- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

How speechwriters delve into a president's mind: Lots of listening, studying and becoming a mirror

- Oops! Something went wrong. Please try again later. More content below

WASHINGTON (AP) — Speechwriting, in one sense, is essentially being someone else’s mirror.

“You can try to find the right words,” said Dan Cluchey, a former speechwriter for President Joe Biden . “But ultimately, your job is to ensure that when the speech is done, that it has a reflection of the speaker.”

That concept is infinitely magnified in the role of the presidential speechwriter. Over the course of U.S. history, those aides have absorbed the personalities, the quirks, the speech cadences of the most powerful leader on the globe, capturing his thoughts for all manner of public remarks, from the mundane to the historic and most consequential.

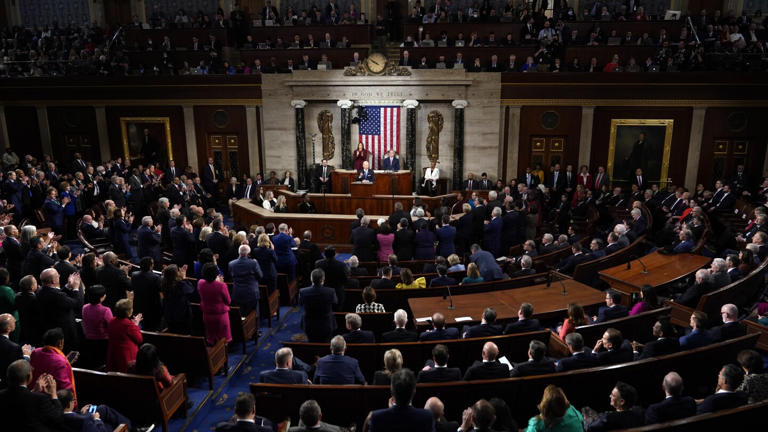

There are few times in a presidency that the art — and the rigorous, often painful process — of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union , when the vast array of a president’s policy aspirations and political messages come together in one, hour-plus carefully choreographed address at the Capitol. Biden will deliver the annual address on Thursday .

It’s a process that former White House speechwriters say take months, with untold lobbying and input from various federal agencies and others outside the president’s inner circle who are all working to ensure their favored proposals merit a mention. Speechwriters have the unenviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching them into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year.

It’s less elegant prose, more laundry list of policy ideas.

Amid all those formalities and constraints of a State of the Union address, there is also how a president executes the speech.

Biden’s biggest political liability remains his age (81) and voters’ questions about whether he is still up to the job (his doctor this past week declared him fit to serve ). His every word is watched by Republican operatives eager to capture any misspeak to plant doubt about Biden’s fitness among the public.

“This year, of course, is an election year. It also comes as there’s much more chatter about his age,” said Michael Waldman, who served as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton. “People are really going to be scrutinizing him for how he delivers the speech, as much as what he says.”

Biden will remain at Camp David through Tuesday and is expected to spend much of that time preparing for the State of the Union. Bruce Reed, the White House deputy chief of staff, accompanied Biden to the presidential retreat outside Washington on Friday evening.

The White House has said lowering costs, shoring up democracy and protecting women’s reproductive care will be among the topics that Biden will address on Thursday night.

Biden likely won’t top the list of the most talented presidential orators. He has thrived the most during small chance encounters with Americans, where interactions can be more off the cuff and intimate.

The plain-spoken Biden is known to hate Washington jargon and the alphabet soup of government acronyms, and he has challenged aides, when writing his remarks, to cut through the clutter and to get to the point with speed. Cluchey, who worked for Biden from 2018 to 2022, said the president was very engaged in the speech drafting process, all the way down to individual lines and words.

Biden can also come across as stiff at times when standing and reading from a teleprompter, but immediately loosens up and appears more comfortable when he switches to a hand-held microphone mid-remark. Biden has also learned to navigate a childhood stutter that he says helped him develop empathy for others facing similar challenges.

To become engrossed in another person’s voice, past presidential speechwriters list things that are critical. One is just doing a lot of listening to the principal, to get a sense of his rhythms and how he uses language.

Lots of direct conversation with the president is key, to try and get inside the commander in chief's thinking and how that leader frames arguments and make their case.

“This is not an act of impression, where you’re simply just trying to get the accent down,” said Jeff Shesol, another former Clinton speechwriter. “What you really are learning to do and need to learn to do -– this is true of speechwriters in any role, but particularly for a president –- is to understand not just how he sounds, but how he thinks.”

Shesol added: “You’re absorbing not just the rhythms and cadences of speech, but you’re absorbing a worldview.”

Then there is always the matter of the speech-giver going rogue.

Biden is often candid, and White House aides are sometimes left to clean up and clarify what he said in unvarnished moments. But other times when he deviates from the script, it ends up being an improvement on what his aides had scripted.

Take last year’s State of the Union . Biden had launched into an attack prepared in advance against some Republicans who were insisting on requiring renewal votes on popular programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which would effectively threaten their fate every five years.

That prompted heckling from Republicans and shouts of “Liar!” from the audience.

Biden immediately pivoted, egging on the Republicans to contact his office for a copy of the proposal and joking that he was enjoying their “conversion.”

“Folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the — off the books now, right? They’re not to be touched?” Biden continued. The crowd of lawmakers applauded. “All right. All right. We got unanimity!"

Speechwriters do try and prepare for such moments, particularly if a president is known to speak extemporaneously.

Shesol recalled that Clinton's speechwriters would draft remarks that were relatively spare, to account for him veering off on his own. The writers would write a clear structure into the speech that would allow Clinton to easily return to his prepared remarks once his riff was over.

“Clinton used to liken it to playing a jazz solo and then he’s going back to the score,” Waldman added.

Cluchey, when asked for his reaction when his former boss would go off-script, described it as a “ballet with several movements of, you know, panic, to ‘Wait a minute, this is actually very good,’ and then ‘Oh man, he really nailed it.’”

Biden is “at his best when he’s most authentically, most loosely, just speaking the plain truth,” Cluchey said. “The speechwriting process even at its best has strictures around it.”

Recommended Stories

Boban marjanović hilariously misses free throws on purpose to give clippers fans free chicken.

Boban Marjanović is a man of the people.

Yankees pitcher Fritz Peterson, infamous for trading wives with a teammate, dies at 82

Former New York Yankees left-hander Fritz Peterson died at the age of 82. He is probably best known exchanging wives with teammate Mike Kekich in the 1970s.

2024 Masters payouts: How much did Scottie Scheffler earn for his win at Augusta National?

The Masters has a record $20 million purse this year.

Nike responds to backlash over Team USA track kits, notes athletes can wear shorts

The new female track uniform looked noticeably skimpy at the bottom in one picture, which social media seized upon.

Rob Gronkowski's first pitch before the Red Sox's Patriots' Day game was typical Gronk

Never change, Gronk.

UFC 300: 'We're probably gonna get sued' after Arman Tsarukyan appeared to punch fan during walkout

'We'll deal with that Monday,' Dana White said about Arman Tsarukyan appearing to punch a fan during his UFC 300 walkout.

Mock Draft Monday with Daniel Jeremiah: Bears snag Odunze, Raiders grab a QB

It's another edition of 'Mock Draft Monday' on the pod and who better to have on then the face of NFL Network's draft coverage and a giant in the industry. Daniel Jeremiah joins Matt Harmon to discuss his mock draft methodology, what he's hearing about this year's draft class and shares his favorite five picks in his latest mock draft.

76ers' statue for Allen Iverson draws jokes, outrage due to misunderstanding: 'That was disrespectful'

Iverson didn't get a life-size statue. Charles Barkley and Wilt Chamberlain didn't either.

'Sasquatch Sunset' is so relentlessly gross that people are walking out of screenings. Star Jesse Eisenberg says the film was a ‘labor of love.’

“There are so many movies made for people who like typical things. This is not that," the film's star told Yahoo Entertainment.

GM is moving out of its Detroit headquarters towers

Something's happening with General Motors' headquarters buildings, and it may mean they'll no longer be GM's headquarters buildings.

Tesla layoffs hit high performers, some departments slashed, sources say

Tesla management told employees Monday that the recent layoffs -- which gutted some departments by 20% and even hit high performers -- were largely due to poor financial performance, a source familiar with the matter told TechCrunch. The layoffs were announced to staff just a week before Tesla is scheduled to report its first-quarter earnings. The move comes as Tesla has seen its profit margin narrow over the past several quarters, the result of an EV price war that has persisted for at least a year.

Travis Kelce receives his University of Cincinnati diploma, chugs a beer on stage

Nobody is going to change the Kelce brothers.

Report: USA basketball roster for Paris Olympics to feature LeBron James, Stephen Curry, Joel Embiid

USA Basketball is finalizing its roster for the upcoming Paris Olympics

Anthony Davis leaves Lakers season finale with back spasm, accuses Larry Nance Jr. of 'dangerous play'

Davis and head coach Darvin Ham are optimistic that Davis' latest injury won't sideline him for Tuesday's play-in game against the Pelicans.

Verne Lundquist signs off from the Masters: 'It's been an honor and a privilege'

Verne Lundquist ended a 40-year run at the Masters.

NBA Rookie Power Rankings 6.0: Victor Wembanyama finishes season at the top of the class

Here's a final look at Yahoo Sports' rookie rankings for the 2023-24 season.

WNBA Draft: Angel Reese drafted 7th overall by Sky

Reese is headed to Chicago.

The Spin: When to cut a big-name player in fantasy baseball

Many fantasy managers become too afraid of making a mistake, of making a wrong decision. Scott Pianowski explains why that fear is a detriment.

Why employers should (and have to) hire older workers

Roughly 1 in 5 Americans over 65 were employed in 2023, four times the number in the mid-80s. Employers are gradually recognizing the value of older workers and taking steps to retain them.

Here’s who will pay for Biden’s student loan cancellations

Cancelling student debt is a windfall for the borrowers who benefit, but taxpayers foot the bill.

How speechwriters delve into a president’s…

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

Daily e-Edition

Evening e-Edition

- Things to Do

- Top Workplaces

- Advertising

- Classifieds

Breaking News

Ct man charged with attempted murder, assault after allegedly stabbing partner multiple times, uncategorized, how speechwriters delve into a president’s mind: lots of listening, studying and becoming a mirror.

By SEUNG MIN KIM (Associated Press)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Speechwriting, in one sense, is essentially being someone else’s mirror.

“You can try to find the right words,” said Dan Cluchey, a former speechwriter for President Joe Biden. “But ultimately, your job is to ensure that when the speech is done, that it has a reflection of the speaker.”

That concept is infinitely magnified in the role of the presidential speechwriter. Over the course of U.S. history, those aides have absorbed the personalities, the quirks, the speech cadences of the most powerful leader on the globe, capturing his thoughts for all manner of public remarks, from the mundane to the historic and most consequential.

There are few times in a presidency that the art — and the rigorous, often painful process — of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union, when the vast array of a president’s policy aspirations and political messages come together in one, hour-plus carefully choreographed address at the Capitol. Biden will deliver the annual address on Thursday.

It’s a process that former White House speechwriters say take months, with untold lobbying and input from various federal agencies and others outside the president’s inner circle who are all working to ensure their favored proposals merit a mention. Speechwriters have the unenviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching them into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year.

It’s less elegant prose, more laundry list of policy ideas.

Amid all those formalities and constraints of a State of the Union address, there is also how a president executes the speech.

Biden’s biggest political liability remains his age (81) and voters’ questions about whether he is still up to the job (his doctor this past week declared him fit to serve ). His every word is watched by Republican operatives eager to capture any misspeak to plant doubt about Biden’s fitness among the public.

“This year, of course, is an election year. It also comes as there’s much more chatter about his age,” said Michael Waldman, who served as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton. “People are really going to be scrutinizing him for how he delivers the speech, as much as what he says.”

Biden will remain at Camp David through Tuesday and is expected to spend much of that time preparing for the State of the Union. Bruce Reed, the White House deputy chief of staff, accompanied Biden to the presidential retreat outside Washington on Friday evening.

The White House has said lowering costs, shoring up democracy and protecting women’s reproductive care will be among the topics that Biden will address on Thursday night.

Biden likely won’t top the list of the most talented presidential orators. He has thrived the most during small chance encounters with Americans, where interactions can be more off the cuff and intimate.

The plain-spoken Biden is known to hate Washington jargon and the alphabet soup of government acronyms, and he has challenged aides, when writing his remarks, to cut through the clutter and to get to the point with speed. Cluchey, who worked for Biden from 2018 to 2022, said the president was very engaged in the speech drafting process, all the way down to individual lines and words.

Biden can also come across as stiff at times when standing and reading from a teleprompter, but immediately loosens up and appears more comfortable when he switches to a hand-held microphone mid-remark. Biden has also learned to navigate a childhood stutter that he says helped him develop empathy for others facing similar challenges.

To become engrossed in another person’s voice, past presidential speechwriters list things that are critical. One is just doing a lot of listening to the principal, to get a sense of his rhythms and how he uses language.

Lots of direct conversation with the president is key, to try and get inside the commander in chief’s thinking and how that leader frames arguments and make their case.

“This is not an act of impression, where you’re simply just trying to get the accent down,” said Jeff Shesol, another former Clinton speechwriter. “What you really are learning to do and need to learn to do -– this is true of speechwriters in any role, but particularly for a president –- is to understand not just how he sounds, but how he thinks.”

Shesol added: “You’re absorbing not just the rhythms and cadences of speech, but you’re absorbing a worldview.”

Then there is always the matter of the speech-giver going rogue.

Biden is often candid, and White House aides are sometimes left to clean up and clarify what he said in unvarnished moments. But other times when he deviates from the script, it ends up being an improvement on what his aides had scripted.

Take last year’s State of the Union. Biden had launched into an attack prepared in advance against some Republicans who were insisting on requiring renewal votes on popular programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which would effectively threaten their fate every five years.

That prompted heckling from Republicans and shouts of “Liar!” from the audience.

Biden immediately pivoted, egging on the Republicans to contact his office for a copy of the proposal and joking that he was enjoying their “conversion.”

“Folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the — off the books now, right? They’re not to be touched?” Biden continued. The crowd of lawmakers applauded. “All right. All right. We got unanimity!”

Speechwriters do try and prepare for such moments, particularly if a president is known to speak extemporaneously.

Shesol recalled that Clinton’s speechwriters would draft remarks that were relatively spare, to account for him veering off on his own. The writers would write a clear structure into the speech that would allow Clinton to easily return to his prepared remarks once his riff was over.

“Clinton used to liken it to playing a jazz solo and then he’s going back to the score,” Waldman added.

Cluchey, when asked for his reaction when his former boss would go off-script, described it as a “ballet with several movements of, you know, panic, to ‘Wait a minute, this is actually very good,’ and then ‘Oh man, he really nailed it.’”

Biden is “at his best when he’s most authentically, most loosely, just speaking the plain truth,” Cluchey said. “The speechwriting process even at its best has strictures around it.”

More in Uncategorized

News | PHOTOS: Third Annual CGA Kickball Classic

Connecticut News | Bright fireball spotted in night sky over several states, including CT

SUBSCRIBER ONLY

Connecticut news | on a ct trail, a phone has no dial tone. it’s there to help hikers connect to long-lost friends and family.

Connecticut News | What are peer-run respite centers? Why some CT lawmakers are pushing for alternative to psychiatric facilities

Exploring the Craft of Presidential Speechwriting: A Glimpse into Crafting a President’s Voice

A t the heart of Washington’s political stage lies the art of presidential speechwriting, where a speechwriter’s task is to become a reflection of the President.

Dan Cluchey, who has penned speeches for President Joe Biden , explains that the central goal is to capture the President’s essence in the speech. This endeavor becomes even more critical when preparing for significant events like the State of the Union address.

Throughout American history, presidential speechwriters have tuned into the nuances of the President’s personality, communication style, and thought patterns to articulate his message to the nation and the world.

When a President prepares for the State of the Union, the speechwriting process comes under intense focus. This event consolidates a vast array of policy goals and political narratives into a single, elaborate presentation. President Biden is scheduled to deliver the annual address on Thursday , continuing this timeless tradition.

Months of preparation are invested in this process, with extensive input from various federal agencies and presidential advisors. The challenge for speechwriters lies in weaving many policy proposals into a seamless narrative that encapsulates the President’s vision.

Amidst this process, the President’s delivery of the speech is equally crucial. With questions surrounding Biden’s age and capability due to his being 81, his performance during the speech is under the microscope, magnified by election-year pressures and public scrutiny.

As he prepares at Camp David, President Biden, along with his deputy chief of staff Bruce Reed, carefully hones his address, which is expected to cover lowering costs, democracy, and women’s reproductive care among other topics.

Biden’s oratory may not be the most polished, but his strength lies in spontaneous and genuine interactions.

Biden dislikes Washington speak and challenges his speechwriters to communicate ideas clearly and quickly. Cluchey notes that Biden is intimately involved in the speechwriting process, emphasizing clarity and brevity.

Sometimes, when Biden deviates from the prepared text, it results in moments of authenticity that resonate well. For instance, during the previous State of the Union, his off-the-cuff response to hecklers was deemed a highlight.

Veteran speechwriters like Jeff Shesol emphasize the importance of understanding the President’s worldview, not just his speaking style. This means speechwriters spend considerable time listening to and conversing with the President to internalize his thinking.

Preparing for unscripted moments is also part of the craft. Speechwriters anticipate improvisation, especially for Presidents known for spontaneity, like Bill Clinton.

Cluchey describes the experience of watching a President go off-script as a rollercoaster of emotions, but acknowledges that these moments often reveal the President’s most sincere self.

FAQ Section

What does a presidential speechwriter do.

A presidential speechwriter is responsible for composing speeches that reflect the President’s voice and policy positions. They work closely with the President to capture their essence and deliver their message effectively to the public.

How does a President prepare for the State of the Union?

The President usually spends months preparing for the State of the Union. This involves collaboration with speechwriters, advisors, and various agencies to create a cohesive address that outlines the President’s vision and policy initiatives for the year.

Is President Biden involved in the speechwriting process?

Yes, President Biden is known to be very engaged in the speechwriting process, focusing on individual lines and words to ensure clarity and precision in his speeches.

How do speechwriters prepare for moments when a President goes off-script?

Speechwriters anticipate and prepare for improvisational moments by structuring speeches to allow the President to return to the prepared text seamlessly after an extemporaneous section. They understand that such moments can showcase the President’s authenticity and connect with the audience.

Presidential speechwriting is an intricate balance of echoing the President’s voice and packaging policy into compelling narratives. Speechwriters not only construct speeches but also serve as linguistic architects, shaping the President’s message for pivotal moments such as the State of the Union. Amidst the meticulous crafting of words and the anticipation of off-script improvisations, these writers play a crucial role in shaping political discourse. Whether in well-scripted addresses or spontaneous exchanges, the enduring power of presidential speechwriting lies in its ability to capture the authentic spirit of the nation’s leader.

Presidential Speechwriting

Five former presidential speechwriters discussed the role of presidential speechwriters throughout history and their relationships with the … read more

Five former presidential speechwriters discussed the role of presidential speechwriters throughout history and their relationships with the presidents they served. Topics included their assessments of President Obama ’s rhetoric. They also responded to questions from members of the audience.

Panel: Ted Sorensen , adviser and primary speechwriter for President Kennedy ; Chris Matthews , speechwriter for President Carter ; Landon Parvin , speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan and both Presidents Bush; Michael Waldman , speechwriter for President Clinton ; and Michael Gerson , speechwriter for President George W. Bush. The moderator was Ken Walsh .

“Presidential Speechwriters: Making History One Word at a Time” was an evening presentation of the Smithsonian Associates . close

Javascript must be enabled in order to access C-SPAN videos.

- Text type Closed Captioning Record People Graphical Timeline

- Filter by Speaker All Speakers Michael J. Gerson Chris Matthews Landon Parvin Ruth Robbins Theodore "Ted" C. Sorensen Michael Waldman Kenneth T. Walsh

- Search this text

*This text was compiled from uncorrected Closed Captioning.

People in this video

Hosting Organization

- Smithsonian Associates Smithsonian Associates

- The Presidency

- American History TV

Airing Details

- Nov 13, 2010 | 3:29pm EST | C-SPAN 3

- Nov 14, 2010 | 2:30am EST | C-SPAN 3

- Nov 14, 2010 | 8:30am EST | C-SPAN 3

- Nov 14, 2010 | 7:30pm EST | C-SPAN 3

- Nov 14, 2010 | 10:30pm EST | C-SPAN 3

- Nov 21, 2010 | 2:30am EST | C-SPAN 3

- Dec 29, 2010 | 8:00pm EST | C-SPAN 3

- Dec 30, 2010 | 12:00am EST | C-SPAN 3

- Dec 30, 2010 | 4:00am EST | C-SPAN 3

Related Video

50th Anniversary of the Kennedy-Nixon Debates

On the 50th anniversary of the first debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, a Kennedy Library Forum was held …

Obama Administration Speeches and Rhetoric

Political speechwriters and other communications professionals talked about the rhetoric used by President Obama in his …

Rhetoric and Imagery of President Kennedy

Miller Center scholars examined President Kennedy’s rhetoric, symbols, and images, as well as his collaboration with spe…

After Words with Ken Walsh

The veteran White House correspondent explores the long history of black service in the home of the president of the Uni…

User Created Clips from This Video

User Clip: Landon Parvin

User Clip: Presidential Speechwriters

User Clip: Chris Matthews Remembers Reagan's Campaign Announcement

Help inform the discussion

Mary Kate Cary

- Former speechwriter for President George H.W. Bush

- Provides political commentary for NPR, CNN, Fox News Channel, and CTV (Canada)

- Executive producer of 41ON41 , a documentary about President George H.W. Bush

- Expertise on presidential communications , speechwriting

Areas Of Expertise

- Domestic Affairs

- Media and the Press

- The Presidency

Mary Kate Cary, practitioner senior fellow, served as a White House speechwriter for President George H. W. Bush from 1989 to early 1992, authoring more than 100 of his presidential addresses. She also has ghostwritten several books related to President Bush’s life and career and served as senior writer for communications for the 1988 Bush-Quayle presidential campaign.

Currently an adjunct professor in the University of Virginia’s Department of Politics, Cary teaches classes on political speechwriting; the greatest American political speeches; and the 2020 presidential election. In her first year in the politics department, she was recognized by the UVA Student Council for excellence in teaching.

Cary currently chairs the advisory board of the George and Barbara Bush Foundation, where she has been a member since 2004. The Bush Foundation oversees the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum and the Bush School of Government & Public Service, with campuses at Texas A&M University and in Washington, D.C.. In 2014, she was the creator and executive producer of 41ON41 , a documentary about President George H. W. Bush, which premiered internationally on CNN. She is also a producer of President in Waiting, a documentary about the modern vice presidency that features interviews with all of the living vice presidents, which debuted on CNN in December 2020.

Following her tenure at the White House, Cary served as spokesman and deputy director of policy and communications for U.S. Attorney General William Barr and deputy director of communications at the Republican National Committee under Chairman Haley Barbour. She also served as a long-time columnist at US News & World Report, writing on politics and the presidency.

Cary is currently a member of the Ronald Reagan Institute's Women in Civics Advisory Council; UVA's Darden School of Business Leadership Communication Council; and the national advisory board of The Network of Enlightened Women, which supports conservative female leaders on more than 50 college campuses. She is a long-time member of the Judson Welliver Society of former presidential speechwriters.

Mary Kate Cary News Feed

How Speechwriters Delve Into a President's Mind: Lots of Listening, Studying and Becoming a Mirror

There are few times in a American presidency that the art of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union

How Speechwriters Delve Into a President's Mind: Lots of Listening, Studying and Becoming a Mirror

Patrick Semansky

FILE - President Joe Biden delivers the State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress at the U.S. Capitol, Feb. 7, 2023, in Washington. It’s an annual process that former presidential speechwriters say take months. Speechwriters have the uneviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Speechwriting, in one sense, is essentially being someone else’s mirror.

“You can try to find the right words,” said Dan Cluchey, a former speechwriter for President Joe Biden . “But ultimately, your job is to ensure that when the speech is done, that it has a reflection of the speaker.”

That concept is infinitely magnified in the role of the presidential speechwriter. Over the course of U.S. history, those aides have absorbed the personalities, the quirks, the speech cadences of the most powerful leader on the globe, capturing his thoughts for all manner of public remarks, from the mundane to the historic and most consequential.

There are few times in a presidency that the art — and the rigorous, often painful process — of speechwriting is more on display than during a State of the Union , when the vast array of a president’s policy aspirations and political messages come together in one, hour-plus carefully choreographed address at the Capitol. Biden will deliver the annual address on Thursday .

It’s a process that former White House speechwriters say take months, with untold lobbying and input from various federal agencies and others outside the president’s inner circle who are all working to ensure their favored proposals merit a mention. Speechwriters have the unenviable task of taking dozens of ideas and stitching them into a cohesive narrative of a president’s vision for the year.

It’s less elegant prose, more laundry list of policy ideas.

Photos You Should See - April 2024

Amid all those formalities and constraints of a State of the Union address, there is also how a president executes the speech.

Biden’s biggest political liability remains his age (81) and voters’ questions about whether he is still up to the job (his doctor this past week declared him fit to serve ). His every word is watched by Republican operatives eager to capture any misspeak to plant doubt about Biden’s fitness among the public.

“This year, of course, is an election year. It also comes as there’s much more chatter about his age,” said Michael Waldman, who served as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton. “People are really going to be scrutinizing him for how he delivers the speech, as much as what he says.”

Biden will remain at Camp David through Tuesday and is expected to spend much of that time preparing for the State of the Union. Bruce Reed, the White House deputy chief of staff, accompanied Biden to the presidential retreat outside Washington on Friday evening.

The White House has said lowering costs, shoring up democracy and protecting women’s reproductive care will be among the topics that Biden will address on Thursday night.

Biden likely won’t top the list of the most talented presidential orators. He has thrived the most during small chance encounters with Americans, where interactions can be more off the cuff and intimate.

The plain-spoken Biden is known to hate Washington jargon and the alphabet soup of government acronyms, and he has challenged aides, when writing his remarks, to cut through the clutter and to get to the point with speed. Cluchey, who worked for Biden from 2018 to 2022, said the president was very engaged in the speech drafting process, all the way down to individual lines and words.

Biden can also come across as stiff at times when standing and reading from a teleprompter, but immediately loosens up and appears more comfortable when he switches to a hand-held microphone mid-remark. Biden has also learned to navigate a childhood stutter that he says helped him develop empathy for others facing similar challenges.

To become engrossed in another person’s voice, past presidential speechwriters list things that are critical. One is just doing a lot of listening to the principal, to get a sense of his rhythms and how he uses language.

Lots of direct conversation with the president is key, to try and get inside the commander in chief's thinking and how that leader frames arguments and make their case.

“This is not an act of impression, where you’re simply just trying to get the accent down,” said Jeff Shesol, another former Clinton speechwriter. “What you really are learning to do and need to learn to do -– this is true of speechwriters in any role, but particularly for a president –- is to understand not just how he sounds, but how he thinks.”

Shesol added: “You’re absorbing not just the rhythms and cadences of speech, but you’re absorbing a worldview.”

Then there is always the matter of the speech-giver going rogue.

Biden is often candid, and White House aides are sometimes left to clean up and clarify what he said in unvarnished moments. But other times when he deviates from the script, it ends up being an improvement on what his aides had scripted.

Take last year’s State of the Union . Biden had launched into an attack prepared in advance against some Republicans who were insisting on requiring renewal votes on popular programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which would effectively threaten their fate every five years.

That prompted heckling from Republicans and shouts of “Liar!” from the audience.

Biden immediately pivoted, egging on the Republicans to contact his office for a copy of the proposal and joking that he was enjoying their “conversion.”

“Folks, as we all apparently agree, Social Security and Medicare is off the — off the books now, right? They’re not to be touched?” Biden continued. The crowd of lawmakers applauded. “All right. All right. We got unanimity!"

Speechwriters do try and prepare for such moments, particularly if a president is known to speak extemporaneously.

Shesol recalled that Clinton's speechwriters would draft remarks that were relatively spare, to account for him veering off on his own. The writers would write a clear structure into the speech that would allow Clinton to easily return to his prepared remarks once his riff was over.

“Clinton used to liken it to playing a jazz solo and then he’s going back to the score,” Waldman added.

Cluchey, when asked for his reaction when his former boss would go off-script, described it as a “ballet with several movements of, you know, panic, to ‘Wait a minute, this is actually very good,’ and then ‘Oh man, he really nailed it.’”

Biden is “at his best when he’s most authentically, most loosely, just speaking the plain truth,” Cluchey said. “The speechwriting process even at its best has strictures around it.”

Copyright 2024 The Associated Press . All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Join the Conversation

Tags: Associated Press , politics

America 2024

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

The FBI and NTSB Bridge Collapse Probes

Laura Mannweiler April 15, 2024

How Congress Plans to Respond to Iran

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton April 15, 2024

Trump Historic Hush Money Trial Begins

Lauren Camera April 15, 2024

War Hangs Over Economy, Markets

Tim Smart April 15, 2024

Trump Gives Johnson Vote of Confidence

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton April 12, 2024

U.S.: Threat From Iran ‘Very Credible’

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder April 12, 2024

Young Leaders Network: The Art of Presidential Speechwriting

The art of speechwriting: a conversation with presidential speechwriters .

Campaign speeches and presidential communications have distinct goals. While stump speeches are in front of a more friendly crowd, allowing the candidate to promote his or her policy goals, presidential speeches have a wider, more diverse audience that may limit what goals the president can promote. Former presidential speechwriters on how they tackled this issue and what strategies they used to write memorable and historic speeches for former Presidents.

The John Brademas Center at New York University, as part of the 2018 Young Leaders Network series, hosted a dialogue with John P. McConnell , former speechwriter to President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney, and June Shih , former speechwriter to President Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham Clinton. The pair discussed their own experiences of writing historic presidential and campaign speeches. The event was moderated by Vaughn Hillyard , Political Reporter at NBC News.

This free event was open to all Congressional interns and members of the public.

Event Photos

John P. McConnell

Vaughn Hillyard

John P. McConnell served more than ten years on the White House staff, in two administrations. As a senior speechwriter for President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney, he was part of the three-person team responsible for all of the 43 rd President’s major addresses.

In the Bush-Cheney White House, John held the unique position of both Deputy Assistant to the President and Assistant to the Vice President. In his career he has also worked as a principal speechwriter for Vice President Dan Quayle, 1996 presidential nominee Bob Dole, and 2012 vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan.

John is a former resident fellow at Harvard University’s Institute of Politics, in the John F. Kennedy School of Government. He is a trustee of Wayland Academy and serves as chairman of the selection committee for the annual Gerald R. Ford Journalism Prize for Distinguished Reporting on the Presidency.

A lifelong political enthusiast, John was a page in the United States Senate under the sponsorship of Senator William Proxmire. He grew up in Bayfield, Wisconsin and is a graduate of Wayland Academy, Carleton College, and Yale Law School.

June Shih is a writer and lawyer with nearly 25 years’ experience in speechwriting, communication and public policy. She began her career as a cops and courts reporter for a Florida newspaper, but left to assist then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton with her syndicated newspaper column and speeches. In 1997, she became a Special Assistant to the President and Presidential Speechwriter, writing speeches for President Bill Clinton on a range of issues from civil rights and race relations to education and health care policy. After serving as chief speechwriter for Mrs. Clinton’s first U.S. Senate campaign in 2000, June attended law school and then practiced law in Silicon Valley and Washington, D.C. From 2011-2014, she served in the Obama Administration as a Senior Advisor in the U.S. State Department’s Office of Global Women’s Issues, helping to shape initiatives on global women’s leadership and girls’ education. She also served as an expert on East Asian affairs and managed bilateral dialogues with Chinese, Korean, and Japanese counterparts. June is fluent in Mandarin Chinese and holds a B.A., magna cum laude, from Harvard University, and a J.D. from Stanford Law School.

This August, June will join the leadership team of NYU-Shanghai as Director of University Communications.

Vaughn Hillyard is an award winning journalist and Political Reporter for NBC News, notably covering the special election Senate race in Alabama between Roy Moore and Doug Jones and the entirety of the 2016 presidential campaign as an embedded reporter, from the Iowa coffee shop stops to election night at Trump HQ in New York. Vaughn first started at NBC News in July 2013 as a Tim Russert fellow.

Vaughn began his journalism career in Arizona at AZ Fact Check, Arizona Republic, Channel 12 News and AZCentral.

Vaughn attended Arizona State University, where he received a Bachelor’s and master’s degree in journalism.

Our Last Great Adventure

My husband, Richard Goodwin, drafted landmark speeches for JFK and LBJ. Late in life, we dived into his archives, searching for vivid traces of our hopeful youth.

O ne summer morning, seven months after he had turned 80, my husband, Dick Goodwin, came down the stairs, clumps of shaving cream on his earlobes, singing, “The corn is as high as an elephant’s eye,” from the musical Oklahoma!

“Why so chipper?” I asked.

“I had a flash,” he said, looking over the headlines of the three newspapers I had laid out for him on the breakfast table in our home in Concord, Massachusetts. Putting them aside, he started writing down numbers. “Three times eight is 24. Three times 80 is 240.”

“Is that your revelation?” I asked.

Explore the May 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

“Look, my 80-year life span occupies more than a third of our republic’s history. That means that our democracy is merely three ‘Goodwins’ long.”

I tried to suppress a smile.

“Doris, one Goodwin ago, when I was born, we were in the midst of the Great Depression. Pearl Harbor happened on December 7, 1941, my 10th birthday. It ruined my whole party! If we go back two Goodwins, we find our Concord Village roiled in furor over the Fugitive Slave Act. A third Goodwin will bring us back to the point that, if we went out our front door, took a left, and walked down the road, we might just see those embattled farmers and witness the commencement of the Revolutionary War.”

He glanced at the newspapers and went to his study, on the far side of the house. An hour later, he was back to read aloud a paragraph he had just written:

Three spans of one long life traverse the whole of our short national history. One certain thing that a look backward at the vicissitudes of our country’s story suggests is that massive and sweeping change will come. And it can come swiftly. Whether or not it is healing and inclusive change depends on us. As ever, such change will generally percolate from the ground up, as in the days of the American Revolution, the anti-slavery movement, the progressive movement, the civil-rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay-rights movement, the environmental movement. From the long view of my life, I see how history turns and veers. The end of our country has loomed many times before. America is not as fragile as it seems.

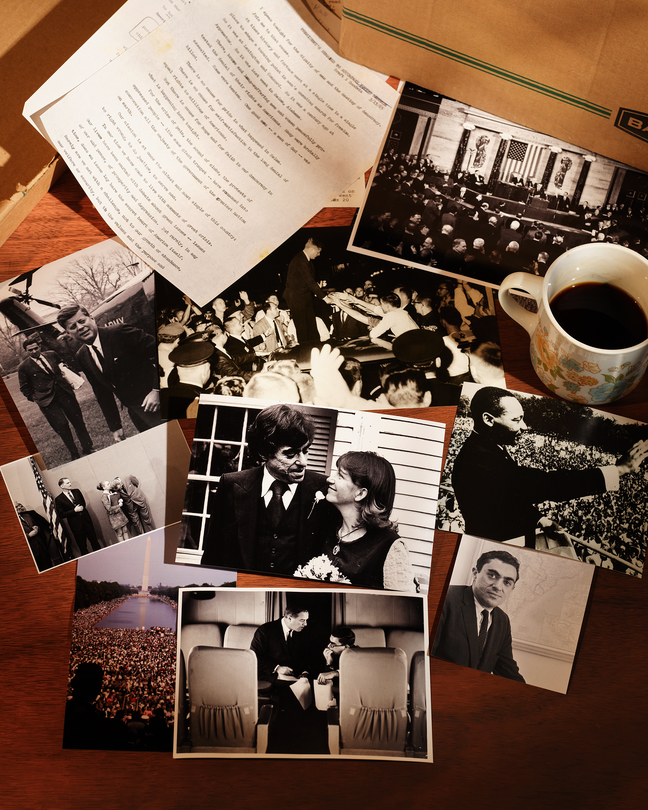

“It’s now or never,” he said, announcing that the time had finally come to unpack and examine the 300 boxes of material he had dragged along with us during 40 years of marriage. Dick had saved everything relating to his time in public service in the 1960s as a speechwriter for and adviser to John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy, and Eugene McCarthy: reams of White House memos, diaries, initial drafts of speeches annotated by presidents and presidential hopefuls, newspaper clippings, scrapbooks, photographs, menus—a mass that would prove to contain a unique and comprehensive archive of a pivotal era. Dick had been involved in a remarkable number of defining moments .

He was the junior speechwriter, working under Ted Sorensen, during JFK’s 1960 presidential campaign. He was in the room to help the candidate prepare for his first televised debate with Richard Nixon. In the box labeled DEBATE were pages torn from a yellow pad upon which Kennedy had scrawled requests for information or clarification. Dick was in the White House when the president’s coffin returned from Dallas, and he was responsible for making arrangements to install an eternal flame at the grave site. He was at LBJ’s side during the summit of his historic achievements in civil rights and the Great Society. He was in New Hampshire during McCarthy’s crusade against the Vietnam War, and in the hospital room when Robert Kennedy died in Los Angeles. He was a central figure in the debate over the peace plank during the mayhem of the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

For years, however, Dick had resisted opening these boxes. They were from a time he recalled with both elation and a crushing sense of loss. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy; the war in Vietnam; the riots in the cities; the violence on college campuses—all the turmoil had drawn a dark curtain on the entire decade. He had wanted only to look ahead.

Doris Kearns Goodwin: The divided legacy of Lyndon B. Johnson

Now he had resolved to go back in time. “I’m an old guy,” he said. “If I have any wisdom to dispense, I’d better start dispensing.” A friend, Deb Colby, became his research assistant, and together they began the slow process of arranging the boxes in chronological order. Once that preliminary task had been completed, Dick was hopeful that there might be something of a book in the material he had uncovered. He wanted me to go back with him to the very first box and work our way through all of them. I was not only his wife but a historian.

“I need your help,” he said. “Jog my memory, ask me questions, see what we can learn.” I joined him in his study, and we started on the first group of boxes. We made a deal to try to spend time on this project every weekend to see what might come of it.

Our last great adventure together was about to begin.

Some 30 boxes contained materials relating to JFK’s 1960 presidential campaign. From September 4 to November 8, 1960, Dick was a member of the small entourage that flew across the country with Kennedy for more than two months of nonstop campaigning. The first-ever private plane used by a presidential candidate during a campaign, the Caroline (named for Kennedy’s daughter) had been modified into a luxurious executive office. It had plush couches and four chairs that could be converted into small beds—two of them for Dick and Ted Sorensen. Kennedy had his own suite of bedrooms farther aft.

“You were all so young,” I marveled to Dick after looking up the ages of the team. The candidate was 43; Bobby Kennedy, 34; Ted Sorensen, 32. “And you—”

“Twenty-eight,” he interrupted, adding, “Youngest of the lot.”

After midnight on October 14, 1960, the Caroline landed at Willow Run Airport, near Ypsilanti, Michigan. Three weeks remained until Election Day. Everyone was bone-tired as the caravan set out for Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan.

As they approached the Michigan campus, there was little to suggest that one of the most enduring moments of the campaign was about to occur. It was nearly 2 a.m. by the time the caravan reached the Michigan Union, where Kennedy was scheduled to catch a few hours of sleep before starting on a whistle-stop tour of the state. No one in the campaign had expected to find as many as 10,000 students waiting in the streets to greet the candidate. Neither Ted nor Dick had prepared remarks for the occasion.

As Kennedy ascended the steps of the union, the crowd chanted his name. He turned around, smiled, and introduced himself as “a graduate of the Michigan of the East—Harvard University.” He then began speaking extemporaneously, falling back on his familiar argument that the 1960 campaign presaged the outcome of the race between communism and the free world. But suddenly, he caught a second wind and swerved from his stock stump speech. He asked the crowd of young people what they might be willing to contribute for the sake of the country.

How many of you who are going to be doctors are willing to spend your days in Ghana? Technicians or engineers, how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world? On your willingness to do that, not merely to serve one year or two in the service, but on your willingness to contribute part of your life to this country, I think will depend the answer whether a free society can compete.

What stirred Kennedy to these spontaneous questions is not clear. Weariness, intuition, or—most likely, I suspect—because they had lingered in his mind after the third debate with Nixon, which had taken place only hours before and had been focused on whether America’s prestige in the world was rising or falling relative to that of Communist nations. The concept of students volunteering for public service in Africa and Asia might well bolster goodwill for America in countries wavering (as Kennedy had put it) “on the razor edge of decision” between the free world and the Communist system.

Drawing his impromptu speech to a close, Kennedy confessed that he had come to the union on this cold and early morning simply to go to bed. The words elicited raucous laughter and applause that continued to mount when he threw down a final challenge: “May I just say in conclusion that this university is not maintained by its alumni, by the state, merely to help its graduates have an economic advantage in the life struggle. There is certainly a greater purpose, and I’m sure you recognize it.”

Kennedy’s remarks lasted only three minutes—“the longest short speech,” he called it. Yet something extraordinary transpired: The students took up the challenge he posed. Led by two graduate students, Alan and Judith Guskin, they organized, they held meetings , they sent letters and telegrams to the campaign asking Kennedy to develop plans for a corps of American volunteers overseas. Within a week, 1,000 students had signed petitions pledging to give two years of their lives to help people in developing countries.

When Dick and Ted learned of the student petitions, they redrafted an upcoming Kennedy speech on foreign policy to be delivered at the Cow Palace, in San Francisco, working in a formal proposal for “a peace corps of talented young men and women.” We pulled the speech from one of the boxes. Dick’s hand can be readily detected in the closing lines, which used a favorite quote of his from the Greek philosopher Archimedes. “Give me a fulcrum,” Archimedes said, “and I will move the world.” Dick would later invoke the same line in a historic speech by Robert Kennedy in South Africa.

Two days after JFK’s speech at the Cow Palace, the candidate was flying to Toledo, Ohio . He sent word to the Guskins that he would like to meet them and see their petitions, crammed with names. A photo captures the moment when an eager Judy Guskin clutches the petitions before she presents them to the weary-eyed Kennedy, who is reaching out in anticipation.

Later, Dick and Ted had coffee with Judy and Alan. They talked of the Peace Corps and the election, by then only five days away. Nixon had immediately denounced the idea of a Peace Corps—“ a Kiddie Corps ,” he and others called it—warning that it would become a haven for draft dodgers. But for Judy and Alan, as for nearly a quarter of a million others, the Peace Corps would prove a transformative experience. The Guskins were in the first group to travel to Thailand, where Judy taught English and organized a teacher-training program. Alan set up a program at the same school in psychology and educational research. Returning home, they served as founders of the VISTA program, LBJ’s domestic version of the Peace Corps.

For Dick, the Peace Corps, more than any other venture of the Kennedy years, represented the essence of the administration’s New Frontier vision. After JFK’s inauguration, as a member of the White House staff, Dick joined the task force that formally launched the Peace Corps. He was barely older than the typical volunteer.

SUMMER 1963

Dick and I often talked, half-jokingly, half-seriously, about the various occasions when we were in the same place at the same time before we finally met—in the summer of 1972, when he arrived at the Harvard building where I had my office as an assistant professor. I knew who he was. I had heard that he was brilliant, brash, mercurial, arrogant, a fascinating figure. He was more than a decade older than me. His appearance was intriguing: curly, disheveled black hair; thick, unruly eyebrows; a pockmarked face; and several large cigars in the pocket of his casual shirt. We began a conversation that day about LBJ, literature, philosophy, astronomy, sex, gossip, and the Red Sox that would continue for 46 years.

The first occasion when we could have crossed paths but didn’t was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, on August 28, 1963. It was not surprising that we didn’t meet, given that some 250,000 people had gathered for the event.

I was spending the summer before my senior year at Colby College as an intern at the State Department. All government employees had been given the day off and been cautioned to stay home, warned that it wasn’t safe. I was 20 years old—I had no intention of staying home. But I still remember the nervous excitement I felt that morning as I walked with a group of friends toward the Washington Monument. We had been planning to attend the march for weeks.

A state of emergency had been declared as people descended on the capital from all over the country. Marchers arriving by bus and train on Wednesday morning were encouraged to depart the city proper by that night. Hospitals canceled elective surgery to make space in the event of mass casualties. The Washington Senators baseball game was postponed . Liquor stores and bars were closed. We learned that thousands of National Guardsmen had been mobilized to bolster the D.C. police force. Thousands of additional soldiers stood ready across the Potomac, in Virginia.

I asked Dick if these precautions had seemed a bit much. He explained that Kennedy was worried that if things got out of hand, the civil-rights bill he had introduced in June could unravel, and “take his administration with it.” Though government workers were discouraged from attending the march, Dick grabbed Bill Moyers, the deputy Peace Corps director, and headed toward the National Mall.

So there Dick and I were, unknown to each other, both moving along with what seemed to be all of humanity toward the Reflecting Pool and the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, where the march would culminate. I carried a poster stapled to a stick: Catholics, Protestants and Jews Unite in the Struggle for Civil Rights . A sense that I was connected to something larger than myself took hold.

It’s easy to cast a cynical eye upon this youthful exultation, to view it in retrospect as sentimental idealism, but the feelings were genuine, and they were profound. At the start of the march, I had wondered what proportion of the vast throng was white (it was later estimated at 25 percent). By the time I returned to my rooming house in Foggy Bottom, I had forgotten all about calculations and proportions. I had set out that morning apprehensive, yet had been lifted up by the most joyful day of public unity and community I had ever experienced.

Facing the Lincoln Memorial, with Martin Luther King’s soaring “I Have a Dream” speech still ahead, we all held hands, our voices rising as we sang “We Shall Overcome”—the hymn that had long instilled purpose and courage in the foot soldiers of the civil-rights movement. That moment made as deep an impression on Dick as it did on me.

SPRING 1964

During our years of archival sifting, Dick and I, like two nosy neighbors on a party line, tracked down transcripts of conversations recorded by Lyndon Johnson’s secret taping system.

“How splendid to be flies on the wall, to eavesdrop across the decades!” That was Dick’s gleeful response after I read him a transcript of a telephone call between the president and Bill Moyers—by then a special assistant to Johnson—on the evening of March 9, 1964. Here Dick and I were, he in his 80s and I in my 70s, finally privy to the very conversation that, previously unbeknownst to Dick, had led him from the nucleus of the Kennedy camp, through a period of confusion and drift in the aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination, to the highest circles of the Johnson administration.

The phone call began with Johnson grousing about the dreary language in the poverty message that he soon planned to deliver to Congress. Passionately invested in the poverty program, he was dissatisfied with the drafts he had seen and was now pressing Moyers to find “whoever’s the best explainer of this that you can get.”

Johnson: Since [Ted] Sorensen left, we’ve got no one that can be phonetic, and get rhythm … Moyers: The only person I know who can—and I’m reluctant to ask him to get involved in this, because right now it’s in our little circle—is Goodwin. Johnson: Why not just ask him if he can’t put some sex in it? I’d ask him if he couldn’t put some rhyme in it and some beautiful Churchillian phrases and take it and turn it out for us tomorrow … If he will, then we’ll use it. But ask him if he can do it in confidence. Call him tonight and say, “I want to bring it to you now. I’ve got it ready to go, but he wants you to work on it if you can do it without getting it into a column.” Moyers: All right, I’ll call him right now. Johnson: Tell him that I’m pretty impressed with him. He’s working on Latin America already; see how he’s getting along. But can he put the music to it?

As we reached the end of the conversation, Dick swore that he could hear Johnson’s voice clearly in his mind’s ear. “Lyndon’s a kind of poet,” Dick said. “What a unique recipe for high oratory: rhyme, sex, music, phonetics, and beautiful Churchillian phrases.”

We both knew him so well: Dick because he worked with him intimately in the White House and on the 1964 campaign, and I because, after a time as a White House fellow, I’d joined a small team in Texas to help him go through his papers, conduct research, and draft his memoir. From the time Dick and I met, we often referred to the president simply as “Lyndon” when speaking with each other. There are a lot of Johnsons, but there was only one Lyndon .

SPRING 1965

A year and a half after the March on Washington, the memory of its transcendent finale returned to become the heart of the most important speech Dick ever drafted. We pulled a copy of the draft, some notes, the final speech, and newspaper clippings from one of the Johnson boxes.

The moment Dick stepped into the West Wing on the morning of March 15, 1965, he sensed an unusual hubbub and tension. Pacing back and forth in a dither outside Dick’s second-floor office was the White House special assistant Jack Valenti. Normally full of glossy good cheer, Valenti pounced on Dick before he could even open his office door.

The night before, Johnson had decided to give a televised address to a joint session of Congress calling for a voting-rights bill. He believed that the conscience of America had been fired by the events at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, a week earlier, when peaceful marchers had been attacked by Alabama state troopers wielding clubs, nightsticks, and whips.

“He needs the speech from you right away,” Valenti said.

“From me! Why didn’t you tell me yesterday? I’ve lost the entire night,” Dick responded.

“It was a mistake, my mistake,” Valenti acknowledged. He explained that the first words out of the president’s mouth that morning had been “How is Goodwin doing on the speech?” and Valenti had told him he’d assigned it to another aide, Horace Busby. Johnson had erupted, “The hell you did! Get Dick to do it, and now !”

The speech had to be finished before 6 p.m., Valenti told Dick, in order to be loaded onto the teleprompter. Dick looked at his watch. Nine hours away. Valenti asked Dick if there was anything—anything at all—he could get for him.

“Serenity,” Dick replied, “a globe of serenity. I can’t be disturbed. If you want to know how it’s coming, ask my secretary.”

“I didn’t want to think about time passing,” Dick recalled to me. “I lit a cigar, looked at my watch, took the watch off my wrist, and put it on the desk beside my typewriter. Another puff of my cigar, and I took the watch and put it away in my desk drawer.”

“The pressure would have short-circuited me,” I said. “I never had the makings of a good speechwriter or journalist. History is more patient.”

“Well,” Dick said, laughing, “miss the speech deadline and those pages are only scraps of paper.”

Dick examined the folder of notes Valenti had given him. Johnson wanted no uncertainty about where he stood. To deny fellow Americans the right to vote was simply and unequivocally wrong. He wanted the speech to be affirmative and hopeful. He would be sending a bill to Congress to protect the right to vote for all Americans, and he wanted this speech to speed public sentiment along.

In the year since Dick had started working at the White House, he had listened to Johnson talk for hundreds of hours—on planes and in cars, during meals in the mansion and at his ranch, in the swimming pool and over late-night drinks. He understood Johnson’s deeply held convictions about civil rights, and he had the cadences of his speech in his ear. The speechwriter’s job, Dick knew, was to clarify, heighten, and polish a speaker’s convictions in the speaker’s own language and natural rhythms. Without that authenticity, the emotional current of the speech would never hit home.

I knew that Dick often searched for a short, arresting sentence to begin every speech or article he wrote. On this day, he surely found it:

I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy … At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.

No sooner would Dick pull a page out of his typewriter and give it to his secretary than Valenti would somehow materialize, a nerve-worn courier, eager to express pages from Dick’s secretary into the president’s anxious hands. Johnson’s edits and penciled notations were incorporated into the text while he awaited the next installment, lashing out at everyone within range—everyone except Dick.

The speech was no lawyer’s brief debating the merits of the bill to be sent to Congress. It was a credo, a declaration of what we are as a nation and who we are as a people—a redefining moment in our history brought forth by the civil-rights movement.

The real hero of this struggle is the American Negro. His actions and protests, his courage to risk safety and even to risk his life, have awakened the conscience of this nation … He has called upon us to make good the promise of America. And who among us can say that we would have made the same progress were it not for his persistent bravery, and his faith in American democracy?

As the light shifted across his office, Dick became aware that the day suddenly seemed to be rushing by. He opened the desk drawer, peered at the face of his watch, took a deep breath, and slammed the drawer shut. He walked outside to get air and refresh his mind.

In the distance, Dick heard demonstrators demanding that Johnson send federal troops to Selma. Dick hurried back to his office. Something seemed forlorn about the receding voices—such a great contrast to the spirited resolve of the March on Washington. Loud and clear, the words We shall overcome sounded in his head.

It was after the 6-o’clock deadline when the phone in Dick’s office rang for the first time that day. The voice at the other end was so relaxed and soothing that Dick hardly recognized it as the president’s.

“Far and away,” Dick told me, “the gentlest tones I ever heard from Lyndon.”

“You remember, Dick,” Johnson said, “that one of my first jobs after college was teaching young Mexican Americans in Cotulla. I told you about that down at the ranch. I thought you might want to put in a reference to that.” Then he ended the call: “Well, I won’t keep you, Dick. It’s getting late.”

“When I finished the draft,” Dick recalled, “I felt perfectly blank. It was done. It was beyond revision. It was dark outside, and I checked my wrist to see what time it was, remembered I had hidden my watch away from my sight, retrieved it from the drawer, and put it back on.”

There was nothing left to do but shave, grab a sandwich, and stroll over to the mansion. There, greeted by an exorbitantly grateful Valenti, Dick hardly had the energy to talk. Before he knew it, he was sitting with the president in his limousine on the way to the Capitol.

A hush filled the chamber as the president began to speak. Watching from the well of the House, an exhausted Dick marveled at Johnson’s emotional gravity. The president’s somber, urgent, relentlessly driving delivery demonstrated a conviction and exposed a vulnerability that surpassed anything Dick had seen in him before.

There is no constitutional issue here. The command of the Constitution is plain. There is no moral issue. It is wrong—deadly wrong—to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. There is no issue of states’ rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights … This time, on this issue, there must be no delay, or no hesitation or no compromise with our purpose … But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches in every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And — we — shall — overcome.

The words came staccato, each hammered and sharply distinct from the others. In Selma, Alabama, Martin Luther King had gathered with friends and colleagues to watch the president’s speech. At this climactic moment when Johnson took up the banner of the civil-rights movement, John Lewis witnessed tears rolling down King’s cheeks.

The time had come for the president to draw on his own experience, to tell the formative story he had mentioned to Dick on the phone.

My first job after college was as a teacher in Cotulla, Texas, in a small Mexican American school. Few of them could speak English, and I couldn’t speak much Spanish. My students were poor, and they often came to class without breakfast, hungry. And they knew, even in their youth, the pain of prejudice. They never seemed to know why people disliked them. But they knew it was so, because I saw it in their eyes. I often walked home late in the afternoon, after the classes were finished, wishing there was more that I could do … Somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child. I never thought then, in 1928, that I would be standing here in 1965. It never even occurred to me in my fondest dreams that I might have the chance to help the sons and daughters of those students and to help people like them all over this country. But now I do have that chance—and I’ll let you in on a secret: I mean to use it.

The audience stood to deliver perhaps the largest ovation of the night.

I told Dick that I had read an account that when Johnson was later asked who had written the speech, he pulled out a photo of his 20-year-old self surrounded by a cluster of kids, his former students in Cotulla. “ They did,” he said, indicating the whole lot of them.

“You know,” Dick said with a smile, “in the deepest sense, that might just be the truth.”

“God, how I loved Lyndon Johnson that night,” Dick remembered. He long treasured a pen that Johnson gave him after signing the Voting Rights Act. “How unimaginable it would have been to think that in two years time I would, like many others who listened that night, go into the streets against him.”

Nor could I have imagined, as I talked excitedly with my graduate-school friends at Harvard after listening to the speech—certain that a new tide was rising in our country—that only a few years later I would work directly for the president who delivered it. Or that 10 years later, I would marry the man who drafted it.

SPRING 2015

One morning, two years into our project, I found Dick mumbling and grumbling as he worked his way along the two-tiered row of archival containers. “Look how many boxes we have left!” he exclaimed. “See Jackie and Bobby here, more Lyndon, riots and protests, McCarthy, anti-war marches, assassinations. Look at them!”

“I guess we better pick up our pace,” I offered.

“You’re a lot younger than me. Shovel more coal into our old train and let’s go.”

This determination to steam ahead had only increased as Dick approached his mid-80s. A pacemaker regulated his heart, he needed a hearing aid, his balance was compromised. One afternoon, he tripped on the way to feeding the fish in our backyard. He sat down on a bench, a pensive expression on his face. I asked if he was okay.

“I heard time’s winged chariot hurrying near,” he said, quoting Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” but then added, “Maybe it was only the hiss of my hearing aid.”

From the June 1971 issue: Richard Goodwin on the social theory of Herbert Marcuse

“Who would you bet on?” he asked me one night at bedtime. “Who will be finished first—me or the boxes?”

Our work on the boxes kept him anchored with a purpose even after he was diagnosed with the cancer that took his life in 2018.

I realize now that we were both in the grip of an enchanted thought—that so long as we had more boxes to unpack, more work to do, his life, my life, our life together would not be finished. So long as we were learning, laughing, discussing the boxes, we were alive. If a talisman is an object thought to have magical powers and to bring luck, the boxes and the future book they held had become ours.

*Lead image sources (left to right from top) : Richard N. Goodwin Papers / Courtesy of Briscoe Center for American History; Cecil Stoughton / Courtesy of LBJ Library; Gibson Moss / Alamy; Associated Press; Yoichi Okamoto / Courtesy of LBJ Library; Marc Peloquin / Courtesy of Doris Kearns Goodwin; Heritage Images / Getty; Bob Parent / Getty; Paul Conklin / Getty; Bettmann / Getty

This essay has been adapted from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s . It appears in the May 2024 print edition with the headline “The Speechwriter.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Achsah Nesmith, who wrote speeches for President Jimmy Carter, has died at age 84

This April 2016 photo provided by Terry Adamson shows Achsah Nesmith, second from left, and her husband, Jeff Nesmith, right, posing for a photo with former President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn Carter, in Plains, Ga. Achsah Nesmith, a speechwriter for Carter during his presidency, died March 5, 2025, in Alexandria, Va. (Terry Adamson via AP)

This photo taken March 14, 2024, in Alexadria, Va., shows a 1978 newspaper on which then-President Jimmy Carter wrote a personal note to one of his speechwriters, Achsah Nesmith. One of the first women to write speeches for an American president, Nesmith worked at the Carter White House for all four years of his presidency. She died March 5, 2024, in Alexandria, Va., at age 84. (AP/Susannah Nesmith)

- Copy Link copied

When Achsah Nesmith got the phone call offering her a job writing presidential speeches for Jimmy Carter, she turned it down. As the mother of two young children, she explained to Carter’s chief of staff, she just didn’t have time.

Nesmith quickly changed her mind, however, and called back to accept with encouragement from her husband, a fellow journalist who told her: “I can raise two babies.” She arrived at the White House right after Carter’s 1977 inauguration, becoming one of the first women to work as a speechwriter for an American president.

“She was not one to tout her own accomplishments,” Susannah Nesmith said of her mother. “She was always careful to point out that Betty Ford had a speechwriter who wrote for President Ford. And John Adams’ wife wrote some, if not all, of his speeches.”

Nesmith, who lived in Alexandria, Virginia, died March 5 following a brief illness at age 84. She prided herself on crafting speeches that enabled Carter to sound like himself, free of political double-speak and cliches, her daughter said.

“She was one of his favorite speechwriters by far. She just had his voice,” said Terry Adamson, who worked with Nesmith in the newsroom of The Atlanta Constitution before serving in the Justice Department during the Carter administration and later as Carter’s personal attorney.

Carter, 99, entered hospice care a year ago at his home in Plains, Georgia, and is the longest-living U.S. president.

When he met Nesmith, Carter was a little-known peanut farmer running his first campaign for Georgia governor in 1966. She was a reporter for The Atlanta Constitution covering the race, which Carter lost.

“She was sometimes the only reporter on those campaign stops, because he traveled all over the state,” Susannah Nesmith said in a phone interview. “So she got to know him very well. They had similar ideas, I think, about justice and about a new South that could shed its racist legacy.”

Nesmith started as an intern at the Atlanta newspaper, her daughter said, and was hired full-time after she kept coming to work after her internship had officially ended. She was assigned to cover Atlanta’s federal courts as they ruled on important civil rights cases. And she wrote stories about some of the civil rights movement’s key figures, including Martin Luther King Jr.

On April 5, 1968, the day after King was assassinated in Tennessee, the front page of The Atlanta Constitution included the obituary Nesmith wrote, memorializing King as the grandson of a slave whose nonviolent activism made him “one of the best known men in the world.”

“She told me she wrote that while crying,” Nesmith’s daughter said.

Nesmith’s rapport with Carter paid off soon after he won the presidency in 1976 and his chief of staff, Jody Powell, hired her as a speechwriter. It took some adjustment by Carter, who was used to preparing his own public remarks as Georgia governor and even wrote his own inaugural address.

Nesmith would later say their shared Georgia roots gave her an edge in writing for Carter, noting that she was the only fellow Southerner on his speechwriting staff.