- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: Writing a Case Study

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Reading Research Effectively

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Bibliography

The term case study refers to both a method of analysis and a specific research design for examining a problem, both of which are used in most circumstances to generalize across populations. This tab focuses on the latter--how to design and organize a research paper in the social sciences that analyzes a specific case.

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or among more than two subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in this writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a single case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- Does the case represent an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- Does the case provide important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- Does the case challenge and offer a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in practice. A case may offer you an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to the study a case in order to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- Does the case provide an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings in order to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- Does the case offer a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for exploratory research that points to a need for further examination of the research problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of Uganda. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a particular village can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community throughout rural regions of east Africa. The case could also point to the need for scholars to apply feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation.

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work. In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What was I studying? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why was this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the research problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would include summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to study the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in the context of explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular subject of analysis to study and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that frames your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; c) what were the consequences of the event.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experience he or she has had that provides an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of his/her experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using him or her as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, cultural, economic, political, etc.], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, why study Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research reveals Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks from overseas reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should be linked to the findings from the literature review. Be sure to cite any prior studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for investigating the research problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is more common to combine a description of the findings with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings It is important to remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and needs for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) restate the main argument supported by the findings from the analysis of your case; 2) clearly state the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in and your professor's preferences, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented applied to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were on social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood differently than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis.

Case Studies . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical (context-dependent) knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Essays

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2023 10:50 AM

- URL: https://libguides.pointloma.edu/ResearchPaper

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Case study: 33-year-old female presents with chronic sob and cough.

Sandeep Sharma ; Muhammad F. Hashmi ; Deepa Rawat .

Affiliations

Last Update: February 20, 2023 .

- Case Presentation

History of Present Illness: A 33-year-old white female presents after admission to the general medical/surgical hospital ward with a chief complaint of shortness of breath on exertion. She reports that she was seen for similar symptoms previously at her primary care physician’s office six months ago. At that time, she was diagnosed with acute bronchitis and treated with bronchodilators, empiric antibiotics, and a short course oral steroid taper. This management did not improve her symptoms, and she has gradually worsened over six months. She reports a 20-pound (9 kg) intentional weight loss over the past year. She denies camping, spelunking, or hunting activities. She denies any sick contacts. A brief review of systems is negative for fever, night sweats, palpitations, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, neural sensation changes, muscular changes, and increased bruising or bleeding. She admits a cough, shortness of breath, and shortness of breath on exertion.

Social History: Her tobacco use is 33 pack-years; however, she quit smoking shortly prior to the onset of symptoms, six months ago. She denies alcohol and illicit drug use. She is in a married, monogamous relationship and has three children aged 15 months to 5 years. She is employed in a cookie bakery. She has two pet doves. She traveled to Mexico for a one-week vacation one year ago.

Allergies: No known medicine, food, or environmental allergies.

Past Medical History: Hypertension

Past Surgical History: Cholecystectomy

Medications: Lisinopril 10 mg by mouth every day

Physical Exam:

Vitals: Temperature, 97.8 F; heart rate 88; respiratory rate, 22; blood pressure 130/86; body mass index, 28

General: She is well appearing but anxious, a pleasant female lying on a hospital stretcher. She is conversing freely, with respiratory distress causing her to stop mid-sentence.

Respiratory: She has diffuse rales and mild wheezing; tachypneic.

Cardiovascular: She has a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

Gastrointestinal: Bowel sounds X4. No bruits or pulsatile mass.

- Initial Evaluation

Laboratory Studies: Initial work-up from the emergency department revealed pancytopenia with a platelet count of 74,000 per mm3; hemoglobin, 8.3 g per and mild transaminase elevation, AST 90 and ALT 112. Blood cultures were drawn and currently negative for bacterial growth or Gram staining.

Chest X-ray

Impression: Mild interstitial pneumonitis

- Differential Diagnosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Immunodeficiency state and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Carcinoid lung tumors

- Tuberculosis

- Viral pneumonia

- Chlamydial pneumonia

- Coccidioidomycosis and valley fever

- Recurrent Legionella pneumonia

- Mediastinal cysts

- Mediastinal lymphoma

- Recurrent mycoplasma infection

- Pancoast syndrome

- Pneumococcal infection

- Sarcoidosis

- Small cell lung cancer

- Aspergillosis

- Blastomycosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Actinomycosis

- Confirmatory Evaluation

CT of the chest was performed to further the pulmonary diagnosis; it showed a diffuse centrilobular micronodular pattern without focal consolidation.

On finding pulmonary consolidation on the CT of the chest, a pulmonary consultation was obtained. Further history was taken, which revealed that she has two pet doves. As this was her third day of broad-spectrum antibiotics for a bacterial infection and she was not getting better, it was decided to perform diagnostic bronchoscopy of the lungs with bronchoalveolar lavage to look for any atypical or rare infections and to rule out malignancy (Image 1).

Bronchoalveolar lavage returned with a fluid that was cloudy and muddy in appearance. There was no bleeding. Cytology showed Histoplasma capsulatum .

Based on the bronchoscopic findings, a diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent patient was made.

Pulmonary histoplasmosis in asymptomatic patients is self-resolving and requires no treatment. However, once symptoms develop, such as in our above patient, a decision to treat needs to be made. In mild, tolerable cases, no treatment other than close monitoring is necessary. However, once symptoms progress to moderate or severe, or if they are prolonged for greater than four weeks, treatment with itraconazole is indicated. The anticipated duration is 6 to 12 weeks total. The response should be monitored with a chest x-ray. Furthermore, observation for recurrence is necessary for several years following the diagnosis. If the illness is determined to be severe or does not respond to itraconazole, amphotericin B should be initiated for a minimum of 2 weeks, but up to 1 year. Cotreatment with methylprednisolone is indicated to improve pulmonary compliance and reduce inflammation, thus improving work of respiration. [1] [2] [3]

Histoplasmosis, also known as Darling disease, Ohio valley disease, reticuloendotheliosis, caver's disease, and spelunker's lung, is a disease caused by the dimorphic fungi Histoplasma capsulatum native to the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi River valleys of the United States. The two phases of Histoplasma are the mycelial phase and the yeast phase.

Etiology/Pathophysiology

Histoplasmosis is caused by inhaling the microconidia of Histoplasma spp. fungus into the lungs. The mycelial phase is present at ambient temperature in the environment, and upon exposure to 37 C, such as in a host’s lungs, it changes into budding yeast cells. This transition is an important determinant in the establishment of infection. Inhalation from soil is a major route of transmission leading to infection. Human-to-human transmission has not been reported. Infected individuals may harbor many yeast-forming colonies chronically, which remain viable for years after initial inoculation. The finding that individuals who have moved or traveled from endemic to non-endemic areas may exhibit a reactivated infection after many months to years supports this long-term viability. However, the precise mechanism of reactivation in chronic carriers remains unknown.

Infection ranges from an asymptomatic illness to a life-threatening disease, depending on the host’s immunological status, fungal inoculum size, and other factors. Histoplasma spp. have grown particularly well in organic matter enriched with bird or bat excrement, leading to the association that spelunking in bat-feces-rich caves increases the risk of infection. Likewise, ownership of pet birds increases the rate of inoculation. In our case, the patient did travel outside of Nebraska within the last year and owned two birds; these are her primary increased risk factors. [4]

Non-immunocompromised patients present with a self-limited respiratory infection. However, the infection in immunocompromised hosts disseminated histoplasmosis progresses very aggressively. Within a few days, histoplasmosis can reach a fatality rate of 100% if not treated aggressively and appropriately. Pulmonary histoplasmosis may progress to a systemic infection. Like its pulmonary counterpart, the disseminated infection is related to exposure to soil containing infectious yeast. The disseminated disease progresses more slowly in immunocompetent hosts compared to immunocompromised hosts. However, if the infection is not treated, fatality rates are similar. The pathophysiology for disseminated disease is that once inhaled, Histoplasma yeast are ingested by macrophages. The macrophages travel into the lymphatic system where the disease, if not contained, spreads to different organs in a linear fashion following the lymphatic system and ultimately into the systemic circulation. Once this occurs, a full spectrum of disease is possible. Inside the macrophage, this fungus is contained in a phagosome. It requires thiamine for continued development and growth and will consume systemic thiamine. In immunocompetent hosts, strong cellular immunity, including macrophages, epithelial, and lymphocytes, surround the yeast buds to keep infection localized. Eventually, it will become calcified as granulomatous tissue. In immunocompromised hosts, the organisms disseminate to the reticuloendothelial system, leading to progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. [5] [6]

Symptoms of infection typically begin to show within three to17 days. Immunocompetent individuals often have clinically silent manifestations with no apparent ill effects. The acute phase of infection presents as nonspecific respiratory symptoms, including cough and flu. A chest x-ray is read as normal in 40% to 70% of cases. Chronic infection can resemble tuberculosis with granulomatous changes or cavitation. The disseminated illness can lead to hepatosplenomegaly, adrenal enlargement, and lymphadenopathy. The infected sites usually calcify as they heal. Histoplasmosis is one of the most common causes of mediastinitis. Presentation of the disease may vary as any other organ in the body may be affected by the disseminated infection. [7]

The clinical presentation of the disease has a wide-spectrum presentation which makes diagnosis difficult. The mild pulmonary illness may appear as a flu-like illness. The severe form includes chronic pulmonary manifestation, which may occur in the presence of underlying lung disease. The disseminated form is characterized by the spread of the organism to extrapulmonary sites with proportional findings on imaging or laboratory studies. The Gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of histoplasmosis is through culturing the organism. However, diagnosis can be established by histological analysis of samples containing the organism taken from infected organs. It can be diagnosed by antigen detection in blood or urine, PCR, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The diagnosis also can be made by testing for antibodies again the fungus. [8]

Pulmonary histoplasmosis in asymptomatic patients is self-resolving and requires no treatment. However, once symptoms develop, such as in our above patient, a decision to treat needs to be made. In mild, tolerable cases, no treatment other than close monitoring is necessary. However, once symptoms progress to moderate or severe or if they are prolonged for greater than four weeks, treatment with itraconazole is indicated. The anticipated duration is 6 to 12 weeks. The patient's response should be monitored with a chest x-ray. Furthermore, observation for recurrence is necessary for several years following the diagnosis. If the illness is determined to be severe or does not respond to itraconazole, amphotericin B should be initiated for a minimum of 2 weeks, but up to 1 year. Cotreatment with methylprednisolone is indicated to improve pulmonary compliance and reduce inflammation, thus improving the work of respiration.

The disseminated disease requires similar systemic antifungal therapy to pulmonary infection. Additionally, procedural intervention may be necessary, depending on the site of dissemination, to include thoracentesis, pericardiocentesis, or abdominocentesis. Ocular involvement requires steroid treatment additions and necessitates ophthalmology consultation. In pericarditis patients, antifungals are contraindicated because the subsequent inflammatory reaction from therapy would worsen pericarditis.

Patients may necessitate intensive care unit placement dependent on their respiratory status, as they may pose a risk for rapid decompensation. Should this occur, respiratory support is necessary, including non-invasive BiPAP or invasive mechanical intubation. Surgical interventions are rarely warranted; however, bronchoscopy is useful as both a diagnostic measure to collect sputum samples from the lung and therapeutic to clear excess secretions from the alveoli. Patients are at risk for developing a coexistent bacterial infection, and appropriate antibiotics should be considered after 2 to 4 months of known infection if symptoms are still present. [9]

Prognosis

If not treated appropriately and in a timely fashion, the disease can be fatal, and complications will arise, such as recurrent pneumonia leading to respiratory failure, superior vena cava syndrome, fibrosing mediastinitis, pulmonary vessel obstruction leading to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure, and progressive fibrosis of lymph nodes. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis usually has a good outcome on symptomatic therapy alone, with 90% of patients being asymptomatic. Disseminated histoplasmosis, if untreated, results in death within 2 to 24 months. Overall, there is a relapse rate of 50% in acute disseminated histoplasmosis. In chronic treatment, however, this relapse rate decreases to 10% to 20%. Death is imminent without treatment.

- Pearls of Wisdom

While illnesses such as pneumonia are more prevalent, it is important to keep in mind that more rare diseases are always possible. Keeping in mind that every infiltrates on a chest X-ray or chest CT is not guaranteed to be simple pneumonia. Key information to remember is that if the patient is not improving under optimal therapy for a condition, the working diagnosis is either wrong or the treatment modality chosen by the physician is wrong and should be adjusted. When this occurs, it is essential to collect a more detailed history and refer the patient for appropriate consultation with a pulmonologist or infectious disease specialist. Doing so, in this case, yielded workup with bronchoalveolar lavage and microscopic evaluation. Microscopy is invaluable for definitively diagnosing a pulmonary consolidation as exemplified here where the results showed small, budding, intracellular yeast in tissue sized 2 to 5 microns that were readily apparent on hematoxylin and eosin staining and minimal, normal flora bacterial growth.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

This case demonstrates how all interprofessional healthcare team members need to be involved in arriving at a correct diagnosis. Clinicians, specialists, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory technicians all bear responsibility for carrying out the duties pertaining to their particular discipline and sharing any findings with all team members. An incorrect diagnosis will almost inevitably lead to incorrect treatment, so coordinated activity, open communication, and empowerment to voice concerns are all part of the dynamic that needs to drive such cases so patients will attain the best possible outcomes.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Histoplasma Contributed by Sandeep Sharma, MD

Disclosure: Sandeep Sharma declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Muhammad Hashmi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Deepa Rawat declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Rawat D. Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough. [Updated 2023 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Palliative Chemotherapy: Does It Only Provide False Hope? The Role of Palliative Care in a Young Patient With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. [J Adv Pract Oncol. 2017] Review Palliative Chemotherapy: Does It Only Provide False Hope? The Role of Palliative Care in a Young Patient With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. Doverspike L, Kurtz S, Selvaggi K. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2017 May-Jun; 8(4):382-386. Epub 2017 May 1.

- Review Breathlessness with pulmonary metastases: a multimodal approach. [J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013] Review Breathlessness with pulmonary metastases: a multimodal approach. Brant JM. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013 Nov; 4(6):415-22.

- A 50-Year Old Woman With Recurrent Right-Sided Chest Pain. [Chest. 2022] A 50-Year Old Woman With Recurrent Right-Sided Chest Pain. Saha BK, Bonnier A, Chong WH, Chenna P. Chest. 2022 Feb; 161(2):e85-e89.

- Suicidal Ideation. [StatPearls. 2024] Suicidal Ideation. Harmer B, Lee S, Duong TVH, Saadabadi A. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Review Domperidone. [Drugs and Lactation Database (...] Review Domperidone. . Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

Recent Activity

- Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough - StatPearls Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with JSH?

- About Journal of Social History

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Editor-in-Chief

Matthew Karush

Founding Editor

Peter Stearns

As a top-ranked journal in the field of social history, publishing articles in social history from all areas and periods, JSH is widely recognized for its high-quality and innovative scholarship.

Latest articles

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of Journal of Social History are published online.

Prize-Winning Articles

2019 Premio para Mejor Texto por un Alumno (Award for Best Graduate Student Paper), Latin American Studies Association

- " 'Let Us Bring it with Love': Violence, Solidarity, and the Making of a Social Disaster in the Wake of the 1906 Earthquake in Valparaíso, Chile " by Joshua Savala

Browse more prize-winning articles from JSH .

The Journal of Social History has served as one of the leading outlets for work in its field since its inception over 40 years ago. Submit your research today!

Related Titles

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1527-1897

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Teaching Innovations

Teaching Social History: An Update

Peter N. Stearns | Oct 1, 1989

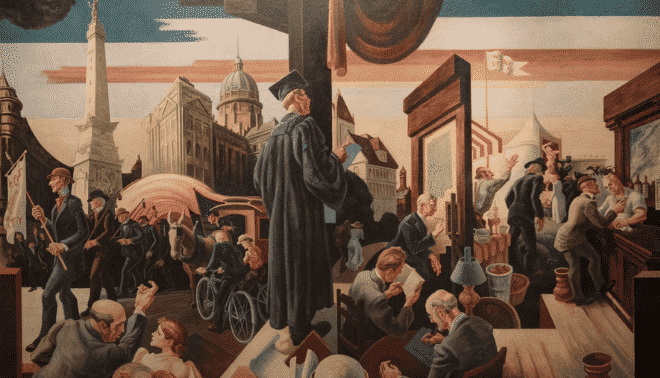

During the past decade a number of history educators have discussed the reasons for including social history approaches and findings in mainstream history teaching, and also the various mechanisms by which this can be done. The subject was compelling because of social history's surge on the discipline's research agenda. Currently more than one third of all research historians in the United States add the "social" label, and there is little question that the bulk of the most innovative and widely-noted research in the past twenty years has fallen in this category. (Think back, for example, to how little was known or taught about slavery in U.S. history surveys just a generation ago.) The subject was also compelling because social history added both a list of new topics to the understanding of the past—from demographic behavior to basic leisure forms—and a sense of excitement that more conventional staples were often missing. Finally, it was compelling because it posed some obvious challenges:

- Social history topics did not fit neatly into the established agenda—how, for example, can one combine an analysis of the rise of soccer with a narrative of late nineteenth century British politics?

- Many social historians borrowed methods and concepts, ranging from quantification through sociology to—most recently—anthropology, that were different from standard descriptive political or intellectual history.

- And finally, social historians, quite apart from their topic choice, had a style and focus that were distinctive: they examined trends and processes as their empirical core, rather than events and individual personalities.

In sum, teaching social history meant a good bit of new learning. It meant deciding what familiar topics to curtail in favor of wider coverage, and figuring out how to juxtapose event-based chronology, such as the series of wars, reigns, or presidencies that form the backbone of traditional textbook history, with shifts in processes, such as the advent of a new birth or death rate pattern, where hundreds of thousands of separate events—decisions about children, sex, and health—accumulated over a decade or more into a new demographic framework. Clearly, teaching social history in the classroom was not easy.

Yet there were also some obvious reasons to make the attempt. The field was vibrant. It produced undeniable new knowledge which could add to students' factual fund and also stimulate historically-informed thinking about a host of topics significant in their own lives and society, such as the nature of adolescence and its emergence as a discrete life-phase in the nineteenth century. Social history provided potential links with other social sciences, though the interdisciplinary promise was sometimes more rhetorical than real. In dealing with topics such as the family, social history might incorporate components of a larger social studies curriculum with students benefiting from improved integration. Finally, social history topics might bring a wider range of students into the field of history than the staple diet of politics and high culture by themselves achieved. Serious study into the history of key groups such as women, workers, and Afro-Americans spurred the new research and also could engage various sectors of the student population. New topics, such as leisure or family, might similarly draw some students into a serious discussion of the problems of change and continuity because of their immediacy in contemporary life. For a host of reasons, then, the urge to deal seriously with social history as a teaching area has remained strong despite undeniable practical and conceptual problems.

As a result, social history has been frequently defined and justified, and its major subfields outlined as subjects for classroom use. College Board recommendations have urged serious attention to the field as prerequisite for successful college work. The National Council for the Social Studies has issued a number of valuable how-to pamphlets, as have numerous other organizations. (Matthew Downey, Teaching American History: New Directions , Washington, 1982; College Entrance Examination Board. Academic Preparation in Social Studies , New York, 1986; Linda W. Rosenzweig, ed., "Teaching About Social History," Social Education 48 [1982]; James B. Gardner and Rollie Adams, eds., Ordinary People and Everyday Life , Nashville, 1983.) After a slight lag when focus riveted on research strategies, social historians themselves began producing textbooks and supplementary materials, particularly, but not exclusively, at the college level. (As examples, see Gary B. Nash, Julie R. Jeffrey and others, The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society , New York, 1986; Constance Bouchard and Peter N. Stearns, Life and Society in the West , 2 vols, San Diego, 1987; and at the high school level, Linda W. Rosenzweig and Peter N. Stearns, Themes in Modern Social History , Pittsburgh, 1985.) Workshops, along with revisions in college curricula, helped spread the word to many innovative teachers both old and young. Any discussion of social history in teaching by now proceeds along a well-trodden path.

Indeed, given the coverage, why return to the subject of social history teaching? There are three reasons. First, suggestions for altering some time-tested teaching strategies take time to sink in, perhaps particularly in a discipline that many practitioners fancy precisely because it seems familiar—the intellectual equivalent of well-scuffed slippers. Second, a recent surge of counter-attacks continues to require comment. Third, and most important, significant bases for synthesis, developed in social history as a research field, offer new promise for historical teaching in settings that require some means of linking the novelty of social history to the staples of political and intellectual coverage.

A social history update, skimming over the now-familiar groundwork, is timely in several senses. It allows response to some recent distractions and distortions in a number of educational policy statements, and uses this criticism to improve the articulation of social history's teaching purpose. It permits a clear acknowledgment of important maturation in thinking about the field and its relationship with other history teaching goals. An evaluation of social history teaching today cannot and need not be confined to the valid but often slightly abstract sketches offered a decade ago; gratifyingly, there is progress to report.

Reconsidering the Standard Menu

An update report must begin, however, on a more prosaic note: a comment on the lags and disjunctures in introducing social history to the teaching repertoire. Development has been real, but uneven, and some initial efforts at simplification proved misleading.

There is no question that the teaching of social history has advanced far more rapidly in college curricula than in secondary schools. While this disparity was initially unsurprising, given social history's research-driven impulse, it has become counter-productive. Among other things, we are failing to introduce students to history's real range when their attitudes toward the discipline are being formed. A host of imaginative high school teachers have, to be sure, pressed forward into at least some aspects of social history, not only in survey courses, but in social studies offerings where the interdisciplinary potential can be tapped. Some social history staples have even entered more widely; units on slavery and immigrants have important social history content. But for all the achievements, the hesitations are even more striking. Teachers of high-prestige offerings, including Advanced Placement American history (despite serious College Board encouragement to the contrary) and, even more frequently, Western civilization courses often perversely insist on strictly political and high-culture definitions. They add college-level, but highly dated, readings to testify to their advanced level rather than catch up with the field. Consequently, survey textbooks and their publishers remain timid.

Furthermore, in courses and texts alike, some initially understandable transitions have not been adequately rethought, despite their limitations. Some school curricula, responding to well-intentioned guidelines, define their social history curriculum in terms of almost every conceivable American ethnic group to demonstrate that all the ingredients of the melting pot have a significant past. The proposition is correct but at the teaching level unwieldy, producing unnecessary, and highly vulnerable, incoherence. Larger themes, such as particularly significant or exemplary groupings, or integrative categories such as a comparison of the histories of "new" and "old" immigrants and their receptions, can and must be found.

Another approach, still more frustrating, is the addition of an occasional social history snippet to an otherwise conventional survey. In texts the snippet approach shows an occasional "this is how they lived" insert, or tacked-on segments on such subjects as women in colonial society. In actual courses, the same filler approach shows the odd day devoted to a social history topic, with no coherence or system applied. Students, of course, readily perceive the change in tone, often correctly assuming social history is intended as light relief and that they will not be tested. Here too, the experience of teaching social history suggests some corrective guidelines: deal with social history topics with a seriousness equal to other coverage; return to topics in each key time period so that the family, for example, can be seen in terms of changes and continuities over time, rather than as an institution evoked haphazardly; provide some opportunity to discuss the relationship between social history topics and other developments; show how family change results from new political or economic forms or affects these forms in turn.

Social history teaching at other educational levels has moved forward more rapidly. As a means of introducing young students to the past, social history topics have long been a primary school staple, and one recent report urges an enhancement at the concentration at this level (Bradley Commission on History in Schools, Building a History Curriculum , Westlake, OH, 1988). Social history courses, and subfield topical courses on family, work, women, and a host of other subjects, dot college curricula, usually paralleling more conventional national history or period offerings, but in some cases increasingly upstaging them. Even here, however, curriculum problems have by no means entirely been resolved. Much of the task of pulling the past together is left to students themselves as social historians merrily spin off one topical course after another, not even stopping to talk about what ties their field together in terms of central causal forces or periodization, and conventional courses, including many surveys, introduce serious social history analysis warily if at all. The past, at the college level, is much richer than it once was, and the return of students to history courses in new numbers in recent years reflects the excitement. But opportunities to discuss coherence or interrelationships are, too often, few and far between.