Reflections on the digital age: 7 improvements that brought about a decade of positive change

The new digital age enabled billions of people to collaborate and mobilize to fight climate change. Image: Photo by kazuend on Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Don Tapscott C.M.

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved .chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, davos agenda.

Listen to the article

September 2030 . The early 2020s were full of dramatic turning points in global history.

Powerful new technologies like artificial intelligence, blockchain, the internet of things and the metaverse upended traditional systems, institutions and ways of life. Meanwhile, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-22 accelerated these trends as people everywhere moved much of their lives online. The pandemic also exposed deep problems in our governments and systems for everything from supply chains to public health data.

Moreover, the early 2020s were jolted by political upheaval. Notably, in January 2021, the American election was challenged, exacerbating deep fissures in the United States and emboldening populists and extremists around the world. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, global sanctions and significant disruptions to food supplies further convulsed the global economy and exacerbated tensions. These challenges, among others, created a perfect storm and resulted in extraordinary social anxiety and unrest.

Fortunately, a miracle of sorts occurred. Driven by a deep hope for a brighter future, people everywhere began to reimagine the relationship between government and civil society, ushering in a new societal framework for the digital age. This was not some kind of academic process but rather the result of mass mobilizations around broad change.

Reflecting on the digital age

Today, looking back a decade, let’s examine seven key improvements that stemmed from this period of positive change:

1. New models of prosperity and work

Given the bifurcation of wealth and structural unemployment in many economies engendered by the new digital age, expectations of employment shifted, with people understanding that the private sector cannot provide jobs and prosperous life for all. New rules and regulations were instituted that created a strong social safety net for workers. These reforms helped mitigate the gross inequality that plagued the early years of the 21 st century. New technologies also brought more underserved people into the global economy and readied workers for lifelong learning.

2. New models of digital identity

New regulations allowed individuals to own and benefit from the digital data they create. This ended the era of “digital feudalism,” which was characterised by a centralized group of “digital landlords” who collected, aggregated and profited from the data that collectively constituted our digital identities. Furthermore, Web3 gave people the ability to harvest their data trail and use it to plan their lives, enhancing their prosperity and protecting their privacy.

3. More informed digital age society

Through public and private partnerships, media systems were rebuilt in ways that safeguarded independence and free speech. New tools were implemented that enabled citizens to track the veracity and provenance of information. This helped reduce the ability of bad-faith actors to spread false information about everything from climate change to public health. Clear rules were also set that ensured large media companies were prohibited from supporting hate on their platforms in the digital age. These reforms helped us rebuild public education systems to ensure that every young person can function fully, not just as a worker or entrepreneur, but as a citizen. Media literacy programs were also introduced into schools to help young people develop their capabilities to handle the onslaught of information and discern the truth.

4. Renewed trust in government and democracy

Innovative technologies and other modern reforms enabled us to create a new era of democracy based on public deliberation, transparency, active citizenship and accountability. Technology also helped to embed electoral promises into smart contracts that allowed citizens to track and engage in their democracies through the mobile platforms they use every day. These reforms helped boost trust in politicians and the legitimacy of our governments as leaders are now more beholden to the people and not the powerful interests that funded their campaigns in the years prior. Moreover, these improvements helped stifle radical populists and extreme politicians on both the right and left.

5. A new commitment to justice

It was clear that new technologies exacerbated racial divides, so governments and organisations throughout civil society committed to ending racial inequities. In the United States, action was taken to end the era of mass incarceration and the financial hamstringing of minority groups. The criminal subjection of indigenous peoples as evidenced by Canada’s “Residential School System” was also readdressed. These steps helped move racism, class oppression and subjugation of all peoples into the dustbin of history, along with those who perpetrate these vile relics of the past. The reforms also went past the tropes about bad apples and forgiveness. They recognized that racism and oppression are systemic and must be addressed society-wide.

6. A deep commitment to sustainability

Through major reforms, the world is now on track to reduce carbon emissions by 90% by the year 2050. The new digital age enabled billions of people to collaborate and mobilize to fight climate change. This included not just governments but businesses large and small, commuters, vacationers, employees, students, consumers – everyone – from every walk of life. Public pressure and new regulations have also forced business executives to participate responsibly in the reindustrialization of our planet and embrace carbon pricing.

7. Global interdependence

The crises of the past decade—the COVID-19 pandemic, the political legitimacy crisis, the war in Ukraine and the climate catastrophes—demonstrated that no country could succeed fully in a world that is in trouble. And while significant national differences remain, countries have embraced common interests and an understanding of a common fate. The new way of thinking also allowed governments, companies and NGOs to better organise around solving major problems like public health, education, social justice, environmental stability and peace.

These positive changes did not bring about a utopia. But they were improvements—and ones that were achieved through bottom-up struggle.

Victor Hugo said there is nothing so powerful as an idea whose time has come. In our case, there was nothing so powerful as ideas that had become necessities.

The World Economic Forum’s Platform for Shaping the Future of Digital Economy and New Value Creation helps companies and governments leverage technology to develop digitally-driven business models that ensure growth and equity for an inclusive and sustainable economy.

- The Digital Transformation for Long-Term Growth programme is bringing together industry leaders, innovators, experts and policymakers to accelerate new digital business models that create the sustainable and resilient industries of tomorrow.

- The Forum’s EDISON Alliance is mobilizing leaders from across sectors to accelerate digital inclusion . Its 1 Billion Lives Challenge harnesses cross-sector commitments and action to improve people’s lives through affordable access to digital solutions in education, healthcare, and financial services by 2025.

Contact us for more information on how to get involved.

This article is abridged from an major essay written by Don Tapscott called “A Declaration of Interdependence: Towards a New Social Contract for the Digital Age” and a recent short essay entitled “ Why We Built a Social Contract for the New Digital Age.”

Don Tapscott is author of 16 widely read books about technology in business and society, including the best-seller Blockchain Revolution , which he co-authored with his son Alex. His most recent book is Platform Revolution: Blockchain Technology as the Operating System of the Digital Age. He is Co-Founder of the Blockchain Research Institute , an Adjunct Professor at INSEAD, and Chancellor Emeritus of Trent University in Canada. He is a Member of the Order of Canada and drafted a framework for “ A New Social Contract for the Digital Economy.”

Have you read?

Why businesses must embrace change in the digital age, companies' esg strategies must stand up to scrutiny in the digital age, what is the role of government in the digital age, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Davos Agenda .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Building trust amid uncertainty – 3 risk experts on the state of the world in 2024

Andrea Willige

March 27, 2024

Why obesity is rising and how we can live healthy lives

Shyam Bishen

March 20, 2024

Global cooperation is stalling – but new trade pacts show collaboration is still possible. Here are 6 to know about

Simon Torkington

March 15, 2024

How messages of hope, diversity and representation are being used to inspire changemakers to act

Miranda Barker

March 7, 2024

AI, leadership, and the art of persuasion – Forum podcasts you should hear this month

Robin Pomeroy

March 1, 2024

This is how AI is impacting – and shaping – the creative industries, according to experts at Davos

Kate Whiting

February 28, 2024

Home — Essay Samples — Information Science and Technology — Digital Era — The Digital Information Age

The Digital Information Age

- Categories: Digital Era Information Age Internet

About this sample

Words: 1090 |

Published: Jun 5, 2019

Words: 1090 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Information Science and Technology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 972 words

2 pages / 683 words

1 pages / 653 words

2 pages / 985 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Digital Era

The question of whether students should have limited access to the internet is a complex and timely one, given the pervasive role of technology in education. While the internet offers a wealth of information and resources, [...]

Clarke, Roger. 'Dataveillance by Governments: The Technique of Computer Matching.' In Information Systems and Dataveillance, edited by Roger Clarke and Richard Wright, 129-142. Sydney, Australia: Australian Computer Society, [...]

The provision of free internet access is a topic of growing importance in our increasingly digital society. The internet has transformed the way we communicate, access information, and engage with the world. However, access to [...]

In the digital age, we find ourselves immersed in a sea of information and entertainment, bombarded by a constant stream of images, videos, and messages. Neil Postman's prophetic book, "Amusing Ourselves to Death," published in [...]

It was a time when personal computer was a set consisting of monitor and single choice of technology, but it wasn’t good like using only one thing on technology. And after that was a revolutionary change of different computing [...]

Technology revolves around us; our lives have improved considerably with technology but, relying on them too much can have harmful effects. A research has shown that people can be addicted to these devices very much like [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Photo by Gary Hershorn/Getty

Our tools shape our selves

For bernard stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience.

by Bryan Norton + BIO

It has become almost impossible to separate the effects of digital technologies from our everyday experiences. Reality is parsed through glowing screens, unending data feeds, biometric feedback loops, digital protheses and expanding networks that link our virtual selves to satellite arrays in geostationary orbit. Wristwatches interpret our physical condition by counting steps and heartbeats. Phones track how we spend our time online, map the geographic location of the places we visit and record our histories in digital archives. Social media platforms forge alliances and create new political possibilities. And vast wireless networks – connecting satellites, drones and ‘smart’ weapons – determine how the wars of our era are being waged. Our experiences of the world are soaked with digital technologies.

But for the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler, one of the earliest and foremost theorists of our digital age, understanding the world requires us to move beyond the standard view of technology. Stiegler believed that technology is not just about the effects of digital tools and the ways that they impact our lives. It is not just about how devices are created and wielded by powerful organisations, nation-states or individuals. Our relationship with technology is about something deeper and more fundamental. It is about technics .

According to Stiegler, technics – the making and use of technology, in the broadest sense – is what makes us human. Our unique way of existing in the world, as distinct from other species, is defined by the experiences and knowledge our tools make possible, whether that is a state-of-the-art brain-computer interface such as Neuralink, or a prehistoric flint axe used to clear a forest. But don’t be mistaken: ‘technics’ is not simply another word for ‘technology’. As Martin Heidegger wrote in his essay ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ (1954), which used the German term Technik instead of Technologie in the original title: the ‘essence of technology is by no means anything technological.’ This aligns with the history of the word: the etymology of ‘technics’ leads us back to something like the ancient Greek term for art – technē . The essence of technology, then, is not found in a device, such as the one you are using to read this essay. It is an open-ended creative process, a relationship with our tools and the world.

This is Stiegler’s legacy. Throughout his life, he took this idea of technics, first explored while he was imprisoned for armed robbery, further than anyone else. But his ideas have often been overlooked and misunderstood, even before he died in 2020. Today, they are more necessary than ever. How else can we learn to disentangle the effects of digital technologies from our everyday experiences? How else can we begin to grasp the history of our strange reality?

S tiegler’s path to becoming the pre-eminent philosopher of our digital age was anything but straightforward. He was born in Villebon-sur-Yvette, south of Paris, in 1952, during a period of affluence and rejuvenation in France that followed the devastation of the Second World War. By the time he was 16, Stiegler participated in the revolutionary wave of 1968 (he would later become a member of the Communist Party), when a radical uprising of students and workers forced the president Charles de Gaulle to seek temporary refuge across the border in West Germany. However, after a new election was called and the barricades were dismantled, Stiegler became disenchanted with traditional Marxism, as well as the political trends circulating in France at the time. The Left in France seemed helplessly torn between the postwar existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre and the anti-humanism of Louis Althusser. While Sartre insisted on humans’ creative capacity to shape their own destiny, Althusser argued that the pervasiveness of ideology in capitalist society had left us helplessly entrenched in systems of power beyond our control. Neither of these options satisfied Stiegler because neither could account for the rapid rise of a new historical force: electronic technology. By the 1970s and ’80s, Stiegler sensed that this new technology was redefining our relationship to ourselves, to the world, and to each other. To account for these new conditions, he believed the history of philosophy would have to be rewritten from the ground up, from the perspective of technics. Neither existentialism nor Marxism nor any other school of philosophy had come close to acknowledging the fundamental link between human existence and the evolutionary history of tools.

Stiegler describes his time in prison as one of radical self-exploration and philosophical experimentation

In the decade after 1968, Stiegler opened a jazz club in Toulouse that was shut down by the police a few years later for illegal prostitution. Desperate to make ends meet, Stiegler turned to robbing banks to pay off his debts and feed his family. In 1978, he was arrested for armed robbery and sentenced to five years in prison. A high-school dropout who was never comfortable in institutional settings, Stiegler requested his own cell when he first arrived in prison, and went on a hunger strike until it was granted. After the warden finally acquiesced, Stiegler began taking note of how his relationship to the outside world was mediated through reading and writing. This would be a crucial realisation. Through books, paper and pencils, he was able to interface with people and places beyond the prison walls.

It was during his time behind bars that Stiegler began to study philosophy more intently, devouring any books he could get his hands on. In his philosophical memoir Acting Out (2009), Stiegler describes his time in prison as one of radical self-exploration and philosophical experimentation. He read classic works of Greek philosophy, studied English and memorised modern poetry, but the book that really drew his attention was Plato’s Phaedrus. In this dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus, Plato outlines his concept of anamnesis , a theory of learning that states the acquisition of new knowledge is just a process of remembering what we once knew in a previous life. Caught in an endless cycle of death and rebirth, we forget what we know each time we are reborn. For Stiegler, this idea of learning as recollection would become less spiritual and more material: learning and memory are tied inextricably to technics. Through the tools we use – including books, writing, archives – we can store and preserve vast amounts of knowledge.

After an initial attempt at writing fiction in prison, Stiegler enrolled in a philosophy programme designed for inmates. While still serving his sentence, he finished a degree in philosophy and corresponded with prominent intellectuals such as the philosopher and translator Gérard Granel, who was a well-connected professor at the University of Toulouse-Le Mirail (later known as the University of Toulouse-Jean Jaurès). Granel introduced Stiegler to some of the most prominent figures in philosophy at the time, including Jean-François Lyotard and Jacques Derrida . Lyotard would oversee Stiegler’s master’s thesis after his eventual release; Derrida would supervise his doctoral dissertation, completed in 1993, which was reworked and published a year later as the first volume in his Technics and Time series. With the help of these philosophers and their novel ideals, Stiegler began to reshape his earlier political commitment to Marxist materialism, seeking to account for the ways that new technologies shape the world.

B y the start of the 1970s, a growing number of philosophers and political theorists began calling into question the immediacy of our lived experience. The world around us was no longer seen by these thinkers as something that was simply given, as it had been for phenomenologists such as Immanuel Kant and Edmund Husserl. The world instead presented itself as a built environment composed of things such as roads, power plants and houses, all made possible by political institutions, cultural practices and social norms. And so, reality also appeared to be a construction, not a given.

One of the French philosophers who interrogated the immediacy of reality most closely was Louis Althusser. In his essay ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’ published in 1970, years before Stiegler was taught by him, Althusser suggests that ideology is not something that an individual believes in, but something that goes far beyond the scale of a single person, or even a community. Just as we unthinkingly turn around when we hear our name shouted from behind, ideology has a hold on us that is both automatic and unconscious – it seeps in from outside. Michel Foucault , a former student of Althusser at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, developed a theory of power that functions in a similar way. In Discipline and Punish (1975) and elsewhere, Foucault argues that social and political power is not concentrated in individuals but is produced by ‘discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions’. Foucault’s insight was to show how power shapes every facet of the world, from classroom interactions between a teacher and student to negotiations of a trade agreement between representatives of two different nations. From this perspective, power is constituted in and through material practices, rather than something possessed by individual subjects.

We don’t simply ‘use’ our digital tools – they enter and pharmacologically change us, like medicinal drugs

These are the foundations on which Stiegler assembled his idea of technics. Though he appreciated the ways that Foucault and Althusser had tried to account for technology, he remained dissatisfied by the lack of attention to particular types of technology – not to mention the fact that neither thinker had offered any real alternatives to the forms of power they described. In his book Taking Care of Youth and the Generations (2008), Stiegler explains that he was able to move beyond Foucault with the help of his mentor Derrida’s concept of the pharmakon . In his essay ‘Plato’s Pharmacy’ (1972), Derrida began developing the idea as he explored how our ability to write can create and undermine (‘cure’ and ‘poison’) an individual subject’s sense of identity. For Derrida, the act of writing – itself a kind of technology – has a Janus-faced relationship to individual memory. Though it allows us to store knowledge and experience across vast periods of time, writing disincentivises us from practising our own mental capacity for recollection. The written word short-circuits the immediate connection between lived experience and internal memory. It ‘cures’ our cognitive limits, but also ‘poisons’ our cognition by limiting our abilities.

In the late 20th century, Stiegler began applying this idea to new media technologies, such as television, which led to the development of a concept he called pharmacology – an idea that suggests we don’t simply ‘use’ our digital tools. Instead, they enter and pharmacologically change us, like medicinal drugs. Today, we can take this analogy even further. The internet presents us with a massive archive of formatted, readily accessible information. Sites such as Wikipedia contain terabytes of knowledge, accumulated and passed down over millennia. At the same time, this exchange of unprecedented amounts of information enables the dissemination of an unprecedented amount of misinformation, conspiracy theories, and other harmful content. The digital is both a poison and a cure, as Derrida would say.

This kind of polyvalence led Stiegler to think more deliberately about technics rather than technology. For Stiegler, there are inherent risks in thinking in terms of the latter: the more ubiquitous that digital technologies become in our lives, the easier it is to forget that these tools are social products that have been constructed by our fellow humans. How we consume music, the paths we take to get from point A to point B , how we share ourselves with others, all of these aspects of daily life have been reshaped by new technologies and the humans that produce them. Yet we rarely stop to reflect on what this means for us. Stiegler believed this act of forgetting creates a deep crisis for all facets of human experience. By forgetting, we lose our all-important capacity to imagine alternative ways of living. The future appears limited, even predetermined, by new technology.

I n the English-speaking world, Stiegler is best known for his first book Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus (1994). In the first sentence, he highlights the vital link between our understanding of the technologies we use and our capacity to imagine the future. ‘The object of this work is technics,’ he writes, ‘apprehended as the horizon of all possibility to come and of all possibility of a future.’ He views our relationship with tools as the determining force for all future possibilities; technics is the defining feature of human experience, one that has been overlooked by philosophers from Plato and Aristotle down to the present. While René Descartes, Husserl and other thinkers asked important questions about consciousness and lived experience (phenomenology), and the nature of truth (metaphysics) or knowledge (epistemology), they failed to account for the ways that technologies help us find – or guide us toward – answers to these questions. In the history of philosophy, ‘Technics is the unthought,’ according to Stiegler.

To further stress the importance of technics, Stiegler turns to the creation myth told by the Greek poet Hesiod in Works and Days , written around 700 BCE . During the world’s creation, Zeus asks the Titan Epimetheus to distribute individual talents to each species. Epimetheus gives wings to birds so they can fly, and fins to fish so they can swim. By the time he gets to humans, however, Epimetheus has no talents left over. Epimetheus, whose name (according to Stiegler) means the ‘forgetful one’ in Greek, turns to his brother Prometheus for help. Prometheus then steals fire from the gods, presenting it to humans in place of a biological talent. Humans, once more, are born out of an act of forgetting, just like in Plato’s theory of anamnesis. The difference with Hesiod’s story is that technics here provides a material basis for human experience. Bereft of any physiological talents, Homo sapiens must survive by using tools, beginning with fire.

Factories, server farms and even psychotropic drugs possess the capacity to poison or cure our world

The pharmacology of technics, for Stiegler, presents opportunities for positive or negative relationships with tools. ‘But where the danger lies,’ writes the poet Friedrich Hölderlin in a quote Stiegler often turned to, ‘also grows the saving power.’ While Derrida focuses on the ability of the written word to subvert the sovereignty of the individual subject, Stiegler widens this understanding of pharmacology to include a variety of media and technologies. Not just writing, but factories, server farms and even psychotropic drugs possess the pharmacological capacity to poison or cure our world and, crucially, our understanding of it. Technological development can destroy our sense of ourselves as rational, coherent subjects, leading to widespread suffering and destruction. But tools can also provide us with a new sense of what it means to be human, leading to new modes of expression and cultural practices.

In Symbolic Misery, Volume 2: The Catastrophe of the Sensible (2015) , Stiegler considers the effect that new technologies, especially those accompanying industrialisation, have had on art and music. Industry, defined by mass production and standardisation, is often regarded as antithetical to artistic freedom and expression. But Stiegler urges us to take a closer look at art history to see how artists responded to industrialisation. In response to the standardising effects of new machinery, for example, Marcel Duchamp and other members of the 20th-century avant-garde used industrial tools to invent novel forms of creative expression. In the painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2 (1912), Duchamp employed the new temporal perspectives made possible by photography and cinema to paint a radically different kind of portrait. Inspired by the camera’s ability to capture movement, frame by frame, Duchamp paints a nude model who appears in multiple instants at once, like a series of time-lapse photographs superimposed onto each other. The image became an immediate sensation, an icon of modernity and the resulting entanglement of art and industrial technology.

Technical innovations are never without political and social implications for Stiegler. The phonograph, for example, may have standardised classical musical performances after its invention in the late 1800s, but it also contributed to the development of jazz, a genre that was popular among musicians who were barred from accessing the elite world of classical music. Thanks to the gramophone, Black musicians such as the pianist and composer Duke Ellington were able to learn their instruments by ear, without first learning to read musical notation. The phonograph’s industrialisation of musical performance paradoxically led to the free-flowing improvisation of jazz performers.

T echnics draws our attention to the world-making capabilities of our tools, while reminding us of the constructed nature of our technological reality. Stiegler’s capacious understanding of technics, encompassing everything from early agricultural tools to the television set, does not disregard new innovations, either. In 2006, Stiegler founded the Institute for Research and Innovation, an organisation at the Centre Pompidou in Paris devoted to exploring the impact digital technology has on contemporary society. Stiegler’s belief in the power of technology to shape the world around us has often led to the charge that he is a techno-determinist who believes the entire course of history is shaped by tools and machines. It’s true that Stiegler thinks technology defines who we are as humans, but this process does not always lock us into predetermined outcomes. Instead, it simultaneously provides us with a material horizon of possible experience. Stiegler’s theory of technics urges us to rethink the history of philosophy, art and politics in order that we might better understand how our world has been shaped by technology. And by acquiring this historical consciousness, he hopes that we will ultimately design better tools, using technology to improve our world in meaningful ways.

This doesn’t mean Stiegler is a techno-optimist, either, who blindly sees digital technology as a panacea for our problems. One particular concern he expresses about digital technology is its capacity to standardise the world we inhabit. Big data, for Stiegler, threatens to limit our sense of what is possible, rather than broadening our horizons and opening new opportunities for creative expression. Just as Hollywood films in the 20th century manufactured and distributed the ideology of consumer capitalism to the rest of the globe, Stiegler suggests that tech firms such as Google and Apple often disseminate values that are hidden from view. A potent example of this can be found in the first fully AI-judged beauty pageant. As discussed by the sociologist Ruha Benjamin in her book Race After Technology (2019), the developers of Beauty.AI advertised the contest as an opportunity for beauty to be judged in a way that was free of prejudice. What they found, however, was that the tool they had designed exhibited an overwhelming preference for white contestants.

The digital economy doesn’t always offer desirable alternatives as former ways of working and living are destroyed

In Automatic Society, Volume 1: The Future of Work (2016), Stiegler shows how big data can standardise our world by reorganising work and employment. Digital tools were first seen as a disruptive force that could break the monotonous rhythms of large industry, but the rise of flexible forms of employment in the gig economy has created a massive underclass. A new proletariat of Uber drivers and other precarious workers now labour under extremely unstable conditions. They are denied even the traditional protections of working-class employment. The digital economy doesn’t always offer desirable alternatives as former ways of working and living are destroyed.

A particularly pressing concern Stiegler took up before his untimely death in 2020 is the capacity of digital tools to surveil us. The rise of big tech firms such as Google and Amazon has meant the intrusion of surveillance tools into every aspect of our lives. Smart homes have round-the-clock video feeds, and marketing companies spend billions collecting data about everything we do online. In his last two books published in English, The Neganthropocene ( 2018 ) and The Age of Disruption: Technology and Madness in Computational Capitalism ( 2019 ), Stiegler suggests that the growth of widespread surveillance tools is at odds with the pharmacological promise of new technology. Though tracking tools can be useful by, for example, limiting the spread of harmful diseases, they are also used to deny us worlds of possible experience.

Technology, for better or worse, affects every aspect of our lives. Our very sense of who we are is shaped and reshaped by the tools we have at our disposal. The problem, for Stiegler, is that when we pay too much attention to our tools, rather than how they are developed and deployed, we fail to understand our reality. We become trapped, merely describing the technological world on its own terms and making it even harder to untangle the effects of digital technologies and our everyday experiences. By encouraging us to pay closer attention to this world-making capacity, with its potential to harm and heal, Stiegler is showing us what else is possible. There are other ways of living, of being, of evolving. It is technics, not technology, that will give the future its new face.

Family life

A patchwork family

After my marriage failed, I strove to create a new family – one made beautiful by the loving way it’s stitched together

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Stories and literature

Terrifying vistas of reality

H P Lovecraft, the master of cosmic horror stories, was a philosopher who believed in the total insignificance of humanity

Sam Woodward

The dangers of AI farming

AI could lead to new ways for people to abuse animals for financial gain. That’s why we need strong ethical guidelines

Virginie Simoneau-Gilbert & Jonathan Birch

Thinkers and theories

A man beyond categories

Paul Tillich was a religious socialist and a profoundly subtle theologian who placed doubt at the centre of his thought

War and peace

Legacy of the Scythians

How the ancient warrior people of the steppes have found themselves on the cultural frontlines of Russia’s war against Ukraine

Peter Mumford

More From Forbes

What is the digital age and what does it mean.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

The Digital Age

As books like Dignity In The Digital Age (Simon & Schuster) 2022) by Congressman Ro Khanna begin to appear, as talk of “the digital age” becomes commonplace, and as executives grapple with “digital disruption” as their top management challenge, it can seem odd that no one seems to know what exactly is “the digital age”, or what it means.

The Birth Of The Industrial Era

Some light can be shed on the cause of this silence by looking at the arrival of the last great age, the Industrial Era, some 250 years ago. Even in retrospect, there is no agreement among historians as to what we are talking about with “the Industrial Era”.

Some historians see it primarily as an economic phenomenon that began in Britain, starting with mechanized spinning in the 1780s, and only reaching the rest of Europe by the mid-19th century . Others see it as an engineering and technological phenomenon, starting with mechanized spinning in the 1780s with high rates of growth in steam power and iron production occurring after 1800. Some see it as the beginning of management as a kind of expertise. Some writers see it as an offshoot of improved agricultural productivity that freed up agriculture workers to be employed elsewhere the economy. Others adopt a gradualist perspective and suggest that there was no sudden transformation at all, but rather a confluence of many factors. Each discipline tends to pursue its own perspective as “the” way to understand the era, to some extent distracting from the fact that the era was the result of “all of the above.’

Adam Smith and The Wealth of Nations (1776)

Back then, in the 1770s, describing all the implications of the new era would have been like trying to tell the lords and ladies living in luxury on their grand manors and agricultural estates, with all their tenant farmers touching their forelocks as these aristocrats drove by in their grand horse-drawn carriages, that they were going to be replaced by crass upstart businessmen, who would be tearing their aristocratic world apart, driving their tenant farmers off their estates and into the cities to undertake boring repetitive work known as "jobs.” Even less plausible would be telling the lords and ladies of their eventual destiny in the new era as tour guides of their grand manors for the hoi polloi. It would have been a story that would have been too complex and too horrible to contemplate, let alone write about.

The Scottish philosopher and economist, Adam Smith, took a stab at it, but even he could only see or tell part of the story in his masterwork, The Wealth of Nations (1776). There was only so much news that was fit to print. And a lot of the big things had yet to happen. A factory that made pins more efficiently than before hardly seemed like headline news.

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

Even so, Smith's Wealth of Nations (1776) covered a lot of ground. It was part economics textbook, part management textbook, part finance textbook, part social commentary on how this was all playing out, and part an example of early futurology. That combination was possibly the best that could be done at the time with the onset of a phenomenon as vast as a new age.

Almost by definition, any book that tried to describe the whole shebang would not have fitted into any existing category of book. If The Wealth of Nations book had been shoehorned into any existing category of book, it would never have had the impact that it did have. It was because the book was multi-faceted that readers could begin to grasp the enormous implications of what had begun to happen.

After a few decades, the landscape became clearer. For those with eyes to see, the era felt like a revolution. Thus in 1813, the Scottish statistician Patrick Colquhoun wrote in “ A Treatise on the wealth, power and resources of the British empire ” (London, 1813): “It is impossible to contemplate the progress of manufactures in Great Britain within the last thirty years without wonder and astonishment. Its rapidity, particularly since the commencement of the French revolutionary war, exceeds all credibility. the improvement of the steam engines, but above all the facilities afforded to the great branches of the woolen and cotton [manufactures] by ingenious machinery, invigorated by capital and skill, are beyond all calculation, these machines are rendered applicable to silk, linen, hosiery and various other branches.”

Thus, by the early 1800s, the well-to-do could now begin to experience the impact of the new era, though it would be another half century before the average citizen would see major gains.

Explaining the Digital Age

Today, with the emerging new age, which is most commonly—and inaccurately—called “the digital age” , each book or article has so far covered tiny fragments of the whole. There is writing on the amazing new technologies that are now available. There is writing on how our lives are being transformed . There is writing on aspects of the management changes that are needed to succeed with those technologies. There is writing on how corporate finance has been transformed. There is writing on how individual sectors have been affected. There is writing on the potential gains that are available, as well as on the failure of many existing firms to take advantage of those opportunities, resulting in “digital disruption .” There is writing on the need to update the foundations of economics to incorporate what is happening. There is writing on the missteps of the digital winners and the risks of the new age, as well as what should be done to regulate or ameliorate some of the negative impacts. There is futurist writing that talks about where this is all heading .

What is lacking, and what is needed, is writing that presents a coherent picture of all the various aspects of the new age in a way that it can be understood, and dealt with, rationally, in its entirety.

And read also:

Microsoft CEO Nadella’s Brilliant Depiction Of The Digital Age

How To Thrive Amid Digital Disruption

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Student Writing in the Digital Age

Essays filled with “LOL” and emojis? College student writing today actually is longer and contains no more errors than it did in 1917.

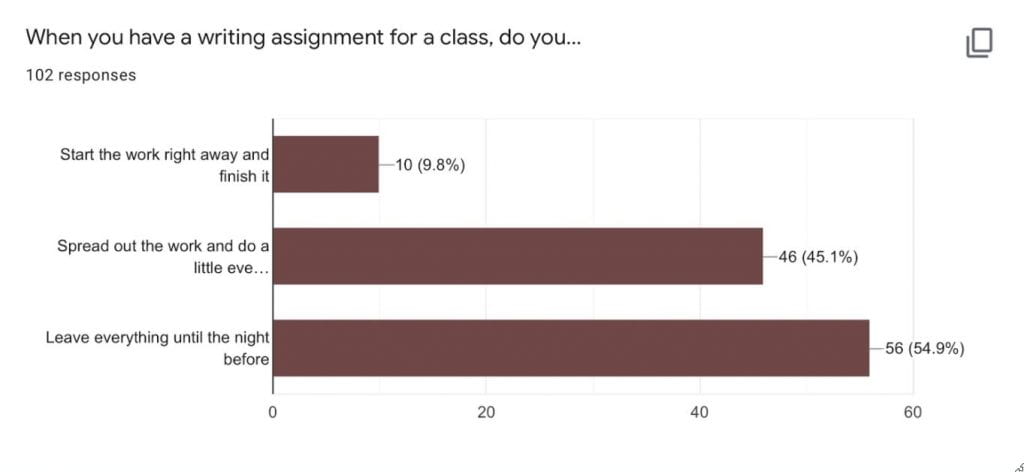

“Kids these days” laments are nothing new, but the substance of the lament changes. Lately, it has become fashionable to worry that “kids these days” will be unable to write complex, lengthy essays. After all, the logic goes, social media and text messaging reward short, abbreviated expression. Student writing will be similarly staccato, rushed, or even—horror of horrors—filled with LOL abbreviations and emojis.

In fact, the opposite seems to be the case. Students in first-year composition classes are, on average, writing longer essays (from an average of 162 words in 1917, to 422 words in 1986, to 1,038 words in 2006), using more complex rhetorical techniques, and making no more errors than those committed by freshman in 1917. That’s according to a longitudinal study of student writing by Andrea A. Lunsford and Karen J. Lunsford, “ Mistakes Are a Fact of Life: A National Comparative Study. ”

In 2006, two rhetoric and composition professors, Lunsford and Lunsford, decided, in reaction to government studies worrying that students’ literacy levels were declining, to crunch the numbers and determine if students were making more errors in the digital age.

They began by replicating previous studies of American college student errors. There were four similar studies over the past century. In 1917, a professor analyzed the errors in 198 college student papers; in 1930, researchers completed similar studies of 170 and 20,000 papers, respectively. In 1986, Robert Connors and Andrea Lunsford (of the 2006 study) decided to see if contemporary students were making more or fewer errors than those earlier studies showed, and analyzed 3,000 student papers from 1984. The 2006 study (published in 2008) follows the process of these earlier studies and was based on 877 papers (one of the most interesting sections of “Mistakes Are a Fact of Life” discusses how new IRB regulations forced researchers to work with far fewer papers than they had before.

Remarkably, the number of errors students made in their papers stayed consistent over the past 100 years. Students in 2006 committed roughly the same number of errors as students did in 1917. The average has stayed at about 2 errors per 100 words.

What has changed are the kinds of errors students make. The four 20th-century studies show that, when it came to making mistakes, spelling tripped up students the most. Spelling was by far the most common error in 1986 and 1917, “the most frequent student mistake by some 300 percent.” Going down the list of “top 10 errors,” the patterns shifted: Capitalization was the second most frequent error 1917; in 1986, that spot went to “no comma after introductory element.”

In 2006, spelling lost its prominence, dropping down the list of errors to number five. Spell-check and similar word-processing tools are the undeniable cause. But spell-check creates new errors, too: The new number-one error in student writing is now “wrong word.” Spell-check, as most of us know, sometimes corrects spelling to a different word than intended; if the writing is not later proof-read, this computer-created error goes unnoticed. The second most common error in 2006 was “incomplete or missing documentation,” a result, the authors theorize, of a shift in college assignments toward research papers and away from personal essays.

Additionally, capitalization errors have increased, perhaps, as Lunsford and Lunsford note, because of neologisms like eBay and iPod. But students have also become much better at punctuation and apostrophes, which were the third and fifth most common errors in 1917. These had dropped off the top 10 list by 2006.

The study found no evidence for claims that kids are increasingly using “text speak” or emojis in their papers. Lunsford and Lunsford did not find a single such instance of this digital-era error. Ironically, they did find such text speak and emoticons in teachers’ comments to students. (Teachers these days?)

The most startling discovery Lunsford and Lunsford made had nothing to do with errors or emojis. They found that college students are writing much more and submitting much longer papers than ever. The average college essay in 2006 was more than double the length of the average 1986 paper, which was itself much longer than the average length of papers written earlier in the century. In 1917, student papers averaged 162 words; in 1930, the average was 231 words. By 1986, the average grew to 422 words. And just 20 years later, in 2006, it jumped to 1,038 words.

Why are 21st-century college students writing so much more? Computers allow students to write faster. (Other advances in writing technology may explain the upticks between 1917, 1930, and 1986. Ballpoint pens and manual and electric typewriters allowed students to write faster than inkwells or fountain pens.) The internet helps, too: Research shows that computers connected to the internet lead K-12 students to “conduct more background research for their writing; they write, revise, and publish more; they get more feedback on their writing; they write in a wider variety of genres and formats; and they produce higher quality writing.”

The digital revolution has been largely text-based. Over the course of an average day, Americans in 2006 wrote more than they did in 1986 (and in 2015 they wrote more than in 2006). New forms of written communication—texting, social media, and email—are often used instead of spoken ones—phone calls, meetings, and face-to-face discussions. With each text and Facebook update, students become more familiar with and adept at written expression. Today’s students have more experience with writing, and they practice it more than any group of college students in history.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

In shifting from texting to writing their English papers, college students must become adept at code-switching, using one form of writing for certain purposes (gossiping with friends) and another for others (summarizing plots). As Kristen Hawley Turner writes in “ Flipping the Switch: Code-Switching from Text Speak to Standard English ,” students do know how to shift from informal to formal discourse, changing their writing as occasions demand. Just as we might speak differently to a supervisor than to a child, so too do students know that they should probably not use “conversely” in a text to a friend or “LOL” in their Shakespeare paper. “As digital natives who have had access to computer technology all of their lives, they often demonstrate in theses arenas proficiencies that the adults in their lives lack,” Turner writes. Instructors should “teach them to negotiate the technology-driven discourse within the confines of school language.”

Responses to Lunsford and Lunsford’s study focused on what the results revealed about mistakes in writing: Error is often in the eye of the beholder . Teachers mark some errors and neglect to mention (or find) others. And, as a pioneering scholar of this field wrote in the 1970s, context is key when analyzing error: Students who make mistakes are not “indifferent…or incapable” but “beginners and must, like all beginners, learn by making mistakes.”

College students are making mistakes, of course, and they have much to learn about writing. But they are not making more mistakes than did their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Since they now use writing to communicate with friends and family, they are more comfortable expressing themselves in words. Plus, most have access to technology that allows them to write faster than ever. If Lunsford and Lunsford’s findings about the average length of student papers stays true, today’s college students will graduate with more pages of completed prose to their name than any other generation.

If we want to worry about college student writing, then perhaps what we should attend to is not clipped, abbreviated writing, but overly verbose, rambling writing. It might be that editing skills—deciding what not to say, and what to delete—may be what most ails the kids these days.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

More Stories

- Seeing the World Through Missionaries’ Eyes

Meet Saint Wilgefortis, the Bearded Virgin

Nice Guy Spinoza Finishes…First?

A Body in the Bog

Recent posts.

- Beware the Volcanoes of Alaska (and Elsewhere)

- The Border Presidents and Civil Rights

- The Genius of Georgette Chen

- Eurasianism: A Primer

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Our Mission

How the Digital Age Is Affecting Students

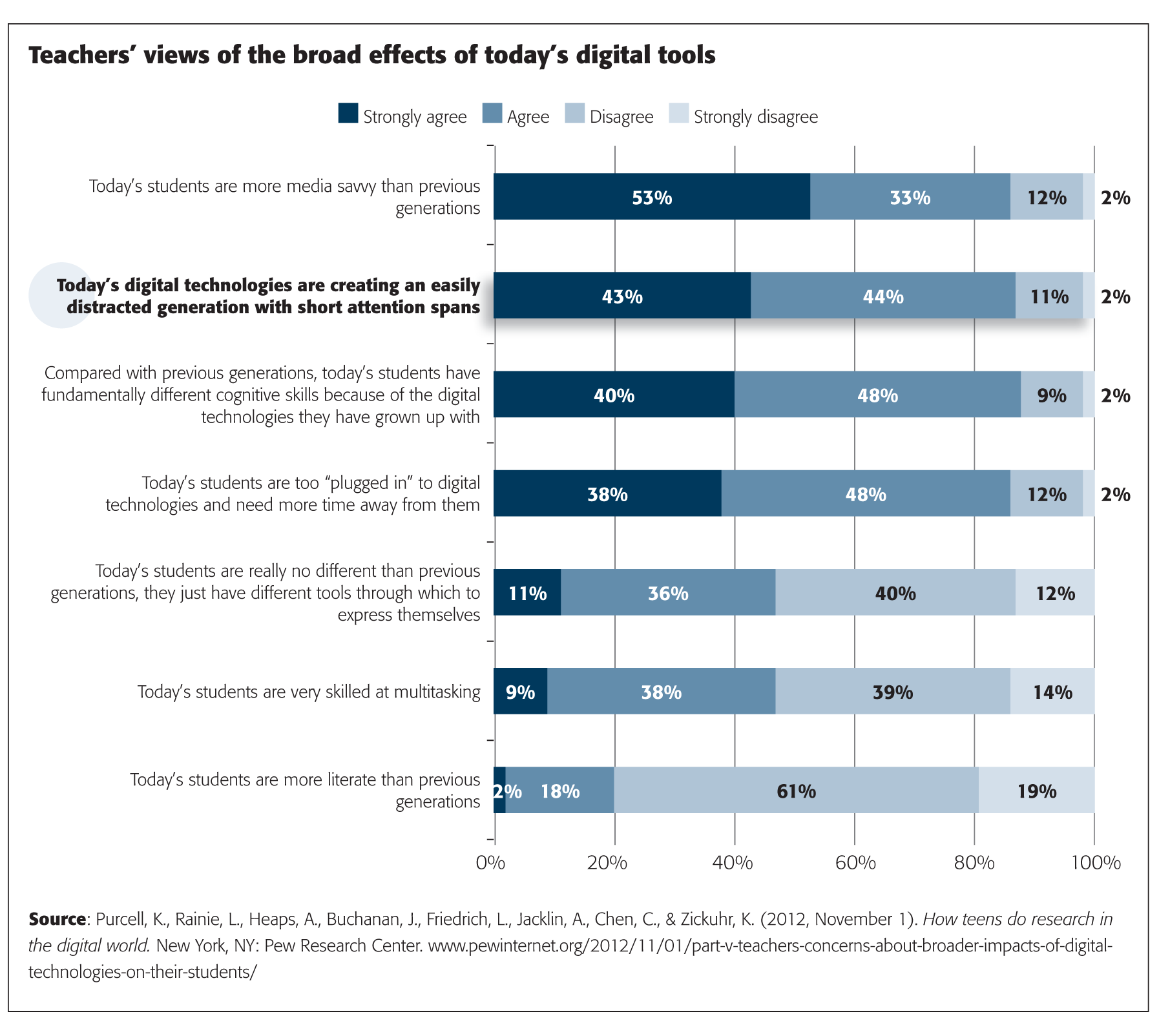

Five books that give insight into how social media and technology are shaping today’s students and their learning.

Teachers don’t have to look far to see how changes in technology and social media are shaping students and influencing classrooms. We watch kids obsess over the latest apps as they chat before class. We marvel at the newest slang edging its way into student essays, and wonder at the ways constant smartphone communication is shaping students’ friendships, bullying, and even study habits.

To understand the internet-savvy students who fill our classrooms and the changing landscape of social media they inhabit, we need more than hot new gadgets or expensive educational software. The book list below is a starting point if you’re looking for insight into how the digital age is shaping students and ideas about how you can respond in the classroom.

Each book was chosen for its combination of research, story, and applicability to the classroom. Grab one or two to help you invent new strategies to reach students or reimagine your application of technology in your classroom.

Social Media

If you’ve ever wondered what students are doing with all their time on the internet, It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens is for you. Author danah boyd dissects how and why kids rush to the online world. Using student interviews and stories, boyd describes the ways youngsters use social media to connect, escape, and eke out a little privacy away from their parents and teachers. She includes a chapter on how the internet has shaped young people’s understanding of personal and public spaces. Read this book if you want to help students optimize the knowledge and skills they already have as digital natives.

A clinical psychologist and researcher at MIT, Sherry Turkle isn’t against the smartphones our students love so much. But she is worried that the obsession with phones—and the texting and social media posting they enable—is impacting in-person discussion and deep conversation. In her book Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age , Turkle claims that students’ communication skills have changed. Her suggestions for taking back in-person conversation in a digital world can shape collaborative classrooms and guide teachers on how to help students improve peer-to-peer interactions.

Social media and the free flow of information have also influenced the language we use every day. In A World Without ‘Whom’: The Essential Guide to Language in the Buzzfeed Age , Emmy Favilla lays out a case for language shaped by the internet. This entertaining and informative 2017 book is peppered with pop culture examples ready for use in class, though like all pop culture references they’ll quickly become dated. Favilla’s writing is pragmatic; she offers advice on where to hold the line on traditional language and when readability and appeal to a new generation might be more important. As Favilla puts it, “We’re all just trying to be heard here.” The book is a timely reminder that social-media-fueled language innovation deserves some classroom discussion.

If you’re eager to understand larger trends affecting young students, pick up Jean Twenge’s iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood . Drawing from large data sets and longitudinal studies, Twenge examines everything from SAT scores to rates of loneliness. Her research-heavy book offers helpful hints about the impact of technology and other cultural changes. Read this book if you want to brainstorm about how to adapt classes and school structures to meet student needs. To bring students in on the conversation, consider using Twenge’s easy-to-read graphs as discussion kick-starters or as a way to provide historical context to current trends.

If you want to reimagine the way computers and video games might be used in the classroom, check out David Williamson Shaffer’s book How Computer Games Help Children Learn . A professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Shaffer believes that video games can help schools foster creative thinking, problem solving, and strategic decision making. After all, making mistakes and trying out innovative strategies are less risky in a game than in real life. And even reluctant learners will often dive eagerly into video games. A lot has changed since the book’s publication in 2007, but its ideas—about what students can learn from video games, how video games engage students, and what issues to avoid—can guide you toward thoughtful, effective video game use.

Our students are steeped in the internet, social media, and all types of technological innovations, and it’s time for schools and teachers to carefully examine how these things interact with curriculum and learning.

- About PDK International

- About Kappan

- Permissions

- About The Grade

- Writers Guidelines

- Upcoming Themes

- Artist Guidelines

- Subscribe to Kappan

Select Page

Reading in a digital age

By Naomi S. Baron | Oct 9, 2017 | Feature Article

Even millennials acknowledge that whether you read on paper or a digital screen affects your attention on words and the ideas behind them.What are the implications for how we teach?

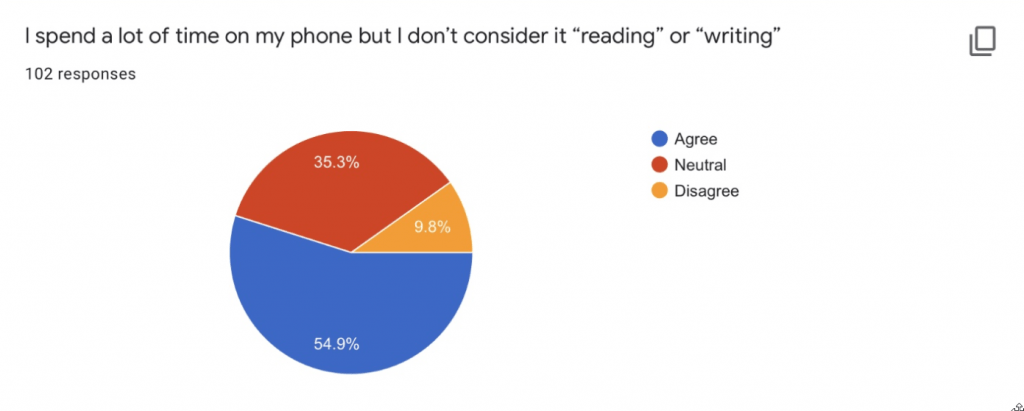

The digital revolution has done much to reshape how students read, write, and access information in school. Once-handwritten essays are now word-processed. Encyclopedias have yielded to online searches. One-size-fits-all teaching is tilting toward personalized learning. And a growing number of assignments ask students to read on digital screens rather than in print.

Yet how much do we actually know about the educational implications of this emphasis on using digital media? In particular, when it comes to reading, do digital screens make it easier or harder for students to pay careful attention to words and the ideas behind them, or is there no difference from print?

Over the past decade, researchers in various countries have been comparing how much readers comprehend and remember when they read in each medium. In nearly all cases, there was essentially no difference between the testing scenarios. (See Baron, Calixte, & Havewala, 2017 for a review.) However, such findings need to be taken with a grain of salt. These studies have typically focused on captive research subjects, mostly college students who commonly are paid to participate in an experiment or who participate to fill a course requirement. Ask them to read passages and then answer SAT-style comprehension questions, and they tend to do so reasonably carefully, whether they read on a screen or on paper. Under those conditions, it’s not surprising that their performance would be consistent across platforms.

But the devil may lie in the details. When researchers have altered the testing conditions or the types of questions they ask, discrepancies have appeared, suggesting that the medium does in fact matter. For example, Ackerman and Goldsmith (2011) observed that when participants could choose how much time to spend on digital versus print reading, they devoted less to reading onscreen and had lower comprehension scores. Schugar and colleagues (2011) found that participants reported using fewer study strategies (such as highlighting, note-taking, or bookmarking) when reading digitally. Kaufman and Flanagan (2016) noted that when reading in print, study participants did better answering abstract questions that required inferential reasoning; by contrast, participants scored better reading digitally when answering concrete questions. Researchers at the University of Reading (Dyson & Haselgrove, 2000) observed that reading comprehension declined when students were scrolling as they read, rather than focusing on stationary chunks of text.

What about research with younger children? Schugar and Schugar found that middle grades students comprehended more when reading print than when using e-books on an iPad (Paul, 2014) — interactive features of the digital platform apparently distracted readers from the textual content. However, the same researchers observed that among K-6 readers, e-books generated a higher level of engagement (Schugar, Smith, & Schugar, 2013). Working with high school students in Norway, Anne Mangen and her colleagues (2013) concluded that print yielded better comprehension scores. Mangen argues that print makes it easier for students to create cognitive maps of the entire passage they are reading.

For educators, though, the real question is not how students perform in experiments. More important is what they do when reading on their own: Do they take as much time reading in both media? Do they read as carefully? In short, in their everyday lives, how much and what sort of attention do they pay to what they are reading?

Questions about reading in a digital age

History is strewn with examples of people worrying that new technologies will undermine older skills. In the late 5th century BC, when the spread of writing was challenging an earlier oral tradition, Plato expressed concern (in the Phaedrus) that “trust in writing . . . will discourage the use of [our] own memory.” Writing has proven an invaluable technology. Digital media have as well. These new tools make it possible for millions of people to have access to texts that would otherwise be beyond their reach, financially or physically. Computer-driven devices enable us to expand our scope of educational and recreational experience to include audio and visual materials, often on demand. But as with writing, it’s an empirical question what the pros and cons are of the old and the new. Writing is a vital cultural tool, but there is little doubt it discourages memory skills.

When we think about the educational implications of digital reading, we need to study the issue with open minds, not make presuppositions about advantages and disadvantages.

To help forward this exploration, my own research has been tackling three intertwined questions about reading in a digital age. First, what do readers tell us directly about their print versus digital reading habits? Second, what else do readers reveal about their attitudes toward reading in print versus onscreen, and what can we infer about how well they pay attention when reading in each medium? The third question is more broad-stroked: In the current technological climate, are we changing the very notion of what it means to read?

Students are more likely to multitask when reading onscreen than in print — especially in the U.S. where 85% reported multitasking when reading digitally, compared with 26% for print.

I’ve been investigating these questions for about a half-dozen years, beginning with some pilot studies in the U.S. (Baron, 2013) and continuing with surveys (between 2013 and 2015) of more than 400 university students from the U.S., Japan, Germany, Slovakia, and India. Participants were enrolled in classes taught by colleagues, or they were classmates of one of my research assistants. Everyone was between age 18 and 26 (mean age: 21). About two-thirds were female and one-third male. (For study details, see Baron, Calixte, & Havewala, 2017.) Though my study participants were university students, I suspect that most issues at play are relevant for younger readers who have mastered the skills we would expect of middle-school students and above. Use of digital technologies is now ubiquitous among both adolescents and young adults, and teachers at all levels are increasingly assigning e-books (or online articles) rather than print.

The study consisted of three sets of questions. In the first set, we asked students:

- How much time they spent reading in print versus onscreen;• Whether cost was a factor in their choice of reading platform;

- In which medium they were more likely to reread;

- Whether text length influenced their platform choice;

- How likely they were to multitask when reading in each medium; and

- In which medium they felt they concentrated best.

In the next set, we asked what students liked most — and least — about reading in each medium. Finally, we gave participants the opportunity to offer additional comments.

Print versus digital reading habits

Here are the main takeaways of what students in the study reported in the first set of questions about their reading habits:

Time reading in print versus onscreen

Overall, participants reported spending about two-thirds of their time reading in print, both for schoolwork and pleasure. There was consider-able variation across countries, with the Japanese doing the most reading onscreen. In considering these numbers, especially for academic reading, we need to keep in mind that sometimes reading assignments are only available in one medium or the other, so students are not making independent choices.

More than four-fifths of the participants said that if cost were the same, they would choose to read in print rather than onscreen. This finding was particularly strong for academic reading and especially high in Germany (94%). Students (and for that matter, K-12 school systems) often cite cost as the reason for selecting digital rather than print textbooks. It’s therefore telling that if cost is removed from the equation, digital millennials commonly prefer print.

Not everyone in the study reread — either for schoolwork or for pleasure. Among those who did, six out of ten indicated they were more likely to reread print. Fewer than two out of ten choose digital, while the rest said both media were equally likely. Rereading is relevant to the issue of attention since a second reading offers opportunities for review or reflection.

Text length

When the amount of text is short, participants displayed mixed preferences, both when reading academic works or for pleasure. However, with longer texts, more than 86% preferred print for schoolwork and 78% when reading for pleasure. Preference for reading longer works in print has been reported in multiple studies. As Farinosi and colleagues (2016) observed, “If the text requires strategic reading, such as papers, essays, books, the paper version is preferred” (p. 417).

Multitasking

Students reported being more likely to multitask when reading onscreen than in print. Responses from the U.S. participants were particularly stark, with 85% indicating they multitasked when reading digitally, compared with 26% for print. The detrimental cognitive effects of multitasking are well known (e.g., Carrier et al., 2015). We can reasonably infer that students who multitask while reading are less likely to be paying close attention to the text than those who don’t.

Concentration

The most dramatic finding for this set of questions came in response to the query about the platform on which students felt they concentrated best. Selecting from print, computer, tablet, e-reader, or mobile phone, 92% said it was easiest to concentrate when reading print.

Paying attention to reading

Students provided open-ended comments to the second set of questions, which asked what they liked most and least about reading in print and onscreen. In these responses, students praised the physicality of print but grumbled that it was not easily searchable. They complained that reading onscreen gave them eyestrain but enjoyed its convenience.

They also had telling things to say about the cognitive consequences of reading in hardcopy versus onscreen. Of all the “like least” comments about reading digitally, 21% were cognitive in nature. Nearly all these comments talked about perceived distraction or lack of concentration. U.S. students were especially vocal: Nearly 43% of their “like least” comments about reading digitally concerned distraction or lack of concentration. When asked what they “liked most” about reading in print, respondents said, “It’s easier to focus,” I “feel like the content sticks in the head more easily,” “reading in hardcopy makes me focus more on what I am reading,” and “I feel like I understand it more [when reading in print].”

In their additional comments (the last question category), study participants wrote about how long it takes to read the same length text on the two platforms. One student observed, “It takes more time to read the same number of pages in print comparing to digital,” suggesting that the mindset she brings to reading print involves greater (and more time-consuming) attention than the one she brings to reading digitally. In fact, in an earlier pilot study, one student griped that what she “liked least” about reading hardcopy was that “it takes me longer because I read more carefully.”

Unexpectedly, several students said reading in print was boring. In response to the question of what they “liked least” about reading in print, one participant complained that “It becomes boring sometimes,” while another wrote, “it takes time to sit down and focus on the material.” Common sense suggests that if students anticipate that text in print will be boring, they will likely approach it with reduced enthusiasm. Diminished interest sometimes translates into skimming rather than reading carefully and sometimes not doing the assigned reading at all.

Is the nature of reading changing?

The biggest challenge to reading attentively on digital platforms is that we largely use digital devices for quick action: Look up an address, send a Facebook status update, grab the news headlines (but not the meat of the article), multitask between online shopping and writing an essay. When we go to read something substantive on a laptop or e-reader, tablet, or mobile phone, our now-habitualized instincts tell us to move things along.

Coupled with this mindset is an evolving sense that writing is for the here-and-now, not the long haul. Since written communication first emerged (in different places, under different circumstances, at different times), one of its consistent attributes has been that it is a durable form of communication that one we can reread or refer to. Today, a nexus of forces is making writing seem more ephemeral.

A recent Pew Research Center study of news-reading habits (Mitchell et al., 2016) reported that among 18- to 29-year-olds, 50% said they often got news online, compared with only 5% who read print newspapers. While some of us save print news clippings, few archive their online versions. Vast numbers of students choose to rent textbooks (whether digitally or in print), which means the book is out of sight and not available for future consultation after the semester ends. True, K-12 students have long been giving back their print books at the end of the year, and college students have commonly sold books they don’t wish to keep. But my conversations now with students who are dedicated readers indicate they don’t see their college years as the time to start building a personal library.

If cost is removed from the equation, digital millennials commonly prefer print.

What about public or school libraries? Increasingly, budgets are being shifted from print to digital materials. The three primary motivations are space, cost, and convenience. To grow the collection, you don’t need to build another wing. Digital is (commonly) less expensive. And users can access the collection any time of day and anywhere in the world with only an internet connection.

All true. But there are consequences. When I access a library book digitally, I find myself “using” it, not reading it. I make a quick foray to find, for instance, the reference I need for an article I’m writing, and then I exit. Had I held the physical book in my hand, it might have taken longer to find the reference, but I probably would have read entire paragraphs or chapters. Microsoft researcher Abigail Sellen has made a related observation. In studying how people perceive material they read (or store) online, she says they “think of using an e-book, not owning an e-book” (cited in Jabr, 2013).

Savvy students are aware of how the computer FIND function lets them zero in on a specific word or phrase so as to answer a question they have been asked to write about, blithely dismissing the obligation to actually read the full assigned text. Using, not reading. The more we swap physical books for digital ones, the easier it is for students to swoop down and cherry-pick rather than work their way through an argument or story.

Finally, contemporary digital technology is altering the role of reading in education. Film strips of old have been replaced by far more engaging (and educationally enriching) TED Talks and YouTubes, podcasts and audio books. The potential of these digital media is extraordinary, both because of their educational richness and the democratic access they provide. Yet at the same time, we should be figuring out the right curricular balance of video, audio, and textual materials.

Implications for educators

The most important lesson I have learned from my research on reading in print versus digitally is the value of asking users themselves what they like and don’t like — and why — about reading in each medium. Students are acutely aware of the cognitive tradeoffs that many perceive themselves to be making when reading on one platform rather than the other. The issue is not that digital reading necessarily leads us to pay less attention. Rather, it is that digital technologies make it easy (and in a sense encourage us) to approach text with a different mindset than the one most of us have been trained to use while reading print.

We need to ask ourselves how the digital mindset is reshaping students’ (and our own) understanding of what it means to read. Since online technology is tailor-made for searching for information rather than analyzing complex ideas, will the meaning of “reading” become “finding information” rather than “contemplating and understanding”? Moreover, if print is increasingly seen as boring (compared with digital text), will our attention spans while reading print generally diminish?

Conceivably, we might progressively abandon careful reading in favor of what has been called “hyper reading” — in the words of Katherine Hayles (2012), reading that aims “to conserve attention by quickly identifying relevant information so that only relatively few portions of a given text are actually read” (p. 12). To be fair, even academics seem to be taking less time per scholarly article, particularly online articles, than they used to (Tenopir et al., 2009). When it comes to using web sites, studies indicate (Nielsen, 2008) that on average, people are likely reading less than 30% of the words.

The issue of sustained attention extends beyond reading onscreen to other digital media. Patricia Greenfield (2009) has observed that while television, video games, and the internet may foster visual intelligence, “the cost seems to be deep processing: mindful knowledge acquisition, inductive analysis, critical thinking, imagination, and reflection.”

Returning to the physical properties of print: If fewer young adults are building their own book collections and if libraries are increasingly going digital, will writing no longer be seen as a durable medium? Yes, we could always look up something again on a digital device, but do we? If audio and video are gradually supplanting text as sources of education and personal enrichment, how should we think about the future role of text as a vehicle of cultural dissemination?

Digital technology is still in its relative infancy. We know it can be an incredibly useful educational tool, but we need much more research before we can draw firm conclusions about its positive and negative features. In the case of reading, our first task is to make ourselves aware of the effect technology potentially has on how we wrap our minds around the written word when encountered in print versus onscreen. Our second task is to embed that understanding in our larger thinking about the role of writing as a means of communicating and thinking.

Ackerman, R. & Goldsmith, M. (2011). Metacognitive regulation of text learning: On screen versus on paper. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17 (1), 18-32.