Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Shona McCombes .

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more variables . An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls. A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Step 1: ask a question.

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2: Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalise more complex constructs.

Step 3: Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

Step 4: Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

Step 5: Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if … then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

Step 6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

A hypothesis is not just a guess. It should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations, and statistical analysis of data).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, May 06). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/hypothesis-writing/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, operationalisation | a guide with examples, pros & cons, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

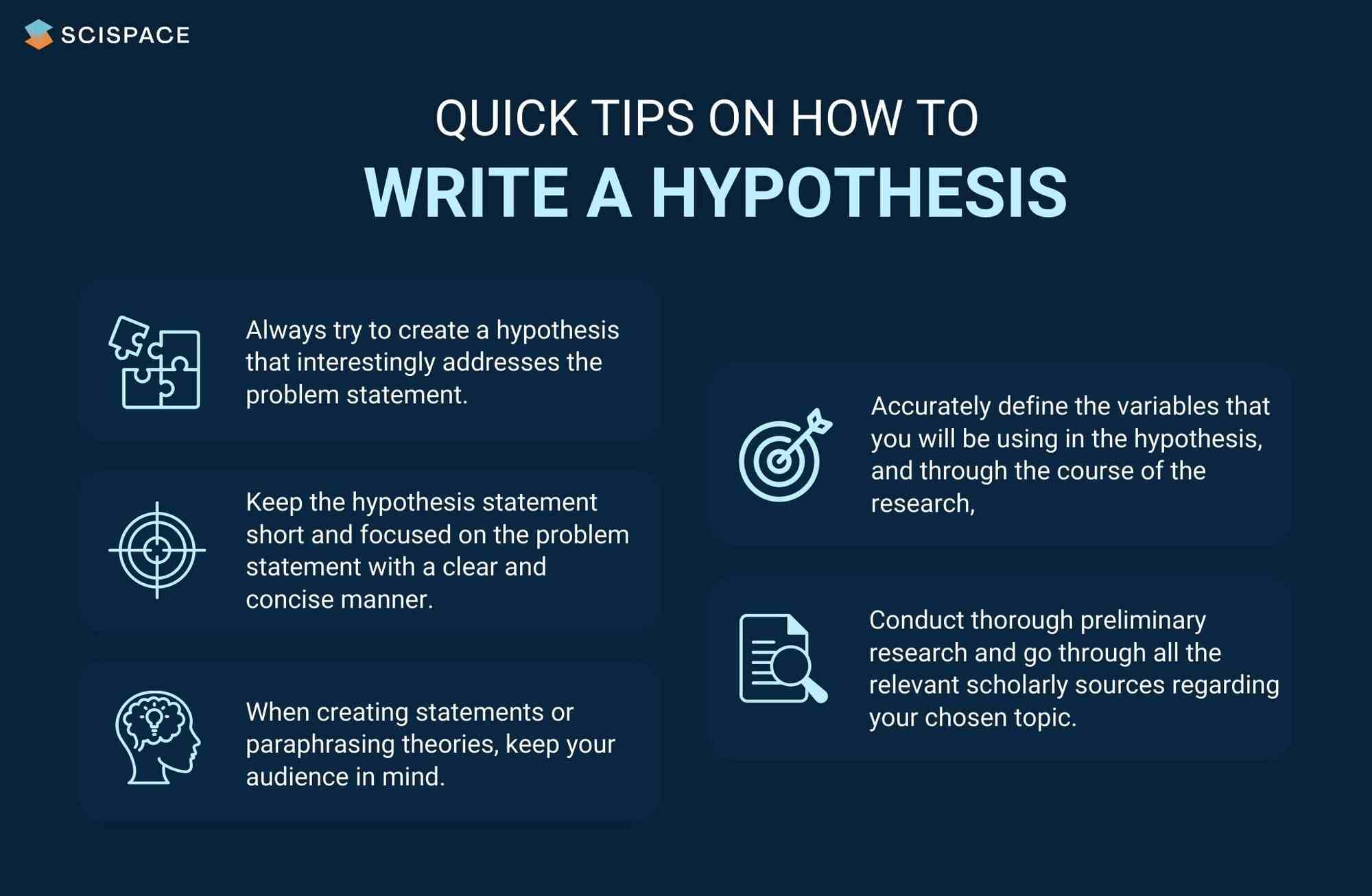

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

- 285.3K views

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

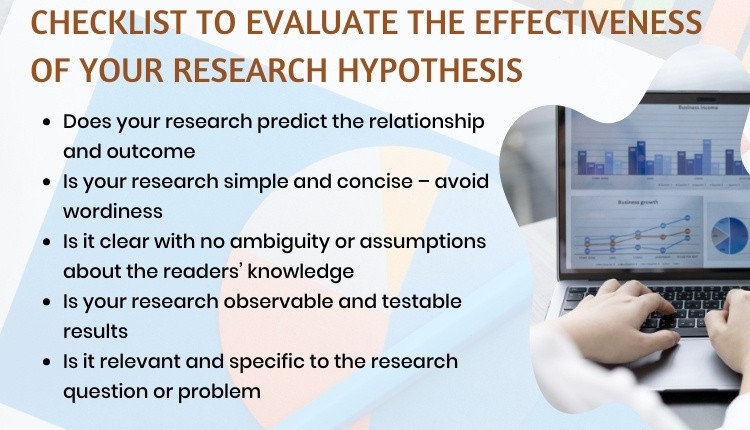

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?

The questions listed above can be used as a checklist to make sure your hypothesis is based on a solid foundation. Furthermore, it can help you identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary.

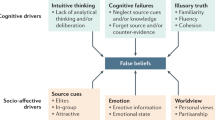

Source: Educational Hub

How to formulate a research hypothesis.

A testable hypothesis is not a simple statement. It is rather an intricate statement that needs to offer a clear introduction to a scientific experiment, its intentions, and the possible outcomes. However, there are some important things to consider when building a compelling hypothesis.

1. State the problem that you are trying to solve.

Make sure that the hypothesis clearly defines the topic and the focus of the experiment.

2. Try to write the hypothesis as an if-then statement.

Follow this template: If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.

3. Define the variables

Independent variables are the ones that are manipulated, controlled, or changed. Independent variables are isolated from other factors of the study.

Dependent variables , as the name suggests are dependent on other factors of the study. They are influenced by the change in independent variable.

4. Scrutinize the hypothesis

Evaluate assumptions, predictions, and evidence rigorously to refine your understanding.

Types of Research Hypothesis

The types of research hypothesis are stated below:

1. Simple Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable.

2. Complex Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables.

3. Directional Hypothesis

It specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables and is derived from theory. Furthermore, it implies the researcher’s intellectual commitment to a particular outcome.

4. Non-directional Hypothesis

It does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. The non-directional hypothesis is used when there is no theory involved or when findings contradict previous research.

5. Associative and Causal Hypothesis

The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables. A change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. On the other hand, the causal hypothesis proposes an effect on the dependent due to manipulation of the independent variable.

6. Null Hypothesis

Null hypothesis states a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. There will be no changes in the dependent variable due the manipulation of the independent variable. Furthermore, it states results are due to chance and are not significant in terms of supporting the idea being investigated.

7. Alternative Hypothesis

It states that there is a relationship between the two variables of the study and that the results are significant to the research topic. An experimental hypothesis predicts what changes will take place in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated. Also, it states that the results are not due to chance and that they are significant in terms of supporting the theory being investigated.

Research Hypothesis Examples of Independent and Dependent Variables

Research Hypothesis Example 1 The greater number of coal plants in a region (independent variable) increases water pollution (dependent variable). If you change the independent variable (building more coal factories), it will change the dependent variable (amount of water pollution).

Research Hypothesis Example 2 What is the effect of diet or regular soda (independent variable) on blood sugar levels (dependent variable)? If you change the independent variable (the type of soda you consume), it will change the dependent variable (blood sugar levels)

You should not ignore the importance of the above steps. The validity of your experiment and its results rely on a robust testable hypothesis. Developing a strong testable hypothesis has few advantages, it compels us to think intensely and specifically about the outcomes of a study. Consequently, it enables us to understand the implication of the question and the different variables involved in the study. Furthermore, it helps us to make precise predictions based on prior research. Hence, forming a hypothesis would be of great value to the research. Here are some good examples of testable hypotheses.

More importantly, you need to build a robust testable research hypothesis for your scientific experiments. A testable hypothesis is a hypothesis that can be proved or disproved as a result of experimentation.

Importance of a Testable Hypothesis

To devise and perform an experiment using scientific method, you need to make sure that your hypothesis is testable. To be considered testable, some essential criteria must be met:

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is true.

- There must be a possibility to prove that the hypothesis is false.

- The results of the hypothesis must be reproducible.

Without these criteria, the hypothesis and the results will be vague. As a result, the experiment will not prove or disprove anything significant.

What are your experiences with building hypotheses for scientific experiments? What challenges did you face? How did you overcome these challenges? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section.

Frequently Asked Questions

The steps to write a research hypothesis are: 1. Stating the problem: Ensure that the hypothesis defines the research problem 2. Writing a hypothesis as an 'if-then' statement: Include the action and the expected outcome of your study by following a ‘if-then’ structure. 3. Defining the variables: Define the variables as Dependent or Independent based on their dependency to other factors. 4. Scrutinizing the hypothesis: Identify the type of your hypothesis

Hypothesis testing is a statistical tool which is used to make inferences about a population data to draw conclusions for a particular hypothesis.

Hypothesis in statistics is a formal statement about the nature of a population within a structured framework of a statistical model. It is used to test an existing hypothesis by studying a population.

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It forms the basis of scientific experiments.

The different types of hypothesis in research are: • Null hypothesis: Null hypothesis is a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. • Alternate hypothesis: Alternate hypothesis predicts the relationship between the two variables of the study. • Directional hypothesis: Directional hypothesis specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables. • Non-directional hypothesis: Non-directional hypothesis does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. • Simple hypothesis: Simple hypothesis predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable. • Complex hypothesis: Complex hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Associative and casual hypothesis: Associative and casual hypothesis predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables. • Empirical hypothesis: Empirical hypothesis can be tested via experiments and observation. • Statistical hypothesis: A statistical hypothesis utilizes statistical models to draw conclusions about broader populations.

Wow! You really simplified your explanation that even dummies would find it easy to comprehend. Thank you so much.

Thanks a lot for your valuable guidance.

I enjoy reading the post. Hypotheses are actually an intrinsic part in a study. It bridges the research question and the methodology of the study.

Useful piece!

This is awesome.Wow.

It very interesting to read the topic, can you guide me any specific example of hypothesis process establish throw the Demand and supply of the specific product in market

Nicely explained

It is really a useful for me Kindly give some examples of hypothesis

It was a well explained content ,can you please give me an example with the null and alternative hypothesis illustrated

clear and concise. thanks.

So Good so Amazing

Good to learn

Thanks a lot for explaining to my level of understanding

Explained well and in simple terms. Quick read! Thank you

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Industry News

COPE Forum Discussion Highlights Challenges and Urges Clarity in Institutional Authorship Standards

The COPE forum discussion held in December 2023 initiated with a fundamental question — is…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

How to Design Effective Research Questionnaires for Robust Findings

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Scientific Reports

What this handout is about.

This handout provides a general guide to writing reports about scientific research you’ve performed. In addition to describing the conventional rules about the format and content of a lab report, we’ll also attempt to convey why these rules exist, so you’ll get a clearer, more dependable idea of how to approach this writing situation. Readers of this handout may also find our handout on writing in the sciences useful.

Background and pre-writing

Why do we write research reports.

You did an experiment or study for your science class, and now you have to write it up for your teacher to review. You feel that you understood the background sufficiently, designed and completed the study effectively, obtained useful data, and can use those data to draw conclusions about a scientific process or principle. But how exactly do you write all that? What is your teacher expecting to see?

To take some of the guesswork out of answering these questions, try to think beyond the classroom setting. In fact, you and your teacher are both part of a scientific community, and the people who participate in this community tend to share the same values. As long as you understand and respect these values, your writing will likely meet the expectations of your audience—including your teacher.

So why are you writing this research report? The practical answer is “Because the teacher assigned it,” but that’s classroom thinking. Generally speaking, people investigating some scientific hypothesis have a responsibility to the rest of the scientific world to report their findings, particularly if these findings add to or contradict previous ideas. The people reading such reports have two primary goals:

- They want to gather the information presented.

- They want to know that the findings are legitimate.

Your job as a writer, then, is to fulfill these two goals.

How do I do that?

Good question. Here is the basic format scientists have designed for research reports:

- Introduction

Methods and Materials

This format, sometimes called “IMRAD,” may take slightly different shapes depending on the discipline or audience; some ask you to include an abstract or separate section for the hypothesis, or call the Discussion section “Conclusions,” or change the order of the sections (some professional and academic journals require the Methods section to appear last). Overall, however, the IMRAD format was devised to represent a textual version of the scientific method.

The scientific method, you’ll probably recall, involves developing a hypothesis, testing it, and deciding whether your findings support the hypothesis. In essence, the format for a research report in the sciences mirrors the scientific method but fleshes out the process a little. Below, you’ll find a table that shows how each written section fits into the scientific method and what additional information it offers the reader.

Thinking of your research report as based on the scientific method, but elaborated in the ways described above, may help you to meet your audience’s expectations successfully. We’re going to proceed by explicitly connecting each section of the lab report to the scientific method, then explaining why and how you need to elaborate that section.

Although this handout takes each section in the order in which it should be presented in the final report, you may for practical reasons decide to compose sections in another order. For example, many writers find that composing their Methods and Results before the other sections helps to clarify their idea of the experiment or study as a whole. You might consider using each assignment to practice different approaches to drafting the report, to find the order that works best for you.

What should I do before drafting the lab report?

The best way to prepare to write the lab report is to make sure that you fully understand everything you need to about the experiment. Obviously, if you don’t quite know what went on during the lab, you’re going to find it difficult to explain the lab satisfactorily to someone else. To make sure you know enough to write the report, complete the following steps:

- What are we going to do in this lab? (That is, what’s the procedure?)

- Why are we going to do it that way?

- What are we hoping to learn from this experiment?

- Why would we benefit from this knowledge?

- Consult your lab supervisor as you perform the lab. If you don’t know how to answer one of the questions above, for example, your lab supervisor will probably be able to explain it to you (or, at least, help you figure it out).

- Plan the steps of the experiment carefully with your lab partners. The less you rush, the more likely it is that you’ll perform the experiment correctly and record your findings accurately. Also, take some time to think about the best way to organize the data before you have to start putting numbers down. If you can design a table to account for the data, that will tend to work much better than jotting results down hurriedly on a scrap piece of paper.

- Record the data carefully so you get them right. You won’t be able to trust your conclusions if you have the wrong data, and your readers will know you messed up if the other three people in your group have “97 degrees” and you have “87.”

- Consult with your lab partners about everything you do. Lab groups often make one of two mistakes: two people do all the work while two have a nice chat, or everybody works together until the group finishes gathering the raw data, then scrams outta there. Collaborate with your partners, even when the experiment is “over.” What trends did you observe? Was the hypothesis supported? Did you all get the same results? What kind of figure should you use to represent your findings? The whole group can work together to answer these questions.

- Consider your audience. You may believe that audience is a non-issue: it’s your lab TA, right? Well, yes—but again, think beyond the classroom. If you write with only your lab instructor in mind, you may omit material that is crucial to a complete understanding of your experiment, because you assume the instructor knows all that stuff already. As a result, you may receive a lower grade, since your TA won’t be sure that you understand all the principles at work. Try to write towards a student in the same course but a different lab section. That student will have a fair degree of scientific expertise but won’t know much about your experiment particularly. Alternatively, you could envision yourself five years from now, after the reading and lectures for this course have faded a bit. What would you remember, and what would you need explained more clearly (as a refresher)?

Once you’ve completed these steps as you perform the experiment, you’ll be in a good position to draft an effective lab report.

Introductions

How do i write a strong introduction.

For the purposes of this handout, we’ll consider the Introduction to contain four basic elements: the purpose, the scientific literature relevant to the subject, the hypothesis, and the reasons you believed your hypothesis viable. Let’s start by going through each element of the Introduction to clarify what it covers and why it’s important. Then we can formulate a logical organizational strategy for the section.

The inclusion of the purpose (sometimes called the objective) of the experiment often confuses writers. The biggest misconception is that the purpose is the same as the hypothesis. Not quite. We’ll get to hypotheses in a minute, but basically they provide some indication of what you expect the experiment to show. The purpose is broader, and deals more with what you expect to gain through the experiment. In a professional setting, the hypothesis might have something to do with how cells react to a certain kind of genetic manipulation, but the purpose of the experiment is to learn more about potential cancer treatments. Undergraduate reports don’t often have this wide-ranging a goal, but you should still try to maintain the distinction between your hypothesis and your purpose. In a solubility experiment, for example, your hypothesis might talk about the relationship between temperature and the rate of solubility, but the purpose is probably to learn more about some specific scientific principle underlying the process of solubility.

For starters, most people say that you should write out your working hypothesis before you perform the experiment or study. Many beginning science students neglect to do so and find themselves struggling to remember precisely which variables were involved in the process or in what way the researchers felt that they were related. Write your hypothesis down as you develop it—you’ll be glad you did.

As for the form a hypothesis should take, it’s best not to be too fancy or complicated; an inventive style isn’t nearly so important as clarity here. There’s nothing wrong with beginning your hypothesis with the phrase, “It was hypothesized that . . .” Be as specific as you can about the relationship between the different objects of your study. In other words, explain that when term A changes, term B changes in this particular way. Readers of scientific writing are rarely content with the idea that a relationship between two terms exists—they want to know what that relationship entails.

Not a hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that there is a significant relationship between the temperature of a solvent and the rate at which a solute dissolves.”

Hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases.”

Put more technically, most hypotheses contain both an independent and a dependent variable. The independent variable is what you manipulate to test the reaction; the dependent variable is what changes as a result of your manipulation. In the example above, the independent variable is the temperature of the solvent, and the dependent variable is the rate of solubility. Be sure that your hypothesis includes both variables.

Justify your hypothesis

You need to do more than tell your readers what your hypothesis is; you also need to assure them that this hypothesis was reasonable, given the circumstances. In other words, use the Introduction to explain that you didn’t just pluck your hypothesis out of thin air. (If you did pluck it out of thin air, your problems with your report will probably extend beyond using the appropriate format.) If you posit that a particular relationship exists between the independent and the dependent variable, what led you to believe your “guess” might be supported by evidence?

Scientists often refer to this type of justification as “motivating” the hypothesis, in the sense that something propelled them to make that prediction. Often, motivation includes what we already know—or rather, what scientists generally accept as true (see “Background/previous research” below). But you can also motivate your hypothesis by relying on logic or on your own observations. If you’re trying to decide which solutes will dissolve more rapidly in a solvent at increased temperatures, you might remember that some solids are meant to dissolve in hot water (e.g., bouillon cubes) and some are used for a function precisely because they withstand higher temperatures (they make saucepans out of something). Or you can think about whether you’ve noticed sugar dissolving more rapidly in your glass of iced tea or in your cup of coffee. Even such basic, outside-the-lab observations can help you justify your hypothesis as reasonable.

Background/previous research

This part of the Introduction demonstrates to the reader your awareness of how you’re building on other scientists’ work. If you think of the scientific community as engaging in a series of conversations about various topics, then you’ll recognize that the relevant background material will alert the reader to which conversation you want to enter.

Generally speaking, authors writing journal articles use the background for slightly different purposes than do students completing assignments. Because readers of academic journals tend to be professionals in the field, authors explain the background in order to permit readers to evaluate the study’s pertinence for their own work. You, on the other hand, write toward a much narrower audience—your peers in the course or your lab instructor—and so you must demonstrate that you understand the context for the (presumably assigned) experiment or study you’ve completed. For example, if your professor has been talking about polarity during lectures, and you’re doing a solubility experiment, you might try to connect the polarity of a solid to its relative solubility in certain solvents. In any event, both professional researchers and undergraduates need to connect the background material overtly to their own work.

Organization of this section

Most of the time, writers begin by stating the purpose or objectives of their own work, which establishes for the reader’s benefit the “nature and scope of the problem investigated” (Day 1994). Once you have expressed your purpose, you should then find it easier to move from the general purpose, to relevant material on the subject, to your hypothesis. In abbreviated form, an Introduction section might look like this:

“The purpose of the experiment was to test conventional ideas about solubility in the laboratory [purpose] . . . According to Whitecoat and Labrat (1999), at higher temperatures the molecules of solvents move more quickly . . . We know from the class lecture that molecules moving at higher rates of speed collide with one another more often and thus break down more easily [background material/motivation] . . . Thus, it was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases [hypothesis].”

Again—these are guidelines, not commandments. Some writers and readers prefer different structures for the Introduction. The one above merely illustrates a common approach to organizing material.

How do I write a strong Materials and Methods section?

As with any piece of writing, your Methods section will succeed only if it fulfills its readers’ expectations, so you need to be clear in your own mind about the purpose of this section. Let’s review the purpose as we described it above: in this section, you want to describe in detail how you tested the hypothesis you developed and also to clarify the rationale for your procedure. In science, it’s not sufficient merely to design and carry out an experiment. Ultimately, others must be able to verify your findings, so your experiment must be reproducible, to the extent that other researchers can follow the same procedure and obtain the same (or similar) results.

Here’s a real-world example of the importance of reproducibility. In 1989, physicists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischman announced that they had discovered “cold fusion,” a way of producing excess heat and power without the nuclear radiation that accompanies “hot fusion.” Such a discovery could have great ramifications for the industrial production of energy, so these findings created a great deal of interest. When other scientists tried to duplicate the experiment, however, they didn’t achieve the same results, and as a result many wrote off the conclusions as unjustified (or worse, a hoax). To this day, the viability of cold fusion is debated within the scientific community, even though an increasing number of researchers believe it possible. So when you write your Methods section, keep in mind that you need to describe your experiment well enough to allow others to replicate it exactly.

With these goals in mind, let’s consider how to write an effective Methods section in terms of content, structure, and style.

Sometimes the hardest thing about writing this section isn’t what you should talk about, but what you shouldn’t talk about. Writers often want to include the results of their experiment, because they measured and recorded the results during the course of the experiment. But such data should be reserved for the Results section. In the Methods section, you can write that you recorded the results, or how you recorded the results (e.g., in a table), but you shouldn’t write what the results were—not yet. Here, you’re merely stating exactly how you went about testing your hypothesis. As you draft your Methods section, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much detail? Be precise in providing details, but stay relevant. Ask yourself, “Would it make any difference if this piece were a different size or made from a different material?” If not, you probably don’t need to get too specific. If so, you should give as many details as necessary to prevent this experiment from going awry if someone else tries to carry it out. Probably the most crucial detail is measurement; you should always quantify anything you can, such as time elapsed, temperature, mass, volume, etc.

- Rationale: Be sure that as you’re relating your actions during the experiment, you explain your rationale for the protocol you developed. If you capped a test tube immediately after adding a solute to a solvent, why did you do that? (That’s really two questions: why did you cap it, and why did you cap it immediately?) In a professional setting, writers provide their rationale as a way to explain their thinking to potential critics. On one hand, of course, that’s your motivation for talking about protocol, too. On the other hand, since in practical terms you’re also writing to your teacher (who’s seeking to evaluate how well you comprehend the principles of the experiment), explaining the rationale indicates that you understand the reasons for conducting the experiment in that way, and that you’re not just following orders. Critical thinking is crucial—robots don’t make good scientists.

- Control: Most experiments will include a control, which is a means of comparing experimental results. (Sometimes you’ll need to have more than one control, depending on the number of hypotheses you want to test.) The control is exactly the same as the other items you’re testing, except that you don’t manipulate the independent variable-the condition you’re altering to check the effect on the dependent variable. For example, if you’re testing solubility rates at increased temperatures, your control would be a solution that you didn’t heat at all; that way, you’ll see how quickly the solute dissolves “naturally” (i.e., without manipulation), and you’ll have a point of reference against which to compare the solutions you did heat.

Describe the control in the Methods section. Two things are especially important in writing about the control: identify the control as a control, and explain what you’re controlling for. Here is an example:

“As a control for the temperature change, we placed the same amount of solute in the same amount of solvent, and let the solution stand for five minutes without heating it.”

Structure and style

Organization is especially important in the Methods section of a lab report because readers must understand your experimental procedure completely. Many writers are surprised by the difficulty of conveying what they did during the experiment, since after all they’re only reporting an event, but it’s often tricky to present this information in a coherent way. There’s a fairly standard structure you can use to guide you, and following the conventions for style can help clarify your points.

- Subsections: Occasionally, researchers use subsections to report their procedure when the following circumstances apply: 1) if they’ve used a great many materials; 2) if the procedure is unusually complicated; 3) if they’ve developed a procedure that won’t be familiar to many of their readers. Because these conditions rarely apply to the experiments you’ll perform in class, most undergraduate lab reports won’t require you to use subsections. In fact, many guides to writing lab reports suggest that you try to limit your Methods section to a single paragraph.

- Narrative structure: Think of this section as telling a story about a group of people and the experiment they performed. Describe what you did in the order in which you did it. You may have heard the old joke centered on the line, “Disconnect the red wire, but only after disconnecting the green wire,” where the person reading the directions blows everything to kingdom come because the directions weren’t in order. We’re used to reading about events chronologically, and so your readers will generally understand what you did if you present that information in the same way. Also, since the Methods section does generally appear as a narrative (story), you want to avoid the “recipe” approach: “First, take a clean, dry 100 ml test tube from the rack. Next, add 50 ml of distilled water.” You should be reporting what did happen, not telling the reader how to perform the experiment: “50 ml of distilled water was poured into a clean, dry 100 ml test tube.” Hint: most of the time, the recipe approach comes from copying down the steps of the procedure from your lab manual, so you may want to draft the Methods section initially without consulting your manual. Later, of course, you can go back and fill in any part of the procedure you inadvertently overlooked.

- Past tense: Remember that you’re describing what happened, so you should use past tense to refer to everything you did during the experiment. Writers are often tempted to use the imperative (“Add 5 g of the solid to the solution”) because that’s how their lab manuals are worded; less frequently, they use present tense (“5 g of the solid are added to the solution”). Instead, remember that you’re talking about an event which happened at a particular time in the past, and which has already ended by the time you start writing, so simple past tense will be appropriate in this section (“5 g of the solid were added to the solution” or “We added 5 g of the solid to the solution”).

- Active: We heated the solution to 80°C. (The subject, “we,” performs the action, heating.)

- Passive: The solution was heated to 80°C. (The subject, “solution,” doesn’t do the heating–it is acted upon, not acting.)

Increasingly, especially in the social sciences, using first person and active voice is acceptable in scientific reports. Most readers find that this style of writing conveys information more clearly and concisely. This rhetorical choice thus brings two scientific values into conflict: objectivity versus clarity. Since the scientific community hasn’t reached a consensus about which style it prefers, you may want to ask your lab instructor.

How do I write a strong Results section?

Here’s a paradox for you. The Results section is often both the shortest (yay!) and most important (uh-oh!) part of your report. Your Materials and Methods section shows how you obtained the results, and your Discussion section explores the significance of the results, so clearly the Results section forms the backbone of the lab report. This section provides the most critical information about your experiment: the data that allow you to discuss how your hypothesis was or wasn’t supported. But it doesn’t provide anything else, which explains why this section is generally shorter than the others.

Before you write this section, look at all the data you collected to figure out what relates significantly to your hypothesis. You’ll want to highlight this material in your Results section. Resist the urge to include every bit of data you collected, since perhaps not all are relevant. Also, don’t try to draw conclusions about the results—save them for the Discussion section. In this section, you’re reporting facts. Nothing your readers can dispute should appear in the Results section.

Most Results sections feature three distinct parts: text, tables, and figures. Let’s consider each part one at a time.

This should be a short paragraph, generally just a few lines, that describes the results you obtained from your experiment. In a relatively simple experiment, one that doesn’t produce a lot of data for you to repeat, the text can represent the entire Results section. Don’t feel that you need to include lots of extraneous detail to compensate for a short (but effective) text; your readers appreciate discrimination more than your ability to recite facts. In a more complex experiment, you may want to use tables and/or figures to help guide your readers toward the most important information you gathered. In that event, you’ll need to refer to each table or figure directly, where appropriate:

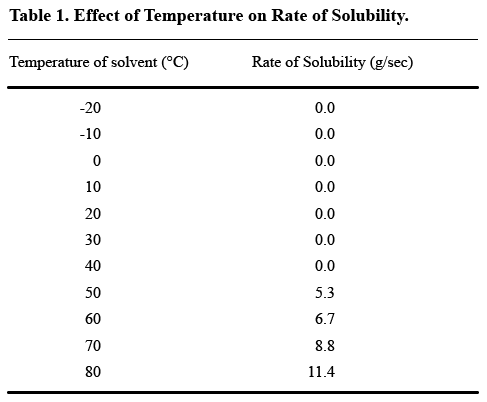

“Table 1 lists the rates of solubility for each substance”

“Solubility increased as the temperature of the solution increased (see Figure 1).”

If you do use tables or figures, make sure that you don’t present the same material in both the text and the tables/figures, since in essence you’ll just repeat yourself, probably annoying your readers with the redundancy of your statements.

Feel free to describe trends that emerge as you examine the data. Although identifying trends requires some judgment on your part and so may not feel like factual reporting, no one can deny that these trends do exist, and so they properly belong in the Results section. Example:

“Heating the solution increased the rate of solubility of polar solids by 45% but had no effect on the rate of solubility in solutions containing non-polar solids.”

This point isn’t debatable—you’re just pointing out what the data show.

As in the Materials and Methods section, you want to refer to your data in the past tense, because the events you recorded have already occurred and have finished occurring. In the example above, note the use of “increased” and “had,” rather than “increases” and “has.” (You don’t know from your experiment that heating always increases the solubility of polar solids, but it did that time.)

You shouldn’t put information in the table that also appears in the text. You also shouldn’t use a table to present irrelevant data, just to show you did collect these data during the experiment. Tables are good for some purposes and situations, but not others, so whether and how you’ll use tables depends upon what you need them to accomplish.

Tables are useful ways to show variation in data, but not to present a great deal of unchanging measurements. If you’re dealing with a scientific phenomenon that occurs only within a certain range of temperatures, for example, you don’t need to use a table to show that the phenomenon didn’t occur at any of the other temperatures. How useful is this table?

As you can probably see, no solubility was observed until the trial temperature reached 50°C, a fact that the text part of the Results section could easily convey. The table could then be limited to what happened at 50°C and higher, thus better illustrating the differences in solubility rates when solubility did occur.

As a rule, try not to use a table to describe any experimental event you can cover in one sentence of text. Here’s an example of an unnecessary table from How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , by Robert A. Day:

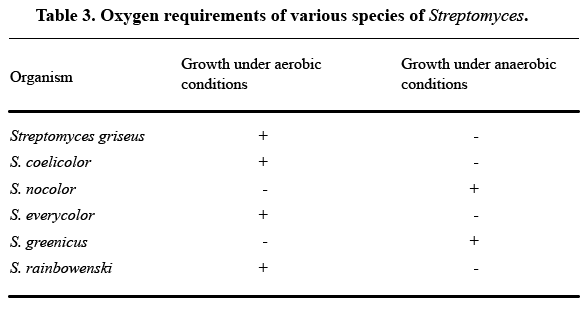

As Day notes, all the information in this table can be summarized in one sentence: “S. griseus, S. coelicolor, S. everycolor, and S. rainbowenski grew under aerobic conditions, whereas S. nocolor and S. greenicus required anaerobic conditions.” Most readers won’t find the table clearer than that one sentence.

When you do have reason to tabulate material, pay attention to the clarity and readability of the format you use. Here are a few tips:

- Number your table. Then, when you refer to the table in the text, use that number to tell your readers which table they can review to clarify the material.

- Give your table a title. This title should be descriptive enough to communicate the contents of the table, but not so long that it becomes difficult to follow. The titles in the sample tables above are acceptable.

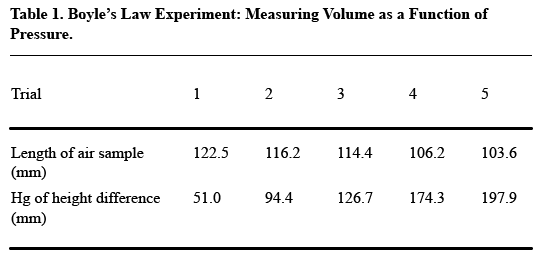

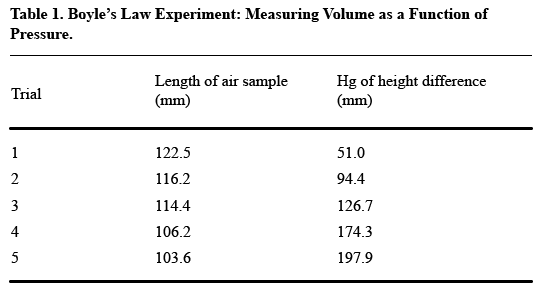

- Arrange your table so that readers read vertically, not horizontally. For the most part, this rule means that you should construct your table so that like elements read down, not across. Think about what you want your readers to compare, and put that information in the column (up and down) rather than in the row (across). Usually, the point of comparison will be the numerical data you collect, so especially make sure you have columns of numbers, not rows.Here’s an example of how drastically this decision affects the readability of your table (from A Short Guide to Writing about Chemistry , by Herbert Beall and John Trimbur). Look at this table, which presents the relevant data in horizontal rows:

It’s a little tough to see the trends that the author presumably wants to present in this table. Compare this table, in which the data appear vertically:

The second table shows how putting like elements in a vertical column makes for easier reading. In this case, the like elements are the measurements of length and height, over five trials–not, as in the first table, the length and height measurements for each trial.

- Make sure to include units of measurement in the tables. Readers might be able to guess that you measured something in millimeters, but don’t make them try.

- Don’t use vertical lines as part of the format for your table. This convention exists because journals prefer not to have to reproduce these lines because the tables then become more expensive to print. Even though it’s fairly unlikely that you’ll be sending your Biology 11 lab report to Science for publication, your readers still have this expectation. Consequently, if you use the table-drawing option in your word-processing software, choose the option that doesn’t rely on a “grid” format (which includes vertical lines).

How do I include figures in my report?

Although tables can be useful ways of showing trends in the results you obtained, figures (i.e., illustrations) can do an even better job of emphasizing such trends. Lab report writers often use graphic representations of the data they collected to provide their readers with a literal picture of how the experiment went.

When should you use a figure?

Remember the circumstances under which you don’t need a table: when you don’t have a great deal of data or when the data you have don’t vary a lot. Under the same conditions, you would probably forgo the figure as well, since the figure would be unlikely to provide your readers with an additional perspective. Scientists really don’t like their time wasted, so they tend not to respond favorably to redundancy.

If you’re trying to decide between using a table and creating a figure to present your material, consider the following a rule of thumb. The strength of a table lies in its ability to supply large amounts of exact data, whereas the strength of a figure is its dramatic illustration of important trends within the experiment. If you feel that your readers won’t get the full impact of the results you obtained just by looking at the numbers, then a figure might be appropriate.

Of course, an undergraduate class may expect you to create a figure for your lab experiment, if only to make sure that you can do so effectively. If this is the case, then don’t worry about whether to use figures or not—concentrate instead on how best to accomplish your task.

Figures can include maps, photographs, pen-and-ink drawings, flow charts, bar graphs, and section graphs (“pie charts”). But the most common figure by far, especially for undergraduates, is the line graph, so we’ll focus on that type in this handout.

At the undergraduate level, you can often draw and label your graphs by hand, provided that the result is clear, legible, and drawn to scale. Computer technology has, however, made creating line graphs a lot easier. Most word-processing software has a number of functions for transferring data into graph form; many scientists have found Microsoft Excel, for example, a helpful tool in graphing results. If you plan on pursuing a career in the sciences, it may be well worth your while to learn to use a similar program.

Computers can’t, however, decide for you how your graph really works; you have to know how to design your graph to meet your readers’ expectations. Here are some of these expectations:

- Keep it as simple as possible. You may be tempted to signal the complexity of the information you gathered by trying to design a graph that accounts for that complexity. But remember the purpose of your graph: to dramatize your results in a manner that’s easy to see and grasp. Try not to make the reader stare at the graph for a half hour to find the important line among the mass of other lines. For maximum effectiveness, limit yourself to three to five lines per graph; if you have more data to demonstrate, use a set of graphs to account for it, rather than trying to cram it all into a single figure.

- Plot the independent variable on the horizontal (x) axis and the dependent variable on the vertical (y) axis. Remember that the independent variable is the condition that you manipulated during the experiment and the dependent variable is the condition that you measured to see if it changed along with the independent variable. Placing the variables along their respective axes is mostly just a convention, but since your readers are accustomed to viewing graphs in this way, you’re better off not challenging the convention in your report.

- Label each axis carefully, and be especially careful to include units of measure. You need to make sure that your readers understand perfectly well what your graph indicates.

- Number and title your graphs. As with tables, the title of the graph should be informative but concise, and you should refer to your graph by number in the text (e.g., “Figure 1 shows the increase in the solubility rate as a function of temperature”).

- Many editors of professional scientific journals prefer that writers distinguish the lines in their graphs by attaching a symbol to them, usually a geometric shape (triangle, square, etc.), and using that symbol throughout the curve of the line. Generally, readers have a hard time distinguishing dotted lines from dot-dash lines from straight lines, so you should consider staying away from this system. Editors don’t usually like different-colored lines within a graph because colors are difficult and expensive to reproduce; colors may, however, be great for your purposes, as long as you’re not planning to submit your paper to Nature. Use your discretion—try to employ whichever technique dramatizes the results most effectively.

- Try to gather data at regular intervals, so the plot points on your graph aren’t too far apart. You can’t be sure of the arc you should draw between the plot points if the points are located at the far corners of the graph; over a fifteen-minute interval, perhaps the change occurred in the first or last thirty seconds of that period (in which case your straight-line connection between the points is misleading).

- If you’re worried that you didn’t collect data at sufficiently regular intervals during your experiment, go ahead and connect the points with a straight line, but you may want to examine this problem as part of your Discussion section.

- Make your graph large enough so that everything is legible and clearly demarcated, but not so large that it either overwhelms the rest of the Results section or provides a far greater range than you need to illustrate your point. If, for example, the seedlings of your plant grew only 15 mm during the trial, you don’t need to construct a graph that accounts for 100 mm of growth. The lines in your graph should more or less fill the space created by the axes; if you see that your data is confined to the lower left portion of the graph, you should probably re-adjust your scale.

- If you create a set of graphs, make them the same size and format, including all the verbal and visual codes (captions, symbols, scale, etc.). You want to be as consistent as possible in your illustrations, so that your readers can easily make the comparisons you’re trying to get them to see.

How do I write a strong Discussion section?

The discussion section is probably the least formalized part of the report, in that you can’t really apply the same structure to every type of experiment. In simple terms, here you tell your readers what to make of the Results you obtained. If you have done the Results part well, your readers should already recognize the trends in the data and have a fairly clear idea of whether your hypothesis was supported. Because the Results can seem so self-explanatory, many students find it difficult to know what material to add in this last section.

Basically, the Discussion contains several parts, in no particular order, but roughly moving from specific (i.e., related to your experiment only) to general (how your findings fit in the larger scientific community). In this section, you will, as a rule, need to:

Explain whether the data support your hypothesis

- Acknowledge any anomalous data or deviations from what you expected