What Is a Doctorate Degree?

A doctorate is usually the most advanced degree someone can get in an academic discipline, higher education experts say.

What Is a Doctorate?

Getty Images

It's unwise to apply to a doctoral program if you don't have a clear idea of how you might use a doctorate in your career.

In many academic disciplines, the most advanced degree one can earn is a doctorate. Doctorate degree-holders are typically regarded as authorities in their fields, and many note that a major reason for pursuing a doctorate is to increase professional credibility.

"If someone wants to be respected as an expert in their chosen field, and also wants to have a wider array of options in research, writing, publishing, teaching, administration, management, and/or private practice, a doctorate is most definitely worth considering," Don Martin, who has a Ph.D. in higher education administration , wrote in an email.

A doctoral degree is a graduate-level credential typically granted after multiple years of graduate school, with the time-to-degree varying depending on the type of doctoral program, experts say.

Earning a doctorate usually requires at least four years of effort and may entail eight years, depending on the complexity of a program's graduation requirements. It also typically requires a dissertation, a lengthy academic paper based on original research that must be vetted and approved by a panel of professors and later successfully defended before them for the doctorate to be granted.

Some jobs require a doctorate, such as certain college professor positions, says Eric Endlich, founder of Top College Consultants, an admissions consulting firm that helps neurodivergent students navigate undergraduate and graduate school admissions.

Endlich earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree, commonly known as a Ph.D., from Boston University in Massachusetts. He focused on psychology and notes that a doctoral degree is generally required to be a licensed psychologist.

"Since a Ph.D. is a research-focused degree, it can be advantageous to those seeking high-level research positions in scientific fields such as astrophysics or biotechnology," he says.

How Long it Takes to Get a Doctorate Degree

Martin, founder and CEO of Grad School Road Map, an organization that helps grad school applicants navigate the admissions process, says obtaining a doctorate is often a lengthy endeavor.

"Typically it can take between four and six years to complete any doctoral program," he says. "If comprehensive examinations and a dissertation are part of the graduation requirements, it may take a year or two longer. There is no standard amount of time – some students take seven to 10 years to finish."

Endlich says doctoral degree hopefuls should be aware that completing a dissertation may take a long time, especially if unexpected hurdles arise.

"My dissertation, for example, involved recruiting college students to complete questionnaires, and it took much longer than I anticipated to recruit enough subjects for my study," he says.

The standards for a dissertation, which include the proposal and research, are rigorous and usually involve a review and approval by a faculty committee, says Hala Madanat, vice president for research and innovation at San Diego State University in California.

"As part of dissertation requirements, some programs will require publication of the research in high-impact peer-reviewed journals," Madanat wrote in an email.

Types of Doctoral Degree Programs

According to professors and administrators of doctoral programs, there are two types of doctorates.

Doctor of Philosophy

A doctor of philosophy degree is designed to prepare people for research careers at a university or in industry, and teach students how to discover new knowledge within their academic discipline. Ph.D. degrees are offered in a wide range of academic subjects, including highly technical fields like biology , physics, math and engineering; social sciences like sociology and economics; and humanities disciplines like philosophy.

A Ph.D. is the most common degree type among tenure-track college and university faculty, who are typically expected to have a doctorate. But academia is not the only path for someone who pursues a Ph.D. It's common for individuals with biology doctorates to work as researchers in the pharmaceutical industry, and many government expert positions also require a Ph.D.

Professional or clinical doctorates

These are designed to give people the practical skills necessary to be influential leaders within a specific industry or employment setting, such as business, psychology , education or nursing . Examples of professional doctoral degrees include a Doctor of Business Administration degree, typically known as a DBA; a Doctor of Education degree, or Ed.D.; and a Doctor of Nursing Practice degree, or DNP.

A law degree, known as a juris doctor or J.D., as well as a Doctor of Medicine degree, or M.D., are also considered professional doctorates.

How to Get a Doctorate

Getting a doctorate is challenging. It ordinarily requires a series of rigorous classes in a field of study and then passage of a qualification exam in order to begin work on a dissertation, which is the final project.

Dissertations are difficult to write, says David Harpool, vice president of graduate and online programs at Newberry College in South Carolina. Some research indicates that only about half of doctoral students go on to finish their degree, and a main reason is that many never finish and successfully defend their dissertation

"Many of them are in programs that permit them to earn a master’s on the way to a doctorate," Harpool, who earned a Ph.D. from Saint Louis University in Missouri and a J.D. from the University of Missouri , wrote in an email. "The transition from mastering a discipline to creating new knowledge (or at least applying new knowledge in a different way), is difficult, even for outstanding students."

Learn about how M.D.-Ph.D. programs

There is a often a "huge shift in culture" at doctoral programs compared to undergraduate or master's level programs, says Angela Warfield, who earned a Ph.D. in English from the University of Iowa.

Doctoral professors and students have more of a collaborative relationship where they function as colleagues, she says. And there's pressure on each student to produce "significant and original research."

Many full-time doctoral students work for the school as researchers or teaching assistants throughout their program, so time management is crucial to avoid burnout. However, the dissertation "is by far the biggest battle," she says. The goal is to avoid an "ABD," she says, meaning "all but dissertation."

"In my writing group, we had two motivational slogans: 'ABD is not a degree,' and 'a good dissertation is a done dissertation,'" Warfield, now the principal consultant and founder of admissions consulting firm Compass Academics, wrote in an email.

How Are Doctorate Admissions Decisions Made?

Admissions standards for doctoral programs vary depending on the type of doctorate, experts say.

The quality of a candidate's research is a distinguishing factor in admissions decisions, Madanat says. Meanwhile, leaders of clinical and professional doctorate programs say that the quality of a prospective student's work experience matters most.

Doctoral programs typically expect students to have a strong undergraduate transcript , excellent letters of recommendation and, in some cases, high scores on the Graduate Record Examination , or GRE, Endlich says.

"The size of the programs may be relatively small, and universities need to be sure that applicants will be able to handle the demands of their programs," he says.

Because professional doctorates often require students to come up with effective solutions to systemic problems, eligibility for these doctorates is often restricted to applicants with extensive first-hand work experience with these problems, according to recipients of professional doctorates.

In contrast, it's common for Ph.D. students to begin their programs immediately after receiving an undergraduate degree. The admissions criteria at Ph.D. programs emphasize undergraduate grades, standardized test scores and research projects , and these programs don't necessarily require work experience.

Admissions decisions may also depend on available funding, says Madanat, who works with doctoral students to provide funding, workshops and faculty support to help their research.

Who Is a Good Fit for a Doctoral Program?

Doctoral degree hopefuls "should be interested in making a deep impact on their field, open-minded, eager to learn, curious, adaptable and self-motivated," Madanat says. "Doctoral programs are best suited for those whose goals are to transform and change the fields they are studying and want to make a difference in the way the world is."

Someone who loves to study a subject in great depth, can work alone or in teams, is highly motivated and wants to develop research skills may be a good candidate for a doctoral program, Endlich says.

Because of the tremendous effort and time investment involved in earning a doctorate, experts say it's foolish to apply to a doctoral program if it's unclear how you might use a doctorate in your career.

"The students are being trained with depth of knowledge in the discipline to prepare them for critical thinking beyond the current state of the field," Madanat says. "Students should consider the reasons that they are pursuing a doctoral degree and whether or not it aligns with their future professional goals, their family circumstances and finances."

Rachel D. Miller, a licensed marriage and family therapist who completed a Ph.D. degree in couples and family therapy at Adler University in Illinois in 2023, says pursuing a doctorate required her to make significant personal sacrifices because she had to take on large student loans and she needed to devote a lot of time and energy to her program. Miller says balancing work, home life and health issues with the demands of a Ph.D. program was difficult.

For some students, the financial component may be hard to overlook, Warfield notes.

"Student debt is no joke, and students pursuing graduate work are likely only compounding undergraduate debt," she says. "They need to really consider the payoff potential of the time and money sacrifice."

To offset costs, some programs are fully funded, waiving tuition and fees and providing an annual stipend. Some offer health insurance and other benefits. Students can also earn money by teaching at the university or through fellowships, but those adding more to their plate should possess strong time management skills, experts say.

"Graduate school, and higher education in general, can be brutal on your physical and mental health," Miller wrote in an email.

But Miller says the time and effort invested in her doctoral program paid off by allowing her to conduct meaningful research into the best way to provide therapy to children affected by high-conflict divorce and domestic violence. She now owns a therapy practice in Chicago.

Miller urges prospective doctoral students to reflect on whether getting a doctorate is necessary for them to achieve their dream job. "Really know yourself. Know your purpose for pursuing it, because that's what's going to help carry you through."

Searching for a grad school? Access our complete rankings of Best Graduate Schools.

30 Fully Funded Ph.D. Programs

Tags: graduate schools , education , students , academics

You May Also Like

Law school websites: what to look for.

Gabriel Kuris March 12, 2024

Are You Too Old for Medical School?

Kathleen Franco, M.D., M.S. March 12, 2024

How to Get a Great MBA Recommendation

Cole Claybourn March 8, 2024

MBA Waitlist Strategy: What to Do Next

Andrew Warner March 6, 2024

Tackling the First Year of Med School

Renee Marinelli, M.D. March 5, 2024

How to Reapply to Law School

Gabriel Kuris March 4, 2024

Work With Disabled Populations

Rachel Rizal Feb. 27, 2024

Schools That Teach Integrative Medicine

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn Feb. 27, 2024

Biggest Factors in Law School Admissions

Gabriel Kuris Feb. 26, 2024

Medical School Application Mistakes

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn Feb. 23, 2024

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Online Doctorate Degree Programs / Online Doctor of Education (EdD) — Higher Education Leadership / Doctor of Education – Higher Education Leadership Resources / What is a Doctor of Education (EdD) Program

What Is an EdD? Understanding the Doctorate of Education Program What Is an EdD? Understanding the Doctorate of Education Program What Is an EdD? Understanding the Doctorate of Education Program

Take your next brave step.

Receive information about the benefits of our programs, the courses you'll take, and what you need to apply.

Higher education institutions comprise many different departments, each with their own focus, goals, and needs. Professionals who hold a Doctor of Education (EdD) have the option to move into various leadership roles in each of these different departments. They can work in admissions, as an academic dean, or as an academic officer, to name a few. Those with EdD degrees should have a passion for higher education and want to hold positions in which they deal with the daily challenges and administrative duties of higher education.

In this article, we’ll explore the benefits of an EdD degree, how to earn one, what career options are open to those who have one, and what makes it unique.

EdD Benefits

Professionals looking to earn a doctorate and pursue a career in higher education administration are a perfect fit for an EdD program. An EdD is practice-based. It allows students to research their areas of interest and also leverage the results of their research to influence the decision-making process of an institution or organization.

Pursuing an EdD means a student will focus on identifying problems and developing strategies that can help clarify or even solve those problems. As such, an EdD program prepares students with skills in conducting qualitative research, collecting data, conducting interviews, making observations, and participating in focus groups.

It’s also valuable to note that for professionals interested in putting an advanced degree to work in as little time as possible, an EdD takes less time to earn than a PhD. On average, a PhD takes five to six years to complete, with some studies showing that students regularly take as many as eight years. On the other hand, earning an EdD generally takes between three and four years.

EdD Curriculum and Instruction

EdD students usually take courses covering a wide range of topics designed to prepare them for a career in higher education administration. They’ll learn about the workings of the academic community, including the student experience and the competitive nature of academia. They’ll learn about gathering and analyzing data and implementing strategic change in an institution.

Because graduates will be pursuing administrative careers, a course in leadership in higher education is required. This course will provide a general overview of many aspects of leadership roles, including theories, the concept of a multiple frames approach, strategic planning, and different decision-making processes and models.

EdD graduates enter a field in constant evolution. Future academic leaders must be prepared to understand, manage, and implement new ideas to evolve with the industry. Therefore, students will take a course in strategic change and innovation as part of their requirements. This course focuses on change models, barriers and resistance to change, and innovation and how that looks for the future of higher education.

EdD Careers

An EdD degree helps to prepare graduates for a range of professions in the higher learning sphere. EdD graduates learn leadership and decision-making competencies. These skills, coupled with their research and doctoral study experience, make them ideal candidates for college administration positions, such as chief academic officer (CAO) and academic dean.

CAOs are responsible for providing direction to an institution’s faculty and staff, monitoring programs, and ensuring adherence to rules and regulations. They create curricula and academic programs and are often involved in creating and implementing budgets and financial plans. CAOs ensure that their institutions are creating the best-possible environment for students, faculty, and staff.

Their hefty responsibility is reflected in a generous salary. In 2017, a CAO’s average annual salary was around $138,000, according to PayScale. The U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS) predicts the profession will continue to grow steadily over the next decade.

Academic deans are responsible for managing all aspects of their respective departments, including hiring, firing, and providing budgetary oversight. Academic deans work closely with professors and other faculty members to create plans of action, execute those plans, and evaluate the results. They’re responsible for setting department and performance standards and ensuring that faculty and staff meet those standards.

According to the BLS, academic deans earned a median annual salary of $94,340 in 2018.

EdD vs. PhD in Education

An EdD is a terminal degree. It’s unique in that it’s, generally speaking, a practice-based degree rather than a research-based degree. EdD students tend to be experienced education professionals who are interested in expanding and advancing their careers in a specific direction. An EdD program is often structured to be flexible and part time to accommodate the lifestyles of already working professionals.

Professionals who plan to devote their careers mostly to research pursue the better-known PhD. The EdD better suits the needs of individuals who want to take on leadership roles in their areas of focus.

In choosing between a PhD and an EdD, it’s helpful to explore your career aims. Do you want to spend your time researching new methods and developing theoretical models focused on topics ranging from equity in education to environmental impacts on student outcomes? Or are you inclined to transform the research into solutions that can drive change in real-world academic settings and improve the lives of students?

The EdD program entails coursework that aims to prepare students with the essential knowledge to deliver practical solutions to help address some of the most critical challenges in education. Graduates can serve in leadership roles by developing the skills needed to work in higher education as teacher educators; academic advisers; or administrators, such as department deans and even college presidents.

If an EdD degree sounds as if it could be right for you, you may want to check out Maryville University’s online Doctor of Education program .

Now that you know what a doctorate in education is all about, take the next step to learn more about potential careers you can pursue with an EdD degree .

Recommended Reading

Tips on Landing the Job in Higher Education Administration

Trends in Higher Education

3 Solutions to Challenges in Higher Education

College Recruiter, “5 Career Trajectories for Graduates Who Earn Doctoral Degrees in Education”

Inside Higher Ed, “Ph.D. vs. Ed.D.”

Learn.org, Doctor of Education: Salary and Career Facts

Maryville University, Online Doctor of Education – Higher Education Leadership

PayScale, Average Chief Academic Officer Salary

Teach.com, EdD vs. PhD Degrees

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Postsecondary Education Administrators

Bring us your ambition and we’ll guide you along a personalized path to a quality education that’s designed to change your life.

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

Programs & Degrees

- Programs & Degrees Home

- Master's

- Undergraduate

- Professional Learning

- Student Voices

You are here

Doctoral programs.

The goal of the GSE PhD in Education is to prepare the next generation of leading education researchers. The cornerstone of the doctoral experience at the Stanford Graduate School of Education is the research apprenticeship that all students undertake, typically under the guidance of their academic advisor, but often with other Stanford faculty as well.

In this apprenticeship model, doctoral students are provided with a multi-year funding package that consists of opportunities each quarter to serve as teaching and research assistants for faculty members' courses and research projects. By this means, and in combination with the courses that they take part of their program, students are prepared over an approximately five-year period to excel as university teachers and education researchers.

The doctoral degree in Education at the GSE includes doctoral program requirements as well as a specialization, as listed below, overseen by a faculty committee from one of the GSE's three academic areas.

Doctoral programs by academic area

Curriculum studies and teacher education (cte).

- Elementary Education

- History/Social Science Education

- Learning Sciences and Technology Design

- Literacy, Language, and English Education

- Mathematics Education

- Science, Engineering and Technology Education

- Race, Inequality, and Language in Education

- Teacher Education

Developmental and Psychological Sciences (DAPS)

- Developmental and Psychological Sciences

Social Sciences, Humanities, and Interdisciplinary Policy Studies in Education (SHIPS)

- Anthropology of Education

- Economics of Education

- Education Data Science

- Educational Linguistics

- Educational Policy

- Higher Education

- History of Education

- International Comparative Education

- Organizational Studies

- Philosophy of Education

- Sociology of Education

Cross-Area Specializations

Learning sciences and technology design (lstd).

LSTD allows doctoral students to study learning sciences and technology design within the context of their primary program of study (DAPS, CTE, or SHIPS).

Race, Inequality, and Language in Education (RILE)

RILE trains students to become national leaders in conducting research on how race, inequality, and language intersect to make both ineffective and effective educational opportunities. RILE allows students to specialize within their program of study (DAPS, CTE, or SHIPS).

Other academic opportunities

- Concentration in Education and Jewish Studies

- Quantitative Methods Certificate Program

- PhD Minor in Education

- Stanford Doctoral Training Program in Leadership for System-wide Inclusive Education (LSIE)

- Certificate Program in Partnership Research in Education

- Public Scholarship Collaborative

“I came to Stanford to work with faculty who value learning in informal settings and who are working to understand and design for it.”

Doctoral graduates were employed within four months of graduation

of those employed worked in organizations or roles related to education

For more information about GSE admissions and to see upcoming events and appointments:

To meet the Academic Services team:

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

Improving lives through learning

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of doctorate

Examples of doctorate in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'doctorate.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

1570, in the meaning defined above

Dictionary Entries Near doctorate

Cite this entry.

“Doctorate.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/doctorate. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of doctorate, more from merriam-webster on doctorate.

Nglish: Translation of doctorate for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of doctorate for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

8 grammar terms you used to know, but forgot, homophones, homographs, and homonyms, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, popular in wordplay, 'arsy-varsy,' and other snappy reduplicatives, the words of the week - mar. 8, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

- Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) in Teacher Education

Enhance your practice while remaining actively involved in classroom instruction, supervision, or professional development.

- Academic Programs

About this Program

The Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) in Education program enhances the professional practice of its graduates who assume the role of scholar practitioners as classroom teachers, local curriculum specialists, and other professionals actively involved in classroom instruction, supervision, or professional development in the various areas of emphasis.

The Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) in Education prioritizes a practitioner focus in doctoral studies in four separate emphasis areas:

- Early Childhood Education

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education (with specializations in Social Studies Education, Mathematics Education, English Language Arts Education, or Science Education)

- Special Education

The Ed.D. program is designed to improve the practice of educators involved in classrooms, curriculum, or professional development.

- Participants take advanced courses in educational foundations, inquiry, analysis, and evaluation methods for real-world problems.

- They also delve into a chosen area of study.

- This program is typically completed in three years and requires 48 semester hours of coursework after a master's degree.

The School of Education at the University of Mississippi is a member of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED), a consortium of over 80 colleges and schools of education which have committed resources to work together to advance the understanding of the contemporary doctorate in education.

Graduates of the Ed.D. program may advance to AAAA licensure.

On this Page…

Program information, program type.

Doctorate Program

Area of Study

School of Education

Ed.D. in Education

Program Location

Early Childhood Education; Elementary Education; Secondary Education; Special Education

Required Credit Hours

Degree and admissions requirements.

Applicants to the Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) program must meet the following requirements:

- A Master’s degree in a related field area with a 3.0 GPA minimum from a regionally or nationally accredited college or university

- Full or Part-time employment in the field of education

- Official transcripts

- GRE scores (less than five years old with verbal, quantitative, and writing component sub-scores)

- 3 years teaching or relevant experience (letter from employer on letterhead)

- Hold or be eligible to hold a valid teaching license in the content or related area

- Two letters of recommendation signed by the recommender. Letters of recommendation should speak to the applicant's competency to conduct rigorous, scholarly work as well as the applicant's impact on his or her professional practice

- Why is this problem important?

- Discuss the potential underlying causes.

- Discuss the ways in which this problem aligns with your chosen area of specialization.

- Interview with doctoral admissions committee

How could the Ed.D. transform your future?

Median salary for K-12 School Principals in 2022.

Median salary for a Superintendent in 2024.

Median salary for a Postsecondary Education Administrator in 2023.

Median salary for Technical and Trade School Administrators in 2022.

We're here for you!

If you have any questions about the Ed.D. in Curriculum and Instruction, don't hesitate to reach out!

Dr. Michael Mott

Professor of Teacher Education

- [email protected]

- 662-346-6069

Want to stay up to date with the SoE?

Follow us on Instragram and never miss a thing!

View this profile on Instagram Ole Miss School of Education (@ olemissedschool ) • Instagram photos and videos

Explore Affordability

We have a variety of scholarships and financial aid options to help make college more affordable for you and your family.

Apply to the University of Mississippi

Are you ready to take the next step toward building your legacy?

- Online Degrees

- Tuition & Financial Aid

- Transferring Credit

- The Franklin Experience

Request Information

We're sorry.

There was an unexpected error with the form (your web browser was unable to retrieve some required data from our servers). This kind of error may occur if you have temporarily lost your internet connection. If you're able to verify that your internet connection is stable and the error persists, the Franklin University Help Desk is available to assist you at [email protected] , 614.947.6682 (local), or 1.866.435.7006 (toll free).

Just a moment while we process your submission.

Popular Posts

What is a Doctorate: Everything You Need to Know

Already have a master’s, and thinking about taking your education further? Unsure of what that actually means and what your next options may be?

The pinnacle of educational attainment is the doctoral degree. But…what exactly is a doctoral degree, what can you get your doctorate in, and what is involved in the process? Consider this your introduction to all things doctorate.

What Is A Doctorate Degree?

The doctorate degree is the most advanced degree you can earn, symbolizing that you have mastered a specific area of study, or field of profession.

The degree requires a significant level of research and articulation. Those who earn the degree must have researched a subject or topic thoroughly, conducted new research and analysis, and provided a new interpretation or solution into the field.

The doctorate positions the professional for top-tier consulting and education career considerations and advancement in their current profession, and gives them the edge to staying relevant. In many cases, completing the doctorate means achieving a lifelong personal goal.

Earning a doctorate is challenging and rewarding, but do you know what to really expect? Download this free guide for tips and insights to help you prepare for success.

So, what types of doctorates are available?

Two Types of Doctorate Degrees

There are two major types of doctoral degrees : the research-oriented degree, and the professional application degree (also called an applied doctorate). The difference between the two types of programs may be a bit murkier than you think.

Here’s a breakdown of the two common types of doctorate programs.

The Ph.D.: A Research-Oriented Doctorate

These degrees are commonly referred to as Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.s). Some common research-oriented doctorates include the following:

- Doctor of Arts (D.A.)

- Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.)

- Doctor of Business Management (Ph.D)

- Doctor of Education (Ed.D.)

- Doctor of Theology (Th.D.)

- Doctor of Public Health (DPH)

“Philosophy” in this sense refers to the concept of research and pursuit of knowledge, as opposed to the actual subject of philosophy. A core component of this type of degree is the dissertation process .

The Professional Doctorate: An Application-Oriented Program

The professional doctorate (also called an applied doctorate, or terminal doctorate) is a degree that focuses on the application of a subject within real-world contexts or scenarios.

Most likely, you’ll want to pursue this type of degree if your goals include career advancement, meeting the requirements for certain high-level corporate jobs, establishing teaching credibility within industry, or building a consulting business.

Some common professional doctorates include:

- Doctor of Business Administration (DBA)

- Doctor of Healthcare Administration (DHA)

- Doctor of Professional Studies – Instructional Design Leadership

- Doctor of Finance (DPH)

- Doctor of Social Work (DSW)

- Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.)

- Juris Doctor (JD)

This type of degree may or may not require a dissertation. Unlike the academia-focused research doctorate, the curriculum of the professional doctorate will encourages you to tackle real-world issues within their field, research and present a solution.

How A Doctorate Works

The path to a doctoral degree is typically comprised of four stages of coursework: a core set of research and prep classes, a set of major area emphasis courses, electives and dissertation courses.

The Research Core

In most doctoral programs, you begin the journey to your degree with a common core of classes. The research core establishes the foundational skills you will need to complete the level of work required for the degree.

This core often includes advanced writing methods, research methodology and design, applied statistics, colloquium courses, and courses in qualitative and quantitative research and analysis.

Major Focus Area

Once the research core is complete, you will typically take courses in your major emphasis of study.

For example,

- If you’re earning a DBA ( Doctor of Business Administration ), you will likely take courses in organizational behavior, organizational systems, strategic thinking and decision making, ethics and change management.

- If you’re earning a DHA ( Doctor of Healthcare Administration ), you will likely take courses in healthcare policy and regulations, healthcare economics and finance, quality improvement and process improvement, and health information governance.

- If you’re earning a Ph.D. in Human Services, you will likely take courses in advanced study in research methods for public service, social influences of behavior, ethics in decision making, and advanced communication for the human services leader.

In most doctoral programs, you will also be required to take certain electives within your field. This helps provide a rounded worldview to apply your doctorate in real-world environments.

For example, if you’re pursuing a DPS (Doctor of Professional Studies) with an emphasis in Instructional Design Leadership , you may take a course from the DHA track if you want to apply your doctorate in the public health environment.

Dissertation Requirements

Once the foundation work, major area of focus, and electives are completed, you’ll begin working on your dissertation. That can take different forms, determined by the Ph.D. or applied doctorate.

For Ph.D. students, the dissertation is typically a five-chapter dissertation. This is commonly broken into three phases. In phase 1, you’ll submit a prospectus for approval from the dissertation committee. In phase 2, you’ll finalize the first chapters of your dissertation and begins collecting data. In phase 3, you’ll complete the writing of your dissertation and orally defend it to the program leaders.

For applied doctorate students, the dissertation may look different. In these programs, you will be required to create a solution to a real world problem.

Investigate Dissertation Structures

Since your dissertation will be a crucial hurdle to defeat, it’s important you know what you’re getting yourself into from the beginning. Do some research on dissertation structures when you’re looking at prospective schools for help narrowing down your list. Ensuring the school will do everything to help you succeed with your dissertation can make all the difference when it comes down to crunch time.

At Franklin, we’ve intentionally designed a dissertation structure to help you complete your dissertation step-by-step, beginning with your enrollment in the program . We’ve also built-in faculty mentoring and guidance, and peer-to-peer support so you’re never left to “figure it out” on your own.

For example, throughout the DHA program, you’ll develop important research skills and the necessary writing prowess to publish a dissertation as a capstone project to your studies. Your dissertation will showcase your ability to identify a topic of interest within the workplace, develop a proposed solution to a problem, and test your hypotheses in the real world.

How Long Will It Take to Earn Your Doctorate?

The answer depends on the path you choose.

The degree requires anywhere from 60 to 120 semester credit hours (or, approximately 20-40 college classes). Most Ph.D.s require the full 120 hours, while most applied doctorates are closer to the lower end of that spectrum. For example, the DBA and DHA at Franklin both require only 58 hours.

On average, a Ph.D. may take up to eight years to complete . A doctorate degree typically takes four to six years to complete—however, this timing depends on the program design, the subject area you’re studying, and the institution offering the program.

Pro Tip: Some innovative institutions, such as Franklin University, have streamlined their doctorate degree programs and offer creative transfer options. The program design, which includes an embedded dissertation and a community of support, also helps students earn their doctorate in as little as three years .

Why Choose to Earn a Doctorate?

A doctoral program is a serious commitment with a serious return on investment.

If you want to teach at a higher education institution, the degree is table stakes to get in the door. If you want industry leadership, the degree can deliver substantial credibility. And, if you’re eyeing for that top-floor corner office, the degree can be a huge differentiator.

So, which one is right for you—research or applied? Check out these five truths about Applied Doctorates .

Related Articles

Franklin University 201 S Grant Ave. Columbus , OH 43215

Local: (614) 797-4700 Toll Free: (877) 341-6300 [email protected]

Copyright 2024 Franklin University

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of doctorate in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- associate's degree

- baccalaureate

- bachelor's degree

- first degree

- second degree

- summa cum laude

Related word

Doctorate | intermediate english, examples of doctorate, translations of doctorate.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

white chocolate

a sweet, cream-coloured food made from cocoa butter, sugar, and milk, that is usually sold in a block

Forget doing it or forget to do it? Avoiding common mistakes with verb patterns (2)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- Intermediate Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add doctorate to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Advertisement

The expansion of doctoral education and the changing nature and purpose of the doctorate

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2022

- Volume 84 , pages 1299–1315, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Cláudia S. Sarrico 1 , 2

8458 Accesses

26 Citations

19 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Doctorate level attainment has increased significantly in developed economies. In 2019, the average share of 25–64-year-olds with a doctorate across the OECD was around 1%. However, if current trends continue, 2.3% of today’s young adults will enter doctoral studies at some point in their life. This essay starts by describing the expansion of doctoral education. It then reflects on the causes of this growth and the consequences for the nature and purpose of the doctorate. This reflection is mostly based on published research in Higher Education in the last 50 years and the author’s work on policy analysis for the OECD on this topic. The paper finishes with a research agenda on doctoral education and the career of doctorate holders.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Increasing Importance, Growth, and Evolution of Doctoral Education

Growth and diversification of doctoral education in the united kingdom, a tale of expansion and change: major trends in doctoral training and in the doctoral population in portugal.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Doctorate level attainment has increased significantly in developed economies. In 2019, the average share of 25–64-year-olds with a doctorate across the OECD was around 1%. However, if current trends continue, it is estimated that 2.3% of today’s young adults will enter doctoral studies at some point in their life (OECD, 2019b ). This growth in doctoral level attainment has been poorly recorded and the careers of doctorate holders are not systematically tracked in most countries (graduate tracking, where it exists tends to relate to bachelor and sometimes master’s graduates, where numbers are much higher). This essay seeks to open the doorway on research into why this expansion is taking place, and what it means for all involved.

Talk about a “PhD glut” is not new. The topic was already featured in Higher Education four decades ago, in a 1982 article discussing labour market outcomes, the quality of doctoral candidates and the cost–benefit analysis of the production of more doctorate holders (Zumeta, 1982 ). Since then, concerns of an expansion in doctorate holders have not dampened growth. Demands of the knowledge economy, economic growth and innovation are frequently cited as encouraging expansion, which are bolstered by government financial incentives for universities to award doctorates and produce publications. The continued trend of expansion has fed discussion on the benefits and effects of the doctorate for the individual, organisations and society (Halse and Mowbray, 2011 ) .

The status of the doctorate today is the motivation for this reflective essay, which is grounded in the literature published in Higher Education in the last 50 years (approximately 60 articles were read on the topic in the journal for the present paper). This historical perspective is complemented by other relevant literature in the field of higher education studies (circa other 60 references were read), and the author’s participation in policy analysis regarding doctoral education, postdoctoral training and the career of doctorate holders. It analyses the reasons for the growth in doctoral level attainment and the implications of this growth. It discusses the drivers of the growth, at individual, institutional and system level. It focuses on high-level and general trends, even though we are aware of national specificities and contexts, heterogeneity in academic systems and labour markets for doctorate holders, which often mean that individual jurisdictions, and indeed some disciplines, may somewhat diverge from what is being described. The article follows from the examples of contributions to understanding the expansion of higher education from Martin Trow’s ( 1973 ) discussion of the transition from elite to mass higher education, to Simon Marginson’s ( 2016 ) reflection on high-participation systems of higher education (Cantwell et al., 2018 ).

This work focuses on the developed economies of the OECD, where doctoral education is more established. Higher education has expanded massively, but research activity (as measured by publications in indexed peer-review journals) has been, for a long time, very much concentrated in the developed economies. Of the more than 18,500 higher education institutions listed by the International Association of Universities, less than 10% of institutions had at least 50 publications indexed in Scopus, the largest bibliometric database, in the period 2007–2010. Of this small group, 82% were based in European and North-American universities, and 18% in Asia–Pacific (Sarrico & Godonoga, 2021 ), almost all based in OECD countries. The situation has changed significantly in more recent years, with de-diversification of research capacity to more countries and a growing multi-polarity of that capacity, with the notable rise of China (Marginson, 2022 ). The CWTS Leiden University Ranking 2022 includes 1318 universities from 69 countries with at least 800 Web of Science indexed publications in the period 2017–2020. Footnote 1 Nonetheless, this reflection focuses on the systems with longer established doctoral education and higher doctoral level attainment among the population.

In the conclusions, this paper offers a research agenda regarding doctoral education, postdoctoral training and the career of doctorate holders.

The expansion of doctoral education

Doctoral graduates have the highest educational attainment and are primarily trained to conduct research. Doctoral education in the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) is defined as an advanced research qualification, resulting from advanced study and original research typically offered by research-oriented universities, in both academic and professional fields, requiring the submission of work of publishable quality that is the product of original research and represents a significant contribution to knowledge in a field of study (OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO, 2015 ). Footnote 2

Statistics on doctoral level attainment presented by the World Bank data bank Footnote 3 start only in 2010. No information is available for many countries (e.g. China) and for other countries many years of data are missing (e.g. UK, Germany, France, Japan). Looking at this data set shows that in 2020 there were only 36 countries with doctoral level attainment above 0.6%, including only a few non-OECD countries (United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Malta, South Africa).

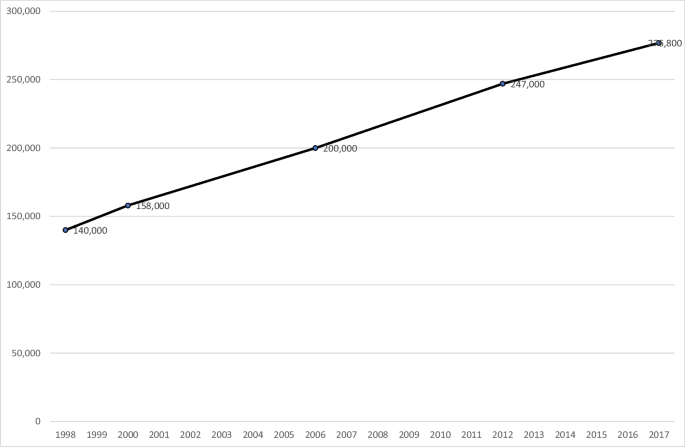

There is also no good international comparable data on the number of new doctorates being awarded in different countries. Only 5 years’ information is available for OECD countries, showing that the number of new doctorates has almost doubled in the two decades to 2017 (Fig. 1 ). Recent work underlines this growth, finding that doctoral level attainment in the OECD has increased by 25% over the 5-year period 2014–2019 (OECD, 2021a ). By comparison, research activity, a traditional occupation for doctorate holders, has grown much more slowly. Gross domestic spending on R&D, carried out by companies, research institutes, university and government laboratories grew by 18% in the last two decades (2000–2020) (OECD, 2022b ). This probably means there is not enough research activity in the economy to provide research occupations for many of the doctorate graduates being produced.

New doctorates awarded, OECD countries. Source: Auriol ( 2010 ), Auriol et al. ( 2013 ), OECD ( 2014 ), OECD ( 2019b )

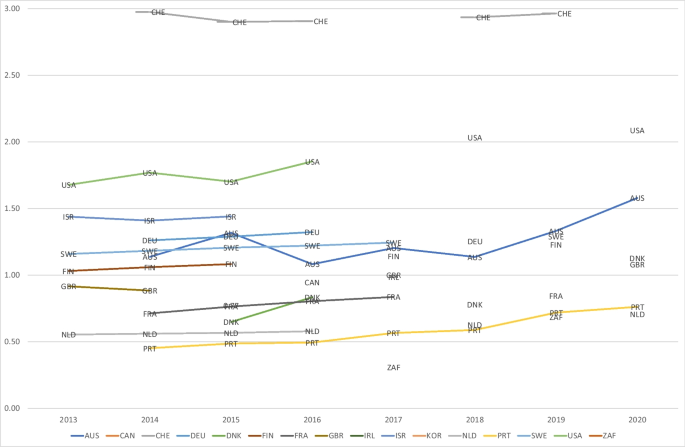

The recent growth in doctorate level attainment in the OECD is well above that of tertiary education attainment: between 2014 and 2019, doctoral education grew 25% (0.93–1.16%), while tertiary education grew 12.7% (33.65–37.90%) (OECD, 2022a ). Data for countries outside the OECD is difficult to obtain, and even for the OECD there are many gaps (e.g. Japan). For instance, World Bank statistics on doctorates start in 2010 and omit many countries and many years (Fig. 2 ).

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (uis.unesco.org). Data as of June 2022. The percentage of population ages 25 and over that attained or completed doctoral or equivalent education. https://databank.worldbank.org/ (accessed 6 July 2022). Note: AUS, Australia; CAN, Canada; CHE, Switzerland; DEU, Germany; DNK, Denmark; FRA, France; GBR, United Kingdom; IRL, Ireland; KOR, Korea; NLD, Netherlands; PRT, Portugal; SWE, Sweden; USA, United States; ZAF, South Africa

Doctoral level attainment, selected countries.

According to the US National Science Foundation, between 2000 and 2018, the number of science and engineering doctoral degrees awarded grew on average by 9.9% per year in China, 2.0% in France, 1.4% in Germany, 5.2% in Korea, 7.1% in Spain, 5.0% in the UK and 2.8% in the USA (NSB-NSF 2022, Fig. 5, p. 8).

The doctorate is no longer an entry ticket to academia

The expansion of doctoral education seems likely to continue as governments increase funding for doctoral education in an attempt to boost competitiveness and talent pools in an internationally competitive environment. However, there are attempts to diversify away from traditional “academic doctorates” with “collaborative PhDs”, “professional doctorates”, “industrial doctorates”, or simply introducing professional development and career development opportunities. In addition, the scope of doctoral education is widening, seeking to prepare people for diverse careers and include doctorates that cross disciplinary boundaries (Powell and Green, 2007 , p. 238).

Academia can no longer employ increasing numbers of doctorate holders (OECD, 2021b ). It is unclear to what extent the labour market, especially beyond academia, is absorbing recent doctoral graduates, and how well doctoral education and postdoctoral training adequately prepare people for jobs outside academia. The debate about an “oversupply of PhDs” has reached mainstream media (The Economist, 2010 ).

New graduates surpass demand for academics at universities. A grim picture emerges of early-career academics as “cheap labour” in a “feudal system”, resting on the principles of “up or out” and “survival of the fittest” (OECD, 2021b ). Using doctoral and postdoctoral researchers to teach undergraduates also reduces the number of full-time permanent positions. Even countries with less developed higher education systems seem to have plateaued in their capacity to absorb new doctorates into permanent positions (e.g. South Africa in Mouton et al., 2021 , pp. xxiv-xxvi).

The postdoc, here defined as a fixed-term position in academia after the doctorate with no guarantee of continuation, has been the norm in many systems where permanent positions have been extremely limited (e.g. Germany and Switzerland). In other systems, entering a tenure-track with some prospect of continuation was the initial step in the academic ladder, but this has been changing over time (e.g. USA). Nonetheless, postdocs now perform a large part of university research work in many OECD academic systems, and, in some areas, the postdoc has become a de facto prerequisite to be considered for a permanent full-time job. Doctoral and postdoctoral researchers boost the research capacity of their universities and countries, but when they cannot find a job in academia, they may have difficulty transitioning to jobs outside the academic career. In some areas, the financial return on a PhD is now negative or not much different from a master’s degree, which can be attained in a fraction of the time. When controlling for self-selection into doctoral education and labour market choices after graduation, the wage premium reduces (Pedersen, 2016 ). Master’s holders accrue work experience while the doctoral researchers are pursuing their studies, increasing their relative value in the labour market. Doctorate holders may then occupy positions that only require a master’s, due to oversupply relative to the needs of the labour market, resulting in over skilling. Questions are then raised about the continuing investment in more doctoral education.

However, we know little of the career paths of doctorate holders, when and how they transition from academia to employment, and how useful their doctoral education is to their career and their life. Some may find their training so specialised that they find it difficult to find suitable work outside academia and linger there on fixed-term contracts. Some may pursue a doctorate simply for education’s sake, and enjoy the lifestyle, but in the long run they may become less satisfied, less productive and more likely to have to move to jobs beyond academia for which they had not planned.

There is a belief that there are spill over effects from knowledge being produced in universities. Nonetheless, for the individual it may not work well. People embarking on PhDs are likely to have been the best in their class, raising the question of whether a PhD is always the best use their talent. It may also be the case that the best are no longer attracted by the idea of doing a PhD, as they realise the precarity involved.

The incentives for universities and principal investigators (PIs) are not aligned with the interests of doctoral and postdoctoral researchers, who support the research endeavour and are key to keeping it going. And many governments offer funding incentives and rewards linked to performance, where the number of PhD graduates is part of the formula.

In most OECD countries, the majority of doctorate holders already work outside academia (OECD, 2015 ), and many countries have moved to a more structured environment of doctoral programmes and doctoral schools where they can offer training in skills that can be transferred to the labour market beyond academia, smoothing the transition.

The expansion of doctoral education was accompanied by changes in its nature, from an apprenticeship-type period under the supervision of a “master” to a highly structured education programme in most countries, with doctoral schools, formal processes, and a defined duration and expectations. Paradoxically, it has been accompanied by an increasingly unstructured phase of postdoctoral studies in the academic professional ladder—postdoctoral researchers are in a limbo: neither staff nor students (OECD, 2021b ), and in some fields preceded by a pre-doctoral programme of 1 to 2 years prior to entry into the doctoral programme itself. The postdoctorate position now seems to be the “apprenticeship” stage under the supervision of a senior academic, and sits between completion of the doctorate and a permanent position. A postdoctoral position was meant to be transitional and a “defined period of advanced training and mentoring in research” (National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine, 2014 ); instead, it became a safety net for those waiting for an academic position that is more likely than not to fail to materialise (Larson et al. ( 2013 ), Milojević et al. ( 2018 )). Institutions tend to rest their research prowess on a few tenured star researchers that head teams populated by postdoctoral and doctoral researchers (and predoctoral researchers) that feed the research endeavour. They now depend on the “permadocs” and the labour of an academic precariat to sustain it (Teixeira, 2017 ). Although many are on fixed-term contracts, they are a significant share of the research labour force, their papers obtain more citations, and they tend to publish in more prestigious journals than those on indefinite contracts (OECD, 2021b ).

This means that doctoral education and postdoctoral training is no longer necessarily a path to the professoriate. Most doctorate holders will end up working beyond academia, in business, government or the social sector—some in research occupations, although many will not. The vast majority of researchers with a doctorate in the OECD work in the higher education and the government sectors. Since in many countries, most doctorate holders work outside the academic sector, this indicates that many employed doctorate holders are not doing research. Footnote 4

The lack of positions in the academic career proper has not stopped the expansion, and many countries continue to provide incentives to universities to produce doctoral graduates and individuals to pursue doctoral studies. Under the EC-OECD STIP Compass, Footnote 5 countries mostly cite funding levers as the mechanism to increase doctoral and postdoctoral participation.

This is accompanied by a discourse that society and the economy need the advanced skills of these individuals to sustain a knowledge economy and spur innovation, and that the doctorate ought to prepare individuals for diverse careers. Employment rates of doctorate holders are systematically higher than among other tertiary level graduates in the working age population (OECD, 2015 ), but for young doctorate holders, those aged 25–34, their comparative advantage over their peers with a master’s degree tends to be more variable (OECD, 2019b ).

In addition, many doctorate graduates are not particularly young—the median age at entry is 29 on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2019b ). After a prolonged postdoctoral period in academia, many transition to employment beyond academia well into their forties, which has implications for how easy the transition will be.

The supply side strategies from governments to promote the production of doctorate holders are often not in line with demand from employment sectors beyond academia, and with the experiences of doctorate holders. Many doctorate holders that transition to employment beyond academia will not work as researchers. From a macro level, this raises the issue of inefficiency: the advanced skills of doctorate holders are not necessarily used, notably in non-research occupations (Stephan, 2012 ). It compounds the inefficiency already observed in many countries during doctoral studies, where entry rates are well above graduation rates.

For the individual, while many doctorate holders will find successful and satisfying alternative careers, they often report challenges in making the transition associated with giving up long-held ambitions of an academic career and a loss of social identity (Vitae, 2016 ). Career choices beyond academic research are mostly seen as second options, or as a signal of failure by postdoctoral researchers and their PIs and are often made quite late into the professional career of doctorate holders. Those that do transition may experience organisational culture shock, especially those who enter jobs beyond academia directly after the PhD with little or no prior work experience (Skakni et al., 2022 ).

Reasons for the growth of doctoral education

There are several explanations for the growth in doctoral education. Supply side factors relate to factors that encourage the supply of more doctorate graduates, such as policies to fund doctoral education, and reward institutions for increased production of doctorates and publications. Demand side factors increase the demand for doctorates and represent the attractiveness of doctoral education to the individual, such as the perceived career prospects, social gain or self-realisation, and to the organisations employing doctorate holders because they value their expertise and skills. Another driver is the international import of talent in a global race for competitiveness among economies.

Government policy

Governments, especially in developed economies, have embraced economic theories of the knowledge economy, targeting knowledge as fundamental to economic growth and prosperity. They have promoted postgraduate study, doctoral education and postdoctoral training to foment the development of advanced skills, knowledge generation, complex problem solving and, more generally, innovation. Research funders increasingly try to assess and incentivise the research impact of the research they fund, in terms of scientific impact, but also economic, social, cultural and environmental impact.

Funders have realised that the increased number of doctorates means they no longer will find a position in academia. Hence, policies now encourage doctoral and postdoctoral researchers to engage in some form with organisations beyond academia to encourage the next generation of researchers to explore diverse careers in other sectors (OECD, 2021b ). There is evidence, however that most continue to prefer an academic career, an attraction that often increases as students advance in their programme, even when it involves industrial contacts (Gemme & Gingras, 2012 ).

An unintended consequence of increasing the supply of research funding may be to support the aspiration to an academic career, albeit a precarious one, given the fixed-term, project-based nature of most research funding, including for those with less scientific capital and less job prospects elsewhere.

Changes in academic work

In addition to an increase supply of research funding, the nature of that funding has also changed. There is an increasing share of project-based funding relative to core basic funding, and the development of earned income streams, in addition to public appropriations and student fees, from continuing education, service provision, contract research, philanthropy and endowments. This changed academic work (Cantwell, 2011 ; Cantwell & Taylor, 2015 ), with increasing use of non-standard employment contracts and specialisation of work in both teaching and research. It gave rise to contingent instructors and postdoctoral researchers mostly dependent on fixed-term funding, to the detriment of combined teaching and research positions in the academic career proper. The expansion of doctoral education ensures a constant supply for these positions.

Demand for doctoral researchers

Even if an academic career has not become more attractive per se, given the general expansion of higher education at bachelor and master’s levels, the number of potential doctoral candidates has substantially increased. Most students pursuing a doctoral degree have a “taste for science” and are strongly attracted to an academic career, but not all (Roach & Sauermann, 2010 ). Curiously even those that had considered an alternative career often change their minds as their studies progress (Gemme and Gingras, 2012 ).

In some cases, doctoral education is also valued beyond academia. Employers of doctorate holders seem to value the technical competence of those from the hard sciences and the transferable competences from the soft sciences (Passaretta et al., 2019 ). Unemployment is generally lower for doctorate holders compared with other higher education graduates (Auriol et al., 2013 ). However, we do not know how much of this is the consequence of their doctoral education, and how much is related to their intrinsic ability to learn and work.

We know little about the companies that employ doctorate holders, but some evidence suggests that cooperation between universities and the world of business fosters the recruitment of doctorate holders, and that the effect is cumulative (Garcia-Quevedo et al., 2012 ). This suggests that fostering mobility of people and cooperation in research activities between universities and business will increase the demand for doctorate holders. However, the willingness to recruit PhDs is related to the degree of development of the economy, and especially to the R&D and technology intensity of businesses. This also explains the brain drain from less to more developed countries, as people move from less to more knowledge intensive economies.

Credentialism

Arguably, some individuals may be also searching for differentiation in a crowded graduate market in high-participation systems of higher education (Zusman, 2017 ). This form of credentialism is probably at play is some professional disciplines, such as business, public administration and health, where mid-career professionals may be using the doctorate to improve their professional status, autonomy and income rather than to respond to labour market needs or increased complexity of their jobs. Indeed, it may be also occurring in the higher education sector among other professional staff supporting students or involved in the management and administration of institutions, and operating in hybrid roles between academia and other professions. Some of these new doctorates are not compliant with existing definitions, such as the ISCED classification mentioned above, and may not be recognised as such by some organisations (see footnote 2 of this article and footnote 3 of Zusman, 2017 , regarding recognition by the National Science Foundation in the USA).

Import of international talent

On average across OECD countries, 22% of enrolled doctoral students are international or foreign students, compared to 13% at master’s level and 4% at bachelor’s (OECD, 2019b ). Doctorate holders are highly mobile and the labour market for them is globalised (Auriol, 2010 ), although mobility varies by discipline. Many countries deliver their doctorates (and increasingly their master’s) in English, although concerns about the role of minority languages are being raised in some countries, such as the Netherlands, Finland and Denmark (Powell and Green, 2007 , p. 240).

There are also issues of brain drain from poorer to richer countries, and many early-career researchers must be prepared to move to enter the academic profession. Some countries, such as the USA, rely on importing talent to feed their academic system. Migrating academics seek out better conditions in terms of salaries, quality of life, career perspectives, research organisation, balance between teaching and research, funding, and being among high-quality peers (Janger et al., 2019 ). The best, “star performers” seek the most reputable and prestigious institutions, others move to simply look for an occupation they cannot find in their home countries (Cattaneo et al., 2019 ).

Some early career researchers are indeed encouraged to have international mobility as a requisite or to improve their chances for a job in their home country (Musselin, 2004 ), although if the return is not timely reintegration can be difficult because of a loss of social capital in their home country (Cañibano et al., 2020 ).

Less developed countries like India and especially China are transitioning from being exporters of students to becoming competitors of European, North American and Australian higher education systems. It is also important to note that new doctorate holders are needed to improve the qualifications of academic staff in many systems in the developing world, where the production of doctorates has not been able to keep pace with the enrolment expansion of recent decades (Altbach et al, 2012 , p. 18).

Consequences of the growth of doctoral education

The permadoc phenomenon.

Postdoctoral training has benefits: it fosters research productivity and integration in the international scholarly community (Horta, 2009 ), while positively contributing to the possibility of working in a higher education institution and securing a tenure-track appointment. However, while taking one postdoctoral position does increase research productivity, there is little or no advantage from taking two or more (Yang and Webber, 2015 ).

Slower progression within academic careers has become more common in younger cohorts of academics, characterised by a long pre-tenure phase, with many still occupying postdoctoral positions in their forties. In some cases, this long path is even experienced by those that are recruited as assistant professors, where they may remain for most of their careers (Benz et al., 2021 ). Paradoxically, in many countries mobility from the business sector to the higher education sector is higher than the other way around (Auriol et al., 2013 ).

The emergence of the academic precariat

The early stages of the academic career are characterised by insecurity and have been so for some time now (Rosenblum & Rosenblum, 1996 ). Those outside of the career proper, on fixed-term contracts, have provided most of the instruction, and most of the research, in many systems, with no guarantee of continuing employment. The difference is that younger cohorts of academics are now faring less well in transitioning from the external to the internal labour market. Those that manage to make the transition need to be geographically mobile, self-confident and devote a high proportion of their time and effort to research and networking (Ortlieb & Weiss, 2018 ). However, not all institutions assist early-career academics with contacting colleagues abroad, provide financial support for conferences and stays abroad, and provide support with family commitments for them to be able to succeed.

Precarity also raises issues of equity, diversity and inclusion. It has been found that academics who come from the upper social class have access to higher-quality undergraduate education, subsequently progress to more prestigious research universities for doctoral education, and later report higher earnings (Chiappa & Perez Mejias, 2019 ). In addition, they can better afford the precarity associated with academia, especially in its early stages (OECD, 2021b ).

In doctoral education, as in academic employment, women are now on a parity in most fields. At the same time, women are less represented in fields that may offer more opportunities outside academia, such as engineering, manufacturing and construction, are less internationally mobile, and more often work part-time, which may hinder their prospects for advancement in the academic career. Women are also under-represented in tenure track positions, particularly when recruitment is based on invitation. All these factors may explain why women and minority groups tend to be more vulnerable to precarity (OECD, 2021b ).

To find a position, postdoctoral researchers often need to be prepared to move within and increasingly beyond their countries. This may be beneficial for the scientific endeavour, as less mobile academics have more inward oriented information exchange dynamics and lower scientific productivity (Horta, 2013 ), but it often signifies a personal toll. It often means losing the social networks necessary to access positions back home, and conditions for international researchers are often worse, in relation to access to employment contracts, right to stay and welfare benefits. It may also mean having to postpone family formation.

Academia may no longer be attractive to the most talented

The poor career prospects of academia do not cause a shortage of academic researchers, but may push the most talented to jobs beyond academia (Waaijer, 2017 ). Doctorate holders working in research are particularly satisfied with the intellectual challenges of the job (Auriol et al., 2013 ). However, younger doctorate holders in higher education are about 2.5 times less likely to be employed on a permanent basis than those working in other sectors (OECD, 2019a , p. 186). While temporary positions are increasingly common in academia, coinciding with the rise of postdoctoral positions, they are less so in business. Earnings also tend to be higher in the business sector, although there are exceptions in some disciplines (Auriol et al., 2013 ). Natural scientists and engineers are more likely to find employment in research outside academia, while social scientists find more opportunities in non-research occupations. Still, even when not in research, jobs are in most cases related to the subject of doctoral degrees and doctoral graduates tend to be satisfied with their employment situation (Auriol et al., 2013 ).

If academia is to attract and retain the best talent, funding agencies need to have dedicated provision for early career researchers, who otherwise leave for more stable and promising careers beyond academia (Bazeley, 2003 ). And should countries continue to produce more doctorate holders than academia can possibly absorb, then it is important to broaden the job skills that doctoral students acquire during their training to better prepare them for the needs of a wider job market (Cattaneo et al., 2019 ).

Questions about the quality of doctoral education

Despite the growth in doctoral level attainment, the truth is that many doctoral candidates do not complete their degrees: looking at the OECD entry rate for those under 30 and the graduation rates for those under 35, an estimated 1 in 3 drop out. Footnote 6 There are many reasons for withdrawal, including the personal situation of the candidate, but institutional factors are paramount. Institutional issues revolve around the difficulty in achieving work-life balance, and problems with socialisation, often due to a “culture of institutional neglect” (Castelló et al., 2017 ; McAlpine et al., 2012 ), as well as contact with the supervisor and exchange with other PhDs (Jaksztat et al., 2021 ). In addition, admission standards of doctoral programmes may not necessarily pursue high-quality doctoral students (Cattaneo et al., 2019 ) .

The increase in doctorate level attainment does not necessarily mean that all attain what is planned in the definition of International Standard Classification of Education for doctoral level attainment (OECD/Eurostat/UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2015 ) or the Dublin Descriptors (EHEA, 2005 ). The current level of doctoral education attainment in the population, at 1.0%, may not be matched by the level of advanced skills in the population. Less than 0.5% of the adult population in the OECD reaches the highest levels of literacy, i.e. 5 in a scale of 1 to 5, where 3 is considered the necessary level to operate in today’s society and assumed to be provided by upper secondary education (OECD, 2019c ). Level 5 description of proficiency Footnote 7 is arguably the closest to the description of outcomes achieved in doctoral level education in the Dublin Descriptors. Footnote 8

Often, doctorate holders that find themselves in employment outside academia experience an over-development of research skills relative to what is required of the job, but an under-development in personal effectiveness, management and communication skills (Waaijer et al., 2017 ), which means they may be both over- and under-qualified. These findings call for doctoral education to include not only the development of research skills but also skills in other areas relevant to the labour market. However, the premise that education should provide all the skills that the labour market requires is not universally supported. Employers are also responsible for training and developing the employees they recruit, and that responsibility should not be fully transferred from employers to the employee or education institutions (Cappelli, 2015 ).

The changing nature of doctoral education

As it has grown doctoral education has become more formalised, supervisory practice more regulated and the curriculum more explicitly structured. On the other hand, growth has also brought diversity of approaches to doctoral education, in response to evolving disciplinary practices, interactions with outside organisations and the career expectations of doctoral researchers (Pearson et al., 2008 ).

Following the crisis discourse that universities are producing too many doctorates for the few academic jobs available, the concerns with the efficiency of doctoral programmes have shifted to preoccupation with the lack of skills of doctorate holders for productive jobs beyond academia (Cuthbert & Molla, 2015 ; Kniola et al., 2012 ). This discourse presents the inevitable tension between outcomes of research prowess and the relevance of doctorates to the needs of society.