Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Inclusive Education: Literature Review

The education of disabled children never received such amount of consideration and special efforts by government and non-government agencies in past as in present days. The attitude of the community in general and the attitude of parents in particular towards the education of the disabled have undergone change with the development of society and civilization.

Related Papers

vatika sibal

Executive Summary In India, inclusive education for children with disability has only recently been accepted in policy and in principle. In light of supportive policy and legislation, the present paper argues for individual initiative on part of an institution and colleges to implement programmes of inclusive education for children with disabilities in their classrooms. The paper provides guidelines in a generalized mode that institutions can follow to initiate such programmes. In this context, this paper argues for individual initiative on part of institutions to extend facilities for children with disabilities within their regular school settings. The paper further provides guidelines that institutions can adopt to set up inclusive education practices. The guidelines were derived from an empirical study which entailed examining prevalent practices and introducing inclusion in a regular institution setting. It is suggested that institutions can implement inclusive education programmes if they are adequately prepared, are able to garner support of all stakeholders involved in the process and have basic resources to run the programmes. The guidelines also suggest ways in which curriculum adaptations, teaching methodology and evaluation procedures can be adapted to suit needs of students with special needs. Issues of role allocation and seeking support of parents and peers are also dealt with. The recommendations that intuitions can adopt to implement inclusive education programmes for students with special needs within their regular set ups. The recommendations have been presented in a generalized mode to permit institute to interpret, modify and adapt the guidelines based on their individual needs and characteristics. It is pertinent those institutes that initiate such programmes assess their strengths and weaknesses at the outset and ensure adequate cooperation from the school management as well as the administrative and teaching staff. It is important to state here that an inclusive education programme does not require resource overload or elaborate preparations. With policy support, opportunities for training of teachers and cooperation from parents and the peer group, inclusive practices can be effectively adopted by any school. Clarity of vision, commitment to the goal of inclusion, and a perceptible understanding of the nuances involved in such an initiative are central to the success of the programme. Emotional commitment to inclusion emerges when the intellectual understanding of the concept goes through a democratic visioning process involving all the stakeholders expressing their opinions and feelings.

Inclusive Education: children with disabilities - - Background paper prepared for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report Inclusion and education 2020

Paula Frederica Hunt

This paper presents the case for inclusive education for children with disabilities as the entry point for policy development and implementation of inclusive education in the broad sense: inclusive, quality education for ALL children. The paper starts by providing a short historical perspective of the education of children with disabilities and continues with a description of the essential elements of an inclusive legislative framework, with a particular focus on General Comment no4 of Article 24 (CRPD). The benefits of inclusive education, as well as financing mechanisms, and required accountability measures for implementation, are also discussed. Then, the paper discusses the foundational basis of curriculum for inclusion, as well as issues related to a transformative teacher education practice. The final chapters describe what an inclusive school might look like, as well as the role of students, families and communities in creating an inclusive education system. It should be noted that this paper is substantiated with selective literature, with attention payed to an equitable geographic coverage.

ankur madan

Research Anthology on Inclusive Practices for Educators and Administrators in Special Education

Shekh Farid

BRAC, a leading international development organization, has been working to ensure the rights of persons with disabilities to education through its inclusive education program. This article discusses the BRAC approach in Bangladesh and aims to identify its strategies that are effective in facilitating inclusion. It employed a qualitative research approach where data were collected from students with disabilities, their parents, and BRAC's teachers and staffs using qualitative data collection techniques. The results show that the disability-inclusive policy and all other activities are strongly monitored by a separate unit under BRAC Education Program (BEP). It mainly focuses on sensitizing its teachers and staff to the issue through training, discussing the issue in all meetings and ensuring effective use of a working manual developed by the unit. Group-based learning and involving them in income generating activities were also effective. The findings of the study would be usefu...

Shonazar Botirov

This article describes the introduction of inclusive education, what it is, about children with disabilities, as well as the positive and negative aspects of inclusive education.

Ikhfi Imaniah

This paper identifies and discusses major issues and trends in special education in Indonesia, including implications of trends for the future developments. Trends are discussed for the following areas: (1) inclusion and integration, issues will remain unresolved in the near future; (2) early childhood and postsecondary education with disability students, special education will be viewed as lifespan schooling; (3) transitions and life skills, these will receive greater emphasis; and (4) consultation and collaboration, more emphasis but problems remain. Moreover, the participant of the study in this paper was an autism student of twelve years old who lived at Maguwoharjo, Yogyakarta. This study was qualitative with case study as an approach of the research. The researchers conclude the autism that has good academic, communication and emotional skill are able to go to integrated school accompanied by guidance teacher. But in practice, inclusive education in Indonesia is inseparable from stakeholders ranging from government and institutions such as schools, educators, school environment, community and parents to support the goal of inclusive education itself. Adequate infrastructure also needs to be given to the school that organizes inclusive education for an efficient and effective students understanding learning-oriented of inclusive education. In short, every child has the same opportunity in education, yet for special education which is aimed at student with special educational needs.

Rajendra KR

Inclusive Education on Children with Learning Disabilities

Arien Arien

ABSTRACT Name : Zahrien Assyifa Nur Palisma NISN : 0002223086 Title : Analysis of Inclusive Education on Children with Learning Disabilities (Case study on 4th Grade of Mutiara Bunda Elementary School, Cilegon Banten Inclusive Education is an approach that aims to change the education system by translating barriers that can accommodate every student to participate fully in education. That is, every child is entitled to a decent education, not to mention children with learning disabilities. Children with learning disabilities are interpreted as children who find it difficult to receive formal and non-formal learning because of certain psychological "disabilities". This study aims to determine how much the effectiveness of inclusive education for children with learning disabilities in Mutiara Bunda Elementary School, Cilegon. The method used by the author is the field research that is carried out on October 6th, 2017 at Bunda Mutiara Elementary School, Street. Boulevard Raya Block A2 Number.6 Taman Cilegon Indah, Sukmajaya, Cilegon Banten.The results obtained from this study are: a. Inclusive Education is the right solution for children with learning disabilities even for all children with disabilities. b. The curriculum used in inclusive schools is similar to the curriculum in public schools. There is little modification in children with learning disabilities as well as some omissions and curriculum substitutions. Keywords: Inclusive Education, Children with Learning Disabilities

Swati Chakraborty

International Journal of …

Missy Morton

RELATED PAPERS

Intensive Care Medicine

Cristina Messa

Jose Luis Cardoso

Kris Bachus

Cadernos de Saúde Pública

Luiz Facchini

Schmerzmedizin

Arno Zurstrassen

IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers

Xiankun Jin

loubna RIFI

BMC Medical Education

feray guven

Alfred Murye

Roczniki Humanistyczne

Michał Wilczewski

Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology

Hye Jin Baek

Bénédicte Bourgeois

Andrea Currylow

Journal of diabetes research

Manuel Calderón Nava

Ho Le Thi 002868

British Journal of Special Education

Jo Trowsdale

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Norzulaani Khalid

Biochemical Pharmacology

Martin Struve

ANTONIOS KEFALIAKOS

Necdet Sensoy

Dayron Douglas Calvo Saborit

INOBIS: Jurnal Inovasi Bisnis dan Manajemen Indonesia

Tongam sinambela

Ahmet Kartal

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Review of Literature: Inclusive Education

This brief review of relevant literature on inclusive education forms a component of the larger Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report delivered by the Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE) team to JFA Purple Orange in October, 2020.

Suggested citation for full evaluation report:

Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Bissaker, K., Carson, K. L., Davidson, J., & Walker, P. M. (2020). Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report. Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE), Flinders University.

https://sites.flinders.edu.au/rise

Introduction

Inclusive education has featured prominently in worldwide educational discourse and reform efforts over the past 30 years (Berlach & Chambers, 2011; Forlin, 2006). Inclusive schools are critical to providing a strong foundation for young people with disabilities to access, participate in and contribute to their communities and lead fulfilling lives (Hehir et al., 2016). Schools also represent a key condition for the development of thriving, inclusive communities for all citizens. Yet, as reflected in submissions to the current Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, and consistent with recent South Australian reports (Parliament of South Australia, 2017; Walker, 2017), many students living with disability (and their families) continue to report negative experiences of education. While progress has been made, traditional educational structures and practices often run counter to inclusive goals (Slee, 2013), and inconsistencies occur between theory and policy and the implementation of inclusive principles and practices in schools (Carrington & Elkins, 2002; Graham & Spandagou, 2011). In addition, both preservice and practicing teachers consistently report feeling underprepared to teach students with disabilities and special educational needs (Jarvis, 2019; OECD, 2019).

Despite legislation and policy imperatives related to inclusive education, there remains a lack of consensus in the field about the definition of inclusion and associated models of inclusive practice (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; Kinsella, 2020). Multiple conceptualisations of inclusion and theoretical approaches to fostering inclusion in schools may contribute to confusion and uncertainty for educators and policymakers. With schools facing growing accountability and teachers expected to educate an increasingly diverse student population (Anderson & Boyle, 2015), it is vital that the concept of inclusive education is demystified for practitioners. Against this backdrop, initiatives such as the Inclusive School Communities (ISC) project that aim to deepen understandings of inclusion and increase the capacity of school communities to provide an inclusive education, are particularly important.

Inclusive Education

Inclusive education is based on a philosophy that stems from principles of social justice, and is primarily concerned with mitigating educational inequalities, exclusion, and discrimination (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Waitoller & Artiles, 2013). Although inclusion was originally concerned with ‘disability’ and ‘special educational needs’ (Ainscow et al., 2006; Van Mieghem et al., 2020), the term has evolved to embody valuing diversity among all students, regardless of their circumstances (e.g., Carter & Abawi, 2018; Thomas, 2013). Among interpretations of inclusion, common themes include fairness, equality, respect, diversity, participation, community, leadership, commitment, shared vision, and collaboration (Booth, 2012; McMaster, 2015). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which Australia is a signatory, defines inclusive education as:

. . . a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences. (United Nations, 2016, para 11)

Consistent with this definition, inclusive education now generally refers to the process of addressing the learning needs of all students, through ensuring participation, achievement growth, and a sense of belonging, enabling all students to reach their full potential (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). Inclusion is concerned with identifying and removing potential barriers to presence (attendance, access), meaningful participation, growth from an individual starting point, and feelings of connectedness and belonging for all students and community members, with a focus on those at particular risk of marginalisation or exclusion (Ainscow et al., 2006; Forlin et al., 2013).

Critically, the view of inclusion described above moves beyond considerations of the physical placement of a student in a particular setting or grouping configuration. That is, while physical access to a mainstream school environment is essential to maintain the rights of students living with disabilities to access education “on the same basis” as their peers (consistent with legislation and human rights principles), it is not sufficient to ensure inclusion. Rather, inclusion can be considered a multi-faceted approach involving processes, practices, policies and cultures at all levels of a school and system (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). Inclusive education is responsive to each child and promotes flexibility, rather than expecting the child to change in order to ‘fit’ rigid schooling structures. The latter approach reflects integration, and inclusion is also inconsistent with segregation, in which children with disabilities are routinely educated separately from others.

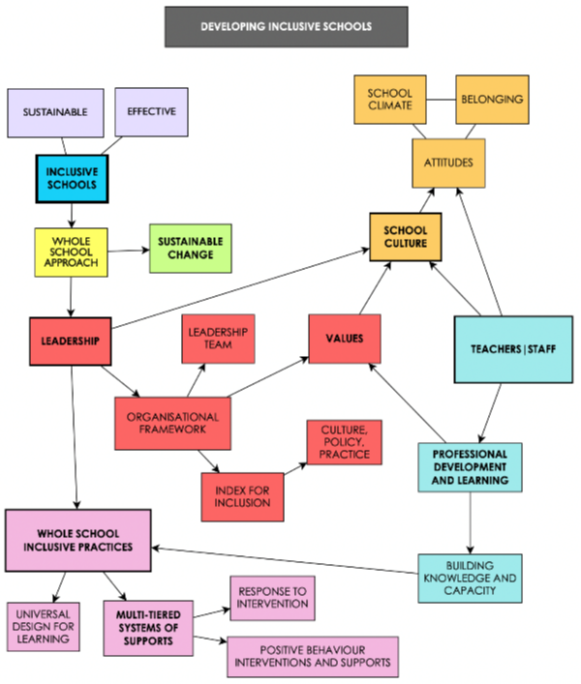

Considerable research has focused on the implementation of inclusive school processes, practices and cultures that are sustainable over time. Although a number of frameworks to achieve sustainable inclusive practice have been proposed, key elements are consistent across approaches and well supported by research (Booth & Ainscow 2011; Azorín & Ainscow, 2020). These interconnected elements are summarised in Figure 1 and considered fundamental to the process of achieving whole-school (and systemic) cultural change towards more inclusive ways of working. Of particular relevance to the Inclusive School Communities project are the concepts of a whole school approach, leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and multi-tiered models of inclusive practice.

Inclusion as a Whole School Approach

Adopting a whole of school approach to inclusive education is fundamental to ensure efficacy and sustainability (Read et al., 2015). The process of developing inclusive schools is complex and multi-faceted, requiring time, commitment, ongoing reflection, and sustained effort. For inclusion to truly take root in schools, changes must be made from the inside out; a strong foundation must be built from inclusive school values, committed leadership, and shared vision amongst staff to support whole school structural reforms to policy, pedagogy, and practice (Ekins & Grimes, 2009). Whilst challenging, “it is necessary to unsettle default modes of operation” in schools (Johnston & Hayes, 2007, p.376), as inclusive education requires new, more efficient and effective ways of supporting student participation and achievement. This is made possible by implementing flexible, planned whole school support structures, such as multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), where teachers work collaboratively with specialist staff to identify, monitor, and support students requiring varying levels and types of intervention at different times, and for different purposes (Sailor, 2017; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). This contrasts to the more traditional, ‘categorical’ and segregated approach of general educators referring identified students with additional needs to special educators, to devise and administer further education in isolation from the regular classroom (Sailor, 2017).

Figure 1. Interconnected elements in sustainable inclusive education, derived from research.

Even at the classroom level, inclusive planning and teaching practices must be supported by school policies, practices, and culture in order to be sustainable (Sailor, 2017). Barriers to inclusive classroom practice can include lack of effective professional learning and support for teachers; teachers’ lack of willingness to include students with particular needs; attitudes that are inconsistent with inclusive practices; teacher education that fails to address concerns about inclusion; and, a lack of accountability for the implementation of inclusive teaching practices (Forlin & Chambers, 2011; Forlin et al., 2008; van Kraayenoord et al., 2014). Addressing each of these relies on targeted, coordinated support. The complexity of embedding inclusive practices such as differentiated instruction or Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into classroom work is often underestimated, and these practices have the greatest chance of becoming embedded when they are reinforced by a shared vision and collaborative effort (McMaster, 2013; Sailor, 2015; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2017).

Sustainable, whole school change cannot be achieved via focus on a single element of inclusion in isolation, as components do not function in isolation. Rather, the core elements of inclusion including leadership, school culture, building staff capacity, and inclusive practices are parts of an interdependent system. Hence, key elements of inclusion must be considered collectively and accounted for in advanced planning to ensure they function harmoniously and are integrated into the developing inclusive fabric of the school (Alborno & Gaad, 2014).

Leadership for Inclusion

The importance of leadership for determining the success of school reforms or changes to practice is well established in the literature (McMaster & Elliot, 2014; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). Becoming a more inclusive school often requires significant shifts in school values, culture, practices, and organisational systems; thus, leadership is critical to ensuring sustainable inclusive change in schools (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). School leaders are highly influential figures whose values, beliefs, and actions directly affect the culture of the school, expectations of staff, and school operations (Slater, 2012; Wong & Cheung, 2009). It is critical that school leaders are committed to embodying inclusive principles, establishing and modelling a standard of behaviour that promotes the development of inclusion within the school community.

Organisational change on the scale often required for inclusion requires leadership across multiple levels (Jarvis et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2008). It is likely to be most effective when facilitated through models of distributed leadership across roles and levels within a school, and when the case for change is underpinned by a broader, shared vision specifically related to student outcomes (Harris, 2013). Research has established the relationship between distributed leadership practices and the implementation of effective, inclusive school practices (Miškolci et al., 2016; Mullick et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2008; Sharp et al., 2020). Leaders should consider utilising inclusive styles of management, replacing hierarchical structures with leadership teams (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015). Effective school leadership enables shared responsibility, vision, and consistency within the school community, which is vital for the successful implementation of inclusion (Poon- McBrayer & Wong, 2013).

Fostering Inclusive School Cultures

Developing an inclusive school culture is a fundamental component of developing sustainable inclusion in schools (Dyson et al., 2004; McMaster, 2013). The culture of a school is made up of the shared values, attitudes, and beliefs of the school community (Booth, 2012). Transitioning to a truly inclusive culture requires close attention to attitudes and general support of the inclusive values being adopted, particularly by staff, but also by students and the broader school community (Dyson et al., 2004; Forlin & Chambers, 2011).

A whole school approach to inclusion prompts a school to reflect on and embrace values based on inclusive principles, such as equality, diversity, and respect. This process cannot be imposed, but should be a collaborative exercise with school leaders and staff, to ensure any pedagogical philosophies or practices based on outdated ideas or past assumptions are not operating by default (Johnston & Hayes, 2007; Schein, 2004). Evaluating and redefining existing school values also requires professional learning, to facilitate a collective reconceptualisation of inclusion specific to the unique context of the school; the meaning, aims, and expectations of inclusion must be clarified for the school community, to encourage a shared understanding, vision, and responsibility for supporting the inclusive changes unfolding within the school (Horrocks et al., 2008; Symes & Humphrey, 2011). Finally, it is vital that school policies and practices are regularly revised, to ensure that they reinforce the inclusive values and culture of the school; otherwise, they can act as a potential barrier to the development of sustainable whole school inclusion (Dybvik, 2004; McMaster, 2013).

Building Teachers’ Capacity for Inclusive Practice

Building the knowledge and capacity of teachers and other school staff is crucial to developing sustainable inclusion in schools. The evolution of an inclusive school culture depends on aligning the attitudes and behaviour of staff (McMaster, 2015). Teachers must be knowledgeable about how inclusive education has progressed over time, particularly how the meaning of inclusion has changed and what it means in their school context. Understanding the concepts and values behind inclusion can help teachers appreciate its significance, prompting reflection of their own practice and how they see their students (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Skidmore, 2004). This can allow any unhelpful assumptions or beliefs that may have been unconsciously informing their teaching practice, particularly in relation to students living with disability, to be challenged and revised (Ashby, 2012; Ashton & Arlington, 2019).

While attention to attitudes, values, and broad understandings is fundamental, the goals of inclusion will only be achieved when principles are consistently enacted in daily classroom practice. At the classroom level, inclusion relies on teachers’ willingness and capacity to apply evidence-informed inclusive practices, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (Van Mieghem et al., 2020). UDL is a planning framework for learning activities designed to maximise curriculum accessibility for all students by offering multiple opportunities for engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2018; Sailor, 2015). Differentiated Instruction (DI) is a holistic framework of interdependent principles and practices that enables teachers to design learning experiences to address variation in students’ readiness, interests and learning preferences (Tomlinson, 2014). UDL is primarily focused on inclusive task design, although the model has been expanded in recent years to include greater attention to pedagogy. Differentiation encompasses elements of planning (clear, concept-based learning objectives; formative assessment to inform proactive decision-making for diverse students), teaching (strategies to differentiate by readiness, interest and learning preference; ensuring respectful tasks and ‘teaching up’), and learning environment (flexible grouping, classroom management, establishing an inclusive culture) (Jarvis, 2015; Tomlinson, 2014).

The application of UDL and DI principles and practices by skilled teachers enables diverse students to access curriculum content in multiple ways (Kozik et al., 2009; McMaster, 2013), at appropriate levels of challenge and support to ensure learning growth, and in ways that support motivation, engagement, and feelings of connection and belonging (Beecher & Sweeney, 2008; Callahan et al., 2015; van Kraayenoord, 2007; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). These complementary frameworks apply to all students and define general, flexible classroom practices that also reduce the need for individualised adjustments for students with identified disabilities and specialised learning needs. However, in inclusive classrooms, teachers must also develop the knowledge and skills to make and implement reasonable adjustments and accommodations that enable students with identified disabilities and more complex needs to engage with curriculum and assessment ‘on the same basis’ as their peers, as defined within the Disability Standards for Education (Davies et al., 2016).

While inclusive teaching and classroom practices are non-negotiable, the challenge for some teachers to master the necessary skills and achieve the significant shift away from traditional teaching practices is often underestimated (Dixon et al., 2014; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). It is well-documented that teachers often find it difficult to apprehend both the conceptual and practical tools of DI and to embed differentiated practices into their daily work (Dack, 2019), particularly when they are not adequately resourced or supported to do so (Black-Hawkins & Florian, 2012; Brigandi et al., 2019; Fuchs et al., 2010; Mills et al, 2014). Perhaps related to teachers’ perceived lack of competence and confidence, the past 5-10 years have seen an enormous increase in the employment of teacher aides to work alongside students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms, despite limited evidence for its effectiveness and often in the context of inadequate planning and oversight (e.g., Sharma & Salend, 2016).

Engagement in targeted professional learning (PL) is fundamental to supporting the shift towards inclusive teaching. Yet, traditional approaches to PL have been criticised for a lack of systematic evaluation and inadequate adherence to principles of effectiveness (Avalos, 2011; Merchie et al., 2018). Research on effective professional learning for teachers has established common principles and practices that are associated with changes in practice, and these also align with teachers’ stated preferences (Walker et al., 2018). These include:

- professional learning is embedded in teachers’ own work contexts, and requires teachers to engage with content that is highly relevant to their daily practice, and closely linked to student learning (Desimone, 2009; Easton, 2008; Spencer, 2016; Van den Bergh et al., 2014);

- professional learning enables teachers to learn together with colleagues, such as in communities of practice (Gore et al., 2017; Voelkel & Chrispeels, 2017);

- professional learning activities are supported by robust school leadership and linked to broader school values and goals (Carpenter, 2015; Frankling et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2020; Tomlinson et al., 2008; Whitworth & Chiu, 2015);

- professional learning is provided over extended periods, is led by facilitators with expert knowledge, and includes timely follow up activities such as mentoring and coaching to embed changes in practice (Desimone & Pak, 2017; Grierson & Woloshyn, 2013; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015).

Multi-tiered Approaches to Whole School Inclusive Practice

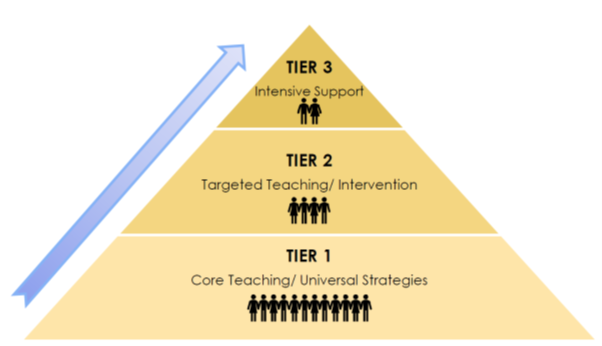

Multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) is an overarching term for a whole school inclusive framework that can be used to structure the flexible, timely distribution of resources to support students depending on their level of need (Sailor, 2017). As reflected in the generic depiction of MTSS in Figure 2, models generally utilise three tiers of intervention and teaching, where the intensity of the support is increased with each level or tier (McLeskey et al, 2014; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). Tier 1 includes core differentiated instruction and universal, evidence-based strategies for support that all students in the class receive. Tier 2 provides additional, targeted support to certain students for a specified purpose and period of time, usually in a small group format, while Tier 3 represents the most intensive and individualised support (Webster, 2016). The MTSS approach requires assessing all students regularly to assist in the early identification of needs requiring additional support, to enable prompt delivery of targeted interventions (McLeskey et al., 2014). MTSS is concerned with supporting the holistic development of students, by targeting their academic progress, behaviour, and socio-emotional well- being (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017).

When implemented with fidelity, MTSS is an effective whole school inclusive framework as teachers, therapists, and other support staff work collaboratively to assess, monitor, and plan interventions to support students (Sailor, 2017). Student progress is frequently monitored and data are evaluated by the support team to determine whether alternative interventions are required. MTSS additionally encourages the use of evidence-based practices to be implemented across the tiers of support. Some common examples of MTSS include Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behaviour Interventions and Supports (PBIS) (Webster, 2016). RTI is focused on supporting students academically, while PBIS is concerned with emphasising behavioural expectations in a positive manner, naturally supporting the social and emotional development of students. MTSS models have also been applied in whole-school mental health promotion, prevention and intervention (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017) and inclusive approaches to academic talent development for more advanced students (Jarvis, 2017).

MTSS approaches to contemporary inclusive practice stand in contrast to traditional, categorical models whereby students were either ‘in’ or ‘out’ of special education services. The focus is on determining and responding to what students need when they need it, as opposed to focusing on a specific diagnosis or inflexible program options. In the MTSS framework, the tiers do not represent students or their placement, but the flexible suite of supports and interventions that may be provided. The implementation of MTSS approaches fundamentally reconceptualises the role of the classroom teacher, who must work collaboratively with specialist staff and other professionals to define and address individual student needs in ongoing ways, rather than relying on a specialist teacher or even a teacher aide to take responsibility for the education of students with identified special needs. While MTSS requires substantial changes to school operations (and must therefore be supported by leadership and culture in deliberate, coordinated ways), the general framework provides an organisation and structure to support the development of sustainable, contemporary inclusive schools (McLeskey et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework.

Conclusion

Ultimately, developing sustainable and effective inclusion in schools is a challenging but worthwhile undertaking, requiring shared vision, commitment, ongoing reflection, and patience. Changes in practice, particularly in teachers’ daily planning and pedagogy, take time and will be supported by ongoing, well designed and embedded professional learning in the context of strong leadership and an inclusive school culture. By utilising a whole school approach, key areas including leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and coordinated frameworks for inclusive practice, can be considered collectively and planned for in advance.

References

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organizational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. Routledge.

Alborno, N., & Gaad, E. (2014). Index for Inclusion: A framework for school review in the United Arab Emirates. British Journal of Special Education, 41 (3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12073

Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2015). Inclusive education in Australia: Rhetoric, reality and the road ahead. Support for Learning, 30 (1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12074

Ashby, C. (2012). Disability studies and inclusive teacher preparation: A socially just path for teacher education. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37 (2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F154079691203700204

Ashton, J. R., & Arlington, H. (2019). My fears were irrational: Transforming conceptions of disability in teacher education through service learning. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 15 (1), 50–81.

Askell-Williams, H., & Koh, G. (2020). Enhancing the sustainability of school improvement initiatives. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1767657

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

Beecher, M., & Sweeney, S. M. (2008). Closing the achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19 (3), 502–530. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-815

Berlach, R. G., & Chambers, D. J. (2011). Interpreting inclusivity: An endeavour of great proportions. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903159300

Black-Hawkins, K. & Florian, L. (2012). Classroom teachers’ craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8 (5), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709732

Booth, T. (2012). Creating welcoming cultures: The index for inclusion. Race Equality Teaching, 30 (2), 19–21. http://doi.org/10.18546/RET.30.2.07

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2011). Index for Inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools (3rd ed.). Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. http://www.csie.org.uk/resources/inclusion-index-explained.shtml

Brigandi, C., Gibson, C. M., & Miller, M. (2019). Professional development and differentiated instruction in an elementary school pull-out program: A gifted education case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42 (4), 362–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219874418

Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Oh, S., Azano, A. P., & Hailey, E. P. (2015). What works in gifted education: Documenting the effects of an integrated curricular/instructional model for gifted students. American Education Research Journal, 52, 137–167. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214549448

Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29 (5), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0046

Carrington, S., & Elkins, J. (2002). Bridging the gap between inclusive policy and inclusive culture in secondary schools. Support for Learning, 17 (2), 51–57.

Carter, S., & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.5

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Davies, M., Elliott, S., & Cumming, J. (2016). Documenting support needs and adjustment gaps for students with disabilities: Teacher practices in Australian classrooms and on national tests. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (12), 1252–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1159256

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38 (3),181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice, 56 (1), 312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. A., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37 (2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353214529042

Dybvik, A. C. (2004). Autism and the inclusion mandate: What happens when children with severe disabilities like autism are taught in regular classrooms? Daniel knows. Education Next, 4 (1), 42–49.

Dyson, A., Farrell, P., Polat, F., Hutcheson, G., & Gallanaugh, F. (2004). Inclusion and pupil achievement. Department for Education and Skills.

Easton, L. B. (2008). From professional development to professional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 89, 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170808901014

Ekins, A., & Grimes, P. (2009). Inclusion: Developing an Effective Whole School Approach. McGraw Hill Open University Press.

Forlin, C. (2006). Inclusive education in Australia ten years after Salamanca. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21 (3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173415

Forlin, C., & Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: Increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39 (1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850

Forlin, C., Chambers, D. J., Loreman, T., Deppler, J., & Sharma, U. (2013). Inclusive education for students with disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice. The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. https://www.aracy.org.au/publicationsresources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf73

Forlin, C., Keen, M., & Barrett. E. (2008). The concerns of mainstream teachers: Coping with inclusivity in an Australian context. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55 (3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120802268396

Frankling, T. W., Jarvis, J. M. & Bell. M. R. (2017). Leading secondary teachers’ understandings and practices of differentiation through professional learning. Leading and Managing, 23 (2), 72–86.

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Stecker, P. M. (2010). The ‘blurring’ of special education in a new continuum of general education placements and services. Exceptional Children, 76 (3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600304

Gore, J., Lloyd, A., Smith, M., Bowe, J., Ellis, H., & Lubans, D. (2017). Effects of professional development on the quality of teaching: Results from a randomised controlled trial of Quality Teaching Rounds. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.007

Graham, L., & Spandagou, I. (2011). From vision to reality: Views of primary school principals on inclusive education in New South Wales, Australia. Disability & Society, 26 (2), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.544062

Grierson, A. L., & Woloshyn, V. E. (2013). Walking the talk: Supporting teachers’ growth with differentiated professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 39 (3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.763143

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press

Harris, A. (2013). Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 4 (5), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635

Hehir, T., Pascucci, S., & Pascucci, C. (2016). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education, Instituto Alana, 2. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596134.pdf

Horrocks, J. L., White, G., & Roberts, L. (2008). Principals' attitudes regarding inclusion of children with autism in Pennsylvania public schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1462–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0522-x

Jarvis, J. M. (2015). Inclusive Classrooms and Differentiation. In N. Weatherby-Fell (Ed.), Learning to Teach in the Secondary School (pp. 154–171). Cambridge University Press.

Jarvis, J. M. (2019). Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/most-australian-teachers-feel-unpreparedto-teach-students-with-special-needs-119227

Jarvis, J. M., (2017). Supporting diverse gifted students. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, Inclusion and Engagement (3rd ed., pp. 308–329). Oxford University Press.

Johnston, K., & Hayes, D. (2007). Supporting students’ success at school through teacher professional learning: The pedagogy of disrupting the default modes of schooling. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11 (3), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701240666

Kinsella, W. (2020). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (12), 1340–1356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1516820

Kozik, P., Cooney, B., Vinciguerra, S., Gradel, K., & Black, J. (2009). Promoting inclusion in secondary schools through appreciative inquiry. American Secondary Education, 38 (1), 77–91.

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Spooner, F., & Algozzine, B. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of effective inclusive schools: Research and practice. Taylor & Francis.

McMaster, C. (2013). Building inclusion from the ground up: A review of whole school re-culturing programmes for sustaining inclusive change. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 9 (2), 1–24.

McMaster, C. (2015). Inclusion in New Zealand: The potential and possibilities of sustainable inclusive change through utilising a framework for whole school development. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50 (2), 239–253.

McMaster, C., & Elliot, W. (2014). Leading inclusive change with the Index for Inclusion: Using a framework to manage sustainable professional development. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 29 (1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0010-3

McMillan, J., & Jarvis, J. M. (2017). Supporting mental health and well-being: Promotion, prevention and intervention. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, inclusion and engagement (3rd ed., pp. 65–392). Oxford University Press.

Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33 (2), 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271003

Mills, M., Monk, S., Keddie, A., Renshaw, P., Christie, P., Geelan, D. & C. Gowlett, C. (2014). Differentiated learning: From policy to classroom. Oxford Review of Education, 40 (3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.911725

Miškolci, J., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2016). Teachers' perceptions of the relationship between inclusive education and distributed leadership in two primary schools in Slovakia and New South Wales (Australia). Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18 (2), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-001

Mullick, J., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2013). School teachers' perception about distributed leadership practices for inclusive education in primary schools in Bangladesh. School Leadership & Management, 33 (2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.723615

OECD (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

Parliament of South Australia. (2017). Report of the select committee on access to the South Australian Education System for students with a disability. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid94396.pdf

Poon-McBrayer, K., & Wong, P. (2013). Inclusive education services for children and youth with disabilities: Values, roles and challenges of school leaders. Children and Youth Services Review, 35 (9), 1520–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.06.009

Read, K., Aldridge, J., Ala’i, K., Fraser, B., & Fozdar, F. (2015). Creating a climate in which students can flourish: A whole school intercultural approach. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 11 (2), 29–44. https://doi.org/1710-2146

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. (2019). Issues Paper: Education and Learning. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-07/Issues-paper-Education-Learning.pdf

Sailor, W. (2015). Advances in schoolwide inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 36, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514555021

Sailor, W. (2017). Equity as a basis for inclusive educational systems change. The Australasian Journal of Special Education, 41 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.12

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Sharma, U., & Salend, S. (2016). Teaching assistants in inclusive classrooms: A systematic analysis of the international research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (8), 118–134.

Sharp, K., Jarvis, J. M., & McMillan, J. M. (2020). Leadership for differentiated instruction: Teachers' engagement with on-site professional learning at an Australian secondary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (8), 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1492639

Skidmore, D. (2004). Inclusion: The dynamic of school development. McGraw-Hill Education.

Slater, C. L. (2012). Understanding principal leadership: An international perspective and a narrative approach. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39 (2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210390061

Slee, R. (2013). How do we make inclusive education happen when exclusion is a political predisposition? International Journal of Inclusive Education: Making Inclusive Education Happen: Ideas for Sustainable Change, 17 (8), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.602534

Spencer, E. J. (2016). Professional learning communities: Keeping the focus on instructional practice. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 52 (2), 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2016.1156544

Stegemann, K., & Jaciw, A. (2018). Making it logical: Implementation of inclusive education using a logic model framework. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16 (1), 3–18.

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2011). School factors that facilitate or hinder the ability of teaching assistants to effectively support pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11 (3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01196.x

Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.652070

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Murphy, M. (2015). Leading for differentiation: Growing teachers who grow kids. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A., Brimijoin, K., & Narvaez, L. (2008). The differentiated school: Making revolutionary changes in teaching and learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Van Den Bergh, L., Ros, A., & Beijaard, D. (2014). Improving teacher feedback during active learning: Effects of a professional development program. American Educational Research Journal, 51 (4), 772–809. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531322

van Kraayenoord, C. E. (2007). School and classroom practices in inclusive education in Australia. Childhood Education, 83 (6), 390–394, https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2007.10522957

van Kraayenoord, C. E., Waterworth, D., & Brady. T. (2014). Responding to individual differences in inclusive classrooms in Australia. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 17 (2), 48–59.

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26 (6), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

Voelkel, R. H., Jr., & Chrispeels, J. H. (2017). Understanding the link between professional learning communities and teacher collective efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28, 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1299015

Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83 (3), 319–356. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483905

Walker, P. M., Carson, K. L., Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Noble, A. G., Armstrong, D., . . . Palmer, C. (2018). How do educators of students with disabilities in specialist settings understand and apply the Australian Curriculum framework? Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.13

Webster, A. (2016). Utilising a leadership blueprint to build the capacity of schools to achieve outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. In G. Johnson & N. Dempster (Eds.), Leadership in diverse learning contexts (pp. 109–127). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28302-9_6

Whitworth, B. A., & Chiu, J. L. (2015). Professional development and teacher change: The missing leadership link. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26 (2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9411-2

Inclusive School Communities Project Phone: (08) 8373 8333 Email: [email protected] Address: 104 Greenhill Road, Unley SA 5061

- Conferences

- Virtual Library

- Editorial Board Member

- Write For Us

- April 26, 2021

- Posted by: rsispostadmin

- Category: IJRISS

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) | Volume V, Issue III, March 2021 | ISSN 2454–6186

Inclusive Education: A Literature Review on Definitions, Attitudes and Pedagogical Challenges

Tebatso Namanyane, Md Mirajur Rhaman Shaoan Faculty of Education Southwest University China

Abstract: This paper on inclusive education explores several diverse viewpoints from various scholars in different contexts on the concepts of inclusive education in an effort to reach the common understanding of the same this concept. The attitudes section is addressed from the perspectives of pupils, educators, and the society (parents), and it further explore the dilemmas that teachers and students with disabilities face in modern education systems. The instructional approaches focusing on how teachers plan and execute lessons with diverse students’ aptitudes from literature are also levelheadedly outlined. In conclusion, it included a broad overview focused on two models, social and medical models on which this paper is primarily based.

Key words: Inclusive Education, Attitudes, Pedagogical Challenges

I. INTRODUCTION There are several terms in the field of education that are interpreted differently depending on the reason for which they are meant. Others have been given meanings that are globally recognized, while others are interpreted differently based on the varying reasons and factors affecting them, including religion and regions, history, values, race, and resource limitations. The present paper is intended to discuss an interesting educational topic which has intrigued scholars across the globe due to its arguable definitions from different perspectives. It will also have a more comprehensive but remarkably different interpretation of these core tenets as proposed in the topic specified above, Inclusive Education: A Literature Review on Definitions, Attitudes and Pedagogical Challenges. Education is a full process of training a new generation who is ready to participate in civic life and is also a vital link in the process of human social production experience to be carried out, with special regard to the process of school education for school-age infants, young people and retired people. Generally, all things that will improve human intelligence and skills and affect people’s moral character as considered as part of education. In a narrow sense, it is primarily schooling, which is characterized as the practice of educators to impact the mind and body of the learner intentionally, purposefully and systematically according to the requirements of a specific community or class to develop them as persons they want to be. Aristotle defines education as the way to prepare a man to achieve his mission by exercising all the faculties to the fullest degree as a citizen of society.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Dev Disabil

- v.69(5); 2023

- PMC10402840

Parent perspectives on inclusive education for students with intellectual disability: A scoping review of the literature

Jordan shurr.

1 Faculty of Education, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Alexandra Minuk

Mona holmqvist.

2 Educational Sciences, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

Daniel Östlund

3 Faculty of Education, Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden

Nehal Ghaith

Brenda reed, associated data.

The aim of this study was to collect and analyze research on inclusive education from the perspective of parents of students with intellectual disability (ID). The review examined characteristics and trends related to geographical origin of research, design, data collection, publication source and year, source of data, age of individuals with ID, and research focus. The initial database search produced a total of 2,540 non-duplicated articles published between 1994 and 2019. In total, 63 articles were included from the initial search and a subsequent ancestry search. The results show a significant increase in publication on the topic in the final one-tenth of the review time parameter, suggesting a continued upward trend. The majority of articles were qualitative in design, used interviews and surveys to collect data, and focus on the perspectives and beliefs of parents on inclusive education. Gaps in the existing set of research included a lack of family perspectives beyond that of mothers (e.g. father, grandparent) and a limited focus beyond perspectives and beliefs, to that of parent experiences of inclusive education.

Inclusive education (IE) has been a topic of intense interest and some debate for the past few decades. While the term can refer to welcoming all students by removing barriers to full access and participation (e.g. Ainscow et al. 2006 , Brooks et al. 2010 , Kugelmass 2004 ), it originally linked to school reform focused on increasing access for students with disabilities (Winzer 2002 ). Both terminology and conception of IE has evolved over the years and has been described in three phases, beginning in the 1970s and shifting every few decades (Ryndak et al. 2013 , Wehmeyer 2006 ). This includes an initial focus on place—that is students with disabilities being educated in the same location as those without. The second phase centers on instruction, specifically including advances in the science and use of effective strategies for teaching students with disabilities. And, the third phase of evolution puts the focus on access to appropriately challenging educational content at the forefront of IE (Ryndak et al. 2013 , Wehmeyer 2006 ).

Today there seems to be a mix of the three historical phases with simultaneous IE discussion and debate on place, instructional methods, and appropriate content (Brock 2018 , Klang et al. 2020 ). Furthermore, differences in definitions and expectations related to IE exist across relevant stakeholders such as policy makers, parents, students, and school personnel (Kraska, and Boyle 2014 , Krischler et al. 2019 , Lüke and Grosche 2018 , Norwich 2014 , Pellicano et al. 2018 , Waitoller and Artilles 2013 , Williams et al. 2019 ). In a review of inclusion-focused literature, Nilholm and Göransson ( 2017 ) found that definitions, while not always explicit nor consistent, fit within one of four categories including: educational placement in a general education classroom, social and academic support for students with disabilities in general education placement, social and academic support for all students, and creation of a community around shared values. In addition, they found that empirical research was most often focused on the placement-centered definition, while position papers on IE typically used one of the other three definitions (Nilholm and Göransson 2017 ).

Further reviews of research on inclusive education have found a general focus on theoretical and position-oriented papers with less focused on intervention-related research (Amor et al. 2019 , Nilholm and Göransson 2017 ). IE is indeed a topic of global interest across multiple fields and covers four main topics including: teachers and schools, students with disabilities, a combination of the two, and issues of policy and social justice (Hernández-Torrano et al. 2020 ). While the concept of IE has, in general terms, garnered more consensus in relation to students with high incidence disabilities, the status for students with more significant support needs such as intellectual disability (ID) is much more disparate (Colley 2020 , Dukes and Berlingo 2020 , Norwich 2014 ).

Though students with ID are still largely educated in specialized, or non-inclusive, environments (Wehmeyer et al. 2021 ), research on academic content in the general education environment has been increasing, albeit still minimal (Dell’Anna et al. 2020 , Hudson and Browder 2014 , Shurr and Bouck 2013 ). Noteworthy, is the emerging evidence that inclusive environments can be linked to increased instructional time as well as access to and engagement with high level academic content (Dell’Anna et al. 2020 , Wehmeyer et al. 2021 ). However, stakeholders do not always agree on the most appropriate educational setting nor content for this population of students (Ayres et al. 2011 , Göransson et al. 2020 , Petersen 2016 ).

While previous reviews of research have described the existing knowledge on curriculum, location, and supports related to IE for students with ID (Amor et al. 2019 , Becht et al. 2020 , Shurr and Bouck 2013 ), none have yet consolidated the perspectives on IE of parents. Families are known to be essential in the education—specifically in school-home partnerships as well as intervention carryover and consistency (Goldman and Burke 2017 ). Also, parent background often differs significantly to that of the professionals who work in education (Kurth et al. 2019 ). In a review of research on IE for students with autism, researchers found some differences of opinion and evaluation of supports and inclusive activities provided to students across different stakeholders (i.e. parents, educators, individuals with autism; Roberts and Simpson 2016 ). Parents of individuals with intellectual disability often enter the field of advocacy and support by necessity of raising their children, whereas professionals deliberately choose the field and often receive pre-service and in-service training. Additionally, in contrast to parents, teachers generally have regular connection to others in the same field to continually sharpen and deepen their understanding and practice (Foster et al. 2014 , Kurth et al. 2019 ).

Multiple stakeholder perspective in IE is of critical importance. This study addresses the current gap in research summarizing the perspective of parents of students with ID regarding IE. While not a fulsome description of the summative research findings, a scoping review of this literature can illuminate the trends and gaps in the research in an effort to understand the current knowledge base and determine directions for future research (Pham et al. 2014 ). This study collected and analyzed research on IE from the perspective of parents of students with intellectual disability from the signing of the Salamanca Statement regarding education for all (Ainscow et al. 2019 ) in 1994 until 2019. Specifically, the research purpose entailed identification and analysis of the key characteristics of research on this topic including: geographical origin, design, data collection measure, publication source and year, data source, age of individuals with ID, and research aim.

Using three databases and an ancestry search, this scoping review, based on processes described by Peters et al. ( 2015 ), identified and described the past 26 years of research on parent perspectives of IE for students with intellectual disability. After conducting the initial database search with relevant keywords, each article was manually reviewed for inclusion or exclusion with specific criteria related to the topic. Additional articles were then identified through an ancestry search of included articles from the database search. All articles were systematically categorized according to several dimensions including geographic origin, publication year and source, data source, research design, data collection measure, student age, and article focus.

Electronic database search

Initial articles were produced through electronic searches in three different databases: ERIC, PsycNet, and Web of Science. ERIC, also known as Education Resources Information Center, was chosen for its focus on education and access to a wide variety of academic journals. In addition to researchers and policymakers, ERIC lists the general public as one of its main user groups, making it a suitable choice for parent-focused research. The American Psychological Association’s PsycNet served as another source of education research while Web of Science was chosen for its ability to search interdisciplinary databases simultaneously.

The search was conducted between December 2019–January 2020 and included a restricted span of 26 years from 1994–2019. The authors developed four key word search strings representing each of the major themes of focus: IE, perspectives, family, and intellectual disability. Each string relied on Boolean operators (e.g. OR) and modifiers (e.g. *) to ensure the search efficiency in each of the major themes. The first search string, which pertained to IE, involved key words that would return results related to the school setting: inclus* OR mainstream* OR educat* OR school* OR class* OR teach* OR learn*. The second search string, which was focused on perspectives, used the key words: attitud* OR percept* or perspective* OR opinion* OR view* OR experienc*. The third search string, which further narrowed the focus to families, included: parent* OR paternal* OR maternal* OR mother* OR father* OR caregiver* OR guardian* OR famil* OR brother* OR sister* OR sibling* OR grandparent* OR grandmother* OR grandfather*. The fourth and final string of search terms focused on the population of interest, students with intellectual disability, and included: “intellectual disabilit*” OR “mental retardation” OR “Down syndrome” OR “Fragile X” OR “developmental disability”. For the final string, each term was enclosed in quotation marks to return results that were relevant to the entire phrase rather than the individual words. In each database, the limitations were set to retrieve only peer-reviewed articles published in English. In ERIC and PsycNet, abstracts were searched for keyterms , whereas in Web of Science, topic (i.e. abstract and author key words) was searched. Once the search was complete, results from each database were uploaded into Covidence ( https://www.covidence.org/ ) for storage and analysis. Once uploaded, articles were automatically screened for duplicates and each match was manually confirmed by a member of the research team resulting in a consolidated array of articles from each of the three database searches.

Inclusion and exclusion determination

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created to set clear boundaries of article relevance to the topic and subsequent inclusion in the final data set. Researchers initially reviewed the title and abstract of each database-identified article. Articles which met the all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were classified as included articles. If review of the title and abstract did not clearly indicate inclusion or exclusion, researchers examined the articles full text to make the determination. Initially, to build consistency of the inclusion review, the research team independently screened the same 30 articles and collaboratively refined the inclusion and exclusion criteria for clarity and utility. Following this step, articles were divided among the research team to review for inclusion.

Articles were included if they (a) had an IE or school-based focus, (b) described the perspectives or experiences of parents or family, and (c) at least 50% of the study population were students with intellectual disability, with or without another diagnosis. Articles were excluded if they were (a) not school-based nor about school-aged children (i.e. older than 21), (b) solely focused on transition or community programs, (c) medically focused, (d) exclusive of family member perspectives, (e) focused on parent perspectives of children without disabilities, (f) not primarily focused on intellectual disability (i.e. less than 50% of participants or their families), or (g) considered grey literature (e.g. government publications).

Ancestry search

In order to locate articles missed in the database search, the complete reference list of each included article was reviewed. Titles that suggested adherence to the main themes were compiled and the corresponding articles were searched by title and abstract, as well as full text when necessary, for inclusion. Articles that met inclusion criteria were added to the existing list of previously included articles.

Categorization

Following selection for inclusion, the first author categorized each article according to the location of study, year of publication, journal of publication, research design, data collection measure, data source, student grade, and research aim. Consensus on the distinctive labels within each category was achieved through initial discussion amongst authors and refinement within the research team prior to use.

Geographical region, year, and journal

Geographical region referred to the global location of data collection or article focus. Regions included Europe, North America, the Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, South America, and Australia. Year and publication source was recorded as both the date, (i.e. between 1994–2019) and name of the journal.

Research design and data collection measure

Articles were also classified by general research design, defined as: qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, literature review or position paper. Further review determined the data collection measures and tools utilized. The categories included: document analysis, existing data set, observation or field notes, interview, focus group, survey, questionnaires, rating scales, and not applicable (e.g. position paper).

Data source and student age

While the focus of the study was parent perspectives, the data source category was created for studies that contained multi-perspective data (e.g. parents and grandparents), or that assumed the parent perspective from other sources, such as teachers. Given that the terms ‘mother’ and ‘father’ do not necessarily represent all parents, multiple familial categories were used including: unspecified parent, mother, father, legal guardian, sibling, or grandparent. As for the age of students with intellectual disability, who were either indirectly or directly involved in the research, the four possible classifications included: primary (Kindergarten to Grade 8 or age 4-14), secondary (Grade 9 to Grade 12 or age 15-18), post-secondary (Grade 12 and above or age 19-21), and unclear or unspecified. Students older than 18 and past grade 12 were included as an acknowledgement of extended age limits in secondary education for many students with ID (e.g. IDEA 2004, O. Reg. 181/98).

Research aims

The research aims of each article were identified by extracting the verbatim research questions or stated research purpose or objectives, if no explicit questions were noted. Each aim was then analyzed and coded for themes using an inductive, open-coding approach. The first and second authors independently coded the aims of all articles and then collaboratively developed emergent themes. This resulted in identification of three main themes: experiences in IE (i.e. related to parent account or discussion of experience and efforts related to inclusive education systems and processes), perspectives and beliefs on IE (i.e. related to parent feelings—views, attitudes, and personal understanding of inclusive education), and relevant factors (i.e. related to variables which influence inclusive education in some way other than parent perspectives and beliefs). Examples include a study focused on the experiences of families discussing the transition from school to post-school life (i.e. experiences), an exploration of attitudes held by teachers and parents on IE (i.e. perspectives and beliefs), and an investigation of the impact of a parent support group on IE (i.e. related factors). Several sub-themes emerged within each category, a breakdown of which can be found in the results section.

Reliability

Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was assessed for inclusion determinations of a randomly selected 30% ( n = 762) of the database articles by the first author. Using the simple measure of reliability, (agreements/(agreements + disagreements)) x 100), IRR for inclusion was 98.56%. Reliability for categorization was assessed by the second author for 41% ( n = 26) of included articles, both database and ancestry articles, in all categories other than research aim. IRR for categorization included 100% on geographical region, 96% on general research design, 96% on data collection, 92% on data source, and 92% on age of students with intellectual disability. All disagreements were resolved by the first author. For the research aims, trustworthiness of the results was established through ongoing discussion during the review process and careful classification of each article.

The initial database search produced a total of 2,540 non-duplicated articles across the 26-year span. Database yields, with duplications across platforms, included 322 from ERIC, 701 from PsycNet, and 1773 from Web of Science. Of the 2,540 articles that appeared in the database search, 48 met the inclusion criteria. The following ancestry search yielded an additional 15 articles for a grand total of 63 included articles (see Figure 1 ).

Article search and inclusion process and results.

Geographical region

The included research spanned across 19 countries and six of the seven of the geographic regions identified. Almost half (44%) of all included articles originated from North America, followed by 25% from Europe, 16% from Australia, 8% from North Africa and the Middle East, and 2% from South America. The two most prevalent countries included the United States (41%) and Australia (16%). This was followed by 8% from England, an equal 5% from Ireland, and Greece and an equal 3% from Austria and Canada. The remaining 12 countries spread across geographical regions (i.e. Europe, Asia, South America, the and Middle East/North Africa,) with each representing 2% ( n = 1) of the included studies (see Table 1 ).

Categorization of included articles.

Note. Methods: MM = mixed methods, QN = quantitative, QL = qualitative, SL = systemic literature review, PP = position paper; Measure: SQR = survey, questionnaire, or rating scale, Int = interview, NA = not applicable, Obs = observation or field notes, Da = document analysis, Fg = focus group; Source (i.e. data source): PU = parent unspecified, M = mother, F = father, S = sibling, G = grandparent, U = unclear, O = other family member; Theme: EXP = Experience in inclusive education, PB = perspectives and beliefs on inclusive education, RF = related factors; Sub-themes: 1= EXP placement decision-making process, 2= EXP educational services and supports, 3= EXP parental involvement and advocacy, 4= PB placement decision-making process, 5= PB educational services and supports, 6= PB child needs and family desires and expectations, 7= RF facilitators and barriers for educational success 8= RF student characteristics, 9= RF family characteristics, 10= RF external variables. Full citation list is available at supplementary data .

Year of publication

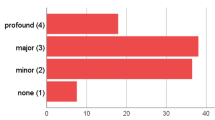

There was a steady period of publication between 1994 and 2016 with a range between 0 and 4 articles per year. The years 1994, 2002, 2011 and 2014 recorded zero published articles while four were produced in 1998, 1999, and 2015. Beginning in 2017, the number of articles published on the topic trended strongly upward to represent 32% ( n = 20 ) of all articles within the final one-tenth of the time parameter of this review (see Figure 2 ).

Number of inclusive education research articles published by theme per year.

Journal of publication

A total of 37 journals were represented in the included research from both inside and outside the field of special education. The four journals with the most articles included Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities (10%, n = 6 ), Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities (8%, n = 5 ), British Journal of Special Education (6%, n = 4 ), and Remedial and Special Education (6%, n = 4 ). Of the remaining journals, 4 had three included articles, 3 had two included articles, and the remaining 26 journals each had one included article.

More than half (51%) of the articles used a qualitative research design. Following in prevalence were quantitative research designs (32%), mixed methods (15%) and literature reviews (2%). More than half (52%) of the articles employed interviews as a data collection measure. Surveys, questionnaires, and rating scales were used in 49% of studies and, in mixed methods research, often accompanied interviews. Other methods of data collection included observation and field notes (8%) and focus groups (6%). Document analysis and literature reviews each represented 2% of the research. There were no studies that analyzed existing datasets (see Table 1 ).

Data source