Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning

Affiliations.

- 1 Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, Newcastle upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust / Senior Lecturer in Advanced Critical Care Practice, Department of Nursing, Midwifery and Health, Northumbria University.

- 2 Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

- PMID: 33983801

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.9.526

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient caseloads with undifferentiated and undiagnosed diseases are now a regular feature in healthcare practice. This article explores some of the key concepts and terminology that have evolved over the last four decades and have led to our modern day understanding of this topic. It also considers how clinical reasoning is vital for improving evidence-based diagnosis and subsequent effective care planning. A comprehensive guide to applying diagnostic reasoning on a body systems basis will be explored later in this series.

Keywords: Advanced practice; Clinical reasoning; Consultation; Critical thinking; Diagnostic accuracy.

- Advanced Practice Nursing*

- Clinical Reasoning*

- Nurse Practitioners* / psychology

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Critical thinking: what it is and why it counts. 2020. https://tinyurl.com/ybz73bnx (accessed 27 April 2021)

Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Curriculum for training for advanced critical care practitioners: syllabus (part III). version 1.1. 2018. https://www.ficm.ac.uk/accps/curriculum (accessed 27 April 2021)

Guerrero AP. Mechanistic case diagramming: a tool for problem-based learning. Acad Med.. 2001; 76:(4)385-9 https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200104000-00020

Harasym PH, Tsai TC, Hemmati P. Current trends in developing medical students' critical thinking abilities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci.. 2008; 24:(7)341-55 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70131-1

Hayes MM, Chatterjee S, Schwartzstein RM. Critical thinking in critical care: five strategies to improve teaching and learning in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc.. 2017; 14:(4)569-575 https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-1009AS

Health Education England. Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England. 2017. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/multi-professionalframeworkforadvancedclinicalpracticeinengland.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Health Education England, NHS England/NHS Improvement, Skills for Health. Core capabilities framework for advanced clinical practice (nurses) working in general practice/primary care in England. 2020. https://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/images/services/cstf/ACP%20Primary%20Care%20Nurse%20Fwk%202020.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Health Education England. Advanced practice mental health curriculum and capabilities framework. 2020. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/AP-MH%20Curriculum%20and%20Capabilities%20Framework%201.2.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Jacob E, Duffield C, Jacob D. A protocol for the development of a critical thinking assessment tool for nurses using a Delphi technique. J Adv Nurs.. 2017; 73:(8)1982-1988 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13306

Kohn MA. Understanding evidence-based diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl).. 2014; 1:(1)39-42 https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0003

Clinical reasoning—a guide to improving teaching and practice. 2012. https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/201201/45593

McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 4th edn. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2018

Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med.. 2017; 92:(1)23-30 https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

Papp KK, Huang GC, Lauzon Clabo LM Milestones of critical thinking: a developmental model for medicine and nursing. Acad Med.. 2014; 89:(5)715-20 https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000220

Rencic J, Lambert WT, Schuwirth L., Durning SJ. Clinical reasoning performance assessment: using situated cognition theory as a conceptual framework. Diagnosis.. 2020; 7:(3)177-179 https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0051

Examining critical thinking skills in family medicine residents. 2016. https://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol48Issue2/Ross121

Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Emergency care advanced clinical practitioner—curriculum and assessment, adult and paediatric. version 2.0. 2019. https://tinyurl.com/eps3p37r (accessed 27 April 2021)

Young ME, Thomas A, Lubarsky S. Mapping clinical reasoning literature across the health professions: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ.. 2020; 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02012-9

Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning

Sadie Diamond-Fox

Senior Lecturer in Advanced Critical Care Practice, Northumbria University, Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Co-Lead, Advanced Critical/Clinical Care Practitioners Academic Network (ACCPAN)

View articles

Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient caseloads with undifferentiated and undiagnosed diseases are now a regular feature in healthcare practice. This article explores some of the key concepts and terminology that have evolved over the last four decades and have led to our modern day understanding of this topic. It also considers how clinical reasoning is vital for improving evidence-based diagnosis and subsequent effective care planning. A comprehensive guide to applying diagnostic reasoning on a body systems basis will be explored later in this series.

The Multi-professional Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice highlights clinical reasoning as one of the core clinical capabilities for advanced clinical practice in England ( Health Education England (HEE), 2017 ). This is also identified in other specialist core capability frameworks and training syllabuses for advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) roles ( Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, 2018 ; Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2019 ; HEE, 2020 ; HEE et al, 2020 ).

Rencic et al (2020) defined clinical reasoning as ‘a complex ability, requiring both declarative and procedural knowledge, such as physical examination and communication skills’. A plethora of literature exists surrounding this topic, with a recent systematic review identifying 625 papers, spanning 47 years, across the health professions ( Young et al, 2020 ). A diverse range of terms are used to refer to clinical reasoning within the healthcare literature ( Table 1 ), which can make defining their influence on their use within the clinical practice and educational arenas somewhat challenging.

The concept of clinical reasoning has changed dramatically over the past four decades. What was once thought to be a process-dependent task is now considered to present a more dynamic state of practice, which is affected by ‘complex, non-linear interactions between the clinician, patient, and the environment’ ( Rencic et al, 2020 ).

Cognitive and meta-cognitive processes

As detailed in the table, multiple themes surrounding the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes that underpin clinical reasoning have been identified. Central to these processes is the practice of critical thinking. Much like the definition of clinical reasoning, there is also diversity with regard to definitions and conceptualisation of critical thinking in the healthcare setting. Facione (2020) described critical thinking as ‘purposeful reflective judgement’ that consists of six discrete cognitive skills: analysis, inference, interpretation, explanation, synthesis and self–regulation. Ross et al (2016) identified that critical thinking positively correlates with academic success, professionalism, clinical decision-making, wider reasoning and problem-solving capabilities. Jacob et al (2017) also identified that patient outcomes and safety are directly linked to critical thinking skills.

Harasym et al (2008) listed nine discrete cognitive steps that may be applied to the process of critical thinking, which integrates both cognitive and meta-cognitive processes:

- Gather relevant information

- Formulate clearly defined questions and problems

- Evaluate relevant information

- Utilise and interpret abstract ideas effectively

- Infer well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Pilot outcomes against relevant criteria and standards

- Use alternative thought processes if needed

- Consider all assumptions, implications, and practical consequences

- Communicate effectively with others to solve complex problems.

There are a number of widely used strategies to develop critical thinking and evidence-based diagnosis. These include simulated problem-based learning platforms, high-fidelity simulation scenarios, case-based discussion forums, reflective journals as part of continuing professional development (CPD) portfolios and journal clubs.

Dual process theory and cognitive bias in diagnostic reasoning

A lack of understanding of the interrelationship between critical thinking and clinical reasoning can result in cognitive bias, which can in turn lead to diagnostic errors ( Hayes et al, 2017 ). Embedded within our understanding of how diagnostic errors occur is dual process theory—system 1 and system 2 thinking. The characteristics of these are described in Table 2 . Although much of the literature in this area regards dual process theory as a valid representation of clinical reasoning, the exact causes of diagnostic errors remain unclear and require further research ( Norman et al, 2017 ). The most effective way in which to teach critical thinking skills in healthcare education also remains unclear; however, Hayes et al (2017) proposed five strategies, based on well-known educational theory and principles, that they have found to be effective for teaching and learning critical thinking within the ‘high-octane’ and ‘high-stakes’ environment of the intensive care unit ( Table 3 ). This is arguably a setting that does not always present an ideal environment for learning given its fast pace and constant sensory stimulation. However, it may be argued that if a model has proven to be effective in this setting, it could be extrapolated to other busy clinical environments and may even provide a useful aide memoire for self-assessment and reflective practices.

Integrating the clinical reasoning process into the clinical consultation

Linn et al (2012) described the clinical consultation as ‘the practical embodiment of the clinical reasoning process by which data are gathered, considered, challenged and integrated to form a diagnosis that can lead to appropriate management’. The application of the previously mentioned psychological and behavioural science theories is intertwined throughout the clinical consultation via the following discrete processes:

- The clinical history generates an initial hypothesis regarding diagnosis, and said hypothesis is then tested through skilled and specific questioning

- The clinician formulates a primary diagnosis and differential diagnoses in order of likelihood

- Physical examination is carried out, aimed at gathering further data necessary to confirm or refute the hypotheses

- A selection of appropriate investigations, using an evidence-based approach, may be ordered to gather additional data

- The clinician (in partnership with the patient) then implements a targeted and rationalised management plan, based on best-available clinical evidence.

Linn et al (2012) also provided a very useful framework of how the above methods can be applied when teaching consultation with a focus on clinical reasoning (see Table 4 ). This framework may also prove useful to those new to the process of undertaking the clinical consultation process.

Evidence-based diagnosis and diagnostic accuracy

The principles of clinical reasoning are embedded within the practices of formulating an evidence-based diagnosis (EBD). According to Kohn (2014) EBD quantifies the probability of the presence of a disease through the use of diagnostic tests. He described three pertinent questions to consider in this respect:

- ‘How likely is the patient to have a particular disease?’

- ‘How good is this test for the disease in question?’

- ‘Is the test worth performing to guide treatment?’

EBD gives a statistical discriminatory weighting to update the probability of a disease to either support or refute the working and differential diagnoses, which can then determine the appropriate course of further diagnostic testing and treatments.

Diagnostic accuracy refers to how positive or negative findings change the probability of the presence of disease. In order to understand diagnostic accuracy, we must begin to understand the underlying principles and related statistical calculations concerning sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood ratios.

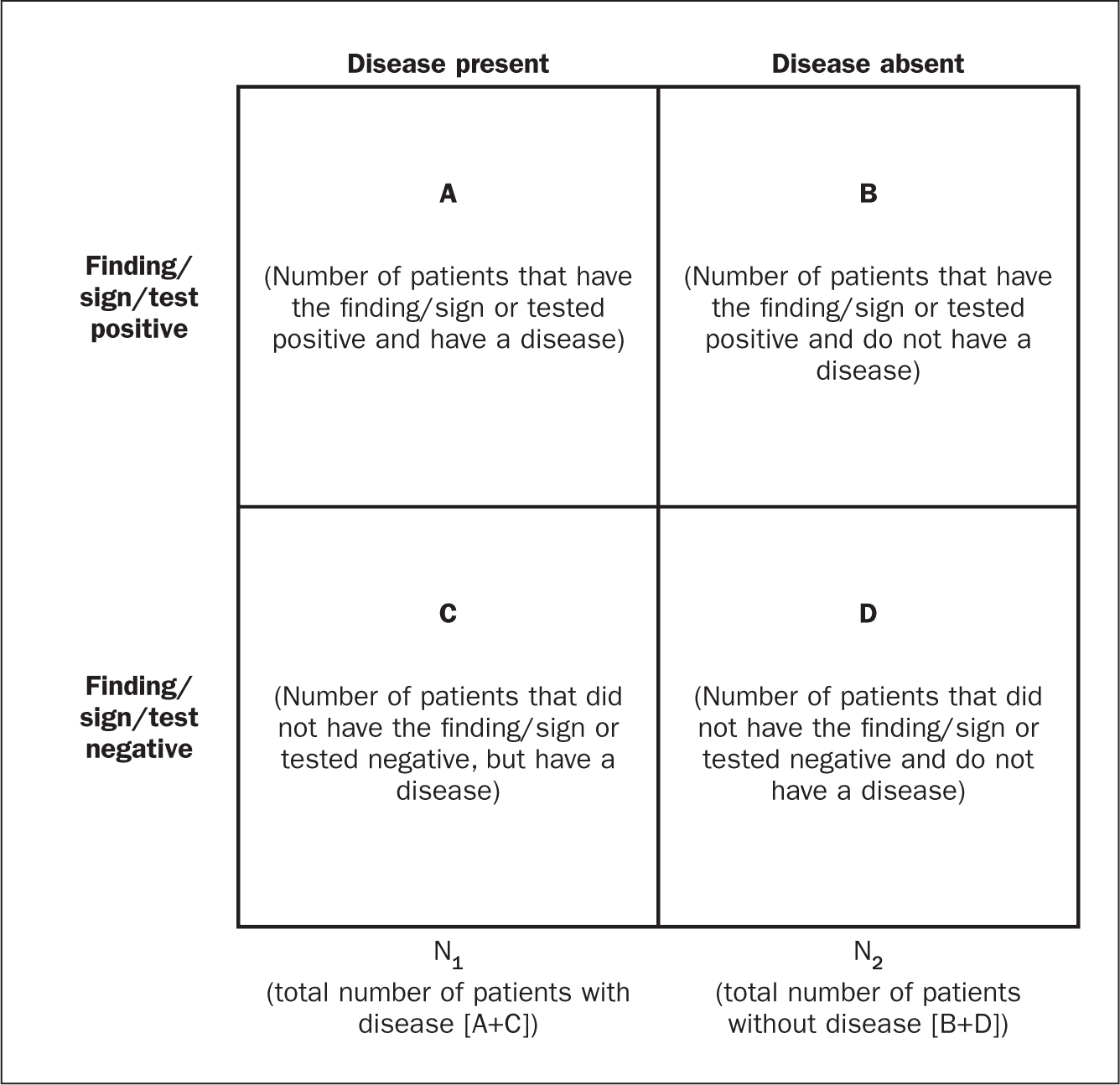

The construction of a two-by-two square (2 x 2) table ( Figure 1 ) allows the calculation of several statistical weightings for pertinent points of the history-taking exercise, a finding/sign on physical examination, or a test result. From this construct we can then determine the aforementioned statistical calculations as follows ( McGee, 2018 ):

- Sensitivity , the proportion of patients with the diagnosis who have the physical sign or a positive test result = A ÷ (A + C)

- Specificity , the proportion of patients without the diagnosis who lack the physical sign or have a negative test result = D ÷ (B + D)

- Positive predictive value , the proportion of patients with disease who have a physical sign divided by the proportion of patients without disease who also have the same sign = A ÷ (A + B)

- Negative predictive value , proportion of patients with disease lacking a physical sign divided by the proportion of patients without disease also lacking the sign = D ÷ (C + D)

- Likelihood ratio , a finding/sign/test results sensitivity divided by the false-positive rate. A test of no value has an LR of 1. Therefore the test would have no impact upon the patient's odds of disease

- Positive likelihood ratio = proportion of patients with disease who have a positive finding/sign/test, divided by proportion of patients without disease who have a positive finding/sign/test OR (A ÷ N1) ÷ (B÷ N2), or sensitivity ÷ (1 – specificity) The more positive an LR (the further above 1), the more the finding/sign/test result raises a patient's probability of disease. Thresholds of ≥ 4 are often considered to be significant when focusing a clinician's interest on the most pertinent positive findings, clinical signs or tests

- Negative likelihood ratio = proportion of patients with disease who have a negative finding/sign/test result, divided by the proportion of patients without disease who have a positive finding/sign/test OR (C ÷ N1) ÷ (D÷N1) or (1 – sensitivity) ÷ specificity The more negative an LR (the closer to 0), the more the finding/sign/test result lowers a patient's probability of disease. Thresholds <0.4 are often considered to be significant when focusing clinician's interest on the most pertinent negative findings, clinical signs or tests.

There are various online statistical calculators that can aid in the above calculations, such as the BMJ Best Practice statistical calculators, which may used as a guide (https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/ebm-toolbox/statistics-calculators/).

Clinical scoring systems

Evidence-based literature supports the practice of determining clinical pretest probability of certain diseases prior to proceeding with a diagnostic test. There are numerous validated pretest clinical scoring systems and clinical prediction tools that can be used in this context and accessed via various online platforms such as MDCalc (https://www.mdcalc.com/#all). Such clinical prediction tools include:

- 4Ts score for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

- ABCD² score for transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

- CHADS₂ score for atrial fibrillation stroke risk

- Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS).

Conclusions

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are fundamental skills of the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role. They are complex processes and require an array of underpinning knowledge of not only the clinical sciences, but also psychological and behavioural science theories. There are multiple constructs to guide these processes, not all of which will be suitable for the vast array of specialist areas in which ANMPs practice. There are multiple opportunities throughout the clinical consultation process in which ANMPs can employ the principles of critical thinking and clinical reasoning in order to improve patient outcomes. There are also multiple online toolkits that may be used to guide the ANMP in this complex process.

- Much like consultation and clinical assessment, the process of the application of clinical reasoning was once seen as solely the duty of a doctor, however the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role crosses those traditional boundaries

- Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are fundamental skills of the ANMP role

- The processes underlying clinical reasoning are complex and require an array of underpinning knowledge of not only the clinical sciences, but also psychological and behavioural science theories

- Through the use of the principles underlying critical thinking and clinical reasoning, there is potential to make a significant contribution to diagnostic accuracy, treatment options and overall patient outcomes

CPD reflective questions

- What assessment instruments exist for the measurement of cognitive bias?

- Think of an example of when cognitive bias may have impacted on your own clinical reasoning and decision making

- What resources exist to aid you in developing into the ‘advanced critical thinker’?

- What resources exist to aid you in understanding the statistical terminology surrounding evidence-based diagnosis?

Shaping Clinical Reasoning

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Rita Payan-Carreira 3 , 4 &

- Joana Reis 4 , 5

Part of the book series: Integrated Science ((IS,volume 12))

1009 Accesses

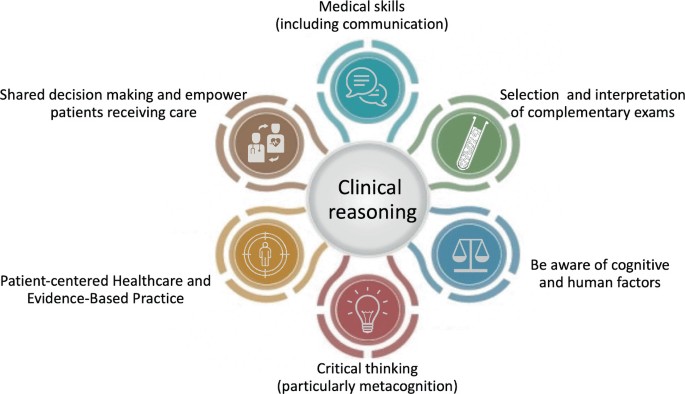

Clinical reasoning is at the core of all health-related professions, and it is long recognized as a critical skill for clinical practice. Yet, it is difficult to characterize it, as clinical reasoning combines different high-thinking abilities. Also, it is not content that is historically taught or learned in a particular subject. But clinical reasoning became increasingly visible when this competency is explicitly stated in the curricula of educational programs in health-related professions. Teaching and learning an abstract concept such as clinical reasoning in complement to the core knowledge and the procedural competencies expected from healthcare professionals raises some concerns regarding its implementation, the best way to do it, and how to assess it. This book chapter intends to discuss the need to invest in the development of clinical reasoning skills in the health-related graduation programme. It addresses some of the pedagogical and theoretical frameworks for fostering high-level reasoning and problem-solving skills in the clinical areas and the effectiveness and success of different pedagogic activities to develop and shape clinical reasoning throughout the curriculum.

Graphical Abstract/Art Performance

The elements involved in clinical reasoning.

- Clinical reasoning

- Clinical reasoning dimensions

- Competency-based learning

- Critical reasoning

- Curricular development

- Explicit learning

As medical educators […] we know that medical knowledge and competence is developmental; however, habits of the mind – behavior and practical – and wisdom are achieved through deliberate practice that can be achieved throughout medical school and with further refinement of medical skills during the clinical years […] Allison A. Vanderbilt et al. [ 1 ]

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Vanderbilt AA, Perkins SQ, Muscaro MK et al (2017) Creating physicians of the 21st century: assessment of the clinical years. Adv Med Educ Pract 8:395

Article Google Scholar

Higgs J, Jones MA (2008) Clinical decision making and multiple problem spaces. In: Higgs J, Jensen G, Loftus S, Christensen N (eds) Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 3–17

Google Scholar

Young ME, Thomas A, Lubarsky S et al (2020) Mapping clinical reasoning literature across the health professions: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 20:1–11

Daly P (2018) A concise guide to clinical reasoning. J Eval Clin Pract 24:966–972

Simmons B (2010) Clinical reasoning: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 66:1151–1158

Chin-Yee B, Upshur R (2018) Clinical judgement in the era of big data and predictive analytics. J Eval Clin Pract 24:638–645

Faucher C (2011) Differentiating the elements of clinical thinking. Optom Educ 36(3):140–145

Young M, Thomas A, Lubarsky S et al (2018) Drawing boundaries: the difficulty in defining clinical reasoning. Acad Med 93:990–995

Payan-Carreira R, Cruz G, Papathanasiou IV et al (2019) The effectiveness of critical thinking instructional strategies in health professions education: a systematic review. Stud High Educ 44:829–843

Gummesson C, Sundén A, Fex A (2018) Clinical reasoning as a conceptual framework for interprofessional learning: a literature review and a case study. Phys Ther Rev 23:29–34

Connor DM, Durning SJ, Rencic JJ (2020) Clinical reasoning as a core competency. Acad Med 95(8):1166–1171

May SA (2013) Clinical reasoning and case-based decision making: the fundamental challenge to veterinary educators. J Vet Med Educ 40:200–209

Evans JSB, Stanovich KE (2013) Dual-process theories of higher cognition: advancing the debate. Perspect Psychol Sci 8:223–241

Evans JSBT (2008) Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol 59:255–278

Ten Cate O (2017) Introduction. In: Ten Cate O, Custers EJFM, Durning SJ (eds) Principles and practice of case-based clinical reasoning education: a method for preclinical students. Springer Nature, pp 3–19

Croskerry P (2009) A universal model of diagnostic reasoning. Acad Med 84:1022–1028

Evans JSB (2019) Reflections on reflection: the nature and function of type 2 processes in dual-process theories of reasoning. Think Reason 25:383–415

Melnikoff DE, Bargh JA (2018) The mythical number two. Trends Cogn Sci 22:280–293

Handley SJ, Trippas D (2015) Dual processes and the interplay between knowledge and structure: a new parallel processing model. In: Psychology of learning and motivation. Elsevier, pp 33–58

Houdé O (2019) 3-system theory of the cognitive brain: a post-Piagetian approach to cognitive development. Routledge, pp 100–119

Braude HD (2017) 13 clinical reasoning and knowing. In: The Bloomsbury companion to contemporary philosophy of medicine. Bloomsbury Academic, pp 323–342

Medina MS, Castleberry AN, Persky AM (2017) Strategies for improving learner metacognition in health professional education. Am J Pharm Educ 81(4):78

Makary MA, Daniel M (2016) Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. The BMJ 353:i2139

LaRochelle JS, Dong T, Durning SJ (2015) Preclerkship assessment of clinical skills and clinical reasoning: the longitudinal impact on student performance. Mil Med 180:43–46

Clapper TC, Ching K (2020) Debunking the myth that the majority of medical errors are attributed to communication. Med Educ 54:74–81

Okafor N, Payne VL, Chathampally Y et al (2016) Using voluntary reports from physicians to learn from diagnostic errors in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 33:245–252

Braun LT, Zwaan L, Kiesewetter J et al (2017) Diagnostic errors by medical students: results of a prospective qualitative study. BMC Med Educ 17:191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-1044-7

Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J et al (2017) The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med 92:23–30

Deming M, Mark A, Nyemba V et al (2019) Cognitive biases and knowledge deficits leading to delayed recognition of cryptococcal meningitis. IDCases 18:e00588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00588

Article CAS Google Scholar

Royce CS, Hayes MM, Schwartzstein RM (2019) Teaching critical thinking: a case for instruction in cognitive biases to reduce diagnostic errors and improve patient safety. Acad Med 94:187–194

Wellbery C (2011) Flaws in clinical reasoning: a common cause of diagnostic error. Am Fam Physician 84:1042–1048

Amey L, Donald KJ, Teodorczuk A (2017) Teaching clinical reasoning to medical students. Br J Hosp Med 78:399–401

Stuart S, Hartig J, Willett L (2017) The importance of framing. J Gen Intern Med 32:706–710

Rylander M, Guerrasio J (2016) Heuristic errors in clinical reasoning. Clin Teach 13:287–290

O’sullivan E, Schofield S (2018) Cognitive bias in clinical medicine. J R College Physicians Edinburgh 48:225–232

Delany C, Golding C (2014) Teaching clinical reasoning by making thinking visible: an action research project with allied health clinical educators. BMC Med Educ 14:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-20

Elen J, Jiang L, Huyghe S et al (2019) Promoting critical thinking in European higher education institutions: towards an educational protocol. Vila Real: UTAD available at: https://repositorio.utad.pt/bitstream/10348/9227/1/CRITHINKEDU%20O4%20(ebook)_FINA

Miller GE (1990) The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 65:S63–S67

Payan-Carreira R, Dominguez C, Monteiro MJ, da Conceição Rainho M (2016) Application of the adapted FRISCO framework in case-based learning activities. Revista Lusófona de Educação 173–189

Hawkins D, Elder L, Paul R (2019) The thinker’s guide to clinical reasoning: based on critical thinking concepts and tools. Rowman & Littlefield

Keir JE, Saad SL, Davin L (2018) Exploring tutor perceptions and current practices in facilitating diagnostic reasoning in preclinical medical students: Implications for tutor professional development needs. MedEdPublish 7:(2). Available at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1942&context=med_article

Henard F, Roseveare D (2012) Fostering quality teaching in higher education: policies and practices. An IMHE Guide for Higher Education Institutions (OCDE publishing) 7–11. Available at http://supporthere.org/sites/default/files/qt_policies_and_practices_1.pdf

Barrett JL, Denegar CR, Mazerolle SM (2018) Challenges facing new educators: expanding teaching strategies for clinical reasoning and evidence-based medicine. Athl Train Educ J 13:359–366

Pyrko I, Dӧrfler V, Eden C (2017) Thinking together: what makes communities of practice work? Hum Relations 70:389–409

Payan-Carreira R, Cruz G (2019) Students’ study routines, learning preferences and self-regulation: are they related? In: Tsitouridou M, Diniz AJ, Mikropoulos T (eds) Technology and innovation in learning, teaching and education. TECH-EDU 2018. Communications in computer and information science, vol 993. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20954-4_14

Linsen A, Elshout G, Pols D et al (2018) Education in clinical reasoning: an experimental study on strategies to foster novice medical students’ engagement in learning activities. Health Prof Educ 4:86–96

Kozlowski D, Hutchinson M, Hurley J et al (2017) The role of emotion in clinical decision making: an integrative literature review. BMC Med Educ 17:255

Iacovides A, Fountoulakis K, Kaprinis S, Kaprinis G (2003) The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J Affect Disord 75:209–221

Audétat M-C, Laurin S, Sanche G et al (2013) Clinical reasoning difficulties: a taxonomy for clinical teachers. Med Teach 35:e984–e989. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.733041

Audétat M-C, Laurin S, Dory V et al (2017) Diagnosis and management of clinical reasoning difficulties: part I. Clinical reasoning supervision and educational diagnosis. Med Teach 39:792–796

Kumar DRR, Priyadharshini N, Murugan M, Devi R (2020) Infusing the axioms of clinical reasoning while designing clinical anatomy case vignettes teaching for novice medical students: a randomised cross over study. Anat Cell Biol 53:151

Huhn K, Black L, Christensen N et al (2018) Clinical reasoning: survey of teaching methods and assessment in entry-level physical therapist clinical education. J Phys Ther Educ 32:241–247

Patton N, Christensen N (2019) Pedagogies for teaching and learning clinical reasoning. In: Clinical reasoning in the Health professions. Elsevier, pp 335–344

Bowen JL (2006) Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med 355:2217–2225

Ajjawi R, Higgs J (2019) Learning to communicate clinical reasoning. In: Clinical reasoning in the health professions, pp 419–425

Levett-Jones T, Hoffman K, Dempsey J et al (2010) The “five rights” of clinical reasoning: an educational model to enhance nursing students’ ability to identify and manage clinically “at risk” patients. Nurse Educ Today 30:515–520

Gordon M, Findley R (2011) Educational interventions to improve handover in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ 45:1081–1089

Tiruneh DT, Verburgh A, Elen J (2013) Effectiveness of critical thinking instruction in higher education: a systematic review. High Educ Stud 4:1–17

Min Simpkins AA, Koch B, Spear-Ellinwood K, St. John P (2019) A developmental assessment of clinical reasoning in preclinical medical education. Med Educ Online 24:1591257

Tyo MB, McCurry MK (2019) An integrative review of clinical reasoning teaching strategies and outcome evaluation in nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect 40:11–17

Boulet JR, Durning SJ (2019) What we measure… and what we should measure in medical education. Med Educ 53:86–94

Ten Cate O, Durning SJ (2018) Approaches to assessing the clinical reasoning of preclinical students. In: Principles and practice of case-based clinical reasoning education. Springer, Cham, pp 65–72

Haffer AG, Raingruber BJ (1998) Discovering confidence in clinical reasoning and critical thinking development in baccalaureate nursing students. J Nurs Educ 37:61–70

Dominguez C (Coord. ) (2018) A European collection of the critical thinking skills and dispositions needed in different professional fields for the 21st century. UTAD https://repositorio.utad.pt/bitstream/10348/8319/1/CRITHINKEDU%20O1%20%28ebook%29.p

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work is being developed within the scope of the “Critical Thinking for Successful Jobs–Think4Jobs” project (Ref. Nr. 2020-1-EL01-KA203-078797) funded by the European Commission/EACEA, through the ERASMUS+ Programme. “The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.”

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Comprehensive Health Research Centre, Évora, Portugal

Rita Payan-Carreira

Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Évora, Polo da Mitra [Apartado 94], 7002-774, Évora, Portugal

Rita Payan-Carreira & Joana Reis

Escola Superior Agrária (ESA), Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo, CISAS, Viana do Castelo, Portugal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rita Payan-Carreira .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Universal Scientific Education and Research Network (USERN), Stockholm, Sweden

Nima Rezaei

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Payan-Carreira, R., Reis, J. (2023). Shaping Clinical Reasoning. In: Rezaei, N. (eds) Brain, Decision Making and Mental Health. Integrated Science, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15959-6_9

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-15958-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-15959-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.4: Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 63140

- Ernstmeyer & Christman (Eds.)

- Chippewa Valley Technical College via OpenRN

Prioritization of patient care should be grounded in critical thinking rather than just a checklist of items to be done. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.” [1] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs. It can be challenging for a novice nurse to change their mindset regarding their established “plan” for the day, but the sooner a nurse recognizes prioritization is dictated by their patients’ needs, the less frustration the nurse might experience. Prioritization strategies include collection of information and utilization of clinical reasoning to determine the best course of action. Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.” [2]

When nurses use critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills, they set forth on a purposeful course of intervention to best meet patient-care needs. Rather than focusing on one’s own priorities, nurses utilizing critical thinking and reasoning skills recognize their actions must be responsive to their patients. For example, a nurse using critical thinking skills understands that scheduled morning medications for their patients may be late if one of the patients on their care team suddenly develops chest pain. Many actions may be added or removed from planned activities throughout the shift based on what is occurring holistically on the patient-care team.

Additionally, in today’s complex health care environment, it is important for the novice nurse to recognize the realities of the current health care environment. Patients have become increasingly complex in their health care needs, and organizations are often challenged to meet these care needs with limited staffing resources. It can become easy to slip into the mindset of disenchantment with the nursing profession when first assuming the reality of patient-care assignments as a novice nurse. The workload of a nurse in practice often looks and feels quite different than that experienced as a nursing student. As a nursing student, there may have been time for lengthy conversations with patients and their family members, ample time to chart, and opportunities to offer personal cares, such as a massage or hair wash. Unfortunately, in the time-constrained realities of today’s health care environment, novice nurses should recognize that even though these “extra” tasks are not always possible, they can still provide quality, safe patient care using the “CURE” prioritization framework. Rather than feeling frustrated about “extras” that cannot be accomplished in time-constrained environments, it is vital to use prioritization strategies to ensure appropriate actions are taken to complete what must be done. With increased clinical experience, a novice nurse typically becomes more comfortable with prioritizing and reprioritizing care.

- Klenke-Borgmann, L., Cantrell, M. A., & Mariani, B. (2020). Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41 (4), 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nep.0000000000000669 ↵

Clinical Nurse Educators' LibGuide

- Keeping up to date This link opens in a new window

- Recent articles from the Journal of Nursing Education and Practice

- Critical thinking and clinical reasoning

- LibGuides Homepage This link opens in a new window

Library support

Library staff can assist you with:

- Literature searching

- Research skills training and support

- EndNote training

- Advice regarding getting published

- Document delivery to obtain full text of journal articles

- And more... see the Library website

Contact or visit your local CLIN Library to find out more about our full range of services and for assistance with your research project.

Some articles on critical thinking in nursing practice

- Fero, L. J., et al. (2009). "Critical thinking ability of new graduate and experienced nurses." Journal of Advanced Nursing 65(1): 139-148. This paper is a report of a study to identify critical thinking learning needs of new and experienced nurses. Concern for patient safety has grown worldwide as high rates of error and injury continue to be reported. In order to improve patient safety, nurses must be able to recognize changes in patient condition, perform independent nursing interventions, anticipate orders and prioritize. Conclusion. Patient safety may be compromised if a nurse cannot provide clinically competent care. Assessments such as the Performance Based Development System can provide information about learning needs and facilitate individualized orientation targeted to increase performance level. © 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Jacob, E., et al. (2018). "Development of an Australian nursing critical thinking tool using a Delphi process." Journal of Advanced Nursing. AIM To develop a critical thinking assessment tool for Australian undergraduate nurses. BACKGROUND Critical thinking is an important skill but difficult to assess in nursing practice. There are often many responses a nurse can make to a clinical problem or situation. Some responses are more correct than others and these decisions have an impact on a patient's care and safety. Differences in a response can relate to the depth of knowledge, experience and critical thinking ability of the individual nurse. DESIGN This study used a Delphi process to develop five clinical case studies together with the most appropriate clinical responses to 25 clinical questions. RESULTS Four rounds of Delphi questions were required to reach consensus on the correct wording and answers for the scenarios. Five case studies have been developed with nursing responses to patient management in rank order from most correct to least correct. CONCLUSION Use of the tool should provide confidence that a nurse has met a certain level of critical thinking ability.

- Ludin, S. M. (2017). "Does good critical thinking equal effective decision-making among critical care nurses? A cross-sectional survey."Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. v. 44 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.06.002 Background: A critical thinker may not necessarily be a good decision-maker, but critical care nurses are expected to utilise outstanding critical thinking skills in making complex clinical judgements. Studies have shown that critical care nurses' decisions focus mainly on doing rather than reflecting. To date, the link between critical care nurses' critical thinking and decision-making has not been examined closely in Malaysia.

- Simpson, E. and M. Courtney (2002). "Critical thinking in nursing education: literature review." International journal of nursing practice 8(2): 89-98. The need for critical thinking in nursing has been accentuated in response to the rapidly changing health-care environment. Nurses must think critically to provide effective care while coping with the expansion in role associated with the complexities of current health-care systems. This literature review will present a history of inquiry into critical thinking and research to support the conclusion that critical thinking is necessary not only in the clinical practice setting, but also as an integral component of nursing-education programmes to promote the development of nurses' critical-thinking abilities. The aims of this paper are to: (i) review the literature on critical thinking; (ii) examine the dimensions of critical thinking; (iii) investigate the various critical thinking strategies for their appropriateness to enhance critical thinking in nurses; and (iv) examine issues relating to the evaluation of critical-thinking skills in nursing.

- Turner, P. (2005) "Critical thinking in nursing education and practice as defined in the literature". Nursing Education Perspectives 26(5): 272-277. Critical thinking is frequently discussed in nursing education and nursing practice literature. This article presents an analysis of the concept of critical thinking as it applies to nursing, differentiating its use in education and practice literature. Three computerized databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, and EBSCO) were searched for the years 1981 to 2002, using the keywords critical thinking. References were stratified into two 11-year periods (1981-1991, 1992-2002) to identify changes in the concept over time and integration of the concept differentially into nursing education and nursing practice. A random sample of literature from each stratum was coded for definitions, attributes, surrogate terms, referents, antecedents, and consequences of critical thinking. Critical thinking as a nursing concept has matured since its first appearance in the literature. It is well defined and has clear characteristics. However, antecedents and consequences are not well defined, and many consequences are identical to attributes and surrogate terms. Additional work is needed to clarify the boundaries of the concept of critical thinking in nursing.

Key Features

New features.

Very good book, engaging, good use of figures and diagrams. Good application to practice - I will also be adding this to an International Health Assessment reading list.

This is a fantastic update from previous versions giving good scenarios for the students to work through. It includes all the relevant theories of clinical decision making and relates this to up to date practice.

Personally I love the practical approach and as such, it should be of use to my students. It couldn't be a core text though as the module is speciality specific, but I expect students to develop critical thinking and clinical reasoning within the module and they need ideas of ways to do this. Thank you for writing this text.

An excellent book used by other staff members and students. Very helpful when teaching communication and interpersonal skills

An exceptionally well written book, that related to all Healthcare professionals not just Nursing Students - the aspects on critical thinking has been central to the course

This year I was able to use a few chapters of the book to develop the basics of nursing course for English students.

Please verify your email.

We've sent you an email. Please follow the link to reset your password.

You can now close this window.

Edits have been made. Are you sure you want to exit without saving your changes?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.4 Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

Prioritization of patient care should be grounded in critical thinking rather than just a checklist of items to be done. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.” [1] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs. It can be challenging for a novice nurse to change their mindset regarding their established “plan” for the day, but the sooner a nurse recognizes prioritization is dictated by their patients’ needs, the less frustration the nurse might experience. Prioritization strategies include collection of information and utilization of clinical reasoning to determine the best course of action. Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.” [2]

When nurses use critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills, they set forth on a purposeful course of intervention to best meet patient-care needs. Rather than focusing on one’s own priorities, nurses utilizing critical thinking and reasoning skills recognize their actions must be responsive to their patients. For example, a nurse using critical thinking skills understands that scheduled morning medications for their patients may be late if one of the patients on their care team suddenly develops chest pain. Many actions may be added or removed from planned activities throughout the shift based on what is occurring holistically on the patient-care team.

Additionally, in today’s complex health care environment, it is important for the novice nurse to recognize the realities of the current health care environment. Patients have become increasingly complex in their health care needs, and organizations are often challenged to meet these care needs with limited staffing resources. It can become easy to slip into the mindset of disenchantment with the nursing profession when first assuming the reality of patient-care assignments as a novice nurse. The workload of a nurse in practice often looks and feels quite different than that experienced as a nursing student. As a nursing student, there may have been time for lengthy conversations with patients and their family members, ample time to chart, and opportunities to offer personal cares, such as a massage or hair wash. Unfortunately, in the time-constrained realities of today’s health care environment, novice nurses should recognize that even though these “extra” tasks are not always possible, they can still provide quality, safe patient care using the “CURE” prioritization framework. Rather than feeling frustrated about “extras” that cannot be accomplished in time-constrained environments, it is vital to use prioritization strategies to ensure appropriate actions are taken to complete what must be done. With increased clinical experience, a novice nurse typically becomes more comfortable with prioritizing and reprioritizing care.

- Klenke-Borgmann, L., Cantrell, M. A., & Mariani, B. (2020). Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41 (4), 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nep.0000000000000669 ↵

A broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”

A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.

Nursing Management and Professional Concepts Copyright © by Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

A Crash Course in Critical Thinking

What you need to know—and read—about one of the essential skills needed today..

Posted April 8, 2024 | Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

- In research for "A More Beautiful Question," I did a deep dive into the current crisis in critical thinking.

- Many people may think of themselves as critical thinkers, but they actually are not.

- Here is a series of questions you can ask yourself to try to ensure that you are thinking critically.

Conspiracy theories. Inability to distinguish facts from falsehoods. Widespread confusion about who and what to believe.

These are some of the hallmarks of the current crisis in critical thinking—which just might be the issue of our times. Because if people aren’t willing or able to think critically as they choose potential leaders, they’re apt to choose bad ones. And if they can’t judge whether the information they’re receiving is sound, they may follow faulty advice while ignoring recommendations that are science-based and solid (and perhaps life-saving).

Moreover, as a society, if we can’t think critically about the many serious challenges we face, it becomes more difficult to agree on what those challenges are—much less solve them.

On a personal level, critical thinking can enable you to make better everyday decisions. It can help you make sense of an increasingly complex and confusing world.

In the new expanded edition of my book A More Beautiful Question ( AMBQ ), I took a deep dive into critical thinking. Here are a few key things I learned.

First off, before you can get better at critical thinking, you should understand what it is. It’s not just about being a skeptic. When thinking critically, we are thoughtfully reasoning, evaluating, and making decisions based on evidence and logic. And—perhaps most important—while doing this, a critical thinker always strives to be open-minded and fair-minded . That’s not easy: It demands that you constantly question your assumptions and biases and that you always remain open to considering opposing views.

In today’s polarized environment, many people think of themselves as critical thinkers simply because they ask skeptical questions—often directed at, say, certain government policies or ideas espoused by those on the “other side” of the political divide. The problem is, they may not be asking these questions with an open mind or a willingness to fairly consider opposing views.

When people do this, they’re engaging in “weak-sense critical thinking”—a term popularized by the late Richard Paul, a co-founder of The Foundation for Critical Thinking . “Weak-sense critical thinking” means applying the tools and practices of critical thinking—questioning, investigating, evaluating—but with the sole purpose of confirming one’s own bias or serving an agenda.

In AMBQ , I lay out a series of questions you can ask yourself to try to ensure that you’re thinking critically. Here are some of the questions to consider:

- Why do I believe what I believe?

- Are my views based on evidence?

- Have I fairly and thoughtfully considered differing viewpoints?

- Am I truly open to changing my mind?

Of course, becoming a better critical thinker is not as simple as just asking yourself a few questions. Critical thinking is a habit of mind that must be developed and strengthened over time. In effect, you must train yourself to think in a manner that is more effortful, aware, grounded, and balanced.

For those interested in giving themselves a crash course in critical thinking—something I did myself, as I was working on my book—I thought it might be helpful to share a list of some of the books that have shaped my own thinking on this subject. As a self-interested author, I naturally would suggest that you start with the new 10th-anniversary edition of A More Beautiful Question , but beyond that, here are the top eight critical-thinking books I’d recommend.

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark , by Carl Sagan

This book simply must top the list, because the late scientist and author Carl Sagan continues to be such a bright shining light in the critical thinking universe. Chapter 12 includes the details on Sagan’s famous “baloney detection kit,” a collection of lessons and tips on how to deal with bogus arguments and logical fallacies.

Clear Thinking: Turning Ordinary Moments Into Extraordinary Results , by Shane Parrish

The creator of the Farnham Street website and host of the “Knowledge Project” podcast explains how to contend with biases and unconscious reactions so you can make better everyday decisions. It contains insights from many of the brilliant thinkers Shane has studied.

Good Thinking: Why Flawed Logic Puts Us All at Risk and How Critical Thinking Can Save the World , by David Robert Grimes

A brilliant, comprehensive 2021 book on critical thinking that, to my mind, hasn’t received nearly enough attention . The scientist Grimes dissects bad thinking, shows why it persists, and offers the tools to defeat it.

Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know , by Adam Grant

Intellectual humility—being willing to admit that you might be wrong—is what this book is primarily about. But Adam, the renowned Wharton psychology professor and bestselling author, takes the reader on a mind-opening journey with colorful stories and characters.

Think Like a Detective: A Kid's Guide to Critical Thinking , by David Pakman

The popular YouTuber and podcast host Pakman—normally known for talking politics —has written a terrific primer on critical thinking for children. The illustrated book presents critical thinking as a “superpower” that enables kids to unlock mysteries and dig for truth. (I also recommend Pakman’s second kids’ book called Think Like a Scientist .)

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters , by Steven Pinker

The Harvard psychology professor Pinker tackles conspiracy theories head-on but also explores concepts involving risk/reward, probability and randomness, and correlation/causation. And if that strikes you as daunting, be assured that Pinker makes it lively and accessible.

How Minds Change: The Surprising Science of Belief, Opinion and Persuasion , by David McRaney

David is a science writer who hosts the popular podcast “You Are Not So Smart” (and his ideas are featured in A More Beautiful Question ). His well-written book looks at ways you can actually get through to people who see the world very differently than you (hint: bludgeoning them with facts definitely won’t work).

A Healthy Democracy's Best Hope: Building the Critical Thinking Habit , by M Neil Browne and Chelsea Kulhanek

Neil Browne, author of the seminal Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking, has been a pioneer in presenting critical thinking as a question-based approach to making sense of the world around us. His newest book, co-authored with Chelsea Kulhanek, breaks down critical thinking into “11 explosive questions”—including the “priors question” (which challenges us to question assumptions), the “evidence question” (focusing on how to evaluate and weigh evidence), and the “humility question” (which reminds us that a critical thinker must be humble enough to consider the possibility of being wrong).

Warren Berger is a longtime journalist and author of A More Beautiful Question .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Chatbot outperformed physicians in clinical reasoning in head-to-head study

Artificial intelligence was also 'just plain wrong' significantly more often.

ChatGPT-4, an artificial intelligence program designed to understand and generate human-like text, outperformed internal medicine residents and attending physicians at two academic medical centers at processing medical data and demonstrating clinical reasoning. In a research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine , physician-scientists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) compared a large language model's (LLM) reasoning abilities directly against human performance using standards developed to assess physicians.

"It became clear very early on that LLMs can make diagnoses, but anybody who practices medicine knows there's a lot more to medicine than that," said Adam Rodman MD, an internal medicine physician and investigator in the department of medicine at BIDMC. "There are multiple steps behind a diagnosis, so we wanted to evaluate whether LLMs are as good as physicians at doing that kind of clinical reasoning. It's a surprising finding that these things are capable of showing the equivalent or better reasoning than people throughout the evolution of clinical case."

Rodman and colleagues used a previously validated tool developed to assess physicians' clinical reasoning called the revised-IDEA (r-IDEA) score. The investigators recruited 21 attending physicians and 18 residents who each worked through one of 20 selected clinical cases comprised of four sequential stages of diagnostic reasoning. The authors instructed physicians to write out and justify their differential diagnoses at each stage. The chatbot GPT-4 was given a prompt with identical instructions and ran all 20 clinical cases. Their answers were then scored for clinical reasoning (r-IDEA score) and several other measures of reasoning.

"The first stage is the triage data, when the patient tells you what's bothering them and you obtain vital signs," said lead author Stephanie Cabral, MD, a third-year internal medicine resident at BIDMC. "The second stage is the system review, when you obtain additional information from the patient. The third stage is the physical exam, and the fourth is diagnostic testing and imaging."

Rodman, Cabral and their colleagues found that the chatbot earned the highest r-IDEA scores, with a median score of 10 out of 10 for the LLM, 9 for attending physicians and 8 for residents. It was more of a draw between the humans and the bot when it came to diagnostic accuracy -- how high up the correct diagnosis was on the list of diagnosis they provided -- and correct clinical reasoning. But the bots were also "just plain wrong" -- had more instances of incorrect reasoning in their answers -- significantly more often than residents, the researchers found. The finding underscores the notion that AI will likely be most useful as a tool to augment, not replace, the human reasoning process.

"Further studies are needed to determine how LLMs can best be integrated into clinical practice, but even now, they could be useful as a checkpoint, helping us make sure we don't miss something," Cabral said. "My ultimate hope is that AI will improve the patient-physician interaction by reducing some of the inefficiencies we currently have and allow us to focus more on the conversation we're having with our patients.

"Early studies suggested AI could makes diagnoses, if all the information was handed to it," Rodman said. "What our study shows is that AI demonstrates real reasoning -- maybe better reasoning than people through multiple steps of the process. We have a unique chance to improve the quality and experience of healthcare for patients."

Co-authors included Zahir Kanjee, MD, Philip Wilson, MD, and Byron Crowe, MD, of BIDMC; Daniel Restrepo, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital; and Raja-Elie Abdulnour, MD, of Brigham and Women's Hospital.

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health) (award UM1TR004408) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Rodman reports grant funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Crowe reports employment and equity in Solera Health. Kanjee reports receipt of royalties for books edited and membership on a paid advisory board for medical education products not related to AI from Wolters Kluwer, as well as honoraria for continuing medical education delivered from Oakstone Publishing. Abdulnour reports employment by the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS), a not-for-profit organization that owns NEJM Healer. Abdulnour does not receive royalty from sales of NEJM Healer and does not have equity in NEJM Healer. No funding was provided by the MMS for this study. Abdulnour reports grant funding from the Gordan and Betty Moore Foundation via the National Academy of Medicine Scholars in Diagnostic Excellence.

- Today's Healthcare

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Imaging

- Personalized Medicine

- Artificial Intelligence

- Information Technology

- Computer vision

- Alternative medicine

- Positron emission tomography

- Artificial intelligence

- Ophthalmology

- Scientific visualization

Story Source:

Materials provided by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Stephanie Cabral, Daniel Restrepo, Zahir Kanjee, Philip Wilson, Byron Crowe, Raja-Elie Abdulnour, Adam Rodman. Clinical Reasoning of a Generative Artificial Intelligence Model Compared With Physicians . JAMA Internal Medicine , 2024; DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.0295

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Pregnancy Accelerates Biological Aging

- Tiny Plastic Particles Are Found Everywhere

- What's Quieter Than a Fish? A School of Them

- Do Odd Bones Belong to Gigantic Ichthyosaurs?

- Big-Eyed Marine Worm: Secret Language?

- Unprecedented Behavior from Nearby Magnetar

- Soft, Flexible 'Skeletons' for 'Muscular' Robots

- Toothed Whale Echolocation and Jaw Muscles

- Friendly Pat On the Back: Free Throws

- How the Moon Turned Itself Inside Out

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. ... Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning Br J Nurs. 2021 May 13;30(9):526-532. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.9.526 ...

As detailed in the table, multiple themes surrounding the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes that underpin clinical reasoning have been identified. Central to these processes is the practice of critical thinking. Much like the definition of clinical reasoning, there is also diversity with regard to definitions and conceptualisation of critical thinking in the healthcare setting.

1. Describe critical thinking (CT), clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment in your own words, based on the descriptions in this chapter. 2. Give at least three reasons why CT skills are essential for stu-dents and nurses. 3. Explain (or map) how the following terms are related to one another: critical thinking, clinical reasoning, clinical ...

Abstract. Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient ...

Abstract. Concepts of critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment are often used interchangeably. However, they are not one and the same, and understanding subtle difference among them is important. Following a review of the literature for definitions and uses of the terms, the author provides a summary focused on similarities ...

The terms "critical thinking" and "clinical reasoning" are used frequently in medical education, often synonymously, but they are rarely explicitly defined. At a national conference in 2011, teams from nine medical schools defined critical thinking as "the ability to apply higher cognitive skills (eg, analysis, synthesis, self-

Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning. Nurses make decisions while providing patient care by using critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes "reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow." [1] Using critical thinking means that nurses take extra steps to maintain patient safety ...

Summary. Clinical reasoning is at the core of all health-related professions, and it is long recognized as a critical skill for clinical practice. Yet, it is difficult to characterize it, as clinical reasoning combines different high-thinking abilities. Also, it is not content that is historically taught or learned in a particular subject.

Teaching clinical reasoning is challenging, particularly in the time-pressured and complicated environment of the ICU. Clinical reasoning is a complex process in which one identifies and prioritizes pertinent clinical data to develop a hypothesis and a plan to confirm or refute that hypothesis. Clinical reasoning is related to and dependent on critical thinking skills, which are defined as one ...

To foster clinical reasoning and critical thinking skills, faculty must help learners develop analytic reasoning skills and habits of life-long self-directed learning. These skills are necessary to identify, prioritize, and justify pertinent positive and negative data from a patient's presentation.

Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes "reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.". [1] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs.

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning strategies come to life through the use of real-life scenarios and decision-making tools, all supported with evidence for why the strategies work. Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice by Eileen Gambrill. Call Number: Proquest Ebook Central.

Alfaro's Critical Thinking, Clinical Reasoning, and Clinical Judgment, 6th Edition! With a motivational style and insightful "how-to" approach, this unique textbook draws upon real-life scenarios and evidence-based strategies as it guides you in learning to think critically in clinically meaningful ways. The new edition features a more ...

Develop the critical thinking and reasoning skills you need to make sound clinical judgments! Alfaro-LeFevre's Critical Thinking, Clinical Reasoning, and Clinical Judgment: A Practical Approach, 7 th Edition brings these concepts to life through engaging text, diverse learning activities, and real-life examples. Easy-to-understand language and a "how-to" approach equip you to become a sensible ...

Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes "reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.". [1] Certainly, there are many actions that nurses must complete during their shift, but nursing requires adaptation and flexibility to meet emerging patient needs.

Here is a series of questions you can ask yourself to try to ensure that you are thinking critically. Conspiracy theories. Inability to distinguish facts from falsehoods. Widespread confusion ...

Clinical Reasoning of a Generative Artificial Intelligence Model Compared With Physicians. JAMA Internal Medicine , 2024; DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.0295 Cite This Page :

Build the critical thinking capabilities essential to your success with this captivating, case-based approach. Maternity, Newborn, and Women's Health Nursing: A Case-Based Approach brings the realities of nursing practice to life and helps you acquire the understanding and clinical reasoning