or a dormant period and reframed it as an integral, democratic component of a worker’s life.

Henry Ford’s introduction of the five-day workweek stands as a landmark in labor history, intertwining motives of enhanced productivity, economic stimulation, and charitable considerations. His initiative restructured the temporal contours of industrial labor and embedded a belief in the intrinsic value of leisure, irrevocably altering labor practices that have reverberated to contemporary times.

Labor Unions: A Tumultuous Relationship

The industrial magnate Henry Ford, an individual of immense influence and financial power, harbored a notable aversion towards labor unions. This sentiment found a detailed exposition in chapter 18 of his autobiography, My Life and Work . Ford theorized that despite ostensibly noble intentions, unions were marred by leaders whose actions ultimately yielded more detriment than benefit to the workers. He identified a perceived tendency among unions to limit productivity to safeguard employment—a strategy he found self-defeating, asserting that productivity was pivotal for economic prosperity.

Ford maintained the belief that advances in productivity, while potentially rendering some jobs obsolete, would fuel the broader economy and create new employment opportunities, either within the same enterprise or elsewhere. He posited that union leaders were inherently incentivized to perpetuate socio-economic strife to uphold their authority. At the same time, rational managers would naturally prioritize the welfare of their workers, thereby maximizing their profits. Yet, Ford conceded that numerous managers were ill-equipped or insufficiently skilled to understand this.

Combating Unionization: The Rise of Harry Bennett

To inhibit union activity, Ford appointed Harry Bennett, a former Navy boxer, to lead the Service Department, under whose leadership a regime of intimidation tactics was employed to suppress union organizing. A stark example of the visceral conflict between Ford’s management and union activists materialized on March 7, 1932, amidst the Great Depression, when unemployed auto workers from Detroit orchestrated the Ford Hunger March towards the Ford River Rouge Complex. This escalation led to a brutal confrontation, resulting in over sixty injuries and five deaths as Dearborn police and Ford security personnel opened fire.

A violent encounter occurred on May 26, 1937, when Bennett’s security personnel assaulted United Automobile Workers (UAW) members. One of them is Walter Reuther, an incident that later became known as The Battle of the Overpass after the images of the battered UAW members circulated in the media.

The Inevitable Concession to Unions

Edsel Ford, the company’s president in the late 1930s and early 1940s, believed that a collective bargaining agreement with the unions was imperative, given the unsustainable trajectory of violence and work disruptions. However, Ford, who retained a de facto veto power within the company, remained obstinate. He resolved to keep Bennett responsible for union negotiations, ensuring, as revealed in Charles E. Sorensen’s memoir, that no agreements materialized.

Remarkably, the Ford Motor Company was the last Detroit automaker to recognize the UAW, succumbing only after intense pressure from the more significant automotive industry and the U.S. government. A sit-down strike orchestrated by the UAW in April 1941 closed the River Rouge Plant. Henry Ford, ever-resistant, was reportedly on the brink of dissolving the company rather than yielding to the unions. A pivotal moment arrived when his wife, Clara, threatened to leave him if he dismantled the family business, citing the ensuing chaos as unworthy of the upheaval. Ford, acquiescing to her demands, not only preserved the company but also established it as the automaker with the most UAW-friendly contract terms, signed in June 1941.

The transition from staunch resistance to conceding to the UAW altered Ford’s perspective, as evidenced in a conversation with Walter Reuther, “It was one of the most sensible things Harry Bennett ever did when he got the UAW into this plant.” Ford implied that aligning with the UAW enabled a collective opposition against General Motors and Wall Street. Thus, the relationship between Ford and labor unions, initially defined by conflict and resistance, evolved into a paradoxically cooperative dynamic, revealing industrial relations’ multifaceted and often contradictory nature during this epoch.

Ford Airplane Company

Henry Ford, renowned for his colossal influence in the automotive industry, also explored the azure expanses of the aviation world, particularly during the global conflict of World War I, by constructing Liberty engines. After the hostilities concluded, Ford pivoted back to its foundational automotive manufacturing, that is, until a distinct shift in 1925 with the acquisition of the Stout Metal Airplane Company.

The Ford 4AT Trimotor

One of Ford’s notable achievements in aviation was the conception and manufacturing of the Ford 4AT Trimotor, colloquially known as the “Tin Goose” due to its distinctive corrugated metal framework. The innovative use of a new alloy, Alclad—merging aluminum’s anti-corrosive properties with duralumin’s robustness—marked a significant advancement in aircraft construction. Although the plane bore similarities to Fokker’s V.VII–3m, contributing to whispers that Ford’s engineers may have covertly measured and replicated the Fokker plane, the Trimotor carved its legacy in the aviation annals.

Taking its inaugural flight on June 11, 1926, the Ford 4AT Trimotor emerged as the first successful U.S. passenger airliner despite its rather spartan accommodation for about 12 passengers. Additionally, the U.S. Army utilized several aircraft variants, highlighting its multifaceted applications. Ford ceased production of the Trimotor in 1933, with 199 units built, as the Ford Airplane Division was grounded due to languishing sales amidst the economic turmoil of the Great Depression.

Despite the closure of the airplane division, Ford’s impact on the aviation industry was indelibly etched into history. The Smithsonian Institution extolled Ford for its transformative contributions to aviation. In 1985, a posthumous recognition was bestowed upon Henry Ford with an induction into the National Aviation Hall of Fame, solidifying his and the company’s impact on the aviation sector.

Henry Ford’s foray into aviation, characterized by innovation and challenges alike, mirrors the larger narrative of technological advancements and economic realities of early 20th-century America, painting a multifaceted picture of an industrial titan venturing beyond the confines of terrestrial transportation.

World War I Era: Pacifism Amidst the War

Although renowned for his industrial achievements, Henry Ford navigated the turbulent waters of war and peace during World War I with a notable aversion to conflict. His perception of war as an egregious waste and an obstacle to economic progression led him to support anti-war causes and initiatives fervently.