- Jump to menu

- Student Home

- Accept your offer

- How to enrol

- Student ID card

- Set up your IT

- Orientation Week

- Fees & payment

- Academic calendar

- Special consideration

- Transcripts

- The Nucleus: Student Hub

- Referencing

- Essay writing

- Learning abroad & exchange

- Professional development & UNSW Advantage

- Employability

- Financial assistance

- International students

- Equitable learning

- Postgraduate research

- Health Service

- Events & activities

- Emergencies

- Volunteering

- Clubs and societies

- Accommodation

- Health services

- Sport and gym

- Arc student organisation

- Security on campus

- Maps of campus

- Careers portal

- Change password

How to Write a Thesis Introduction

What types of information should you include in your introduction .

In the introduction of your thesis, you’ll be trying to do three main things, which are called Moves :

- Move 1 establish your territory (say what the topic is about)

- Move 2 establish a niche (show why there needs to be further research on your topic)

- Move 3 introduce the current research (make hypotheses; state the research questions)

Each Move has a number of stages. Depending on what you need to say in your introduction, you might use one or more stages. Table 1 provides you with a list of the most commonly occurring stages of introductions in Honours theses (colour-coded to show the Moves ). You will also find examples of Introductions, divided into stages with sample sentence extracts. Once you’ve looked at Examples 1 and 2, try the exercise that follows.

Most thesis introductions include SOME (but not all) of the stages listed below. There are variations between different Schools and between different theses, depending on the purpose of the thesis.

Stages in a thesis introduction

- state the general topic and give some background

- provide a review of the literature related to the topic

- define the terms and scope of the topic

- outline the current situation

- evaluate the current situation (advantages/ disadvantages) and identify the gap

- identify the importance of the proposed research

- state the research problem/ questions

- state the research aims and/or research objectives

- state the hypotheses

- outline the order of information in the thesis

- outline the methodology

Example 1: Evaluation of Boron Solid Source Diffusion for High-Efficiency Silicon Solar Cells (School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering)

Example 2: Methods for Measuring Hepatitis C Viral Complexity (School of Biotechnology and Biological Sciences)

Note: this introduction includes the literature review.

Now that you have read example 1 and 2, what are the differences?

Example 3: The IMO Severe-Weather Criterion Applied to High-Speed Monohulls (School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering)

Example 4: The Steiner Tree Problem (School of Computer Science and Engineering)

Introduction exercise

Example 5.1 (extract 1): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.2 (extract 2): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.3

Example 5.4 (extract 4): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.5 (extract 5): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Example 5.6 (extract 6): The effects of Fluoride on the reproduction of three native Australian plant Species (School of Geography)

Well, firstly, there are many choices that you can make. You will notice that there are variations not only between the different Schools in your faculty, but also between individual theses, depending on the type of information that is being communicated. However, there are a few elements that a good Introduction should include, at the very minimum:

- Either Statement of general topic Or Background information about the topic;

- Either Identification of disadvantages of current situation Or Identification of the gap in current research;

- Identification of importance of proposed research

- Either Statement of aims Or Statement of objectives

- An Outline of the order of information in the thesis

Engineering & science

- Report writing

- Technical writing

- Writing lab reports

- Introductions

- Literature review

- Writing up results

- Discussions

- Conclusions

- Writing tools

- Case study report in (engineering)

- ^ More support

Study Hacks Workshops | All the hacks you need! 7 Feb – 10 Apr 2024

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a good thesis introduction

1. Identify your readership

2. hook the reader and grab their attention, 3. provide relevant background, 4. give the reader a sense of what the paper is about, 5. preview key points and lead into your thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a good thesis introduction, related articles.

Many people struggle to write a thesis introduction. Much of your research prep should be done and you should be ready to start your introduction. But often, it’s not clear what needs to be included in a thesis introduction. If you feel stuck at this point not knowing how to start, this guide can help.

Tip: If you’re really struggling to write your thesis intro, consider putting in a placeholder until you write more of the body of your thesis. Then, come back to your intro once you have a stronger sense of the overall content of your thesis.

A good introduction draws readers in while providing the setup for the entire project. There is no single way to write an introduction that will always work for every topic , but the points below can act as a guide. These points can help you write a good thesis introduction.

Before even starting with your first sentence, consider who your readers are. Most likely, your readers will be the professors who are advising you on your thesis.

You should also consider readers of your thesis who are not specialists in your field. Writing with them in your mind will help you to be as clear as possible; this will make your thesis more understandable and enjoyable overall.

Tip: Always strive to be clear, correct, concrete, and concise in your writing.

The first sentence of the thesis is crucial. Looking back at your own research, think about how other writers may have hooked you.

It is common to start with a question or quotation, but these types of hooks are often overused. The best way to start your introduction is with a sentence that is broad and interesting and that seamlessly transitions into your argument.

Once again, consider your audience and how much background information they need to understand your approach. You can start by making a list of what is interesting about your topic:

- Are there any current events or controversies associated with your topic that might be interesting for your introduction?

- What kinds of background information might be useful for a reader to understand right away?

- Are there historical anecdotes or other situations that uniquely illustrate an important aspect of your argument?

A good introduction also needs to contain enough background information to allow the reader to understand the thesis statement and arguments. The amount of background information required will depend on the topic .

There should be enough background information so you don't have to spend too much time with it in the body of the thesis, but not so much that it becomes uninteresting.

Tip: Strike a balance between background information that is too broad or too specific.

Let the reader know what the purpose of the study is. Make sure to include the following points:

- Briefly describe the motivation behind your research.

- Describe the topic and scope of your research.

- Explain the practical relevance of your research.

- Explain the scholarly consensus related to your topic: briefly explain the most important articles and how they are related to your research.

At the end of your introduction, you should lead into your thesis statement by briefly bringing up a few of your main supporting details and by previewing what will be covered in the main part of the thesis. You’ll want to highlight the overall structure of your thesis so that readers will have a sense of what they will encounter as they read.

A good introduction draws readers in while providing the setup for the entire project. There is no single way to write an introduction that will always work for every topic, but these tips will help you write a great introduction:

- Identify your readership.

- Grab the reader's attention.

- Provide relevant background.

- Preview key points and lead into the thesis statement.

A good introduction needs to contain enough background information, and let the reader know what the purpose of the study is. Make sure to include the following points:

- Briefly describe the motivation for your research.

The length of the introduction will depend on the length of the whole thesis. Usually, an introduction makes up roughly 10 per cent of the total word count.

The best way to start your introduction is with a sentence that is broad and interesting and that seamlessly transitions into your argument. Consider the audience, then think of something that would grab their attention.

In Open Access: Theses and Dissertations you can find thousands of recent works. Take a look at any of the theses or dissertations for real-life examples of introductions that were already approved.

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Introduction

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Study Skills

- Exam Skills

- How to Write a Research Proposal

- Ethical Issues in Research

- Dissertation: The Introduction

- Researching and Writing a Literature Review

- Writing your Methodology

- Dissertation: Results and Discussion

- Dissertation: Conclusions and Extras

Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Writing a Dissertation: The Introduction

The introduction to your dissertation or thesis may well be the last part that you complete, excepting perhaps the abstract. However, it should not be the last part that you think about.

You should write a draft of your introduction very early on, perhaps as early as when you submit your research proposal , to set out a broad outline of your ideas, why you want to study this area, and what you hope to explore and/or establish.

You can, and should, update your introduction several times as your ideas develop. Keeping the introduction in mind will help you to ensure that your research stays on track.

The introduction provides the rationale for your dissertation, thesis or other research project: what you are trying to answer and why it is important to do this research.

Your introduction should contain a clear statement of the research question and the aims of the research (closely related to the question).

It should also introduce and briefly review the literature on your topic to show what is already known and explain the theoretical framework. If there are theoretical debates in the literature, then the introduction is a good place for the researcher to give his or her own perspective in conjunction with the literature review section of the dissertation.

The introduction should also indicate how your piece of research will contribute to the theoretical understanding of the topic.

Drawing on your Research Proposal

The introduction to your dissertation or thesis will probably draw heavily on your research proposal.

If you haven't already written a research proposal see our page Writing a Research Proposal for some ideas.

The introduction needs to set the scene for the later work and give a broad idea of the arguments and/or research that preceded yours. It should give some idea of why you chose to study this area, giving a flavour of the literature, and what you hoped to find out.

Don’t include too many citations in your introduction: this is your summary of why you want to study this area, and what questions you hope to address. Any citations are only to set the context, and you should leave the bulk of the literature for a later section.

Unlike your research proposal, however, you have now completed the work. This means that your introduction can be much clearer about what exactly you chose to investigate and the precise scope of your work.

Remember , whenever you actually write it, that, for the reader, the introduction is the start of the journey through your work. Although you can give a flavour of the outcomes of your research, you should not include any detailed results or conclusions.

Some good ideas for making your introduction strong include:

- An interesting opening sentence that will hold the attention of your reader.

- Don’t try to say everything in the introduction, but do outline the broad thrust of your work and argument.

- Make sure that you don’t promise anything that can’t be delivered later.

- Keep the language straightforward. Although you should do this throughout, it is especially important for the introduction.

Your introduction is the reader’s ‘door’ into your thesis or dissertation. It therefore needs to make sense to the non-expert. Ask a friend to read it for you, and see if they can understand it easily.

At the end of the introduction, it is also usual to set out an outline of the rest of the dissertation.

This can be as simple as ‘ Chapter 2 discusses my chosen methodology, Chapter 3 sets out my results, and Chapter 4 discusses the results and draws conclusions ’.

However, if your thesis is ordered by themes, then a more complex outline may be necessary.

Drafting and Redrafting

As with any other piece of writing, redrafting and editing will improve your text.

This is especially important for the introduction because it needs to hold your reader’s attention and lead them into your research.

The best way to ensure that you can do this is to give yourself enough time to write a really good introduction, including several redrafts.

Do not view the introduction as a last minute job.

Continue to: Writing a Literature Review Writing the Methodology

See also: Dissertation: Results and Discussion Dissertation: Conclusions and Extra Sections Academic Referencing | Research Methods

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

06 Essential Steps for Introduction Section of Dissertation or Thesis

Introduction

Stating the research problem or research question, brief overview of the structure of your dissertation, 1. starting with a compelling opening, 2. providing background information, 3. clearly stating the research problem, 4. stating the research objectives, 5. highlighting the research significance, 6. outlining the dissertation structure, avoiding unnecessary jargon or technical details, seeking feedback and revising the introduction multiple times, common academic phrases that can be used in the introduction section.

Are you on the journey of completing your PhD or Post Graduate dissertation? The introduction section plays a vital role in setting the stage for your research and capturing the reader’s attention from the very beginning. A well-crafted introduction is a gateway to showcasing the significance and value of your work.

In this blog post, we will guide you through the essential elements and expert tips to create an engaging and impactful introduction for your dissertation or thesis.

This comprehensive guide will equip you with the tools to write an introduction that stands out. From capturing the reader’s interest with a compelling opening to defining the research problem, stating objectives, and highlighting the research significance, we’ve got you covered.

Not only will you discover practical strategies for crafting an effective introduction, but you’ll also learn how to keep it concise, avoid jargon, and seek valuable feedback. Additionally, we’ll provide domain-specific examples to illustrate each point and help you better understand the application of these techniques.

By mastering the art of writing an engaging introduction, you’ll be able to captivate your readers, establish the context of your research, and demonstrate the value of your study. So, let’s dive in and unlock the secrets to crafting an introduction that sets the foundation for a remarkable PhD dissertation.

If you are in paucity of time, not confident of your writing skills and in a hurry to complete the writing task then you can think of hiring a research consultant that solves all your problems. Please visit my article on Hiring a Research consultant for your PhD tasks for further details.

Purpose of the Introduction

The introduction should introduce the specific topic of your research and provide the necessary background information. For example: “In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative technology with applications in various domains. This study focuses on improving the accuracy of image recognition algorithms in computer vision, a crucial area within AI research.”

Clearly articulating the research problem or research question is essential. Here’s an example: “The objective of this study is to develop a more efficient algorithm for large-scale graph analysis, addressing the challenge of processing massive networks in real-time.”

It is important to state the specific objectives or goals of your research. Here’s an example: “The primary objectives of this research are to design and implement a secure communication protocol for Internet of Things (IoT) devices, evaluate its performance under different network conditions, and assess its resistance to potential cyber-attacks.”

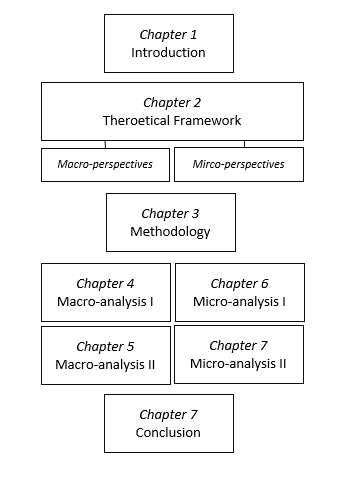

It is helpful to provide a brief overview of the structure of your dissertation, indicating the main sections or chapters. Here’s an example: “This dissertation consists of six chapters. Chapter 1 presents the introduction, research problem, objectives, and methodology. Chapter 2 provides a comprehensive literature review of the existing algorithms for sentiment analysis. Chapter 3 details the proposed algorithm for sentiment classification. Chapter 4 presents the experimental setup and results. Chapter 5 discusses the findings and implications. Finally, Chapter 6 concludes the dissertation with recommendations for future research.”

Remember to adapt the examples to your specific research topic and ensure they accurately reflect the purpose of your introduction. By introducing the topic, stating the research problem, outlining the objectives, and providing an overview of the dissertation structure, you will establish the necessary foundation for your research.

Crafting an Effective Introduction in 06 Steps

By starting with a compelling opening, providing background information, clearly stating the research problem and objectives, highlighting the research significance, and outlining the dissertation structure, you will craft an effective introduction.

Starting with a compelling opening can capture the reader’s attention. Here are some examples:

- Anecdote: “Imagine a scenario where autonomous vehicles navigate through busy city streets, making split-second decisions to ensure passenger safety and optimize traffic flow.”

- Question: “Have you ever wondered how social media platforms use recommendation algorithms to personalize your news feed based on your interests and preferences?”

- Fact: “In 2020, the global cybersecurity market reached a value of $167.13 billion, highlighting the increasing need for robust and reliable security solutions in the digital age.”

Providing background information involves discussing existing literature, theories, and concepts. Here’s an example: “Previous studies in the field of natural language processing have focused on sentiment analysis, aiming to classify text into positive, negative, or neutral sentiments. However, current approaches face challenges in accurately capturing the contextual nuances and sarcasm often found in social media data.”

Clearly defining the research problem is crucial. Here’s an example: “The research problem addressed in this study is the efficient scheduling and resource allocation for cloud-based data-intensive applications, considering the dynamic nature of workloads and the varying availability of cloud resources.”

Presenting specific objectives is important in computer science. Here’s an example: “The primary objectives of this research are to develop an energy-efficient routing protocol for wireless sensor networks, investigate the impact of different routing metrics on network performance, and propose adaptive algorithms for dynamic topology changes.”

Explaining the importance and relevance of your research is essential. Here’s an example: “This research on blockchain technology has significant implications for enhancing data security, ensuring transparent and immutable transactions, and revolutionizing various sectors, including finance, supply chain management, and healthcare.”

Providing a brief overview of the main sections or chapters of your dissertation helps the reader understand the organization. Here’s an example: “This dissertation consists of five chapters. Chapter 1 introduces the research problem, objectives, and methodology. Chapter 2 provides a comprehensive literature review. Chapter 3 presents the proposed algorithm and its implementation. Chapter 4 discusses the experimental results and analysis. Finally, Chapter 5 concludes the dissertation, summarizing the findings and suggesting future research directions.”

Remember to tailor these examples to your specific research topic and ensure they align with your own introduction.

Tips for Writing a Strong Introduction

It’s essential to keep the introduction concise and focused on the main points. Avoid going into excessive detail or including unnecessary information. Here’s an example: “To achieve efficient data processing in distributed systems, this study focuses on developing a parallel algorithm for sorting large-scale datasets, aiming to reduce the computational time and improve overall system performance.”

While writing the introduction, it’s crucial to communicate your ideas clearly without overwhelming the reader with technical terms. Here’s an example: “This study investigates the usability of natural language interfaces for human-robot interaction, exploring the potential for seamless and intuitive communication between users and autonomous robotic systems.”

It’s important to seek feedback from your advisor or peers and revise your introduction based on their suggestions. .

Remember to adapt these examples to your specific research topic and ensure they align with your writing style. By keeping the introduction concise and focused, avoiding unnecessary jargon, and seeking feedback while revising multiple times, you will be able to write a strong introduction in any domain of research.

Here are some common academic phrases that can be used in the introduction section . I have included a table with examples to illustrate how these phrases might be used:

Crafting a well-crafted introduction is paramount when it comes to writing a PhD or Post Graduate dissertation. The introduction serves as the gateway to your research, setting the stage for what follows and capturing the reader’s attention. By following the outlined guidelines and tips, you can create an introduction that engages the reader, establishes the context, and highlights the significance of your research.

Upcoming Events

- Visit the Upcoming International Conferences at Exotic Travel Destinations with Travel Plan

- Visit for Research Internships Worldwide

Recent Posts

- Do Review Papers Count for the Award of a PhD Degree?

- Vinay Kabadi, University of Melbourne, Interview on Award-Winning Research

- Do You Need Publications for a PhD Application? The Essential Guide for Applicants

- Research Internships @ Finland

- A Stepwise Guide to Update/Reissue/Modify a Patent

- All Blog Posts

- Research Career

- Research Conference

- Research Internship

- Research Journal

- Research Tools

- Uncategorized

- Research Conferences

- Research Journals

- Research Grants

- Internships

- Research Internships

- Email Templates

- Conferences

- Blog Partners

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Research Voyage

Design by ThemesDNA.com

How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

The thesis introduction, usually chapter 1, is one of the most important chapters of a thesis. It sets the scene. It previews key arguments and findings. And it helps the reader to understand the structure of the thesis. In short, a lot is riding on this first chapter. With the following tips, you can write a powerful thesis introduction.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

Elements of a fantastic thesis introduction

Open with a (personal) story, begin with a problem, define a clear research gap, describe the scientific relevance of the thesis, describe the societal relevance of the thesis, write down the thesis’ core claim in 1-2 sentences, support your argument with sufficient evidence, consider possible objections, address the empirical research context, give a taste of the thesis’ empirical analysis, hint at the practical implications of the research, provide a reading guide, briefly summarise all chapters to come, design a figure illustrating the thesis structure.

An introductory chapter plays an integral part in every thesis. The first chapter has to include quite a lot of information to contextualise the research. At the same time, a good thesis introduction is not too long, but clear and to the point.

A powerful thesis introduction does the following:

- It captures the reader’s attention.

- It presents a clear research gap and emphasises the thesis’ relevance.

- It provides a compelling argument.

- It previews the research findings.

- It explains the structure of the thesis.

In addition, a powerful thesis introduction is well-written, logically structured, and free of grammar and spelling errors. Reputable thesis editors can elevate the quality of your introduction to the next level. If you are in search of a trustworthy thesis or dissertation editor who upholds high-quality standards and offers efficient turnaround times, I recommend the professional thesis and dissertation editing service provided by Editage .

This list can feel quite overwhelming. However, with some easy tips and tricks, you can accomplish all these goals in your thesis introduction. (And if you struggle with finding the right wording, have a look at academic key phrases for introductions .)

Ways to capture the reader’s attention

A powerful thesis introduction should spark the reader’s interest on the first pages. A reader should be enticed to continue reading! There are three common ways to capture the reader’s attention.

An established way to capture the reader’s attention in a thesis introduction is by starting with a story. Regardless of how abstract and ‘scientific’ the actual thesis content is, it can be useful to ease the reader into the topic with a short story.

This story can be, for instance, based on one of your study participants. It can also be a very personal account of one of your own experiences, which drew you to study the thesis topic in the first place.

Start by providing data or statistics

Data and statistics are another established way to immediately draw in your reader. Especially surprising or shocking numbers can highlight the importance of a thesis topic in the first few sentences!

So if your thesis topic lends itself to being kick-started with data or statistics, you are in for a quick and easy way to write a memorable thesis introduction.

The third established way to capture the reader’s attention is by starting with the problem that underlies your thesis. It is advisable to keep the problem simple. A few sentences at the start of the chapter should suffice.

Usually, at a later stage in the introductory chapter, it is common to go more in-depth, describing the research problem (and its scientific and societal relevance) in more detail.

You may also like: Minimalist writing for a better thesis

Emphasising the thesis’ relevance

A good thesis is a relevant thesis. No one wants to read about a concept that has already been explored hundreds of times, or that no one cares about.

Of course, a thesis heavily relies on the work of other scholars. However, each thesis is – and should be – unique. If you want to write a fantastic thesis introduction, your job is to point out this uniqueness!

In academic research, a research gap signifies a research area or research question that has not been explored yet, that has been insufficiently explored, or whose insights and findings are outdated.

Every thesis needs a crystal-clear research gap. Spell it out instead of letting your reader figure out why your thesis is relevant.

* This example has been taken from an actual academic paper on toxic behaviour in online games: Liu, J. and Agur, C. (2022). “After All, They Don’t Know Me” Exploring the Psychological Mechanisms of Toxic Behavior in Online Games. Games and Culture 1–24, DOI: 10.1177/15554120221115397

The scientific relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your work in terms of advancing theoretical insights on a topic. You can think of this part as your contribution to the (international) academic literature.

Scientific relevance comes in different forms. For instance, you can critically assess a prominent theory explaining a specific phenomenon. Maybe something is missing? Or you can develop a novel framework that combines different frameworks used by other scholars. Or you can draw attention to the context-specific nature of a phenomenon that is discussed in the international literature.

The societal relevance of a thesis highlights the importance of your research in more practical terms. You can think of this part as your contribution beyond theoretical insights and academic publications.

Why are your insights useful? Who can benefit from your insights? How can your insights improve existing practices?

Formulating a compelling argument

Arguments are sets of reasons supporting an idea, which – in academia – often integrate theoretical and empirical insights. Think of an argument as an umbrella statement, or core claim. It should be no longer than one or two sentences.

Including an argument in the introduction of your thesis may seem counterintuitive. After all, the reader will be introduced to your core claim before reading all the chapters of your thesis that led you to this claim in the first place.

But rest assured: A clear argument at the start of your thesis introduction is a sign of a good thesis. It works like a movie teaser to generate interest. And it helps the reader to follow your subsequent line of argumentation.

The core claim of your thesis should be accompanied by sufficient evidence. This does not mean that you have to write 10 pages about your results at this point.

However, you do need to show the reader that your claim is credible and legitimate because of the work you have done.

A good argument already anticipates possible objections. Not everyone will agree with your core claim. Therefore, it is smart to think ahead. What criticism can you expect?

Think about reasons or opposing positions that people can come up with to disagree with your claim. Then, try to address them head-on.

Providing a captivating preview of findings

Similar to presenting a compelling argument, a fantastic thesis introduction also previews some of the findings. When reading an introduction, the reader wants to learn a bit more about the research context. Furthermore, a reader should get a taste of the type of analysis that will be conducted. And lastly, a hint at the practical implications of the findings encourages the reader to read until the end.

If you focus on a specific empirical context, make sure to provide some information about it. The empirical context could be, for instance, a country, an island, a school or city. Make sure the reader understands why you chose this context for your research, and why it fits to your research objective.

If you did all your research in a lab, this section is obviously irrelevant. However, in that case you should explain the setup of your experiment, etcetera.

The empirical part of your thesis centers around the collection and analysis of information. What information, and what evidence, did you generate? And what are some of the key findings?

For instance, you can provide a short summary of the different research methods that you used to collect data. Followed by a short overview of how you analysed this data, and some of the key findings. The reader needs to understand why your empirical analysis is worth reading.

You already highlighted the practical relevance of your thesis in the introductory chapter. However, you should also provide a preview of some of the practical implications that you will develop in your thesis based on your findings.

Presenting a crystal clear thesis structure

A fantastic thesis introduction helps the reader to understand the structure and logic of your whole thesis. This is probably the easiest part to write in a thesis introduction. However, this part can be best written at the very end, once everything else is ready.

A reading guide is an essential part in a thesis introduction! Usually, the reading guide can be found toward the end of the introductory chapter.

The reading guide basically tells the reader what to expect in the chapters to come.

In a longer thesis, such as a PhD thesis, it can be smart to provide a summary of each chapter to come. Think of a paragraph for each chapter, almost in the form of an abstract.

For shorter theses, which also have a shorter introduction, this step is not necessary.

Especially for longer theses, it tends to be a good idea to design a simple figure that illustrates the structure of your thesis. It helps the reader to better grasp the logic of your thesis.

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox!

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The most useful academic social networking sites for PhD students

10 reasons not to do a master's degree, related articles.

Better thesis writing with the Pomodoro® technique

How to find a reputable academic dissertation editor

Left your dissertation too late? Ways to take action now

First meeting with your dissertation supervisor: What to expect

Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 397 other subscribers.

Email Address

Writing your dissertation - structure and sections

Posted in: dissertations

In this post, we look at the structural elements of a typical dissertation. Your department may wish you to include additional sections but the following covers all core elements you will need to work on when designing and developing your final assignment.

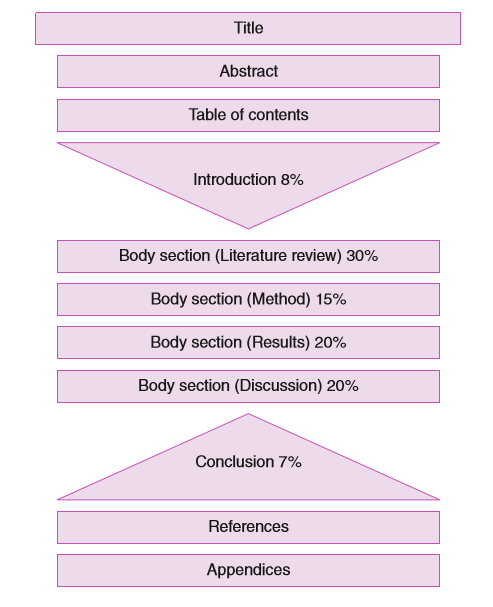

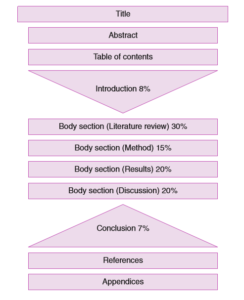

The table below illustrates a classic dissertation layout with approximate lengths for each section.

Hopkins, D. and Reid, T., 2018. The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guid e to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University . Sage.

Your title should be clear, succinct and tell the reader exactly what your dissertation is about. If it is too vague or confusing, then it is likely your dissertation will be too vague and confusing. It is important therefore to spend time on this to ensure you get it right, and be ready to adapt to fit any changes of direction in your research or focus.

In the following examples, across a variety of subjects, you can see how the students have clearly identified the focus of their dissertation, and in some cases target a problem that they will address:

An econometric analysis of the demand for road transport within the united Kingdom from 1965 to 2000

To what extent does payment card fraud affect UK bank profitability and bank stakeholders? Does this justify fraud prevention?

A meta-analysis of implant materials for intervertebral disc replacement and regeneration.

The role of ethnic institutions in social development; the case of Mombasa, Kenya.

Why haven’t biomass crops been adopted more widely as a source of renewable energy in the United Kingdom?

Mapping the criminal mind: Profiling and its limitation.

The Relative Effectiveness of Interferon Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C

Under what conditions did the European Union exhibit leadership in international climate change negotiations from 1992-1997, 1997-2005 and 2005-Copenhagen respectively?

The first thing your reader will read (after the title) is your abstract. However, you need to write this last. Your abstract is a summary of the whole project, and will include aims and objectives, methods, results and conclusions. You cannot write this until you have completed your write-up (look at our six point checklist for writing an abstract ).

Introduction

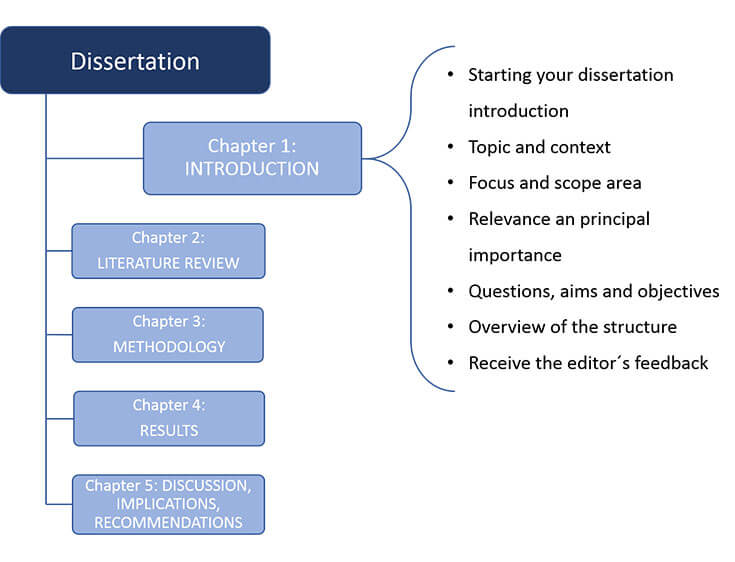

Your introduction should include the same elements found in most academic essay or report assignments, with the possible inclusion of research questions. The aim of the introduction is to set the scene, contextualise your research, introduce your focus topic and research questions, and tell the reader what you will be covering. It should move from the general and work towards the specific. You should include the following:

- Attention-grabbing statement (a controversy, a topical issue, a contentious view, a recent problem etc)

- Background and context

- Introduce the topic, key theories, concepts, terms of reference, practices, (advocates and critic)

- Introduce the problem and focus of your research

- Set out your research question(s) (this could be set out in a separate section)

- Your approach to answering your research questions.

See also Writing your introduction .

Literature review

Your literature review is the section of your report where you show what is already known about the area under investigation and demonstrate the need for your particular study. This is a significant section in your dissertation (30%) and you should allow plenty of time to carry out a thorough exploration of your focus topic and use it to help you identify a specific problem and formulate your research questions.

You should approach the literature review with the critical analysis dial turned up to full volume. This is not simply a description, list, or summary of everything you have read. Instead, it is a synthesis of your reading, and should include analysis and evaluation of readings, evidence, studies and data, cases, real world applications and views/opinions expressed. Your supervisor is looking for this detailed critical approach in your literature review, where you unpack sources, identify strengths and weaknesses and find gaps in the research.

In other words, your literature review is your opportunity to show the reader why your paper is important and your research is significant, as it addresses the gap or on-going issue you have uncovered.

See also: Developing your literature review - getting started and Developing your literature review - top tips

You need to tell the reader what was done. This means describing the research methods and explaining your choice. This will include information on the following:

- Are your methods qualitative or quantitative... or both? And if so, why?

- Who (if any) are the participants?

- Are you analysing any documents, systems, organisations? If so what are they and why are you analysing them?

- What did you do first, second, etc?

- What ethical considerations are there?

It is a common style convention to write what was done rather than what you did, and write it so that someone else would be able to replicate your study.

Here you describe what you have found out. You need to identify the most significant patterns in your data, and use tables and figures to support your description. Your tables and figures are a visual representation of your findings, but remember to describe what they show in your writing. There should be no critical analysis in this part (unless you have combined results and discussion sections).

Here you show the significance of your results or findings. You critically analyse what they mean, and what the implications may be. Talk about any limitations to your study, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of your own research, and make suggestions for further studies to build on your findings. In this section, your supervisor will expect you to dig deep into your findings and critically evaluate what they mean in relation to previous studies, theories, views and opinions.

This is a summary of your project, reminding the reader of the background to your study, your objectives, and showing how you met them. Do not include any new information that you have not discussed before.

This is the list of all the sources you have cited in your dissertation. Ensure you are consistent and follow the conventions for the particular referencing system you are using. (Note: you shouldn't include books you've read but do not appear in your dissertation).

Include any extra information that your reader may like to read. It should not be essential for your reader to read them in order to understand your dissertation. Your appendices should be labelled (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B, etc). Examples of material for the appendices include detailed data tables (summarised in your results section), the complete version of a document you have used an extract from, etc.

Adapted from: https://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/ld/all-resources/writing/writing-resources/planning-and-conducting-a-dissertation-research-project

Share this:.

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

I am finding this helpful. Thank You.

It is very useful.

Glad you found it useful Adil!

I was a useful post i would like to thank you

Glad you found it useful! 🙂

Navigating the dissertation process: my tips for final years

Imagine for a moment... After months of hard work and research on a topic you're passionate about, the time has finally come to click the 'Submit' button on your dissertation. You've just completed your longest project to date as part...

8 ways to beat procrastination

Whether you’re writing an assignment or revising for exams, getting started can be hard. Fortunately, there’s lots you can do to turn procrastination into action.

My takeaways on how to write a scientific report

If you’re in your dissertation writing stage or your course includes writing a lot of scientific reports, but you don’t quite know where and how to start, the Skills Centre can help you get started. I recently attended their ‘How...

How to Write a Compelling Thesis Introduction

The introduction to your thesis is like a first impression: you want it to be great. It is the first chapter and appears before the literature review and after the table of contents. You want the introduction to set the stage for your reader: tell them what you’re writing about, why, and what comes next. So how can you write a compelling thesis introduction?

Structure and elements of a thesis introduction

Before you write a compelling thesis introduction, you need to know what elements belong in this section and how it should be structured. A typical thesis introduction includes:

- A clear thesis statement

- An explanation of the context (brief background) for the study

- The focus and scope of the paper

- An explanation of the relevance and importance of your research

- A description of the objectives of your research and how your methodology achieves them

- A guide to the structure of the rest of the thesis (roadmap)

A thesis introduction is typically about 10% of the total length of your paper. If your introduction includes diagrams or figures, the length may be longer. It is critical to include all of the points above when writing a clear and compelling introduction. You may include additional elements if you feel they are essential in introducing your topic to the audience.

Thesis introduction: Getting started

If you do decide to write your introduction first, you can draw on the information in your thesis/dissertation proposal to help construct your draft.

How should you draft your thesis introduction, and when should you do it?

Despite the fact that your introduction comes first in the structure of your thesis, there is absolutely no need to write it first. Starting your thesis is often difficult and overwhelming, and many writers suffer from blank page syndrome —the paralysis of not knowing where to start. For this reason, some people advocate writing a kind of placeholder introduction when you begin, just to get something written down. You are free to write the introduction section at the beginning, middle, or end of the thesis drafting process . I personally find it preferable to write the introduction to a paper after I have already drafted a significant portion of the remainder of the paper. This is because I can draw on what I have written already to make sure that I cover all of the important points above.

However, if you do decide to write your introduction first, you can draw on the information in your thesis/dissertation proposal to help construct your draft. Just keep in mind that you will need to revisit your introduction after you have written the rest of your thesis to make sure it still provides an accurate roadmap and summary of the paper for your readers.

Topic and background information

When you introduce your topic, you want to draw your reader in.

Your thesis introduction should begin by informing the reader what your topic is and providing them with some relevant background information. The amount of background information you provide in this step will actually depend on what type of thesis/dissertation you are writing.

If you are writing a paper in the natural sciences or some social sciences, then it will have a separate background section after the introduction. Not a lot of background information is needed here. You can just state the larger context of the research. However, if your paper is structured such that there is no separate background chapter, then this portion of your thesis will be a bit longer and that is okay.

When you introduce your topic, you want to draw your reader in. Provide them with the reasons your research is interesting and important so that they will want to keep reading. Don’t be afraid to offer up some surprising facts or an interesting anecdote. You don’t need to be sensationalist, but your writing does not have to be dry and boring also! It is encouraged that you try to connect to your reader by offering them a relevant fact or story about your topic.

Example (topic) Weaknesses in financial regulatory systems in the United States

Example (context): Highlight some news stories about banks allowing money laundering on a massive scale, which financed gangs and led to more street drugs in major American cities. You could include a story about someone personally impacted by drugs in their neighborhood and then connect the presence of drugs to the gangs who were allowed to launder their money through big banks.

Focus and scope of your thesis

Once you have introduced your reader to the broader topic and provided some background information, you might want to explain the specific focus and scope of your thesis.

Once you have introduced your reader to the broader topic and provided some background information, you might want to explain the specific focus and scope of your thesis. What aspect of your topic will you research in particular? Why? What will your research not cover, and why? While this second part is optional, it is often helpful to be very specific about the aims of your research.

Example : Regulatory capture in the Federal Reserve and how it contributes to lax enforcement of anti-money laundering regulations.

You might write about this by explaining that your study focuses on regulatory capture in the Federal Reserve because they are one of the primary regulatory bodies monitoring the financial institutions, which were caught allowing money laundering. You could further specify that you will be focusing specifically on the role the Federal Reserve plays in monitoring banks for compliance with anti-money laundering laws; however, you will not be talking about the role they play in monitoring for compliance in other areas such as loans or mergers. This prepares your reader for what they are going to read and sets their expectations for what will come next.

Explaining the relevance and importance of your research

You must explain to the reader why your research matters, and by implication, why your reader should continue reading!

This is one of the most critical parts of your introduction. You must explain to the reader why your research matters, and by implication, why your reader should continue reading! Your research does not have to be completely revolutionary or groundbreaking to have value. You don’t need to inflate the importance of the thesis/dissertation you are writing when explaining why the research you have done is worthwhile.

Example: Corruption is an increasingly important issue in the maintenance and promotion of democratic norms and good governance. Without the ability to enforce effective penalties against institutions that turn a blind eye to money laundering, democratic governments like the United States will be threatened by the increasing power of bad actors flouting regulations. With the dollar being the global reserve currency, the US must enforce anti-money laundering legislation at home to have any hopes of shutting down global networks of corrupt operators that rely on its financial institutions. Identifying the presence of regulatory capture in the Federal Reserve sounds the alarm bell for lawmakers and regulators and suggests important interventions for policymakers are needed.

The above example clearly explains the wider impact of the issue without making overly broad statements such as “this research will revolutionize financial regulation in the United States as we know it” or “this research provides a roadmap for ending corrupt financial flows.” Just focus on what made the issue important and interesting to you and clearly state it within the broader context you provided earlier on.

Giving your reader a roadmap

At the end of your thesis introduction, you will want to provide your reader with a roadmap to the rest of the thesis.

At the end of your thesis introduction, you will want to provide your reader with a roadmap to the rest of the thesis. This differs from your table of contents in that it provides more context and details for how and why you have structured your thesis the way you have. The format of “first, next, finally” is a clear and easy way to structure this section of your introduction.

Example: First , this study reviews the existing literature on regulatory capture and how it impacts enforcement actions, with a specific focus on financial institutions and the history of the Federal Reserve. Next , it discusses the materials used for this research and how analysis was performed. Finally , it explains the results of the data analysis and investigates what the results mean and implications for future policymaking.

Now your reader knows exactly what to expect and how this fits into your overall aims and objectives. They are primed with the knowledge of your topic, its background, its relevance, and your specific focus in this study.

One common problem people have when writing an introduction to a thesis is actually writing too much . Many students and young researchers fear they won’t have enough to say and then will find themselves with a super long introduction that they somehow need to cut in half. You don’t have to give too much detail in the introduction of your thesis! Remember, the substance of your paper is located in the chapters that follow. If you are struggling with how to cut down (or add to) your introduction, you might benefit from the help of a professional editor who can see your paper with fresh eyes and quickly help you revise it. The introduction is the first part of your thesis/dissertation that people will read, so use these tips to make sure you write a great one! Check out our site for more tips on how to write a good thesis/dissertation, where to find the best thesis editing services , and more about thesis editing and proofreading services .

Editor’s pick

Get free updates.

Subscribe to our newsletter for regular insights from the research and publishing industry!

Checklist: Tips for writing a compelling thesis introduction

Remember the below points when you are writing a thesis introduction:

Know your audience

Refer to your thesis/dissertation proposal or notes

Make sure you clearly state your topic, aims, and objectives

Explain why your research matters

Try to offer interesting facts or statistics that may surprise your reader and draw their interest

Draw a roadmap of what your paper will discuss

Don’t try to write too much detail about your topic

Remember to revise your introduction as you revise other sections of your thesis

What are the typical elements in an introduction section? +

The typical elements in an introduction section are as follows:

- Thesis statement

- Brief background of the study

- The focus and scope of the article

- The relevance and importance of your research

Do I have to write my introduction first? +

You can write your introduction section whenever you feel ready. Many writers save the introduction section for last to make sure they provide a clear summary and roadmap of the content of the rest of the paper.

How long should my introduction be? +

Most introductions are about 10% of the total paper, but can be longer if they include figures or diagrams.

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

How To Write Your Dissertation Introduction

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Definition: Dissertation Introduction

- 3 Dissertation Introduction Structure

- 4 Writing a Dissertation Introduction

- 5 Dissertation Introduction Tips

- 6 Dissertation Introduction Example

- 7 In a Nutshell

Definition: Dissertation Introduction

Background information is what needs to appear first when it comes to the dissertation introduction. The structure of the other points doesn’t follow any sequence, and it is entirely up to you. You might consider introducing your main focus by presenting the aims and objectives that explain why your research area is essential, and the overall need for that particular research field. The ‘value’ section is crucial to those who will be judging the merit of your work and needs to be in your dissertation introduction, and this is important because it demonstrates that you have considered how it adds value.

What is a dissertation introduction?

The introduction of your dissertation justifies your dissertation, the thesis, or other research projects. It also explains what you are trying to answer ( research question ) and why it’s essential to do this research. It is important that the aim of the research and what it can offer to the academic community is heavily emphasized.

How do you write an introduction to a dissertation literature review?

The dissertation introduction describes your dissertation topic and provides the right context for reviewing the literature. You should create good reasons, explain the organizational sequence, and also state your scope of the review. The introduction should clearly ouline the main topics that are going to be discussed.

How do you write an introduction to a PhD?

A practical PhD dissertation introduction must establish the research area by situating your research in a broader context. It must also develop and justify your niche by describing why your research is needed. Also, state the significance of your study by explaining how you conducted your research.

Tip: For a full outline of the dissertation structure , take a look at our blog post.

How long should a dissertation introduction be?

The introduction of the dissertation consists of ten percent of the whole paper. If you are writing a dissertation of five thousand words, the introductory section should consist of five hundred words. Refer to your research questions or hypothesis if you’re having trouble writing your dissertation introduction.

What is the purpose of a dissertation introduction?

The primary purpose of writing a dissertation introduction is to introduce the dissertation topic and the primary purpose of your study. You also demonstrate the relevance of your discussion whilst convincing readers of its practical and scientific significance. It’s important that you catch the reader’s attention and this can be done by using persuasive examples from related sources.

How can I start my dissertation introduction?

Some reliable tips for starting your dissertation introduction include the use of a catchy opening sentence that will get the attention of your reader. Don’t mention everything at this point, but only outline your topic and relevant arguments. Additionally, keep your language straightforward and don’t promise anything that cannot be delivered later.

Tip: It can be hard to fight off writer’s block , so head over to our blog article for some tips. However, if you’re still having trouble writing your dissertation introduction, start writing the body of the dissertation and come back to the introduction later!

Dissertation Introduction Structure

How to structure the introduction of your dissertation:

1. Introduction

Starting your dissertation introduction – this should be the last part to write. You can write a rough draft to help guide you. It’s crucial to draw the reader’s attention with a well-built beginning. Set your research introduction stage with a clear focus and purpose that gives a direction.

2. Topic and its context

Topic and context – introduce your problem and give the necessary background information. Aim to show why the question is timely or essential. Mention a relevant news item like an academic debate.

3. Focus and scope area

Focus and scope – after introduction part, narrow down and focus on defining the scope of your research. For instance, what demographics or communities are you researching? What geographical area are you investigating?

4. Relevance and principal importance

Relevance and importance – show how your research will address the problem gap in your identified research area. Cite relevant literature and describe how the new insights will contribute to the importance of your research. Explain how your research will build on existing research to help solve a practical or theoretical problem.

5. Questions, aims and objectives

Questions and objectives – this is where you set up the expectations of the remaining part of your dissertation. You can formulate the research questions depending on your topic, focus, and discipline. Also, state the methods that you used to get the answers to your questions here if your dissertation doesn’t have a methodology chapter. If your research aims at testing hypotheses, formulate them here.

6. Overview summary

Overview of the structure – this part summarizes sections and shows how the introduction of your dissertation contributes to your aims and objectives. Keep this part short by using one or two sentences to describe the contents of each section.

7. Receive the editor´s feedback

Receive the editor’s feedback – some professional editors will proofread and edit your paper based on instructions given, such as the academic style. They will also check grammar, vague sentences, and style consistency and provide a report on your language use, structure, and layout.

Writing a Dissertation Introduction

In academic writing , there are active steps that a writer can take to attract the reader’s interest. Establish a specific area by showing your target audience that it’s significant and exciting. Introduce and evaluate previous research in the same area. Determine a niche by indicating the gaps in previous studies.

An excellent dissertation introduction allows you to:

- List hypotheses or research questions

- State the nature of your research primary purposes

- Indicate the outline of your academic project

- Announce important research findings

- State the value of previous studies in that field.

Dissertation Introduction Tips

Knowing when to use which tense in your dissertation or thesis is a common problem. A dissertation introduction is a plan of a study not yet conducted, so any reference needs to be in the future tense. Any reference to a study that is already published should be in the past tense. Statements regarding a program, theory, policy, or a concept that is still in effect should be in the present tense. Stay impersonal and make use of a list.

For example, say: firstly, secondly, etc., rather than first, second, etc.

Use ‘a’ when talking about something in general and ‘the’ when talking about something in particular., dissertation introduction example.

How to write a dissertation introduction:

Dissertation printing & binding

You are already done writing your dissertation and need a high quality printing & binding service? Then you are right to choose BachelorPrint! Check out our 24-hour online printing service. For more information click the button below :

Dissertation Printing & Binding

In a Nutshell

- A dissertation introduction is like a road map that tells your audience the direction your research will take.

- The introduction is the summary of the general context and scope of your topic and gives reference to previous literature on the subject.

- It includes the purpose of your research and the reasoning about why it’s relevant to conduct the study.

- It describes the research processes and gives an idea of the study, and also addresses the type of references available.

- It provides a summary of the specific questions and issues to address in the proposal.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates

Published on 8 June 2022 by Tegan George .

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical early steps in your writing process . It helps you to lay out and organise your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

Generally, an outline contains information on the different sections included in your thesis or dissertation, such as:

- Your anticipated title

- Your abstract

- Your chapters (sometimes subdivided into further topics like literature review, research methods, avenues for future research, etc.)

In the final product, you can also provide a chapter outline for your readers. This is a short paragraph at the end of your introduction to inform readers about the organisational structure of your thesis or dissertation . This chapter outline is also known as a reading guide or summary outline.

Table of contents

How to outline your thesis or dissertation, dissertation and thesis outline templates, chapter outline example, sample sentences for your chapter outline, sample verbs for variation in your chapter outline, frequently asked questions about outlines.

While there are some inter-institutional differences, many outlines proceed in a fairly similar fashion.

- Working Title

- ‘Elevator pitch’ of your work (often written last).

- Introduce your area of study, sharing details about your research question, problem statement , and hypotheses . Situate your research within an existing paradigm or conceptual or theoretical framework .

- Subdivide as you see fit into main topics and sub-topics.

- Describe your research methods (e.g., your scope, population , and data collection ).

- Present your research findings and share about your data analysis methods.

- Answer the research question in a concise way.

- Interpret your findings, discuss potential limitations of your own research and speculate about future implications or related opportunities.

To help you get started, we’ve created a full thesis or dissertation template in Word or Google Docs format. It’s easy adapt it to your own requirements.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

It can be easy to fall into a pattern of overusing the same words or sentence constructions, which can make your work monotonous and repetitive for your readers. Consider utilising some of the alternative constructions presented below.

Example 1: Passive construction

The passive voice is a common choice for outlines and overviews because the context makes it clear who is carrying out the action (e.g., you are conducting the research ). However, overuse of the passive voice can make your text vague and imprecise.

Example 2: IS-AV construction

You can also present your information using the ‘IS-AV’ (inanimate subject with an active verb) construction.

A chapter is an inanimate object, so it is not capable of taking an action itself (e.g., presenting or discussing). However, the meaning of the sentence is still easily understandable, so the IS-AV construction can be a good way to add variety to your text.

Example 3: The I construction

Another option is to use the ‘I’ construction, which is often recommended by style manuals (e.g., APA Style and Chicago style ). However, depending on your field of study, this construction is not always considered professional or academic. Ask your supervisor if you’re not sure.

Example 4: Mix-and-match

To truly make the most of these options, consider mixing and matching the passive voice , IS-AV construction , and ‘I’ construction .This can help the flow of your argument and improve the readability of your text.

As you draft the chapter outline, you may also find yourself frequently repeating the same words, such as ‘discuss’, ‘present’, ‘prove’, or ‘show’. Consider branching out to add richness and nuance to your writing. Here are some examples of synonyms you can use.

A thesis or dissertation outline is one of the most critical first steps in your writing process. It helps you to lay out and organise your ideas and can provide you with a roadmap for deciding what kind of research you’d like to undertake.

When you mention different chapters within your text, it’s considered best to use Roman numerals for most citation styles. However, the most important thing here is to remain consistent whenever using numbers in your dissertation .

All level 1 and 2 headings should be included in your table of contents . That means the titles of your chapters and the main sections within them.

The contents should also include all appendices and the lists of tables and figures, if applicable, as well as your reference list .

Do not include the acknowledgements or abstract in the table of contents.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, June 08). Dissertation & Thesis Outline | Example & Free Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved 18 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/outline-thesis-dissertation/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation table of contents in word | instructions & examples, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples.

- How it works

How to Structure a Dissertation – A Step by Step Guide

Published by Owen Ingram at August 11th, 2021 , Revised On September 20, 2023

A dissertation – sometimes called a thesis – is a long piece of information backed up by extensive research. This one, huge piece of research is what matters the most when students – undergraduates and postgraduates – are in their final year of study.

On the other hand, some institutions, especially in the case of undergraduate students, may or may not require students to write a dissertation. Courses are offered instead. This generally depends on the requirements of that particular institution.

If you are unsure about how to structure your dissertation or thesis, this article will offer you some guidelines to work out what the most important segments of a dissertation paper are and how you should organise them. Why is structure so important in research, anyway?

One way to answer that, as Abbie Hoffman aptly put it, is because: “Structure is more important than content in the transmission of information.”

Also Read: How to write a dissertation – step by step guide .

How to Structure a Dissertation or Thesis

It should be noted that the exact structure of your dissertation will depend on several factors, such as:

- Your research approach (qualitative/quantitative)

- The nature of your research design (exploratory/descriptive etc.)

- The requirements set for forth by your academic institution.

- The discipline or field your study belongs to. For instance, if you are a humanities student, you will need to develop your dissertation on the same pattern as any long essay .

This will include developing an overall argument to support the thesis statement and organizing chapters around theories or questions. The dissertation will be structured such that it starts with an introduction , develops on the main idea in its main body paragraphs and is then summarised in conclusion .

However, if you are basing your dissertation on primary or empirical research, you will be required to include each of the below components. In most cases of dissertation writing, each of these elements will have to be written as a separate chapter.

But depending on the word count you are provided with and academic subject, you may choose to combine some of these elements.

For example, sciences and engineering students often present results and discussions together in one chapter rather than two different chapters.

If you have any doubts about structuring your dissertation or thesis, it would be a good idea to consult with your academic supervisor and check your department’s requirements.

Parts of a Dissertation or Thesis

Your dissertation will start with a t itle page that will contain details of the author/researcher, research topic, degree program (the paper is to be submitted for), and research supervisor. In other words, a title page is the opening page containing all the names and title related to your research.

The name of your university, logo, student ID and submission date can also be presented on the title page. Many academic programs have stringent rules for formatting the dissertation title page.

Acknowledgements