You’re invited to the 2024 Hepatitis B Foundation Gala on April 5, 2024 in Warrington, PA. Details here .

Research & Programs

- Funding Opportunities

- College Internship Program

- High School Science Enrichment Program

- Hep B United Coalition

- Roadmap for a Cure

- Hep B Cure Campaign

- HepBStories

- Global Community Partnerships

- Preventing Mother to Child Transmission

- Community Advisory Board

- Global Resources

- News Archive

- Newly Diagnosed

- What is Hepatitis Delta?

- Facts and Figures

- Transmission

- Testing and Diagnosis

- Clinical Trials

- Find A Doctor

- Share Your Story

- What is Liver Cancer?

- Risk Factors

- Diagnosing Liver Cancer

- Staging of Liver Cancer

- Talking to Your Health Care Team

- Liver Cancer Centers

- HBV & Liver Cancer Connection

- Treating Liver Cancer

- Liver Cancer Drug Watch

- Follow Up Care

- Glossary of Terms

- CHIPO Overview

- Get Involved

- Member Organizations

- Upcoming Events

- B Informed Social Media Toolkit

- Find Your Why on World Hepatitis Day

Our Research Institute

Our research program is bringing hope through the work of scientists at the Baruch S. Blumberg Institute. We sponsor activities that help keep the national research focus on hepatitis B and promote innovative scientific exchange among academia, industry and government.

Baruch S. Blumberg Institute

The Baruch S. Blumberg Institute is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit research institute that was established in 2003 by the Hepatitis B Foundation to advance its research mission. The Blumberg Institute supports programs dedicated to drug discovery, biomarker discovery and translational biotechnology around common research themes such as chronic hepatitis, liver disease, and liver cancer in an environment conducive to interaction, collaboration and focus.

With more than 30 scientists, the Blumberg Institute may now be the largest group of nonprofit researchers working on hepatitis B in the world.

To learn more about the Baruch S. Blumberg Institute, visit www.blumberginstitute.org.

A comprehensive comparison of molecular and phenotypic profiles between hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected and non-HBV-infected hepatocellular carcinoma by multi-omics analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Druggability of Biopharmaceuticals and State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, School of Life Science and Technology, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China.

- 2 Biomedical Informatics Research Lab, School of Basic Medicine and Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China; Institute of Innovative Drug Discovery and Development, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China; Big Data Research Institute, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China.

- 3 Center for New Drug Safety Evaluation and Research, State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China.

- 4 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Druggability of Biopharmaceuticals and State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, School of Life Science and Technology, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 5 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Druggability of Biopharmaceuticals and State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, School of Life Science and Technology, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 6 Biomedical Informatics Research Lab, School of Basic Medicine and Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China; Institute of Innovative Drug Discovery and Development, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China; Big Data Research Institute, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 38513875

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2024.110831

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). An interesting question is how different are the molecular and phenotypic profiles between HBV-infected (HBV+) and non-HBV-infected (HBV-) HCCs? Based on the publicly available multi-omics data for HCC, including bulk and single-cell data, and the data we collected and sequenced, we performed a comprehensive comparison of molecular and phenotypic features between HBV+ and HBV- HCCs. Our analysis showed that compared to HBV- HCCs, HBV+ HCCs had significantly better clinical outcomes, higher degree of genomic instability, higher enrichment of DNA repair and immune-related pathways, lower enrichment of stromal and oncogenic signaling pathways, and better response to immunotherapy. Furthermore, in vitro experiments confirmed that HBV+ HCCs had higher immunity, PD-L1 expression and activation of DNA damage response pathways. This study may provide insights into the profiles of HBV+ and HBV- HCCs, and guide rational therapeutic interventions for HCC patients.

Keywords: Genomic instability; Hepatitis B virus infection; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Immunotherapy; Molecular and phenotypic profiles; Multi-omics data analysis.

Copyright © 2024. Published by Elsevier Inc.

Hepatitis Disease-Specific Research

NIAID supports and conducts research on each of the five known hepatitis viruses—A, B, C, D, and E. During the past 60 years, NIAID-supported investigators have been involved in many important breakthroughs in hepatitis research, including the discovery of the hepatitis A and E viruses, the development of one of the first diagnostic tests for hepatitis A, and studies that led to the creation of the hepatitis A vaccine and laid the foundation for advanced development of a hepatitis E vaccine. Commensurate with the magnitude of the medical burdens imposed by these viruses, the greatest emphasis is placed on the study of hepatitis C and hepatitis B viruses, focusing on the immune response to infection, pathogenesis and development of novel therapeutics and vaccines.

Hepatitis B

Although a vaccine to prevent hepatitis B infection is available, hepatitis B-induced liver cirrhosis and liver cancer kill about 3,000 people in the United States and roughly 620,000 people worldwide each year.

The virus can be spread

- From mother to child during childbirth

- Through sex with an infected partner

- Through contact with the blood of an infected person

- By sharing needles, syringes, razors, or toothbrushes with an infected person

Co-infection with hepatitis B virus and HIV is common.

NIAID is working with researchers in academia and the pharmaceutical industry to screen hundreds of new drug compounds for potential antiviral activity against hepatitis B. The goal is to find new treatments that will work alone or in combination with current drugs to reduce or resolve chronic infections.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus can be spread

- Through contact with the blood of an infected individual, such as through sharing needles when injecting drugs

- By unsafe injection practices in healthcare facilities

- In mother-to-child transmission during childbirth

- Through sexual contact with an infected partner

NIAID supports studies, including research at five Hepatitis C Cooperative Research Centers across the country, that focus on the immune response to hepatitis C virus infection. Several newly developed drugs can now cure more than 95% of all treated patients. However, a vaccine to prevent hepatitis C is urgently needed. A large proportion of people do not know that they are infected and therefore continue to spread the virus. People who are cured also can be re-infected if re-exposed.

NIAID-supported researchers recently completed a Phase 1/2 clinical trial of an investigational vaccine to evaluate its safety, tolerability and efficacy in preventing chronic hepatitis C infection. Although the trial did not show that candidate vaccine to be effective, NIAID continues to support efforts to develop a hepatitis C vaccine. Additionally, NIAID researchers are looking for biomarkers that may help predict progression to hepatitis C-associated liver cancer.

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E virus is transmitted by ingestion of contaminated water or food, usually in areas where there is poor sanitation. Hepatitis E is rare in the United States but prevalent in south and central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

Although most people with hepatitis E recover from the infection, studies have found that pregnant women infected with hepatitis E virus during the second or third trimester can have a higher rates of mortality (10% to 30%) or miscarriage. Their babies face increased risk of poor health and birth defects. NIAID-funded researchers have suggested that micronutrient deficiencies may have a role in these outcomes. Hepatitis E can also cause serious illness in people with preexisting chronic liver disease resulting in hepatic failure and death. A vaccine against hepatitis E has been developed and licensed in China. NIAID has initiated a Phase I trial of this vaccine , to test its safety in healthy adults in the United States.

- UNC Chapel Hill

Hepatitis B Elimination in sub-Saharan Africa: Peyton Thompson Leads Kinshasa-based Research Team Paving the Way For Virus-Free Generations

March 25, 2024

By Kim Morris

As the World Health Organization pushes to eradicate the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) by 2030, preventing vertical transmission is key, says Peyton Thompson, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. But despite widespread availability of effective childhood vaccines, HBV remains endemic throughout sub-Saharan Africa, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

“Many of the pregnant individuals who are infected don’t have good access to healthcare, and a lot of them don’t even know they’re infected,” explained Dr. Thompson, a member of the Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Ecology Laboratory ( IDEEL ), a network of researchers based at the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases, focused on infectious disease prevention in low-resource settings. “Without elimination of the vertical transmission, it’s going to be impossible to eliminate Hepatitis B.”

Thompson is passionate about HBV prevention and steadily advancing research that will pave the way for virus-free generations in sub-Saharan Africa. Her work has already made an impact and is driving a united effort. In March 2021, the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination recognized her studies in a synthesis of research updates during an international meeting designed to coalesce a community of practice around HBV prevention.

This meeting highlighted Thompson’s 2018-2019 feasibility study with Jonathan Parr, MD, MPH and Marcel Yotebieng, MD, PhD, MPH, (Albert Einstein College of Medicine), leveraging a patient care infrastructure for HIV prevention of vertical transmission at two clinical sites in Kinshasa. Carried out by a team of Congolese collaborators, the study screened pregnant individuals for HBV infection during routine prenatal care registration. Those who tested positive and presented at a gestational age of 24 weeks or less were included in the study. Eligible pregnant individuals with a high viral load (≥200,000 IU/mL) were considered at high risk for vertical transmission and were started on Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate between 28 weeks and 32 weeks of gestation. Additionally, all HBV-exposed infants received a birth-dose of monovalent HBV vaccine within 24 hours of life. Funded by a Gillings School of Global Public Health Lab Innovation Award, the results showed HBV screening and treatment using the HIV care platforms could accelerate progress towards elimination.

Research Impacting Policy

Then, in early 2020, Thompson’s study team joined a group that approached the DRC’s Deputy Minister of Health to advocate for universal birth dose vaccination and to share study results, along with representatives from the World Health Organization, CDC, and other health organizations. Their efforts were successful. In 2023, the DRC Ministry of Health agreed to recommend that the birth-dose vaccination be integrated within the current Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) and HIV Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission Program.

“This was important because they began to make plans to introduce the birth dose vaccine, and this was in part because of advocacy by our larger research group,” explained Linda James, IDEEL’s Director of DRC Research Collaboration and Development.

“It was after that meeting that DRC health organizations began to synthesize research, citing papers published by Peyton. And it was really encouraging to see that they were reading what we have been able to do with our partners in DRC to move this work forward.”

After that, the National Program for Prevention of Viral Hepatitis (PNLHV) was created, and the Ministry of Public Health, Hygiene and Prevention based its recommendation to introduce birth-dose vaccine on many of the team’s studies.

The Current Project

Now Thompson’s work is building on all of her HBV research to date, to recommend a treatment plan that will prevent vertical transmission in a way that is both safe and easy.

“In the 2018-2019 feasibility study, we looked at specific criteria to know which women qualify for treatment in pregnancy, such as viral load, which is expensive and not accessible for anyone outside of a research context. Then, we asked, what if we just test and treat all positive individuals?”

“We write the grants and help with some of the logistics, but they are on the ground doing the work and making it happen. In addition, our new study would not have launched when it did without Linda being involved and locally managing everyday logistics.”

Thompson says the birth dose vaccine needs to be given within 24 hours of birth which means close coordination is needed between the study nurses and study participants. The study has three nurses and each is assigned to a health center, staying in close contact with healthcare workers and doctors on site.

“This is the first study of its kind in a sub-Saharan African setting, and WHO is changing their guidelines right now to advocate for treating more people and lowering the threshold for when people would be treated by viral load.”

A Network of IDEEL Collaborators

“The IDEEL Lab and the people that have come together on projects aren’t only from UNC, they include other universities and collaborators. Peyton’s projects are an example of this collaboration producing results,” said James.

All of the research goes back to early collaborations established by the late Steve Meshnick , Professor of Epidemiology at Gillings School of Global Public Health, and relationships he built with the DRC’s Ministry of Health. It was because of his successful mapping of malaria, using national survey samples, that ministry officials asked Meshnick to map hepatitis viruses to improve access to diagnostics and prevention/treatment options.

“Without Steve’s work, none of this would be happening. All of us with IDEEL have been mentored in some way by him. One of the first times I met with Steve and Jonathan Parr, we engaged with collaborator Marcel Yotebieng, who also trained under Steve and got his PhD at UNC. He had a research platform for HIV among pregnant individuals that we built upon for our HBV study.”

Jonathan Parr, MD, MPH, a founding member of IDEEL, also led early HBV research in the DRC, assisting with the country’s first country-wide health survey to study the spread of hepatitis C. After discovering approximately 1 percent of patients were infected with the virus, his team was asked to conduct a similar survey on Hepatitis B.

“ In my research, I like to take practical approaches to improving care, to understand local capacity and build around that,” Thompson said. “Sustainability is really key because we’re trying to build a system that better suits the people and can meet their needs.”

Researchers in the Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Ecology Lab (IDEEL) at the Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases are process driven investigators working in 20+ countries to improve basic understandings of pathogens. The applied nature of their work has a direct impact on the health and well-being of millions of individuals around the globe, while also having an immediate effect on health policies at all levels.

Filed Under:

More from Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases

- UNC Researchers Lead HPV Research and Global Cancer Scientific Session at the EUROGIN International Multidisciplinary HPV Congress in Stockholm

- IAMIGHID: Amy James Loftis

- Claire Karasek Joins Institute As ID Fellowship Coordinator

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- SPONSOR FEATURE Sponsor retains sole responsibility for the content of this article

Charting a new frontier in chronic hepatitis B research to improve lives worldwide

Produced by

Infectious diseases are one of the greatest threats to mankind – evolving, spreading and disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable people. Knowing this, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson (‘Janssen’) has an ambitious goal behind the work we do – to create a future where we can prevent the spread of infectious diseases and eliminate the burden that such diseases have on global health. We all witnessed the devastating impact that infectious diseases can have firsthand through the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has dominated news headlines and impacted our everyday lives for the past couple of years. But it’s crucial to remember that COVID-19 isn’t the only infectious disease affecting a significant population across the globe.

Towards a functional cure

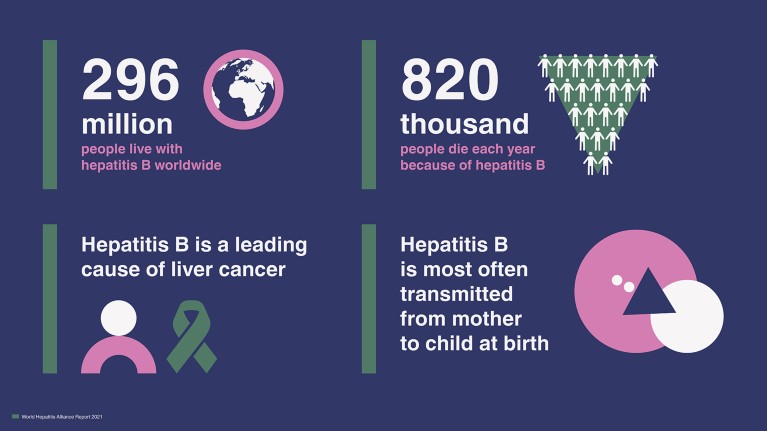

Today, nearly 300 million people worldwide live with chronic hepatitis B (CHB), the complications of which cause approximately one death every 30 seconds 1 . In addition to living with a potentially debilitating condition that often requires lifelong daily treatment, many people living with CHB are faced with an additional burden of stigma and discrimination associated with their disease status ( Fig. 1 ). Janssen recently had the privilege to partner with The World Hepatitis Alliance to sponsor a report that took a closer look at the realities faced by communities, families and individuals impacted by the burden and stigma of CHB across the globe.

Figure 1. Nearly 300 million individuals live with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) worldwide. Many people with HBV face stigma and discrimination in their daily lives. Credit: World Hepatitis Alliance.

Scientifically, advances in our understanding of hepatitis B virus (HBV) are helping to bring researchers closer to new solutions, namely a functional cure – that is, undetectable viral markers for a minimum of six months after a defined course of treatment – which could significantly improve long-term outcomes and health-related quality of life for people living with the virus. A functional cure requires that the infected subject maintains control of the infection through their immune system without continued use of anti-HBV medicines or vaccines.

While tremendous progress has been made to date, there is still more work to be done. Because the interface between HBV and the person hosting the virus (in particular, their immune system) is complicated, reaching a functional cure will be complex. Increasing functional cure rates of people living with HBV remains an important part of a comprehensive strategy to manage HBV more effectively.

As Janssen and other global researchers continue to advance the science towards our mutual end-goal of delivering a functional cure for those living with CHB, we cannot disregard the outstanding need to address the hurdles faced by people living with CHB and their families because of misconceptions, prejudice and outdated policy associated with the disease. Stigma and discrimination against those living with HBV can dramatically reduce one’s health-related quality of life, as well as one’s willingness to seek out and undergo treatment 2 . While patient education is a key component of helping link those with HBV to solutions, global collaboration across a wide breadth of stakeholders remains essential in achieving a meaningful difference.

The harmful effects of stigma and discrimination

Stigma can be thought of as a ‘mark’, either real or perceived, that negatively sets someone apart from others, causing feelings of exclusion and isolation 3 .

Health-related stigma is often rooted in fear and lack of understanding about infection, transmission, living with the disease, taking a daily medication or other factors leading to societal judgment and blame. Stigma becomes discrimination when an individual is actively treated unfairly or denied services or freedoms. For individuals living with CHB, this discrimination can come in the form of workplace or educational screening procedures, refusal of housing because of health status, and denial of healthcare services needed to effectively diagnose and manage their disease 4 . This stigma may impact not only the mental well-being and health-related quality of life of people living with CHB, but their loved ones and family as well. As the majority of people with HBV are infected at birth, stigma can affect individuals across their entire lifetime 4 , 5 . These challenges remain major – often unrecognized – barriers to successful prevention, diagnosis and treatment, and are largely the result of misinformation and fear.

Fortunately, as we work collectively towards achieving a functional cure to provide clinical benefit for patients living with CHB, our progress may also contribute to eliminating CHB-related stigma and discrimination.

Removing barriers to improve health outcomes

In 2021, Janssen sponsored a report 4 by the World Hepatitis Alliance to examine the burden of CHB globally and provide recommendations for addressing the ongoing barriers for patients and their families as a result of stigma and discrimination. The report, titled ‘ The impact of stigma and discrimination affecting people with hepatitis B ’, highlights human experiences to demonstrate the personal impact that stigma and discrimination can have on mental health, health-related quality of life and human rights. Importantly, the report identifies several key policy recommendations that can be taken now to dramatically improve millions of lives around the globe. This includes, but is not limited to, prioritizing accurate and non-stigmatizing hepatitis education for all healthcare professionals, improving access to equitable and affordable care, implementing and enforcing anti-discrimination laws, and increasing funding for HBV-specific programmes.

Policy- and decision-makers around the globe can play a critical part in advancing these recommendations, but collaboration is key when it comes to community solutions. By engaging a multitude of stakeholders such as those in public health, education, health systems and civil society, global and community leaders can make meaningful differences when it comes to eliminating stigma and discrimination, while we simultaneously work towards achieving a functional cure on the clinical side.

Hepatitis can’t wait

Through advances in science and continuing education, Janssen is committed to reducing the burden of disease and stigma associated with CHB. We applaud the efforts of scientists and leadership in all sectors, from private companies to government to major industry players, who are working tirelessly in pursuit of a functional cure for CHB, and potentially the elimination of stigma.

It is our belief that one day, our collective knowledge and progress towards this goal will result in a better future for millions of people around the world. By ensuring we don’t lose sight of the steps that can be taken as we progress in this shared journey, including identifying and implementing actions to address stigma and discrimination, we can begin to make that dream of a better tomorrow a reality today.

James Merson, Ph.D., Global Therapeutic

Area Head, Infectious Diseases,

Janssen Research & Development

260 E. Grand Avenue

South San Francisco, CA, 94080

United States

Hepatitis B Foundation (2018) http://www.hepb.org/assets/Uploads/Hepatitis-B-Fast-Facts-8-28-18-FINAL.pdf

Smith-Palmer, J. et al. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 11 , 95–107 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stangl, A. L. et al. BMC Med. 17 , 31 (2019).

World Hepatitis Alliance (2021) https://www.worldhepatitisalliance.org/stigma/

World Health Organization (2020) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

Download references

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Hepatitis B Information

Summary of 2023 screening and testing recommendations.

- All adults 18 and older at least once in their lifetime using a triple panel test

- Pregnant people during each pregnancy

- People who are at ongoing risk for exposure should be tested periodically

- Anyone who requests HBV testing should be tested

Hepatitis B is a vaccine-preventable liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Hepatitis B is spread when blood, semen, or other body fluids from a person infected with the virus enters the body of someone who is not infected. This can happen through sexual contact; sharing needles, syringes, or other drug-injection equipment; or during pregnancy or delivery. Not all people newly infected with HBV have symptoms, but for those that do, symptoms can include fatigue, poor appetite, stomach pain, nausea, and jaundice. For many people, hepatitis B is a short-term illness. For others, it can become a long-term, chronic infection that can lead to serious, even life-threatening health issues like liver disease or liver cancer. Age plays a role in whether hepatitis B will become chronic. The younger a person is when infected with the hepatitis B virus, the greater the chance of developing chronic infection. About 9 in 10 infants who become infected go on to develop life-long, chronic infection. The risk goes down as a child gets older. About one in three children who get infected before age 6 will develop chronic hepatitis B. By contrast, almost all children 6 years and older and adults infected with the hepatitis B virus recover completely and do not develop chronic infection.

The best way to prevent hepatitis B is to get vaccinated. All adults aged 18-59 should receive the vaccine and any adult who requests it may get the vaccine. All adults 18 years and older should get screened at least once in their lifetime.

- 2023 Screening and Testing Recommendations

- Testing and Vaccination

- Guidelines and Recommendations

- Schedules and Dosages

- Standing Orders

- Adults recommended to receive HepB vaccine

- Implementation Guidelines

- NAIIS Call to Action

- Overview and Statistics

- Transmission

- Screening and Testing

- Vaccination

- Education materials

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Prenatal Care

- Delivery Hospitals

- 2021 Surveillance Data for Hepatitis B

- Health care-Associated Outbreaks

- Guidelines and Forms

- Occupational Exposure and Non-occupational Exposure

- Perinatal Exposure

- Tools and Resources

- Major Guidelines

- Sources for IG and HBIG

- Education Resources for the Public

- CDC Materials and Links

- Overview of Viral Hepatitis

- Statistics & Surveillance

- Populations & Settings

- State and Local Partners & Grantees

- Policy, Programs, and Science

- Resource Center

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

What the Data Says About Pandemic School Closures, Four Years Later

The more time students spent in remote instruction, the further they fell behind. And, experts say, extended closures did little to stop the spread of Covid.

By Sarah Mervosh , Claire Cain Miller and Francesca Paris

Four years ago this month, schools nationwide began to shut down, igniting one of the most polarizing and partisan debates of the pandemic.

Some schools, often in Republican-led states and rural areas, reopened by fall 2020. Others, typically in large cities and states led by Democrats, would not fully reopen for another year.

A variety of data — about children’s academic outcomes and about the spread of Covid-19 — has accumulated in the time since. Today, there is broad acknowledgment among many public health and education experts that extended school closures did not significantly stop the spread of Covid, while the academic harms for children have been large and long-lasting.

While poverty and other factors also played a role, remote learning was a key driver of academic declines during the pandemic, research shows — a finding that held true across income levels.

Source: Fahle, Kane, Patterson, Reardon, Staiger and Stuart, “ School District and Community Factors Associated With Learning Loss During the COVID-19 Pandemic .” Score changes are measured from 2019 to 2022. In-person means a district offered traditional in-person learning, even if not all students were in-person.

“There’s fairly good consensus that, in general, as a society, we probably kept kids out of school longer than we should have,” said Dr. Sean O’Leary, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who helped write guidance for the American Academy of Pediatrics, which recommended in June 2020 that schools reopen with safety measures in place.

There were no easy decisions at the time. Officials had to weigh the risks of an emerging virus against the academic and mental health consequences of closing schools. And even schools that reopened quickly, by the fall of 2020, have seen lasting effects.

But as experts plan for the next public health emergency, whatever it may be, a growing body of research shows that pandemic school closures came at a steep cost to students.

The longer schools were closed, the more students fell behind.

At the state level, more time spent in remote or hybrid instruction in the 2020-21 school year was associated with larger drops in test scores, according to a New York Times analysis of school closure data and results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress , an authoritative exam administered to a national sample of fourth- and eighth-grade students.

At the school district level, that finding also holds, according to an analysis of test scores from third through eighth grade in thousands of U.S. districts, led by researchers at Stanford and Harvard. In districts where students spent most of the 2020-21 school year learning remotely, they fell more than half a grade behind in math on average, while in districts that spent most of the year in person they lost just over a third of a grade.

( A separate study of nearly 10,000 schools found similar results.)

Such losses can be hard to overcome, without significant interventions. The most recent test scores, from spring 2023, show that students, overall, are not caught up from their pandemic losses , with larger gaps remaining among students that lost the most ground to begin with. Students in districts that were remote or hybrid the longest — at least 90 percent of the 2020-21 school year — still had almost double the ground to make up compared with students in districts that allowed students back for most of the year.

Some time in person was better than no time.

As districts shifted toward in-person learning as the year went on, students that were offered a hybrid schedule (a few hours or days a week in person, with the rest online) did better, on average, than those in places where school was fully remote, but worse than those in places that had school fully in person.

Students in hybrid or remote learning, 2020-21

80% of students

Some schools return online, as Covid-19 cases surge. Vaccinations start for high-priority groups.

Teachers are eligible for the Covid vaccine in more than half of states.

Most districts end the year in-person or hybrid.

Source: Burbio audit of more than 1,200 school districts representing 47 percent of U.S. K-12 enrollment. Note: Learning mode was defined based on the most in-person option available to students.

Income and family background also made a big difference.

A second factor associated with academic declines during the pandemic was a community’s poverty level. Comparing districts with similar remote learning policies, poorer districts had steeper losses.

But in-person learning still mattered: Looking at districts with similar poverty levels, remote learning was associated with greater declines.

A community’s poverty rate and the length of school closures had a “roughly equal” effect on student outcomes, said Sean F. Reardon, a professor of poverty and inequality in education at Stanford, who led a district-level analysis with Thomas J. Kane, an economist at Harvard.

Score changes are measured from 2019 to 2022. Poorest and richest are the top and bottom 20% of districts by percent of students on free/reduced lunch. Mostly in-person and mostly remote are districts that offered traditional in-person learning for more than 90 percent or less than 10 percent of the 2020-21 year.

But the combination — poverty and remote learning — was particularly harmful. For each week spent remote, students in poor districts experienced steeper losses in math than peers in richer districts.

That is notable, because poor districts were also more likely to stay remote for longer .

Some of the country’s largest poor districts are in Democratic-leaning cities that took a more cautious approach to the virus. Poor areas, and Black and Hispanic communities , also suffered higher Covid death rates, making many families and teachers in those districts hesitant to return.

“We wanted to survive,” said Sarah Carpenter, the executive director of Memphis Lift, a parent advocacy group in Memphis, where schools were closed until spring 2021 .

“But I also think, man, looking back, I wish our kids could have gone back to school much quicker,” she added, citing the academic effects.

Other things were also associated with worse student outcomes, including increased anxiety and depression among adults in children’s lives, and the overall restriction of social activity in a community, according to the Stanford and Harvard research .

Even short closures had long-term consequences for children.

While being in school was on average better for academic outcomes, it wasn’t a guarantee. Some districts that opened early, like those in Cherokee County, Ga., a suburb of Atlanta, and Hanover County, Va., lost significant learning and remain behind.

At the same time, many schools are seeing more anxiety and behavioral outbursts among students. And chronic absenteeism from school has surged across demographic groups .

These are signs, experts say, that even short-term closures, and the pandemic more broadly, had lasting effects on the culture of education.

“There was almost, in the Covid era, a sense of, ‘We give up, we’re just trying to keep body and soul together,’ and I think that was corrosive to the higher expectations of schools,” said Margaret Spellings, an education secretary under President George W. Bush who is now chief executive of the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Closing schools did not appear to significantly slow Covid’s spread.

Perhaps the biggest question that hung over school reopenings: Was it safe?

That was largely unknown in the spring of 2020, when schools first shut down. But several experts said that had changed by the fall of 2020, when there were initial signs that children were less likely to become seriously ill, and growing evidence from Europe and parts of the United States that opening schools, with safety measures, did not lead to significantly more transmission.

“Infectious disease leaders have generally agreed that school closures were not an important strategy in stemming the spread of Covid,” said Dr. Jeanne Noble, who directed the Covid response at the U.C.S.F. Parnassus emergency department.

Politically, though, there remains some disagreement about when, exactly, it was safe to reopen school.

Republican governors who pushed to open schools sooner have claimed credit for their approach, while Democrats and teachers’ unions have emphasized their commitment to safety and their investment in helping students recover.

“I do believe it was the right decision,” said Jerry T. Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, which resisted returning to school in person over concerns about the availability of vaccines and poor ventilation in school buildings. Philadelphia schools waited to partially reopen until the spring of 2021 , a decision Mr. Jordan believes saved lives.

“It doesn’t matter what is going on in the building and how much people are learning if people are getting the virus and running the potential of dying,” he said.

Pandemic school closures offer lessons for the future.

Though the next health crisis may have different particulars, with different risk calculations, the consequences of closing schools are now well established, experts say.

In the future, infectious disease experts said, they hoped decisions would be guided more by epidemiological data as it emerged, taking into account the trade-offs.

“Could we have used data to better guide our decision making? Yes,” said Dr. Uzma N. Hasan, division chief of pediatric infectious diseases at RWJBarnabas Health in Livingston, N.J. “Fear should not guide our decision making.”

Source: Fahle, Kane, Patterson, Reardon, Staiger and Stuart, “ School District and Community Factors Associated With Learning Loss During the Covid-19 Pandemic. ”

The study used estimates of learning loss from the Stanford Education Data Archive . For closure lengths, the study averaged district-level estimates of time spent in remote and hybrid learning compiled by the Covid-19 School Data Hub (C.S.D.H.) and American Enterprise Institute (A.E.I.) . The A.E.I. data defines remote status by whether there was an in-person or hybrid option, even if some students chose to remain virtual. In the C.S.D.H. data set, districts are defined as remote if “all or most” students were virtual.

An earlier version of this article misstated a job description of Dr. Jeanne Noble. She directed the Covid response at the U.C.S.F. Parnassus emergency department. She did not direct the Covid response for the University of California, San Francisco health system.

How we handle corrections

Sarah Mervosh covers education for The Times, focusing on K-12 schools. More about Sarah Mervosh

Claire Cain Miller writes about gender, families and the future of work for The Upshot. She joined The Times in 2008 and was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for public service for reporting on workplace sexual harassment issues. More about Claire Cain Miller

Francesca Paris is a Times reporter working with data and graphics for The Upshot. More about Francesca Paris

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Hepatitis b.

Nishant Tripathi ; Omar Y. Mousa .

Affiliations

Last Update: July 9, 2023 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Hepatitis B infection is a serious global healthcare problem. Often transmitted via body fluids like blood, semen, and vaginal secretions, the hepatitis B virus can cause liver injury. After infection with the hepatitis B virus, the majority of adults are able to clear the infection. Patients can present with acute symptomatic disease or have an asymptomatic disease that is identified during screening for the hepatitis B virus. This article focuses on identifying who is at risk of hepatitis B, and clinical evaluation and management of patients with hepatitis B by an interdisciplinary team. It also focuses on preventive measures.

- Describe the epidemiology of hepatitis B.

- Outline the common blood tests for the diagnosis of hepatitis B infection.

- Review the complications of hepatitis B infection.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and communication amongst the interdisciplinary teams to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by hepatitis B.

- Introduction

Hepatitis B viral infection is a serious global healthcare problem. It is a potentially life-threatening liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). It is often transmitted via body fluids like blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. The majority (more than 95%) of immunocompetent adults infected with HBV can clear the infection spontaneously. Patients can present with acute symptomatic disease or have an asymptomatic infection that is identified during screening for HBV. The clinical manifestations of HBV infection vary in both acute and chronic diseases. During the acute infection, patients can have subclinical or anicteric hepatitis, icteric hepatitis, or less commonly fulminant hepatitis. In chronic infection, patients can have an asymptomatic carrier state, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Initial symptoms are nonspecific and may include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and jaundice. In cases of severe liver damage, patients can develop jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to esophageal varices, coagulopathy, or infections. Diagnosis is based on serologic blood tests in patients with suspected signs and symptoms and associated risk factors for viral hepatitis. This will be discussed in more detail below.

Transmission of hepatitis B involves the transfer of the virus from infected people to non-immune people in various ways. Major modes of transmission for hepatitis B are as follows:

1. Horizontal transmission: It involves the transmission of hepatitis B through sexual contact or mucosal surface contact. Unprotected sex and injection drug use are major modes of transmission in low to intermediate prevalence areas. [1]

2. Vertical transmission: Vertical transmission involves the maternal-to-newborn perinatal transmission of the virus. [2] It is the predominant mode of transmission in high-prevalence areas.

Sexual contact includes unprotected intercourse (vaginal, oral, or anal) and mucosal contact involves any contact involving an infected patient’s saliva, vaginal secretion, semen, and blood.

Prevalence areas are based on the percentage of the population with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity with greater than or equal to 8% representing high prevalence areas, 2-7% representing low to intermediate prevalence areas, and less than 2% representing low prevalence areas. [3]

- Epidemiology

HBV infection has the potential for progression to a chronic state and thus presents as a global public health threat for its associated morbidity and mortality. While hepatitis B vaccines are available, limited access to healthcare and lack of proper health education contributes to the increasing global prevalence of hepatitis B. Lower incidence of hepatitis B in the United States compared to Asia and Africa is due to better access to healthcare and better use of vaccinations and other preventive measures.

U.S. Statistics

- Around 60,000 new cases of HBV infection annually [4]

- 2 million or more people with chronic hepatitis B infection [4]

- Prevalence is higher in black, Hispanic, and Asian populations compared to whites [5]

- Prevalence is lower in people less than 12 years of age born in the U.S.

- Accounts for 5% to 10% of chronic end-stage liver disease, and 10% to 15% of cases of hepatocellular cancer

- Causes 5000 deaths annually

Worldwide Statistics

- 350-400 million of the world population has chronic hepatitis B. [6]

- The following population is known to have a higher prevalence: Asian Pacific Islanders, Alaskan Eskimos, and Australian aborigines. [6]

- The following geographic regions have higher prevalence: the Indian sub-continent, sub-Saharan Africa, and central Asia.

- The prevalence of hepatitis B is reduced after the initiation of the hepatitis B vaccination program.

- 10 genotypes (A-J) of hepatitis B have been identified. [7]

High-risk groups for HBV infection include intravenous drug users, infants born to infected mothers, males who have sexual intercourse with other males, hemodialysis patients (and workers), healthcare workers, household contacts of known patients with chronic HBV. A majority of the global HBV disease burden is primarily through vertical transmission.

- Pathophysiology

Hepatitis B virus is transmitted via percutaneous inoculation or through mucosal exposure with infectious bodily fluids. Oral-fecal transmission is possible but considerably rare. The incubation period of HBV infection is typically between 30 and 180 days, and while recovery is common in immunocompetent patients, a small percentage can progress to a chronic state, serologically defined as the presence of HBsAg for greater than six months. HBsAg is transmitted via blood contact or body secretions, and the risk of acquiring hepatitis B is considerably higher in individuals with close contact with HBsAg-positive patients.

The pathogenesis of liver disease in HBV infection is mainly immune-mediated, and in some circumstances, HBV can cause direct cytotoxic injury to the liver. HBsAg and other nucleocapsid proteins that are present on cell membranes promote T cells-induced cellular lysis of HBV-infected cells. Cytotoxic T cell response to HBV-infected hepatocytes is relatively ineffective; a significant majority of HBV DNA is cleared from the hepatic system prior to maximal T cell infiltration, suggesting that the immune response is likely more robust in the early stages of infection. The immune response may not be the sole etiology behind hepatic injury in hepatitis B patients. Hepatitis B-associated injury is also seen in post-liver transplant patients with hepatitis B that are on immunosuppressant therapy. The histological pattern that follows from this infection is termed fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis and is thought to be associated with an overwhelming exposure to HBsAg. This lends credence to the idea that hepatitis B may possess pathogenicity regardless of the immune system’s response. [8]

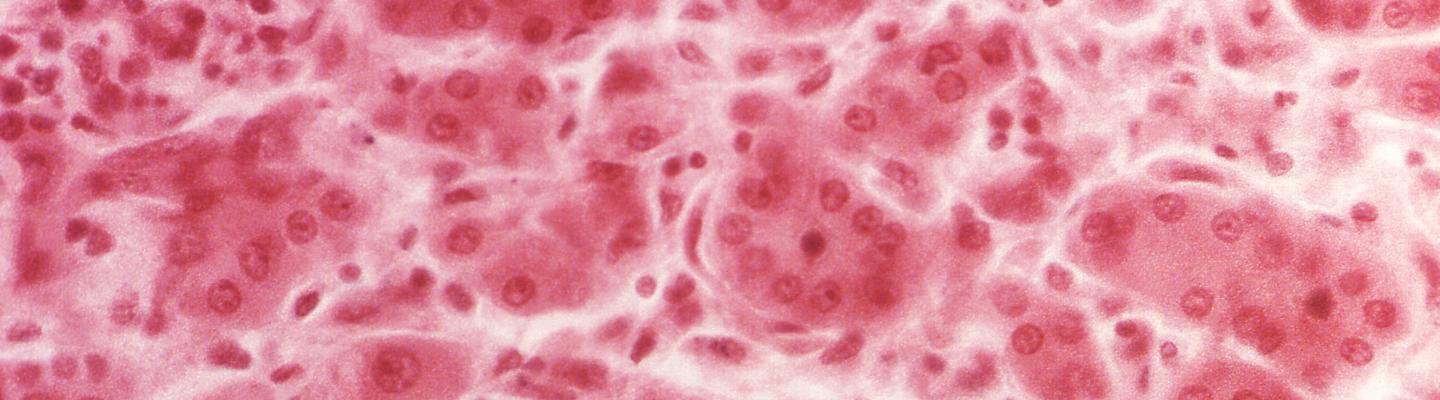

- Histopathology

Acute Hepatitis B Infection: Histologic findings include "lobular disarray, ballooning degeneration, multiple apoptotic bodies, Kupffer cell activation, and lymphocyte-predominant lobular and portal inflammation. [9]

Chronic Hepatitis B Infection: Lymphocyte-predominant portal inflammation with interface hepatitis and spotty lobular inflammation. [9]

- History and Physical

Patients infected with HBV could be asymptomatic initially and, depending on the particular genotype, might not be symptomatic throughout the infected state. In these particular cases, careful history taking is important to establish a diagnosis. However, when symptomatic from acute HBV infection, patients can present with serum sickness-like syndrome manifested as fever, skin rash, arthralgia, and arthritis. This syndrome usually subsides with the onset of jaundice. Patients may also have fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, and anorexia.

History taking should emphasize the social history, including sexual practices (e.g., unprotected, same-sex, etc.), illicit drug use, profession (e.g., healthcare worker, sex worker), and living arrangements (i.e., within the same household as a patient with HBV infection). Patients in high-risk groups (i.e., healthcare workers, IV substance abuse patients, etc.) or those from highly endemic areas may warrant testing. Those with certain mental illnesses like bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or manic disorder are at an increased risk for contracting HBV infection during manic states within which one may participate in risky sexual behaviors, including unprotected sex.

Physical examination should also assess for stigmata of chronic liver disease, including jaundice, ascites, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, palmar erythema, Dupuytren contractures, spider nevi, gynecomastia, caput medusa, and hepatic encephalopathy which suggests portal hypertension and cirrhosis.

Extrahepatic manifestations include polyarteritis nodosa and glomerular disease (membranous nephropathy and, less often, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis). Aplastic anemia has also been described.

Diagnosis of Hepatitis B is based on proper history taking, physical examination, laboratory works, and imaging.

Initial symptoms are nonspecific and can include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, clay-colored stool, and jaundice. In cases of severe liver damage, advanced findings specific to liver damage are common and can include hepatic encephalopathy, confusion, coma, ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, coagulopathy, or infections. In cases of chronic hepatitis B, patients can have a chronic inactive infection, or they can develop findings of acute hepatitis known as chronic active hepatitis.

The diagnosis of hepatitis B relies on the appropriate history/physical and evaluation of serum or viral biomarkers. Viral serology of hepatitis B is usually detectable 1-12 weeks after initial infection with the primary viral marker being hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). The presence of HBsAg rarely persists beyond 6 months after infection and typically precedes detectable quantities of the corresponding antibody to surface antigen (Anti-HBsAg). The period of time between the disappearance of HBsAg and the appearance of Anti-HBsAg is termed “the window period” or “serological gap.” During the window period, other viral serology could also be undetectable. HBsAg is the first virological marker to be detected thanks to its exposure on the viral surface and is indicative of an acute infection. Immune-mediated destruction of the nucleocapsid allows exposure of core antigen (HBcAg) or e antigen (HBeAg) with subsequent antibody development. Liver enzymes are typically elevated within the latter part of the replicative phase on infection thanks to active inflammatory processes, otherwise, liver transaminases could also be within their reference ranges. Hence, liver transaminases should not be a sole guide to diagnosing suspected hepatitis B infection.

The presence of antibodies to HBsAg indicates immunized status while the presence of antibodies to HBeAg refers to a possible chronic infection state. Seroconversion refers to the transition between an acute, immune-active phase to an inactive carrier state and is marked by the spontaneous development of antibodies to HBeAg. Earlier seroconversion has been related to more favorable outcomes while later seroconversion, in conjunction with recurrent bouts of reactivation and remission, is more liable to complications like liver cirrhosis, thus resulting in poorer outcomes. [10] The persistence of serum HBsAg for a duration of 6 months or greater delineates acute hepatitis B infection from chronic hepatitis B infection. Following groups of people should be screened for hepatitis B: [3]

- Persons born in high or intermediate endemic areas (HBsAg prevalence of greater than or equal to 2%). African countries, countries from North, Southeast, and East Asia. All countries from Australia and South Pacific (except for Australia and New Zealand). All countries from the Middle East (except for Israel and Cyprus). All countries from Eastern Europe (except for Hungary), Western Europe (Spain, Malta, and the indigenous population of Greenland), North America (Alaskan natives and indigenous populations of Northern Canada), Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. South America (Ecuador, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, and Amazonian areas). Caribbean (Antigua, Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Turks and Caicos Islands).

- The unvaccinated U.S. citizens whose parents were born in high prevalence areas.

- History of illicit intravenous drug use.

- Men who have sex with men.

- Persons on immunosuppressive therapy.

- Persons with elevated ALT or AST of unknown origin.

- Blood, plasma, organ, tissues, or semen donors.

- Persons with end-stage renal disease.

- All pregnant women and infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers.

- Persons with chronic liver disease and HIV.

- Close contacts of HBsAg-positive persons, such as household, sexual, or needle-sharing.

- Persons with more than one sexual partner in the last six months.

- Persons requesting evaluation or treatment for sexually transmitted infections.

- Health care workers or public safety workers who are at risk for occupational exposure to blood or blood-contaminated body fluids.

- Residents and staff at facilities for developmentally disabled persons.

- Travelers to countries with an intermediate or high prevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection.

- Correctional facilities inmates.

- 19-59-year-old persons with diabetes who have not been vaccinated for Hepatitis B.

- Persons who are the source of blood or body fluid exposures that might require post-exposure prophylaxis.

Interpretation of Serologic Markers

Following serologic markers are often tested: Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibody to Hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), Hepatitis B core Ab (Anti-HBc) IgM, Hepatitis B core Ab (Anti-HBc) IgG, Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and Hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe). [10]

HBsAg: Acute infection (less than 6 months) or chronic infection (more than 6 months).

Anti-HBs: Recovery from acute infection or immunity from vaccination.

HBeAg: Mostly associated with high viral load.

Anti-HBe: Low replicative phase.

Anti-HBc IgM: Acute infection, an only marker present in the window period, can be present during exacerbation of chronic infection.

Anti-HBc IgG: Exposure to infection, chronic infection (if present along with HBsAg), recovery from acute infection (if present with anti-HBs), if isolated presence, may represent occult infection.

Other markers are: Hepatitis B viral DNA is for detection of viral load. Hepatitis B genotype provides input about disease progression and response to interferons. [11]

- Treatment / Management

Preventive measures constitute a major component of the management of hepatitis B. As of 2019, hepatitis B vaccines available in the United States are categorized into either single-antigen hepatitis B vaccines or combination vaccines.

Acute hepatitis B infection is self cleared in 95% of healthy adults. Management is supportive in a majority of patients. Patients with severe acute disease (2 of the 3: bilirubin more than 10 mg/dl, INR more than 1.6 and hepatic encephalopathy) and protracted acute severe disease (total bilirubin more than 3 mg/dl or direct bilirubin more than 1.5 mg/dl, INR more than 1.5, hepatic encephalopathy, or ascites) need antiviral treatment.

Management of chronic hepatitis B should include identification of HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis D coinfection, hepatitis B virus replication status, and severity of the disease. [10] The severity of the disease is based on clinical assessment, blood counts, liver enzymes, and liver histology. [10] While non-invasive tests are useful (blood test, imaging to measure liver stiffness) for chronic hepatitis B with normal alanine transferase, for patients with elevated or fluctuating alanine transferase, liver biopsy is necessary to identify if they need antiviral treatment. [10]

FDA-approved medications for chronic hepatitis B include interferons (peginterferon alfa-2a, interferon alfa-2b), nucleoside analogs (entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine), and nucleotide analogs (adefovir, tenofovir). Entecavir and tenofovir are preferred for acute HBV infection if treatment is warranted, due to their relatively higher barrier to resistance. Entecavir combination drugs have been developed. However, a 2018 meta-analysis based on 24 studies involved with entecavir polytherapy vs entecavir monotherapy determined that entecavir combination drugs were no more effective than entecavir monotherapy. [12] Vertical transmission of hepatitis B remains a significant cause of the global HBV burden. In a 2015 prospective, multicenter trial, administration of tenofovir in HBsAg-positive and/or HBeAg-positive mothers demonstrated a benefit in reducing ALT levels in mothers and decreasing infant HBsAg levels at 6 months postpartum. [13] Major drawbacks for this study, however, include a relatively small sample size (n=118) and the lack of a placebo-based control group. Oral nucleos(t)ide therapy has been shown to suppress viral replication and thus decrease the viral burden. Lamivudine was the first effective agent to successfully used to suppress viral counts but was associated with high drug resistance. [14] A 2014 clinical trial comparing entecavir vs lamivudine in chronic B hepatitis reported better virological response in the entecavir group compared to the lamivudine group. [15] The 2013 GAHB trial was a placebo-controlled, double-blind study that compared lamivudine with a placebo. HBsAg clearance was achieved in a majority of patients with lamivudine therapy but the overall strength of the study was weakened by low recruitment numbers (n = 35). [16] For patients in the immune-tolerant phase of hepatitis B infection, a stage marked by normal liver transaminases and HBV DNA, antiviral medications were not recommended. A randomized controlled study showed suboptimal control of viral burden, likely secondary to high circulating levels of HBV DNA. [17] Regarding monotherapy versus combined therapy, there have been several limited studies addressing this issue. In the 2018 POTENT study, there was no demonstrated difference between monotherapy versus sequential therapy although there was insufficient data for statistical significance for HBsAg seroconversion. [18]

The counseling of patients on the prevention of transmission is extremely valuable. Lifestyle modifications include reducing intake of agents with potential for liver damage such as alcohol, hepatotoxic medications, herbal medications, and herbal supplements.

The goals of antiviral therapy are: [10]

- Suppression of hepatitis B virus replication

- Reduction of liver inflammation

- Prevention of progression to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

Appropriate treatment response is indicated by the following findings: [10]

- Blood tests: normalization of ALT

- Undetectable hepatitis B viral DNA

- Loss of HBsAg and HBeAg with seroconversion to anti-HBs and anti-HBe

- Reduced inflammation on liver biopsy with no worsening of fibrosis

Surgical intervention for hepatitis B is only indicated for fulminant liver disease requiring transplantation.

- Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for hepatitis B infection is broad due to the presence of non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Other etiologies of hepatitis (i.e., hepatitis A, hepatitis C, hepatitis E, alcoholic hepatitis, and autoimmune hepatitis) should be considered in conjunction with appropriate history taking and pertinent laboratory investigation.

Iron overload (hemochromatosis) can be associated with abdominal tenderness and abnormal liver transaminase levels. Pertinent findings that favor a diagnosis of hemochromatosis compared to hepatitis B include diffuse skin discoloration (bronze diabetes) and impaired glucose tolerance.

Wilson disease is a disease of excessive copper accumulation. It is associated with psychiatric disturbances due to copper accumulation in the basal ganglia. Kayser-Fleischer rings are pathognomonic for Wilson disease but are not completely sensitive (requires an expert ophthalmologist to confirm this finding). Laboratory evaluation that favors a diagnosis of Wilson disease includes low serum ceruloplasmin levels and elevated urinary copper, and if abnormal, requires further evaluation by a hepatologist.

- Alcoholic hepatitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Drug-induced liver injury

- Hemochromatosis

- Hepatitis A

- Hepatitis C

- Hepatitis D

- Hepatitis E

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Wilson disease

Acute HBV infection can be treated symptomatically and in immunocompetent patients, can spontaneously resolve. Those that progress to the chronic state, however, are at increased risk for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhosis, or fulminant liver failure. The likelihood of risk is dependent on the particular genotype, and the method of transmission as vertical transmission has a higher risk of long-term complications compared to horizontal transmission cases.

- Complications

Unlike hepatitis A and hepatitis E, in which there is no chronic state, HBV infection has the potential for the development of a chronic state. Chronic hepatitis B predisposes a patient to the development of portal hypertension, cirrhosis, and its complications or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). As such, patients with HBV infection should be monitored closely, and a referral to a specialist is highly recommended.Fulminant liver failure from HBV infection requires an emergent liver transplant evaluation at a liver transplant center.

- Consultations

Hepatitis B management ideally involves interprofessional collaboration. Primary care, gastroenterology, hepatology, infectious disease, liver transplant, and palliative care services are among the different services involved.

- Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education remains one of the most important components in preventative measures regarding HBV infection.

Education should be provided to expecting parents (particularly those from highly endemic regions) about the importance of vaccination and to clarify erroneous beliefs about vaccinations.Patient education should also include counseling about the avoidance of risky behaviors that predispose an individual to be infected, including promiscuous sexual activity or intravenous drug abuse. They should also be advised not to share items such as shaving razors, toothbrushes, or hair combs due to possible transmission via mucosal contact or through microtrauma to protective barriers.

- Pearls and Other Issues

Hepatitis D (a member of the delta virus family) has been long associated with HBV infections and cannot exert pathological influence without the presence of HBV infection. Two forms of infection exist; coinfection (acquired at the same time) and superinfection (hepatitis D infection in a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection). Superinfection tends to be more severe than coinfection. Due to the preexisting hepatitis B infection, anti-HBcAg IgM is undetectable in superinfection states but can be noted in coinfection.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As hepatitis B infection is highly transmissible via accidental needlesticks, healthcare providers involved in taking care of a patient with HBV should exercise caution and practice proper preventative measures such as vaccination. Patient education should also include counseling about HBV transmission. The interprofessional team's role is crucial in ensuring the best patient outcomes.

The vaccination rate is low in many developing countries, and the majority of patients are undiagnosed. Educational programs and improved awareness among the general public and healthcare providers are necessary to improve the identification of the patients, reduce transmission of the disease, and reduce the complications of hepatitis B infection.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Nishant Tripathi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Omar Mousa declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Tripathi N, Mousa OY. Hepatitis B. [Updated 2023 Jul 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standards. [StatPearls. 2024] OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standards. Denault D, Gardner H. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- China's efforts to shed its title of "Leader in liver disease". [Drug Discov Ther. 2007] China's efforts to shed its title of "Leader in liver disease". Li X, Xu WF. Drug Discov Ther. 2007 Oct; 1(2):84-5.

- Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in adults with emphasis on the occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. [J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000] Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in adults with emphasis on the occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Chu CM. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000 May; 15 Suppl:E25-30.

- Review Pharmacological interventions for acute hepatitis B infection: an attempted network meta-analysis. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017] Review Pharmacological interventions for acute hepatitis B infection: an attempted network meta-analysis. Mantzoukis K, Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, Buzzetti E, Thorburn D, Davidson BR, Tsochatzis E, Gurusamy KS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar 21; 3(3):CD011645. Epub 2017 Mar 21.

- Review Clinical aspects of hepatitis B virus infection. [Lancet. 1993] Review Clinical aspects of hepatitis B virus infection. Wright TL, Lau JY. Lancet. 1993 Nov 27; 342(8883):1340-4.

Recent Activity

- Hepatitis B - StatPearls Hepatitis B - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Research Highlights 22 Mar 2024 Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. P: 1. ... Vaccination is a key intervention for the elimination of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV ...

The National Institutes of Health has updated its Strategic Plan for NIH Research to Cure Hepatitis B, a roadmap for ending the hepatitis B epidemic, focused on developing a cure as well as improved strategies for vaccination, screening and follow-up care. The revised plan incorporates lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and recent advances in technology.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem, with an estimated 296 million people chronically infected and 820 000 deaths worldwide in 2019. Diagnosis of HBV infection requires serological testing for HBsAg and for acute infection additional testing for IgM hepatitis B core antibody (IgM anti-HBc, for the window period when neither HBsAg nor anti-HBs is detected).

INTRODUCTION. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has infected humans for at least the past 40000 years[] and is the 10 th leading global cause of death[].HBV is the only DNA-based hepatotropic virus that exerts many adverse effects on the infected cells leading to necroinflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis[].The world health organization (WHO), in 2015 has estimated 257 million people infected with ...

Abstract. Hepatitis B virus infection affects over 250 million chronic carriers, causing more than 800,000 deaths annually, although a safe and effective vaccine is available. Currently used antiviral agents, pegylated interferon and nucleos (t)ide analogues, have major drawbacks and fail to completely eradicate the virus from infected cells.

Background: The hepatitis B virus (HBV) affects an estimated 290 million individuals worldwide and is responsible for approximately 900 000 deaths annually, mostly from complications of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Although current treatment is effective at preventing complications of chronic hepatitis B, it is not curative, and often must be administered long term.

Tu T, Block JM, Wang S, Cohen C, Douglas MW (2020). The lived experience of chronic hepatitis B: a broader view of its impacts and why we need a cure. Viruses Freeland C, Bodor S, Perera U, Cohen C Barriers to Hepatitis B Screening and Prevention for African Immigrant Populations in the United States: A Qualitative Study.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection impacts an estimated 257-291 million people globally. The current approach to treatment for chronic HBV infection is complex, reflecting a risk:benefit approach driven by the lack of an effective curative regimen. ... 2 Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, North Carolina 27701, USA. 3 Department of ...

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. ... Recent advances in the research of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiologic and molecular biological aspects. Adv Cancer Res 108:21-72. doi: 10.1016/B978--12-380888-2.00002-9.

This article is part of the Challenges and Opportunities in Hepatitis B Research special issue. Viral hepatitis poses a major disease burden worldwide, with an estimated 71 million and 257 million people chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV), respectively. (1) These chronic infections are associated with ...

The Baruch S. Blumberg Institute is an independent 501 (c) (3) nonprofit research institute that was established in 2003 by the Hepatitis B Foundation to advance its research mission. The Blumberg Institute supports programs dedicated to drug discovery, biomarker discovery and translational biotechnology around common research themes such as ...

Hepatitis B is an infection of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus. The infection can be acute (short and severe) or chronic (long term). Hepatitis B can cause a chronic infection and puts people at high risk of death from cirrhosis and liver cancer. It can spread through contact with infected body fluids like blood, saliva, vaginal ...

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). An interesting question is how different are the molecular and phenotypic profiles between HBV-infected (HBV+) and non-HBV-infected (HBV-) HCCs? ... 6 Biomedical Informatics Research Lab, School of Basic Medicine and Clinical Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical ...

1. Introduction. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a major health problem despite an extensive vaccination program worldwide. Globally, 260 million people are chronically infected with HBV and 890,000 are dying yearly from complications due to the advancement of HBV infection [1,2].HBV may play a role in the pathogenesis of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma ...

Hepatitis B . Although a vaccine to prevent hepatitis B infection is available, hepatitis B-induced liver cirrhosis and liver cancer kill about 3,000 people in the United States and roughly 620,000 people worldwide each year. The virus can be spread. From mother to child during childbirth; Through sex with an infected partner

Wen-Juei Jeng, George V Papatheodoridis, Anna S F Lok. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem, with an estimated 296 million people chronically infected and 820 000 deaths worldwide in 2019. Diagnosis of HBV infection requires serological testing for HBsAg and for acute infection additional testing for IgM hepatitis ...

Her work has already made an impact and is driving a united effort. In March 2021, the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination recognized her studies in a synthesis of research updates during an international meeting designed to coalesce a community of practice around HBV prevention.

Scientifically, advances in our understanding of hepatitis B virus (HBV) are helping to bring researchers closer to new solutions, namely a functional cure - that is, undetectable viral markers ...

Hepatitis B is a vaccine-preventable liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Hepatitis B is spread when blood, semen, or other body fluids from a person infected with the virus enters the body of someone who is not infected. This can happen through sexual contact; sharing needles, syringes, or other drug-injection equipment; or ...

Clinical and Experimental Dental Research is an open access dentistry journal publishing clinical, diagnostic & experimental work within oral medicine and dentistry. Abstract Objective This study examined the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection rates and vaccination rates for hepatitis B (HB) among dental healthcare ...

Abstract. Hepatitis B infection is still a global concern progressing as acute-chronic hepatitis, severe liver failure, and death. The infection is most widely transmitted from the infected mother to a child, with infected blood and body fluids. Pregnant women, adolescents, and all adults at high risk of chronic infection are recommended to be ...

An elite group of high school seniors visited the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, earlier this month as part of the Society for Science Regeneron Science Talent Search, the nation's oldest science research competition for high school students.The visit, part of a series of educational tours for competition finalists, offered the young researchers a ...

The more time students spent in remote instruction, the further they fell behind. And, experts say, extended closures did little to stop the spread of Covid.

Abstract. Hepatitis B is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which infects the liver and may lead to chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. HBV represents a worldwide public health problem, causing major morbidity and mortality. Affordable, safe, and effective, hepatitis B vaccines are the best tools we have ...

ROSES-2024 Amendment 6 announces that New Horizons datasets are now in scope for this program element. Science goals or objectives addressed by New Horizons mission data must conform to the relevant Heliophysics science scope outlined in Section 1 of B.1 The Heliophysics Research Program Overview, and data must be publicly available 30 days prior to the Step-2 deadline, see Section 1.2 of B.4 ...

Hepatitis B viral infection is a serious global healthcare problem. It is a potentially life-threatening liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). It is often transmitted via body fluids like blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. The majority (more than 95%) of immunocompetent adults infected with HBV can clear the infection spontaneously. Patients can present with acute ...