What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

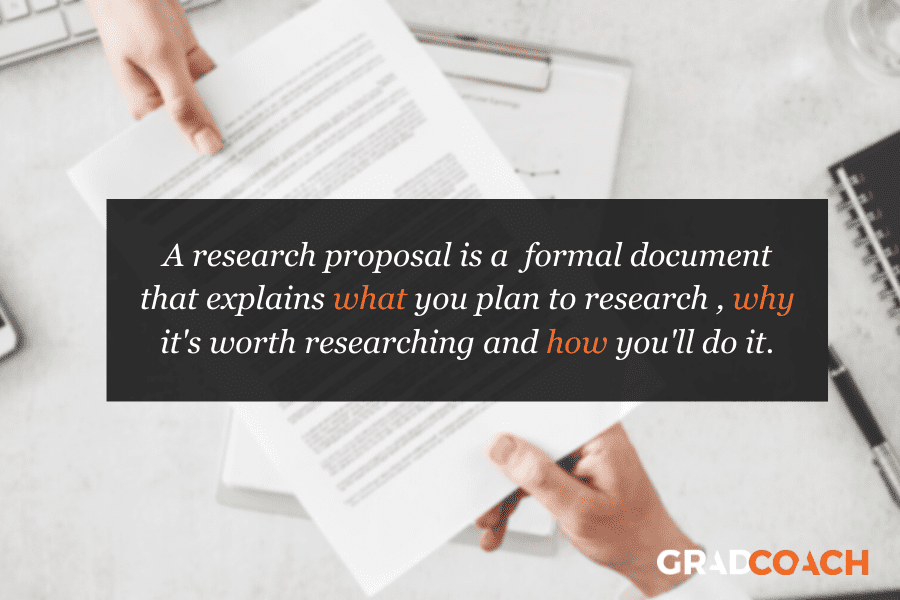

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on 13 June 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

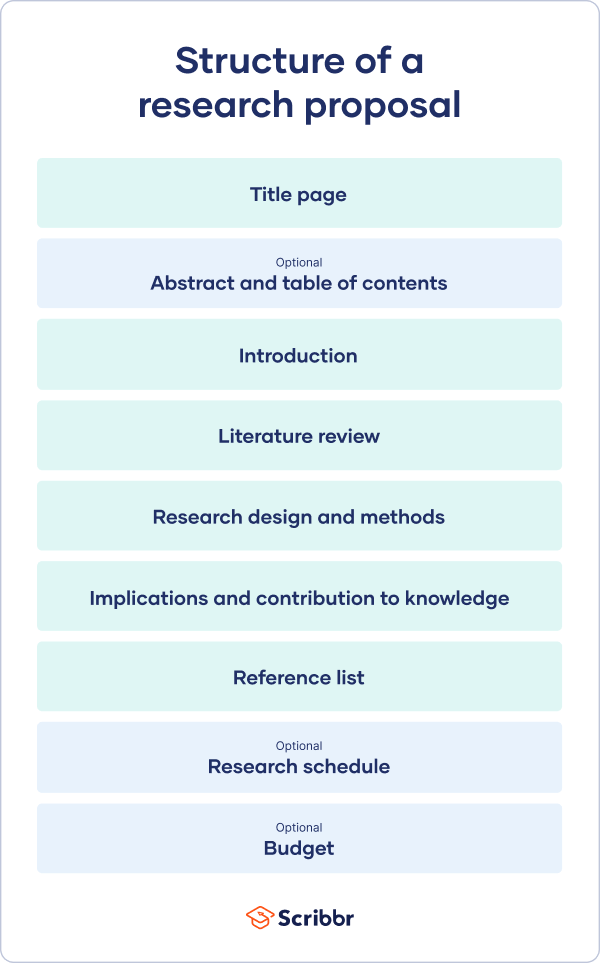

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organised and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, frequently asked questions.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: ‘A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management’

- Example research proposal #2: ‘ Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use’

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesise prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasise again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement.

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, June 13). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/research-proposal-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, how to write a results section | tips & examples.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal?

What is the purpose of a research proposal , how long should a research proposal be, what should be included in a research proposal, 1. the title page, 2. introduction, 3. literature review, 4. research design, 5. implications, 6. reference list, frequently asked questions about writing a research proposal, related articles.

If you’re in higher education, the term “research proposal” is something you’re likely to be familiar with. But what is it, exactly? You’ll normally come across the need to prepare a research proposal when you’re looking to secure Ph.D. funding.

When you’re trying to find someone to fund your Ph.D. research, a research proposal is essentially your “pitch.”

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research.

You’ll need to set out the issues that are central to the topic area and how you intend to address them with your research. To do this, you’ll need to give the following:

- an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls

- an overview of how much is currently known about the topic

- a literature review that covers the recent scholarly debate or conversation around the topic

➡️ What is a literature review? Learn more in our guide.

Essentially, you are trying to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into.

It is the opportunity for you to demonstrate that you have the aptitude for this level of research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas:

It also helps you to find the right supervisor to oversee your research. When you’re writing your research proposal, you should always have this in the back of your mind.

This is the document that potential supervisors will use in determining the legitimacy of your research and, consequently, whether they will invest in you or not. It is therefore incredibly important that you spend some time on getting it right.

Tip: While there may not always be length requirements for research proposals, you should strive to cover everything you need to in a concise way.

If your research proposal is for a bachelor’s or master’s degree, it may only be a few pages long. For a Ph.D., a proposal could be a pretty long document that spans a few dozen pages.

➡️ Research proposals are similar to grant proposals. Learn how to write a grant proposal in our guide.

When you’re writing your proposal, keep in mind its purpose and why you’re writing it. It, therefore, needs to clearly explain the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. You need to then explain what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

Generally, your structure should look something like this:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Research Design

- Implications

If you follow this structure, you’ll have a comprehensive and coherent proposal that looks and feels professional, without missing out on anything important. We’ll take a deep dive into each of these areas one by one next.

The title page might vary slightly per your area of study but, as a general point, your title page should contain the following:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- The name of your institution and your particular department

Tip: Keep in mind any departmental or institutional guidelines for a research proposal title page. Also, your supervisor may ask for specific details to be added to the page.

The introduction is crucial to your research proposal as it is your first opportunity to hook the reader in. A good introduction section will introduce your project and its relevance to the field of study.

You’ll want to use this space to demonstrate that you have carefully thought about how to present your project as interesting, original, and important research. A good place to start is by introducing the context of your research problem.

Think about answering these questions:

- What is it you want to research and why?

- How does this research relate to the respective field?

- How much is already known about this area?

- Who might find this research interesting?

- What are the key questions you aim to answer with your research?

- What will the findings of this project add to the topic area?

Your introduction aims to set yourself off on a great footing and illustrate to the reader that you are an expert in your field and that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge and theory.

The literature review section answers the question who else is talking about your proposed research topic.

You want to demonstrate that your research will contribute to conversations around the topic and that it will sit happily amongst experts in the field.

➡️ Read more about how to write a literature review .

There are lots of ways you can find relevant information for your literature review, including:

- Research relevant academic sources such as books and journals to find similar conversations around the topic.

- Read through abstracts and bibliographies of your academic sources to look for relevance and further additional resources without delving too deep into articles that are possibly not relevant to you.

- Watch out for heavily-cited works . This should help you to identify authoritative work that you need to read and document.

- Look for any research gaps , trends and patterns, common themes, debates, and contradictions.

- Consider any seminal studies on the topic area as it is likely anticipated that you will address these in your research proposal.

This is where you get down to the real meat of your research proposal. It should be a discussion about the overall approach you plan on taking, and the practical steps you’ll follow in answering the research questions you’ve posed.

So what should you discuss here? Some of the key things you will need to discuss at this point are:

- What form will your research take? Is it qualitative/quantitative/mixed? Will your research be primary or secondary?

- What sources will you use? Who or what will you be studying as part of your research.

- Document your research method. How are you practically going to carry out your research? What tools will you need? What procedures will you use?

- Any practicality issues you foresee. Do you think there will be any obstacles to your anticipated timescale? What resources will you require in carrying out your research?

Your research design should also discuss the potential implications of your research. For example, are you looking to confirm an existing theory or develop a new one?

If you intend to create a basis for further research, you should describe this here.

It is important to explain fully what you want the outcome of your research to look like and what you want to achieve by it. This will help those reading your research proposal to decide if it’s something the field needs and wants, and ultimately whether they will support you with it.

When you reach the end of your research proposal, you’ll have to compile a list of references for everything you’ve cited above. Ideally, you should keep track of everything from the beginning. Otherwise, this could be a mammoth and pretty laborious task to do.

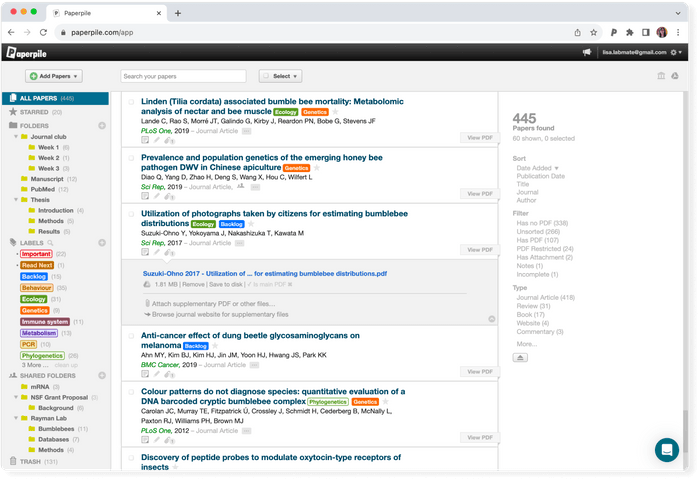

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to format and organize your citations. Paperpile allows you to organize and save your citations for later use and cite them in thousands of citation styles directly in Google Docs, Microsoft Word, or LaTeX.

Your project may also require you to have a timeline, depending on the budget you are requesting. If you need one, you should include it here and explain both the timeline and the budget you need, documenting what should be done at each stage of the research and how much of the budget this will use.

This is the final step, but not one to be missed. You should make sure that you edit and proofread your document so that you can be sure there are no mistakes.

A good idea is to have another person proofread the document for you so that you get a fresh pair of eyes on it. You can even have a professional proofreader do this for you.

This is an important document and you don’t want spelling or grammatical mistakes to get in the way of you and your reader.

➡️ Working on a research proposal for a thesis? Take a look at our guide on how to come up with a topic for your thesis .

A research proposal is a concise and coherent summary of your proposed research. Generally, your research proposal will have a title page, introduction, literature review section, a section about research design and explaining the implications of your research, and a reference list.

A good research proposal is concise and coherent. It has a clear purpose, clearly explains the relevance of your research and its context with other discussions on the topic. A good research proposal explains what approach you will take and why it is feasible.

You need a research proposal to persuade your institution that you and your project are worth investing their time and money into. It is your opportunity to demonstrate your aptitude for this level or research by showing that you can articulate complex ideas clearly, concisely, and critically.

A research proposal is essentially your "pitch" when you're trying to find someone to fund your PhD. It is a clear and concise summary of your proposed research. It gives an outline of the general area of study within which your research falls, it elaborates how much is currently known about the topic, and it highlights any recent debate or conversation around the topic by other academics.

The general answer is: as long as it needs to be to cover everything. The length of your research proposal depends on the requirements from the institution that you are applying to. Make sure to carefully read all the instructions given, and if this specific information is not provided, you can always ask.

Writing a Research Proposal

- First Online: 10 April 2022

Cite this chapter

- Fahimeh Tabatabaei 3 &

- Lobat Tayebi 3

791 Accesses

A research proposal is a roadmap that brings the researcher closer to the objectives, takes the research topic from a purely subjective mind, and manifests an objective plan. It shows us what steps we need to take to reach the objective, what questions we should answer, and how much time we need. It is a framework based on which you can perform your research in a well-organized and timely manner. In other words, by writing a research proposal, you get a map that shows the direction to the destination (answering the research question). If the proposal is poorly prepared, after spending a lot of energy and money, you may realize that the result of the research has nothing to do with the initial objective, and the study may end up nowhere. Therefore, writing the proposal shows that the researcher is aware of the proper research and can justify the significance of his/her idea.

- Research proposal

- Research strategy

- Research methodology

- Research design

- Problem formulation

- Sample size

- Random allocation

- Specific aims

- Review grants

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

A. Gholipour, E.Y. Lee, S.K. Warfield, The anatomy and art of writing a successful grant application: A practical step-by-step approach. Pediatr. Radiol. 44 (12), 1512–1517 (2014)

Article Google Scholar

L.S. Marshall, Research commentary: Grant writing: Part I first things first …. J. Radiol. Nurs. 31 (4), 154–155 (2012)

E.K. Proctor, B.J. Powell, A.A. Baumann, A.M. Hamilton, R.L. Santens, Writing implementation research grant proposals: Ten key ingredients. Implement. Sci. 7 (1), 96 (2012)

K.C. Chung, M.J. Shauver, Fundamental principles of writing a successful grant proposal. J. Hand Surg. Am. 33 (4), 566–572 (2008)

A.A. Monte, A.M. Libby, Introduction to the specific aims page of a grant proposal. Kline JA, editor. Acad. Emerg. Med. 25 (9), 1042–1047 (2018)

P. Kan, M.R. Levitt, W.J. Mack, R.M. Starke, K.N. Sheth, F.C. Albuquerque, et al., National Institutes of Health grant opportunities for the neurointerventionalist: Preparation and choosing the right mechanism. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 13 (3), 287–289 (2021)

A.M. Goldstein, S. Balaji, A.A. Ghaferi, A. Gosain, M. Maggard-Gibbons, B. Zuckerbraun, et al., An algorithmic approach to an impactful specific aims page. Surgery 169 (4), 816–820 (2021)

S. Engberg, D.Z. Bliss, Writing a grant proposal—Part 1. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 32 (3), 157–162 (2005)

D.Z. Bliss, K. Savik, Writing a grant proposal—Part 2. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 32 (4), 226–229 (2005)

D.Z. Bliss, Writing a grant proposal—Part 6. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 32 (6), 365–367 (2005)

J.C. Liu, M.A. Pynnonen, M. St John, E.L. Rosenthal, M.E. Couch, C.E. Schmalbach, Grant-writing pearls and pitfalls. Otolaryngol. Neck. Surg. 154 (2), 226–232 (2016)

R.J. Santen, E.J. Barrett, H.M. Siragy, L.S. Farhi, L. Fishbein, R.M. Carey, The jewel in the crown: Specific aims section of investigator-initiated grant proposals. J. Endocr. Soc. 1 (9), 1194–1202 (2017)

O.J. Arthurs, Think it through first: Questions to consider in writing a successful grant application. Pediatr. Radiol. 44 (12), 1507–1511 (2014)

M. Monavarian, Basics of scientific and technical writing. MRS Bull. 46 (3), 284–286 (2021)

Additional Resources

https://grants.nih.gov

https://grants.nih.gov/grants/oer.htm

https://www.ninr.nih.gov

https://www.niaid.nih.gov

http://www.grantcentral.com

http://www.saem.org/research

http://www.cfda.gov

http://www.ahrq.gov

http://www.nsf/gov

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Dentistry, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Fahimeh Tabatabaei & Lobat Tayebi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Tabatabaei, F., Tayebi, L. (2022). Writing a Research Proposal. In: Research Methods in Dentistry. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98028-3_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98028-3_4

Published : 10 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-98027-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-98028-3

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What is a research proposal?

A research proposal is a type of text which maps out a proposed central research problem or question and a suggested approach to its investigation.

In many universities, including RMIT, the research proposal is a formal requirement. It is central to achieving your first milestone: your Confirmation of Candidature. The research proposal is useful for both you and the University: it gives you the opportunity to get valuable feedback about your intended research aims, objectives and design. It also confirms that your proposed research is worth doing, which puts you on track for a successful candidature supported by your School and the University.

Although there may be specific School or disciplinary requirements that you need to be aware of, all research proposals address the following central themes:

- what you propose to research

- why the topic needs to be researched

- how you plan to research it.

Purpose and audience

Before venturing into writing a research purposal, it is important to think about the purpose and audience of this type of text. Spend a moment or two to reflect on what these might be.

What do you think is the purpose of your research proposal and who is your audience?

The purpose of your research proposal is:

1. To allow experienced researchers (your supervisors and their peers) to assess whether

- the research question or problem is viable (that is, answers or solutions are possible)

- the research is worth doing in terms of its contribution to the field of study and benefits to stakeholders

- the scope is appropriate to the degree (Masters or PhD)

- you’ve understood the relevant key literature and identified the gap for your research

- you’ve chosen an appropriate methodological approach.

2. To help you clarify and focus on what you want to do, why you want to do it, and how you’ll do it. The research proposal helps you position yourself as a researcher in your field. It will also allow you to:

- systematically think through your proposed research, argue for its significance and identify the scope

- show a critical understanding of the scholarly field around your proposed research

- show the gap in the literature that your research will address

- justify your proposed research design

- identify all tasks that need to be done through a realistic timetable

- anticipate potential problems

- hone organisational skills that you will need for your research

- become familiar with relevant search engines and databases

- develop skills in research writing.

The main audience for your research proposal is your reviewers. Universities usually assign a panel of reviewers to which you need to submit your research proposal. Often this is within the first year of study for PhD candidates, and within the first six months for Masters by Research candidates.

Your reviewers may have a strong disciplinary understanding of the area of your proposed research, but depending on your specialisation, they may not. It is therefore important to create a clear context, rationale and framework for your proposed research. Limit jargon and specialist terminology so that non-specialists can comprehend it. You need to convince the reviewers that your proposed research is worth doing and that you will be able to effectively ‘interrogate’ your research questions or address the research problems through your chosen research design.

Your review panel will expect you to demonstrate:

- a clearly defined and feasible research project

- a clearly explained rationale for your research

- evidence that your research will make an original contribution through a critical review of the literature

- written skills appropriate to graduate research study.

Research and Writing Skills for Academic and Graduate Researchers Copyright © 2022 by RMIT University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Anaesth

- v.60(9); 2016 Sep

How to write a research proposal?

Department of Anaesthesiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Devika Rani Duggappa

Writing the proposal of a research work in the present era is a challenging task due to the constantly evolving trends in the qualitative research design and the need to incorporate medical advances into the methodology. The proposal is a detailed plan or ‘blueprint’ for the intended study, and once it is completed, the research project should flow smoothly. Even today, many of the proposals at post-graduate evaluation committees and application proposals for funding are substandard. A search was conducted with keywords such as research proposal, writing proposal and qualitative using search engines, namely, PubMed and Google Scholar, and an attempt has been made to provide broad guidelines for writing a scientifically appropriate research proposal.

INTRODUCTION

A clean, well-thought-out proposal forms the backbone for the research itself and hence becomes the most important step in the process of conduct of research.[ 1 ] The objective of preparing a research proposal would be to obtain approvals from various committees including ethics committee [details under ‘Research methodology II’ section [ Table 1 ] in this issue of IJA) and to request for grants. However, there are very few universally accepted guidelines for preparation of a good quality research proposal. A search was performed with keywords such as research proposal, funding, qualitative and writing proposals using search engines, namely, PubMed, Google Scholar and Scopus.

Five ‘C’s while writing a literature review

BASIC REQUIREMENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

A proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new paradigm will it add to the literature, while specifying the question that the research will answer, establishing its significance, and the implications of the answer.[ 2 ] The proposal must be capable of convincing the evaluation committee about the credibility, achievability, practicality and reproducibility (repeatability) of the research design.[ 3 ] Four categories of audience with different expectations may be present in the evaluation committees, namely academic colleagues, policy-makers, practitioners and lay audiences who evaluate the research proposal. Tips for preparation of a good research proposal include; ‘be practical, be persuasive, make broader links, aim for crystal clarity and plan before you write’. A researcher must be balanced, with a realistic understanding of what can be achieved. Being persuasive implies that researcher must be able to convince other researchers, research funding agencies, educational institutions and supervisors that the research is worth getting approval. The aim of the researcher should be clearly stated in simple language that describes the research in a way that non-specialists can comprehend, without use of jargons. The proposal must not only demonstrate that it is based on an intelligent understanding of the existing literature but also show that the writer has thought about the time needed to conduct each stage of the research.[ 4 , 5 ]

CONTENTS OF A RESEARCH PROPOSAL

The contents or formats of a research proposal vary depending on the requirements of evaluation committee and are generally provided by the evaluation committee or the institution.

In general, a cover page should contain the (i) title of the proposal, (ii) name and affiliation of the researcher (principal investigator) and co-investigators, (iii) institutional affiliation (degree of the investigator and the name of institution where the study will be performed), details of contact such as phone numbers, E-mail id's and lines for signatures of investigators.

The main contents of the proposal may be presented under the following headings: (i) introduction, (ii) review of literature, (iii) aims and objectives, (iv) research design and methods, (v) ethical considerations, (vi) budget, (vii) appendices and (viii) citations.[ 4 ]

Introduction

It is also sometimes termed as ‘need for study’ or ‘abstract’. Introduction is an initial pitch of an idea; it sets the scene and puts the research in context.[ 6 ] The introduction should be designed to create interest in the reader about the topic and proposal. It should convey to the reader, what you want to do, what necessitates the study and your passion for the topic.[ 7 ] Some questions that can be used to assess the significance of the study are: (i) Who has an interest in the domain of inquiry? (ii) What do we already know about the topic? (iii) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (iv) How will this research add to knowledge, practice and policy in this area? Some of the evaluation committees, expect the last two questions, elaborated under a separate heading of ‘background and significance’.[ 8 ] Introduction should also contain the hypothesis behind the research design. If hypothesis cannot be constructed, the line of inquiry to be used in the research must be indicated.

Review of literature

It refers to all sources of scientific evidence pertaining to the topic in interest. In the present era of digitalisation and easy accessibility, there is an enormous amount of relevant data available, making it a challenge for the researcher to include all of it in his/her review.[ 9 ] It is crucial to structure this section intelligently so that the reader can grasp the argument related to your study in relation to that of other researchers, while still demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. It is preferable to summarise each article in a paragraph, highlighting the details pertinent to the topic of interest. The progression of review can move from the more general to the more focused studies, or a historical progression can be used to develop the story, without making it exhaustive.[ 1 ] Literature should include supporting data, disagreements and controversies. Five ‘C's may be kept in mind while writing a literature review[ 10 ] [ Table 1 ].

Aims and objectives

The research purpose (or goal or aim) gives a broad indication of what the researcher wishes to achieve in the research. The hypothesis to be tested can be the aim of the study. The objectives related to parameters or tools used to achieve the aim are generally categorised as primary and secondary objectives.

Research design and method

The objective here is to convince the reader that the overall research design and methods of analysis will correctly address the research problem and to impress upon the reader that the methodology/sources chosen are appropriate for the specific topic. It should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

In this section, the methods and sources used to conduct the research must be discussed, including specific references to sites, databases, key texts or authors that will be indispensable to the project. There should be specific mention about the methodological approaches to be undertaken to gather information, about the techniques to be used to analyse it and about the tests of external validity to which researcher is committed.[ 10 , 11 ]

The components of this section include the following:[ 4 ]

Population and sample

Population refers to all the elements (individuals, objects or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe,[ 12 ] and sample refers to subset of population which meets the inclusion criteria for enrolment into the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined. The details pertaining to sample size are discussed in the article “Sample size calculation: Basic priniciples” published in this issue of IJA.

Data collection

The researcher is expected to give a detailed account of the methodology adopted for collection of data, which include the time frame required for the research. The methodology should be tested for its validity and ensure that, in pursuit of achieving the results, the participant's life is not jeopardised. The author should anticipate and acknowledge any potential barrier and pitfall in carrying out the research design and explain plans to address them, thereby avoiding lacunae due to incomplete data collection. If the researcher is planning to acquire data through interviews or questionnaires, copy of the questions used for the same should be attached as an annexure with the proposal.

Rigor (soundness of the research)

This addresses the strength of the research with respect to its neutrality, consistency and applicability. Rigor must be reflected throughout the proposal.

It refers to the robustness of a research method against bias. The author should convey the measures taken to avoid bias, viz. blinding and randomisation, in an elaborate way, thus ensuring that the result obtained from the adopted method is purely as chance and not influenced by other confounding variables.

Consistency

Consistency considers whether the findings will be consistent if the inquiry was replicated with the same participants and in a similar context. This can be achieved by adopting standard and universally accepted methods and scales.

Applicability

Applicability refers to the degree to which the findings can be applied to different contexts and groups.[ 13 ]

Data analysis

This section deals with the reduction and reconstruction of data and its analysis including sample size calculation. The researcher is expected to explain the steps adopted for coding and sorting the data obtained. Various tests to be used to analyse the data for its robustness, significance should be clearly stated. Author should also mention the names of statistician and suitable software which will be used in due course of data analysis and their contribution to data analysis and sample calculation.[ 9 ]

Ethical considerations

Medical research introduces special moral and ethical problems that are not usually encountered by other researchers during data collection, and hence, the researcher should take special care in ensuring that ethical standards are met. Ethical considerations refer to the protection of the participants' rights (right to self-determination, right to privacy, right to autonomy and confidentiality, right to fair treatment and right to protection from discomfort and harm), obtaining informed consent and the institutional review process (ethical approval). The researcher needs to provide adequate information on each of these aspects.

Informed consent needs to be obtained from the participants (details discussed in further chapters), as well as the research site and the relevant authorities.

When the researcher prepares a research budget, he/she should predict and cost all aspects of the research and then add an additional allowance for unpredictable disasters, delays and rising costs. All items in the budget should be justified.