An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(9); 2022 Sep

An Atypical Presentation of Crohn's Disease: A Case Report

Asfand yar cheema.

1 Medicine, Services Hospital Lahore, Lahore, PAK

2 Internal Medicine, Lahore Medical & Dental College, Lahore, PAK

Mishaal Munir

3 Medicine, Ghurki Trust & Teaching Hospital, Lahore, PAK

Kaneez Zainab

4 Internal Medicine, Mayo Hospital, Lahore, PAK

Oboseh J Ogedegbe

5 Internal Medicine, Lifeway Medical Center, Abuja, NGA

Crohn’s disease (CD) is an inflammatory bowel disease affecting any portion of the gastrointestinal tract, usually the terminal ileum and the colon, with clinical manifestations such as diarrhea, fever, and weight loss. Clinical presentation of CD may include complications such as enterovesical fistulas, abscesses, strictures, and perianal disease. CD also classically presents with “skipping lesions,” unlike ulcerative colitis (UC), which presents with continuous lesions. It can manifest with a wide range of extra-intestinal symptoms such as pyoderma gangrenosum, aphthous stomatitis, episcleritis, uveitis, and arthritic disease. Such a wide range of presentations leads to diagnostic difficulties, as seen in this case. Treatment modalities include steroids, antibiotics, and surgical removal of affected parts, depending on the extent of the disease. Here, we present a case of a young male who presented with manifestations of mesenteric lymphadenitis and had an intraluminal cecal mass causing obstructive symptoms, and was subsequently diagnosed with CD.

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is one of the two major inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), more prevalent in developed countries. The incidence of CD is 0.1-0.6 cases per 100,000 patients per year, seen equally amongst males and females [ 1 , 2 ]. The disease typically presents in early adulthood, with frequent abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and weight loss. However, symptoms vary from person to person and can range from mild to severe, depending on the severity and location of the inflammation. Several genes have been studied as etiological factors implicated in CD and, thus far, strong and replicated associations have been identified with NOD2 , IL23R , and ATG16L1 genes [ 3 ]. Numerous etiologies of the disease have been proposed, including various environmental factors, autoimmunity, genetics, and gut microbiome derangement. CD can frequently aggravate and cause multiple complications, including fistulas, abscesses, obstruction, and internal bleeding. Prognostic factors for complications and a thorough series of investigations done for diagnosing CD hold significant importance in guiding therapeutic decisions. Being a chronic inflammatory condition with granulomatous inflammation, diffuse mesenteric lymphadenopathy with an intraluminal mass remains a rare initial presentation of CD.

Case presentation

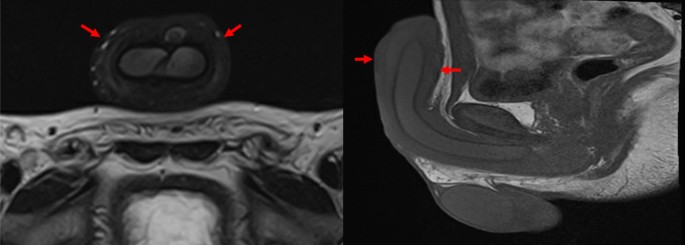

We present a case of a 25-year-old male with no significant past medical history, who presented to the emergency department (ED) with severe diffuse abdominal pain, which was colicky in nature, sudden in onset, 7/10 in intensity. He had nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite as well. Specific investigations, including complete blood count and serum electrolytes, were carried out, and the results were normal. The patient was an avid smoker for nine years with a history of smoking one cigarette pack per day. Gastroenteritis was suspected. Thus, he was given intravenous normal saline stat, intravenous omeprazole, and intravenous baclofen in the ED and was discharged on oral medication, which included ciprofloxacin 500 mg once daily, metronidazole 400 mg thrice daily, and omeprazole 40 mg once daily for a week. One month later, he presented again to the ED with right iliac fossa pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of weight, loss of appetite, and constipation for two days. On physical examination, there was pain on deep palpation while rebound tenderness, rigidity, and guarding were absent. Investigations including complete blood count (CBC), liver function test (LFT), serum amylase, and lipase levels were ordered, and apart from mild leukocytosis and slightly elevated erythrocyte sedimentary rate (ESR), results came back normal. After reviewing labs and imaging results, a stool sample was sent for calprotectin level, which was >1000.0 ug/g, while the fecal occult blood test was negative. Computed tomography (CT) scan, as shown in Figure Figure1, 1 , showed diffuse long-segment mucosal thickening in the distal ileum, extending over 12cm, as well as enlarged lymph nodes in the right side of the bowel (depicted by the arrow in the figure).

Arrow shows several enlarged lymph nodes on the right side of the bowel.

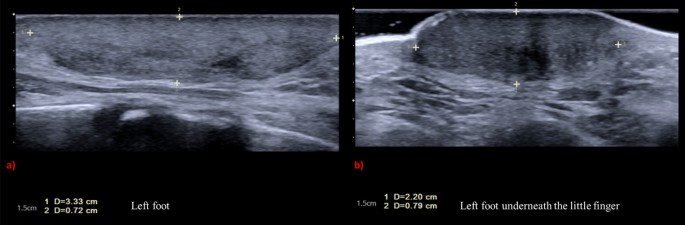

At this time, differential diagnoses included CD, intestinal lymphoma, Castleman disease, and intestinal tuberculosis. A colonoscopy done for further evaluation showed a friable, nodular ulcerated ileocecal region with complete occlusion of the ileocecal valve and surrounding mucosal edema, as shown in Figure Figure2 2 (A, B). However, the scope could not be passed beyond the ileocecal valve.

(A) and (B) show the cecum and ileocecal valve, with mucosal edema and ulceration, and a completely occluded ileocecal junction. The scope could not be passed beyond this point.

(C) shows the rectum and (D) shows the anorectal junction. Both are normal.

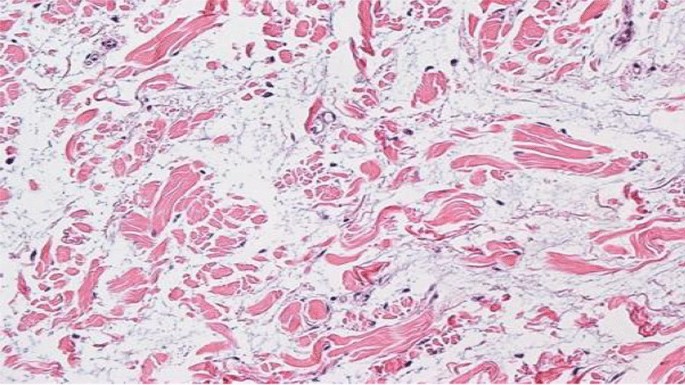

Biopsy reports did not show any specific findings. Due to the deteriorating condition of the patient, a laparoscopic modified right-sided hemicolectomy was performed. Surprisingly, a hard stony nodular mass measuring 2 cm was present at 11 cm from the proximal ileal resection margin, 7 cm from the distal colonic resection margin, and 5.3 cm from the mesenteric resection margin. The mass was predominantly located on the mesenteric border. The specimen was sent for histopathology evaluation and showed acute and chronic transmural inflammation at the cecum along with focal mucosal ulceration and rare non-caseating granulomas (Figure 3 ).

Yellow arrow indicates an area of dense plasma cell and lymphocytic infiltrate; Black arrow indicates intraepithelial lymphocytes.

Twenty-one reactive mesenteric lymph nodes were noted, along with a few lymph nodes showing non-caseating granulomas. IgG and IL-6 levels were normal, and lymph node biopsy ruled out Castleman disease and lymphoma. The patient was subsequently discharged to continue outpatient follow-up for CD.

CD is one of the two main types of intestinal inflammatory disorders, the other one being ulcerative colitis (UC). Transmural inflammation of the intestine is the hallmark of CD, with granulomatous features seen on biopsy [ 3 ]. This report aims to emphasize atypical symptoms and endoscopic and histopathological findings. It is important to stress that reviewing atypical presentations will be helpful in the diagnosis of such cases in the future. The colonoscopy findings of a friable, nodular ulcerated ileocecal region with complete occlusion of the ileocecal valve are not those normally seen in CD. Moreover, it is unusual for colonoscopy biopsies to be inconclusive in this disease, as ileocolonoscopy with biopsy is the gold standard for evaluating the extent and severity [ 4 ].

This atypical presentation of CD deviates from the most common pattern found at the time of diagnosis, where the earliest endoscopic manifestations consist of small aphthous ulcers [ 5 ], followed later by characteristic findings of skip lesions, ulcerations, and strictures [ 6 ]. The essential feature to be noted in this case is the lack of conclusive findings in all investigations conducted, including CT scan, followed by the discovery of a hard mass during laparoscopic surgery. This finding is not very common in early CD. Patients with long-standing CD can present with a large abdominal mass, and the majority of the histopathologic evaluation revealed a neoplasm [ 7 ]. An abdominal mass has also been mentioned as a possible site-specific manifestation of CD [ 8 ]. Furthermore, in cases where suspicion of both CD and UC is present, the finding of an abdominal mass in addition to nausea and colicky abdominal pain favors a diagnosis of CD [ 9 ]. The prolonged and non-self-limiting course of the disease rules out the possibility of other infectious colitis [ 10 ].

Considering CD as the final diagnosis, the patient was started on a six-month course of medications, which included sulfasalazine and corticosteroids. The patient presented in the outpatient department after six months for a follow-up and reported complete remission of symptoms with no acute flare-ups. In addition to the medication, cessation of smoking immensely helped in improving the prognosis.

Conclusions

Analyzing the journey that concluded with the diagnosis of CD in our patient, it is crucial to note that evidence is not always found on colonoscopy biopsies, and it is essential to investigate further by other findings. Though the mesenteric adenitis visible on ultrasonography, along with the symptoms of vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss, raised concerns for possible intestinal tuberculosis, with similar nonspecific manifestations in earlier stages, the histological picture of the mass ultimately overruled any such diagnosis. The diagnostic clue lies in a combined assessment of symptoms, radiology, and histological evidence. However, early aggressive treatment results in a better prognosis, especially in patients with risk factors for complications of CD.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

- Earn HPCSA and SACNASP CPD Points

- I have spots and my skin burns

- A case of a 10 year old boy with a 3 week history of diarrhoea, vomiting and cough

- A case of fever and general malaise

- A case of persistant hectic fever

- A case of sudden rapid neurological deterioration in an HIV positive 27 year old female

- A case of swollen hands

- An unusual cause of fulminant hepatitis

- Case of a right axillary swelling

- Case of giant wart

- Case of recurrent meningitis

- Case of repeated apnoea and infections in a premature infant

- Case of sudden onset of fever, rash and neck pain

- Doctor, my sister is confused

- Eight month old boy with recurrent infections

- Enlarged Testicles

- Failure to thrive despite appropriate treatment

- Right Axillary Swelling

- Severe anaemia in HIV positive child

- The case of a floppy infant

- Two year old with spiking fevers and depressed level of consciousness

- 17 year old male with fever and decreased level of consciousness

- 3 TB Vignettes

- A 10 year old girl with a hard palate defect

- A case of decreased joint function, fever and rash

- Keep up while the storm is raging

- Fireworks of autoimmunity from birth

- My eyes cross at twilight

- A case of a 3 month old infant with bloody urine and stools

- A case of scaly annular plaques

- Case of eye injury and decreased vision

- My head hurts and I cannot speak?

- TB or not TB: a confusing case

- A 7 year old with severe muscle weakness and difficulty walking

- Why can I not walk today?

- 14 year old with severe hip pain

- A 9 year old girl presents with body swelling, shortness of breath and backache

- A sudden turn of events after successful therapy

- Declining CD4 count, despite viral suppression?

- Defaulted treatment

- 25 year old female presents with persistent flu-like symptoms

- A case of persistent bloody diarrhoea

- I’ve been coughing for so long

- A case of acute fever, rash and vomiting

- Adverse event following routine vaccination

- A case of cough, wasting and lymphadenopathy

- A case of lymphadenopathy and night sweats

- Case of enlarged hard tongue

- A high risk pregnancy

- A four year old with immunodeficiency

- Young girl with recurrent history of mycobacterial disease

- Immunodeficiency and failure to thrive

- Case of recurrent infections

- An 8 year old boy with recurrent respiratory infections

- 4 year old boy with recurrent bacterial infections

- Is this treatment failure or malnutrition

- 1. A Snapshot of the Immune System

- 2. Ontogeny of the Immune System

- 3. The Innate Immune System

- 4. MHC & Antigen Presentation

- 5. Overview of T Cell Subsets

- 6. Thymic T Cell Development

- 7. gamma/delta T Cells

- 8. B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- 9. Antibody Structure and Classes

- 10. Central and Peripheral Tolerance

- Immuno-Mexico 2024 Introduction

- Modulation of Peripheral Tolerance

- Metabolic Adaptation to Pathologic Milieu

- T Cell Exhaustion

- Suppression in the Context of Disease

- Redirecting Cytotoxicity

- Novel Therapeutic Strategies

- ImmunoInformatics

- Grant Writing

- Introduction to Immuno-Chile 2023

- Core Modules

- Gut Mucosal Immunity

- The Microbiome

- Gut Inflammation

- Viral Infections and Mucosal Immunity

- Colorectal Cancer

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Equity, Diversity, Inclusion in Academia

- Immuno-India 2023 Introduction

- Principles of Epigenetic Regulation

- Epigenetics Research in Systems Immunology

- Epigenetic (De)regulation in Non-Malignant Diseases

- Epigenetic (De)regulation in Immunodeficiency and Malignant Diseases

- Immunometabolism and Therapeutic Applications of Epigenetic Modifiers

- Immuno-Morocco 2023 Introduction

- Cancer Cellular Therapies

- Cancer Antibody Therapies

- Cancer Vaccines

- Immunobiology of Leukemia & Therapies

- Immune Landscape of the Tumour

- Targeting the Tumour Microenvironment

- Flow Cytometry

- Immuno-Zambia 2022 Introduction

- Immunity to Viral Infections

- Immunity to SARS-CoV2

- Basic Immunology of HIV

- Immunity to Tuberculosis

- Immunity to Malaria

- Immunity to Schistosomiasis

- Immunity to Helminths

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Academia

- Immuno-Argentina 2022 Introduction

- Dendritic Cells

- Trained Innate Immunity

- Gamma-Delta T cells

- Natural Killer Cell Memory

- Innate Immunity in Viral Infections

- Lectures – Innate Immunity

- T cells and Beyond

- Lectures – Cellular Immunity

- Strategies for Vaccine Design

- Lectures – Humoral Immunity

- Lectures – Vaccine development

- Lectures – Panel and Posters

- Immuno-Cuba 2022 Introduction

- Poster and Abstract Examples

- Immuno-Tunisia 2021 Introduction

- Basics of Anti-infectious Immunity

- Inborn Errors of Immunity and Infections

- Infection and Auto-Immunity

- Pathogen-Induced Immune Dysregulation & Cancer

- Understanding of Host-Pathogen Interaction & Applications (SARS-CoV-2)

- Day 1 – Basics of Anti-infectious Immunity

- Day 2 – Inborn Errors of Immunity and Infections

- Day 3 – Infection and Auto-immunity

- Day 4 – Pathogen-induced Immune Dysregulation and Cancer

- Day 5 – Understanding of Host-Pathogen Interaction and Applications

- Student Presentations

- Roundtable Discussions

- Orientation Meeting

- Poster Information

- Immuno-Colombia Introduction

- Core Modules Meeting

- Overview of Immunotherapy

- Check-Points Blockade Based Therapies

- Cancer Immunotherapy with γδ T cells

- CAR-T, armored CARs and CAR-NK therapies

- Anti-cytokines Therapies

- Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes (TIL)

- MDSC Promote Tumor Growth and Escape

- Immunological lab methods for patient’s follow-up

- Student Orientation Meeting

- Lectures – Week 1

- Lectures – Week 2

- Research Project

- Closing and Social

- Introduction to Immuno-Algeria 2020

- Hypersensitivity Reactions

- Immuno-Algeria Programme

- Online Lectures – Week 1

- Online Lectures – Week 2

- Student Presentations – Week 1

- Student Presentations – Week 2

- Introduction to Immuno-Ethiopia 2020

- Neutrophils

- Leishmaniasis – Transmission and Epidemiology

- Leishmaniasis – Immune Responses

- Leishmaniasis – Treatment and Vaccines

- Immunity to Helminth Infections

- Helminth immunomodulation on co-infections

- Malaria Vaccine Progress

- Immunity to Fungal Infections

- How to be successful scientist

- How to prepare a good academic CV

- Introduction to Immuno-Benin

- Immune Regulation in Pregnancy

- Immunity in infants and consequence of preeclampsia

- Schistosome infections and impact on Pregnancy

- Infant Immunity and Vaccines

- Regulation of Immunity & the Microbiome

- TGF-beta superfamily in infections and diseases

- Infectious Diseases in the Global Health era

- Immunity to Toxoplasma gondii

- A. melegueta inhibits inflammatory responses during Helminth Infections

- Host immune modulation by Helminth-induced products

- Immunity to HIV

- Immunity to Ebola

- Immunity to TB

- Genetic susceptibility in Tuberculosis

- Plant Extract Treatment for Diabetes

- Introduction to Immuno-South Africa 2019

- Models for Testing Vaccines

- Immune Responses to Vaccination

- IDA 2019 Quiz

- Introduction to Immuno-Jaipur

- Inflammation and autoinflammation

- Central and Peripheral Tolerance

- Autoimmunity and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases

- Autoimmunity & Dysregulation

- Novel Therapeutic strategies for Autoimmune Diseases

- Strategies to apply gamma/delta T cells for Immunotherapy

- Immune Responses to Cancer

- Tumour Microenvironment

- Cancer Immunotherapy

- Origin and perspectives of CAR T cells

- Metabolic checkpoints regulating immune responses

- Transplantation

- Primary Immunodeficiencies

- Growing up with Herpes virus

- Introduction to IUIS-ALAI-Mexico-ImmunoInformatics

- Introduction to Immunization Strategies

- Introduction to Immunoinformatics

- Omics Technologies

- Computational Modeling

- Machine Learning Methods

- Introduction to Immuno-Kenya

- Viruses hijacking host immune responses

- IFNs as 1st responders to virus infections

- HBV/HCV & Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Cytokines as biomarkers for HCV

- HTLV & T cell Leukemia

- HCMV and Cancers

- HPV and Cancers

- EBV-induced Oncogenesis

- Adenoviruses

- KSHV and HIV

- Ethics in Cancer Research

- Sex and gender in Immunity

- Introduction to Immuno-Iran

- Immunity to Leishmaniasis

- Breaking Tolerance: Autoimmunity & Dysregulation

- Introduction to Immuno-Morocco

- Cancer Epidemiology and Aetiology

- Pathogens and Cancer

- Immunodeficiency and Cancer

- Introduction to Immuno-Brazil

- 1. Systems Vaccinology

- 2. Vaccine Development

- 3. Adjuvants

- 4. DNA Vaccines

- 5. Mucosal Vaccines

- 6. Vaccines for Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Introduction to Immuno-Gambia

- Immuno-Gambia Photos

- 1. Infant Immunity and Vaccines

- 2. Dendritic Cells

- 3. Conventional T Cells

- 4. gamma/delta T Cells

- 5. Immunity to Viral Infections

- 6. Immunity to Helminth Infections

- 7. Immunity to TB

- 8. Immunity to Malaria

- 9. Flow Cytometry

- Introduction to Immuno-South Africa

- 1. Introduction to Immunization Strategies

- 2. Immune Responses to Vaccination

- 3. Models for Testing Vaccines

- 4. Immune Escape

- 5. Grant Writing

- Introduction to Immuno-Ethiopia

- 1. Neutrophils

- 3. Exosomes

- 5. Immunity to Leishmania

- 6. Immunity to HIV

- 7. Immunity to Helminth Infections

- 8. Immunity to TB

- 9. Grant Writing

- Introduction to ONCOIMMUNOLOGY-MEXICO

- ONCOIMMUNOLOGY-MEXICO Photos

- 1. Cancer Epidemiology and Etiology

- 2. T lymphocyte mediated immunity

- 3. Immune Responses to Cancer

- 4. Cancer Stem Cells and Tumor-initiating cells.

- 5. Tumor Microenvironment

- 6. Pathogens and Cancer

- 7. Cancer Immunotherapy

- 8. Flow cytometry approaches in cancer

- Introduction to the Immunology Course

- Immuno-Tunisia Photo

- 1. Overview of the Immune System

- 2. Role of cytokines in Immunity

- 3. Tolerance and autoimmunity

- 4. Genetics, Epigenetics and immunoregulation

- 5. Microbes and immunoregulation

- 6. Inflammation and autoinflammation

- 7. T cell mediated autoimmune diseases

- 8. Antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases

- Introduction to the Immunology Symposium

- Immuno-South Africa Photo

- 1. Antibody Generation by B cells

- 2. Mucosal Immunity

- 3. Immunity to TB

- 4. Immunity to Malaria

- 5. Immunity to HIV

- 6. Defining a Biomarker

- 7. Grant Writing Exercise

- Immuno-Colombia Photo

- 1. Overview of Complement

- 2. Transplantation

- 3. Immune Regulation in Pregnancy

- 4. Breaking Tolerance: Autoimmunity & Dysregulation

- 5. Mucosal Immunity & Immunopathology

- 6. Regulation of Immunity & the Microbiome

- 7. Epigenetics & Modulation of Immunity

- 8. Primary Immunodeficiencies

- 9. Anti-tumour Immunity

- 10. Cancer Immunotherapy

- Introduction

- Immune Cells

- NCDs and Multimorbidity

- Mosquito Vector Biology

- Vaccines and Other Interventions

- Autoimmunity

- Career Development

- SUN Honours Introduction

- A Snapshot of the Immune System

- Ontogeny of the Immune System

- The Innate Immune System

- MHC & Antigen Presentation

- Overview of T Cell Subsets

- B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- Antibody Structure and Classes

- Cellular Immunity and Immunological Memory

- Infectious Diseases Immunology

- Vaccinology

- Mucosal Immunity & Immunopathology

- Central & Peripheral Tolerance

- Epigenetics & Modulation of Immunity

- T cell and Ab-mediated autoimmune diseases

- Immunology of COVID-19 Vaccines

- 11th IDA 2022 Introduction

- Immunity to COVID-19

- Fundamentals of Immunology

- Fundamentals of Infection

- Integrating Immunology & Infection

- Infectious Diseases Symposium

- EULAR Symposium

- Thymic T Cell Development

- Immune Escape

- Genetics, Epigenetics and immunoregulation

- AfriBop 2021 Introduction

- Adaptive Immunity

- Fundamentals of Infection 2

- Fundamentals of Infection 3

- Host pathogen Interaction 1

- Host pathogen Interaction 2

- Student 3 minute Presentations

- 10th IDA 2021 Introduction

- Day 1 – Lectures

- Day 2 – Lectures

- Day 3 – Lectures

- Day 4 – Lectures

- Afribop 2020 Introduction

- WT PhD School Lectures 1

- EULAR symposium

- WT PhD School Lectures 2

- Host pathogen interaction 1

- Host pathogen interaction 2

- Bioinformatics

- Introduction to VACFA Vaccinology 2020

- Overview of Vaccinology

- Basic Principles of Immunity

- Adverse Events Following Immunization

- Targeted Immunization

- Challenges Facing Vaccination

- Vaccine Stakeholders

- Vaccination Questions Answered

- Malaria Vaccines

- IDA 2018 Introduction

- Vaccine Development

- Immune Escape by Pathogens

- Immunity to Viral Infections Introduction

- Flu, Ebola & SARS

- Antiretroviral Drug Treatments

- Responsible Conduct in Research

- Methods for Enhancing Reproducibility

- 6. B Cell Activation and Plasma Cell Differentiation

- 7. Antibody Structure and Classes

- CD Nomenclature

- 1. Transplantation

- 2. Central & Peripheral Tolerance

- 8. Inflammation and autoinflammation

- 9. T cell mediated autoimmune diseases

- 10. Antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases

- 1. Primary Immunodeficiencies

- Cancer Stem Cells and Tumour-initiating Cells

- 6. Tolerance and Autoimmunity

- Discovery of the Thymus as a central immunological organ

- History of Immune Response

- History of Immunoglobulin molecules

- History of MHC – 1901 – 1970

- History of MHC – 1971 – 2011

- SAIS/Immunopaedia Webinars 2022

- Metabolic control of T cell differentiation during immune responses to cancer

- Microbiome control of host immunity

- Shaping of anti-tumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment

- The unusual COVID-19 pandemic: the African story

- Immune responses to SARS-CoV-2

- Adaptive Immunity and Immune Memory to SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19

- HIV prevention- antibodies and vaccine development (part 2)

- HIV prevention- antibodies and vaccine development (part 1)

- Immunopathology of COVID 19 lessons from pregnancy and from ageing

- Clinical representation of hyperinflammation

- In-depth characterisation of immune cells in Ebola virus

- Getting to the “bottom” of arthritis

- Immunoregulation and the tumor microenvironment

- Harnessing innate immunity from cancer therapy to COVID-19

- Flynn Webinar: Immune features associated natural infection

- Flynn Webinar: What immune cells play a role in protection against M.tb re-infection?

- JoAnne Flynn: BCG IV vaccination induces sterilising M.tb immunity

- IUIS-Immunopaedia-Frontiers Webinar on Immunology taught by P. falciparum

- COVID-19 Cytokine Storm & Paediatric COVID-19

- Immunothrombosis & COVID-19

- Severe vs mild COVID-19 immunity and Nicotinamide pathway

- BCG & COVID-19

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Antibody responses and serology testing

- Flow Cytometry Part 1

- Flow Cytometry Part 2

- Flow Cytometry Part 3

- Lateral Flow

- Diagnostic Tools

- Diagnostic Tests

- HIV Life Cycle

- ARV Drug Information

- ARV Mode of Action

- ARV Drug Resistance

- Declining CD4 count

- Ambassador of the Month – 2024

- North America

- South America

- Ambassador of the Month – 2023

- Ambassador of the Month – 2022

- The Day of Immunology 2022

- AMBASSADOR SCI-TALKS

- The Day of Immunology 2021

- Ambassador of the Month – 2021

- Ambassador of the Month-2020

- Ambassador of the Month – 2019

- Ambassador of the Month – 2018

- Ambassador of the Month – 2017

- Course Applications

- COLLABORATIONS

We will not share your details

Infectious Diseases

Please choose a Case Study below

© 2004 - 2024 Immunopaedia.org.za Sitemap - Privacy Policy - Cookie Policy - PAIA - Terms & Conditions

Website designed by Personalised Promotions in association with SA Medical Specialists .

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- CLINICAL CASES

- ONLINE COURSES

- AMBASSADORS

- TREATMENT & DIAGNOSTICS

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present patient...

How to present patient cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Ni Lochlainn , foundation year 2 doctor 1 ,

- Ibrahim Balogun , healthcare of older people/stroke medicine consultant 1

- 1 East Kent Foundation Trust, UK

A guide on how to structure a case presentation

This article contains...

-History of presenting problem

-Medical and surgical history

-Drugs, including allergies to drugs

-Family history

-Social history

-Review of systems

-Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

-Differential diagnosis/impression

-Investigations

-Management

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1

The purpose of a case presentation is to communicate your diagnostic reasoning to the listener, so that he or she has a clear picture of the patient’s condition and further management can be planned accordingly. 2 To give a high quality presentation you need to take a thorough history. Consultants make decisions about patient care based on information presented to them by junior members of the team, so the importance of accurately presenting your patient cannot be overemphasised.

As a medical student, you are likely to be asked to present in numerous settings. A formal case presentation may take place at a teaching session or even at a conference or scientific meeting. These presentations are usually thorough and have an accompanying PowerPoint presentation or poster. More often, case presentations take place on the wards or over the phone and tend to be brief, using only memory or short, handwritten notes as an aid.

Everyone has their own presenting style, and the context of the presentation will determine how much detail you need to put in. You should anticipate what information your senior colleagues will need to know about the patient’s history and the care he or she has received since admission, to enable them to make further management decisions. In this article, I use a fictitious case to show how you can structure case presentations, which can be adapted to different clinical and teaching settings (box 1).

Box 1: Structure for presenting patient cases

Presenting problem, history of presenting problem, medical and surgical history.

Drugs, including allergies to drugs

Family history

Social history, review of systems.

Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

Differential diagnosis/impression

Investigations

Case: tom murphy.

You should start with a sentence that includes the patient’s name, sex (Mr/Ms), age, and presenting symptoms. In your presentation, you may want to include the patient’s main diagnosis if known—for example, “admitted with shortness of breath on a background of COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].” You should include any additional information that might give the presentation of symptoms further context, such as the patient’s profession, ethnic origin, recent travel, or chronic conditions.

“ Mr Tom Murphy is a 56 year old ex-smoker admitted with sudden onset central crushing chest pain that radiated down his left arm.”

In this section you should expand on the presenting problem. Use the SOCRATES mnemonic to help describe the pain (see box 2). If the patient has multiple problems, describe each in turn, covering one system at a time.

Box 2: SOCRATES—mnemonic for pain

Associations

Time course

Exacerbating/relieving factors

“ The pain started suddenly at 1 pm, when Mr Murphy was at his desk. The pain was dull in nature, and radiated down his left arm. He experienced shortness of breath and felt sweaty and clammy. His colleague phoned an ambulance. He rated the pain 9/10 in severity. In the ambulance he was given GTN [glyceryl trinitrate] spray under the tongue, which relieved the pain to 5/10. The pain lasted 30 minutes in total. No exacerbating factors were noted. Of note: Mr Murphy is an ex-smoker with a 20 pack year history”

Some patients have multiple comorbidities, and the most life threatening conditions should be mentioned first. They can also be categorised by organ system—for example, “has a long history of cardiovascular disease, having had a stroke, two TIAs [transient ischaemic attacks], and previous ACS [acute coronary syndrome].” For some conditions it can be worth stating whether a general practitioner or a specialist manages it, as this gives an indication of its severity.

In a surgical case, colleagues will be interested in exercise tolerance and any comorbidity that could affect the patient’s fitness for surgery and anaesthesia. If the patient has had any previous surgical procedures, mention whether there were any complications or reactions to anaesthesia.

“Mr Murphy has a history of type 2 diabetes, well controlled on metformin. He also has hypertension, managed with ramipril, and gout. Of note: he has no history of ischaemic heart disease (relevant negative) (see box 3).”

Box 3: Relevant negatives

Mention any relevant negatives that will help narrow down the differential diagnosis or could be important in the management of the patient, 3 such as any risk factors you know for the condition and any associations that you are aware of. For example, if the differential diagnosis includes a condition that you know can be hereditary, a relevant negative could be the lack of a family history. If the differential diagnosis includes cardiovascular disease, mention the cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index, smoking, and high cholesterol.

Highlight any recent changes to the patient’s drugs because these could be a factor in the presenting problem. Mention any allergies to drugs or the patient’s non-compliance to a previously prescribed drug regimen.

To link the medical history and the drugs you might comment on them together, either here or in the medical history. “Mrs Walsh’s drugs include regular azathioprine for her rheumatoid arthritis.”Or, “His regular drugs are ramipril 5 mg once a day, metformin 1g three times a day, and allopurinol 200 mg once a day. He has no known drug allergies.”

If the family history is unrelated to the presenting problem, it is sufficient to say “no relevant family history noted.” For hereditary conditions more detail is needed.

“ Mr Murphy’s father experienced a fatal myocardial infarction aged 50.”

Social history should include the patient’s occupation; their smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug status; who they live with; their relationship status; and their sexual history, baseline mobility, and travel history. In an older patient, more detail is usually required, including whether or not they have carers, how often the carers help, and if they need to use walking aids.

“He works as an accountant and is an ex-smoker since five years ago with a 20 pack year history. He drinks about 14 units of alcohol a week. He denies any illicit drug use. He lives with his wife in a two storey house and is independent in all activities of daily living.”

Do not dwell on this section. If something comes up that is relevant to the presenting problem, it should be mentioned in the history of the presenting problem rather than here.

“Systems review showed long standing occasional lower back pain, responsive to paracetamol.”

Findings on examination

Initially, it can be useful to practise presenting the full examination to make sure you don’t leave anything out, but it is rare that you would need to present all the normal findings. Instead, focus on the most important main findings and any abnormalities.

“On examination the patient was comfortable at rest, heart sounds one and two were heard with no additional murmurs, heaves, or thrills. Jugular venous pressure was not raised. No peripheral oedema was noted and calves were soft and non-tender. Chest was clear on auscultation. Abdomen was soft and non-tender and normal bowel sounds were heard. GCS [Glasgow coma scale] was 15, pupils were equal and reactive to light [PEARL], cranial nerves 1-12 were intact, and he was moving all four limbs. Observations showed an early warning score of 1 for a tachycardia of 105 beats/ min. Blood pressure was 150/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, saturations were 98% on room air, and he was apyrexial with a temperature of 36.8 ºC.”

Differential diagnoses

Mentioning one or two of the most likely diagnoses is sufficient. A useful phrase you can use is, “I would like to rule out,” especially when you suspect a more serious cause is in the differential diagnosis. “History and examination were in keeping with diverticular disease; however, I would like to rule out colorectal cancer in this patient.”

Remember common things are common, so try not to mention rare conditions first. Sometimes it is acceptable to report investigations you would do first, and then base your differential diagnosis on what the history and investigation findings tell you.

“My impression is acute coronary syndrome. The differential diagnosis includes other cardiovascular causes such as acute pericarditis, myocarditis, aortic stenosis, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism. Possible respiratory causes include pneumonia or pneumothorax. Gastrointestinal causes include oesophageal spasm, oesophagitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, gastritis, cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis. I would also consider a musculoskeletal cause for the pain.”

This section can include a summary of the investigations already performed and further investigations that you would like to request. “On the basis of these differentials, I would like to carry out the following investigations: 12 lead electrocardiography and blood tests, including full blood count, urea and electrolytes, clotting screen, troponin levels, lipid profile, and glycated haemoglobin levels. I would also book a chest radiograph and check the patient’s point of care blood glucose level.”

You should consider recommending investigations in a structured way, prioritising them by how long they take to perform and how easy it is to get them done and how long it takes for the results to come back. Put the quickest and easiest first: so bedside tests, electrocardiography, followed by blood tests, plain radiology, then special tests. You should always be able to explain why you would like to request a test. Mention the patient’s baseline test values if they are available, especially if the patient has a chronic condition—for example, give the patient’s creatinine levels if he or she has chronic kidney disease This shows the change over time and indicates the severity of the patient’s current condition.

“To further investigate these differentials, 12 lead electrocardiography was carried out, which showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads. Results of laboratory tests showed an initial troponin level of 85 µg/L, which increased to 1250 µg/L when repeated at six hours. Blood test results showed raised total cholesterol at 7.6 mmol /L and nil else. A chest radiograph showed clear lung fields. Blood glucose level was 6.3 mmol/L; a glycated haemoglobin test result is pending.”

Dependent on the case, you may need to describe the management plan so far or what further management you would recommend.“My management plan for this patient includes ACS [acute coronary syndrome] protocol, echocardiography, cardiology review, and treatment with high dose statins. If you are unsure what the management should be, you should say that you would discuss further with senior colleagues and the patient. At this point, check to see if there is a treatment escalation plan or a “do not attempt to resuscitate” order in place.

“Mr Murphy was given ACS protocol in the emergency department. An echocardiogram has been requested and he has been discussed with cardiology, who are going to come and see him. He has also been started on atorvastatin 80 mg nightly. Mr Murphy and his family are happy with this plan.”

The summary can be a concise recap of what you have presented beforehand or it can sometimes form a standalone presentation. Pick out salient points, such as positive findings—but also draw conclusions from what you highlight. Finish with a brief synopsis of the current situation (“currently pain free”) and next step (“awaiting cardiology review”). Do not trail off at the end, and state the diagnosis if you are confident you know what it is. If you are not sure what the diagnosis is then communicate this uncertainty and do not pretend to be more confident than you are. When possible, you should include the patient’s thoughts about the diagnosis, how they are feeling generally, and if they are happy with the management plan.

“In summary, Mr Murphy is a 56 year old man admitted with central crushing chest pain, radiating down his left arm, of 30 minutes’ duration. His cardiac risk factors include 20 pack year smoking history, positive family history, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Examination was normal other than tachycardia. However, 12 lead electrocardiography showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads and troponin rise from 85 to 250 µg/L. Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated and a diagnosis of NSTEMI [non-ST elevation myocardial infarction] was made. Mr Murphy is currently pain free and awaiting cardiology review.”

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2017;25:i4406

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 - 3 . doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0900-x pmid:19139965 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Olaitan A, Okunade O, Corne J. How to present clinical cases. Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539.

- ↵ Gaillard F. The secret art of relevant negatives, Radiopedia 2016; http://radiopaedia.org/blog/the-secret-art-of-relevant-negatives .

- Biomarker-Driven Lung Cancer

- HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Small Cell Lung Cancer

- Renal Cell Carcinoma

- CONFERENCES

- PUBLICATIONS

Case Presentation: A 67-Year-Old Man with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

John Allan, MD, presents and reviews the case of a 67-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

EP: 1 . Case Presentation: A 67-Year-Old Man with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Ep: 2 . testing and risk stratification in cll, ep: 3 . first-line therapy options in cll, ep: 4 . chronic lymphocytic leukemia: resonate-2 trial, ep: 5 . comparing btk inhibitors in cll treatment, ep: 6 . treatment approaches for high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia, ep: 7 . the future of chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment.

John Allan, MD: Welcome, everyone. Thank you for joining, I’m John Allan. I'm an assistant professor of medicine here at Weill Cornell Medicine, in New York City.

I'm a lymphoma physician. I have a specialization in CLL [chronic lymphocytic leukemia], and treating patients with CLL, and we'll be going through a case and I’ll be giving you my insights on my thoughts about the case and how I might manage the patient potentially differently or the same. I would like to start out by presenting the case so everyone is on the same page here. This is a 67-year-old male with a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. He's presenting to his primary care physician with complaints of fatigue and night sweats. In terms of past medical history, he's relatively healthy, except that he takes an over-the-counter antacid every few days, a couple times a week, for a sensitive stomach.

On a physical exam, he has a large mobile lymph node, these are bilaterally, in the cervical chain. No palpable spleen or liver, palpable liver is noted. Laboratory findings are consistent with a white blood cell count of a 102,000, lymphocytes are 79,000 of those 102. Hemoglobin is slightly low but relatively OK, and preserved at 11.4 grams per deciliter. His platelets are normal at 180,000. His neutrophil count is normal at 1.9. His LDH [lactate dehydrogenase] is actually very elevated, at 1470. And cytogenetics are showing a chromosome 11q deletion and IgHV [immunoglobulin heavy chain] unmutated status.

I presume this was sent off not by the primary care, but by his hematologist. And a beta-2 macroglobulin was also obtained and that's 3.0, right on the threshold of being abnormal. He's staged as a Rai Stage I, and the patient initiated treatment, and was started on ibrutinib once daily.

John Allan, MD: So, this case is a somewhat common presentation that we see, especially with a patient with these molecular abnormalities. Average age diagnosis of patients as a reminder is about 70 to 71 years of age, so the patient is well within that nice bell-shaped curve. He was relatively healthy, feeling well, up until very recently when these symptoms started.

The disease has been progressive relatively quickly, and associated with these B symptoms with a very elevated white blood cell count, along with the fevers and night sweats. Also note is that the LDH is rather elevated. The high end of normal, at least in my lab, is around 230 or 220. This patient is at 1470.

Additionally, the cytogenetics are identifying relatively high-risk features with the deletion 11q and IgHV unmutated status. This is somebody that I am concerned about. I do agree with the treatment decision to initiate therapy. A few things to note, deletion 11q, it's considered high risk feature, and patients do present a little bit differently with an 11q than some of the other patients with CLL.

Many times, the 11q patients have rather proliferative disease at diagnosis and they can present with a lot of bulky adenopathy. While this patient doesn't have technically bulky adenopathy, and really what's palpable is only about a centimeter and a half, it's very possible that with deep within the abdomen something that we're not palpating he can have a very large lymph node, 6 to 8 centimeters or larger.

Typically, that's associated with signs and symptoms, but given the fact that these fevers, night sweats and rather proliferative disease with an elevated LDH together with these high-risk features, this is someone I might be concerned about even with a transformation as an initial presentation of their CLL and would need to work up and rule that out appropriately.

With that said, the patient was started on ibrutinib, and overall is a good therapy. And so, those are the big, noteworthy aspects of this case, and can be a rather typical presentation for a patient with deletion 11q molecular features like this patient.

John Allan, MD: One other aspect of this case that's unique is that the patient is on over-the-counter antacids, and this is a relatively common thing. Many patients are takig either over-the-counter antacids like Pepcid [famotidine], Prilosec [omeprazole], etc.

I'm sorry, those are more PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] but acid suppressing medications either H2 [histamine2] blockers calcium absorbing, calcium carbonate like medications and or proton pump inhibitors.

And so, this is not just unique to CLL patients, this is just unique to older patients and patient population in general, where in the US specifically there is a lot of PPI use, whether it's over-the-counter or prescribed.

Ultimately, in clinical trials with BTK [Bruton’s tyrosine kinase] inhibitors and targeted agents we do see about 40% to 45% of patients on some type of acid suppressive medication. This is a very common scenario and it may have some relevance based on differentiating between BTKi's at this point in time.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Initial Presentation

- A 67-year-old man presented to PCP with complaints of fatigue and night sweats

- PMH: patient takes OTC antiacid tablets a few times a week for a “sensitive” stomach

- PE: Enlarged mobile lymph nodes bilaterally (~1.5 cm), no palpable spleen or liver

- Laboratory findings:

- WBC; 102 X 109/L

- Lymphocytes; 79 X 109/L

- Hb; 11.4 g/dL

- Platelets; 180 X 109/L

- ANC; 1,900/mm3

- LDH 1470 U/L

- Cytogenetics; del(11q), IgVH-unmutated

- beta2M, 3.0 mg/L

- Rai Stage I

Treatment Plan

- Patient was started on ibrutinib

Exciting Activity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

In season 4, episode 7 of Targeted Talks, Cyrus M. Khan, MD, discusses the latest FDA activity in the chronic lymphocytic leukemia space.

Lachowiez Considers the Use of Tagraxofusp in BPDCN as Bridge to SCT With Peers

During a Targeted Oncology™ Case-Based Roundtable™ event, Curtis Lachowiez, MD, discussed targeted therapy for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm and its role in patients who could receive allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Better Strategies for the Treatment of High-Risk Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

In season 3, episode 4 of Targeted Talks, Alexey Danilov, MD, PhD, discusses the shift toward utilizing cellular therapy to treat high-risk patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Hoffmann Discusses Deciding Factors for Treating Patients With CLL

In the first article of a 2-part series, Marc S. Hoffmann, MD, looks at the factors to take into consideration before initiating another line of treatment in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Behind the FDA Approval of Liso-cel for Relapsed/Refractory CLL/SLL

In an interview with Targeted Oncology, Tanya Siddiqi, MD, discussed the rationale behind the TRANSCEND CLL 004 study supporting the FDA approval of lisocabtagene maraleucel in chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Previous Article

- Next Article

CASE PRESENTATION

Exercise implications, peripheral arterial disease: a case report from the henry ford hospital.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Shel D. Levine; Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Case Report From the Henry Ford Hospital. Journal of Clinical Exercise Physiology 1 March 2018; 7 (1): 15–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.31189/2165-6193-7.1.15

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

A.T. is a 65-year-old black female with claudication secondary to peripheral arterial disease (PAD). She has a history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, endarterectomy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and asthma.

She was referred to the Division of Vascular Surgery at Henry Ford Hospital complaining of fatigue and heaviness in her lower thighs and calves during walking. Resting ankle-brachial index (ABI) was 0.50 and 0.70 at the right and left dorsalis pedis, respectively. She was prescribed cilostazol and encouraged to “…walk through the pain as much as possible.”

Due to worsening claudication, A.T. underwent an abdominal aortogram with arteriogram of the lower extremities. Results showed aortoiliac disease with multiple stenoses of varying degrees. Areas of calcification were noted from the lower aorta and iliac artery to the anterior tibial artery affecting both the left and right limbs.

Results from a stress echocardiogram showed cardiac wall motion abnormalities consistent with exercise-induced ischemia. She exercised for 5.8 minutes on the Bruce protocol, limited by general fatigue. The electrocardiogram displayed left bundle branch block, resting ejection fraction was 40%, peak blood pressure was 160/80 mmHg, and peak heart rate was 120 b·min −1 . No symptoms were reported. Her medications are cilostazol, carvedilol, amlodipine, isosorbide dinitrate, clopidogrel, simvastatin, potassium, triamcinolone, ipratropium, and pirbuterol.

She began supervised exercise training in cardiac rehabilitation following a hospitalization for angina. At rest her blood pressure was 120/50 mmHg, heart rate was 79 b·min −1 , blood glucose was 6.89 mmol·L −1 (266 mg·dL −1 ) and her HbA1c was 8.0%. Her initial exercise sessions were limited by bilateral claudication of her thighs and calves. Moderate pain occurred after 9 minutes of walking on day 1. A pain-rest walking program was initiated and followed for 12 weeks. She then joined the Henry Ford PREVENT program, which provides patients with a low-cost, long-term supervised exercise environment.

She now exercises at least 3 d·wk −1 for 60 minutes each session. She splits her exercise time between a seated stepper and a treadmill. On most days she is now able to walk 30 continuous minutes without limiting claudication pain.

The natural history of arteriosclerosis involves an intimal plaque that progressively develops until it eventually causes a significant flow limiting occlusion of the vessel and reduction of blood supply relative to demand. Arteriosclerosis is a systemic disorder affecting the major circulations, with the intimal plaque occurring segmentally in multiple locations. When the plaque occurs in the distal aorta or in the arteries of the lower extremities, it is referred to as PAD.

Epidemiology

More than 8 million individuals in the United States above the age of 40 are estimated to have PAD ( 1 ). The prevalence of PAD per ABI is 4.3% in persons older than 40 years and up ( 2 ) and 29% in those 70 years and older ( 3 ). Thus PAD afflicts more than 4 million Americans and more than 200 million people worldwide. The age-adjusted prevalence of PAD increases to approximately 12% when more sensitive vascular imaging studies are used. Unlike coronary artery disease, the incidence of PAD is similar in men and women. Coronary artery disease occurs in 60% to 90% of patients with PAD. The incidence of cerebral vascular disease is increased in patients with PAD as well.

Natural History

Peripheral arterial disease is part of the spectrum of atherosclerosis. It is associated with coronary and carotid artery disease. PAD increases mortality by 6-fold, due mostly to myocardial infarction and stroke. The 5-year mortality rate in patients with PAD is ≈ 30%, with a major lower extremity amputation rate near 1% to 2%. If the patient continues to smoke, the mortality rate doubles and the risk for amputation increases 10-fold. Aortoiliac disease has a higher mortality than femoral artery disease due to a greater prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients with the former.

Ten percent of patients with intermittent claudication will go on to have ischemic pain at rest (aka, critical limb ischemia), often leading to ulceration or amputation. The presence of diabetes mellitus also affects morbidity and mortality in patients with PAD. Sixty percent of leg amputations are the result of diabetic peripheral vascular disease. In fact, among patients with diabetes for 25 years or more, the risk of below the knee amputation is increased 12-fold.

The risk factors for coronary artery disease are also risk factors for the development of PAD (i.e., age greater than 65 years, cigarette smoking, and diabetes mellitus). Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a 4-fold increased risk for PAD, while their risk for myocardial infarction or stroke is increased only 2-fold. The severity of PAD is not related to glycemic control but rather to the number of coexisting risk factors. Therefore, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and hyperhomocysteinemia are also important risk factors for PAD. For each 0.03 mmol·L −1 (1 mg·dL −1 ) increase in total cholesterol, there is a 1% increased incidence of PAD. A reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increased triglyceride are also closely associated with PAD. In the presence of these risk factors and given the systemic nature of atherosclerosis and its poor prognosis, patients with PAD should be thought of as already having coronary and carotid artery disease.

Clinical Features

Unless there is acute occlusion by thrombosis, the symptoms of PAD occur gradually and progressively. Intermittent claudication is the major symptom of PAD. Claudication is derived from the Latin word claudicato , meaning to limp , which describes the gait of a patient with intermittent claudication. Intermittent claudication is most often described as an aching, cramping, or tightness in the muscles of the leg (usually the calf) that occurs with exercise and is relieved with rest. The pain usually disappears within several minutes after stopping exercise. The discomfort reoccurs at a constant distance. The distance is shorter if the patient is walking uphill or climbing stairs, and this pain does not occur at rest.

Despite claudication being the hallmark symptom of PAD, it is estimated that approximately 60% to 70% of individuals with disease do not have this symptom ( 4 ). The reason for this disparity is not entirely clear, but often patients with PAD may have diabetic neuropathy, which could mask symptoms, or they may simply not report discomfort because of the false assumption that it is simply pain associated with the aging process (e.g., arthritis). Another possibility could be because of avoidance of activities that may cause leg pain (e.g. exercise, yard work, walking long distances).

Some areas of the vascular tree are more likely to develop atherosclerotic plaque than others. In the abdomen, the stenosis usually occurs in the distal aorta or common iliac arteries. Distal to the inguinal ligament, the most common occlusions occur in the adductor canal, the posterior tibial artery at the ankle, and the anterior tibial artery at its origin. Stenosis of the external iliac and popliteal arteries occurs less frequently.

The location of the claudication is useful in predicting the most proximal level of occlusion. Intermittent claudication of the calf muscles does not occur with occlusions in the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, or peroneal arteries. It requires a more proximal lesion. Calf and thigh claudication suggests that the area of stenosis is proximal to the origin of the vascular supply to the thigh muscles (i.e. the profunda femoris artery). Thigh and buttock claudication with impotence in a middle-aged male is called Leriche Syndrome and signifies terminal aortic disease.

Pseudoclaudication must be differentiated from true claudication. Pseudoclaudication occurs from nonvascular causes of leg pain such as spinal stenosis, herniated nucleus pulposus, spinal cord tumors, and degenerative joint disease. It is usually described as a paresthetic discomfort (i.e., numbness, tingling, and/or weakness). The exercise-pain-rest cycle is not consistent in that standing does not relieve the pain. Sitting down may relieve it, and the time required for the pain to disappear is usually several minutes or more.

Physical Examination

Patients with isolated nonobstructive lesions frequently have normal-appearing extremities. Paresthesia, numbness, ulceration, and gangrene are also symptoms of PAD but represent an advanced stage with multiple lesions. Loss of hair, trophic nail changes, and dependent rubor (redness caused by swelling) can also be seen. Loss of the peripheral pulse distal to the occlusion occurs in chronic disease. The pulses that should be checked include the femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial. Pulses should be described as: 0, absent; 1, diminished; 2, normal; or 3, bounding. Auscultation for bruits should also be performed over the abdomen and femoral arteries.

The resting ABI is considered the first-line test for PAD with a sensitivity ranging from 68% to 84% and a specificity of 84% to 99% compared to the gold standard of vascular imaging ( 1 ). ABI is measured by taking systolic blood pressure in the arm (i.e., brachial artery) and dividing it by pressure in the ipsilateral ankle (greater value between the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial arteries). A normal value is 1.0 or greater ( Table 1 ). Values less than 0.5 are usually seen in patients with diffuse disease. A study of over 2,000 patients with PAD showed an abnormal ABI (< 0.91) to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular events and total mortality, with an annual mortality of 25% for the lowest ABI values ( 5 ). Values over 1.4 are likely due to noncompressible vessels from extensive disease and calcification.

Interpretation of ABI values.

The ABI can also be measured immediately after exercise. It should be the same or higher than the resting value. A drop in the ABI after exercise in someone who was normal or borderline at rest also suggests significant disease. As the arterioles within the exercising muscles dilate, the stenosis in the artery proximal to the muscle limits augmentation of blood flow and pressure drops. The postexercise ABI is often used to follow disease progression, as well as adequacy of medical and surgical therapy.

Ultrasonic duplex scanning, computed tomography angiography, or magnetic resonance angiography can be used to evaluate the severity of the disease and determining a treatment plan. Ultimately, angiography is necessary to localize the lesion and determine the extent of disease prior to surgery or percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

The goals of treatment include reducing the symptom of intermittent claudication, improving mobility and quality of life, and halting the progression of atherosclerosis. Aggressive risk factor modification should be the cornerstone of any treatment plan. Due to the poor appreciation that PAD represents systemic atherosclerosis and is associated with a poor prognosis, many patients with PAD are undertreated. Smoking cessation through educational programs, nicotine-replacement therapy, and antidepressant drugs should be strongly considered. In those patients with hyperlipidemia, low density lipoprotein cholesterol should be at least less than 2.59 mmol·L −1 (100 mg·dL −1 ) and triglyceride should be less than 3.89 mmol·L −1 (150 mg·dL −1 ). Statin agents, in addition to lowering cholesterol, also may improve endothelial function. The treatment of hypertension and diabetes mellitus does not alter the natural history of PAD. Similarly, hyperhomocysteinemia is easily measured and treated, but there are no clinical trials assessing efficacy, and thus the current guidelines state that homocysteine lowering is of no benefit. At present there is no role for the use of hormone replacement therapy. Antiplatelet agents (i.e., aspirin and clopidogrel) reduce the risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events and are approved by the Food & Drug Administration for secondary prevention in patients with atherosclerosis. Probably due to a long history of use and few side effects, aspirin remains the drug of choice ( 1 ). Aspirin may also be administered with clopidogrel, which may reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death in those with symptoms ( 1 ).

Meticulous foot care is extremely important, with special attention to properly fitting shoes and immediate attention to cuts and blisters. This is especially true for patients with diabetes mellitus, because with a peripheral neuropathy they might not experience pain as a warning sign of developing foot problems.

Medical treatment has met with mixed results. Vasodilators are not effective and are not used in the treatment of PAD. Pentoxifylline is no longer recommended as treatment for claudication pain. Cilostazol inhibits platelet aggregation and smooth-muscle proliferation and causes vasodilatation. In 4 randomized placebo-controlled trials, cilostazol improved both pain-free walking and maximal treadmill walking distance, but it did not improve the incidence of cardiovascular death ( 6 , 7 ).

For patients with lifestyle-limiting symptoms and hemodynamically significant aortoiliac disease, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty is an excellent alternative to surgery, giving results comparable to surgery without the morbidity. The ideal lesion for percutaneous transluminal angioplasty is an iliac stenosis less than 5 cm in length or a femoropopliteal stenosis less than 10 cm in length. Long-term results are best when the lesion is above the groin area. The majority of patients with PAD will not require surgical therapy, and a class I recommendation is to offer all patients exercise training therapy initially versus revascularization ( 1 ). Patients who do develop ischemic pain at rest, ulcers, or gangrene may be helped by surgery.

Exercise Testing

Since atherosclerosis represents the most common cause of death in patients with PAD, screening for coronary artery disease is important. Exercise testing guidelines outlined by the American College of Sports Medicine are appropriate for patients with PAD ( 8 ). A common treadmill protocol used in this patient population is the Gardner protocol ( 9 ) (Box 1). In patients with PAD, a symptom-limited exercise test can help identify exercise-induced myocardial ischemia, quantify aerobic capacity, evaluate postexercise ABI, identify time to initial claudication pain, and develop an exercise prescription.

Constant speed of 2.0 mph (3.2 kph)

Increments of elevation every 2 min

○ Start at 0%

○ Increase by 2%

Record pain-free and maximal walking time

Patients with PAD have 6 times the mortality as their age- and gender-matched peers.

Intermittent claudication is the defining symptom of PAD, traditionally affecting the calves but possibly including the thighs or buttocks.

Patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral neuropathy may not experience claudication in spite of severe PAD.

In addition to detecting PAD, the ankle-brachial index test is an important non-invasive predictor of cardiovascular events and total mortality.

Smoking cessation, exercise, and modification of other risk factors are the foundation for treating PAD.

Reported peak oxygen consumption values in patients with PAD is 13 to 14 mL·kg −1 ·min −1 ( 10 , 11 ). Tests utilizing treadmill exercise will likely be limited by claudication. Although the time to onset of pain and maximal walking time during treadmill exercise are important markers of the severity of PAD and used for outcome comparisons, tests limited by claudication may not provide sufficient myocardial stress for proper assessment of cardiovascular disease risk. Submaximal stress may be avoided by using leg or arm ergometry while still providing information useful for developing an exercise prescription.

Submaximal functional evaluations, such as the 6-minute walk test, may better reflect the impact of claudication on daily physical activities. Among patients with PAD, Montgomery et al. ( 12 ) found the 6-minute walk test to be reliable and correlated with the time to claudication pain during treadmill testing and ABI.

Exercise Training

Exercise training has been recommended to patients with intermittent claudication for many years, with several randomized controlled trials of exercise training reported. And importantly in May 2017 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved supervised exercise training as a reimbursable intervention for patients with symptomatic PAD who are referred by their physician. The impetus for this approval is an ever-growing amount of research demonstrating functional and quality of life improvements in those with symptomatic PAD who undergo an exercise training program. Virtually all trials that have evaluated the importance of exercise training in patients with PAD have exhibited an increase in exercise tolerance. And the evidence for exercise training benefits has resulted in the higher recommendation by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology for supervised exercise training ( 1 ).

Patients with PAD are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and should be appropriately evaluated for exercise-induced myocardial ischemia.

PAD results in reduced exercise tolerance due to metabolic dysfunction, skeletal muscle abnormalities, diminished cardiorespiratory reserve, and exercise-induced inflammation. Exercise training improves pain-free and peak walking ability. Compared to stenting, improvement with walking is similar for pain-free walking and superior for peak walking time. Both are better than optimal medical therapy.

Optimal exercise training benefits are derived from programs that include walking to moderate pain with intermittent rest, accumulating 30 to 45 minutes, 3 d·wk −1 (or more), for at least 6 months.

The Claudication: Exercise Vs. Endoluminal Revascularization (CLEVER) study was the defining study to convince the CMS to cover supervised exercise training for PAD ( 13 ). CLEVER randomized revascularization-eligible patients to either medical care alone (i.e., advice and cilostazol), medical care plus revascularization, or medical care plus exercise training. The exercise training group had equivalent pain-free walking time as compared to the revascularization group (with both better than medical care alone) at 6 and 18 months. And the exercise group improved more than both other groups in peak walking time, which improved by 4.6 minutes (95% CI, P = 0.001) versus only 2.1 (95% CI, P = 0.04) minutes, respectively for the supervised exercise and control groups. The authors stated that supervised exercise is a reasonable strategy, as compared to stenting, and programs should be developed that are available and affordable to patients ( 13 ).

A meta-analysis from the Cochrane database ( 14 ) involving 32 critically evaluated randomized controlled trials of exercise therapy that randomized a total of 1,835 patients reported an overall improvement in peak walking distance of 120 meters (95% CI 50.79 to 189.92, P < 0.0007, high-quality evidence). Pain-free walking distance was also improved, as compared to a control group, by an average of 82 meters (95% CI 71.73 to 92.48, P < 0.00001, high-quality evidence). These findings are consistent with an earlier meta-analysis that reported improvements of 179% and 122% for walking distance to the onset of pain and to maximal pain, respectively ( 15 ). It is noted that exercise training has not been shown to affect the ABI ( 14 ).

In addition to the reduction in blood flow due to PAD, several factors have been associated with the reduced exercise capacity observed among these patients ( Figure 1 ). These include metabolic dysfunction, skeletal muscle abnormalities, reduced cardiorespiratory reserve, and exercise-induced inflammation. With exercise training there is increased skeletal muscle fiber area and improved oxidative capacity, blood flow, gait biomechanics, and blood rheology (e.g., viscosity, filterability and aggregation) ( 16 ). Due to chronic ischemia and reperfusion, multiple episodes of local and systemic inflammation occur in patients with PAD and is exacerbated by acute exercise, yet its contribution to disease progression is unknown. Also unknown is the role exercise training may have on modifying this inflammatory response.

Factors associated with reduced exercise capacity in patients with PAD.

The majority of exercise training trials in patients with claudication have used walking as the exercise training mode, as well as the primary outcome measured. As a result, walking predominates in the exercise prescription even though the mechanisms by which these patients improve remain unclear. Other exercise modes have also shown benefit. Sanderson et al. ( 17 ) evaluated the training response of 42 patients with symptomatic claudication randomized to 6 weeks of leg cycling, treadmill walking, or non-exercise control. The leg cycling group improved both pain-free and peak walking time versus control. However, this improvement was not as great as the treadmill walking group. Treat-Jacobson et al. ( 18 ) assessed 12 weeks of upper-body ergometry training versus treadmill walking and reported significant improvements in both groups for pain-free and peak walking time. These data suggest a systemic effect with exercise training.

The effects of progressive resistance exercise in patients with claudication are not well investigated. Hiatt et al. ( 19 ) found lesser improvements in walking time following 12 weeks of strength training (36%), compared to treadmill exercise (74%). In addition, strength training combined with treadmill exercise did not provide additional benefits. Similarly, McDermott et al. ( 20 ) compared treadmill walking with progressive resistance training in a group of 156 patients with PAD. They noted improvements in both groups in peak walking time versus control, but the treadmill group improved more than the resistance training group (3.4 vs. 1.9 minutes).

Exercise Prescription

Exercise prescription guidelines outlined by the American College of Sports Medicine are appropriate for patients with PAD ( 8 ). The exercise prescription for maximal walking improvements in patients with claudication secondary to PAD should be walking-focused. Ideally a patient should perform intermittent walking to the point of moderately tolerable claudication pain, alternated with rest ( Figure 2 ). Rest periods should last until pain is completely (or nearly) relieved enough to continue walking. Patients should accumulate at least 30 minutes, but preferably 45 to 60 minutes, of this type of training at least 3 d·wk −1 . Exercise intensity should be slowly increased when a patient can walk more than 8 minutes without at least moderate pain. As exercise tolerance improves, some PAD patients may increase their total continuous walking time, or potentially introduce intermittent bouts throughout the day. Maximal benefits have been reported after 6 months of training, thus it is important to encourage patients to continue exercising beyond a typical 12-week supervised exercise training program. In addition to this standard recommendation, some patients may further improve cardiorespiratory function by performing additional aerobic exercise via exercise modes that are not limited by claudication (e.g., leg cycling, seated stepping, elliptical). This might be useful for select patients who either have a low functional capacity or who are not able to tolerate more than 30 minutes of the walking to moderate claudication pain protocol. Additionally, there are long-term health benefits of performing continuous exercise at an intensity that provides a cardiorespiratory stimulus (i.e., > 50% peak). And it is interesting to note that PAD patients who performed any amount of physical activity beyond light intensity showed a lower mortality rate than similar patients who were effectively sedentary ( 14 ). This reduced risk of mortality remained evident even when the findings were adjusted for age, ABI, and body mass index ( 21 ).

Claudication Training Pain Scale.

“Stop smoking and keep walking” has long been the recommendation for people with claudication. Although significant improvements in pain-free and peak walking distance are well documented by those who perform regular exercise, the mechanisms and their relative contribution remain unclear. In addition, their impact, if any, on disease progression and mortality requires further investigation. In spite of various medical therapies (e.g,, medications, revascularization), exercise training continues to produce the most favorable outcomes and should be routinely incorporated into the treatment plan for patients with PAD.

Author notes

1 School of Health Promotion & Human Performance, Department of Exercise Science, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, Michigan

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: None.

Recipient(s) will receive an email with a link to 'Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Case Report From the Henry Ford Hospital' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Case Report From the Henry Ford Hospital

(Optional message may have a maximum of 1000 characters.)

Citing articles via

Get email alerts.

- Submit an Article

- Subscribe to the Journal

Affiliations

- eISSN 2165-7629

- ISSN 2165-6193

- Privacy Policy

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies