Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples

Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 5 December 2022.

A correlational research design investigates relationships between variables without the researcher controlling or manipulating any of them.

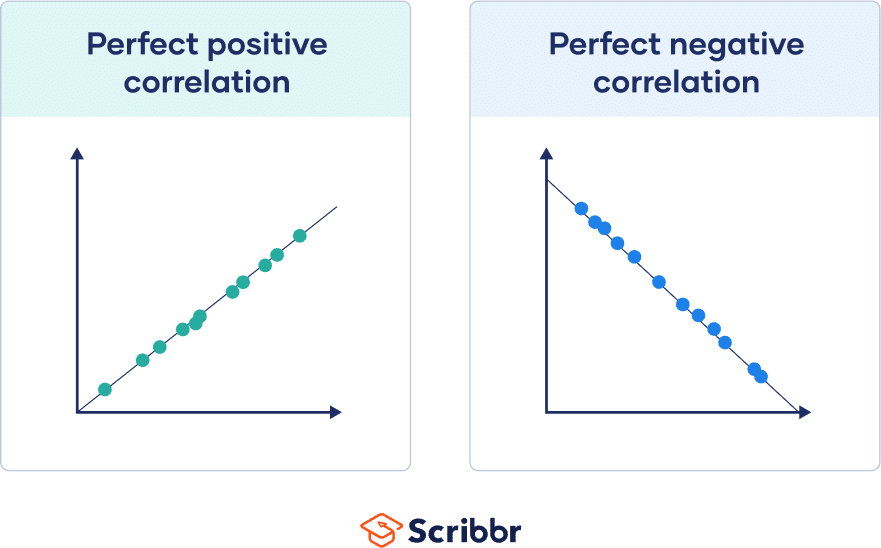

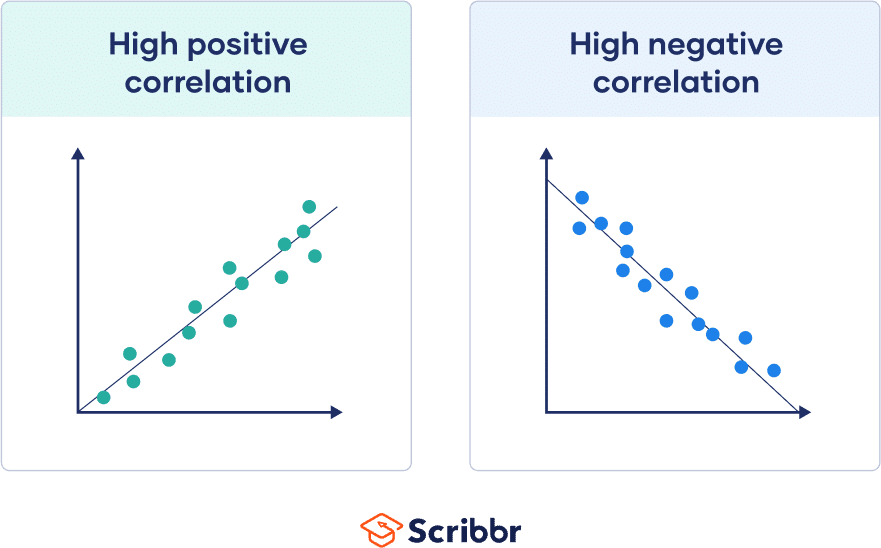

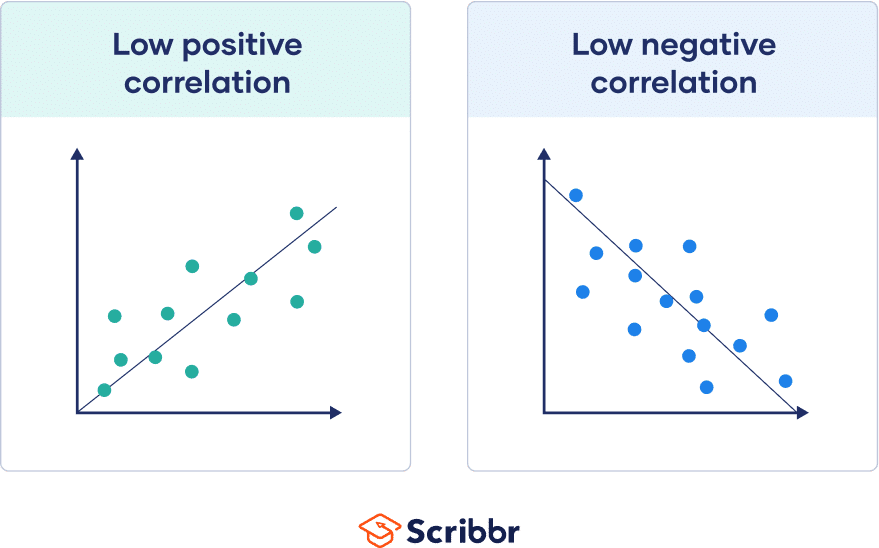

A correlation reflects the strength and/or direction of the relationship between two (or more) variables. The direction of a correlation can be either positive or negative.

Table of contents

Correlational vs experimental research, when to use correlational research, how to collect correlational data, how to analyse correlational data, correlation and causation, frequently asked questions about correlational research.

Correlational and experimental research both use quantitative methods to investigate relationships between variables. But there are important differences in how data is collected and the types of conclusions you can draw.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Correlational research is ideal for gathering data quickly from natural settings. That helps you generalise your findings to real-life situations in an externally valid way.

There are a few situations where correlational research is an appropriate choice.

To investigate non-causal relationships

You want to find out if there is an association between two variables, but you don’t expect to find a causal relationship between them.

Correlational research can provide insights into complex real-world relationships, helping researchers develop theories and make predictions.

To explore causal relationships between variables

You think there is a causal relationship between two variables, but it is impractical, unethical, or too costly to conduct experimental research that manipulates one of the variables.

Correlational research can provide initial indications or additional support for theories about causal relationships.

To test new measurement tools

You have developed a new instrument for measuring your variable, and you need to test its reliability or validity .

Correlational research can be used to assess whether a tool consistently or accurately captures the concept it aims to measure.

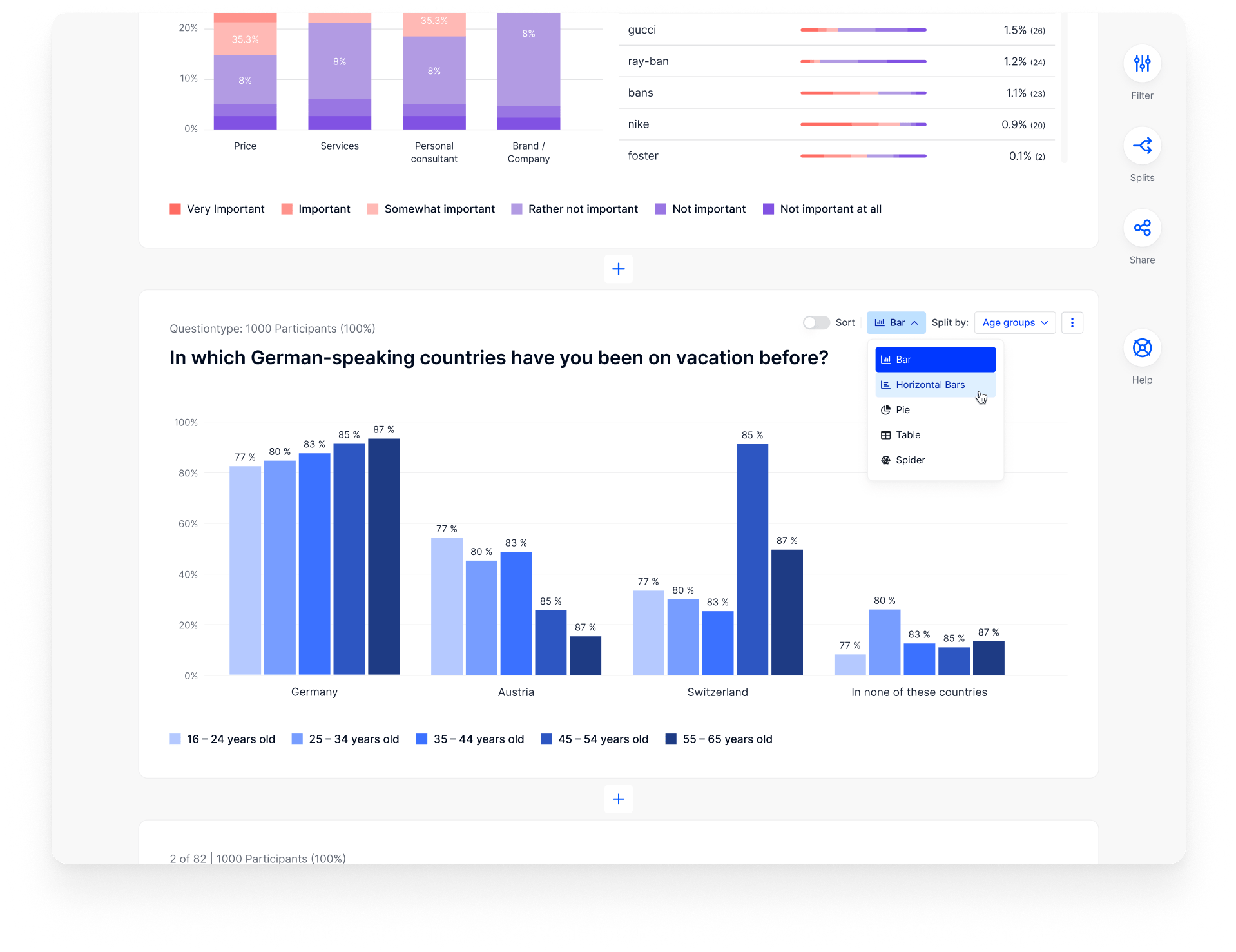

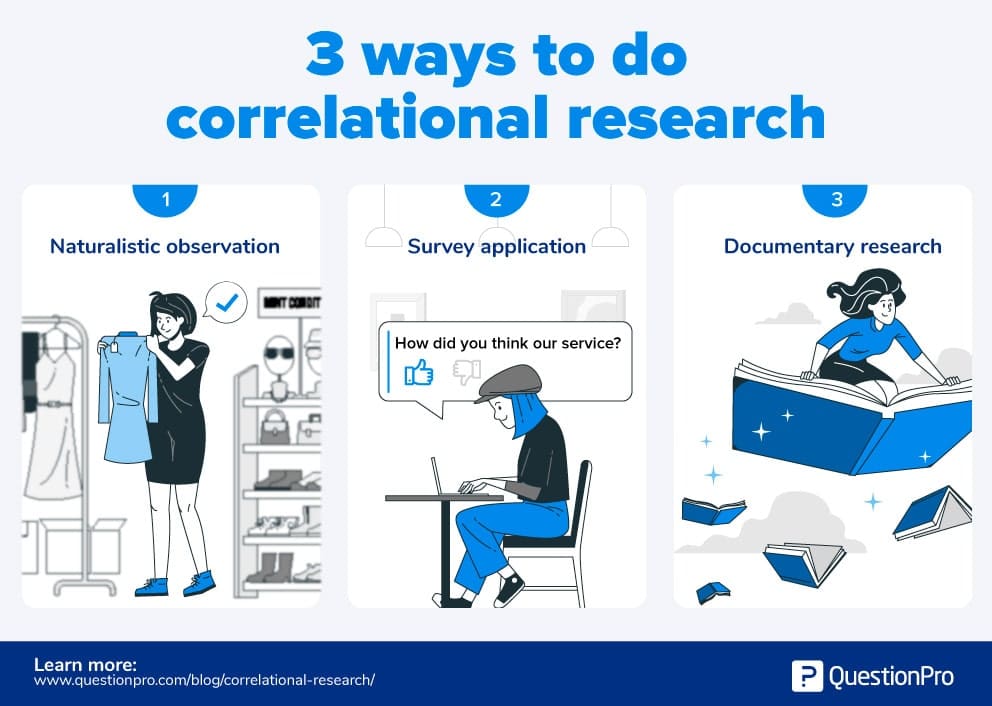

There are many different methods you can use in correlational research. In the social and behavioural sciences, the most common data collection methods for this type of research include surveys, observations, and secondary data.

It’s important to carefully choose and plan your methods to ensure the reliability and validity of your results. You should carefully select a representative sample so that your data reflects the population you’re interested in without bias .

In survey research , you can use questionnaires to measure your variables of interest. You can conduct surveys online, by post, by phone, or in person.

Surveys are a quick, flexible way to collect standardised data from many participants, but it’s important to ensure that your questions are worded in an unbiased way and capture relevant insights.

Naturalistic observation

Naturalistic observation is a type of field research where you gather data about a behaviour or phenomenon in its natural environment.

This method often involves recording, counting, describing, and categorising actions and events. Naturalistic observation can include both qualitative and quantitative elements, but to assess correlation, you collect data that can be analysed quantitatively (e.g., frequencies, durations, scales, and amounts).

Naturalistic observation lets you easily generalise your results to real-world contexts, and you can study experiences that aren’t replicable in lab settings. But data analysis can be time-consuming and unpredictable, and researcher bias may skew the interpretations.

Secondary data

Instead of collecting original data, you can also use data that has already been collected for a different purpose, such as official records, polls, or previous studies.

Using secondary data is inexpensive and fast, because data collection is complete. However, the data may be unreliable, incomplete, or not entirely relevant, and you have no control over the reliability or validity of the data collection procedures.

After collecting data, you can statistically analyse the relationship between variables using correlation or regression analyses, or both. You can also visualise the relationships between variables with a scatterplot.

Different types of correlation coefficients and regression analyses are appropriate for your data based on their levels of measurement and distributions .

Correlation analysis

Using a correlation analysis, you can summarise the relationship between variables into a correlation coefficient : a single number that describes the strength and direction of the relationship between variables. With this number, you’ll quantify the degree of the relationship between variables.

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, also known as Pearson’s r , is commonly used for assessing a linear relationship between two quantitative variables.

Correlation coefficients are usually found for two variables at a time, but you can use a multiple correlation coefficient for three or more variables.

Regression analysis

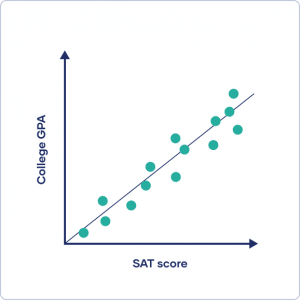

With a regression analysis , you can predict how much a change in one variable will be associated with a change in the other variable. The result is a regression equation that describes the line on a graph of your variables.

You can use this equation to predict the value of one variable based on the given value(s) of the other variable(s). It’s best to perform a regression analysis after testing for a correlation between your variables.

It’s important to remember that correlation does not imply causation . Just because you find a correlation between two things doesn’t mean you can conclude one of them causes the other, for a few reasons.

Directionality problem

If two variables are correlated, it could be because one of them is a cause and the other is an effect. But the correlational research design doesn’t allow you to infer which is which. To err on the side of caution, researchers don’t conclude causality from correlational studies.

Third variable problem

A confounding variable is a third variable that influences other variables to make them seem causally related even though they are not. Instead, there are separate causal links between the confounder and each variable.

In correlational research, there’s limited or no researcher control over extraneous variables . Even if you statistically control for some potential confounders, there may still be other hidden variables that disguise the relationship between your study variables.

Although a correlational study can’t demonstrate causation on its own, it can help you develop a causal hypothesis that’s tested in controlled experiments.

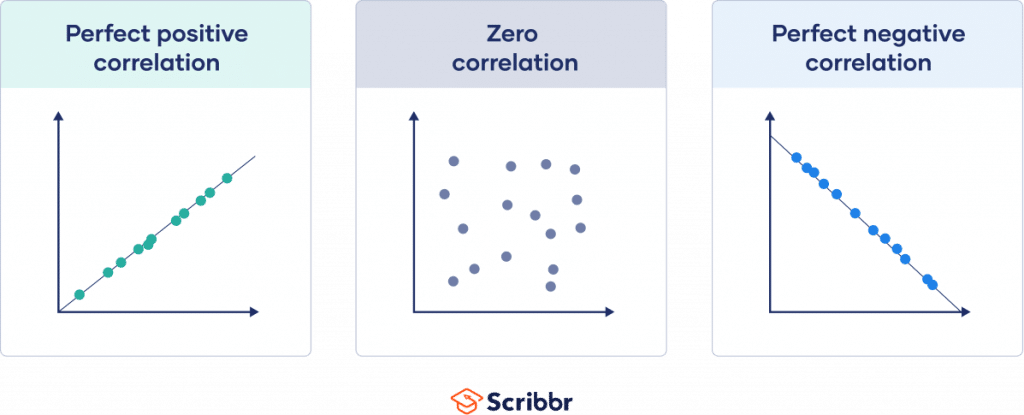

A correlation reflects the strength and/or direction of the association between two or more variables.

- A positive correlation means that both variables change in the same direction.

- A negative correlation means that the variables change in opposite directions.

- A zero correlation means there’s no relationship between the variables.

A correlational research design investigates relationships between two variables (or more) without the researcher controlling or manipulating any of them. It’s a non-experimental type of quantitative research .

Controlled experiments establish causality, whereas correlational studies only show associations between variables.

- In an experimental design , you manipulate an independent variable and measure its effect on a dependent variable. Other variables are controlled so they can’t impact the results.

- In a correlational design , you measure variables without manipulating any of them. You can test whether your variables change together, but you can’t be sure that one variable caused a change in another.

In general, correlational research is high in external validity while experimental research is high in internal validity .

A correlation is usually tested for two variables at a time, but you can test correlations between three or more variables.

A correlation coefficient is a single number that describes the strength and direction of the relationship between your variables.

Different types of correlation coefficients might be appropriate for your data based on their levels of measurement and distributions . The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r ) is commonly used to assess a linear relationship between two quantitative variables.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2022, December 05). Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/correlational-research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, quasi-experimental design | definition, types & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Correlational Research – Methods, Types and Examples

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Correlational Research

Correlational Research is a type of research that examines the statistical relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them. It is a non-experimental research design that seeks to establish the degree of association or correlation between two or more variables.

Types of Correlational Research

There are three types of correlational research:

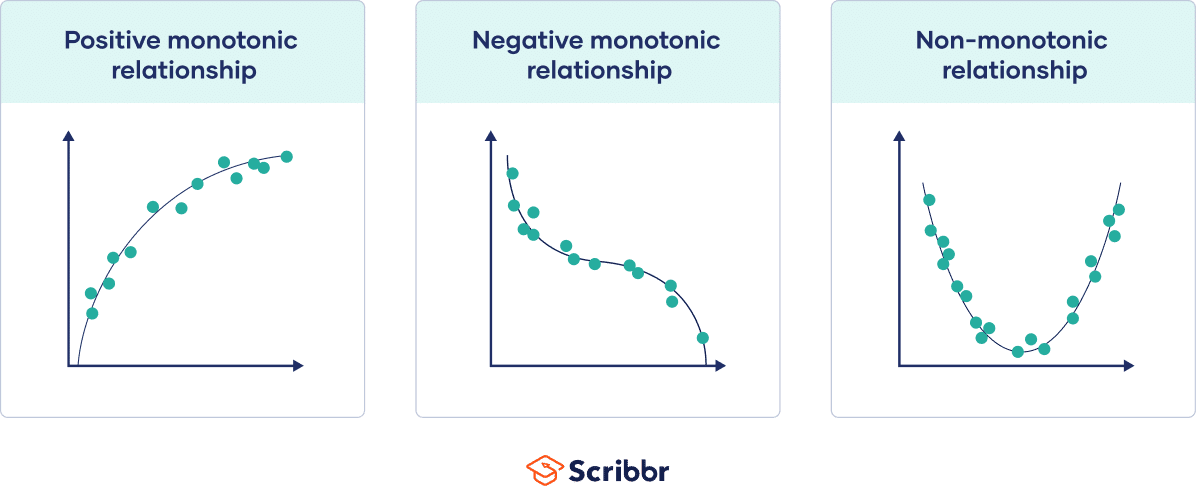

Positive Correlation

A positive correlation occurs when two variables increase or decrease together. This means that as one variable increases, the other variable also tends to increase. Similarly, as one variable decreases, the other variable also tends to decrease. For example, there is a positive correlation between the amount of time spent studying and academic performance. The more time a student spends studying, the higher their academic performance is likely to be. Similarly, there is a positive correlation between a person’s age and their income level. As a person gets older, they tend to earn more money.

Negative Correlation

A negative correlation occurs when one variable increases while the other decreases. This means that as one variable increases, the other variable tends to decrease. Similarly, as one variable decreases, the other variable tends to increase. For example, there is a negative correlation between the number of hours spent watching TV and physical activity level. The more time a person spends watching TV, the less physically active they are likely to be. Similarly, there is a negative correlation between the amount of stress a person experiences and their overall happiness. As stress levels increase, happiness levels tend to decrease.

Zero Correlation

A zero correlation occurs when there is no relationship between two variables. This means that the variables are unrelated and do not affect each other. For example, there is zero correlation between a person’s shoe size and their IQ score. The size of a person’s feet has no relationship to their level of intelligence. Similarly, there is zero correlation between a person’s height and their favorite color. The two variables are unrelated to each other.

Correlational Research Methods

Correlational research can be conducted using different methods, including:

Surveys are a common method used in correlational research. Researchers collect data by asking participants to complete questionnaires or surveys that measure different variables of interest. Surveys are useful for exploring the relationships between variables such as personality traits, attitudes, and behaviors.

Observational Studies

Observational studies involve observing and recording the behavior of participants in natural settings. Researchers can use observational studies to examine the relationships between variables such as social interactions, group dynamics, and communication patterns.

Archival Data

Archival data involves using existing data sources such as historical records, census data, or medical records to explore the relationships between variables. Archival data is useful for investigating the relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled.

Experimental Design

While correlational research does not involve manipulating variables, researchers can use experimental design to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Experimental design involves manipulating one variable while holding other variables constant to determine the effect on the dependent variable.

Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis involves combining and analyzing the results of multiple studies to explore the relationships between variables across different contexts and populations. Meta-analysis is useful for identifying patterns and inconsistencies in the literature and can provide insights into the strength and direction of relationships between variables.

Data Analysis Methods

Correlational research data analysis methods depend on the type of data collected and the research questions being investigated. Here are some common data analysis methods used in correlational research:

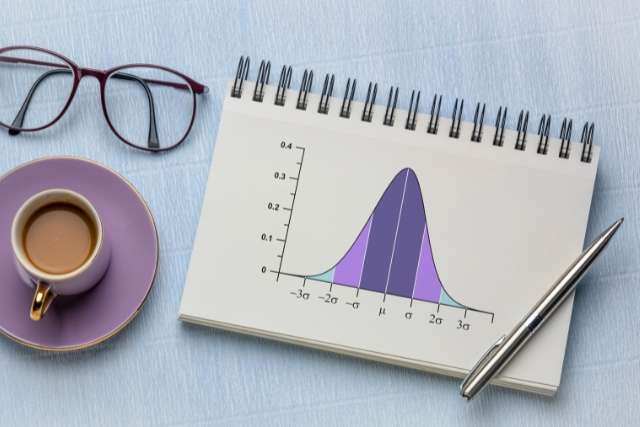

Correlation Coefficient

A correlation coefficient is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. The correlation coefficient ranges from -1 to +1, with -1 indicating a perfect negative correlation, +1 indicating a perfect positive correlation, and 0 indicating no correlation. Researchers use correlation coefficients to determine the degree to which two variables are related.

Scatterplots

A scatterplot is a graphical representation of the relationship between two variables. Each data point on the plot represents a single observation. The x-axis represents one variable, and the y-axis represents the other variable. The pattern of data points on the plot can provide insights into the strength and direction of the relationship between the two variables.

Regression Analysis

Regression analysis is a statistical method used to model the relationship between two or more variables. Researchers use regression analysis to predict the value of one variable based on the value of another variable. Regression analysis can help identify the strength and direction of the relationship between variables, as well as the degree to which one variable can be used to predict the other.

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is a statistical method used to identify patterns among variables. Researchers use factor analysis to group variables into factors that are related to each other. Factor analysis can help identify underlying factors that influence the relationship between two variables.

Path Analysis

Path analysis is a statistical method used to model the relationship between multiple variables. Researchers use path analysis to test causal models and identify direct and indirect effects between variables.

Applications of Correlational Research

Correlational research has many practical applications in various fields, including:

- Psychology : Correlational research is commonly used in psychology to explore the relationships between variables such as personality traits, behaviors, and mental health outcomes. For example, researchers may use correlational research to examine the relationship between anxiety and depression, or the relationship between self-esteem and academic achievement.

- Education : Correlational research is useful in educational research to explore the relationships between variables such as teaching methods, student motivation, and academic performance. For example, researchers may use correlational research to examine the relationship between student engagement and academic success, or the relationship between teacher feedback and student learning outcomes.

- Business : Correlational research can be used in business to explore the relationships between variables such as consumer behavior, marketing strategies, and sales outcomes. For example, marketers may use correlational research to examine the relationship between advertising spending and sales revenue, or the relationship between customer satisfaction and brand loyalty.

- Medicine : Correlational research is useful in medical research to explore the relationships between variables such as risk factors, disease outcomes, and treatment effectiveness. For example, researchers may use correlational research to examine the relationship between smoking and lung cancer, or the relationship between exercise and heart health.

- Social Science : Correlational research is commonly used in social science research to explore the relationships between variables such as socioeconomic status, cultural factors, and social behavior. For example, researchers may use correlational research to examine the relationship between income and voting behavior, or the relationship between cultural values and attitudes towards immigration.

Examples of Correlational Research

- Psychology : Researchers might be interested in exploring the relationship between two variables, such as parental attachment and anxiety levels in young adults. The study could involve measuring levels of attachment and anxiety using established scales or questionnaires, and then analyzing the data to determine if there is a correlation between the two variables. This information could be useful in identifying potential risk factors for anxiety in young adults, and in developing interventions that could help improve attachment and reduce anxiety.

- Education : In a correlational study in education, researchers might investigate the relationship between two variables, such as teacher engagement and student motivation in a classroom setting. The study could involve measuring levels of teacher engagement and student motivation using established scales or questionnaires, and then analyzing the data to determine if there is a correlation between the two variables. This information could be useful in identifying strategies that teachers could use to improve student motivation and engagement in the classroom.

- Business : Researchers might explore the relationship between two variables, such as employee satisfaction and productivity levels in a company. The study could involve measuring levels of employee satisfaction and productivity using established scales or questionnaires, and then analyzing the data to determine if there is a correlation between the two variables. This information could be useful in identifying factors that could help increase productivity and improve job satisfaction among employees.

- Medicine : Researchers might examine the relationship between two variables, such as smoking and the risk of developing lung cancer. The study could involve collecting data on smoking habits and lung cancer diagnoses, and then analyzing the data to determine if there is a correlation between the two variables. This information could be useful in identifying risk factors for lung cancer and in developing interventions that could help reduce smoking rates.

- Sociology : Researchers might investigate the relationship between two variables, such as income levels and political attitudes. The study could involve measuring income levels and political attitudes using established scales or questionnaires, and then analyzing the data to determine if there is a correlation between the two variables. This information could be useful in understanding how socioeconomic factors can influence political beliefs and attitudes.

How to Conduct Correlational Research

Here are the general steps to conduct correlational research:

- Identify the Research Question : Start by identifying the research question that you want to explore. It should involve two or more variables that you want to investigate for a correlation.

- Choose the research method: Decide on the research method that will be most appropriate for your research question. The most common methods for correlational research are surveys, archival research, and naturalistic observation.

- Choose the Sample: Select the participants or data sources that you will use in your study. Your sample should be representative of the population you want to generalize the results to.

- Measure the variables: Choose the measures that will be used to assess the variables of interest. Ensure that the measures are reliable and valid.

- Collect the Data: Collect the data from your sample using the chosen research method. Be sure to maintain ethical standards and obtain informed consent from your participants.

- Analyze the data: Use statistical software to analyze the data and compute the correlation coefficient. This will help you determine the strength and direction of the correlation between the variables.

- Interpret the results: Interpret the results and draw conclusions based on the findings. Consider any limitations or alternative explanations for the results.

- Report the findings: Report the findings of your study in a research report or manuscript. Be sure to include the research question, methods, results, and conclusions.

Purpose of Correlational Research

The purpose of correlational research is to examine the relationship between two or more variables. Correlational research allows researchers to identify whether there is a relationship between variables, and if so, the strength and direction of that relationship. This information can be useful for predicting and explaining behavior, and for identifying potential risk factors or areas for intervention.

Correlational research can be used in a variety of fields, including psychology, education, medicine, business, and sociology. For example, in psychology, correlational research can be used to explore the relationship between personality traits and behavior, or between early life experiences and later mental health outcomes. In education, correlational research can be used to examine the relationship between teaching practices and student achievement. In medicine, correlational research can be used to investigate the relationship between lifestyle factors and disease outcomes.

Overall, the purpose of correlational research is to provide insight into the relationship between variables, which can be used to inform further research, interventions, or policy decisions.

When to use Correlational Research

Here are some situations when correlational research can be particularly useful:

- When experimental research is not possible or ethical: In some situations, it may not be possible or ethical to manipulate variables in an experimental design. In these cases, correlational research can be used to explore the relationship between variables without manipulating them.

- When exploring new areas of research: Correlational research can be useful when exploring new areas of research or when researchers are unsure of the direction of the relationship between variables. Correlational research can help identify potential areas for further investigation.

- When testing theories: Correlational research can be useful for testing theories about the relationship between variables. Researchers can use correlational research to examine the relationship between variables predicted by a theory, and to determine whether the theory is supported by the data.

- When making predictions: Correlational research can be used to make predictions about future behavior or outcomes. For example, if there is a strong positive correlation between education level and income, one could predict that individuals with higher levels of education will have higher incomes.

- When identifying risk factors: Correlational research can be useful for identifying potential risk factors for negative outcomes. For example, a study might find a positive correlation between drug use and depression, indicating that drug use could be a risk factor for depression.

Characteristics of Correlational Research

Here are some common characteristics of correlational research:

- Examines the relationship between two or more variables: Correlational research is designed to examine the relationship between two or more variables. It seeks to determine if there is a relationship between the variables, and if so, the strength and direction of that relationship.

- Non-experimental design: Correlational research is typically non-experimental in design, meaning that the researcher does not manipulate any variables. Instead, the researcher observes and measures the variables as they naturally occur.

- Cannot establish causation : Correlational research cannot establish causation, meaning that it cannot determine whether one variable causes changes in another variable. Instead, it only provides information about the relationship between the variables.

- Uses statistical analysis: Correlational research relies on statistical analysis to determine the strength and direction of the relationship between variables. This may include calculating correlation coefficients, regression analysis, or other statistical tests.

- Observes real-world phenomena : Correlational research is often used to observe real-world phenomena, such as the relationship between education and income or the relationship between stress and physical health.

- Can be conducted in a variety of fields : Correlational research can be conducted in a variety of fields, including psychology, sociology, education, and medicine.

- Can be conducted using different methods: Correlational research can be conducted using a variety of methods, including surveys, observational studies, and archival studies.

Advantages of Correlational Research

There are several advantages of using correlational research in a study:

- Allows for the exploration of relationships: Correlational research allows researchers to explore the relationships between variables in a natural setting without manipulating any variables. This can help identify possible relationships between variables that may not have been previously considered.

- Useful for predicting behavior: Correlational research can be useful for predicting future behavior. If a strong correlation is found between two variables, researchers can use this information to predict how changes in one variable may affect the other.

- Can be conducted in real-world settings: Correlational research can be conducted in real-world settings, which allows for the collection of data that is representative of real-world phenomena.

- Can be less expensive and time-consuming than experimental research: Correlational research is often less expensive and time-consuming than experimental research, as it does not involve manipulating variables or creating controlled conditions.

- Useful in identifying risk factors: Correlational research can be used to identify potential risk factors for negative outcomes. By identifying variables that are correlated with negative outcomes, researchers can develop interventions or policies to reduce the risk of negative outcomes.

- Useful in exploring new areas of research: Correlational research can be useful in exploring new areas of research, particularly when researchers are unsure of the direction of the relationship between variables. By conducting correlational research, researchers can identify potential areas for further investigation.

Limitation of Correlational Research

Correlational research also has several limitations that should be taken into account:

- Cannot establish causation: Correlational research cannot establish causation, meaning that it cannot determine whether one variable causes changes in another variable. This is because it is not possible to control all possible confounding variables that could affect the relationship between the variables being studied.

- Directionality problem: The directionality problem refers to the difficulty of determining which variable is influencing the other. For example, a correlation may exist between happiness and social support, but it is not clear whether social support causes happiness, or whether happy people are more likely to have social support.

- Third variable problem: The third variable problem refers to the possibility that a third variable, not included in the study, is responsible for the observed relationship between the two variables being studied.

- Limited generalizability: Correlational research is often limited in terms of its generalizability to other populations or settings. This is because the sample studied may not be representative of the larger population, or because the variables studied may behave differently in different contexts.

- Relies on self-reported data: Correlational research often relies on self-reported data, which can be subject to social desirability bias or other forms of response bias.

- Limited in explaining complex behaviors: Correlational research is limited in explaining complex behaviors that are influenced by multiple factors, such as personality traits, situational factors, and social context.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

6.2 Correlational Research

Learning objectives.

- Define correlational research and give several examples.

- Explain why a researcher might choose to conduct correlational research rather than experimental research or another type of non-experimental research.

- Interpret the strength and direction of different correlation coefficients.

- Explain why correlation does not imply causation.

What Is Correlational Research?

Correlational research is a type of non-experimental research in which the researcher measures two variables and assesses the statistical relationship (i.e., the correlation) between them with little or no effort to control extraneous variables. There are many reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The first is that they do not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one or are not interested in causal relationships. Recall two goals of science are to describe and to predict and the correlational research strategy allows researchers to achieve both of these goals. Specifically, this strategy can be used to describe the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables and if there is a relationship between the variables then the researchers can use scores on one variable to predict scores on the other (using a statistical technique called regression).

Another reason that researchers would choose to use a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to be causal, but the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical. For example, while I might be interested in the relationship between the frequency people use cannabis and their memory abilities I cannot ethically manipulate the frequency that people use cannabis. As such, I must rely on the correlational research strategy; I must simply measure the frequency that people use cannabis and measure their memory abilities using a standardized test of memory and then determine whether the frequency people use cannabis use is statistically related to memory test performance.

Correlation is also used to establish the reliability and validity of measurements. For example, a researcher might evaluate the validity of a brief extraversion test by administering it to a large group of participants along with a longer extraversion test that has already been shown to be valid. This researcher might then check to see whether participants’ scores on the brief test are strongly correlated with their scores on the longer one. Neither test score is thought to cause the other, so there is no independent variable to manipulate. In fact, the terms independent variable and dependent variabl e do not apply to this kind of research.

Another strength of correlational research is that it is often higher in external validity than experimental research. Recall there is typically a trade-off between internal validity and external validity. As greater controls are added to experiments, internal validity is increased but often at the expense of external validity. In contrast, correlational studies typically have low internal validity because nothing is manipulated or control but they often have high external validity. Since nothing is manipulated or controlled by the experimenter the results are more likely to reflect relationships that exist in the real world.

Finally, extending upon this trade-off between internal and external validity, correlational research can help to provide converging evidence for a theory. If a theory is supported by a true experiment that is high in internal validity as well as by a correlational study that is high in external validity then the researchers can have more confidence in the validity of their theory. As a concrete example, correlational studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behavior have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001) [1] . These converging results provide strong evidence that there is a real relationship (indeed a causal relationship) between watching violent television and aggressive behavior.

Data Collection in Correlational Research

Again, the defining feature of correlational research is that neither variable is manipulated. It does not matter how or where the variables are measured. A researcher could have participants come to a laboratory to complete a computerized backward digit span task and a computerized risky decision-making task and then assess the relationship between participants’ scores on the two tasks. Or a researcher could go to a shopping mall to ask people about their attitudes toward the environment and their shopping habits and then assess the relationship between these two variables. Both of these studies would be correlational because no independent variable is manipulated.

Correlations Between Quantitative Variables

Correlations between quantitative variables are often presented using scatterplots . Figure 6.3 shows some hypothetical data on the relationship between the amount of stress people are under and the number of physical symptoms they have. Each point in the scatterplot represents one person’s score on both variables. For example, the circled point in Figure 6.3 represents a person whose stress score was 10 and who had three physical symptoms. Taking all the points into account, one can see that people under more stress tend to have more physical symptoms. This is a good example of a positive relationship , in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with higher scores on the other. A negative relationship is one in which higher scores on one variable tend to be associated with lower scores on the other. There is a negative relationship between stress and immune system functioning, for example, because higher stress is associated with lower immune system functioning.

Figure 6.3 Scatterplot Showing a Hypothetical Positive Relationship Between Stress and Number of Physical Symptoms. The circled point represents a person whose stress score was 10 and who had three physical symptoms. Pearson’s r for these data is +.51.

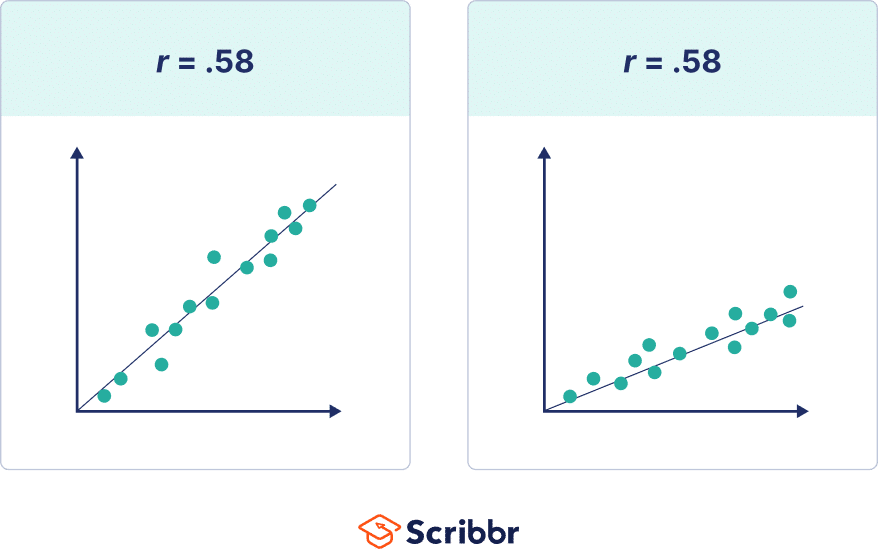

The strength of a correlation between quantitative variables is typically measured using a statistic called Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (or Pearson’s r ) . As Figure 6.4 shows, Pearson’s r ranges from −1.00 (the strongest possible negative relationship) to +1.00 (the strongest possible positive relationship). A value of 0 means there is no relationship between the two variables. When Pearson’s r is 0, the points on a scatterplot form a shapeless “cloud.” As its value moves toward −1.00 or +1.00, the points come closer and closer to falling on a single straight line. Correlation coefficients near ±.10 are considered small, values near ± .30 are considered medium, and values near ±.50 are considered large. Notice that the sign of Pearson’s r is unrelated to its strength. Pearson’s r values of +.30 and −.30, for example, are equally strong; it is just that one represents a moderate positive relationship and the other a moderate negative relationship. With the exception of reliability coefficients, most correlations that we find in Psychology are small or moderate in size. The website http://rpsychologist.com/d3/correlation/ , created by Kristoffer Magnusson, provides an excellent interactive visualization of correlations that permits you to adjust the strength and direction of a correlation while witnessing the corresponding changes to the scatterplot.

Figure 6.4 Range of Pearson’s r, From −1.00 (Strongest Possible Negative Relationship), Through 0 (No Relationship), to +1.00 (Strongest Possible Positive Relationship)

There are two common situations in which the value of Pearson’s r can be misleading. Pearson’s r is a good measure only for linear relationships, in which the points are best approximated by a straight line. It is not a good measure for nonlinear relationships, in which the points are better approximated by a curved line. Figure 6.5, for example, shows a hypothetical relationship between the amount of sleep people get per night and their level of depression. In this example, the line that best approximates the points is a curve—a kind of upside-down “U”—because people who get about eight hours of sleep tend to be the least depressed. Those who get too little sleep and those who get too much sleep tend to be more depressed. Even though Figure 6.5 shows a fairly strong relationship between depression and sleep, Pearson’s r would be close to zero because the points in the scatterplot are not well fit by a single straight line. This means that it is important to make a scatterplot and confirm that a relationship is approximately linear before using Pearson’s r . Nonlinear relationships are fairly common in psychology, but measuring their strength is beyond the scope of this book.

Figure 6.5 Hypothetical Nonlinear Relationship Between Sleep and Depression

The other common situations in which the value of Pearson’s r can be misleading is when one or both of the variables have a limited range in the sample relative to the population. This problem is referred to as restriction of range . Assume, for example, that there is a strong negative correlation between people’s age and their enjoyment of hip hop music as shown by the scatterplot in Figure 6.6. Pearson’s r here is −.77. However, if we were to collect data only from 18- to 24-year-olds—represented by the shaded area of Figure 6.6—then the relationship would seem to be quite weak. In fact, Pearson’s r for this restricted range of ages is 0. It is a good idea, therefore, to design studies to avoid restriction of range. For example, if age is one of your primary variables, then you can plan to collect data from people of a wide range of ages. Because restriction of range is not always anticipated or easily avoidable, however, it is good practice to examine your data for possible restriction of range and to interpret Pearson’s r in light of it. (There are also statistical methods to correct Pearson’s r for restriction of range, but they are beyond the scope of this book).

Figure 6.6 Hypothetical Data Showing How a Strong Overall Correlation Can Appear to Be Weak When One Variable Has a Restricted Range.The overall correlation here is −.77, but the correlation for the 18- to 24-year-olds (in the blue box) is 0.

Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

You have probably heard repeatedly that “Correlation does not imply causation.” An amusing example of this comes from a 2012 study that showed a positive correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.79) between the per capita chocolate consumption of a nation and the number of Nobel prizes awarded to citizens of that nation [2] . It seems clear, however, that this does not mean that eating chocolate causes people to win Nobel prizes, and it would not make sense to try to increase the number of Nobel prizes won by recommending that parents feed their children more chocolate.

There are two reasons that correlation does not imply causation. The first is called the directionality problem . Two variables, X and Y , can be statistically related because X causes Y or because Y causes X . Consider, for example, a study showing that whether or not people exercise is statistically related to how happy they are—such that people who exercise are happier on average than people who do not. This statistical relationship is consistent with the idea that exercising causes happiness, but it is also consistent with the idea that happiness causes exercise. Perhaps being happy gives people more energy or leads them to seek opportunities to socialize with others by going to the gym. The second reason that correlation does not imply causation is called the third-variable problem . Two variables, X and Y , can be statistically related not because X causes Y , or because Y causes X , but because some third variable, Z , causes both X and Y . For example, the fact that nations that have won more Nobel prizes tend to have higher chocolate consumption probably reflects geography in that European countries tend to have higher rates of per capita chocolate consumption and invest more in education and technology (once again, per capita) than many other countries in the world. Similarly, the statistical relationship between exercise and happiness could mean that some third variable, such as physical health, causes both of the others. Being physically healthy could cause people to exercise and cause them to be happier. Correlations that are a result of a third-variable are often referred to as spurious correlations.

Some excellent and funny examples of spurious correlations can be found at http://www.tylervigen.com (Figure 6.7 provides one such example).

“Lots of Candy Could Lead to Violence”

Although researchers in psychology know that correlation does not imply causation, many journalists do not. One website about correlation and causation, http://jonathan.mueller.faculty.noctrl.edu/100/correlation_or_causation.htm , links to dozens of media reports about real biomedical and psychological research. Many of the headlines suggest that a causal relationship has been demonstrated when a careful reading of the articles shows that it has not because of the directionality and third-variable problems.

One such article is about a study showing that children who ate candy every day were more likely than other children to be arrested for a violent offense later in life. But could candy really “lead to” violence, as the headline suggests? What alternative explanations can you think of for this statistical relationship? How could the headline be rewritten so that it is not misleading?

As you have learned by reading this book, there are various ways that researchers address the directionality and third-variable problems. The most effective is to conduct an experiment. For example, instead of simply measuring how much people exercise, a researcher could bring people into a laboratory and randomly assign half of them to run on a treadmill for 15 minutes and the rest to sit on a couch for 15 minutes. Although this seems like a minor change to the research design, it is extremely important. Now if the exercisers end up in more positive moods than those who did not exercise, it cannot be because their moods affected how much they exercised (because it was the researcher who determined how much they exercised). Likewise, it cannot be because some third variable (e.g., physical health) affected both how much they exercised and what mood they were in (because, again, it was the researcher who determined how much they exercised). Thus experiments eliminate the directionality and third-variable problems and allow researchers to draw firm conclusions about causal relationships.

Key Takeaways

- Correlational research involves measuring two variables and assessing the relationship between them, with no manipulation of an independent variable.

- Correlation does not imply causation. A statistical relationship between two variables, X and Y , does not necessarily mean that X causes Y . It is also possible that Y causes X , or that a third variable, Z , causes both X and Y .

- While correlational research cannot be used to establish causal relationships between variables, correlational research does allow researchers to achieve many other important objectives (establishing reliability and validity, providing converging evidence, describing relationships and making predictions)

- Correlation coefficients can range from -1 to +1. The sign indicates the direction of the relationship between the variables and the numerical value indicates the strength of the relationship.

- A cognitive psychologist compares the ability of people to recall words that they were instructed to “read” with their ability to recall words that they were instructed to “imagine.”

- A manager studies the correlation between new employees’ college grade point averages and their first-year performance reports.

- An automotive engineer installs different stick shifts in a new car prototype, each time asking several people to rate how comfortable the stick shift feels.

- A food scientist studies the relationship between the temperature inside people’s refrigerators and the amount of bacteria on their food.

- A social psychologist tells some research participants that they need to hurry over to the next building to complete a study. She tells others that they can take their time. Then she observes whether they stop to help a research assistant who is pretending to be hurt.

2. Practice: For each of the following statistical relationships, decide whether the directionality problem is present and think of at least one plausible third variable.

- People who eat more lobster tend to live longer.

- People who exercise more tend to weigh less.

- College students who drink more alcohol tend to have poorer grades.

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Messerli, F. H. (2012). Chocolate consumption, cognitive function, and Nobel laureates. New England Journal of Medicine, 367 , 1562-1564. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

What is Correlational Research? (+ Design, Examples)

Appinio Research · 04.03.2024 · 30min read

Ever wondered how researchers explore connections between different factors without manipulating them? Correlational research offers a window into understanding the relationships between variables in the world around us. From examining the link between exercise habits and mental well-being to exploring patterns in consumer behavior, correlational studies help us uncover insights that shape our understanding of human behavior, inform decision-making, and drive innovation. In this guide, we'll dive into the fundamentals of correlational research, exploring its definition, importance, ethical considerations, and practical applications across various fields. Whether you're a student delving into research methods or a seasoned researcher seeking to expand your methodological toolkit, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and skills to conduct and interpret correlational studies effectively.

What is Correlational Research?

Correlational research is a methodological approach used in scientific inquiry to examine the relationship between two or more variables. Unlike experimental research, which seeks to establish cause-and-effect relationships through manipulation and control of variables, correlational research focuses on identifying and quantifying the degree to which variables are related to one another. This method allows researchers to investigate associations, patterns, and trends in naturalistic settings without imposing experimental manipulations.

Importance of Correlational Research

Correlational research plays a crucial role in advancing scientific knowledge across various disciplines. Its importance stems from several key factors:

- Exploratory Analysis : Correlational studies provide a starting point for exploring potential relationships between variables. By identifying correlations, researchers can generate hypotheses and guide further investigation into causal mechanisms and underlying processes.

- Predictive Modeling: Correlation coefficients can be used to predict the behavior or outcomes of one variable based on the values of another variable. This predictive ability has practical applications in fields such as economics, psychology, and epidemiology, where forecasting future trends or outcomes is essential.

- Diagnostic Purposes: Correlational analyses can help identify patterns or associations that may indicate the presence of underlying conditions or risk factors. For example, correlations between certain biomarkers and disease outcomes can inform diagnostic criteria and screening protocols in healthcare.

- Theory Development: Correlational research contributes to theory development by providing empirical evidence for proposed relationships between variables. Researchers can refine and validate theoretical models in their respective fields by systematically examining correlations across different contexts and populations.

- Ethical Considerations: In situations where experimental manipulation is not feasible or ethical, correlational research offers an alternative approach to studying naturally occurring phenomena. This allows researchers to address research questions that may otherwise be inaccessible or impractical to investigate.

Correlational vs. Causation in Research

It's important to distinguish between correlation and causation in research. While correlational studies can identify relationships between variables, they cannot establish causal relationships on their own. Several factors contribute to this distinction:

- Directionality: Correlation does not imply the direction of causation. A correlation between two variables does not indicate which variable is causing the other; it merely suggests that they are related in some way. Additional evidence, such as experimental manipulation or longitudinal studies, is needed to establish causality.

- Third Variables: Correlations may be influenced by third variables, also known as confounding variables, that are not directly measured or controlled in the study. These third variables can create spurious correlations or obscure true causal relationships between the variables of interest.

- Temporal Sequence: Causation requires a temporal sequence, with the cause preceding the effect in time. Correlational studies alone cannot establish the temporal order of events, making it difficult to determine whether one variable causes changes in another or vice versa.

Understanding the distinction between correlation and causation is critical for interpreting research findings accurately and drawing valid conclusions about the relationships between variables. While correlational research provides valuable insights into associations and patterns, establishing causation typically requires additional evidence from experimental studies or other research designs.

Key Concepts in Correlation

Understanding key concepts in correlation is essential for conducting meaningful research and interpreting results accurately.

Correlation Coefficient

The correlation coefficient is a statistical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. It's denoted by the symbol r and ranges from -1 to +1.

- A correlation coefficient of -1 indicates a perfect negative correlation, meaning that as one variable increases, the other decreases in a perfectly predictable manner.

- A coefficient of +1 signifies a perfect positive correlation, where both variables increase or decrease together in perfect sync.

- A coefficient of 0 implies no correlation, indicating no systematic relationship between the variables.

Strength and Direction of Correlation

The strength of correlation refers to how closely the data points cluster around a straight line on the scatterplot. A correlation coefficient close to -1 or +1 indicates a strong relationship between the variables, while a coefficient close to 0 suggests a weak relationship.

- Strong correlation: When the correlation coefficient approaches -1 or +1, it indicates a strong relationship between the variables. For example, a correlation coefficient of -0.9 suggests a strong negative relationship, while a coefficient of +0.8 indicates a strong positive relationship.

- Weak correlation: A correlation coefficient close to 0 indicates a weak or negligible relationship between the variables. For instance, a coefficient of -0.1 or +0.1 suggests a weak correlation where the variables are minimally related.

The direction of correlation determines how the variables change relative to each other.

- Positive correlation: When one variable increases, the other variable also tends to increase. Conversely, when one variable decreases, the other variable tends to decrease. This is represented by a positive correlation coefficient.

- Negative correlation: In a negative correlation, as one variable increases, the other variable tends to decrease. Similarly, when one variable decreases, the other variable tends to increase. This relationship is indicated by a negative correlation coefficient.

Scatterplots

A scatterplot is a graphical representation of the relationship between two variables. Each data point on the plot represents the values of both variables for a single observation. By plotting the data points on a Cartesian plane, you can visualize patterns and trends in the relationship between the variables.

- Interpretation: When examining a scatterplot, observe the pattern of data points. If the points cluster around a straight line, it indicates a strong correlation. However, if the points are scattered randomly, it suggests a weak or no correlation.

- Outliers: Identify any outliers or data points that deviate significantly from the overall pattern. Outliers can influence the correlation coefficient and may warrant further investigation to determine their impact on the relationship between variables.

- Line of Best Fit: In some cases, you may draw a line of best fit through the data points to visually represent the overall trend in the relationship. This line can help illustrate the direction and strength of the correlation between the variables.

Understanding these key concepts will enable you to interpret correlation coefficients accurately and draw meaningful conclusions from your data.

How to Design a Correlational Study?

When embarking on a correlational study, careful planning and consideration are crucial to ensure the validity and reliability of your research findings.

Research Question Formulation

Formulating clear and focused research questions is the cornerstone of any successful correlational study. Your research questions should articulate the variables you intend to investigate and the nature of the relationship you seek to explore. When formulating your research questions:

- Be Specific: Clearly define the variables you are interested in studying and the population to which your findings will apply.

- Be Testable: Ensure that your research questions are empirically testable using correlational methods. Avoid vague or overly broad questions that are difficult to operationalize.

- Consider Prior Research: Review existing literature to identify gaps or unanswered questions in your area of interest. Your research questions should build upon prior knowledge and contribute to advancing the field.

For example, if you're interested in examining the relationship between sleep duration and academic performance among college students, your research question might be: "Is there a significant correlation between the number of hours of sleep per night and GPA among undergraduate students?"

Participant Selection

Selecting an appropriate sample of participants is critical to ensuring the generalizability and validity of your findings. Consider the following factors when selecting participants for your correlational study:

- Population Characteristics: Identify the population of interest for your study and ensure that your sample reflects the demographics and characteristics of this population.

- Sampling Method: Choose a sampling method that is appropriate for your research question and accessible, given your resources and constraints. Standard sampling methods include random sampling, stratified sampling, and convenience sampling.

- Sample Size: Determine the appropriate sample size based on factors such as the effect size you expect to detect, the desired level of statistical power, and practical considerations such as time and budget constraints.

For example, suppose you're studying the relationship between exercise habits and mental health outcomes in adults aged 18-65. In that case, you might use stratified random sampling to ensure representation from different age groups within the population.

Variables Identification

Identifying and operationalizing the variables of interest is essential for conducting a rigorous correlational study. When identifying variables for your research:

- Independent and Dependent Variables: Clearly distinguish between independent variables (factors that are hypothesized to influence the outcome) and dependent variables (the outcomes or behaviors of interest).

- Control Variables: Identify any potential confounding variables or extraneous factors that may influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables. These variables should be controlled for in your analysis.

- Measurement Scales: Determine the appropriate measurement scales for your variables (e.g., nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio) and select valid and reliable measures for assessing each construct.

For instance, if you're investigating the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and academic achievement, SES would be your independent variable, while academic achievement would be your dependent variable. You might measure SES using a composite index based on factors such as income, education level, and occupation.

Data Collection Methods

Selecting appropriate data collection methods is essential for obtaining reliable and valid data for your correlational study. When choosing data collection methods:

- Quantitative vs. Qualitative : Determine whether quantitative or qualitative methods are best suited to your research question and objectives. Correlational studies typically involve quantitative data collection methods like surveys, questionnaires, or archival data analysis.

- Instrument Selection: Choose measurement instruments that are valid, reliable, and appropriate for your variables of interest. Pilot test your instruments to ensure clarity and comprehension among your target population.

- Data Collection Procedures : Develop clear and standardized procedures for data collection to minimize bias and ensure consistency across participants and time points.

For example, if you're examining the relationship between smartphone use and sleep quality among adolescents, you might administer a self-report questionnaire assessing smartphone usage patterns and sleep quality indicators such as sleep duration and sleep disturbances.

Crafting a well-designed correlational study is essential for yielding meaningful insights into the relationships between variables. By meticulously formulating research questions , selecting appropriate participants, identifying relevant variables, and employing effective data collection methods, researchers can ensure the validity and reliability of their findings.

With Appinio , conducting correlational research becomes even more seamless and efficient. Our intuitive platform empowers researchers to gather real-time consumer insights in minutes, enabling them to make informed decisions with confidence.

Experience the power of Appinio and unlock valuable insights for your research endeavors. Schedule a demo today and revolutionize the way you conduct correlational studies!

Book a Demo

How to Analyze Correlational Data?

Once you have collected your data in a correlational study, the next crucial step is to analyze it effectively to draw meaningful conclusions about the relationship between variables.

How to Calculate Correlation Coefficients?

The correlation coefficient is a numerical measure that quantifies the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables. There are different types of correlation coefficients, including Pearson's correlation coefficient (for linear relationships), Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (for ordinal data), and Kendall's tau (for non-parametric data). Here, we'll focus on calculating Pearson's correlation coefficient (r), which is commonly used for interval or ratio-level data.

To calculate Pearson's correlation coefficient (r), you can use statistical software such as SPSS, R, or Excel. However, if you prefer to calculate it manually, you can use the following formula:

r = Σ((X - X̄)(Y - Ȳ)) / ((n - 1) * (s_X * s_Y))

- X and Y are the scores of the two variables,

- X̄ and Ȳ are the means of X and Y, respectively,

- n is the number of data points,

- s_X and s_Y are the standard deviations of X and Y, respectively.

Interpreting Correlation Results

Once you have calculated the correlation coefficient (r), it's essential to interpret the results correctly. When interpreting correlation results:

- Magnitude: The absolute value of the correlation coefficient (r) indicates the strength of the relationship between the variables. A coefficient close to 1 or -1 suggests a strong correlation, while a coefficient close to 0 indicates a weak or no correlation.

- Direction: The sign of the correlation coefficient (positive or negative) indicates the direction of the relationship between the variables. A positive correlation coefficient indicates a positive relationship (as one variable increases, the other tends to increase), while a negative correlation coefficient indicates a negative relationship (as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease).

- Statistical Significance : Assess the statistical significance of the correlation coefficient to determine whether the observed relationship is likely to be due to chance. This is typically done using hypothesis testing, where you compare the calculated correlation coefficient to a critical value based on the sample size and desired level of significance (e.g., α =0.05).

Statistical Significance

Determining the statistical significance of the correlation coefficient involves conducting hypothesis testing to assess whether the observed correlation is likely to occur by chance. The most common approach is to use a significance level (alpha, α ) of 0.05, which corresponds to a 5% chance of obtaining the observed correlation coefficient if there is no true relationship between the variables.

To test the null hypothesis that the correlation coefficient is zero (i.e., no correlation), you can use inferential statistics such as the t-test or z-test. If the calculated p-value is less than the chosen significance level (e.g., p <0.05), you can reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the correlation coefficient is statistically significant.

Remember that statistical significance does not necessarily imply practical significance or the strength of the relationship. Even a statistically significant correlation with a small effect size may not be meaningful in practical terms.

By understanding how to calculate correlation coefficients, interpret correlation results, and assess statistical significance, you can effectively analyze correlational data and draw accurate conclusions about the relationships between variables in your study.

Correlational Research Limitations

As with any research methodology, correlational studies have inherent considerations and limitations that researchers must acknowledge and address to ensure the validity and reliability of their findings.

Third Variables

One of the primary considerations in correlational research is the presence of third variables, also known as confounding variables. These are extraneous factors that may influence or confound the observed relationship between the variables under study. Failing to account for third variables can lead to spurious correlations or erroneous conclusions about causality.

For example, consider a correlational study examining the relationship between ice cream consumption and drowning incidents. While these variables may exhibit a positive correlation during the summer months, the true causal factor is likely to be a third variable—such as hot weather—that influences both ice cream consumption and swimming activities, thereby increasing the risk of drowning.

To address the influence of third variables, researchers can employ various strategies, such as statistical control techniques, experimental designs (when feasible), and careful operationalization of variables.

Causal Inferences

Correlation does not imply causation—a fundamental principle in correlational research. While correlational studies can identify relationships between variables, they cannot determine causality. This is because correlation merely describes the degree to which two variables co-vary; it does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship between them.

For example, consider a correlational study that finds a positive relationship between the frequency of exercise and self-reported happiness. While it may be tempting to conclude that exercise causes happiness, it's equally plausible that happier individuals are more likely to exercise regularly. Without experimental manipulation and control over potential confounding variables, causal inferences cannot be made.

To strengthen causal inferences in correlational research, researchers can employ longitudinal designs, experimental methods (when ethical and feasible), and theoretical frameworks to guide their interpretations.

Sample Size and Representativeness

The size and representativeness of the sample are critical considerations in correlational research. A small or non-representative sample may limit the generalizability of findings and increase the risk of sampling bias.

For example, if a correlational study examines the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and educational attainment using a sample composed primarily of high-income individuals, the findings may not accurately reflect the broader population's experiences. Similarly, an undersized sample may lack the statistical power to detect meaningful correlations or relationships.

To mitigate these issues, researchers should aim for adequate sample sizes based on power analyses, employ random or stratified sampling techniques to enhance representativeness and consider the demographic characteristics of the target population when interpreting findings.

Ensure your survey delivers accurate insights by using our Sample Size Calculator . With customizable options for margin of error, confidence level, and standard deviation, you can determine the optimal sample size to ensure representative results. Make confident decisions backed by robust data.

Reliability and Validity

Ensuring the reliability and validity of measures is paramount in correlational research. Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of measurement over time, whereas validity pertains to the accuracy and appropriateness of measurement in capturing the intended constructs.

For example, suppose a correlational study utilizes self-report measures of depression and anxiety. In that case, it's essential to assess the measures' reliability (e.g., internal consistency, test-retest reliability) and validity (e.g., content validity, criterion validity) to ensure that they accurately reflect participants' mental health status.

To enhance reliability and validity in correlational research, researchers can employ established measurement scales, pilot-test instruments, use multiple measures of the same construct, and assess convergent and discriminant validity.

By addressing these considerations and limitations, researchers can enhance the robustness and credibility of their correlational studies and make more informed interpretations of their findings.

Correlational Research Examples and Applications

Correlational research is widely used across various disciplines to explore relationships between variables and gain insights into complex phenomena. We'll examine examples and applications of correlational studies, highlighting their practical significance and impact on understanding human behavior and societal trends across various industries and use cases.

Psychological Correlational Studies

In psychology, correlational studies play a crucial role in understanding various aspects of human behavior, cognition, and mental health. Researchers use correlational methods to investigate relationships between psychological variables and identify factors that may contribute to or predict specific outcomes.

For example, a psychological correlational study might examine the relationship between self-esteem and depression symptoms among adolescents. By administering self-report measures of self-esteem and depression to a sample of teenagers and calculating the correlation coefficient between the two variables, researchers can assess whether lower self-esteem is associated with higher levels of depression symptoms.

Other examples of psychological correlational studies include investigating the relationship between:

- Parenting styles and academic achievement in children

- Personality traits and job performance in the workplace

- Stress levels and coping strategies among college students

These studies provide valuable insights into the factors influencing human behavior and mental well-being, informing interventions and treatment approaches in clinical and counseling settings.

Business Correlational Studies

Correlational research is also widely utilized in the business and management fields to explore relationships between organizational variables and outcomes. By examining correlations between different factors within an organization, researchers can identify patterns and trends that may impact performance, productivity, and profitability.

For example, a business correlational study might investigate the relationship between employee satisfaction and customer loyalty in a retail setting. By surveying employees to assess their job satisfaction levels and analyzing customer feedback and purchase behavior, researchers can determine whether higher employee satisfaction is correlated with increased customer loyalty and retention.

Other examples of business correlational studies include examining the relationship between:

- Leadership styles and employee motivation

- Organizational culture and innovation

- Marketing strategies and brand perception

These studies provide valuable insights for organizations seeking to optimize their operations, improve employee engagement, and enhance customer satisfaction.

Marketing Correlational Studies

In marketing, correlational studies are instrumental in understanding consumer behavior, identifying market trends, and optimizing marketing strategies. By examining correlations between various marketing variables, researchers can uncover insights that drive effective advertising campaigns, product development, and brand management.

For example, a marketing correlational study might explore the relationship between social media engagement and brand loyalty among millennials. By collecting data on millennials' social media usage, brand interactions, and purchase behaviors, researchers can analyze whether higher levels of social media engagement correlate with increased brand loyalty and advocacy.

Another example of a marketing correlational study could focus on investigating the relationship between pricing strategies and customer satisfaction in the retail sector. By analyzing data on pricing fluctuations, customer feedback , and sales performance, researchers can assess whether pricing strategies such as discounts or promotions impact customer satisfaction and repeat purchase behavior.

Other potential areas of inquiry in marketing correlational studies include examining the relationship between:

- Product features and consumer preferences

- Advertising expenditures and brand awareness

- Online reviews and purchase intent

These studies provide valuable insights for marketers seeking to optimize their strategies, allocate resources effectively, and build strong relationships with consumers in an increasingly competitive marketplace. By leveraging correlational methods, marketers can make data-driven decisions that drive business growth and enhance customer satisfaction.

Correlational Research Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are paramount in all stages of the research process, including correlational studies. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines to ensure the rights, well-being, and privacy of participants are protected. Key ethical considerations to keep in mind include:

- Informed Consent: Obtain informed consent from participants before collecting any data. Clearly explain the purpose of the study, the procedures involved, and any potential risks or benefits. Participants should have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

- Confidentiality: Safeguard the confidentiality of participants' data. Ensure that any personal or sensitive information collected during the study is kept confidential and is only accessible to authorized individuals. Use anonymization techniques when reporting findings to protect participants' privacy.

- Voluntary Participation: Ensure that participation in the study is voluntary and not coerced. Participants should not feel pressured to take part in the study or feel that they will suffer negative consequences for declining to participate.

- Avoiding Harm: Take measures to minimize any potential physical, psychological, or emotional harm to participants. This includes avoiding deceptive practices, providing appropriate debriefing procedures (if necessary), and offering access to support services if participants experience distress.

- Deception: If deception is necessary for the study, it must be justified and minimized. Deception should be disclosed to participants as soon as possible after data collection, and any potential risks associated with the deception should be mitigated.

- Researcher Integrity: Maintain integrity and honesty throughout the research process. Avoid falsifying data, manipulating results, or engaging in any other unethical practices that could compromise the integrity of the study.

- Respect for Diversity: Respect participants' cultural, social, and individual differences. Ensure that research protocols are culturally sensitive and inclusive, and that participants from diverse backgrounds are represented and treated with respect.

- Institutional Review: Obtain ethical approval from institutional review boards or ethics committees before commencing the study. Adhere to the guidelines and regulations set forth by the relevant governing bodies and professional organizations.

Adhering to these ethical considerations ensures that correlational research is conducted responsibly and ethically, promoting trust and integrity in the scientific community.

Correlational Research Best Practices and Tips

Conducting a successful correlational study requires careful planning, attention to detail, and adherence to best practices in research methodology. Here are some tips and best practices to help you conduct your correlational research effectively:

- Clearly Define Variables: Clearly define the variables you are studying and operationalize them into measurable constructs. Ensure that your variables are accurately and consistently measured to avoid ambiguity and ensure reliability.

- Use Valid and Reliable Measures: Select measurement instruments that are valid and reliable for assessing your variables of interest. Pilot test your measures to ensure clarity, comprehension, and appropriateness for your target population.

- Consider Potential Confounding Variables: Identify and control for potential confounding variables that could influence the relationship between your variables of interest. Consider including control variables in your analysis to isolate the effects of interest.