CityU corpus of essay drafts of English language learners: a corpus of textual revision in second language writing

- Original Paper

- Published: 18 April 2015

- Volume 49 , pages 659–683, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- John Lee 1 ,

- Chak Yan Yeung 1 ,

- Amir Zeldes 2 ,

- Marc Reznicek 3 ,

- Anke Lüdeling 4 &

- Jonathan Webster 1

1010 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

Learner corpora consist of texts produced by non-native speakers. In addition to these texts, some learner corpora also contain error annotations, which can reveal common errors made by language learners, and provide training material for automatic error correction. We present a novel type of error-annotated learner corpus containing sequences of revised essay drafts written by non-native speakers of English. Sentences in these drafts are annotated with comments by language tutors, and are aligned to sentences in subsequent drafts. We describe the compilation process of our corpus, present its encoding in TEI XML, and report agreement levels on the error annotations. Further, we demonstrate the potential of the corpus to facilitate research on textual revision in L2 writing, by conducting a case study on verb tenses using ANNIS, a corpus search and visualization platform.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Natural Language Processing

Impact of ChatGPT on learners in a L2 writing practicum: An exploratory investigation

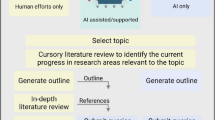

The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Writing Scientific Review Articles

Melissa A. Kacena, Lilian I. Plotkin & Jill C. Fehrenbacher

Examples include the Cambridge Learner Corpus (Nicholls 2003 ), the International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE) (Granger et al. 2009 ), the National University of Singapore Corpus of Learner English (Dahlmeier et al. 2013 ), among many others.

Target hypotheses are costly to produce and often overlooked, but are nevertheless crucial, since any form of error annotation implies a comparison with what the annotator believes the learner was trying to express. Failing to explicitly document error hypotheses can lead to error annotations that are inconsistent and difficult to rationalize. For extensive discussion, see Lüdeling and Hirschmann (to appear).

This corpus is available for research purposes through arrangement with the Halliday Centre for Intelligent Applications of Language Studies at City University of Hong Kong ([email protected]).

For lab reports, we include only the discussion section since other sections contain many equations, numbers and sentence fragments.

Whether the text span contains the specified error is a separate question that will be addressed in Sect. 3.3 .

We omitted the “Delete this” category, since it can be applied on any kind of word, and so it is always valid by definition.

This level of disagreement means that evaluation of the precision of error annotations can differ by as much as 10 %, depending on the annotator (Tetreault and Chodorow 2008 ).

Two experts, both professors of linguistics participated in this evaluation. One was a native speaker of English and the other a near-native speaker who studied in an English-speaking country for 15 years since high school.

Our evaluation does not estimate the coverage, or recall, of the tutor comments, i.e. the proportion of errors in the learner text that were annotated. Since the tutors were not asked to exhaustively annotate all errors in the text, this figure would not be meaningful.

E.g. using XQuery, a generic query language for XML documents, see http://www.w3.org/TR/xquery-30/ .

In this study, we do not consider open-ended comments on verb tense errors, since they vary in terms of the explicitness of the feedback, making it difficult to compare their impact. Furthermore, among comments leading to verb tense revision, open-ended comments (16 %) are much less frequent than error categories (84 %).

The interested reader is referred to http://www.sfb632.uni-potsdam.de/annis/ and to (Krause & Zeldes, 2014 ) for more detail on how the interface can perform sophisticated queries to answer research questions flexibly and without programming skills.

Due to revisions over the course of the LCC project, the comment bank differed slightly for each semester; in particular, a few categories were annotated at different levels of granularity. For example, “Verb needed”, “Noun needed”, “Adjective needed”, and “Adverb needed” from one semester are subsumed by “Part-of-speech incorrect” from another semester. The more fine-grained categories are considered subcategories in our corpus.

Andreu Andrés, M. A., Guardiola, A. A., Matarredona, M. B., MacDonald, P., Fleta, B. M., & Pérez Sabater, C. (2010). Analysing EFL learner output in the MiLC Project: An error * it’s, but which tag? In M. C. Campoy-Cubillo, B. Bellés-Fortuño, & M. L. Gea-Valor (Eds.), Corpus-based approaches to English language teaching (pp. 167–179). London: Continuum.

Google Scholar

Ashwell, T. (2000). Patterns of teacher response to student writing in a multiple-draft composition classroom: Is content feedback followed by form feedback the best method? Journal of Second Language Writing, 9 (3), 227–257.

Article Google Scholar

Barzilay, R., & Elhadad, N. (2003). Sentence Alignment for Monolingual Comparable Corpora. In Proceedings of the 2003 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing . Sapporo, Japan, pp. 25–32.

Biber, D., Nekrasova, T., & Horn, B. (2011). The effectiveness of feedback for L1-English and L2-writing development: A meta-analysis. TOEFL iBT research report.

Bitchener, J., & Ferris, D. R. (2012). Written corrective feedback in Second Language Acquisition and Writing . New York, NY: Routledge.

Burstein, J., Chodorow, M., & Leacock, C. (2004). Automated essay evaluation: The criterion online writing service. AI Magazine, 25 (3), 27–36.

Chandler, J. (2003). The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12 (3), 267–296.

Dahlmeier, D., & Ng, H. T. (2011). Grammatical error correction with alternating structure optimization. Proceedings of the 49th annual meeting of The Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 915–923). Stroudsburg, PA: ACL.

Dahlmeier, D., Ng, H. T., & Wu, S. M. (2013). Building a large annotated corpus of learner English: The NUS corpus of learner English. In Proceedings of the Eighth workshop on innovative use of NLP for building educational applications , 22–31.

Dale, R., & Kilgarriff, A. (2011). Helping our own: The HOO 2011 pilot shared task. In Proceedings of the 13th European Workshop on Natural Language Generation ( ENLG ). Nancy, France, 242–249.

Dipper, S. (2005). XML-based stand-off representation and exploitation of multi-level linguistic annotation. In Proceedings of Berliner XML Tage 2005 ( BXML 2005 ). Berlin, Germany, 39–50.

Eriksson, A., Finnegan, D., Kauppinen, A., Wiktorsson, M., Wärnsby, A., & Withers, P. (2012). MUCH: The Malmö University-Chalmers Corpus of Academic Writing as a Process. In Proceedings of the 10th teaching and language corpora conference .

Fathman, A. K. & Whalley, E. (1990). Teacher response to student writing: Focus on form versus content. In Kroll, B. (ed.) Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom , pp. 178–190.

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influence of teacher commentary on student revision. TESOL Quarterly, 31 (2), 315–339.

Ferris, D. R. (2006). Does error feedback help student writers? New evidence on the short-and long-term effects of written error correction. In K. Hyland & F. Hyland (Eds.), Feedback in second language writing: Contexts and issues (pp. 81–104). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ferris, D. R., & Roberts, B. (2001). Error feedback in L2 writing classes: How explicit does it need to be? Journal of Second Language Writing, 10 , 161–184.

Foster, J., Wagner, J., & van Genabith, J. (2008). Adapting a WSJ-trained parser to grammatically noisy text. In Proceedings of ACL.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99 (3), 445–476.

Granger, S. (1999). Use of tenses by advanced EFL learners: Evidence from error-tagged computer corpus. In H. Hasselgård (Ed.), Out of Corpora—Studies in Honour of Stig Johansson (pp. 191–202). Amsterdam, Atlanta: Rodopi.

Granger, S. (2004). Computer learner corpus research: Current status and future prospects. Language and Computers, 23 , 123–145.

Granger, S. (2008). Learner corpora. In A. Lüdeling & M. Kyto (Eds.), Corpus linguistics: An international handbook (Vol. 1). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Granger, S., Dagneaux, E., Meunier, F., & Paquot, M. (2009). The international corpus of learner English. Version 2. Handbook and CD - ROM . Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain.

Han, N.-R., Chodorow, M., & Leacock, C. (2006). Detecting errors in English article usage by non-native speakers. Natural Language Engineering, 12 (2), 115–129.

Ide, N., Bonhomme, P., & Romary, L. (2000). XCES: An XML-based encoding standard for linguistic corpora. Proceedings of the second international language resources and evaluation conference (pp. 825–830). Paris: ELRA.

Krause, T. & Zeldes, A. (2014). ANNIS3: A new architecture for generic corpus query and visualization. To appear in Literary and Linguistic Computing . http://dsh.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/12/02/llc.fqu057

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33 , 159–174.

Lee, J., & Seneff, S. (2008). An analysis of grammatical errors in nonnative speech in English. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Spoken Language Technology 2008 . pp. 89–92.

Lee, J., Tetreault, J., & Chodorow, M. (2009). Human evaluation of article and noun number usage: Influences of context and construction variability. In Proceedings of the Third Linguistic Annotation Workshop , pp. 60–63.

Lipnevich, A. A., & Smith, J. K. (2009). “I really need feedback to learn:” Students’ perspectives on the effectiveness of the differential feedback messages. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21 (4), 347–367.

Lüdeling, A., Doolittle, S., Hirschmann, H., Schmidt, K., & Walter, M. (2008). Das Lernerkorpus Falko. Deutsch als Fremdsprache, 2 , 67–73.

Lüdeling, A., Walter, M., Kroymann, E., & Adolphs, P. (2005). Multi-level Error Annotation in Learner Corpora. In Proceedings of Corpus Linguistics 2005 . Birmingham.

Lüdeling, A., & Hirschmann, H. (to appear). Error Annotation. In Granger, S., Gilquin, G., & Meunier, F. (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Learner Corpus Research . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marcus, M. P., Santorini, B., & Marcinkiewicz, M. A. (1993). Building a large annotated corpus of English: The Penn Treebank. Special Issue on Using Large Corpora, Computational Linguistics, 19 (2), 313–330.

Nagata, R., Whittaker, E., & Sheinman, V. (2011). Creating a manually error-tagged and shallow-parsed learner corpus. Proceedings of the 49th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (pp. 1210–1219). Stroudsburg, PA: ACL.

Nesi, H., Sharpling, G., & Ganobcsik-Williams, L. (2004). Student papers across the curriculum: designing and developing a corpus of British student writing. Computers and Composition, 21 (4), 439–450.

Nguyen, N. L. T. & Miyao, Y. (2013). Alignment-based annotation of proofreading texts toward professional writing assistance. In Proceedings of the international joint conference on natural language processing , pp. 753–759.

Nicholls, D. (2003). The Cambridge learner corpus: Error coding and analysis for lexicography and ELT. In Proceedings of the corpus linguistics 2003 conference .

Paulus, T. M. (1999). The effect of peer and teacher feedback on student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 8 (3), 265–289.

Polio, C., & Fleck, C. (1998). “If I only had more time:” ESL learners’ changes in linguistic accuracy on essay revisions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 7 (1), 43–68.

Reznicek, M., Lüdeling, A., & Hirschmann, H. (2013). Competing target hypotheses in the Falko corpus: A flexible multi-layer corpus architecture. In A. Díaz-Negrillo, N. Ballier, & P. Thompson (Eds.), Automatic treatment and analysis of learner corpus data (pp. 101–124). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rosen, A., Hana, J., Stindlova, B., & Feldman, A. (2014). Evaluating and automating the annotation of a learner corpus. Language Resources and Evaluation, 48 , 65–92.

Rozovskaya, A., & Roth, D. (2010). Annotating ESL errors: Challenges and rewards. In: Proceedings of NAACL’10 workshop on innovative use of NLP for building educational applications .

Russell, J., & Spada, N. (2006). The effectiveness of corrective feedback for the acquisition of L2 grammar: A meta-analysis of the research. In J. Norris & L. Ortega (Eds.), Synthesizing research on language learning and teaching (Language learning and language teaching 13) (pp. 133–164). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Shemtov, H. (1993). Text Alignment in a Tool for Translating Revised Documents. Proceedings of the sixth conference on European chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (EACL-93) (pp. 449–453). Stroudsburg, PA: ACL.

Snover, M., Dorr, B., Schwartz, R., Micciulla, L., & Makhoul, J. (2006). A study of translation edit rate with targeted human annotation. In Proceedings of the 7th conference of the association for machine translation in the Americas . Cambridge, MA, pp. 223–231.

Tetreault, J. R., & Chodorow, M. (2008). Native judgments of non-native usage: Experiments in preposition error detection. In Proceedings of the workshop on human judgements in computational linguistics , pp. 24–32.

Toutanova, K., Klein, D., Manning, C. D., & Singer, Y. (2003). Feature-rich part-of-speech tagging with a cyclic dependency network. Proceedings of the 2003 conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Human Language Technology (NAACL-HLT 2003) (pp. 252–259). Stroudsburg, PA: ACL.

Toutanova, K., & Manning, C. D. (2000). Enriching the knowledge sources used in a maximum entropy part-of-speech tagger. In Proceedings of the 2000 joint SIGDAT conference on empirical methods in natural language processing and very large corpora . Hong Kong, pp. 63–70.

Truscott, J. (1996). The case against grammar correction in L2 writing classes. Language Learning, 46 (2), 327–369.

Truscott, J., & Hsu, A. Y.-P. (2008). Error correction, revision, and learning. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17 (4), 292–305.

Webster, J., Chan, A., & Lee, J. (2011). Introducing an online language learning environment and its corpus of tertiary student writing. Asia Pacific World, 2 (2), 44–65.

Wible, D., Kuo, C.-H., Chien, F.-L., Liu, A., & Tsao, N.-L. (2001). A web-based EFL writing environment: Integrating information for learners, teachers, and researchers. Computers & Education, 37 (3–4), 297–315.

Zeldes, A., Ritz, J., Lüdeling, A., & Chiarcos, C. (2009). ANNIS: A search tool for multi-layer annotated corpora. In Proceedings of corpus linguistics 2009 . Liverpool, UK.

Zipser, F., & Romary, L. (2010). A model oriented approach to the mapping of annotation formats using standards. Proceedings of the workshop on language resource and language technology standards, LREC-2010 (pp. 7–18). Malta: Valletta.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The work described in this article was supported by a grant from the Germany / Hong Kong Joint Research Scheme sponsored by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong and the German Academic Exchange Service (Reference No. G_HK013/11).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

John Lee, Chak Yan Yeung & Jonathan Webster

Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA

Amir Zeldes

Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

Marc Reznicek

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Anke Lüdeling

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to John Lee .

Appendix: Error categories

The complete list of the error categories Footnote 13 used in our corpus, with example sentences, are shown in Table 10 . The text span addressed by the error category is enclosed in square brackets. For some of the categories, we provide an explanation rather than an example because of space constraints.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lee, J., Yeung, C.Y., Zeldes, A. et al. CityU corpus of essay drafts of English language learners: a corpus of textual revision in second language writing. Lang Resources & Evaluation 49 , 659–683 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-015-9301-z

Download citation

Published : 18 April 2015

Issue Date : September 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-015-9301-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Learner corpus

- Textual revision

- English as a second language

- Multi-layer corpus annotation

- Corpus search and visualization

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

CityU Scholars A Research Hub of Excellence

System upgrade will be carried out on 12 Oct 2023 (Thu) from 9:00 pm to 10:00 pm (HK Time) . The system will not be available during this period.

- Researchers

- Research Units

- Research Output

- Prizes/Honours

- Student Theses

- Press/Media

CityU corpus of essay drafts of English language learners : a corpus of textual revision in second language writing

Research output : Journal Publications and Reviews › RGC 21 - Publication in refereed journal › peer-review

Fingerprint

Arts & humanities, social sciences.

Theses and Dissertations

- Find CityU theses and dissertations

- Find Hong Kong theses and dissertations

- Find global theses and dissertations

- Can't find the full text of theses and dissertations?

- Use CityU LibraryFind to find theses and dissertations

Information for CityU students

Writing guides and more, guides on the web, recommended books about writing theses and dissertations.

- Regulations Governing the Format of Theses (p.105 - Appendix 13) Prepared by the Chow Yei Ching School of Graduate Studies, City University of Hong Kong.

- Resources & Support Compiled by the Chow Yei Ching School of Graduate Studies, City University of Hong Kong. It contains information on services, facilities, training, and advice for postgraduate students.

- Guidelines for Electronic Theses and Dissertations It states the University policy on electronic theses and gives guidelines on formatting, creating, and submitting them.

You can use the subject headings below to find books, e-books, and more on writing theses and dissertations in CityU LibraryFind .

- Academic writing -- Handbooks, manuals, etc.

- Dissertations, Academic

- Dissertations, Academic -- Authorship

- Dissertations, Academic -- Handbooks, manuals, etc.

- Report writing -- Handbooks, manuals, etc.

- Research -- Methodology -- Handbooks, manuals, etc.

- Research -- Methodology

- Qualitative research

- Quantitative research

- Questionnaires

- How-to guides: Expert guidance for authors, editors, reviewers, researchers and students (by Emerald Publishing Limited)

- UNCOVER the value of dissertations (by ProQuest LLC)

- Writing and presenting your thesis or dissertation (by S. Joseph Levine, Michigan State University)

Books with call number LB2369 are on writing dissertations and theses.

- << Previous: Use CityU LibraryFind to find theses and dissertations

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 7:25 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.cityu.edu.hk/thes

© City University of Hong Kong | Copyright | Disclaimer

The Spinoff

The Sunday Essay March 17, 2024

The sunday essay: how we make great cities, and how cities make us great.

- Share Story

Seven thousand years ago, the world’s first city was born. New Zealand is still learning its lessons.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

T he anchor splashed through the waves, sinking deep into the great harbour of Tara. Wind and rain hammered the sides of the ship. Its hull creaked from the brunt of 126 days at sea.

On January 20, 1840, the Aurora set anchor just off Matiu/Somes Island, carrying 148 British settlers, the first organised European immigration by the New Zealand Company. The storm continued to rage for two days before they could make it to shore. When the conditions finally turned, there was a mad scramble for Petone beach. Row boats ferried passengers aboard, frantically tossing possessions onto the land. Māori from Pito-one Pā, led by Te Puni, helped get people ashore and built makeshift houses.

It was a brief moment of harmony; two peoples supporting each other. It wouldn’t last. Te Puni eventually realised the New Zealand Company lied to him about the nature of land sales and just how many Pākehā were on their way. The British settlers also felt betrayed by the company: the land they were sold was in the floodplains of the Hutt River. After the waters wiped out most of the original settlement, the settlers picked up sticks and moved to the other side of the harbour, to the current site of Wellington.

That chaotic day on Petone beach was the start of an ambitious project, a rag-tag group of people trying to do something that had never before been done on New Zealand shores: build a city. New Zealand was the last significant landmass ever populated by humans. It had never played host to a city. The largest human settlement before then was probably the pā on Maungakiekie in Tāmaki Makaurau, which housed about 5,000 people in the 17th century.

Most of the British settlers had never lived in a city either. The majority were picked because they had experience as rural labourers and knew how to work the land. Creating a city from scratch was a huge task, and none of them really knew what they were doing.

Even 184 years later, Wellington is still in the very early stages of this immense, continually evolving project. Compared to the century- and millennia-old cities which dominate the world’s economy and culture today like London, Beijing and New York, Wellington (like all New Zealand cities) is a mere toddler, taking its first shaky steps towards urbanisation.

Wellington’s new District Plan marks the next step for a city that is slowly growing into its ambition to be a global city of impact . The evolution from large provincial towns to truly urban, high-functioning cities is New Zealand’s greatest economic challenge of the 21st century. It’s the step that will take us from an economy based on agriculture and natural resources to one based on productive high tech and creative industries. To help chart our way forward, it’s worth looking back to the birth of cities.

S even thousand years ago, on the banks of the Euphrates River in what is now Iraq, humans were grappling with the promises and challenges of cities for the very first time. The world’s first city (depending how you define it) was named Uruk.

Archaeologists are still uncovering Uruk’s stories, but we know it was the centre of a vast, prosperous trade network, with enormous central markets. There was a large class of bureaucratic officials who managed city business. There is evidence of mass production, with an industry manufacturing thousands of clay bowls . It was an agricultural juggernaut, with huge canals and irrigation projects, capable of growing a food surplus to feed the entire city population, and keep stockpiles for bad seasons.

Uruk generated more resources than its residents could have accumulated individually. It was a world of new possibilities: novel foods and clothes, new forms of entertainment and different kinds of jobs. Even people who lived outside Uruk’s walls benefited from its manufacturing, markets, ports and agricultural systems.

Cities, according to Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, are “ man’s greatest invention ”. They are the most powerful engine of trade, production, collaboration and social mobility ever created. “There is a near-perfect correlation between urbanisation and prosperity across nations,” he wrote in his book, Triumph of the City.

After Uruk was born, other cities started popping up with increasing speed across Mesopotamia. Great cities also developed independently in India, China and the Americas. Humans are social animals. We are more likely to survive in the wild as part of a tribe than alone. The larger the tribe or community, the more support it provides. Cities are just the natural extension of that. When we create systems that allow as many humans as possible to collaborate in relative harmony, people tend to thrive. In the same way that bees create hives, humans create cities. They are the human habitat.

So, when exploring the foundations of cities and how to build a great one, it makes sense to ask: what is a city? It’s a surprisingly hard question to answer. There is no consistent definition other than a human settlement of some notable size. Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin each claim to be New Zealand’s “first city” for different technical reasons.

There are few geographical or physical rules that are true across all cities. They exist on coastlines and inland, on rivers and in deserts, on the flat and in mountains. Cities don’t even need to be built on land: Venice is in a lagoon, and Tenochtitlan, the centre of the Aztec empire, was built in a lake.

Even in terms of their economic functions, cities don’t have much in common. They can be centred around ports, manufacturing, government or tourism. But when you compare a city to a town or village, they all have one advantage: more people.

Cities aren’t made of roads and buildings, they’re made of people. He tāngata, he tāngata, he tāngata. People come to cities for connection, they want to find partners, attend mass entertainment events and do business. In pure economic terms, a city is a labour market. In a large labour market, there are more workers available for big, complex projects. Businesses can find highly skilled workers to fill specialist roles. Workers are more likely to find the job that best uses their skills. Companies looking to open a new factory or office will choose to do so in cities with strong labour markets. People from outside a city will move there to access the jobs, making the labour market even larger and more appealing.

Even in the world of Zoom calls and international flights, this hasn’t changed. The most powerful cities are built on large, skilled labour forces.

U ruk developed a large class of skilled bureaucrats, scribes and accountants who were responsible for Uruk’s most important contribution to human civilization: writing. Refining pictograms into a complex system of words and letters would have taken a huge amount of shared knowledge to develop, codify and spread the new system of communication. It’s the kind of innovation that could only be made possible in a city. It was also something that only a city would require.

In a village, you could get by on your word. Disagreements could be hashed out in person, in front of a local leader. Uruk’s trade, farming and public works were far too complex to run on memory. Writing was a necessity. This is the natural problem of a city. Large cities are more productive and more powerful, but they are also far more complex and difficult to manage.

The earliest known codes of laws started to be developed during the Uruk period, the archaeological term for the period when Uruk was the dominant city in Mesopotamia. The code of Urukagina, the oldest known code of laws, was developed in the nearby city of Lagash, about 50km away from Uruk.

The actual text hasn’t been discovered, but archaeologists have managed to piece it together from references in other documents. It was an effort to manage the risks of corruption and inequality that inevitably arise in a large city. It restricted the powers of priests and large property owners. It outlawed unfair loans, established welfare payments and set rules for fair trading: the rich had to use silver when purchasing from the poor, and couldn’t force a poor person to sell something they didn’t want to sell.

The code also dealt with some of the more mundane details of city life: setting the price for tolls on the city gate and determining how much city officials would be paid and who was exempt from paying taxes.

The code of Urukagina was complex because cities are complex. They need streets, pipes and some form of funding. A small town can be run by a part-time council, a large city requires a massive machine of public servants. All of these complexities come from people. The greatest complexity of all is this: where should all these people live, and how should they move around?

U ruk was surrounded by 9.5km of brick walls five metres high, containing an area of 450 hectares. The walls protected the people from invaders and demarcated the city’s expansion. By coincidence, the original town plan for Wellington was almost the exact same size: 1,100 residential blocks of one acre each (445 hectares).

For most of human history, the maximum size of a city was pretty static: it was determined by how far someone could conveniently walk. The only way to grow a city’s population within those constraints was to increase density by subdividing lots or building taller homes.

That’s roughly the plan Wellington followed. Over the course of the 19th and early 20th century, those one-acre blocks became smaller and smaller to cater to the growing population. Te Aro became a slum, filled with tiny shacks and choked by the smoke of industrial furnaces and garbage incinerators . There were outbreaks of typhoid and other water-borne diseases. People who were wealthy enough bought large homes in the city fringe suburbs to escape the destitution.

The same problem would have been faced by Uruk and every other major city in history. When the population is growing but the city doesn’t have the right systems in place to deal with it, quality of life plummets, especially for the poorest residents. Even ancient cities eventually realised the only way to keep growing was to build up. Large apartment buildings called insulae were common in ancient Rome. There is evidence of multi-storey homes dating back to Jericho in 7000BC . But apartments are difficult, both architecturally and politically. They’re expensive and complicated to build, and often draw backlash from angry locals afraid of being crowded out of their own neighbourhoods.

There is one way to keep your city population growing without fully embracing density: expand outwards. In order to do that, you need some form of transport that is faster than walking and which will still allow people to get to the centre of the city. In some ancient cities, that meant ferries and canal boats. In Wellington, it initially meant streetcars, the cable car, and train lines.

Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch grew up in the post-war boom characterised by two intertwining trends: first, a huge government effort to build state homes, which accelerated the shift towards quarter-acre sections and sprawling suburbs that became New Zealand’s default way of life. Second, and more significantly, the rise of privately owned cars. Once cars became affordable for the middle class, it became more attractive to buy cheap land on the outskirts of town and drive to work in the city. New bridges and motorways, rather than trains, have been the dominant form of urban expansion in New Zealand for the past 70 or so years.

But there are many problems with that form of growth. Car-dependent sprawl created more carbon emissions. It was more expensive, due to the cost of both petrol and parking. Suburbs hollowed out the city centres. We started using phrases like “central business district” because no one actually lived in them, they were just places to do business.

Cars are big, and keep getting bigger. We are running out of places to put them. They need big roads to drive on and carparks to store them in. There is only so much space on our public streets that we can dedicate to storing private vehicles. Commuting by bus, train or tram doesn’t require each passenger to store their own personal vehicle. Bikes and e-scooters are far smaller and more space efficient.

Even with our current car-dependent city design, there is still a limit of how far most people are willing to drive every day. A commute of 45 minutes has such a negative impact on quality of life that economists found you have to earn 20 percent more to make the trip worth it . For a while, cars allowed us to make our city walls wider, but the walls still exist.

After ignoring the big, thorny problem of density for a couple of generations, our cities are finally circling back to it. We can’t keep creating low-density suburbs further and further away from the city centre. Creating bigger, more powerful labour markets requires denser forms of housing and more space-efficient forms of transport.

There is good news, though. Wellington, like most cities in New Zealand and the western world, is post-industrial. The city centre is no longer choked by smelly factories and furnaces. It’s a lot nicer now. There are glass offices, cafes and craft beer bars. There is a booming population of young people who want the opportunity to experience all that city living has to offer.

This is the next great urban reset, and it’s already beginning. The world’s leading cities, such as London, Paris and New York, are moving towards a new future with more people living closer to town in higher quality apartments, with more energy and space-efficient transport. Those cities have all invested massively in cycling infrastructure over the last few years. They have realised you can’t have a large, dense city where everyone wants to drive through the centre of town; there simply isn’t enough room. It’s inefficient transport and it ruins the amenity of the streets. They’re ready for the next evolution of the city.

U ruk was the birthplace of the world’s oldest surviving work of written literature . The Epic of Gilgamesh tells the story of Gilgamesh, a legendary king of Uruk, who represents the luxury (and corruption) of city life. His rival, Enkidu, is a wild man who represents the freedom and chaos of nature. The two start out as enemies, but eventually become friends and allies in a quest to defeat the demon Humbaba. The themes of the story show how the people of Uruk grappled with their place in the world, trying to make sense of this new style of city living, which was such a sharp departure from how humans had existed for millennia, working the land as subsistence farmers or hunter-gatherers.

New Zealand today is still grappling with that same challenge. Our national identity has always been rural. We are the country of Footrot Flats, Fred Dagg and number eight wire. Our economy has been driven by natural resources: first moa and pounamu, then harekeke and kauri, gold and coal, and now grazing land for sheep and cows. Those resources have served us well. But natural resources won’t take us forward. The next great leap will be in information, creativity and technology; the economy of the city.

More Reading

Figuring out how to design highly efficient and productive cities is New Zealand’s next great challenge. If we get it right, Wellington, Auckland and Christchurch will become powerful economic engines, capable of lifting prosperity and quality of life for everyone. If we get it wrong, we’ll squander our potential.

Uruk ’s peak of importance lasted for about 2,000 years. Since then, thousands of cities have grown up all around the world. Many of today’s greatest cities have stood for thousands of years; Paris, Constantinople, Delhi and Beijing are all far older than the countries they are in. If we learn the lessons of history, New Zealand’s cities may someday be thought of in the same breath.

America’s Suburban Crime Problem

A fter several years of rising crime, big city mayors and police chiefs across the country are breathing a sigh of relief. Statistics published by the Council of Criminal Justice and other recent analysis show the number of homicides and aggravated assaults fell by a respective 10% and 3% in big cities in 2023 compared to 2022, though the rates remain higher than in pre-pandemic years.

These are hopeful signals. If these trends persisted on a national scale, this could indicate violent crime markets have retracted. But declarations that violent crime is falling miss important—and disturbing—crime trends data that paint a much more complicated picture. While big city crime may be falling, suburban crime may be rising. More surprising still, crime in rural areas appears to be rising even faster—and a much higher share of this crime involves strangers and guns.

These startling findings come from an important but underappreciated nationally representative data source—the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS)—that includes crimes not reported to police. Along with last year’s big city estimates, the latest figures from the FBI's 2022 UCR program gathered from police reports, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics' NCVS report drawn from interviews with households, present a complex narrative that does more than merely highlight differences in data collection methods but unveils a nuanced and evolving picture of violent crime in the U.S.

Besides a slight rise in robbery rates from 65.5 to 66.1 per 100,000 residents, the UCR program suggests a national decrease in both the rates of fatal (homicide) and non-fatal felony violence (rape, robbery, and aggravated assault) from 2021 to 2022. In contrast, the NCVS shows an increase in non-fatal felony violence, with victimizations per 1,000 persons over the age of 12 increasing from 5.6 in 2021 to 9.8 in 2022, primarily due to a doubling of aggravated assault rates. NCVS estimates imply that a substantial portion of crime remains unreported, the so-called " dark figure " of crime that eludes the detection of law enforcement.

A clearer picture of who is at greatest risk for violent victimization emerges when analyzing crime rates by location. The NCVS shows that the traditional boundaries between urban and non-urban violence are dissolving. Suburban and rural areas, once considered safe havens, are now confronting a jump in non-fatal violent crime, fundamentally changing the geography of public safety.

The robbery rate in urban centers increased by 21% over the three years, driven largely by the 78% increase between 2021 and 2022. Looking at the suburbs, the 2022 increase in robbery rates hit 21%, contributing to the 40% increase through 2021. In the rural areas where the American dream of pastoral peace is most cherished, robbery rates rose by 44% in 2022 after a two-year decline.

This shift is further accentuated in the rates of aggravated assault, which have not only risen in urban areas but have skyrocketed in non-urban areas. In urban centers, these assaults have risen by 51% in a single year from 2021 to 2022. Looking back at the suburbs and rural areas, the respective increases were even more pronounced with rates over nearly three times and two times higher in 2022 than in 2021.

Gun violence also increased and spread across geographies. The gun-related victimization rate in urban centers increased by 1.3 per 1,000 in 2022 compared to the previous year, reaching 2019 levels after a decrease. This rate doubled over the past two years in the suburbs and is slightly higher than in 2019, while in rural areas, there was a surge in non-fatal gun violence rates, with approximately 66,000 more reported victimizations between 2021 and 2022, returning to rates last observed in 1997.

Research suggests most violent crimes are committed by someone the victim knows such as friends, acquaintances, and relatives. This remains the case, but estimates indicate strangers are responsible for more violent crimes, especially in non-urban centers. After decreases in the number of violent felony victimizations involving strangers from 2019 to 2021, all areas experienced large increases by 2022. For this one-year period, these types of victimizations climbed by 37% in urban areas, 73% in the suburbs, and more than doubled (102%) in rural locales.

Read More: If We Want to Reduce Deaths at Hands of Police, We Need to Reduce Traffic Stops

Breaking down the data by race adds a layer of complexity to the narrative. White Americans have seen a marked increase in victimization, particularly in urban areas, reversing previous declines. From 2021 to 2022, violent felony victimization for this group rose by 75% in urban areas, 93% in suburban areas, and 62% in America’s countryside.

For Black Americans, the pattern is more complex, with an initial rise in urban victimization rates followed by a 20% decrease from 2021 to 2022. However, the increase in violent felonies in suburban areas paints a troubling picture of the changing risks these communities face. For Black Americans residing in the suburbs, the rate of violent felonies spiked 74% over the three years, with a sharp leap of 172% from 2021 to 2022. Outside the metropolitan centers, the three-year increase is less dramatic (29%) but still alarming.

The rise in violent crime comes at a time of historic domestic migration . During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns, people and families relocated from cities to the suburbs and rural locales, motivated by the flexibility of remote work and the desire for safer, more affordable, and more spacious living environments. Studies have found that violent victimization influences residential mobility, but it appears more factors are at play. As people migrate, they not only bring their dreams and aspirations but also create economic tensions and cultural integration challenges that can ferment crime and complicate public safety efforts. It's in this intersection of mobility and security that we must revisit our approach to crime prevention and intervention.

Although the Justice Department's Roadmap provides resources based on the Ten Essential Actions Cities Can Take to Reduce Violence Now , developed by the Council on Criminal Justice, the evidence is mostly from studies conducted in urban areas. Efforts to reduce violent crime in non-urban areas face challenges such as limited resources, large territories that inhibit community engagement and response times, despite initiatives like the BJA’s Rural and Small Department Violent Crime Reduction Program that collaborate with law enforcement agencies (LEAs) to develop strategies addressing these issues and Crime Analyst in Residence program intended to assist LEAs in enhancing their operational and procedural management through the utilization of data analysis and analytics.

This shift observed in the NCVS also calls for examination of the racial differences in victimization rates—particularly the heightened vulnerability of white Americans in urban settings and the complex pattern of rising and then decreasing rates for Black Americans.

Further research is needed to address gaps and uncertainties in the valuable insights provided by NCVS, particularly with regards to how victimization rates influence residential mobility within urban centers, the potential underestimation of victimization among Black people, and the variations within different areas. It is imperative to also examine the challenges posed by response rates to the NCVS, especially among hard-to-reach populations.

Meanwhile, NCVS estimates force us to seriously consider that criminal violence might be evolving rather than declining, necessitating the development and adoption of effective strategies like proven community violence reduction initiatives as well as housing, public health, and employment programs adapted to the particular needs and strengths of suburban and rural communities. Otherwise, there is a danger of resourcing and implementing urban-centric, pre-pandemic strategies in a post-pandemic world that misses the opportunity to improve community safety across racial and geographic divides.

While the recent data suggests a decrease in urban crime, many Americans still feel uneasy. It's conceivable that the pronounced changes in victimization, particularly in suburban and rural areas, have heightened this sense of vulnerability. The discrepancy between the actual numbers and public perception challenges us to consider the changing geography of crime and the impact it has on the nation's sense of security.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- The Long, Strange History of Secret Royal Ailments

- The UAE Is on a Mission to Become an AI Power

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Listen to the 2024 winners of Bloomington's Black history essay contest

The City of Bloomington has announced this year's winners of its annual Black History Essay Contest. You'll hear them over the next week on WGLT's Sound Ideas , or you can listen on-demand below.

High School

1st Place: Kh'Mara Bowie is a senior at Bloomington High School in District 87. Bowie takes inspiration from someone in the music world who cuts against common stereotypes.

2nd Place: Heaven'lee Anne Henderson-O'Brien,15, is a ninth grader at Normal West high school in Unit 5. Henderson-O'Brien tells a famous story, a horrible story of racial violence, and a story she believes must not be forgotten. Note: This reading includes graphic descriptions of violence and racial epithets.

Middle School

1st Place: Sarah Guo is a seventh grader at Evans Junior High School in Unit 5. Guo lifts up an early conservationist from undeserved obscurity.

2nd Place: Aaliyah Mohapatra is a seventh grader at Chiddix Junior High School in Unit 5. Mohapatra's essay recognizes a poet, a soldier, and an abolitionist author.

Elementary School

1st Place: Josllyn Brooks is a sixth grader at Bloomington Junior High School in District 87. In her essay, Brooks tells of a towering figure who broke barriers in sports and society.

2nd Place: Erioluwa Jegede is a fourth-grade student at Oakland Elementary School in District 87. Jegede honors a number of historical figures and the lessons they have for him.

3rd place winner: Elena Serrano, a sixth grader at BJHS, was not able to record her essay.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

3 men charged with federal firearms counts after Kansas City Chiefs Super Bowl parade shooting

FILE - Police clear the area following a shooting at the Kansas City Chiefs NFL football Super Bowl celebration in Kansas City, Mo., Wednesday, Feb. 14, 2024. Three men from Kansas City, Mo.,, face firearms charges, including gun trafficking, after an investigation into the mass shooting during the Kansas City Chiefs’ Super Bowl parade and rally, federal prosecutors said Wednesday, March 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Reed Hoffmann, File)

FILE - People view a memorial, Sunday, Feb. 18, 2024, in Kansas City, Mo., dedicated to the victims of a shooting at the Kansas City Chiefs NFL football Super Bowl celebration. Three men from Kansas City, Mo.,, face firearms charges, including gun trafficking, after an investigation into the mass shooting during the Kansas City Chiefs’ Super Bowl parade and rally, federal prosecutors said Wednesday, March 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel, File)

- Copy Link copied

Three Missouri men have been charged with federal counts related to the illegal purchase of high-powered rifles and guns with extended magazines after last month’s shooting at the Kansas City Chiefs’ Super Bowl parade and rally left one person dead, roughly two dozen others injured and sent hundreds of people scrambling for cover, federal prosecutors said Wednesday.

Court documents unsealed Wednesday said 12 people brandished firearms and at least six people fired weapons at the Feb. 14 rally, which drew an estimated 1 million people to downtown Kansas City. The guns found at the scene included at least two AR-15-style rifles, court documents said. And U.S. Attorney Teresa Moore said in a news release that at least two of the guns recovered from the scene were illegally purchased.

The federal charges come three weeks after state authorities charged two other men, Lyndell Mays and Dominic Miller, with second-degree murder and several weapons counts for the shootings. Authorities also last month detained two juveniles on gun-related and resisting arrest charges . Police said the shooting happened when one group of people confronted another for staring at them.

Authorities have said a bullet from Miller’s gun killed Lisa Lopez-Galvan , who was in a nearby crowd of people watching the rally. She was a mother of two and the host of a local radio program called “Taste of Tejano.” The people injured range in age from 8 to 47, according to police.

Named in the new federal charges were 22-year-old Fedo Antonia Manning, Ronnel Dewayne Williams Jr., 21, and Chaelyn Hendrick Groves, 19, all from Kansas City. Manning is charged with one count each of conspiracy to traffic firearms and engaging in firearm sales without a license, and 10 counts of making a false statement on a federal form. Williams and Groves are charged with making false statements in the acquisition of firearms, and lying to a federal agent.

According to online court records, Manning made his initial appearance Wednesday. He did not have an attorney listed, but asked that one be appointed for him. The online court record for Williams and Groves also did not list any attorneys to comment on their behalf.

A phone call to the federal public defender’s office in Kansas City on Wednesday went unanswered.

The new complaints made public Wednesday do not allege that the men were among the shooters. Instead, they are accused of involvement in straw purchases and trafficking firearms.

“Stopping straw buyers and preventing illegal firearms trafficking is our first line of defense against gun violence,” Moore said in the news release.

Federal prosecutors said that one weapon recovered at the rally scene was an Anderson Manufacturing AM-15 .223-caliber pistol, found along a wall with a backpack next to two AR-15-style firearms and a backpack. The release said the firearm was in the “fire” position with 26 rounds in a magazine capable of holding 30 rounds — meaning some rounds may have been fired from it.

The affidavit stated that Manning bought the AM-15 from a gun store in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, a Kansas City suburb, on Aug. 7, 2022. It accuses him of illegally trafficking dozens of firearms, including many AM-15s.

Also recovered at the scene was a Stag Arms 300-caliber pistol that the complaint said was purchased by Williams during a gun show in November. Prosecutors say Williams bought the gun for Groves, who accompanied him to the show but was too young to legally purchase a gun for himself.

Prosecutors say Manning and Williams also bought firearm receivers, gun parts also known as frames that can be built into complete weapons by adding other, sometimes non-regulated components.

The complaint said Manning was the straw buyer of guns later sold to a confidential informant in a separate investigation.

___ Jim Salter in St. Louis and Lindsey Whitehurst in Washington, D.C., contributed to this report.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

New York’s Subway Is Still Not Safe, but Not for the Reason You Think

By Julie Kim

Ms. Kim is a writer who lives in Brooklyn.

A few months before Gov. Kathy Hochul ordered some 1,000 members of the state police and National Guard to patrol New York City’s subway system in response to a string of violent attacks, some of them deadly, I had an unsafe subway experience of my own. It didn’t involve crime — unless you’d call the system’s shameful lack of elevators and accessible stations criminal.

An infection in my 10-year-old son’s leg required us to make regular trips from our Brooklyn home to a hospital on East 71st Street in Manhattan. He had been getting around on crutches, but these trips were long, so, much to his embarrassment, I loaded him into his younger sister’s stroller and wheeled him to the nearest accessible subway station, at Atlantic Avenue.

On a good day, it takes three elevator rides to get from street to platform. We entered the first, a dirty green box tacked onto the side of a warehouse, then wheeled to and entered the second, another metal box reeking of urine and industrial cleaning fumes. When we finally got to the third, we discovered it was out of service.

Before I knew it, my son had stood up on his one good leg and, without his crutches, hopped down several steps, around a corner and down a few more. I followed him to the bottom of the stairs, carrying the empty stroller, where he waited, teetering in the center of the narrow platform. I scooped him back into the stroller and stayed put, not daring to further navigate the treacherous strip between the broken elevator and the tracks. We’d made it to the platform safely, but our trip involved far more danger than we expected.

There was a political logic to Ms. Hochul’s decision to deploy troops; it was a response to heightened safety fears among subway riders and workers. When citizens feel unsafe, politicians and city officials tend to act fast to quell those fears. To explain the sudden presence of soldiers in the subway, she described subway crime as “not statistically significant but psychologically significant.”

For millions of commuters, the current state of the system is an urgent safety matter, too. Nearly three-quarters of the city’s 472 stations don’t have elevators, leaving millions of New Yorkers — including older people, the disabled and caregivers with young children — with no choice but to avoid the subway altogether. This issue affects far more New Yorkers than does violent crime, but it is treated much less urgently. The number of New Yorkers age 65 and older has increased by 40 percent since 2000, already surpassing the Bloomberg administration’s projection of 1.35 million by 2030. More than 500,000 New Yorkers have a temporary or permanent disability that makes it difficult for them to walk.

The dangers caused by our broken, inaccessible transportation system are very real, but they don’t often make headlines, perhaps in part because they are hard to measure — an unreported tumble on the subway stairs, the monetary, physical or psychic toll of delayed or canceled trips, errands left undone or the exhausting, harrowing and sometimes painful trials faced by vulnerable commuters. Our family has felt some of these costs: I haven’t taken the subway with my 6-year-old daughter, who has permanent disabilities that require her to use a wheelchair or a stroller every day, for nearly three years. The last time I carried her down the stairs leading to an inaccessible station, I felt something pop in my back. My response has been to avoid riding the subway with her. But the effects of this poorly maintained system affect a broad range of New Yorkers, far beyond those who use wheelchairs.

The lack of elevators in the subway system is not just a matter of the city meeting a legal obligation to make public spaces accessible. It is also a safety issue that should be treated with the same urgency as crime, if not more.

It’s true that state and city officials are working — albeit defensively and slowly — to fix the subway’s accessibility problem. To settle two class-action lawsuits, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority agreed in 2022 to spend billions of dollars to bring 95 percent of stations into compliance with accessibility and safety standards of the federal Americans With Disabilities Act — by 2055. The agency’s plan is crawling along at a pace of roughly 10 station upgrades per year; occasionally, a project gets bolstered by an infusion of federal funds.

In the meantime, older riders are walking backward down stairs into stations; disabled residents who cannot enter stations without an elevator are relegated to inefficient buses or a paratransit ride-share service known for its hourslong trips and leaving passengers stranded . Caregivers of children and adults with mobility limitations risk injury or keep their orbits small.

New Yorkers are all the more impatient for the M.T.A. to fix this because we’ve seen how quickly and effectively officials can act when there’s political will behind fixing a problem — Governor Hochul’s quick mobilization of troops and officers is a case in point. And we’ve seen what can happen when the system works.

When my son and I got off at the Q station on East 72nd Street in Manhattan, it was like entering another world. It was my first time there since it opened in 2017 as part of the century-long Second Avenue subway expansion. The train doors opened onto a spacious and well-lit platform. I paused in the center to get my bearings: We were far underground, yet the space felt open and airy. The Q train had delivered us directly into an accessible waiting area, in front of the entrance to a steel-and-glass elevator with grab bars and generous clearance on all sides — margins wide enough for a person using a wheelchair, stroller, crutches, cane or walker to safely pass or for someone to hold a (small) dance party. We boarded with a delivery person and his bicycle, and the inside smelled as it should, like nothing. Up on the mezzanine, a Taylor Swift song played softly over the speakers.

My son looked up from his book. “Where are we?” he asked. We made our way to the turnstiles; the station agent saw us coming and activated the automatic emergency gate. Passing through it, I stood taller, like royalty. A short, wide corridor led to the elevators — five of them in a row — the station’s crown jewels. We waited alongside others — older couples, AirPodded commuters, the delivery person and his bike. Within seconds, three elevators arrived. We scurried into one of them with two other people; the lucky delivery person got his own.

The door closed, and we were lifted gently up to the street, a ride that any New Yorker or visitor would have appreciated and that should not have felt so precious.

Julie Kim is a writer living in Brooklyn and working on a book about everyday acts of inclusion.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

- The Magazine

- City Journal

- Contributors

- Manhattan Institute

- Email Alerts

Harvard Tramples the Truth

When it came to debating Covid lockdowns, Veritas wasn’t the university’s guiding principle.

I am no longer a professor of medicine at Harvard. The Harvard motto is Veritas, Latin for truth. But, as I discovered, truth can get you fired. This is my story—a story of a Harvard biostatistician and infectious-disease epidemiologist, clinging to the truth as the world lost its way during the Covid pandemic.

On March 10, 2020, before any government prompting, Harvard declared that it would “suspend in-person classes and shift to online learning.” Across the country, universities, schools, and state governments followed Harvard’s lead.

Yet it was clear, from early 2020, that the virus would eventually spread across the globe, and that it would be futile to try to suppress it with lockdowns. It was also clear that lockdowns would inflict enormous collateral damage, not only on education but also on public health, including treatment for cancer, cardiovascular disease, and mental health. We will be dealing with the harm done for decades. Our children, the elderly, the middle class, the working class, and the poor around the world—all will suffer.

Schools closed in many other countries, too, but under heavy international criticism, Sweden kept its schools and daycares open for its 1.8 million children, ages one to 15. Why? While anyone can get infected, we have known since early 2020 that more than a thousandfold difference in Covid mortality risk holds between the young and the old. Children faced minuscule risk from Covid, and interrupting their education would disadvantage them for life, especially those whose families could not afford private schools, pod schools, or tutors, or to homeschool.

What were the results during the spring of 2020? With schools open, Sweden had zero Covid deaths in the one-to-15 age group, while teachers had the same mortality as the average of other professions. Based on those facts, summarized in a July 7, 2020, report by the Swedish Public Health Agency, all U.S. schools should have quickly reopened. Not doing so led to “ startling evidence on learning loss” in the United States, especially among lower- and middle-class children, an effect not seen in Sweden.

Sweden was the only major Western country that rejected school closures and other lockdowns in favor of concentrating on the elderly, and the final verdict is now in. Led by an intelligent social democrat prime minister (a welder), Sweden had the lowest excess mortality among major European countries during the pandemic, and less than half that of the United States. Sweden’s Covid deaths were below average, and it avoided collateral mortality caused by lockdowns.

Yet on July 29, 2020, the Harvard-edited New England Journal of Medicine published an article by two Harvard professors on whether primary schools should reopen, without even mentioning Sweden. It was like ignoring the placebo control group when evaluating a new pharmaceutical drug. That’s not the path to truth.

That spring, I supported the Swedish approach in op-eds published in my native Sweden, but despite being a Harvard professor, I was unable to publish my thoughts in American media. My attempts to disseminate the Swedish school report on Twitter (now X) put me on the platform’s Trends Blacklist. In August 2020, my op-ed on school closures and Sweden was finally published by CNN—but not the one you’re thinking of. I wrote it in Spanish, and CNN–Español ran it. CNN–English was not interested.

I was not the only public health scientist speaking out against school closures and other unscientific countermeasures. Scott Atlas, an especially brave voice, used scientific articles and facts to challenge the public health advisors in the Trump White House, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci, National Institutes of Health director Francis Collins, and Covid coordinator Deborah Birx, but to little avail. When 98 of his Stanford faculty colleagues unjustly attacked Atlas in an open letter that did not provide a single example of where he was wrong, I wrote a response in the student-run Stanford Daily to defend him. I ended the letter by pointing out that:

Among experts on infectious disease outbreaks, many of us have long advocated for an age-targeted strategy, and I would be delighted to debate this with any of the 98 signatories. Supporters include Professor Sunetra Gupta at Oxford University, the world’s preeminent infectious disease epidemiologist. Assuming no bias against women scientists of color, I urge Stanford faculty and students to read her thoughts .

None of the 98 signatories accepted my offer to debate. Instead, someone at Stanford sent complaints to my superiors at Harvard, who were not thrilled with me.

I had no inclination to back down. Together with Gupta and Jay Bhattacharya at Stanford, I wrote the Great Barrington Declaration , arguing for age-based focused protection instead of universal lockdowns, with specific suggestions for how better to protect the elderly, while letting children and young adults live close to normal lives.

With the Great Barrington Declaration, the silencing was broken. While it is easy to dismiss individual scientists, it was impossible to ignore three senior infectious-disease epidemiologists from three leading universities. The declaration made clear that no scientific consensus existed for school closures and many other lockdown measures. In response, though, the attacks intensified—and even grew slanderous. Collins, a lab scientist with limited public-health experience who controls most of the nation’s medical research budget, called us “fringe epidemiologists” and asked his colleagues to orchestrate a “devastating published takedown.” Some at Harvard obliged.

A prominent Harvard epidemiologist publicly called the declaration “ an extreme fringe view ,” equating it with exorcism to expel demons. A member of Harvard’s Center for Health and Human Rights, who had argued for school closures, accused me of “trolling” and having “idiosyncratic politics,” falsely alleging that I was “ enticed . . . with Koch money ,” “ cultivated by right-wing think tanks ,” and “ won’t debate anyone .” (A concern for those less privileged does not automatically make you right-wing!) Others at Harvard worried about my “scientifically inaccurate” and “potentially dangerous position,” while “grappling with the protections offered by academic freedom.”

Though powerful scientists, politicians, and the media vigorously denounced it, the Great Barrington Declaration gathered almost a million signatures, including tens of thousands from scientists and health-care professionals. We were less alone than we had thought.

Even from Harvard, I received more positive than negative feedback. Among many others, support came from a former chair of the Department of Epidemiology—a former dean, a top surgeon, and an autism expert, who saw firsthand the devastating collateral damage that lockdowns inflicted on her patients. While some of the support I received was public, most was behind the scenes from faculty unwilling to speak publicly.

Two Harvard colleagues tried to arrange a debate between me and opposing Harvard faculty, but just as with Stanford, there were no takers. The invitation to debate remains open. The public should not trust scientists, even Harvard scientists, unwilling to debate their positions with fellow scientists.

My former employer, the Mass General Brigham hospital system, employs the majority of Harvard Medical School faculty. It is the single largest recipient of NIH funding—over $1 billion per year from U.S. taxpayers. As part of the offensive against the Great Barrington Declaration, one of Mass General’s board members, Rochelle Walensky, a fellow Harvard professor who had served on the advisory council to NIH director Collins, engaged me in a one-directional “debate.” After a Boston radio station interviewed me , Walensky came on as the official representative of Mass General Brigham to counter me, without giving me an opportunity to respond. A few months later, she became the new CDC director.

At this point, it was clear that I faced a choice between science or my academic career. I chose the former. What is science if we do not humbly pursue the truth?

In the 1980s, I worked for a human rights organization in Guatemala. We provided round-the-clock international physical accompaniment to poor campesinos, unionists, women’s groups, students, and religious organizations. Our mission was to protect those who spoke up against the killings and disappearances perpetrated by the right-wing military dictatorship, which shunned international scrutiny of its dirty work. Though the military threatened us, stabbed two of my colleagues, and threw a hand grenade into the house where we all lived and worked, we stayed to protect the brave Guatemalans.

I chose then to risk my life to help protect vulnerable people. It was a comparatively easy choice to risk my academic career to do the same during the pandemic. While the situation was less dramatic and terrifying than the one that I faced in Guatemala, many more lives were ultimately at stake.

While school closures and lockdowns were the big controversy of 2020, a new dispute emerged in 2021: the Covid vaccines. For more than two decades, I have helped the CDC and FDA develop their post-market vaccine safety systems. Vaccines are a vital medical invention, allowing people to obtain immunity without the risk that comes from getting sick. The smallpox vaccine alone has saved millions of lives. In 2020, the CDC asked me to serve on its Covid-19 Vaccine Safety Technical Work Group. My tenure didn’t last long—though not for the reason you may think.

The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for the Covid vaccines were not properly designed. While they demonstrated the vaccines’ short-term efficacy against symptomatic infection, they were not designed to evaluate hospitalization and death, which is what matters. In subsequent pooled RCT analyses by vaccine type, independent Danish scientists showed that the mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) did not reduce short-term, all-cause mortality, while the adenovirus-vector vaccines (Johnson & Johnson, Astra-Zeneca, Sputnik) did reduce mortality, by at least 30 percent.

I have spent decades studying drug and vaccine adverse reactions without taking any money from pharmaceutical companies. Every honest person knows that new drugs and vaccines come with potential risks that are unknown when approved. This was a risk worth taking for older people at high risk of Covid mortality—but not for children, who have a minuscule risk for Covid mortality, nor for those who already had infection-acquired immunity. To a question about this on Twitter in 2021, I responded:

Thinking that everyone must be vaccinated is as scientifically flawed as thinking that nobody should. COVID vaccines are important for older high-risk people and their care-takers. Those with prior natural infection do not need it. Nor children.

At the behest of the U.S. government , Twitter censored my tweet for contravening CDC policy. Having also been censored by LinkedIn, Facebook, and YouTube, I could not freely communicate as a scientist. Who decided that American free-speech rights did not apply to honest scientific comments at odds with those of the CDC director?

I was tempted just to shut up, but a Harvard colleague convinced me otherwise. Her family had been active against Communism in Eastern Europe, and she reminded me that we needed to use whatever openings we could find—while self-censoring, when necessary, to avoid getting suspended or fired.

On that score, however, I failed. A month after my tweet, I was fired from the CDC Covid Vaccine Safety Working Group—not because I was critical of vaccines but because I contradicted CDC policy. In April 2021, the CDC paused the J&J vaccine after reports of blood clots in a few women under 50. No cases were reported among older people, who benefit the most from the vaccine. Since there was a general vaccine shortage at that time, I argued in an op-ed that the J&J vaccine should not be paused for older Americans. This is what got me in trouble. I am probably the only person ever fired by the CDC for being too pro-vaccine. While the CDC lifted the pause four days later , the damage was done. Some older Americans undoubtedly died because of this vaccine “pause.”

Bodily autonomy is not the only argument against Covid vaccine mandates. They are also unscientific and unethical.

With a genetic condition called alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, which leaves me with a weakened immune system, I had more reason to be personally concerned about Covid than most Harvard professors. I expected that Covid would hit me hard, and that’s precisely what happened in early 2021, when the devoted staff at Manchester Hospital in Connecticut saved my life. But it would have been wrong for me to let my personal vulnerability to infections influence my opinions and recommendations as a public-health scientist, which must focus on everyone’s health.

The beauty of our immune system is that those who recover from an infection are protected if and when they are re-exposed. This has been known since the Athenian Plague of 430 BC—but it is no longer known at Harvard. Three prominent Harvard faculty coauthored the now infamous “consensus” memorandum in The Lancet , questioning the existence of Covid-acquired immunity. By continuing to mandate the vaccine for students with a prior Covid infection, Harvard is de facto denying 2,500 years of science.

Since mid-2021, we have known, as one would expect, that Covid-acquired immunity is superior to vaccine-acquired immunity. Based on that, I argued that hospitals should hire, not fire, nurses and other hospital staff with Covid-acquired immunity, since they have stronger immunity than the vaccinated.

Vaccine mandates are unethical. The RCTs mainly enrolled young and middle-aged adults, but observational studies showed that Covid vaccines prevented Covid hospitalizations and deaths for older people. Amid a worldwide vaccine shortage, it was unethical to force the vaccine on low-risk students or those like me who were already immune from having had Covid, while my 87-year-old neighbor and other high-risk older people around the world could not get the shot. Any pro-vaccine person should, for this reason alone, have opposed the Covid vaccine mandates.

For scientific, ethical, public health, and medical reasons, I objected both publicly and privately to the Covid vaccine mandates. I already had superior infection-acquired immunity; and it was risky to vaccinate me without proper efficacy and safety studies on patients with my type of immune deficiency. This stance got me fired by Mass General Brigham—and consequently fired from my Harvard faculty position.

While several vaccine exemptions were given by the hospital, my medical exemption request was denied. I was less surprised that my religious exemption request was denied: “Having had COVID disease, I have stronger longer lasting immunity than those vaccinated ( Gazit et al ). Lacking scientific rationale, vaccine mandates are religious dogma, and I request a religious exemption from COVID vaccination.”

If Harvard and its hospitals want to be credible scientific institutions, they should rehire those of us they fired. And Harvard would be wise to eliminate its Covid vaccine mandates for students, as most other universities have already done.

Most Harvard faculty diligently pursue truth in a wide variety of fields, but Veritas has not been the guiding principle of Harvard leaders. Nor have academic freedom, intellectual curiosity, independence from external forces, or concern for ordinary people guided their decisions.

Harvard and the wider scientific community have much work to do to deserve and regain public trust. The first steps are the restoration of academic freedom and the cancelling of cancel culture. When scientists have different takes on topics of public importance, universities should organize open and civilized debates to pursue the truth. Harvard could have done that—and it still can, if it chooses.

Almost everyone now realizes that school closures and other lockdowns, were a colossal mistake. Francis Collins has acknowledged his error of singularly focusing on Covid without considering collateral damage to education and non-Covid health outcomes. That’s the honest thing to do, and I hope this honesty will reach Harvard. The public deserves it, and academia needs it to restore its credibility.

Science cannot survive in a society that does not value truth and strive to discover it. The scientific community will gradually lose public support and slowly disintegrate in such a culture. The pursuit of truth requires academic freedom with open, passionate, and civilized scientific discourse, with zero tolerance for slander, bullying, or cancellation. My hope is that someday, Harvard will find its way back to academic freedom and independence.

Martin Kulldorff is a former professor of medicine at Harvard University and Mass General Brigham. He is a founding fellow of the Academy for Science and Freedom .

Photo by Erica Denhoff/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Further Reading

Copyright © 2024 Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Eye on the News

- From the Magazine

- Books and Culture

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

EIN #13-2912529

COMMENTS