- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Frederick Douglass

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 8, 2024 | Original: October 27, 2009

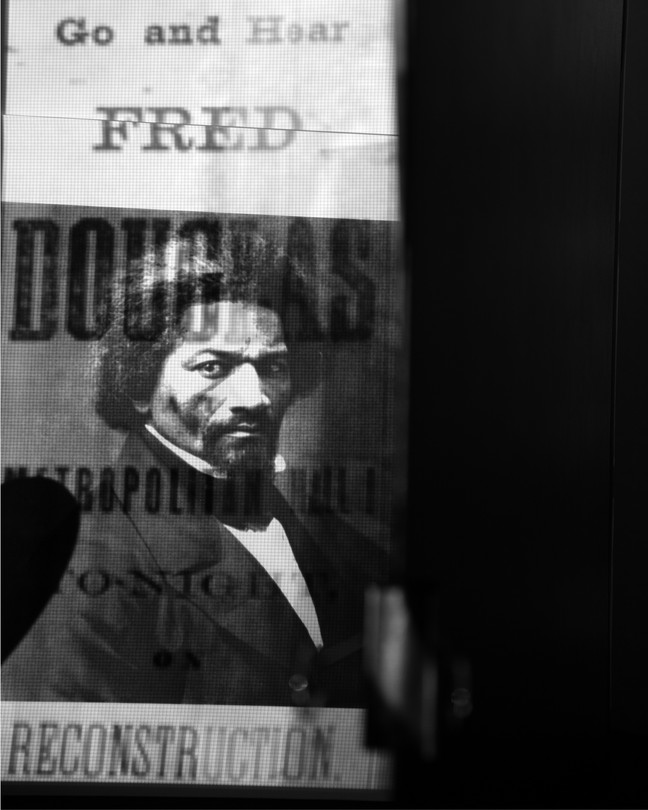

Frederick Douglass was a formerly enslaved man who became a prominent activist, author and public speaker. He became a leader in the abolitionist movement , which sought to end the practice of slavery, before and during the Civil War . After that conflict and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, he continued to push for equality and human rights until his death in 1895.

Douglass’ 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , described his time as an enslaved worker in Maryland . It was one of three autobiographies he penned, along with dozens of noteworthy speeches, despite receiving minimal formal education.

An advocate for women’s rights, and specifically the right of women to vote , Douglass’ legacy as an author and leader lives on. His work served as an inspiration to the civil rights movement of the 1960s and beyond.

Who Was Frederick Douglass?

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in or around 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. Douglass himself was never sure of his exact birth date.

His mother was an enslaved Black women and his father was white and of European descent. He was actually born Frederick Bailey (his mother’s name), and took the name Douglass only after he escaped. His full name at birth was “Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey.”

After he was separated from his mother as an infant, Douglass lived for a time with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. However, at the age of six, he was moved away from her to live and work on the Wye House plantation in Maryland.

From there, Douglass was “given” to Lucretia Auld, whose husband, Thomas, sent him to work with his brother Hugh in Baltimore. Douglass credits Hugh’s wife Sophia with first teaching him the alphabet. With that foundation, Douglass then taught himself to read and write. By the time he was hired out to work under William Freeland, he was teaching other enslaved people to read using the Bible .

As word spread of his efforts to educate fellow enslaved people, Thomas Auld took him back and transferred him to Edward Covey, a farmer who was known for his brutal treatment of the enslaved people in his charge. Roughly 16 at this time, Douglass was regularly whipped by Covey.

Frederick Douglass Escapes from Slavery

After several failed attempts at escape, Douglass finally left Covey’s farm in 1838, first boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. From there he traveled through Delaware , another slave state, before arriving in New York and the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles.

Once settled in New York, he sent for Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore he met while in captivity with the Aulds. She joined him, and the two were married in September 1838. They had five children together.

From Slavery to Abolitionist Leader

After their marriage, the young couple moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts , where they met Nathan and Mary Johnson, a married couple who were born “free persons of color.” It was the Johnsons who inspired the couple to take the surname Douglass, after the character in the Sir Walter Scott poem, “The Lady of the Lake.”

In New Bedford, Douglass began attending meetings of the abolitionist movement . During these meetings, he was exposed to the writings of abolitionist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison.

The two men eventually met when both were asked to speak at an abolitionist meeting, during which Douglass shared his story of slavery and escape. It was Garrison who encouraged Douglass to become a speaker and leader in the abolitionist movement.

By 1843, Douglass had become part of the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Hundred Conventions” project, a six-month tour through the United States. Douglass was physically assaulted several times during the tour by those opposed to the abolitionist movement.

In one particularly brutal attack, in Pendleton, Indiana , Douglass’ hand was broken. The injuries never fully healed, and he never regained full use of his hand.

In 1858, radical abolitionist John Brown stayed with Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, as he planned his raid on the U.S. military arsenal at Harper’s Ferry , part of his attempt to establish a stronghold of formerly enslaved people in the mountains of Maryland and Virginia. Brown was caught and hanged for masterminding the attack, offering the following prophetic words as his final statement: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

'Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass'

Two years later, Douglass published the first and most famous of his autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave . (He also authored My Bondage and My Freedom and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass).

In it Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass , he wrote: “From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom.”

He also noted, “Thus is slavery the enemy of both the slave and the slaveholder.”

Frederick Douglass in Ireland and Great Britain

Later that same year, Douglass would travel to Ireland and Great Britain. At the time, the former country was just entering the early stages of the Irish Potato Famine , or the Great Hunger.

While overseas, he was impressed by the relative freedom he had as a man of color, compared to what he had experienced in the United States. During his time in Ireland, he met the Irish nationalist Daniel O’Connell , who became an inspiration for his later work.

In England, Douglass also delivered what would later be viewed as one of his most famous speeches, the so-called “London Reception Speech.”

In the speech, he said, “What is to be thought of a nation boasting of its liberty, boasting of its humanity, boasting of its Christianity , boasting of its love of justice and purity, and yet having within its own borders three millions of persons denied by law the right of marriage?… I need not lift up the veil by giving you any experience of my own. Every one that can put two ideas together, must see the most fearful results from such a state of things…”

Frederick Douglass’ Abolitionist Paper

When he returned to the United States in 1847, Douglass began publishing his own abolitionist newsletter, the North Star . He also became involved in the movement for women’s rights .

He was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention , a gathering of women’s rights activists in New York, in 1848.

He spoke forcefully during the meeting and said, “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

He later included coverage of women’s rights issues in the pages of the North Star . The newsletter’s name was changed to Frederick Douglass’ Paper in 1851, and was published until 1860, just before the start of the Civil War .

Frederick Douglass Quotes

In 1852, he delivered another of his more famous speeches, one that later came to be called “What to a slave is the 4th of July?”

In one section of the speech, Douglass noted, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

For the 24th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation , in 1886, Douglass delivered a rousing address in Washington, D.C., during which he said, “where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.”

Frederick Douglass During the Civil War

During the brutal conflict that divided the still-young United States, Douglass continued to speak and worked tirelessly for the end of slavery and the right of newly freed Black Americans to vote.

Although he supported President Abraham Lincoln in the early years of the Civil War, Douglass fell into disagreement with the politician after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which effectively ended the practice of slavery. Douglass was disappointed that Lincoln didn’t use the proclamation to grant formerly enslaved people the right to vote, particularly after they had fought bravely alongside soldiers for the Union army.

It is said, though, that Douglass and Lincoln later reconciled and, following Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, and the passage of the 13th amendment , 14th amendment , and 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which, respectively, outlawed slavery, granted formerly enslaved people citizenship and equal protection under the law, and protected all citizens from racial discrimination in voting), Douglass was asked to speak at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park in 1876.

Historians, in fact, suggest that Lincoln’s widow, Mary Todd Lincoln , bequeathed the late-president’s favorite walking stick to Douglass after that speech.

In the post-war Reconstruction era, Douglass served in many official positions in government, including as an ambassador to the Dominican Republic, thereby becoming the first Black man to hold high office. He also continued speaking and advocating for African American and women’s rights.

In the 1868 presidential election, he supported the candidacy of former Union general Ulysses S. Grant , who promised to take a hard line against white supremacist-led insurgencies in the post-war South. Grant notably also oversaw passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 , which was designed to suppress the growing Ku Klux Klan movement.

Frederick Douglass: Later Life and Death

In 1877, Douglass met with Thomas Auld , the man who once “owned” him, and the two reportedly reconciled.

Douglass’ wife Anna died in 1882, and he married white activist Helen Pitts in 1884.

In 1888, he became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States, during the Republican National Convention. Ultimately, though, Benjamin Harrison received the party nomination.

Douglass remained an active speaker, writer and activist until his death in 1895. He died after suffering a heart attack at home after arriving back from a meeting of the National Council of Women , a women’s rights group still in its infancy at the time, in Washington, D.C.

His life’s work still serves as an inspiration to those who seek equality and a more just society.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Frederick Douglas, PBS.org . Frederick Douglas, National Parks Service, nps.gov . Frederick Douglas, 1818-1895, Documenting the South, University of North Carolina , docsouth.unc.edu . Frederick Douglass Quotes, brainyquote.com . “Reception Speech. At Finsbury Chapel, Moorfields, England, May 12, 1846.” USF.edu . “What to the slave is the 4th of July?” TeachingAmericanHistory.org . Graham, D.A. (2017). “Donald Trump’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” The Atlantic .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

3.4 Annotated Sample Reading: from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Read in several genres to understand how conventions are shaped by purpose, language, culture, and expectation.

- Use reading for inquiry, learning, critical thinking, and communicating in varying rhetorical and cultural contexts.

- Read a diverse range of texts, attending to relationships among ideas, patterns of organization, and interplay between verbal and nonverbal elements.

Introduction

Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) was born into slavery in Maryland. He never knew his father, barely knew his mother, and was separated from his grandmother at a young age. As a boy, Douglass understood there to be a connection between literacy and freedom. In the excerpt from his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , that follows, you will learn about how Douglass learned to read. By age 12, he was reading texts about the natural rights of human beings. At age 15, he began educating other enslaved people. When Douglass was 20, he met Anna Murray, whom he would later marry. Murray helped Douglass plot his escape from slavery. Dressed as a sailor, Douglass bought a train ticket northward. Within 24 hours, he arrived in New York City and declared himself free. Douglass went on to work as an activist in the abolitionist movement as well as the women’s suffrage movement.

In the portion of the text included here, Douglass chooses to represent the dialogue of Mr. Auld, an enslaver who by the laws of the time owns Douglass. Douglass describes this moment with detail and accuracy, including Mr. Auld’s use of a racial slur. In an interview with the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), Harvard professor Randall Kennedy (b. 1954), who has traced the historical evolution of the word, notes that one of its first uses, recorded in 1619, appears to have been descriptive rather than derogatory. However, by the mid-1800s, White people had appropriated the term and begun using it with its current negative connotation. In response, over time, Black people have reclaimed the word (or variations of it) for different purposes, including mirroring racism, creating irony, and reclaiming community and personal power—using the word for a contrasting purpose to the way others use it. Despite this evolution, Professor Kennedy explains that the use of the word should be accompanied by a deep understanding of one’s audience and by being clear about the intention. However, even when intention is very clear and malice is not intended, harm can, and likely will, occur. Thus, Professor Kennedy cautions that all people should understand the history of the word, be aware of its potential negative effect on an audience, and therefore use it sparingly, or preferably not at all.

In the case of Mr. Auld and Douglass, Douglass gives an account of Auld’s exact language in order to hold a mirror to the racism of Mr. Auld—and the reading audience of his memoir—and to emphasize the theme that literacy (or education) is one way to combat racism.

Living by Their Own Words

Literacy from unexpected sources.

annotated text From the title and from Douglass’s use of pronoun I, you know this work is autobiographical and therefore written from the first-person point of view. end annotated text

public domain text [excerpt begins with first full paragraph on page 33 and ends on page 34 where the paragraph ends] end public domain text

public domain text Very soon after I went to live with Mr. and Mrs. Auld, she very kindly commenced to teach me the A, B, C. After I had learned this, she assisted me in learning to spell words of three or four letters. Just at this point of my progress, Mr. Auld found out what was going on, and at once forbade Mrs. Auld to instruct me further, telling her, among other things, that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass describes the background situation and the culture of the time, which he will defy in his quest for literacy. The word choice in his narration of events indicates that he is writing for an educated audience. end annotated text

public domain text To use his own words, further, he said, “If you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell. A nigger should know nothing but to obey his master—to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world. Now,” said he, “if you teach that nigger (speaking of myself) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” end public domain text

annotated text In sharing this part of the narrative, Douglass underscores the importance of literacy. He provides a description of Mr. Auld, a slaveholder, who seeks to impose illiteracy as a means to oppress others. In this description of Mr. Auld’s reaction, Douglass shows that slaveholders feared the power that enslaved people would have if they could read and write. end annotated text

annotated text Douglass provides the details of Auld’s dialogue not only because it is a convention of narrative genre but also because it demonstrates the purpose and motivation for his forthcoming pursuit of literacy. We have chosen to maintain the authenticity of the original text by using the language that Douglass offers to quote Mr. Auld’s dialogue because it both provides context for the rhetorical situation and underscores the value of the attainment of literacy for Douglass. However, contemporary audiences must understand that this language should be uttered only under very narrow circumstances in any current rhetorical situation. In general, it is best to avoid its use. end annotated text

public domain text These words sank deep into my heart, stirred up sentiments within that lay slumbering, and called into existence an entirely new train of thought. It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain. I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty—to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom. It was just what I wanted, and I got it at a time when I the least expected it. Whilst I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master. end public domain text

annotated text In this reflection, Douglass has a definitive and transformative moment with reading and writing. The moment that sparked a desire for literacy is a common feature in literacy narratives, particularly those of enslaved people. In that moment, he understood the value of literacy and its life-changing possibilities; that transformative moment is a central part of the arc of this literacy narrative. end annotated text

public domain text Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. The very decided manner with which he spoke, and strove to impress his wife with the evil consequences of giving me instruction, served to convince me that he was deeply sensible of the truths he was uttering. It gave me the best assurance that I might rely with the utmost confidence on the results which, he said, would flow from teaching me to read. What he most dreaded, that I most desired. What he most loved, that I most hated. That which to him was a great evil, to be carefully shunned, was to me a great good, to be diligently sought; and the argument which he so warmly urged, against my learning to read, only served to inspire me with a desire and determination to learn. In learning to read, I owe almost as much to the bitter opposition of my master, as to the kindly aid of my mistress. I acknowledge the benefit of both. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass articulates that this moment changed his relationship to literacy and ignited a purposeful engagement with language and learning that would last throughout his long life. The rhythm, sentence structure, and poetic phrasing in this reflection provide further evidence that Douglass, over the course of his life, actively pursued and mastered language after having this experience with Mr. Auld. end annotated text

public domain text [excerpt continues with the beginning of Chapter 7 on page 36 and ends with the end of the paragraph at the top of page 39] end public domain text

public domain text [In Chapter 7, the narrative continues] I lived in Master Hugh’s family about seven years. During this time, I succeeded in learning to read and write. In accomplishing this, I was compelled to resort to various stratagems. I had no regular teacher. My mistress, who had kindly commenced to instruct me, had, in compliance with the advice and direction of her husband, not only ceased to instruct, but had set her face against my being instructed by any one else. It is due, however, to my mistress to say of her, that she did not adopt this course of treatment immediately. She at first lacked the depravity indispensable to shutting me up in mental darkness. It was at least necessary for her to have some training in the exercise of irresponsible power, to make her equal to the task of treating me as though I were a brute. end public domain text

public domain text My mistress was, as I have said, a kind and tender-hearted woman; and in the simplicity of her soul she commenced, when I first went to live with her, to treat me as she supposed one human being ought to treat another. In entering upon the duties of a slaveholder, she did not seem to perceive that I sustained to her the relation of a mere chattel, and that for her to treat me as a human being was not only wrong, but dangerously so. Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me. When I went there, she was a pious, warm, and tender-hearted woman. There was no sorrow or suffering for which she had not a tear. She had bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner that came within her reach. Slavery soon proved its ability to divest her of these heavenly qualities. Under its influence, the tender heart became stone, and the lamblike disposition gave way to one of tiger-like fierceness. The first step in her downward course was in her ceasing to instruct me. She now commenced to practise her husband’s precepts. She finally became even more violent in her opposition than her husband himself. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass describes in detail a person in his life and his relationship to her. He uses specific diction to describe her kindness and to help readers get to know her—a “tear” for the “suffering”; “bread for the hungry, clothes for the naked, and comfort for every mourner.” end annotated text

public domain text She was not satisfied with simply doing as well as he had commanded; she seemed anxious to do better. Nothing seemed to make her more angry than to see me with a newspaper. She seemed to think that here lay the danger. I have had her rush at me with a face made all up of fury, and snatch from me a newspaper, in a manner that fully revealed her apprehension. She was an apt woman; and a little experience soon demonstrated, to her satisfaction, that education and slavery were incompatible with each other. end public domain text

annotated text The fact that Douglass can understand the harm caused by the institution of slavery to slaveholders as well as to enslaved people shows a level of sophistication in thought, identifies the complexity and detriment of this historical period, and demonstrates an acute awareness of the rhetorical situation, especially for his audience for this text. The way that he articulates compassion for the slaveholders, despite their ill treatment of him, would create empathy in his readers and possibly provide a revelation for his audience. end annotated text

public domain text From this time I was most narrowly watched. If I was in a separate room any considerable length of time, I was sure to be suspected of having a book, and was at once called to give an account of myself. All this, however, was too late. The first step had been taken. Mistress, in teaching me the alphabet, had given me the inch , and no precaution could prevent me from taking the ell . end public domain text

annotated text Once again, Douglass underscores the value that literacy has for transforming the lived experiences of enslaved people. The reference to the inch and the ell circles back to Mr. Auld’s warnings and recalls the impact of that moment on his life. end annotated text

public domain text The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent of errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge. I am strongly tempted to give the names of two or three of those little boys, as a testimonial of the gratitude and affection I bear them; but prudence forbids;—not that it would injure me, but it might embarrass them; for it is almost an unpardonable offence to teach slaves to read in this Christian country. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass comments on the culture of the time, which still permitted slavery; he is sensitive to the fact that these boys might be embarrassed by their participation in unacceptable, though humanitarian, behavior. His audience will also recognize the irony in his tone when he writes that it is “an unpardonable offense to teach slaves . . . in this Christian country.” Such behavior is surely “unchristian.” end annotated text

public domain text It is enough to say of the dear little fellows, that they lived on Philpot Street, very near Durgin and Bailey’s ship-yard. I used to talk this matter of slavery over with them. I would sometimes say to them, I wished I could be as free as they would be when they got to be men. “You will be free as soon as you are twenty-one, but I am a slave for life ! Have not I as good a right to be free as you have?” These words used to trouble them; they would express for me the liveliest sympathy, and console me with the hope that something would occur by which I might be free. end public domain text

annotated text Douglass pursues and attains literacy not only for his own benefit; his knowledge also allows him to begin to instruct, as well as advocate for, those around him. Douglass’s use of language and his understanding of the rhetorical situation give the audience evidence of the power of literacy for all people, round out the arc of his narrative, and provide a resolution. end annotated text

Discussion Questions

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/3-4-annotated-sample-reading-from-narrative-of-the-life-of-frederick-douglass-by-frederick-douglass

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

The Annotated

Frederick douglass, introduction and annotations by david w. blight, in 1866, the famous abolitionist laid out his vision for radically reshaping america in the pages of the atlantic ..

In his third autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass , while reflecting on the end of the Civil War, Douglass admitted that “a strange and, perhaps, perverse feeling came over me.” Great joy over the ending of slavery, he wrote, was at times “tinged with a feeling of sadness. I felt I had reached the end of the noblest and best part of my life; my school was broken up, my church disbanded, and the beloved congregation dispersed, never to come together again.” In recalling the postwar years, Douglass drew from a scene in a Shakespearean tragedy to express his memory of that moment: “ ‘Othello’s occupation was gone.’ ” In Othello, Douglass perceived a character, the former high-ranking general and “moor of Venice,” who had lost authority and professional purpose. Douglass harbored a special affinity for this most famous Black character in Western literature, whose mental collapse and horrible end lingered as a warning in a famous speech: “O, now, for ever / Farewell the tranquil mind! Farewell content!”

In 1866, Douglass took up his pen to try to capture this moment of transformation, both for himself and for the United States. For the December issue of this magazine that year, in an essay simply titled “ Reconstruction ,” Douglass observed that “questions of vast moment” lay before Congress and the nation. Nothing less than the essential results of the “tremendous war,” he writes, were at stake. Would the war become “a miserable failure … a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure,” or a “victory over treason,” resulting in a newly reimagined nation “delivered from all contradictions and … based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality”? In this inquiry, Douglass’s new role as a conscience of the country became clarified. His leadership had always been through words and persuasion, written and oratorical. How, now that the war was over, would he employ his incomparable voice?

From the beginning, Reconstruction had faced three paramount questions: Who would rule in the South (defeated ex-Confederates or the victorious North?); who would rule in Washington, D.C. (Congress or the president?); and what were the meanings and dimensions of Black freedom? As of his writing in December, Douglass declared that nothing could yet be “considered final.” After ferocious debates, Congress had enacted the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and passed the Fourteenth Amendment, the latter still subject to ratification by three-quarters of the state legislatures. Violent anti-Black riots had occurred in Memphis and New Orleans that spring and summer, killing at least 48 people in the first city and at least 38 in the second. Much had been done to secure emancipation, but all remained in abeyance, awaiting legislation, human persuasion, and acts of political will.

As Douglass was writing, two visions of Reconstruction vied for national dominance in the fall elections. President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, favored a policy of a lenient restoration, a plan that allowed for no Black civil and political rights and admitted the southern states back into the Union as quickly as possible. The Republican leadership of the House and the Senate, however, demanded a slower, harsher, and more transformative Reconstruction, a process that would establish state governments in the South that were more democratic. Black civil and political rights and enforcement mechanisms in federal law formed the backbone of these “Radical Republican” regimes.

Douglass was at this juncture a Radical Republican in the spirit of Thaddeus Stevens , the congressman from Pennsylvania who led the effort to impeach Johnson. Like Stevens, Douglass argued vehemently that Johnson had to be countered and thwarted by any legal means necessary or the promise of emancipation would fail. Douglass believed at the end of 1866 that, though only at its vulnerable beginning, the United States had been reinvented by war and by new egalitarian impulses rooted in emancipation. His essay is, therefore, full of radical brimstone, cautious hope, and a thoroughly new vision of constitutional authority. In careful but clear terms, he described Reconstruction as a revolution that would “cause Northern industry, Northern capital, and Northern civilization to flow into the South, and make a man from New England as much at home in Carolina as elsewhere in the Republic.” In short, he sought an overturning of history, the expansion of human rights forged from the fact of African American freedom—and from an idealism that soon would be sorely tested. Revolutions may or may not go backwards, but they surely give no rest to those who lead them.

David W. Blight is the Sterling Professor of American History at Yale and the author, most recently, of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom .

RECONSTRUCTION by FREDERICK DOUGLASS

The assembling of the Second Session of the Thirty-ninth Congress may very properly be made the occasion of a few earnest words on the already much-worn topic of reconstruction.

Seldom has any legislative body been the subject of a solicitude more intense, or of aspirations more sincere and ardent. There are the best of reasons for this profound interest. Questions of vast moment, left undecided by the last session of Congress, must be manfully grappled with by this. No political skirmishing will avail. The occasion demands statesmanship. 1

Whether the tremendous war so heroically fought and so victoriously ended shall pass into history a miserable failure, barren of permanent results,—a scandalous and shocking waste of blood and treasure,—a strife for empire, as Earl Russell characterized it, of no value to liberty or civilization,—an attempt to re-establish a Union by force, which must be the merest mockery of a Union,—an effort to bring under Federal authority States into which no loyal man from the North may safely enter, and to bring men into the national councils who deliberate with daggers and vote with revolvers, and who do not even conceal their deadly hate of the country that conquered them; or whether, on the other hand, we shall, as the rightful reward of victory over treason, 2 have a solid nation, entirely delivered from all contradictions and social antagonisms, based upon loyalty, liberty, and equality, must be determined one way or the other by the present session of Congress.

The last session really did nothing which can be considered final as to these questions. The Civil Rights Bill and the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the proposed constitutional amendments, with the amendment already adopted and recognized as the law of the land, do not reach the difficulty, and cannot, unless the whole structure of the government is changed from a government by States to something like a despotic central government, with power to control even the municipal regulations of States, and to make them conform to its own despotic will. While there remains such an idea as the right of each State to control its own local affairs,—an idea, by the way, more deeply rooted in the minds of men of all sections of the country than perhaps any one other political idea,—no general assertion of human rights can be of any practical value. To change the character of the government at this point is neither possible nor desirable. All that is necessary to be done is to make the government consistent with itself, and render the rights of the States compatible with the sacred rights of human nature. 3

The arm of the Federal government is long, but it is far too short to protect the rights of individuals in the interior of distant States. They must have the power to protect themselves, or they will go unprotected, spite of all the laws the Federal government can put upon the national statute-book.

Slavery, like all other great systems of wrong, founded in the depths of human selfishness, and existing for ages, has not neglected its own conservation. It has steadily exerted an influence upon all around it favorable to its own continuance. And to-day it is so strong that it could exist, not only without law, but even against law. Custom, manners, morals, religion, are all on its side everywhere in the South; and when you add the ignorance and servility of the ex-slave to the intelligence and accustomed authority of the master, you have the conditions, not out of which slavery will again grow, but under which it is impossible for the Federal government to wholly destroy it, unless the Federal government be armed with despotic power, to blot out State authority, and to station a Federal officer at every cross-road. This, of course, cannot be done, and ought not even if it could. The true way and the easiest way is to make our government entirely consistent with itself, and give to every loyal citizen the elective franchise,—a right and power which will be ever present, and will form a wall of fire for his protection. 4

One of the invaluable compensations of the late Rebellion is the highly instructive disclosure it made of the true source of danger to republican government. Whatever may be tolerated in monarchical and despotic governments, no republic is safe that tolerates a privileged class, or denies to any of its citizens equal rights and equal means to maintain them. What was theory before the war has been made fact by the war.

There is cause to be thankful even for rebellion. It is an impressive teacher, though a stern and terrible one. In both characters it has come to us, and it was perhaps needed in both. It is an instructor never a day before its time, for it comes only when all other means of progress and enlightenment have failed. Whether the oppressed and despairing bondman, no longer able to repress his deep yearnings for manhood, or the tyrant, in his pride and impatience, takes the initiative, and strikes the blow for a firmer hold and a longer lease of oppression, the result is the same,—society is instructed, or may be. 5

Such are the limitations of the common mind, and so thoroughly engrossing are the cares of common life, that only the few among men can discern through the glitter and dazzle of present prosperity the dark outlines of approaching disasters, even though they may have come up to our very gates, and are already within striking distance. The yawning seam and corroded bolt conceal their defects from the mariner until the storm calls all hands to the pumps. Prophets, indeed, were abundant before the war; but who cares for prophets while their predictions remain unfulfilled, and the calamities of which they tell are masked behind a blinding blaze of national prosperity? 6

It is asked, said Henry Clay, on a memorable occasion, Will slavery never come to an end? That question, said he, was asked fifty years ago, and it has been answered by fifty years of unprecedented prosperity. Spite of the eloquence of the earnest Abolitionists,—poured out against slavery during thirty years,—even they must confess, that, in all the probabilities of the case, that system of barbarism would have continued its horrors far beyond the limits of the nineteenth century but for the Rebellion, and perhaps only have disappeared at last in a fiery conflict, even more fierce and bloody than that which has now been suppressed.

It is no disparagement to truth, that it can only prevail where reason prevails. War begins where reason ends. The thing worse than rebellion is the thing that causes rebellion. What that thing is, we have been taught to our cost. It remains now to be seen whether we have the needed courage to have that cause entirely removed from the Republic. At any rate, to this grand work of national regeneration and entire purification Congress must now address itself, with full purpose that the work shall this time be thoroughly done. 7 The deadly upas, root and branch, leaf and fibre, body and sap, must be utterly destroyed. The country is evidently not in a condition to listen patiently to pleas for postponement, however plausible, nor will it permit the responsibility to be shifted to other shoulders. Authority and power are here commensurate with the duty imposed. There are no cloud-flung shadows to obscure the way. Truth shines with brighter light and intenser heat at every moment, and a country torn and rent and bleeding implores relief from its distress and agony.

If time was at first needed, Congress has now had time. All the requisite materials from which to form an intelligent judgment are now before it. Whether its members look at the origin, the progress, the termination of the war, or at the mockery of a peace now existing, they will find only one unbroken chain of argument in favor of a radical policy of reconstruction. For the omissions of the last session, some excuses may be allowed. A treacherous President stood in the way; and it can be easily seen how reluctant good men might be to admit an apostasy which involved so much of baseness and ingratitude. 8 It was natural that they should seek to save him by bending to him even when he leaned to the side of error. But all is changed now. Congress knows now that it must go on without his aid, and even against his machinations. The advantage of the present session over the last is immense. Where that investigated, this has the facts. Where that walked by faith, this may walk by sight. Where that halted, this must go forward, and where that failed, this must succeed, giving the country whole measures where that gave us half-measures, merely as a means of saving the elections in a few doubtful districts. That Congress saw what was right, but distrusted the enlightenment of the loyal masses; but what was forborne in distrust of the people must now be done with a full knowledge that the people expect and require it. The members go to Washington fresh from the inspiring presence of the people. In every considerable public meeting, and in almost every conceivable way, whether at court-house, school-house, or cross-roads, in doors and out, the subject has been discussed, and the people have emphatically pronounced in favor of a radical policy. Listening to the doctrines of expediency and compromise with pity, impatience, and disgust, they have everywhere broken into demonstrations of the wildest enthusiasm when a brave word has been spoken in favor of equal rights and impartial suffrage. Radicalism, so far from being odious, is now the popular passport to power. The men most bitterly charged with it go to Congress with the largest majorities, while the timid and doubtful are sent by lean majorities, or else left at home. The strange controversy between the President and Congress, at one time so threatening, is disposed of by the people. The high reconstructive powers which he so confidently, ostentatiously, and haughtily claimed, have been disallowed, denounced, and utterly repudiated; while those claimed by Congress have been confirmed.

Of the spirit and magnitude of the canvass nothing need be said. The appeal was to the people, and the verdict was worthy of the tribunal. Upon an occasion of his own selection, with the advice and approval of his astute Secretary, soon after the members of Congress had returned to their constituents, the President quitted the executive mansion, sandwiched himself between two recognized heroes,—men whom the whole country delighted to honor,—and, with all the advantage which such company could give him, stumped the country from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, 9 advocating everywhere his policy as against that of Congress. It was a strange sight, and perhaps the most disgraceful exhibition ever made by any President; but, as no evil is entirely unmixed, good has come of this, as from many others. Ambitious, unscrupulous, energetic, indefatigable, voluble, and plausible,—a political gladiator, ready for a “set-to” in any crowd,—he is beaten in his own chosen field, and stands to-day before the country as a convicted usurper, a political criminal, guilty of a bold and persistent attempt to possess himself of the legislative powers solemnly secured to Congress by the Constitution. No vindication could be more complete, no condemnation could be more absolute and humiliating. Unless reopened by the sword, as recklessly threatened in some circles, this question is now closed for all time.

Without attempting to settle here the metaphysical and somewhat theological question (about which so much has already been said and written), whether once in the Union means always in the Union,—agreeably to the formula, Once in grace always in grace,—it is obvious to common sense that the rebellious States stand to-day, in point of law, precisely where they stood when, exhausted, beaten, conquered, they fell powerless at the feet of Federal authority. 10 Their State governments were overthrown, and the lives and property of the leaders of the Rebellion were forfeited. In reconstructing the institutions of these shattered and overthrown States, Congress should begin with a clean slate, and make clean work of it. Let there be no hesitation. It would be a cowardly deference to a defeated and treacherous President, if any account were made of the illegitimate, one-sided, sham governments hurried into existence for a malign purpose in the absence of Congress. These pretended governments, which were never submitted to the people, and from participation in which four millions of the loyal people were excluded by Presidential order, should now be treated according to their true character, as shams and impositions, and supplanted by true and legitimate governments, in the formation of which loyal men, black and white, shall participate.

It is not, however, within the scope of this paper to point out the precise steps to be taken, and the means to be employed. The people are less concerned about these than the grand end to be attained. They demand such a reconstruction as shall put an end to the present anarchical state of things in the late rebellious States,—where frightful murders and wholesale massacres are perpetrated in the very presence of Federal soldiers. This horrible business they require shall cease. 11 They want a reconstruction such as will protect loyal men, black and white, in their persons and property; such a one as will cause Northern industry, Northern capital, and Northern civilization to flow into the South, and make a man from New England as much at home in Carolina as elsewhere in the Republic. No Chinese wall can now be tolerated. The South must be opened to the light of law and liberty, and this session of Congress is relied upon to accomplish this important work.

The plain, common-sense way of doing this work, as intimated at the beginning, is simply to establish in the South one law, one government, one administration of justice, one condition to the exercise of the elective franchise, for men of all races and colors alike. This great measure is sought as earnestly by loyal white men as by loyal blacks, and is needed alike by both. Let sound political prescience but take the place of an unreasoning prejudice, and this will be done.

Men denounce the negro for his prominence in this discussion; but it is no fault of his that in peace as in war, that in conquering Rebel armies as in reconstructing the rebellious States, the right of the negro is the true solution of our national troubles. The stern logic of events, which goes directly to the point, disdaining all concern for the color or features of men, has determined the interests of the country as identical with and inseparable from those of the negro.

The policy that emancipated and armed the negro—now seen to have been wise and proper by the dullest—was not certainly more sternly demanded than is now the policy of enfranchisement. If with the negro was success in war, and without him failure, so in peace it will be found that the nation must fall or flourish with the negro. 12

Fortunately, the Constitution of the United States knows no distinction between citizens on account of color. Neither does it know any difference between a citizen of a State and a citizen of the United States. Citizenship evidently includes all the rights of citizens, whether State or national. If the Constitution knows none, it is clearly no part of the duty of a Republican Congress now to institute one. The mistake of the last session was the attempt to do this very thing, by a renunciation of its power to secure political rights to any class of citizens, with the obvious purpose to allow the rebellious States to disfranchise, if they should see fit, their colored citizens. This unfortunate blunder must now be retrieved, and the emasculated citizenship given to the negro supplanted by that contemplated in the Constitution of the United States, which declares that the citizens of each State shall enjoy all the rights and immunities of citizens of the several States,—so that a legal voter in any State shall be a legal voter in all the States.

This article appears in the December 2023 print edition with the headline “The Annotated Frederick Douglass.”

The Confounding Truth About Frederick Douglass

His champions now span the ideological spectrum, but left and right miss the tensions in his views.

It is difficult to imagine a more remarkable story of self-determination and advancement than the life of Frederick Douglass. Emblematic of the depths from which he rose is the pall of uncertainty that shrouded his origins. For a long time he believed that he had been born in 1817. Then, in 1877, during a visit to a former master in Maryland, Douglass was told that he had actually been born in 1818. Douglass could barely recall his mother, who had been consigned to different households from the one where her baby lived. And he never discovered the identity of his father, who was likely a white man. “Genealogical trees,” Douglass mordantly observed, “do not flourish among slaves.”

Douglass fled enslavement in 1838, and with the assistance of abolitionists, he cultivated his prodigious talents as an orator and a writer. He produced a score of extraordinary speeches. The widely anthologized “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” delivered in 1852, is the most damning critique of American hypocrisy ever uttered:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? … a day that reveals to him … the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham … your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery … There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”

He wrote analyses of court opinions that deservedly appear in constitutional-law casebooks. He published many arresting columns in magazines and newspapers, including several that he started. He also wrote three exceptional memoirs, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). The most celebrated black man of his era, Douglass became the most photographed American of any race in the 19th century. He was the first black person appointed to an office requiring senatorial confirmation; in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes nominated him to be the marshal of the District of Columbia.

Throughout his life, however, Douglass repeatedly fell victim to the brutalizations and insults commonly experienced by African Americans of his time. As a slave, he suffered at the hands of a vicious “nigger breaker” to whom he was rented. He fled to the “free” North, only to have his work as a maritime caulker thwarted by racist white competitors. As a traveling evangelist for abolitionism, he was repeatedly ejected from whites-only railroad cars, restaurants, and lodgings. When he died, an admiring obituary in The New York Times suggested that Douglass’s “white blood” accounted for his “superior intelligence.” After his death, his reputation declined precipitously alongside the general standing of African Americans in the age of Jim Crow.

N ow everyone wants a piece of Frederick Douglass . When a statue memorializing him was unveiled at the United States Capitol in 2013, members of the party of Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell sported buttons that read frederick douglass was a republican . More recently, the Republican National Committee issued a statement joining President Donald Trump “in honoring Douglass’ lifelong dedication to the principles that define [the Republican] Party and enrich our nation.” Across the ideological divide, former President Barack Obama has lauded Douglass, as has the leftist intellectual Cornel West. New books about Douglass have appeared with regularity of late, and are now joined by David W. Blight’s magnificently expansive and detailed Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

A history professor at Yale who has long been a major contributor to scholarship on Douglass, slavery, and the Civil War, Blight portrays Douglass unequivocally as a hero while also revealing his weaknesses. Blight illuminates important facets of 19th-century political, social, and cultural life in America, including the often overlooked burdens borne by black women. At the same time, he speaks to urgent, contemporary concerns such as Black Lives Matter. Given the salience of charges of cultural misappropriation, griping about his achievement would be unsurprising: Blight is a white man who has written the leading biography of the most outstanding African American of the 19th century. His sensitive, careful, learned, creative, soulful exploration of Douglass’s grand life, however, transcends his own identity.

In the wake of Douglass’s death in 1895, it was African Americans who kept his memory alive. Booker T. Washington wrote a biography in 1906. The historian Benjamin Quarles wrote an excellent study in 1948. White historians on the left also played a key role in protecting Douglass from oblivion, none more usefully than Philip Foner, a blacklisted Marxist scholar (and uncle of the great historian Eric Foner), whose carefully edited collection of Douglass’s writings remains essential reading. But in “mainstream”—white, socially and politically conventional—circles, Douglass was widely overlooked. In 1962, the esteemed literary critic Edmund Wilson published Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War , a sprawling (and lavishly praised) commentary on writings famous and obscure that omitted Douglass, and virtually all the other black literary figures of the period.

Keenly attuned to the politics of public memory, Blight shows that the current profusion of claims on Douglass’s legacy bears close scrutiny: Claimants have a way of overlooking features of his complex persona that would be embarrassing for them to acknowledge. Conservatives praise his individualism, which sometimes verged on social Darwinism. They also herald Douglass’s stress on black communal self-help, his antagonism toward labor unions, and his strident defense of men’s right to bear arms. They tiptoe past his revolutionary rage against the United States during his early years as an abolitionist. “I have no patriotism,” he thundered in 1847. “I cannot have any love for this country … or for its Constitution. I desire to see it overthrown as speedily as possible.” Radical as to ends, he was also radical as to means. He justified the violence deployed when a group of abolitionists tried to liberate a fugitive slave from a Boston jail and killed a deputy U.S. marshal in the process. Similarly, he assisted and praised John Brown, the insurrectionist executed for murder and treason in Virginia in 1859.

Many conservatives who claim posthumous alliance with Douglass would abandon him if they faced the prospect of being publicly associated with the central features of his ideology. After all, he championed the creation of a strong post–Civil War federal government that would extend civil and political rights to the formerly enslaved; protect those rights judicially and, if necessary, militarily; and undergird the former slaves’ new status with education, employment, land, and other resources, to be supplied by experimental government agencies. Douglass objected to what he considered an unseemly willingness to reconcile with former Confederates who failed to sincerely repudiate secession and slavery. He expressed disgust, for example, at the “bombastic laudation” accorded to Robert E. Lee upon the general’s death in 1870. Blight calls attention to a speech resonant with current controversies:

We are sometimes asked in the name of patriotism to forget the merits of [the Civil War], and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life, and those who struck to save it—those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty … May my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I forget the difference between the parties to that … bloody conflict.

The progressive tradition of championing Douglass runs deeper, not surprisingly, than the conservative adoption of him. As an abolitionist, a militant antislavery Republican, and an advocate for women’s rights, he allied himself with three of the greatest dissident progressive formations in American history. Activists on the left should feel comfortable seeking to appropriate the luster of his authority for many of their projects —solicitude for refugees, the elevation of women, the advancement of unfairly marginalized racial minorities. No dictum has been more ardently repeated by progressive dissidents than his assertion that “if there is no struggle there is no progress … Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

But certain aspects of Douglass’s life would, if more widely known, cause problems for many of his contemporary admirers on the left, a point nicely made in Blight’s biography as well as in Waldo E. Martin Jr.’s The Mind of Frederick Douglass . A Republican intra-party contest in an 1888 congressional election in Virginia pitted John Mercer Langston, a progressive black jurist (who had served as the first dean of Howard University Law School), against R. W. Arnold, a white conservative sponsored by a white party boss (who was a former Confederate general). Douglass supported Arnold, and portrayed his decision as high-minded. “The question of color,” he said, “should be entirely subordinated to the greater questions of principles and party expediency.” In fact, what had mainly moved Douglass was personal animosity; he and Langston had long been bitter rivals. Langston was hardly a paragon, but neither was Douglass. Sometimes he could be a vain, selfish, opportunistic jerk, capable of subordinating political good to personal pique.

Douglass promised that he would never permit his desire for a government post to mute his anti-racism. He broke that promise. When Hayes nominated him to be D.C. marshal, the duties of the job were trimmed. Previously the marshal had introduced dignitaries on state occasions. Douglass was relieved of that responsibility. Racism was the obvious reason for the change, but Douglass disregarded the slight and raised no objection. Some observers derided him for his acquiescence. He seemed to think that the benefit to the public of seeing a black man occupy the post outweighed the benefit that might be derived from staging yet another protest. But especially as he aged, Douglass lapsed into the unattractive habit of conflating what would be good for him with what would be good for blacks, the nation, or humanity. In this instance, his detractors were correct: He had permitted himself to be gagged by the prospect of obtaining a sinecure.

Douglass was also something of an imperialist. He accepted diplomatic positions under Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, in 1871, and Benjamin Harrison, in 1889, that entailed assisting the United States in pressuring Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) to allow itself to become annexed and Haiti to cede territory. Douglass acted with good intentions, aiming to stabilize and elevate these black Caribbean countries by tying them to the United States in its slavery-free, post–Civil War incarnation. He liked the idea of Santo Domingo becoming a new state, thereby adding to the political muscle in America of people of African descent, a prospect that frightened or disgusted some white supremacists. When Douglass felt that his solicitude for people of color in the Caribbean was being decisively subordinated to exploitative business and militaristic imperatives, he resigned. But here again, Douglass demonstrated (along with a sometimes condescending attitude toward his Caribbean hosts) a yearning for power, prestige, and recognition from high political authorities that confused and diluted his more characteristic ideological impulses.

Douglass is entitled to and typically receives an honored place in any pantheon dedicated to heroes of black liberation. He also poses problems, however, for devotees of certain brands of black solidarity. White abolitionists were key figures in his remarkable journey to national and international prominence. Without their assistance, he would not have become the symbol of oppressed blackness in the minds of antislavery whites, and without the prestige he received from his white following, he would not have become black America’s preeminent spokesman. That whites were so instrumental in furthering Douglass’s career bothers black nationalists who are haunted by the specter of white folks controlling or unduly influencing putative black leaders.

Recommended Reading

My race problem.

An Appeal to Congress for Impartial Suffrage

Frederick douglass: american lion.

Douglass’s romantic life has stirred related unease, a subject Blight touches on delicately, exhibiting notable interest in and sympathy for his hero’s first wife . A freeborn black woman, Anna Murray helped her future husband escape enslavement and, after they married, raised five children with him and dutifully maintained households that offered respite between his frequent, exhausting bouts of travel. Their marriage seemed to nourish them both in certain respects, but was profoundly lacking in others. Anna never learned to read or write, which severely limited the range of experience that the two of them could share. Two years after Anna died in 1882, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a Mount Holyoke College–educated white former abolitionist 20 years his junior. They tried to keep the marriage quiet; even his children were unaware of it until the union was a done deal. But soon news of it emerged and controversy ensued. The marriage scandalized many whites, including Helen’s father, who rejected his daughter completely. But the marriage outraged many blacks as well. The journalist T. Thomas Fortune noted that “the colored ladies take [Douglass’s marriage] as a slight, if not an insult, to their race and their beauty.” Many black men were angered, too. As one put it, “We have no further use for [Douglass] as a leader. His picture hangs in our parlor, we will hang it in the stable.” For knowledgeable black nationalists, Douglass’s second marriage continues to vex his legacy. Some give him a pass for what they perceive as an instance of apostasy, while others remain unforgiving.

That Douglass is celebrated so widely is a tribute most of all to the caliber and courage of his work as an activist, a journalist, a memoirist, and an orator. It is a testament as well to those, like Blight, who have labored diligently to preserve the memory of his extraordinary accomplishments. Ironically, his popularity is also due to ignorance. Some who commend him would probably cease doing so if they knew more about him. Frederick Douglass was a whirlwind of eloquence, imagination, and desperate striving as he sought to expose injustice and remedy its harms. All who praise him should know that part of what made him so distinctive are the tensions—indeed the contradictions—that he embraced.

This article appears in the December 2018 print edition with the headline “The Confounding Truth About Frederick Douglass.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Digital Edition

- Papers Project

- Image Gallery

- More Douglass Resources

- Project Team

- Editorial Process

- Repositories

- New North Star

- Hoosiers Reading Frederick Douglass Together

- Publications

Welcome to The Frederick Douglass Papers

Born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, Frederick Douglass (1818-95) became one of the most influential human rights activist of the nineteenth century, as well as an internationally acclaimed statesmen, orator, editor, and author. The Frederick Douglass Papers collects, edits, and publishes in books and online the speeches, letters, autobiographies, and other writings of Frederick Douglass. The project's primary aim has been to make the surviving works by this African American figure accessible to a broad audience, much as similar projects have done for the papers of notable white historical and literary figures.

Explore Frederick Douglass Papers Online

The Frederick Douglass Papers Digital Edition offers more than 800 documents from the project's volumes. This online resource will ultimately contain all of the content of the multi-volume Yale University Press print edition of Douglass’s speeches, autobiographies, correspondence, other writings, all the unpublished correspondence, as well as other unpublished materials including editorial and speech tests.

Explore the Digital Edition

Do you want to help transcribe Frederick Douglass documents that will eventually be included in the digital edition here? We have documents available in FromThePage, a crowdsourcing platform you can find HERE

"If there is no struggle there is no progress…. Power concedes nothing without a demand, It never did and it never will."

From the speech, "The Significance of Emancipation in the West Indies," 3 August 1857, Douglass Papers, ser. 1, 3:204.

New Release: Journalism and Other Writings, Volume 1

The first volume of the Journalism and Other Writings Series was published by Yale University Press in late 2021. Launching the fourth series of The Frederick Douglass Papers , designed to introduce readers to the broadest range of Frederick Douglass’s writing, this volume contains sixty-seven pieces by Douglass, including articles written for the North American Review and the New York Independent , as well as unpublished poems, book transcriptions, and travel diaries. Spanning from the 1840s to the 1890s, the documents reproduced in this volume demonstrate how Douglass’s writing evolved over the five decades of his public life. Where his writing for publication was concerned mostly with antislavery advocacy, his unpublished works give readers a glimpse into his religious and personal reflections. The writings are organized chronologically and accompanied by annotations offering biographical information as well as explanations of events mentioned and literary or historical allusions.

Coming Soon: Correspondence, Volume 3

The third volume of the Correspondence Series is now in press and will be published in 2022. This volume reproduces selected correspondence to and from Douglass from the years 1866 to 1880. It produces letters discussing the crucial issues of the Reconstruction Era; Douglass’s career as editor of the Washington (D.C.) New National Era , president of the Freedmen’s Savings Bank, marshal of the District of Columbia, and his active involvement in not just politics but reform causes such as women’s rights. The texts of these letters are accompanied by detailed annotation making Douglass life and times accessible to modern readers.

"I have never yet been able to find one consideration, one argument, or suggestion in favor of man's right to participate in civil government which did not equally apply to the right of women."

Autobiography: Life and Times , 1881, p. 371.

Teacher Seminars Online : Study with eminent historians this summer without leaving home!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

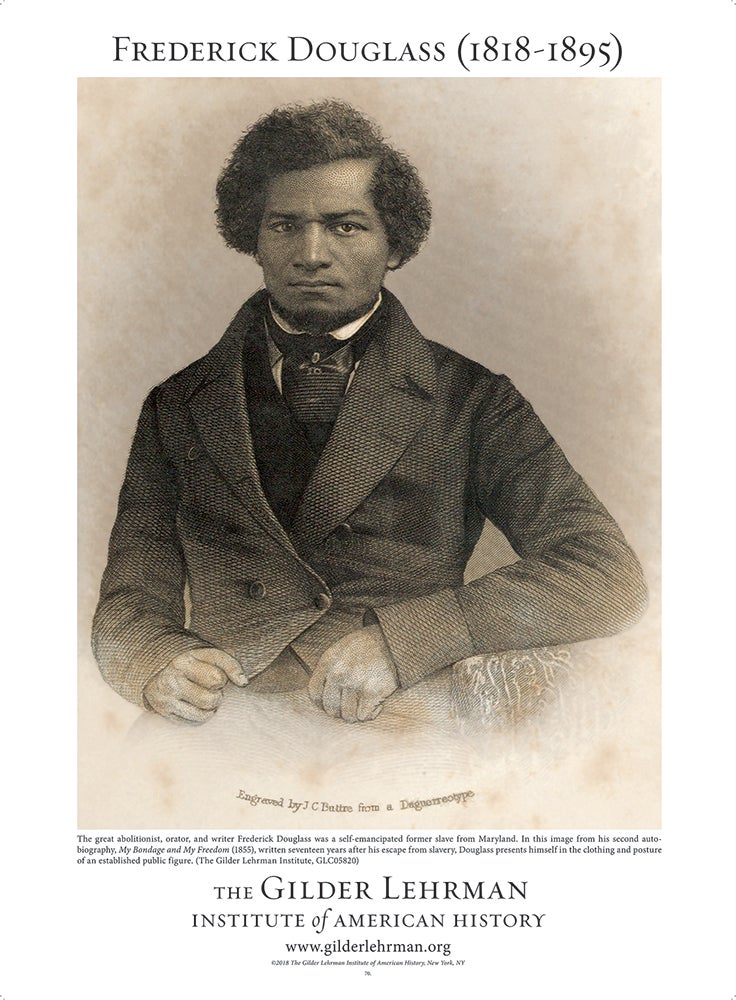

Frederick Douglass Resources

Posted by gilder lehrman staff on monday, 02/04/2019.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute is fortunate to have several original Frederick Douglass documents in its Collection and has amassed many scholarly responses to the life and work of the escaped enslaved man turned abolitionist leader.

The Primary Source Spotlight shines on several of Frederick Douglass’s letters:

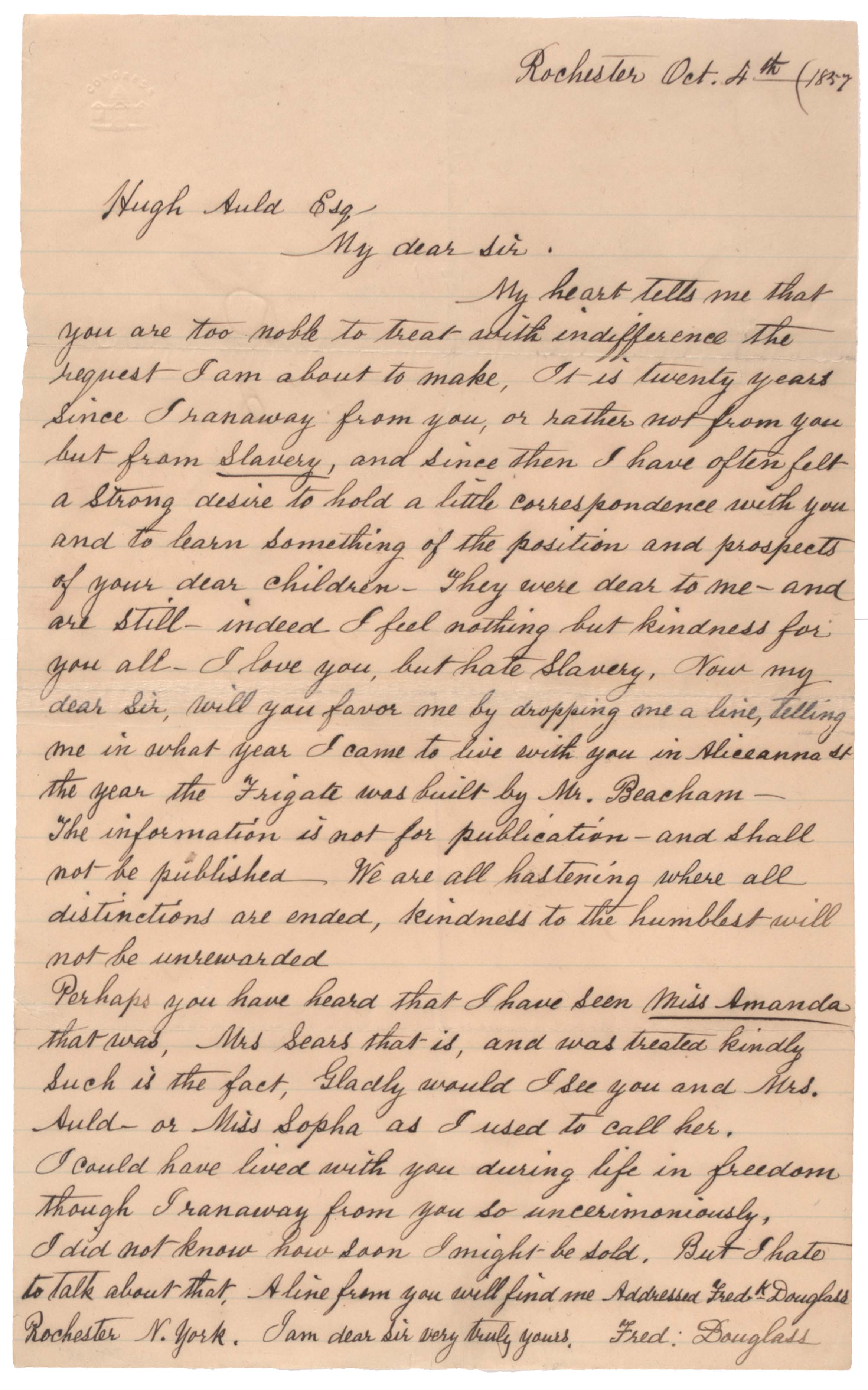

- In 1860, Frederick Douglass wrote to his former owner to say he loved him but hated slavery.

- In 1870, Douglass wrote to Thomas Burnett Pugh, a former abolitionist about the racism he encountered in the North .

- In 1880, Douglass wrote a tribute to Abraham Lincoln.

- In 1887, Douglass attacked the unwritten new laws of the South and the Jim Crow laws that continued to marginialize and oppress African Americans.

- In 1888, Douglass wrote about the disfranchisement of black voters .

In “Frederick Douglass at 200,” the winter of 2018 issue of History Now , the online journal of the Gilder Lehrman Institute, we featured five major articles by leading scholars in celebration of Douglass’s 200th birthday.

You can also find additional essays about significant events in and documents from Frederick Douglass’s life:

- “ Your Late Lamented Husband ”: A Letter from Frederick Douglass to Mary Todd Lincoln from 1865, explored in an essay by David W. Blight

- Admiration and Ambivalence: Frederick Douglass and John Brown , an essay by David W. Blight focusing on correspondence between Douglass and other abolitionists , detailing the relationship between Douglass and Brown in the leadup to and aftermath of Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry.

- “The Merits of This Fearful Conflict”: Douglass on the Causes of the Civil War , an essay by David W. Blight focusing on Douglass’s remarks at Arlington National Cemetery in 1871 , reminding the assembled listeners that the Confederacy had fought the Civil War to preserve slavery.

- “Hidden Practices”: Frederick Douglass on Segregation and Black Achievement, 1887 , an essay by Edward L. Ayers focusing on Douglass’s letter to an unknown recipient from 1887 about the struggle in the South.

You can learn more about the former slave, abolitionist, and orator through one of our Online Exhibitions, “Frederick Douglass from Slavery to Freedom: The Journey to New York City” and “Activist for Equality: Frederick Douglass at 200.”

The Gilder Lehrman offers a Frederick Douglass Traveling Exhibition for education- or community-based organizations in the continental United States. Among the highlights are a broadside entitled Slave Market of America from the American Anti-Slavery Society, passages from Douglass’s first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave , and a letter from Douglass to Hugh Auld, whose family held Douglass as a slave.

In partnership with the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University, the Institute awards the annual Frederick Douglass Book Prize of $25,000 for an outstanding nonfiction book in English on the subject of slavery, resistance, and/or abolition. 2018 was the 20th anniversary of the Prize, which has been awarded to co-winners Erica Armstrong Dunbar for Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (37Ink/Atria Books) and Tiya Miles for The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits (The New Press). The award ceremony will be held on February 28, 2019, at the Yale Club of New York City.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

77 Frederick Douglass Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best frederick douglass topic ideas & essay examples, ✅ most interesting frederick douglass topics to write about, ❓ frederick douglass essay questions.

Many students find writing a Frederick Douglass essay a problematic task. If you’re one of them, then check this article to learn the essential do’s and don’ts of academic writing:

- Do structure your essay. Here’s the thing: when you arrange the key points of your paper in a logical order, it makes it easier for your readers to read the essay and get the message across. Eliminate unnecessary words and phrases: keep continually asking yourself whether you need a particular construction in the paper and if it clear.

- Do put your Frederick Douglass essay thesis statement in the intro. A thesis statement is a mandatory part of the paper introduction. Use it to reveal the central idea of your assignment. Think of what you’re going to write about: slavery, its effect of slaveholders, freedom, etc. Avoid placing a thesis at the beginning of the introductory paragraph.

- Do use citations. If you’re going to use a quote, provide examples from a book, always use references. Doing this would help your essay sound more convincing and also will help you avoid accusations of plagiarism. Make sure that you stick to the required citation style.

- Do use the present tense in your literature and rhetorical analysis. The secret is that present tense will make your paper more engaging.

- Do stick to Frederick Douglass essay prompt. If your paper has a prompt, make sure that you’ve covered all the aspects of it.

- Don’t use too complicated sentences. Using unnecessary complex sentences will only increase of grammar and1 style mistakes. Instead, make your writing simple and readable.

- Don’t overload your paper with facts and quotes. Some Frederick Douglass essay topics require more quotes than other papers. However, you should avoid turning your paper in one complete quote. Narrow the topic and use only the most relevant citations to prove your statements.

- Don’t use slang and informal language. You’re writing an essay, not a letter to your friend. So stick to the academic writing style and use appropriate language. Avoid using clichés.

- Don’t underestimate the final paper revision. Regardless of what Frederick Douglass essay titles you choose for your assignment, don’t let mistakes and typos spoil your writing. There are plenty of spelling and grammar checking tools. Use them to polish your paper. However, don’t underrate human manual proofread. Ask your friend or relative to revise the text.

If you’re looking for Frederick Douglass essay questions, you can explore some sample ideas to use in your paper:

- How do you think, what did Frederick Douglass dreamed about?