Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

‘On the Move’ examines how climate change will alter where people live

Journalist Abrahm Lustgarten explores which parts of the United States are most vulnerable to the effects of global warming and how people's lives might change.

‘Space: The Longest Goodbye’ explores astronauts’ mental health

The documentary follows NASA astronauts and the psychologists helping them prepare for future long-distance space trips to the moon and Mars.

‘Countdown’ takes stock of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile

Physicists grapple with their role as stewards of the United States’ aging nuclear weapons in the new book by Sarah Scoles.

A new book explores the transformative power of bird-watching

In Birding to Change the World , environmental scientist Trish O’Kane shows how birds and humans can help one another heal.

How ‘Our Moon’ shaped life on Earth and human history

Science News reviews Rebecca Boyle’s new wide-ranging book, which tells the story of the moon and its relationship with the inhabitants of Earth.

‘Nuts and Bolts’ showcases the 7 building blocks of modern engineering

Science News reviews Roma Agrawal's book, which updates the classic list of simple machines and reveals the heart and soul of engineering.

A new exhibit invites you into the ‘Secret World of Elephants’

As elephants face survival threats, the American Museum of Natural History highlights their pivotal role in shaping landscapes — and their resilience.

Landscape Explorer shows how much the American West has changed

The online tool stitches together historical images into a map that’s helping land managers make decisions about preservation and restoration.

These are Science News ’ favorite books of 2023

Books about deadly fungi, the science of preventing roadkill, trips to other planets and the true nature of math grabbed our attention this year.

‘Most Delicious Poison’ explores how toxins rule our world

In his debut book, Noah Whiteman tours through chemistry, evolution and world history to understand toxins and how we’ve come to use them.

‘Is Math Real?’ asks simple questions to explore math’s deepest truths

In her latest book, mathematician Eugenia Cheng invites readers to see math as more than just right or wrong answers.

‘Our Fragile Moment’ finds modern lessons in Earth’s history of climate

Michael Mann’s latest book, Our Fragile Moment, looks through Earth’s history to understand the current climate crisis.

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 01 December 2021

Industry scores higher than academia for job satisfaction

You have full access to this article via your institution.

In many countries, around half of all researchers work for private companies, which often offer better pay and work–life balance than academia. Credit: Ajpek Orsi/Getty

How does being a researcher in industry compare with being an academic? That’s a question explored in a series of articles pegged to Nature ’s latest survey of salaries and job satisfaction, which concludes this week. The results make for sobering reading for academics, revealing a shift towards industry (see Nature 599 , 519–521; 2021 ).

Scientists who work in industry are more satisfied and better paid than are colleagues in academia, according to the self-selected group of respondents, which comprised more than 3,200 working scientists, mostly from high-income countries. Two-thirds of respondents (65%) are in academia; 15% work in industry. Industry employs, on average, half of the researchers in these countries.

Discrimination still plagues science

Another key finding, covered in this week’s piece on workplace diversity , is that 30% of respondents in academia reported workplace discrimination, harassment or bullying, compared with 15% of those in industry. Industry respondents (64%) are also much more likely than those in academia (42%) to report feeling positively about their careers. That’s a marked shift from the 2016 survey, in which satisfaction levels across the two sectors were neck and neck (63% and 65%, respectively). One research project manager working in the private sector in the United States summed up the latest findings with the words: “I am now an evangelist for all of my friends still in academia to get out and join biotech or any other professional industry.”

The latest findings should sound alarm bells for academic employers at a time when morale in the sector is worsening in many countries. As Nature went to press, academics at 58 UK universities were set to stage a 3-day strike from 1 December as part of an ongoing dispute about pay, working conditions and planned cuts to their pensions.

A separate survey of more than 1,000 UK faculty and staff members carried out between June and August last year revealed a sense that university leaders are using the pandemic as an excuse to push through cost-cutting measures ( R. Watermeyer et al. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 42 , 651–666; 2021 ). Seven out of ten respondents say that this has created a culture of fear, which has, in turn, led to university leadership becoming more autocratic. Many respondents were also concerned that publicly funded academic institutions are increasingly being run as businesses.

How burnout and imposter syndrome blight scientific careers

But if universities truly were like businesses, the survey findings suggest, staff would probably be happier — and would not be looking to leave in the numbers they seem to be.

Nature conducted a small number of interviews with research leaders in industry. One research director at a global bioscience company said that about 60% of job applications come from people in academia. A small proportion of those hired do later return to academia. The director says the company is keen to keep a path for return open, for example by permitting research staff to publish in scientific journals, which is not always an option for researchers in industry.

Labour-market economics offers one explanation for the better pay and greater satisfaction reported by respondents in industry. New companies are popping up every week, and they can struggle to fill vacancies, so will offer higher salaries and additional benefits to attract good candidates. In a number of high-income countries, this is essentially the reverse of the situation in academia, in which postdoctoral researchers greatly outnumber tenure-track positions ( S. C. McConnell et al. eLife 7 , e40189; 2018 ). In these countries, industry contributes around two-thirds of all research and development (R&D) funding. All in all, public institutions (including universities) have less money to spend and more researchers chasing every job.

Stagnating salaries present hurdles to career satisfaction

That said, industry is not at all homogeneous. It ranges from multinational technology and life-sciences companies employing tens of thousands of people to one-person start-ups spun off from universities. And corporate life comes with its own challenges. One head of R&D with experience of working at large pharmaceutical companies said corporate politics and the slow pace of executive decision-making can be frustrating for a researcher who is used to a more hands-on scientific role in an academic lab. By contrast, junior colleagues at smaller companies can enjoy more varied roles in agile working environments before being head-hunted by competitors offering higher salaries.

Clearly, academic salaries are unlikely to be able to compete with those of industry — at least while there are so many more postdocs than positions available. But these two employment destinations need to learn from each other. Researchers looking to switch from academia to industry often have to contend with a supervisor’s disapproval of the move. Such attitudes can discourage researchers from returning to academia, where the perspectives gained in industry could help to re-energize and diversify teams.

Of course, many do find a career in academia hugely rewarding. One academic bioinformatician in the United States who responded to the survey reported earning around 50% of what she was offered for industry positions. She said: “It would be nice if academia could be more competitive with industry, but I love what I do and where I live so I can’t really complain.”

But as competition for scientific talent increases, academic leaders must not assume that that sentiment will prevail. If they want current and future generations of academics to thrive, they need to learn how other sectors succeed in recruiting, retaining and rewarding staff, and consider how to ensure that they are still attractive to the top talent.

Nature 600 , 8 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-03567-3

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Institutions

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

Brazil’s postgraduate funding model is about rectifying past inequalities

Correspondence 09 APR 24

Declining postdoc numbers threaten the future of US life science

Exclusive: official investigation reveals how superconductivity physicist faked blockbuster results

News 06 APR 24

Larger or longer grants unlikely to push senior scientists towards high-risk, high-reward work

Nature Index 25 MAR 24

A fresh start for the African Academy of Sciences

Editorial 19 MAR 24

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Researcher in the center for in vivo imaging and therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Oxford Research Encyclopedias

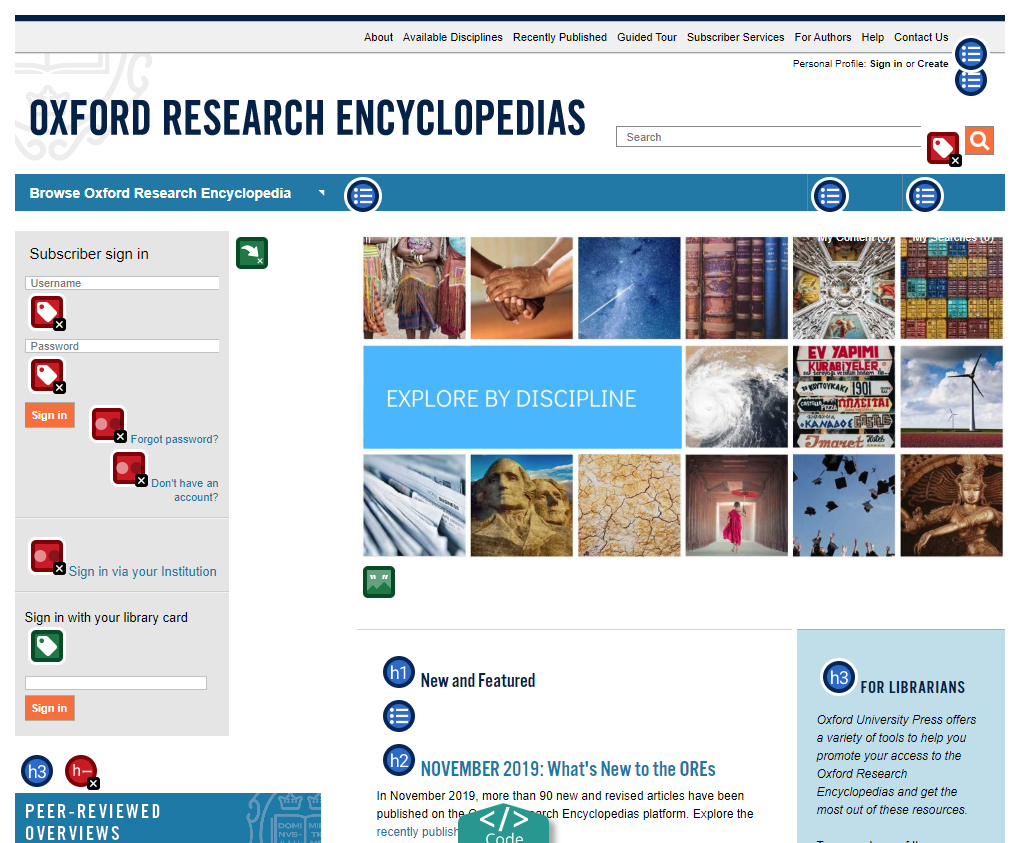

Introduction.

Oxford Research Encyclopedias offer “comprehensive collections of in-depth, peer-reviewed summaries on an ever-growing range of topics.” Entries are written by professionals in the field and represent 25 topic areas , including politics, science, literature, and more. Two formats are present: full articles & summaries. In one example, a PDF of a full article ran 30 pages in length. Another was 20 pages in length. Full articles make up a majority of the content - 14,000+ articles to date. For the latter, an entry on the same topic ran 3 pages in length. However, among a sampling of summaries (209 available at the time of this review), we found them to be generally one page in length. When they say “World-class experts give readers an overview of a subject that they can understand in half an hour of reading or less,” they are probably noting the summaries.

This content falls into the unique category of being academic without necessarily being “peer-reviewed.” The fact that this database bills itself as being “peer-reviewed” is a bit misleading, as it is not typically the type of peer review that is being requested in assignments. The depth of the articles is impressive, but the obscurity may make the topics less accessible than a typical reference entry. The reference articles provided are lengthy and appear to be of good quality.

In thinking through the kinds of research assignments we see in our community colleges, we wondered how these in-depth encyclopedia articles would help our students. In a research paper exploring a topic in a transfer level english course, a student may be required to write 8-12 pages, and may be asked to include a minimum number of sources. If said student was instructed to explore their topic in a minimum of 8 sources, would they best be served by an in-depth encyclopedia article as long as the majority of what the OREs offer? The articles are thorough, and one could get an excellent education on a topic using them, and they feel trustworthy, but the angle of the articles feel niche enough to where these might not be appealing to a large swath of our community college students (based on their common research assignments). A better use case might be if these were used as a content item by the instructor - that is, if they assign a full article for reading by the entire class on a topic.

One of the benefits of these articles is that they do provide an in-depth overview of a specific topic, but is written in a way that is accessible for first and second year undergraduate students. The language used is much more readable than a scholarly journal article.

To get a sample of the style of an entry, please see the “unlocked” items on the site (which are entries prepared for encyclopedias under development).

Navigation between subjects along the top are easy to use, and if the Research Encyclopedia exists for a subject area, it will further subdivide into narrowed topics. The Tab key on a keyboard works to open and close the “Browse” subject menu. You can easily cross-search the encyclopedias using the Search box as well. A list of search results shows the title of the entry, the author, the date, the encyclopedia the entry belongs to, and a part of the entry.

Once you are within an entry, the search box changes from a database search to a subject specific search (with radio button options to switch between options). This is an interesting feature, though it defaults to the topic the entry appeared within, and this may be confusing to students who might be used to a “OneSearch” experience.

Within an article, a user can jump between headings using links along the upper left side of the page, which may help students identify the most relevant section for their research purposes. Rather than identifying "sources" for the article, the lower section displays ideas for "Further Reading."

The search itself appears to provide irrelevant results. At best, some of the results are wildly tangential. An example of this is the search for “climate change,” which pulled up the following first three results: “Climate Change Communication,” “Celebrities and Climate Change,” and “Climate Change and Migration.” While it’s clear these are pretty off the mark for the expectation of a reference work on Climate Change, to be fair, these also sound like really interesting articles that would be difficult to get information on with a simple search of most databases. A “Climate Science” encyclopedia is offered, but science related articles did not rise to the top of the result list.

Mobile Friendly

The site was not responsive to mobile device screens. Scrolling around made it difficult to take the information in easily.

Initialization and Administration

Access to this resource is enabled through IP authentication.

Integration with Alma/Primo According to the ' Alma Community Zone Collection List ,' 25 portfolios are present for the Oxford Research Encyclopedias. We are unsure how deep the search will go in Primo.

Accessibility

WAVE Web Accessibility Homepage issues include (10 errors, 6 contrast errors, and 11 alerts):

- Missing form labels

- Empty links

- Contrast errors (color)

Article Level page issues include (14 errors, 39 contrast errors, and 31 alerts):

- Missing Fieldset and Legend

- Skipped heading level

- Suspicious Links

Readability Scores

Overall, readability scores are above first year undergraduate reading level.

“Attitudes Toward Women and the Influence of Gender on Political Decision Making” (Grade: D)

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level 13.9

Gunning Fog Index 15.2

Coleman-Liau Index 15.0

SMOG Index 16.3

Automated Readability Index 15.4

FORCAST Grade Level 12.4

Powers Sumner Kearl Grade 6.9

“Accountability in Journalism” (Grade: E)

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level 16.4

Gunning Fog Index 18.9

Coleman-Liau Index 15.5

SMOG Index 18.3

Automated Readability Index 17.4

Powers Sumner Kearl Grade 7.6

Rix Readability 13

Raygor Readability 13

The privacy policy indicates that they use some personal information with consent, but that users may email them to withdraw consent. As of November 2019, they do not sell personal information to third parties.

The following types of support are available:

Contact Us page

Individual subject collections may be subscribed to for approximately $1000. The entire package of 25 subjects is available for approximately $3500.

Competition

Recommended improvements, content providers.

- Oxford University Press

If you have any experience with this product, please leave a comment and rate its appropriateness for use in a community college environment.

† The offers and trials information are password protected. Actual prices are confidential between the vendor and the consortium.

For access contact Amy Beadle, Library Consortium Director, 916.800.2175 .

Add new comment

Advertisement

Who researches organised crime? A review of organised crime authorship trends (2004–2019)

- Published: 23 October 2021

- Volume 25 , pages 249–271, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Kevin Hosford 1 ,

- Nauman Aqil 2 ,

- James Windle ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8367-2926 1 ,

- R. V. Gundur 3 &

- Felia Allum 4

6809 Accesses

6 Citations

23 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article presents a review of organised crime authorship for all articles published in Trends in Organized Crime and Global Crime between 2004 and 2019 (N = 528 articles and 627 individual authors). The results of this review identify a field dominated by White men based in six countries, all in the Global North. Little collaboration occurs; few studies are funded, and few researchers specialise in the area. Organised crime research, however, does have a degree of variety in national origin, and therefore linguistic diversity, while the number of female researchers is growing. The article concludes that authorship trends are influenced by the challenges of data collection, funding availability, and more entrenched structural factors, which prevent some from entering into, and staying active within, the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Is drawing from the state ‘state of the art’?: a review of organised crime research data collection and analysis, 2004–2018

James Windle & Andrew Silke

Global crime science: what should we do and with whom should we do it?

Dainis Ignatans, Ludmila Aleksejeva & Ken Pease

Measuring Organised Crime: Complexities of the Quantitative and Factorial Analysis

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The organised crime field has come far since Cyrille Fijnaut ( 1989 :75) observed how the ‘very small’ academic interest in organised crime was incongruent with its growth and popular concern. Organised crime research can now be justifiably categorised as a field of study in its own right: Amazon.co.uk lists 19 organised crime textbooks and handbooks, while five peer-reviewed journals focus solely or partly on organised crime, Footnote 1 and a number of dedicated research groups, academic societies, and annual workshops exist. Footnote 2 Many undergraduate and postgraduate social science degrees offer organised crime classes; a small number of postgraduate programmes are dedicated solely to organised crime, and this number is even greater when combined with terrorism studies.

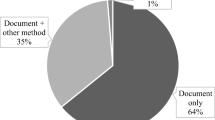

This article extends and compliments a previously published systematic review of organised crime data collection and analysis methods (Windle and Silke 2019 ). That article, which reviewed all papers published in Trends in Organized Crime and Global Crime between 2004 and 2018, identified several key weaknesses within organised crime scholarship. First, organised crime research was dominated by secondary data analysis of open-access documents. Second, there was a shortage of inferential statistical analysis. Third, there was a substantial absence of victim or offender voices with an overreliance on data from state bodies and the media; ethnographic research and victim surveys were seldom-used data collection methods. Thus, that article concluded that organised crime research appears unbalanced by an overreliance on a small number of methods and sources and recommended that rebalancing the field requires more organised crime researchers to speak to offenders and victims, engage in participant observation, and/or employ greater use of statistical analysis.

The current article explores the organised crime field further by analysing authorship in terms of published authors’ gender, race, and national origin; the national affiliation of authors’ institutions of record; whether papers were co-authored or funded (and, if so, where funding originated); and the extent to which authors specialised in organised crime research. This analysis of authorship data provides insight into the health of the organised crime field and clues to answer the critical question of why the field of study is so reliant upon a small number of methods and sources. The aim of this article is, therefore, to further assess the field of organised crime research by systematically reviewing the authorship information of articles published in the two main organised crime dedicated peer reviewed journals over a sixteen-year span (2004-2019, inclusive), a period sufficient to indicate contemporary publishing patterns and the results of efforts undertaken to diversify scholarship.

Methodology

There are two primary ways of measuring authorship trends. The first involves surveying active researchers. This method, however, is biased towards currently active researchers and misses those who conducted one study, or wrote one paper, and then changed fields. The second method, the one used here, involves extracting the authorship details of published research. This method is clearer, can generate a wider sample, and has been previously used to evaluate authorship of research into terrorism (Schuurman 2018 ; Silke 2001 ) and wildlife crime (McFann and Pires 2020 ). No comparable study of organised crime authorship exists.

Reviewing published authorship within organised crime scholarship is possible because two well-established, peer-reviewed academic journals, dedicated primarily to publishing research on organised crime, currently exist: Trends in Organized Crime and Global Crime . Footnote 3 These journals have different publishers, separate editorial teams, and largely separate editorial boards. While much organised crime research is published outside these two journals, taken together, they provide a reasonably balanced impression of authorship trends in organised crime over the period reviewed (2004-2019).

We extracted authorship data from every article and research note published in the print issues of the two journals for this period (N = 528). These included introductions to special issues and book review essays but excluded errata, book reviews, and extracts from official reports. We included book review essays and introductions to special issues because these articles tend to provide new knowledge, are often cited by other authors, and tend to be written by those with an interest in the organised crime field.

The following data were recorded for each article: authors’ names, gender, ethnicity, and national origin; the number of authors contributing to the article and individual author’s placement; authors’ institution and the institution’s country; and funding sources.

While most authorship information was extracted from the published articles, to assess gender and race, we conducted a web-based search for images and words indicating gender and race. We searched authors’ institutional profiles, online CVs, public social media accounts, academic database profiles (i.e. ResearchGate, Academia.edu), and other online material (i.e. press releases and media presentations). This method has been used in previous research (Chesney-Lind and Chagnon 2016 ). We also identified the colleagues we personally knew; the field of organised crime is relatively small and our roles in international organisations have led us to meet several of the people in our database. We searched for, but did not identify, any non-cis-gendered pronouns used in reference to the authors in our database. One article was authored by an organisation.

To assess national origin, we followed a procedure similar to that used for gender and race. If we did not personally know a colleague’s national origin, we searched open-source information to identify the undergraduate institution that the author attended. Undergraduate university is a good proxy for national origin as, based on our experience as educators, the overwhelming majority of students undertake their undergraduate studies in the same country where they were raised as children.

Limitations

Organised crime is a large and diverse field. Many influential studies on organised crime have been published in academic journals, edited volumes, monographs, and research reports outside the two journals reviewed in this study; many have been published in languages other than English. These two journals, however, represent a good sample of those working within the field. Few researchers with a significant interest in organised crime were missing from our database, suggesting that most publish in one or both of these journals at some point in their careers. Furthermore, trying to identify and review the authorship information of organised crime research published in books, reports, and across all social science journals is an unmanageable task without significant funding. It would also involve a degree of subjectivity in choosing what can be categorised as organised crime research. Here, the parameters of organised crime research have been set by the two journals’ editors and peer reviewers. Footnote 4

This article assesses current trends in authorship but does not measure the impact of any author, which can be measured through citation counts (Iratzoqui et al. 2019 ; Silke and Schmidt-Petersen 2017 ) or mentions in textbooks (Miller et al. 2000 ). We were also unable, in this review, to account for the authors’ socioeconomic backgrounds. This limitation is important as recent research has shown that working-class scholars continue to be underrepresented and feel excluded in the academy (Ardoin and Martinez 2019 ; Bhopal, 2019).

Our technique for coding authors’ gender, as either male or female, may present errors in our analysis. Names and pronouns can be misleading and assessing non-cisgender representations can be difficult. Similarly, judging authors’ ethnicity is imperfect as racial identification of indigenous and mixed-race people and people who have changed their names for whatever reason is subjective (Nagel 1994 ; Tafoya 2002 ). Furthermore, our categories of ethnicity are somewhat blunt. Different countries have different ethnic categories and often include sub-categories, such as Black-Caribbean or Mincéirí (Irish Traveller), which cannot be identified using this method.

Internet searches are problematic. Not all our sampled authors had institutional profiles or an online presence; we were unable to find the race of 6% (N = 51) of our sample and the national origin of 4.1% (N = 35). Nonetheless, as Meda Chesney-Lind and Nicholas Chagnon ( 2016 :329) observed in their own review of criminology authorship: ‘these are the data that exist, and we must work with them. The concurrence between our findings and previous studies suggests that any error in our sampling does not reach the degree that it threatens validity’.

Research is an iterative process. Further research in organised crime authorship is needed, this could use a wider sample and/or different methods and data sources. The current research, for example, could be extended by widening the inclusion criteria to identify research published in other outlets, including non-English language outlets. While a significant undertaking, such a study could uncover trends different to those found in the present study; it may, for instance, find that much funded research is published in higher impact journals. Another extension could involve interviewing active organised crime researchers. Such a study could collect demographic data while assessing some of the findings of the current article and further exploring choices researchers made regarding data collection and analysis methods, place of publication and funding capture.

Funding sources and impacts on career development

Jay Albanese ( 2021 :433) responded to Windle and Silke’s ( 2019 :410) finding that ‘secondary analysis of open-access documents has overwhelmingly dominated the field’ by noting that:

The reason for this situation, of course, is the lack of available funding in most locations around the world (including the US) to support original data collection on organized crime. This leaves researchers in the position of carrying-out small-scale empirical studies, or attempting larger studies based on existing data, usually using government sources for data.

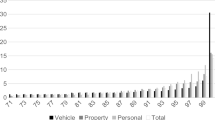

Indeed, whether research is realised is often, though not always, dependent on financial support. Despite organised crime’s popularity in political and popular discourse, research funding is scarce. Only 17% (N = 90) of papers reviewed declared a funding source. Of these, 17.5% (N = 16) were funded by third sector organisations (i.e. Ford Foundation), 23% (N = 21) by government agencies (i.e. US Department of Justice), 26.3% (N = 24) by universities, and 49.4% (N = 45) by government and inter-governmental research councils (i.e. European Union FP7, UK ESRC). That is, a quarter of all funding came directly from government sources, rising to just under 72% if we include state-funded research councils. The percentage of funding coming directly from government agencies is not insignificant but may be less than expected of a field directly relevant to public policy and political discourse.

Nonetheless, organised crime research may be more influenced by policy concerns and the agendas of government bodies than some other academic fields. This is partly due to funding but also because organised crime researchers rely heavily on state agencies as data sources (Windle and Silke 2019 ; Albanese 2021 ). As in all fields, researchers sit on a spectrum from those who view themselves as (more or less) objective observers at one end to openly biased political actors at the other end (see Becker and Horowitz 1972 ). This spectrum can be further complicated by those who see themselves as an extension of the coercive arms of the state and thus conduct research to assist the police or military to define or counter some perceived or real threat (Silke 2001 ).

Ideally, funding should aid researchers to objectively produce data and critical analyses, which support informed policies and improve professional practice. While collaborative ventures between researchers and practitioners can ensure the research has real world impact, many government agencies are selective in the evidence they solicit and employ (see Stevens 2011 ) and in the researchers they fund. That is, funding bodies and gatekeepers may prioritise scholars with whom they have existing relationships, or those recommended by established scholars. Consequently, early-career researchers, yet to establish their name in the field, or researchers who have been overtly critical of government actors or policies may find it difficult to access government-sponsored funding or data.

Another concern is the role governments play in determining research priorities. As ‘government agendas rarely if ever stretch beyond the next election’, government-funded research can be ‘driven by similarly short-term tactical considerations’ (Silke 2001 :2). Consequently, politically hot topics can receive a disproportionate share of government funding while pressure to conform to state agendas can produce an environment where a ‘considerable share of research and academic writing obediently follows the beaten track of popular imaginary and official parlance’ (Von Lampe 2002 :192). As a result, researchers who want government funding and data may need to engage in research that governments prioritise and propose. Government funded research can also be subject to publication embargoes. Both of these parameters may limit the reach of criticisms of government or government programmes, should they emerge (Jupp 2002 ). Accordingly, research objectivity may be weakened when heavily dependent on funding from government agencies (see Cressey 1967 ; Jupp 2002 ; Von Lampe 2002 ; Silke 2001 ).

The influence of funders on the research will vary between countries and organisations, and even between particular projects. However, those sponsoring the research undoubtedly ‘influence the everyday practice of research – how data are collected and from whom’ (Jupp 2002 :135, emphasis added). Thus, while policy, practice, and public discussions should be informed by good social science, objectivity and/or independence may be compromised when the state sets the agenda and conceptual boundaries, provides the data, and is the only funding option available.

That a quarter of all funding for organised crime research projects comes directly from government agencies indicates a significant reliance. Nevertheless, not all state-funded research lacks objectivity and researchers need not avoid state funding or collaboration with state bodies. The authors have collectively used official data in their research, collaborated with state practitioners, and received funding from state bodies. These relationships were seldom inherently problematic and provided platforms to influence policy and practice. Indeed, projects such as the Dutch Organised Crime Monitor (Kleemans and Van de Bunt 2008 ) and the Australian Institute of Criminology’s programme of grant funding for projects proposed by academics reflect the benefits of mutual collaborations between academia and state bodies.

This situation does, however, present a double-bind: while the field needs funding to attract and maintain researchers and to allow individual researchers to collect primary data, the field may be weakened if it becomes overly reliant on both funding and data from state agencies, thereby limiting its capacity to present counterfactual analysis and arguments. These realities may contribute to a lack of specialist organised crime researchers.

Specialists or toe dippers?

A key problem with organised crime research is that too few scholars stay in the field (Von Lampe 2016 :54). Many publish one article and then move into another field or publish an organised crime paper as part of a wider project. This lack of specialisation reduces opportunities for collaboration among researchers, restricts discussions around developing common conceptual and data collection frameworks, and prevents the development of relationships between researchers and data-holders (whether cops or crooks). Building these relationships, and gaining access to otherwise restricted data, can take many years and ‘few [researchers] have the resources and patience to be that persistent’ (Von Lampe 2016 :54). Of the 627 individual researchers identified as having published at least once in the two journals: 83% (N = 521) published only once, 9.6% (N = 60) published twice, and only 7% (N = 44) published three times or more across both journals.

Dennis Kenney and James Finckenauer ( 1995 ) and Klaus von Lampe ( 2016 ) suggest that the lack of organised crime specialists is largely due to the scarcity of funding for organised crime research. They may be right: Only 17% (N = 90) of papers declared a funding source. Scholars who are ambitious or looking to escape precarious employment may drift away from fields which do not attract the funding necessary to climb the career ladder or attain tenure. The lack of funding may also mean that teams of researchers find it difficult to fund their efforts and instead focus on projects that are more able to underwrite collaboration and efficient publication (see Fahmy and Young 2017 ).

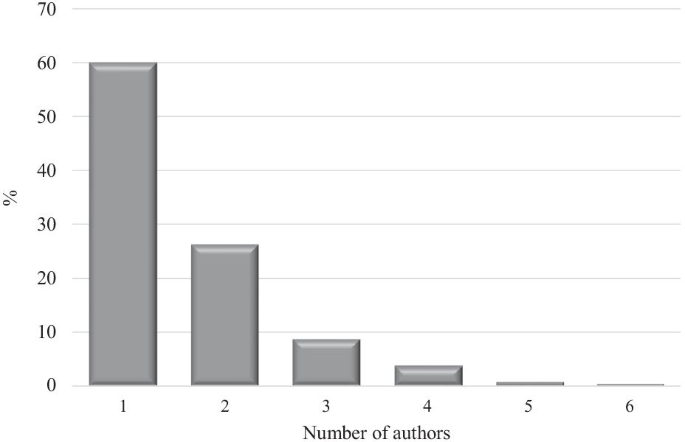

Partnerships

Several studies have generated unique insights by merging or comparing otherwise distinct theoretical perspectives (i.e. Cloward and Ohlin 1961 ), cases, or datasets (i.e. Hall et al. 2017 ; Lavorgna et al. 2013 ; Spicer et al. 2019 ), or by analysing existing data in new ways (i.e. Levitt and Venkatesh 2000 ). Collaborative papers, particularly those with interdisciplinary authors, can provide new insights and knowledge that would be missed by a single author; improve research quality, validity and integrity through shared oversight and combined expertise (Lemke et al. 2015 ); and facilitate comparative research (see Barberet and Ellis 2013 ). While co-authorship has been identified as the ‘dominant form of scholarship’ within criminology (Fahmy and Young 2017 ), organised crime research is largely an individual endeavour with 60% (N = 317) of the published work in the field being single authored; 26.3% (N = 139) having two authors; 8.7% (N = 46) having three, and only 4.9% (N = 26) of papers having four or more authors (Fig. 1 ).

Percentage breakdown of articles by authorship, 2004-2019

With only 17% (N = 90) of the papers included in this review being funded, we can assume that few authors were supported with research assistance. Accordingly, most research papers on organised crime are written by lone authors who likely design the research instruments, write the ethics applications, and collect and analyse the data. Consequently, at a basic level, the workload of one individual working on a research project is heavier than the workload of a group working as a team.

Working alone limits the ‘size and scope of the projects that can be undertaken’ (Schuurman 2018 :11). Less time and funding may indicate that individuals cannot undertake more time-consuming data collection methods, often favoured by reviewers of prestigious journals, such as interviewing to saturation, conducting extensive archival searches, or running complex statistical analyses of existing data. Moreover, working alone reduces the amount of expertise available to conduct the analysis, which may partly explain the lack of statistical analysis within organised crime research (see Windle and Silke 2019 ). Engaging in more complex statistical analysis requires significant training and expertise in statistics programmes (Silke 2001 ).

The dominance of solo work in organised crime research may offer some insights into the methodological choices of organised crime researchers: Less than 9.5% (N = 44) of organised crime articles reviewed by Windle and Silke ( 2019 ) interviewed offenders while 17.9% (N = 83) interviewed state officials. Not only is it easier to identify and recruit state officials as participants, but it can be difficult for lone researchers to devote time to interviewing large numbers of offenders, especially if researchers have teaching and administrative responsibilities. Even when operating quickly, researchers need to be able to develop relationships with the places and communities that they are researching (Gundur 2019 ; Zhang and Chin 2002 ). While some researchers have conducted studies in relatively short timeframes with high response rates (see Gundur 2019 , 2020 ; Mitchell et al. 2018 ), others note that interviewing active offenders can be frustrating, time consuming, and tenuous. Adam Baird ( 2018 :346), for example, reports that, in his ethnography of gangs in Colombia, participants:

Regularly turned up late to arranged meeting places, any evening encounters meant they were likely to be drunk or high, and on numerous occasions they did not appear at all. The challenges of finding gang members and the high interview failure rate meant I felt constant ‘data anxiety’.

Similar ‘data anxieties’ may arise when researchers try to secure access to incarcerated offenders or to restricted documents, such as court or police records. Even when dealing with projects sponsored by government agencies, researchers can find the bureaucratic system slow moving (see Decker and Chapman 2008 ; Mitchell et al. 2018 ).

No systematic analysis of gender differentials in organised crime scholarship exists. Such analysis, however, has been conducted in comparable fields. For example, criminology has been accused of being androcentric: most papers are written by men about men (Miller et al. 2000 ; see Peterson 2018 ). Lorine Hughes’ ( 2005 :1) content analysis of leading British and American criminology journals between 1895 and 1997 found a ‘severe and long-term underrepresentation of women in criminological research’, with men outnumbering women by four to one as lead authors (also Miller et al. 2000 ).

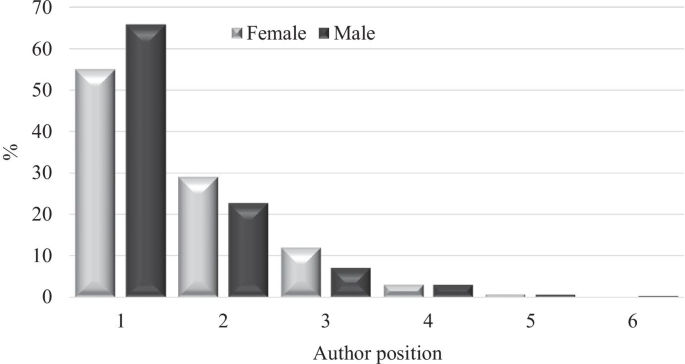

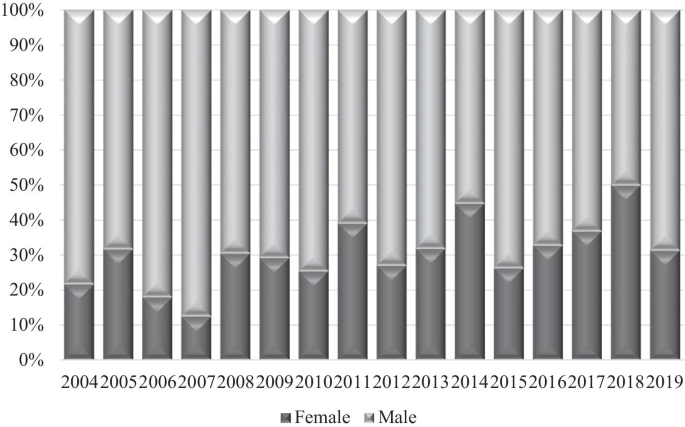

The lack of gender balance in organised crime authorship is disheartening for several reasons. First, only 30% (N = 258) of the 846 contributors Footnote 5 are women. Second, only eight of the 44 (18.18%) authors who published three times or more are women, rising to 26 of 103 (25.2%) authors who published two times or more, suggesting that somewhat fewer women than men stay within the field. A marked disparity also exists between the position of men and women in authorship: 65.8% (N = 387) of the 588 male contributors were either single or first author, against 55% (N = 142) of the 258 female contributors. Women are more commonly second, third, fourth, or fifth author than men (Fig. 2 ).

Author position of male and female authors of organised crime research, 2004-2019 (as percentage of male/female contributors)

Nonetheless, Fig. 3 demonstrates an uneven but clear increase in the number of female authors over the time period under review. The percentage of female authors of articles published each year increased from 21.7% (N = 5) in 2004 to 36.9% (N = 24) in 2017, with a high of 50% (N = 43) in 2018.

Percentage of male and female authors per year, 2004-2019

The problem of overrepresentation of male authors is clear from the wider criminological literature. Feminist criminologists have long argued that the discipline’s narrow focus on male offending and a general tendency to adopt a gender-neutral approach have produced explanations of male offending that were then applied to women (Daly and Chesney-Lind 1988 ). Many have contended that the underrepresentation of women as research subjects partly results from the overrepresentation of men within academia (Joe and Chesney-Lind 1995 ). For example, Hughes’ ( 2005 :13) content analysis of leading criminological journals found that ‘research articles having a female first author were significantly more likely than research articles having a male first author to focus on females’, and that the increase in female researchers resulted in ‘issue of female crime’ becoming ‘more appropriately addressed’ (Hughes 2005 :3). Researchers’ lack of interest, perhaps, reflects society’s general lack of interest in issues specific to women.

The number of female authors is influenced by wider structural factors. Lowe and Fagan ( 2019 :429) suggest that the gendered division of household and family labour influences ‘the amount of time women can devote to their careers’, and that many ‘seek academic positions that place less emphasis on time-consuming research activities’, such as teaching (also Chesney-Lind and Chagnon 2016 ; Fahmy and Young 2017 ). Family and household commitments can make it difficult for women to travel to conduct fieldwork, visit archives, or promote research at conferences. Moreover, being the primary caregiver can influence decisions around engaging with potentially risky participants in risky situations. These assumptions should be investigated further. Fewer women researching organised crime reduces the chance that women will be research subjects and can result in a field dominated by male-centric theories.

This trend, however, appears to be shifting towards greater gender parity (Lowe and Fagan 2019 ) with just under half of the American Association of Criminology members being women (Rasche, 2014, cited in Lowe and Fagan 2019 ). Nonetheless, women remain overrepresented in precarious employment (O'Keefe and Courtois 2019 ), and underrepresented in senior academic posts and amongst academic editorial positions (Fahmy and Young 2017 ; Lowe and Fagan 2019 ). The data presented here show an increase in female organised crime authors which, coupled with our observations of conference panels, may suggest that parity is a near-term possibility.

As the number of female organised crime researchers has increased, so too has the realisation that the role of women in organised crime has been a significant blind spot within the literature (Arsovska and Allum 2014 ; Beare 2010 ; Selmini 2020 ; Siegel 2014 ). Footnote 6 New studies undertaken by female researchers have, for example, identified a ‘gender gap’ in the roles and activities men and women assume in organised crime and illicit enterprise. Valeria Pizzini-Gambetta ( 2014 ) has shown that, while women have been excluded from mafia-type organisations, they have played a significant role in illicit enterprises (see chapters in Fiandaca 2007 ). Thus, a greater number of studies on the role of women in illicit enterprises than mafia-type organisations exist, including: Chris Smith’s (2019) account of the role of women in Chicago’s organised crime during Prohibition, and Elaine Carey’s ( 2014 ) and Jennifer Fleetwood’s (2014) respective research on female drug traffickers and couriers.

Race, nationality, and national origin

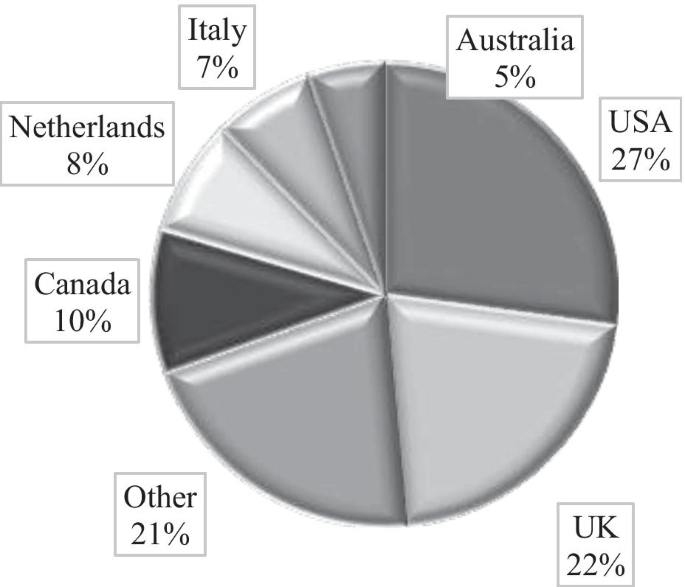

The majority of organised crime research is conducted within institutions based in the Global North, where access to resources, data, and research opportunities exist, and where criminology or similar programs are already established. Footnote 7 Of the 846 author contributions, 78.9% (N = 669) were based in institutions located in six Global North countries (Fig. 4 ): the US, the UK, Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, and Australia. Authors based in the UK and the US account for 48.5% (N = 411) of all papers published in the two journals, whereas combined Latin American, Asian and African contributions account for 6.4% (N = 55) of papers published between 2004 and 2019.

Geographical location of author institution, 2004-2019

The Global North, as the dominant locus for knowledge production, promotes its research priorities, traditions, and cultures through its published research in organised crime. Sharon Pickering et al. ( 2016 :158) have argued that research findings published for the English-speaking academy often ‘pertain to Northern empirical realities’, which contributes to ‘inequalities of academic knowledge production’. Moreover, while many social theories dominant in the Global North may be unsuitable for countries in the Global South, or even countries outside the United States, these theories are often used to explain phenomena in the Global South (Aas 2012 ; Ciocchini and Greener 2021 ). Indeed, research conducted on the Global South by outsiders is largely geared towards a narrow focus on rhetoric and policy transfer (Gheciu, 2012; Tankebe et al. 2014 ). When researchers refuse or are unable to engage with non-English language sources, both in terms of data collection and publication, and when reviewers who serve as gatekeepers to publication come from largely Global North Anglophone traditions (see Lillis et al. 2010 ), then marginalized voices in the academy are further silenced or erased.

Scholars in the Global South and in countries in the Global North outside the big six (US, UK, Canada, Italy, Netherlands, Australia) may face several obstacles to conducting research and producing publications. Geographical location (Fig. 4 ) appears to reflect data access and collection opportunities. Since government agencies are the most common data source for organised crime research (Windle and Silke 2019 ), the field is dominated by researchers based in countries with established organised crime monitoring systems. Researchers who do not have the time or resources to collect primary data can be limited to the state as a source of information. As such, conducting research in countries with inconsistently produced or unavailable state data is problematic and limits the development of a tradition of organised crime research.

Furthermore, in many countries, the tradition of researching or teaching organised crime is minimal or non-existent. Scholarship on organised crime may be unfamiliar even among researchers, policymakers, and practitioners. Moreover, these countries may lack domestic funding opportunities or the ability to access funding from wealthier countries. Problems of obtaining consent and alleviating concerns about confidentiality and anonymity can be pronounced in some countries while access to research participants can be problematic. For instance, in countries such as Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, which are important to organised crime and transnational illicit markets, male researchers may find accessing female subjects in gender segregated societies difficult. Likewise, female researchers may find accessing gatekeepers in highly patriarchal societies difficult, but not impossible (for example Felbab-Brown 2014 ; Michelutti et al. 2018 ).

Even when studies are completed, authors with English as a second language face difficulties in publishing their results in English-language, peer-reviewed journals. Footnote 8 Apart from linguistic facility, other factors, such as a lack of an internal peer-review culture, that can identify issues that trigger a rejection, or a prioritization to have a piece published, regardless of the outlet, can result in the submission of work to ‘predatory’ journals or to journals that publish articles in their native language. Footnote 9 Consequently, there exists a dearth of peer-reviewed, published material that focuses on many non-English-speaking places that have significant organised crime activities, while work that appears in dubious outlets or not in English are often ignored by Western scholars.

When scholars from the Global South do emerge, the lack of job security and research funding at home can result in talented researchers migrating for work and failing to return, which further sustains the above problems. Footnote 10 While just over 6% of contributors were based in Africa, South America, or Asia, 12% of contributors were nationals of these continents.

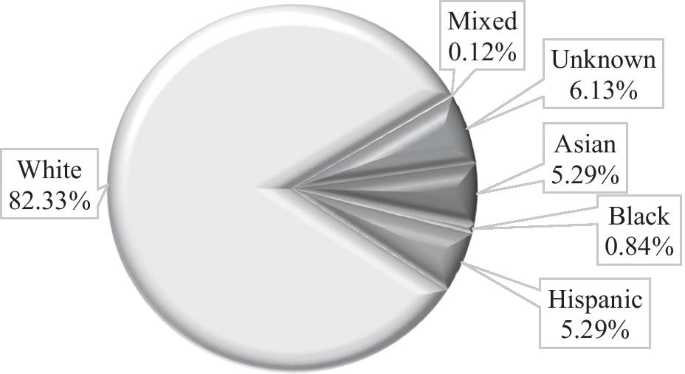

Within our sample, White people produced the majority of research on organised crime, accounting for 82.3% (N = 743) of all contributors; Asians and Latinos together made up just over 5% (N = 44), while less than 1% (N = 7) were Black (Fig. 5 ). Our analysis shows that domestic minorities in the Global North account for a very small proportion of the organised crime research output. This lack of diversity leads to both a lack of discussion of issues relevant to minority populations and framings of minority populations studied that do not appropriately consider the viewpoints of the communities involved (see Lynch et al. 2021 ).

Ethnicity of authors in organised crime research, 2004-2019

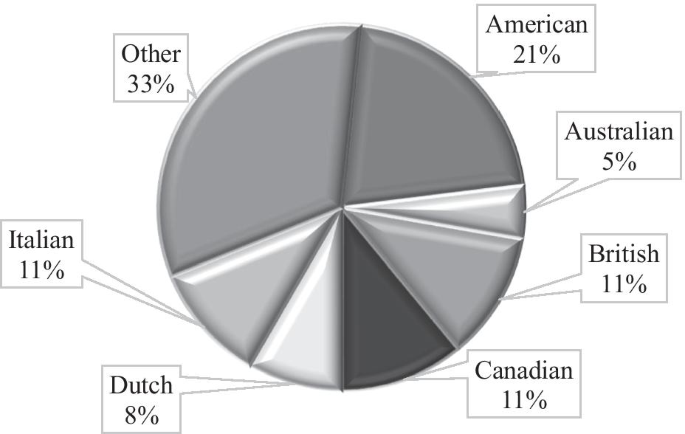

The picture is not, however, straightforward. Much of the existing analysis on criminological authorship trends focuses on minorities without regards to their national origin (i.e. Chesney-Lind and Chagnon 2016 ). Figure 6 shows, for example, that while most organised crime authors are nationals of the big six countries, 33% (N = 265) are nationals of other countries, while the range of nationalities is broad with 16% (N = 131) of contributors being nationals of countries in the Global South and 37% (N = 304) being nationals of non-English-speaking countries.

Nationality of authors in organised crime research, 2004-2019

Discussion: The benefits of diverse authorship

Our analysis acknowledges that the academy has both insiders and outsiders. Academy insiders are predominantly cis-gendered, male, White, and domestic (rather than foreign in terms of nationality). Our data speaks to these attributes in four ways. First, people at institutions in six countries located in the Global North produce most of the research published in English. Second, ethnic minorities are underrepresented, as is the case in mainstream criminology. Third, despite improvements, women remain underrepresented. Fourth, there is much diversity in national and linguistic origin, which indicates that a sizeable proportion of organised crime researchers are likely to be outsiders in their departments.

The field has much to gain from supporting minority researchers and researchers working in countries outside the big six. Much organised crime is transnational: for example, heroin begins in the poppy fields of Afghanistan and is trafficked overland through various countries, before being consumed in say London (see Windle 2016 ). Dick Hobbs ( 1998 ), however, reminds us that the transnational picture only fully emerges when we understand the local. Since transnational networks are formed of local nodes, understanding local contexts is important. Thus, a deeper understanding of transnational heroin distribution requires an understanding of Afghan opium farming, the dynamics of South Asian trafficking networks, and user-dealers in London.

Although researchers do not have to be natives, they need to immerse themselves in the native culture and underworld subcultures to succeed. Sharon Kwok ( 2019 ) has shown how cultural understanding and insider information were invaluable not only in negotiating entry into Triad society but also in protecting the researcher against potential dangers (also Baird 2018 , in Colombia). Kwok ( 2019 :13) argues that the inherent difficulties of access have limited ethnographic research on Triads, forcing most research to rely on third party information, which presents a ‘skewed picture’ (also Windle and Silke 2019 ). Qualitative organised crime research often relies on personal contacts: Two notable examples include Hobbs’ ( 2013 ) research on organised crime in East London, Robert McLean and James Densley ( 2020 ) work on Glasgow gangs, and Sheldon Zhang and Ko-lin Chin ( 2002 ) work on human smugglers in China. These studies would have been difficult to complete without personal contacts and contextual and cultural understandings of the communities where these groups operated (see chapters in Lynch et al. 2021 ). These issues can also present when interviewing state officials or accessing restricted official data. In short, being known to, or having pre-existing relationships with, practitioners can both facilitate access to data and provide the contextual understanding that supports deeper analysis (for example Kleemans and Van de Bunt 2008 ; Mitchell et al. 2018 ).

The social location of the researcher (i.e. class, gender, race, ethnicity, national origin/ residency status) can also influence data access and collection. For instance, data access can be influenced by how the researcher performs ‘gendered social practices’ (Krause 2021 :335): ‘becoming one of the boys’ may facilitate discussions about violence while closing off more sensitive areas, such as past trauma (Baird 2020 ). Access to government data may also be restricted to citizens or permanent residents of that government’s country. In addition, intersectionality of these disadvantageous social characteristics compounds the challenges associated with negotiating access. Positionality, therefore, is not only relevant for ethnographic studies with offenders but can also influence access to official data and interviews with practitioners.

Von Lampe ( 2002 :192) has argued that organised crime, as a field of study, would benefit from greater international cooperation, especially partnerships involving countries which do not have a ‘traditional organised crime problem’. International cooperation can be productive for several reasons. First, such cooperation can support much needed comparative research, ‘which in turn promises deeper insights than research conducted within regional or national contexts’ alone (Von Lampe 2002 :192). Second, international cooperation can help researchers obtain and analyse otherwise unavailable foreign data. Many countries fail to systematically collect data on organised crime and illicit markets, and, even when they do, accessing foreign official data can be difficult for researchers based in other countries (Finckenauer and Chin 2006 ). Assessing official documents for authenticity, credibility, and meaning, or identifying distortions can be equally difficult (Windle 2016 ; Windle and Silke 2019 ), especially when those documents are written in foreign languages. Third, organised crime research conducted in other countries can offer opportunities to test, validate, and challenge theories of organised crime in other contexts (see Aas 2012 ) and may ‘give rise to concepts and models which are better adapted to society than cliché-ridden conceptions of Mafia’ (Von Lampe 2002 :192). For example, Lucia Michelutti et al. ( 2018 ) recently constructed a new theory, drawing from Western anthropological theories and ethnographic data, to explain the interplay between organised crime and politics in South Asia.

While the academy has been working towards gender equality, with initiatives such as Athena SWAN in the UK, nothing similar exists to improve access for ethnic minorities or people from working-class backgrounds. While more women are in the academy compared to twenty years ago, they are overwhelmingly White and from middle- and upper-class backgrounds (Bhopal 2015 ). Plus upward movement through the ranks of academia is still limited for women compared to men (Baker 2010 ; O'Keefe and Courtois 2019 ). Although research on mainstream criminology authorship trends indicates that minorities are severely underrepresented in publishing trends (Chesney-Lind and Chagnon 2016 ; Del Carmen and Bing 2000 ; Fahmy and Young 2017 ), there are no studies which estimate social class as a marker for publication output.

This article reviewed 528 articles published in Trends in Organised Crime and Global Crime , between 2004 and 2019, to explore trends in organised crime scholarship. While the two journals represent a good sample of those working within the field, it is acknowledged that excluding research published in other outlets limits capacity to generalise. With this limitation in mind, the results of this review portray a field dominated by White men from the UK and the US engaged in individual research with minimal funding. Nonetheless, compared to mainstream criminology, organised crime research exhibits a significant degree of diversity in national origin, and therefore linguistic diversity, and a growing number of female researchers. Nevertheless, few scholars specialise in the area for various reasons.

Organised crime is not an easy field to study. Almost 50 years ago, Donald Cressey ( 1967 :101) noted that research endeavours can be frustrated by:

The secrecy of participants, the confidentiality of materials collected by investigative agencies, and the filters or screens on the perceptive apparatus of informants and investigators pose serious methodological problems for the social scientist who would change the state of knowledge about organized crime.

Organised crime scholars continue to face these challenges. Furthermore, depending on the methods used, empirical research on organised crime can be resource and time intensive, potentially risky, and fraught with ethical challenges (see Baird 2018 , 2020 ; Gundur 2022 ; Hobbs 2000 ; Krause 2021 ; Von Lampe 2016 ; Windle and Silke 2019 ). Researchers may find it difficult to convince risk-adverse university research ethics committees that the research will not harm the researcher, participants, or university’s reputation. These risks range from negligible to significant, depending on the context of the research site and the researcher’s skill and experience.

Serious violence against researchers is rare but has happened. Louise Shelley ( 1999 ) recalled three cases of intimidation against scholars: In Israel, Menachem Amir was threatened by a group he had studied; in Russia, Olga Kristanovskaya was threatened after publishing her research on the banking sector; and in Italy, Pino Arlacchi was issued a death threat by Cosa Nostra. William Chambliss can be added to the list: he was threatened with lawsuits and violence (Inderbitzin and Boyd 2010 ) and subjected to blackmail attempts in a bid to silence his findings into the link between politics and crime in Seattle (Chambliss 1978 ). We could only think of three researchers who had been murdered, two of whom were murdered for their political lobbying rather than their research enquiries: Ken Pryce in Jamaica, Esmond Bradley Martin in Kenya, and Dian Fossey in Rwanda. Notably, almost all of those threatened or killed were engaged in research into organised criminals and illicit entrepreneurs with links to state and political actors, while Arlacchi is a public intellectual and politician. In countries where little organised crime research occurs, violence against journalists covering organised crime stories may offer a good proxy of the potential threat researchers could face.

Additional gendered risks exist. Many researchers interviewed by Rebecca Hanson and Patricia Richards ( 2017 ) had experienced sexual harassment and intimidation during fieldwork. These experiences were often delegitimised and silenced by three widely held ‘fixations’: research should be solitary; experiencing danger in the quest for data glorifies the research, and ethnography requires intimacy with participants. Hanson and Richards concluded that the dominance of White males in academia makes it difficult for both women and men to report sexual harassment (also Krause 2021 ).

Researchers must be cautious. Indeed, one of the current authors was advised by a knowledgeable contact not to pursue a research topic in the town where he was based because a particular family would ‘blow your head off’. Another of the current authors was chased by an armed man during fieldwork. The presence of the author in their neighbourhood for extended time somehow convinced gang members that he was a government agent on a reconnaissance mission. While no academic paper is worth the risk of being harassed, beaten, or shot, Hanson and Richards ( 2017 :596) note that academia often idealises ‘researchers who are courageous’, and young researchers are often encouraged to ‘stay at field sites where they felt uncomfortable or endangered’.

Nevertheless, researching organised crime is possible. Von Lampe ( 2016 :50) has argued that previous research endeavours demonstrate that ‘there are no insurmountable obstacles’ to organised crime research. Chambliss ( 1975 :39) noted that, based on his own ethnographic research experience, data on organised crime is ‘more available than we usually think. All we really have to do is get out of our offices and onto the streets’. Gundur ( 2019 ) showed that people associated with the drug trade can be enticed to come off the streets into our offices to share their stories. Many researchers have interviewed active offenders (see Hobbs and Antonopoulos 2013 ; Windle and Silke 2019 ) and/or travelled to high-risk countries to conduct interviews or observations (i.e. Baird 2018 ; Durán-Martínez 2017 ; Felbab-Brown 2014 ). The authors of this article have together interviewed a range of drug dealers, gang members, and former-mafiosi (i.e. Allum 2006 , 2016 ; Gundur 2019 , 2020 , 2022 ; Windle and Briggs 2015 ).

Such research does, however, often need more patience, planning, foresight, and social capital than enquiries into more mainstream criminal activity (see Baird 2018 ; Durán-Martínez 2017 ; Felbab-Brown 2014 ; Hobbs 2000 ; Michelutti et al. 2018 ; Von Lampe 2012 ). Therein may be the core of the problem: collecting primary qualitative data on organised crime often requires resources and time that many researchers do not possess, unless they have funding, have developed contacts which can facilitate access to data, or live in settings that are amenable to research that is of international interest. Simply put, funding is difficult to come by and developing contacts takes time.

Organised crime enjoys much public interest and has been the basis of hundreds of television shows, books, and films. Yet, organised crime lacks consistent researchers, perhaps due to a lack of funding opportunities, the difficulties of data collection, and/or a snobbishness about not researching ‘hot topics’ or topics which are seen as populist because of their portrayal in popular culture. Moreover, starting a family, relocating for employment, or other career interruptions may move researchers away from the field because they perceive the risks and difficulties as too challenging and insufficiently rewarding. This concern may be especially so for qualitative researchers who can potentially find themselves in precarious situations while collecting data from observations or interviews. This pattern of avoiding risky situations is understandable and somewhat reflects life-course trajectories out of offending (i.e. Sampson and Laub 2003 ). The potential reasons for exiting organised crime research should be explored further through surveys or interviews with those who have left the field.

As very few studies of organised crime are collaborative, planning, research design, ethics applications, data collection, analysis, and writing are done by one person. Such an undertaking places ‘a relatively heavy burden on the researcher’ (Silke 2001 :12), especially when academics are expected to publish regularly. Frequency of publication is one of the primary methods of assessing academic productivity (Iratzoqui et al. 2019 ) and is linked to securing jobs, permanency, or promotion; moreover, it can influence the capture of research funding grants and impacts teaching allocation in some institutions. As institutional research outputs are increasingly linked to national and international league tables and impact evaluations, like the UK’s REF or Australia’s ERA, a lack of publications can impact department funding, student numbers, and status within the university and scientific community. More collaborative work could make the lives of organised crime researchers easier and result in more publications and funding, which may, in turn, motivate more young scholars to stay in the field. Collaboration can also potentially make fieldwork safer (Hanson and Richards 2017 ). Above all, collaboration can be intellectually satisfying, fun, and produce creative and innovative research.

A previous article, by one of the current authors, called for variety and innovation in data collection and analysis (Windle and Silke 2019 ). The current article calls for variety and innovation in partnerships. As organised crime and illicit enterprise in the Global North and South become more interconnected, notably with the increasing sophistication of cyberspace technologies (see Levi et al. 2016 ; Nguyen and Luong 2020 ), it is ever more important for researchers in the Global North to work with their counterparts in the Global South. Such collaboration should invigorate the health of the field globally, nationally, and locally.

The dangers of having a relatively homogeneous group of researchers – mostly White men working in US or British institutions – is that they can share common values, life experiences, perceptions, research objectives, and unintentional biases. Widening the field to include more international researchers, women, and those who are not White may invigorate the field with a greater diversity of life-experiences, perspectives, and interests, and allow researchers to consider different theories, employ different methods, and access different research participants and secondary data. Attracting scholars to the field may be the easy part; keeping them active may be the more substantial challenge.

Some of the issues raised in this article are within researchers’ control. Researchers can collaborate more, apply for more funding bids, organise workshops with colleagues in other countries, and help women and minorities enter into, and stay active within, the field. Other issues remain largely outside researchers’ control. Funding capture, to some extent, hinges on what funding bodies deem important and fluctuates with government agendas and security concerns. Many countries do not have the resources, or political will, to support organised crime research, and/or lack a tradition of studying the field. Finally, the neo-liberal university places increasing burdens on researchers – particularly women and people of colour, a situation which became even more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic (Viglione 2020 ). While patriarchal structures are slowly changing, many female researchers are still constrained by unequal family and household labour. Minorities still struggle to access the academy generally. These realities are all reflected in organised crime authorship trends.

Nevertheless, with 16% (N = 131) of authors coming from the Global South and 49.9% (N = 404) of authors coming from a country that does not have English as an official language, organised crime authorship trends are more diverse than mainstream criminology. While this diversity makes organised crime research richer than it may appear at first glance, significant work remains to continue the empowerment of the voices that struggle to access research and publication opportunities.

Trends in Organized Crime; Global Crime; Crime, Law and Social Change; European Review of Organised Crime; and the Journal of Illicit Economies .

Including, inter alia: The Cross-Border Crime Colloquium; the ECPR Standing Group on Organised Crime; the Centre for Information and Research on Organised Crime; the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime; the International Association for the Study of Organized Crime; RUSI’s Strategic Hub on Organised Crime; Transcrime.

Our sample is drawn from these two because they are the longest standing and most prestigious journals outside Crime, Law and Social Change , which has drifted away from organised crime in recent years to the extent that it may no longer be considered a specialised journal. The Journal of Illicit Economies and European Review of Organised Crime are relatively new journals.

While the definition of organised crime is contested, in this paper we take ‘organized crime’ as representing an ‘open, multi-dimensional and dynamic concept to mark out a field of study’ (von Lampe 2002 :195).

Over the 16 years studied, 627 individual authors contributed to the two journals. The figure of 846 includes repeat contributions (i.e. Georgios Antonopoulos contributed 19 of the 846 contributions).

Similar observations have been made about street gang research (Baird et al. 2021 ; Peterson 2018 ).

While we do not have data on social class, it would be reasonable to surmise that, on average, scholars from the Global South who produce their work in institutions located in the Global North represent an elite class with access to this migration opportunity, indicating a marginalization of low social economic classes in the production of knowledge.

While editing services are available for those with English as a second language, the expense of employing such services can be difficult for those without funding.

We acknowledge that many scholars submit to peer-reviewed journals published in their national language (i.e. much of Francisco Thoumi’s research on drug markets was published in Spanish). The lack of access to English language publications can, however, produce an inequality within an ‘increasingly Anglophone global knowledge economy’, whereby scholars are placed under institutional pressure to publish within ‘elite Northern journals’ (Connell et al. 2017 :31), partly to compete in university ranking systems (Jöns and Hoyler 2013 ).

This phenomenon is evident even in Ireland, where two of the authors are based. Here, insufficient state funding for PhDs and research, coupled with too few secure jobs and barriers to promotion, can result in scholars moving abroad for funding, jobs, and/or promotion.

Aas KF (2012) ‘The earth is one but the world is not’: criminological theory and its geopolitical divisions. Theor Criminol 16(1):5–20

Article Google Scholar

Albanese JS (2021) Organized crime as financial crime: the nature of organized crime as reflected in prosecutions and research. Vict Offenders 16(3):431–443

Allum F (2006) Camorristi, Politicians and Businessmen: The Transformation of Organized Crime in Post-War Naples. Maney, Leeds

Google Scholar

Allum F (2016) The invisible camorra: Neapolitan crime families across Europe. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Book Google Scholar

Ardoin S, Martinez B (2019) Straddling class in the academy. Stylus, London

Arsovska J, Allum F (2014) Introduction: women and transnational organized crime. Trends Organ Crim 17(1-2):1–15

Baird A (2018) Dancing with danger: ethnographic safety, male bravado and gang research in Colombia. Qual Res 18(3):342–360

Baird A (2020) Macho Research: Bravado, Danger, and Ethnographic Safety. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/latamcaribbean/2020/02/13/macho-research-bravado-danger-and-ethnographic-safety/ . Accessed September 9, 2021

Baird A, Bishop ML, Kerrigan D (2021) ‘Breaking bad’? Gangs, masculinities, and murder in Trinidad. Int Fem J Polit (online first)

Baker M (2010) Career confidence and gendered expectations of academic promotion. J Sociol 46(3):317–334

Barberet R, Ellis T (2013) International collaboration in criminology. In: Caneppele S, Calderoni F (eds) Organized crime, corruption, and crime prevention - essays in honour of Ernesto U. Savona. Amsterdam, Springer, pp 321–326

Beare ME (2010) Women and organized crime. Department of Public Safety, Canada

Becker HS, Horowitz IL (1972) Radical politics and sociological research. Am J Sociol 78(1):48–66

Bhopal K (2015) The experiences of black and minority ethnic academics: a comparative study of the unequal academy. Routledge, Abingdon

Carey E (2014) Women drug traffickers: mules, bosses, and organized crime. University of New Mexico Press, London

Chambliss W (1975) On the paucity of original research on organized crime. Am Sociol 10(1):36–39

Chambliss W (1978) On the take: from petty crooks to presidents. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Chesney-Lind M, Chagnon N (2016) Criminology, gender, and race: a case study of privilege in the academy. Fem Criminol 11(4):311–333

Ciocchini, P, Greener J (2021) Mapping the pains of neo-colonialism: a critical elaboration of southern criminology. Brit J Criminol (online first)

Cloward RA, Ohlin LE (1961) Delinquency and opportunity: a study of delinquent gangs. Free Press, London

Connell R, Collyer F, Maia J, Morrell R (2017) Toward a global sociology of knowledge: post-colonial realities and intellectual practices. Int Sociol 32(1):21–37

Cressey DR (1967) Methodological problems in the study of organized crime as a social problem. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 374(1):101–112

Daly K, Chesney-Lind M (1988) Feminism and criminology. Justice Q 5(3):497–538

Decker S, Chapman MT (2008) Drug Smugglers on Drug Smuggling. Temple University Press, London

Del Carmen A, Bing RL (2000) Academic productivity of African Americans in criminology and criminal justice. J Crim Justice Educ 11(2):237–249

Durán-Martínez A (2017) The politics of drug violence: criminals, cops and politicians in Colombia and Mexico. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fahmy C, Young JT (2017) Gender inequality and knowledge production in criminology and criminal justice. J Crim Justice Educ 28(2):285–305

Felbab-Brown V (2014) Security Considerations for Conducting Fieldwork in Highly Dangerous Places or on Highly Dangerous Subjects. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/06_security_considerations_fieldwork_felbab_brown_report.pdf . Accessed June 8 2018

Fiandaca G (2007) Women and the mafia: female roles in organized crime structures. Springer, Amsterdam

Fijnaut C (1989) Researching organized crime. In: Morgan R (ed) Policing organised crime and crime prevention. Bristol, Centre for Criminal Justice, pp 75–85

Finckenauer JO, Chin KL (2006) Asian transnational organized crime and its impact on the United States: developing a transnational crime research agenda. Trends Organ Crim 10(2):18–107 Reprinted

Gundur RV (2019) Using the internet to recruit respondents for offline interviews in criminological studies. Urban Aff Rev 55(6):1731–1756

Gundur RV (2020) Finding the sweet spot: optimizing criminal careers within the context of illicit enterprise. Deviant Behav 41(3):378–397

Gundur RV (2022) Trying to make it: the enterprises, people, and gangs of the American drug trade. Cornell University Press, Ithica

Hall A, Koenraadt R, Antonopoulos GA (2017) Illicit pharmaceutical networks in Europe: organising the illicit medicine market in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Trends Organ Crim 20(3-4):296–315