Examples of 'assignment' in a sentence

Examples from collins dictionaries, examples from the collins corpus.

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

All ENGLISH words that begin with 'A'

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of assignment

task , duty , job , chore , stint , assignment mean a piece of work to be done.

task implies work imposed by a person in authority or an employer or by circumstance.

duty implies an obligation to perform or responsibility for performance.

job applies to a piece of work voluntarily performed; it may sometimes suggest difficulty or importance.

chore implies a minor routine activity necessary for maintaining a household or farm.

stint implies a carefully allotted or measured quantity of assigned work or service.

assignment implies a definite limited task assigned by one in authority.

Examples of assignment in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'assignment.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

see assign entry 1

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing assignment

- self - assignment

Dictionary Entries Near assignment

Cite this entry.

“Assignment.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/assignment. Accessed 14 Apr. 2024.

Legal Definition

Legal definition of assignment, more from merriam-webster on assignment.

Nglish: Translation of assignment for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of assignment for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 12, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of assignment noun from the Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

Definitions on the go

Look up any word in the dictionary offline, anytime, anywhere with the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Examples of assign

Word of the Day

pitch-perfect

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

singing each musical note perfectly, at exactly the right pitch (= level)

Alike and analogous (Talking about similarities, Part 1)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

{{message}}

There was a problem sending your report.

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that he or she will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove her point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, he or she still has to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and she already knows everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality she or he expects.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Module 4: Writing in College

Writing assignments, learning objectives.

- Describe common types and expectations of writing tasks given in a college class

Figure 1 . All college classes require some form of writing. Investing some time in refining your writing skills so that you are a more confident, skilled, and efficient writer will pay dividends in the long run.

What to Do With Writing Assignments

Writing assignments can be as varied as the instructors who assign them. Some assignments are explicit about what exactly you’ll need to do, in what order, and how it will be graded. Others are more open-ended, leaving you to determine the best path toward completing the project. Most fall somewhere in the middle, containing details about some aspects but leaving other assumptions unstated. It’s important to remember that your first resource for getting clarification about an assignment is your instructor—they will be very willing to talk out ideas with you, to be sure you’re prepared at each step to do well with the writing.

Writing in college is usually a response to class materials—an assigned reading, a discussion in class, an experiment in a lab. Generally speaking, these writing tasks can be divided into three broad categories: summary assignments, defined-topic assignments, and undefined-topic assignments.

Link to Learning

Empire State College offers an Assignment Calculator to help you plan ahead for your writing assignment. Just plug in the date you plan to get started and the date it is due, and the calculator will help break it down into manageable chunks.

Summary Assignments

Being asked to summarize a source is a common task in many types of writing. It can also seem like a straightforward task: simply restate, in shorter form, what the source says. A lot of advanced skills are hidden in this seemingly simple assignment, however.

An effective summary does the following:

- reflects your accurate understanding of a source’s thesis or purpose

- differentiates between major and minor ideas in a source

- demonstrates your ability to identify key phrases to quote

- shows your ability to effectively paraphrase most of the source’s ideas

- captures the tone, style, and distinguishing features of a source

- does not reflect your personal opinion about the source

That last point is often the most challenging: we are opinionated creatures, by nature, and it can be very difficult to keep our opinions from creeping into a summary. A summary is meant to be completely neutral.

In college-level writing, assignments that are only summary are rare. That said, many types of writing tasks contain at least some element of summary, from a biology report that explains what happened during a chemical process, to an analysis essay that requires you to explain what several prominent positions about gun control are, as a component of comparing them against one another.

Writing Effective Summaries

Start with a clear identification of the work.

This automatically lets your readers know your intentions and that you’re covering the work of another author.

- In the featured article “Five Kinds of Learning,” the author, Holland Oates, justifies his opinion on the hot topic of learning styles — and adds a few himself.

Summarize the Piece as a Whole

Omit nothing important and strive for overall coherence through appropriate transitions. Write using “summarizing language.” Your reader needs to be reminded that this is not your own work. Use phrases like the article claims, the author suggests, etc.

- Present the material in a neutral fashion. Your opinions, ideas, and interpretations should be left in your brain — don’t put them into your summary. Be conscious of choosing your words. Only include what was in the original work.

- Be concise. This is a summary — it should be much shorter than the original piece. If you’re working on an article, give yourself a target length of 1/4 the original article.

Conclude with a Final Statement

This is not a statement of your own point of view, however; it should reflect the significance of the book or article from the author’s standpoint.

- Without rewriting the article, summarize what the author wanted to get across. Be careful not to evaluate in the conclusion or insert any of your own assumptions or opinions.

Understanding the Assignment and Getting Started

Figure 2 . Many writing assignments will have a specific prompt that sends you first to your textbook, and then to outside resources to gather information.

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt —will explain the purpose of the assignment and the required parameters (length, number and type of sources, referencing style, etc.).

Also, don’t forget to check the rubric, if there is one, to understand how your writing will be assessed. After analyzing the prompt and the rubric, you should have a better sense of what kind of writing you are expected to produce.

Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment! In a situation like that, consider the following tips:

- Focus on the verbs . Look for verbs like compare, explain, justify, reflect , or the all-purpose analyze . You’re not just producing a paper as an artifact; you’re conveying, in written communication, some intellectual work you have done. So the question is, what kind of thinking are you supposed to do to deepen your learning?

- Put the assignment in context . Many professors think in terms of assignment sequences. For example, a social science professor may ask you to write about a controversial issue three times: first, arguing for one side of the debate; second, arguing for another; and finally, from a more comprehensive and nuanced perspective, incorporating text produced in the first two assignments. A sequence like that is designed to help you think through a complex issue. If the assignment isn’t part of a sequence, think about where it falls in the span of the course (early, midterm, or toward the end), and how it relates to readings and other assignments. For example, if you see that a paper comes at the end of a three-week unit on the role of the Internet in organizational behavior, then your professor likely wants you to synthesize that material.

- Try a free-write . A free-write is when you just write, without stopping, for a set period of time. That doesn’t sound very “free”; it actually sounds kind of coerced, right? The “free” part is what you write—it can be whatever comes to mind. Professional writers use free-writing to get started on a challenging (or distasteful) writing task or to overcome writer’s block or a powerful urge to procrastinate. The idea is that if you just make yourself write, you can’t help but produce some kind of useful nugget. Thus, even if the first eight sentences of your free write are all variations on “I don’t understand this” or “I’d really rather be doing something else,” eventually you’ll write something like “I guess the main point of this is…,” and—booyah!—you’re off and running.

- Ask for clarification . Even the most carefully crafted assignments may need some verbal clarification, especially if you’re new to a course or field. Professors generally love questions, so don’t be afraid to ask. Try to convey to your instructor that you want to learn and you’re ready to work, and not just looking for advice on how to get an A.

Defined-Topic Assignments

Many writing tasks will ask you to address a particular topic or a narrow set of topic options. Defined-topic writing assignments are used primarily to identify your familiarity with the subject matter. (Discuss the use of dialect in Their Eyes Were Watching God , for example.)

Remember, even when you’re asked to “show how” or “illustrate,” you’re still being asked to make an argument. You must shape and focus your discussion or analysis so that it supports a claim that you discovered and formulated and that all of your discussion and explanation develops and supports.

Undefined-Topic Assignments

Another writing assignment you’ll potentially encounter is one in which the topic may be only broadly identified (“water conservation” in an ecology course, for instance, or “the Dust Bowl” in a U.S. History course), or even completely open (“compose an argumentative research essay on a subject of your choice”).

Figure 3 . For open-ended assignments, it’s best to pick something that interests you personally.

Where defined-topic essays demonstrate your knowledge of the content , undefined-topic assignments are used to demonstrate your skills— your ability to perform academic research, to synthesize ideas, and to apply the various stages of the writing process.

The first hurdle with this type of task is to find a focus that interests you. Don’t just pick something you feel will be “easy to write about” or that you think you already know a lot about —those almost always turn out to be false assumptions. Instead, you’ll get the most value out of, and find it easier to work on, a topic that intrigues you personally or a topic about which you have a genuine curiosity.

The same getting-started ideas described for defined-topic assignments will help with these kinds of projects, too. You can also try talking with your instructor or a writing tutor (at your college’s writing center) to help brainstorm ideas and make sure you’re on track.

Getting Started in the Writing Process

Writing is not a linear process, so writing your essay, researching, rewriting, and adjusting are all part of the process. Below are some tips to keep in mind as you approach and manage your assignment.

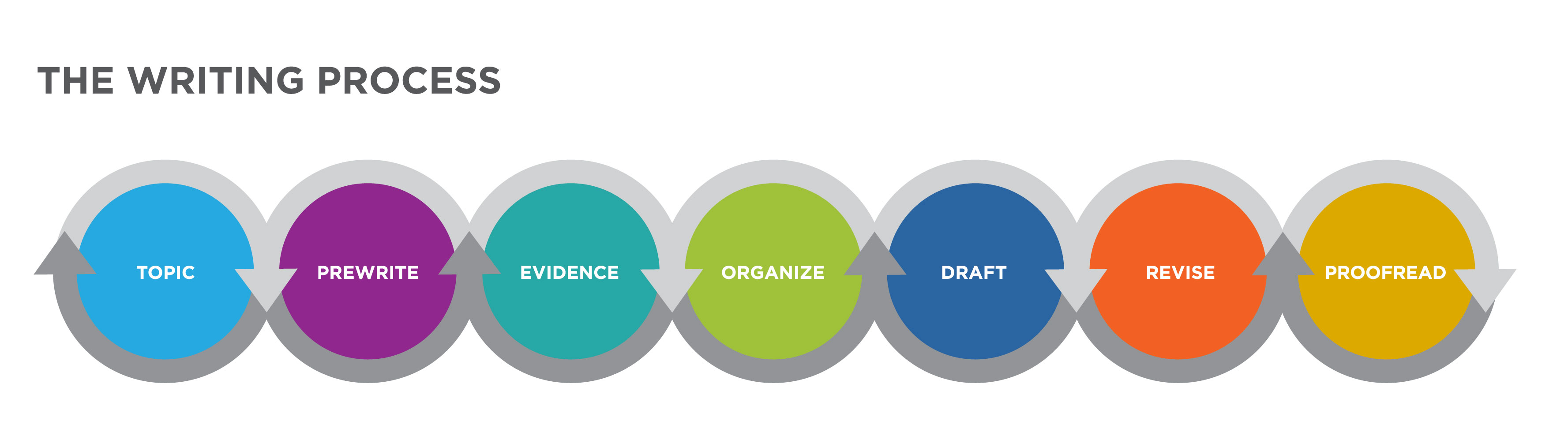

Figure 4 . Writing is a recursive process that begins with examining the topic and prewriting.

Write down topic ideas. If you have been assigned a particular topic or focus, it still might be possible to narrow it down or personalize it to your own interests.

If you have been given an open-ended essay assignment, the topic should be something that allows you to enjoy working with the writing process. Select a topic that you’ll want to think about, read about, and write about for several weeks, without getting bored.

Figure 5 . Just getting started is sometimes the most difficult part of writing. Freewriting and planning to write multiple drafts can help you dive in.

If you’re writing about a subject you’re not an expert on and want to make sure you are presenting the topic or information realistically, look up the information or seek out an expert to ask questions.

- Note: Be cautious about information you retrieve online, especially if you are writing a research paper or an article that relies on factual information. A quick Google search may turn up unreliable, misleading sources. Be sure you consider the credibility of the sources you consult (we’ll talk more about that later in the course). And keep in mind that published books and works found in scholarly journals have to undergo a thorough vetting process before they reach publication and are therefore safer to use as sources.

- Check out a library. Yes, believe it or not, there is still information to be found in a library that hasn’t made its way to the Web. For an even greater breadth of resources, try a college or university library. Even better, research librarians can often be consulted in person, by phone, or even by email. And they love helping students. Don’t be afraid to reach out with questions!

Write a Rough Draft

It doesn’t matter how many spelling errors or weak adjectives you have in it. Your draft can be very rough! Jot down those random uncategorized thoughts. Write down anything you think of that you want included in your writing and worry about organizing and polishing everything later.

If You’re Having Trouble, Try F reewriting

Set a timer and write continuously until that time is up. Don’t worry about what you write, just keeping moving your pencil on the page or typing something (anything!) into the computer.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Outcome: Writing in College. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence. Authored by : Amy Guptill. Provided by : SUNY Open Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of man writing. Authored by : Matt Zhang. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/pAg6t9 . License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- Writing Strategies. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lumencollegesuccess/chapter/writing-strategies/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of woman reading. Authored by : Aaron Osborne. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/dPLmVV . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of sketches of magnifying glass. Authored by : Matt Cornock. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/eBSLmg . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- How to Write a Summary. Authored by : WikiHow. Located at : http://www.wikihow.com/Write-a-Summary . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- How to Write. Provided by : WikiHow. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of typing. Authored by : Kiran Foster. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/9M2WW4 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

ASSIGNED in a Sentence Examples: 21 Ways to Use Assigned

Have you ever been assigned a writing task and felt unsure how to start? When a task is assigned to you, it means you have been given a specific job or responsibility to complete within a set timeframe. This could be anything from a school assignment to a work project.

Being assigned a task often requires understanding the instructions clearly, planning out what needs to be done, and then taking action to complete the task properly. It’s important to pay attention to any guidelines or requirements provided when a task is assigned to ensure you meet expectations.

Table of Contents

7 Examples Of Assigned Used In a Sentence For Kids

- The teacher assigned everyone a different color for art class.

- We were assigned a new book to read for our English lesson.

- Each student was assigned a number for the class attendance.

- The math homework assigned by the teacher was to practice counting.

- The class was assigned the task of drawing their favorite animal.

- The students were assigned different roles for the school play.

- Our teacher assigned us a project to learn about different animals.

14 Sentences with Assigned Examples

- Assigned readings are crucial to understanding the course material in college.

- Make sure to submit your assigned essays on time.

- It is important to attend all assigned lectures to grasp the concepts well.

- Have you received your assigned group project topic yet?

- Remember to prepare for the assigned quiz next week.

- The teacher has assigned extra practice problems to help improve our understanding.

- Did you finish the assigned lab exercises for the week?

- It is essential to take notes during assigned seminars for better revision.

- Make sure to review all assigned chapters before the exam.

- The professor has assigned a research paper as part of the final assessment.

- Don’t forget about the assigned presentation scheduled for next Monday.

- Have you completed the assigned online module on the college portal?

- The assigned group project requires collaboration with classmates.

- The teacher assigned a peer review activity to provide feedback on each other’s work.

How To Use Assigned in Sentences?

To use assigned in a sentence, you need to understand its meaning first. The word assigned is commonly used to indicate that someone has been given a specific task, role, or duty.

Here is an example sentence using assigned : “The teacher assigned homework to the students to complete over the weekend.”

When using assigned in a sentence, it is important to remember that it is often followed by what has been given or designated to someone. For example, “The manager assigned the new project to the most experienced team member.”

Another important point to remember when using assigned is to ensure that the sentence structure is correct. You can place the word assigned at different points in a sentence depending on the emphasis you want to give to it. For instance, “The detective was assigned to investigate the case” puts the focus on who is given the task, while “The case was assigned to the detective to investigate” emphasizes what was given.

Overall, using assigned in a sentence is straightforward once you understand its meaning and how to structure your sentence effectively. Just remember to indicate who is being given the task and what task has been given, and you will be able to use assigned accurately in your sentences.

In conclusion, the concept of assigned sentences refers to specific tasks or responsibilities that are allocated to individuals. These sentences can range from work assignments to punishment in legal contexts, each carrying a defined purpose and outcome. The effectiveness of assigned sentences lies in their ability to streamline processes, hold individuals accountable, and facilitate clear communication of expectations.

Whether in work settings, educational institutions, or legal systems, the use of assigned sentences helps in organizing tasks, maintaining order, and ensuring fairness. By clearly defining roles and responsibilities through assigned sentences, individuals can better understand their obligations and contribute to efficient and structured environments. Overall, assigned sentences play a crucial role in enhancing productivity, accountability, and the overall functioning of various systems and organizations.

Related Posts

In Front or Infront: Which Is the Correct Spelling?

As an expert blogger with years of experience, I’ve delved… Read More » In Front or Infront: Which Is the Correct Spelling?

Targeted vs. Targetted: Correct Spelling Explained in English (US) Usage

Are you unsure about whether to use “targetted” or “targeted”?… Read More » Targeted vs. Targetted: Correct Spelling Explained in English (US) Usage

As per Request or As per Requested: Understanding the Correct Usage

Having worked in various office environments, I’ve often pondered the… Read More » As per Request or As per Requested: Understanding the Correct Usage

James and Jennifer Crumbley, parents of Michigan shooter, sentenced to 10 to 15 years in prison

Jennifer and James Crumbley, the first parents of a mass school shooter in the U.S. to be convicted of involuntary manslaughter for the attack, were sentenced Tuesday in a Michigan courtroom to 10 to 15 years in prison.

The sentence came after the court heard statements from the family members of Tate Myre, 16, Hana St. Juliana, 14, Madisyn Baldwin, 17, and Justin Shilling, 17 . The students were killed when the Crumbleys' son, Ethan, went on a shooting rampage at Oxford High School in Michigan on Nov. 30, 2021.

"You created all of this," Nicole Beausoleil, Baldwin's mother, said through tears. "You failed as parents. The punishment that you face will never be enough."

Beausoleil recalled the final hours of her daughter's life, comparing them with the Crumbleys' actions before and during the shooting. "When you texted 'Ethan don't do it,' I was texting Madisyn: 'I love you. Please call Mom,'" she said.

Reina St. Juliana, the sister of Hana, brought many to tears as she spoke of how her sister would never see her prom, graduation or birthdays.

"I never got to say goodbye," Reina said. "Hana was only 14 ... she took her last breath in a school she hadn't even been in for three months."

Jill Soave, mother of Justin Shilling, asked the judge to hand down the maximum sentence possible to both parents. "The ripple effects of both James' and Jennifer's failures to act have devastated us all," she said. "This tragedy was completely preventable."

Judge Cheryl Matthews addressed both parents before handing down the sentence, "Mr. Crumbley, it's clear to this court that because of you, there was unfettered access to a gun or guns, as well as ammunition in your home.

"Mrs. Crumbley, you glorified the use and possession of these weapons," she added.

Both parents will credited for time already spent in jail.

Matthews also barred the pair or their "agents" from any contact with the families of the four students. She said she would also rule on the parents' rights to contact their son.

Jennifer and James Crumbley also addressed the court ahead of their sentence.

"The dragging this has had on my heart and soul cannot be expressed in words, just as I know this is not going to ease the pain and suffering of the victims and their families," Jennifer Crumbley said.

Jennifer Crumbley used her statement to clarify her trial testimony when she said she would not have done anything differently leading up to the shooting. It was "completely misunderstood," she said Tuesday, adding that her son had seemed "so normal" and that she could not have foreseen the attack.

She said prosecutors tried to paint her and her husband as parents "so horrible, only a school or mass shooter could be bred from."

"We were good parents. We were the average family. We weren't perfect, but we loved our son and each other tremendously," Jennifer Crumbley said.

James Crumbley apologized to the families during his statement.

"I cannot express how much I wish I had known what was going on with him and what was going to happen, because I absolutely would have done a lot of things differently," he said.

Prosecutors asked that each parent be given 10 to 15 years in prison after separate juries found them each guilty of four counts of involuntary manslaughter earlier this year. Their son, 15 at the time of the shooting, is serving a life sentence for the murders.

The parents have shown no remorse for their actions, prosecutors told Matthews in a sentencing memo . They told the juries that the Crumbleys bought their son the gun he used and ignored troubling signs about his mental health.

Legal experts have said the case, which drew national attention, could influence how society views parents' culpability when their children access guns and cause harm with them. Whether the outcome encourages prosecutors to bring charges against parents going forward remains to be seen.

Why were the Crumbleys culpable in their son's crimes?

The Crumbleys' son went on a rampage in the halls of Oxford High School hours after his parents were called to the school by counselors to discuss concerns over disturbing drawings he had done on a math assignment. Prosecutors said the parents didn't tell school officials their son had access to guns in the home and left him at school that day.

James Crumbley purchased the gun used in the shooting, and in a post on social media Jennifer Crumbley said it was a Christmas present for the boy. The prosecution said the parents could have prevented the shooting if they had taken ordinary care to secure the gun and taken action when it was clear their son was having severe mental health struggles.

The prosecution cited messages the teen sent months before the shooting to his mother that said he saw a "demon" in their house and that clothes were flying around. He also texted a friend that he had "paranoia" and was hearing voices. In a journal, he wrote: "I have zero HELP for my mental problems and it's causing me to shoot up" the school.

The Crumbleys also tried to flee law enforcement when it became clear they would face charges, prosecutors said.

Defense attorneys said the parents never foresaw their son's actions. Jennifer Crumbley portrayed herself as an attentive mother when she took the stand in her own defense, and James Crumbley's lawyer said that the gun didn't really belong to the son, that the father properly secured the gun and that he didn't allow his son to use it unsupervised. In an interview with the Detroit Free Press, part of the USA TODAY Network, the jury foreman in James Crumbley's trial said storage of the gun was the key testimony that drove him to convict.

Parents asked for house arrest, time served

James Crumbley has asked to be sentenced to time already served since his arrest in December 2021, according to the prosecutors' sentencing memo. Jennifer Crumbley hoped to serve out a sentence on house arrest while living in her lawyer's guest house.

Prosecutors rejected the requests in the memo to the judge, saying neither had shown remorse for their roles in the deaths of the four children. James Crumbley also was accused of threatening Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald in a jail phone conversation, Keast said, showing his "chilling lack of remorse."

"Such a proposed sentence is a slap in the face to the severity of tragedy caused by (Jennifer Crumbley's) gross negligence, the victims and their families," Assistant Oakland County Prosecutor Marc Keast wrote of the mother's request in a sentencing memo.

Each involuntary manslaughter count carries up to 15 years in prison, though typically such sentences are handed down concurrently, not consecutively. The judge also has the discretion to go above or below the state advisory guidelines, which recommended a sentencing range of 43 to 86 months − or a maximum of about seven years. The state guideline is advisory, based on post-conviction interviews and facts of the case.

Defiant Crumbleys head to prison — 'Not once did they say ... they're not the victims'

In the end, their defiance did them in.

James and Jennifer Crumbley, the embattled parents of the Oxford school shooter who never publicly accepted accountability for their roles in the 2021 massacre, were both sentenced Tuesday to 10-15 years in prison for the deadly rampage that two juries and a judge concluded could have been prevented had the parents made different choices.

While both parents expressed remorse to the families for the loss of their children at the hands of the Crumbleys' son, the prosecutor and the victims' families argued that the Crumbleys did not do one crucial thing: admit they made a mistake.

“Not once did they say, ‘I wished I would have locked the gun up’ and acknowledge that they’re not the victims in this,” Steve St. Juliana, whose 14-year-old daughter Hana died in the shooting, said after a nearly three-hour sentencing hearing that included tears, heartache, anger and frustration.

The judge appeared exasperated as she schooled the Crumbleys on parenting and rejected all their requests for leniency before handing down her sentence. Each parent was convicted of four counts of involuntary manslaughter for failing to stop what two juries decided was a foreseeable consequence of their son's disturbing conduct. Ethan Crumbley, then 15, murdered four classmates and wounded seven other people at Oxford High School on Nov. 30, 2021. His father bought the murder weapon four days earlier as an early Christmas gift for the teen.

Those killed were Tate Myre, 16; Hana St. Juliana, 14; Madisyn Baldwin, 17, and Justin Shilling, 17.

"Parenting is a complex job," Oakland County Circuit Judge Cheryl Matthews said from the bench. "Parents are not expected to be psychic, but these convictions are not about poor parenting. These convictions confirm repeated acts or lack of acts that could have halted an oncoming runaway train, about repeatedly ignoring things that would make a reasonable person feel their hair on the back of their neck stand up."

The judge continued:

"Opportunity knocked over and over again, louder and louder, and was ignored. No one answered. And these two people should have, and sure didn’t," Matthews said.

At both trials, prosecutors argued the Crumbleys ignored a troubled son who was in distress and spiraling downward, but instead of getting him help, they bought him a gun.

'You glorified the use and possession of these weapons'

"Mr. Crumbley … Because of you there was unfettered access to a gun or guns as well as ammunition in your home. You characterized yourself as a martyr and threatened the well-being of the prosecutor," Matthews said, referring to comments that Crumbley made toward Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald in multiple jailhouse phone calls with a relative.

Matthews then turned her attention to the mother."Mrs. Crumbley, you glorified the use and possession of these weapons. Your attitude toward your son and his behaviors was dispassionate and apathetic .... your response to school staff after a 12-minute meeting was, 'Are we done here?' "

Matthews was referring to the pivotal meeting on the morning of the school shooting, when the Crumbleys were summoned to the counselor's office over a violent drawing their son had made of a gun, a human body bleeding, and the words, "The Thoughts won't stop. Help me." The meeting ended with the Crumbleys returning to their jobs and promising to get their son help within 48 hours. School officials concluded the boy was not a threat to himself or anyone else and let him return to class.

Two hours later, he fired his first shot.

James and Jennifer Crumbley are the first parents in America to be held criminally responsible for a school shooting by their child. Their son Ethan pleaded guilty to his crimes and is serving life in prison without parole.

After the parents' sentencing, Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald, who early on said this would be a challenging prosecution but that the facts of this rare case warranted charges, stressed that her office is not done trying to prevent gun violence in Oakland County.

“Don’t look away," she said. "These were tragic and awful deaths, what these families have gone through. And it is preventable. It is preventable — that is my message.”

It's a message she also hammered away at during both trials — and at the sentencing hearing.

"Help me. Blood everywhere. The world is dead," she said, referring to the shooter's writings on his math worksheet on the day of the shooting.

'They come here today and act like they're victims'

The Crumbleys saw those words, she said, and did nothing.

In pushing for a stiff sentence, McDonald argued there has been "no remorse or accountability" by the Crumbleys.

"Remorse does not sound like, ‘I feel really bad.’ … I’m sure they do," McDonald said, but added that's not the kind of remorse and accountability that the victims are looking for.

"What that looks like is, 'We messed up. We should have done this and we didn’t, and we are very sorry' … and that has not happened."

Yet, she said, "They come here today and act like they're victims."

At the parents' sentencing hearing, the victims' families urged the judge to give the Crumbleys the maximum punishment of 15 years, significantly higher than the state's recommendation of 43-86 months.

'You took four beautiful children from this world'

Nicole Beausoleil, the mother of Madisyn Baldwin, was the first to speak, lambasting the Crumbleys over their parenting decisions and their behaviors since the shooting.

"The lack of compassion you have shown is disgusting … shaking your head during a verdict," as James Crumbley did, is the worst sign of disrespect "I have ever witnessed," Beausoleil said, blaming the parents for the loss of her beautiful daughter and the never-ending pain.

"You created all of this. You created your son's life. … You don't get to look away. … You failed as parents. The punishment that you face will never be enough," she said.

Step by step, the grieving mother took the Crumbleys through the countless painful days she has endured: the day she frantically searched for her daughter in the Meijer parking lot after the shooting, how she collapsed and couldn't talk after learning the girl had died, how she had to listen to her other daughter cry for nights on end over her sister's loss.

"From the moment she was born, I promised myself I would be there no matter what … I wouldn't miss a thing I would always protect her."

Then came the shooting.

" Nov. 30, 2021 … made me break my first promise. As her mom, I didn't protect her."

She also asked the shooter's mom to consider the following:

"While your son was hearing voices and asking for help, I was helping Madisyn pick out classes.

"When you were called to the school over his troubling drawing, I was planning an oil change for my daughter.

"When you were on the phone … trying to figure out where the gun was … I was on the phone with her father trying to figure out where she was.

"When you texted 'Ethan don't do it,' I was texting Madysin 'I love you. Please call Mom.

"When you found out about the lives lost that day, I was still waiting for my daughter in the parking lot.

"When you got a chance to speak with your son … When you asked him 'why' … I was waiting for the last bus that never came.

"While you were hiding, I was planning her funeral.

"I was forced to do the worst possible thing a parent could do. I was forced to say goodbye to my Madisyn."

Hana St. Juliana's sister: Instead of quality time, 'you gave him a gun'

Reina St. Juliana brought many in the courtroom to tears as she talked about losing her 14-year-old sister, Hana —how her little sister, best friend and better half would never see prom, graduation or even her 15th, 16th or 17th birthdays.

"I never got to say goodbye," Reina said. "Hana was only 14 … she took her last breath in a school she hadn't even been in for three months."

She looked at the Crumbleys and said: "The fact is, you did fail as a parent, Jennifer. Both of you … Instead of giving quality time … you gave him a gun."

"Your mistakes created our everlasting nightmare."

Steve St. Juliana, Hana's father, also lashed out at the Crumbleys.

“They chose to stay quiet, they chose to ignore the warning signs,” he said. “They continue to choose to blame everyone but themselves.”

The impact on him has been devastating, he said.

“Hana’s murder has destroyed a large portion of my soul," the father said. "… I remain a shell of the person I used to be.”

Justin Shilling's mother: 'If only they had taken him home'

Jill Soave, Justin Shilling’s mother, said her “trauma and devastation is hard to put into words.” She described Justin's achievements in school and said their family would have been celebrating his 20th birthday soon.

Instead, she is in court.

“The ripple effects of both James’ and Jennifer’s failures to act have devastated us all,” she said. “If only, your honor, they had taken their son to get counseling instead of buying a gun. … If only they had checked his backpack, if only they had taken him home or taken him to counseling instead of abandoning him at that school, I wouldn’t be standing here today.”

Justin's father also pleaded for justice, saying: “This is not normal. Living a life like this is not normal.”

“I just can’t get over the fact that this tragedy was completely avoidable,” Craig Shilling said. “They failed across the board … this type of blatant disregard is unacceptable.”

Tate Myre's father: 'It's time to learn from this'

Buck Myre, the father of Tate Myre, focused mostly on what believes should happen after the Crumbleys' sentencing.

“This is the low-hanging fruit,” Myre said. “Now it’s time to turn our focus to Oxford Schools, who played a role in this tragedy.”

He said he wants the government to investigate the shooting, the purchase of the gun and the response to the massacre.

“That’s when real change happens," Myre said. "When we look at something, evaluate it and apply lessons learned.”

No school officials have been charged in the shooting. Multiple civil suits have been filed against the school and various officials, alleging, among other things, that they put students in harm's way. But the lawsuits are on appeal as judges have held that the school is covered by governmental immunity.

Crumbleys address families and judge

James and Jennifer Crumbley also spoke at the hearing, and asked the judge to consider giving them time served for their sentences. Each parent has been jailed on $500,000 bond for almost 2½ years. The Crumbleys have long argued that they never saw any signs that their son would hurt himself or anyone else, or that he was mentally ill, and did not know of his plans to shoot up his school. They also maintain the gun at issue was not really a gift that their son could freely use, but was hidden in their bedroom armoire, unloaded in a gun case, and that the bullets were stored in a separate drawer.

James Crumbley appeared to be close to tears as he apologized to the families who lost their children.

“My heart is really broken for everyone involved,” he said. “ I understand my words are not going to bring any comfort. I understand that they are not going to relieve any pain, and quite frankly, they probably just don’t believe me," Crumbley said. "However, I really want the families of Madisyn Baldwin, Hana St. Juliana, Tate Myre and Justin Shilling to know how truly sorry I am and how devastated I was when I heard what happened to them."

"I have cried for you and the loss of your children more times than I can count."

The father said that if he’d known what was happening with his son, he would have done things differently, while his attorney said he could not have predicted what could have happened.

Crumbley also echoed Buck Myre's call for more transparency and investigation into the school district and officials’ actions surrounding the shooting.

“It is time that we all know the truth. We have been prohibited from telling the whole truth, the whole truth has not been told. I’m with you Mr. Myre, I want the whole truth,” Crumbley said.

As he spoke, some of the victims' families shook their heads.

Madisyn's mom didn't buy it, and said James Crumbley’s mentioning of holding the school accountable was another attempt to play the victim.

“If he wanted the truth," Beausoleil said after sentencing, "he would have been speaking the truth the whole time and had remorse the whole time.”

Craig Shilling echoed that, saying: “The fact that they didn’t show that level of remorse until the end — that half-baked attempt anyway — was too little too late.”

Jennifer Crumbley also addressed the victims' families, saying she has spent "countless nights" lamenting, praying for forgiveness — she told the prosecution "I have hated you" — and praying that "all the victims are in God's mercy and peace."

"I sit here today to express my deepest sorrows to the victims' families," Jennifer Crumbley said, adding that the "gravity and weight that this has taken on my heart and soul" can never be measured and "nothing I can say will ease" the pain and heartache suffered by the victims' families.

'My husband and I used to say we had a perfect kid'

She also addressed her controversial testimony, during which she said, "I wouldn't have done anything differently." The comment was cited by the jury foreperson in her case and by Oxford High families as callous and showing her lack of remorse.

"I was horrified to learn that my answer had the effect" that it did, she said, explaining that her answer reflected what she knew at the time.

"This was not something I foresaw," Jennifer Crumbley said of the shooting. "With the benefit of hindsight, my answer would be drastically different."

Especially, she added, "if I thought my son was capable of crimes like these."

"The Ethan I knew was a good kid. My husband and I used to say we had a perfect kid … that's who I saw and thought I knew," she said.

Jennifer Crumbley also laid blame on the school, saying it failed to alert her about her son's troubling behavior on several occasions, and when it did summon her over a troubling drawing, "We were led to believe from school officials and Ethan as well that this was an isolated event," she said. "We were never asked to take him home that day."

Jennifer Crumbley suggested that what happened to her and her husband could happen to any parent, attempting to refute the idea that she and James Crumbley were bad parents or missed warning signs.

“We were good parents,” she said. “We were the average family. Everything we strived for was to make sure our son had the best life we could give him. I know we did our best.”

She also urged the public to take away this message: "This could be any parent … your child can make any decision."

Not just with a gun, she said, but with a knife, a vehicle — and the parents could be held responsible.

But she has come to forgive the prosecutors over time, she said, and continues to try to forgive herself for decisions she cannot change.

"To the victims and the families, I stand today not to ask for your forgiveness, but to express my sincere apologies for the pain that has been caused."

"Alone, I grieve … I will be in my own internal prison for the rest of my life."

Contact Tresa Baldas: [email protected]

Parents of Michigan school shooter Ethan Crumbley both sentenced to 10-15 years for involuntary manslaughter

PONTIAC, Mich. — The first parents to ever be charged , then convicted, in their child’s mass shooting at a U.S. school were both sentenced Tuesday to 10 to 15 years in prison after they faced the victims' families at a sentencing hearing in a Michigan courtroom.

James Crumbley, 47, and his wife, Jennifer, 46, were sentenced one after another by Circuit Court Judge Cheryl Matthews as they appeared together for the first time since they attended joint hearings before their landmark trials were separated last fall. Their son, Ethan, now 17, pleaded guilty as an adult to the 2021 shooting at Oxford High School in suburban Detroit and was sentenced to life in prison.

Matthews' sentencing decision was in line with what Oakland County prosecutors had asked for after both parents were found guilty on four counts of involuntary manslaughter, one for each of the students their son killed.

Matthews told the Crumbleys that the jury convictions were "not about poor parenting" but about how they repeatedly ignored warning signs that a "reasonable person" would have seen.

"These convictions confirm repeated acts that could have halted an oncoming runaway train," she said.

The couple will get credit for time served in an Oakland County jail since their arrests in the wake of the shooting on Nov. 30, 2021. The pair sat apart at the defense table with their lawyers beside them as the families of the four students who were killed asked before sentencing for the maximum terms to be imposed.

"When you texted, 'Ethan don't do it,' I was texting, 'Madisyn I love you, please call mom,'" Nicole Beausoleil, the mother of shooting victim Madisyn Baldwin, 17, told the Crumbleys. "When you found out about the lives your son took that day, I was still waiting for my daughter in the parking lot.

"The lack of compassion you've shown is outright disgusting," she added through tears.

Jill Soave, the mother of another slain student, Justin Shilling, 17, said the parents' inaction on the day of the shooting "failed their son and failed us all."

Justin's father, Craig Shilling, said he was troubled by Jennifer Crumbley's testimony during her trial in which she said she would not have done anything differently, even today.

"The blood of our children is on your hands, too," Craig Shilling said.

James Crumbley wore an orange jumpsuit and headphones to help with his hearing, and Jennifer Crumbley wore a gray-and-white jumpsuit. He did not look at his wife, while she glanced in his direction.

In Michigan, prosecutors said, felonies that rise out of the same event must run concurrently, so the most Matthews could have imposed is 15 years in total. And while prosecutors wanted the parents to receive sentences that exceeded the advisory guideline range, Matthews had the ultimate discretion, weighing factors such as past criminal behavior and the circumstances of their crimes.

Before she was sentenced, Jennifer Crumbley told the court that she felt "deep remorse, regret and grief" about the shooting, but she also deflected some of the blame onto school officials and took offense to the prosecution's strategy portraying her as a neglectful mother .

"We were good parents," Crumbley said. "We were the average family. We weren't perfect, but we loved our son and each other tremendously."

James Crumbley also addressed the court, explaining to the judge that he did not know beforehand about his son's planned attack on his school and telling the victims' families directly that he would have acted differently on the day of the shooting.

"Please note that I am truly sorry for your loss as a result of what my son did," he said. "I cannot express how much I wish I had known what was going on with him or what was going to happen."

Matthews said during Tuesday's sentencing that the family would not be housed together and that the state Corrections Department has indicated James and Ethan Crumbley specifically will not be in the same facility given their relationship. Ethan is being held in a state prison 17 miles from Oxford High School. Jennifer Crumbley would be sent to the state's only women's prison.

James and Jennifer Crumbley have not been able to communicate as part of a no contact order since their arrests.

In both parents' cases, prosecutors wrote that their "gross negligence changed an entire community forever."

They both could have prevented the shooting with "tragically simple actions," prosecutors wrote, adding that they "failed to take any action when presented with the gravest of dangers."

Legal experts had suggested James Crumbley could have faced a harsher sentence than his wife after prosecutors said he made threats in jail.

During his trial, Matthews restricted his communication to only his lawyer and clergy.

The sentencing memo for James Crumbley referred to allegations that he made threats against the prosecutor and said that "his jail calls show a total lack of remorse" and that "he blames everyone but himself."

The memo details the expletive-ridden threats he is alleged to have directly addressed to the prosecutor on multiple recorded jail calls. In one call before the trial, he said, "Karen McDonald, you're going down," according to prosecutors. In other calls, he threatened retribution, they said.

James Crumbley’s lawyer, Mariell Lehman, wrote in court documents that the calls did not include threats to physically harm the prosecutor but that he expressed his desire to ensure that McDonald is not able to continue practicing law as a result of her actions in the case.

"It is clear Mr. Crumbley is venting to loved ones about his frustrations related to the lack of investigation done by the prosecution prior to authorizing charges," Lehman wrote, saying her client is understandably angry at his situation.

The prosecution's memo also says James Crumbley asserted his innocence in a pre-sentence report, indicating a lack of remorse.

"I feel horrible for what happened and would do anything to be able to go back in time and change it! But I can't. And I had nothing to do with what happened," he wrote, according to the prosecution memo. "I don't know why my son did what he did. HE is the only one who knows."

Lehman has not said whether she plans to appeal James Crumbley's verdict, while a lawyer for Jennifer Crumbley, Shannon Smith, has written that she will.

Two separate trials

James Crumbley did not take the stand during his trial. His wife testified that she placed the responsibility of securing the 9 mm semiautomatic handgun used in the shooting on her husband.

Asked whether she would have done anything differently, Jennifer Crumbley told jurors, "I don't think I'm a failure as a parent."

Prosecutors argued that she knew of her son's deteriorating mental health and social isolation and that he had access to a gun but that she cared more about her hobbies and carrying on an extramarital affair than about being present at home.

Her defense lawyer attempted to portray her as a caring mother, albeit one who did not know her son was capable of such violence — suggesting instead that his school failed to fully inform her of his troubles and that her husband was responsible for the weapon.

Smith continued to defend her client in her sentencing memo.

"Criticizing Mrs. Crumbley for being 'rarely home' is a sexist and misogynistic attack on a mother," Smith wrote.

In a pre-sentence report, Jennifer Crumbley said she has the hindsight now to know she would have handled things differently.

"With the information I have now, of course my answer would be hugely different," she said. "There are so many things that I would change if I could go back in time."

Both her and her husband's trials centered on the day of the shooting.

A day after Thanksgiving, prosecutors said, James Crumbley bought their son the handgun, while Jennifer Crumbley took him to a gun range that weekend.

On Tuesday, a teacher said she had found a note on Ethan's desk with a drawing of a gun and a person who had been shot, along with messages including: "The thoughts won't stop. Help me."

That discovery prompted the school to summon the parents for a meeting, but school officials testified that they declined to bring him home because they had to go back to work.

The officials also said that if the parents had informed them that their son had access to a gun, they would have been more authoritative to ensure immediate safety.

Ethan would go on to commit the school shooting later that afternoon, killing Baldwin; Shilling; Tate Myre, 16; and Hana St. Juliana, 14.

Victims' families want accountability

In the aftermath of the trials, the victims' families have demanded further accountability. They are seeking changes to governmental immunity laws that protect schools from being sued and want to see a requirement for independent reviews after any mass shooting.

Oakland County prosecutors have said they do not plan to charge anyone else in connection with the massacre.

Buck Myre, the father of Tate Myre, said during Tuesday's sentencing that families still want a government-led investigation.

"It's time to drive real change from this tragedy," he told the judge.

Later, James Crumbley stood and addressed Buck Myre directly when he was given the chance to speak.

"It is time that we all know the truth," he said. "I, too, want the truth, because you have not had it."

Selina Guevara and Maggie Vespa reported from Pontiac and Erik Ortiz from New York.

Selina Guevara is an NBC News associate producer, based in Chicago.

NBC News Correspondent

Erik Ortiz is a senior reporter for NBC News Digital focusing on racial injustice and social inequality.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Tenant right is assignable, and will pass under an assignment of "all the estate and interest" of the outgoing tenant in the farm. 19. 8. The assignment system was eventually abandoned in consequence of its moral and economic evils, but it cannot be denied that while it lasted the colony made substantial progress. 21.

In this sense, "assignment" can be both countable and uncountable, depending on the context. For example, one might say: "The teacher gave us an assignment to complete over the weekend.". "I have three assignments due tomorrow.". "She received a challenging assignment at work.".

Examples of assignment in a sentence, how to use it. 98 examples: Apart from that, there is a suspicion that programming without assignments or…

We welcome feedback: report an example sentence to the Collins team. Read more…. I settled for a short hop across the Channel on a work assignment. Times, Sunday Times. ( 2016) His first assignment was to write a program for an insurance broker in Dorset, using assembly code. Times, Sunday Times.

To use the word assignment in a sentence, simply place it in the context of giving or receiving a task. For example, "The teacher handed out the math assignment to the students" or "I have a new assignment at work that I need to complete by Friday.". When using assignment in a sentence, it is important to ensure that it fits naturally ...

assignment (n): a specific task or work that is given someone at work or school. Listen to all | All sentences (with pause) Used with adjectives: " I am giving you a special assignment. "(special, important)" This assignment could be very dangerous. "(dangerous, difficult, tough)" I am busy with a work assignment. "(work, school, job)" I've ...

1. 0. Assign a specific egg color for each team. 1. 0. He brought existential propositions, indeed, within a rational system through the principle that it must be feasible to assign a sufficient reason for them, but he refused to bring them under the conception of identity or necessity, i.e. 0. 0.

The meaning of ASSIGNMENT is the act of assigning something. How to use assignment in a sentence. Synonym Discussion of Assignment.

1 [countable, uncountable] a task or piece of work that someone is given to do, usually as part of their job or studies You will need to complete three written assignments per semester. She is in Greece on an assignment for one of the Sunday newspapers. one of our reporters on assignment in China I had given myself a tough assignment. a business/special assignment

Examples of ASSIGN in a sentence, how to use it. 23 examples: Works that were centrally planned and assigned, moreover, had a better chance…

What this handout is about. The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms ...

How To Use "Assignment" In A Sentence. The word "assignment" refers to a specific project or task that is given to someone to complete. Here are some examples of how to use "assignment" in a sentence: She received an assignment to write a report on the company's finances. He was given the assignment of leading the team on the project.