- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

Formal Analysis Paper Examples

- Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Formal Analysis Paper Example 1

Formal Analysis Paper Example 2

Formal Analysis Paper Example 3

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

How to Analyze Art – Formal Art Analysis Guide and Example

What is this Guide Helpful for?

Every work of art is a complex system and a pattern of intentions. Learning to observe and analyze artworks’ most distinctive features is a task that requires time but primarily training. Even the eye must be trained to art -whether paintings, photography, architecture, drawing, sculptures, or mixed-media installations. The eyes, as when one passes from darkness to light, need time to adapt to the visual and sensory stimuli of artworks.

This brief compendium aims to provide helpful tools and suggestions to analyze art. It can be useful to guide students who are facing a critical analysis of a particular artwork, as in the case of a paper assigned to high school art students. But it can also be helpful when the assignment concerns the creation of practical work, as it helps to reflect on the artistic practice of experienced artists and inspire their own work. However, that’s not all. These concise prompts can also assist those interested in taking a closer look at the art exhibited by museums, galleries, and cultural institutions. They are general suggestions that can be applied to art objects of any era or style since they are those suggested by the history of art criticism.

Knowing exactly what an artist wanted to communicate through his or her artwork is an impossible task, but not even relevant in critical analysis. What matters is to personally interpret and understand it, always wondering what ideas its features suggest. The viewer’s attention can fall on different aspects of a painting, and different observers can even give contradictory interpretations of the same artwork. Yet the starting point is the same setlist of questions . Here are the most common and effective ones.

How to Write a Successful Art Analysis

Composition and formal analysis: what can i see.

The first question to ask in front of an artwork is: what do I see? What is it made of? And how is it realized? Let’s limit ourselves to an objective, accurate pure description of the object; from this preliminary formal analysis, other questions (and answers!) will arise.

- You can ask yourself what kind of object it is, what genre ; if it represents something figuratively or abstractly, observing its overall style.

- You can investigate the composition and the form : shape (e.g. geometric, curvilinear, angular, decorative, tridimensional, human), size (is it small or large size? is it a choice forced by the limits of the display or not?), orientation (horizontally or vertically oriented)

- the use of the space : the system of arrangement (is it symmetrical? Is there a focal point or emphasis on specific parts ?), perspective (linear perspective, aerial perspective, atmospheric perspective), space viewpoint, sense of full and voids, and rhythm.

- You can observe its colors : palette and hues (cool, warm), intensity (bright, pure, dull, glossy, or grainy…), transparency or opacity, value, colors effects, and choices (e.g. complementary colors)

- Observe the texture (is it flat or tactile? Has it other surface qualities?)

- or the type of lines (horizontal, vertical, implied lines, chaotic, underdrawing, contour, or leading lines)

After completing this observation, it is important to ask yourself what are the effects of these chromatic, compositional, and formal choices. Are they the result of randomness, limitations of the site, display, or material? Or perhaps they are meant to convey a specific idea or overall mood? Does the artwork support your insights?

Media and Materials: How the Artist Create?

- First of all, the medium must be investigated. What are these objects? Architecture, drawing, film, installation, painting, performing art, photography, printmaking, sculpture, sound art, textiles, and more.

- What materials and tools did the artists use to create their work? Oil paint, acrylic paint, charcoal, pastel, tempera, fresco, marble, bronze, but also concrete, glass, stone, wood, ceramics, lithography…The list of materials is potentially endless, especially in contemporary arts, but it is also among the easiest information to find! A valid catalog or museum label will always list materials and techniques used by artists.

- What techniques, methods, and processes are used by the artist? The same goes for materials, techniques are numerous and often related to the overall feeling or style that the artist has set out to achieve. In a critical analysis, it is important to reflect on what this technique entails. Do not overdo with a verbose technical explanation.

Why did the artist choose to make the work this way and with such features (materials and techniques)? Are they traditional, academic techniques and materials or, on the contrary, innovative and experimental? What idea does the artist communicate with the choice of these media ? Try to reflect, for example, on their preciousness, or cultural significance, or even durability, fragility, heaviness, or lightness.

Context, Biography, Purpose: What’s Outside the Artwork?

Through formal analysis, it is possible to obtain a precise description of the artistic object. However, artworks are also documents, which attest to facts that happen or have happened outside the frame! The artwork relates to themes, stories, specific ideas, which belong to the artist and to the society in which he or she is immersed. To analyze art in a relevant way, we also must consider the context .

- What are the intentions of the artist to create this work? The purpose? Art may be commissioned, commemorative, educational, of practical use, for the public or for private individuals, realized to communicate something. Let’s ask ourselves why the artist created it, and why at that particular time.

- The artist’s life also cannot be overlooked. We always look at the work in the light of his biography: in what moment of life was it made? Where was the artist? What other artworks had he/she done in close temporal proximity? Biographical sources are invaluable.

- In what context (historical, social, political, cultural) was the artwork made? Artwork supports (or may even deliberately oppose) the climate in which it is immersed. Find out about the political, natural, historical event; the economic, religious, cultural situation of its period.

- Of paramount importance is the cultural atmosphere. What artistic movements , currents, fashions, and styles were prevalent at the time? This allows us to make comparisons with other objects, to question the taste of the time. In other words, to open the horizons of our analysis.

Subject and Meaning: What does it Want to Communicate?

We observed artwork as an object, with visible material and formal characteristics; then we understood that it can be influenced by the context and intentions of the artist. Finally, it is essential to investigate what it wants to communicate. The content of the work passes through the subject matter, its stories, implicit or explicit symbolism.

- You can preliminarily ask what genre of artwork it is, which is very helpful with paintings. Is it a realistic painting of a landscape, abstract, religious, historical-mythical, a portrait, a still life, or much else?

- You can ask questions about the title if it is present. Or perhaps question its absence.

- You can observe the figures. Ask yourself about their identity, age, rank, connections with the artist, or cultural relevance. Observe what their expression or pose communicates.

- You can also observe the objects, places, or scenes that take place in the work. How are they depicted (realistic, abstract, impressionistic, expressionistic, primitive); what story do they tell?

- Are there concepts that perhaps are conveyed implicitly, through symbols, allegories, signs, textual or iconographic elements? Do they have a precise meaning inserted there?

- You can try to describe the overall feeling of the artwork, whether it is positive or negative, but also go deeper: does it communicate calmness, melancholy, tension, energy, or anger, shock? Try to listen to your own emotional reaction as well.

Subjective Interpretation: What does it Communicate to Me?

And finally, the crucial question, what did this work spark in me ?

We can talk about aesthetic taste and feeling, but not only. A critical judgment also involves the degree of effectiveness of the work. Has the artist succeeded, through his formal, technical, stylistic choices, in communicating a specific idea? What did the critics think at the time and ask yourself what you think today? Are there any temporal or personal biases that may affect your judgment? Significative artworks are capable of speaking, of telling a story in every era. Whether nice or bad.

A Brief History of Art Criticism

The stimulus questions collected here are the result of the experience of different methods of analysis developed by art critics throughout history. Art criticism has developed different analytical methodologies, placing the focus of research on different aspects of art. We can trace three major macro-trends and all of them can be used to develop a personal critical method:

The Formal Art Analysis

Formal art analysis is conducted primarily by connoisseurs, experts in attributing paintings or sculptures to the hand of specific artists. Formal analysis adheres strictly to the object-artwork by providing a pure description of it. It focuses on its visual, most distinctive features: on the subject, composition, material, technique, and other elements. Famous formalists and purovisibilists were Giovanni Morelli, Bernard Berenson, Roberto Longhi, Roger Fry, and Heinrich Wölfflin, who elaborated different categories of formal principles.

The Iconological Method

In the iconological method, the content of the work, its meaning, and cultural implications begin to take on relevancy. Aby Warburg and later the Warburg Institute opened up to the analysis of art as an interdisciplinary subject, questioning the correlations between art, philosophy, culture. The fortune of the iconological method, however, is due to Erwin Panofsky, who observed the artwork integrally, through three levels of interpretation. A first, formal, superficial level; the second level of observation of the iconographic elements, and a third called iconological, in which the analysis finally becomes deep, trying to grasp the meaning of the elements.

Social Art History and Beyond

Then, in the 1950s, a third trend began, which placed the focus primarily on the social context of the artwork. With Arnold Hauser, Francis Klingender, and Frederick Antal, the social history of art was born. Social art historians conceive the work of art as a structural system that conveys specific ideologies, whose aspects related to the time period of the artists must also be investigated. Analyses on commissioning, institutionalization, production mechanisms, and the role and function of the artist in society began to spread. It also opens art criticism to researches on taste, fruition, and the study of art in psychoanalytic, pedagogical, anthropological terms.

10 Art Analysis Tips

We defined the questions you need to ask yourself to write a meaningful artwork analysis. Then, we identified the main approaches used by art historians while criticizing art: formal analysis, iconographic interpretation, and study of the social context. However, art interpretation is always open to new stimuli and insights, and it is a work of continuous training.

Here are 10 aspects to keep in mind when observing a good artwork (or a bad one!):

- Any feeling towards a work of art is legitimate -whether it is a painting, picture, sculpture, or contemporary installation. What do you like or dislike about it? You could write about the shapes and colors, how the artist used them, their technique. You can analyze the museum setting or its original location; the ideas, or the cultural context to which the artist belongs. You can think about the feelings or memories it evokes. The important thing is that your judgment is justified with relevant arguments that strictly relate to the artwork and its elements.

- Analyzing does not mean describing. A precise description of the work and its distinctive features is essential, but we must go beyond that. Consider also what is outside the frame.

- Strive to use an inquiry-based approach. Ask yourself questions, start with objective observation and then go deeper. Wonder what features suggest. Notice a color…well, why that color, and why there?

- Observe a wide range of visual elements. Artworks are complex systems, so try to look at them in all their components. Not just color, shapes, or technique, but also rhythm, compositional devices, emphasis, style, texture…and much more!

- To get a visual analysis as accurate as possible, it might be very useful to have a comprehensive glossary . Here is MoMA’s one: https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/learn/courses/Vocabulary_for_Discussing_Art.pdf and Artlex: https://www.artlex.com/art-terms/

- Less is more . Do you want to write about an entire artistic movement or a particularly prolific artist? Focus on the most significant works, the ones you can really say something personal and effective about. Similarly, choose only relevant and productive information; it should aid better understanding of the objects, not take the reader away from it.

- Support what you write with images! Accompany your text with sketches or high-quality photographs. Choose black and white pictures if you want to highlight forms or lights, details or evidence inside the artwork to support your personal interpretations, objects placed in the art room if you analyze also curatorial choices.

- See as much live artwork as possible. Whenever you can, attend temporary exhibitions, museums, galleries… the richer your visual background will be, the more attentive and receptive your eye will be! Connections and comparisons are what make an art criticism truly rich and open-minding.

- Be inspired by the words of artists, art experts, and creatives . Listen as a beloved artwork relates to their art practice or personal artistic vision, to build your personal one. Here are other helpful links: https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/154?=MOOC

- And finally, trust your intuition! As you noticed in this decalogue, numerous aspects require study and rational analysis but don’t forget to formalize your instinctive impressions as well. Art is made for that, too.

Related Posts:

- A Guide to the Different Types of Sculptures and Statues

- Cost and Price Range of Embroidery Machines: A…

- How to Make Art Prints - A Step by Step Guide

- How to Find Your Art Style - Step by Step Guide

- How to Draw Digital Art - A Complete Guide for Beginners

- How to Make an Art Studio - A Step-by-Step Guide

- Library Catalogue

The Student Learning Commons blog is your online writing and learning community

Art History 101: How to Write an Effective Art Analysis

This blog post was written by former employee and SLC Writing Services Coordinator Hermine Chan.

Visual culture is an important aspect of the study of the humanities. Art presents a window into the lives and cultures of the peoples of the past, and understanding how to engage with this visual culture can be an asset to the study of history. Yet, it can be daunting to write about artwork, since most disciplines do not constantly engage with art. This article will offer some basic tips on how to engage with artwork and write an effective art history analysis.

1. Artwork as primary source

The first tip to understanding artwork is to look at it as a primary source. A primary source is an “immediate, first-hand [account] of a topic, from people who had a direct connection with it” (“ Primary Sources: A Research Guide ,” n.d.). Now, you can begin the first steps of analysis by finding the basic information about the source. You can start by considering the following questions:

- Who is the artist? What information can you find on this person?

- When was this work created? What art movements took place at this time period? What significant historical events were taking place?

- Was this work commissioned by anyone? If yes, how might this impact the artwork? Who is the audience?

- Additionally, “why” questions are very helpful: Why would the artist make this piece? Why did the artist choose a certain colour? Why are the different elements in the painting arranged this way? And so on.

While these are very important questions to ask, it might not be possible to find answers to all of them. That is ok! These questions are meant to guide you in the first steps of writing your paper and provide you with some information and ideas on how to continue your work. Also note that because you are essentially writing a primary source analysis, you are looking for patterns in the work to inform your analysis. You can find patterns by looking at colours, lighting, perspective, and composition.

2. Colours and lighting

Colours and lighting can provide useful information about the artist’s intent. Sometimes artists use these tools to highlight or obscure an aspect of a piece of art. Here is an example:

Notice how in this painting, the five men on the right are in focus. Their brightly coloured clothing against the dark background is one way in which their position is highlighted. The lighting also helps to bring the viewers’ attention to the men, especially to their facial expressions.

Here, keep in mind the importance of patterns in informing your interpretations. Consider how the colours and lighting influence the mood of the painting, how they obscure or highlight certain elements, or if a colour has a significant meaning.

Image credit: Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew , c. 1599-1600, oil on canvas, Contarelli Chapel, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

3. Perspective and composition

Perspective and composition are additional tools artists use to guide the viewers’ attention to the different elements in their works. Much like colour and lighting, the position of certain elements in an artwork can be helpful for interpretation. Some important questions to consider are as follows: What is significant about the position of a certain element? Does the arrangement of the different elements in the piece send a message? If yes, what could that mean? How would this message relate to the other patterns that you have identified?

Here is an example:

The fountain on the left is positioned diagonally from the left of the etching toward the middle, this guides the viewers’ eyes toward the monument and informs the viewers of its importance. Further, the fountain becomes the focus of the artwork because of its size compared to the rest of the buildings in the work. Notice, also, how the lighting in this piece obscures the humans at the bottom of the etching as to not distract the viewers from looking at the fountain.

If you are struggling with perspective and composition, it might be a good idea to come back to the artwork after a break. After the break look at the artwork again and think about the following questions: Where are your eyes drawn to most? Why there? What about the composition or perspective makes this possible? Keep in mind that composition and perspective have to work hand in hand with other tools like colours and lighting. Once you have examined all of these elements, you can identify some patterns in the art so write yourself some notes to help you in the writing process.

Image credit: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the large Trevi Fountain formerly called the Acqua Vergine , from Views of Rome, 1750-1759, etching on heavy ivory laid paper, the Art Institute of Chicago,

4. Make an outline and write a thesis statement

It can become overwhelming to analyze a piece of art, especially if it is your first time doing so. An outline will keep your ideas organized and help you identify patterns easier. Note that the patterns you identify will help you to come up with a thesis statement that drives your argument. So, it is a good idea to keep your ideas organized! You can organize your outline based on the different categories you would like to explore or the individual elements you think are significant. There is no right way to make an outline, but if you need some help you can find ideas here . Additionally, you might benefit from drawing diagrams to categorize your ideas. Write down or highlight the overlaps you notice; they will be very useful when you are working on your thesis statement, because these overlaps signal themes and messages the artists might be conveying. Now that you have gathered your notes and identified some themes, you are ready to write your thesis statement.

5. Support your thesis statement

Once you have a thesis, it is time to support it with your evidence. This might sound difficult at first since your evidence does not come from sentences and paragraphs. Keep your outline nearby and use the visual details that you have already noted to support your claim. Here, you might have to describe some of the details in the artwork to make your evidence appear clearer to your readers. If that is the case, try to be concise and only describe the elements that are relevant to your thesis. For instance, if your thesis focuses on the importance of colours in depicting social hierarchy, you might want to briefly describe the colours used to depict a certain social class. Additionally, think back to your answers to some of the “why” questions presented in this article. You will need to explain your reasoning for focusing on your chosen evidence, so your answers to some of these “why” questions help you to support your evidence. Further, if you have some information about the historical period or the art movements of the time, you can examine the details of the piece of art according to this information. Artists generally depict themes that correspond to the events of their own lifetime, so an understanding of the historical period might be useful in contextualizing your evidence.

Remember that these are only basic tips meant to ease your path in writing an art history analysis. Do not hesitate to ask for support if you need it. Your instructors and TAs are experts in their fields and will be happy to assist you with your assignments. And as always you can book a consultation with a Writing and Learning Peer at the Student Learning Commons at any point in the writing process. Happy writing!

Get in touch! Have an idea for a future blog post? Want to become a contributor to the SLC In Common Blog? Have a writing or learning question you've always wanted answered? Contact us and we'll reply. We read all questions and feedback and do our best to answer all writing/learning strategies-related questions directly on the blog within three weeks of receipt.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Essays in Art History

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These OWL resources provide guidance on typical genres with the art history discipline that may appear in professional settings or academic assignments, including museum catalog entries, museum title cards, art history analysis, notetaking, and art history exams.

Art History Analysis – Formal Analysis and Stylistic Analysis

Typically in an art history class the main essay students will need to write for a final paper or for an exam is a formal or stylistic analysis.

A formal analysis is just what it sounds like – you need to analyze the form of the artwork. This includes the individual design elements – composition, color, line, texture, scale, contrast, etc. Questions to consider in a formal analysis is how do all these elements come together to create this work of art? Think of formal analysis in relation to literature – authors give descriptions of characters or places through the written word. How does an artist convey this same information?

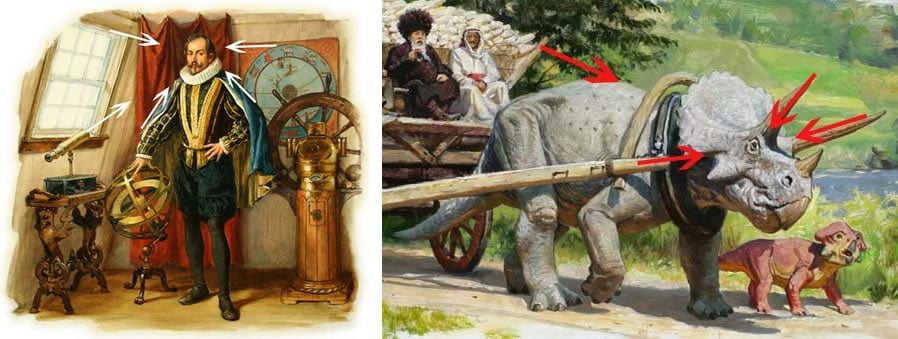

Organize your information and focus on each feature before moving onto the text – it is not ideal to discuss color and jump from line to then in the conclusion discuss color again. First summarize the overall appearance of the work of art – is this a painting? Does the artist use only dark colors? Why heavy brushstrokes? etc and then discuss details of the object – this specific animal is gray, the sky is missing a moon, etc. Again, it is best to be organized and focused in your writing – if you discuss the animals and then the individuals and go back to the animals you run the risk of making your writing unorganized and hard to read. It is also ideal to discuss the focal of the piece – what is in the center? What stands out the most in the piece or takes up most of the composition?

A stylistic approach can be described as an indicator of unique characteristics that analyzes and uses the formal elements (2-D: Line, color, value, shape and 3-D all of those and mass).The point of style is to see all the commonalities in a person’s works, such as the use of paint and brush strokes in Van Gogh’s work. Style can distinguish an artist’s work from others and within their own timeline, geographical regions, etc.

Methods & Theories To Consider:

Expressionism

Instructuralism

Postmodernism

Social Art History

Biographical Approach

Poststructuralism

Museum Studies

Visual Cultural Studies

Stylistic Analysis Example:

The following is a brief stylistic analysis of two Greek statues, an example of how style has changed because of the “essence of the age.” Over the years, sculptures of women started off as being plain and fully clothed with no distinct features, to the beautiful Venus/Aphrodite figures most people recognize today. In the mid-seventh century to the early fifth, life-sized standing marble statues of young women, often elaborately dress in gaily painted garments were created known as korai. The earliest korai is a Naxian women to Artemis. The statue wears a tight-fitted, belted peplos, giving the body a very plain look. The earliest korai wore the simpler Dorian peplos, which was a heavy woolen garment. From about 530, most wear a thinner, more elaborate, and brightly painted Ionic linen and himation. A largely contrasting Greek statue to the korai is the Venus de Milo. The Venus from head to toe is six feet seven inches tall. Her hips suggest that she has had several children. Though her body shows to be heavy, she still seems to almost be weightless. Viewing the Venus de Milo, she changes from side to side. From her right side she seems almost like a pillar and her leg bears most of the weight. She seems be firmly planted into the earth, and since she is looking at the left, her big features such as her waist define her. The Venus de Milo had a band around her right bicep. She had earrings that were brutally stolen, ripping her ears away. Venus was noted for loving necklaces, so it is very possibly she would have had one. It is also possible she had a tiara and bracelets. Venus was normally defined as “golden,” so her hair would have been painted. Two statues in the same region, have throughout history, changed in their style.

Compare and Contrast Essay

Most introductory art history classes will ask students to write a compare and contrast essay about two pieces – examples include comparing and contrasting a medieval to a renaissance painting. It is always best to start with smaller comparisons between the two works of art such as the medium of the piece. Then the comparison can include attention to detail so use of color, subject matter, or iconography. Do the same for contrasting the two pieces – start small. After the foundation is set move on to the analysis and what these comparisons or contrasting material mean – ‘what is the bigger picture here?’ Consider why one artist would wish to show the same subject matter in a different way, how, when, etc are all questions to ask in the compare and contrast essay. If during an exam it would be best to quickly outline the points to make before tackling writing the essay.

Compare and Contrast Example:

Stele of Hammurabi from Susa (modern Shush, Iran), ca. 1792 – 1750 BCE, Basalt, height of stele approx. 7’ height of relief 28’

Stele, relief sculpture, Art as propaganda – Hammurabi shows that his law code is approved by the gods, depiction of land in background, Hammurabi on the same place of importance as the god, etc.

Top of this stele shows the relief image of Hammurabi receiving the law code from Shamash, god of justice, Code of Babylonian social law, only two figures shown, different area and time period, etc.

Stele of Naram-sin , Sippar Found at Susa c. 2220 - 2184 bce. Limestone, height 6'6"

Stele, relief sculpture, Example of propaganda because the ruler (like the Stele of Hammurabi) shows his power through divine authority, Naramsin is the main character due to his large size, depiction of land in background, etc.

Akkadian art, made of limestone, the stele commemorates a victory of Naramsin, multiple figures are shown specifically soldiers, different area and time period, etc.

Iconography

Regardless of what essay approach you take in class it is absolutely necessary to understand how to analyze the iconography of a work of art and to incorporate into your paper. Iconography is defined as subject matter, what the image means. For example, why do things such as a small dog in a painting in early Northern Renaissance paintings represent sexuality? Additionally, how can an individual perhaps identify these motifs that keep coming up?

The following is a list of symbols and their meaning in Marriage a la Mode by William Hogarth (1743) that is a series of six paintings that show the story of marriage in Hogarth’s eyes.

- Man has pockets turned out symbolizing he has lost money and was recently in a fight by the state of his clothes.

- Lap dog shows loyalty but sniffs at woman’s hat in the husband’s pocket showing sexual exploits.

- Black dot on husband’s neck believed to be symbol of syphilis.

- Mantel full of ugly Chinese porcelain statues symbolizing that the couple has no class.

- Butler had to go pay bills, you can tell this by the distasteful look on his face and that his pockets are stuffed with bills and papers.

- Card game just finished up, women has directions to game under foot, shows her easily cheating nature.

- Paintings of saints line a wall of the background room, isolated from the living, shows the couple’s complete disregard to faith and religion.

- The dangers of sexual excess are underscored in the Hograth by placing Cupid among ruins, foreshadowing the inevitable ruin of the marriage.

- Eventually the series (other five paintings) shows that the woman has an affair, the men duel and die, the woman hangs herself and the father takes her ring off her finger symbolizing the one thing he could salvage from the marriage.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.5.2: Formal or Critical Analysis of Art

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 156840

- Pamela Sachant, Peggy Blood, Jeffery LeMieux, & Rita Tekippe

- University System of Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

While restricting our attention only to a description of the formal elements of an artwork may at first seem limited or even tedious, a careful and methodical examination of the physical components of an artwork is an important first step in “decoding” its meaning. It is useful, therefore, to begin at the beginning. There are four aspects of a formal analysis: description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation . In addition to defining these terms, we will look at examples.

Description

- What can we notice at first glance about a work of art? Is it two-dimensional or three-dimensional? What is the medium? What kinds of actions were required in its production? How big is the work? What are the elements of design used within it?

- Starting with line: is it soft or hard, jagged or straight, expressive or mechanical? How is line being used to describe space?

- Considering shape: are the shapes large or small, hard-edged or soft? What is the relationship between shapes? Do they compete with one another for prominence? What shapes are in front? Which ones fade into the background?

- Indicating mass and volume: if two-dimensional, what means if any are used to give the illusion that the presented forms have weight and occupy space? If three-dimensional, what space is occupied or filled by the work? What is the mass of the work?

- Organizing space: does the artist use perspective? If so, what kind? If the work uses linear perspective, where are the horizon line and vanishing point(s) located?

- On texture: how is texture being used? Is it actual or implied texture?

- In terms of color: what kinds of colors are used? Is there a color scheme? Is the image overall light, medium, or dark?

- Once the elements of the artwork have been identified, next come questions of how these elements are related. How are the elements arranged? In other words, how have principles of design been employed?

- What elements in the work were used to create unity and provide variety? How have the elements been used to do so?

- What is the scale of the work? Is it larger or smaller than what it represents (if it does depict someone or something)? Are the elements within the work in proportion to one another?

- Is the work symmetrically or asymmetrically balanced?

- What is used within the artwork to create emphasis? Where are the areas of emphasis? How has the movement been conveyed in the work, for example, through line or placement of figures?

- Are there any elements within the work that create rhythm? Are any shapes or colors repeated?

Interpretation

- Interpretation comes as much from the individual viewer as it does from the artwork. It derives from the intersection of what an object symbolizes to the artist and what it means to the viewer. It also often records how the meaning of objects has been changed by time and culture.

- Interpretation, then, is a process of unfolding. A work that may seem to mean one thing on first inspection may come to mean something more when studied further. Just as when re-reading a favorite book or re-watching a favorite movie, we often notice things not seen on the first viewing; interpretations of art objects can also reveal themselves slowly.

- Claims about meaning can be made, but are better when they are backed up with supporting evidence. Interpretations can also change and some interpretations are better than others.

- All this work of description, analysis, and interpretation, is done with one goal in mind: to make an evaluation about a work of art.

- Just as interpretations vary, so do evaluations. Your evaluation includes what you have discovered about the work during your examination as well as what you have learned, about the work, yourself, and others in the process.

- Your reaction to the artwork is an important component of your evaluation: what do you feel when you look at it? And, do you like the work? How and why do you find it visually pleasing, in some way disturbing, and emotionally engaging?

Examples of Formal Analysis

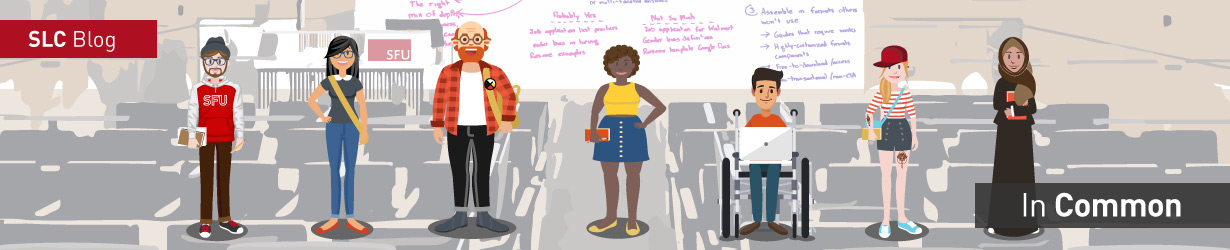

Snow Storm—Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth by J. M. W. Turner

- First, on the level of description , the dark structure of the foundering steamboat is hinted at in the center of the work, while heavy smoke from the vessel, pitching waves, and swirling snow surround it.

- The brown and gray curving lines are created with long strokes of heavily applied paint that expand to the edges of the composition.

- Second, we note that the paint application, heavy, with long strokes, adds dramatic movement to the image. We see that the design principle of scale and proportion is being used in the small size of the steamboat in relation to the overall canvas.

- Now let us interpret these elements and their relation: The artist has emphasized the maelstrom of sea, snow, and wind. A glimpse of blue sky through the smoke and snow above the vessel is the only indication of space beyond this gripping scene of danger, and provides the only place for the viewer’s eyes to rest from the tumult. This scene is humanity’s struggle for survival against powerful forces of nature.

- And finally, we are ready to evaluate this work. Is it powerfully effective in reminding us of the transitory nature of our own limited existence, a memento morii, perhaps? Or is it a wise caution of the limits of our human power to control our destiny? Does the work have sufficient power and value to be accepted by us as significant? The verdict of history tells us it is. J.M.W. Turner is considered a significant artist of his time, and this work is one that is thought to support that verdict.

- In the end, however, each of us can accept or reject this historical verdict for our own reasons. We may fear the sea. We may reject the use of technology as valiantly heroic. We may see the British colonial period as one of oppression and tyranny and this work as an illustration of the hubris of that time. Whatever we conclude, this work of art stands as a catalyst for this important dialogue.

Lady at the Tea Table- Mary Cassatt Mary Cassatt

Another example of formal analysis. Consider Lady at the Tea Table by Mary Cassatt Mary Cassatt (1844-1925, USA, lived France) is best known for her paintings, drawings, and prints of mothers and children. In those works, she focused on the bond between them as well as the strength and dignity of women within the predominantly domestic and maternal roles they played in the nineteenth century.

- Lady at the Tea Table is a depiction of a woman in a later period of her life, and captures the sense of calm power a matriarch held within the home. (Figure 4.2)

- First, a description of the elements being used in this work: The white of the wall behind the woman and the tablecloth before her provide a strong contrast to the black of her clothing and the blue of the tea set.

- The gold frame of the artwork on the wall, the gold rings on her fingers, and the gold bands on the china link those three main elements of the painting.

- Analysis shows the organizing principle of variety is employed in the rectangles behind the woman’s head and the multiple circles and arcs of the individual pieces of the tea set. The composition is a stable triangle formed by the woman’s head and body, and extending to the pieces of china that span the foreground from one edge of the composition to the other.

- Let us interpret these observations. There is little evidence of movement in the work other than the suggestion that the woman’s hand, resting on the handle of the teapot, may soon move. Her gaze, directed away from the viewer and out of the picture frame, implies she is in the midst of pouring tea, but her stillness suggests she is lost in thought. How to evaluate this work? The artist expresses a restrained but powerful strength of character in her treatment of this subject. Is the lack of obvious movement in the work a comment on the emergence of women’s roles in society, a hope or a demand for change? Or is it a monument to the quiet dignity of the domestic life of Victorian era Paris? The gold of the frame, the rings, and the china dishes appear to unify three disparate objects into one statement of value. Do they symbolize art, fidelity, and service? Is this a comment on the restrictions of French domestic society, or a claim to its strength? One indication of the quality of a work of art is its power to evoke multiple interpretations. This open and poetic richness is one reason why the work of Mary Cassatt is considered to be important.

Following are examples on how to include the visual elements of art and principles of design while doing a formal analysis (a critique) on a work of art. (The visual elements of art and principles of design will be discussed in Chapters 2 and 3.)

Let's start by dissecting the visual elements of art.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Bedroom, 1889. Oil on canvas, 28¾ x 36¼”. " Van Gogh, The Bedroom " by profzucker is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 .

When analyzing, remember elements of art: Line, Shape, Color, Space and Texture.

Now you are seeing it differently. You put attention to detail. You can see through these five different possibilities by reading this artwork.

Let's put it all together. Following is an example on how to include the visual elements of art and principles of design while doing a formal analysis (a critique) on a work of art.

How to do visual (formal) analysis in art history. (2017, September 18), uploaded by SmartHistory. https://youtu.be/sM2MOyonDsY

Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

- DeWitte, Debra J. , Larmann, Ralph M. , and Shields, M. Kathryn Gateways to Art: Understanding the Visual Arts Third Edition. Copyright © 2015 Thames & Hudson

- Toledo Museum of Art. The Art of Seeing Art. www.toledomuseum.org

How to analyze an artwork: a step-by-step guide

Last Updated on August 16, 2023

This article has been written for high school art students who are working upon a critical study of art, sketchbook annotation or an essay-based artist study. It contains a list of questions to guide students through the process of analyzing visual material of any kind, including drawing, painting, mixed media, graphic design, sculpture, printmaking, architecture, photography, textiles, fashion and so on (the word ‘artwork’ in this article is all-encompassing). The questions include a wide range of specialist art terms, prompting students to use subject-specific vocabulary in their responses. It combines advice from art analysis textbooks as well as from high school art teachers who have first-hand experience teaching these concepts to students.

COPYRIGHT NOTE: This material is available as a printable art analysis PDF handout . This may be used free of charge in a classroom situation. To share this material with others, please use the social media buttons at the bottom of this page. Copying, sharing, uploading or distributing this article (or the PDF) in any other way is not permitted.

READ NEXT: How to make an artist website (and why you need one)

Why do we study art?

Almost all high school art students carry out critical analysis of artist work, in conjunction with creating practical work. Looking critically at the work of others allows students to understand compositional devices and then explore these in their own art. This is one of the best ways for students to learn.

Instructors who assign formal analyses want you to look—and look carefully. Think of the object as a series of decisions that an artist made. Your job is to figure out and describe, explain, and interpret those decisions and why the artist may have made them. – The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 10

Art analysis tips

- ‘I like this’ or ‘I don’t like this’ without any further explanation or justification is not analysis . Personal opinions must be supported with explanation, evidence or justification.

- ‘Analysis of artwork’ does not mean ‘description of artwork’ . To gain high marks, students must move beyond stating the obvious and add perceptive, personal insight. Students should demonstrate higher order thinking – the ability to analyse, evaluate and synthesize information and ideas. For example, if color has been used to create strong contrasts in certain areas of an artwork, students might follow this observation with a thoughtful assumption about why this is the case – perhaps a deliberate attempt by the artist to draw attention to a focal point, helping to convey thematic ideas.

Although description is an important part of a formal analysis, description is not enough on its own. You must introduce and contextualize your descriptions of the formal elements of the work so the reader understands how each element influences the work’s overall effect on the viewer. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- Cover a range of different visual elements and design principles . It is common for students to become experts at writing about one or two elements of composition, while neglecting everything else – for example, only focusing upon the use of color in every artwork studied. This results in a narrow, repetitive and incomplete analysis of the artwork. Students should ensure that they cover a wide range of art elements and design principles, as well as address context and meaning, where required. The questions below are designed to ensure that students cover a broad range of relevant topics within their analysis.

- Write alongside the artwork discussed . In almost all cases, written analysis should be presented alongside the work discussed, so that it is clear which artwork comments refer to. This makes it easier for examiners to follow and evaluate the writing.

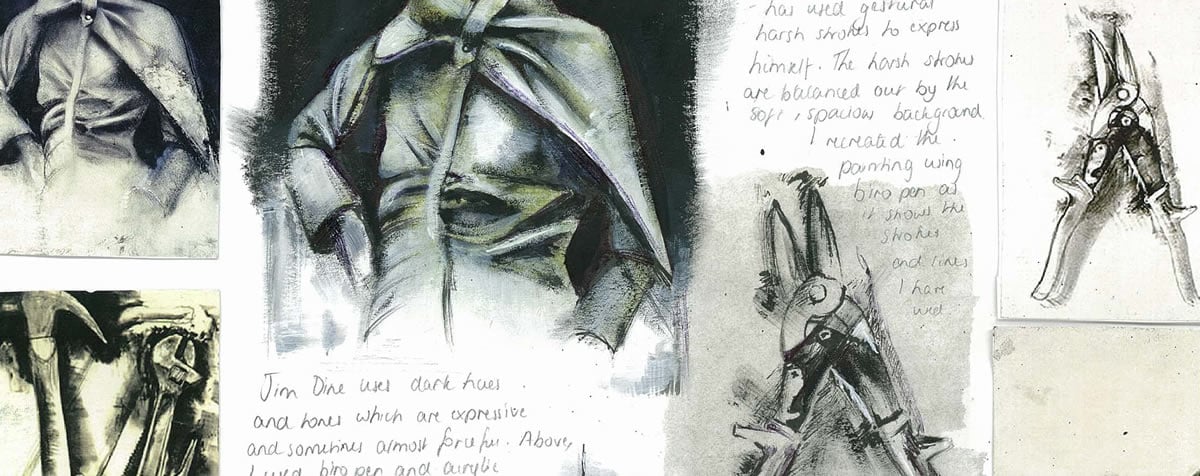

- Support writing with visual analysis . It is almost always helpful for high school students to support written material with sketches, drawings and diagrams that help the student understand and analyse the piece of art. This might include composition sketches; diagrams showing the primary structure of an artwork; detailed enlargements of small sections; experiments imitating use of media or technique; or illustrations overlaid with arrows showing leading lines and so on. Visual investigation of this sort plays an important role in many artist studies.

Making sketches or drawings from works of art is the traditional, centuries-old way that artists have learned from each other. In doing this, you will engage with a work and an artist’s approach even if you previously knew nothing about it. If possible do this whenever you can, not from a postcard, the internet or a picture in a book, but from the actual work itself. This is useful because it forces you to look closely at the work and to consider elements you might not have noticed before. – Susie Hodge, How to Look at Art 7

Finally, when writing about art, students should communicate with clarity; demonstrate subject-specific knowledge; use correct terminology; generate personal responses; and reference all content and ideas sourced from others. This is explained in more detail in our article about high school sketchbooks .

What should students write about?

Although each aspect of composition is treated separately in the questions below, students should consider the relationship between visual elements (line, shape, form, value/tone, color/hue, texture/surface, space) and how these interact to form design principles (such as unity, variety, emphasis, dominance, balance, symmetry, harmony, movement, contrast, rhythm, pattern, scale, proportion) to communicate meaning.

As complex as works of art typically are, there are really only three general categories of statements one can make about them. A statement addresses form, content or context (or their various interrelations). – Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia 5

…a formal analysis – the result of looking closely – is an analysis of the form that the artist produces; that is, an analysis of the work of art, which is made up of such things as line, shape, color, texture, mass, composition. These things give the stone or canvas its form, its expression, its content, its meaning. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

This video by Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Naraelle Hohensee provides an excellent example of how to analyse a piece of art (it is important to note that this video is an example of ‘formal analysis’ and doesn’t include contextual analysis, which is also required by many high school art examination boards, in addition to the formal analysis illustrated here):

Composition analysis: a list of questions

The questions below are designed to facilitate direct engagement with an artwork and to encourage a breadth and depth of understanding of the artwork studied. They are intended to prompt higher order thinking and to help students arrive at well-reasoned analysis.

It is not expected that students answer every question (doing so would result in responses that are excessively long, repetitious or formulaic); rather, students should focus upon areas that are most helpful and relevant for the artwork studied (for example, some questions are appropriate for analyzing a painting, but not a sculpture). The words provided as examples are intended to help students think about appropriate vocabulary to use when discussing a particular topic. Definitions of more complex words have been provided.

Students should not attempt to copy out questions and then answer them; rather the questions should be considered a starting point for writing bullet pointed annotation or sentences in paragraph form.

CONTENT, CONTEXT AND MEANING

Subject matter / themes / issues / narratives / stories / ideas.

There can be different, competing, and contradictory interpretations of the same artwork. An artwork is not necessarily about what the artist wanted it to be about. – Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary 6

Our interest in the painting grows only when we forget its title and take an interest in the things that it does not mention…” – Françoise Barbe-Gall, How to Look at a Painting 8

- Does the artwork fall within an established genre (i.e. historical; mythical; religious; portraiture; landscape; still life; fantasy; architectural)?

- Are there any recognisable objects, places or scenes ? How are these presented (i.e. idealized; realistic; indistinct; hidden; distorted; exaggerated; stylized; reflected; reduced to simplified/minimalist form; primitive; abstracted; concealed; suggested; blurred or focused)?

- Have people been included? What can we tell about them (i.e. identity; age; attire; profession; cultural connections; health; family relationships; wealth; mood/expression)? What can we learn from their pose (i.e. frontal; profile; partly turned; body language)? Where are they looking (i.e. direct eye contact with viewer; downcast; interested in other subjects within the artwork)? Can we work out relationships between figures from the way they are posed?

What do the clothing, furnishings, accessories (horses, swords, dogs, clocks, business ledgers and so forth), background, angle of the head or posture of the head and body, direction of the gaze, and facial expression contribute to our sense of the figure’s social identity (monarch, clergyman, trophy wife) and personality (intense, cool, inviting)? – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- What props and important details are included (drapery; costumes; adornment; architectural elements; emblems; logos; motifs)? How do aspects of setting support the primary subject? What is the effect of including these items within the arrangement (visual unity; connections between different parts of the artwork; directs attention; surprise; variety and visual interest; separates / divides / borders; transformation from one object to another; unexpected juxtaposition)?

If a waiter served you a whole fish and a scoop of chocolate ice cream on the same plate, your surprise might be caused by the juxtaposition , or the side-by-side contrast, of the two foods. – Vocabulary.com

A motif is an element in a composition or design that can be used repeatedly for decorative, structural, or iconographic purposes. A motif can be representational or abstract, and it can be endowed with symbolic meaning. Motifs can be repeated in multiple artworks and often recur throughout the life’s work of an individual artist. – John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Art 11

- Does the artwork communicate an action, narrative or story (i.e. historical event or illustrate a scene from a story)? Has the arrangement been embellished, set up or contrived?

- Does the artwork explore movement ? Do you gain a sense that parts of the artwork are about to change, topple or fall (i.e. tension; suspense)? Does the artwork capture objects in motion (i.e. multiple or sequential images; blurred edges; scene frozen mid-action; live performance art; video art; kinetic art)?

- What kind of abstract elements are shown (i.e. bars; shapes; splashes; lines)? Have these been derived from or inspired by realistic forms? Are they the result of spontaneous, accidental creation or careful, deliberate arrangement?

- Does the work include the appropriation of work by other artists, such as within a parody or pop art? What effect does this have (i.e. copyright concerns)?

Parody: mimicking the appearance and/or manner of something or someone, but with a twist for comic effect or critical comment, as in Saturday Night Live’s political satires – Dr. Robert J. Belton, Art History: A Preliminary Handbook, The University of British Columbia 5

- Does the subject captivate an instinctual response , such as items that are informative, shocking or threatening for humans (i.e. dangerous places; abnormally positioned items; human faces; the gaze of people; motion; text)? Heap map tracking has demonstrated that these elements catch our attention, regardless of where they are positioned – James Gurney writes more about this fascinating topic .

- What kind of text has been used (i.e. font size; font weight; font family; stenciled; hand-drawn; computer-generated; printed)? What has influenced this choice of text?

- Do key objects or images have symbolic value or provide a cue to meaning ? How does the artwork convey deeper, conceptual themes (i.e. allegory; iconographic elements; signs; metaphor; irony)?

Allegory is a device whereby abstract ideas can be communicated using images of the concrete world. Elements, whether figures or objects, in a painting or sculpture are endowed with symbolic meaning. Their relationships and interactions combine to create more complex meanings. – John A. Parks, Universal Principles of Art 11

An iconography is a particular range or system of types of image used by an artist or artists to convey particular meanings. For example in Christian religious painting there is an iconography of images such as the lamb which represents Christ, or the dove which represents the Holy Spirit. – Tate.org.uk

- What tone of voice does the artwork have (i.e. deliberate; honest; autobiographical; obvious; direct; unflinching; confronting; subtle; ambiguous; uncertain; satirical; propagandistic)?

- What is your emotional response to the artwork? What is the overall mood (i.e positive; energetic; excitement; serious; sedate; peaceful; calm; melancholic; tense; uneasy; uplifting; foreboding; calm; turbulent)? Which subject matter choices help to communicate this mood (i.e. weather and lighting conditions; color of objects and scenes)?

- Does the title change the way you interpret the work?

- Were there any design constraints relating to the subject matter or theme/s (i.e. a sculpture commissioned to represent a specific subject, place or idea)?

- Are there thematic connections with your own project? What can you learn from the way the artist has approached this subject?

Wider contexts

All art is in part about the world in which it emerged. – Terry Barrett, Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary 6

- Supported by research, can you identify when, where and why the work was created and its original intention or purpose (i.e. private sale; commissioned for a specific owner; commemorative; educational; promotional; illustrative; decorative; confrontational; useful or practical utility; communication; created in response to a design brief; private viewing; public viewing)? In what way has this background influenced the outcome (i.e. availability of tools, materials or time; expectations of the patron / audience)?

- Where is the place of construction or design site and how does this influence the artwork (i.e. reflects local traditions, craftsmanship, or customs; complements surrounding designs; designed to accommodate weather conditions / climate; built on historic site)? Was the artwork originally located somewhere different?

- Which events and surrounding environments have influenced this work (i.e. natural events; social movements such as feminism; political events, economic situations, historic events, religious settings, cultural events)? What effect did these have?

- Is the work characteristic of an artistic style, movement or time period ? Has it been influenced by trends, fashions or ideologies ? How can you tell?

- Can you make any relevant connections or comparisons with other artworks ? Have other artists explored a similar subject in a similar way? Did this occur before or after this artwork was created?

- Can you make any relevant connections to other fields of study or expression (i.e. geography, mathematics, literature, film, music, history or science)?

- Which key biographical details about the artist are relevant in understanding this artwork (upbringing and personal situation; family and relationships; psychological state; health and fitness; socioeconomic status; employment; ethnicity; culture; gender; education, religion; interests, attitudes, values and beliefs)?

- Is this artwork part of a larger body of work ? Is this typical of the work the artist is known for?

- How might your own upbringing, beliefs and biases distort your interpretation of the artwork? Does your own response differ from the public response, that of the original audience and/or interpretation by critics ?

- How do these wider contexts compare to the contexts surrounding your own work?

COMPOSITION AND FORMAT

- What is the overall size, shape and orientation of the artwork (i.e. vertical, horizontal, portrait, landscape or square)? Has this format been influenced by practical considerations (i.e. availability of materials; display constraints ; design brief restrictions; screen sizes; common aspect ratios in film or photography such as 4:3 or 2:3; or paper sizes such as A4, A3, A2, A1)?

- How do images fit within the frame (cropped; truncated; shown in full)? Why is this format appropriate for the subject matter?

- Are different parts of the artwork physically separate, such as within a diptych or triptych ?

- Where are the boundaries of the artwork (i.e. is the artwork self-contained; compact; intersecting; sprawling)?

- Is the artwork site-specific or designed to be displayed across multiple locations or environments?

- Does the artwork have a fixed, permanent format, or was it modified, moved or adjusted over time ? What causes such changes (i.e. weather and exposure to the elements – melting, erosion, discoloration, decaying, wind movement, surface abrasion; structural failure – cracking, breaking; damage caused by unpredictable events, such as fire or vandalism; intentional movement, such as rotation or sensor response; intentional impermanence, such as an installation assembled for an exhibition and removed afterwards; viewer interaction; additions, renovations and restoration by subsequent artists or users; a project so expansive it takes years to construct)? How does this change affect the artwork? Are there stylistic variances between parts?

- Is the artwork viewed from one angle or position, or are dynamic viewpoints and serial vision involved? (Read more about Gordon Cullen’s concept of serial vision here ).

- How does the scale and format of the artwork relate to the environment where it is positioned, used, installed or hung (i.e. harmonious with landscape typography; sensitive to adjacent structures; imposing or dwarfed by surroundings; human scale)? Is the artwork designed to be viewed from one vantage point (i.e. front facing; viewed from below; approached from a main entrance; set at human eye level) or many? Are images taken from the best angle?

- Would a similar format benefit your own project? Why / why not?

Structure / layout

- Has the artwork been organised using a formal system of arrangement or mathematical proportion (i.e. rule of thirds; golden ratio or spiral; grid format; geometric; dominant triangle; or circular composition) or is the arrangement less predictable (i.e. chaotic, random, accidental, fragmented, meandering, scattered; irregular or spontaneous)? How does this system of arrangement help with the communication of ideas? Can you draw a diagram to show the basic structure of the artwork?

- Can you see a clear intention with alignment and positioning of parts within the artwork (i.e. edges aligned; items spaced equally; simple or complex arrangement; overlapping, clustered or concentrated objects; dispersed, separate items; repetition of forms; items extending beyond the frame; frames within frames; bordered perimeter or patterned edging; broken borders)? What effect do these visual devices have (i.e. imply hierarchy; help the viewer understand relationships between parts of artwork; create rhythm)?

- Does the artwork have a primary axis of symmetry (vertical, diagonal, horizontal)? Can you locate a center of balance? Is the artwork symmetrical, asymmetrical (i.e. stable), radial, or intentionally unbalanced (i.e. to create tension or unease)?

- Can you draw a diagram to illustrate emphasis and dominance (i.e. ‘blocking in’ mass, where the ‘heavier’ dominant forms appear in the composition)? Where are dominant items located within the frame?

- How do your eyes move through the composition?

- Could your own artwork use a similar organisational structure?

- What types of linear mark-making are shown (thick; thin; short; long; soft; bold; delicate; feathery; indistinct; faint; irregular; intermittent; freehand; ruled; mechanical; expressive; loose; blurred; dashing; cross-hatching; meandering; gestural, fluid; flowing; jagged; spiky; sharp)? What atmosphere, moods, emotions or ideas do these evoke?

- Are there any interrupted, suggested or implied lines (i.e. lines that can’t literally be seen, but the viewer’s brain connects the dots between separate elements)?

- Repeating lines : may simulate material qualities, texture, pattern or rhythm;

- Boundary lines : may segment, divide or separate different areas;

- Leading lines : may manipulate the viewer’s gaze, directing vision or lead the eye to focal points ( eye tracking studies indicate that our eyes leap from one point of interest to another, rather than move smoothly or predictably along leading lines 9 . Lines may nonetheless help to establish emphasis by ‘pointing’ towards certain items );

- Parallel lines : may create a sense of depth or movement through space within a landscape;

- Horizontal lines : may create a sense of stability and permanence;

- Vertical lines : may suggest height, reaching upwards or falling;

- Intersecting perpendicular lines : may suggest rigidity, strength;

- Abstract lines : may balance the composition, create contrast or emphasis;

- Angular / diagonal lines : may suggest tension or unease;

- Chaotic lines : may suggest a sense of agitation or panic;

- Underdrawing, construction lines or contour lines : describe form ( learn more about contour lines in our article about line drawing );

- Curving / organic lines : may suggest nature, peace, movement or energy.

- What is the relationship between line and three-dimensional form? Are outlines used to define form and edges?

- Would it be appropriate to use line in a similar way within your own artwork?

Shape and form

- Can you identify a dominant visual language within the shapes and forms shown (i.e. geometric; angular; rectilinear; curvilinear; organic; natural; fragmented; distorted; free-flowing; varied; irregular; complex; minimal)? Why is this visual language appropriate?

- How are the edges of forms treated (i.e. do they fade away or blur at the edges, as if melting into the page; ripped or torn; distinct and hard-edged; or, in the words of James Gurney, 9 do they ‘dissolve into sketchy lines, paint strokes or drips’)?

- Are there any three-dimensional forms or relief elements within the artwork, such as carved pieces, protruding or sculptural elements? How does this affect the viewing of the work from different angles?

- Is there a variety or repetition of shapes/forms? What effect does this have (i.e. repetition may reinforce ideas, balance composition and/or create harmony / visual unity; variety may create visual interest or overwhelm the viewer with chaos)?

- How are shapes organised in relation to each other, or with the frame of the artwork (i.e. grouped; overlapping; repeated; echoed; fused edges; touching at tangents; contrasts in scale or size; distracting or awkward junctions)?

- Are silhouettes (external edges of objects) considered?

All shapes have silhouettes, and vision research has shown that one of the first tasks of perception is to be able to sort out the silhouette shapes of each of the elements in a scene. – James Gurney, Imaginative Realism 9

- Are forms designed with ergonomics and human scale in mind?

Ergonomics: an applied science concerned with designing and arranging things people use so that the people and things interact most efficiently and safely – Merriam-webster.com

- Can you identify which forms are functional or structural , versus ornamental or decorative ?

- Have any forms been disassembled, ‘cut away’ or exposed , such as a sectional drawing? What is the purpose of this (i.e. to explain construction methods; communicate information; dramatic effect)?

- Would it be appropriate to use shape and form in a similar way within your own artwork?

Value / tone / light

- Has a wide tonal range been used in the artwork (i.e. a broad range of darks, highlights and mid-tones) or is the tonal range limited (i.e. pale and faint; subdued; dull; brooding and dark overall; strong highlights and shadows, with little mid-tone values)? What is the effect of this?

- Where are the light sources within the artwork or scene? Is there a single consistent light source or multiple sources of light (sunshine; light bulbs; torches; lamps; luminous surfaces)? What is the effect of these choices (i.e. mimics natural lighting conditions at a certain time of day or night; figures lit from the side to clarify form; contrasting background or spot-lighting used to accentuate a focal area; soft and diffused lighting used to mute contrasts and minimize harsh shadows; dappled lighting to signal sunshine broken by surrounding leaves; chiaroscuro used to exaggerate theatrical drama and impact; areas cloaked in darkness to minimize visual complexity; to enhance our understanding of narrative, mood or meaning)?

One of the most important ways in which artists can use light to achieve particular effects is in making strong contrasts between light and dark. This contrast is often described as chiaroscuro . – Matthew Treherne, Analysing Paintings, University of Leeds 3

- Are representations of three-dimensional objects and figures flat or tonally modeled ? How do different tonal values change from one to the next (i.e. gentle, smooth gradations; abrupt tonal bands)?

- Are there any unusual, reflective or transparent surfaces, mediums or materials which reflect or transmit light in a special way?

- Has tone been used to help communicate atmospheric perspective (i.e. paler and bluer as objects get further away)?

- Are gallery or environmental light sources where the artwork is displayed fixed or fluctuating? Does the work appear different when viewed at different times of day? How does this affect your interpretation of the work?

- Are shadows depicted within the artwork? What is the effect of these shadows (i.e. anchors objects to the page; creates the illusion of depth and space; creates dramatic contrasts)?

- Do sculptural protrusions or relief elements catch the light and/or create cast shadows or pockets of shadow upon the artwork? How does this influence the viewer’s experience?

- How has tone been used to help direct the viewer’s attention to focal areas?

- Would it be appropriate to use value / tone in a similar way within your own artwork? Why / why not?

Color / hue

- Can you view the true color of the artwork (i.e. are you viewing a low-quality reproduction or examining the artwork in poor lighting)?

- Which color schemes have been used within the artwork (i.e. harmonious; complementary; primary; monochrome; earthy; warm; cool/cold)? Has the artist used a broad or limited color palette (i.e. variety or unity)? Which colors dominate?

- How would you describe the intensity of the colors (vibrant; bright; vivid; glowing; pure; saturated; strong; dull; muted; pale; subdued; bleached; diluted)?

- Are colors transparent or opaque ? Can you see reflected color?

- Has color contrast been used within the artwork (i.e. extreme contrasts; juxtaposition of complementary colors; garish / clashing / jarring)? Are there any abrupt color changes or unexpected uses of color?

- What is the effect of these color choices (i.e. expressing symbolic or thematic ideas; descriptive or realistic depiction of local color; emphasizing focal areas; creating the illusion of aerial perspective; relationships with colors in surrounding environment; creating balance; creating rhythm/pattern/repetition; unity and variety within the artwork; lack of color places emphasis upon shape, detail and form)? What kind of atmosphere do these colors create?

It is often said that warm colors (red, orange, yellow) come forward and produce a sense of excitement (yellow is said to suggest warmth and happiness, as in the smiley face), whereas cool colors (blue, green) recede and have a calming effect. Experiments, however, have proved inconclusive; the response to color – despite clichés about seeing red or feeling blue – is highly personal, highly cultural, highly varied. – Sylvan Barnet, A Short Guide to Writing About Art 2

- Would it be appropriate to use color in a similar way within your own artwork?

Texture / surface / pattern

- Are there any interesting textural, tactile or surface qualities within the artwork (i.e. bumpy; grooved; indented; scratched; stressed; rough; smooth; shiny; varnished; glassy; glossy; polished; matte; sandy; grainy; gritted; leathery; spiky; silky)? How are these created (i.e. inherent qualities of materials; impasto mediums; sculptural materials; illusions or implied texture , such as cross-hatching; finely detailed and intricate areas; organic patterns such as foliage or small stones; repeating patterns ; ornamentation)?

- How are textural or patterned elements positioned and what effect does this have (i.e. used intermittently to provide variety; repeating pattern creates rhythm ; patterns broken create focal points ; textured areas create visual links and unity between separate areas of the artwork; balance between detailed/textured areas and simpler areas; glossy surface creates a sense of luxury; imitation of texture conveys information about a subject, i.e. softness of fur or strands of hair)?

- Would it be appropriate to use texture / surface in a similar way within your own artwork?

Industrial and architectural landscapes are particularly concerned with the arrangement of geometries and form in space… Dr. Ben Guy, Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment using CGI Digital Twins, Urban CGI 12

- Is the pictorial space shallow or deep? How does the artwork create the illusion of depth (i.e. layering of foreground, middle-ground, background ; overlapping of objects; use of shadows to anchor objects; positioning of items in relationship to the horizon line; linear perspective ( learn more about one point perspective here ); tonal modeling; relationships with adjacent objects and those in close proximity – including the human form – to create a sense of scale ; spatial distortions or optical illusions; manipulating scale of objects to create ‘surrealist’ spaces where true scale is unknown)?

- Has an unusual viewpoint been used (i.e. worm’s view; aerial view, looking out a window or through a doorway; a scene reflected in a mirror or shiny surface; looking through leaves; multiple viewpoints combined)? What is the effect of this viewpoint (i.e. allows certain parts of the scene to be dominant and overpowering or squashed, condensed and foreshortened ; or suggests a narrative between two separate spaces ; provides more information about a space than would normally be seen)?

- Is the emphasis upon mass or void ? How densely arranged are components within the artwork or picture plane? What is the relationship between object and surrounding space (i.e. compact / crowded / busy / densely populated, with little surrounding space; spacious; careful interplay between positive and negative space; objects clustered to create areas of visual interest)? What is the effect of this (i.e. creates a sense of emptiness or isolation; business / visual clutter creates a feeling of chaos or claustrophobia)?

- How does the artwork engage with real space – in and around the artwork (i.e. self-contained; closed off; eye contact with viewer; reaching outwards)? Is the viewer expected to move through the artwork? What is the relationship between interior and exterior space ? What connections or contrasts occur between inside and out? Is it comprised of a series of separate or linked spaces?

- Would it be appropriate to use space in a similar way within your own artwork?

Use of media / materials

- What materials and mediums has the artwork been constructed from? Have materials been concealed or presented deceptively (i.e. is there an authenticity / honesty of materials; are materials celebrated; is the structure visible or exposed )? Why were these mediums selected (weight; color; texture; size; strength; flexibility; pliability; fragility; ease of use; cost; cultural significance; durability; availability; accessibility)? Would other mediums have been appropriate?

- Which skills, techniques, methods and processes were used (i.e. traditional; conventional; industrial; contemporary; innovative)? It is important to note that the examiners do not want the regurgitation of long, technical processes, but rather to see personal observations about how processes effect and influence the artwork in question. Would replicating part of the artwork help you gain a better understanding of the processes used?

- Painting: gesso ground > textured mediums > underdrawing > blocking in colors > defining form > final details;

- Architecture: brief > concepts > development > working drawings > foundations > structure > cladding > finishes;

- Graphic design: brief > concepts > development > Photoshop > proofing > printing.

- How does the use of media help the artist to communicate ideas?

- Are these methods useful for your own project?

Finally, remember that these questions are a guide only and are intended to make you start to think critically about the art you are studying and creating.

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this article you may also like our article about high school sketchbooks (which includes a section about sketchbook annotation). If you are looking for more assistance with how to write an art analysis essay you may like our series about writing an artist study .

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] A guide for Analyzing Works of Art; Sculpture and Painting, Durantas

[2] A Short Guide to Writing About Art , Sylvan Barnet (2014) (Amazon affiliate link)

[3] Analysing Paintings , Matthew Treherne, University of Leeds

[4] Writing in Art and Art History , The University of Vermont

[5] Art History: A Preliminary Handbook , Dr. Robert J. Belton, The University of British Columbia (1996)

[6] Criticizing Art: Understanding the Contemporary , Terry Barrett (2011) (Amazon affiliate link)

[7] How to Look at Art , Susie Hodge (2015) (Amazon affiliate link)

[8] How to Look at a Painting , Françoise Barbe-Gall (2011) (Amazon affiliate link)

[9] Imaginative Realism: How to Paint What Doesn’t Exist James Gurney (2009) (Amazon affiliate link)

[10] Art History , The Writing Centre, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

[11] Universal Principles of Art: 100 Key Concepts for Understanding, Analyzing and Practicing Art , John A. Parks (2014) (Amazon affiliate link)

[12] Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment using CGI Digital Twins , Dr. Ben Guy, Urban CGI (2023)