- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » 500+ Qualitative Research Titles and Topics

500+ Qualitative Research Titles and Topics

Table of Contents

Qualitative research is a methodological approach that involves gathering and analyzing non-numerical data to understand and interpret social phenomena. Unlike quantitative research , which emphasizes the collection of numerical data through surveys and experiments, qualitative research is concerned with exploring the subjective experiences, perspectives, and meanings of individuals and groups. As such, qualitative research topics can be diverse and encompass a wide range of social issues and phenomena. From exploring the impact of culture on identity formation to examining the experiences of marginalized communities, qualitative research offers a rich and nuanced perspective on complex social issues. In this post, we will explore some of the most compelling qualitative research topics and provide some tips on how to conduct effective qualitative research.

Qualitative Research Titles

Qualitative research titles often reflect the study’s focus on understanding the depth and complexity of human behavior, experiences, or social phenomena. Here are some examples across various fields:

- “Understanding the Impact of Project-Based Learning on Student Engagement in High School Classrooms: A Qualitative Study”

- “Navigating the Transition: Experiences of International Students in American Universities”

- “The Role of Parental Involvement in Early Childhood Education: Perspectives from Teachers and Parents”

- “Exploring the Effects of Teacher Feedback on Student Motivation and Self-Efficacy in Middle Schools”

- “Digital Literacy in the Classroom: Teacher Strategies for Integrating Technology in Elementary Education”

- “Culturally Responsive Teaching Practices: A Case Study in Diverse Urban Schools”

- “The Influence of Extracurricular Activities on Academic Achievement: Student Perspectives”

- “Barriers to Implementing Inclusive Education in Public Schools: A Qualitative Inquiry”

- “Teacher Professional Development and Its Impact on Classroom Practice: A Qualitative Exploration”

- “Student-Centered Learning Environments: A Qualitative Study of Classroom Dynamics and Outcomes”

- “The Experience of First-Year Teachers: Challenges, Support Systems, and Professional Growth”

- “Exploring the Role of School Leadership in Fostering a Positive School Culture”

- “Peer Relationships and Learning Outcomes in Cooperative Learning Settings: A Qualitative Analysis”

- “The Impact of Social Media on Student Learning and Engagement: Teacher and Student Perspectives”

- “Understanding Special Education Needs: Parent and Teacher Perceptions of Support Services in Schools

Health Science

- “Living with Chronic Pain: Patient Narratives and Coping Strategies in Managing Daily Life”

- “Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives on the Challenges of Rural Healthcare Delivery”

- “Exploring the Mental Health Impacts of COVID-19 on Frontline Healthcare Workers: A Qualitative Study”

- “Patient and Family Experiences of Palliative Care: Understanding Needs and Preferences”

- “The Role of Community Health Workers in Improving Access to Maternal Healthcare in Rural Areas”

- “Barriers to Mental Health Services Among Ethnic Minorities: A Qualitative Exploration”

- “Understanding Patient Satisfaction in Telemedicine Services: A Qualitative Study of User Experiences”

- “The Impact of Cultural Competence Training on Healthcare Provider-Patient Communication”

- “Navigating the Transition to Adult Healthcare Services: Experiences of Adolescents with Chronic Conditions”

- “Exploring the Use of Alternative Medicine Among Patients with Chronic Diseases: A Qualitative Inquiry”

- “The Role of Social Support in the Rehabilitation Process of Stroke Survivors”

- “Healthcare Decision-Making Among Elderly Patients: A Qualitative Study of Preferences and Influences”

- “Nurse Perceptions of Patient Safety Culture in Hospital Settings: A Qualitative Analysis”

- “Experiences of Women with Postpartum Depression: Barriers to Seeking Help”

- “The Impact of Nutrition Education on Eating Behaviors Among College Students: A Qualitative Approach”

- “Understanding Resilience in Survivors of Childhood Trauma: A Narrative Inquiry”

- “The Role of Mindfulness in Managing Work-Related Stress Among Corporate Employees: A Qualitative Study”

- “Coping Mechanisms Among Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder”

- “Exploring the Psychological Impact of Social Isolation in the Elderly: A Phenomenological Study”

- “Identity Formation in Adolescence: The Influence of Social Media and Peer Groups”

- “The Experience of Forgiveness in Interpersonal Relationships: A Qualitative Exploration”

- “Perceptions of Happiness and Well-Being Among University Students: A Cultural Perspective”

- “The Impact of Art Therapy on Anxiety and Depression in Adult Cancer Patients”

- “Narratives of Recovery: A Qualitative Study on the Journey Through Addiction Rehabilitation”

- “Exploring the Psychological Effects of Long-Term Unemployment: A Grounded Theory Approach”

- “Attachment Styles and Their Influence on Adult Romantic Relationships: A Qualitative Analysis”

- “The Role of Personal Values in Career Decision-Making Among Young Adults”

- “Understanding the Stigma of Mental Illness in Rural Communities: A Qualitative Inquiry”

- “Exploring the Use of Digital Mental Health Interventions Among Adolescents: A Qualitative Study”

- “The Psychological Impact of Climate Change on Young Adults: An Exploration of Anxiety and Action”

- “Navigating Identity: The Role of Social Media in Shaping Youth Culture and Self-Perception”

- “Community Resilience in the Face of Urban Gentrification: A Case Study of Neighborhood Change”

- “The Dynamics of Intergenerational Relationships in Immigrant Families: A Qualitative Analysis”

- “Social Capital and Economic Mobility in Low-Income Neighborhoods: An Ethnographic Approach”

- “Gender Roles and Career Aspirations Among Young Adults in Conservative Societies”

- “The Stigma of Mental Health in the Workplace: Employee Narratives and Organizational Culture”

- “Exploring the Intersection of Race, Class, and Education in Urban School Systems”

- “The Impact of Digital Divide on Access to Healthcare Information in Rural Communities”

- “Social Movements and Political Engagement Among Millennials: A Qualitative Study”

- “Cultural Adaptation and Identity Among Second-Generation Immigrants: A Phenomenological Inquiry”

- “The Role of Religious Institutions in Providing Community Support and Social Services”

- “Negotiating Public Space: Experiences of LGBTQ+ Individuals in Urban Environments”

- “The Sociology of Food: Exploring Eating Habits and Food Practices Across Cultures”

- “Work-Life Balance Challenges Among Dual-Career Couples: A Qualitative Exploration”

- “The Influence of Peer Networks on Substance Use Among Adolescents: A Community Study”

Business and Management

- “Navigating Organizational Change: Employee Perceptions and Adaptation Strategies in Mergers and Acquisitions”

- “Corporate Social Responsibility: Consumer Perceptions and Brand Loyalty in the Retail Sector”

- “Leadership Styles and Organizational Culture: A Comparative Study of Tech Startups”

- “Workplace Diversity and Inclusion: Best Practices and Challenges in Multinational Corporations”

- “Consumer Trust in E-commerce: A Qualitative Study of Online Shopping Behaviors”

- “The Gig Economy and Worker Satisfaction: Exploring the Experiences of Freelance Professionals”

- “Entrepreneurial Resilience: Success Stories and Lessons Learned from Failed Startups”

- “Employee Engagement and Productivity in Remote Work Settings: A Post-Pandemic Analysis”

- “Brand Storytelling: How Narrative Strategies Influence Consumer Engagement”

- “Sustainable Business Practices: Stakeholder Perspectives in the Fashion Industry”

- “Cross-Cultural Communication Challenges in Global Teams: Strategies for Effective Collaboration”

- “Innovative Workspaces: The Impact of Office Design on Creativity and Collaboration”

- “Consumer Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence in Customer Service: A Qualitative Exploration”

- “The Role of Mentoring in Career Development: Insights from Women in Leadership Positions”

- “Agile Management Practices: Adoption and Impact in Traditional Industries”

Environmental Studies

- “Community-Based Conservation Efforts in Tropical Rainforests: A Qualitative Study of Local Perspectives and Practices”

- “Urban Sustainability Initiatives: Exploring Resident Participation and Impact in Green City Projects”

- “Perceptions of Climate Change Among Indigenous Populations: Insights from Traditional Ecological Knowledge”

- “Environmental Justice and Industrial Pollution: A Case Study of Community Advocacy and Response”

- “The Role of Eco-Tourism in Promoting Conservation Awareness: Perspectives from Tour Operators and Visitors”

- “Sustainable Agriculture Practices Among Smallholder Farmers: Challenges and Opportunities”

- “Youth Engagement in Climate Action Movements: Motivations, Perceptions, and Outcomes”

- “Corporate Environmental Responsibility: A Qualitative Analysis of Stakeholder Expectations and Company Practices”

- “The Impact of Plastic Pollution on Marine Ecosystems: Community Awareness and Behavioral Change”

- “Renewable Energy Adoption in Rural Communities: Barriers, Facilitators, and Social Implications”

- “Water Scarcity and Community Adaptation Strategies in Arid Regions: A Grounded Theory Approach”

- “Urban Green Spaces: Public Perceptions and Use Patterns in Megacities”

- “Environmental Education in Schools: Teachers’ Perspectives on Integrating Sustainability into Curricula”

- “The Influence of Environmental Activism on Policy Change: Case Studies of Grassroots Campaigns”

- “Cultural Practices and Natural Resource Management: A Qualitative Study of Indigenous Stewardship Models”

Anthropology

- “Kinship and Social Organization in Matrilineal Societies: An Ethnographic Study”

- “Rituals and Beliefs Surrounding Death and Mourning in Diverse Cultures: A Comparative Analysis”

- “The Impact of Globalization on Indigenous Languages and Cultural Identity”

- “Food Sovereignty and Traditional Agricultural Practices Among Indigenous Communities”

- “Navigating Modernity: The Integration of Traditional Healing Practices in Contemporary Healthcare Systems”

- “Gender Roles and Equality in Hunter-Gatherer Societies: An Anthropological Perspective”

- “Sacred Spaces and Religious Practices: An Ethnographic Study of Pilgrimage Sites”

- “Youth Subcultures and Resistance: An Exploration of Identity and Expression in Urban Environments”

- “Cultural Constructions of Disability and Inclusion: A Cross-Cultural Analysis”

- “Interethnic Marriages and Cultural Syncretism: Case Studies from Multicultural Societies”

- “The Role of Folklore and Storytelling in Preserving Cultural Heritage”

- “Economic Anthropology of Gift-Giving and Reciprocity in Tribal Communities”

- “Digital Anthropology: The Role of Social Media in Shaping Political Movements”

- “Migration and Diaspora: Maintaining Cultural Identity in Transnational Communities”

- “Cultural Adaptations to Climate Change Among Coastal Fishing Communities”

Communication Studies

- “The Dynamics of Family Communication in the Digital Age: A Qualitative Inquiry”

- “Narratives of Identity and Belonging in Diaspora Communities Through Social Media”

- “Organizational Communication and Employee Engagement: A Case Study in the Non-Profit Sector”

- “Cultural Influences on Communication Styles in Multinational Teams: An Ethnographic Approach”

- “Media Representation of Women in Politics: A Content Analysis and Audience Perception Study”

- “The Role of Communication in Building Sustainable Community Development Projects”

- “Interpersonal Communication in Online Dating: Strategies, Challenges, and Outcomes”

- “Public Health Messaging During Pandemics: A Qualitative Study of Community Responses”

- “The Impact of Mobile Technology on Parent-Child Communication in the Digital Era”

- “Crisis Communication Strategies in the Hospitality Industry: A Case Study of Reputation Management”

- “Narrative Analysis of Personal Stories Shared on Mental Health Blogs”

- “The Influence of Podcasts on Political Engagement Among Young Adults”

- “Visual Communication and Brand Identity: A Qualitative Study of Consumer Interpretations”

- “Communication Barriers in Cross-Cultural Healthcare Settings: Patient and Provider Perspectives”

- “The Role of Internal Communication in Managing Organizational Change: Employee Experiences”

Information Technology

- “User Experience Design in Augmented Reality Applications: A Qualitative Study of Best Practices”

- “The Human Factor in Cybersecurity: Understanding Employee Behaviors and Attitudes Towards Phishing”

- “Adoption of Cloud Computing in Small and Medium Enterprises: Challenges and Success Factors”

- “Blockchain Technology in Supply Chain Management: A Qualitative Exploration of Potential Impacts”

- “The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Personalizing User Experiences on E-commerce Platforms”

- “Digital Transformation in Traditional Industries: A Case Study of Technology Adoption Challenges”

- “Ethical Considerations in the Development of Smart Home Technologies: A Stakeholder Analysis”

- “The Impact of Social Media Algorithms on News Consumption and Public Opinion”

- “Collaborative Software Development: Practices and Challenges in Open Source Projects”

- “Understanding the Digital Divide: Access to Information Technology in Rural Communities”

- “Data Privacy Concerns and User Trust in Internet of Things (IoT) Devices”

- “The Effectiveness of Gamification in Educational Software: A Qualitative Study of Engagement and Motivation”

- “Virtual Teams and Remote Work: Communication Strategies and Tools for Effectiveness”

- “User-Centered Design in Mobile Health Applications: Evaluating Usability and Accessibility”

- “The Influence of Technology on Work-Life Balance: Perspectives from IT Professionals”

Tourism and Hospitality

- “Exploring the Authenticity of Cultural Heritage Tourism in Indigenous Communities”

- “Sustainable Tourism Practices: Perceptions and Implementations in Small Island Destinations”

- “The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Destination Choice Among Millennials”

- “Gastronomy Tourism: Exploring the Culinary Experiences of International Visitors in Rural Regions”

- “Eco-Tourism and Conservation: Stakeholder Perspectives on Balancing Tourism and Environmental Protection”

- “The Role of Hospitality in Enhancing the Cultural Exchange Experience of Exchange Students”

- “Dark Tourism: Visitor Motivations and Experiences at Historical Conflict Sites”

- “Customer Satisfaction in Luxury Hotels: A Qualitative Study of Service Excellence and Personalization”

- “Adventure Tourism: Understanding the Risk Perception and Safety Measures Among Thrill-Seekers”

- “The Influence of Local Communities on Tourist Experiences in Ecotourism Sites”

- “Event Tourism: Economic Impacts and Community Perspectives on Large-Scale Music Festivals”

- “Heritage Tourism and Identity: Exploring the Connections Between Historic Sites and National Identity”

- “Tourist Perceptions of Sustainable Accommodation Practices: A Study of Green Hotels”

- “The Role of Language in Shaping the Tourist Experience in Multilingual Destinations”

- “Health and Wellness Tourism: Motivations and Experiences of Visitors to Spa and Retreat Centers”

Qualitative Research Topics

Qualitative Research Topics are as follows:

- Understanding the lived experiences of first-generation college students

- Exploring the impact of social media on self-esteem among adolescents

- Investigating the effects of mindfulness meditation on stress reduction

- Analyzing the perceptions of employees regarding organizational culture

- Examining the impact of parental involvement on academic achievement of elementary school students

- Investigating the role of music therapy in managing symptoms of depression

- Understanding the experience of women in male-dominated industries

- Exploring the factors that contribute to successful leadership in non-profit organizations

- Analyzing the effects of peer pressure on substance abuse among adolescents

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with disabilities in the workplace

- Understanding the factors that contribute to burnout among healthcare professionals

- Examining the impact of social support on mental health outcomes

- Analyzing the perceptions of parents regarding sex education in schools

- Investigating the experiences of immigrant families in the education system

- Understanding the impact of trauma on mental health outcomes

- Exploring the effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy for individuals with anxiety

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful intergenerational relationships

- Investigating the experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in the workplace

- Understanding the impact of online gaming on social skills development among adolescents

- Examining the perceptions of teachers regarding technology integration in the classroom

- Analyzing the experiences of women in leadership positions

- Investigating the factors that contribute to successful marriage and long-term relationships

- Understanding the impact of social media on political participation

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with mental health disorders in the criminal justice system

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful community-based programs for youth development

- Investigating the experiences of veterans in accessing mental health services

- Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood obesity prevention

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful multicultural education programs

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in the workplace

- Understanding the impact of poverty on academic achievement

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with autism spectrum disorder in the workplace

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful employee retention strategies

- Investigating the experiences of caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease

- Understanding the impact of parent-child communication on adolescent sexual behavior

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding mental health services on campus

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful team building in the workplace

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with eating disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of mentorship on career success

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with physical disabilities in the workplace

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful community-based programs for mental health

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with substance use disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of social media on romantic relationships

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding child discipline strategies

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful cross-cultural communication in the workplace

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with anxiety disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural differences on healthcare delivery

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with hearing loss in the workplace

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful parent-teacher communication

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with depression in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of childhood trauma on adult mental health outcomes

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding alcohol and drug use on campus

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful mentor-mentee relationships

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with intellectual disabilities in the workplace

- Understanding the impact of work-family balance on employee satisfaction and well-being

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with autism spectrum disorder in vocational rehabilitation programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful project management in the construction industry

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with substance use disorders in peer support groups

- Understanding the impact of mindfulness meditation on stress reduction and mental health

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood nutrition

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful environmental sustainability initiatives in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with bipolar disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of job stress on employee burnout and turnover

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with physical disabilities in recreational activities

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful strategic planning in nonprofit organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with hoarding disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of culture on leadership styles and effectiveness

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding sexual health education on campus

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain management in the retail industry

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with personality disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of multiculturalism on group dynamics in the workplace

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic pain in mindfulness-based pain management programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful employee engagement strategies in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with internet addiction disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of social comparison on body dissatisfaction and self-esteem

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood sleep habits

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful diversity and inclusion initiatives in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with schizophrenia in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of job crafting on employee motivation and job satisfaction

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with vision impairments in navigating public spaces

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful customer relationship management strategies in the service industry

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with dissociative amnesia in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural intelligence on intercultural communication and collaboration

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding campus diversity and inclusion efforts

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain sustainability initiatives in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of transformational leadership on organizational performance and employee well-being

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with mobility impairments in public transportation

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful talent management strategies in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with substance use disorders in harm reduction programs

- Understanding the impact of gratitude practices on well-being and resilience

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood mental health and well-being

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful corporate social responsibility initiatives in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with borderline personality disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of emotional labor on job stress and burnout

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with hearing impairments in healthcare settings

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful customer experience strategies in the hospitality industry

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with gender dysphoria in gender-affirming healthcare

- Understanding the impact of cultural differences on cross-cultural negotiation in the global marketplace

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding academic stress and mental health

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain agility in organizations

- Understanding the impact of music therapy on mental health and well-being

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with dyslexia in educational settings

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful leadership in nonprofit organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in online support groups

- Understanding the impact of exercise on mental health and well-being

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood screen time

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful change management strategies in organizations

- Understanding the impact of cultural differences on international business negotiations

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with hearing impairments in the workplace

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful team building in corporate settings

- Understanding the impact of technology on communication in romantic relationships

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful community engagement strategies for local governments

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of financial stress on mental health and well-being

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful mentorship programs in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with gambling addictions in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of social media on body image and self-esteem

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood education

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful virtual team management strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with dissociative identity disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural differences on cross-cultural communication in healthcare settings

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic pain in cognitive-behavioral therapy programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful community-building strategies in urban neighborhoods

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with alcohol use disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding mental health stigma on campus

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful fundraising strategies for political campaigns

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with traumatic brain injuries in rehabilitation programs

- Understanding the impact of social support on mental health and well-being among the elderly

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in medical treatment decision-making processes

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful innovation strategies in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with dissociative disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural differences on cross-cultural communication in education settings

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood physical activity

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful conflict resolution in family relationships

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with opioid use disorders in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of emotional intelligence on leadership effectiveness

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with learning disabilities in the workplace

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful change management in educational institutions

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with eating disorders in recovery support groups

- Understanding the impact of self-compassion on mental health and well-being

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding campus safety and security measures

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful marketing strategies for nonprofit organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with postpartum depression in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of ageism in the workplace

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with dyslexia in the education system

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with anxiety disorders in cognitive-behavioral therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of socioeconomic status on access to healthcare

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood screen time usage

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain management strategies

- Understanding the impact of parenting styles on child development

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with addiction in harm reduction programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful crisis management strategies in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with trauma in trauma-focused therapy programs

- Examining the perceptions of healthcare providers regarding patient-centered care

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful product development strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with autism spectrum disorder in employment programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural competence on healthcare outcomes

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in healthcare navigation

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful community engagement strategies for non-profit organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with physical disabilities in the workplace

- Understanding the impact of childhood trauma on adult mental health

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain sustainability strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with personality disorders in dialectical behavior therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of gender identity on mental health treatment seeking behaviors

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with schizophrenia in community-based treatment programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful project team management strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder in exposure and response prevention therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural competence on academic achievement and success

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding academic integrity

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful social media marketing strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with bipolar disorder in community-based treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of mindfulness on academic achievement and success

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with substance use disorders in medication-assisted treatment programs

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with anxiety disorders in exposure therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of healthcare disparities on health outcomes

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain optimization strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with borderline personality disorder in schema therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of culture on perceptions of mental health stigma

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with trauma in art therapy programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful digital marketing strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with eating disorders in online support groups

- Understanding the impact of workplace bullying on job satisfaction and performance

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding mental health resources on campus

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful supply chain risk management strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic pain in mindfulness-based pain management programs

- Understanding the impact of cognitive-behavioral therapy on social anxiety disorder

- Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and well-being

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with eating disorders in treatment programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful leadership in business organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic pain in cognitive-behavioral therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of cultural differences on intercultural communication

- Examining the perceptions of teachers regarding inclusive education for students with disabilities

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with depression in therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of workplace culture on employee retention and turnover

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with traumatic brain injuries in rehabilitation programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful crisis communication strategies in organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with anxiety disorders in mindfulness-based interventions

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in healthcare settings

- Understanding the impact of technology on work-life balance

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with learning disabilities in academic settings

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful entrepreneurship in small businesses

- Understanding the impact of gender identity on mental health and well-being

- Examining the perceptions of individuals with disabilities regarding accessibility in public spaces

- Understanding the impact of religion on coping strategies for stress and anxiety

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in complementary and alternative medicine treatments

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful customer retention strategies in business organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with postpartum depression in therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of ageism on older adults in healthcare settings

- Examining the perceptions of students regarding online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful team building in virtual work environments

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with gambling disorders in treatment programs

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in peer support groups

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful social media marketing strategies for businesses

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with ADHD in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of sleep on cognitive and emotional functioning

- Examining the perceptions of individuals with chronic illnesses regarding healthcare access and affordability

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with borderline personality disorder in dialectical behavior therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of social support on caregiver well-being

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in disability activism

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful cultural competency training programs in healthcare settings

- Understanding the impact of personality disorders on interpersonal relationships

- Examining the perceptions of healthcare providers regarding the use of telehealth services

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with dissociative disorders in therapy programs

- Understanding the impact of gender bias in hiring practices

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with visual impairments in the workplace

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful diversity and inclusion programs in the workplace

- Understanding the impact of online dating on romantic relationships

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood vaccination

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful communication in healthcare settings

- Understanding the impact of cultural stereotypes on academic achievement

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with substance use disorders in sober living programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful classroom management strategies

- Understanding the impact of social support on addiction recovery

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding mental health stigma

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful conflict resolution in the workplace

- Understanding the impact of race and ethnicity on healthcare access and outcomes

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder in treatment programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful project management strategies

- Understanding the impact of teacher-student relationships on academic achievement

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful customer service strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with social anxiety disorder in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of workplace stress on job satisfaction and performance

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with disabilities in sports and recreation

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful marketing strategies for small businesses

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with phobias in treatment programs

- Understanding the impact of culture on attitudes towards mental health and illness

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding sexual assault prevention

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful time management strategies

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with addiction in recovery support groups

- Understanding the impact of mindfulness on emotional regulation and well-being

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with chronic pain in treatment programs

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful conflict resolution in romantic relationships

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with autism spectrum disorder in social skills training programs

- Understanding the impact of parent-child communication on adolescent substance use

- Examining the perceptions of parents regarding childhood mental health services

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful fundraising strategies for non-profit organizations

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses in support groups

- Understanding the impact of personality traits on career success and satisfaction

- Exploring the experiences of individuals with disabilities in accessing public transportation

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful team building in sports teams

- Investigating the experiences of individuals with chronic pain in alternative medicine treatments

- Understanding the impact of stigma on mental health treatment seeking behaviors

- Examining the perceptions of college students regarding diversity and inclusion on campus.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

500+ Criminal Justice Research Topics

500+ Google Scholar Research Topics

300+ AP Research Topic Ideas

300+ American History Research Paper Topics

1000+ Sociology Research Topics

300+ Communication Research Topics

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

675k Accesses

262 Citations

88 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

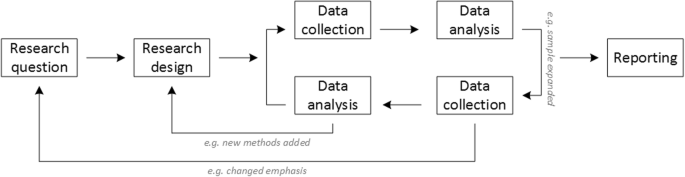

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

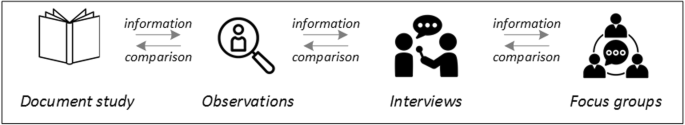

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

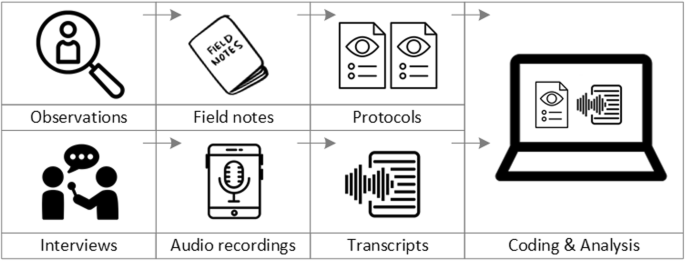

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

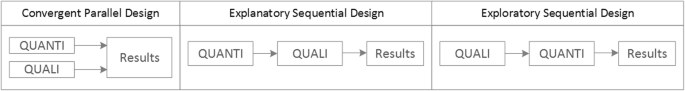

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.