Inclusive Education in a Post-Soviet Context pp 67–97 Cite as

Differentiated Instruction, Perceptions and Practices

- Ainur Aliyeva 3

- First Online: 27 February 2021

279 Accesses

In a time of shifting paradigms from teacher-centered approaches toward more student-centered approaches, differentiated instruction has become one of the leading pedagogical strategies to address individual learning needs

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Irvine, C. K. S., & Walker, D. (2013). Introduction to research in education . Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Google Scholar

Baker, L. (2006). Observation: A complex research method. Library Trends, 55 (1), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0045 .

Article Google Scholar

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9 (2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027 .

Bray, B., & McClaskey, K. (2013). A step-by-step guide to personalize learning. Learning & Leading with Technology, 40 (7), 12–19.

Corley, M. A. (2005). Differentiated instruction: Adjusting to the needs of all learners. Focus on basics. Connecting Research and Practice, 7 (C), 13–15. Retrieved from http://www.ncsall.net/?id=736 .

Coubergs, C., Struyven, K., Vanthournout, G., & Engels, N. (2017). Measuring teachers’ perceptions about differentiated instruction: The DI-Quest instrument and model. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.02.004 .

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Cronin, C. (2014). Using case study research as a rigorous form of inquiry. Nurse Researcher, 21 (5), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr.21.5.19.e1240 .

De Neve, D., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.003 .

Flem, A., Moen, T., & Gudmundsdottir, S. (2004). Towards inclusive schools: A study of inclusive education in practice. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 19 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10885625032000167160 .

Fullan, M. (2007). Leading in a culture of change . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Hale, J. B., Chen, S. A., Tan, S. C., Poon, K., Fitzer, K. R., & Boyd, L. A. (2016). Reconciling individual differences with collective needs: The juxtaposition of sociopolitical and neuroscience perspectives on remediation and compensation of student skill deficits. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 5 (2), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2016.04.001 .

Harris, A., Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., & Hopkins, D. (2007). Distributed leadership and organizational change: Reviewing the evidence. Journal of Educational Change, 8 (4), 337–347.

Huebner, T. A. (2010). What research says about… / differentiated learning , reimagining school (pp. 83–84). Alexandria, Virginia US: ASCD.

Kazakhstan. (2007). Law on Education . (2007). Retrieved from https://online.zakon.kz/document/?doc_id=30118747#pos=120;-69 .

Lambert, L. (2003). Leadership redefined: An evocative context for teacher leadership. School Leadership & Management, 23 (4), 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/1363243032000150953 .

Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. New York and London: The Guilford Press.

Mac Ruairc, G., Ottesen, E., & Precey, R. (2013). Leadership for inclusive education . Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publishers.

Book Google Scholar

Makoelle, T. M. (2016). Inclusive teaching in South Africa . Cape Town: Sun Media Publishers.

Makoelle, T. M. (2020). Schools’ transition toward inclusive education in Post-Soviet countries: Selected cases in Kazakhstan, Sage Open , 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020926586 .

McTighe, J., & Brown, J. L. (2005). Differentiated instruction and educational standards: Is etente possible? Theory into Practice, 44 (3), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4403_8 .

Meyer, O. (2010). Introducing the CLIL-pyramid: Key strategies and principles for quality CLIL planning and teaching. Basic Issues in EFL—Teaching and Learning , 11–29.

Mills, M., Monk, S., Keddie, A., Renshaw, P., Christie, P., Geelan, D., et al. (2014). Differentiated learning: From policy to classroom. Oxford Review of Education, 40 (3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.911725 .

Nicolae, M. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs as the differentiated instruction starting point: Research basis. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 128 , 426–431. / https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.182 .

Norwich, B. (1994). Differentiation: From the perspective of resolving tensions between basic social values and assumptions about individual differences. Curriculum Studies, 2 (3), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965975940020302 .

Precey, R. (2011). Inclusive leadership for inclusive education—The Utopia worth working towards. Contemporary Management Quarterly/Wspólczesne Zarzadzanie , 2 .

Raskala, J. (2014). Differentiation in CLIL: Methods and challenges. Bachelor dissertation University of Jyvaskyla. Retrieved 30 January 2017, from http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:jyu-201504221648 .

Reeves, D. B. (2009). Leading change in your school: How to conquer myths, build commitment, and get results . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Roiha, A. S. (2014). Teachers’ views on differentiation in content and language integrated learning (CLIL): Perceptions, practices and challenges. Language and Education, 28 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2012.748061 .

Santamaría, L. J. (2014). Critical change for the greater good: Multicultural perceptions in educational leadership toward social justice and equity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50 (3), 347–391.

Shields, C. M. (2010). Transformative leadership: Working for equity in diverse contexts. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46 (4), 558–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X10375609 .

Smit, R., & Humpert, W. (2012). Differentiated instruction in small schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28 (8), 1152–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.07.003 .

Stanford, B., & Reeves, S. (2009). Making it happen: Using differentiated instruction, retrofit framework and universal design for learning. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus 5 (6), 3–7. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967757.pdf .

Subban, P. (2006). Differentiated instruction: A research basis. International Education Journal, 7 (7), 935–947. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854351.pdf .

Suprayogi, M. N., Valcke, M., & Godwin, R. (2017). Teachers and their implementation of differentiated instruction in the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.020 .

Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Reconcilable differences? Standards-based Teaching and Differentiation, 58 (1), 6–11.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2016). Why differentiation is difficult: Reflections from years in the trenches. Australian Educational Leader, 38 (3), 6.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom . Alexandria, Virginia US: ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., & McTighe, J. (2006). Integrating differentiated instruction and understanding by design: Connecting content and kids . Alexandria, US: ASCD.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). What is backward design? Understanding by design (pp. 13–34). Alexandria, Virginia US: ASCD.

Zainal, Z. (2007). Case study as a research method. Jurnal Kemanusiaan , (9), 1–6. Retrieved from http://psyking.net/htmlobj-3837/case_study_as_a_research_method.pdf .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan

Ainur Aliyeva

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ainur Aliyeva .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Graduate School of Education, Nazarbayev University, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan

Tsediso Michael Makoelle

Michelle Somerton

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Aliyeva, A. (2021). Differentiated Instruction, Perceptions and Practices. In: Makoelle, T.M., Somerton, M. (eds) Inclusive Education in a Post-Soviet Context. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65543-3_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65543-3_4

Published : 27 February 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-65542-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-65543-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, di (differentiated instruction) does matter the effects of di on secondary school students’ well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept.

- 1 Professional School of Education, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2 School of Psychology, University of Monterrey, Monterrey, Mexico

- 3 Section for Teacher Education and Research, University of Trier, Trier, Germany

- 4 Center for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 5 Research Focus Area Optentia, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

In consideration of the substantial increase in students’ learning demands, teachers are urged to address student heterogeneity in their daily teaching practice by means of differentiated instruction (DI). The practice of DI, as a vehicle to achieve inclusive education, not only aims to support all students’ academic learning but also foster their social and emotional development. However, current research in the field of DI has mostly been limited to an examination of its effects on students’ achievement outcomes. Consequently, the potential impact of DI on students’ socio-emotional outcomes has, till now, received very little attention. In order to address this gap in the research, the current researchers seek to investigate the effects of DI on school students’ well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept. Survey participants in this study included 379 students from 23 inclusive and regular classes in secondary schools in Austria. Following multilevel analyses, the results have indicated that students’ rating of their teachers’ DI practice is positively associated with their school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept. However, a t -test for dependent samples demonstrated that students perceive their teachers’ DI practice to be infrequent. Implications of the results along with further lines of research are also presented in this paper.

Introduction

From the perspective of pedagogical professionalism, teachers are responsible for providing students with equal access to learning situations and enabling them to participate in academic as well as socio-emotional interactions. As teachers have a significant role to play in the creation of educational contexts, the requested access and participation of every student greatly depends on the implementation of teaching practices and strategies and the accompanying educational offers ( Decristan et al., 2017 ; Pit-ten Cate et al., 2018 ). Given the fact that a heterogeneous class composition forms the pedagogical work base for teaching and learning processes, teachers are inevitably confronted with the professional demand to implement adequately adapted teaching practices that are tailored to their students’ needs ( Vaughn et al., 2007b ; Pozas et al., 2020 ; Kärner et al., 2021 ). Diverse student characteristics as well as their various educational needs necessitate suitable pedagogical reactions which are free of discrimination and exclusion and guarantee learning for every student ( McMurray and Thompson, 2016 ; Petersen, 2016 ; Ainscow and Messiou, 2018 ). In this context, inclusive teaching practices are often discussed as a pedagogical solution to avoid learning barriers for students who are likely to be disadvantaged in educational settings [e.g., due to individual characteristics such as a diagnosis of having special education needs (SEN)] ( Lindner and Schwab, 2020 ; Schwab et al., 2020 ; UNESCO, 2020 ).

DI to Students’ Diversity

Given the highly heterogeneous study population (Dijkstra et al., 2016; Maulana et al., 2020 ; Watkins, 2017), the concept of inclusion has been shifted from the inclusion of students with SEN to the participation to all students ( European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education, 2017 ; Schwab 2020 ). As a result, policymakers urge teachers to make use of inclusive teaching strategies to provide valuable learning for all students within a learning group ( UNESCO, 2020 ). One inclusive approach that is often discussed as a possible strategy to react adequately to students’ diversity is DI ( Tomlinson, 2014 ; Bondie et al., 2019 ). DI is considered to be an inclusive instructional practice that can be defined as the intentional, systematically planned and reflected practices that enable teachers to meet the needs of all learners in heterogeneous classrooms (Graham et al., 2020; Pozas and Letzel, 2020 ).

In order to differentiate their instruction, teachers must consider students’ individual characteristics and educational needs by regarding five fundamental dimensions: 1) coping with student diversity; 2) adopting specific teaching strategy; 3) introducing a variety in learning activity; 4) monitoring individual student needs; and 5) pursuing optimal learning outcomes ( Suprayogi and Valcke, 2016 ). Thus, the heterogeneity of class composition is a pivotal basic assumption with regard to teachers’ creation of teaching and learning situations. Based on the acknowledged diversity of the students in a class, specific teaching practices must be chosen in order to include multifaceted activities that promote learning for every student. For instance, teachers can implement DI through a variety of instruction behaviours such as tiered assignments, homogeneous or heterogeneous subgroups based on learners’ performance or interests, tutoring systems, open education practices, and variants of mastery learning strategies (Coubergs et al., 2017; Darnon et al., 2012; Hachfeld and Lazarides, 2020; Lawrence-Brown, 2004; Maulana et al., 2020 ; Tomlinson, 2014 ). Overall, the goal of teachers’ implementation of DI is the achievement of students’ optimal learning outcomes ( Suprayogi and Valcke, 2016 ).

Effects of DI on Student Outcomes

Given that DI can be often described as a collection of instructional strategies which enable teachers to ensure that all students, regardless of their individual characteristics, have positive and successful learning situations, its effectiveness is often associated with optimal learning outcomes at the level of academic performance and achievement ( Loreman, 2017 ). However, up to know there are still diverging definitions of the instructional approach make it a challenge to compare results from different studies on the effects of DI, thereby leading to investigations of different outlines of DI (Jennek et al., 2019; Lindner and Schwab, 2020 ; Prast et al., 2015 ; Roy et al., 2015 ). Taking this into account, Deunk et al. (2018) undertook a meta-analysis to investigate the effects of DI on the cognitive competences of primary students. Overall, the examination of 21 studies showed a small positive effect of DI on students’ academic achievement ( Deunk et al., 2018 ). Nevertheless, when DI was operationalized solely through grouping strategies, no significant overall effect was found. The results of a meta-meta-analysis of Steenbergen-Hu et al. (2016) showed no significant effects of DI in the context of grouping practices on students’ performance. The results of Nusser and Gehrer (2020) drew a similar picture. Within the context of a longitudinal study, a positive development of secondary students’ German competence was investigated, but it could not be explained as an effect of teachers’ use of DI on reading competence development ( Nusser and Gehrer, 2020 ).

By investigating DI in the sense of an overall inclusive school culture, the results of ( Goddard et al., 2015) showed that DI-related school norms and teaching practices had significantly positive effects on students’ academic achievement in mathematics and reading ( Goddard et al., 2015 ). In a study of ( Valiandes, 2015) , teachers’ implementation of DI was investigated by conducting observations, in the course of which the intensity of the use of DI was rated. The results showed a positive effect of differentiated teaching approaches on students’ academic progress ( Valiandes, 2015 ). However, it is noticeable in the context of studies investigating the effectiveness of DI that the predominant focus is placed on its effect on students’ academic achievement rather than non-academic student outcomes ( Smit and Humpert, 2012 ; Little et al., 2014 ; Steenbergen-Hu et al., 2016 ; Deunk et al., 2018 ; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019 ).

In addition to exploring the effects of inclusion on students’ achievement outcomes, supporting every students’ emotional and social development can also be considered as key objectives of inclusive education. Students’ socio-emotional development has been considered an important issue within policy debate ( Zurbriggen et al., 2018 ), and thus seems important to explore the potential effect that DI can have on students’ non-achievement outcomes ( Pozas and Schneider, 2019 ). In this context, three important student outcome variables that have been extensively explored in research and literature are students’ well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept ( Venetz et al., 2015 ; DeVries et al., 2018 ; Venetz et al., 2019 ). These three student outcome variables have been long investigated because of their relation to students’ academic learning and performance as well as their general satisfaction and development (Gilman et al., 2014; Schwab et al., 2020 ). Additionally, assessing students’ subjective well-being, social inclusion, and academic self-concept are variables that can reflect educational quality (Guillemot and Hessels, 2021). The results of a quantitative study by Alnahdi et al. (2021) indicate that students’ perception of their teachers’ use of DI strongly predicted students’ perceived emotional and social inclusion as well as their academic self-concept. Such results highlight the relation between the implementation of DI and students’ non-academic outcomes ( Alnahdi et al., 2021 ). Roy et al. (2015) showed that teachers’ implementation of DI buffered the negative Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect (BFLPE) (i.e., the idea that high-achieving students feel motivated by their advantage over their lower-achieving peers, which can negatively affect low-achieving students’ academic self-concept). As a possible explanation, the authors assume that DI can function as a motivator for all students, as the educational offers are prepared in a way that every student can be involved in learning situations rather than comparing their own performance to that of others ( Roy et al., 2015 ). A more recent study by Kulakow (2020) , which compared two learning environments, revealed that students following a competency-based DI learning approach reported higher levels of academic self-concept over students engaged with the traditional learning approach.

Further Predictors of Students’ Well-Being, Social Inclusion and Academic Self-Concept

Students’ outcomes (in this case, students’ well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept) can be influenced not only by variables on teachers’ level (teachers’ use of DI, as discussed beforehand) but also those on students’ level. One of the most investigated student-specific predictors in previous studies was students’ gender. For school well-being, previous literature results showed a positive effect on females ( Schneekloth and Anderesen, 2013 ; Walsen, 2013 ; Venetz et al., 2019 ). Similarly, based on the past research, girls felt higher levels of social inclusion compared to boys ( Ato et al., 2014 ; Krull et al., 2018 ). For students’ academic self-concept, however, it’s the opposite: girls showed lower levels of academic self-concept than boys ( Venetz et al., 2019 ).

Next to gender, having special education needs (SEN) was also discussed as a possible predictor of students’ outcomes. Results showed that students with SEN are more likely to be socially excluded than students without SEN ( Koster et al., 2010 ; Schwab, 2015 ; Avramidis et al., 2017 ; Avramidis et al., 2018 ). Quite clearly, students with SEN showed much lower levels of academic self-concept compared to their peers without SEN labels ( Bear et al., 2002 ; Cambra and Silvestre, 2003 ; Zeleke, 2004 ). For school well-being, however, the results were more unclear. Some study outcomes indicated lower levels of school well-being for students with SEN ( McCoy and Banks, 2012 ; Skrzypiec et al., 2016 ), while others did not investigate any group differences ( Venetz et al., 2019 ; Zurbriggen et al., 2018 ).

In addition to students’ level, context variables have been considered by previous studies, especially the school setting (e.g., special schools compared to regular schools). For instance, previous research identified that students with SEN who attend special schools have a more positive academic self-concept compared to students with SEN who attend regular schools ( Bear et al., 2002 ; Marsh et al., 2006 ; Knickenberg et al., 2019 ). For social inclusion and school well-being, Knickenberg et al. (2019) did not find any group differences between students with SEN attending special and those attending regular schools.

The Importance of Students’ Perspectives

In implementing an inclusive teaching practice, teachers plan and design learning situations to meet students’ educational needs. Therefore, they can be conceived as recipients of teachers’ pedagogical decisions and interventions. Against the background of this assumption, it seems inevitable that students’ perspectives be taken into account while investigating teaching and learning processes as well as their effectiveness, as the effects are consequences of measures aimed at satisfying students’ diverse educational needs ( Montuoro and Lewis, 2015 ). By highlighting students’ voices in the context of educational research, a distortion of the inclusive reality in classrooms can be prevented, as there is a risk of self-serving over-reporting strategies when it comes to the investigation of classroom phenomena by focusing of teacher samples ( Wallace et al., 2016 ; Faddar et al., 2018 ; Göllner et al., 2018 ).

Purpose and Research Question

Most research that explores the effectiveness of DI has mainly focused on investigating its impact on students’ achievement. Research which analyzes the impact of DI on students’ non-achievement outcomes are relatively limited ( Schwab and Alnahdi, 2020 ). As variables such as students’ school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept are also central objectives of inclusive education and education in general ( Schwab et al., 2020 ), it is necessary to address this research gap.

In this context, the aim of this study is to identify determinants of students’ school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept based on their teachers’ DI practice. With this background, the research question guiding this study is as follows:

Is teachers’ DI practice positively associated with students’ school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept?

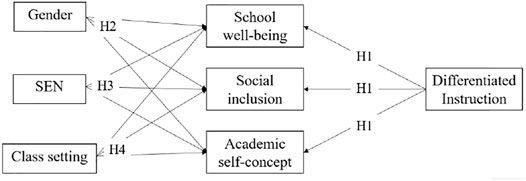

Based on the existing research discussed in this paper, and as seen from Figure 1 , it is hypothesized that students’ perception of their teachers’ use of DI will predict their perceived school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept ( Alnahdi et al., 2021 ; Kulakow, 2020 ; Roy et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, it is assumed that female participants perceive a higher level of school well-being and social inclusion but a lower academic self-concept when in comparison with their male participants ( Schneekloth and Anderesen, 2013 ; Walsen, 2013 ; Venetz et al., 2019 ). In contrast, students with SEN perceive lower levels of school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept. Finally, it is expected that the class setting plays an important role on students’ socioemotional variables. Thus, it is hypothesized that participants in inclusive classes perceive higher levels of socioemotional well-being and academic self-concept ( Schwab et al., 2015a ; Hascher, 2017 ).

FIGURE 1 . Study’s research model.

Sampling and Sample

The analyses of this study were conducted using data from the ATIS-SI study (Attitudes towards Inclusion of Students with Disabilities related to Social Inclusion; Schwab, 2015 ). The ATIS-SI study is a longitudinal study with three measurement points and the main objective was to explore the relationships between attitudes SEN and social inclusion in primary and secondary education. Informed consent was obtained from participants and their parents, and the research was approved by the Styrian Regional School Authority. Depending on the class, the time required for filling out the paper-and-pencil questionnaire took approximately 40–50 min. Members from the research team supported students with difficulties (especially those with SEN) in order to ensure that all students understood the instructions. The third series of measurements (on which this study is based) took place at the end of the eight-school grade (May to June 2015) and which included within its instrumentation, scales that explore students’ academic self-concept.

A total of 32 eight grade secondary school classes across three Austrian states (Styria, Lower Austria and Burgenland) were contacted by telephone and asked whether they would be willing to take part in the study. From the 32 secondary school classes contacted, only 23 accepted to participate in the study. The current sample consisted of 379 eight grade (age = 13–15 years) students (49% male, 51% female). Here, 46% of the students were educated in inclusive classes, whereas 54% attended regular classes. Out of this sample, 36 students (n M = 23; n F = 13) were diagnosed as having SEN.

In Austria, students with SEN need an official label by the local educational authority in order to be eligible for additional resources ( Schwab et al., 2015b ). Thus, class teachers were asked to list all children in their class that were officially labelled as having SEN. In the current study, no subgroups were distinguished because of the low number of students with SEN types other than learning disabilities (e.g., behavioral disorders). Furthermore, given that neither school achievement or intelligence was assessed within this study, it was not possible to differentiate between levels of severity of SEN. This means that SEN in this study mostly refers to SEN regarding learning disabilities but also includes a small number of students with other disabilities.

Instruments

Students’ school well-being and social inclusion.

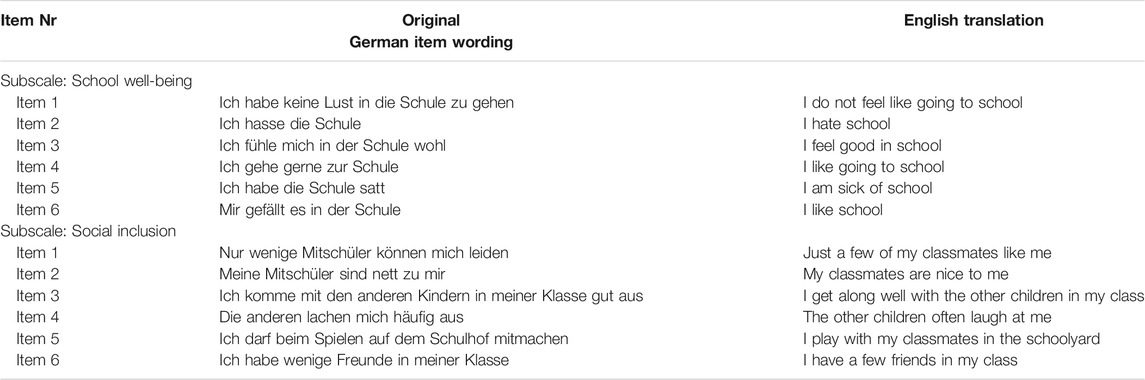

Students’ school well-being and social inclusion were measured using two subscales from the FEESS [Fragebogen zur Erhebung sozialer und emotionaler Schulerfahrungen/questionnaire for recording social and emotional school experiences] questionnaire by Rauer and Schuck (2003) . The original scale of “school well-being” consists of 14 items based on a 4-point-Likert scale (1 = not true at all to 4 = completely true ). However, for the current study, only 6 of the 14 items were used. Nonetheless, the reliability of the scale was high for the current sample (α = 0.91). The original scale of “social inclusion” consists of 11 items based on a 4-point-Likert scale (1 = not true at all to 4 = completely true). Nonetheless, for the present study, only six items were used (α = 0.83 for the current sample). Please refer to Table 1 to find the list of the items of each of the subscales selected for this study. It is important to highlight that earlier research using the FEESS subscales of school well-being and social inclusion have been found that the psychometric properties are suitable for students with and without special education needs in primary (e.g. Huber and Wilbert, 2012 ; Schwab et al., 2015c ; Heyder et al., 2020 ) as well as secondary grades (Frankenberg et al., 2016).

TABLE 1 . FEESS ( Rauer and Schuck, 2003 ): items selected for the current study.

Students’ Academic Self-Concept

Students’ academic self-concept was measuring using the general academic self-concept subscale from the SESSKO [Skalen zur Erfassung schulischen Selbstkonzepts/scales for recording the academic self-concept] questionnaire by Schöne, Dickhäuser, Spinath, and Stiensmeier-Pelster (2002) . The subscale consists of five items based on a 5-point-Likert scale (e.g., “I am”, 1 = not intelligent to 5 = intelligent ) (α = 0.88 for the current sample).

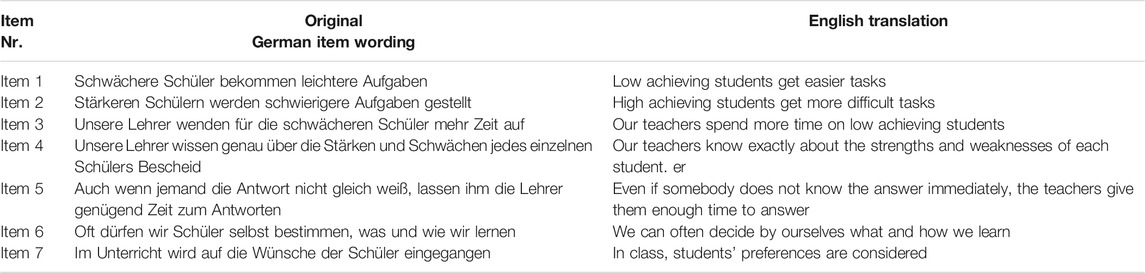

Students’ Ratings of their Teachers’ Use of DI

In order to measure students’ ratings of their teachers’ DI practice, the differentiated teaching scale by Gebhardt et al. (2014) (please refer to Table 2 ), which stems from previous work developed by Feyerer (1998) , was utilized. The scale consists of seven items and is based on a 5-point-Likert scale (e.g., “Higher achieving students get more difficult exercises”, 1 = never to 5 = always ) (α = 0.76 for the current sample).

TABLE 2 . English translation of the Differentiated Teaching Scale by Gebhardt et al. (2014) .

The nested structure of the data (students nested within classrooms) was considered by multilevel regression analyses (Level 2: classes, Level 1: individual student). As suggested by Ryu (2015) , all metric variables at Level 1, such as students’ ratings of their teachers’ DI practice and students’ school well-being, school inclusion and academic self-concept, were centered at the grand mean. Three different models were calculated for each outcome variable (school well-being, school inclusion and academic self-concept). For each of these three models, first, a model where no predictors were entered (model without any independent variables) was calculated to estimate the variance at Level 2. Following this, a model with predictors at the student level (gender, SEN, ratings of DI) and predictors at the class level (school setting) was calculated.

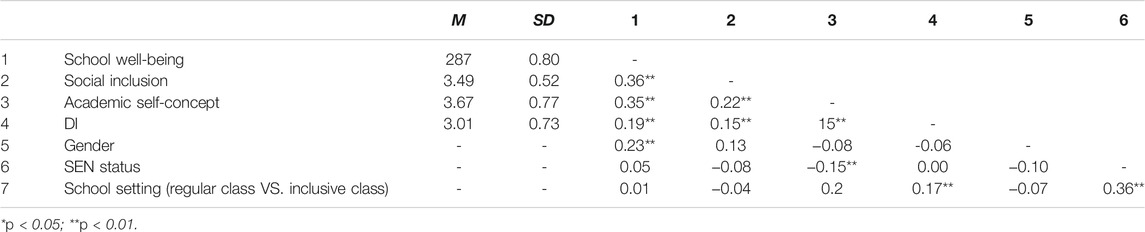

In relation to students’ reports of their teachers use of DI, the scale mean for the whole sample was 3.01 ( SD = 0.73). A t -test for dependent samples revealed that students’ ratings for their teachers’ use of DI did not significantly differ from the theoretical mean of the scale (M = 3, as the scale ranges from 1 to 5). This indicates that teachers make use of DI in the teaching practice rather occasionally.

For students’ social-emotional variables, t-tests for dependent samples indicated that students’ ratings of their school well-being [ t (377) = 9.02, p <.001], social inclusion [ t (377) = 36.85, p <.001] and academic self-concept [ t (375) = 16.79, p < 0.001] were significantly higher than the theoretical mean of the scale (M = 2.5 for well-being and social inclusion and M = 3 for academic self-concept). Such results imply that students experience higher school well-being, perceive higher values of social inclusion and have a greater academic self-concept.

Table 3 presents an overview of the means, standard deviations and the inter-correlations of all the variables. For dummy-coded variables, i.e., gender and school setting, point biserial correlation coefficients were calculated. However, for metric variables, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated. Results show that students’ school well-being and social inclusion is higher in girls than in boys. Furthermore, classrooms with more differentiated instruction differentiated instruction correlates positively with students’ school well-being, social inclusion and global self-concept. Moreover, the correlation analysis indicates that students with SEN have significantly lower academic self-concepts. However, the school setting did not appear to be related to students’ school well-being, social inclusion or to their academic self-concept.

TABLE 3 . Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all scales.

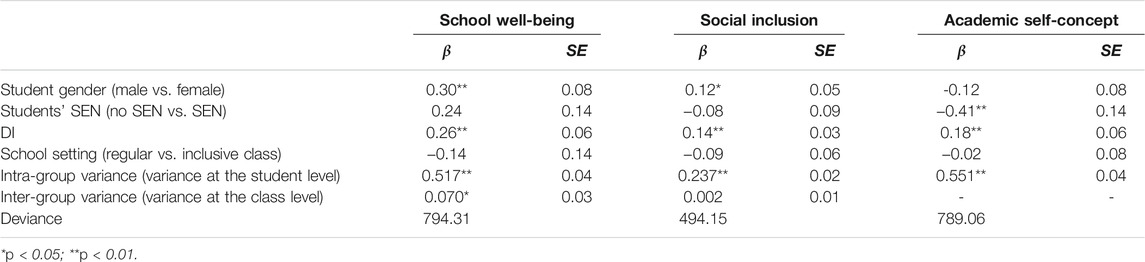

For the subscale of “school well-being” (see Table 4 ), the model, without any predictor, showed that 13.5% of the variance (Wald z = 2.44, p < 0.05) is explained at the class level. In the following model with all predictors, students’ gender ( β = 0.30, SE = 0.08, t (352.91) = 3.66, p < 0.01) as well as ratings of teachers’ use of DI ( β = 0.26, SE = 0.06, t (347.98) = 4.40, p < 0.01) showed a significant influence on students’ individual level and explained a variance of around 52%. The results indicated that being female and rating the instruction as more differentiated is related to greater school well-being. However, students’ SEN status and school settings did not predict students’ school well-being.

TABLE 4 . Estimates of the multilevel regression analyses to predict attitudes towards school, social integration, and school concept (Model 2 with predictors).

For of the subscale of “social inclusion,” the first model without predictors showed that only 5.2% of the variance (Wald z = 1.61, n.s. ) is explained at the class level. This indicated that there is no significant variance at the class level. When entering all the predictors into Model 2, the analyses revealed that students’ gender ( β = 0.23, SE = 0.05, t (308.70) = 2.34, p <.05) and ratings of DI [ β = 0.14, SE = 0.04, t (223.12) = 3.81, p < 0.01] were significant predictors at Level 1 (see Table 4 ) and explained a variance of around 24%. In detail, being female and rating teachers’ instruction as more differentiated appeared to be associated with more positive social inclusion among students in a classroom.

Finally, in relation to the subscale of “academic self-concept,” the first model without any predictors did not explain any variance at all, indicating that there was no significant variance at the class level. The second model, introducing all the predictors, revealed that the predictors of students’ SEN status [ β = −0.41, SE = 0.14, t (352) = −2.96, p < 0.01) and ratings of DI [ β = 0.18, SE = 0.06, t (352) = 3.19, p < 0.01) had a significant influence at students’ individual level and explained a variance of around 55%. Not having a SEN and rating the instruction as more differentiated seemed to be related to a higher academic self-concept (see Table 4 ). All other predictors were not significant.

Inclusive education aims to support every student’s achievement outcome as well as non-achievement outcome (e.g., social-emotional outcome, social development) (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2017; Zurbriggen et al., 2021 ). However, at present, empirical evidence supporting the impact of DI on students’ non-achievement outcomes is scarce ( Schwab et al., 2020 ). The present study has analyzed predictors of students’ school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept by looking at students’ individual characteristics (gender, SEN status, ratings of their teachers’ DI practice) and classroom factors (school setting) in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the predictors of students’ non-achievement outcomes.

As a result, seventh-grade students from Austria perceive that their teachers infrequently implement DI. Although there appears to be intercountry differences regarding teachers’ DI implementation ( van de Grift et al., 2017 ; Maulana et al., 2020 ), this result is consistent with previous international studies, which have indicated that, in general, teachers rarely differentiate their instruction ( De Neve et al., 2015 ; Schleicher, 2016 ; Pozas and Schneider, 2019 ; van Geel et al., 2019 ). This result is not surprising given the fact that the literature has highlighted the practice of DI as a relatively demanding and challenging approach ( Gaitas and Alves Martins, 2016 ; van Geel et al., 2019 ). Bearing in mind that DI has been conceptualized as a domain of teaching quality ( Maulana et al., 2020 ) and that empirical evidence has revealed it to be a typical teaching behavior of highly effective teachers ( van de Grift et al., 2017 ), it is important to focus on strategies to guide and coach teachers to develop and improve their DI practice.

In line with previous research, descriptive results further indicated that students reported relatively high ratings of school-wellbeing, social inclusion and academic self-concept ( Alnahdi and Schwab, 2020 ; Schwab and Alnahdi, 2020 ; Zubriggen et al., 2021 ). However, high mean scores do not automatically imply that all students are reaching satisfying levels in their socio-emotional well-being. In detail, within the present sample, a total of 12% of the students would be considered to be at risk. Therefore, students’ social-emotional well-being should also be an important point of focus for at-risk students, and appropriate prevention and intervention strategies are necessary to be implemented.

The effects of student and classroom variables as determinants of students’ school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept constitute the research goal of this specific study, as they were focused on less often in other studies. The results of the multilevel analyses showed that only the subscale of “school well-being” had a significant variance at the class level. Both literature and research have emphasized that school well-being is an outcome of inclusion ( Schwab, 2015 ; Hascher, 2017 ). According to Hascher and Lobsang (2004) , students’ school well-being is strongly determined by the social relationships among students. Hence, the results emphasize the argument that both the individual and the contextual (classrooms) are decisive for the development and fostering of students’ well-being ( Rossetti, 2012 ; Garotte, 2016 ; Hascher, 2017 ). For the other two subscales, the results from the multilevel analyses lead to the conclusion that social inclusion and academic self-concept are determined by variables at the individual students’ level. In particular, for students’ academic self-concept, such a result seems to be in line with the outcome from ( Roy et al., 2015 ) study. However, this result is very surprising, as effects, such as Effect (BFLPE; Marsh et al., 2008 ; Seaton et al., 2010 ) would rather suggest a strong influence of the context.

While focusing on the predictors at the individual level, variables that were noted to significantly contribute to predicting students’ school well-being and social inclusion were gender and DI. In detail, the findings are in line with previous studies, which revealed that girls hold higher levels of school well-being ( Schneekloth and Anderesen, 2013 ; Walsen, 2013 ) and more positive experiences of social inclusion ( Ato et al., 2014 ; Krull et al., 2018 ). Surprisingly, students’ SEN status did not have affect their school-wellbeing and social inclusion. Additionally, and interestingly, students’ ratings of their teachers’ DI implementation were found to be a significant predictor. A possible explanation for this result might be the fact that students feel more appreciated and included in the social, emotional and academic classroom setting when they perceive their teachers’ ambition to provide adequate teaching and learning stimuli for them ( Lindner et al., 2019 ). Hence, it can be assumed that teachers’ didactic adaption of teaching and learning processes to the individual needs of students in a class directly affects their school-wellbeing, social inclusion and academic self-concept in a positive way. As a significant part of DI includes organizational aspects, such as using elaborated practices to group students ( Vaughn et al., 2007a ), more positive contact experiences between peers might result due to the implementation of this practice. Theoretically underpinned within the inter-group contact theory ( Allport, 1954 ; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2000 ), it can be assumed that positive contact between peers leads to higher levels of social inclusion. Further, students’ school well-being is strongly determined by social relationships among students ( Hascher and Lobsang, 2004 ), which might moderate the effect between school well-being and DI. A possible explanation may be that as DI seeks to match teaching to students’ individual abilities ( Roy et al., 2015 ), guided by their needs and interests ( Nusser and Gehrer, 2020 ), and pertains to cooperative practices as well as the choice regarding whom to work in a group with ( Juvonen et al., 2019 ; Zurbriggen et al., 2021 ), such a teaching approach could foster positive attitudes and social interaction and facilitate caring and supporting interactions among classmates.

With regard to academic self-concept, multilevel analyses revealed that, unsurprisingly, students’ SEN status and their ratings on their ratings of their teachers’ DI practice contributed significantly as predictors. Consistent with previous research, the findings from this study indicate that students with SEN have a lower academic self-concept compared to their classmates without SEN ( Venetz et al., 2015 ; DeVries et al., 2018 ; Knickenberg et al., 2019 ; Alnahdi and Schwab, 2020 ). A practical need addressed with this finding might be the great importance of using an individual reference standard orientation while providing feedback to students with SEN in inclusive classes. According to the BFLPE, students are referring to their own perception of their achievement with the mean achievement of their peers. Certainly, having SEN usually indicates lower achievement compared to peers. Therefore, it is important for such students to also realize their individual improvement of competencies and not be solely compared with their peers. An important result is the fact that students’ perceptions of their teachers’ DI implementation significantly predict academic self-concept. A previous study by Kulakow (2020) , which explored differentiated learning activities by means of competence-based learning, indicated that students following such an approach reported higher levels of academic self-concept. Thus, taken together, all these findings indicate that differentiated practices matching students’ abilities are significant in decreasing peer comparisons and foster self-assessments of ability ( Roy et al., 2015 ). However, in a study by Roy et al. (2015) , this effect was revealed to be significant only for low-achieving students. Comparing the present results with the results of ( Roy et al., 2015) , it is not possible to state whether low-achieving students benefit from the practice of DI, mainly due to the fact that the data did not permit the attainment of such differentiated results. At the very least, it can be assumed that for students with SEN, providing DI may not be enough to reduce social comparison and offset the BFLPE. More longitudinal research is required in order to explore this notion in greater depth.

While interpreting the present results, one has to keep in mind that this study has several limitations. First, the present study is based solely on cross-sectional results. Consequently, causality of the results cannot be determined. Further studies with a longitudinal design are required to investigate the causal influences of DI on students’ school-wellbeing, social inclusion and academic self-concept. Additionally, it is also recommended that the variable of students’ performance be included as a control variable in such longitudinal studies. Following such a design, it would be possible to explore the casual relationships between teachers’ DI practice and students’ achievement and non-achievement outcomes. A second limitation concerns the assessment of teachers’ DI practices by means of student reports. Although surveys addressing students’ perspectives are economical, recommended in research and possess validity ( Butler, 2012 ), it is possible that students might incorrectly assess their teachers’ differentiation practice, given their lack of didactical knowledge. In this context, Fauth et al., (2014) argued that different dimensions of instructional practices cannot be observed in the same way. However, based on the study results, Schwab and Alnahdi (2020) argued that solely using teachers’ ratings or judgements as a substitution of students’ own perceptions would be inappropriate. Thus, it is strongly suggested that future studies integrate all stakeholders’ perspectives, i.e., the perspectives of students and teachers. Moreover, in order to gain more in-depth data, it would be prudent to use a combined research methodology, for example, quantitative data (e.g., questionnaires) and qualitative data (e.g., interviews, classroom observations). In particular, teacher interviews could shed light on how the teachers plan and design a differentiated lesson. This might provide deeper insights into teachers’ purposes or intentions behind using particular DI practices. On the other hand, to obtain a broader picture of students’ perceptions and how they are influenced by DI, research could use the experience sampling method and assess students’ emotional experiences. A third limitation is the small sample size of students with SEN. This limited the opportunity to obtain differentiated results between students with different kinds of SEN.

Outcomes of inclusive schooling are not limited to students’ academic achievement but are also relevant to their well-being at school, social inclusion and academic self-concept. Moreover, several researchers have emphasized that in order to understand students’ needs, it is of upmost importance to listen to students’ own perspectives. However, till now, studies that use students’ own voices and those which empirically explore the link between DI and their school well-being, social inclusion and academic self-concept have been quite limited. The present study addressed such issues in the existing literature and provided evidence on the significant role that teachers’ practice of DI can have on fostering students’ socio-emotional outcomes. With this background, the findings from this study urge for more research to be conducted into the topic in order to secure a detailed depiction of how the practice of DI influences students’ outcomes. This, in return, will serve as empirical evidence and solidify the effectiveness and usefulness of DI.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data contains information that could compromise research participant privacy and/or consent. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Susanne Schwab.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Regional school authorities of Styria, Lower Austria, and Burgenland. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

The research concern as well as the interpretation and discussion were developed in a joint involvement of all the authors. MP focused on the development of ideas and was significantly involved in the data analysis and drafting of the results. VL dealt with the evaluation of the data and their interpretation and discussion. MP and VL together established a draft of the discussion sections. K-TL was responsible for the literature research, the consolidation of all ideas and the writing of the introduction and theoretical background. SS supported the research of literature and was responsible for data collection and development of the aim, focus and discussion section of the paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Svenja Hoffmann for her valuable contribution and support.

Ainscow, M., and Messiou, K. (2018). Engaging with the Views of Students to Promote Inclusion in Education. J. Educ. Change 19 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10833017-9312-110.1007/s10833-017-9312-1

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice . New York: Doubleday Anchor Books .

Google Scholar

Alnahdi, G. H., and Schwab., S. (2020). Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the Behavioral Intention to Interact with Peers with Intellectual Disability Scale. Front. Psychol. 11, 1212. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01212

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alnahdi, G. H., Lindner, K.-T., Elhadi, A., and Schwab, S. (2021). Students’ Perception of Inclusion and Inclusive Teaching Practices in Saudi Arabia .

Ato, E., Galián, M. D., and Fernández-Vilar, M. A. (2014). Gender as predictor of social rejection: the mediating/moderating role of effortful control and parenting. [El género como predictor de rechazo social: el papel mediador/moderador del control con esfuerzo y crianza de los hijos]. analesps 30 (3), 1069–1078. doi:10.6018/analesps.30.3.193171

Avramidis, E., Avgeri, G., and Strogilos, V. (2018). Social Participation and friendship Quality of Students with Special Educational Needs in Regular Greek Primary Schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 33 (2), 221–234. doi:10.1080/08856257.2018.1424779

Avramidis, E., Strogilos, V., Aroni, K., and Kantaraki, C. T. (2017). Using Sociometric Techniques to Assess the Social Impacts of Inclusion: Some Methodological Considerations. Educ. Res. Rev. 20, 68–80. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.004

Bear, G. G., Minke, K. M., and Manning, M. A. (2002). Self-Concept of Students with Learning Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 31 (3), 405–427. doi:10.1080/02796015.2002.12086165

Bondie, R. S., Dahnke, C., and Zusho, A. (2019). How Does Changing "One-Size-Fits-All" to Differentiated Instruction Affect Teaching? Rev. Res. Edu. 43 (1), 336–362. doi:10.3102/0091732X18821130

Butler, R. (2012). Striving to Connect: Extending an Achievement Goal Approach to Teacher Motivation to Include Relational Goals for Teaching. J. Educ. Psychol. 104 (3), 726–742. doi:10.1037/a0028613

Cambra, C., and Silvestre, N. (2003). Students with Special Educational Needs in the Inclusive Classroom: Social Integration and Self-Concept. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 18 (2), 197–208. doi:10.1080/0885625032000078989

De Neve, D., Devos, G., and Tuytens, M. (2015). The Importance of Job Resources and Self-Efficacy for Beginning Teachers' Professional Learning in Differentiated Instruction. Teach. Teach. Edu. 47, 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.003

Decristan, J., Fauth, B., Kunter, M., Büttner, G., and Klieme, E. (2017). The Interplay between Class Heterogeneity and Teaching Quality in Primary School. Int. J. Educ. Res. 86, 109–121. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2017.09.004

Deunk, M. I., Smale-Jacobse, A. E., de Boer, H., Doolaard, S., and Bosker, R. J. (2018). Effective Differentiation Practices:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies on the Cognitive Effects of Differentiation Practices in Primary Education. Educ. Res. Rev. 24, 31–54. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.002

DeVries, J. M., Voß, S., and Gebhardt, M. (2018). Do Learners with Special Education Needs Really Feel Included? Evidence from the Perception of Inclusion Questionnaire and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Res. Dev. Disabil. 83, 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2018.07.007

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2017). European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2014 Dataset Cross-Country Report.” Unpublished Manuscript. Available at: https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/european-agency-statistics-inclusive-education-2014-dataset-cross-country (last modified January 06, 2020).

Faddar, J., Vanhoof, J., and de Maeyer, S. (2018). School Self-Evaluation: Self-Perception or Self-Deception? the Impact of Motivation and Socially Desirable Responding on Self-Evaluation Results. Sch. effectiveness Sch. improvement 29 (1), 660–678. doi:10.1080/09243453.2018.1504802

Fauth, B., Decristan, J., Rieser, S., Klieme, E., and Büttner, G. (2014). Grundschulunterricht aus Schüler-, Lehrer- und Beobachterperspektive: Zusammenhänge und Vorhersage von Lernerfolg*. Z. für Pädagogische Psychol. 28 (3), 127–137. doi:10.1024/1010-0652/a000129

Feyerer, E. (1998). Behindern Behinderte? Integrativer Unterricht Auf Der Sekundarstufe I. Innsbruck . Innsbruck, Austria: Studien-Verlag .

Gaitas, S., and Alves Martins, M. (2016). Teacher Perceived Difficulty in Implementing Differentiated Instructional Strategies in Primary School. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. 21 (5), 544–556. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1223180

Garotte, A. (2016). Soziale Teilhabe Von Kindern in Inklusiven Klassen. Empirische Pädagogik 30 (1), 67–80.

Gebhardt, M., Schwab, S., Krammer, M., Gasteiger-Klicpera, B., and Sälzer, C. (2014). Erfassung von individualisiertem Unterricht in der Sekundarstufe I Eine Quantitative Überprüfung der Skala „Individualisierter Unterricht" in zwei Schuluntersuchungen in der Steiermark. Z. F Bildungsforsch 4 (3), 303–316. doi:10.1007/s35834-014-0095-7

Goddard, Y., Goddard, R., and Kim, M. (2015). School Instructional Climate and Student Achievement: An Examination of Group Norms for Differentiated Instruction. Am. J. Edu. 122 (1), 111–131. doi:10.1086/683293

Göllner, R., Wagner, W., Eccles, J. S., and Trautwein, U. (2018). Students’ Idiosyncratic Perceptions of Teaching Quality in Mathematics: A Result of Rater Tendency Alone or an Expression of Dyadic Effects between Students and Teachers? J. Educ. Psychol. 110 (5), 709–725. doi:10.1037/edu00

Hascher, T. (2017). “Die Bedeutung Von Wohlbefinden Und Sozialklima Für Inklusion,” in Profile Für Die Schul- Und Unterrichtsentwicklung in Deutschland, Österreich Und Der Schweiz . Editors B. Lütje-Klose, S. Miller, S. Schwab, and B. Streese (Münster: Waxmann ), 69–79.

Hascher, T., and Lobsang, K. (2004). “Das Wohlbefinden Von SchülerInnen - Faktoren, Die Es Stärken Und Solche, Die Es Schwächen,” in Schule Positiv Erleben: Erkenntnisse Und Ergebnisse Zum Wohlbefinden Von Schülerinnen Und Schülern . Editor T. Hascher (Bern: Haupt ), 203–228.

Heyder, A., Südkamp, A., and Steinmayr, R. (2020). How Are Teachers' Attitudes toward Inclusion Related to the Social-Emotional School Experiences of Students with and without Special Educational Needs? Learn. Individual Differences 77, 101776. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2019.101776

Huber, C., and Wilbert, J. (2012). Soziale Ausgrenzung von Schülern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf und niedrigen Schulleistungen im gemeinsamen Unterricht [Social exclusion of students with special educational needs and low academic achievement placed in general education classrooms]. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 4 (2), 147–165.

Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., and Smith, D. S. (2019). Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 54 (4), 250–270. doi:10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645

Kärner, T., Warwas, J., Krannich, M., and Weichsler, N. (2021). How Does Information Consistency Influence Prospective Teachers' Decisions about Task Difficulty Assignments? A Within-Subject experiment to Explain Data-Based Decision-Making in Heterogeneous Classes. Learn. Instruction 74 (3), 101440. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101440

Knickenberg, M., L. A. Zurbriggen, C., Venetz, M., Schwab, S., and Gebhardt, M. (2019). Assessing Dimensions of Inclusion from Students' Perspective - Measurement Invariance across Students with Learning Disabilities in Different Educational Settings. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 35 (3), 287–302. doi:10.1080/08856257.2019.1646958

Koster, M., Pijl, S. J., Nakken, H., and Van Houten, E. (2010). Social Participation of Students with Special Needs in Regular Primary Education in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Edu. 57 (1), 59–75. doi:10.1080/10349120903537905

Krull, J., Wilbert, J., and Hennemann, T. (2018). Does Social Exclusion by Classmates Lead to Behaviour Problems and Learning Difficulties or Vice Versa? A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 33 (2), 235–253. doi:10.1080/08856257.2018.1424780

Kulakow, S. (2020). Academic Self-Concept and Achievement Motivation Among Adolescent Students in Different Learning Environments: Does Competence-Support Matter? Learn. Motiv. 70 (3), 101632. doi:10.1016/j.lmot.2020.101632

Lindner, K.-H., Alnahdi, G. H., Wahl, S., and Schwab, S. (2019). Perceived Differentiation and Personalization Teaching Approaches in Inclusive Classrooms: Perspectives of Students and Teachers. Front. Edu. 4. doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00058

Lindner, K.-T., and Schwab, S. (2020). Differentiation and Individualisation in Inclusive Education: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. , 1–21. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1813450

Little, C. A., McCoach, D. B., and Reis, S. M. (2014). Effects of Differentiated Reading Instruction on Student Achievement in Middle School. J. Adv. Academics 25 (4), 384–402. doi:10.1177/1932202X14549250

Loreman, T. (2017). Pedagogy for Inclusive Education . Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education .

Marsh, H. W., Tracey, D. K., and Craven, R. G. (2006). Multidimensional Self-Concept Structure for Preadolescents with Mild Intellectual Disabilities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 66 (5), 795–818. doi:10.1177/0013164405285910

Marsh, H. W., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., and Köller, O. (2008). Social Comparison and Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effects on Self-Concept and Other Self-Belief Constructs: Role of Generalized and Specific Others. J. Educ. Psychol. 100, 510–524. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.510

Maulana, R., Smale-Jacobse, A., Helms-Lorenz, M., Chun, S., and Lee, O. (2020). Measuring Differentiated Instruction in the Netherlands and South Korea: Factor Structure Equivalence, Correlates, and Complexity Level. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 35 (4), 881–909. doi:10.1007/s10212-019-00446-4

McCoy, S., and Banks, J. (2012). Simply Academic? Why Children with Special Educational Needs Don't like School. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 27 (1), 81–97. doi:10.1080/08856257.2011.640487

McMurray, S., and Thompson, R. (2016). Inclusion, Curriculum and the Rights of the Child. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 16 (S1), 634–638. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.119510.1111/1471-3802.12195

Montuoro, P., and Lewis, R. (2015). “Student Perceptions of Misbehavior and Classroom Management,” in Handbook of Classroom Management . Editors E. T. Emmer, and E. J. Sabornie (New York: Routledge ), 344–62.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Nusser, L., and Gehrer, K. (2020). Addressing Heterogeneity in Secondary Education: Who Benefits from Differentiated Instruction in German Classes? Int. J. Inclusive Edu. , 1–18. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1862407

Petersen, A. (2016). Perspectives of Special Education Teachers on General Education Curriculum Access. Res. Pract. Persons Severe Disabilities 41, 19–35. doi:10.1177/1540796915604835

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2000). “Does Intergroup Contact Reduce Prejudice: Recent Meta-Analytic Findings,” in The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology" Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination . Editor S. Oskamp ( Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers ), 93–114.

Pit-ten Cate, I. M., Markova, M., Krischler, M., and Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2018). Promoting Inclusive Education: The Role of Teachers' Competence and Attitudes. Insights into Learn. Disabilites 15 (1), 49–63.

Pozas, M., and Letzel, V. (2019). 'I Think They Need to Rethink Their Concept!': Examining Teachers' Sense of Preparedness to deal with Student Heterogeneity. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 35 (3), 366–381. doi:10.1080/08856257.2019.1689717

Pozas, M., Letzel, V., and Schneider, C. (2020). Teachers and Differentiated Instruction: Exploring Differentiation Practices to Address Student Diversity. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 20 (3), 217–230. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12481

Pozas, M., and Schneider, C. (2019). Shedding Light into the Convoluted Terrain of Differentiated Instruction: Proposal of a Taxonomy of Within-Class Differentiation in the Heterogeneous Classroom. Open Edu. Stud.

Prast, Emilie. J., Eva van de Weijer-Bergsmaa, , Kroesbergena, Evelyn. H., Van Luit, J., and Johannes, E. H. (2015). Readiness-Based Differentiation in Primary School Mathematics: Expert Recommendations and Teacher Self-Assessment. Frontline Learn. Res. 3 (2), 90–116. doi:10.14786/flr.v3i2.163

Rauer, W., and Schuck, K. D. (2003). Fragebogen Zur Erfassung Emotionaler Und Sozialer Schulerfahrungen Von Grundschulkindern Erster Und Zweiter Klassen . Göttingen: Beltz .

Rossetti, Z. S. (2012). Helping or Hindering: The Role of Secondary Educators in Facilitating Friendship Opportunities Among Students with and without Autism or Developmental Disability. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. 16 (12), 1259–1272. doi:10.1080/13603116.2011.557448

Roy, A., Guay, F., and Valois, P. (2015). The Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect on Academic Self-Concept: The Moderating Role of Differentiated Instruction and Individual Achievement. Learn. Individual Differences 42 (2), 110–116. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.009

Ryu, E. (2015). Multiple-Group Analysis Approach to Testing Group Difference in Indirect Effects. Behav. Res. Methods 47 (2), 484–493. doi:10.3758/s13428-014-0485-8

Schleicher, A. (2016). Teaching Excellence Trough Professional Learning and Policy Reform: Lessons from Around the World, International Summit on the Teaching Professions . Paris: OECD Publishing .

Schneekloth, U., and Andersen, S. (2013). “Was Fair Und Was Unfair Ist: Die Verschiedenen Gesichter Von Gerechtigkeit,” in Kinder in Deutschland 2013: 3. World Vision Kinderstudie (Weinheim: Beltz ), 48–78. World Vision Deutschland

Schöne, C., Dickhäuser, O., Spinath, B., and Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (2002). Skalen Zur Erfassung Des Schulischen Selbstkonzepts - SESSKO . Göttingen: Hogrefe .

Schwab, S., Rossmann, P., Tanzer, N., Hagn, J., Oitzinger, S., Thurner, V., et al. (2015b). School Well-Being of Students with and without Special Educational Needs-Aa Comparison of Students in Inclusive and Regular Classes. Z. Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 43, 265–274. doi:10.1024/1422-4917/a000363

Schwab, S., Zurbriggen, C. L. A., Venetz, M., and Martin, Venetz. (2020). Agreement Among Student, Parent and Teacher Ratings of School Inclusion: A Multitrait-Multimethod Analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 82, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2020.07.003

Schwab, S., and Alnahdi, G. (2020). Do they Practise what They Preach? Factors Associated with Teachers' Use of Inclusive Teaching Practices Among In‐service Teachers. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 20 (4), 321–330. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12492

Schwab, S., Hessels, M. G. P., Obendrauf, T., Polanig, M. C., and Wölflingseder, L. (2015a). Assessing Special Educational Needs in Austria: Description of Labeling Practices and Their Evolution from 1996 to 2013. J. Cogn. Educ. Psych 14 (3), 329–342. doi:10.1891/1945-8959.14.3.329

Schwab, S., Holzinger, A., Krammer, M., Gebhardt, M., and Hessels, M. G. P. (2015c). Teaching Practices and Beliefs about In-Clusion of General and Special Needs Teachers in Austria. A Contemp. J. 13, 237–254.

Schwab, S. (2020). Inclusive and Special Education in Europe . Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education Oxford University Press . doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1230Inclusive and Special Education in Europe

Schwab, S. (2015). Social Dimensions of Inclusion in Education of 4th and 7th Grade Pupils in Inclusive and Regular Classes: Outcomes from Austria. Res. Dev. Disabilities 43-44, 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.06.005

Seaton, M., Marsh, H. W., and Craven, R. G. (2010). Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect. Am. Educ. Res. J. 47, 390–433. doi:10.3102/0002831209350493

Skrzypiec, G., Askell-Williams, H., Slee, P., and Rudzinski, A. (2016). Students with Self-Identified Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (Si-SEND): Flourishing or Languishing!. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Edu. 63 (1), 7–26. doi:10.1080/1034912x.2015.1111301

Smale-Jacobse, A. E., Meijer, A., Helms-Lorenz, M., and Maulana, R. (2019). Differentiated Instruction in Secondary Education: A Systematic Review of Research Evidence. Front. Psychol. 10, 2366. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02366

Smit, R., and Humpert, W. (2012). Differentiated Instruction in Small Schools. Teach. Teach. Edu. 28 (8), 1152–1162. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.07.003

Steenbergen-Hu, S., Makel, M. C., and Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (2016). What One Hundred Years of Research Says about the Effects of Ability Grouping and Acceleration on K-12 Students' Academic Achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 849–899. doi:10.3102/0034654316675417

Suprayogi, M. N., and Valcke, M. (2016). Differentiated Instruction in Primary Schools: Implementation and Challenges in Indonesia. Ponte 72 (6), 2–18. doi:10.21506/j.ponte.2016.6.1

Tomlinson, C. (2014). The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners , 2. Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD . Auflage.

UNESCO (2020). “Global Education.” Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All .

Valiandes, S. (2015). Evaluating the Impact of Differentiated Instruction on Literacy and reading in Mixed Ability Classrooms: Quality and Equity Dimensions of Education Effectiveness. Stud. Educ. Eval. 45, 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.02.005

van de Grift, W. J. C. M., Chun, S., Maulana, R., Lee, O., Helms-Lorenz, M., and Helms-Lorenz, Michelle. (2017). Measuring Teaching Quality and Student Engagement in South Korea and the Netherlands. Sch. effectiveness Sch. improvement 28 (3), 337–349. doi:10.1080/09243453.2016.1263215

van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., and Visscher, A. J. (2019). Capturing the Complexity of Differentiated Instruction. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 30, 51–67. doi:10.1080/09243453.2018.1539013

Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., Woodruff, A. L., and Linan-Thompson, S. (2007a). “Prevention and Early Identification of Students with Reading Disabilities,” in Evidence-Based Reading Practices for Response to Intervention . Editors D. Haager, J. Klinger, and S. Vaughn (Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing ), 11–28.

Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., and Denton, C. A. (2007b). “"Teaching Elementary Students Who Experience Difficulties in Learning,” in The SAGE Handbook of Special Education . Editor L. Florian (Trowbridge: The Cromwell Press Ltd ), 360–377.

Venetz, M., Zurbriggen, C. L. A., and Schwab, S. (2019). What Do Teachers Think about Their Students' Inclusion? Consistency of Students' Self-Reports and Teacher Ratings. Front. Psychol. 10, 1637. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01637

Venetz, M., Carmen, L. A., Eckhart, Z. M., Schwab, S., and Hessels, M. G. P. (2015). The Perceptions of Inclusion Questionnaire (PIQ). Available at: https://piqinfo.ch/ (Accessed June 17, 2021).

Wallace, T. L., Kelcey, B., and Ruzek, E. (2016). What Can Student Perception Surveys Tell Us about Teaching? Empirically Testing the Underlying Structure of the Tripod Student Perception Survey. Am. Educ. Res. J. 53 (6), 1834–1868. doi:10.3102/0002831216671864

Walsen, J. C. (2013). Das Wohlbefinden Von Grundschulkindern: Soziale Und Emotionale Schulerfahrung in Der Primarstufe . Oldenburg: Universität Oldenburg .

Zeleke *, S. (2004). Self‐concepts of Students with Learning Disabilities and Their Normally Achieving Peers: a Review. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 19 (2), 145–170. doi:10.1080/08856250410001678469

Zurbriggen, C. L. A., Hofmann, V., Lehofer, M., and Schwab, S. (2021). Social Classroom Climate and Personalised Instruction as Predictors of Students' Social Participation. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. 30 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/13603116.2021.1882590

Zurbriggen, C. L. A., Venetz, M., and Hinni., C. (2018). The Quality of Experience of Students with and without Special Educational Needs in Everyday Life and when Relating to Peers. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 33 (2), 205–220. doi:10.1080/08856257.2018.1424777

Keywords: inclusive education, differentiated instruction (DI), students’ perception, school well-being, social inclusion, academic self-concept

Citation: Pozas M, Letzel V, Lindner K-T and Schwab S (2021) DI (Differentiated Instruction) Does Matter! The Effects of DI on Secondary School Students’ Well-Being, Social Inclusion and Academic Self-Concept. Front. Educ. 6:729027. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.729027

Received: 22 June 2021; Accepted: 16 November 2021; Published: 10 December 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Pozas, Letzel, Lindner and Schwab. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katharina-Theresa Lindner, [email protected] ; Susanne Schwab, [email protected]

Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction involves teaching in a way that meets the different needs and interests of students using varied course content, activities, and assessments.

Teaching differently to different students

Differentiated Instruction (DI) is fundamentally the attempt to teach differently to different students, rather than maintain a one-size-fits-all approach to instruction. Other frameworks, such as Universal Design for Learning , enjoin instructors to give students broad choice and agency to meet their diverse needs and interests. DI distinctively emphasizes instructional methods to promote learning for students entering a course with different readiness for, interest in, and ways of engaging with course learning based on their prior learning experiences ( Dosch and Zidon 2014).

Successful implementation of DI requires ongoing training, assessment, and monitoring (van Geel et al. 2019) and has been shown to be effective in meeting students’ different needs, readiness levels, and interests (Turner et al. 2017). Below, you can find six categories of DI instructional practices that span course design and live teaching.

While some of the strategies are best used together, not all of them are meant to be used at once, as the flexibility inherent to these approaches means that some of them are diverging when used in combination (e.g., constructing homogenous student groups necessitates giving different types of activities and assessments; constructing heterogeneous student groups may pair well with peer tutoring) (Pozas et al. 2020). The learning environment the instructor creates with students has also been shown to be an important part of successful DI implementation (Shareefa et al. 2019).

Differentiated Assessment

Differentiated assessment is an aspect of Differentiated Instruction that focuses on tailoring the ways in which students can demonstrate their progress to their varied strengths and ways of learning. Instead of testing recall of low-level information, instructors should focus on the use of knowledge and complex reasoning. Differentiation should inform not only the design of instructors’ assessments, but also how they interpret the results and use them to inform their DI practices.

More Team Project Ideas

Steps to consider

There are generally considered to be six categories of useful differentiated instruction and assessment practices (Pozas & Schneider 2019):

- Making assignments that have tasks and materials that are qualitatively and/or quantitatively varied (according to “challenge level, complexity, outcome, process, product, and/or resources”) (IP Module 2: Integrating Peer-to-Peer Learning) It’s helpful to assess student readiness and interest by collecting data at the beginning of the course, as well as to conduct periodic check-ins throughout the course (Moallemi 2023 & Pham 2011)

- Making student working groups that are intentionally chosen (that are either homogeneous or heterogeneous based on “performance, readiness, interests, etc.”) (IP Module 2: Integrating Peer-to-Peer Learning) Examples of how to make different student groups provided by Stanford CTL (Google Doc)

- Making tutoring systems within the working group where students teach each other (IP Module 2: Integrating Peer-to-Peer Learning) For examples of how to support peer instruction, and the benefits of doing so, see for example Tullis & Goldstone 2020 and Peer Instruction for Active Learning (LSA Technology Services, University of Michigan)

- Making non-verbal learning aids that are staggered to provide support to students in helping them get to the next step in the learning process (only the minimal amount of information that is needed to help them get there is provided, and this step is repeated each time it’s needed) (IP Module 4: Making Success Accessible) Non-verbal cue cards support students’ self-regulation, as they can monitor and control their progress as they work (Pozas & Schneider 2019)

- Making instructional practices that ensure all students meet at least the minimum standards and that more advanced students meet higher standards , which involves monitoring students’ learning process carefully (IP Module 4: Making Success Accessible; IP Module 5: Giving Inclusive Assessments) This type of approach to student assessment can be related to specifications grading, where students determine the grade they want and complete the modules that correspond to that grade, offering additional motivation to and reduced stress for students and additional flexibility and time-saving practices to instructors (Hall 2018)

- Making options that support student autonomy in being responsible for their learning process and choosing material to work on (e.g., students can choose tasks, project-based learning, portfolios, and/or station work, etc.) (IP Module 4: Making Success Accessible) This option, as well as the others, fits within a general Universal Design Learning framework , which is designed to improve learning for everyone using scientific insights about human learning

Hall, M (2018). “ What is Specifications Grading and Why Should You Consider Using It? ” The Innovator Instructor blog, John Hopkins University Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation.

Moallemi, R. (2023). “ The Relationship between Differentiated Instruction and Learner Levels of Engagement at University .” Journal of Research in Integrated Teaching and Learning (ahead of print).

Pham, H. (2011). “ Differentiated Instruction and the Need to Integrate Teaching and Practice .” Journal of College Teaching and Learning , 9(1), 13-20.

Pozas, M. & Schneider, C. (2019). " Shedding light into the convoluted terrain of differentiated instruction (DI): Proposal of a taxonomy of differentiated instruction in the heterogeneous classroom ." Open Education Studies , 1, 73–90.

Pozas, M., Letzel, V. and Schneider, C. (2020). " Teachers and differentiated instruction: exploring differentiation practices to address student diversity ." Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs , 20: 217-230.

Shareefa, M. et al. (2019). “ Differentiated Instruction: Definition and Challenging Factors Perceived by Teachers .” Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Special Education (ICSE 2019).

Tullis, J.G. & Goldstone, R.L. (2020). “ Why does peer instruction benefit student learning? ”, Cognitive Research 5 .

Turner, W.D., Solis, O.J., and Kincade, D.H. (2017). “ Differentiating Instruction for Large Classes in Higher Education ”, International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , 29(3), 490-500.

van Geel, M., Keuning, T., Frèrejean, J., Dolmans, D., van Merriënboer, J., & Visscher A.J. (2019). “Capturing the complexity of differentiated instruction”, School Effectiveness and School Improvement , 30:1, 51-67, DOI: 10.1080/09243453.2018.1539013

What Research Says About . . . / Differentiated Learning

What we know, what you can do, educators take note.

Researchers at the National Center on Accessing the General Curriculum define differentiated instruction asa process to approach teaching and learning for students of differing abilities in the same class. The intent is to maximize each student's growth and individual success by meeting each student where he or she is . . . rather than expecting students to modify themselves for the curriculum. (Hall, 2002)

- Focus on the essential ideas and skills of the content area, eliminating ancillary tasks and activities.

- Respond to individual student differences (such as learning style, prior knowledge, interests, and level of engagement).

- Group students flexibly by shared interest, topic, or ability.

- Integrate ongoing and meaningful assessments with instruction.

- Continually assess; reflect; and adjust content, process, and product to meet student needs.