Nuclear Energy

Nuclear energy is the energy in the nucleus, or core, of an atom. Nuclear energy can be used to create electricity, but it must first be released from the atom.

Engineering, Physics

Loading ...

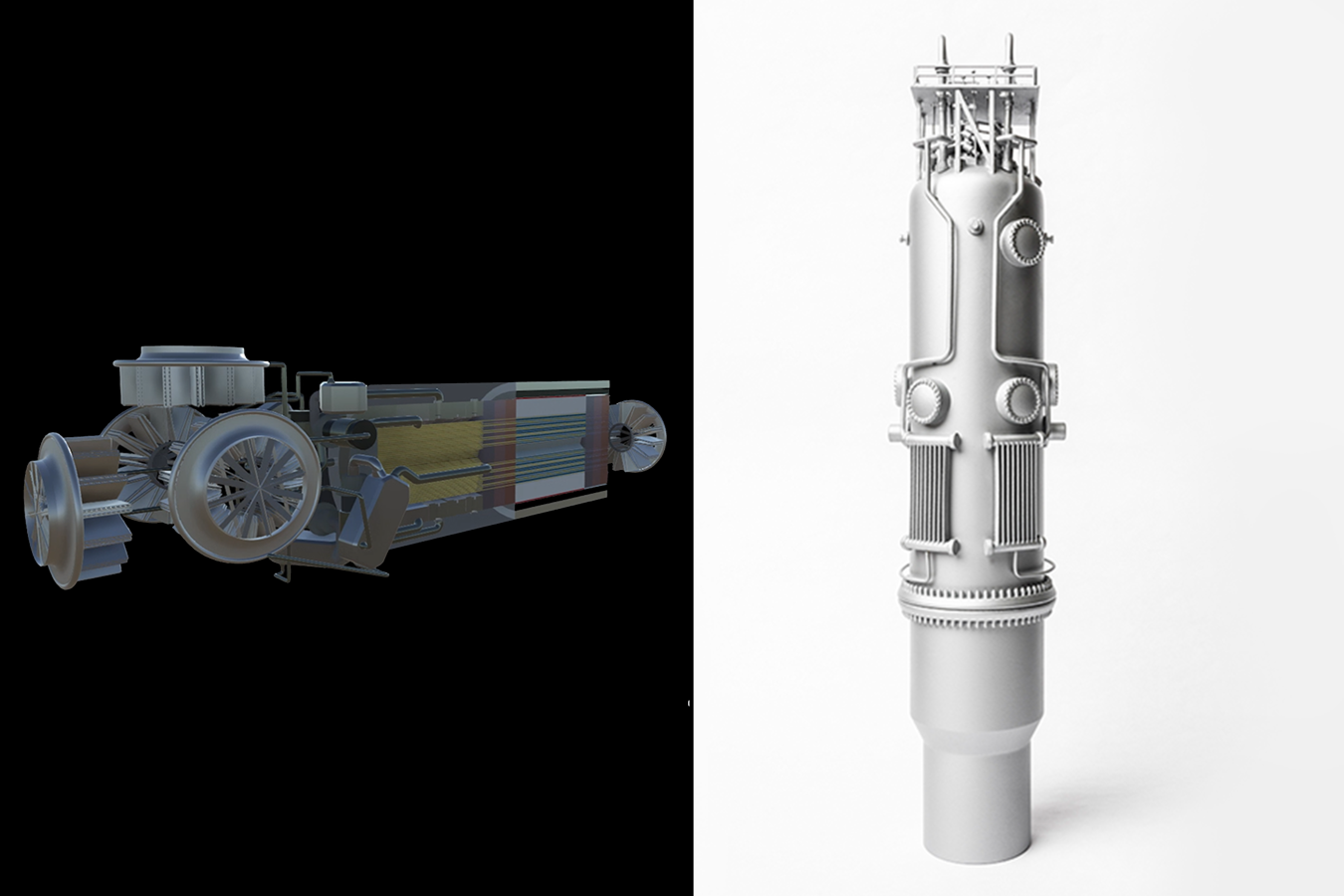

Nuclear energy is the energy in the nucleus , or core, of an atom . Atoms are tiny units that make up all matter in the universe , and energy is what holds the nucleus together. There is a huge amount of energy in an atom 's dense nucleus . In fact, the power that holds the nucleus together is officially called the " strong force ." Nuclear energy can be used to create electricity , but it must first be released from the atom . In the process of nuclear fission , atoms are split to release that energy. A nuclear reactor , or power plant , is a series of machines that can control nuclear fission to produce electricity . The fuel that nuclear reactors use to produce nuclear fission is pellets of the element uranium . In a nuclear reactor , atoms of uranium are forced to break apart. As they split, the atoms release tiny particles called fission products. Fission products cause other uranium atoms to split, starting a chain reaction . The energy released from this chain reaction creates heat. The heat created by nuclear fission warms the reactor's cooling agent . A cooling agent is usually water, but some nuclear reactors use liquid metal or molten salt . The cooling agent , heated by nuclear fission , produces steam . The steam turns turbines , or wheels turned by a flowing current . The turbines drive generators , or engines that create electricity . Rods of material called nuclear poison can adjust how much electricity is produced. Nuclear poisons are materials, such as a type of the element xenon , that absorb some of the fission products created by nuclear fission . The more rods of nuclear poison that are present during the chain reaction , the slower and more controlled the reaction will be. Removing the rods will allow a stronger chain reaction and create more electricity . As of 2011, about 15 percent of the world's electricity is generated by nuclear power plants . The United States has more than 100 reactors, although it creates most of its electricity from fossil fuels and hydroelectric energy . Nations such as Lithuania, France, and Slovakia create almost all of their electricity from nuclear power plants . Nuclear Food: Uranium Uranium is the fuel most widely used to produce nuclear energy . That's because uranium atoms split apart relatively easily. Uranium is also a very common element, found in rocks all over the world. However, the specific type of uranium used to produce nuclear energy , called U-235 , is rare. U-235 makes up less than one percent of the uranium in the world.

Although some of the uranium the United States uses is mined in this country, most is imported . The U.S. gets uranium from Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Once uranium is mined, it must be extracted from other minerals . It must also be processed before it can be used. Because nuclear fuel can be used to create nuclear weapons as well as nuclear reactors , only nations that are part of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) are allowed to import uranium or plutonium , another nuclear fuel . The treaty promotes the peaceful use of nuclear fuel , as well as limiting the spread of nuclear weapons . A typical nuclear reactor uses about 200 tons of uranium every year. Complex processes allow some uranium and plutonium to be re-enriched or recycled . This reduces the amount of mining , extracting , and processing that needs to be done. Nuclear Energy and People Nuclear energy produces electricity that can be used to power homes, schools, businesses, and hospitals. The first nuclear reactor to produce electricity was located near Arco, Idaho. The Experimental Breeder Reactor began powering itself in 1951. The first nuclear power plant designed to provide energy to a community was established in Obninsk, Russia, in 1954. Building nuclear reactors requires a high level of technology , and only the countries that have signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty can get the uranium or plutonium that is required. For these reasons, most nuclear power plants are located in the developed world. Nuclear power plants produce renewable, clean energy . They do not pollute the air or release greenhouse gases . They can be built in urban or rural areas , and do not radically alter the environment around them. The steam powering the turbines and generators is ultimately recycled . It is cooled down in a separate structure called a cooling tower . The steam turns back into water and can be used again to produce more electricity . Excess steam is simply recycled into the atmosphere , where it does little harm as clean water vapor . However, the byproduct of nuclear energy is radioactive material. Radioactive material is a collection of unstable atomic nuclei . These nuclei lose their energy and can affect many materials around them, including organisms and the environment. Radioactive material can be extremely toxic , causing burns and increasing the risk for cancers , blood diseases, and bone decay .

Radioactive waste is what is left over from the operation of a nuclear reactor . Radioactive waste is mostly protective clothing worn by workers, tools, and any other material that have been in contact with radioactive dust. Radioactive waste is long-lasting. Materials like clothes and tools can stay radioactive for thousands of years. The government regulates how these materials are disposed of so they don't contaminate anything else. Used fuel and rods of nuclear poison are extremely radioactive . The used uranium pellets must be stored in special containers that look like large swimming pools. Water cools the fuel and insulates the outside from contact with the radioactivity. Some nuclear plants store their used fuel in dry storage tanks above ground. The storage sites for radioactive waste have become very controversial in the United States. For years, the government planned to construct an enormous nuclear waste facility near Yucca Mountain, Nevada, for instance. Environmental groups and local citizens protested the plan. They worried about radioactive waste leaking into the water supply and the Yucca Mountain environment, about 130 kilometers (80 miles) from the large urban area of Las Vegas, Nevada. Although the government began investigating the site in 1978, it stopped planning for a nuclear waste facility in Yucca Mountain in 2009. Chernobyl Critics of nuclear energy worry that the storage facilities for radioactive waste will leak, crack, or erode . Radioactive material could then contaminate the soil and groundwater near the facility . This could lead to serious health problems for the people and organisms in the area. All communities would have to be evacuated . This is what happened in Chernobyl, Ukraine, in 1986. A steam explosion at one of the power plants four nuclear reactors caused a fire, called a plume . This plume was highly radioactive , creating a cloud of radioactive particles that fell to the ground, called fallout . The fallout spread over the Chernobyl facility , as well as the surrounding area. The fallout drifted with the wind, and the particles entered the water cycle as rain. Radioactivity traced to Chernobyl fell as rain over Scotland and Ireland. Most of the radioactive fallout fell in Belarus.

The environmental impact of the Chernobyl disaster was immediate . For kilometers around the facility , the pine forest dried up and died. The red color of the dead pines earned this area the nickname the Red Forest . Fish from the nearby Pripyat River had so much radioactivity that people could no longer eat them. Cattle and horses in the area died. More than 100,000 people were relocated after the disaster , but the number of human victims of Chernobyl is difficult to determine . The effects of radiation poisoning only appear after many years. Cancers and other diseases can be very difficult to trace to a single source. Future of Nuclear Energy Nuclear reactors use fission, or the splitting of atoms , to produce energy. Nuclear energy can also be produced through fusion, or joining (fusing) atoms together. The sun, for instance, is constantly undergoing nuclear fusion as hydrogen atoms fuse to form helium . Because all life on our planet depends on the sun, you could say that nuclear fusion makes life on Earth possible. Nuclear power plants do not have the capability to safely and reliably produce energy from nuclear fusion . It's not clear whether the process will ever be an option for producing electricity . Nuclear engineers are researching nuclear fusion , however, because the process will likely be safe and cost-effective.

Nuclear Tectonics The decay of uranium deep inside the Earth is responsible for most of the planet's geothermal energy, causing plate tectonics and continental drift.

Three Mile Island The worst nuclear accident in the United States happened at the Three Mile Island facility near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1979. The cooling system in one of the two reactors malfunctioned, leading to an emission of radioactive fallout. No deaths or injuries were directly linked to the accident.

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Illustrators

Educator reviewer, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- ENVIRONMENT

What is nuclear energy and is it a viable resource?

Nuclear energy's future as an electricity source may depend on scientists' ability to make it cheaper and safer.

Nuclear power is generated by splitting atoms to release the energy held at the core, or nucleus, of those atoms. This process, nuclear fission, generates heat that is directed to a cooling agent—usually water. The resulting steam spins a turbine connected to a generator, producing electricity.

About 450 nuclear reactors provide about 11 percent of the world's electricity. The countries generating the most nuclear power are, in order, the United States, France, China, Russia, and South Korea.

The most common fuel for nuclear power is uranium, an abundant metal found throughout the world. Mined uranium is processed into U-235, an enriched version used as fuel in nuclear reactors because its atoms can be split apart easily.

In a nuclear reactor, neutrons—subatomic particles that have no electric charge—collide with atoms, causing them to split. That collision—called nuclear fission—releases more neutrons that react with more atoms, creating a chain reaction. A byproduct of nuclear reactions, plutonium , can also be used as nuclear fuel.

Types of nuclear reactors

In the U.S. most nuclear reactors are either boiling water reactors , in which the water is heated to the boiling point to release steam, or pressurized water reactors , in which the pressurized water does not boil but funnels heat to a secondary water supply for steam generation. Other types of nuclear power reactors include gas-cooled reactors, which use carbon dioxide as the cooling agent and are used in the U.K., and fast neutron reactors, which are cooled by liquid sodium.

Nuclear energy history

The idea of nuclear power began in the 1930s , when physicist Enrico Fermi first showed that neutrons could split atoms. Fermi led a team that in 1942 achieved the first nuclear chain reaction, under a stadium at the University of Chicago. This was followed by a series of milestones in the 1950s: the first electricity produced from atomic energy at Idaho's Experimental Breeder Reactor I in 1951; the first nuclear power plant in the city of Obninsk in the former Soviet Union in 1954; and the first commercial nuclear power plant in Shippingport, Pennsylvania, in 1957. ( Take our quizzes about nuclear power and see how much you've learned: for Part I, go here ; for Part II, go here .)

Nuclear power, climate change, and future designs

Nuclear power isn't considered renewable energy , given its dependence on a mined, finite resource, but because operating reactors do not emit any of the greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming , proponents say it should be considered a climate change solution . National Geographic emerging explorer Leslie Dewan, for example, wants to resurrect the molten salt reactor , which uses liquid uranium dissolved in molten salt as fuel, arguing it could be safer and less costly than reactors in use today.

Others are working on small modular reactors that could be portable and easier to build. Innovations like those are aimed at saving an industry in crisis as current nuclear plants continue to age and new ones fail to compete on price with natural gas and renewable sources such as wind and solar.

The holy grail for the future of nuclear power involves nuclear fusion, which generates energy when two light nuclei smash together to form a single, heavier nucleus. Fusion could deliver more energy more safely and with far less harmful radioactive waste than fission, but just a small number of people— including a 14-year-old from Arkansas —have managed to build working nuclear fusion reactors. Organizations such as ITER in France and Max Planck Institute of Plasma Physics are working on commercially viable versions, which so far remain elusive.

Nuclear power risks

When arguing against nuclear power, opponents point to the problems of long-lived nuclear waste and the specter of rare but devastating nuclear accidents such as those at Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima Daiichi in 2011 . The deadly Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine happened when flawed reactor design and human error caused a power surge and explosion at one of the reactors. Large amounts of radioactivity were released into the air, and hundreds of thousands of people were forced from their homes . Today, the area surrounding the plant—known as the Exclusion Zone—is open to tourists but inhabited only by the various wildlife species, such as gray wolves , that have since taken over .

In the case of Japan's Fukushima Daiichi, the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami caused the plant's catastrophic failures. Several years on, the surrounding towns struggle to recover, evacuees remain afraid to return , and public mistrust has dogged the recovery effort, despite government assurances that most areas are safe.

Other accidents, such as the partial meltdown at Pennsylvania's Three Mile Island in 1979, linger as terrifying examples of nuclear power's radioactive risks. The Fukushima disaster in particular raised questions about safety of power plants in seismic zones, such as Armenia's Metsamor power station.

Other issues related to nuclear power include where and how to store the spent fuel, or nuclear waste, which remains dangerously radioactive for thousands of years. Nuclear power plants, many of which are located on or near coasts because of the proximity to water for cooling, also face rising sea levels and the risk of more extreme storms due to climate change.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- NUCLEAR ENERGY

- NUCLEAR WEAPONS

- TOXIC WASTE

- RENEWABLE ENERGY

You May Also Like

This pill could protect us from radiation after a nuclear meltdown

Scientists achieve a breakthrough in nuclear fusion. Here’s what it means.

This young nuclear engineer has a new plan for clean energy

The true history of Einstein's role in developing the atomic bomb

The controversial future of nuclear power in the U.S.

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on Nuclear Energy in 500+ words for School Students

- Updated on

- Dec 30, 2023

Essay on Nuclear Energy: Nuclear energy has been fascinating and controversial since the beginning. Using atomic power to generate electricity holds the promise of huge energy supplies but we cannot overlook the concerns about safety, environmental impact, and the increase in potential weapon increase.

The blog will help you to explore various aspects of energy seeking its history, advantages, disadvantages, and role in addressing the global energy challenge.

Table of Contents

- 1 History Overview

- 2 Nuclear Technology

- 3 Advantages of Nuclear Energy

- 4 Disadvantages of Nuclear Energy

- 5 Safety Measures and Regulations of Nuclear Energy

- 6 Concerns of Nuclear Proliferation

- 7 Future Prospects and Innovations of Nuclear Energy

- 8 FAQs

Also Read: Find List of Nuclear Power Plants In India

History Overview

The roots of nuclear energy have their roots back to the early 20th century when innovative discoveries in physics laid the foundation for understanding atomic structure. In the year 1938, Otto Hahn, a German chemist and Fritz Stassman, a German physical chemist discovered nuclear fission, the splitting of atomic nuclei. This discovery opened the way for utilising the immense energy released during the process of fission.

Also Read: What are the Different Types of Energy?

Nuclear Technology

Nuclear power plants use controlled fission to produce heat. The heat generated is further used to produce steam, by turning the turbines connected to generators that produce electricity. This process takes place in two types of reactors: Pressurized Water Reactors (PWR) and Boiling Water Reactors (BWR). PWRs use pressurised water to transfer heat. Whereas, BWRs allow water to boil, which produces steam directly.

Also Read: Nuclear Engineering Course: Universities and Careers

Advantages of Nuclear Energy

Let us learn about the positive aspects of nuclear energy in the following:

1. High Energy Density

Nuclear energy possesses an unparalleled energy density which means that a small amount of nuclear fuel can produce a substantial amount of electricity. This high energy density efficiency makes nuclear power reliable and powerful.

2. Low Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Unlike other traditional fossil fuels, nuclear power generation produces minimum greenhouse gas emissions during electricity generation. The low greenhouse gas emissions feature positions nuclear energy as a potential solution to weakening climate change.

3. Base Load Power

Nuclear power plants provide consistent, baseload power, continuously operating at a stable output level. This makes nuclear energy reliable for meeting the constant demand for electricity, complementing intermittent renewable sources of energy like wind and solar.

Also Read: How to Become a Nuclear Engineer in India?

Disadvantages of Nuclear Energy

After learning the pros of nuclear energy, now let’s switch to the cons of nuclear energy.

1. Radioactive Waste

One of the most important challenges that is associated with nuclear energy is the management and disposal of radioactive waste. Nuclear power gives rise to spent fuel and other radioactive byproducts that require secure, long-term storage solutions.

2. Nuclear Accidents

The two catastrophic accidents at Chornobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011 underlined the potential risks of nuclear power. These nuclear accidents can lead to severe environmental contamination, human casualties, and long-lasting negative perceptions of the technology.

3. High Initial Costs

The construction of nuclear power plants includes substantial upfront costs. Moreover, stringent safety measures contribute to the overall expenses, which makes nuclear energy economically challenging compared to some renewable alternatives.

Also Read: What is the IAEA Full Form?

Safety Measures and Regulations of Nuclear Energy

After recognizing the potential risks associated with nuclear energy, strict safety measures and regulations have been implemented worldwide. These safety measures include reactor design improvements, emergency preparedness, and ongoing monitoring of the plant operations. Regulatory bodies, such as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in the United States, play an important role in overseeing and enforcing safety standards.

Also Read: What is the Full Form of AEC?

Concerns of Nuclear Proliferation

The dual-use nature of nuclear technology raises concerns about the spread of nuclear weapons. The same nuclear technology used for the peaceful generation of electricity can be diverted for military purposes. International efforts, including the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), aim to help the proliferation of nuclear weapons and promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Also Read: Dr. Homi J. Bhabha’s Education, Inventions & Discoveries

Future Prospects and Innovations of Nuclear Energy

The ongoing research and development into advanced reactor technologies are part of nuclear energy. Concepts like small modular reactors (SMRs) and Generation IV reactors aim to address safety, efficiency, and waste management concerns. Moreover, the exploration of nuclear fusion as a clean and virtually limitless energy source represents an innovation for future energy solutions.

Nuclear energy stands at the crossroads of possibility and peril, offering the possibility of addressing the world´s growing energy needs while posing important challenges. Striking a balance between utilising the benefits of nuclear power and alleviating its risks requires ongoing technological innovation, powerful safety measures, and international cooperation.

As we drive the complexities of perspective challenges of nuclear energy, the role of nuclear energy in the global energy mix remains a subject of ongoing debate and exploration.

Also Read: Essay on Science and Technology for Students: 100, 200, 350 Words

Ans. Nuclear energy is the energy released during nuclear reactions. Its importance lies in generating electricity, medical applications, and powering spacecraft.

Ans. Nuclear energy is exploited from the nucleus of atoms through processes like fission or fusion. It is a powerful and controversial energy source with applications in power generation and various technologies.

Ans. The five benefits of nuclear energy include: 1. Less greenhouse gas emissions 2. High energy density 3. Continuos power generation 4. Relatively low fuel consumption 5. Potential for reducing dependence on fossil fuels

Ans. Three important facts about nuclear energy: a. Nuclear fission releases a significant amount of energy. b. Nuclear power plants use controlled fission reactions to generate electricity. c. Nuclear fusion, combining atomic nuclei, is a potential future energy source.

Ans. Nuclear energy is considered best due to its low carbon footprint, high energy output, and potential to address energy needs. However, concerns about safety, radioactive waste, and proliferation risk are challenges that need careful consideration.

Related Articles

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Deepika Joshi

Deepika Joshi is an experienced content writer with expertise in creating educational and informative content. She has a year of experience writing content for speeches, essays, NCERT, study abroad and EdTech SaaS. Her strengths lie in conducting thorough research and ananlysis to provide accurate and up-to-date information to readers. She enjoys staying updated on new skills and knowledge, particulary in education domain. In her free time, she loves to read articles, and blogs with related to her field to further expand her expertise. In personal life, she loves creative writing and aspire to connect with innovative people who have fresh ideas to offer.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Climate Change

- Policy & Economics

- Biodiversity

- Conservation

Get focused newsletters especially designed to be concise and easy to digest

- ESSENTIAL BRIEFING 3 times weekly

- TOP STORY ROUNDUP Once a week

- MONTHLY OVERVIEW Once a month

- Enter your email *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Nuclear Energy

Since the first nuclear plant started operations in the 1950s, the world has been highly divided on nuclear as a source of energy. While it is a cleaner alternative to fossil fuels, this type of power is also associated with some of the world’s most dangerous and deadliest weapons, not to mention nuclear disasters . The extremely high cost and lengthy process to build nuclear plants are compensated by the fact that producing nuclear energy is not nearly as polluting as oil and coal. In the race to net-zero carbon emissions, should countries still rely on nuclear energy or should they make space for more fossil fuels and renewable energy sources? We take a look at the advantages and disadvantages of nuclear energy.

What Is Nuclear Energy?

Nuclear energy is the energy source found in an atom’s nucleus, or core. Once extracted, this energy can be used to produce electricity by creating nuclear fission in a reactor through two kinds of atomic reaction: nuclear fusion and nuclear fission. During the latter, uranium used as fuel causes atoms to split into two or more nuclei. The energy released from fission generates heat that brings a cooling agent, usually water, to boil. The steam deriving from boiling or pressurised water is then channelled to spin turbines to generate electricity. To produce nuclear fission, reactors make use of uranium as fuel.

For centuries, the industrialisation of economies around the world was made possible by fossil fuels like coal, natural gas, and petroleum and only in recent years countries opened up to alternative, renewable sources like solar and wind energy. In the 1950s, early commercial nuclear power stations started operations, offering to many countries around the world an alternative to oil and gas import dependency and a far less polluting energy source than fossil fuels. Following the 1970s energy crisis and the dramatic increase of oil prices that resulted from it, more and more countries decided to embark on nuclear power programmes. Indeed, most reactors have been built between 1970 and 1985 worldwide. Today, nuclear energy meets around 10% of global energy demand , with 439 currently operational nuclear plants in 32 countries and about 55 new reactors under construction. In 2020, 13 countries produced at least one-quarter of their total electricity from nuclear, with the US, China, and France dominating the market by far.

Fossil fuels make up 60% of the United States’ electricity while the remaining 40% is equally split between renewables and nuclear power. France embarked on a sweeping expansion of its nuclear power industry in the 1970s with the ultimate goal of breaking its dependence on foreign oil. In doing this, the country was able to build up its economy by simultaneously cutting its emissions at a rate never seen before. Today, France is home to 56 operating reactors and it relies on nuclear power for 70% of its electricity .

You might also like: A ‘Breakthrough’ In Nuclear Fusion: What Does It Mean for the Future of Energy Generation?

Advantages of Nuclear Energy

France’s success in cutting down emissions is a clear example of some of the main advantages of nuclear energy over fossil fuels. First and foremost, nuclear energy is clean and it provides pollution-free power with no greenhouse gas emissions. Contrary to what many believe, cooling towers in nuclear plants only emit water vapour and are thus, not releasing any pollutant or radioactive substance into the atmosphere. Compared to all the energy alternatives we currently have on hand, many experts believe that nuclear energy is indeed one of the cleanest sources. Many nuclear energy supporters also argue that nuclear power is responsible for the fastest decarbonisation effort in history , with big nuclear players like France, Saudi Arabia, Canada, and South Korea being among the countries that recorded the fastest decline in carbon intensity and experienced a clean energy transition by building nuclear reactors and hydroelectric dams.

Earlier this year, the European Commission took a clear stance on nuclear power by labelling it a green source of energy in its classification system establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. While nuclear energy may be clean and its production emission-free, experts highlight a hidden danger of this power: nuclear waste. The highly radioactive and toxic byproduct from nuclear reactors can remain radioactive for tens of thousands of years. However, this is still considered a much easier environmental problem to solve than climate change. The main reason for this is that as much as 90% of the nuclear waste generated by the production of nuclear energy can be recycled. Indeed, the fuel used in a reactor, typically uranium, can be treated and put into another reactor as only a small amount of energy in their fuel is extracted in the fission process.

A rather important advantage of nuclear energy is that it is much safer than fossil fuels from a public health perspective. The pro-nuclear movement leverages the fact that nuclear waste is not even remotely as dangerous as the toxic chemicals coming from fossil fuels. Indeed, coal and oil act as ‘ invisible killers ’ and are responsible for 1 in 5 deaths worldwide . In 2018 alone, fossil fuels killed 8.7 million people globally. In contrast, in nearly 70 years since the beginning of nuclear power, only three accidents have raised public alarm: the 1979 Three Mile Island accident, the 1986 Chernobyl disaster and the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. Of these, only the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine directly caused any deaths.

Finally, nuclear energy has some advantages compared to some of the most popular renewable energy sources. According to the US Office of Nuclear Energy , nuclear power has by far the highest capacity factor, with plants requiring less maintenance, capable to operate for up to two years before refuelling and able to produce maximum power more than 93% of the time during the year, making them three times more reliable than wind and solar plants.

You might also like: Nuclear Energy: A Silver Bullet For Clean Energy?

Disadvantages of Nuclear Energy

The anti-nuclear movement opposes the use of this type of energy for several reasons. The first and currently most talked about disadvantage of nuclear energy is the nuclear weapon proliferation, a debate triggered by the deadly atomic bombing of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War and recently reopened following rising concerns over nuclear escalation in the Ukraine-Russia conflict . After the world saw the highly destructive effect of these bombs, which caused the death of tens of thousands of people, not only in the impact itself but also in the days, weeks, and months after the tragedy as a consequence of radiation sickness, nuclear energy evolved to a pure means of generating electricity. In 1970, the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons entered into force. Its objective was to prevent the spread of such weapons to eventually achieve nuclear disarmament as well as promote peaceful uses of nuclear energy. However, opposers of this energy source still see nuclear energy as being deeply intertwined with nuclear weapons technologies and believe that, with nuclear technologies becoming globally available, the risk of them falling into the wrong hands is high, especially in countries with high levels of corruption and instability.

As mentioned in the previous section, nuclear energy is clean. However, radioactive nuclear waste contains highly poisonous chemicals like plutonium and the uranium pellets used as fuel. These materials can be extremely toxic for tens of thousands of years and for this reason, they need to be meticulously and permanently disposed of. Since the 1950s, a stockpile of 250,000 tonnes of highly radioactive nuclear waste has been accumulated and distributed across the world, with 90,000 metric tons stored in the US alone. Knowing the dangers of nuclear waste, many oppose nuclear energy for fears of accidents, despite these being extremely unlikely to happen. Indeed, opposers know that when nuclear does fail, it can fail spectacularly. They were reminded of this in 2011, when the Fukushima disaster, despite not killing anyone directly, led to the displacement of more than 150,000 people, thousands of evacuation/related deaths and billions of dollars in cleanup costs.

Lastly, if compared to other sources of energy, nuclear power is one of the most expensive and time-consuming forms of energy. Nuclear plants cost billions of dollars to build and they take much longer than any other infrastructure for renewable energy, sometimes even more than a decade. However, while nuclear power plants are expensive to build, they are relatively cheap to run , a factor that improves its competitiveness. Still, the long building process is considered a significant obstacle in the run to net-zero emissions that countries around the world have committed to. If they hope to meet their emission reduction targets in time, they cannot afford to rely on new nuclear plants.

You might also like: The Nuclear Waste Disposal Dilemma

Who Wins the Nuclear Debate?

There are a multitude of advantages and disadvantages of nuclear energy and the debate on whether to keep this technology or find other alternatives is destined to continue in the years to come. Nuclear power can be a highly destructive weapon, but the risks of a nuclear catastrophe are relatively low. While historic nuclear disasters can be counted on the fingers of a single hand, they are remembered for their devastating impact and the life-threatening consequences they sparked (or almost sparked). However, it is important to remember that fossil fuels like coal and oil represent a much bigger threat and silently kill millions of people every year worldwide. Another big aspect to take into account, and one that is currently discussed by global leaders, is the dependence of some of the world’s largest economies on countries like Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq for fossil fuels. While the 2011 Fukushima disaster, for example, pushed the then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel to close all of Germany’s nuclear plants, her decision only increased the country’s dependence on much more polluting Russian oil. Nuclear supporters argue that relying on nuclear energy would decrease the energy dependency from third countries. However, raw materials such as the uranium needed to make plants function would still need to be imported from countries like Canada, Kazakhstan, and Australia. The debate thus shifts to another problem: which countries should we rely on for imports and, most importantly, is it worth keeping these dependencies?

This story is funded by readers like you

Our non-profit newsroom provides climate coverage free of charge and advertising. Your one-off or monthly donations play a crucial role in supporting our operations, expanding our reach, and maintaining our editorial independence.

About EO | Mission Statement | Impact & Reach | Write for us

About the Author

Martina Igini

What the Future of Renewable Energy Looks Like

Top 7 Smart Cities in the World in 2024

Cobalt Mining: The Dark Side of the Renewable Energy Transition

Hand-picked stories weekly or monthly. We promise, no spam!

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Boost this article By donating us $100, $50 or subscribe to Boosting $10/month – we can get this article and others in front of tens of thousands of specially targeted readers. This targeted Boosting – helps us to reach wider audiences – aiming to convince the unconvinced, to inform the uninformed, to enlighten the dogmatic.

The Understand Energy Learning Hub is a cross-campus effort of the Precourt Institute for Energy .

Introduction to Nuclear Energy

Exploring our content.

Fast Facts View our summary of key facts and information.

Our Lecture Watch the Stanford course lecture.

Fast Facts About Nuclear Energy

Principal Energy Use: Electricity

Nuclear energy is a carbon-free and extremely energy dense resource that produces no air pollution . Nuclear reactions produce large amounts of energy in the form of heat. That heat can be used to power a steam turbine and generate electricity. There are two types of nuclear reactions:

- Nuclear fission occurs when a large atom is split into smaller atoms, producing lots of heat and long-lived radioactive waste . See our Nuclear Fission page for more information.

- Nuclear fusion occurs when two nuclei combine to form a single nucleus, releasing massive amounts of heat with no long-lived radioactive waste (the sun is a nuclear fusion reactor). See our Nuclear Fusion page for more information.

All commercial nuclear power plants today use nuclear fission. The highly radioactive byproducts of nuclear fission must be secured away from people for hundreds of thousands of years, but we have no proven long term solutions for doing that. Nuclear fusion is still in the research phase.

Both nuclear fission and nuclear fusion have benefited from large amounts of government funding for basic science, technology, fuel-sourcing, and regulation; and both forms have origins in the defense industry (nuclear bombs - fission; hydrogen bombs - fission and fusion).

Fission and Fusion Characteristics

Climate impact: low.

- Near-zero emissions (fission and fusion)

Environmental Impact: Low to Medium

- No air pollution (fission and fusion)

- Radioactive waste is toxic for hundreds of thousands of years

- Risk of radiation leaks from nuclear meltdowns

- Large amounts of water used for cooling; thermal pollution of water

- Mining of uranium can pollute water and degrade land and habitat

- Nuclear waste can be used for bombs; high security required to reduce the risk of proliferation

- No long-lived radioactive waste

Updated October 2023

Our Lecture on Introduction to Nuclear Energy

This is our Stanford University Understand Energy course introduction to nuclear energy. We encourage you to watch this 5-minute video for important context before diving into the more in-depth content on our Nuclear Fission and Nuclear Fusion pages.

Presented by: Diana Gragg, PhD ; Core Lecturer, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Stanford University; Explore Energy Managing Director, Precourt Institute for Energy Recorded on: September 13, 2023 Duration: 5 minutes

Lecture slides available upon request .

Next Topic: Nuclear Fission Other Energy Topics to Explore

Fast Facts Sources Overview: Breeze, P. Power generation technologies, 3 rd . edition. Newnes, 2019; What is Nuclear Energy? The Science of Nuclear Power . IAEA, 2022; Nuclear Explained . EIA, 2022; Nuclear Fusion Power . WNA, 2022. Chart of Characteristics: Fission vs Fusion: What's the Difference? DOE, 2019; Nuclear Power for Electrical Generation . NRC; Nuclear Explained . EIA, 2022; Nuclear Power in the World Today. WNA, 2023; Fusion Device Information System . n.d. More details available on request . Back to Fast Facts

Create an account

Create a free IEA account to download our reports or subcribe to a paid service.

Nuclear Power in a Clean Energy System

About this report.

With nuclear power facing an uncertain future in many countries, the world risks a steep decline in its use in advanced economies that could result in billions of tonnes of additional carbon emissions. Some countries have opted out of nuclear power in light of concerns about safety and other issues. Many others, however, still see a role for nuclear in their energy transitions but are not doing enough to meet their goals.

The publication of the IEA's first report addressing nuclear power in nearly two decades brings this important topic back into the global energy debate.

Key findings

Nuclear power is the second-largest source of low-carbon electricity today.

Nuclear power is the second-largest source of low-carbon electricity today, with 452 operating reactors providing 2700 TWh of electricity in 2018, or 10% of global electricity supply.

In advanced economies, nuclear has long been the largest source of low-carbon electricity, providing 18% of supply in 2018. Yet nuclear is quickly losing ground. While 11.2 GW of new nuclear capacity was connected to power grids globally in 2018 – the highest total since 1990 – these additions were concentrated in China and Russia.

Global low-carbon power generation by source, 2018

Cumulative co2 emissions avoided by global nuclear power in selected countries, 1971-2018, an aging nuclear fleet.

In the absense of further lifetime extensions and new projects could result in an additional 4 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions, underlining the importance of the nuclear fleet to low-carbon energy transitions around the globe. In emerging and developing economies, particularly China, the nuclear fleet will provide low-carbon electricity for decades to come.

However the nuclear fleet in advanced economies is 35 years old on average and many plants are nearing the end of their designed lifetimes. Given their age, plants are beginning to close, with 25% of existing nuclear capacity in advanced economies expected to be shut down by 2025.

It is considerably cheaper to extend the life of a reactor than build a new plant, and costs of extensions are competitive with other clean energy options, including new solar PV and wind projects. Nevertheless they still represent a substantial capital investment. The estimated cost of extending the operational life of 1 GW of nuclear capacity for at least 10 years ranges from $500 million to just over $1 billion depending on the condition of the site.

However difficult market conditions are a barrier to lifetime extension investments. An extended period of low wholesale electricity prices in most advanced economies has sharply reduced or eliminated margins for many technologies, putting nuclear at risk of shutting down early if additional investments are needed. As such, the feasibility of extensions depends largely on domestic market conditions.

Age profile of nuclear power capacity in selected regions, 2019

United states, levelised cost of electricity in the united states, 2040, european union, levelised cost of electricity in the european union, 2040, levelised cost of electricity in japan, 2040, the nuclear fade case, nuclear capacity operating in selected advanced economies in the nuclear fade case, 2018-2040, wind and solar pv generation by scenario 2019-2040, policy recommendations.

In this context, countries that intend to retain the option of nuclear power should consider the following actions:

- Keep the option open: Authorise lifetime extensions of existing nuclear plants for as long as safely possible.

- Value dispatchability: Design the electricity market in a way that properly values the system services needed to maintain electricity security, including capacity availability and frequency control services. Make sure that the providers of these services, including nuclear power plants, are compensated in a competitive and non-discriminatory manner.

- Value non-market benefits: Establish a level playing field for nuclear power with other low-carbon energy sources in recognition of its environmental and energy security benefits and remunerate it accordingly.

- Update safety regulations: Where necessary, update safety regulations in order to ensure the continued safe operation of nuclear plants. Where technically possible, this should include allowing flexible operation of nuclear power plants to supply ancillary services.

- Create a favourable financing framework: Create risk management and financing frameworks that facilitate the mobilisation of capital for new and existing plants at an acceptable cost taking the risk profile and long time-horizons of nuclear projects into consideration.

- Support new construction: Ensure that licensing processes do not lead to project delays and cost increases that are not justified by safety requirements.

- Support innovative new reactor designs: Accelerate innovation in new reactor designs with lower capital costs and shorter lead times and technologies that improve the operating flexibility of nuclear power plants to facilitate the integration of growing wind and solar capacity into the electricity system.

- Maintain human capital: Protect and develop the human capital and project management capabilities in nuclear engineering.

Executive summary

Nuclear power can play an important role in clean energy transitions.

Nuclear power today makes a significant contribution to electricity generation, providing 10% of global electricity supply in 2018. In advanced economies 1 , nuclear power accounts for 18% of generation and is the largest low-carbon source of electricity. However, its share of global electricity supply has been declining in recent years. That has been driven by advanced economies, where nuclear fleets are ageing, additions of new capacity have dwindled to a trickle, and some plants built in the 1970s and 1980s have been retired. This has slowed the transition towards a clean electricity system. Despite the impressive growth of solar and wind power, the overall share of clean energy sources in total electricity supply in 2018, at 36%, was the same as it was 20 years earlier because of the decline in nuclear. Halting that slide will be vital to stepping up the pace of the decarbonisation of electricity supply.

A range of technologies, including nuclear power, will be needed for clean energy transitions around the world. Global energy is increasingly based around electricity. That means the key to making energy systems clean is to turn the electricity sector from the largest producer of CO 2 emissions into a low-carbon source that reduces fossil fuel emissions in areas like transport, heating and industry. While renewables are expected to continue to lead, nuclear power can also play an important part along with fossil fuels using carbon capture, utilisation and storage. Countries envisaging a future role for nuclear account for the bulk of global energy demand and CO 2 emissions. But to achieve a trajectory consistent with sustainability targets – including international climate goals – the expansion of clean electricity would need to be three times faster than at present. It would require 85% of global electricity to come from clean sources by 2040, compared with just 36% today. Along with massive investments in efficiency and renewables, the trajectory would need an 80% increase in global nuclear power production by 2040.

Nuclear power plants contribute to electricity security in multiple ways. Nuclear plants help to keep power grids stable. To a certain extent, they can adjust their operations to follow demand and supply shifts. As the share of variable renewables like wind and solar photovoltaics (PV) rises, the need for such services will increase. Nuclear plants can help to limit the impacts from seasonal fluctuations in output from renewables and bolster energy security by reducing dependence on imported fuels.

Lifetime extensions of nuclear power plants are crucial to getting the energy transition back on track

Policy and regulatory decisions remain critical to the fate of ageing reactors in advanced economies. The average age of their nuclear fleets is 35 years. The European Union and the United States have the largest active nuclear fleets (over 100 gigawatts each), and they are also among the oldest: the average reactor is 35 years old in the European Union and 39 years old in the United States. The original design lifetime for operations was 40 years in most cases. Around one quarter of the current nuclear capacity in advanced economies is set to be shut down by 2025 – mainly because of policies to reduce nuclear’s role. The fate of the remaining capacity depends on decisions about lifetime extensions in the coming years. In the United States, for example, some 90 reactors have 60-year operating licenses, yet several have already been retired early and many more are at risk. In Europe, Japan and other advanced economies, extensions of plants’ lifetimes also face uncertain prospects.

Economic factors are also at play. Lifetime extensions are considerably cheaper than new construction and are generally cost-competitive with other electricity generation technologies, including new wind and solar projects. However, they still need significant investment to replace and refurbish key components that enable plants to continue operating safely. Low wholesale electricity and carbon prices, together with new regulations on the use of water for cooling reactors, are making some plants in the United States financially unviable. In addition, markets and regulatory systems often penalise nuclear power by not pricing in its value as a clean energy source and its contribution to electricity security. As a result, most nuclear power plants in advanced economies are at risk of closing prematurely.

The hurdles to investment in new nuclear projects in advanced economies are daunting

What happens with plans to build new nuclear plants will significantly affect the chances of achieving clean energy transitions. Preventing premature decommissioning and enabling longer extensions would reduce the need to ramp up renewables. But without new construction, nuclear power can only provide temporary support for the shift to cleaner energy systems. The biggest barrier to new nuclear construction is mobilising investment. Plans to build new nuclear plants face concerns about competitiveness with other power generation technologies and the very large size of nuclear projects that require billions of dollars in upfront investment. Those doubts are especially strong in countries that have introduced competitive wholesale markets.

A number of challenges specific to the nature of nuclear power technology may prevent investment from going ahead. The main obstacles relate to the sheer scale of investment and long lead times; the risk of construction problems, delays and cost overruns; and the possibility of future changes in policy or the electricity system itself. There have been long delays in completing advanced reactors that are still being built in Finland, France and the United States. They have turned out to cost far more than originally expected and dampened investor interest in new projects. For example, Korea has a much better record of completing construction of new projects on time and on budget, although the country plans to reduce its reliance on nuclear power.

Without nuclear investment, achieving a sustainable energy system will be much harder

A collapse in investment in existing and new nuclear plants in advanced economies would have implications for emissions, costs and energy security. In the case where no further investments are made in advanced economies to extend the operating lifetime of existing nuclear power plants or to develop new projects, nuclear power capacity in those countries would decline by around two-thirds by 2040. Under the current policy ambitions of governments, while renewable investment would continue to grow, gas and, to a lesser extent, coal would play significant roles in replacing nuclear. This would further increase the importance of gas for countries’ electricity security. Cumulative CO 2 emissions would rise by 4 billion tonnes by 2040, adding to the already considerable difficulties of reaching emissions targets. Investment needs would increase by almost USD 340 billion as new power generation capacity and supporting grid infrastructure is built to offset retiring nuclear plants.

Achieving the clean energy transition with less nuclear power is possible but would require an extraordinary effort. Policy makers and regulators would have to find ways to create the conditions to spur the necessary investment in other clean energy technologies. Advanced economies would face a sizeable shortfall of low-carbon electricity. Wind and solar PV would be the main sources called upon to replace nuclear, and their pace of growth would need to accelerate at an unprecedented rate. Over the past 20 years, wind and solar PV capacity has increased by about 580 GW in advanced economies. But in the next 20 years, nearly five times that much would need to be built to offset nuclear’s decline. For wind and solar PV to achieve that growth, various non-market barriers would need to be overcome such as public and social acceptance of the projects themselves and the associated expansion in network infrastructure. Nuclear power, meanwhile, can contribute to easing the technical difficulties of integrating renewables and lowering the cost of transforming the electricity system.

With nuclear power fading away, electricity systems become less flexible. Options to offset this include new gas-fired power plants, increased storage (such as pumped storage, batteries or chemical technologies like hydrogen) and demand-side actions (in which consumers are encouraged to shift or lower their consumption in real time in response to price signals). Increasing interconnection with neighbouring systems would also provide additional flexibility, but its effectiveness diminishes when all systems in a region have very high shares of wind and solar PV.

Offsetting less nuclear power with more renewables would cost more

Taking nuclear out of the equation results in higher electricity prices for consumers. A sharp decline in nuclear in advanced economies would mean a substantial increase in investment needs for other forms of power generation and the electricity network. Around USD 1.6 trillion in additional investment would be required in the electricity sector in advanced economies from 2018 to 2040. Despite recent declines in wind and solar costs, adding new renewable capacity requires considerably more capital investment than extending the lifetimes of existing nuclear reactors. The need to extend the transmission grid to connect new plants and upgrade existing lines to handle the extra power output also increases costs. The additional investment required in advanced economies would not be offset by savings in operational costs, as fuel costs for nuclear power are low, and operation and maintenance make up a minor portion of total electricity supply costs. Without widespread lifetime extensions or new projects, electricity supply costs would be close to USD 80 billion higher per year on average for advanced economies as a whole.

Strong policy support is needed to secure investment in existing and new nuclear plants

Countries that have kept the option of using nuclear power need to reform their policies to ensure competition on a level playing field. They also need to address barriers to investment in lifetime extensions and new capacity. The focus should be on designing electricity markets in a way that values the clean energy and energy security attributes of low-carbon technologies, including nuclear power.

Securing investment in new nuclear plants would require more intrusive policy intervention given the very high cost of projects and unfavourable recent experiences in some countries. Investment policies need to overcome financing barriers through a combination of long-term contracts, price guarantees and direct state investment.

Interest is rising in advanced nuclear technologies that suit private investment such as small modular reactors (SMRs). This technology is still at the development stage. There is a case for governments to promote it through funding for research and development, public-private partnerships for venture capital and early deployment grants. Standardisation of reactor designs would be crucial to benefit from economies of scale in the manufacturing of SMRs.

Continued activity in the operation and development of nuclear technology is required to maintain skills and expertise. The relatively slow pace of nuclear deployment in advanced economies in recent years means there is a risk of losing human capital and technical know-how. Maintaining human skills and industrial expertise should be a priority for countries that aim to continue relying on nuclear power.

The following recommendations are directed at countries that intend to retain the option of nuclear power. The IEA makes no recommendations to countries that have chosen not to use nuclear power in their clean energy transition and respects their choice to do so.

- Keep the option open: Authorise lifetime extensions of existing nuclear plants for as long as safely possible.

- Value non-market benefits: Establish a level playing field for nuclear power with other low carbon energy sources in recognition of its environmental and energy security benefits and remunerate it accordingly.

- Create an attractive financing framework: Set up risk management and financing frameworks that can help mobilise capital for new and existing plants at an acceptable cost, taking the risk profile and long time horizons of nuclear projects into consideration.

- Support new construction: Ensure that licensing processes do not lead to project delays and cost increases that are not justified by safety requirements. Support standardisation and enable learning-by-doing across the industry.

- Support innovative new reactor designs: Accelerate innovation in new reactor designs, such as small modular reactors (SMRs), with lower capital costs and shorter lead times and technologies that improve the operating flexibility of nuclear power plants to facilitate the integration of growing wind and solar capacity into the electricity system.

Advanced economies consist of Australia, Canada, Chile, the 28 members of the European Union, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States.

Reference 1

Cite report.

IEA (2019), Nuclear Power in a Clean Energy System , IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/nuclear-power-in-a-clean-energy-system, Licence: CC BY 4.0

Share this report

- Share on Twitter Twitter

- Share on Facebook Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn LinkedIn

- Share on Email Email

- Share on Print Print

Subscription successful

Thank you for subscribing. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the link at the bottom of any IEA newsletter.

Back to the Future Josh Freed

Leslie and mark's old/new idea.

The Nuclear Science and Engineering Library at MIT is not a place where most people would go to unwind. It’s filled with journals that have articles with titles like “Longitudinal double-spin asymmetry of electrons from heavy flavor decays in polarized p + p collisions at √s = 200 GeV.” But nuclear engineering Ph.D. candidates relax in ways all their own. In the winter of 2009, two of those candidates, Leslie Dewan and Mark Massie, were studying for their qualifying exams—a brutal rite of passage—and had a serious need to decompress.

To clear their heads after long days and nights of reviewing neutron transport, the mathematics behind thermohydraulics, and other such subjects, they browsed through the crinkled pages of journals from the first days of their industry—the glory days. Reading articles by scientists working in the 1950s and ‘60s, they found themselves marveling at the sense of infinite possibility those pioneers had brought to their work, in awe of the huge outpouring of creative energy. They were also curious about the dozens of different reactor technologies that had once been explored, only to be abandoned when the funding dried up.

The early nuclear researchers were all housed in government laboratories—at Oak Ridge in Tennessee, at the Idaho National Lab in the high desert of eastern Idaho, at Argonne in Chicago, and Los Alamos in New Mexico. Across the country, the nation’s top physicists, metallurgists, mathematicians, and engineers worked together in an atmosphere of feverish excitement, as government support gave them the freedom to explore the furthest boundaries of their burgeoning new field. Locked in what they thought of as a life-or-death race with the Soviet Union, they aimed to be first in every aspect of scientific inquiry, especially those that involved atom splitting.

1955: Argonne's BORAX III reactor provided all the electricity for Arco, Idaho, the first time any community's electricity was provided entirely by nuclear energy. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Though nuclear engineers were mostly men in those days, Leslie imagined herself working alongside them, wearing a white lab coat, thinking big thoughts. “It was all so fresh, so exciting, so limitless back then,” she told me. “They were designing all sorts of things: nuclear-powered cars and airplanes, reactors cooled by lead. Today, it’s much less interesting. Most of us are just working on ways to tweak basically the same light water reactor we’ve been building for 50 years.”

1958: The Ford Nucleon scale-model concept car developed by Ford Motor Company as a design of how a nuclear-powered car might look. Source: Wikimedia Commons

But because of something that she and Mark stumbled across in the library during one of their forays into the old journals, Leslie herself is not doing that kind of tweaking—she’s trying to do something much more radical. One night, Mark showed Leslie a 50-year-old paper from Oak Ridge about a reactor powered not by rods of metal-clad uranium pellets in water, like the light water reactors of today, but by a liquid fuel of uranium mixed into molten salt to keep it at a constant temperature. The two were intrigued, because it was clear from the paper that the molten salt design could potentially be constructed at a lower cost and shut down more easily in an emergency than today’s light water reactors. And the molten salt design wasn’t just theoretical—Oak Ridge had built a real reactor, which ran from 1965-1969, racking up 20,000 operating hours.

The 1960s-era salt reactor was interesting, but at first blush it didn’t seem practical enough to revive. It was bulky, expensive, and not very efficient. Worse, it ran on uranium enriched to levels far above the modern legal limit for commercial nuclear power. Most modern light water reactors run on 5 percent enriched uranium, and it is illegal under international and domestic law for commercial power generators to use anything above 20 percent, because at levels that high uranium can be used for making weapons. The Oak Ridge molten salt reactor needed uranium enriched to at least 33 percent, possibly even higher.

Aircraft Reactor Experiment building at ORNL (Extensive research into molten salt reactors started with the U.S. aircraft reactor experiment (ARE) in support of the U.S. Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion program.) Wikimedia Commons

1964: Molten salt reactor at Oak Ridge. Source: Wikimedia Commons

But they were aware that smart young engineers were considering applying modern technology to several other decades-old reactor designs from the dawn of the nuclear age, and this one seemed to Leslie and Mark to warrant a second look. After finishing their exams, they started searching for new materials that could be used in a molten salt reactor to make it both legal and more efficient. If they could show that a modified version of the old design could compete with—or exceed—the performance of today’s light water reactors, they knew they might have a very interesting project on their hands.

First, they took a look at the fuel. By using different, more modern materials, they had a theory that they could get the reactor to work at very low enrichment levels. Maybe, they hoped, even significantly below 5 percent.

There was a good reason to hope. Today’s reactors produce a significant amount of nuclear “waste,” many tons of which are currently sitting in cooling pools and storage canisters at plant sites all over the country. The reason that the waste has to be managed so carefully is that when they are discarded, the uranium fuel rods contain about 95 percent of the original amount of energy and remain both highly radioactive and hot enough to boil water. It dawned on Leslie and Mark that if they could chop up the rods and remove their metal cladding, they might have a “killer app”—a sector-redefining technology like Uber or Airbnb—for their molten salt reactor design, enabling it to run on the waste itself.

By late 2010, the computer modeling they were doing suggested this might indeed work. When Leslie left for a trip to Egypt with her family in January 2011, Mark kept running simulations back at MIT. On January 11, he sent his partner an email that she read as she toured the sites of Alexandria. The note was highly technical, but said in essence that Mark’s latest work confirmed their hunch—they could indeed make their reactor run on nuclear waste. Leslie looked up from her phone and said to her brother: “I need to go back to Boston.”

Watch Leslie Dewan and Mark Massie on the future of nuclear energy

Climate Change Spurs New Call for Nuclear Energy

In the days when Leslie and Mark were studying for their exams, it may have seemed that the Golden Age of nuclear energy in the United States had long since passed. Not a single new commercial reactor project had been built here in over 30 years. Not only were there no new reactors, but with the fracking boom having produced abundant supplies of cheap natural gas, some electric utilities were shutting down their aging reactors rather than doing the costly upgrades needed to keep them online.

As the domestic reactor market went into decline, the American supply chain for nuclear reactor parts withered. Although almost all commercial nuclear technology had been discovered in the United States, our competitors eventually purchased much of our nuclear industrial base, with Toshiba buying Westinghouse, for example.* Not surprisingly, as the nuclear pioneers aged and young scientists stayed away from what seemed to be a dying industry, the number of nuclear engineers also dwindled over the decades. In addition, the American regulatory system, long considered the gold standard for western nuclear systems, began to lose influence as other countries pressed ahead with new reactor construction while the U.S. market remained dormant.

Yet something has changed in recent years. Leslie and Mark are not really outliers. All of a sudden, a flood of young engineers has entered the field. More than 1,164 nuclear engineering degrees were awarded in 2013—a 160 percent increase over the number granted a decade ago.

So what, after a 30-year drought, is drawing smart young people back to the nuclear industry? The answer is climate change. Nuclear energy currently provides about 20 percent of the electric power in the United States, and it does so without emitting any greenhouse gases. Compare that to the amount of electricity produced by the other main non-emitting sources of power, the so-called “renewables”—hydroelectric (6.8 percent), wind (4.2 percent) and solar (about one quarter of a percent). Not only are nuclear plants the most important of the non-emitting sources, but they provide baseload—“always there”—power, while most renewables can produce electricity only intermittently, when the wind is blowing or the sun is shining.

In 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a United Nations-based organization that is the leading international body for the assessment of climate risk, issued a desperate call for more non-emitting power sources. According to the IPCC, in order to mitigate climate change and meet growing energy demands, the world must aggressively expand its sources of renewable energy, and it must also build more than 400 new nuclear reactors in the next 20 years—a near-doubling of today’s global fleet of 435 reactors. However, in the wake of the tsunami that struck Japan’s Fukushima Daichi plant in 2011, some countries are newly fearful about the safety of light water reactors. Germany, for example, vowed to shutter its entire nuclear fleet.

November 6, 2013: The spent fuel pool inside the No.4 reactor building at the tsunami-crippled Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s (TEPCO) Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Source: REUTERS/Kyodo (Japan)

The young scientists entering the nuclear energy field know all of this. They understand that a major build-out of nuclear reactors could play a vital role in saving the world from climate disaster. But they also recognize that for that to happen, there must be significant changes in the technology of the reactors, because fear of light water reactors means that the world is not going to be willing to fund and build enough of them to supply the necessary energy. That’s what had sent Leslie and Mark into the library stacks at MIT—a search for new ideas that might be buried in the old designs.

They have now launched a company, Transatomic, to build the molten salt reactor they see as a viable answer to the problem. And they’re not alone—at least eight other startups have emerged in recent years, each with its own advanced reactor design. This new generation of pioneers is working with the same sense of mission and urgency that animated the discipline’s founders. The existential threat that drove the men of Oak Ridge and Argonne was posed by the Soviets; the threat of today is from climate change.

Heeding that sense of urgency, investors from Silicon Valley and elsewhere are stepping up to provide funding. One startup, TerraPower, has the backing of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates and former Microsoft executive Nathan Myhrvold. Another, General Fusion, has raised $32 million from investors, including nearly $20 million from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. And LPP Fusion has even benefited, to the tune of $180,000, from an Indiegogo crowd-funding campaign.

All of the new blood, new ideas, and new money are having a real effect. In the last several years, a field that had been moribund has become dynamic again, once more charged with a feeling of boundless possibility and optimism.

But one huge source of funding and support enjoyed by those first pioneers has all but disappeared: The U.S. government.

The "Atoms for Peace" program supplied equipment and information to schools, hospitals, and research institutions within the U.S. and throughout the world. Source: Wikipedia

From Atoms for Peace to Chernobyl

December 8, 1953: U.S. President Eisenhower delivers his "Atoms for Peace" speech to the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Source: IAEA

In the early days of nuclear energy development, the government led the charge, funding the research, development, and design of 52 different reactors at the Idaho laboratory’s National Reactor Testing Station alone, not to mention those that were being developed at other labs, like the one that was the subject of the paper Leslie and Mark read. With the help of the government, engineers were able to branch out in many different directions.

Soon enough, the designs were moving from paper to test reactors to deployment at breathtaking speed. The tiny Experimental Breeder Reactor 1, which went online in December 1951 at the Idaho National Lab, ushered in the age of nuclear energy.

Just two years later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower made his Atoms for Peace speech to the U.N., in which he declared that “The United States knows that peaceful power from atomic energy is no dream of the future. The capability, already proved, is here today.” Less than a year after that, Eisenhower waved a ceremonial "neutron wand" to signal a bulldozer in Shippingport, Pennsylvania to begin construction of the nation’s first commercial nuclear power plant.

1956: Reactor pressure vessel during construction at the Shippingport Atomic Power Station. Source: Wikipedia

By 1957 the Atoms for Peace program had borne fruit, and Shippingport was open for business. During the years that followed, the government, fulfilling Eisenhower’s dream, not only funded the research, it ran the labs, chose the technologies, and, eventually, regulated the reactors.

The U.S. would soon rapidly surpass not only its Cold War enemy, the Soviet Union, which had brought the first significant electricity-producing reactor online in 1954, but every other country seeking to deploy nuclear energy, including France and Canada. Much of the extraordinary progress in America’s development of nuclear energy technology can be credited to one specific government institution—the U.S. Navy.

Rickover’s choice has had enormous implications. To this day, the light water reactor remains the standard—the only type of reactor built or used for energy production in the United States and in most other countries as well. Research on other reactor types (like molten salt and lead) essentially ended for almost six decades, not to be revived until very recently.

Once light water reactors got the nod, the Atomic Energy Commission endorsed a cookie-cutter-like approach to building additional reactors that was very enticing to energy companies seeking to enter the atomic arena. Having a standardized light water reactor design meant quicker regulatory approval, economies of scale, and operating uniformity, which helped control costs and minimize uncertainty. And there was another upside to the light water reactors, at least back then: they produced a byproduct—plutonium. These days, we call that a problem: the remaining fissile material that must be protected from accidental discharge or proliferation and stored indefinitely. In the Cold War 1960s, however, that was seen as a benefit, because the leftover plutonium could be used to make nuclear weapons.

2005: An ICBM loaded into a silo of the former ICBM missile site, now the Titan Missile Museum. Source: Wikipedia

With the triumph of the light water reactor came a massive expansion of the domestic and global nuclear energy industries. In the 1960s and ‘70s, America’s technology, design, supply chain, and regulatory system dominated the production of all civilian nuclear energy on this side of the Iron Curtain. U.S. engineers drew the plans, U.S. companies like Westinghouse and GE built the plants, U.S. factories and mills made the parts, and the U.S. government’s Atomic Energy Commission set the global safety standards.

In this country, we built more than 100 light water reactors for commercial power production. Though no two American plants were identical, all of the plants constructed in that era were essentially the same—light water reactors running on uranium enriched to about 4 percent. By the end of the 1970s, in addition to the 100-odd reactors that had been built, 100 more were in the planning or early construction stage.

And then everything came to a screeching halt, thanks to a bizarre confluence of Hollywood and real life.