Boys enjoy educational advantages despite being less engaged in school than girls

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, jaymes pyne jp jaymes pyne quantitative research associate, john gardner center - stanford university @jaymes_pyne.

July 30, 2020

Girls are more engaged in school than boys, and that is a big reason girls (and women) tend to do better educationally . But rather than thinking of engagement as an educational advantage, we might better consider it as protective to girls, who confront many other disadvantages in school and life.

This is the takeaway of a research brief I recently published in the journal Educational Researcher. Nationally, girls do better than boys on reading tests but trail boys on math tests. I analyzed nationally representative data on boys’ and girls’ fifth-grade reading and math test scores and reports of their classroom behavioral engagement throughout elementary school. I found that if there were no gender differences in behavioral engagement patterns through elementary school, fifth-grade reading test score gaps could reverse and math test score gaps could triple in size .

That means focusing simply on increasing boys’ behavioral engagement in school overlooks unaddressed needs of girls. It may be time to reconsider what we mean when we say that girls have behavioral “advantages” over boys in school.

What is behavioral engagement, and why do girls have more of it than boys?

Behavioral engagement is participation in the work and social life of school in ways educators value and expect. That means following classroom expectations like raising your hand, respecting others’ personal boundaries, turning assignments in on time, and responding appropriately to negativity—among many more positive behaviors expected in class. Underlying behavioral engagement is a wide-ranging set of social and behavioral skills that families instill well before children enter school and skills that children learn along the way while in school.

The literature is divided on why girls seem more engaged in school than boys. One perspective emphasizes gender (and class) bias on the part of mostly middle-class, female teachers who evaluate students’ behaviors. Another perspective emphasizes gender socialization —that girls tend to be raised to behave in ways that align with how educators expect all students to behave. Although both can be true, some work using national data casts doubt on the teacher bias narrative by presenting evidence of a direct link between behavioral engagement and later learning. This suggests girls’ higher behavioral engagement likely stems from gendered ways of socializing young children prior to and during elementary school.

Why would boys score higher if they were as engaged as girls?

Since girls are more engaged than boys, equalizing engagement could lead to large reading and math achievement gaps favoring boys. Part of the explanation is that gender gaps on achievement tests have a lot to do with engagement and motivation to take the test itself . If boys were engaged in school more generally, it’s reasonable to believe that would translate to boys wanting to do better on these tests. However, my and other research suggests it’s not likely to be just a question of boys being more intelligent and underperforming because they lack interest in doing well on the test.

What is it then about schools that helps boys, even when they aren’t very engaged? Existing literature helps us understand.

First, girls aren’t encouraged to be interested in the same intellectual pursuits as boys. For example, although explanations of gender STEM gaps vary, research has shown that gender bias can arise through parents’ and teachers ’ own anxieties about STEM subjects and their beliefs about boys’ and girls’ natural abilities in STEM fields. Those early redirections ripple into adulthood— women still lag men in engineering, physical science, and computer science degree attainment –but are not necessarily due to differences in academic ability. For example, a recent study shows that low-achieving men are much more likely to major in physics, engineering, and computer science relative to low-achieving women after accounting for a range of student-level factors.

Second, other behaviors in school are sanctioned and rewarded differently by gender. Girls may be socialized early in life in ways that help them engage in school, but educators and peers informally reward and reinforce hegemonic masculinity and, with it, boys’ superiority and flouting of school rules. For example—as Michela Musto has recently shown us –boys misbehave more than girls in class, but teachers and peers also encourage and reward boys to engage by challenging girls’ perspectives and dominating discussions. In the end? Peers regard (usually white) intelligent boys as much more “exceptional” than otherwise similarly intelligent girls.

Where to go from here?

At the very least, this research challenges the perspective that girls have taken a resounding advantage in educational pursuits due to legal, political, and advocacy movements over the last 50 years. That perspective does correctly recognize the social and economic consequences of ignoring boys’ comparatively languishing behavioral performances in schools. Yet a simple focus on improving boys’ outcomes will certainly uncover remaining constraints on girls in schools and society at large. That will include some interventions that we are aware of, such as encouraging girls to build confidence and aspire to enter STEM fields . Others may be clear only after looking under the gilded veneer of high engagement that helps girls shine in school.

Related Content

Joseph Cimpian

April 23, 2018

Christina Kwauk, Amanda Braga, Helyn Kim

April 3, 2017

Seth Gershenson

January 13, 2016

K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Jennifer B. Ayscue, Kfir Mordechay, David Mickey-Pabello

March 26, 2024

Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff, Dan Silver

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

BOY-CHILD EDUCATION IN NIGERIA: ISSUES AND IMPLICATIONS ON NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

This article is an in-depth study on boy-child education in Nigeria. This is not a debate between boy-child education and girl-child education which is more important and why, rather it is a research that constructively calls the attention of all and sundry to the neglect of the boy-child education and its implications on National development. When the boy-child is not educated on positive line of thoughts like peace, love, obedience, humility and loyalty, he develops his mind with negative thoughts like greed, theft, jealousy, arrogance and violence. The importance of the boy-child education to the development of any nation cannot be overemphasised. Sustainability of the development of any nation remains a hoax if education is not made for all. The boy-child is neglected because he is perceived to be a superhuman. A child is a child, irrespective of colour, creed, gender or race. In his quest to be educated, the boy-child faces so many issues such as poverty, poor performance in examinations, lack of concentration, lack of adequate security, corruption and gender bias. The paper made the following recommendations: education should be provided for all without discrimination; government should examine and revive the curriculum and teachings in classes that are not gender biased; Peace education should be included in the educational curriculum; the government should propagate laws making boy-child education compulsory in Nigeria and the mindset of the people should also be changed against the notion that boys are better than girls.

Related Papers

Integrity Journal of Education and Training

Integrity Research Journals

Importance of Girl-Child education has become a frontline issue in many discourses held globally in recent times. The premium placed on the Girl-Child's education is a result of several awareness/enlightenment campaigns on the need for the Girl-Child to assume her rightful place in society. The illiteracy of the Girl-Child has chain effects on the family; which is the primary agent of socialization and the society in general. For social development to be rightly positioned in Nigeria and to result in the overall development of the nation, the Girl-Child must become an active player in the society. The paper concludes that the Girl-Child having been denied education due to a lot of reasons surrounding her sex must be given educational opportunities like her male counterparts to enable her fulfill her potentials as a member of the Nigerian society in line with the Child Right's Act of 2003 and recommends amongst others that early marriages and other cultural practices which denies the Girl-Child her right to education should be eradicated for optimum growth of the female child through education.

Journal of Education and Practice

Mamman Bello Ali

Olasunkanmi Olusogo Olagunju

This is an attempt to critically investigate the growing disparities in gender enrollment in basic education in Nigeria. This paper examine some of the alarming issues that promote girl-child illiteracy in Nigeria and thereby examine the success and failure of policy in place to bridge the gap in boy/girl literacy rate in the country. It therefore conclude that this policy has not achieved a significant success in addressing the chronic disparity in girl-child enrollment in basic education in Nigeria due to some internal dynamics. It consequently suggests some policy recommendations necessary to bridge the gender gap in enrollment in basic education in Nigeria. Key word: Gender, policy, formulation, implementation, evaluation and education.

Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHASS)

nadir abdulhadi

Since the introduction of Western education to Northern Nigeria, especially in the 1920s, many Muslims in the region found it objectionable as it tempered with their religio-cultural values including for instance, co-education. In light of this therefore, this paper identifies and examines the major challenges affecting girl child education in Ungogo Local Government Area of Kano State, Nigeria. Using both primary and secondary sources that are augmented with a qualitative data analysis, the researchers administered a total number of 120 questionnaires across five (5) political wards of Ungogo Local Government Area that were purposively sampled. Out of the 120 questionnaires administered, only 105 were retrieved representing 87.5% response rate. Data collected is analysed using descriptive statistics. Results revealed that religio-cultural reasons, poverty, lack of viable government educational policies and parental preference to educate the male child are the major factors curtaili...

Open Access Publishing Group , Jacob Filgona

In Nigeria and in Mubi North Local Government Area in particular, the girl-child access to basic education was observed to be at its lowest ebb. The reasons for this may revolve around religious and cultural beliefs. This study examined the role of women education in national development; particularly in the aspect of children's health and educational attainment. The sample for the study consisted of 200 women randomly selected from five villages in Mubi North Local Government Area of Adamawa State in Nigeria. A checklist was used to collect data from the respondents. The internal consistency of the instrument was determined using Guttmann's Split-Half statistic. This yielded a reliability value of 0.80. Data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics of frequency counts, percentages and Kolmogorov-Smirnov z two samples test. Results of data analysis showed that women education could play a significant role towards improving the health and education of children. The study also identified male-child preference, early marriage, cultural and religious misinterpretation as the major factors militating against female education, particularly in Mubi North Local Government Area of Adamawa. Based on these findings, it was recommended that Government should make women education compulsory and free at the basic education level.

ali ibrahim abbas

This paper explores the efforts of Girl Child Education (GCE) development put in place by Governor Gaidam's regime in Yobe state, Nigeria from 2009 to 2015 as a tool for achieving gendered education development. It aims to provide the description and analysis of democratic regime performance in the development of Girl Child Education (GCE) through the perspectives and experiences of democratic stakeholders in democratic governance process in the state. The qualitative study is therefore based on the narratives of indepth interviews with democratic and education stakeholders and the review of education policy documents. The findings suggest that although there have been efforts to address the challenges of GCE through concerted efforts, the gender distribution of pupils and students at basic education levels reveals a low representation of girls than boys in Yobe state. The failure to achieve gender parity in education development is associated with poor access, lack of female role models, social, political, cultural and economic reasons and Boko Haram insurgency. This paper recommends that these issues can be addressed if more schools are established for girls, inspirations from female educators and roles models, better economic and political empowerment for young women and girls, and ensuring a peaceful and conducive learning atmosphere for the girls and women.

SURAJU, Saheed Badmus, Ph.D.

Eric Chikweru Amadi Dr

This research examines the effect of socio-cultural factors on the Girl-Child education in secondary schools in Ihiala Local Government Area of Anambra State. It is a survey study. The research also took not of some key factors, which among other things, include the great attitude of parents towards girl-child education effect of early marriage. Influence of the family background and size and the socio-economic situation in the community. The findings showed that almost all the above mentioned factors are responsible for limited access of the girl- child education. To limit or reduce the effect of the factors, therefore, the researcher recommends and suggests more awareness campaign, not only for girls but also for parents to take seriously the education of their girl-child. Just as they do for their boy-child. The researcher also suggests ways for improving on girl-child in Ihiala community and all other communities that share similar cultural and socio-economic similarities with I...

African Research Review

Yetunde Ajayi

Aisha Ibrahim

Education at all levels is the process through which individuals are made functional members of their society. It is also a process, through which the individual acquires knowledge, realizes his/her potentialities, and uses them for self actualization and to be useful to others. In every civilized community, children are regarded as the greatest asset society can possess. They are therefore, cherished and protected from all forms of abuse and neglect. For the girl-child however, she may not be so lucky to be that protected due to certain traditional beliefs and practices which put her at high risk of abuse and neglect. Illiteracy and poverty are other factors which further put the girl-child at high risk of exploitation and violation of her right. Yet, she is expected to grow into the good mother of tomorrow even in the face of these disadvantages. Indeed, under such conditions of abuse and neglect, the girl-child education has come to symbolize the reality of all forms of discrimin...

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Peter Herscovitch

Dwi Hidayatul Firdaus

Physical Review Letters

European Urology Supplements

alejandro carvajal

ASAIO Journal

Frank Mendoza

Conference Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics

Audrey Syme

International forum of allergy & rhinology

Amber Luong

Barnabas Emenogu

Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação: do campo à mesa

ROSANE MARINA PERALTA

Macromolecules

Nhu Quynh Nguyen

Mahmudul Hasan

Anang Fathkurrahman

Translational Cancer Research

Energy Conversion and Management

Aleksandar Georgiev

Cardiology in the Young

S M Minhaz Uddin

Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board

Merin Johnson

Atherosclerosis

Funda Catan Inan

Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications

Chewki Ziani-Cherif

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution

Susan Lawler

Sustainability

Lidia Catarino

Paediatrics & Child Health

Sherri Katz

IntechOpen eBooks

Fatima Boukhlifi

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

UNICEF Data : Monitoring the situation of children and women

How do the educational experiences of girls and boys differ?

- Data and Research

Beginning as early as primary school and continuing through secondary school, the journey of education can be vastly different depending on whether a child is a boy or a girl. Measuring these differences and whether they result in advantages or disadvantages for children is critical for education policy planning. Policymakers need to be equipped with gender analysis so that they can address inequities in schooling between girls and boys and target interventions to prevent the most marginalized students from being left behind.

Education pathway analysis tracks the progression of youth of upper secondary school age (typically aged 15 to 17) from the point of entry into primary school through transition to upper secondary school. Building on a previous report analyzing education levels across 103 countries and territories, this blog spotlights the distinct educational trajectories of girls and boys and where they might diverge.

Globally girls and boys are equally likely to enter primary school and transition to lower secondary school, but girls are more likely to transition to upper secondary school.

Who has the advantage when it comes to entering primary school in the first place? Globally, it turns out that there is gender parity on average, meaning that there are roughly the same number of boys and girls who enter primary school. Around the world, 91 per cent of girls ever enter primary school compared to 93 per cent of boys.

As the education journey continues, however, the balance starts to progressively shift in favor of girls. An almost equal share of girls and boys make the transition to lower secondary school – 78 per cent versus 79 per cent, respectively. Girls continue to gain ground as they progress to the next stage of their education, and even surpass boys as they make the transition to upper secondary school. Globally, 54 per cent of girls make this transition as opposed to 52 per cent of boys, with the difference large enough to acknowledge that girls have obtained the advantage.

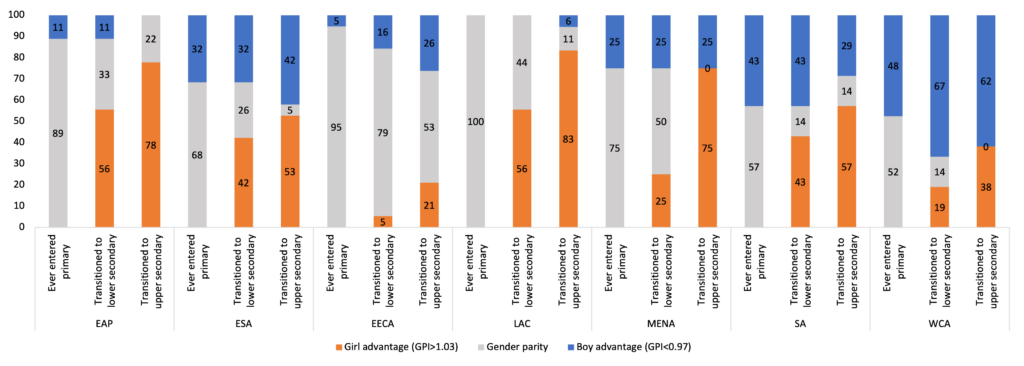

Education pathway analysis around the world by gender

Source: UNICEF Education Pathway Analysis database (2021)

Though boys start out with a distinct advantage in entering primary school, this balance shifts in favor of girls in upper secondary school.

The global picture belies notable exceptions at the country level, however (Fig 2). Although girls and boys begin primary school on an equal footing in 80 countries, boys begin with a distinct advantage in 23 countries. Notably, in all countries analyzed, either more boys enter primary school than girls or the enrollment of boys is on par with that of girls .

Girls gradually gain the advantage as they continue their schooling, and by the time they transition to lower secondary school, girls have assumed the advantage in 33 countries. But girls do not gain ground everywhere, as boys have the advantage in 30 countries at the point of transition to lower secondary, up from 23 countries for primary school.

Number of countries with gender parity in school enrollment, girl advantage, or boy advantage, by level of education

Nevertheless, girls continue to advance as they make the transition to upper secondary school , such that girls have the advantage in more than half of the countries (55 in total) at this stage of their education . This is especially noteworthy considering that girls did not start out their educational journeys having an advantage in any of the 103 countries and territories. Rather, they were able to “catch up” as they continued their education. Boys also experienced some advancement , as the number of countries where boys had the advantage increase d as well, up from 23 at entry to primary to 32 at the transition to upper secondary school. This suggests that when boys start out having an advantage, they tend to maintain and slowly expand this advantage over time , which could speak to the persistence of discriminatory gender norms against girls in some countries . Overall, however, t he findings point to the strides that girls have made along their educational journeys, when they initially start out on either an equal footing with boys o r disadvantaged to them , and then frequently surpass boys by the time they transition to upper secondary school .

Most regions begin with gender parity in school enrollment and then girls gain the advantage, with the exception of Western and Central Africa where boys maintain the advantage through upper secondary school.

Grouping the countries by region also reveals some interesting differences (Fig. 3). In East Asia and the Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean, there was predominantly gender parity at the start of children’s educational journey, but girls decidedly gained the advantage by the time they transitioned to upper secondary school. Among countries in Eastern and Southern Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia, some boys began with an advantage in entry to primary, but by the time of transition to upper secondary school, girls had gained the advantage in the majority of countries. Western and Central Africa is the only region in which boys retained the advantage through the transition to upper secondary school.

Percentage of countries with gender parity, girl or boy advantage, by level of education and region

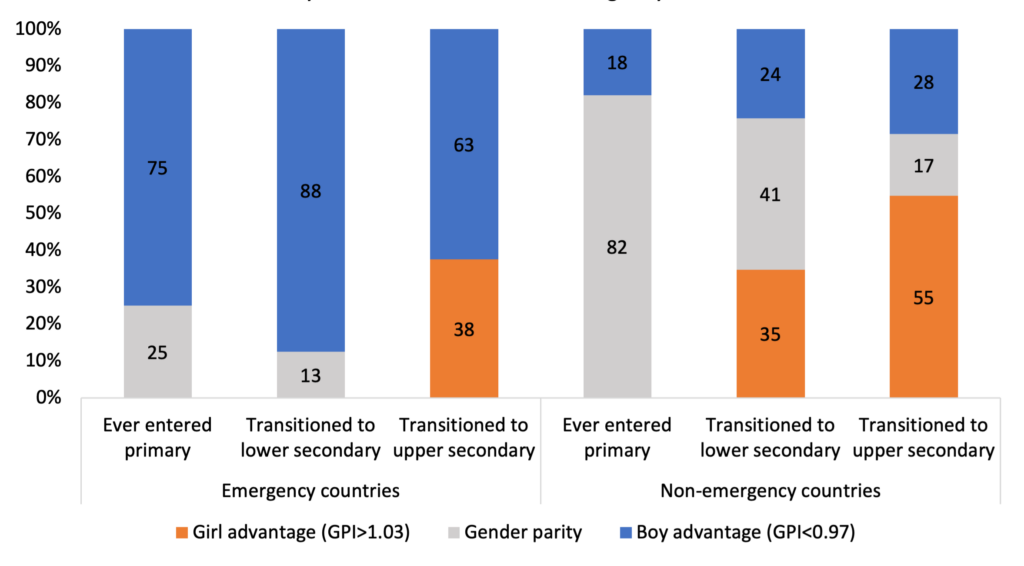

In emergency countries, disparities in girls’ and boys’ educational trajectories are stark.

In addition to looking at countries by region, it is also possible to group countries according to whether they are designated “emergency” countries or not (Fig. 4). Emergency countries are ones in which there are disruptions to everyday living because of conflict or natural disasters. In these emergency countries, boys started out having an advantage, and retained this advantage throughout the transition to lower and upper secondary school. Of note, however, girls gained the advantage in 38 per cent of emergency countries by the transition to upper secondary, whereas they did not have an advantage in any countries during either primary or lower secondary school. In non-emergency countries, alternatively, children’s educational journeys began in most instances with gender parity, but girls gradually attained the advantage in the majority of countries as they transitioned to upper secondary school, although boys gained the advantage in a number of countries as well.

Percentage of countries with gender parity in school enrollment, girl advantage, or boy advantage, by level of education and emergency status

The findings from the education pathway gender analysis reveal several important points. One is that across most countries (80 out of the 103), girls and boys began their education on par with one another, at least as far as entering primary school is concerned. The other is that although girls did not start out having an advantage in any country, as they transitioned to lower and upper secondary school, girls gradually surpassed boys in over half the countries analyzed. More boys also gained the advantage as they progressed through school in a number of countries, although the observed increase was much smaller. Boys tend to have a particularly strong advantage in emergency countries, especially in primary and lower secondary school.

While the great strides that girls have made in their educational journeys in many countries is something to be acknowledged, driven in part by the investments made over the past 25 years in girls’ education, it remains important to ensure that all children, regardless of gender, have equal opportunities to learn. This is especially true given the challenges that the COVID-10 pandemic has posed to education. Further data collection and analysis are needed to understand the gender-differentiated impacts of the pandemic on girls’ and boys’ educational trajectories so that appropriate policy responses can be implemented.

- Share this post on Twitter

- Share this post on LinkedIn

- Share this post on Email

Latest articles

- Evidence to Policy

- Publication & data launches

What about the boys? Addressing educational underachievement of boys and men during and beyond the COVID pandemic

Jaime saavedra, michel welmond, laura gregory.

High-income countries know this all too well: no matter the grade or subject, boys have been underperforming in school compared to girls, and men have become less represented in higher education. It’s a phenomenon that has been acknowledged in the literature of many high-income countries for decades, and now increasingly observed among middle-income countries. With the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education and the deepening of existing inequalities, it is important and timely to better understanding the underachievement of boys and men, in addition to girls and women. Recent evidence highlights the significant effect of school closures on girls including the estimated 10 million additional girls at risk of child marriage over the next decade. Less is known about the effect on boys due to lacking global research on factors related to their underachievement prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new report from the World Bank takes stock of educational underachievement among boys and men and the contributing factors. The report examines three forms of educational underachievement among boys and men:

- Low levels of participation in education

- Low rates of education completion or graduation

- Low student learning outcomes

How extensive is educational underachievement among boys and men?

In every region of the world, and in almost every country, boys are more likely than girls to experience learning poverty , being unable to read and comprehend a simple text by the age of 10. The differences are substantial in some countries, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and among middle-income countries. For example, in lower-middle-income countries, the learning poverty rate for boys is 56 percent, compared to 47 percent for girls.

While girls’ underrepresentation in secondary and tertiary education remains a significant issue in some, particularly low-income, countries, there are more than 100 countries in which fewer boys/men than girls/women are enrolled in and complete secondary and higher education. Of the 152 countries with data, 116 (76%) have lower tertiary education enrollment ratios among men compared to women. Not only are men less likely to participate in tertiary education, but they are also less likely to finish their programs of study. The overall disruption to enrollment and learning from the COVID-19 pandemic is well documented in many countries, and it can be expected that educational challenges will be especially experienced by certain subgroups of students, including boys and men who are underachieving.

Why does it matter?

Educational underachievement of any group has critical implications for individuals and for countries in their efforts to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all (Sustainable Development Goal 4) and to build human capital . If there were no underachievement of boys across the world — that is, if boys had the same learning-adjusted years of schooling as girls — a child's long-term annual productivity would be, on average, 1.3 percent higher. Maintained over the course of a decade, this represents an increase in total production of 13.9 percent. In MENA, this would be as high as 33.9 percent. These differences are particularly important considering that there is a strong relationship among boys and men between educational underachievement and economic and social disadvantage.

As the COVID pandemic subsides, addressing increased inequality will be a priority if education development strategies are to be put back on track. The specific inequality challenge may bear out to be primarily gender related (regarding either boys or girls) in some countries, and thus will require a specific focus.

What explains educational underachievement among boys and men?

The explanations are wide and varied. The report uses three lenses to examine the key factors:

- Labor market influence. Incentives to continue education can be different for men and women. Men may have (or have had) the possibility of finding work without education. While returns to education should generally lead boys and men to continue their studies, this is often not the case. Falling behind and early failures in their education may narrow the potential of boys and men to access higher levels of education, pointing to the importance of promptly addressing potential barriers.

- Social norms. Prevalent social norms that dismiss the importance of education for boys and men provide some of the answers. Much research on the effect of social norms has focused on the concept of “hegemonic masculinity”, which encompasses a set of social norms (for example, emphasizing sexuality, physical strength, and social dominance) that can be at odds with those that are conducive to academic success. Among the theories on how family affects social norms, much has been written about “fatherless” households, where boys tend to experience more educational underachievement, and girls’ educational performance is affected significantly less.

- Characteristics of the education process. Education systems that emphasize the specific needs of each student and that create an inclusive environment free of gender stereotyping benefit both boys and girls. Attention needs to be paid to those specific issues and contexts in educational settings that affect and can mitigate the underachievement of boys and men.

The report finds that poverty accentuates educational underachievement for all, but particularly for boys and men. Socially disadvantaged boys and men are disproportionately affected by educational underachievement. Boys have also been found to be more sensitive to certain factors of school climate or classroom environment, such as disciplinary problems and lacking student assessment and teacher accountability and appraisal.

What has been done about it?

While the issue has gained attention in high-income countries, very few of those have put in place systemwide policies or programs to address it.

Examples of interventions include quotas for entry to university, raising awareness of work opportunities after graduation, and technical education leading directly to the labor market. However, these interventions have had mixed results. Efforts to modify the influence of social norms have included attempts to create a counter-offensive through peer groups, clubs, parenting programs, and teacher training on social norm. Interventions that target the quality of education, particularly the ability of teachers to motivate and find connections to students’ lives, hold high expectations, and focus on individual talents and needs, appear to be crucial for underachieving boys, while also benefiting underachieving girls. These go beyond any idea of a “boy-friendly” pedagogy, instead recognizing that both boys and girls benefit when learning is high-quality, evidence-based, and scientifically grounded.

Where to now?

Educational underachievement among boys and men requires the attention of policymakers, development agencies, academics and analysts, and the public. This includes concerted efforts to improve the educational experience of all learners, with methods that engage and motivate those at the lower end of achievement — predominantly boys — while also being effective for all students.

More research is needed of the issues of male educational underachievement at the global and national levels, including in-depth country studies, thematic studies (such as on disadvantage, higher education, and the effect of labor markets on educational choices), and applied research to determine the effectiveness of interventions to address educational underachievement.

Research on gender has often viewed girls’/women’s and boys’/men’s achievement in isolation from one another, while a deeper understanding could be gained by studying them together. A more holistic view of gender could yield a complete and useful understanding of education underachievement, thereby avoiding an either/or approach to policies and programming. For example, removing gender stereotypes from curricula materials requires a consideration of prevalent stereotypes of both males and females. Likewise, developing strong readers requires investments in levelled reading material that is ample, varied, and pique the interests of both boys and girls. Taking a more holistic approach to gender and educational underachievement will be particularly important as education systems worldwide develop policies and strategies to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Accelerate Equality.

Related Link:

- Report: Educational underachievement among boys and men

Human Development Director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank

Global Director, Gender

Lead Education Specialist

Senior Education Specialist

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Five key debates for the future of education

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Anant Agarwal

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

How do we best educate the students of tomorrow? What we teach our children – and how we teach them – will impact almost every aspect of society, from the quality of healthcare to industrial output; from technological advances to financial services. Our Global Agenda Council experts join the debate to offer various visions of how education may evolve, and how governments, educators, employers and students will need to adapt to keep pace with the bewildering array of possibilities that will shape all of our futures.

The impact of technology

Rapid and dramatic developments in technology, the internet and online learning have outpaced projections from just a few years ago. And while the concept of internet-enabled study is hardly a new phenomenon, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) could be the spark that ignites significant changes in the way the world teaches and learns. That’s the view held by Professor Anant Agarwal, CEO of edX, the online learning destination founded by Harvard and MIT.

“We’re seeing a revolution in education as we speak,” says Professor Agarwal, “Technology is casting a spotlight on the innovation of massively open courses, of dynamic new study options that are available to everyone, regardless of background or location.”

Flexible, mass stream and open-source learning, he argues, will revolutionize the landscape of education. “In the future, you could go to university having done the first year of content online. You could then come and have the campus experience for two years, before going on to get a job in the industry where you become a continuous learner for the rest of your life.”

Professor Agarwal believes that this flexibility, combined with instant online feedback, will vastly improve learning outcomes. But this dynamism also extends beyond a mere expansion of study options.

The evolution of MOOCs will not only have a profound effect on how we teach in the future, but who we teach, says Professor Agarwal. MOOCs and their technology could be used to ‘virtualize’ education on a mass scale, delivering low-cost learning opportunities to developing countries that have skipped what he calls the “landline generation” – countries such as India and Kazakhstan, and Africa’s emerging economies where mobile phones are the primary form of communication. It is, he says, much easier to connect thousands of people to the internet and provide them with subsidized tablets, than to build hundreds of bricks-and-mortar campuses.

Professor Agarwal believes that open source MOOCs will adapt organically and democratically to the specific needs of the developing world. The use of the open source model will promote universal access to study materials, setting each MOOC in competition with itself as well as anyone else who wishes to challenge and modify its platforms.

“When something is this powerful and this game-changing, we need to be steering it as a non-profit venture, and even move beyond the concept of non-profit. It should be a platform that everybody can take, and evolve in the way they see fit. Why should any one organization be in charge of it?” he says.

Increasing globalization

Not everyone is convinced that access to MOOCs will prove to be a universal solution to the world’s education challenges. Technology and online learning have exponentially extended the reach of the humble classroom – but this is a trend that Professor Tan Chorh Chuan, President of the National University of Singapore, approaches with some caution.

In Professor Tan’s view, MOOCs distributed by well-established universities, while undoubtedly having a positive impact, fail to take into account the heterogeneous nature of education. And this is particularly true in the context of developing countries.

“There is unlikely to be a panacea in terms of a form of education which would meet different needs worldwide,” says Professor Tan. “Another disadvantage is that you could end up disempowering local education institutions.”

He envisions a more symbiotic approach: “For example, a MOOC provider could work with a number of universities in Africa or in India in order to customize or contextualize the learning materials. They could also work directly with the educators so that face-to-face components could be developed.”

As technology continues to replace routine jobs, education must adapt, says Professor Tan. Modular and online learning will play a significant role in this, but are no substitute for a holistic learning experience.

Outside of developed countries, he feels that branch campuses and partnerships with more established institutions can offer several benefits. “This kind of internationalization in situ provides a new and quite interesting way in which higher education capacity and quality can be built up in the developing world.”

The unification of standards – a question of governance

If education is set to become increasingly globalized, who should govern the models that are used in the future? And should we be looking to build a universal set of standards, one that can be co-opted by universities, industry, MOOCs and other online learning platforms?

Professor Tan warns against establishing such a hegemony. He argues that diversity of educational models, even within a given country, is something that should be encouraged: differentiation helps to equip educators with more resilient ways to adapt to the unpredictability of education in the future.

“I think adaptation is very important,” he says. “I would also say that experimentation actually allows us to learn more and more about what works and what doesn’t. We still don’t know enough about learning psychology and how people best acquire knowledge in a very rapidly-changing environment. I think trying to standardize that might actually have a negative impact on education.”

Dr Shirley Ann Jackson, President of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, envisions a new model – what she calls the “New Polytechnic” – of working and learning that is required in this “data-driven, computationally powered, globally networked era.”

Dr Jackson believes that the future of education will be a collaborative effort, with universities, businesses and governments working more efficiently together to “use and link the capabilities of advanced information technologies, communications and networking”.

“The way we connect and are connected by communication devices, medical devices, security devices and more has resulted in an explosion of data,” explains Dr Jackson. “Data is the new natural resource of the 21st century. The great challenge and opportunity is how to mine, manage, preserve and protect the data to ensure it is being harnessed to its full potential.”

“The aim of the ‘New Polytechnic’ is for educational institutions to work across disciplines, sectors and regions to harness the advanced technologies, the communications networks, and global interconnectivity to address our global challenges with energy security, water, health, environmental and national security, and the linked challenges of climate change and sustainability – animating and supporting strong economic systems and financial markets,” she says.

At Rensselaer, changes are already underway to realise Dr Jackson’s vision, which, she says, will equip the next generation with more intellectual agility. So while the internet itself will benefit from more structuring, students, she argues, must be taught to be adaptable. They must develop what she calls “multicultural sophistication” and they must have a global view.

Dr Jackson believes it is vital to harness this approach to build a strong innovation ecosystem.

The internet, Dr Jackson notes, is the new library. As with online platforms such as MOOCs, connectivity is required for students to reach their full potential.

“If 60% of the world is still not online then there is a question about addressing the great challenges of our time,” she says. “In emerging economies, which is where a lot of these challenges play out, if one wants to try to think about a data-driven approach, then one has to think about what barriers exist. Is there broadband access? Is there even electricity?”

In this manner, even the most advanced of educational ideas may be anchored to more prosaic facilities and needs.

A different approach: Will commoditization benefit education?

Of course, education should be seen as a need in itself. Technology has undoubtedly made the world a smaller place and, in the 21st century education is rightly considered a basic human right. Unfortunately, this classification doesn’t negate the need for financial backing; somewhere along the chain, educators, researchers and platforms must be funded.

Dr Jackson is somewhat cautious, however, about initiatives that bow to the needs of industry for specific skills training, without providing a broader education. She believes that education cannot purely be demand-driven, as these demands are subject to constant change; locking people into a specific skills framework will leave them poorly prepared to adapt to these changes.

Dr Mona Mourshed, Senior Partner with McKinsey & Company, believes a more radical approach to education must be adopted if the world is to keep pace with future demand for skilled workers. We are, she posits, migrating towards the curation of education – an environment of accelerated learning, based upon a modularized approach. She echoes Professor Agarwal’s theory that the students of the future will spend less time on traditional campuses.

“I think universities will no longer be four-year experiences,” she says. “Furthermore, I believe that vocational options will no longer necessarily be a two-year experience. We will be talking about eight to twelve weeks of experiences to attain particular skills. Then in the workplace, as you get ready to take your next step, you get the next module. This process can be regarded as a partnership between the employer and the education provider.”

Dr Mourshed believes that competency-based assessments to acquire what she terms “just-in-time skills”, acquired via informal learning, will allow people to access education wherever and whenever they like. This modularization will disrupt traditional attitudes towards current educational models.

Furthermore, Dr Mourshed’s vision of a modular, skills-based education suggests that industry – rather than traditional institutions – will play a greater role in driving standards, and thus funding education in the future. This will not stem from a desire, on the part of employers, to shape education policy; rather, it’s about responding to the need for individuals to have more diverse skills.

“Employers are changing the reality of education on the ground,” says Dr Mourshed. “They are giving jobs on the back of that, so I think it’s more the case that policy will follow these experiments.”

So, will universities disappear? “No, of course they won’t. But we will increasingly see a share of the student population opting for a very different education experience.”

Education, she says, must not stagnate if we are to get young people to a higher level of productivity at a faster rate than has traditionally been the case.

The changing, but recognizable, face of future education

Education is constantly adapting to societal needs, and this transformation will undoubtedly gather momentum in the years to come. Technology, MOOCs and industry will all play a unique role in this evolution, and while traditional institutions may face challenges in the future, it’s likely they will still form the bedrock of learning and influence how the world teaches and learns.

The answer, in Dr Jackson’s eyes, lies in finding a sense of balance. While the future she envisions for education will certainly be more technologically driven, it must still be so organic, interactive, and experiential as to allow students to mature and be creative, too.

“Technology is not going to replace students in a lab or classroom doing actual physics or biological science experiments, and studying living things,” she says. “It is not going to replace the socialization and the maturation that they go through as part of their studies.

“We do not want to take an existing narrow, restricted education model and simply replace it with another one. That’s something we should always remember.”

The Outlook on the Global Agenda 2015 Report is now live.

This is an extract from the World Economic Forum’s Outlook on the Global Agenda 2015 report , drawing on interviews with GAC members Anant Agarwal, Tan Chorh Chuan, Shirley Ann Jackson and Mona Mourshed.

Authors: Professor Anant Agarwal is CEO of edX, the online learning destination founded by Harvard and MIT. Dr Tan Chorh Chuan is Professor of Medicine and President of the National University of Singapore. Dr Shirley Ann Jackson is the President of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Dr Mona Mourshed is Senior Partner with McKinsey & Company.

Image: Students take notes from their iPads at the Steve Jobs school in Sneek August 21, 2013. REUTERS/Michael Kooren

Share this:

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How universities can use blockchain to transform research

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

Empowering women in STEM: How we break barriers from classroom to C-suite

Genesis Elhussein and Julia Hakspiel

March 1, 2024

Why we need education built for peace – especially in times of war

February 28, 2024

These 5 key trends will shape the EdTech market upto 2030

Malvika Bhagwat

February 26, 2024

With Generative AI we can reimagine education — and the sky is the limit

Oguz A. Acar

February 19, 2024

How UNESCO is trying to plug the data gap in global education

February 12, 2024

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

2. teachers’ views of current debates about what schools should be teaching.

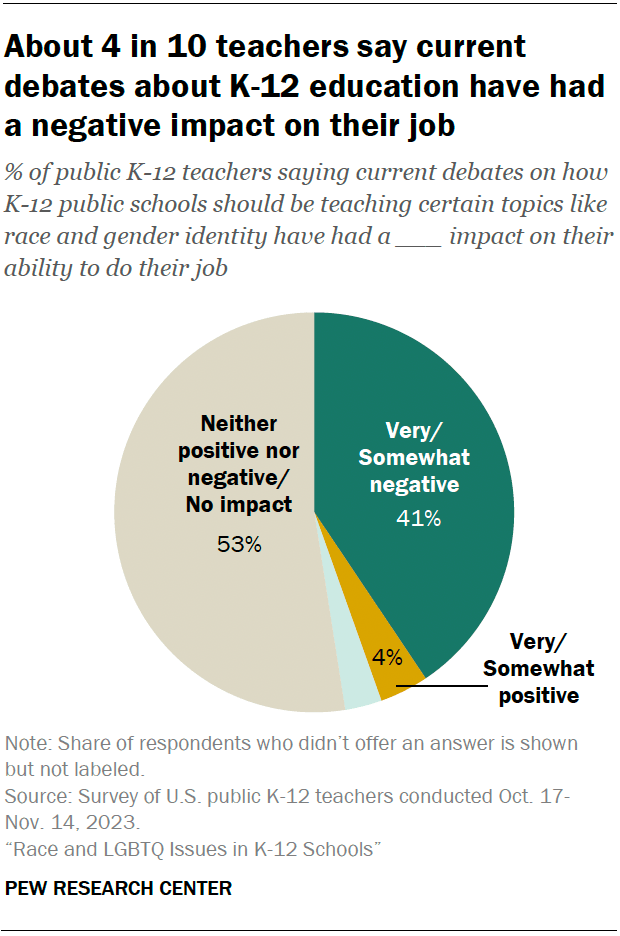

We asked teachers what type of impact current debates about how public schools should be teaching about topics like race and gender identity have had on their ability to do their job.

A sizeable share of public K-12 teachers (41%) say these debates have had a negative impact on their ability to do their job.

Just 4% say these debates have a positive impact, while 53% say the impact has been neither positive nor negative or that these debates have had no impact.

Similar shares of Democratic (44%) and Republican (40%) teachers say these debates have had a negative impact. But Republican teachers are more likely than Democratic teachers to say the impact has been neither positive nor negative or that there’s been no impact (58% vs. 51%).

Secondary school teachers are more likely than elementary school teachers to say the impact has been negative (45% vs. 36%). Among secondary school teachers, those teaching English or social studies are especially likely to say this compared with those teaching other subjects (55% vs. 38%).

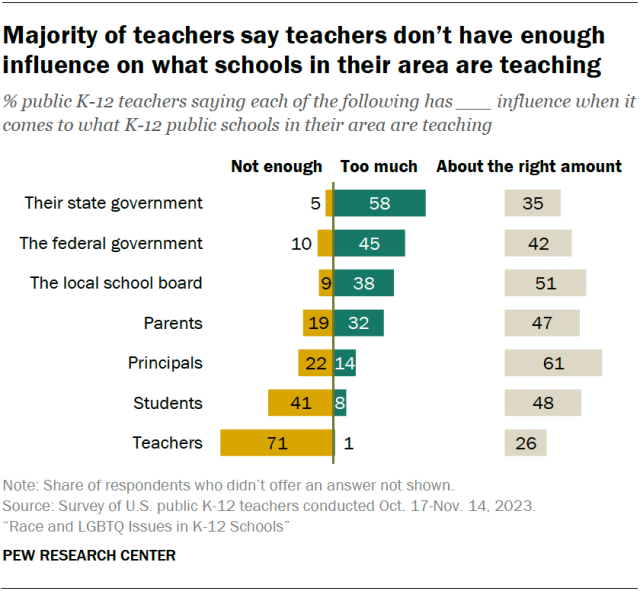

Influence over curriculum

We asked teachers about the amount of influence different groups have over what K-12 public schools in their areas are teaching.

Most teachers (71%) say teachers themselves don’t have enough influence.

Teachers are also more likely to say students and principals don’t have enough influence than to say these groups have too much influence. Still, 61% say principals have about the right amount of influence, and about half say the same about students.

In turn, a majority of teachers (58%) say their state government has too much influence over what K-12 public schools in their area are teaching.

More also say the following groups have too much influence than say they don’t have enough influence:

- The federal government (45% say too much, while 10% say not enough)

- The local school board (38% vs. 9%)

- Parents (32% vs. 19%)

When we asked parents of K-12 children a similar question in fall 2022, a far smaller share (30%) said teachers don’t have enough influence. Another 12% said they have too much and 42% said it’s about right. In the parents survey, we also offered a “not sure” option, which 15% of parents selected.

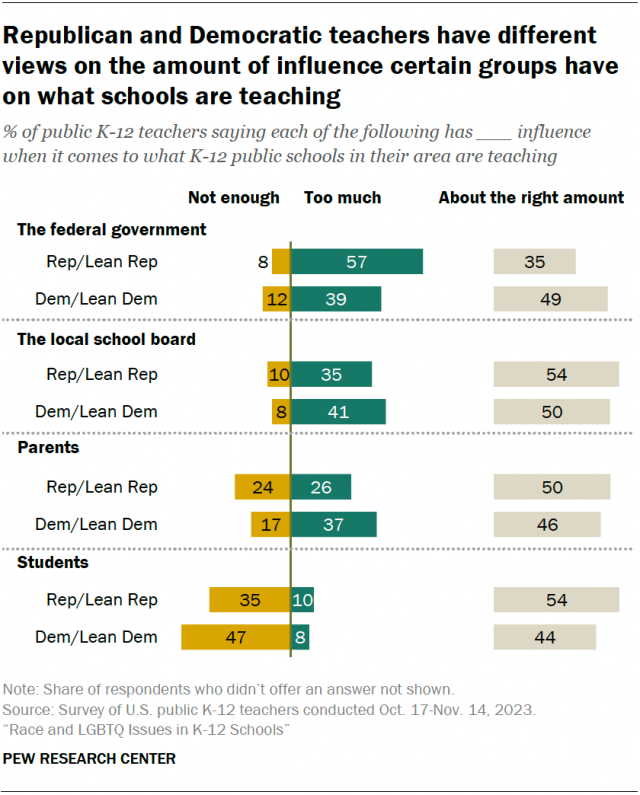

Partisan differences

As is the case among parents, teachers’ views on how much influence certain groups have on what schools are teaching vary by party.

Democratic teachers are more likely than Republican teachers to say each of the following has too much influence:

- Their local school board (41% vs. 35%)

- Parents (37% vs. 26%)

For their part, Republican teachers are more likely than Democratic teachers to say the federal government has too much influence (57% vs. 39%).

A larger share of Democratic teachers (47%) than Republican teachers (35%) say students don’t have enough influence on what schools are teaching.

Social Trends Monthly Newsletter

Sign up to to receive a monthly digest of the Center's latest research on the attitudes and behaviors of Americans in key realms of daily life

Report Materials

Table of contents, ‘back to school’ means anytime from late july to after labor day, depending on where in the u.s. you live, among many u.s. children, reading for fun has become less common, federal data shows, most european students learn english in school, for u.s. teens today, summer means more schooling and less leisure time than in the past, about one-in-six u.s. teachers work second jobs – and not just in the summer, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Privacy Policy

- Join Our Groups to be Guided in your Admission Search

SureSuccess.Ng Your No 1 School Information Hub

- Top 10 Benefits of Rephraser.co for Boosting Productivity

- How to a Write Composition [With Samples and Templates]

- How to Transfer Airtime on Airtel in 2024

- How to Check MTN Data Balance for all Bundles [Updated]

Public School is Better than Private School Debate

- Limits in Calculus: Definition, Rules, Steps, and Examples

- The Right UNN Clearance Documents for Newly Admitted Students [Fully Explained]

- How to Write Dedication for Project [Samples & Templates]

A Memorable Day in My Life Essays 150, 200, 250 Words

- How I Spent my Last Holiday Essays 100, 150, 200, 450 Words

Male Child is More Important than a Female Child Debate

Henry Divine 2 Comments

Table of Contents

Meaning of Debate

Debate is like a friendly argument where people share their opinions about something. They take turns talking, trying to convince others that their point of view is the best. It’s a way to discuss and understand different sides of an issue.

So the goal of a debate is not necessarily to produce a winning side. Rather, it is to extensively discuss an issue from different perspectives with the aim of understanding it holistically.

In the next few sections, I will show you some of the points people raise when they argue that a male child is more important than a female child in a family. I will also give you some opposing points with which others argue against the motion. Thereafter, I will give you sample debates on the topic as a guide to crafting your own if you need to.

Read Also: Apology Letter to School Principal: Writing Guide, Format & Samples

Male Child is more Important than a Female Child Debate

Let’s look at the points with which you can either argue for the motion or against it.

Points Arguing for the Motion which states that a male child is more important than a female child

- The male children carry the family name from generation to generation, so that the family name and heritage does not die.

- Male children are usually the bread winners and overall providers in the family both nuclear and extended.

- The male child takes over from his father when he is no more.

- Male children are stronger than their female counterparts physiologically. So the family depends on them to take care of strenuous house chores.

- Male children are cheaper and easier to raise when it comes to hygiene and clothing.

- Traditionally, there are roles that are only reserved for males in the society.

- Some cultures just have inexplicable preference for male children. The reason is not far from wanting a male heir to sustain the family name and secure the family’s inheritance and future.

Boy is Better than Girl Quotes

“A boy comes to me with a spark of interest, I feed the spark and it becomes a flame. I feed the flame and it becomes a fire. I feed the fire and it becomes a roaring blaze.” ~ Cus D’Amato. “Boys are sent out into the world to buffet with its temptations, to mingle with bad and good, to govern and direct – girls are to dwell in quiet homes among few friends, to exercise a noiseless influence.” ~ Elizabeth Missing Sewell “BOYS are like alcohol, you throw them up when you’ve had too much. GIRLS are like coffee, you throw them away when they are not HOT ANYMORE.” ~ Unknown “Boys insult each other, but they really don’t mean it. Girls compliment each other but they don’t mean it either.” ~ Unknown

Read Also: Top 50 Social Media Sites in the World

Points Arguing Against the Motion which states that a male child is more important than a female child

- In the face of current harsh economic realities, female children contribute to the family’s economic stability through different income-generating activities.

- Female children are more useful at home in terms of helping around with chores.

- Most female children turn out to be more responsible, more reliable and even more sensible.

- In terms of education, female children are more important than their male counterparts because if you educate a male child you educate just one person but when you educate a female child you educate the nation. The reason is because they will impact that knowledge to their children, neighbors and so on.

- A son is a son until he gets a wife. But a daughter is a daughter all of her life.

- Female children provide social security to their parents in their old age by taking care of them.

- Female children form alliances and strengthen social bonds between families through marriage.

Girl is Better than Boy Quotes

“I don’t think women are better than men, I think men are a lot worse than women.” —Louis C. K. “Once made equal to man, woman becomes his superior.” —Socrates “I think women are foolish to pretend they are equal to men; they are far superior and always have been.” —William Golding “You see a lot of smart guys with dumb women but you hardly ever see a smart woman with a dumb guy.” —Erica Jong

A Sample Debate Supporting the Motion that Male Child is More Important than a Female Child Debate

Good morning, Mr. Chairman, Panel of Judges, accurate time-keeper, co-debaters, Ladies and Gentlemen. I am Prince Mojeed representing SSS II. I am here to support the motion that states, “A male child is more important than a female child.” Here are my strong reasons.

Firstly, male children play a crucial role in carrying forward the family name and heritage from generation to generation. It is through them that the lineage remains intact, ensuring that the family’s legacy endures through time.

Secondly, in many societies, male children are traditionally seen as the primary breadwinners and providers for both nuclear and extended families. Their role as providers is essential for the economic stability and well-being of the family unit.

Furthermore, the male child often assumes the responsibility of taking over from his father when he is no longer able to fulfill his duties. This continuity ensures the smooth transition of leadership and the preservation of family traditions and values.

Physiologically, male children are generally stronger than their female counterparts, making them better suited for strenuous household chores and physical labor. Their strength and endurance are relied upon for tasks that require physical exertion which is often needed for the smooth functioning of the family unit.

Lastly, when considering the economic aspect, it is often believed that male children are cheaper and easier to raise compared to female children. Parents don’t need to spend money buying pads, wigs, bras, weavons, nails, and so on.

In conclusion, the importance of male children cannot be understated, as they play multifaceted roles in upholding family heritage, providing economic stability, assuming leadership positions, contributing to physical labor, and easing the financial burden on the family. For these reasons, we firmly support the motion that a male child is more important than a female child. Thank you.

A Sample Debate Opposing the Motion that Female Children are more Beneficial to their Parents than Male Children

Good morning, Mr. Chairman, esteemed Panel of Judges, time-keeper, fellow debaters, Ladies, and Gentlemen. I am Prince Mojeed representing SSS I, and I strongly oppose the motion that “female children are more beneficial to their parents than male children.”

It is widely recognized that male children offer more benefits to their parents compared to female children. Here’s why:

Firstly, male children are generally stronger than females, leading them to undertake more strenuous tasks and work harder. While some argue that females excel in the kitchen, it’s important to note that male children can also contribute effectively, depending on how they are trained. However, tasks like splitting firewood with an axe are typically reserved for male children due to their physical strength.

Secondly, maintaining female children in the family tends to be more costly. Male children are usually content with fewer clothing items, while females often request numerous additional items, leading to higher expenses for their upkeep.

Thirdly, female children typically change their surname upon marriage, relinquishing their maiden name. In contrast, male children retain and uphold their family name throughout their lives, ensuring its continuity.

In many cultures, male children are regarded as the backbone of the family, inheriting their father’s responsibilities and upholding the family’s reputation. Conversely, female children marry into another family, shifting their focus to their husband’s household.

Lastly, the notion that female children care for their parents in old age is not entirely accurate. Male children often take charge of their father’s household, maintaining close ties with their parents and addressing their needs firsthand.

In conclusion, I believe that the arguments presented demonstrate the greater benefits male children offer to their parents compared to female children. Thank you.

Read Also: Career Guide: 5 ways to choose a bad (wrong) Career

Final Thoughts

Don’t forget that debate is like a friendly battle of ideas that helps both the participants and audience to understand different viewpoints, learn new things and improve their communication skills. So, whether you are proposing or opposing, agreeing or disagreeing, debating is a great way to grow and connect with others.

If you got value from this post, you can help us to spread it. Share with friends on Social Media . Just scroll down to see the Facebook and Twitter and WhatsApp buttons. Thank you so much!

Share this:

Get in touch with us.

Follow us on WhatsApp via WhatsApp or Telegram or Facebook

Like and Follow us on Facebook @SURE SUCCESS NG

Join our 2024 JAMB Tutorial Classes on WhatsApp or Telegram or Facebook

Join our Aspirants Facebook Group @JAMB Tutorials & Updates

UNN Aspirants and Students, Join MY UNN DREAMS (MUD)

About Henry Divine

Some few decades ago, making the choice between public school and private school was very …

We are continuing on our series on Essay Writing for primary school pupils and secondary …

I much appreciate as you give us new knowledge based on a debate

You are welcome.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of new posts by email.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A DISCURSIVE SPECTRUM: The Narrative of Kenya’s ‘Neglected’ Boy Child

Associated data.

In this article, I examine a narrative that on the surface could be backlash to gender equality efforts: that after years of policy attention to girls, Kenya’s “boy child” has been neglected. Through a content analysis of Kenyan online newspaper texts spanning the past two decades, I chart the evolution of this discourse, finding that it was present as early as 2000, intensified around 2010, and began to produce concrete actions around 2013. I argue that the narrative is a reaction to expanded women’s rights, but not always in the sense of negative backlash. Some boy child claims-makers were indeed concerned with a decline in men’s power. However, others, mostly women, used the boy child narrative to redirect attention to issues that profoundly affect the well-being of women such as violence and the struggle to find a partner. These results point to the value of a discursive spectrum approach for analysis of potential backlash to gender equality as well as discussions around policy attention to boys and men.

In recent years, scholars have increasingly begun to study the question of backlash against gender equality, exploring the national contexts as well as transnational dynamics that foster such reaction ( Corredor 2019 ; Korolczuk and Graff 2018 ; Paternotte and Kuhar 2017 ; Lodhia 2014 ). From Eastern Europe to Latin America, the global Right—largely comprised of religious and political figures and organizations—has been found to employ a “rhetorical counterstrategy” that seeks to discredit feminist ideas and policy proposals ( Corredor 2019 , 616). It is no coincidence that a backlash discourse has emerged as gender equality has advanced globally: a prerequisite for the formation of a countermovement is some level of success from the movement it is opposing ( Corredor 2019 ; Verloo 2018 ).

Alongside this reaction to gender equality, tensions exist within the gender and development arena about how men should be involved, both as policy-makers and beneficiaries. A growing interest around incorporating men into gender programs accompanied the shift from the women in development approach to the gender and development approach in the 1990s ( Chant and Gutmann 2000 ; Cornwall 2000 ). Although this stronger emphasis on gender relations theoretically opened up space for the greater involvement of men, the focus of gender programming has remained largely on girls’ and women’s empowerment, in part due to the rationale that this approach is “smart economics” ( Chant 2016 , 4). A parallel but distinct discourse runs in the Global North, as well as other regions such as the Caribbean, around how persistent gender inequality relates to negative outcomes for boys and men in various realms, including education, incarceration, and health ( Noguera 2003 ; Cobbett and Younger 2012 ).

In this article, I explore one gender narrative that brings together these dynamics of backlash and concern for men: that after years of focus on the girl child, the “boy child” in Kenya has been forgotten. Specifically, I ask: what explains the emergence of this narrative of neglect in Kenya, and how does it relate to women’s changing social position? Applying content analysis to two decades of online newspaper texts, I examine the problems associated with the “neglected” boy child as well as the orientations of a wide range of claims-makers to gender equality. The findings present a complex picture. Groups, all arguing that the boy child has been forgotten, hold diverse views on gender equality, ranging from those who think gender equality efforts have been excessive to those who think there is much progress to be made.

These results point to the value of a broad study of both potential backlash to gender equality and policy attention to boys and men. This framework, which I call a discursive spectrum approach, starts with narratives in the public sphere to go beyond two opposing sides, pro- and anti-equality efforts, and reveals the concerns, goals, and social positioning of a range of discursive actors. The term spectrum is not meant to imply that all contested gender discourses will involve actors ranging in their views on gender equality. Instead, it indicates a stance that such a spectrum might exist and, with discourse as an entry point, allows variation in views to emerge.

CRISIS TENDENCIES AND POTENTIAL BACKLASH IN THE GENDER ORDER

Gender dynamics at every level of society, from the individual to the institutional, are never set in stone ( Risman 2017 ). There are moments, however, when the gender order is particularly vulnerable to change. Connell (1987) referred to these moments as “crisis tendencies,” arguing that they stem from contradictions in various areas of gender relations: for example, men’s continued dominance in homes existing alongside the idea that men and women are equal as citizens. This theory—that changes in different arenas interact to shape the trajectories of the gender order as a whole—parallels Walby’s concept of a critical turning point, “an event that changes the trajectory of development onto a new path” (2009, 421). To Connell and Walby, these salient periods—crisis tendencies or critical turning points—represent a fork in the road, posing risk and opportunity for gender equality.

Indeed, history has shown that the path to a more gender equal society frequently meets with resistance. In recent years, explicitly “antigender” groups across the world have intensified their efforts to obstruct and dismantle policies aimed at gender and sexual equality ( Corredor 2019 ). But, what if opposition takes the form of a discourse that is not tethered to a particular group? And furthermore, what if a discourse—such as the boy child debate —could be backlash to gender equality but, as yet, it is premature to classify it as such? In this case, a more expansive approach, one that moves beyond the dichotomy of movement and opposition, is particularly valuable. Frameworks put forward by feminist scholars to examine debates around social problems, largely in relation to the welfare state and policy, provide a useful foundation to help develop a discursive spectrum approach. I draw especially on Nancy Fraser’s concept of needs-talk , the “disputes about what exactly various groups of people really do need and about who should have the last word in such matters” (1990, 199). Rather than study the needs themselves, Fraser called for study of how people interpret needs. Her model highlights three key moments of struggle: establishing the need as a political concern, interpreting the need, and satisfying or denying the need. At each of these points, different groups, who have varying degrees of power and resources, jostle to establish their view on a particular social need as hegemonic. A more recent wave of feminist scholars have designed new frameworks to study discourse around social problems ( Bacchi 2012 ; Lombardo, Meier, and Verloo 2009 ). Using the narrative of Kenya’s neglected boy child, I build on these theories to develop a discursive spectrum approach, where language serves as an entry point to reveal the range and complexity of attitudes to gender equality.

MEN’S DISEMPOWERMENT AND PRIVILEGE IN KENYA

British colonial rule fundamentally disrupted and shaped gender relations in Kenya. With the arrival of wage work and formal education, underpinned by the colonial administration’s beliefs about men and women’s social positions, a man as breadwinner ideal began to emerge ( Chege and Sifuna 2006 ; Ocobock 2017 ). Since the 1980s, research has shown men in Kenya failing to live up to expectations of providing financially ( Izugbara 2015 ; Mojola 2014 ; Amuyunzu-Nyamongo and Francis 2006 ; Silberschmidt 2001 ). This economic strife is largely due to declines in agricultural industries such as sugar and pyrethrum, the falling price of cash crops such as coffee, the rising cost of agricultural inputs, declining farmland in rural areas ( Amuyunzu-Nyamongo and Francis 2006 ; Silberschmidt 2001 ), and the limited, precarious, and low-paid nature of much work in urban areas ( Izugbara 2015 ).

Some scholars have argued that this schism between men’s breadwinning responsibilities and the economic reality on the ground has led to the “disempowerment” of poorer men who fall short of expectations ( Silberschmidt 2001 ; Amuyunzu-Nyamongo and Francis 2006 ). In this explanation, women strengthened their identities as they increasingly worked outside the home, leaving men “with a patriarchal ideology bereft of its legitimizing activities” ( Silberschmidt 2001 , 657). The resulting lack of self-esteem led some men to seek a combination of power and solace in alcohol, domestic violence, and extra-marital partners, with women consequently bearing much of the brunt of men’s disappointments ( Amuyunzu-Nyamongo and Francis 2006 ; Silberschmidt 2001 ).

Beyond Kenya, these tensions around socio-economic change, masculinity, and gender relations have been documented in diverse settings across sub-Saharan Africa, including in Madagascar ( Cole 2005 ), Nigeria ( Smith 2017 ) and Uganda ( Stites 2013 ). The economic travails and perceived loss of status amongst poorer men stands in contrast to the fact that men continue to disproportionately occupy positions of political and economic power in much of sub-Saharan Africa ( Bouka et al. 2017 ; World Bank 2007 ). These contrasts are stark in Kenya, where income inequality is high ( World Bank 2009 ). Though this research on masculinity and socio-economic change largely focuses on men from the lower end of the economic spectrum, the understanding that “providing” is fundamental to masculinity also extends to higher income groups and, indeed, the ability to fulfill these ideals signifies class status ( Smith 2017 ; Spronk 2012 ).

GENDER EQUALITY: MOBILIZATION AND RESPONSES

In the past few decades, Kenyan women have mobilized in diverse ways for gender equality. After the shift to a multi-party system in the 1990s, women’s organizations in Kenya were able to intensify their efforts to advance women’s political position, focusing particularly on integrating key provisions into the constitution that was eventually passed in 2010 ( Tripp, Lott, and Khabure 2014 ). The new constitution marked a turning point for gender equality in Kenya, dramatically increasing the numbers of women in politics. However, one of its major victories—a provision that no more than two-thirds of any publicly elected body may be the same gender—has yet to be fully enforced and women politicians continue to face violence and intimidation ( Bouka et al. 2017 ; Kamuru 2019 ). Women also have formed profession-based activist organizations such as the Federation of Women Lawyers, which has provided legal assistance to women on issues such as child custody and landownership as well as advocated for legal reforms, including around the two-thirds gender rule. More recently, social media has offered a new platform for feminists and women’s rights activists to protest and voice their opinions, including drawing attention to brutal cases of violence against women ( Nyabola 2018 ).