- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters & Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing & Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 10, 2024 11:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

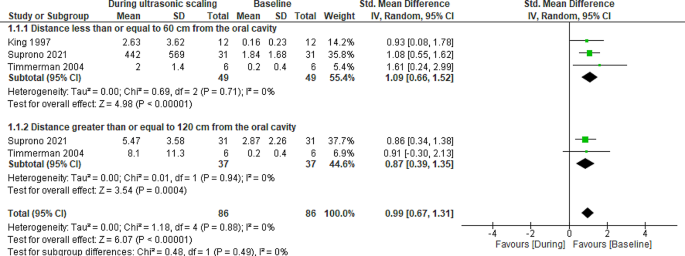

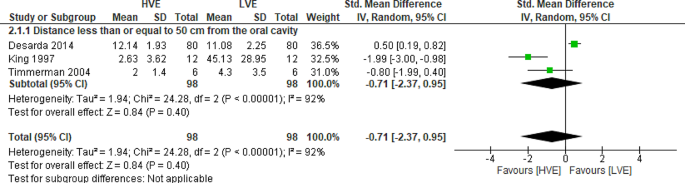

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

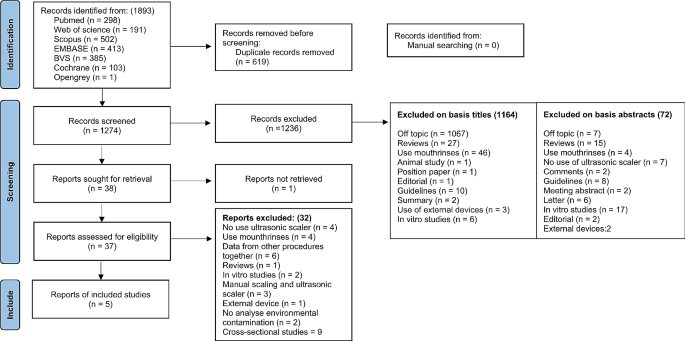

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

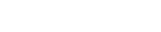

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

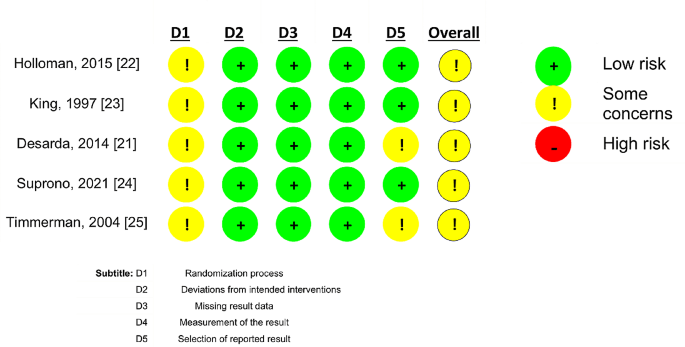

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

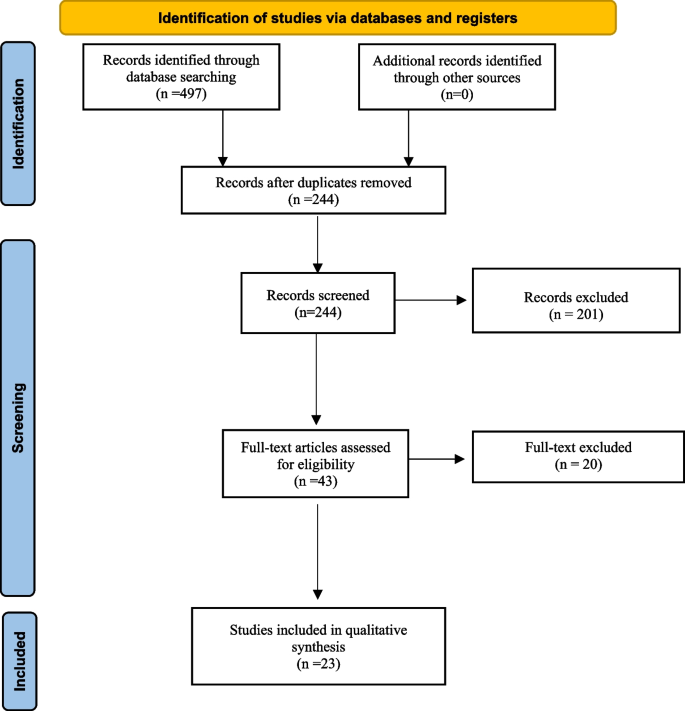

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Systematic Reviews

- Introduction to Systematic Reviews

Traditional Systematic Reviews

Meta-analyses, scoping reviews, rapid reviews, umbrella reviews, selecting a review type.

- Reading Systematic Reviews

- Resources for Conducting Systematic Reviews

- Getting Help with Systematic Reviews from the Library

- History of Systematic Reviews

- Acknowledgements

Systematic Reviews are a family of review types that include:

This page provides information about the most common types of systematic reviews, important resources and references for conducting them, and some tools for choosing the best type for your research question .

Additional Information

- A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies This classic article is a valuable reference point for those commissioning, conducting, supporting or interpreting reviews.

- Traditional Systematic Reviews follow a rigorous and well-defined methodology to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research articles on a specific topic and within a specified population of subjects

- The primary goal of this type of study is to comprehensively find the empirical data available on a topic, identify relevant articles, synthesize their findings and draw evidence-based conclusions to answer a clinical question

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions provides direction on the standard methods involved in conducting a systematic review. It is the official guide to the process involved in preparing and maintaining Cochrane systematic reviews on the effects of healthcare interventions.

- JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis The JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis is designed to provide authors with a comprehensive guide to conducting JBI systematic reviews. It describes in detail the process of planning, undertaking and writing up a systematic review using JBI methods. The JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis should be used in conjunction with the support and tutorials offered at the JBI SUMARI Knowledge Base.

These are some places where protocols for systematic reviews might be published.

- PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO is an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care, welfare, public health, education, crime, justice, and international development, where there is a health related outcome. Key features from the review protocol are recorded and maintained as a permanent record. PROSPERO aims to provide a comprehensive listing of systematic reviews registered at inception to help avoid duplication and reduce opportunity for reporting bias by enabling comparison of the completed review with what was planned in the protocol.

- Guidance Notes for Registering A Systematic Review Protocol with PROSPERO

- OSF Registries Open Science Framework (OSF) Registries is an open network of study registgrations and pre-registrations. It can be used to pre-register a systematic review protocol. Note that OSF pre-registrations are not reviewed.

- OSF Preregistration Initiative This page explains the motivation behind preregistrations and best practices for doing so.

- Protocols.io A secure platform for developing and sharing reproducible methods, including protocols for systematic reviews.

- PRISMA 2020 Statement The PRISMA 2020 Statement was published in 2021. It consists of a checklist and a flow diagram, and is intended to be accompanied by the PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration document.

- Meta-analysis is a statistical method that can be applied during a systematic review to extract and combine the results from multiple studies

- This pooling of data from compatible studies increases the statistical power and precision of the conclusions made by the systematic review

- Systematic reviews can be done without doing a meta-analysis, but a meta-analysis must be done in connection with a systematic review

- Scoping reviews identify the existing literature available on a topic to help identify key concepts, the type and amount of evidence available on a subject, and what research gaps exist in a specific area of study

- They are particularly useful when a research question is broad and the goal is to provide an understanding of the available evidence on a topic rather than providing a focused synthesis on a narrow question

- JBI Manual Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews

- Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews The objective of this paper is to describe the updated methodological guidance for conducting a JBI scoping review, with a focus on new updates to the approach and development of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (the PRISMA-ScR).

- Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review This article in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education provides a comprehensive yet brief overview of the scoping review process.

Note: Protocols for scoping reviews can be published in all the same places as traditional systematic reviews except PROSPERO.

- Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols The purpose of this article is to clearly describe how to develop a robust and detailed scoping review protocol, which is the first stage of the scoping review process. This paper provides detailed guidance and a checklist for prospective authors to ensure that their protocols adequately inform both the conduct of the ensuing review and their readership.

- PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) The PRISMA extension for scoping reviews was published in 2018. The checklist contains 20 essential reporting items and 2 optional items to include when completing a scoping review. Scoping reviews serve to synthesize evidence and assess the scope of literature on a topic. Among other objectives, scoping reviews help determine whether a systematic review of the literature is warranted.

- Touro College: What is a Scoping Review? This page describes scoping reviews, including their limitations, alternate names, and how they differ from traditional systematic reviews.

- What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis This article from JBI Evidence Synthesis provides a thorough definition of what scoping reviews are and what they are for.

- The role of scoping reviews in reducing research waste This article from the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology looks at how scoping reviews can reduce research waste.

- Rapid reviews streamline the systematic review process by omitting certain steps or accelerating the timeline

- They are useful when there is a need for timely evidence synthesis, such as in response to questions concerning an urgent policy or clinical situation such as the COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Review Guidebook This document provides guidance on the process of conducting rapid reviews to use evidence to inform policy and program decision making.

- Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide This guide from the World Health Organization offers guidance on how to plan, conduct, and promote the use of rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems decisions. The Guide explores different approaches and methods for expedited synthesis of health policy and systems research, and highlights key challenges for this emerging field, including its application in low- and middle-income countries. It touches on the utility of rapid reviews of health systems evidence, and gives insights into applied methods to swiftly conduct knowledge syntheses and foster their use in policy and practice.

- Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews The Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers new, interim guidance to support the conduct of Rapid Reviews.

- Touro College: What is a Rapid Review? This page describes rapid reviews, including their limitations, alternate names, and how they differ from traditional systematic reviews.

- Umbrella reviews synthesize evidence from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses on a specific topic

- They provide a next-generation level of evidence synthesis, analyzing evidence taken from multiple systematic reviews to offer a broader perspective on a given subject

- JBI Manual Chapter 10: Umbrella reviews

- Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) Overviews of reviews (i.e., overviews) compile information from multiple systematic reviews to provide a single synthesis of relevant evidence for healthcare decision-making. Despite their increasing popularity, there are currently no systematically developed reporting guidelines for overviews. This is problematic because the reporting of published overviews varies considerably and is often substandard. Our objective is to use explicit, systematic, and transparent methods to develop an evidence-based and agreement-based reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions (PRIOR, Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews).

- Touro College: What is an Overview of Reviews? This page describes umbrella reviews, including their limitations, alternate names, and how they differ from traditional systematic reviews.

- Cornell University Systematic Review Decision Tree This decision tree is designed to assist researchers in choosing a review type.

- Right Review This tool is designed to provide guidance and supporting material to reviewers on methods for the conduct and reporting of knowledge synthesis.

- << Previous: Introduction to Systematic Reviews

- Next: Reading Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 4:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ohsu.edu/systematic-reviews

Systematic Reviews: Types of literature review, methods, & resources

- Types of literature review, methods, & resources

- Protocol and registration

- Search strategy

- Medical Literature Databases to search

- Study selection and appraisal

- Data Extraction/Coding/Study characteristics/Results

- Reporting the quality/risk of bias

- Manage citations using RefWorks This link opens in a new window

- GW Box file storage for PDF's This link opens in a new window

Analytical reviews

GUIDELINES FOR HOW TO CARRY OUT AN ANALYTICAL REVIEW OF QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) network. (Tracking and listing over 550 reporting guidelines for various different study types including Randomised trials, Systematic reviews, Study protocols, Diagnostic/prognostic studies, Case reports, Clinical practice guidelines, Animal pre-clinical studies, etc). http://www.equator-network.org/resource-centre/library-of-health-research-reporting/

When comparing therapies :

PRISMA (Guideline on how to perform and write-up a systematic review and/or meta-analysis of the outcomes reported in multiple clinical trials of therapeutic interventions. PRISMA replaces the previous QUORUM statement guidelines ): Liberati, A,, Altman, D,, Moher, D, et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Plos Medicine, 6 (7):e1000100. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

When comparing diagnostic methods :

Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM). CLAIM is modeled after the STARD guideline and has been extended to address applications of AI in medical imaging that include classification, image reconstruction, text analysis, and workflow optimization. The elements described here should be viewed as a “best practice” to guide authors in presenting their research. Reported in Mongan, J., Moy, L., & Kahn, C. E., Jr (2020). Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): A Guide for Authors and Reviewers. Radiology. Artificial intelligence , 2 (2), e200029. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.2020200029

STAndards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy studies (STARD) Statement. (Reporting guidelines for writing up a study comparing the accuracy of competing diagnostic methods) http://www.stard-statement.org/

When evaluating clinical practice guidelines :

AGREE Research Trust (ART) (2013). Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE-II) . (A 23-item instrument for as sessing th e quality of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Used internationally for evaluating or deciding which guidelines could be recommended for use in practice or to inform health policy decisions.)

National Guideline Clearinghouse Extent of Adherence to Trustworthy Standards (NEATS) Instrument (2019). (A 15-item instrument using scales of 1-5 to evaluate a guideline's adherence to the Institute of Medicine's standard for trustworthy guidelines. It has good external validity among guideline developers and good interrater reliability across trained reviewers.)

When reviewing genetics studies

Human genetics review reporting guidelines. Little J, Higgins JPT (eds.). The HuGENet™ HuGE Review Handbook, version 1.0 .

When you need to re-analyze individual participant data

If you wish to collect, check, and re-analyze individual participant data (IPD) from clinical trials addressing a particular research question, you should follow the PRISMA-IPD guidelines as reported in Stewart, L.A., Clarke, M., Rovers, M., et al. (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data: The PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA, 313(16):1657-1665. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3656 .

When comparing Randomized studies involving animals, livestock, or food:

O’Connor AM, et al. (2010). The REFLECT statement: methods and processes of creating reporting guidelines for randomized controlled trials for livestock and food safety by modifying the CONSORT statement. Zoonoses Public Health. 57(2):95-104. Epub 2010/01/15. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01311.x. PubMed PMID: 20070653.

Sargeant JM, et al. (2010). The REFLECT Statement: Reporting Guidelines for Randomized Controlled Trials in Livestock and Food Safety: Explanation and Elaboration. Zoonoses Public Health. 57(2):105-36. Epub 2010/01/15. doi: JVB1312 [pii] 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01312.x. PubMed PMID: 20070652.

GUIDELINES FOR HOW TO WRITE UP FOR PUBLICATION THE RESULTS OF ONE QUANTITATIVE CLINICAL TRIAL

When reporting the results of a Randomized Controlled Trial :

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement. (2010 reporting guideline for writing up a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial). http://www.consort-statement.org . Since updated in 2022, see Butcher, M. A., et al. (2022). Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports: The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 Extension . JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association, 328(22), 2252–2264. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.21022

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biology, 8(6), e1000412–e1000412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 (A 20-item checklist, following the CONSORT approach, listing the information that published articles reporting research using animals should include, such as the number and specific characteristics of animals used; details of housing and husbandry; and the experimental, statistical, and analytical methods used to reduce bias.)

Narrative reviews

GUIDELINES FOR HOW TO CARRY OUT A NARRATIVE REVIEW / QUALITATIVE RESEARCH / OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

Campbell, M. (2020). Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ, 368. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890 (guideline on how to analyse evidence for a narrative review, to provide a recommendation based on heterogenous study types).

Community Preventive Services Task Force (2021). The Methods Manual for Community Guide Systematic Reviews . (Public Health Prevention systematic review guidelines)

Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) network. (Tracking and listing over 550 reporting guidelines for various different study types including Observational studies, Qualitative research, Quality improvement studies, and Economic evaluations). http://www.equator-network.org/resource-centre/library-of-health-research-reporting/

Cochrane Qualitative & Implementation Methods Group. (2019). Training resources. Retrieved from https://methods.cochrane.org/qi/training-resources . (Training materials for how to do a meta-synthesis, or qualitative evidence synthesis).

Cornell University Library (2019). Planning worksheet for structured literature reviews. Retrieved 4/8/22 from https://osf.io/tnfm7/ (offers a framework for a narrative literature review).

Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade . Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3): 101-117. DOI: 10.1016/ S0899-3467 (07)60142-6. This is a very good article about what to take into consideration when writing any type of narrative review.

When reviewing observational studies/qualitative research :

STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. (Reporting guidelines for various types of health sciences observational studies). http://www.strobe-statement.org

Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=192614

RATS Qualitative research systematic review guidelines. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/qualitative-research-review-guidelines-rats/

Methods/Guidance

Right Review , this decision support website provides an algorithm to help reviewers choose a review methodology from among 41 knowledge synthesis methods.

The Systematic Review Toolbox , an online catalogue of tools that support various tasks within the systematic review and wider evidence synthesis process. Maintained by the UK University of York Health Economics Consortium, Newcastle University NIHR Innovation Observatory, and University of Sheffield School of Health and Related Research.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews . Washington, DC: National Academies (Systematic review guidelines from the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (formerly called the Institute of Medicine)).

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2022). Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly work in Medical Journals . Guidance on how to prepare a manuscript for submission to a Medical journal.

Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (International Cochrane Collaboration systematic review guidelines). The various Cochrane review groups comporise around 30,000 physicians around the world working in the disciplines on reviews of interventions with very detailed methods for verifying the validity of the research methods and analysis performed in screened-in Randmized Controlled Clinical Trials. Typically published Cochrane Reviews are the most exhaustive review of the evidence of effectiveness of a particular drug or intervention, and include a statistical meta-analysis. Similar to practice guidelines, Cochrane reviews are periodically revised and updated.

Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual of Evidence Synthesis . (International systematic review guidelines). Based at the University of Adelaide, South Australia, and collaborating with around 80 academic and medical entities around the world. Unlike Cochrane Reviews that strictly focus on efficacy of interventions, JBI offers a broader, inclusive approach to evidence, to accommodate a range of diverse questions and study designs. The JBI manual provides guidance on how to analyse and include both quantitative and qualitative research.

Cochrane Methods Support Unit, webinar recordings on methodological support questions

Cochrane Qualitative & Implementation Methods Group. (2019). Training resources. Retrieved from https://methods.cochrane.org/qi/training-resources . (How to do a meta-synthesis, or qualitative evidence synthesis).

Center for Reviews and Dissemination (University of York, England) (2009). Systematic Reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking systematic reviews in health care . (British systematic review guidelines).

Agency for Health Research & Quality (AHRQ) (2013). Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews . (U.S. comparative effectiveness review guidelines)

Hunter, K. E., et al. (2022). Searching clinical trials registers: guide for systematic reviewers. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) , 377 , e068791. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-068791

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). The PCORI Methodology Report . (A 47-item methodology checklist for U.S. patient-centered outcomes research. Established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, PCORI funds the development of guidance on the comparative effectivess of clinical healthcare, similar to the UK National Institute for Clinical Evidence but without reporting cost-effectiveness QALY metrics).

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) (2019). Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Retrieved from https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters . A checklist of N American & international online databases and websites you can use to search for unpublished reports, posters, and policy briefs, on topics including general medicine and nursing, public and mental health, health technology assessment, drug and device regulatory, approvals, warnings, and advisories.

Hempel, S., Xenakis, L., & Danz, M. (2016). Systematic Reviews for Occupational Safety and Health Questions: Resources for Evidence Synthesis. Retrieved 8/15/16 from http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1463.html . NIOSH guidelines for how to carry out a systematic review in the occupational safety and health domain.

A good source for reporting guidelines is the NLM's Research Reporting Guidelines and Initiatives .

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). (An international group of academics/clinicians working to promote a common approach to grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations.)

Phillips, B., Ball, C., Sackett, D., et al. (2009). Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence. Retrieved 3/20/17 from https://www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/CEBM-Levels-of-Evidence-2.1.pdf . (Another commonly used criteria for grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations, developed in part by EBM guru David Sackett.)

Systematic Reviews for Animals & Food (guidelines including the REFLECT statement for carrying out a systematic review on animal health, animal welfare, food safety, livestock, and agriculture)

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. (Describes 14 different types of literature and systematic review, useful for thinking at the outset about what sort of literature review you want to do.)

Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements . Health information and libraries journal, 36(3), 202–222. doi:10.1111/hir.12276 (An updated look at different types of literature review, expands on the Grant & Booth 2009 article listed above).

Garrard, J. (2007). Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method (2nd Ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. (Textbook of health sciences literature search methods).

Zilberberg, M. (2012). Between the lines: Finding the truth in medical literature . Goshen, MA: Evimed Research Press. (Concise book on foundational concepts of evidence-based medicine).

Lang, T. (2009). The Value of Systematic Reviews as Research Activities in Medical Education . In: Lang, T. How to write, publish, & present in the health sciences : a guide for clinicians & laboratory researchers. Philadelphia : American College of Physicians. (This book chapter has a helpful bibliography on systematic review and meta-analysis methods)

Brown, S., Martin, E., Garcia, T., Winter, M., García, A., Brown, A., Cuevas H., & Sumlin, L. (2013). Managing complex research datasets using electronic tools: a meta-analysis exemplar . Computers, Informatics, Nursing: CIN, 31(6), 257-265. doi:10.1097/NXN.0b013e318295e69c. (This article advocates for the programming of electronic fillable forms in Adobe Acrobat Pro to feed data into Excel or SPSS for analysis, and to use cloud based file sharing systems such as Blackboard, RefWorks, or EverNote to facilitate sharing knowledge about the decision-making process and keep data secure. Of particular note are the flowchart describing this process, and their example screening form used for the initial screening of abstracts).

Brown, S., Upchurch, S., & Acton, G. (2003). A framework for developing a coding scheme for meta-analysis . Western Journal Of Nursing Research, 25(2), 205-222. (This article describes the process of how to design a coded data extraction form and codebook, Table 1 is an example of a coded data extraction form that can then be used to program a fillable form in Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Access).

Elamin, M. B., Flynn, D. N., Bassler, D., Briel, M., Alonso-Coello, P., Karanicolas, P., & ... Montori, V. M. (2009). Choice of data extraction tools for systematic reviews depends on resources and review complexity . Journal Of Clinical Epidemiology , 62 (5), 506-510. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.016 (This article offers advice on how to decide what tools to use to extract data for analytical systematic reviews).

Riegelman R. Studying a Study and Testing a Test: Reading Evidence-based Health Research , 6th Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012. (Textbook of quantitative statistical methods used in health sciences research).

Rathbone, J., Hoffmann, T., & Glasziou, P. (2015). Faster title and abstract screening? Evaluating Abstrackr, a semi-automated online screening program for systematic reviewers. Systematic Reviews, 480. doi:10.1186/s13643-015-0067-6

Guyatt, G., Rennie, D., Meade, M., & Cook, D. (2015). Users' guides to the medical literature (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education Medical. (This is a foundational textbook on evidence-based medicine and of particular use to the reviewer who wants to learn about the different types of published research article e.g. "what is a case report?" and to understand what types of study design best answer what types of clinical question).

Glanville, J., Duffy, S., Mccool, R., & Varley, D. (2014). Searching ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform to inform systematic reviews: what are the optimal search approaches? Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 102(3), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.102.3.007

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5 : 210, DOI: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. http://rdcu.be/nzDM

Kwon Y, Lemieux M, McTavish J, Wathen N. (2015). Identifying and removing duplicate records from systematic review searches. J Med Libr Assoc. 103 (4): 184-8. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.103.4.004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26512216

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 104 (3):240-3. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014. Erratum in: J Med Libr Assoc. 2017 Jan;105(1):111. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27366130

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 . PRESS is a guideline with a checklist for librarians to critically appraise the search strategy for a systematic review literature search.

Clark, JM, Sanders, S, Carter, M, Honeyman, D, Cleo, G, Auld, Y, Booth, D, Condron, P, Dalais, C, Bateup, S, Linthwaite, B, May, N, Munn, J, Ramsay, L, Rickett, K, Rutter, C, Smith, A, Sondergeld, P, Wallin, M, Jones, M & Beller, E 2020, 'Improving the translation of search strategies using the Polyglot Search Translator: a randomized controlled trial', Journal of the Medical Library Association , vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 195-207.

Journal articles describing systematic review methods can be searched for in PubMed using this search string in the PubMed search box: sysrev_methods [sb] .

Software tools for systematic reviews

- Covidence GW in 2019 has bought a subscription to this Cloud based tool for facilitating screening decisions, used by the Cochrane Collaboration. Register for an account.

- NVIVO for analysis of qualitative research NVIVO is used for coding interview data to identify common themes emerging from interviews with several participants. GW faculty, staff, and students may download NVIVO software.

- RedCAP RedCAP is software that can be used to create survey forms for research or data collection or data extraction. It has very detailed functionality to enable data exchange with Electronic Health Record Systems, and to integrate with study workflow such as scheduling follow up reminders for study participants.

- SRDR tool from AHRQ Free, web-based and has a training environment, tutorials, and example templates of systematic review data extraction forms

- RevMan 5 RevMan 5 is the desktop version of the software used by Cochrane systematic review teams. RevMan 5 is free for academic use and can be downloaded and configured to run as stand alone software that does not connect with the Cochrane server if you follow the instructions at https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman/revman-5-download/non-cochrane-reviews

- Rayyan Free, web-based tool for collecting and screening citations. It has options to screen with multiple people, masking each other.

- GradePro Free, web application to create, manage and share summaries of research evidence (called Evidence Profiles and Summary of Findings Tables) for reviews or guidelines, uses the GRADE criteria to evaluate each paper under review.

- DistillerSR Needs subscription. Create coded data extraction forms from templates.

- EPPI Reviewer Needs subscription. Like DistillerSR, tool for text mining, data clustering, classification and term extraction

- SUMARI Needs subscription. Qualitative data analysis.

- Dedoose Needs subscription. Qualitative data analysis, similar to NVIVO in that it can be used to code interview transcripts, identify word co-occurence, cloud based.

- Meta-analysis software for statistical analysis of data for quantitative reviews SPSS, SAS, and STATA are popular analytical statistical software that include macros for carrying out meta-analysis. Himmelfarb has SPSS on some 3rd floor computers, and GW affiliates may download SAS to your own laptop from the Division of IT website. To perform mathematical analysis of big data sets there are statistical analysis software libraries in the R programming language available through GitHub and RStudio, but this requires advanced knowledge of the R and Python computer languages and data wrangling/cleaning.

- PRISMA 2020 flow diagram generator The PRISMA Statement website has a page listing example flow diagram templates and a link to software for creating PRISMA 2020 flow diagrams using R software.

GW researchers may want to consider using Refworks to manage citations, and GW Box to store the full text PDF's of review articles. You can also use online survey forms such as Qualtrics, RedCAP, or Survey Monkey, to design and create your own coded fillable forms, and export the data to Excel or one of the qualitative analytical software tools listed above.

Forest Plot Generators

- RevMan 5 the desktop version of the software used by Cochrane systematic review teams. RevMan 5 is free for academic use and can be downloaded and configured to run as stand alone software that does not connect with the Cochrane server if you follow the instructions at https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman/revman-5-download/non-cochrane-reviews.

- Meta-Essentials a free set of workbooks designed for Microsoft Excel that, based on your input, automatically produce meta-analyses including Forest Plots. Produced for Erasmus University Rotterdam joint research institute.

- Neyeloff, Fuchs & Moreira Another set of Excel worksheets and instructions to generate a Forest Plot. Published as Neyeloff, J.L., Fuchs, S.C. & Moreira, L.B. Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes 5, 52 (2012). https://doi-org.proxygw.wrlc.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-52

- For R programmers instructions are at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/forestplot/vignettes/forestplot.html and you can download the R code package from https://github.com/gforge/forestplot

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Protocol and registration >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 11:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/systematic_review

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

- Duke NetID Login

- 919.660.1100

- Duke Health Badge: 24-hour access

- Accounts & Access

- Databases, Journals & Books

- Request & Reserve

- Training & Consulting

- Request Articles & Books

- Renew Online

- Reserve Spaces

- Reserve a Locker

- Study & Meeting Rooms

- Course Reserves

- Digital Health Device Collection

- Pay Fines/Fees

- Recommend a Purchase

- Access From Off Campus

- Building Access

- Computers & Equipment

- Wifi Access

- My Accounts

- Mobile Apps

- Known Access Issues

- Report an Access Issue

- All Databases

- Article Databases

- Basic Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Dissertations & Theses

- Drugs, Chemicals & Toxicology

- Grants & Funding

- Interprofessional Education

- Non-Medical Databases

- Search for E-Journals

- Search for Print & E-Journals

- Search for E-Books

- Search for Print & E-Books

- E-Book Collections

- Biostatistics

- Global Health

- MBS Program

- Medical Students

- MMCi Program

- Occupational Therapy

- Path Asst Program

- Physical Therapy

- Researchers

- Community Partners

Conducting Research

- Archival & Historical Research

- Black History at Duke Health

- Data Analytics & Viz Software

- Data: Find and Share

- Evidence-Based Practice

- NIH Public Access Policy Compliance

- Publication Metrics

- Qualitative Research

- Searching Animal Alternatives

Systematic Reviews

- Test Instruments

Using Databases

- JCR Impact Factors

- Web of Science

Finding & Accessing

- COVID-19: Core Clinical Resources

- Health Literacy

- Health Statistics & Data

- Library Orientation

Writing & Citing

- Creating Links

- Getting Published

- Reference Mgmt

- Scientific Writing

Meet a Librarian

- Request a Consultation

- Find Your Liaisons

- Register for a Class

- Request a Class

- Self-Paced Learning

Search Services

- Literature Search

- Systematic Review

- Animal Alternatives (IACUC)

- Research Impact

Citation Mgmt

- Other Software

Scholarly Communications

- About Scholarly Communications

- Publish Your Work

- Measure Your Research Impact

- Engage in Open Science

- Libraries and Publishers

- Directions & Maps

- Floor Plans

Library Updates

- Annual Snapshot

- Conference Presentations

- Contact Information

- Gifts & Donations

- What is a Systematic Review?

Types of Reviews

- Manuals and Reporting Guidelines

- Our Service

- 1. Assemble Your Team

- 2. Develop a Research Question

- 3. Write and Register a Protocol

- 4. Search the Evidence

- 5. Screen Results

- 6. Assess for Quality and Bias

- 7. Extract the Data

- 8. Write the Review

- Additional Resources

- Finding Full-Text Articles

Review Typologies

There are many types of evidence synthesis projects, including systematic reviews as well as others. The selection of review type is wholly dependent on the research question. Not all research questions are well-suited for systematic reviews.

- Review Typologies (from LITR-EX) This site explores different review methodologies such as, systematic, scoping, realist, narrative, state of the art, meta-ethnography, critical, and integrative reviews. The LITR-EX site has a health professions education focus, but the advice and information is widely applicable.

Review the table to peruse review types and associated methodologies. Librarians can also help your team determine which review type might be appropriate for your project.

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91-108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- << Previous: What is a Systematic Review?

- Next: Manuals and Reporting Guidelines >>

- Last Updated: Mar 20, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview

- Duke Health

- Duke University

- Duke Libraries

- Medical Center Archives

- Duke Directory

- Seeley G. Mudd Building

- 10 Searle Drive

- [email protected]

Library Services

UCL LIBRARY SERVICES

- Guides and databases

- Library skills

- Systematic reviews

Types of systematic reviews

- What are systematic reviews?

- Formulating a research question

- Identifying studies

- Searching databases

- Describing and appraising studies

- Synthesis and systematic maps

- Software for systematic reviews

- Online training and support

- Live and face to face training

- Individual support

- Further help

There are many types of systematic reviews. They may ask different kinds of questions and use a variety of methods, just like primary research. As with primary research, they vary in terms of perspective, purpose, approach, methods, and the time and resources used to conduct them.

Some reviews may ask broad questions (over a wide topic area) and examine them in little detail whilst others may ask narrow questions that are examined in great detail. Some reviews ask such broad questions that these are split into sub-questions that are addressed by different sub-components in the review each with different review methods considering different types of primary studies (multi-component reviews).

Dimensions of difference in systematic reviews

- EPPI Centre: Dimensions of Difference in Systematic Reviews This video (22 mins) describes the Dimensions of Difference in Systematic Reviews by David Gough of the UCL IOE EPPI-Centre.

Further reading

- Clarifying differences between review designs and methods / Gough et al. 2012 This paper clarifies differences between review designs and methods.

- Approaches to evidence synthesis in international development: a research agenda / Oliver et al. 2018 International development is an area where systematic review methods have been applied to complex situations for a variety of purposes. This paper details some of these different approaches and synthesis methods,

- Perspectives on the methods of a large systematic mapping of maternal health interventions / Chersich et al. 2016 One large systematic map describes maternal health interventions in 2292 full text articles. The perspectives of 15 researchers from the review team provide insights into some of the challenges in systematically identifying and describing studies, and in being part of a large review team.

Demystifying literature reviews

- Demystifying Literature Reviews: What I Have Learned From an Expert? This paper illustrates some differences between three broad groups of reviews, provides some practical insights into searching and other stages in reviewing, and gives further readings. Please note: this paper briefly groups scoping reviews and mapping reviews together, but these two types of reviews can be very different from each other.

- Systematic evidence maps Find out more about how scoping reviews and mapping reviews differ.

- << Previous: What are systematic reviews?

- Next: Stages in a systematic review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 10:09 AM

- URL: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/systematic-reviews

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Systematic Reviews & Evidence Synthesis Methods

Types of reviews.

- Formulate Question

- Find Existing Reviews & Protocols

- Register a Protocol

- Searching Systematically

- Supplementary Searching

- Managing Results

- Deduplication

- Critical Appraisal

- Glossary of terms

- Librarian Support

- Video tutorials This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis Boot Camp

Not sure what type of review you want to conduct?

There are many types of reviews --- narrative reviews , scoping reviews , systematic reviews, integrative reviews, umbrella reviews, rapid reviews and others --- and it's not always straightforward to choose which type of review to conduct. These Review Navigator tools (see below) ask a series of questions to guide you through the various kinds of reviews and to help you determine the best choice for your research needs.

- Which review is right for you? (Univ. of Manitoba)

- What type of review is right for you? (Cornell)

- Review Ready Reckoner - Assessment Tool (RRRsAT)

- A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. by Grant & Booth

- Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements | Health Info Libr J, 2019

Reproduced from Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 8:57 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/systematicreviews

Systematic Review Process: Types of Reviews

- Definitions of a Systematic Review

Types of Reviews

- Systematic Review Planning Process

- Resources Needed to Conduct a Review

- Reporting Guidelines

- Where to Search

- How to Search

- Screening and Study Selection

- Data Extraction

- Appraisal and Analysis

- Citation Management

- Additional Resources: Guides and Books

- Using Covidence for Your Systematic Review

- Librarian Collaboration

Narrative vs. Systematic Reviews

People often confuse systematic and literature (narrative) reviews. They both are used to provide a summary of the existing literature or research on a specific topic.

A narrative or traditional literature review is a comprehensive, critical, and objective analysis of the current knowledge on a topic. They are an essential part of the research process and help to establish a theoretical framework and focus or context for your research. A literature review will help you to identify patterns and trends in the literature so that you can identify gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge. This should lead you to a sufficiently focused research question that justifies your research.

A systematic review is comprehensive and has minimal bias. It is based on a specific question and uses eligibility criteria and a pre-planned protocol. This type of study evaluates the quality of evidence.

A systematic review can be either quantitative or qualitative:

- If quantitative, the review will include studies that have numerical data.

- If qualitative, the review derives data from observation, interviews, or verbal interactions and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants. It will include focus groups, interviews, observations and diaries.

Narrative reviews in comparison provide a perspective on topic (like a textbook chapter), may have no specified search strategy, might have significant bias issues, and may not evaluate quality of evidence.

This table provides a detailed comparison of systematic and literature (narrative) reviews.

Tools to Help You Choose a Review Type

There are other comprehensive literature reviews of similar methodology to the systematic review. These tools can help you determine which type of review you may want to conduct.

- The Review Ready Reckoner - Assessment Tool (RRRsAT) is a chart created as an adaptation of Andrew Booth's article on review typology. The chart that describes the features of multiple review types listing characteristics that distinguish each type and including sample of each type of review.

- The What Review is Right for You tool asks five short questions to help you identify the most appropriate method for a review.

Use this chart to determine the type of review you are interested in writing and to learn the differences in the stages and processes of various reviews compared to systematic reviews.

Source: Yale University

The type of review you conduct will depend on the purpose of the review, your question, your resources, expertise, and type of data.

Here are two suggested articles to consult if you want to know more about review types:

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health information & libraries journal , 26 (2), 91-108. This article defines 14 types of reviews. There is a helpful summary table on pp.94-95

Sutton A, Clowes M, Preston L, Booth A. Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health information & libraries journal . 2019;36(3):202–222. doi:10.1111/hir.12276

This Comparison table is derived from a guide which is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license , and was originally included in a workbook by Amanda Wanner at Plymouth University for Systematic Reviews and Scoping Reviews. Stephanie Roth at Temple University remixed the original version. Many thanks and much appreciation to Amanda Wanner and Stephanie Roth for allowing me to create a derivative of their work.

Funaro, M., Nyhan, K., & Brackett, A. (n.d.). What type of review could you write? Yale Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library.

- << Previous: Definitions of a Systematic Review

- Next: Systematic Review Planning Process >>

- Last Updated: Dec 27, 2023 12:48 PM

- URL: https://library.aah.org/guides/systematicreview

- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 10 January 2018

What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences

- Zachary Munn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7091-5842 1 ,

- Cindy Stern 1 ,

- Edoardo Aromataris 1 ,

- Craig Lockwood 1 &

- Zoe Jordan 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 18 , Article number: 5 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

120k Accesses

2019 Citations

406 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systematic reviews have been considered as the pillar on which evidence-based healthcare rests. Systematic review methodology has evolved and been modified over the years to accommodate the range of questions that may arise in the health and medical sciences. This paper explores a concept still rarely considered by novice authors and in the literature: determining the type of systematic review to undertake based on a research question or priority.

Within the framework of the evidence-based healthcare paradigm, defining the question and type of systematic review to conduct is a pivotal first step that will guide the rest of the process and has the potential to impact on other aspects of the evidence-based healthcare cycle (evidence generation, transfer and implementation). It is something that novice reviewers (and others not familiar with the range of review types available) need to take account of but frequently overlook. Our aim is to provide a typology of review types and describe key elements that need to be addressed during question development for each type.

Conclusions

In this paper a typology is proposed of various systematic review methodologies. The review types are defined and situated with regard to establishing corresponding questions and inclusion criteria. The ultimate objective is to provide clarified guidance for both novice and experienced reviewers and a unified typology with respect to review types.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Systematic reviews are the gold standard to search for, collate, critique and summarize the best available evidence regarding a clinical question [ 1 , 2 ]. The results of systematic reviews provide the most valid evidence base to inform the development of trustworthy clinical guidelines (and their recommendations) and clinical decision making [ 2 ]. They follow a structured research process that requires rigorous methods to ensure that the results are both reliable and meaningful to end users. Systematic reviews are therefore seen as the pillar of evidence-based healthcare [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. However, systematic review methodology and the language used to express that methodology, has progressed significantly since their appearance in healthcare in the 1970’s and 80’s [ 7 , 8 ]. The diachronic nature of this evolution has caused, and continues to cause, great confusion for both novice and experienced researchers seeking to synthesise various forms of evidence. Indeed, it has already been argued that the current proliferation of review types is creating challenges for the terminology for describing such reviews [ 9 ]. These fundamental issues primarily relate to a) the types of questions being asked and b) the types of evidence used to answer those questions.

Traditionally, systematic reviews have been predominantly conducted to assess the effectiveness of health interventions by critically examining and summarizing the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (using meta-analysis where feasible) [ 4 , 10 ]. However, health professionals are concerned with questions other than whether an intervention or therapy is effective, and this is reflected in the wide range of research approaches utilized in the health field to generate knowledge for practice. As such, Pearson and colleagues have argued for a pluralistic approach when considering what counts as evidence in health care; suggesting that not all questions can be answered from studies measuring effectiveness alone [ 4 , 11 ]. As the methods to conduct systematic reviews have evolved and advanced, so too has the thinking around the types of questions we want and need to answer in order to provide the best possible, evidence-based care [ 4 , 11 ].

Even though most systematic reviews conducted today still focus on questions relating to the effectiveness of medical interventions, many other review types which adhere to the principles and nomenclature of a systematic review have emerged to address the diverse information needs of healthcare professionals and policy makers. This increasing array of systematic review options may be confusing for the novice systematic reviewer, and in our experience as educators, peer reviewers and editors we find that many beginner reviewers struggle to achieve conceptual clarity when planning for a systematic review on an issue other than effectiveness. For example, reviewers regularly try to force their question into the PICO format (population, intervention, comparator and outcome), even though their question may be an issue of diagnostic test accuracy or prognosis; attempting to define all the elements of PICO can confound the remainder of the review process. The aim of this article is to propose a typology of systematic review types aligned to review questions to assist and guide the novice systematic reviewer and editors, peer-reviewers and policy makers. To our knowledge, this is the first classification of types of systematic reviews foci conducted in the medical and health sciences into one central typology.

Review typology

For the purpose of this typology a systematic review is defined as a robust, reproducible, structured critical synthesis of existing research. While other approaches to the synthesis of evidence exist (including but not limited to literature reviews, evidence maps, rapid reviews, integrative reviews, scoping and umbrella reviews), this paper seeks only to include approaches that subscribe to the above definition. As such, ten different types of systematic review foci are listed below and in Table 1 . In this proposed typology, we provide the key elements for formulating a question for each of the 10 review types.

Effectiveness reviews [ 12 ]

Experiential (Qualitative) reviews [ 13 ]

Costs/Economic Evaluation reviews [ 14 ]

Prevalence and/or Incidence reviews [ 15 ]

Diagnostic Test Accuracy reviews [ 16 ]

Etiology and/or Risk reviews [ 17 ]

Expert opinion/policy reviews [ 18 ]

Psychometric reviews [ 19 ]

Prognostic reviews [ 20 ]

Methodological systematic reviews [ 21 , 22 ]

Effectiveness reviews

Systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness of an intervention or therapy are by far the most common. Essentially effectiveness is the extent to which an intervention, when used appropriately, achieves the intended effect [ 11 ]. The PICO approach (see Table 1 ) to question development is well known [ 23 ] and comprehensive guidance for these types of reviews is available [ 24 ]. Characteristics regarding the population (e.g. demographic and socioeconomic factors and setting), intervention (e.g. variations in dosage/intensity, delivery mode, and frequency/duration/timing of delivery), comparator (active or passive) and outcomes (primary and secondary including benefits and harms, how outcomes will be measured including the timing of measurement) need to be carefully considered and appropriately justified.

Experiential (qualitative) reviews

Experiential (qualitative) reviews focus on analyzing human experiences and cultural and social phenomena. Reviews including qualitative evidence may focus on the engagement between the participant and the intervention, as such a qualitative review may describe an intervention, but its question focuses on the perspective of the individuals experiencing it as part of a larger phenomenon. They can be important in exploring and explaining why interventions are or are not effective from a person-centered perspective. Similarly, this type of review can explain and explore why an intervention is not adopted in spite of evidence of its effectiveness [ 4 , 13 , 25 ]. They are important in providing information on the patient’s experience, which can enable the health professional to better understand and interact with patients. The mnemonic PICo can be used to guide question development (see Table 1 ). With qualitative evidence there is no outcome or comparator to be considered. A phenomenon of interest is the experience, event or process occurring that is under study, such as response to pain or coping with breast cancer; it differs from an intervention in its focus. Context will vary depending on the objective of the review; it may include consideration of cultural factors such as geographic location, specific racial or gender based interests, and details about the setting such as acute care, primary healthcare, or the community [ 4 , 13 , 25 ]. Reviews assessing the experience of a phenomenon may opt to use a mixed methods approach and also include quantitative data, such as that from surveys. There are reporting guidelines available for qualitative reviews, including the ‘Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research’ (ENTREQ) statement [ 26 ] and the newly proposed meta-ethnography reporting guidelines (eMERGe) [ 27 ].

Costs/economic evaluation reviews

Costs/Economics reviews assess the costs of a certain intervention, process, or procedure. In any society, resources available (including dollars) have alternative uses. In order to make the best decisions about alternative courses of action evidence is needed on the health benefits and also on the types and amount of resources needed for these courses of action. Health economic evaluations are particularly useful to inform health policy decisions attempting to achieve equality in healthcare provision to all members of society and are commonly used to justify the existence and development of health services, new health technologies and also, clinical guideline development [ 14 ]. Issues of cost and resource use may be standalone reviews or components of effectiveness reviews [ 28 ]. Cost/Economic evaluations are examples of a quantitative review and as such can follow the PICO mnemonic (see Table 1 ). Consideration should be given to whether the entire world/international population is to be considered or only a population (or sub-population) of a particular country. Details of the intervention and comparator should include the nature of services/care delivered, time period of delivery, dosage/intensity, co-interventions, and personnel undertaking delivery. Consider if outcomes will only focus on resource usage and costs of the intervention and its comparator(s) or additionally on cost-effectiveness. Context (including perspective) can also be considered in these types of questions e.g. health setting(s).

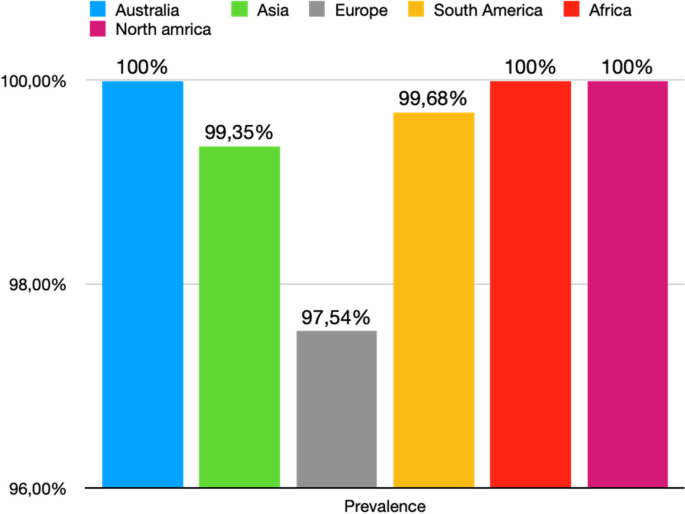

Prevalence and/or incidence reviews