- Search Site

- Campus Directory

- Online Forms

- Odum Library

- Visitor Information

- About Valdosta

- VSU Administration

- Virtual Tour & Maps Take a sneak peek and plan your trip to our beautiful campus! Our virtual tour is mobile-friendly and offers GPS directions to all campus locations. See you soon!

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Meet Your Counselor

- Visit Our Campus

- Financial Aid & Scholarships

- Cost Calculator

- Search Degrees

- Online Programs

- How to Become a Blazer Blazers are one of a kind. They find hands-on opportunities to succeed in research, leadership, and excellence as early as freshman year. Think you have what it takes? Click here to get started.

- Academics Overview

- Academic Affairs

- Online Learning

- Colleges & Departments

- Research Opportunities

- Study Abroad

- Majors & Degrees A-Z You have what it takes to change the world, and your degree from VSU will get you there. Click here to compare more than 100 degrees, minors, endorsements & certificates.

- Student Affairs

- Campus Calendar

- Student Access Office

- Safety Resources

- University Housing

- Campus Recreation

- Health and Wellness

- Student Life Make the most of your V-State Experience by swimming with manatees, joining Greek life, catching a movie on the lawn, and more! Click here to meet all of our 200+ student organizations and activities.

- Booster Information

- V-State Club

- NCAA Compliance

- Statistics and Records

- Athletics Staff

- Blazer Athletics Winners of 7 national championships, VSU student athletes excel on the field and in the classroom. Discover the latest and breaking news for #BlazerNation, as well as schedules, rosters, and ticket purchases.

- Alumni Homepage

- Get Involved

- Update your information

- Alumni Events

- How to Give

- VSU Alumni Association

- Alumni Advantages

- Capital Campaign

- Make Your Gift Today At Valdosta State University, every gift counts. Your support enables scholarships, athletic excellence, facility upgrades, faculty improvements, and more. Plan your gift today!

Developing a Research Topic: Concept Mapping

- Concept Mapping

- Developing Keywords for Searching

- Boolean, Truncation, and Wildcards

- Topic Ideas

- Writing a Research Question

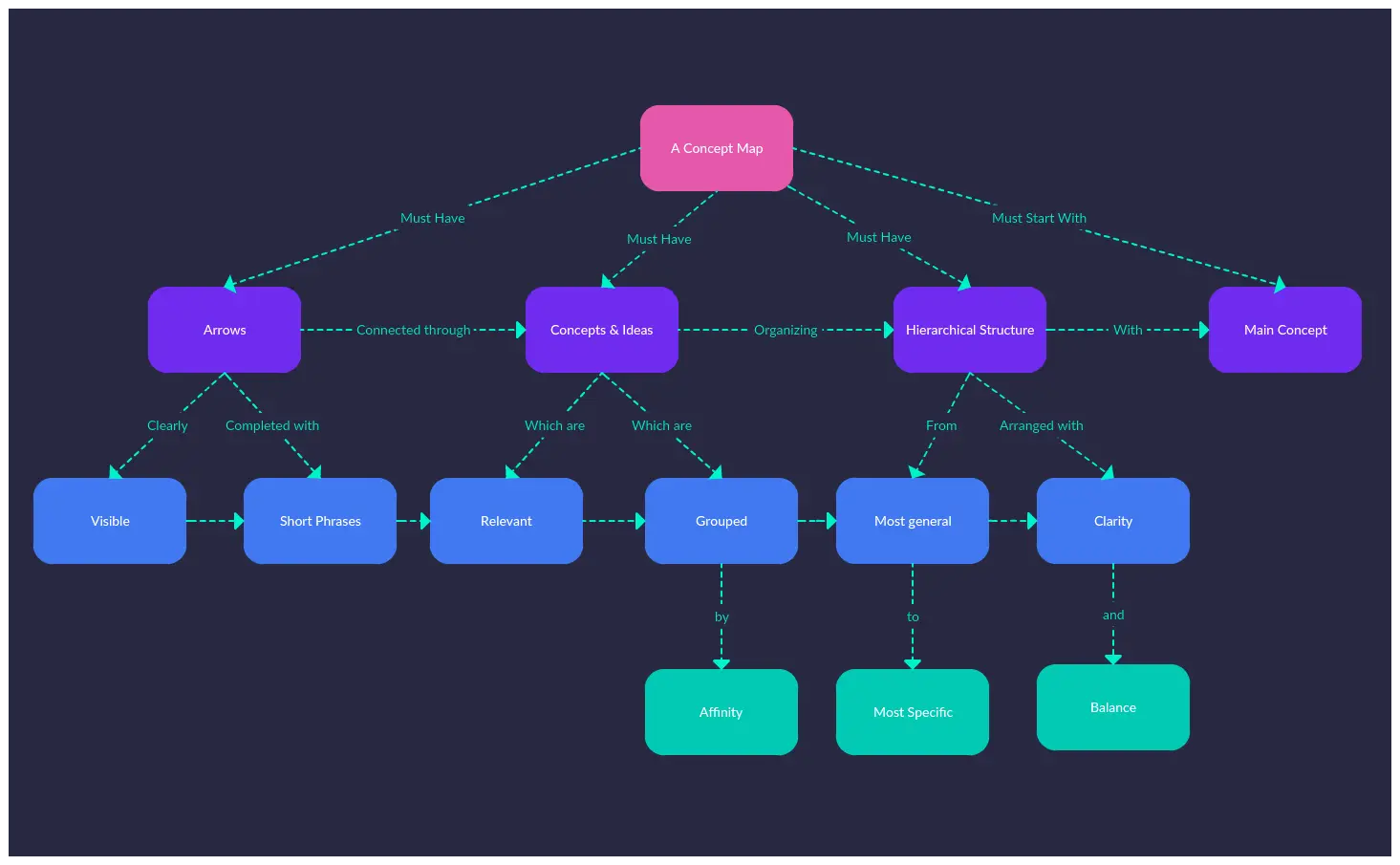

Concept Map / Mind Mapping

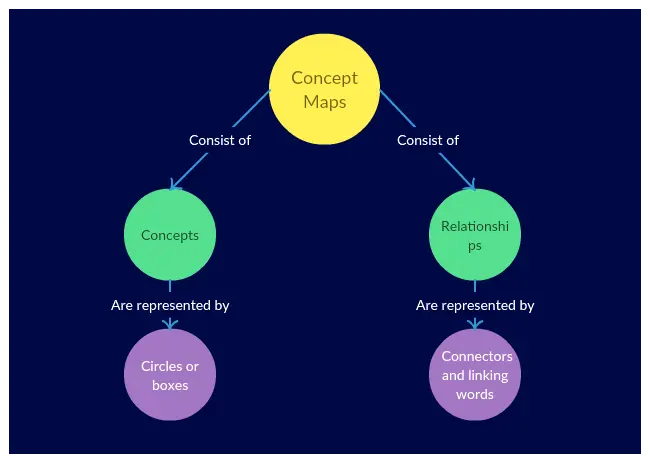

What is a concept map.

A concept map is a visual representation of what you know about a topic. Concept maps help you organize your thoughts and explore the relationships in a topic. Use a concept map to organize and represent what you know about a topic. Explore the connections between elements of the topic.

Why use a concept map?

Concept maps can be used to develop a research topic. They are a useful brainstorming tool.

Concept maps can be used to study. Mapping what you know about a subject and examining the relationships between elements help you develop a greater understanding of the material.

How do I create a concept map?

- On a whiteboard

- Any way that works for you!

How do I organize the map?

Most of the time you start with the central idea, topic, or subject. Then you branch out from that central point and show how the main idea can be broken into specific subtopics. Each subtopic can also be broken into even more specific topics,

Make a Research Appointment

Click Make a Research Appointment to schedule a meeting with a librarian!

Organize what you know by subtopic in a topic map.

Use the topic map to define your research topic.

For example: geography - local travel - rail - variants - rail systems - designs & availability - emissions - research & evidence

Make a topic statement or research question.

I am researching the environmental impact of using commuter rail systems in cities.

How does using commuter rail systems in cities affect the environment?

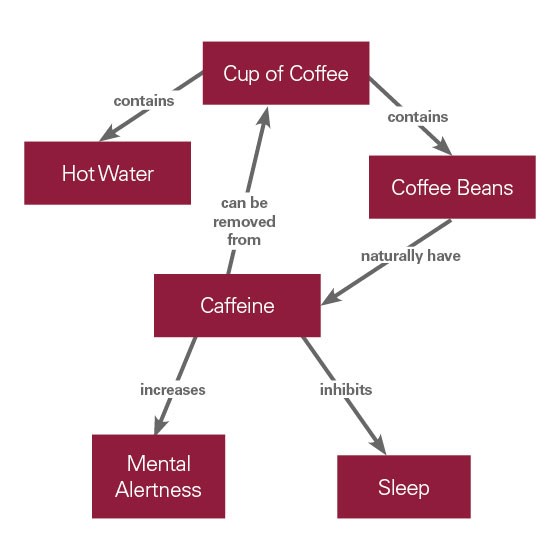

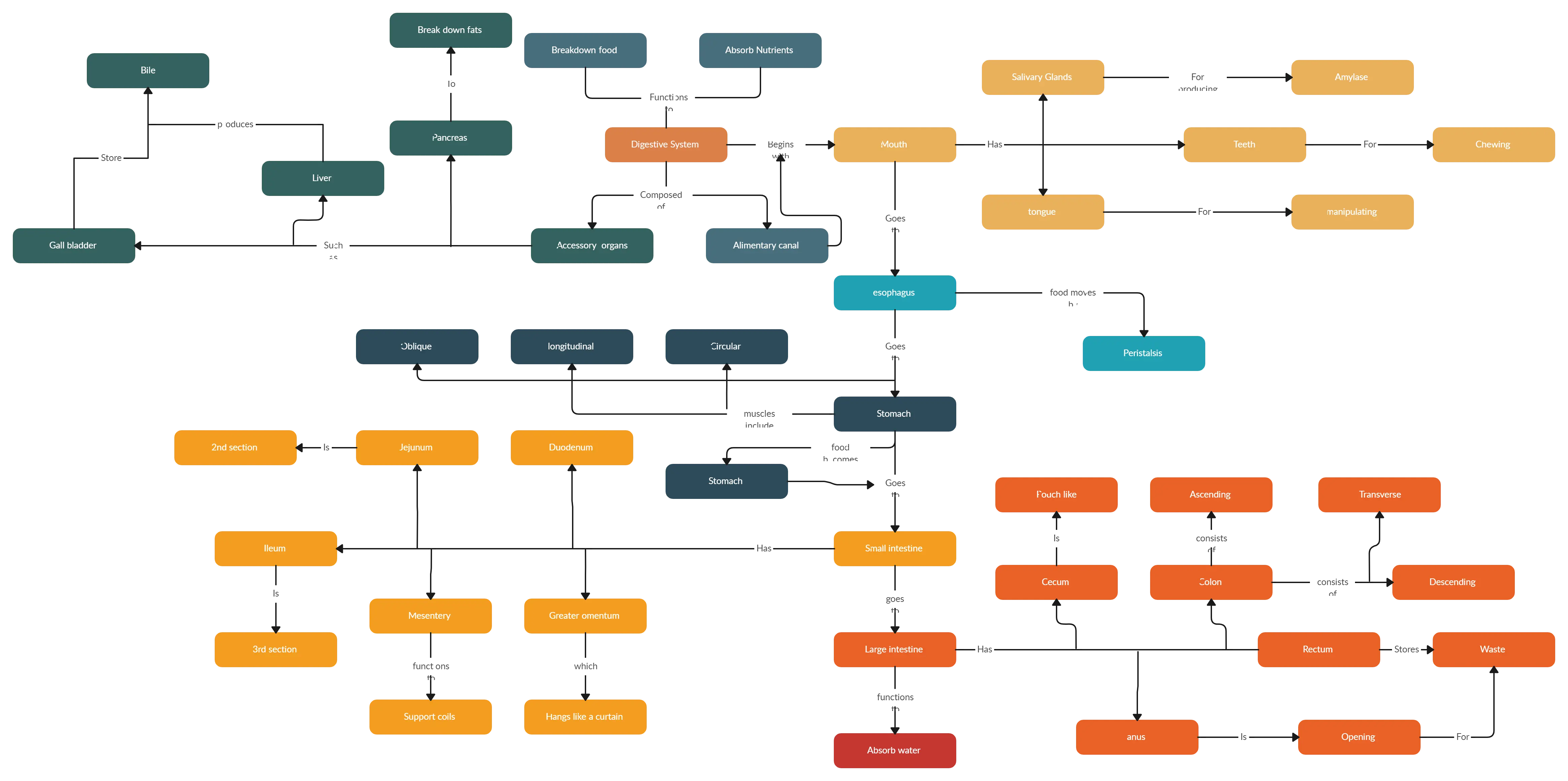

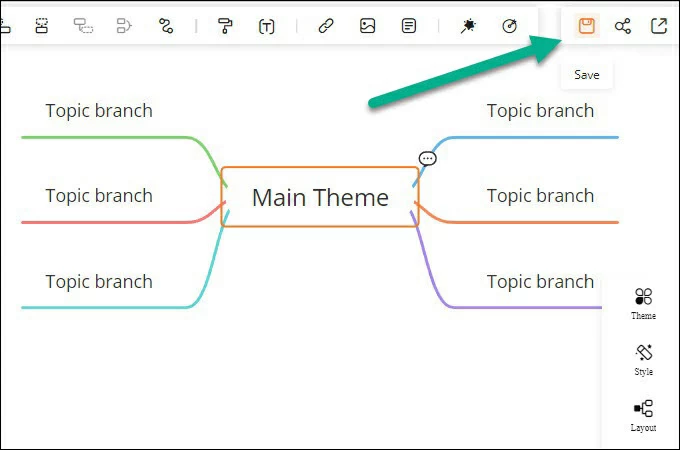

Concept Map, Mind Mapping

Example concept map.

- Next: Developing Keywords for Searching >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2023 11:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.valdosta.edu/research-topic

- Virtual Tour and Maps

- Safety Information

- Ethics Hotline

- Accessibility

- Privacy Statement

- Site Feedback

- Clery Reporting

- Request Info

6 ways to use concept mapping in your research

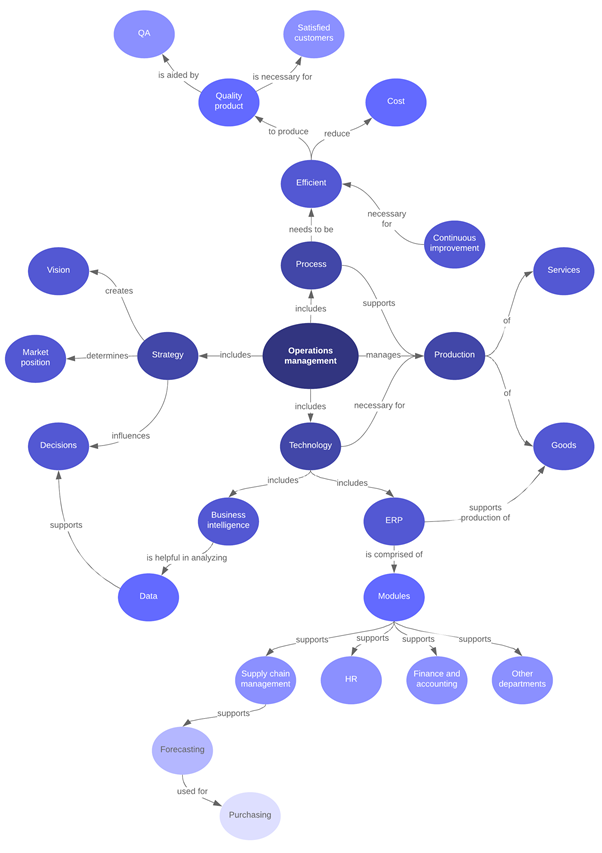

Joseph Novak developed concept mapping in the 1970s and ever since, it has been used to present the construction of knowledge. A concept map is a great way to present all the moving parts of your research project in one visually appealing figure. I recommend using this technique when you start thinking about your new research topic all the way through to the end product, and once you submitted your thesis, dissertation or research article, you can use concept mapping to plan your next project. If you prefer to watch the video explaining the 6 steps, scroll down.

What is the purpose of concept mapping?

You may wonder what the purpose of a concept map is. A concept map shows the different “ideas” which form part of your research project, as well as the relationships between them. A concept map is a visual presentation of concepts as shapes, circles, ovals, triangles or rectangles, and the relationships between these concepts are presented by arrows. Your concept map will show the concept in words inside a shape, and the relationship is then presented in words next to each arrow, so that each branch reads like a sentence. What is the difference between a mind map and a concept map? A mind map is different from a concept map in that a mind map puts much less emphasis on the relationship between concepts.

How to use a concept map in your research

Don’t wait to put your concept map together until only after you have, what you consider, “all the knowledge” and have read “all the literature” (anyway, with two million research articles published each year, will that day ever come?). In the very early stages, when you start thinking about your research project, draw your concept map to get your thoughts organised. Then, as you become more and more abreast with the research out there, modify your concept map.

The process of creating a concept map is an iterative one and you will find that it feels like you have drawn and redrawn the map over and over so many times that you wonder if you are ever going to get to a final version. This process in itself is a learning experience and is vital to sort the concepts out for yourself. If you have clarity in your own head, it is easier to explain what your research is all about to someone else. In addition, including a concept map into a dissertation, thesis, or research article (where relevant) makes it easier for the reader (including the examiner or reviewer) to understand what your research project is all about. There are several instances in your research journey where a concept map will come in handy.

#1 Use a concept map to brainstorm your research topic

When you are conceptualising your research topic, create a concept map to put all the different aspects related to your research topic onto paper and to show the relationships between them. This will give you a bird’s eye view of all the moving parts associated with the chosen research topic. You will also, most probably, realise that the topic is too broad, and you’ll be able to zoom in a bit more to focus your research question better. But before you settle on a specific research question, do a bit of reading around the topic area. Your concept map will show you which keywords to search for.

#2 Use a concept map when planning the search strategy for your literature review

Jumping right into those databases to do a search for articles to include in your literature review can really take you down the deepest darkest rabbit hole. One of those where you find an appropriate article, then gets suggested a few related articles and then you find another few related articles to the related articles, and after 4 hours you can’t even remember what your actual focus was. To avoid this situation, draw your concept map first. You can use the concept map you drew when you brainstormed your research topic to give you guidance in terms of the keywords to search for. Planning your search strategy before you jump in will ensure that you remain on the well-lit path.

#3 Add a concept map to your completed literature review chapter

As you read more about your research topic, you’ll get a better idea of the relationships between the current concepts, and you’ll find more concepts to add to your concept map. Adapt your concept map as you go along, and once you have the final version of your literature review, add your concept map as a figure to your literature review chapter. This will give the reader a good overview of your literature review and it will make their hearts happy because we all know how nice it is to be rewarded with a picture after reading pages and pages of text.

#4 Use a concept map to plan your discussion

Once you completed your data analysis and interpretation, developing a concept map for your discussion will give you clarity on what to include in your discussion chapter or section.

#5 Add a concept map to your completed research project

Once you have completed your entire research project and you want to show how your findings filled a gap in the literature, you can indicate this by modifying the concept map which you created for our literature review. This is a great way to show how your research findings have added to the existing concepts related to your research topic.

#6 Use a concept map to show your research niche area

You can use a concept map to visually present your own research niche area and as your career progresses and you create more knowledge in a specific niche, you can add to your concept map.

How to make a concept map for research

Go to a place where there are very few distractions, a place that is conducive to letting those creative juices flow freely. Seeing that we all function differently, shall I rather say, a place which you perceive as having few distractions. It may be in a park, in your garden, at a restaurant, in the library or in your own study.

Take out a blank piece of paper and start thinking about your research project. Of course, you can do it on a blank page on your laptop as well. One of my students used sticky notes with each sticky note presenting a concept, and with smaller strips of sticky notes showing the relationships between concepts. You can even get all fancy and use concept mapping software. But as a start, a blank piece of paper is more than enough.

Jot down all the ideas that come to mind while you answer the following questions: What is your research about? Why is your research important? What gap does your research fill? What problem will your research solve? What influences your research outcome? Just jot all your thoughts down. Then, once you have all your thoughts on paper, see if you can identify some relationships between the concepts which you noted down. What comes before what? What is a consequence of what? What is associated with what?

Once you are happy with what you have put together, present it to a friend, preferably at a time when both of you are not in a hurry to get somewhere. At a bar with loud music may not work well, and on a first date may also not be a good idea. Explain what is going on in the concept map and give your friend a chance to ask some questions. As you explain it to someone, as well as through fielding your friend’s questions, it will start to make more sense to you, and you will most probably move some concepts around and add new ones. Repeat this process with someone else when you feel you need some more input.

If you are planning to feature your concept map in your thesis, dissertation or research article, now is the time to turn your rough concept map into something more presentable. One can easily get totally lost when it comes to choosing software to create a concept map. Some of the software out there is paid for while others give you a free version for some basic concept mapping. Be careful of that software which only gives you free access for 30 days, remember, you are going to change your concept map quite a few times as time goes on. If you prefer to use software which you are already familiar with, why not just do it in PowerPoint or Word? On the other hand, Lucidchart is really user-friendly. Watch the video below to see how easy it is to create a concept map with Lucidchart. Explore a few options and see what works for you, but be careful, this exploration can take you down that 4-hour rabbit hole and when a proposal submission deadline is looming, that rabbit hole is a dark place to be in.

We'd like to acknowledge Coffee Machine Cleaning for the image of the coffee cup and notebook used in this blog post.

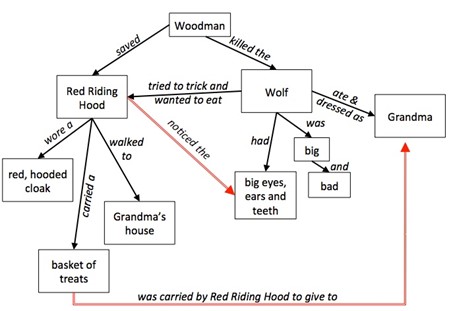

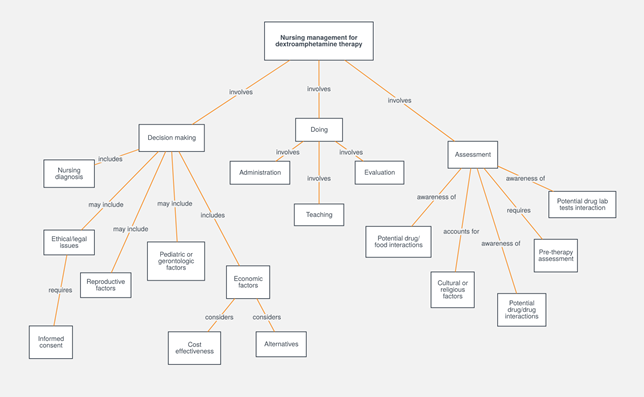

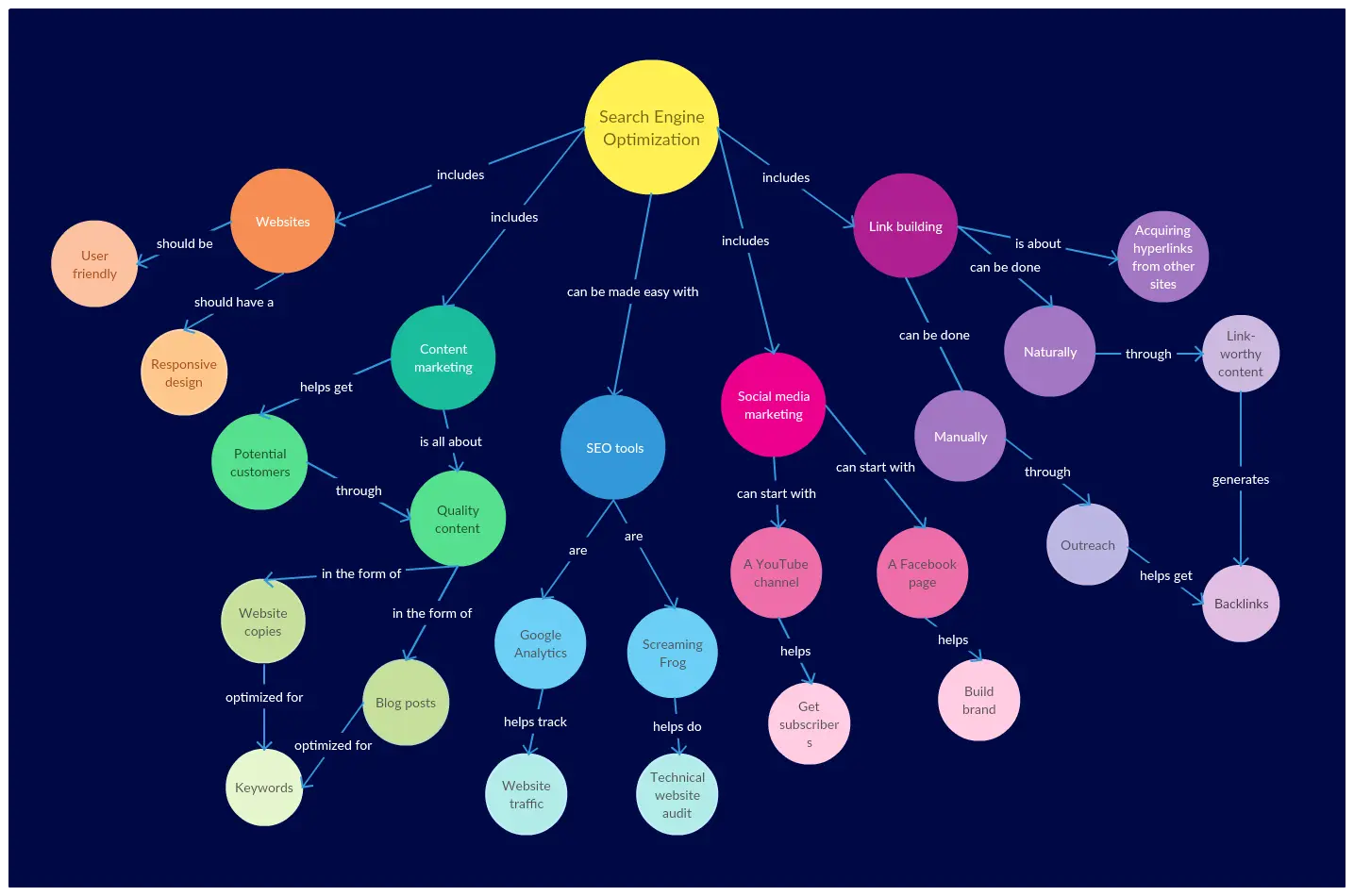

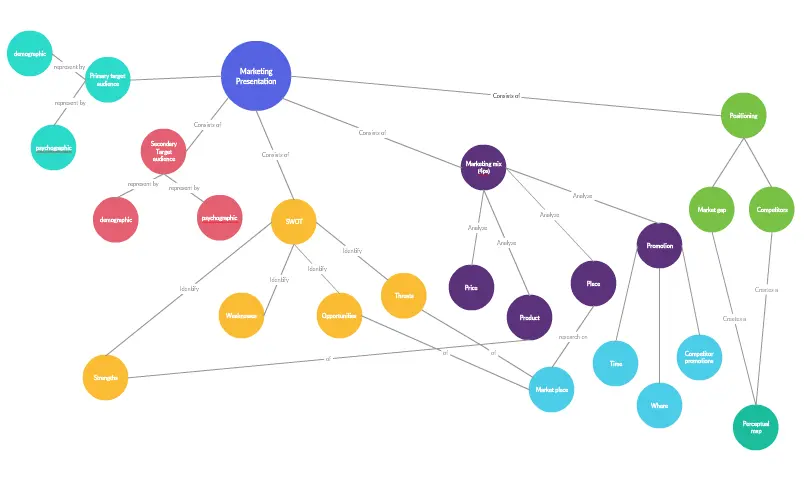

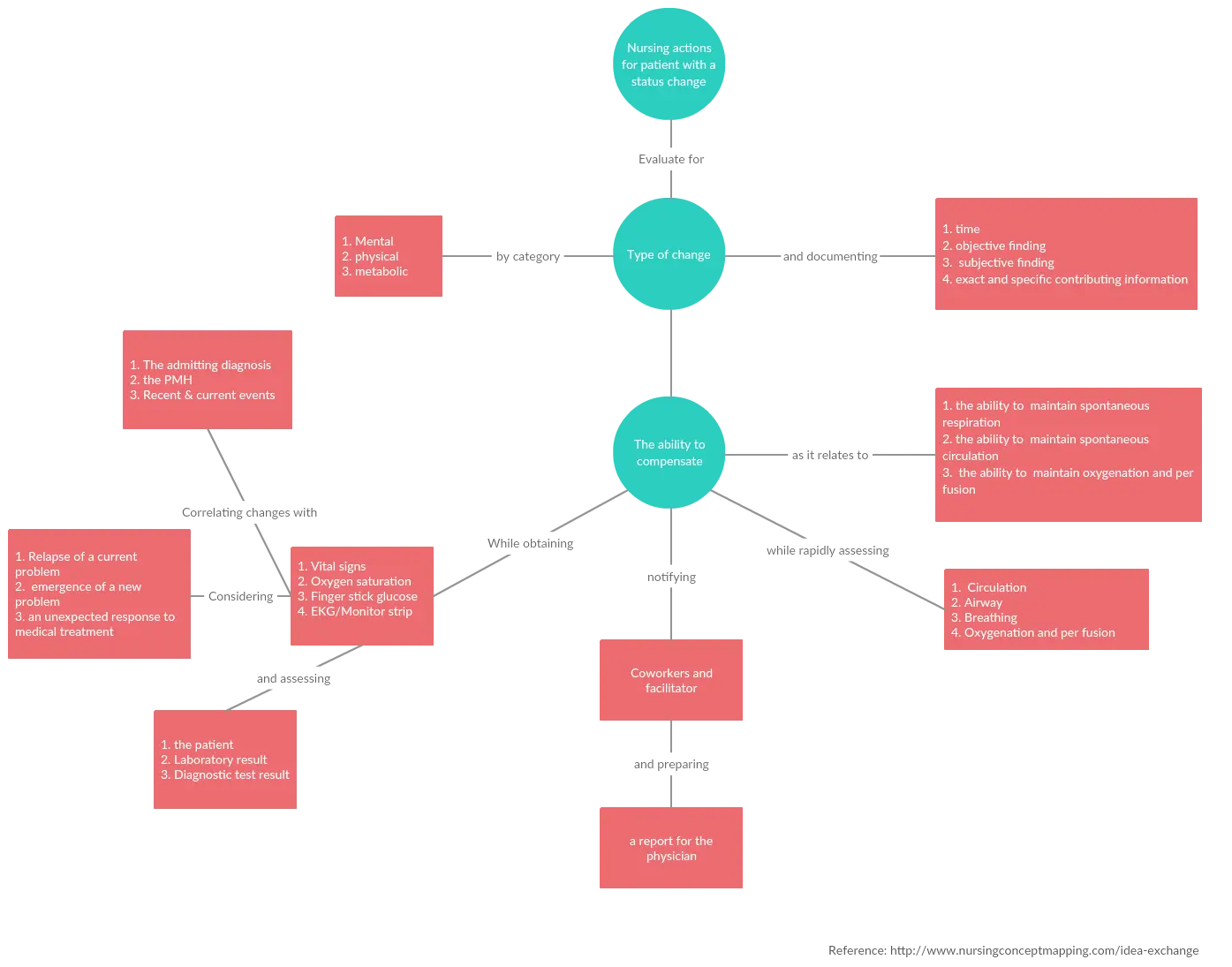

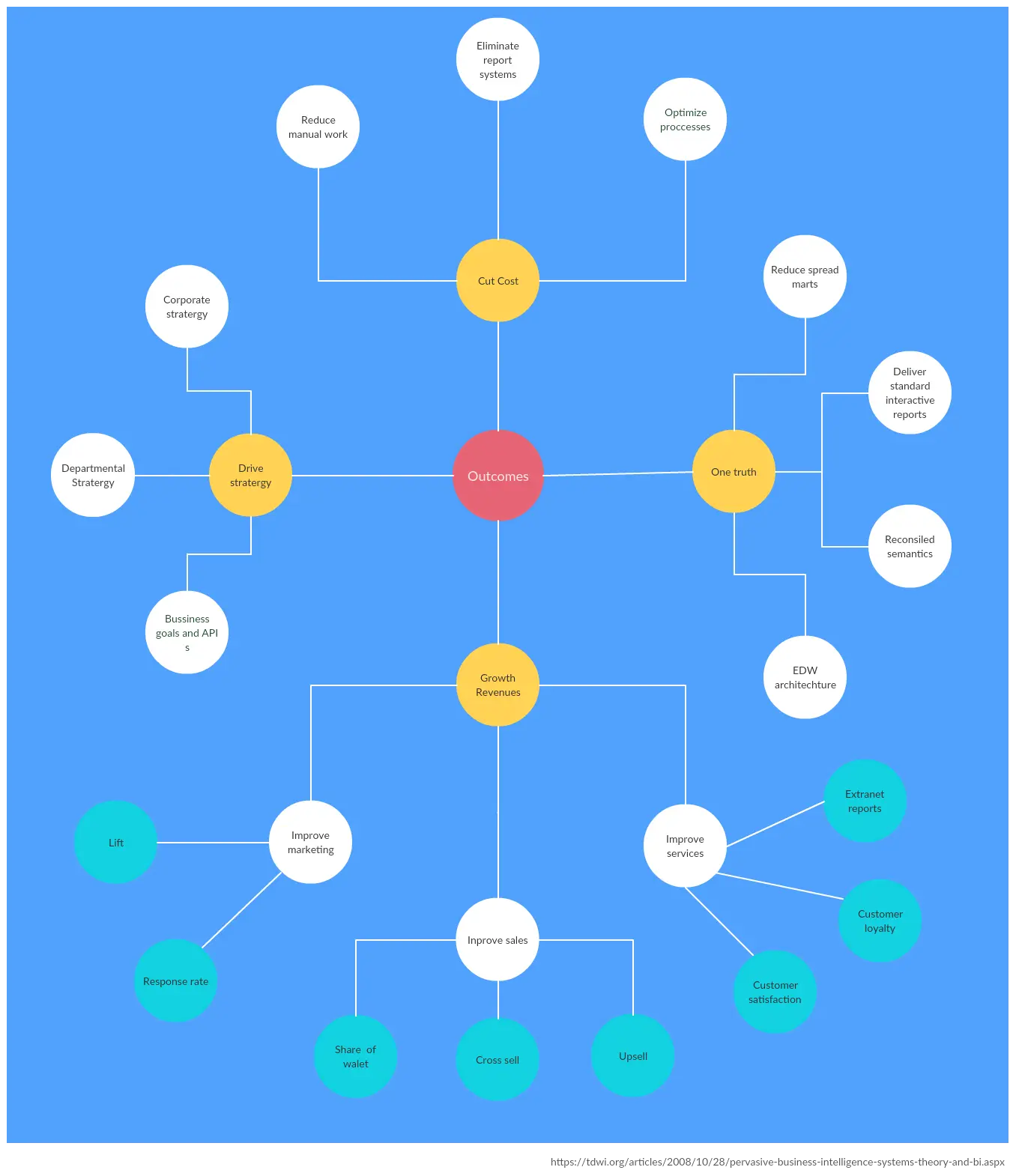

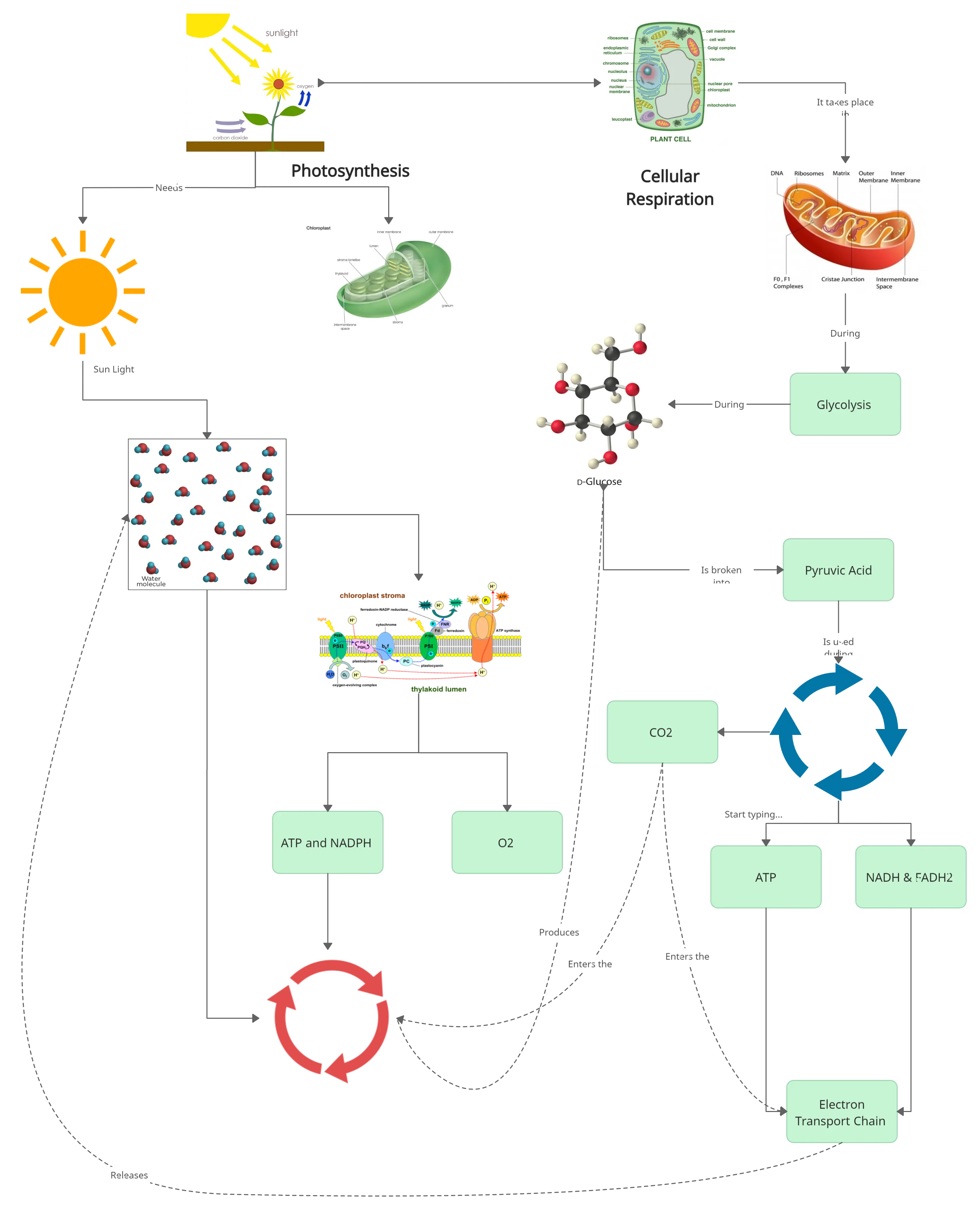

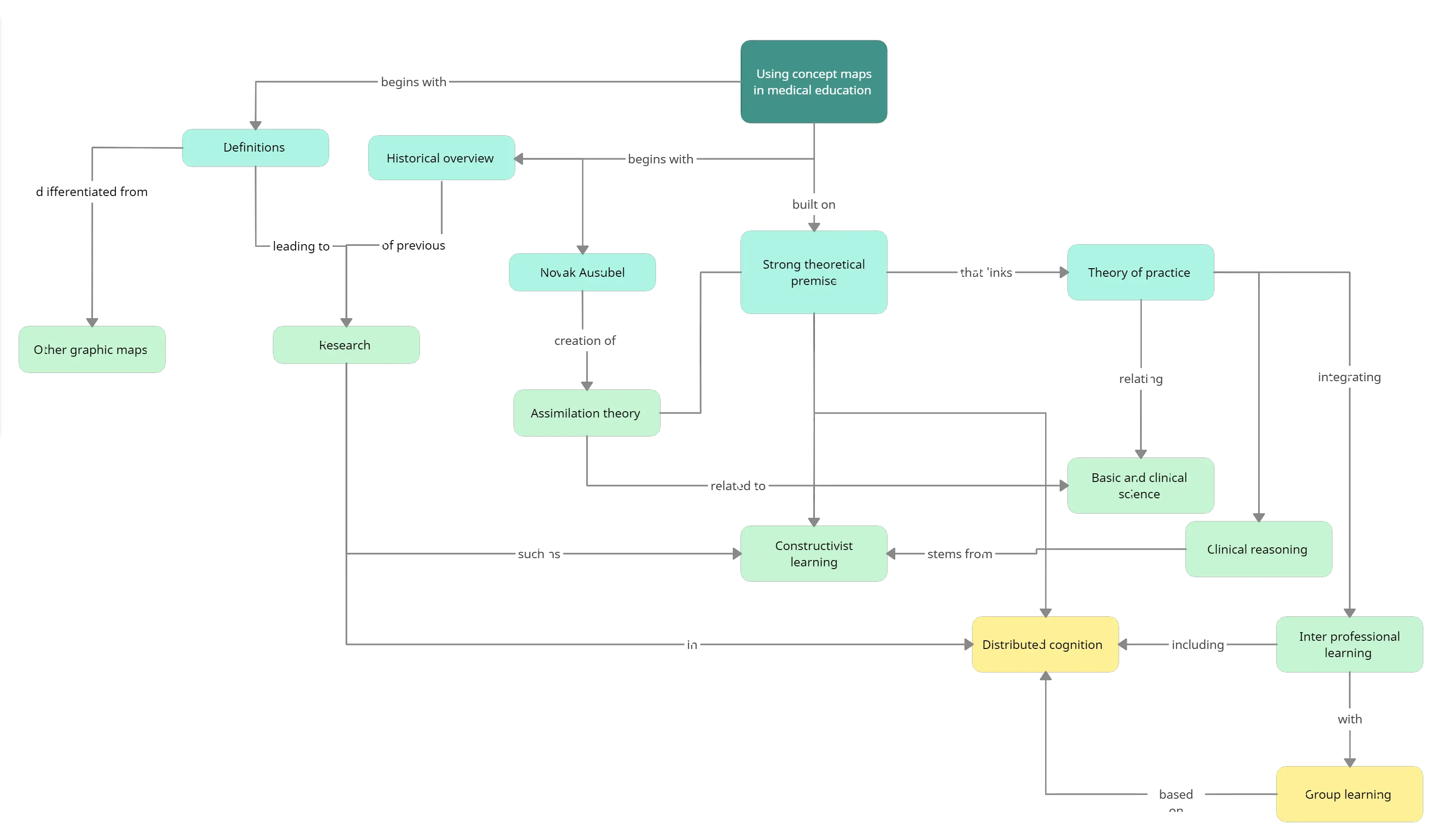

Examples of concept maps

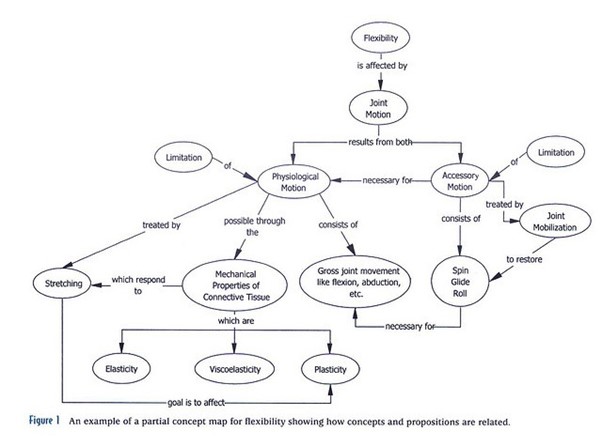

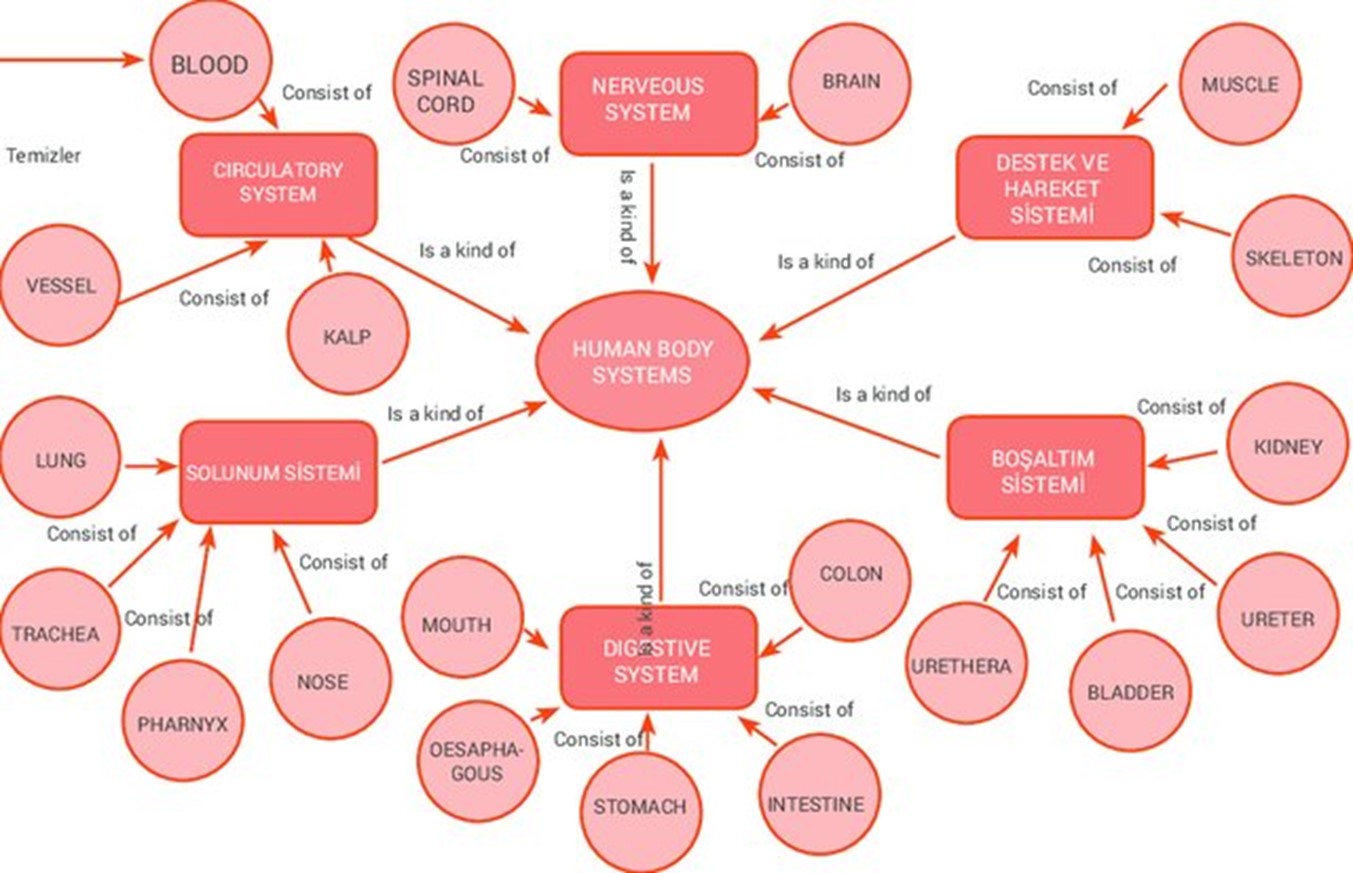

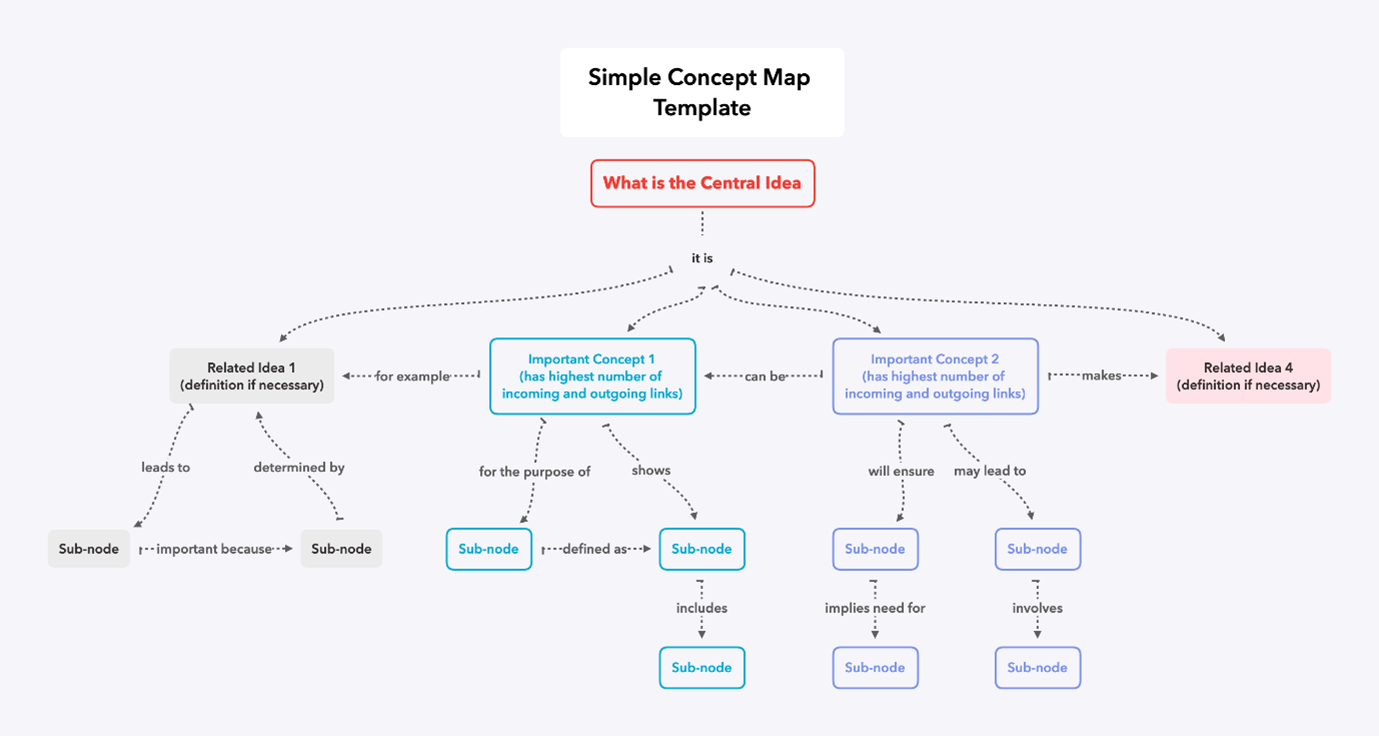

Here are a few examples of concept maps that show the concepts and the relationship between the concepts well. Click on the image to visit the original source. Go and enjoy developing a concept map for your research!

One last thing before you go, for more valuable content related to academic research, subscribe to the Research Masterminds YouTube Channel and hit the bell so that you get notified when I upload a new video. If you are a (post)graduate student working on a masters or doctoral research project, and you are passionate about life, adamant about completing your studies successfully and ready to get a head-start on your academic career, this opportunity is for you! Join our awesome membership site - a safe haven offering you coaching, community and content to boost your research experience and productivity. Check it out! https://www.researchmasterminds.com/academy .

Example 1 Little Red Riding Hood

Example 2 Nursing Management

Example 3 Operations Management

Example 4 Cup of Coffee

Example 5 Flexibility

Example 6 Human Body Systems

Example 7 Simple Concept Map Template

If you prefer to watch the video, here it is:

Leave a comment

How To Write a Research Paper

- 1. Understand the Assignment

- 2. Choose Topic & Write Thesis Statement

- 3. Create Concept Map & Keyword List

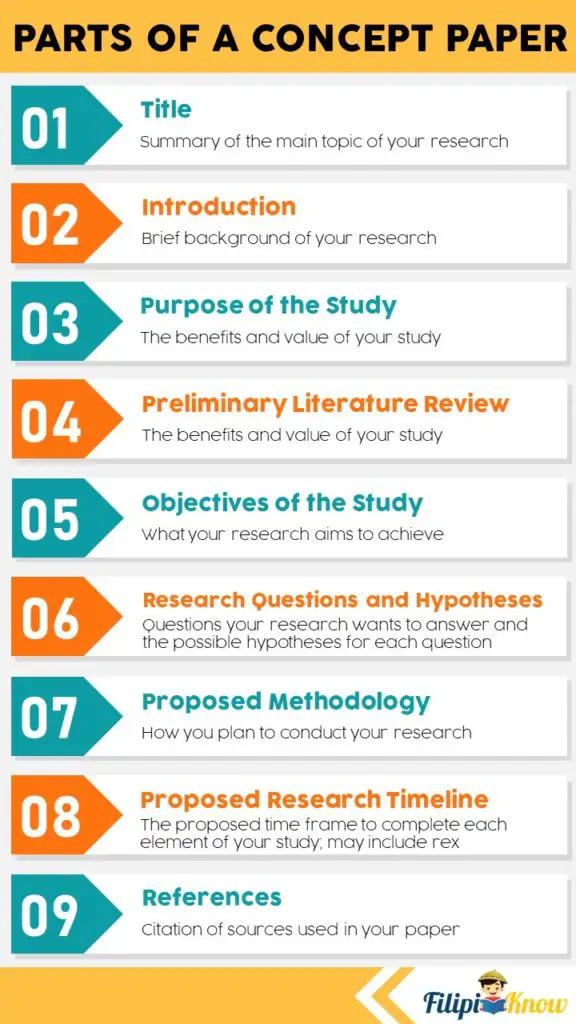

Create a Concept Map

Make a list of keywords / search terms.

- 4. Research Your Topic

- 5. Create an Outline

- 6. Write the Paper

- Assignment Calculator

Create a concept map of your topic. A concept map is a visual diagram that shows the relationship between different ideas related to your topic.

To create a concept map:

- Who is affected?

- Who is affected? -- Children, Men, Women

- Causes -- Genetics, Poor diet, Sedentary lifestyle

- Effects -- Poor mental health, Poor physical health, Low self-esteem

- Prevention -- Better diet/nutrition, More exercise/physical fitness, Better medical interventions

- The sub-sub topic Poor Diet be broken further into -- More fast food, Bigger portion sizes, Higher caloric intake, etc.

Selecting the right keywords is important when you begin searching. Keywords are the most important parts of your topic and are necessary to properly communicate with the different research tools you'll be using. Here are some tips to choosing keywords:

- Never use whole sentences or long statements

- Nouns usually make the best keywords

- Keep adding, subtracting, and replacing keywords you use to find a variety of results

- Expand your list by using synonyms, subject terms, and more specific concepts

Below are some examples of education-related keywords to help you get started:

After you have chosen your keywords, you'll want to combine them to form a search statement . You can combine words using "AND" in between. Have more than one word as a keyword? Put quotations around it. This will tell the database or search engine that you using a phrase and not just individual words. Here are few examples drawn from the above keyword list:

→ "academic achievement" AND "class size"

→ education AND children AND "parental involvement"

→ "teacher-student ratios" AND "public schools"

- Choosing Search Terms

- << Previous: 2. Choose Topic & Write Thesis Statement

- Next: 4. Research Your Topic >>

- Last Updated: Oct 31, 2023 9:15 AM

- URL: https://libguides.seminolestate.edu/researchpaper

- Research Guides

Literature Review: A Self-Guided Tutorial

Using concept maps.

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Peer Review

- Reading the Literature

- Developing Research Questions

- Considering Strong Opinions

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Super Searching

- Finding the Full Text

- Citation Searching This link opens in a new window

- When to stop searching

- Citation Management

- Annotating Articles Tip

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- How to Review the Literature

- Using a Synthesis Matrix

- 7. Write literature review

Concept maps or mind maps visually represent relationships of different concepts. In research, they can help you make connections between ideas. You can use them as you are formulating your research question, as you are reading a complex text, and when you are creating a literature review. See the video and examples below.

How to Create a Concept Map

Credit: Penn State Libraries ( CC-BY ) Run Time: 3:13

- Bubbl.us Free version allows 3 mind maps, image export, and sharing.

- MindMeister Free version allows 3 mind maps, sharing, collaborating, and importing. No image-based exporting.

Mind Map of a Text Example

Credit: Austin Kleon. A map I drew of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing in 2008. Tumblr post. April 14, 2016. http://tumblr.austinkleon.com/post/142802684061#notes

Literature Review Mind Map Example

This example shows the different aspects of the author's literature review with citations to scholars who have written about those aspects.

Credit: Clancy Ratliff, Dissertation: Literature Review. Culturecat: Rhetoric and Feminism [blog]. 2 October 2005. http://culturecat.net/node/955 .

- << Previous: Reading the Literature

- Next: 1. Identify the question >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.williams.edu/literature-review

Concept Mapping for Research Projects

Introduction

What is concept mapping in research, what is the purpose of concept mapping, examples of concept maps, how are concept maps used in research, benefits of a concept map, what is the concept mapping process.

Concept mapping is a straightforward yet powerful technique that offers a bird's eye view of scientific knowledge and connections between ideas. Through concept mapping, research can be systematically arranged to allow researchers to analyze complex topics, making it easier to see how different concepts relate to one another.

It transforms abstract thoughts into a clear, visual representation of scientific knowledge, acting as a practical tool for bridging brainstorming and detailed data analysis . Concept mapping is especially beneficial for uncovering relationships between concepts that may not be immediately obvious.

This article outlines what the concept mapping process entails, its purposes, and its advantages. It also provides a step-by-step guide on creating concept maps for your research project, supplemented with examples.

Concept mapping for qualitative studies is a valuable tool that allows researchers to visualize the relationships between different ideas, concepts, or pieces of information. It involves creating a diagram that showcases how various elements are interconnected, often revealing patterns, hierarchies, and associations that might not be evident through text alone. The map starts with a central idea or question and branches out to show how subsidiary ideas connect to it and to each other.

This technique is grounded in the cognitive sciences, reflecting how the brain organizes and structures knowledge. By mapping out concepts, researchers can more easily comprehend the scope of a project, identify gaps in knowledge, and determine the direction of their inquiry. It serves not just as a method for organizing thoughts but also as a tool for critical thinking and analysis.

In the context of research, concept mapping can be used at various stages of a project. Initially, it can help in formulating a research question or questions by visually exploring the key themes and variables involved. Throughout the research process, concept maps can be adapted and expanded to incorporate new findings and insights, making them dynamic tools for understanding and communication.

Moreover, concept mapping fosters collaboration among research team members, providing a shared visual language that can bridge disciplinary divides. It can visually present complex ideas, making discussions more productive and helping to align the team’s understanding and approach.

A concept map shows scientific knowledge in an organized manner. Moreover, it serves as a multifaceted tool designed to enhance comprehension, communication, and collaboration in research. At its core, concept mapping aims to clarify complex ideas and relationships, making abstract concepts more accessible and understandable. This clarity is achieved by visually representing ideas, which helps researchers and stakeholders alike grasp the breadth and depth of a project more intuitively.

One primary objective of concept mapping is to foster critical thinking and analytical skills regarding a particular research topic. By visually laying out the connections between concepts, researchers are encouraged to explore and question the nature of these relationships, potentially uncovering new insights or identifying underlying assumptions. This process promotes a more thorough examination of the subject matter, encouraging a deeper engagement with the material.

Furthermore, using concept maps can aid in the identification of gaps in knowledge. By organizing concepts visually, it becomes easier to spot areas that are underexplored or lacking in evidence. This can guide future research directions, ensuring that efforts are focused on filling these gaps and advancing understanding of the topic.

Another significant purpose of concept mapping is to enhance collaboration among researchers. By providing a clear and shared visual representation of a project’s structure, concept maps facilitate communication among team members, regardless of their disciplinary backgrounds. This shared understanding helps to align research efforts, streamline decision-making processes, and encourage collaborative problem-solving.

Concept maps are versatile tools that can be applied across diverse research areas to clarify complex ideas and foster deeper understanding. Below are conceptual examples from different domains, showcasing how concept maps can be tailored to specific research needs.

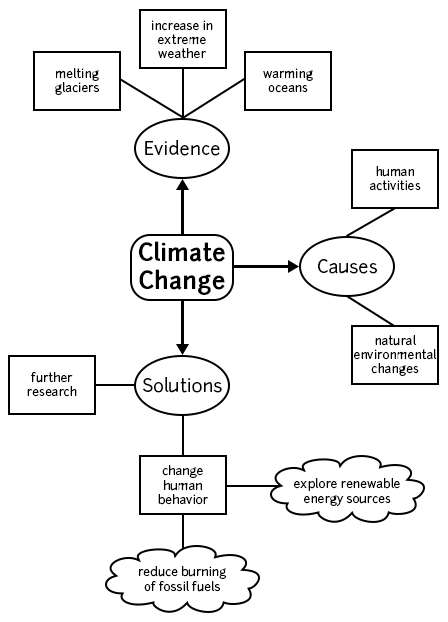

Environmental science

Imagine a study that employs mind mapping to focus on the impacts of climate change on coastal ecosystems. Researchers could use concept mapping to illustrate the intricate relationships between species, habitats, and environmental stressors. The map might center on "Coastal Ecosystems," branching out to related concepts like "Sea Level Rise," "Salinity Changes," and "Species Migration." This visual representation could help in understanding the multifaceted effects of climate change, guiding conservation efforts and policy development.

In exploring factors that influence student motivation, educational researchers might create a concept map to visualize connections between the classroom environment, teaching methods, and student engagement. Key elements such as "Active Learning," "Feedback," and "Classroom Climate" could be linked to impact "Student Motivation." This concept map could serve as a foundation for strategies to boost engagement and learning outcomes, demonstrating concept mapping's applicability in educational interventions.

Health sciences

For a study on Alzheimer's disease progression, a concept map could delineate complex pathways leading to neuronal degeneration. Featuring "Alzheimer's Disease" at its center, branches could extend to "Genetic Factors," "Environmental Influences," and "Biochemical Processes." This approach might identify potential therapeutic targets and help address health challenges.

Technology and business

Researching how small businesses adopt new technologies could involve a concept map exploring decision-making factors. The central theme "Technology Adoption" might connect to "Cost-Benefit Analysis," "Organizational Culture," "Market Trends," and "Regulatory Environment." This method could capture the multifaceted nature of technology adoption decisions, aiding in the development of supportive strategies for small businesses.

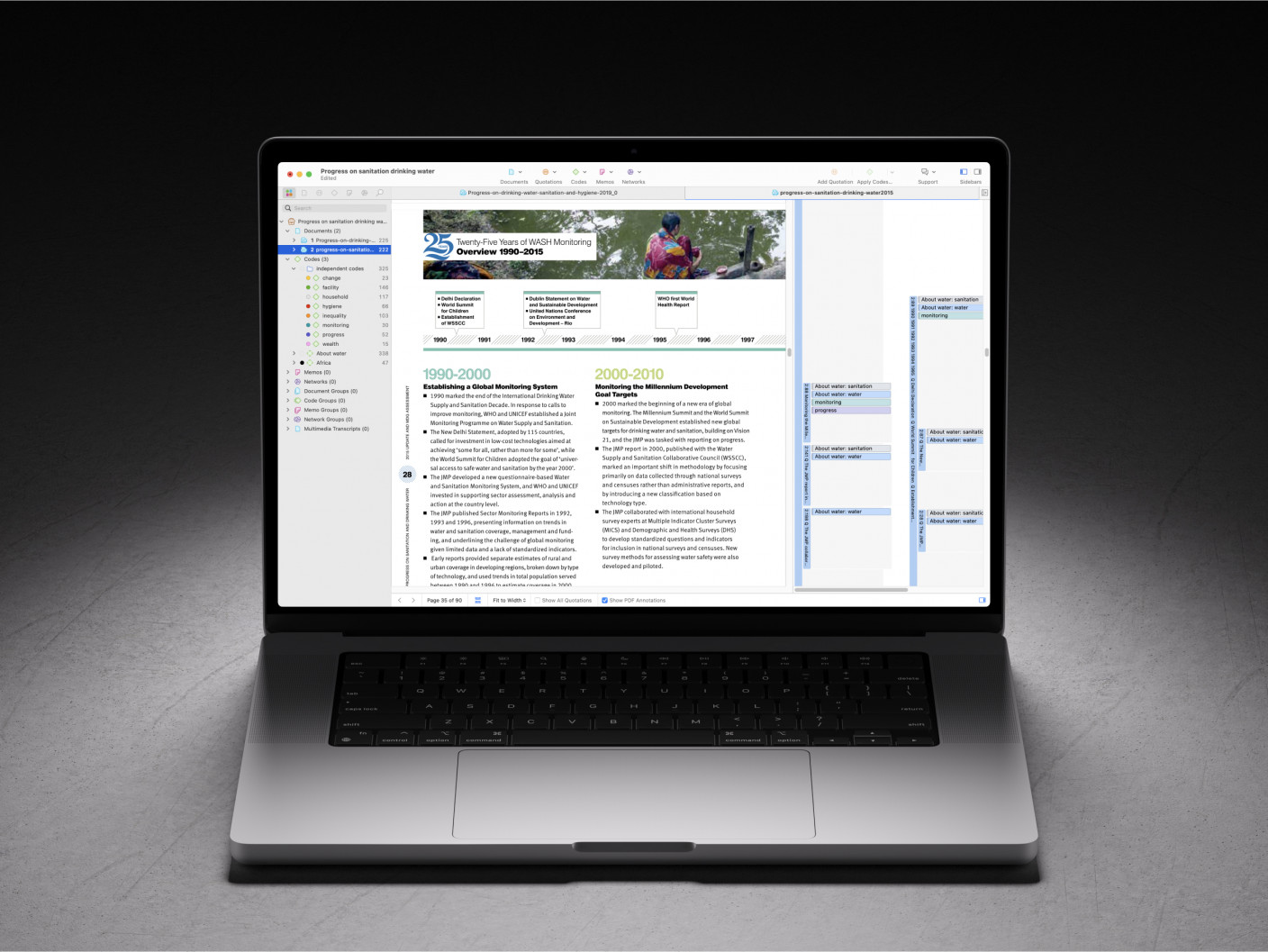

Visualize your research with ATLAS.ti

Powerful, intuitive tools bring your research project to life. Try out a free trial of ATLAS.ti today.

Concept maps are utilized in research to facilitate a range of critical activities, from the initial stages of project planning to the dissemination of research findings. Their use enhances the clarity, organization, and effectiveness of research efforts in several key ways.

At the outset of a research project, a concept map can help in defining the scope and objectives. Researchers can use a concept map to identify and visually represent the main themes and questions their project will address. This early visualization aids in pinpointing the focus areas and can highlight potential research questions or hypotheses that warrant further exploration.

Throughout the research process, concept maps serve as dynamic tools for organizing and synthesizing information. As new data is collected and analyzed, the concept map can be updated to reflect new insights, connections between concepts, and emerging patterns. This ongoing adjustment helps researchers maintain a clear overview of their project, ensuring that their data analysis remains structured and focused.

Concept maps also play a crucial role in identifying relationships between variables and in revealing gaps in existing knowledge. By laying out the known connections and highlighting areas with limited information, researchers can more easily identify where further investigation is needed, guiding the direction of subsequent research efforts.

In terms of collaboration and communication, concept maps are invaluable. They provide a visual language that can be shared among team members and stakeholders, facilitating discussions and ensuring that all parties have a common understanding of the project’s framework and findings.

Finally, when presenting research outcomes, concept maps can effectively summarize and convey complex information to diverse audiences. They can be used in reports, presentations, and publications to illustrate the study’s structure, findings, and implications clearly and concisely, making the research accessible to both academic and non-academic audiences.

Concept maps offer a range of benefits that enhance the research process, making complex information more manageable and comprehensible. These benefits can be broadly categorized into improving understanding, facilitating communication, and aiding in the planning and organization of research.

Enhancing understanding

Concept maps help distill complex ideas into visual formats, making abstract concepts more tangible. By laying out the relationships between different pieces of information, these maps enable researchers to see patterns and connections that might not be obvious in textual form. A concept map can lead to a deeper understanding of the subject matter, as it encourages the identification of relationships, hierarchies, and networks within the research topic.

Facilitating communication

One of the key advantages of concept maps is their ability to act as a communication tool among research team members and with external stakeholders. They provide a shared visual language that can help in explaining ideas clearly and succinctly, bridging knowledge gaps between individuals with different expertise or backgrounds. This common ground is especially valuable in multidisciplinary research teams, where understanding each others' perspectives is crucial for collaborative success. Moreover, concept maps can be effective in presentations or publications by conveying findings and theories in a more engaging and understandable way.

Aiding planning and organization

In the context of research planning and organization, concept maps serve as an invaluable tool for structuring projects and outlining research strategies. They allow researchers to visually map out the scope of their study, identify key components and variables, and organize their approach to data collection and analysis. This can support a more efficient use of resources and time, as potential overlaps or gaps in research can be identified early in the process. Furthermore, concept maps can be used to track progress over time, providing a clear overview of how individual pieces of research contribute to the overall project goals.

The process of creating a concept map involves several structured steps that guide researchers from the initial exploration of a topic to the development of a comprehensive visual display of their ideas and findings. This process can be divided into key phases: starting with a literature review , drafting an initial mind map, and refining the concept map into a final version.

Conducting a literature review

The first step to creating a concept map is to conduct a thorough literature review. This stage is crucial for gathering existing knowledge on the topic, identifying key concepts, theories, and relationships that have been previously established. The literature review helps in framing the main idea or question that will be at the center of the concept map. It provides a solid foundation of information from which researchers can begin to build their map, ensuring that it is grounded in established research and theory.

Drafting an initial map

With a clear understanding of the topic from the literature review, the next step is to start drafting an initial concept map. This can begin as a simple mind map, with the main idea at the center and primary concepts branching out from it. Researchers can then add layers of detail, linking related concepts and indicating the nature of their relationships. This initial draft is a flexible tool, allowing for easy adjustments as new ideas emerge or as the structure of the map evolves.

Refining the concept map

The last phase involves refining the initial draft into a final version of the concept map. This step may require multiple revisions, as researchers review their concept map for clarity, coherence, and completeness. It's an opportunity to ensure that all relevant concepts are included and accurately represented. The final version should clearly convey the main idea, its supporting concepts, and their interconnections. This polished concept map can then be used for various purposes, such as the basis for a research project, a visual aid in a blog post, or a tool for communication within a research team.

Turn ideas into insights with ATLAS.ti

ATLAS.ti assists you with the entire research process, from initial mind maps to findings. See how with a free trial.

The Ultimate Guide to Concept Maps: From Its Origin to Concept Map Best Practices

This concept map tutorial is to help you master the technique of using concept maps, whether it is for your education or for your business.

In this concept map guide, you will find insight into,

What is a Concept Map?

Origin of concept maps.

- The Characteristics of a Concept Map

How to Draw a Concept Map

- How Do You Fine-tune a Concept Map

- Concept Map Templates

Uses of Concept Maps

- What are Some Common Mistakes to Avoid When Creating a Concept Map

- Concept Map Best Practices

Concept maps are a graphical tool that is used to visualize meaningful relationships among concepts. It’s used as a knowledge representation tool, meaning they basically represent the knowledge structure that we humans store in our minds about a certain topic.

Both simple and complex concept maps consist of two things: concepts and relationships among them.

Concept maps were the outcome of a research done in the 1970s at Cornell University by Joseph Novak – an American Educator and Research Scientist – and his research team.

In order to study how children understand basic science concepts, they studied and interviewed many children. However, they found it difficult to identify the changes in the ways children understood science concepts with the detailed interview transcripts alone.

The need to find a better solution to represent children’s conceptual understanding led to the development of the concept map in 1972.

Since then it has been used extensively not only in the fields of education and research but also in business.

The Key Characteristics of a Concept Map

Not all diagrams that have words/ phrases inside nodes are concept maps. Concept maps have specific characteristics that distinguish themselves from other diagrams that are used to represent knowledge. And they are,

Nodes are the circles or the boxes that are used to represent a concept or an idea. These may vary in size, according to their hierarchy on the map; for example, more general nodes at the top of the map may be bigger than the more specific nodes that follow them.

Cross-Links

Concept maps consist of concepts in different domains. And the relationships between these different domains of knowledge are shown with cross-links.

Linking Words

Or linking phrases if it contains more than a word. These describe the type of relationship between the two concepts and appear on the line connecting them.

Hierarchical Structure

Usually, concept maps are organized hierarchically. This means the most general and inclusive concepts are placed at the top of the map. Those that are more specific are positioned below them. Accordingly, hierarchical concept maps are read from top to bottom.

However, the structure of a concept map is not limited to this structure, it could take a free-form approach too – starting from the center and spreading outwards.

Propositional Structure

A concept map illustrates a set of meaningful propositions about a topic.

Every two concepts (in some cases more than two,) along with the linking phrases, form a meaningful sentence, otherwise known as a proposition.

Focus Question

Generally, a concept map should be woven around a focus question, which is the problem or the issue the concept map seeks to resolve. The better the focus question, the richer the concept map will be.

Underlying Theory

Concept maps are based on Ausubel’s Assimilation theory . This is built around the fact that new knowledge can be learned effectively by linking it to what is already known. Concept maps are seen as a methodological tool of this theory.

Generate new ideas and add structure to your thoughts with concept maps. Explore connections between concepts to better understand them with Creately.

Create a Concept Map

You can either draw a concept map on a piece of paper or on a concept mapping software. Either way, stick to the following steps when you are drawing one.

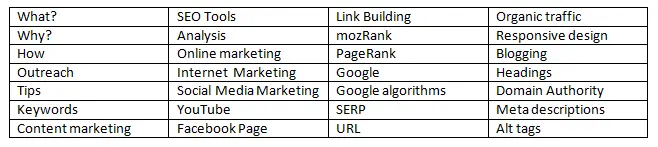

Step 1: Pick a Topic

The first step is to identify a topic you need to study with your concept map. This could be an idea, a question or an issue.

For example, let’s say you are interested in SEO or Search Engine Optimization.

Step 2: Do a Quick Brainstorm

What are the facts, ideas, concepts, themes, queries etc. that come to your mind when you think about this topic? Note these down as you brainstorm around the topic you have selected. Remember to keep these as concise as possible.

Step 3: Start to Draw the Map

It’s recommended to start a concept map from the top and develop it downward, although you can put down your topic at the center and expand it outwards. Either way make sure that the central topic stands out from the rest (use a bigger node, a different color etc.).

Step 4: Connect the Concepts

Now it’s time to connect what you have brainstormed to the central topic and to each other. Remember, the more important the idea, the closer it should be to the top or the center.

As you identify these connections put down the linking words or phrases to indicate the relationship between the two concepts you are linking.

Once the direct connections between concepts have been identified, look for crosslinks that link together concepts from different areas or domains.

Step 5: Anything Missing?

Scrutinize what you have created to make sure that you haven’t missed anything and that the relationships you have identified make sense.

How Do You Fine-tune a Concept Map?

Fine-tuning the concept map is a crucial step when effectively visualizing complex information. Below are some key pointers to follow.

- Begin by reviewing the entire map to identify areas needing improvement or some adjustments.

- Refine the central idea, if necessary, to ensure that the central idea accurately represents the main topic of the concept map.

- If there are long labels, simplify them using specific or descriptive keywords that represent the concept or idea of the map. This will help to reflect the content of each node accurately.

- Evaluate whether any nodes should be added or removed depending on their relevance and redundancy. Look to see if any additional concepts or ideas should be included.

- Review the connections to ensure they correctly represent the relationships between the concepts. If necessary, add or remove connections or adjust the placement of nodes to reflect the connections better.

- Test the map! Test the map with others for feedback, especially on its accuracy and effectiveness.

Editable Concept Map Examples and Templates

Here are some concept map diagram templates you can edit right away on Creately. Click the image to open it in the editor. Make changes according to your needs and export them as images, PNG, PDF, or JPEG.

Concept Map Example 1

Concept Map Example 2

Concept Map Example 3

Concept Map Example 4

Concept Map Example 5

Concept Map Example 6

Concept Map Example 7

Although first introduced to the field of education, concept maps have gained popularity across a number of other fields over the last few decades.

Concept Maps in Education

In the field of education, concept maps are used as both a learning tool and an evaluation tool to assess student learning.

- Foster meaningful learning by helping create connections between what students already know and new knowledge they acquire

- Organize knowledge around a subject for quick analysis

- Assess students’ understanding to see where their knowledge needs improvement

- Conduct effective brainstorming around a topic

- Present complex concepts in an easily digestible way

- Organize instructional material for courses or curricula

- Can be used as a basis for discussion among students

- Help identify valid and invalid ideas held by students

- Help promote creative and critical thinking among students

- Can be used as an alternative to traditional note-taking and writing assignments

Concept Maps in Business

By design, concept maps are apt for business analysis. In the field of business, concept maps are popularly used to preserve, generate and share knowledge.

- To facilitate team brainstorming sessions to come up with new strategies, new business concepts etc.

- Support creative and result-oriented approach towards business development

- Can be used as a systematic way to share expert business ideas, insights etc. with others

- Help with planning and drafting business documents, business presentations etc.

Concept Maps in Qualitative Research

Concept maps in qualitative research are used as a methodical research strategy.

- Can be used to plan a research project

- Can help reduce voluminous text-based data into a manageable form without losing the meaning

- Identify interconnections between concepts in a study and analyze themes

- Analyze the information provided by interviewees in a study; help the researcher maintain the meaning of the interview

- Present findings in an effective way

What are Some Common Mistakes to Avoid when Creating a Concept Map

When creating your concept map, avoid the below common mistakes that will undermine the map’s effectiveness.

- Overcomplicating. This will make the map too complex or difficult to understand.

- Focusing too much on the details. Getting bogged down with too many details will derail you from the main focus with too much irrelevant and unnecessary information.

- Not using a hierarchy. Without a hierarchy, the concept map will be too complicated to follow and disorganized.

- Not using consistent formatting. It will be difficult to read or understand without consistent formatting and symbols throughout the map, leading to confusion and misunderstandings.

- Being too rigid by not making changes as and when necessary to reflect new information or insights.

- Not testing the map for effectiveness to help identify areas that may need further improvement.

Concept Mapping Best Practices

Start with a clear central idea.

Begin the concept map with a clear yet concise central idea representing the main topic or theme. The central idea should be easily understood, and it should also be the focal point of the map.

Stick with the Hierarchical Structure

Concept maps organized according to the hierarchical structure are easier to read. As the most general concepts go at the top and the more specific ones coming below them, it can easily be read from top to bottom.

Keep a Single Root Concept

A concept map can have two root concepts, but limiting it to one helps the learner easily identify how concepts are constructed. On the other hand, having two root concepts may make it confusing.

Use Meaningful Keywords

Use meaningful and specific keywords to label the concepts. The labels should be descriptive and accurately represent the content of each node.

Color Code Your Concept Maps

Colors help distinguish concepts in different domains immediately. This does not only make it easier to read the map but when it comes to recalling information, color coding plays a vital role.

Add Visual Cues to the Map

Add visual cues such as symbols and images if necessary to highlight important information and to make the concept map more engaging and visually appealing.

Connect Related Ideas

Add visual cues such as symbols and images to highlight important information and make the concept map more engaging and visually appealing.

Make Sure Linking Phrases Make Sense

Two concepts and a linking phrase should make a meaningful sentence. This could be a word, phrase or sometimes even a symbol such as + or %. In any case, make sure that your concept map reads well.

Be Consistent

Use consistent formatting, symbols, and color codes throughout the concept map to make it easier to read and understand.

Always Base Your Concept Map on a Focus Question

Having one single question to answer will help you better structure your concept map and keep yourself from deviating from your focus.

Keep it Simple

If possible, avoid using complex sentences or too much text. Instead, use simple phrases or keywords to communicate the main ideas and connections.

Link to Further Resources

If you are drawing your concept maps with a concept mapping software, you have the ability to make it more resourceful. When mentioning concepts, you can add active links to your concept maps allowing the reader to study the idea more thoroughly.

Review and Revise

One thing to remember is that concept maps can be changed and updated regularly as needed. This will help to refine your ideas and to identify new connections between concepts.

Feed Back on the Comprehensive Concept Map Tutorial

In this concept map tutorial we have covered, everything – whether you are a stranger to concept mapping or have used it before – you should know when it comes to concept map diagrams. If you are ready to go ahead and draw your concept map, start with the Creately Concept Map Maker .

And don’t forget to leave your feedback!

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

FAQs About Concept Maps

More related articles.

Amanda Athuraliya is the communication specialist/content writer at Creately, online diagramming and collaboration tool. She is an avid reader, a budding writer and a passionate researcher who loves to write about all kinds of topics.

How to Make Research Concept Map: Explain with Examples

If you’re on a research team and want to organize and illustrate what you know about a topic, creating a research concept map is a smart way to go. It’s a technique for brainstorming research topics or narrowing down a broad notion into a more focused one. Concept maps can also be used to assist you to establish keywords for database searching or to help you come up with a thesis statement for your assignment. Keep reading to learn more about this great technique as well as the procedures for making one.

How to Make Research Concept Map?

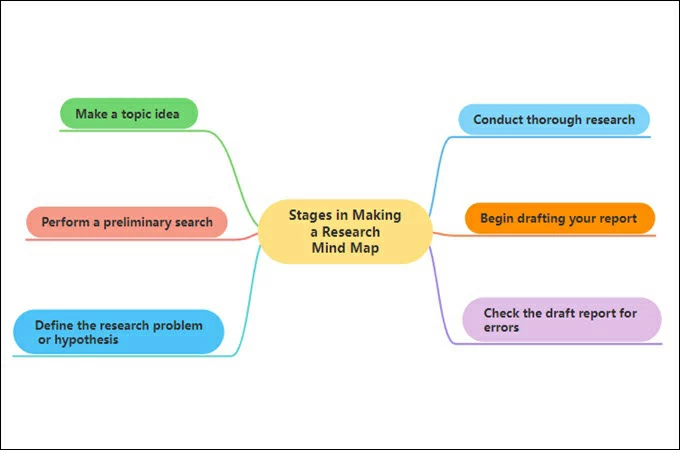

What is a concept map, stages in making a research mind map, how to create research concept map online, importance of utilizing a concept map.

A mind map about research is a visual representation of your understanding of a subject. Concept maps help in the organization of your thoughts and the exploration of relationships within a topic. To organize and illustrate what you know about a topic, make an idea map. They essentially represent the knowledge that we people hold in our minds regarding a certain subject.

Make a topic idea – Determine your research mind map topic area by considering what you may possibly research in this area.

Perform a preliminary search – You must now determine whether you have sufficient resources to complete your investigation. Are those resources readily available? Is your topic too broad or too narrow?

Define the research problem or hypothesis – You should be able to establish the boundaries of your research now that you’ve done some preliminary investigation. Consider phrasing your research question as just a question to aid you in writing.

Conduct thorough research – According to a concept map regarding research, Conducting thorough research is one of the recognized resources for the problem or topic.

Begin drafting your report – Start your initial draft with the principal purpose of your report if you’ve described it. If not, submit a one-sentence summary that answers the following question: What is your report’s story?.

Check the draft report for errors -Finally, the report is updated and double-checked at this stage, and research mind map example diagrams and other visual aids are added.

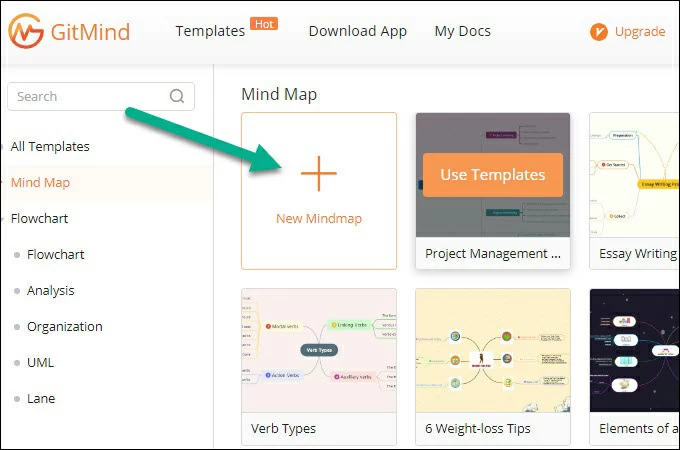

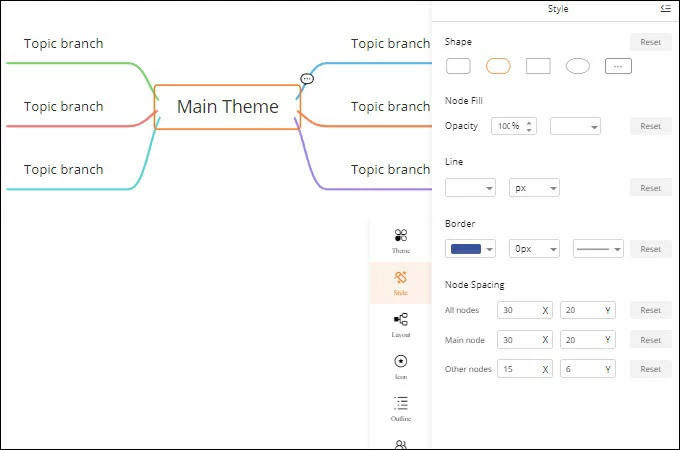

Create professional-looking mind maps with GitMind . This tool is an online brainstorming and graphic design tool that allows users to easily build visualizations such as research concept map models, flowcharts, and other graphic representations. Additionally, this program provides free editing options while also allowing users to send their outputs by URL and edit them wherever they are. Having stated that, the detailed processes for creating a research concept map utilizing this program are provided below.

- First, go to GitMind’s official website and click the “Get Started” button to start.

- Choose the “Mindmap” tab and hit the “New Mindmap” button to start making a mindmap.

- From there, you can start customizing your concept map for research.

- Once done, click the “Save” button to save the modification, also if you can share your outputs via the URL link by simply hitting the “Share” button.

Both speakers and people learning new material might benefit from concept mapping. People can frequently absorb ideas far more rapidly with a research mind map than they can by reading them inside an article or book. This visual way of presenting information that makes it quickly understandable. Because of its simplicity and highlighting of crucial aspects, people can easily read thru a conceptual framework for quick comprehension of the complete system. This can be incredibly useful in a variety of situations, such as a work event when attendees must quickly examine the benefits of new initiatives.

All in all, concept mapping can truly help the organization of a presentation in a logical manner. Visualizations are logical by nature and emphasize clarity as well as order. Presenters are guided to create brief, logical presentations by forcing this structure on them. Even if the user isn’t presenting the research concept map during the presentation, a presenter may build a concept map as a way of arranging his presentation notes. Furthermore, software such as GitMind makes constructing a concept map much easier.

Related posts:

- Best 8 Free Online UML diagram tools in 2024

- What is A Probability Tree Diagram and Real Life Uses

Leave a Comment

Comment (0).

This website uses cookies that are essential for the operations of this website and its core functions. Other cookies will only be placed with your consent. For more details visit our Cookies Policy .

AC1 Research Paper

- Choose a Topic

- Reference Sources

- Concept Mapping

- The Research Question

- Secondary Sources

- Primary Sources

- Noodletools Help

Schedule a Research Meeting

- More Information

- Virtual Mapping

- Concept Mapping (BYU)

- Concept Maps (UNC)

- How to make a Concept Map

- Learn about Concept Maps

- Mind Meister

Step 1: Go to Noodletools sign in

Step 2: Click on Google under Sign In/Register

Step 3: Sign in with your Hopkins email

- Citation Help: How to Cite All Calarco Sources

- How to Cite Books in Noodletools

- How to Cite Images in Noodletools

- How to Cite Websites in Noodletools

- Schedule a Research Meeting Need individualized research help? Sign up now!

What is a Concept Map?

A concept map helps you organize what you know about your topic. It is a lot like brainstorming because it helps to get information out of our heads and challenges us to identify important concepts and ideas. However, unlike brainstorming, concept mapping asks us to define how these essential components relate to each other. It results in maps that are structured and complex, but also more informative.

Your map will include key events, people, places, time periods, and ideas, as well as their relationships to one another. All concepts are linked together with words or phrases that define the relationship. Make a concept map to:

- see connections between ideas

- narrow your topic

- generate questions to guide your research

- << Previous: Reference Sources

- Next: The Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 9:31 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hopkins.edu/ac1

Introduction to Academic Reading and Writing: Concept Map

- Concept Map

- Select a Topic

- Develop a Research Question

- Identify Sources

- Thesis Statements

- Effective Paragraphs

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Quote, Paraphrase, Summarize

- Synthesize Sources

- MLA and APA

- Transitions

- Eliminate Wordiness

- Grammar and Style

- Resource Videos

Concept Maps

Create a concept map using your annotations and highlights of the text .

Define your map’s focus question and topic. Your focus question guides your map in a certain direction. What is the purpose of what you read? Your topic is what you are reading about.

Create a list of relevant concepts, thoughts and implications of your topic as you read. , think about the relationships between these concepts and begin to organize the list of concepts from broad to specific. you can set a topic at the center, with supporting points and details branching outwards, or you can create a hierarchy, with the topic at the top and its components below. , add links and cros s -links between related concepts and label these links with words or phrases to clarify the relationship between concepts., color code, add symbols, and personalize to your map so that is meaningful to you..

Check out these free online Concept Mapping tools:

- Lucid Chart

Video by McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph, 2017 .

Concept Map Example

Map by Penn State University , Concept Maps iStudy Tutorial

- << Previous: Annotate

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 12:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lbc.edu/Introtoacademicreadingandwriting

- Spartanburg Community College Library

- SCC Research Guides

- Choosing a Research Topic

- 1. Concept Mapping

Concept Mapping

A concept map (also called a mind map) is a tool that you can use to help brainstorm a research topic or help you narrow down a general idea into a more focused idea. Concept maps can also be used to help you come up with a thesis statement for your assignment or to help you develop keywords that you can use in your database searching.

Concept maps also help you see connections between some of your ideas and show you how many different directions you can take your research based on a single idea.

How to create a Concept Map

The great thing about concept maps is that they can look however you'd like and can be done either on a piece of paper or even done online. Some free online concept mapping tools are MindMup , Creately , and Lucidchart , although there are many other tools available.

Start with your main idea in the center of your map. Then to start building out your map, use the 5Ws + How (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How) to start thinking about related concepts. For example, why is this topic so important? Who is influenced by your topic? Where did your topic take place?

Example Concept Map

The general topic of your paper, the All Community Colleges Should be Tuition Free goes in the center of your page.

Using the 5Ws + How, you have built out a concept map, to give you a better sense of which directions your paper can go. For example, based on your concept map, you might decide to narrow down your topic to who is impacted by community colleges being tuition free or how free tuition makes education more accessible.

- Community members

- Strengthens the workforce.

- Makes education more accessible.

- Current issue.

- Spartanburg Community College

- More community members have the ability to go to college.

- Free tuition helps ease the financial burden of going to college.

- State funding.

Helpful Resources

- Concept Mapping Handout This printable handout can help you get started on a concept map.

- << Previous: What Makes a Good Research Topic?

- Next: 2. Background Research >>

- What Makes a Good Research Topic?

- 2. Background Research

- 3. Narrow Your Topic / Thesis Statements

Questions? Ask a Librarian

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 9:31 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sccsc.edu/chooseatopic

Giles Campus | 864.592.4764 | Toll Free 866.542.2779 | Contact Us

Copyright © 2024 Spartanburg Community College. All rights reserved.

Info for Library Staff | Guide Search

Return to SCC Website

Concept Mapping

- What is Concept Mapping?

- Concept Mapping Tools

- Concept Mapping How-to

- More Resources

Introduction

What is concept mapping .

Concept mapping is a useful tool/skill that can be applied to the research process

"Concept maps are graphical tools for organizing and representing knowledge. They include concepts, usually enclosed in circles or boxes of some type, and relationships between concepts indicated by a connecting line linking two concepts. Words on the line, referred to as linking words or linking phrases, specify the relationship between the two concepts."

Concept Map Example

The above concept map examples are from a paper by Novac & Canas (2008) on how to construct concept maps and the theory underlying them. The below example is from professor Vandana Singh from the Physics and Earth Sciences department at Framingham State University.

Novak, J. D., & Canas, A. J. (2008). The Theory Underlying Concept Maps and How to Construct and Use them (p. 36). Pensacola, FL: Institute for Human and Machine Cognition. Retrieved from http://cmap.ihmc.us/docs/theory-of-concept-maps

- Next: Concept Mapping Tools >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 4:24 PM

- URL: https://libguides.framingham.edu/conceptmapping

Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health pp 1–25 Cite as

Concept Mapping Method

- Sharanya Napier-Raman 2 ,

- Scott Rosas 3 ,

- Syeda Zakia Hossain 2 ,

- Elias Mpofu 2 , 4 , 5 ,

- Mi-Joung Lee 2 ,

- Pranee Liamputtong 6 ,

- Tinashe Dune 7 &

- Virginia Mapedzahama 7

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 28 January 2023

75 Accesses

This chapter introduces group concept mapping and illustrates the merit of this methodology for global public health research. Group concept mapping is a mixed-methods participatory research approach that integrates qualitative conceptual data and rigorous multivariate statistical analysis, transforming abstract conceptual data into visual representations or “maps.” The participatory nature of group concept mapping as well as its fully integrated mixed-methodology makes it a particularly useful methodology for public health research. Group concept mapping is a collaborative group process that seeks to build consensus between disparate perspectives within a group. It provides researchers with actionable, participant-determined research outcomes. Group concept mapping has been applied in social research across a range of disciplines, including public health, yet remains underutilized by health researchers. This chapter offers a guide for conducting the methodology, detailing the six key steps in group concept mapping: planning, generation, structuring, analysis, interpretation, and utilization. To illustrate group concept mapping in action, the chapter presents a case study using this methodology to examine the sexual and reproductive health decision-making of migrant and refugee youth in Australia. This case study provides evidence of the utility of group concept mapping for examining the complex social issues of public health research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

See Napier-Raman et al. for further details on this study and research findings (forthcoming).

Ahmad F, Mahmood S, Pietkiewicz I, McDonald L, Ginsburg O (2011) Concept mapping with South Asian immigrant women: barriers to mammography and solutions. J Immigr Minor Health 14(2):242–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-011-9472-7

Article Google Scholar

Albert SM, Burke JG (2014) Methods for community public health research: integrated and engaged approaches. Springer Publishing Company, New York

Google Scholar

Anderson LA, Slonim A (2017) Perspectives on the strategic uses of concept mapping to address public health challenges. Eval Program Plann 60:194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.011

Barth MC (2004) A low-cost, post hoc method to rate overall site quality in a multi-site demonstration. Am J Eval 25(1):79–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400402500106

Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D (2006) Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health (1979) 60(10):854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662

Berg S, Cloutier LM, Bröring S (2018) Collective stakeholder representations and perceptions of drivers of novel biomass-based value chains. J Clean Prod 200:231–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.304

Burke JG, O’Campo P, Peak GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WMK (2005) An introduction to concept mapping as a participatory public health research method. Qual Health Res 15(10):1392–1410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305278876

Corcoran K (2005) The Oregon mental health referral checklists: concept mapping the mental health needs of youth in the juvenile justice system. Brief Treat Crisis Interv 5(1):9–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi003

Cossette P (2002) Analysing the thinking of F.W. Taylor using cognitive mapping. Manag Decis 40(2):168–182. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740210422848

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2018) Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks

Davies M (2011) Concept mapping, mind mapping and argument mapping: what are the differences and do they matter? High Educ 62(3):279–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9387-6

Davis MV, Cilenti D, Gunther-Mohr C, Baker EL (2012) On linkages; participatory research partnerships: addressing relevant public health system challenges. Public Health Rep (1974) 127(2):230–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491212700214

Halberg SE, Visek AJ, Blake EF, Essel KD, Sacheck J, Sylvetsky AC (2021) SODA MAPS: a framework for understanding caffeinated sugary drink consumption among children. Front Nutr 8:640531. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.640531

Hanson WE, Creswell JW, Clark VL, Petska KS, Creswell JD (2005) Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol 52:224–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.224

Haymovitz E, Houseal-Allport P, Lee RS, Svistova J (2018) Exploring the perceived benefits and limitations of a school-based social–emotional learning program: a concept map evaluation. Child Sch 40(1):45–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx029

Hesse-Biber SN (2015) Introduction: navigating a turbulent research landscape: working the boundaries, tensions, diversity, and contradictions of multimethod and mixed methods inquiry. In: Hesse-Biber SN, Johnson RB (eds) The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Chapter Google Scholar

Howlett M (2022) Looking at the ‘field’ through a Zoom lens: methodological reflections on conducting online research during a global pandemic. Qual Res: QR 22(3):387–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120985691

Hydeman JA, Uwazurike OC, Adeyemi EI, Beaupin LK (2019) Survivorship needs of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: a concept mapping analysis. J Cancer Surviv 13(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0725-5

IBM Corp (2020) IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 27.0). IBM Corp, Armonk

Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA (2012) Introduction to methods for CBPR for health. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA (eds) Methods for community-based participatory research for health. Wiley, Somerset

Kane M, Rosas S (2018) Conversations about group concept mapping: applications, examples, and enhancements. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Book Google Scholar

Kane M, Trochim WMK (2007) Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Kane M, Trochim WM (2009) Concept mapping for applied social research. In: Rog D, Bickman L (eds) The SAGE handbook of applied social research methods, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, pp 435–474

Keita AD, Whittaker S, Wynter J, Kidanu TW, Chhay C, Cardel M, Gans KM (2016) Applying concept mapping methodology to identify the perceptions of risk and protective factors for childhood obesity among Southeast Asian refugees. J Health Care Poor Underserved 27(4):1909–1933. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0171

Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ (2007) A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual Quant 43(2):265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

Liamputtong P (2020) Qualitative research methods, 5th edn. Oxford University Press, South Melbourne

Liamputtong P, Rice ZS (2022) The science of words and the science of numbers: research methods in health. In: Liamputtong P (ed) Research methods and evidence-based practice, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Docklands, pp 16–35

Macdiarmid JI, Loe J, Douglas F, Ludbrook A, Comerford C, McNeill G (2010) Concept mapping: an approach for developing an evaluation framework and realistic outcome indicators for community-based nutrition interventions. Proc Nutr Soc 69(OCE1). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665109993053

Mackworth-Young CRS, Mavodza C, Nyamwanza R, Tshuma M, Nzombe P, Chikwari C.D, Bernays S (2022) “Other risks don’t stop”: adapting a youth sexual and reproductive health intervention in Zimbabwe during COVID-19. Sex Reprod Health Matters 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2022.2029338

Maheen H, Chalmers K, Khaw S, McMichael C (2021) Sexual and reproductive health service utilisation of adolescents and young people from migrant and refugee backgrounds in high-income settings: a qualitative evidence synthesis (QES). Sex Health 18(4):283–293. https://doi.org/10.1071/sh20112

McBride KA, MacMillan F, George ES, Steiner GZ (2019) The use of mixed methods in research. In: Liamputtong P (ed) Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp 695–713

McFall SL, Ureda J, Byrd TL, Valdes A, Morales P, Scott DB et al (2008) What is needed for informed decisions about prostate cancer screening: perspectives of African-American and Hispanic men. Health Educ Res 24(2):280–291. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn018

Mengesha ZB, Dune T, Perz J (2016) Culturally and linguistically diverse women's views and experiences of accessing sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: a systematic review. Sex Health 13(4):299–310. https://doi.org/10.1071/sh15235

Minh A, Patel S, Bruce-Barrett C, OʼCampo P (2015) Letting youths choose for themselves: concept mapping as a participatory approach for program and service planning. Fam Community Health 38(1):33–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000060

Minkler M, Wallerstein N (2008) Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes, 2nd edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Novak JD, Cañas AJ (2011) Applying educational tools and ideas in the corporate world. In: Moon B, Hoffman RR, Novak JD, Cañas AJ (eds) Applied concept mapping: capturing, analyzing, and organizing knowledge. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Novak JD, Gowin BD, Johansen GT (1983) The use of concept mapping and knowledge vee mapping with junior high school science students. Sci Educ 67(5):625–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730670511

Olson BD, Jason LA (2015) Participatory mixed methods research. In: Hesse-Biber SN, Johnson RB (eds) The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Rosas SR (2012) The utility of concept mapping for actualizing participatory research. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología 12(2):7–24

Rosas SR (2016) Group concept mapping methodology: toward an epistemology of group conceptualization, complexity, and emergence. Qual Quant 51(3):1403–1416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0340-3

Rosas SR, Kane M (2012) Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plann 35(2):236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003

Surowiecki J (2005) The wisdom of crowds. Anchor Books, New York

Teddlie C, Tashakkori A (2010) Overview of contemporary issues in mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C (eds) SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks

The Concept System® (2022) groupwisdom™. In (Build 2021.24.01 ed., pp. Web-based platform). Ithaca, NY

Trochim WMK (1989) An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann 12(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5

Trochim WMK (2017) Hindsight is 20/20: reflections on the evolution of concept mapping. Eval Program Plann 60:176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.009

Trochim WMK, Kane M (2005) Concept mapping: an introduction to structured conceptualization in health care. Int J Qual Health Care 17(3):187–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzi038

Trochim WMK, Linton R (1986) Conceptualization for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann 9(4):289–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(86)90044-3

Article CAS Google Scholar

Trochim WMK, Milstein B, Wood BJ, Jackson S, Pressler V (2004) Setting objectives for community and systems change: an application of concept mapping for planning a statewide health improvement initiative. Health Promot Pract 5(1):8–19; discussion 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839903258020

Vaughn LM, Jones JR, Booth E, Burke JG (2017) Concept mapping methodology and community-engaged research: a perfect pairing. Eval Program Plann 60:229–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.08.013

Villa-Torres L, Svanemyr J (2015) Ensuring youth’s right to participation and promotion of youth leadership in the development of sexual and reproductive health policies and programs. J Adolesc Health 56(1):S51–S57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.022

Walker RE, Jones JR, Burke JG (2014) Concept mapping for community perceptions. In: Burke JG, Albert S (eds) Methods for community public health research: integrated and engaged approaches. Springer Publishing Company, New York

Wallerstein N, Duran B (2010) Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health 100:S40–S46

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sydney School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Sharanya Napier-Raman, Syeda Zakia Hossain, Elias Mpofu & Mi-Joung Lee

Concept Systems, Inc., Ithaca, NY, USA

Scott Rosas

Rehabilitation and Health Services, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

Elias Mpofu

School of Human and Community Development, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

College of Health Sciences, VinUniversity, Gia Lam District, Hanoi, Vietnam

Pranee Liamputtong

Transnational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Tinashe Dune & Virginia Mapedzahama

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sharanya Napier-Raman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Health Sciences, Western Sydney University, Camberwell, VIC, Australia

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Napier-Raman, S. et al. (2023). Concept Mapping Method. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96778-9_63-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96778-9_63-1

Received : 21 August 2022

Accepted : 22 August 2022

Published : 28 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-96778-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-96778-9

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Concept Maps

What are concept maps.

Concept maps are visual representations of information. They can take the form of charts, graphic organizers, tables, flowcharts, Venn Diagrams, timelines, or T-charts. Concept maps are especially useful for students who learn better visually, although they can benefit any type of learner. They are a powerful study strategy because they help you see the big picture: by starting with higher-level concepts, concept maps help you chunk information based on meaningful connections. In other words, knowing the big picture makes details more significant and easier to remember.

Concept maps work very well for classes or content that have visual elements or in times when it is important to see and understand relationships between different things. They can also be used to analyze information and compare and contrast.

Making and using concept maps

Making one is simple. There is no right or wrong way to make a concept map. The one key step is to focus on the ways ideas are linked to each other. For a few ideas on how to get started, take out a sheet of paper and try following the steps below:

- Identify a concept.

- From memory, try creating a graphic organizer related to this concept. Starting from memory is an excellent way to assess what you already understand and what you need to review.

- Go through lecture notes, readings and any other resources you have to fill in any gaps.

- Focus on how concepts are related to each other.

Your completed concept map is a great study tool. Try the following steps when studying:

- Elaborate (out loud or in writing) each part of the map.

- List related examples, where applicable, for sections of the map.

- Re-create your concept map without looking at the original, talking through each section as you do.

Examples of concept maps

Example 1 : This example illustrates the similarities and differences between two ideas, such as Series and Parallel Circuits. Notice the similarities are in the intersection of the 2 circles.

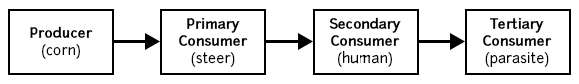

Example 2 : This example illustrates the relationship between ideas that are part of a process, such as a Food Chain.

Example 3 : This example illustrates the relationship between a main idea, such as climate change, and supporting details.

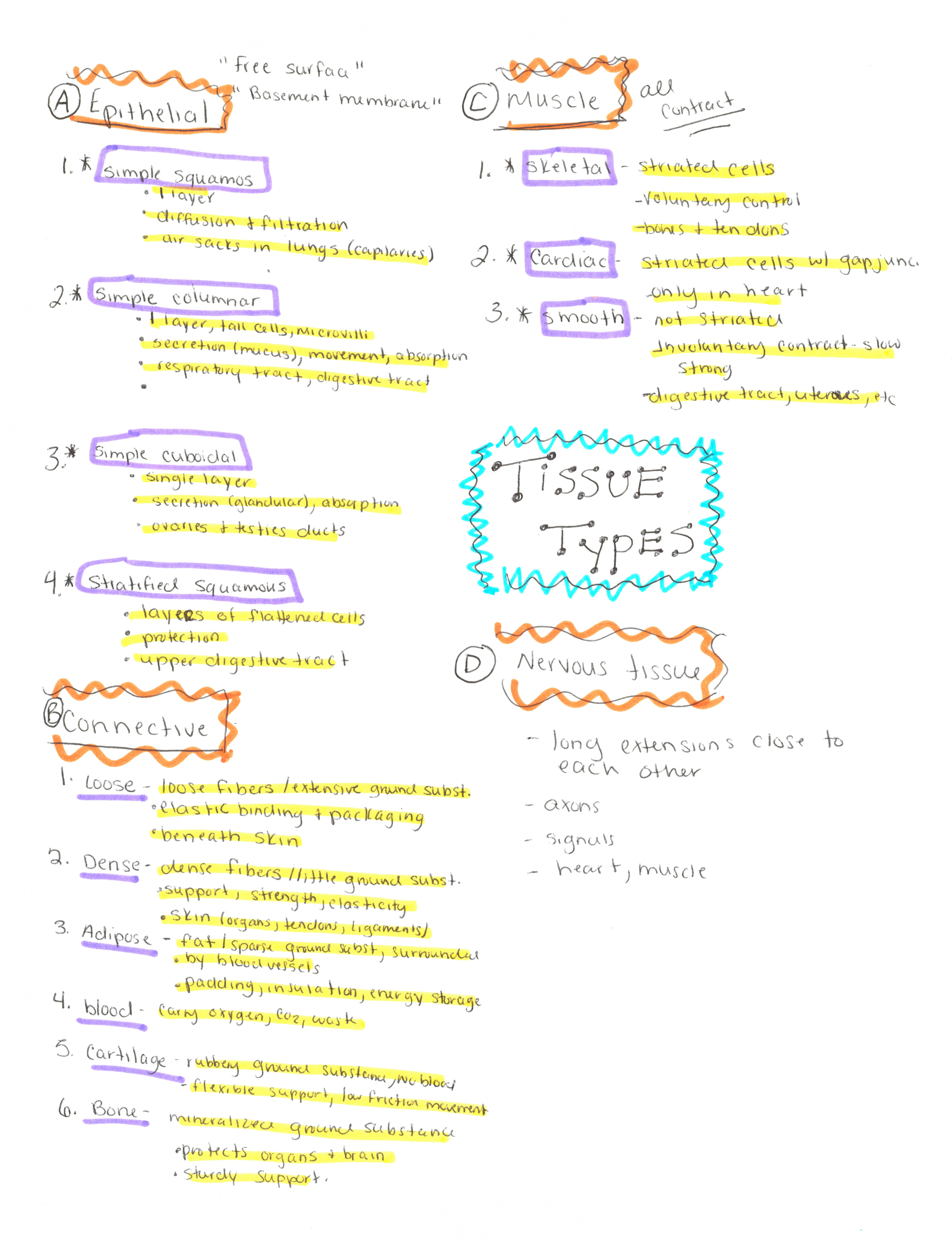

Example 4 : Outlining is a less visual form of concept mapping, but it might be the one you’re most familiar with. Outlining by starting with high-level course concepts and then drilling down to fill in details is a great way to determine what you know (and what you don’t know) when you’re studying. Creating an outline to start your studying will allow you to assess your knowledge base and figure out what gaps you need to fill in. You can type your outline or create a handwritten, color-coded one as seen in Example 5.

Additional study strategies

A concept map is one tool that you can use to study effectively, but there are many other effective study strategies. Check out these resources and experiment with a few other strategies to pair with concept mapping.

- Study Smarter, Not Harder

- Higher Order Thinking

- Metacognitive Study Strategies

- Studying with Classmates

- Reading Comprehension Tips

Make an appointment with an academic coach to practice using concept maps, make a study plan, or discuss any academic issue.

Attend a workshop on study strategies to learn about more options, get some practice, and talk with a coach.

How can technology help?

You can create virtual concept maps using applications like Mindomo , TheBrain , and Miro . You may be interested in features that allow you to:

- Connect links, embed documents and media, and integrate notes into your concept maps

- Search across maps for keywords

- See your concept maps from multiple perspectives

- Convert maps into checklists and outlines

- Incorporate photos of your hand-written mapping

Testimonials

Learn more about how a Writing Center coach uses TheBrain to create concept maps in our blog post, TheBrain and Zotero: Tech for Research Efficiency .

Works consulted

Holschuh, J. and Nist, S. (2000). Active learning: Strategies for college success. Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon.

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

SCS 224 (Campus) - Social Science Research Methods

Brainstorming and mind mapping, brainstorming.

Brainstorming is a way to come up with topics or ideas. It allows a person to casually consider multiple topics, ideas, theories, etc. without judgment and to take some ideas further into actual projects or as tools to consider more topics, ideas, theories, etc. MindTools' Brainstorming page has tools and more information about brainstorming.

Mind Mapping

A mind map is a visual representation of your issue or topic. It is a tool that is used to visualize ideas and opportunities for broadening or narrowing down search topics. MindTools' Mind Mapping page has tools and more information on mind mapping.

There are a number of free brainstorming and mind mapping tools available online like Bubbl.us and Popplet . Alternatively, try the mind map available via Credo Reference (click "Mind Map" on the Credo Reference homepage):

Lit Review Templates