Gastroesophageal reflux disease: the case for improving patient education in primary care

Affiliation.

- 1 Advanced Gastroenterology Associates, St. Alexius Medical Center, Hoffman Estates, IL, USA. Email: [email protected].

- PMID: 24340333

Purpose: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects up to 25% of the western population, and the annual expenditure for managing GERD is estimated to be more than $14 billion. Most GERD patients do not consult a specialist, but rather rely on their primary care physician for symptom management. Research has shown that many patients--regardless of diagnosis--do not fully understand what their doctors tell them and remain uncertain as to what they are supposed to do to take care of themselves. To determine if patients are adequately educated in the management of GERD, we conducted a survey.

Method: We administered a survey to patients with GERD in an outpatient setting and explored their knowledge of such management practices as modification of behavior and diet and use of medication.

Results: Of 333 patients enrolled, 66% reported having an in-depth discussion with their primary care physician. Among patients taking a proton pump inhibitor, 85% of those who’d had an in-depth discussion were aware of the best time to take their medication, compared with only 18% of those who did not have an in-depth discussion. In addition, patients who’d had in-depth conversations were significantly more likely than those who didn’t to know some of the behavior modification measures that might improve their symptoms.

Conclusion: Our study underscores the need for primary care providers to fully discuss GERD with their patients to improve overall management of the disease.

- Aged, 80 and over

- Gastroesophageal Reflux / psychology

- Gastroesophageal Reflux / therapy*

- Health Care Surveys

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice*

- Middle Aged

- Patient Compliance*

- Patient Education as Topic*

- Physician-Patient Relations*

- Primary Health Care*

- Proton Pump Inhibitors / therapeutic use

- Risk Reduction Behavior

- Proton Pump Inhibitors

Introduction

Disclosure statement, clinical presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a prospective study on symptom diversity and modification of questionnaire application.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Ryan Broderick , Karl-Hermann Fuchs , Wolfram Breithaupt , Gabor Varga , Thomas Schulz , Benjamin Babic , Arielle Lee , Frauke Musial , Santiago Horgan; Clinical Presentation of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Prospective Study on Symptom Diversity and Modification of Questionnaire Application. Dig Dis 13 May 2020; 38 (3): 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1159/000502796

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Introduction: Symptoms occurring in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) such as heartburn, regurgitation, thoracic pain, epigastric pain, respiratory symptoms, and others can show a broad overlap with symptoms from other foregut disorders. The goal of this study is the accurate assessment of symptom presentation in GERD. Methods: Patients with foregut symptoms were investigated for symptoms as well as endoscopy and gastrointestinal-functional studies for presence of GERD and symptom evaluation by standardized questionnaire. Questionnaire included a graded evaluation of foregut symptoms documenting severity and frequency of each symptom. The three types of questionnaires include study nurse solicitated, self-reported, and free-form self-reported by the patient. Results: For this analysis, 1,031 GERD patients (572 males and 459 females) were enrolled. Heartburn was the most frequently reported chief complaint, seen in 61% of patients. Heartburn and regurgitation are the most common (82.4/58.8%, respectively) in overall symptom prevalence. With regard to modification in questionnaire technique, if patients fill in responses without prompting, there is a trend toward more frequent documentation of respiratory symptoms (up to 54.5% [ p < 0.01]), fullness (up to 93.9%), and gas-related symptoms ( p < 0.001). Self-reported symptoms are more diverse (e.g., throat-burning [12%], mouth-burning [9%], globus [6%], dyspnea [9%], and fatigue [7%]). Conclusions: GERD symptoms are commonly heartburn and regurgitation, but overall symptom profile for patients may change depending on the type of questionnaire.

Since gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has a prevalence of 20% in industrialized countries, symptoms associated with the disease are common in these populations [ 1, 2 ]. In order to define GERD, the authors of the Montreal classification relied heavily on symptoms and their effect on patients: “GERD is a condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications” [ 1 ]. These symptoms can reduce patient’s well-being and have a negative influence on the quality of life [ 3, 4 ].

In many studies, GERD symptoms are used to define the study populations [ 5‒13 ]. Other studies, however, have some evidence that symptoms are not always reliable as a guide to the diagnosis of GERD [ 14‒17 ]. GERD symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, thoracic pain, epigastric pain, respiratory symptoms, globus, and others show a broad overlap with symptoms from other esophageal and gastric disorders such as dyspepsia, esophageal motility disorders, functional heartburn, hypersensitive esophagus, irritable stomach and bowel, and somatoform disorders [ 1 , 14‒17 ]. The wide array of symptoms and potential diagnoses make one consider if there is a specific questioning technique or symptom profile that is more highly suggestive of GERD. Klauser et al. [ 18 ] have stated that heartburn and regurgitation are the most typical symptoms characterizing GERD, but in clinical practice, a large variety of esophageal and extra-esophageal symptoms can be reported.

Over the last 3 decades, our team had documented symptoms of GERD patients in a large data bank. Initially, the evaluations were standardized and leaned heavily on the early DeMeester symptom score and Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index [ 19‒22 ]. Several years later, these questions were validated within the project of creating a symptom questionnaire featuring 53 items to determine somatoform tendencies [ 17 ]. With the exception of respiratory symptoms, all items in this current questionnaire differentiated significantly between healthy volunteers and patients with foregut symptoms [ 17 ].

The goals of this study are to determine the diversity and most common symptoms of GERD in large patient populations over time. Additionally, we aim to determine if the method of questioning is significant in altering the symptom profile of GERD patients.

Study Design

Over the course of more than 2 decades, our working group had the opportunity to investigate a large population of patients with GERD in a specialized center for benign esophageal and gastric disorders. All patients with foregut symptoms referred for further exploration of esophageal and/or gastric disease underwent a history and physical examination. The symptoms of the patients were evaluated by a standardized questionnaire over the complete time period from 1995 to 2017. Only the method of application for the questionnaires was changed over time, as described in detail below. All patients received an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and esophageal manometry. In more recent years, a high-resolution manometry was performed [ 23 ]. The presence of pathologic reflux was evaluated by 24-h pH monitoring and later by impedance-pH monitoring.

Varying methods of questionnaire administration were used over the years in different time segments to evaluate the patient’s symptoms, as indicated below:

Group 1: (Study period 1995–1999) The study nurse used the standard questionnaire to ask the patients for the symptoms and marked the answers of the patients regarding presence and severity of the symptoms herself.

Group 2: (Study period 2005–2009) The study nurse handed the questionnaire over to the patients and the patients were left alone to fill in the presence and the severity of the symptoms. The patients could ask for assistance to the nurse, if needed.

Group 3a: (Study period 2015–2017) The study nurse handed the questionnaire over to the patients and the patients were left alone to fill in the presence and the severity of the symptoms in the document.

Group 3b: (Study period 2015–2017) Patients (same patients of Group 3a) were asked to document in a free-text version the 3 most important symptoms that limit or reduce the patient’s quality of life. Patients were instructed by the study nurse to document their most relevant symptoms as precisely as possible. Additionally, the study nurse also handed the standard questionnaire over to the patients and the patients were left alone to fill in the presence and the severity of the symptoms. It is important to notice that the free formulated description of the symptoms by the patients themselves was always conducted before the patients filled in the standardized questionnaire. This order was kept with the aim to avoid influences of the standard questionnaire to the patient formulated free text.

The groups were chosen for different time periods, in which changes of the symptom evaluation was established (solicited, self-reported, and free-form self-reported). The standard symptom questionnaire remained the same over the study duration.

Patient Selection and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The patients were recruited in a tertiary referral center for foregut disorders and its diagnostic functional laboratory and surgery unit. The management of the patients was performed by the same team (same study nurse) over the complete period 1995–2017. The patients were asked to give informed consent to the study evaluation and the diagnostic work-up. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

The data were reviewed in a prospectively maintained databank. Inclusion criteria for this analysis were patients with documented GERD, which required either the presence of esophagitis (esophagitis grading according to Savary-Miller 1–4), pathologic esophageal acid exposure on pH testing, and/or a hiatal hernia with heartburn and/or regurgitation. The hiatal hernia was documented during endoscopy by measuring the vertical extent of the distance between the cardia (beginning of the gastric folds) and the waist of the crurae, best assessed during inspiration (distance >1 cm). Care was taken to measure this length in the beginning of the endoscopy without major air insufflation of the stomach to avoid hernia reduction.

This analysis was not performed in some time periods (2000–2004 and 2010–2014), during which the documentation of symptoms was not rigorously followed due to shortage in personnel for administering the questionnaire. In addition, other exclusion criteria were if patients had other diseases such as cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, esophageal spasm, achalasia, or if they had prior operations for GERD.

The Questionnaire

For symptom evaluation, a standardized questionnaire was established and used over 25 years. The questionnaire included a graded evaluation of foregut symptoms: heartburn, regurgitation, retrosternal/thoracic pain, respiratory symptoms (cough/hoarseness), dysphagia, epigastric pain (pain/cramps/burning), nausea/vomiting, fullness (unpleasant fullness, early satiety), and gas-related symptoms (belching/bloating/flatulence). Patients had to document the severity and frequency of each symptom by grading according to the following system: 0 = no symptoms; 1 = symptom occurring rarely; 2 = symptom occurring occasionally; 3 = symptom occurring monthly and/or with mild intensity; 4 = symptom occurring weekly and/or with moderate intensity; 5 = symptoms occurring daily and/or with severe intensity.

Statistical Methods

Symptom results were analyzed according to their documented overall presence in these patients, independent of their severity, as well as by the most frequently reported significant/chief complaints. The mean intensity of the presented symptoms was analyzed. Statistical comparison with a t test for unpaired samples was used for the comparison of data from the different samples. A chi-square test was used for comparison of group data.

From 1995 to 2017, over 2,000 patients with symptoms indicative of GERD were seen by our team. Patients with other gastrointestinal diseases that could influence foregut symptoms were excluded from this study. In total, 1,031 met all inclusion criteria as GERD patients and were enrolled from 3 different time segments. Group 1 (1995–1999) included 481 patients, Group 2 (2005–2009) had 333 patients, and Group 3a/3b (2015–2017) had 217 patients. There were 572 males and 459 females. Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of patients in the different groups. Presence of esophagitis, evidence of lower esophageal sphincter incompetence, esophageal acid exposure, and the level of quality of life showed severity of GERD among the patients in different groups over the years.

Patients’ characteristics for each group

Frequency of Chief Complaints and Overall Presence of Symptoms

Heartburn (retrosternal burning rising from the epigastrium to the chest) was the most frequent chief symptom (intensity: 5), independent of exam technique (Table 2 : Group 1: 60%; Group 2: 61%; Group 3a: 61.6%; Group 3b: 48.5%). Table 2 shows the frequency of chief complaints in the different groups. When the questionnaire is filled in by the study nurse (Group 1), the most common symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation (60%, 17%). Additionally in Group 1, other symptoms such as epigastric pain, dysphagia, or gas-related symptoms such as bloating, belching, and flatulence are not often experienced as the primary symptom (frequencies <15%). When comparing between groups, there are significant differences between the reported symptoms (Group 1 vs. Group 2/Group 3a). More often patients self-report respiratory symptoms (1.6% vs. 21.3%/20.2%; p < 0.001), epigastric pain (13.1% vs. 24.7%/12.1%), and gas-related problems (2.6% vs. 27.2%/22.0%; p < 0.01).

Overview on the percentage of documented symptoms with intensity 5 (chief complaint) differentiated for each group

Table 3 provides an overview on the overall presence of symptoms as evaluated in the various time periods. Heartburn and regurgitation are most frequent in Group 1 (82.4 and 58.8%, respectively). If patients fill in the questionnaire themselves, there are significant differences between groups in the presence of documentation of respiratory symptoms (Group 1: 11.8%; Group 2: 24.9%; Group 3a: 54.5%; p < 0.01), fullness (1: 11%; 2: 72.7%; 3: 93.9%; p < 0.001), and gas-related symptoms (1: 34%; 2: 72.7%; 3: 93.9%). These differences are even more pronounced in recent years.

Overview on the percentage of overall presence of documented symptoms differentiated for each group

Administration of Free-Text Form of Symptom Evaluation

When patients report their symptoms in their own words prior to completing the standard questionnaire (Group 3b), the documented variety of symptoms increases compared to the structured questionnaire alone (Table 4 ). In Group 3b, heartburn remains the most frequently reported symptom both as chief complaint (31%) and in the overall presence (48.5%). Reported symptoms are much more diversified: burning in the throat (12%), burning in the mouth (9%), globus (6%), headache (1%), dyspnea (9%), and fatigue (7%; Table 4 ).

Overview on percentage of symptoms in a free-text version self-assessed symptoms versus documentation in a self-assessed structured questionnaire

Intensity of Symptoms and Their Relation to Objective Functional Data

Data on the intensity of symptoms are summarized in Table 5 . The intensity of heartburn is highest in all groups (Group 1: 3.61; Group 2: 3.88; Group 3a: 3.39). The nurse documented the intensity of the symptoms such as regurgitation, retrosternal pain, epigastric pain, and respiratory symptoms higher (Group 1) than the patients themselves (Groups 2 and 3).

Overview on the mean intensity of symptoms differentiated for each group

The relationship between symptom intensity and the esophageal functional status show only for heartburn a significant rise in intensity for patients with and without lower esophageal sphincter-incompetence. These differences were for Group 1: 3.1 vs. 3.9; for Group 2: 3.2 vs. 3.9; for Group 3: 1.8 vs. 3.4 (all p < 0.005). The differences in symptom intensity are also significant for some comparisons with regurgitation; however, all other symptoms have no remarkable differences detected for changes in objective functional status.

We show that despite altering modality of questioning and symptom assessment in GERD patients, heartburn is the most frequently reported symptom. The severity and intensity of heartburn were documented to be the highest among all other symptoms through all years of investigation. The reported intensity of heartburn is significantly increased when the functional status of the antireflux barrier deteriorates. On the other hand, the presence/absence and intensity of other symptoms (e.g., regurgitation, respiratory symptoms, bloating) can depend on the concept and details of questioning. Allowing the patients to report free-form selection of symptoms shows a larger variety of documented chief complaints and other gas-related symptoms that may not be appreciated on standardized questionnaire.

Similar to our study, literature review shows that heartburn is reported to be present in patients with pathologic esophageal acid exposure in 72–99% [ 1 , 3 , 14 , 17 , 18 , 24‒28 ]. Regurgitation is another important symptom in GERD, with a prevalence of 33–86% [ 1, 14, 17, 29, 30 ]. According to some studies, epigastric pain is present in patients with foregut symptoms in 70% and in those with documented pathologic acid reflux in 12–67% [ 1, 3, 14, 17 ]. Our study confirms the importance of heartburn as the classic symptom with the highest intensity and the highest frequency as a chief complaint throughout the study. In Group 3b (free-text format), the symptom of heartburn was further delineated as “burning in the throat” or “burning in the mouth” in up to 14%.

Results of the present study show that the documented presence of symptoms can depend on the method of questioning (e.g., whether the symptoms are asked by a study nurse or if the patients are documenting without solicitation). The more the patient is free in her/his answering the questionnaire, symptom variability increases, especially with increased incidence of gas-related and atypical symptoms. The overall presence of heartburn remains independent of questionnaire administration around 80%. Notably, a statistically significant finding of respiratory symptom presence increases from 11 to 50% and the gas-related symptoms from 30 to 90% depending on questionnaire modality of application. All other symptoms have a much lower incidence in our GERD patients, and therefore, functional investigations are helpful to confirm the disease if esophagitis is absent.

There has been a controversial discussion about symptoms as a diagnostic tool for the presence of GERD, initiated by the Montreal definition [ 1 , 14 , 18‒20 ]. Our study confirms that there is a significant diversity of foregut symptoms present in GERD patients, as well as numerous extra-esophageal complaints such as cough, hoarseness, burning sensation in pharynx, mouth, and tongue in patients [ 1 , 14‒17 ]. Extra-esophageal symptoms can be respiratory symptoms such as chronic cough, hoarseness, and shortness of breath [ 31‒38 ]. There may also be symptoms at the level of the head and neck such as globus or burning in the mouth or throat. Recent studies show limitations of measuring acid reflux in the pharynx with current technology [ 37, 39, 40 ]. It remains difficult to correlate these symptoms with reflux episodes, even with objective testing.

We show that our validated questionnaire provides adequate assessment of patient symptoms. Allowing free-form reporting of symptoms in addition to a structured questionnaire may provide a more robust symptom profile in reflux disease. There is evidence in literature that structured questionnaires are very helpful and effective for symptom evaluation, and this is confirmed by our study [ 41‒46 ]. Several instruments have been published, validated, and successfully used in clinical practice [ 41‒46 ]. Various questionnaires published include the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Symptom Severity Index, the Gastrointestinal Rating Scale, the Chinese GERD Questionnaire, the GERD-Health Related Quality of Life Instrument, the Esophageal Symptoms Questionnaire, and the Reflux Disease Questionnaire [ 41‒43 , 47‒50 ]. A systematic review of all the available questionnaires for the assessment of GERD showed that many differ in design, validation, and translation [ 43 ]. One should be aware of the strength and shortcomings of each before selecting one for use [ 43 ]. All instruments have a self-assessment or self-administered mode of application, usually evaluating severity and/or frequency of GERD symptoms with a median of 15 items (6–30 items) [ 41‒43 , 47‒50 ]. The most useful instruments allowed for self-assessment by the patients [ 43 ]. However, none of these surveys allow for a free-text version of symptom documentation such as the one tested in this study.

When using the questionnaire over the years we noticed that many patients added remarks in the margin, indicating a possible lack of options or inadequate description. The unprompted free-form clarification of symptoms stimulated the impetus for providing patients more space to document symptoms in this way. None of the available validated questionnaires leaves room for the patient’s free text. Variations in patient symptoms such as burning in the mouth, tongue, and throat may be important features to document. In the past, one could only speculate that these symptoms were superficially classified as heartburn or odynophagia. Most of the available structured and validated questionnaires focus on heartburn, epigastric pain, fullness, bloating, regurgitation, and dysphagia. Therefore, it may be reasonable to add a free-text section to GERD questionnaires for detection of rare but important symptoms restricting the patient’s quality of life.

While expanding structured questionnaires to integrate all possible symptoms would be able to register all symptom variations, the more items to be answered lengthen and complicate the questionnaire process, potentially reducing applicability. Recently developed technologies allow patients to record symptoms in an electronic diary using a mobile electronic device. These technologies may be able to integrate self-administered and free text from evaluations to receive a more realistic and clinically valuable assessment.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective character of the analysis and the long duration of data sampling. Additionally, there were periods of time during the study period where documentation was not able to be rigorously completed due to shortage of nurses (2000–2004, 2010–2014), so data from these periods were excluded and sample size reduced as a result. Overall, the size of the patient data sampling performed by one team and one study nurse provides a dependable performance of data sampling and robust data for comparison of the changing techniques of administrating the assessment of GERD symptoms.

GERD remains a disease with a wide variety of symptoms experienced by patients. While heartburn and regurgitation remain mainstays of symptom reporting, there may be a range of symptoms and intensities of symptoms that go unreported if not elicited in a free-text format. The variety of symptoms experienced also shows the importance of a full correlating objective workup with esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy, high-resolution manometry, and impedance-pH testing to assist with accurate diagnosis of patients who may need surgical correction of their disease.

GERD symptoms are commonly heartburn, regurgitation, fullness, respiratory, and gas/bloat-related. The most important and frequent symptom is heartburn and its intensity parallels objective functional parameters of the esophagus. The overall symptom profile of patients may vary depending on the modality of questioning: practitioner directed, patient questionnaire, or free-form patient reporting of symptoms. Objective studies should be a key component in determining treatment for GERD due to the wide disparity in presenting symptoms.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, suggested reading.

- Online ISSN 1421-9875

- Print ISSN 0257-2753

INFORMATION

- Contact & Support

- Information & Downloads

- Rights & Permissions

- Terms & Conditions

- Catalogue & Pricing

- Policies & Information

- People & Organization

- Stay Up-to-Date

- Regional Offices

- Community Voice

SERVICES FOR

- Researchers

- Healthcare Professionals

- Patients & Supporters

- Health Sciences Industry

- Medical Societies

- Agents & Booksellers

Karger International

- S. Karger AG

- P.O Box, CH-4009 Basel (Switzerland)

- Allschwilerstrasse 10, CH-4055 Basel

- Tel: +41 61 306 11 11

- Fax: +41 61 306 12 34

- Contact: Front Office

- Experience Blog

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 34: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Burning Question Level II

Brian A. Hemstreet

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Learning objectives, patient presentation.

- CLINICAL PEARL

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Instructors can request access to the Casebook Instructor's Guide on AccessPharmacy. Email User Services ( [email protected] ) for more information.

After completing this case study, the reader should be able to:

Describe the clinical presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), including typical, atypical, and alarm symptoms.

Discuss appropriate diagnostic approaches for GERD, including when patients should be referred for further diagnostic evaluation.

Recommend appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures for treating GERD.

Develop a treatment plan for a patient with GERD, including both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures and monitoring for efficacy and toxicity of selected drug regimens.

Outline a patient education plan for proper use of drug therapy for GERD.

Chief Complaint

“I’m having a lot of heartburn. These pills I have been using have helped a little but it’s still keeping me up at night.”

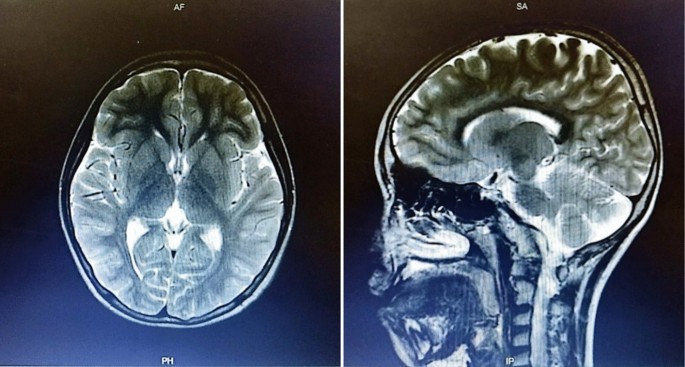

Janet Swigel is a 68-year-old woman who presents to the GI clinic with complaints of heartburn four to five times a week over the past 5 months. She also reports some regurgitation after meals that is often accompanied by an acidic taste in her mouth. She states that her symptoms are worse at night, particularly when she goes to bed. She finds that her heartburn worsens and she coughs a lot at night, which keeps her awake. She has had difficulty sleeping over this time period and feels fatigued during the day. She reports no difficulty swallowing food or liquids. She has tried OTC Prevacid 24HR once daily for the past 3 weeks. This has reduced the frequency of her symptoms to 3–4 days per week, but they are still bothering her.

Atrial fibrillation × 12 years

Asthma × 10 years

Type 2 DM × 5 years

HTN × 10 years

Patient is married with three children. She is a retired school bus driver. She drinks one to two glasses of wine 4–5 days per week. She does not use tobacco. She has commercial prescription drug insurance.

Father died of pneumonia at age 75; mother died at age 68 of gastric cancer

Diltiazem CD 120 mg PO once daily

Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg PO once daily

Metformin 500 mg PO twice daily

Aspirin 81 mg PO daily

Fluticasone/salmeterol DPI 100 mcg/50 mcg one inhalation twice daily

Peanuts (hives)

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Nutrition counsellor

- Food Allergy

- gastroenterology

- Heptologist In Delhi

- Liver transplant

- Case Study on Gastroesophageal Reflux in Middle-Aged Woman

Patient: Female, 52

Final diagnosis: Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal Reflux signs and Symptoms: burning pain in the chest that usually occurs after eating and worsens when lying down.

Speciality: Gastroenterology

Causes, symptoms, and treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects as many middle-aged women as males. It might manifest as heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, or chest discomfort. We examined the severity of symptoms in women is significantly more than in men and may contribute to earlier disease recognition and different disease management.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Case Study

A 52-year-old woman was referred to gastroenterology practice for a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The patient claims to have had heartburn symptoms for at least five years. Her symptoms responded to over-the-counter medications such as antacid tablets and liquids, but they grew so frequent that she sought medical attention from her primary care physician.

Later, she reported minor acid reflux at least twice a week. She does not have any other chronic medical issues and does not use any other drugs. Her social background includes severe alcohol usage for 20 years, which she discontinued after being diagnosed with liver illness four years ago. There is no family history of gastrointestinal cancer in her family.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Causes

Gastroesophageal reflux disease, often known as GERD, is a digestive illness that affects the muscular ring between your oesophagus and stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter is the term given to this ring (LES). You may have heartburn or acid indigestion if you have it. Doctors believe that some people develop it as a result of a disease known as hiatal hernia. In most situations, GERD symptoms can be alleviated via dietary and lifestyle modifications. However, some people may require taking medication or going under surgery.

Dysphagia, nausea or vomiting, blood in her stool, or accidental weight loss were all symptoms she encountered. Most people can control their GERD symptoms with simple lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medicines. However, she may require more potent medication or surgery to cure her problems. Because the patient has a history of alcoholism, she is particularly sensitive to this condition.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Age Range

We observed that the usual age group with GERD symptoms is primarily middle-aged women, i.e. (age range 36 to 55).

Gastroesophageal Reflux symptoms

Heartburn is the most common symptom of GERD. (GERD) occurs when stomach acid regularly rushes back into the tube that links your mouth and stomach (oesophagus). Acid reflux (backwash) can irritate the esophageal lining. Many people experience acid reflux on a regular basis.

Common signs and symptoms of GERD include:

- A burning sensation in your chest (heartburn), usually after eating, which could be worse during the night

- Difficulty swallowing

- Regurgitation of food or sour liquid

- Throat lump sensation

Night-time acid reflux, one might also experience:

- Chronic cough

- New or worsening asthma

- Disrupted sleep

Gastroesophageal reflux risk factors include:

- Bulging the top of the stomach up into the diaphragm

- Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma

- Delayed stomach emptying

Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms and Treatment

Lying down is one of the home treatments for GERD. According to most researchers, the optimal height of bed head elevation is at least 6-8 inches (15-20 centimetres). This height has been shown in studies to reduce acid reflux when lying down. In reality, the higher the height, the better.

Gastroesophageal reflux management

GERD therapy aims to reduce the quantity of reflux or decrease the damage to the oesophagus lining affected by the refluxed materials.

Over the counter or prescription, medicine recommendations work to address Gastroesophageal reflux causes and symptoms.

- Antacids: These medications can help neutralize the acid in the oesophagus and stomach, therefore alleviating heartburn. Non-prescription antacids give brief or partial relief for many people. Some people benefit from an antacid coupled with a foamy agent. These chemicals, according to researchers, form a foam barrier on top of the stomach, preventing acid reflux.

- H2 blockers: For persistent reflux and heartburn, the doctor may prescribe medicines to decrease stomach acid. H2 blockers, which assist in inhibiting acid production in the stomach, are among these medications. Cimetidine (Tagamet), famotidine (Pepcid), and nizatidine are models of H2 blockers.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): Often known as acid pumps, medications that reduce stomach acid production by blocking a protein. Dexlansoprazole (Dexilant), esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), omeprazole (Prilosec), omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate (Zegerid), pantoprazole (Protonix), and rabeprazole are all proton pump inhibitors (Aciphex).

- Prokinetics: In rare circumstances, these medicines assist your stomach empty faster, resulting in less acid being left behind. They may also aid in the treatment of symptoms such as bloating, nausea, and vomiting. Domperidone and metoclopramide are two samples of prokinetics (Clopra, Maxolon, Metozolv, Reglan). Many individuals are unable to take them, and those who can only do so for a short time.

In this case, she was initially given an H2 blocker, which proved ineffective, so she was put on proton pump inhibitor treatment for a while. She presently takes 20mg of omeprazole daily, which she finds beneficial, although she does have heartburn if she skips a dosage. The patient can now comfortably swallow meals and liquids and shows no indications of vomiting or nausea. The patient is constantly monitored and encouraged to make certain dietary and lifestyle modifications. She is recommended to abstain totally from alcohol and cigarettes.

Routine check-ups and proper treatments can help patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux cure. Suppose you are experiencing any symptoms mentioned above. In that case, you can follow the Gastroesophageal reflux care plan by getting in touch with the online gastroenterologist doctor . You can talk to the gastroenterologist and consult gastroenterologist online free. Services are available in different cities, consult her as a gastroenterologist, the best doctor in Patna for the stomach , best female gynaecologist in Jhansi , gastro surgeon in Delhi , liver cirrhosis specialist doctor in India, NCR gastro liver clinic Gurgaon, max hospital liver specialist, the gastro & liver clinic Patna Bihar and best physician in Jammu city .

1. Can GERD affect my heart?

GERD and the associated heartburn have nothing to do with heart or heart disease even though the burning chest in pain seems like a pain in the heart.

2. Are there symptoms other than heartburn for GERD?

Other symptoms include regurgitation of acid up in the throat, bitter taste in the mouth, persistent dry cough, and wheezing among others.

3. Why doesn’t the acid harm the stomach?

The stomach has a thick lining that protects it from damage by acid. The oesophagus does not have this lining.

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences, nutrition counselling.

Nutrition counseling is the assessment of an individual’s dietary intake after which, they are helped set achievable goals and taught various ways of maintaining these goals. The nutrition counselor provides information, educational materials, support and follow-up care to help an individual make and maintain the needed dietary changes for problems like obesity.

Obesity/ Food allergy

I assist people dealing with weight-related health problems by evaluating the health risks and help in obesity management. I also help patients manage various food allergies.

As a hepatologist, I specialize in the treatment of liver disorders, pancreas, gallbladder, hepatitis C, jaundice and the biliary tree. I also see patients suffering from pancreatitis, liver cancers alcoholic cirrhosis and drug induced liver disease(DILI), which has affected the liver.

Gastroenterology

As a gastroenterologist, my primary focus is the overall health of the digestive system. I treat everything from acid reflux to ulcers, IBS, IBD: Crohns disease and ulcerative colitis, and colon cancer.

Endoscopy is a nonsurgical procedure to examine a person’s digestive tract. It is carried out with an endoscope, a flexible tube with a light and camera attached to it so that the doctor can see pictures of the digestive tract on a color TV monitor.

Medical Gastroenterology

Gastroenterology is a specialty that evaluates the entire alimentary tract from the mouth to anus and involves studying the diseases of the pancreas.

Liver Transplant Services

A liver transplant is a surgical procedure that removes a patient’s non-functioning liver and replaces it with a healthy liver from a deceased donor or a portion of healthy liver from a living donor. It is reserved as a treatment option for people who have significant complications due to end-stage chronic liver disease or in case of sudden failure of a previously healthy liver.

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 13 April 2016

A case of advanced systemic sclerosis with severe GERD successfully treated with acotiamide

- Ryo Kato 1 ,

- Kiyokazu Nakajima 1 , 2 ,

- Tsuyoshi Takahashi 1 ,

- Yasuhiro Miyazaki 1 ,

- Tomoki Makino 1 ,

- Yukinori Kurokawa 1 ,

- Makoto Yamasaki 1 ,

- Shuji Takiguchi 1 ,

- Masaki Mori 1 &

- Yuichiro Doki 1

Surgical Case Reports volume 2 , Article number: 36 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

4017 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The majority of systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients have gastrointestinal tract involvement, but therapies of prokinetic agents are usually unsatisfactory. Patients are often compromised by the use of steroid; therefore, a surgical indication including fundoplication has been controversial. There is no report that advanced SSc with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is successfully treated with acotiamide, which is the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor designed for functional dyspepsia (FD). We report a 44-year-old woman of SSc with severe GERD successfully treated with acotiamide. She had received medical treatment in our hospital since 2003. She had been aware of the significant gastroesophageal reflux symptoms (e.g., heartburn, chest pain, and dysphagia) due to the development of esophageal hardening associated with SSc since 2014. As a result of upper gastrointestinal series, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and 24-h pH monitoring and frequency scale for the symptoms of the GERD (FSSG) scoring, she has been diagnosed with GERD associated with SSc. First of all, she started to take prokinetic agents Rikkunshito and mosapride and proton pump inhibitor; there was no change in reflux symptoms. So, we started to prescribe her the acotiamide.

After oral administration started, reflux symptoms have been improved. Five months after oral administration, FSSG score, a questionnaire for evaluation of the symptoms of GERD, was improved. Since its introduction of acotiamide, the patient has kept free from symptoms for 6 months.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a multisystem and chronic disease characterized by abnormalities of small blood vessels and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs. SSc, when advanced, is often compromised with severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which may be lethal in a worst-case scenario. A wide variety of medication has been used [ 1 – 5 ]; however, none of them are promising for patients with SSc. In addition, patients with SSc are often compromised by the use of steroid; therefore, a surgical indication including fundoplication has been controversial.

In this short communication, we describe our recent case of advanced SSc patients with severe GERD, who was successfully treated with a new drug originally designed for functional dyspepsia (FD).

Case presentation

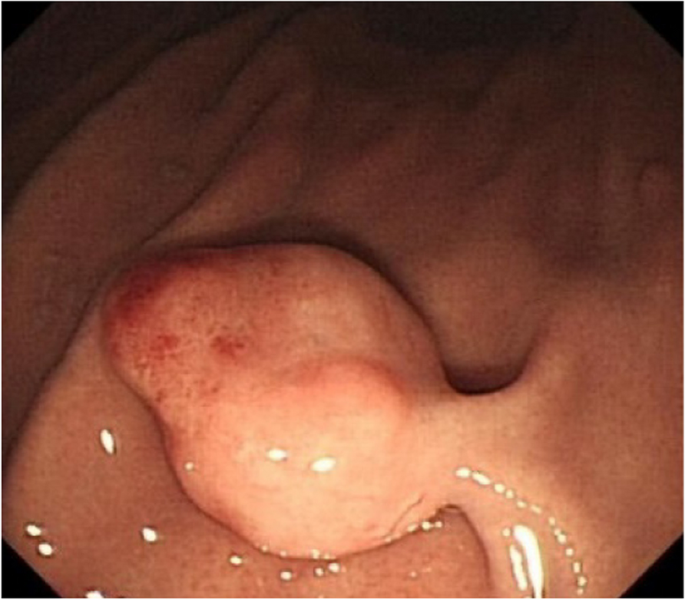

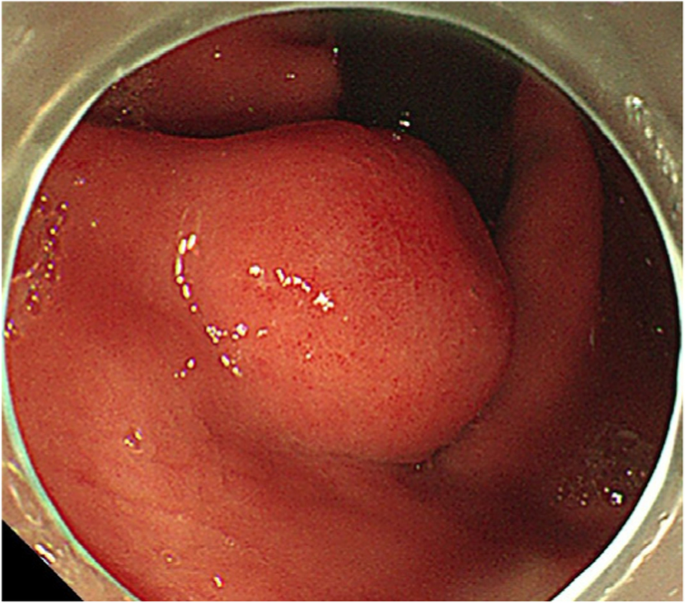

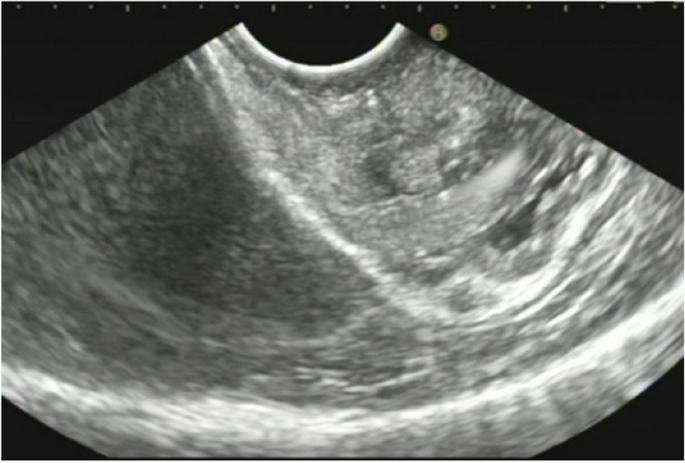

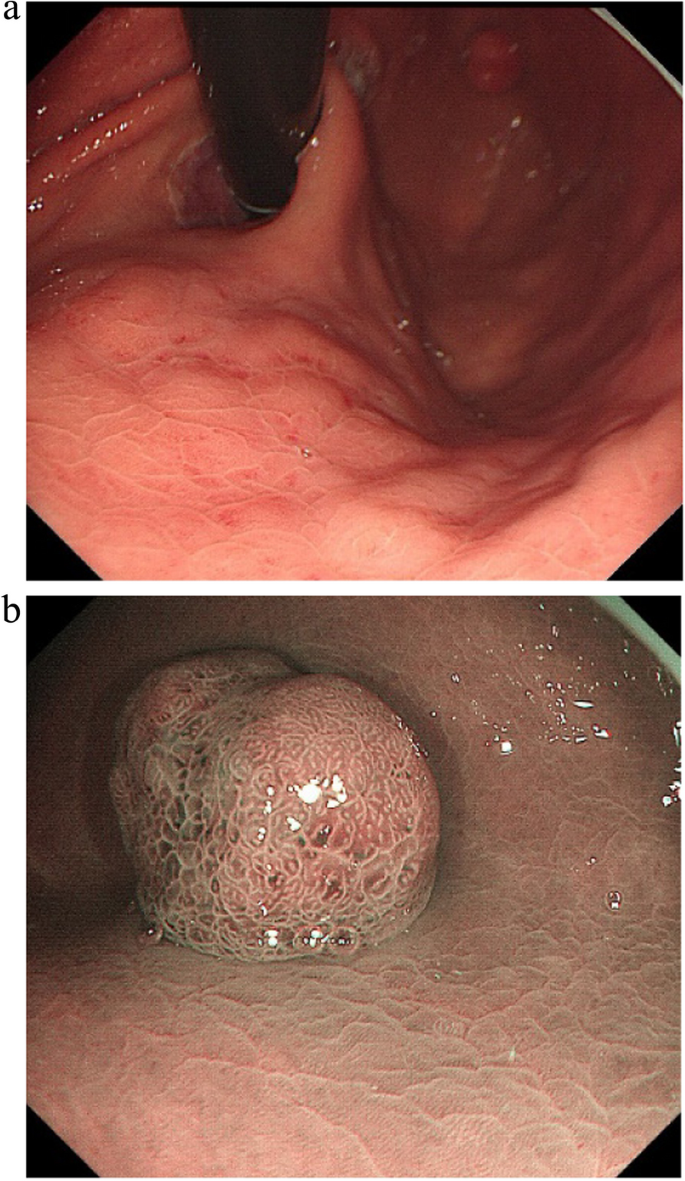

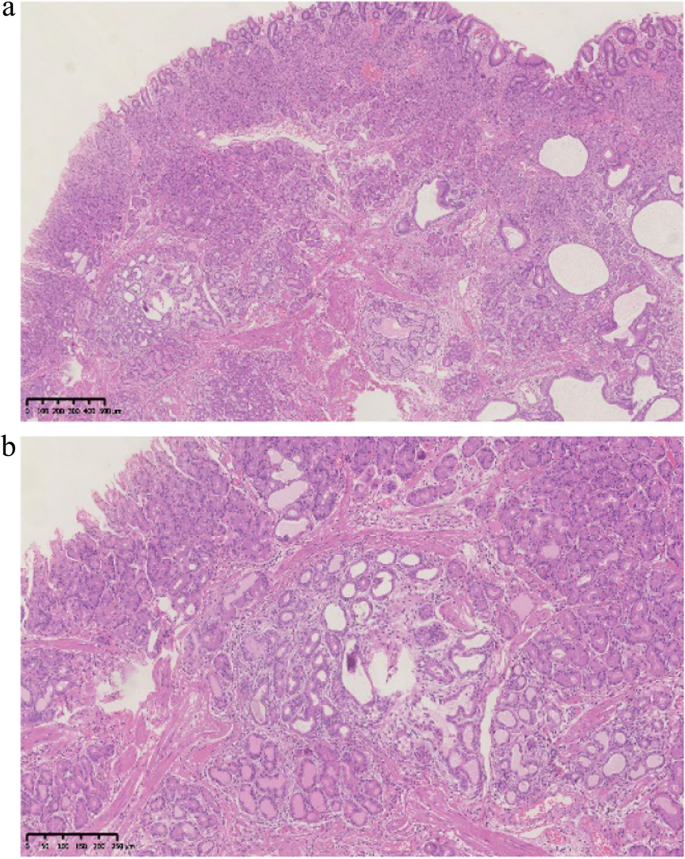

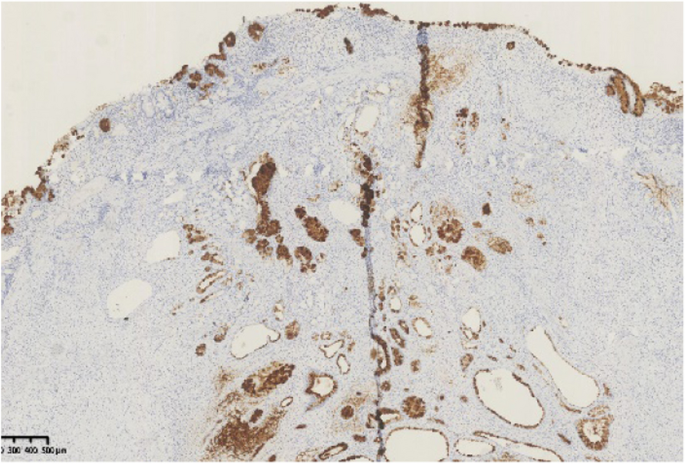

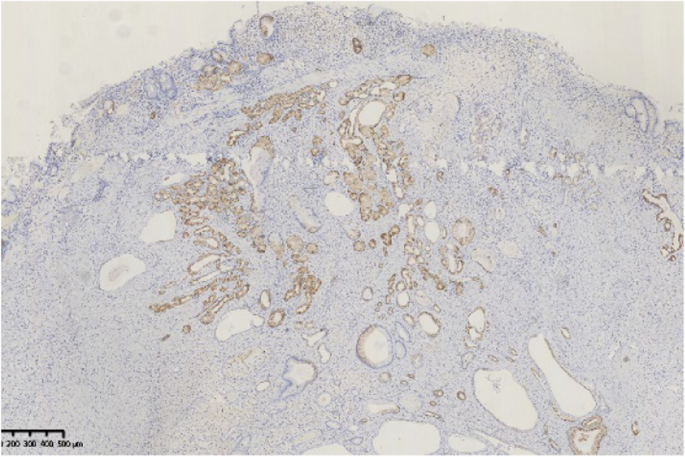

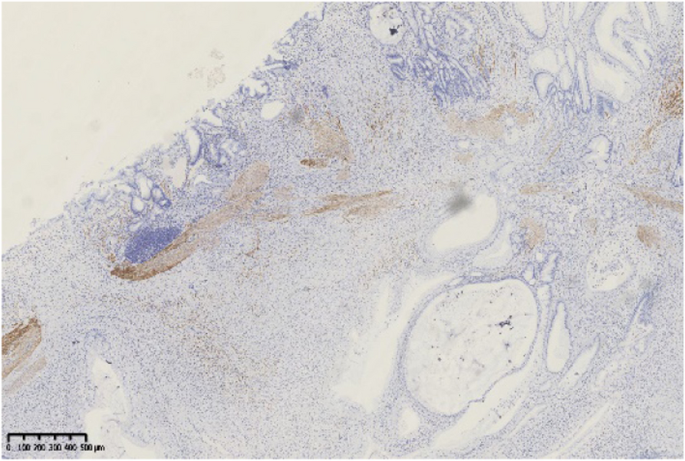

A 44-year-old woman of SSc had received medical treatment in our hospital since 2003. She had been aware of the significant gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and esophagus stasis due to the development of esophageal hardening associated with SSc since 2014. On physical examination, cachexia, a “mouse face” appearance and ulceration in the distal phalanges were identified. The abnormal build-up of fibrous tissue in the skin can cause the skin to tighten so severely that her fingers curl and lose their mobility (Fig. 1 ). Because she had been aware of the worsening of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, she received a medical examination from this department. Upper gastrointestinal series revealed no expansion and meandering esophagus, and reflux into the esophagus in the Trendelenburg position (Fig. 2 ). The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed reflux esophagitis of Los Angeles classification grade C and esophagus residue (Fig. 3 ).

The abnormal build-up of fibrous tissue in the skin can cause the skin to tighten so severely that fingers curl and lose their mobility in SSc

Upper gastrointestinal series revealed no expansion and meandering esophagus and reflux into the esophagus in the Trendelenburg position

The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed reflux esophagitis of Los Angeles classification grade C and esophagus residue

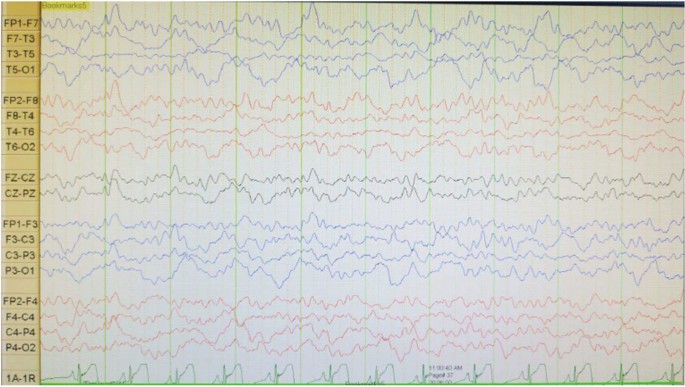

A 24-h esophageal pH monitoring revealed significant acid reflux: the number of refluxes was 81 times, pH was below 4.0 for 32.1 %, mean pH was 4.55, and DeMeester score (normal <14.75) was 117.5 (Fig. 4 ). Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (frequency scale for the symptoms of the GERD (FSSG)) score, a questionnaire evaluating the symptoms of GERD, was 34 points [ 6 ] (maximum 48 points). As a result of these tests, she has been diagnosed with GERD associated with SSc. Treatment with Rikkunshito and mosapride, which are prokinetic agents, and proton pump inhibitor was started. However, her symptoms were not improved. Therefore, we started the acotiamide on June 2015, which was a new drug originally designed for FD. Since then, her symptoms which were heartburn, burp, and nausea after a meal were improved. Five months after acotiamide was started, the FSSG score was reduced to 21 points (Fig. 5 ). However, the results of 24-h esophageal pH monitoring showed worsening acid reflux: the number of refluxes was 152 times, pH was below 4.0 for 60.5 %, mean pH was 3.73, and DeMeester score (normal <14.75) was 211.6 (Fig. 4 ). The upper gastrointestinal series and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy did not change.

A 24-h pH monitoring was performed before and after acotiamide oral administration. These four items showed worsening before and after the administration

After oral administration of acotiamide, FSSG score was improved from 34 points to 21 points

Since the introduction of acotiamide, the patient has been free from symptoms to date.

In 1994, Sjogren proposed a progression of SSc with gastrointestinal involvement, vascular damage, neurogenic impairment, and myogenic dysfunction with the replacement of normal smooth muscle by collagens fibrosis and atrophy [ 7 ]. It is distinguished in diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc) or limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc) whether skin hardening exceeds an elbow or a knee [ 8 ]. Next to the skin, the gastrointestinal tract is the second most common site of SSc organ damage that can affect patients with lcSSc and dcSSc [ 9 ]. It affects the gastrointestinal tract in more than 80 % of patients. Reflux esophagitis is found in 50–90 % of SSc patients [ 7 , 10 ].

The common characteristics of GERD seen in SSc patients are as follows. The upper GI series often shows peristaltic decrease and expansion of the lower esophagus. The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy shows linear redness and erosion of the lower esophagus caused by the reflux, which often merges with the Barett esophagus. In addition, the merger frequency of esophageal cancer is often in SSc. Esophageal dysmotility leads to impaired acid clearance, and 24-h monitoring shows prolongation of esophageal exposure time to gastric acid [ 11 ].

Its treatment, either medical or surgical, has been still challenging. The major medical treatment option includes use of histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) and/or proton pomp inhibitor (PPI) for the purpose of controlling stimulation and inflammation of the esophageal mucosa by the gastric acid reflux [ 12 – 14 ]. Surgery, e.g., Nissen fundoplication, can be considered for drug-resistant reflux disease [ 15 ]. These medical/surgical treatments have been shown not as promising as those for reflux patients without SSc [ 16 ].

The last option for SSc patients with severe GERD is a group of prokinetic drugs. A wide variety of prokinetic agents have been used, such as mosapride citrate, metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin, octreotide, and dinoprost [ 1 – 5 ]. However, therapies of traditional prokinetic agents are usually unsatisfactory for severe GERD patients.

Acotiamide is the novel prokinetic agent basically designed for FD; it is the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor. FD is a chronic disorder of sensation and movement (peristalsis) in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The acetylcholine (Ach) is released from cholinergic nerve terminals and lets the gastrointestinal tract shrink by binding to the muscarinic receptor of the gastrointestinal smooth muscle. It is thought that the Ach is broken down immediately by AChE and enterokinesis is regulated by this reaction. Acotiamide inhibits AChE and regulates the resolution of Ach. As a result, it increases the quantity of ACh available in the synaptic cleft and therefore improves enterokinesis [ 17 ].

We have prescribed a variety of traditional prokinetic agents, without obtaining even temporary relief of her symptoms. Therefore, we prescribed acotiamide. We performed upper gastrointestinal series, gastrointestinal endoscopy, 24-h pH monitoring, and the quality of life (QOL) scores for the assessment of gastroesophageal reflux before and after oral administration of acotiamide on this patient. No changes were observed before and after treatment in the upper GI series and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Acotiamide does not show the emission promoting effect on the normal gastric emptying in rats. However, prior research reports that acotiamide does improve the gastric emptying during restraint stress. Acotiamide might have led to symptom improvement due to the suppressed response to stress by decreasing the expression of NmU, a stress-related gene in the hypothalamus, via the vagus nerve [ 18 ].We think this may be a partial reason why our patient showed improvement of her GI symptoms.

In the 24-h pH monitoring, DeMeester score even showed a worsening from 117 to 211. However, FSSG, which is one of the established QOL scoring system, showed improvement from total 34 to 21 points. FSSG is a questionnaire composed of 12 questions and classified into two groups, which are five items related to “dysmotility” symptoms and seven items to “acid reflux” symptoms. In our case, the score related to both symptoms were improved from 17 to 10 points and 17 points to 11 points, respectively. As we describe later, these improvements can be explained by the pharmacological effects of acotiamide on both the gastric and the esophageal functions.

In fact, this patient was clearly aware of the improvement of clinical symptoms, and QOL has been improved.

In our case, traditional prokinetic agents attempted prior to acotiamide were not effective. Only acotiamide showed substantial relief of the patient’s symptom. We speculated this might be because of these two factors: (1) pharmacologically, acotiamide may not only affect the gastric emptying but also improve fundic accommodation of adaptive relaxation, and (2) acotiamide may directly act on the esophageal body and improve esophageal peristalsis. The authors have reached the above speculation based on the results of FSSG score: improvements of early satiety and chest discomfort. The question score “Do you feel full while eating meals?” was improved from 4 points to 2 points and “Do some things get stuck when you swallow?” was improved from 3 points to 2 points, respectively.

We just experienced one case; therefore, further accumulation of similar cases is definitely required. In our case, no objective improvement was observed on classical 24-h pH monitoring. The authors believe this examination might not be appropriate as an evaluation tool of GERD in patients with severe esophageal motor dysfunction like advanced SSc patients. Novais et al. reported that the 24-h abnormal pH tracings were classified into three types: (i) 24-h abnormal pH, with a true GERD pattern, i.e., sharp sudden pH drops, reaching values below 3 and then returning to usual esophageal pH (pH 6–7) (Fig. 6 a); (ii) 24-h abnormal pH with a pattern suggesting esophageal fermentation due to retained food, i.e., steady drop of pH not reaching values below 3.0 (Fig. 6 b); and (iii) negative 24-h pH, i.e., presence of physiological reflux (reflux episodes occurring in less than 4.5 % of total examining time) or zero reflux (absence of any episode of pH lower than 4.0) [ 19 ]. In a 24-h pH monitoring after acotiamide was started, there were many frequent waveforms of (ii) than those of (i). The esophageal food fermentation may have affected the results of this case. The QOL score, including FSSG is likely to accurately reflect the symptoms of patients than 24-h pH monitoring. Future tasks are to perform a detailed study by using a new method of measuring such as high resolution manometry.

A 24-h pH tracing of this patient. True gastroesophageal reflux ( a ) and fermentation ( b )

Conclusions

We have experienced a case of advanced SSc with severe GERD successfully treated with acotiamide. Acotiamide might become a help of advanced SSc with severe GERD patient whose surgical indication has been controversial.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

acetylcholine

acetylcholinesterase

functional dyspepsia

frequency scale for the symptoms of the GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- systemic sclerosis

Johnson DA, Drane WE, Curran J, Benjamin SB, Chobanian SJ, et al. Metoclopramide response in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Effect on esophageal and gastric motility abnormalities. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1597–1601.1.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Smout AJ, Bogaard JW, Grade AC, ten Thije OJ, Akkermans LM, et al. Effects of cisapride, a new gastrointestinal prokinetic substance, on interdigestive and postprandial motor activity of the distal oesophagus in man. Gut. 1985;26:246–51.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Soudah HC, Hasler WL, Owyang C, et al. Effect of octreotide on intestinal motility and bacterial overgrowth in scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1461–7.

Dull JS, Raufman JP, Zakai MD, Strashun A, Straus EW, et al. Successful treatment of gastroparesis with erythromycin in a patient with progressive systemic sclerosis. Am J Med. 1990;89:528–30.

Tomomasa T, Kuroume T, Arai H, Wakabayashi K, Itoh Z, et al. Erythromycin induces migrating motor complex in human gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:157–61.

Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S, et al. Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:888–91.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sjögren RW. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1265–82.

LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(2):202–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Clements PJ, Becvar R, Drosos AA, Ghattas L, Gabrielli A. Assessment of gastrointestinal involvement. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21:S15–8.

Young MA, Rose S, Reynolds JC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1996;22(4):797–823.

Tasleem A, Qazi M, Jaswinder S, et al. Assessment of esophageal involvement in systemic sclerosis and morphea (localized scleroderma) by clinical, endoscopic, manometric and pH metric features: a prospective comparative hospital based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:24.

Petrokubi RJ, Jeffries GH. Cimtidine versus an acid in scleroderma with reflux esophagitis: a randomized double-blind controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:691–5.

Hendel L, Aggestrup S, Stentoft P. Long-term ranitidine in progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) with gastroesophageal reflux. Scan J Gastroenterol. 1986;21:799–805.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wigley FM, Sule SD. Novel therapy in the treatment of scleroderma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2001;10:31–48.

Cicala M, Emerenziani S, Guarino MP, Ribolsi M. Proton pump inhibitor resistance, the real challenge in gastro-esophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(39):6529–35.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Carlson DA, Hinchcliff M, Pandolfino JE. Advances in the evaluation and management of esophageal disease of systemic sclerosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(1):475.

Kawachi M, Matsunaga Y, Tanaka T. Acotiamide hydrochloride (Z-338) enhances gastric motility and emptying by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase activity in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;666:218–25.

Seto K et al. Acotiamide, hydrocholoride (Z-338), a novel prokinetics agent, restores delayed gastric emptying and feeding inhibition induced by restraint stress in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(9):1051–9.

Novais PA, Lemme EMO. 24-h pH monitoring patterns and clinical response after achalasia treatment with pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1257–65.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, 2-2, E-2, Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka, 565-0871, Japan

Ryo Kato, Kiyokazu Nakajima, Tsuyoshi Takahashi, Yasuhiro Miyazaki, Tomoki Makino, Yukinori Kurokawa, Makoto Yamasaki, Shuji Takiguchi, Masaki Mori & Yuichiro Doki

Division of Next Generation Endoscopic Intervention (Project ENGINE), Global Center for Medical Engineering and Informatics, Center of Medical Innovation and Translational Research, Osaka University, 2-2, Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka, 565-0871, Japan

Kiyokazu Nakajima

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kiyokazu Nakajima .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the management of the patient in this case report. KN is a chief surgeon of our hospital and supervised the case and also supervised the writing of the manuscript. YD is a chairperson of our department and supervised the entire process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ryo Kato is the first author.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kato, R., Nakajima, K., Takahashi, T. et al. A case of advanced systemic sclerosis with severe GERD successfully treated with acotiamide. surg case rep 2 , 36 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-016-0162-5

Download citation

Received : 14 January 2016

Accepted : 06 April 2016

Published : 13 April 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-016-0162-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- functional dyspepsia (FD)

- frequency scale for the symptoms of the GERD (FSSG)

- Cell Biology

Case Study: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

Gerd Case Study and Pharmacotherapy

This document presents a case study of a 60-year-old male patient admitted to the hospital with abdominal discomfort for 10 days and a history of bronchial asthma and GERD. Examination findings and investigation reports are provided. The patient is assessed and diagnosed with bronchial asthma and GERD. A drug chart outlines the treatment plan and discharge summary is presented advising the patient to continue medications and make lifestyle modifications. The case study concludes with a discussion of monitoring parameters, pharmacist interventions, and patient counseling on drug therapy and disease and lifestyle management. Read less

Recommended

More related content, what's hot, what's hot ( 20 ), similar to gerd case study and pharmacotherapy, similar to gerd case study and pharmacotherapy ( 20 ), recently uploaded, recently uploaded ( 20 ).

- 1. PHARMACOTHERAPEUTICS-III CASE PRESENTATION NANDHA COLLEGE OF PHARMACY RAJNANDINI SINGHA IV Pharm D

- 2. CASE STUDY ON GERD

- 3. SUBJECTIVE A 60 year old Male patient was admitted in Perundarai medical college hospital on 25/1/2018 with the complaints of abdominal discomfort for 10 days.

- 4. HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS H/O Abdominal discomfort H/O Difficulty in breathing H/O skin allergy H/O cough with expectoration

- 5. PAST HISTORY K/C bronchial asthma before 3 days

- 6. PERSONAL HISTORY Diet: Mixed.

- 7. GENERAL EXAMINATION Patient conscious, oriented BP :160/70 mmHg PR :79 bpm

- 8. SYSTEMIC EXAMINATION CVS – S1S2 Heard RS - B/L AE+,B/L WHEEZ+ CNS – NFND P/A - Soft

- 9. OBJECTIVE INVESTIGATION CHART NAME OF INVESTIGATION OBSERVED VALUE NORMAL VALUE WBC 14.0x109/L 4.5-10.5×109/L RBC 4.26x1012/L 3.8-5.9×1012/L HAEMOGLOBIN 10.5g/dl 12-14g/dl PLATELETS 173.0109/L 130-400109/L L/M/G 2.5/1.5/11.0109/L MCV 92.9 FL 80-100FL HCT 40.2% 35-50% MCH 27.6pg 27- 34pg

- 10. MCHC 29.7g/dl 32-36g/dl ESR 32mm/hr 0-20mm/hr BIOCHEMISTRY RBS 67 mg/dl Up to 140 mg/dl BLOOD UREA 30 mg/dl 10-40 mg/dl SERUM CREATININE 1.0mg/dl 0.6-1.3 mg/dl SERUM PHOSPHATE 3.5 mg/dl 2.5-4.5 mg/dl URINE ANALYSIS COLOUR PALE YELLOW REACTION Acidic ALBUMIN NIL

- 11. PROGRESS CHART DATE TEMP (°F) B.P P.R R.R 25/1/18 98.4 110/80 80 20 26/1/18 98.4 110/80 75 22 27/1/18 98.8 100/80 84 20 28/1/18 98.6 140/60 82 20 29/1/18 98.4 110/80 78 22 30/1/18 99 140/80 82 20 31/1/18 98.5 120/80 80 20 1/1/18 98.7 140/80 85 22 2/1/18 98.4 120/80 82 22

- 12. OTHER INVESTIGATION X-RAY –Increased BVM (bronchovascular marking)

- 14. ASSESMENT FINAL DIAGNOSIS: Bronchial Asthma GERD( Gastroesophageal reflux disease)

- 15. DRUG CHART DRUG GENERIC NAME DOSE ROUTE FREQ 3 4 5 6 7 Inj.genta Gentamycin 1mg IV 1-0-1 √ √ √ √ √ INJ .RANTAC Ranitidine 2ml IM 1-0-0 √ √ √ √ √ T.CPM Chlorphenaramin e 10mg PO 1-0-1 √ √ √ √ √ T. Dolo Paracetamol 650mg PO 1-1-1 √ √ √ √ √ Inj. Deri Theophylline+Eto phylline 2ml IV 1-0-1 √ √ √ √ √ T.celin Vitamin C 40mg PO 1-0-0 √ √ √ √ √ SYRUP. Rantac ranitidine 15mg PO 1-0-1 √ √ √ √ √ Liquid paraffin Liquid paraffin 10ml topical 0-0-1 √ √ √ √ √

- 16. DRUG GENERIC NAME DOSE ROUTE FREQ 3 4 5 6 7 BVM OINTMENT Betamethasone valarate 0.1% 1-1-1 topical √ √ √ √ √ SYRUP. REXCOF Dextromethophan and chlorpheniramine maleate 100ml 1-0-1 PO √ √ SALBUTAMOL NEB SUBUTAMOL 1-1-1 NASAL √ √ √ √ √

- 17. DISCHARGE SUMMARY The patient was discharged on 7/02/18 DISCHARGE ADVICE T.PARACETAMOL(1-1-1) 650mg T.CPM(1-0-1)10mg SYRUP.RANTAC(1-1-1)10ml T.CELIN(VITAMIN C) (1-0-0)500mg Liquid paraffin(1-0-1) BVM OINTMENT(1-0-1)

- 19. PATIENT COUNSELLING: DRUG RELATED DISEASE RELATED LIFE STYLE MODIFICATION •Take SYRUP Rantac before 30mins of food •LIQUIID PARAFFIN and BVM OINTMENT should be apply on dry skin. • Advice the patient not to skip meals. •Avoid stress and NSAIDS • Elevate the head on the bed. COPD: On coughing mouth should be closed. Avoid dust, allergen, alcohol, smoking. •Avoid choclate, coffee, soda, alcoholic drinks. • Avoid Citrus fruits and juices of tomato. •Advice the patient to eat boil food for 2-3 weeks. •Green vegetables should be taken to regenerate the lining of stomach.

- 20. S.N O ASSESMENT PLAN 1. Chlorpheniramine + food Alcohol can increase the CNS Side effect such as drowsiness, dizziness .. MANAGEMENT: To avoid consumption of alcohol , hazardous activities require complete alterness ,mental alertness. Syrup Ranitidine should administered 30mins before food. 3. T.CPM AND SYRUP .Rexcof Side effect - sleepiness Do not prescribe in the morning

- 21. MONITORING PARAMTER: pH Monitoring for GERD Increased acid exposure time.

- 22. PHARMACIST INTERVENTION: Antacid should be recommended in the prescription. Suggesting to Reduce the adminstration of PARACETAMOL to reduce toxicity. Proton pump inhibitor is recommended to be add in the prescription.

- 23. THANK YOU

Case Studies

CR, a 44-year-old man, comes to the pharmacy looking for a remedy for his heartburn. He reports that his heartburn has been bothering him for the past few weeks, and he complains of an acidic taste in his mouth and a burning feeling in his throat about twice a week. CR does not complain of any other related symptoms, such as pain when swallowing. CR has a box of omeprazole (Prilosec) in his hand. He asks if it would be the best product to help alleviate his symptoms.

As the pharmacist, how would you respond?

EF is a 30-year-old woman who comes to the pharmacy with dry, demarcated lesions in linear streaks, with some vesicles, on her hands, arms, and face. She says she was gardening yesterday for a few hours and must have touched poison ivy. EF says she tried to hide it with makeup to go to work this morning, but it only made it worse. She exclaims, “I cannot stand the itching anymore.” Upon questioning, you find out that she has had similar lesions before, but they were less extensive and not as bothersome. EF asks if there is pharmacy product that could help. She has no significant medical history and is not taking any prescription or OTC medications.

As the pharmacist, what would you recommend?

Case 1: Based on his reported symptoms, CR likely suffers from mild/ episodic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), so he is a candidate for self-treatment. OTC proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) such as omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole are appropriate for self-treatment of GERD for up to 14 days. However, before you recommend these products, you should educate CR that OTC omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole are not intended for immediate relief of heartburn. These drugs have a slow onset but a long duration of action, and CR may have to take one of these drugs for 1 to 4 days before he feels better. CR should be cautioned to speak to his doctor if his symptoms do not resolve after 2 weeks or his heartburn worsens.

Alternatively, CR could try a histamine2 (H2)-receptor antagonist such as ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine, or nizatidine. H2-receptor antagonists have a different mechanism of action than PPIs and provide relief of heartburn more quickly than PPIs. H2-receptor antagonists can be taken prophylactically before meals to prevent GERD.

CR might also consider taking an antacid, including calcium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, magnesium hydroxide/aluminum hydroxide, or bismuth subsalicylate. These agents have the fastest onset of action, but they provide only symptomatic relief of heartburn and have the shortest duration of action.

Case 2: Allergic contact dermatitis is an inflammatory skin reaction to a foreign substance, such as urushiol in the sap of the poison ivy plant. Sensitized patients can develop clinical symptoms such as erythema, intense itching, and formation of plaques and vesicles within 4 to 96 hours after exposure to an allergen.

EF appears to have severe contact dermatitis. She is not a candidate for self-treatment because of the facial involvement of her dermatitis and the presence of vesicles and intense itching. If left untreated, allergic contact dermatitis resolves within 1 to 3 weeks; however, it can cause significant discomfort. EF should be referred to her primary care provider to obtain a prescription for an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone to decrease itching, and perhaps a high-potency topical corticosteroid such as clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream, which is generally not applied to the face. A 21-day course of oral prednisone (starting at 1 mg/kg/day and tapered over 3 weeks) is appropriate and can significantly reduce symptoms, including itching.

EF should be told to keep the area clean and to avoid scratching and using makeup, as they can irritate the skin. In addition, nonpharmacologic treatments, including the application of cold compresses, can be recommended. EF might try using astringents such as aluminum acetate (Burrow’s solution) or calamine to reduce inflammation and promote drying, and healing of the lesions.

Read the answers

function showAnswer() {document.getElementById("answer").style.display = 'block';document.getElementById("link").style.display = 'none';}

Dr. Coleman is professor of pharmacy practice, as well as codirector and methods chief at Hartford Hospital Evidence-Based Practice Center, at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy.

Condition Watch: Asthma

HSSP Model Can Reduce Financial Toxicity of Oral Oncology Treatment

SGLT2 Inhibitors Show Considerable Efficacy for Diabetes Management

Case Study: Advise Patients on Eligibility, Efficacy of Zoster Vaccine

Counsel Patients About Self-Care Measures, OTC Treatments for Seasonal Allergies

The Fludarabine Shortage and Its Ripple Effects: Navigating the Crisis

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Prev Nutr Food Sci

- v.26(4); 2021 Dec 31

Dietary Intake in Relation to the Risk of Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review

Neda heidarzadeh-esfahani.

1 Student Research Committee, School of Nutritional Sciences and Food Technology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah 6719851552, Iran

Davood Soleimani

2 Research Center of Oils and Fats, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah 6719851552, Iran

3 Nutritional Sciences Department, School of Nutrition Sciences and Food Technology, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah 6719851552, Iran

Salimeh Hajiahmadi

4 Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd 8916188635, Iran

Shima Moradi

5 Department of Nutritional Sciences, Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health (RCEDH), Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah 6719851552, Iran

Nafiseh Heidarzadeh

6 Depertment of Genetics, Faculty of Basic Sciences, Shahrekord University, Shahrekord 881863414, Iran

Seyyed Mostafa Nachvak

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic condition which has a high global prevalence. Dietary intake is considered to be a contributing factor for GERD. However, scientific evidence about the effect of diet on the risk of GERD is controversial. This systematic review was conducted to address this issue. A comprehensive structured search was performed using the MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science databases up to August 2020, in accordance with the PRISMA statement. No restrictions were set in terms of language, time of publication, or study location. Study selection and data abstraction was conducted independently by two authors, and risk of bias was assessed using a modified Quality in Prognosis Studies Tool. Eligible studies evaluating the impact of food and dietary pattern on GERD were included in qualitative data synthesis. After excluding duplicate, irrelevant, and low quality studies, 25 studies were identified for inclusion: 5 case-control studies, 14 cross-sectional studies, and 6 prospective studies. This review indicates that high-fat diets, carbonated beverages, citrus products, and spicy, salty, and fried foods are associated with risk of GERD.

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common disorder that affects quality of life. GERD develops when reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and long-term complications ( Rajaie et al., 2020 ). The major symptoms of GERD include heartburn and regurgitation ( Kahrilas, 2003 ), however, GERD can also manifest with atypical symptoms including epigastric pain, dyspepsia, nausea, bloating, and belching ( Badillo and Francis, 2014 ). GERD pathogenesis involves esophagitis, hemorrhage, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma ( Rajaie et al., 2020 ). Moreover, GERD is independently associated with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, including acute myocardial infarction ( Lei et al., 2017 ). It is a global disease, with an estimated highest incidence in North America (18.1%∼27.8%), followed by the Middle-East America (8.7%∼33.1%), Europe (8.8%∼25.9%), and East Asia (2.5%∼7.8%) ( Seremet et al., 2015 ).

GERD is a multifactorial disease influenced by both genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Diet (an environmental factor) has important roles in gastrointestinal and cardio metabolic disorders ( Argyrou et al., 2018 ; Heshmati et al., 2019 ; Surdea-Blaga et al., 2019 ; Heshmati et al., 2020 ), and modifiable risk factors included long meal-to-sleep intervals, speed of eating, and scale and temperature of foods ( Esmaillzadeh et al., 2013 ; Yuan et al., 2017 ). Intake of alcohol, chocolate, and high-fat meals reduces esophageal sphincter pressure and increases esophageal exposure to gastric juices ( Kaltenbach et al., 2006 ). Some studies have reported that both the quality and quantity of carbohydrates in diet may be associated with GERD ( Keshteli et al., 2017 ; Wu et al., 2018 ). However, current data are contradictory ( Kim et al., 2014 ).

Emerging data indicates that appropriate eating behaviors, i.e., healthy diets involving high intakes of fruits and whole grains ( Wu et al., 2013 ), such as the Mediterranean diet ( Mone et al., 2016 ), improves GERD symptoms. Therefore, improving diets can decrease the occurrence of GERD and should be considered a cost-effective strategy instead of pharmacotherapy.

Review studies have investigated predictors of GERD risk in terms of food related factors such as probiotics ( Cheng and Ouwehand, 2020 ) and food components ( Surdea-Blaga et al., 2019 ). However, to our knowledge, no systematic reviews have been conducted to assess the impact of diet on risk of reflux disease. We conducted a systematical review of articles investigating the association between food and dietary patterns with GERD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy.

The literature search was conducted by two independent researchers using electronic databases, including the Web of Sciences, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Scopus, to identify relevant publications up to August 2020. This study was given ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of Research Council of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Code: IR.KUMS.REC.1399.941).

We performed the systematic search using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) along with non-MeSH keywords in the title and abstract as follows: “Diet” OR “Food” OR “Dietary Pattern” OR “Food Pattern” AND “Gastroesophageal Reflux” OR “Gastric Acid Reflux” OR “Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease” OR “GERD” OR “Esophageal Reflux” OR “Pyrosis” OR “Pyroses” OR “Heartburn” OR “Barrett’s Esophagus”. We did not consider any restrictions in terms of language, time of publication, and study location.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies were performed on adults and evaluated all components of the dietary patterns and risk of reflux disease. In addition, we considered all observational studies, including cross-sectional, case-control, prospective, and retrospective studies. Interventional studies were not included in this study since the duration of exposure was short. Overall, 991 articles were identified during the initial search and duplicate studies (n=26) were removed. The remaining studies were screened based on topic and 833 irrelevant studies were excluded. Thereafter, 119 studies were reviewed in more detail, and 24 classed as irrelevant (including 17 that did not assess dietary pattern) and 52 that did not evaluate our outcome (“reflux diseases”) were excluded. In addition, the qualification of 26 articles were evaluated and one study was excluded because of low quality. In total, 25 articles were eligible for inclusion in this review study ( Fig. 1 ).

Flow chart of the search and publication selection.

Quality assessment

Using all the data extracted, we scored the risk of bias of the selected studies on a six-point scale using a modified version of the Quality in Prognosis Studies ( Hayden et al., 2006 ). Using this system, we assessed the quality of individual studies using the following criteria (one point per criterion): (I) study participation (the study sample represents the key characteristics of the population of interest sufficiently well to limit potential bias to the results); (II) study attrition (loss to follow-up is not associated with key characteristics); (III) prognostic factor measurement (prognostic factors of interest are measured in study participants in such a way that potential bias is limited); (IV) confounding measurement and account (outcomes of interest are measured in study participants in such a way that potential bias is limited); (V) outcome measurement (important potential confounders are appropriately accounted for, limiting potential bias with respect to the prognostic factor of interest); and (VI) analysis (the statistical analysis is appropriate for the design of the study, and limits the potential for invalid results). Studies with a score between 0 and 3 points were considered to be of low quality, while studies with a score >3 to 6 were considered to be of high quality.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two researchers using a data collection checklist. Any disagreement has been discussed and resolved accordingly. For each article, the first author’s name, publication year, study design (trial/prospective/cross-sectional/case control), sample size, study population demographics [age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and country], dietary assessment tools, dietary components, and outcomes (all reported data on association between GERD and dietary components) were extracted. All data are presented in the Results.

Study characteristics