- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Comparative Analysis

What It Is and Why It's Useful

Comparative analysis asks writers to make an argument about the relationship between two or more texts. Beyond that, there's a lot of variation, but three overarching kinds of comparative analysis stand out:

- Coordinate (A ↔ B): In this kind of analysis, two (or more) texts are being read against each other in terms of a shared element, e.g., a memoir and a novel, both by Jesmyn Ward; two sets of data for the same experiment; a few op-ed responses to the same event; two YA books written in Chicago in the 2000s; a film adaption of a play; etc.

- Subordinate (A → B) or (B → A ): Using a theoretical text (as a "lens") to explain a case study or work of art (e.g., how Anthony Jack's The Privileged Poor can help explain divergent experiences among students at elite four-year private colleges who are coming from similar socio-economic backgrounds) or using a work of art or case study (i.e., as a "test" of) a theory's usefulness or limitations (e.g., using coverage of recent incidents of gun violence or legislation un the U.S. to confirm or question the currency of Carol Anderson's The Second ).

- Hybrid [A → (B ↔ C)] or [(B ↔ C) → A] , i.e., using coordinate and subordinate analysis together. For example, using Jack to compare or contrast the experiences of students at elite four-year institutions with students at state universities and/or community colleges; or looking at gun culture in other countries and/or other timeframes to contextualize or generalize Anderson's main points about the role of the Second Amendment in U.S. history.

"In the wild," these three kinds of comparative analysis represent increasingly complex—and scholarly—modes of comparison. Students can of course compare two poems in terms of imagery or two data sets in terms of methods, but in each case the analysis will eventually be richer if the students have had a chance to encounter other people's ideas about how imagery or methods work. At that point, we're getting into a hybrid kind of reading (or even into research essays), especially if we start introducing different approaches to imagery or methods that are themselves being compared along with a couple (or few) poems or data sets.

Why It's Useful

In the context of a particular course, each kind of comparative analysis has its place and can be a useful step up from single-source analysis. Intellectually, comparative analysis helps overcome the "n of 1" problem that can face single-source analysis. That is, a writer drawing broad conclusions about the influence of the Iranian New Wave based on one film is relying entirely—and almost certainly too much—on that film to support those findings. In the context of even just one more film, though, the analysis is suddenly more likely to arrive at one of the best features of any comparative approach: both films will be more richly experienced than they would have been in isolation, and the themes or questions in terms of which they're being explored (here the general question of the influence of the Iranian New Wave) will arrive at conclusions that are less at-risk of oversimplification.

For scholars working in comparative fields or through comparative approaches, these features of comparative analysis animate their work. To borrow from a stock example in Western epistemology, our concept of "green" isn't based on a single encounter with something we intuit or are told is "green." Not at all. Our concept of "green" is derived from a complex set of experiences of what others say is green or what's labeled green or what seems to be something that's neither blue nor yellow but kind of both, etc. Comparative analysis essays offer us the chance to engage with that process—even if only enough to help us see where a more in-depth exploration with a higher and/or more diverse "n" might lead—and in that sense, from the standpoint of the subject matter students are exploring through writing as well the complexity of the genre of writing they're using to explore it—comparative analysis forms a bridge of sorts between single-source analysis and research essays.

Typical learning objectives for single-sources essays: formulate analytical questions and an arguable thesis, establish stakes of an argument, summarize sources accurately, choose evidence effectively, analyze evidence effectively, define key terms, organize argument logically, acknowledge and respond to counterargument, cite sources properly, and present ideas in clear prose.

Common types of comparative analysis essays and related types: two works in the same genre, two works from the same period (but in different places or in different cultures), a work adapted into a different genre or medium, two theories treating the same topic; a theory and a case study or other object, etc.

How to Teach It: Framing + Practice

Framing multi-source writing assignments (comparative analysis, research essays, multi-modal projects) is likely to overlap a great deal with "Why It's Useful" (see above), because the range of reasons why we might use these kinds of writing in academic or non-academic settings is itself the reason why they so often appear later in courses. In many courses, they're the best vehicles for exploring the complex questions that arise once we've been introduced to the course's main themes, core content, leading protagonists, and central debates.

For comparative analysis in particular, it's helpful to frame assignment's process and how it will help students successfully navigate the challenges and pitfalls presented by the genre. Ideally, this will mean students have time to identify what each text seems to be doing, take note of apparent points of connection between different texts, and start to imagine how those points of connection (or the absence thereof)

- complicates or upends their own expectations or assumptions about the texts

- complicates or refutes the expectations or assumptions about the texts presented by a scholar

- confirms and/or nuances expectations and assumptions they themselves hold or scholars have presented

- presents entirely unforeseen ways of understanding the texts

—and all with implications for the texts themselves or for the axes along which the comparative analysis took place. If students know that this is where their ideas will be heading, they'll be ready to develop those ideas and engage with the challenges that comparative analysis presents in terms of structure (See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more on these elements of framing).

Like single-source analyses, comparative essays have several moving parts, and giving students practice here means adapting the sample sequence laid out at the " Formative Writing Assignments " page. Three areas that have already been mentioned above are worth noting:

- Gathering evidence : Depending on what your assignment is asking students to compare (or in terms of what), students will benefit greatly from structured opportunities to create inventories or data sets of the motifs, examples, trajectories, etc., shared (or not shared) by the texts they'll be comparing. See the sample exercises below for a basic example of what this might look like.

- Why it Matters: Moving beyond "x is like y but also different" or even "x is more like y than we might think at first" is what moves an essay from being "compare/contrast" to being a comparative analysis . It's also a move that can be hard to make and that will often evolve over the course of an assignment. A great way to get feedback from students about where they're at on this front? Ask them to start considering early on why their argument "matters" to different kinds of imagined audiences (while they're just gathering evidence) and again as they develop their thesis and again as they're drafting their essays. ( Cover letters , for example, are a great place to ask writers to imagine how a reader might be affected by reading an their argument.)

- Structure: Having two texts on stage at the same time can suddenly feel a lot more complicated for any writer who's used to having just one at a time. Giving students a sense of what the most common patterns (AAA / BBB, ABABAB, etc.) are likely to be can help them imagine, even if provisionally, how their argument might unfold over a series of pages. See "Tips" and "Common Pitfalls" below for more information on this front.

Sample Exercises and Links to Other Resources

- Common Pitfalls

- Advice on Timing

- Try to keep students from thinking of a proposed thesis as a commitment. Instead, help them see it as more of a hypothesis that has emerged out of readings and discussion and analytical questions and that they'll now test through an experiment, namely, writing their essay. When students see writing as part of the process of inquiry—rather than just the result—and when that process is committed to acknowledging and adapting itself to evidence, it makes writing assignments more scientific, more ethical, and more authentic.

- Have students create an inventory of touch points between the two texts early in the process.

- Ask students to make the case—early on and at points throughout the process—for the significance of the claim they're making about the relationship between the texts they're comparing.

- For coordinate kinds of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is tied to thesis and evidence. Basically, it's a thesis that tells the reader that there are "similarities and differences" between two texts, without telling the reader why it matters that these two texts have or don't have these particular features in common. This kind of thesis is stuck at the level of description or positivism, and it's not uncommon when a writer is grappling with the complexity that can in fact accompany the "taking inventory" stage of comparative analysis. The solution is to make the "taking inventory" stage part of the process of the assignment. When this stage comes before students have formulated a thesis, that formulation is then able to emerge out of a comparative data set, rather than the data set emerging in terms of their thesis (which can lead to confirmation bias, or frequency illusion, or—just for the sake of streamlining the process of gathering evidence—cherry picking).

- For subordinate kinds of comparative analysis , a common pitfall is tied to how much weight is given to each source. Having students apply a theory (in a "lens" essay) or weigh the pros and cons of a theory against case studies (in a "test a theory") essay can be a great way to help them explore the assumptions, implications, and real-world usefulness of theoretical approaches. The pitfall of these approaches is that they can quickly lead to the same biases we saw here above. Making sure that students know they should engage with counterevidence and counterargument, and that "lens" / "test a theory" approaches often balance each other out in any real-world application of theory is a good way to get out in front of this pitfall.

- For any kind of comparative analysis, a common pitfall is structure. Every comparative analysis asks writers to move back and forth between texts, and that can pose a number of challenges, including: what pattern the back and forth should follow and how to use transitions and other signposting to make sure readers can follow the overarching argument as the back and forth is taking place. Here's some advice from an experienced writing instructor to students about how to think about these considerations:

a quick note on STRUCTURE

Most of us have encountered the question of whether to adopt what we might term the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure or the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure. Do we make all of our points about text A before moving on to text B? Or do we go back and forth between A and B as the essay proceeds? As always, the answers to our questions about structure depend on our goals in the essay as a whole. In a “similarities in spite of differences” essay, for instance, readers will need to encounter the differences between A and B before we offer them the similarities (A d →B d →A s →B s ). If, rather than subordinating differences to similarities you are subordinating text A to text B (using A as a point of comparison that reveals B’s originality, say), you may be well served by the “A→A→A→B→B→B” structure.

Ultimately, you need to ask yourself how many “A→B” moves you have in you. Is each one identical? If so, you may wish to make the transition from A to B only once (“A→A→A→B→B→B”), because if each “A→B” move is identical, the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure will appear to involve nothing more than directionless oscillation and repetition. If each is increasingly complex, however—if each AB pair yields a new and progressively more complex idea about your subject—you may be well served by the “A→B→A→B→A→B” structure, because in this case it will be visible to readers as a progressively developing argument.

As we discussed in "Advice on Timing" at the page on single-source analysis, that timeline itself roughly follows the "Sample Sequence of Formative Assignments for a 'Typical' Essay" outlined under " Formative Writing Assignments, " and it spans about 5–6 steps or 2–4 weeks.

Comparative analysis assignments have a lot of the same DNA as single-source essays, but they potentially bring more reading into play and ask students to engage in more complicated acts of analysis and synthesis during the drafting stages. With that in mind, closer to 4 weeks is probably a good baseline for many single-source analysis assignments. For sections that meet once per week, the timeline will either probably need to expand—ideally—a little past the 4-week side of things, or some of the steps will need to be combined or done asynchronously.

What It Can Build Up To

Comparative analyses can build up to other kinds of writing in a number of ways. For example:

- They can build toward other kinds of comparative analysis, e.g., student can be asked to choose an additional source to complicate their conclusions from a previous analysis, or they can be asked to revisit an analysis using a different axis of comparison, such as race instead of class. (These approaches are akin to moving from a coordinate or subordinate analysis to more of a hybrid approach.)

- They can scaffold up to research essays, which in many instances are an extension of a "hybrid comparative analysis."

- Like single-source analysis, in a course where students will take a "deep dive" into a source or topic for their capstone, they can allow students to "try on" a theoretical approach or genre or time period to see if it's indeed something they want to research more fully.

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Unpacking the Elements of Writing Prompts

- Formative Writing Assignments

- Single-Source Analysis

- Research Essays

- Multi-Modal or Creative Projects

- Giving Feedback to Students

Assignment Decoder

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Architecture

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in History

- History of Education

- Regional and National History

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Feminist Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Browse content in Religion

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Technology and Society

- Browse content in Law

- Comparative Law

- Criminal Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Browse content in International Law

- Public International Law

- Legal System and Practice

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Environmental Geography

- Urban Geography

- Environmental Science

- Browse content in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Human Resource Management

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- Knowledge Management

- Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Browse content in Economics

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- History of Economic Thought

- Public Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Politics

- Asian Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Public Policy

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- Asian Studies

- Browse content in Social Work

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

One The competition state thesis in a comparative perspective: the evolution of a thesis

- Published: June 2017

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter discusses the competition state thesis. Globalisation, the decline of the Fordist model of production, and the rise of the global knowledge economy have all played their role in producing a more competitive environment in which welfare states operate. What exactly is the competition state? Where the welfare state seeks to use the tools of the economy to further the public interest and promote social justice, the competition state seeks only economic success, with welfare provisions not only secondary, but offered only when they support the primary goal of economic success. The chapter then summarises and subsequently extends previous empirical work undertaken using the competition state framework in order to assess the extent to which the core thesis is still relevant today.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to content

Comparing the Literatures: Contemporary Perspectives — Introduction

Comparative literature — besides being the name of an academic discipline, field of research, and study program in institutions of higher education — stands for a great tradition of the humanities. Since its beginning around 1800, it serves as a ground for significant enterprises of literary studies in academic frameworks in Europe, North and South America, the Near and the Far East. This field involves classical philology and esthetics, critical theory, semiotics and narratology, translation studies, post-colonial theory, exile and migration studies, gender and queer theories, the visual arts, and eco-poetics, to name a few. It also reflects core questions regarding the experience (and the representation) of the world. Comparative literature serves also as a cultural paradigm, associated with multilingualism and cultural diversity, yet not free from blind spots — Western universalism, Eurocentrism, orientalist views, heteronormative assumptions. Its “death” as a discipline was announced a while ago — its “rebirth,” too. The very idea of comparison — the association of different case studies from the literatures of the world — continues, however, to challenge our research and teaching. Following David Damrosch’s book, “Comparing the Literatures: Literary Studies in a Global Age,” we (Amir Eshel, Galili Shahar, and Vered Shemtov) invited colleagues and graduate students from our programs of comparative literature at Stanford University and at Tel Aviv University to reflect on the core issues of our field: its origins and histories, current questions, multi-perspectives and methods, and its contemporary implications in our institutions in North America and in Israel/Palestine. The essays thus reflect not just “case studies” in comparative literature but also the effort of saving the local — in a global age.

This effort, too, was associated with Damrosch’s book. Reflecting, however, on its origins, Damrosch recounts a dazzling trick. In one of his previous books, Meetings of the Mind , Damrosch invented three interlocutors: the Israeli semiotician Dov Midrash, the multilingual aesthete Vic d’Ohr Addams, and the feminist film theorist Marsha Doddvic. All three are anagrams of Damrosch’s own name. Each one presents opposing positions he considers and partly accepts. All of them mock “the blandly liberal Damrosch, who thinks he can persuade all the warring parties to get along together.”

Blending the kind of irony we encounter at the turn of the nineteenth century in the work of the German romantics with his panoramic familiarity with the history and practice of comparative literature, Damrosch urges us to do two things at the same time: to acknowledge and respect the infinite diversity of literary production across cultures and locations while we simultaneously strive to discover similarities and moments of formal and thematic conversion. The spirit of Damrosch’s move to both refract any stable notion of comparative literature and to work toward productive engagement and exchange accompanies all contributions to this collection. Any attempt to suggest that all contributors share a single vision of what comparative literature is or should be is bound to dissolve, just as Damrosch discovered, in his own name, his own position, and at least three others captured in the names of Midrash, Addams, and Doddvic. The essays gathered in this special double issue can be addressed as another way of revealing and naming the challenges, contradictions, critiques, and ironies of comparative literature as represented in his book.

Turning to one of the first moments in the history of comparative literature, Nir Evron’s “Herder on Shakespeare, Nominalism, and Obsolescence” revisits Johann Gottfried Herder’s 1773 essay on Shakespeare. Herder’s critical essay is essential for our notion of comparative literature as a discipline, Evron argues, since it both recognizes the consequences of adopting a “culturalist and historicist self-image that it promotes” and models “the nominalist and culturalist outlook” which has been crucial in its history. Herder’s meditation on cultural finitude in Shakespeare, Evron argues, originates in his “insistence that human beings are social and historical creatures” — an insight with far-reaching implications for comparative literature and all other humanistic fields of study.

Casting his gaze at an earlier point of departure for a comparative perspective, Iyad Malouf, in “Medieval Othering: Western Monsters and Eastern Maskhs ,” offers a manifold reading of “medieval Othering” while focusing on the figures of monster and maskh . While monsters had an integral role in defining the non-Christian Other in the West, maskhs , Malouf argues, played a similar role in what came to be known as “the East.” Examining the meaning, function, and interaction of monsters and maskhs in the Middle Ages, the article shows, may contribute to a more nuanced understanding of “medieval Othering,” a practice and a prejudice still operative today in cultural and political discourse across the globe.

Practices of distancing and exclusion are also at the center of Uri S. Cohen and Manar H. Makhoul’s “Political Animals in Palestine-Israel.” Employing the conceptual shift at work in ecocriticism and animal studies regarding “ecology” as a trope of “coexistence,” they examine narratives which touch on the milestone year 1948 in the history of the modern Middle East. The animals of Palestine as they emerge in these narratives, they argue, offer us a glimpse into literature’s capacity to examine the idea of equality: “the equal value of all life, human and animal.” Animals emerge here as a powerful trope in the striving to lend an ear to untold or ignored aspects of 1948 as a historical trauma, to get closer to “the secrets of Palestine and its destruction.” Comparing literary works as they give voice to the language of animals may transcend our pure emotional reaction to the pain of the single sentient creature and open possibilities of genuine listening among the two parties of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The question of nationalism and national conflict is similarly driving Victoria Zurita’s “Remedios in Valinor: Magical Realism, Transnationalisms, and the Historicity of Literary Value.” Zurita confronts here two forms of “transnationalism” — regionalism and cosmopolitanism — as they appear in Damrosch’s Comparing the Literatures . Assessing Damrosch’s arguments on the comparability of magical realism and examining their implications for his book’s larger aims, Zurita probes the assumption of some of the major voices in the “transnational turn,” especially in the field of global modernisms, in their attempt to transcend the specificities of the literary works in question.

Sarah Stoll’s “Kafka’s ‘Gehilfen’ — The Castle in between Nature Theater and Yiddish Theater” turns to one of the major scenes of European modernism, Prague, and to one of this movement’s canonic representatives, Franz Kafka. Focusing on Kafka’s The Castle , Stoll suggests that we read the posthumously published novel as “a theater play in which the protagonist is trying to achieve a role that was never made for him.” K.’s attempt to create his own reality is in Stoll’s reading “the allegory of a minor, that means a revolutionary, writing.” Relating to both world theater and to the Yiddish theater of its time, The Castle reveals itself here as a site of personal and communal struggle with cultural prejudice. Kafka’s diary entries on the Yiddish theater lend Stoll’s comparative interpretation further weight. She displays how prose, drama, and personal narrative grapple with and test the national creed.

Whereas linguistic marginalization characterizes the view of Yiddish in early twentieth century Prague, Michèle Bokobza Kahan’s “The Female Novelists of the Emigration of the French Revolution: Presentation of a Literary Scene” draws our attention to gender as a site of conflict and literary production. Presenting novels of emigration during the French Revolution written by such women as Stéphanie de Genlis, Adélaïde de Souza, Isabelle de Charrière, and Claire de Duras, Kahan focuses on the notion of hospitality. Highlighting the link between emigration and hospitality, she suggests that the writers in question mobilized their literature to pursue professional recognition — to validate and bring about a recognition of their writing choices and practices. Employing Judith Schlanger’s term “literary scene,” Kahan presents the writers and works at the center of her article as helping us to negotiate an interpretative perspective which exceeds the binary of the “local” and the “global.”

Comparative literature’s capacity to examine narrative across geographic location, genre, and even discipline guides Haiyan Lee in “Apples and Oranges? An Idiosyncratic Comparison of Literature and Anthropology.” From her standpoint as a specialist in Chinese literature, she considers the kind of knowledge literary studies produces. Moving between the personal and the theoretical, she suggests that anthropology can provide useful tools in making sense of politically and culturally distant texts in the age of world literature. She illustrates this provocative point by turning to flat characters in traditional Chinese fiction in light of new research in the anthropology of mind. Literary studies, she urges us to consider, should move toward the “new humanities” in order to become relevant to broader constituencies.

The biases of Western thought regarding genre take center stage in Teddy Fassberg’s “Languages of Gods and the Structures of Human Literatures: An Essay in Comparative Poetics.” Fassberg challenges the conventional, reductive notion of literature as comprised of merely two complementary, comprehensive categories: poetry and prose. Probing the validity of this restrictive view as it emerges as early as ancient Greek and Roman thought, Fassberg then demonstrates that the “poetry” versus “prose” dichotomy is nowhere to be found in the neighboring ancient literary cultures of biblical Hebrew and early Islam. Fassberg then proceeds to argue that the manufactured difference between the two genres correlates to Greek and Roman concepts of divinity, specifically the language of their gods. Fassberg furthermore ties his theoretical move to Erich Auerbach’s argument in Mimesis regarding the separation and mixture of styles in antiquity.

In “Rethinking the Dictionary: Holocaust Dictionaries in Global Perspective,” Hannah Pollin-Galay and Betzalel Strauss challenge another restrictive view: the relegation of the dictionary outside of the literary field. Questioning this practice, they urge us in their article to discover in the dictionary a rich locus of literature and of comparative cultural interpretation.

Centering on Holocaust-Yiddish dictionaries, they reveal — in the succinctness of the dictionary entry and in the capaciousness of the dictionary as a cultural endeavor — “ethical, emotional, and even spiritual potency.” Exemplifying the methods of comparative literature, they include in their discussion a broad array of sources, such as the Oxford English Dictionary , an interwar lexicon of Yiddish jargon, the Chinese Erya, and the Hebrew-Arabic Ha-Egron . Their examination leads then to the discovery of a productive tension within the genre: while the dictionary promises to organize and categorize language, it often reveals that which is unknowable in speech and in experience.

The notion of experience also guides Tal Yehezkely in “Airing Literature: Reading with the Sense of Smell.” While comparative literature thus far centers on language in its various iterations, the article urges us to explores forms of reading inspired by “both the sense of smell, and the phenomenon of smell.” The article begins by laying out its theoretical foundation. It formulates a comparative model deriving from the conceptual history of smell and from its attributes as a physical phenomenon. Yehezkely then proceeds to examine the peculiar materiality of smell as part of an atmosphere and the possible implications it might have when we examine what links or separates “literature” and “life.”

Literature’s ability to touch on “life” as a tangible, corporal category guides J. Rafael Balling in “Between Times: The Case of Yiddish Transness.” Balling here examines literature as it challenges normative concepts of gender. His article traces the literary undermining of any stable sense of time and place. Turning to Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short story, “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy” [“Yentl der Yeshive Bokher”], Balling uncovers the narrative’s capacity to suspend medical categorizations of transness. Bashevis Singer’s work is exemplary in this regard, Balling shows, since it mobilizes such rich and diverse sources as Yiddish demons, rabbinic writings, and early-twentieth century sexological accounts of gender variance. “Yentl” emerges in Balling’s reading as a powerful opportunity to overcome prejudice in regard to gender variance. The work invites us to imagine the possibility of accepting the productive intersections of temporal, linguistic, and geographical migrations.

The capacity of literature to imagine realities which far exceed normative modes of individual and communal life informs Adi Molad’s “The Circus Comes to Town: Reading Gershon Shofman’s Hebrew Literature in the Ring.” Through the lens of Gershon Shofman’s work, Molad examines the circus as a liminal space in which corporal, subjective, and communal norms solidify and refract. Since the trope of the traveling circus as a lush amalgamation of the eclectic and the unique is a metaphor for transcending domesticity and nationality, it lends itself to examine this work of Hebrew literature as pursuing “a supranational theme that expresses the worldly in literature.” Focusing on three circus stories by Shofman, Molad shows that physical power does not necessarily translate into national domination or political subjugation. The circus becomes in this article a powerful lens through which we can see how the literary imagination and our attempts to interpret the literary far exceed any limitation of a single national language or a single national creed.

This double issue ends with an essay by Dharshani Lakmali Jayasinghe entitled “When Translating Ultra Minor Literatures is Not Enough to Counter Epistemicide.” Lakmali’s annotated translation of a selection of quatrains by Thotagamuwe Sri Rahula Therato was published previously in Dibur’s Curated magazine. The essay explores “some of the challenges that scholars working on what David Damrosch calls ‘ultra Minor’ literatures from the Global South must contend with, particularly the politics of organizing and compiling bibliographies.”

Stanford strives to post only content for which we have licensed permission or that is otherwise permitted by copyright law. If you have a concern that your copyrighted material is posted here without your permission, please contact us and we will work with you to resolve your concern.

© 2019 Arcade bloggers retain copyright of their own posts, which are made available to the public under a Creative Commons license, unless stated otherwise. If any Arcade blogger elects a different license, the blogger's license takes precedence.

Arcade: A Digital Salon by http://arcade.stanford.edu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License . Based on a work at arcade.stanford.edu .

- Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East

Introduction: Comparative Literature

- Ipshita Chanda , Bilal Hashmi

- Duke University Press

- Volume 32, Number 3, 2012

- pp. 465-469

- View Citation

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.1: Introduction to Comparison and Contrast Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 174873

The key to a good compare-and-contrast essay is to choose two or more subjects that connect in a meaningful way. Comparison and contrast is simply telling how two things are alike or different. The compare-and-contrast essay starts with a thesis that clearly states the two subjects that are to be compared, contrasted, or both. The thesis should focus on comparing, contrasting, or both.

Key Elements of the Compare and Contrast:

- A compare-and-contrast essay analyzes two subjects by either comparing them, contrasting them, or both.

- The purpose of writing a comparison or contrast essay is not to state the obvious but rather to illuminate subtle differences or unexpected similarities between two subjects.

- The thesis should clearly state the subjects that are to be compared, contrasted, or both, and it should state what is to be learned from doing so.

- Organize by the subjects themselves, one then the other.

- Organize by individual points, in which you discuss each subject in relation to each point.

- Use phrases of comparison or phrases of contrast to signal to readers how exactly the two subjects are being analyzed.

Objectives: By the end of this unit, you will be able to

- Identify compare & contrast relationships in model essays

- Construct clearly formulated thesis statements that show compare & contrast relationships

- Use pre-writing techniques to brainstorm and organize ideas showing a comparison and/or contrast

- Construct an outline for a five-paragraph compare & contrast essay

- Write a five-paragraph compare & contrast essay

- Use a variety of vocabulary and language structures that express compare & contrast essay relationships

Example Thesis: Organic vegetables may cost more than those that are conventionally grown, but when put to the test, they are definitely worth every extra penny.

Sample Paragraph:

Organic grown tomatoes purchased at the farmers’ market are very different from tomatoes that are grown conventionally. To begin with, although tomatoes from both sources will mostly be red, the tomatoes at the farmers’ market are a brighter red than those at a grocery store. That doesn’t mean they are shinier—in fact, grocery store tomatoes are often shinier since they have been waxed. You are likely to see great size variation in tomatoes at the farmers’ market, with tomatoes ranging from only a couple of inches across to eight inches across. By contrast, the tomatoes in a grocery store will be fairly uniform in size. All the visual differences are interesting, but the most important difference is the taste. The farmers’ market tomatoes will be bursting with flavor from ripening on the vine in their own time. However, the grocery store tomatoes are often close to being flavorless. In conclusion, the differences in organic and conventionally grown tomatoes are obvious in color, size and taste.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

The Comparative Perspective on Literature

Approaches to theory and practice.

- Clayton Koelb

- Edited by: Susan Noakes

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Cornell University Press

- Copyright year: 1988

- Audience: General/trade;

- Main content: 392

- Keywords: Literary Studies

- Published: June 30, 2019

- ISBN: 9781501743986

Advertisement

Comparative Policy Analysis and the Science of Conceptual Systems: A Candidate Pathway to a Common Variable

- Published: 20 March 2021

- Volume 27 , pages 287–304, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Guswin de Wee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1249-1121 1

8592 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

In comparative policy analysis (CPA), a generally accepted historic problem that transcends time is that of identifying common variables. Coupled with this problem is the unanswered challenge of collaboration and interdisciplinary research. Additionally, there is the problem of the rare use of text-as-data in CPA and the fact it is rarely applied, despite the potential demonstrated in other subfields. CPA is multi-disciplinary in nature, and this article explores and proposes a common variable candidate that is found in almost (if not) all policies, using the science of conceptual systems (SOCS) as a pathway to investigate the structure found in policy as a lynchpin in CPA. Furthermore, the article proposes a new text-as-data approach that is less expensive, which could lead to a more accessible method for collaborative and interdisciplinary policy development. We find that the SOCS is uniquely positioned to serve in an alliance fashion in the larger qualitative comparative analysis that supports CPA. Because policies around the world are failing to reach their goals successfully, this article is expected to open a new path of inquiry in CPA, which could be used to support interdisciplinary research for knowledge of and knowledge in policy analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

Drishti Yadav

The potential of working hypotheses for deductive exploratory research

Mattia Casula, Nandhini Rangarajan & Patricia Shields

What Is Globalisation?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the 1990s, comparative policy analysis (CPA) and comparative analytical studies, as a modern research tradition, joined comparative politics and comparative public administration, using the comparative method (Geva-May et al. 2020 : 368). Peters and Fontaine ( 2020 : 29) contend that the comparative method, as outlined by Lijphart, provides various opportunities for scholars of public policy to enhance their collective understanding of policy and policy processes. Peters et al. ( 2018 : 137) argue that CPA is in fact precisely designed to explain policy outcomes.

Cairney and Heikkila ( 2014 : 383) suggest that, by building on established literatures, new lenses on public policy seek to improve upon rather than compete with or replace existing perspectives. Thus, the posture taken in this article is that there are challenges in the field as well as opportunities, and this article suggests an opportunity to advance comparative public policy (Wong 2018 : 963).

Research seems to suggest that a common issue in comparative research is the great difficulties in comparing policies across a variety of situations/contexts, which is referred to as the problems of identifying common variables (Wong 2013 , 2016 ; Haque 1996 ; Welch and Wong 1998 ). In identifying future challenges and opportunities of the development of comparative public policy, Wong ( 2018 ) recognises the efforts made by scholars calling for collaboration and interdisciplinary research in comparative public policy, which is a problem that has for decades not been fully addressed.

A second issue in comparative public policy, and in particular CPA, is the fact that text-as-data methods have been rarely applied widely, despite their potential, which has been demonstrated in other subfields (Guy Peters and Fontaine 2020 : 203). Additionally, according to Guy Peters and Fontaine, “[t]hey have not created new text-as-data approaches as such.”

Peters ( 2020 : 21) argues that there is a clearly a need to utilise other methods and techniques to make comparisons. According to Peters and Fontaine ( 2020 : 14), CPA is in itself multi-disciplinary and as such more akin to multi-methods than any social sciences area. As a candidate to remedy this gap in literature, this article suggests the science of conceptual systems (SOCS) and in particular the use of integrative propositional analysis (IPA) methodology to examine the structure/structural logic of policy models as a way to provide a ‘common variable’ in CPA.

The SOCS is aimed at the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of conceptual systems using rigorous methodologies (Wallis 2016 ). Conceptual systems are defined as any collection of interrelated concepts found in theories, models, policy models, axioms, laws, strategic plans, and so on, which have a set of interrelated propositions. Generally, all conceptual systems from social sciences to hard/natural sciences have one aspect in common: they have some level of structure, which makes them amenable to an IPA-based analysis or evaluation. We will delve into the IPA in detail below.

Part of the motivation for this study is the critique and necessity for the systems-based approach of the SOCS. This is the problem of linear and simple policymaking (Sabatier 1999 ), which causes a mismatch between how real-world systems work and how we think of them (Cabrera and Colosi 2008 ). The simplistic models used to make decisions in complex systems lead to “worse outcomes than the previous status quo” (Beaulieu-B and Dufort 2017 : 1) and shortsighted practices (Sterman 2012 : 24). As such, implicitly the article also uses the SOCS and IPA as a vehicle to carry out the impact of systems thinking and its benefits in policy analysis.

The contribution of this article is twofold. Firstly, it explores how the structure that is found in each policy model or conceptual system can serve as a common variable when comparing policy. Secondly, the article provides a text-as-data approach with rigour and greater accessibility, which can be easily acquired and applied by policy makers, practitioners, and scholars. The article will specifically illustrate this by explaining how policy as a unit of analysis can be used to integrate theory, policy and research based on a ‘common language’ of structure , which will potentially allow for comparative analysis across systems.

To achieve this, the article is structured in three sections. Firstly, there is a review of comparative public policy and comparative analysis. Secondly, the article provides a background of the SOCS. Thirdly, the article illustrates how and why policies (policy models) are amenable to evaluation based on their structure, which will be shown to generate novel insights into the ability of IPA to improve CPA across different systems.

2 Comparative Policy Analysis

Lasswell ( 1971 ) made a distinction between knowledge of and knowledge in the policy process. However, both are very important for the purpose of this article. With regard to knowledge in the policy process, Radin and Weimar ( 2018 : 8) state that this perspective looks at “how can analysis improve the content of public policy?” This was premised on how the political process affects policy content application and so on. This current article looks at the structure of policy implementation, and in turn examines how the data that underlie the structure of a policy influence the structure of the policy.

Policy analysis is defined as the use of reason and evidence to choose the best policy among a number of alternatives (MacRae and Wilde 1979 : 14). Dror ( 1983 : 79) defines policy analysis as a “profession-craft clustering on providing systematic, rational, and science-based help with decision-making”. Brans et al. ( 2017 ) argue that what is central to policy analysis has always been the principle that decision-making should be systematic, evidence-based, verifiable and evaluative (transparent and accountable). Geva-May et al. ( 2020 ) maintain that evidence-based policymaking also implies, by definition, the search for evidence ‘elsewhere’ for historical, international, disciplinary, or other comparisons of data, facts, and events. Policy analysis also refers to analysis for public policymaking, such as the activities, methodology and tools used to assist and advise in the policymaking context (Parsons 1996 ; Hogwood and Gunn 1984 ; Mayer et al. 2004 ; Dunn 1994 ; Fishcer et al. 2007 ). This is also referred to as the interventionist branch of the policy science tree (Enserink et al. 2012 ). As such, policy analysis, as interventionism, likened to other disciplines, needs to bridge the gap between science and action (Latour 1987 ).

Reviewing the literature above, two aspects of policy analysis become very evident. Firstly, policy analysis is a means to improve decision-making supported by evidence and secondly, evidence can also be found elsewhere as argued by Geva-May et al. ( 2020 )—it does not always have to involve conventional policy analysis methods. It is fundamental to note here that the approach and methodology suggested in this article will support other existing forms of analysis, allowing for greater understanding of policy outcomes or the development of better policies.

Radin and Weimer ( 2018 : 8) support this idea by arguing that at the most general level, science in many disciplines produces policy-relevant research that can inform policy design. Guy-Peters et al. ( 2018 ) also concur with this idea, maintaining that in understanding the various alternatives for comparison, it provides interested researchers with flexibility in explaining policy outcomes, although this requires us to be thorough and to avoid bias. Additionally, Radin and Weimer ( 2018 : 2) note that researchers in many fields contribute to knowledge that is potentially relevant to public policy. Guy-Peters and Fontaine ( 2020 : 14) agree that because of the multidisciplinary nature of CPA, it is more akin to multi-methods than any other social sciences areas. It is clear that policy analysis, as an interdisciplinary field, always leaves the door open for alternative knowledge that would improve evidence supporting decision-making. In this article, we explore how the structure found in policies can add insight to our comparative studies.

Drawing on the reviewed literature for this current article, the perspective of ‘ other comparisons of data ’ or alternative knowledge will be taken, by using the emerging SOCS as a pathway to suggest the structure of policies as a common variable for CPA and by extension provide an alternative text-as-data method to policy analysis.

It is important to note that policy analysis methods are used to help analysts to design and assess policy alternatives systematically (Radin and Weimer 2018 : 8). Building on the idea that we can use other evidence to aid analysis, Guy-Peters et al. ( 2018 ) suggest that in comparative work, when focusing on the nature of policy itself, it is amenable to either quantitative or qualitative methods.

The next section conceptualises a public policy as a conceptual system and explains why and how it is amenable to the SOCS. Van de Ven ( 2007 : 278) holds that investigating and analysing the internal logics of policies can broadly be seen as a form of design science, policy science, or evaluation research.

2.1 Public Policy/Models/Theory as Conceptual Systems

Public policies can be viewed as policy design and the output of analysis (Kingdon 1997 ), which means that the documents representing the content of policies can be viewed as shared understanding. These generally include wordy or text-based design artefacts, such as legislation, guidelines, pronouncements, court rulings, programs, and constitutions (Ingram and Schneider 1997 ). These policy designs (their content) can be seen as abstract representations of physical world systems (Schwaninger 2015 , p. 572), which is intentional in approximating physical systems by building an artificial system (Simon 1969 )—this artificial system, can also be found in our conceptual systems.

Policy design as conceptual systems can be conceptualised in the following manner: A system can be seen as a set of elements or parts with interactions among the components of the pattern/structure (Meadows 2008 ). Policy designs as conceptual systems have a structural logic existing of elements (variables/concepts/boxes) and the patterns (causal relations/arrows in a diagram) in which the elements of the policy will occur (Mohr 1987 ). Now, as suggested by Schneider and Ingram ( 1988 ), because we can diagram a sentence linking together parts of speech, it is also possible to diagram the structural logic of a policy. A key assumption of this article is that more useful/effective policies will be more structured.

Wallis ( 2020b ), drawing on Warfield ( 2003 : 515), defines a system as “any portion of the material universe which we choose to separate in thought from the rest of the universe for the purpose of considering and discussing the various changes which may occur within it under various conditions”. He further makes the distinction between the ‘material’ universe as being separate from the ‘conceptual’ universe and emphasises the useful relationship between the two. The SOCS can thus be seen as an extension of systems thinking to describing, investigating, and understanding policy designs as conceptual systems (again extending systems thinking to policy analysis at the conceptual level).

This distinction and maybe more importantly the relationship between the two universes allow for a more holistic view to policies, thus not only studying the material universe “policy environment” systematically, but also making sure that we study our conceptual universe systematically. This is premised on Ashby’s law of Requisite Variety, building on the idea that the control mechanism (policy) must have greater or equal complexity with regard to the system it intends to control, or in this case the environment it intends to address (Ashby 1957 ). This premise suggests benefits of looking at policy models as conceptual systems.

One key benefit of viewing public policy models as conceptual systems is that, by building a policy map, it enables investigations into the likelihood of negative policy interactions (Siddiki 2018 ). Moreover, using the systemic mapping approach to facilitate more readily policies that are built on interdisciplinary theory as the study of policy design as conceptual systems allows us to investigate the policy (and perhaps why it failed) in its entirety, instead of a reductionist approach—as outlined in the introduction.

It was already briefly suggested earlier that the structure of our policies or our conceptual systems has an impact on the practical application or implementation of our policies. As such, drawing from the emerging SOCS, and remembering that policy analysis knowledge can be drawn from various types of evidence or scientific evidence, we now turn to the new science to explore how it can be a common variable in CPA.

2.2 The Importance of Causality for Structure

Causality in this sense can be understood as the relationship between the concepts in ae conceptual system. Additionally, it can be argued that these causal relationships create the structure by connecting different concepts. According to Sloman and Hagmayer ( 2006 : 408), who draw on Bayer’s nets theory, “studies of learning, attributes, explanation, reasoning, judgement and decision making suggest that people are highly sensitive to causal structure.” What is important here is the understanding that causality is essential, and Wallis ( 2016 ) suggests that we can improve the structure of policy by improving the causal relationships between concepts.

With regard to structure, we look at the relationships between the concepts (causal logic); even though in our map’s causal logic (concepts without any causal relation) forms part of the structure. However, the more relationships there are (arrows between boxes/circles) the more structured and the more useful diagram/conceptual system is. In this science, we look at usefulness. Wallis ( 2020c ) makes a good argument for this, drawing on Saltelli and Funtowicz ( 2014 ) for whom “all models are wrong, but some are useful”. This is evident because some policies/theories fail, and others are useful for their purpose. According to Wallis ( 2020c ), the structure of policies represents a kind of usefulness. This has been seen in over 30 years of science investigating structure.

2.3 The Science of Conceptual Systems: A Brief History

Briefly, Cabrera ( 2006 : 3) argues that concepts exist in a system made out of other concepts which has interconnected patterns and is a conceptual ecosystem. These concepts are bound by causal connections, which form propositions that are examples of “a declarative sentence expressing a relationship among some terms” (Van de Ven 2007 : 117) and that create a set of statements understandable to others by making predictions about empirical events (Baridam 2002 : 7). At the elemental level, policies like theories have concepts and causal relations with underlying data that create propositions as understandable statements, which implies that they are commutable and public (Baridam 2002 ). Like theories, we use policies to make predictions about empirical events, such as implementing COVID-19 regulations and measures (problems and solutions on paper) in the hope of stopping infections and eventually having a virus free country (empirical event), such as New Zealand and others.

According to Wallis ( 2016 ), the SOCS is aimed at the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of conceptual systems whilst using rigorous methodologies. At least three streams of research on structure suggest that structured knowledge is useful for changing the world positively and reaching desired goals. These streams are as follows:

In the field of education/human development, “Systematicity” is used to evaluate the structure of maps and evidence. This suggests that beginners create simplistic low structured maps compared with the more structured and complex maps of experts (Novak 2010 ).

In the field of political psychology, the measure of Integrative Complexity has been used for the past 30-years (Suedfeld et al. 1992 ; Wong et al. 2011 ).

The third stream of research on structure involves studies of formal theories and policy models within and between multiple disciplines (Wallis et al. 2016 ).

The third stream, which is of great significance for this current article is IPA.

2.4 The IPA Method

According to Wallis ( 2016 ), IPA is primarily used to analyse conceptual systems from text on paper to determine their structure (Wallis 2016 ). The IPA methodology uses the policy document’s text itself as data (Wallis 2016 : 585). This process includes the following six steps: (1) Identify propositions within one or more conceptual systems (models, etc.). (2) Diagram those propositions with one box for each concept and arrows indicating directions of causal effects. (3) Find linkages between causal concepts and resultant concepts between all propositions. (4) Identify the total number of concepts (to find the Complexity). (5) Identify concatenated concepts. (6) Divide the number of concatenated concepts by the total number of concepts in the model (to find the Systemicity).

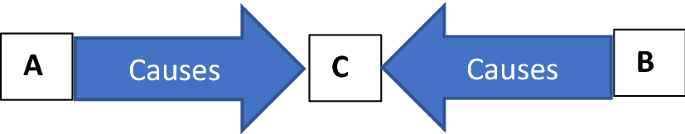

For a very brief and abstract example, consider Fig. 1 . The figure has three variables/concepts (A, B, C), therefore, the Complexity is C = 3. There is one concatenated concept (C). So, the Systemicity is C = 0.33 (the result of one concatenated concept divided by three total concepts).

Abstract example of a model for demonstrating IPA

Concepts (relating to variables) are enumerated to show the Complexity or explanatory breadth of the conceptual system. The causal interconnectedness of those concepts is evaluated for their Systemicity (structure, or explanatory depth). Systemicity is measured on a scale of zero to one with one being the highest (Wallis and Valentinov 2017 : 109). Using IPA, Complexity, on its own, is seen as a weak indicator of success for a conceptual system, building on the idea of the SOCS. The main concern for this measurement of structure is that those theories, policy models and general conceptual systems with a higher level of structure are more useful for practical application and implementation.

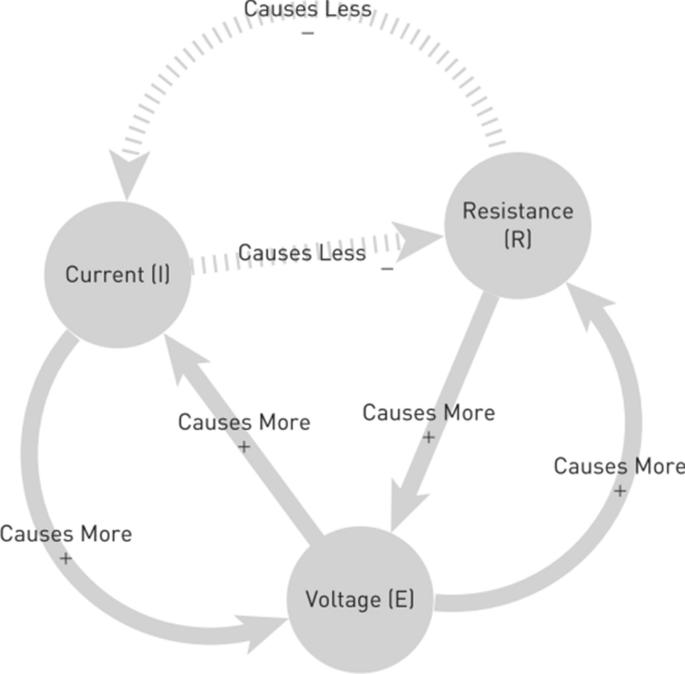

It can be argued that the external validity of the methodology has been established. Firstly, the findings suggest that theories in the natural sciences have high levels of structure (Systemicity) and are proved to be effective and useful in application, such as Ohm’s Law (Wallis 2016 , b ; Wallis 2010a , b ). In contrast, theories in the social sciences have a Systemicity generally of less than 0,25, including theories of conflict, psychology, and very important for this article, policies (Wallis 2010a , b , 2011 ; 2013 ; Shackleford 2014 ; Parmentola et al. 2018; Wallis et al. 2016 ; de Wee 2020 ; de Wee & Asmah-Andoh, in press). Correlating with these findings, Light ( 2016 ) found that policies in the United States of America only succeed 20% of the time. This is parallel to the 0, 25 Systemicity generally found in social sciences, which essentially translates to a 75–80% chance that most of our policies could fail.

2.5 The Conceptual System: A Basis for Comparison

Briefly, in SOCS, using IPA, we quantify and diagram the structural logic of the policy, and find links between the measure (percentage providing a predictor) of the policy structure and its usefulness in the real world. As a brief example, one could consider Figs. 2 and 3 that are maps of different theories, one from physical science and the other from social science. These propositions are mapped out to indicate how we can use the structure found in any policy as the basis of comparison.

Georg Ohm developed the propositions: An increase in resistance and an increase in voltage would result in an increase of current, which will cause a decrease in resistance. An increase in current causes an increase in voltage that would result in an increase in resistance, which will cause a decrease in current.

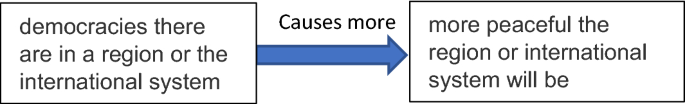

The democratic peace proposition has many possible empirical and theoretical forms. One of these holds that “the more democracies there are in a region or the international system, the more peaceful the region or international system will be” (Reiter 2012 )

The structural logic of Ohm's law as a practical map (Wright and Wallis 2019 , p. 152)

Source : Authors own compilation

The structural logic of the democratic peace proposition as a practical map.

The two brief examples were created using IPA steps 1–3 (to diagram) and the person reading these propositions from any country who reads the English language can see the causal relations between the concepts. This is the benefit and perhaps the most important contribution of the SOCS and IPA to CPA. Firstly, the examples indicate how IPA takes a “common denominator” approach by presenting theories graphically in an easily understandable format of concepts (in boxes/circles) and causal arrows (indicating the direction and causality) (Wallis 2020a , b , c ). The key contribution here is that with IPA we have an objective and rigorous method we can use to evaluate, analyse, and develop policies based on their structural logic, which was first suggested by Schneider and Ingram ( 1988 ); however, without a clear measure. Furthermore, it also provides a “common language” for interdisciplinary work, which is important for policies if they are to be successful, remembering of course that no problem in policy is ever addressed using only ‘one’ policy. As Siddiki ( 2018 ) found, policies that are used to address a problem often led to inter policy conflict that causes problems with “policy coherence”, which May et al. ( 2006 ) refer to in terms of how well policies with similar objectives fit or go together.

Additionally, IPA and the SOCS can be of great benefit for policy design and CPA. Applying the IPA’s steps 4–6 to Figs. 2 and 3 , their level of structure differs significantly. Ohm’s law has a structure/Systemicity of 1 (100% usefulness in application) and the democratic peace proposition, has a structure/Systemicity of 0. In the real world, Ohms law has been very successful, and the democratic peace theory has numerous shortcomings.

For years, it has been accepted that policy designs are “copied, borrowed or pinched” from similar policies in other locales (Schneider and Ingram 1988 : 62) which makes policy design less a matter of invention than of selection (Simon 1981 ) involving large stores of information and making comparisons. However, this led to suboptimal situations where policy layering and patching is done haphazardly (Van der Heijden 2011 ) leading to a palimpsest-like mixture of incoherent or inconsistent policy (Howlett and Rayner 2007 ; Carter 2012 ). Again, perhaps using IPA and viewing policies as conceptual systems allows one to create coherent policies more easily, which are argued to be more effective in application (Siddiki 2018 ).

Based on the case made earlier, this stream of research seems to provide policy analysis with policy-relevant research that can inform policy analysis (Geva-May et al. 2020 ; Guy-Peters et al. 2018 ; Radin and Weimer 2018 ). Hence, it provides this current article the basis for suggesting the evaluation of the structure of policy as a common variable to be used in CPA, additionally because this “on paper” analysis provides a new text-as-data approach. Although other aspects of policymaking and analysis, such as empirical data and the implementation process, are important, we suggest focussing on the structure of policy in comparative analysis. This article suggests the different but allied perspective that this stream of research provides, which will be explained later.

Extending on the above, pragmatically, inter-rater evaluation can be done, where scores of the analysis can be compared and the consensus of the raters measured through agreement or concordance (Bless et al. 2016 : 226). Prior studies indicate how a repeated study using the same data would have stable findings over repeated observations, which confirms its external validity, or generalisability (de Wee 2020 : 135).

In the followings section, we turn to IPA and the application of the method on conceptual systems including policy. The section not only demonstrates the methodology but also the use of the method on policy in previous research. Additionally, it indicates how less “financially demanding” the method is than the computational and statistical models. Based on using textual analysis (IPA) on policy, the article suggests that this is an alternative or new pathway to compare, analyse and evaluate policies. The next section discusses text-as-data and the SOCS compatibility with it.

2.6 A New Text-as-Data Approach: The Basis for Collaboration and Interdisciplinary Policy Development

Current research (Fisher et al. 2013 ; Leifeld 2013 ; Guy-Peters and Fontaine 2020 ; Leifeld and Haunss 2012 ) indicates the prevalence of qualitative text analysis methods in policy analysis, including the discourse networks that rely on text analysis to measure discourse coalitions quantitatively through network analysis. Guy-Peters and Fontaine ( 2020 : 204) argue that text-as-data-methods for CPA can include new theories and methods relevant to public policy and policy analysis.

Guy-Peters and Fontaine ( 2020 ) identify the different directions text-as-data application is currently developing. Firstly, there is causality, with Egami et al.’s ( 2018 ) framework of estimating causal effects in sequential experiments. Owing to limited space, this process will not be explained in full (see Egami et al. 2018 ). Secondly, there is computer science research on word embedding and on artificial neutral networks, which is what they call ‘deep learning’ (LeCun, Bengio & Hinton 2015 ). From the findings of Guy-Peters and Fontaine ( 2020 ), it becomes apparent that the use of statistical and computational analysis is a challenge in the discipline, especially because there are no globally best methods for retrieving certain information from text. Secondly, with manual approaches, this is practically impossible because of the prohibitive costs (Guy-Peters and Fontaine 2020 : 213).

This article suggests a key benefit of viewing the IPA method as part of the SOCS when doing CPA as a new “text-as-data” technique. IPA objectively evaluates structure, and it provides a way for comparison. Additionally, the text-as-data method outlined in the most current literature tends to have two key problems: firstly, it is difficult to use and secondly, it is expensive and practically impossible. To the field of CPA, IPA provides a method that can be used easily and with rigor, which is not mentally taxing or too expensive. To the text-as-data method, this article provides accessibility. The IPA method is more accessible and can be applied with ease by scholars and practitioners from various countries and various disciplines to improve the policies they design. This method also provides a basis from which interdisciplinary work on policy can branch out.

As such, when analysing policy, one can do a within-case analysis and thereafter a cross-case comparison, to generalise findings further, whilst considering the context. However, we will explore this further in the next section.

2.7 Collaboration and Interdisciplinary Perspectives Based on Policy Structure

In fact, the IPA methodology and the resources to assist in the application are readily available online at https://projectfast.org/ , where there are additional tools to enhance the analysis, which can introduce more collaboration. Collaboration can be achieved, through analysing a policy individually and outcomes. Or you can build or analyse the policy together using the six-steps of IPA on the free online social network analysis software KUMU ( www.kumu.io ). This platform allows participants in policy analysis or policy making to organise complex information (concepts and causal relations of a policy based on IPA), to diagram graphically, to build and to analyse policies based on their structure. This platform is open for multiple participants globally who are given permission to participate. Potentially, all participants can have the same policy or empirical data/research and can build a policy or map on this platform; however, this article will present more on this topic in the section on future research areas and implications .

This article argues that when exploring integration studies and literature around interdisciplinary research or problem solving, it becomes apparent that we can use an interdisciplinary approach, which can clarify the observer’s standpoint, define and orient the observer to a problem. Moreover, this approach can be used to map the full social and decision-making context and apply multiple methods to generate, evaluate and implement solutions (Clark 2002 , 2011 ).