Sick Leave Case Study

What kelly should do, cause of the dispute, importance of compromise, tangible and intangible factors.

The most appropriate action that Kelly should take is to call The Conference of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR), since Mr. Higashi is not willing to cooperate with the Assistant Language Teachers (ALTs). When employees sign employment contracts, it is clearly stipulated what each party should do for the other (Lewicki, Barry, & Saunders, 2011).

This was the case with the contract Kelly signed because the number of sick and paid leaves was indicated. She should therefore not be denied sick leave since it is different from the paid one. The treatment she is receiving from Mr. Higashi is thus unwarranted since it violates the employment contract.

Discussing the issue further with him will not be helpful because he has already formed opinions regarding ALT foreign assistants. He is supposed to respond to her concerns when she is asked to sign the forms by the accountant but he excuses himself by saying that he has an important meeting to attend. This implies that he is not ready to talk to her thus her attempts to talk to him will be futile.

CLAIR will handle this problem since it is the organization mandated with the task of looking into issues of ALTs. The body ensures that they are comfortable by maintaining their welfare and counseling them.

In addition, it works towards speedy resolutions of any matters affecting them. They should be accorded the respect they deserve since they play an important role as employees and this includes honoring the contract they signed.

Kelly’s dispute is that the employment contract she signed stipulates the number of sick and paid leaves entitled to ALT participants. She therefore argues that denying her sick leave contravenes the contents of the contract. She was genuinely sick but after returning to the office, she is forced to sign two days for paid leave instead of the sick one.

Once she informs the accountant and Mr. Higashi of the mistake, they both tell her that it is intentional. Higashi tells her that most of the Japanese employees do not go for their paid leaves for love of their jobs.

She argues that she is not Japanese but he tells her that she probably needs to behave like the Japanese because she is in their country. She is disputing the idea of her sick leave being substituted for a paid one because this implies that the number of paid leaves she is entitled to will be reduced. She feels that he should not treat her in such a manner because this is unreasonable of him.

In such a type of conflict, compromise may be an option. Kelly is a junior while Mr. Higashi is her senior in the workplace. It might be difficult for her to concede compromise but for the sake of her job it is advisable for her to compromise. Employees do not always get what they expect from their employers and all they have to do is to tolerate them (Lewicki, Barry, & Saunders, 2010).

Since she is in Japan for a season, there is no reason why she should pick up arguments with the supervisor. She may be labeled deviant and uncooperative and end up being the loser. For the sake of achieving her goals, she should compromise knowing that she is not in the program for the rest of her life.

The case has both tangible and intangible factors. The first tangible factor in the negotiation is that by signing a two-day paid leave instead of a sick one, the number of paid leaves that Kelly is entitled to will be reduced.

The second one is that she is not in good terms with Mr. Higashi since he feels that she is not showing full commitment in her work while the third one is that she wants to do things the Canadian way but he tells her to do them the Japanese way.

Apart from the tangible factors, there are also intangible ones. The first intangible factor in the negotiation is that Mr. Higashi focuses on saving the face of the company more than anything else. That is why according to him employees should be fully sacrificial.

The second one is that ALTs are not satisfied with the Japanese style of management because it seems to have some loopholes while the third one is that it is shameful for them not to have joined AJET because it would have addressed their concerns effectively.

Saving the face is more important to Mr. Higashi more than it is to Kelly. This is because loyalty to the company according to him is paramount. Kelly argues that work should not prevent her from enjoying her life. The intangible factors are more important than the tangible ones.

This is because they cannot be felt but they affect the company significantly in that they determine how the company is perceived by people. Kelly believes that the tangible factors are more important than the intangible ones while Higashi argues that the intangible ones are the most important.

Lewicki, J., Barry, B., & Saunders, D. (2010). Negotiation: Readings, Exercises and Cases. New York: McGraw Hill.

Lewicki, J., Barry, B., & Saunders, M. (2011). Essentials of Negotiation. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, July 6). Sick Leave. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-sick-leave/

"Sick Leave." IvyPanda , 6 July 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-sick-leave/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Sick Leave'. 6 July.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Sick Leave." July 6, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-sick-leave/.

1. IvyPanda . "Sick Leave." July 6, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-sick-leave/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Sick Leave." July 6, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/case-study-sick-leave/.

- Prospect and Attribution Theories in Decision Making

- Negotiation and Conflict Resolution at the Workplace

- The Alt-Text Importance and Examples

- Gnome Graphic User Interface and Workspaces

- Liver Disease Management and Treatment

- Music Styles: Difference and Similarity of Styles

- Kelly’s Business: Planning for Growth

- Kelly Sandwich Stop Company's Growth Planning

- Ned Kelly as an Iconic Figure

- "The Sky Is Gray" by Ernest Gaines

- Human resource planning (HRP)

- Improvement in Policy and Procedure of Fast Forward Company

- Managerial Implications of Employee Engagement

- Spotlight on Strategic Human Resource Management

- Building a Restaurant Concept

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Scand J Prim Health Care

- v.33(1); 2015 Mar

GPs’ negotiation strategies regarding sick leave for subjective health complaints

Stein nilsen.

1 Research Unit for General Practice, Uni Research Health, Bergen, Norway

Kirsti Malterud

3 Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Norway

5 Research Unit for General Practice and Section of General Practice, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Erik L Werner

Silje maeland.

2 Department of Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy and Radiography, Faculty of Health and Social Sciences, Bergen University College, Norway

4 Uni Research Health, Bergen, Norway

Liv Heide Magnussen

Objectives . To explore general practitioners’ (GPs’) specific negotiation strategies regarding sick-leave issues with patients suffering from subjective health complaints. Design . Focus-group study. Setting . Nine focus-group interviews in three cities in different regions of Norway. Participants . 48 GPs (31 men, 17 women; age 32–65), participating in a course dealing with diagnostic practice and assessment of sickness certificates related to patients with subjective health complaints. Results . The GPs identified some specific strategies that they claimed to apply when dealing with the question of sick leave for patients with subjective health complaints. The first step would be to build an alliance with the patient by complying with the wish for sick leave, and at the same time searching for information to acquire the patient's perspective. This position would become the basis for the main goal: motivating the patient for a rapid return to work by pointing out the positive effects of staying at work, making legal and moral arguments, and warning against long-term sick leave. Additional solutions might also be applied, such as involving other stakeholders in this process to provide alternatives to sick leave. Conclusions and implications . GPs seem to have a conscious approach to negotiations of sickness certification, as they report applying specific strategies to limit the duration of sick leave due to subjective health complaints. This give-and-take way of handling sick-leave negotiations has been suggested by others to enhance return to work, and should be further encouraged. However, specific effectiveness of this strategy is yet to be proven, and further investigation into the actual dealings between doctor and patients in these complex encounters is needed.

Decisions concerning sick leave for patients with subjective health complaints (SHC) are among GPs’ most demanding tasks.

- GPs are aware of and apply specific strategies when negotiating sick-leave issues with patients with SHC, seeking to limit the sick-leave duration.

- Building an alliance by trying to understand the patient's situation and seeking deeper knowledge of the patient's request was considered to be a necessary starting point in these negotiations.

- Focusing on early return to work by emphasizing the benefits of work, bringing up legal issues, and cooperation with the other stakeholders were identified as the main elements in further negotiations.

Introduction

The sick-leave rate in Norway is higher than elsewhere in OECD countries [ 1 ]. Musculoskeletal pain, tiredness, anxiety, or gastrointestinal complaints, often referred to as subjective health complaints (SHC) [ 2 ], are among the main reasons why people ask for sickness certification [ 3 ]. The social and economic costs related to absence from work have concerned the authorities, and several initiatives have been introduced to control the situation. In Norway, as in a number of other Western countries, doctors have been given the assignment of providing medical premises for sickness benefits, and there is an increased focus on the doctor's role in sickness certification internationally. In the public debate, general practitioners (GPs) have been accused of taking a passive and indifferent attitude towards issuing sickness certificates. GPs admittedly have reported that they find decisions regarding sickness certification, especially in patients with SHC, challenging and frustrating [ 4–6 ]. Lack of competence in assessing work ability has been expressed, particularly in patients with psychiatric conditions. Thus, sick-leave negotiations may be avoided due to time constraints [ 7 ]. GPs miss objective evidence of illness and lack of work ability in these cases, and must rely on the patient's own report when deciding whether he/she is eligible for sickness certification [ 8 ]. Prior knowledge of the patient, the patient’ s ability to generate sympathy, and the doctor’ s own experience as a patient are among factors that doctors report as having an influence on their decisions [ 4 ].

From the discipline of public policy, Michael Lipsky describes how public servants, from teachers and police officers to social workers and GPs, interact directly with the public, and in doing so represent the frontlines of government policy [ 9 ]. His concept street level bureaucracy provides a useful perspective to understand the impact of the social structure on what is going on between doctor and patient.

Coming from different clinical professions, the authors shared an interest in the specific process and discussions underlying a sickness certificate decision. More specific insight into GPs’ experiences can provide a base for initiatives to improve the standard of sick-leave assessment. Often, the issue of sick leave in these cases leads to discussions between patient and doctor. There is, however, sparse knowledge of how the actual discussion between doctor and patient on this topic is taking place. We therefore wanted to explore GPs’ specific strategies for negotiation regarding sick-leave issues with patients suffering from SHC.

Design, material, and methods

We conducted a focus-group study with Norwegian GPs attending a workshop concerning sickness certification. A total of 48 GPs (17 women and 31 men, aged 32–65) participated once in nine focus-group sessions (70–90 minutes) with 4–6 participants in each group. This workshop (duration two days) was a single event, arranged by Uni Research Health, as part of a research project. Recruitment was made through advertisement in the journal of the Norwegian Medical Association. The participants’ general practice experience varied from one to 34 years. Most of the GPs worked in an urban setting. About 30% of the GPs were from countries other than Norway, including Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Pakistan, Iraq, and Ethiopia, many of them having a large number of individuals from their native countries as patients. All the participants participated in the focus groups. Three of the groups consisted of men, one of women, while the rest were of mixed gender. In the workshop, participants first assessed all nine videotaped consultations of patients suffering from SHC [ 10 ]. They were then individually requested to decide whether sick leave was appropriate in each case [ 4 ]. In the video consultations the patients were played by different actors, but the content was transcriptions of real consultations. Focus-group discussions were carried out prior to subsequent lectures, thus preventing content from lectures being echoed back in the group discussions. Three of the authors acted as group moderators (ELW, SN, LHM), and one co-moderator in each group took field notes. Open-ended questions regarding sick leave were related to the videotapes. The discussions evolved around the decision on whether or not to issue sickness certificates, and how they would handle the negotiation with the patient in this regard, especially when disagreement occurred. Specific examples from the GPs’ own practices were also brought into the discussions. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Ethics (08/12758) and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (09/20381).

Data were analysed by Systematic Text Condensation, a thematic, cross-case strategy suited for exploratory analysis [ 11 ]. This procedure consists of a four-step analysis: (i) getting a total impression by reading the whole text to identify preliminary themes, (ii) identifying meaning units concerning GPs’ different strategies when negotiating sick leave for patients with SHC, establishing code groups, and sorting the meaning units correspondingly, (iii) abstracting condensates from each code group and its subgroups, (iv) re-conceptualizing the condensates by creating synthesized descriptions of GPs’ strategies. Analysis was supported by Lipsky's theories regarding street-level bureaucracy, focusing on the GPs’ potential trade-offs between the concerns of the patient and the public responsibility [ 9 ].

The GPs reported that they used specific strategies for negotiation of sickness certification with patients with SHC. The first step would be to build an alliance with the patient by complying with the wish for sick leave, and at the same time searching for information to acquire the patient's perspective. This position would become the basis for the main goal: motivating the patient for a rapid return to work, by pointing out the positive effects of staying in work, making legal and moral arguments, and warning against long-term sick leave. Alternative solutions might also be applied, such as involving other stakeholders in the sick-leave process to provide alternatives to prolonged sickness certification. These findings will be elaborated below.

Building an alliance – acquiring the patient's perspectives

There was a general agreement among participants that long-term sick leave for many of the patients with SHC would be counter-productive, with a considerable risk of turning into permanent disability. Nevertheless, many voiced the importance of initially meeting the patient's request for sickness certification in a positive way, seeking to build an alliance. They described in different ways how this alliance could be established by trying to understand the situation from the patient's position, and “walking along” with the patient – a starting point for later negotiations.

An element of alliance building would sometimes be to agree to the first request for sick leave. Since the patient's point of view in the first consultation might be a clear request for a sickness certificate, initial rapport with the patient was considered a prerequisite, before discussing further details. Some GPs also described how, at this step, they explored more deeply the patient's complaints and expressed need for a sickness certificate. It was pointed out in different ways that the initial complaint to justify sick leave could be misleading, with physical complaints often disguising more severe personal or psychological problems. The insight gained by this strategy would make it possible to address the full range of problems, sometimes leading to more accurate management of the situation. An experienced male doctor of 60 working in a rural setting in Eastern Norway gave this advice:

“When I deal with long-term sick leave for conditions I don't quite understand, I always talk to the patient about his work, his marriage, his children and his financial situation. A lot of trouble lies hidden here”.

Rapid return to work is still the main goal

Several of the participants claimed that although rapid return to work was their main goal on behalf of the patient right from the start, they advocated the principle of not pushing this point initially. Some participants warned against giving too much resistance in the first consultation, because this might enhance the possibility that the patient moved to another doctor's list. Others advocated this confrontation style as a way to get rid of a difficult patient. Some described how they would make an early follow-up appointment after a limited initial period of sickness certification, starting to negotiate return to work as soon as possible. This could be obtained by changing to part-time sick leave, or, on some occasions, starting out with this option from the beginning. Some of the GPs emphasized how these strategies of alliance and rapid return to work might be closely linked, as a more or less orchestrated chain of events, where the doctor moved along with the patient from one stage to the next, towards the final goal of terminating the sick leave at an early stage. A female doctor aged 35 years, working in an affluent part of a major city, put it this way:

“I acknowledge their need for a sick-note initially, and bring in the “but” in the next consultation”.

When the GPs intended to motivate their patients for early return to work, several approaches were recommended, using rewards as well as forewarnings. Pointing to the positive effects of work participation on the patient's well-being, they would seek to ease the patient's fear of the potential dangers of re-entering work. At the same time they advocated the moral obligations of participating in society, while warning the patient of the possible drawbacks of staying out of work for a prolonged period such as tardy recovery, economic loss, or falling out of work permanently. A male doctor of 45 explained:

I try to point to the rewards of being able to stay in work, and that work can in fact empower you and bring you better health, while trying not to be too moralistic about it.

Some GPs said they would also bring up their responsibility towards the authorities and the social laws and regulations when arguing against long-term certified sick leave. They might for instance explain their inability to comply with the patient's immediate wishes by pointing to their own obligation to follow the rules. One experienced male doctor said that he would press for termination of sickness certification after eight weeks, pointing to the stricter conditions that Norwegian law applies to prolonged cases. He also admitted that he sometimes exaggerated these rules to bring the patient back to work:

“I might say that I can't write a sick note past the employer's payment period [16 days] or the eight weeks. I think it's a great relief to have these excuses.”

Alternative solutions may be available – other stakeholders might provide options

Some of the participants described how they would also try to point to alternative solutions to sick leave, such as a temporary change to different working tasks, a change to another job, or by encouraging the patient to reorganize family life to ease the perceived domestic stress factors, rather than blaming the job and solving the problem with a sickness certificate.

Furthermore, several of the participants pointed to the possibilities of cooperation with other agencies or partners to find other alternatives to sick leave. They were aware of their legal duty to involve the patient's employer in such cases, but admitted that they did not apply this opportunity as often as they should. They would also sometimes inform the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration (NAV) when feeling uncomfortable about long-term sickness certification, but complained about not receiving due response from the welfare system to such signals. A female GP of 45 related this experience:

“If I sense that this might become a questionable case of prolonged sick leave, I will notify the social security agency right from the start, so they will have the opportunity to intervene at an early stage. But nothing ever happens; not in months. And that's when I kind of give up. What am I supposed to do now?”

In our study, the doctors did not seem to act as careless providers of sickness certificates, but in fact expressed awareness by reporting specific strategies with the aim of seeking to limit the duration of sickness absence for patients with SHC. The overall strategy was described as a stepwise process, consisting of alliance-building and mutual understanding, then actively focusing on early return to work, supported by involvement from other stakeholders.

Methodological considerations

The participants in our study were recruited through a course for GPs dealing with sick leave and related topics. They might have had a certain interest in these issues, implying a potentially more conscious and reflective attitude towards the challenges of sickness certification than other GPs. On the other hand, doctors seeking education in a particular field may be more aware of their shortcomings than their colleagues, and may provide for a more self-reflective discussion. These two factors might balance each other. The fact that the course was free of charge probably made it attractive to a wide group of GPs. We therefore conclude that our sample held satisfactory external validity, and that these results can be transferred to a broad range of GPs working within similar rules and procedures for sick leave [ 12 ]. In the focus-group discussions, participants described their strategies by talking about what they usually did, or would like to do, in specific situations. We do not know whether this takes place in real life. Although the strategies presented by participants were often substantiated by specific examples and experiences, internal validity will be jeopardized if we confuse these descriptions with what actually takes place. An observational study with data drawn from videotapes of real consultations would be needed for such a purpose, and our findings must be interpreted with due caution [ 13 ].

We consider the clinical experience among the authors as a strength when it came to guiding the discussion onto clinically relevant topics, and to recognizing and appreciating the GPs’ work situation and points of reference. On the other hand, this position could also implicate a sympathetic relationship to the informants and their work situation, and thereby prevent a sufficiently reflective view.

Although this study dealt with patients with SHC, the focus-group discussions sometimes took in a broader view, and discussed dilemmas concerning complex long-lasting sickness-certification cases in general. Our findings therefore also shed some light on a broader range of situations where sickness certificates are under consideration. Some aspects of the findings, like balancing medical judgement when it is opposed by the patient's demands, may also be transferred to other situations of negotiations over controversial issues in general practice, such as prescription of antibiotics [ 14 , 15 ].

What is known from before – what does this study add?

In this study GPs demonstrate a wide range of strategies they use when considering sickness certification for patients with SHC. This is somewhat opposed to popular assumptions of GPs as passive servants of a sick-note [ 16–18 ]. Sickness certification in SHC cases in general seems to be patient initiated [ 4 , 19 , 20 ], and the GPs in this study demonstrated great concern about the risk of marginalization following long-term sick leave [ 21 ].

We have previously published research suggesting that GPs do indeed take into account a number of considerations when assessing the need for sick leave [ 4 ]. This paper further reveals how doctors negotiating sick leave seek to find a balance between compassion and flexibility on one side, and impartiality and strict rule-application on the other, facing the dialectic dilemma of all public services. Lipsky's theory fits well with some of the dilemmas of issuing sickness certificates [ 9 ]. However, unlike most other public services, there is no budget to be accounted for by the medical street-level bureaucrat in Norway when it comes to sickness certification. Consequently there are no financial limits to consider and our findings may reflect this situation, as flatly refusing sickness leave when judging it to be questionable was not mentioned by our participants. This is in accordance with findings by Swartling et al. [ 22 ]. GPs’ budget responsibility has an impact in other areas, e.g. drug prescription, and one could hypothesize as to whether freedom from this responsibility may partially explain why the gate-keeping part of the equation is played down in sickness certification discussions [ 23 ].

Balancing society's demand for gate keeping with the need to be supportive and keep on good terms with the patient is a recurrent issue when discussing GPs’ roles in sick leave [ 5 , 7 , 24 ]. In a study by Hiscock et al. [ 16 ], doctors reported having adopted a “give-and take” strategy, and compromise has been found to be a key element in order to avoid conflicts. In our study, the GPs’ descriptions of how their seeking an alliance and reaching an agreement with the patient before turning their attention towards work elaborates on this strategy. The elements of a patient-centred approach in communication are clearly recognizable, and demonstrate a shift from GPs’ more paternalistic attitude of the past [ 25–27 ]. This way of communicating may enhance the return to work. Lynoe et al. [ 27 ] found for example that positive encounters with health care providers combined with feeling respected significantly facilitated patients’ self-estimated ability to return to work, while negative encounters combined with feeling wronged significantly impaired it.

Patients with SHC on long-term sickness absence have further elaborated on how they wish to be encountered by their doctors. They express the need for sufficient time, sympathy, and confidence from their GPs in the process of trying to regain work ability, while a perceived insensitive attitude and pushing too hard towards work might impair their health [ 21 ]. Carefully balancing the concerns of the patient and the public responsibility during negotiations is therefore paramount, and attention to the patient's feelings and opinions must be respected. The GPs in our study expressed a strong awareness of this challenge.

A potential conflict of interest may exist between GPs on one side, and occupational health services and employers on the other, where GPs are seen as primarily concerned with diagnosis and effective treatment, ignoring return to work and quality of life in general [ 28–30 ]. GPs trained in occupational health felt that when they negotiated sickness certification their training helped them to challenge beliefs about work absence being beneficial to patients experiencing ill health [ 31 ]. After training, they felt better equipped to consider patients’ work ability, and issued fewer certificates as a result of this. Our study may balance these findings, as our participants claimed to argue strongly for the benefit of work in negotiations with their patients, and to seek a rapid return to work before all symptoms are relieved. This finding indicates an emerging mutual understanding between GPs and other stakeholders that may prove beneficial in reducing long-term sickness absence.

Functional assessment has been proposed as a tool to adjust the duration of sickness certification periods [ 32 ]. Doctors’ insufficient knowledge of patients’ work demands and lack of contact with the employer may comprise barriers to this approach. Lipsky [ 9 ] also mentions the challenges when street-level bureaucrats have to make a large number of decisions with limited time and information available. None of the participants in our study mentioned assessment of work ability as a main element when deciding whether sick leave was appropriate. Since lack of work ability is an absolute prerequisite for receiving compensation for sickness according to Norwegian social law, as elsewhere, one would expect the doctors to pay some attention to this issue in their discussion with the patient [ 33 ]. When this seems not to be the case, it may reflect that the doctors’ focus in patients with SHC is directed more towards the patient's subjective description of complaints, suffering, and function, as the exact work ability can be difficult to decide or define when dealing with SHC. However, increased attention to this topic when negotiating sickness certification may facilitate return to work.

Long-term sickness absence is the shared responsibility of four principal stakeholders: the doctor, the employer, the social security officer, and the patient him/herself, as pointed out by Werner [ 34 ] and Kiessling & Arreløv [ 7 ]. Our participants’ strategies of turning to legal arguments and hiding behind other public agencies illustrate their reluctance to stand alone, and their need for support and collaboration with the other stakeholders. Closer follow-up of doctors by social security officers has been suggested to improve sensible decision-making in long-term sickness absence [ 35 ]. However, although the GPs in our study were aware of possible options for cooperation and support, they did not take full advantage of these. Fear of breaching confidentiality on the patient's behalf might be a barrier to this approach. A lack of collaboration experienced with social welfare agencies and employers, especially regarding practical difficulties in reaching them, may add to the barriers to cooperation, as pointed out by Swartling et al. [55].

Implications

The GPs participating in this study demonstrated a keen awareness of specific strategies to limit prolonged sick leave for SHC. Still, it is uncertain whether this give-and-take approach to sick-leave negotiations may enhance return to work, as the effects of such efforts are difficult to demonstrate. What is actually taking place behind closed doors in the consultation room when these complex situations are discussed is still unclear. More knowledge is needed regarding complex sick-leave encounters, especially when additional factors beyond the medical ones motivate the patient's wish for sickness certification.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

This study was funded by the Norwegian Research Council (grant no ES432873, with professor Hege R. Eriksen as Principal Investigator).

Sick Leave Negotiation Process

The main reason for a sick leave conflict to occur is based on surface impressions and perceptions issues. Individuals have different perception, values and believes and do not know how to communicate with one another and respect each other due to ones own misunderstanding and own cultural believes.

I will use the example of a person that would like a sickleave payment instead of deduction of two days holiday for the missed working days, to create some case guidance notes.

Let’s add a bit more conflict too it as well… (this example is in many countries legal!)

As an employee and HR have a different understanding of the dispute, effective negotiation is likely to be difficult to achieve, creating so-called framing problems.

This disagreement actually holds no ‘g ood or bad guys ’, by signing off a holiday request instead dispense a sickleave payment. The employee feels that he/she is being treated unfairly, as in most countries the employee has the right to take both holiday and receive paid sick leave, as is stated in the employment contract. He/She does not understand the reasons for not giving it and actually throws his/her employment contract on HR desk to point out the sections applicable – taking quite an aggressive stance. Unfortunately, the employee does not realise that contracts are not as important as building good relationships and conflict is seldom defined by a legal contract alone.

It is about equality and fairness, it about employee rights, should an employee make a formal complaint for the better good of the group, protecting against unjust being done?

What would you do?

Is it is about self-face preservation and using the confrontational strategies trying to display a strong win-lose attitude?

I believe that employees realise that the rules for interaction are not clear and that there is usually a mismatch of expectations on what is expected from the employee by the HR team.

People Management teams take the stance that an employee should take two days paid holidays for the days she was sick. Moreover, HR most likely holds the perception that the employee focuses too much on the disagreement issue , not enough on areas of their commonality or agreement. The employee may argue the position constantly and sees things universally, which is may be too direct and competitive. Non-verbal communication seems a trait that HR is using in many of such occurances.

Although the tangible factors are important, those that are intangible are ones that one cannot seen or touched. This is the main reason why the employee’s sick leave request may have gotten turned down, it is about understanding’s HR perception of the situation, working in harmony is the crucial ingredient for working productively, and in certain countries it is all about being personal or totally opposite.

The breakdown between employee and the employer may have a high price, especially if other employees have similar reactions; it may impact future productivity and it can permanently undermine working relationships . This is where good cross-cultural training for both parties is valuable. A lot of hurdles can be discussed in the onboarding training sessions given by HR and thus this could have all been prevented. Perhaps the employee should have really immersed him/herself in the working culture and organisation.

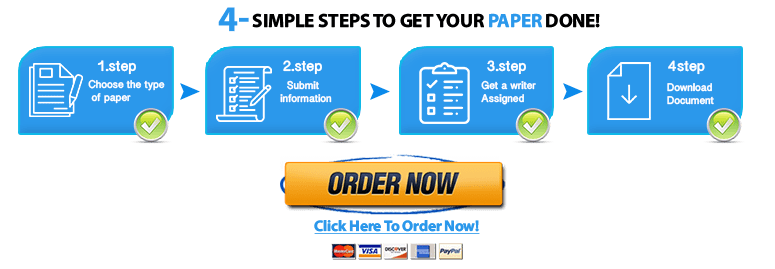

I believe an employee will need to take time to cool down. He/She needs to put the conflict issue away and define a plan of action; from a distributive to integrative strategy, separate individual’s thinking from the conflict, find common interests in the overall conflict and start negotiating. It is all about perception issues as these define the actual problem and even its solution, the employee needs to bridge the gap. Their plan of action should include the following:

The employee should schedule a meeting with a people professional

The employee needs to discuss his/her point of view, but also acknowledge the other side. He/she will need to apologise and make a diligent attempt to resolve this situation. The employee may need to build up a relationship with the organisation that likely he/she never had. To assist in this process the employee can make small concessions, as a signal of good faith. An employee will also need to depersonalise the conflict and both employee and HR, should focus looking for common ‘goals’ since the sick leave conflict tends to magnify differences and minimise any similarities between them. If both parties take the above approach the negotiation will be successful.

I believe the actual answer to employee’s solution to the conflict lies in what B.H. Liddell Hart, historian stated;

Have unlimited patience. Never corner an opponent and always assist the other person to save his face Put yourself in his shoes-so as to see things through his eyes. Avoid self-righteousness like the devil-nothing is so self-blinding.

What as a HR professional would you do with this case/employee?

Would you pay out sick leave? or take the holiday?

Would you do something tangible/intangible ‘under the table’, work something out with the employee? – or would you follow process?

© New To HR

Interviewing Introverts

Doctor Who An HR Professional In Disguise

No comments, post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Follow Us on Social

We create meaningful reasons for people to love HR ♥

- Browse Topics

- Executive Committee

- Affiliated Faculty

- Harvard Negotiation Project

- Great Negotiator

- American Secretaries of State Project

- Awards, Grants, and Fellowships

- Negotiation Programs

- Mediation Programs

- One-Day Programs

- In-House Training and Custom Programs

- In-Person Programs

- Online Programs

- Advanced Materials Search

- Contact Information

- The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Negotiation Journal

- Harvard Negotiation Law Review

- Working Conference on AI, Technology, and Negotiation

- Free Reports and Program Guides

Free Videos

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Event Series

- Our Mission

- Keyword Index

PON – Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School - https://www.pon.harvard.edu

Team-Building Strategies: Building a Winning Team for Your Organization

Discover how to build a winning team and boost your business negotiation results in this free special report, Team Building Strategies for Your Organization, from Harvard Law School.

Teach by Example with These Negotiation Case Studies

By Lara SanPietro — on January 17th, 2024 / Teaching Negotiation

Negotiation case studies use the power of example to teach negotiation strategies. Looking to past negotiations where students can analyze what approaches the parties took and how effective they were in reaching an agreement, can help students gain new insights into negotiation dynamics. The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center (TNRC) has a variety of negotiation case studies to help students learn by example.

Negotiating About Pandas for San Diego Zoo – Featured Case Study

The Negotiating About Pandas for San Diego Zoo case study centers on the most challenging task for a negotiator: to reach a satisfactory agreement with a tough counterpart from a position of low power—and to do so in an uncommon context. This case focuses on the executive director of a zoo in the U.S. who seeks two giant pandas, an endangered species, from their only source on the planet: China. Compounding the difficulty, many other zoos are also trying to obtain giant pandas—the “rock stars” of the zoo world. Yet, as if relative bargaining power were not enough to preoccupy the zoo director, it is not his only major challenge.

His zoo’s initiative attracts attention from a wide range of stakeholders, from nongovernmental (NGO) conservation groups to government agencies on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. Several of these organizations ardently oppose the zoo’s efforts, while others change their positions over time. All of this attention influences the zoo’s negotiations. Therefore, a second challenging task for the zoo director is to monitor events in the negotiating environment and manage their effects on his negotiations with Chinese counterparts.

This three-part case is based on the actual negotiations and offers lessons for business, law and government students and professionals in multiple subject areas. Preview a Negotiating About Pandas for San Diego Zoo Teacher’s Package to learn more.

Camp Lemonnier Case Study – Featured Case Study

In the spring of 2014, representatives from the United States of America and the Republic of Djibouti were in the midst of renegotiations over Camp Lemonnier, the only permanent U.S. base on the continent of Africa. Djibouti, bordering Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, has been home to Camp Lemonnier since the September 11, 2001 attacks prompted the United States to seek a temporary staging ground for U.S. Marines in the region. Since then, Camp Lemonnier has expanded to nearly 500 acres and a base of unparalleled importance, in part because it is one of the busiest Predator drone bases outside of the Afghan warzone.

Tensions between the United States and Djibouti have flared in recent years, due in large part to a string of collisions and close calls because of Djiboutian air-traffic controllers’ job performance at the airport. Americans have complained about the training of air-traffic controllers at the commercial airport. Additionally, labor disputes have arisen at the base where the United States is one of the largest non-government employers within the country.

Major lessons of this case study include:

- Defining BATNA: what is each party’s BATNA?

- Understanding the Zone of Possible Agreement (ZOPA)

- The impact of culture in negotiation.

- Uncovering interests.

- Principal-agent dynamics.

- Uncovering sources of power in negotiation.

This case is based on the real 2014 negotiations between the United States of America and the Republic of Djibouti. Preview a Camp Lemonnier Case Study Teacher’s Package to learn more.

A Green Victory Against Great Odds, But Was It Too Little Too Late? – Featured Case Study

This case study provides an intimate view into the fierce battle among major US nonprofit environmental groups, Members of Congress, and industry over energy policy in 2007. The resulting law slashed pollution by raising car efficiency regulations for the first time in three decades. For negotiators and advocates, this case provides important lessons about cultivating champions, neutralizing opponents, organizing the masses, and using the right message at the right time.

This case is based on the actual negotiations and offers lessons for business, government, climate change, sustainability, corporate social responsibility, and more. Preview A Green Victory Against Great Odds Teacher’s Package to learn more.

Negotiating a Template for Labor Standards – Featured Case Study

Negotiating a Template for Labor Standards: The U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement is a detailed factual case study that tracks the negotiation of the labor provisions in the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement signed into law on January 1, 2004. It draws upon a range of published and unpublished sources and interview with some of the primary players to give a true inside look into a challenging international negotiation. Written primarily from the point of view of the lead U.S. negotiator for the labor chapter, the case study discusses the two countries’ interests and positions on the labor provisions, the possible templates available from prior agreements, the complex political maneuvering involved, and the course of the negotiations themselves – from the opening talks to the various obstacles to the final post-agreement celebration. Preview a Negotiating a Template for Labor Standards Teacher’s Package to learn more.

______________________

Take your training to the next level with the TNRC

The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center offers a wide range of effective teaching materials, including

- Over 250 negotiation exercises and role-play simulations

- Critical case studies

- Enlightening periodicals

- More than 30 videos

- 100-plus books

TNRC negotiation exercises and teaching materials are designed for educational purposes. They are used in college classroom settings or corporate training settings; used by mediators and facilitators seeking to introduce their clients to a process or issue; and used by individuals who want to enhance their negotiation skills and knowledge.

Negotiation exercises and role-play simulations introduce participants to new negotiation and dispute resolution tools, techniques and strategies. Our videos, books, case studies, and periodicals are also a helpful way of introducing students to key concepts while addressing the theory and practice of negotiation.

Check out all that the TNRC has in store >>

Related Posts

- Check Out the All-In-One Curriculum Packages!

- Teach Your Students to Negotiate Cross-Border Water Conflicts

- Asynchronous Learning: Negotiation Exercises to Keep Students Engaged Outside the Classroom

- Planning for Cyber Defense of Critical Urban Infrastructure

- New Simulation: Negotiating a Management Crisis

Click here to cancel reply.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Negotiation and Leadership

- Learn More about Negotiation and Leadership

NEGOTIATION MASTER CLASS

- Learn More about Harvard Negotiation Master Class

Negotiation Essentials Online

- Learn More about Negotiation Essentials Online

Beyond the Back Table: Working with People and Organizations to Get to Yes

- Download Program Guide: March 2024

- Register Online: March 2024

- Learn More about Beyond the Back Table

Select Your Free Special Report

- Negotiation and Leadership Fall 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Essentials Online (NEO) Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Beyond the Back Table Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Master Class May 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Make the Most of Online Negotiations

- Managing Multiparty Negotiations

- Getting the Deal Done

- Salary Negotiation: How to Negotiate Salary: Learn the Best Techniques to Help You Manage the Most Difficult Salary Negotiations and What You Need to Know When Asking for a Raise

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiation: Cross Cultural Communication Techniques and Negotiation Skills From International Business and Diplomacy

Teaching Negotiation Resource Center

- Teaching Materials and Publications

Stay Connected to PON

Preparing for negotiation.

Understanding how to arrange the meeting space is a key aspect of preparing for negotiation. In this video, Professor Guhan Subramanian discusses a real world example of how seating arrangements can influence a negotiator’s success. This discussion was held at the 3 day executive education workshop for senior executives at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

Guhan Subramanian is the Professor of Law and Business at the Harvard Law School and Professor of Business Law at the Harvard Business School.

Articles & Insights

- Negotiation Examples: How Crisis Negotiators Use Text Messaging

- For Sellers, The Anchoring Effects of a Hidden Price Can Offer Advantages

- BATNA Examples—and What You Can Learn from Them

- Taylor Swift: Negotiation Mastermind?

- Power and Negotiation: Advice on First Offers

- How to Deal with Cultural Differences in Negotiation

- Dear Negotiation Coach: Coping with a Change-of-Control Provision

- The Importance of Negotiation in Business and Your Career

- Negotiation in Business: Starbucks and Kraft’s Coffee Conflict

- Negotiation Examples in Real Life: Buying a Home

- Advanced Negotiation Strategies and Concepts: Hostage Negotiation Tips for Business Negotiators

- Negotiating the Good Friday Agreement

- Communication and Conflict Management: Responding to Tough Questions

- How to Maintain Your Power While Engaging in Conflict Resolution

- Conflict-Management Styles: Pitfalls and Best Practices

- Negotiating Change During the Covid-19 Pandemic

- AI Negotiation in the News

- Crisis Communication Examples: What’s So Funny?

- Crisis Negotiation Skills: The Hostage Negotiator’s Drill

- Police Negotiation Techniques from the NYPD Crisis Negotiations Team

- Managing Difficult Employees, and Those Who Just Seem Difficult

- How to Deal with Difficult Customers

- Negotiating with Difficult Personalities and “Dark” Personality Traits

- Consensus-Building Techniques

- Ethics in Negotiations: How to Deal with Deception at the Bargaining Table

- Perspective Taking and Empathy in Business Negotiations

- Dealmaking and the Anchoring Effect in Negotiations

- Negotiating Skills: Learn How to Build Trust at the Negotiation Table

- How to Counter Offer Successfully With a Strong Rationale

- Negotiation Techniques: The First Offer Dilemma in Negotiations

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Examples: Restorative Justice

- Choose the Right Dispute Resolution Process

- Union Strikes and Dispute Resolution Strategies

- What Is an Umbrella Agreement?

- What is Dispute System Design?

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiations and the Importance of Communication in International Business Deals

- Managing Cultural Differences in Negotiation

- Top 10 International Business Negotiation Case Studies

- Hard Bargaining in Negotiation

- Prompting Peace Negotiations

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Leadership Styles: Uncovering Bias and Generating Mutual Gains

- The Contingency Theory of Leadership: A Focus on Fit

- Servant Leadership and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge

- How to Negotiate in Cross-Cultural Situations

- Counteracting Negotiation Biases Like Race and Gender in the Workplace

- What Makes a Good Mediator?

- Why is Negotiation Important: Mediation in Transactional Negotiations

- The Mediation Process and Dispute Resolution

- Negotiations and Logrolling: Discover Opportunities to Generate Mutual Gains

- How Mediation Can Help Resolve Pro Sports Disputes

- Identify Your Negotiation Style: Advanced Negotiation Strategies and Concepts

- How to Negotiate via Text Message

- 5 Types of Negotiation Skills

- 5 Tips for Improving Your Negotiation Skills

- 10 Negotiation Failures

- Negotiation Journal celebrates 40th anniversary, new publisher, and diamond open access in 2024

- Ethics and Negotiation: 5 Principles of Negotiation to Boost Your Bargaining Skills in Business Situations

- 10 Negotiation Training Skills Every Organization Needs

- Trust in Negotiation: Does Gender Matter?

- Use a Negotiation Preparation Worksheet for Continuous Improvement

- How to Negotiate a Higher Salary

- Renegotiate Salary to Your Advantage

- How to Counter a Job Offer: Avoid Common Mistakes

- Salary Negotiation: How to Ask for a Higher Salary

- How to Ask for a Salary Increase

- How to Win at Win-Win Negotiation

- Labor Negotiation Strategies

- How to Create Win-Win Situations

- For NFL Players, a Win-Win Negotiation Contract Only in Retrospect?

- Win-Lose Negotiation Examples

PON Publications

- Negotiation Data Repository (NDR)

- New Frontiers, New Roleplays: Next Generation Teaching and Training

- Negotiating Transboundary Water Agreements

- Learning from Practice to Teach for Practice—Reflections From a Novel Training Series for International Climate Negotiators

- Insights From PON’s Great Negotiators and the American Secretaries of State Program

- Gender and Privilege in Negotiation

Remember Me This setting should only be used on your home or work computer.

Lost your password? Create a new password of your choice.

Copyright © 2024 Negotiation Daily. All rights reserved.

Negotiation And Conflict Management: Sick Leave Case Study

Negotiation And Conflict Management: Sick Leave Case Study.

The following text has been summarised and adapted from the following published case:

Kelly was trying to control her anger as she thought about her supervisor. She couldn’t understand why he was being so unreasonable. May be to him it was only a couple of days paid leave and not worth fighting over, but to her it meant the difference between being able to go on vacation for the long weekend or having to stay at home. She looked at her contract and the phone number of CLAIR on her desk. She wasn’t the only person in the office affected by this. She sat and thought about how she should proceed.

Kelly is 22 years old and has been working for the past six months at the Soto Board of Education office in Japan. This is her first job after graduating from university with a degree in Management and on the whole, she really enjoyed it. Kelly was born in Adelaide and had spent most of her life there. She came from a highly successful professional family. Both parents were lawyers and so she grew up with a strong sense of justice. Like her parents, Kelly was very confident, an extrovert and a definite Type A personality!

She had studied Japanese in high school and took some courses in Japanese as electives in the University. She therefore spoke and wrote the language quite well and had even been on a school exchange to Japan. She had enjoyed the time she spent there and always planned to return one day. During her final year at the university, Kelly heard some of her friends talking about the Japan exchange and teaching programme. She thought it would be a great way to make some money, revisit Japan and take a bit of time out before embarking upon her Management career.

The Japanese Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program

The origins of the JET programme can be traced back to 1982 when the Japanese Ministry of education initiated a project which led to hiring young westerners to work at the local boards of education as consultants to Japanese teachers of English in the public schools. The goal of the programme not only concerned English instruction but also focussed more broadly on internationalisation in education and sought to increase mutual understanding and improve friendly relations between the peoples of Japan and other western countries.

CLAIR, originally the Conference of Local Authorities for International Relations, was established in 1986. The organisation was responsible for implementing the JET program in conjunction with the Japanese ministries. CLAIR had the responsibility to;

• advise and liaise during the recruitment and selection of western candidates for the JET program • place participants • provide orientation to the western JET participants • guide local authorities and host institutions • take care of participant welfare and counselling • make arrangements for travel for the participants coming to Japan • publish materials • provide publicity for the program

Counselling system of the JET Program

1. Usually, any problems JET participants face during their stay in Japan would addressed by the host institution. If participants had complaints or a problem at work or in his or her private life, the JET could alert his or her supervisor, who would take up the matter and attempt to solve it. 2. If problems raised by JET participants could not be solved by the host institutions the issues could be addressed with CLAIR who would try to resolve grievances between the JET participant and the host institution. CLAIR employed a number of non-Japanese programme coordinators who would intervene on behalf of the JET participant in these cases. 3. At the highest level, there was also a special committee for counselling and training consisting of staff from CLAIR, relevant embassies, host institutions and the Japanese education department. The committee oversaw orientation, conferences, public welfare, and counselling. If necessary, it answered the questions and concerns of the JET participants where they were of a serious nature.

The Association for the Japan Exchange and Teaching is an independent self-supporting organisation created by the JET programme participants. Membership in AJET was also voluntary. AJET provided members with information about working and living in Japan and provided a support network for members at the local, regional and national levels. Many Japanese and JET participants themselves considered AJET to be the union of the JET programme participants.

Kelly’s Placement

Kelly was sent to Soto, a medium-sized city on the island of Shikoku. She found the area quite different from Osaka, where she had stayed the previous time she was in Japan. Soto was, in Kelly’s opinion, a small provincial town stuck in the middle of nowhere. She had enjoyed the activity and nightlife of Osaka but in Soto, there was not much to do with few entertainment options and only one cinema. Kelly very quickly developed a habit of going away on the weekends to tour different parts of the island and used her holidays to take advantage of visiting other parts of Japan that she might never again get a chance to see. However, Soto was at least a good place to improve her Japanese since not many people spoke English very well and only a few foreigners lived there.

Kelly worked at the Board of Education office three days a week and visited schools for two days to help with their English programmes. There were three other JET participants who worked in the same office. Mark 27, another Australian, Andrea 26 an American and Suzanne 25 from Great Britain. Like Kelly, Suzanne had been in Japan for only the past six months while Mark and Andrea had been working there for a year and a half. She was on good terms with the other JET participants in the office, although she was closest to Suzanne since they had both arrived in Japan at the same time and had met at their orientation in Tokyo.

Although Kelly had spent time in Japan before, this was the first time she had worked in a Japanese office. She had learned about Japanese work habits in a cross-cultural management class at university and was still surprised at how committed the Japanese were to their jobs. The working day began each morning at 8.30am with a staff meeting and officially ended each night at 5 p.m. Yet no one left the office before seven or eight o’clock. The Japanese came in on Saturdays, which Kelly thought was absurd since it left the employees with only one day a week to relax or spend time with their families. Kelly and the other JETs in the office had standard contracts given to them by CLAIR which stipulated hours, number of vacation days and number of days that could be taken in sick leave. The contract stated that the JET participants only worked from Monday to Friday until 5 p.m. and did not mention working on Saturdays. Neither Kelly, nor the other foreigners ever put in extra hours at the office nor were they ever asked to do so.

Mr Higashi was the JET participants’ supervisor in the office. At first, Kelly thought that he was very kind and helpful because he had picked her and Suzanne up from the airport and had arranged housing before they arrived in Japan. He even took the two women shopping to help them buy necessary items for bedding and dishes, so that they did not have to be without anything, even for one night.

Mr Higashi was born and had lived all his life in Soto. He was 54 years old and had been teaching high school English in and around Soto for more than 30 years. Two years ago, Mr Higashi was promoted to work as an adviser to all English teachers at the Soto Board of Education. This was a career making move that would put him on track to become a school principal. This new position at the Board of Education, made Mr Higashi, the direct supervisor over the foreign JET participants in the office, as well as making him responsible for their actions.

Mr Higashi found it very difficult to work with the foreign workers. Since they were hired on a one-year contract basis, renewable only to a maximum of three, he had already seen several come and go. He also considered it inconvenient that Japanese was not a requirement for the JET participants because since he was the only person in the office, who could speak English, he found that he wasted a lot of time working as an interpreter and helping the foreigners do simple everyday tasks like reading electric bills and opening a bank account. Despite this he did his best to treat the foreigners well and provide assistance as he would any other subordinate, by nurturing their careers and acting as a father figure. He felt he knew what was best for them. He was aware that his next promotion would depend to some extent, upon his own performance as a JET supervisor and how well he interacted and managed his subordinates, so he worked hard to be a good mentor. The problem was he often found them to be extremely impolite with little respect for his position. He felt increasingly annoyed with Suzanne and Kelly particularly.

Mr Higashi liked Kelly at first because she spoke Japanese well, had already spent time in Japan and seemed genuinely interested in the culture. Although she was the youngest of the four JET participants, he hoped that she would guide the others and assumed that she would not be the source of any problems for him. As time went by however he found her to be somewhat demanding, assertive and rather too inclined to animated conversations during working hours.

How the JET participants felt about Mr Higashi

At first, Mr Higashi seemed fine. All of the JETS sat in two rows with their desks next to each other, as they used to in school, with Mr Higashi’s desk facing them. The foreigners all agreed that Mr Higashi acted more like a father than a boss. He continually asked them how they were enjoying Japanese life and kept encouraging them to immerse themselves in Japanese culture and activities that Kelly and the other females felt was sexist. For example, he had left brochures on Kelly’s desk for courses in flower arranging and the tea ceremony and even one on Japanese cooking. At first, Kelly found this rather amusing, but she soon tired of it and started to get fed up with the constant pressure to sign up for Japanese culture classes. What she resented most was that Mr Higashi kept insisting she tried activities that were traditionally considered a woman’s domain. She didn’t have anything against flowers, but if she had been a man she knew that Mr Higashi would not have hassled her this much to fit in to Japanese society in quite this way. Kelly had been very active in sports back in Australia and bought herself a mountain bike when she arrived in Japan so that she could go for rides in the country. At Suzanne’s encouragement, Kelly also joined the local kendo club. She hoped that Mr Higashi would be satisfied that she was finally getting involved in something traditionally Japanese and leave her alone.

She noticed that there were no Japanese women who had been promoted to the same senior level as Mr Higashi within the Board of Education. The only women who worked there were young and single secretaries. Kelly was openly and vocally critical about what she perceived to be institutionalised sexism. It made her very angry but she noticed Mr Higashi did not approve of her remarks and would peer at her over his spectacles as though she was some sort of school girl.

Apart from the fact that Kelly viewed Mr Higashi as sexist and patronising, she didn’t think much of him as a supervisor. If Kelly or any of the other foreigners had a problem or a question about living in Japan, he would either ignore them or give them information that she later found out was incorrect. Andrea told Kelly that she stopped going to Mr Higashi when she had problems and instead consulted one of the women working in the office. Suzanne also found Mr Higashi totally exasperating. He was forever arranging projects and conferences for the JETS to participate in, and then changing his mind and cancelling at the last minute without bothering to tell them. He would also volunteer them all to work on special assignments over the holiday period and then get angry when they told him that they had made plans and were unable to go. Suzanne recalled that one week before the Christmas vacation, Mr Higashi announced that he had arranged for her to visit a junior high school. Suzanne informed him that while she would love to go, it was impossible since she had already booked time off and had arranged a holiday to Korea. Mr Higashi got angry and told her that he and the Board of Education would lose face if she didn’t attend. Suzanne told Mr Higashi that losing face would not have been an issue if he had told her about the visit in advance, so she could have prepared for it.

As a result, Suzanne lost all respect for Mr Higashi as a manager and continually challenged his authority. Whenever a problem arose, she was quick to remind him that things were very different and much ‘better’ in her country. Mark also had difficulties with Mr Higashi. Mark was not much of a team player but resented Mr Higashi constantly telling him what to do and he preferred to work on his own. He didn’t like Mr Higashi’s paternalistic attitude but he didn’t want to get involved with conversations with Kelly and Suzanne all the time about Mr Higashi. He didn’t need the hassle. He just wanted to be treated like a normal, capable employee and be given more free rein to do his work. As a show of his independence, Mark refused to join in any of the drinking meetings after work that involved males exclusively. But that was as far as it went. There were already too many people getting over emotional in the office and he didn’t want to be one of them.

The Japanese Opinion of the JET participants

The other Japanese employees in the office found it difficult to work with the JETs. As far as they were concerned, the JETs were never there long enough to become part of the group, it seemed just like after they got to know one, he or she left and was replaced by another. Another problem was that since the foreigners usually did not speak Japanese, communication with them was extremely frustrating. They also caused problems with Mr Higashi and were disrespectful. Mr Higashi was the boss and he would be so, long after Kellie, Mark and Suzanne had left.

Many of the other workers in the office also resented the fact that the JET workers were paid more than them and even Mr Higashi, despite the fact that they were far younger with much less experience. To make matters worse, these young foreigners were also hired to advise them how to do their jobs better. The Japanese employees did not consider the JETs to be very committed workers either. They never stayed past five o’clock on week days and never came to work on weekends, even though the rest of the office did. Mark never came to the bar in the evening with them either and seemed to lack commitment. The JETs also made it very clear that they had a contract that allowed them vacation days, and they made sure they used every single day. Japanese employees on the other hand, rarely ever made use of vacation time and knew that if they took holidays as frequently as the foreigners, they could return to find that their desks had been cleared!

The incident

Kelly woke up one Monday morning with a high fever and a sore throat. She rang Mr Higashi to let him know that she wouldn’t be coming in that day and possibly not the next either. Mr Higashi asked if she needed anything and told her to relax and take care of herself. But before he hung up, Mr Higashi told her that when she came back to the office, to make sure to bring in a doctor’s note. Kelly was annoyed. The last thing she wanted to do was to get out of bed and go to the clinic for a simple case of the flu. But as she was getting dressed, she thought she was being treated like a schoolgirl by being forced to bring in a note.

Two days later, Kelly returned to the office with a note from the physician in her hand. Mr Higashi informed her that Suzanne and Mark had also been sick and he appeared suspicious that the three of them had been sick at the same time and had commented that he knew that foreigners sometimes pretended to be sick in order to create longer weekends. Kelly was glad that she had gone to the doctor and got a note to prove that she really was sick.

Mr Higashi took the note without so much as looking at it and threw it onto a huge pile of incoming mail on his desk. He asked her if she was feeling better, and then went back to his work. At mid-morning, the accountant came over to Kelly’s desk and asked her to sign some papers. Kelly, reached for her pen and started to sign automatically until she noticed that she was signing for two days of paid leave and not sick leave. She pointed out the error to the accountant, who told her that there was no mistake. Kelly told the accountant to come back later and went over to speak to Mr Higashi. She was surprised to find that Mr Higashi said that there had been no mistake and that it was standard procedure in Japan. He said typical Japanese employees normally did not make use of their vacation time due to their great loyalty to the organisation. If an employee became sick, he or she often used paid vacation time first, out of consideration for employers.

Kelly responded that this was fine for Japanese employees, but since she was not Japanese, she preferred to do things the Australian way. Mr Higashi replied that since she was in Japan, maybe she should start doing things, the Japanese way. The next day, both Mark and Suzanne returned to the office only to find themselves in the same predicament as Kelly. Suzanne called Mr Higashi a lunatic and Mark chose to stop speaking to him altogether. Kelly was furious that they were being forced to waste two of their vacation days when their contracts clearly stated sick leave entitlements. She threw the JET contract on Mr Higashi’s desk and pointed out the sections that stipulated the number of sick days they were entitled to and demanded that he honour the contracts as written.

Mr Higashi looked extremely agitated and said that he had to go to a very important meeting and would discuss the situation later. The accountant reappeared with the papers for the three JETs to sign, but they all refused. Suzanne started to complain about Mr Higashi’s incompetence, while Mark complained about the Japanese style of management. Suzanne wanted to call AJET as she was a member and this was the kind of problem unions were supposed to handle. Kelly stared at the contract on her desk and said that they could take it to a higher level and involve CLAIR. One of the office staff urged her to avoid contacting CLAIR as people could lose face if it went that far. Nevertheless, Kelly opened her desk drawer and began looking for CLAIR’s phone number.

Case Study Questions

Identify the key influences that you believe have caused, influenced and exacerbated the conflict described in the case study. Support your argument with relevant literature?

1.0 Introduction:

Within an organisational circumference approaches cordiality between the employees and the management is the most elusive factor that helps in developing the organisational structure. Loyalty of an employee for the organisational operations, and cordiality of the employer for the employee juxtaposes. Dale-Olsen (2013) has affirmed that by maintaining this essential positioning the services to the targeted people of the society can be rendered. Having been in the age of intense globalization, the organisations appear to hire the foreign expert and experienced employees (Rugless and Taylor, 2011). This enables in performing the work for the organisation efficiently. The researcher is going to focus on some of the proficient approaches of managing the foreign employees by the employers in order to maintain the organisational working ethos. For this purpose the researcher is also going to focus on the particularly given case study where an employer of Japan has to face different inquisitive approaches in handling the foreign employees.

2.0 Brief Overview of the Case Scenario:

Kelly, working in Japan with JET, under the supervisation of Mr. Higashi who appears not to be so much effective in his approaches towards the foreign employees. Along with Kelly, Suzanna and Mark also work there to accompain her. Kelly had failed to come two days in the office because of fever. She informed Mr. Higashi who asked her to take rest. But he also asked to bring a doctor’s certificate as proof when she resumes. Kelly managed all the factors properly. However, the problem begins when after rejoining of Kelly after two days, Mr. Higashi said Suzanna and Mark were also on leave for these days and he suspected that they had taken the leave to enjoy their extended weekend. Therefore, they all would be awarded with non-paid leave. He insisted his accountant to make the papers signed from them. When they tried to approach Mr. Higashi and showed him the rule of giving sick leave in the contract, he tried to overlook them and stick to his points. This situation has brought an immense dilemma for all the three foreigners who feel quite wired and drab to work for JET anymore. At the same time, boasting and bossy attitude of Mr. Higashi has become a matter of headache for them. The employee and employer relationship, therefore, come standing before a big question in JET, especially for the foreign employees.

3.0 Critically Analyzing Case: Reasons, Points of Influences, Areas of Conflict

In this current case study it is seen that Kelly, Suzanna and Mark are working for JIT under Mr. Higashi as supervisor. It is natural that both of the parties feel quite hefty initially while keeping a good cordiality between them. Mr. Higashi although primarily had tried to become affluent in his approach to maintain proper relationship with the employees but it appears that his approaches were not proficiently taken by the employees. At the same time, the distance between the senior authority and lower employees could not have been avoided. Mr. Higashi from the first day appears not to be so much intrinsic towards the foreign employees. But as for fulfilling the necessities, he has to hire them. On the other hand, analyzing the case scenario it is clear that he had a little faith or belief on them (Hansson et al . 2008). Asking for the doctor’s note from Kelly on the date of joining however seems to be justified, but disclosing his doubt that Kelly had taken the leave to enjoy the extended weekend is in no way supportable. The fact is, as stated by Andersen (2010), making the employees doubted although is intrinsic, but disclosing that without having any justified information or document to prove it cannot be supported.

The approaches of Mr. Higashi in this case study appears to be quite absurd and disappointing. It can better be stated his supervising power is really weak and not efficient as well. First of all he does not seem to be ethical with his own employees. He initially asked Kelly to bring the medical certificate for giving her the paid leave on that specified day. But later he is seen to judge the case of Kelly from the same point of view Suzanna and Mark. When he was having doubt, he could have cross-checked it from that (Skatun, 2002). But despite doing that he directly accused three of them and forced to accept the non-paid leave. He even has refused to look at the agreement of medical leave that the foreign employees are liable to cherish. The decisive approach of Mr. Higashi is the primary matter of crating all the troubles and problems for all of these foreign workers. In no way the attitude of managing any incident seem to be affluent that influenced all the problems (Berkley and Watson, 2009).

At the same time, Mr. Higashi was barely familiar and appreciated among the foreign employees. Kelly although at the beginning of her working with JET seemed to have been fascinated by Mr. Higashi, but later she also refused to obey his order proficiently. He seemed to have arranged so many meetings with JETs and postpone them without letting the employees know even. The bossy attitude of Mr. Higashi has never been appreciated by the foreign employees ever. On the other hand, making the employees forced to work on the holidays although may seem to be successful to fulfill the predestined objectives of the organisation, but it deteriorate the management and employee relationship (Kuehn, 2012). For example Suzanne has been forced to work during the Christmas Eve holiday by Mr. Higashi and thereby she has to spoil her personal planning. Therefore, Mr. Higashi fails to acquire the appreciation of the employees. In order to bring them under control, he seems to have lost his own control over them and started becoming autocratic. This was not accepted by the employees.