Race & Ethnicity—Definition and Differences [+48 Race Essay Topics]

Race and ethnicity are among the features that make people different. Unlike character traits, attitudes, and habits, race and ethnicity can’t be changed or chosen. It fully depends on the ancestry.

But why do we separate these two concepts and what are their core differences? How do people classify different races and types of ethnicity?

To find answers to these questions, keep reading the article.

Also, if you have a writing assignment on the same topic due soon and looking for inspiration, you’ll find plenty of race, racism, and ethnic group essay examples. At IvyPanda , we’ve gathered over 45 samples to help you with your writing, so you don’t have to torture yourself looking for awesome essay ideas.

Race and Ethnicity Definitions

It’s important to learn what race and ethnicity really are before trying to compare them and explore their classification.

Race is a group of people that belong to the same distinct category based on their physical and social qualities.

At the very beginning of the term usage, it only referred to people speaking a common language. Later, the term started to denote certain national affiliations. A reference to physical traits was added to the term race in the 17th century.

In a modern world, race is considered to be a social construct. In other words, it’s a distinguishable identity with a cultural meaning behind. Race is not usually seen as exclusively biological or physical quality, even though it’s partially based on common physical features among group members.

Ethnicity (also known as ethnic group) is a category of people who have similarities like common language, ancestry, history, culture, society, and nation.

Basically, people inherit ethnicity depending on the society they live in. Other factors that define a person’s ethnicity include symbolic systems like religion, cuisine, art, dressing style, and even physical appearance.

Sometimes, the term ethnicity is used as a synonym to people or nation. It’s also fair to mention that it’s sometimes possible for an individual to leave one ethnic group and shift to another. It’s usually done through acculturation, language shift, or religious conversion.

Though, most of the times, representatives of a certain ethnic group continue to speak their common language and share some other typical traits even if derived from their founder population.

Differences Between Race and Ethnicity

Now that we know what race and ethnicity are all about, let’s highlight some of the major differences between these two terms.

- It divides people into groups or populations based mainly on physical appearance

- The main accent is on genetic or biological traits

- Because of geographical isolation, racial categories were a result of a shared genealogy. In modern world, this isolation is practically nonexistent, which lead to mixing of races

- The distinguishing factors can include type of face or skin color. Other genetic differences are considered to be weak

- Members of an ethnic group identify themselves based on nationality, culture, and traditions

- The emphasis is on group history, culture, and sometimes on religion and language

- Definition of ethnicity is based on shared genealogy. It can be either actual or presumed

- Distinguishing factors of ethnic groups keep changing depending on time period. Sometimes, they get defined by stereotypes that dominant groups have

It’s also worth mentioning that the border between two terms is quite vague . As a result, the choice of using either of them can be very subjective.

In the majority of cases, race is considered to be unitary, which means that one person belongs to one race. However, ethnically, this same person can identify themselves as a member of multiple ethnic groups. And it won’t be wrong if a person have lived enough time within those groups.

Race and Ethnicity Classification

It’s time to look at possible ways to classify racial and ethnical groups.

One of the most common classifications for race into four categories: Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid, and Australoid. Three of them have subcategories.

Let’s look at them more closely.

– Caucasoid. White race with light skin color. Hair ranges from brown to black. They have medium to high structure. The subcategories are as follows:

- Alpine. Live in Central Asia

- Nordic . Baltic, British, and Scandinavian inhabitants

- Mediterranean. Hail from France, Italy, Portugal, and Spain

– Mongoloid. The race’s majority is found in Asia. Characterized by black hair, yellow skin tone, and medium height.

- Asian mongol. Found in japan, China, and East-India

- Micronesian. Inhabitants of Malenesia

– Negroid. A race found in Africa. They have black skin, wooly hair, and medium to high structure.

- Negro. African inhabitants

- Far Eastern Pygmy. Found in the south Pacific islands

- Bushman and Hottentot. Live in Kala-Hari desert of Africa

– Australoid. Found in Australia. They have wavy hair, light skin, and medium to tall height.

It’s fair to mention yet again that it’s practically impossible to find pure race representatives because of how mixed they all got.

Speaking of ethnicity classification, one of the most common ways to do that is by continent. And each of continent’s ethnic groups will have their own subcategory.

So, we can roughly divide ethnic groups into following categories:

- North American

- South American

Race Essay Ideas

If all the information above was not enough and you’re looking for race essay topics, or even straight up essay examples for your writing assignment—today’s your lucky day. Because experts at IvyPanda have gathered plenty of those.

Check out the list of race and ethnic group essay samples below. Use them for inspiration, or try to develop one of the suggested topics even further.

Whatever option you’ll choose, we’re sure that you’ll end up with great results!

- The Anatomy of Scientific Racism: Racialist Responses to Black Athletic Achievement

- Race, Ethnicity and Crime

- Representation of Race in Disney Films

- What is the relationship between Race, Poverty and Prison?

- Race in a Southern Community

- African American Women and the Struggle for Racial Equality

- American Ethnic Studies

- Institutionalized Racism from John Brown Raid to Jim Crow Laws

- The Veil and Muslim

- Race and the Body: How Culture Both Shapes and Mirrors Broader Societal Attitudes Towards Race and the Body

- Latinos and African Americans: Friends or Foes?

- Historical US Relationships with Native American

- The experiences of the Aborigines

- Contemporary Racism in Australia: the Experience of Aborigines

- No Reparations for Blacks for the Injustice of Slavery

- Racism (another variant)

- Hispanic Americans

- Racism in the Penitentiary

- How the development of my racial/ethnic identity has been impacted

- My father’s black pride

- African American Ethnic Group

- Ethnic Group Conflicts

- How the Movie Crash Presents the African Americans

- Ethnic Groups and discrimination

- Race and Ethnicity

- Racial and ethnic inequality

- Ethnic Groups and Conflicts

- Ethnics Studies

- Ethnic studies and emigration

- Ethnicity Influence

- Immigration and Ethnic Relations

- A comparison Between Asian Americans and Latinos

- Analysis of the Chinese Experience in “A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America” by Ronald Takaki

- Wedding in the UAE

- Social and Cultural Diversity

- The White Dilemma in South Africa

- Ethnocentrism and its Effects on Individuals, Societies, and Multinationals

- Reduction of ethnocentrism and promotion of cultural relativism

- Racial and Ethnic Groups

- Gender and Race

- Child Marriages in Modern India

- Race and Ethnicity (another variant)

- Racial Relations and Color Blindness

- Multiculturalism and “White Anxiety”

- Cultural and racial inequality in Health Care

- The impact of colonialism on cultural transformations in North and South America

- African American Studies

- Share via Facebook

- Share via Twitter

- Share via LinkedIn

- Share via email

You might also like

![essay ideas of race Make Your Online Research More Effective [9 Super Hacks]](https://ivypanda.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Online-Research-309x208.jpg)

Make Your Online Research More Effective [9 Super Hacks]

How to Plan a Paper to Write on: 9 Ways

How to Avoid Plagiarism – 12 Must-Know Ways

Home — Blog — Topic Ideas — Essay Topics on Racism: 150 Ideas for Analysis and Discussion

Essay Topics on Racism: 150 Ideas for Analysis and Discussion

Here’s a list of 150 essay ideas on racism to help you ace a perfect paper. The subjects are divided based on what you require!

Before we continue with the list of essay topics on racism, let's remember the definition of racism. In brief, it's a complex prejudice and a form of discrimination based on race. It can be done by an individual, a group, or an institution. If you belong to a racial or ethnic group, you are facing being in the minority. As it's usually caused by the group in power, there are many types of racism, including socio-cultural racism, internal racism, legal racism, systematic racism, interpersonal racism, institutional racism, and historical racism. You can also find educational or economic racism as there are many sub-sections that one can encounter.

150 Essay Topics on Racism to Help You Ace a Perfect Essay

General Recommendations

The subject of racism is one of the most popular among college students today because you can discuss it regardless of your academic discipline. Even though we are dealing with technical progress and the Internet, the problem of racism is still there. The world may go further and talk about philosophical matters, yet we still have to face them and explore the challenges. It makes it even more difficult to find a good topic that would be unique and inspiring. As a way to help you out, we have collected 150 racism essay topics that have been chosen by our experts. We recommend you choose something that motivates you and narrow things down a little bit to make your writing easier.

Why Choose a Topic on Racial Issues?

When we explore racial issues, we are not only seeking the most efficient solutions but also reminding ourselves about the past and the mistakes that we should never make again. It is an inspirational type of work as we all can change the world. If you cannot choose a topic that inspires you, think about recent events, talk about your friend, or discuss something that has happened in your local area. Just take your time and think about how you can make the world a safer and better place.

The Secrets of a Good Essay About Racism

The secret to writing a good essay on racism is not only stating that racism is bad but by exploring the origins and finding a solution. You can choose a discipline and start from there. For example, if you are a nursing student, talk about the medical principles and responsibilities where every person is the same. Talk about how it has not always been this way and discuss the methods and the famous theorists who have done their best to bring equality to our society. Keep your tone inspiring, explore, and tell a story with a moral lesson in the end. Now let’s explore the topic ideas on racism!

General Essay Topics On Racism

As we know, no person is born a racist since we are not born this way and it cannot be considered a biological phenomenon. Since it is a practice that is learned and a social issue, the general topics related to racism may include socio-cultural, philosophical, and political aspects as you can see below. Here are the ideas that you should consider as you plan to write an essay on racial issues:

- Are we born with racial prejudice?

- Can racism be unlearned?

- The political constituent of the racial prejudice and the colonial past?

- The humiliation of the African continent and the control of power.

- The heritage of the Black Lives Matter movement and its historical origins.

- The skin color issue and the cultural perceptions of the African Americans vs Mexican Americans.

- The role of social media in the prevention of racial conflicts in 2022 .

- Martin Luther King Jr. and his role in modern education.

- Konrad Lorenz and the biological perception of the human race.

- The relation of racial issues to nazism and chauvinism.

The Best Racism Essay Topics

School and college learners often ask about what can be considered the best essay subject when asked to write on racial issues. Essentially, you have to talk about the origins of racism and provide a moral lesson with a solution as every person can be a solid contribution to the prevention of hatred and racial discrimination.

- The schoolchildren's example and the attitude to the racial conflicts.

- Perception of racism in the United States versus Germany.

- The role of the scouting movement as a way to promote equality in our society.

- Social justice and the range of opportunities that African American individuals could receive during the 1960s.

- The workplace equality and the negative perception of the race when the documents are being filed.

- The institutional racism and the sources of the legislation that has paved the way for injustice.

- Why should we talk to the children about racial prejudice and set good examples ?

- The role of anthropology in racial research during the 1990s in the USA.

- The Black Poverty phenomenon and the origins of the Black Culture across the globe.

- The controversy of Malcolm X’s personality and his transition from anger to peacemaking.

Shocking Racism Essay Ideas

Unfortunately, there are many subjects that are not easy to deal with when you are talking about the most horrible sides of racism. Since these subjects are sensitive, dealing with the shocking aspects of this problem should be approached with a warning in your introduction part so your readers know what to expect. As a rule, many medical and forensic students will dive into the issue, so these topic ideas are still relevant:

- The prejudice against wearing a hoodie.

- The racial violence in Western Africa and the crimes by the Belgian government.

- The comparison of homophobic beliefs and the link to racial prejudice.

- Domestic violence and the bias towards the cases based on race.

- Racial discrimination in the field of the sex industry.

- Slavery in the Middle East and the modern cultural perceptions.

- Internal racism in the United States: why the black communities keep silent.

- Racism in the American schools: the bias among the teachers.

- Cyberbullying and the distorted image of the typical racists .

- The prisons of Apartheid in South Africa.

Light and Simple Ideas Regarding Racism

If you are a high-school learner or a first-year college student, your essay on racism may not have to represent complex research with a dozen of sources. Here are some good ideas that are light and simple enough to provide you with inspiration and the basic points to follow:

- My first encounter with racial prejudice.

- Why do college students are always in the vanguard of social campaigns?

- How are the racial issues addressed by my school?

- The promotion of the African-American culture is a method to challenge prejudice and stereotypes.

- The history of blues music and the Black culture of the blues in the United States.

- The role of slavery in the Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain.

- School segregation in the United States during the 1960s.

- The negative effect of racism on the mental health of a person.

- The advocacy of racism in modern society .

- The heritage of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and the modern perception of the historical issues.

Interesting Topics on Racism For an Essay

Contrary to the popular belief, when you have to talk about the cases of racial prejudice, you will also encounter many interesting essay topic ideas. As long as these are related to your main academic course, you can explore them. Here are some great ideas to consider:

- Has the perception of Michael Jackson changed because of his skin transition?

- The perception of racial problems by the British Broadcasting Corporation.

- The role of the African American influencers on Instagram.

- The comparison between the Asian students and the Mexican learners in the USA.

- Latin culture and the similarities when compared to the Black culture with its peculiarities.

- The racial impact in the “Boy In The Stripped Pajamas”.

- Can we eliminate racism completely and how exactly, considering the answer is “Yes”?

- Scientific research of modern racism and social media campaigns.

- Why do some people believe that the Black Lives Matter movement is controversial?

- Male vs female challenges in relation to racial attitudes.

Argumentative Essay Topics About Race

An argumentative type of writing requires making a clear statement or posing an assumption that will deal with a particular question. As we are dealing with racial prejudice or theories, it is essential to support your writing with at least one piece of evidence to make sure that you can support your opinion and stand for it as you write. Here are some good African American argumentative essay examples of topics and other ideas to consider:

- Racism is a mental disorder and cannot be treated with words alone.

- Analysis of the traumatic experiences based on racial prejudice.

- African-American communities and the sense of being inferior are caused by poverty.

- Reading the memoirs of famous people that describe racial issues often provides a distorted image through the lens of a single person.

- There is no academic explanation of racism since every case is different and is often based on personal perceptions.

- The negatives of the post-racial perception as the latent system that advocates racism.

- The link of racial origins to the concept of feminism and gender inequality.

- The military bias and the merits that are earned by the African-American soldiers.

- The media causes a negative image of the Latin and Mexican youth in the United States.

- Does racism exist in kindergarten and why the youngsters do not think about racial prejudice?

Racism Research Paper Topics

Dealing with The Black Lives Matter essay , you should focus on those aspects of racism that are not often discussed or researched by the media. You can take a particular case study or talk about the reasons why the BLM social campaign has started and whether the timing has been right. Here are some interesting racism topics for research paper that you should consider:

- The link of criminal offenses to race is an example of the primary injustice .

- The socio-emotional burdens of slavery that one can trace among the representatives of the African-American population.

- Study of the cardio-vascular diseases among the American youth: a comparison of the Caucasian and Latin representatives.

- The race and the politics: dealing with the racial issues and the Trump administration analysis.

- The best methods to achieve medical equality for all people: where race has no place to be.

- The perception of racism by the young children: the negative side of trying to educate the youngsters.

- Racial prejudice in the UK vs the United States: analysis of the core differences.

- The prisons in the United States: why do the Blacks constitute the majority?

- The culture of Voodoo and the slavery: the link between the occult practices.

- The native American people and the African Americans: the common woes they share.

Racism in Culture Topics

Racism topics for essay in culture are always upon the surface because we can encounter them in books, popular political shows, movies, social media, and more. The majority of college students often ignore this aspect because things easily become confusing since one has to take a stand and explain the point. As a way to help you a little bit, we have collected several cultural racism topic ideas to help you start:

- The perception of wealth by the Black community: why it differs when researched through the lens of past poverty?

- The rap music and the cultural constituent of the African-American community.

- The moral constituent of the political shows where racial jargon is being used.

- Why the racial jokes on television are against the freedom of speech?

- The ways how the modern media promotes racism by stirring up the conflict and actually doing harm.

- The isolated cases of racism and police violence in the United States as portrayed by the movies.

- Playing with the Black musicians: the history of jazz in the United States.

- The social distancing and the perception of isolation by the different races.

- The cultural multitude in the cartoons by the Disney Corporations: the pros and cons.

- From assimilation to genocide: can the African American child make it big without living through the cultural bias?

Racism Essay Ideas in Literature

One of the best ways to study racism is by reading the books by those who have been through it on their own or by studying the explorations by those who can write emotionally and fight for racial equality where racism has no place to be. Keeping all of these challenges in mind, our experts suggest turning to the books as you can explore racism in the literature by focusing on those who are against it and discussing the cases in the classic literature that are quite controversial.

- The racial controversy of Ernest Hemingway's writing.

- The personal attitude of Mark Twain towards slavery and the cultural peculiarities of the times.

- The reasons why "To Kill a Mockingbird" by Harper Lee book has been banned in libraries.

- The "Hate You Give" by Angie Thomas and the analysis of the justified and "legit" racism.

- Is the poetry by the gangsta rap an example of hidden racism?

- Maya Angelou and her timeless poetry.

- The portrayal of xenophobia in modern English language literature.

- What can we learn from the "Schilder's List" screenplay as we discuss the subject of genocide?

- Are there racial elements in "Othello" or Shakespeare's creation is beyond the subject?

- Kate Chopin's perception of inequality in "Desiree's Baby".

Racism in Science Essay Ideas

Racism is often studied by scientists because it's not only a cultural point or a social agenda that is driven by personal inferiority and similar factors of mental distortion. Since we can talk about police violence and social campaigns, it is also possible to discuss things through different disciplines. Think over these racism thesis statement ideas by taking a scientific approach and getting a common idea explained:

- Can physical trauma become a cause for a different perception of race?

- Do we inherit racial intolerance from our family members and friends?

- Can a white person assimilate and become a part of the primarily Black community?

- The people behind the concept of Apartheid: analysis of the critical factors.

- Can one prove the fact of the physical damage of the racial injustice that lasted through the years?

- The bond between mental diseases and the slavery heritage among the Black people.

- Should people carry the blame for the years of social injustice?

- How can we explain the metaphysics of race?

- What do the different religions tell us about race and the best ways to deal with it?

- Ethnic prejudices based on age, gender, and social status vs general racism.

Cinema and Race Topics to Write About

As a rule, the movies are also a great source for writing an essay on racial issues. Remember to provide the basic information about the movie or include examples with the quotations to help your readers understand all the major points that you make. Here are some ideas that are worth your attention:

- The negative aspect of the portrayal of racial issues by Hollywood.

- Should the disturbing facts and the graphic violence be included in the movies about slavery?

- Analysis of the "Green Mile" movie and the perception of equality in our society.

- The role of music and culture in the "Django Unchained" movie.

- The "Ghosts of Mississippi" and the social aspect of the American South compared to how we perceive it today.

- What can we learn from the "Malcolm X" movie created by Spike Lee?

- "I am Not Your Negro" movie and the role of education through the movies.

- "And the Children Shall Lead" the movie as an example that we are not born racist.

- Do we really have the "Black Hollywood" concept in reality?

- Do the movies about racial issues only cause even more racial prejudice?

Race and Ethnic Relations

Another challenging problem is the internal racism and race and ethnicity essay topics that we can observe not only in the United States but all over the world as well. For example, the Black people in the United States and the representatives of the rap music culture will divide themselves between the East Coast and the West Coast where far more than cultural differences exist. The same can be encountered in Afghanistan or in Belgium. Here are some essay topics on race and ethnicity idea samples to consider:

- The racial or the ethnic conflict? What can we learn from Afghan society?

- Religious beliefs divide us based on ethnicity .

- What are the major differences between ethnic and racial conflicts?

- Why we are able to identify the European Black person and the Black coming from the United States?

- Racism and ethnicity's role in sports.

- How can an ethnic conflict be resolved with the help of anti-racial methods?

- The medical aspect of being an Asian in the United States.

- The challenges of learning as an African American person during the 1950s.

- The role of the African American people in the Vietnam war and their perception by the locals.

- Ethnicity's role in South Africa as the concept of Apartheid has been formed.

Biology and Racial Issues

If you are majoring in Biology or would like to research this side of the general issue of race, it is essential to think about how we can fight racism in practice by turning to healthcare or the concepts that are historical in their nature. Although we cannot explain slavery per se other than by turning to economics and the rule of power that has no justification, biologists believe that racial challenges can be approached by their core beliefs as well.

- Can we create an isolated non-racist society in 2022?

- If we assume that a social group has never heard of racism, can it occur?

- The physical versus cultural differences in the racial inequality cases?

- The biological peculiarities of the different races?

- Do we carry the cultural heritage of our race?

- Interracial marriage through the lens of Biology.

- The origins of the racial concept and its evolution.

- The core ways how slavery has changed the African-American population.

- The linguistic peculiarities of the Latin people.

- The resistance of the different races towards vaccination.

Modern Racism Topics to Consider

In case you would like to deal with a modern subject that deals with racism, you can go beyond the famous Black Lives Matter movement by focusing on the cases of racism in sports or talking about the peacemakers or the famous celebrities who have made a solid difference in the elimination of racism.

- The Global Citizen campaign is a way to eliminate racial differences.

- The heritage of Aretha Franklin and her take on the racial challenges.

- The role of the Black Stars in modern society: the pros and cons.

- Martin Luther King Day in the modern schools.

- How can Instagram help to eliminate racism?

- The personality of Michelle Obama as a fighter for peace.

- Is a society without racism a utopian idea?

- How can comic books help youngsters understand equality?

- The controversy in the death of George Floyd.

- How can we break down the stereotypes about Mexicans in the United States?

Racial Discrimination Essay Ideas

If your essay should focus on racial discrimination, you should think about the environment and the type of prejudice that you are facing. For example, it can be in school or at the workplace, at the hospital, or in a movie that you have attended. Here are some discrimination topics research paper ideas that will help you to get started:

- How can a schoolchild report the case of racism while being a minor?

- The discrimination against women's rights during the 1960s.

- The employment problem and the chances of the Latin, Asian, and African American applicants.

- Do colleges implement a certain selection process against different races?

- How can discrimination be eliminated via education?

- African-American challenges in sports.

- The perception of discrimination, based on racial principles and the laws in the United States.

- How can one report racial comments on social media?

- Is there discrimination against white people in our society?

- Covid-19 and racial discrimination: the lessons we have learned.

Find Even More Essay Topics On Racism by Visiting Our Site

If you are unsure about what to write about, you can always find an essay on racism by visiting our website. Offering over 150 topic ideas, you can always get in touch with our experts and find another one!

5 Tips to Make Your Essay Perfect

- Start your essay on racial issues by narrowing things down after you choose the general topic.

- Get your facts straight by checking the dates, the names, opinions from both sides of an issue, etc.

- Provide examples if you are talking about the general aspects of racism.

- Do not use profanity and show due respect even if you are talking about shocking things. The same relates to race and ethnic relations essay topics that are based on religious conflicts. Stay respectful!

- Provide references and citations to avoid plagiarism and to keep your ideas supported by at least one piece of evidence.

Recommendations to Help You Get Inspired

Speaking of recommended books and articles to help you start with this subject, you should check " The Ideology of Racism: Misusing Science to Justify Racial Discrimination " by William H. Tucker who is a professor of social sciences at Rutgers University. Once you read this great article, think about the poetry by Maya Angelou as one of the best examples to see the practical side of things.

The other recommendations worth checking include:

- How to be Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi . - White Fragility by Robin Diangelo . - So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo .

The Final Word

We sincerely believe that our article has helped you to choose the perfect essay subject to stir your writing skills. If you are still feeling stuck and need additional help, our team of writers can assist you in the creation of any essay based on what you would like to explore. You can get in touch with our skilled experts anytime by contacting our essay service for any race and ethnicity topics. Always confidential and plagiarism-free, we can assist you and help you get over the stress!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

40+ Argumentative Essay Topics on Racism Worth Exploring

by Antony W

April 21, 2023

The first step to write an essay on racism is to select the right topic to explore.

You then have to take a stance based on your research and use evidence to defend your position.

Even in a sensitive issue of racial discrimination, you have to consider the counterarguments highly likely to arise and address them accordingly.

The goal of this list post is to give you some topic ideas that you can consider and explore. We’ve put together 30+ topic ideas, so it should be easy to find an interesting issue to explore.

What is Racism?

Racism is the conviction that we can credit capacities and qualities to individuals based on their race, color, ethnicity, or national origin. It can take the form of prejudice, hatred, and discrimination, and it can happen in any place and at any time.

Racism goes beyond the act of harassment and abuse. It stretches further to violence, intimidation, and exclusion from important group activities.

This act of judgment, prejudice, and discrimination easily reveal itself in the way we interact with people and our attitude towards them.

Some forms of racism , like looking at a person’s place of origin through a list of job applications, may not be obvious, but they play a part in preventing people or particular group from enjoying the dignity and equality of the benefits of life simply because they are different.

Argumentative Essay Topics on Racism

- Is racism a type of mental illness in the modern society?

- Barrack Obama’s legacy hasn’t helped to improve the situation of racism in the United States of America

- The women’s movement of the 1960s did NOT unite black and white women

- Will racism eventually disappear on its own?

- Is there a cure for racism?

- There’s no sufficient evidence to prove that Mexicans are racists

- Is the difference in skin color the cause of racism in the western world?

- Racism isn’t in everyone’s heart

- Racism is a toxic global disease

- Will the human race ever overcome racial prejudice and discrimination?

- Can a racist be equally cruel?

- Should racism be a criminal offense punishable by death without the possibility of parole?

- Are racists more principled than those who are not?

- Can poor upbringing cause a person to become a racist?

- Is it a crime if you’re a racist?

- Can racism lead to another World War?

- The government can’t stop people from being racists

- Cultural diversity can cure racism

- All racists in the world have psychological problems and therefore need medical attention

- Can the government put effective measures in place to stop its citizens from promoting racism?

- Can a racist president rule a country better than a president who is not a racist?

- Should white and black people have equal rights?

- Can cultural diversity breed racism?

- Is racism a bigger threat to the human race?

- Racism is common among adults than it is among children

- Should white people enjoy more human rights than black people should?

- Is the disparity in the healthcare system a form of racial discrimination?

- Racial discrimination is a common thing in the United States of America

- Film industries should be regulated to help mitigate racism

- Disney movies should be banned for promoting racism

- Should schools teach students to stand against racism?

- Should parents punish their children for manifesting racist traits?

- Is racism the root of all evil?

- Can dialogue resolve the issue of racism?

- Is the seed of racism sown in our children during childhood?

- Do anti-racist movements help to unite people of different colors and race to fight racism?

- Do religious doctrines promote racism?

- There are no psychological health risks associated with racism

- Can movements such as Black Lives Matter stop racism in America?

- Do anti-racist movements help people to improve their self-esteem?

- Racism is against religious beliefs

- Can teaching children to treat each other equally help to promote an anti-racist world?

We understand that racism is such a controversial topic. However, it’s equally an interesting area to explore. If you wish to write an essay on racism but you have no idea where to start, you can pay for argumentative essay from Help for Assessment to do some custom writing for you.

If you hire Help for Assessment, our team will choose the most suitable topic based on your preference. In addition to conducting extensive research, we’ll choose a stance we can defend, and use strong evidence to demonstrate why your view on the subject is right. Get up to 15% discount here .

Is it Easy to Write an Argumentative Essay on Racism?

Racism is traumatic and a bad idea, and there must never be an excuse for it.

As controversial as the issue is, you can write an essay that explores this aspect and bring out a clear picture on why racism is such a bad idea altogether.

With that said, here’s a list of some argumentative essay topics on racism that you might want to consider for your next essay assignment.

How to Make Your Argumentative Essay on Racism Great

The following are some useful writing tips that you can use to make your argumentative essay on racism stand out:

Examine the Historical Causes of Racism

Try to dig deeper into the topic of racism by looking at historical causes of racial discrimination and prejudices.

Look at a number of credible sources to explore the connection between racism and salve trade, social developments, and politics.

Include these highlights in your essay to demonstrate that you researched widely on the topic before making your conclusion.

Demonstrate Critical Thinking

Go the extra mile and talk about the things you believe people often leave out when writing argumentative essays on racism.

Consider why racial discrimination and prejudices are common in the society, their negative effects, and who benefits the most from racial policies.

Adding such information not only shows your instructor that you did your research but also understand the topic better.

Show the Relationship between Racism and Social Issues

There’s no denying that racism has a strong connection with many types of social issues, including homophobia, slavery, and sexism.

Including these links, where necessary, and explaining them in details can make your essay more comprehensive and therefore worth reading.

related resources

- Argumentative Essay Topics on Medicine

- Argumentative Essay Topics About Animals

- Music Argumentative Essay Topics

- Social Media Argumentative Essay Topics

- Technology Argumentative Essay Topics

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

📕 Studying HQ

List of great argumentative essay topics on racism [updated], bob cardens.

- August 1, 2022

- Essay Topics and Ideas , Samples

The social issues that we face today are more complex and multifaceted than ever before. And, as a result, there are a lot of great argumentative essay topics on racism. Here are just a few examples:

What You'll Learn

Argumentative Essay Topics on Racism

- How has institutional Racism affected the history of minority groups in the US? –

- Should we consider Islamophobia racism?

- Racism: Can we refer to it as a mental disorder?

- Race: Does it serve any purpose in modern society?

- How Racism impact the way Chinese American has been viewed.

- Irishness: Should it be considered a show of racism?

- Comic books: Can we consider it racist against black people?

- How does Racism impact the way we view immigration? Description: In recent years, views of immigration in the United States have shifted with many Americans perceiving immigrants as a source of national prosperity, rather than an eminent burden

- Racism Against Hispanics in America Description: One of the main challenges facing American society is racism. While the country is a multicultural society comprising of individuals from different cultures around the world, minority groups often face discrimination in the form hate crimes and racist comments. Although the issue of racism affects all minorities.

- African American males are 10 times more likely to resist arrest than Caucasian males, is this due to them essentially resisting police brutality, or are other factors at play?

- What is the driving force of racial police brutality?

- Is defunding the police an effective way to end racial police brutality?

- Racism. Discrimination and racial inequality. Essay Description: Today, everyone wants to reap the benefits of a diverse workforce. However, racism continues to be a major challenge to achieving this goal.

- Prejudice towards ladies in hijab: Is it baseless?

- Racism: Is it rooted in fear?

As you continue, thestudycorp.com has the top and most qualified writers to help with any of your assignments. All you need to do is place an order with us

Argumentative Essay Ideas on Racism

- Does police brutality exist for other ethnicities other than African Americans?

- Do prisons treat Caucasians differently than other ethnic groups?

- Should prisons be segregated by race?

- Educational Institutions take to Address Systemic Racism Description: Racism is a social issue that has existed for a long time, causing chaos among people from various races. It refers to discriminating against a person based on skin colour and ethnicity. Systematic racism, sometimes called institutional racism, refers to racism embedded in the regulations.

- What countries are the most racist in the EU?

- Do you agree with the statement, “there will always be color racism?”

- Prejudice and racism: Are they the same thing?

- What can be done to create pathways for more minority judges to take the bench?

- Does Islamophobia separate minority populations in prison?

- Is enough being done in the legal system to deter and punish hate crimes?

- Should there be a zero-tolerance policy for racially biased police brutality?

- Racial Discrimination: How We Can Face Racism Description: One of the most effective approaches to face racism and defeat it is through teaching the people its detrimental effects and how each one of us can be an agent of change. (Argumentative Essay Topics on Racism)

Theories of race and racism in an Administration of Justice, Criminal Justice race, gender and Class

These are just a few examples – there are literally endless possibilities when it comes to racism that you can write about in an argumentative essay . So, if you’re looking for some inspiration, don’t hesitate to check out these Research Paper Ideas on Racism with prompts!

Research Paper Ideas on Racism with prompts

- Xenophobia, Racism and Alien Representation in District 9 Prompt: The term alien has many connotations for different people, from the scientific theory and sci-fi representations of extra-terrestrial life to the resurgence in modern society of legal uses regarding immigration. In popular culture these uses can often coincide whether metaphorical, allegorical, or explicit.

- White and Black Team in Remember the Titans Prompt: Reducing prejudice essentially entails changing the values and beliefs by which people live. For many reasons, this is difficult. The first is that the ideals and expectations of individuals are also a long-standing pillar of their psychological stability.

- Transformation of the American Government and “Tradition of Exclusion” Prompt: The United States of America is a country known for its pride in its democratic government, where the American Dream encourages everyone to strive for the very best. That rhetoric is deeply rooted in every aspect of life in this country from its conception until…

- This is America: Oppression in America in Glover’s Music Video Prompt: A common topic we see in our society is the debate of gun control in America. It has been an ongoing argument due to the mass of shootings in schools, churches, nightclubs, etc. The number of shootings has only been increasing over the years.

- Theory of Slavery as a Kind of Social Death Prompt: The Orlando theory of slavery as a social death is among the first and major type of full-scale comparative study that is attached to different slavery aspects.

- The Review of the Glory Road Prompt: Glory Road is an American sports drama film directed by James Gartner, in view of a genuine story encompassing the occasions of the 1966 NCAA University Division Basketball Championship. It was released on 13th January 2006.

- The Relationship Between Racism and the Ideology of Progress Prompt: Through the years, as a result of the two world wars and the Great Depression, the term progress and the meaning attached to it greatly suffered.

- The Racial Discrimination in Bob Dylan’s Song Prompt: President John F. Kennedy delivered a powerful message to the American People on June 11th of 1963, calling Congress to view civil rights as a moral obligation instead of a legal issue.

- The People Segregation by Society in Divergent Prompt: It is clear that the society in Divergent places unrealistic limits on its members identities from the beginning of the book. Segregating different personality types into different factions not only has consequences on society but on the individual.

- The Influence of Racial Or Ethnic Discrimination a Person’s Self-concept Prompt: Discrimination and prejudiced attitudes are assumed to be damaging aspects of society. The research presents the cognitive, emotional, and social damages related to experiencing discrimination. This research proposal focuses on determining the impacts of prejudice and how it negatively affects an individual. (Argumentative Essay Topics on Racism)

- Find out more on Argumentative Essay Topics About Social Media [Updated]

Racism research paper outline

![List of great argumentative essay topics on racism [updated] 1 The social issues that we face today are more complex and multifaceted than ever before. And, as a result, there are a lot of great argumentative essay topics on racism. Here are just a few examples: racism research paper outline](https://i0.wp.com/studyinghq.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/image.png?resize=736%2C852&ssl=1)

Research Questions on Racism

- Have you seen the video of George Floyd’s death? What was your reaction to it? How did it make you feel?

- How would you define racism?

- How have you experienced racism towards yourself or others? How did it make you feel?

- Has anyone ever assumed something about you because of the color or your skin? If so, explain.

- Have you ever assumed something about someone else because of the color of their skin? If so, explain.

- Has anyone ever called you the “N” word or referred to others in that way while you were present? If so, please share what happened.

- Why do you think racism exists in today’s society? How do you think it will affect your future?

- How has the police brutality and the protests/demonstrations impacted you on a personal level?

- Do you feel your relationship with God makes you better equipped to handle all that is going within society concerning race? Why or why not?

- Do you think it is important to celebrate the differences in people? Why or why not?

- Is it important to have oneness in Christ or sameness in Christ? Explain. Do you think there is a difference between the two? Explain.

- How do you think we can move forward and carry out racial reconciliation as a society?

Great Racism Research Paper Topics

- What are the effects of racism on society?

- How can we stop racism from spreading in contemporary society?

- The mental underpinnings of racism

- How does racism impact a person’s brain?

- Amounts of racism in various social groups

- The importance of socialization in racial and ethnic groups

- How does racial tension affect social interactions?

- The following are some ideas for essays on racism and ethnicity in America.

- Interethnic conflict in the United States and other countries

- Systematic racism exists in America.

- Racism is prevalent in American cities.

- The rise of nationalism and xenophobia in America.

- Postcolonial psychology essay topics for Native Americans

- Latin American musical ethnography issues.

- Legacy of Mesoamerican Civilizations

- Endangered Native American languages

- What steps are American businesses taking to combat racism?

- The role of traditionalism in contemporary Latin American society

- Ethnopolitical conflicts and their resolutions are good topics for African American research papers.

- The prevalence of racism in hate crimes in the US.

- Latin America Today: Religion, Celebration, and Identity

- National politics of African Americans in contemporary America.

Good racism essay topics:

- Why Should We Consider Race to Understand Fascism?

- The Racial Problem in America

- Postwar Race and Gender Histories: The Color of Sex

- The Relevance of Race in Fascism Understanding

- Cases of Racial Discrimination in the Workplace in the United States

- Problems with Gender, Race, and Sexuality in Modern Society

- “Frankie and Alice”: Race and Mental Health

- The history of immigration, race, and labor in America

- Power and racial symbolism in Coetzee’s “Disgrace.”

- In America, race and educational attainment are related.

- Race to the Top: The Early Learning Challenge

- Social learning, critical racial theory, and feminist theories

- Minority Crime and Race in the United States

- Racial, ethnic, and gender diversity in society

- Documentary series “Race: The Power of an Illusion.”

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Have a subject expert write for you now, have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, popular topics.

Business StudyingHq Essay Topics and Ideas How to Guides Samples

- Nursing Solutions

- Study Guides

- Free Study Database for Essays

- Privacy Policy

- Writing Service

- Discounts / Offers

Study Hub:

- Studying Blog

- Topic Ideas

- How to Guides

- Business Studying

- Nursing Studying

- Literature and English Studying

Writing Tools

- Citation Generator

- Topic Generator

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Maker

- Research Title Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Summarizing Tool

- Terms and Conditions

- Confidentiality Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Refund and Revision Policy

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Contact Us:

📞 +15512677917

2012-2024 © studyinghq.com. All rights reserved

Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century

Doing Race focuses on race and ethnicity in everyday life: what they are, how they work, and why they matter. Going to school and work, renting an apartment or buying a house, watching television, voting, listening to music, reading books and newspapers, attending religious services, and going to the doctor are all everyday activities that are influenced by assumptions about who counts, whom to trust, whom to care about, whom to include, and why. Race and ethnicity are powerful precisely because they organize modern society and play a large role in fueling violence around the globe. Doing Race is targeted to undergraduates; it begins with an introductory essay and includes original essays by well-known scholars. Drawing on the latest science and scholarship, the collected essays emphasize that race and ethnicity are not things that people or groups have or are, but rather sets of actions that people do. Doing Race provides compelling evidence that we are not yet in a “post-race” world and that race and ethnicity matter for everyone. Since race and ethnicity are the products of human actions, we can do them differently. Like studying the human genome or the laws of economics, understanding race and ethnicity is a necessary part of a twenty first century education.

About the Author

PAULA M. L. MOYA, is the Danily C. and Laura Louise Bell Professor of the Humanities and Professor of English at Stanford University. She is the Burton J. and Deedee McMurtry University Fellow in Undergraduate Education and a 2019-20 Fellow at the Center for the Study of Behavioral Sciences.

Moya’s teaching and research focus on twentieth-century and early twenty-first century literary studies, feminist theory, critical theory, narrative theory, American cultural studies, interdisciplinary approaches to race and ethnicity, and Chicanx and U.S. Latinx studies.

She is the author of The Social Imperative: Race, Close Reading, and Contemporary Literary Criticism (Stanford UP 2016) and Learning From Experience: Minority Identities, Multicultural Struggles (UC Press 2002) and has co-edited three collections of original essays, Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century (W.W. Norton, Inc. 2010), Identity Politics Reconsidered (Palgrave 2006) and Reclaiming Identity: Realist Theory and the Predicament of Postmodernism (UC Press 2000).

Previously Moya served as the Director of the Program of Modern Thought and Literature, Vice Chair of the Department of English, Director of the Research Institute of Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, and also the Director of the Undergraduate Program of the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity.

She is a recipient of the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, a Ford Foundation postdoctoral fellowship, the Outstanding Chicana/o Faculty Member award. She has been a Brown Faculty Fellow, a Clayman Institute Fellow, a CCSRE Faculty Research Fellow, and a Clayman Beyond Bias Fellow.

Essays and Commentary

Reflections and analysis inspired by the killing of George Floyd and the nationwide wave of protests that followed.

My Mother’s Dreams for Her Son, and All Black Children

She longed for black people in America not to be forever refugees—confined by borders that they did not create and by a penal system that killed them before they died.

By Hilton Als

June 21, 2020

How do we change america.

The quest to transform this country cannot be limited to challenging its brutal police alone.

By Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

June 8, 2020

The purpose of a house.

For my daughters, the pandemic was a relief from race-related stress at school. Then George Floyd was killed.

By Emily Bernard

June 25, 2020

The players’ revolt against racism, inequality, and police terror.

A group of athletes across various American professional sports have communicated the fear, frustration, and anger of most of Black America.

September 9, 2020, until black women are free, none of us will be free.

Barbara Smith and the Black feminist visionaries of the Combahee River Collective.

July 20, 2020, john lewis’s legacy and america’s redemption.

The civil-rights leader, who died Friday, acknowledged the darkest chapters of the country’s history, yet insisted that change was always possible.

By David Remnick

July 18, 2020

Europe in 1989, america in 2020, and the death of the lost cause.

A whole vision of history seems to be leaving the stage.

By David W. Blight

July 1, 2020

The messy politics of black voices—and “black voice”—in american animation.

Cartoons have often been considered exempt from the country’s prejudices. In fact, they form a genre built on the marble and mud of racial signification.

By Lauren Michele Jackson

June 30, 2020

After george floyd and juneteenth.

What’s ahead for the movement, the election, and the protesters?

June 20, 2020, juneteenth and the meaning of freedom.

Emancipation is a marker of progress for white Americans, not black ones.

By Jelani Cobb

June 19, 2020

A memory of solidarity day, on juneteenth, 1968.

The public outpouring over racism that has been taking place in America since George Floyd’s murder feels like a long-postponed renewal of the reckoning that shook the nation more than half a century ago.

By Jon Lee Anderson

June 18, 2020

Seeing police brutality then and now.

We still haven’t fully recognized the art made by twentieth-century black artists.

By Nell Painter

The History of the “Riot” Report

How government commissions became alibis for inaction.

By Jill Lepore

June 15, 2020

The trayvon generation.

For Solo, Simon, Robel, Maurice, Cameron, and Sekou.

By Elizabeth Alexander

So Brutal a Death

Nationwide outrage over George Floyd’s brutal killing by police officers resonates with immigrants, and with people around the world.

By Edwidge Danticat

An American Spring of Reckoning

In death, George Floyd’s name has become a metaphor for the stacked inequities of the society that produced them.

June 14, 2020, the mimetic power of d.c.’s black lives matter mural.

The pavement itself has become part of the protest.

By Kyle Chayka

June 9, 2020

Donald trump’s fascist performance.

To the President, power sounds like gunfire and helicopters; it sounds like the silence of men in uniform when they are asked who they are.

By Masha Gessen

June 3, 2020

- Books & Culture

- Fiction & Poetry

- Humor & Cartoons

- Puzzles & Games

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Ideas of Race and Racism in History

About this episode, youtube video.

- Nicholas Breyfogle

Guests Alice L. Conklin Hasan Kwame Jeffries Robin Judd Deondre Smiles

The issues of race and racism remain as urgent as ever to our national conversation. Four scholars discuss such questions as: Since Race does not exist as a biological reality, what then is race and where did the idea develop from? What is racism? How have race and racism been used by societies to justify discrimination, oppression, and social exclusion? How did racism manifest in different national and historical contexts? How have American and World history in the modern eras been defined by ideas of race and the power hierarchies embedded in racism?

- Nicholas Breyfogle | Associate Professor, Department of History; Director, Goldberg Center, The Ohio State University

- Alice Conklin | Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor, Department of History, The Ohio State University

- Robin Judd | Associate Professor, Department of History, The Ohio State University

- Hasan Jeffries | Associate Professor, Department of History, The Ohio State University

- Deondre Smiles | Ph.D. Geography '20; Assistant Professor of Geography, University of Victoria, Canada

This content is made possible, in part, by Ohio Humanities, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this content do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Cite this Site

Dr. Nicholas Breyfogle

Hello, and welcome to Ideas of Race and Racism in History brought to you by the history department Clio Society, the College of Arts and Sciences at The Ohio State University and by the Bexley Public Library. My name is Nick Breyfogle. I'm an associate professor of history and director of the Goldberg Center for Excellence in Teaching, and I'll be your host and moderator today. Thank you for joining us. The issues of race and racism have a long history in the United States and around the world, and they remain as urgent as ever to our national conversation. Today we'll take part in the discussion among four scholars, Alice Conklin, Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Deondre Smiles, and Robin Judd. We'll explore the ways in which understanding the history of race and racism can help us as we navigate these issues today. They'll discuss such questions as, since race doesn't exist as a biological reality, what is race? And where did the idea develop from? And when, for that matter also? How have race and racism been used by societies to justify discrimination, oppression and social exclusion? And how does racism manifest in different national historical contexts? However, American and world history in the modern era has been defined by ideas of race and the power hierarchies embedded in racism. With that introduction, let me lay out the plan. Each of our panelists will speak for a few minutes on questions of race and racism, historically, each exploring a different topic. And I'll introduce them before they speak. Then, they will take your questions, and we'll open things up for discussion. If you're interested in asking a question, please write it in the Q&A function just at the bottom of your screen at any time. We received several questions in advance when people signed up and registered, and we'll do our best to answer as many questions as we can in the time we have. Now, let's begin with Dr. Alice Conklin, who will discuss the science of race and how race developed as a scientific concept. Dr. Conklin is a professor of history at The Ohio State University, and a cultural, political and intellectual historian of modern France and its empire with the focus on the 20th century. She's currently working on a transnational history of French anti-racism between 1945 and 1965. Let me hand the microphone over to you, Alice.

Dr. Alice Conklin

Thank you, Nick. First, a big thanks to the Origins team who came up with the idea of having this webinar. I will briefly speak about the modern history of the idea of race in the West, and particularly the role that colonialism and science together played in creating and perpetuating what we can agree is a bad, but powerful idea. And race is not just a bad but powerful idea. It is also in the long sweep of history, a relatively recent invention. Those in a nutshell will be my themes today, in these brief remarks, that the very idea of race was invented in the West quite recently, that it is pernicious, and that it remains powerful. When we understand how the very idea of different races came into existence. We understand, in part, why racism remains so difficult to dislodge. The history of the idea of race in the West is a huge topic. To tackle it in the five minutes I have, I want to make three main points.

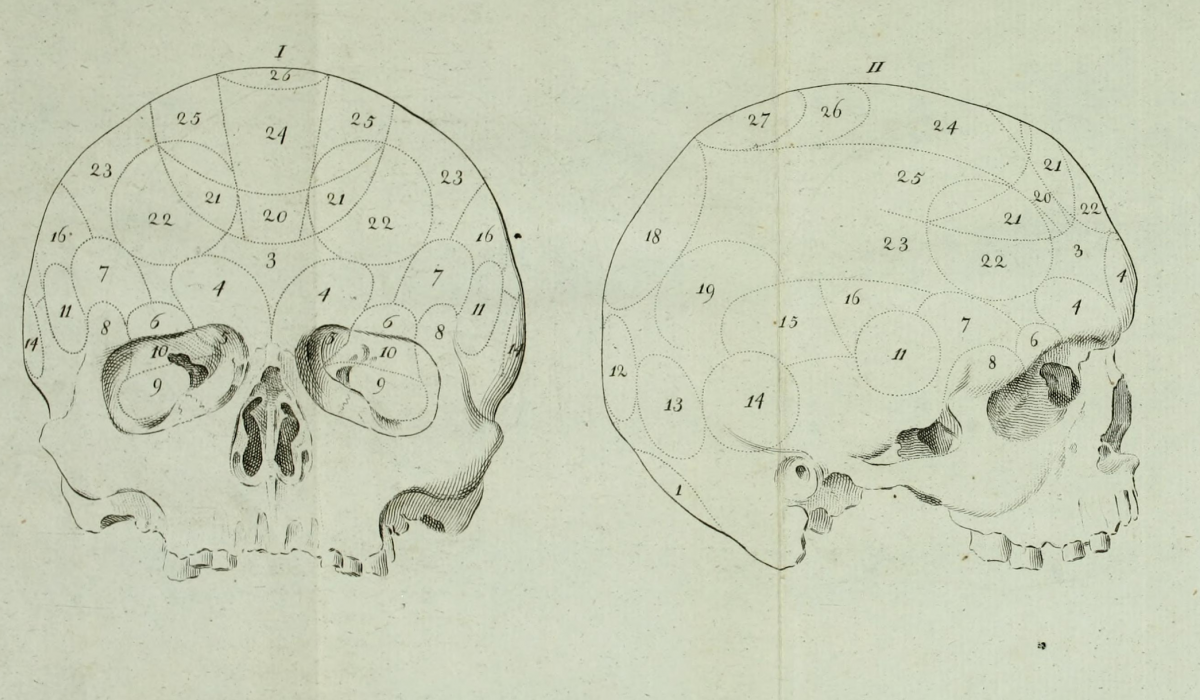

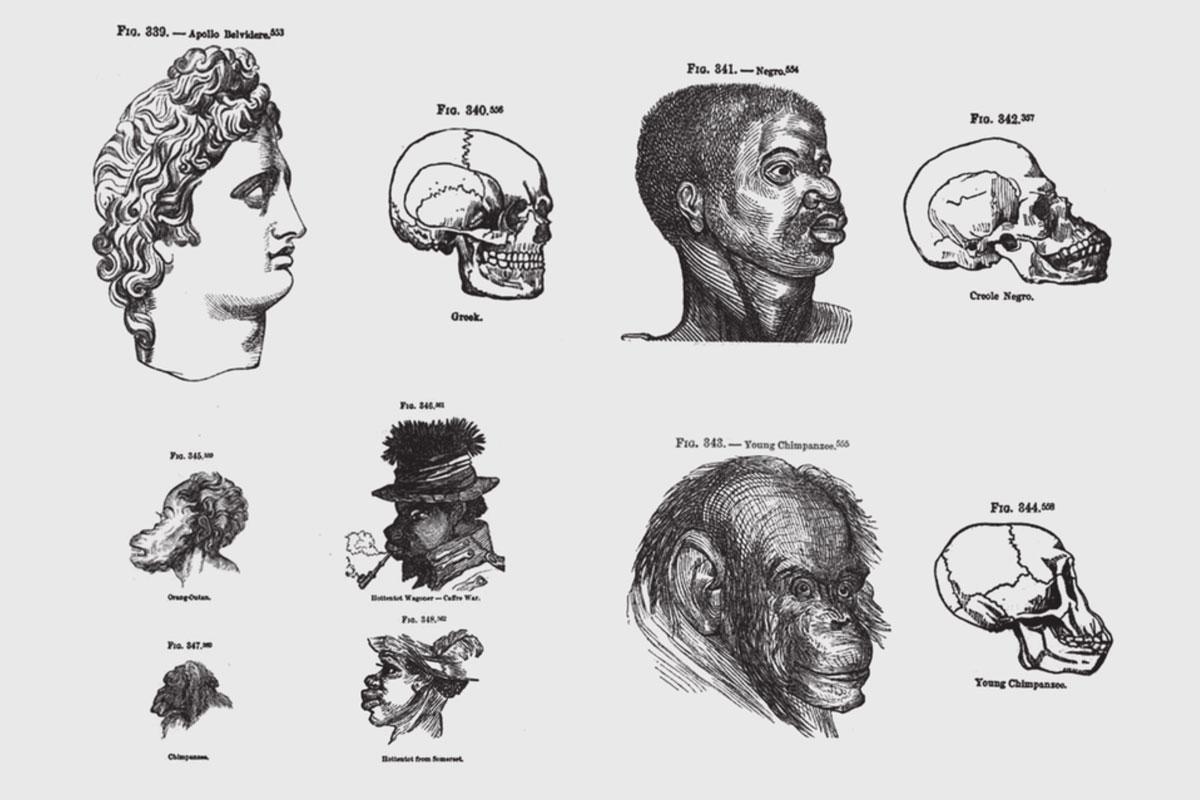

These are first, the idea of race as something biologically real came into existence first as a folk idea and then as a scientific one. This idea was arguably the greatest error modern Western science ever made. Second, the scientific idea of race was an error because it was based on three false premises. These were one that biologically distinct races existed in nature. Two that some races were more intelligent than others. And three, these races could be classified and ranked from superior to inferior, according to the typical brain shape, weight, or size for each so-called race. In these scientific classifications, white Caucasians were always on top, black groups on the bottom. My third point today will be that many reputable scientists clung to these flawed premises and kept trying to classify and rank peoples long after their own best evidence began showing that their hypotheses were wrong. In so doing, these experts gave the backing, the prestige, the authority of science, to the most vicious prejudices circulating in society. Let me begin with a few facts. Traditionally, we answer the question of how did the race idea begin by looking at the history of colonial expansion into the Americas. When Europeans first crossed the Atlantic, they viewed Indigenous peoples as nations, not races. By the mid-17th Century, however, colonial leaders had relegated Africans alone to a status of permanent slavery. In order to justify this new colonial form of slavery, planters in places like Virginia helped to pioneer informally a new idea, that of race. Colonial leaders began to homogenize all Europeans, regardless of ethnicity, or status or social class, into a single novel category. White people of African descent were similarly homogenized into the category of black. In this system, physical features became markers of social status. Historians call this informal idea of race, a folk idea of race. There was nothing scientific about it. Yet of race ideology developed as a folk idea, it was soon imported into science, or to be more precise, it was imported into the scientific outlook, known as the enlightenment. In other words, the first modern scientists did not invent the race concept. Slave-based colonialism had already done that. But by the end of the 18th century, enlightened naturalist turned to science to rationalize the inhumanity of slavery that had developed in the Americas. These thinkers began arguing that nature itself provided a justification for this new social order that granted privileges to all whites, and relegated Africans to perpetual servitude.

Enlightenment scientists soon eagerly took up a whole series of questions with race at their center. They asked questions like, are all races fully human? Are all races equal? They also gave themselves the task of ranking the races of humankind on the basis of intelligence. Since classification was considered the basis of all good science. None of them questioned the biological reality of races or the superiority of white Europeans as establishing these rankings became the basis of a new professional discipline, anthropology where the science of humanity, the 19th century, saw the full flowering of the science. And it was science in the sense that it met the best scientific standards of the day. The science, moreover, leached out into society. Thanks to the invention of photography, of museums, of the penny press, and the violent colonization of Africa and large parts of Asia that took place over the course of the 19th century, the race classifications that appeared in scientific journals became fatally easy to disseminate visually to a wider public. People became used to seeing images of beauty and intelligence that correlated with whiteness, other so-called races of the world might be presented as noble, or romantic. Certainly, they were exotic, but they were always presented as inferior, a view that the best science of the day endorsed. Alas, many of these images are still with us.

Let me now fast forward. By the end of World War II, for complex reasons, science began to correct itself and abandon the belief that race was biologically real, and that races could be placed in a fairly firm racial hierarchy. Scientists today of course, recognize that there is no gene or cluster of genes common to all blacks, or all whites. To conclude, science in the West managed for a long time to convince ordinary people that race was biologically real, when it wasn't and isn't. human races are not biological units. Races are social constructs. Human race exists solely because we humans created them, and only in the forms in which we perpetuate them. Historically, race has never been just a matter of creating categories of people. It has always been a matter of creating hierarchies. And when it came to creating racial hierarchies, Western colonialism and Western science have a lot to answer for. Thank you.

Thank you, Alice very much for those great introductory remarks and really fascinating inspiration of the kind of origins of the modern ideas of race and racism. Our next panelist is Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries who will speak to us today about race and the black experience in American history. Dr. Jeffries is an associate professor of history in the Department of History at The Ohio State University, where he teaches courses on the African American freedom struggle. He's the editor of the award-winning collection of essays, Understanding and Teaching the Civil Rights Movement He earned his B.A. from Morehouse College, his Ph.D. from Duke University. I'll pass you over to Hasan now. Thank you.

Dr. Hasan Jeffries

Well, thank you very much, Nick. It is a real delight and pleasure to be able to be a part of this conversation, especially at this particular moment in time, I just want to go ahead and jump right into my remarks. I'm so glad that we left off with Dr. Conklin laying out the basic groundwork that this idea of race just simply isn't real. It is not real in a biological sense. But at the same time, as she pointed out, it is socially meaningful, so biologically meaningless, but socially meaningful, because it has structured global society for the last 500, 600 years. And it all, it is also culturally relevant. Because we use race today and have used it certainly in the American context, as a stand in for cultural heritage, and for cultural ancestry. Which is why we cannot pretend as though race itself isn't a meaningful, impactful construct in the lives of all people, and certainly all Americans.

But while race isn't biologically real, racism is absolutely real. And it has deep roots in the American experience, and has shaped the lives of all Americans dating back to the founding of this nation, and the original colonial endeavor. 1619. We've heard so much about 1619 over the last year or so, last two years. 1619 marks the year in which the first group of enslaved Africans were brought to British North America, brought to Virginia and that really is an important moment in what would become the American journey. Because a decision is made or choices made to embrace the enslavement of people based on, for economic necessity, for economical, rather economic advantage, exploitation based on this idea of race. And so we see at this moment in 1619, that literally embedded in our DNA as what will become a nation, or is racism, intertwined with capitalism. I mean, that is literally in our DNA, because it serves as a justification for the enslavement of this critical labor force. It also serves as justification for the taking of land for those who were already present here. It is the justification for what would be the institution of slavery that would last for two-and-a-half centuries.

In America, we also see that racism is embedded in our founding documents, the 1776 Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson, who absolutely says all men are created equal. But that's because he does not have to qualify it with a racial qualifier. He does not have to say all white people, because he knows, everyone knows he's just talking about white men. He doesn't have to say all white men, because everyone knows he's not talking about women. Thomas Jefferson has a very rich history with the colorline and is one of the people in America who really lays the groundwork for a scientific rationalization of what racism was. So we see it embedded in our founding documents.

Same way with the Constitution, the father of it is James Madison, a person who, like Jefferson, enslaved 100 or so people over the course of his lifetime and never freed a single soul. So we see it embedded in our founding documents. Now there are times such as here in Ohio, it comes into the union, that we think we are on the right side of history. Ohio comes into the union and 1803 and rejects the institution of slavery, but not because it rejected the idea of racism, not because the those white men who were in the, who brought Ohio into the union, rejected white supremacy. They just didn't want black people here. So there are times when we see we are on the right side of history as a nation. But for the wrong reasons, racism and white supremacy specifically, was something that really impacted the entire nation. When we get to the Civil War, which was absolutely fought about maintaining the institution of slavery in the states where it existed, and having the opportunity to expand it in the places where it wasn't. For the West, we see that once that battle is over, racism doesn't end. In fact, the principal legacy of the institution of slavery, North and South was the persistence in the belief in of white supremacy.

And so we see that white supremacy as a shared national ideology would go on into the late 19th Century, early 20th Century, serving as the justification for the for new systems of labor, exploitation of African Americans, that being Jim Crow, and all of it is enforced by violence. And so we also see in this moment of the 20th century, just as violence was a cornerstone of the institution of slavery, violence was the cornerstone of the new freedom. And so this becomes the era of lynching. And all of it is justified by these myths connected to race, whether it's black criminality, or black brutality, right? It all connects to this idea that somehow dark skin, darker skin, non-European ancestry leads to this inherent danger among African Americans or by African Americans. We also see as we move into the 20th century, during the era of Jim Crow, and just one more to two more quick comments, that we see how racism becomes embedded in our broader society. Whether we're talking about the criminal justice system and convict leasing, whether we're talking about homeownership in the New Deal, whether we're talking about segregated schools, these aren't just personal decisions that are being made by white folk in America. These are systems that are put in place, that are designed to disadvantage African Americans for the purpose of providing basic privileges for white Americans.

In 1965 1964, the Civil Rights Movement does not end racism in America. It certainly does outlaw and end legal racial discrimination. But just as white supremacy continued after slavery, a belief in white supremacy, a belief in racism continued after the Civil Rights era. Now the language that we use certainly changes by individuals, and we move into this era of colorblind legislation, but we still see purposeful actions and intent in legislation and business decisions and the like. But we also see the legacy of racism being the implicit biases that we harbor. And so even if we were to eliminate thoughtful or purposeful racial discrimination on the part of some, we still internalize this legacy of racist beliefs, not because we were born, anyone in this world was born racist, or harboring racist views, but because we were born in a society that normalizes racism and racist views. That is the problem. We haven't fundamentally changed that. So I'll just end simply by saying we are in the midst of a national conversation and national debate which we think we need to be having about whether or not we should be talking about race or racism. And the answer to that is a simple absolutely, because both race and racism continue to shape the contours of the lives of every single person. And you cannot understand the problems that we face as a society today, unless we take seriously race and racism, just as we can't understand the problems of yesterday, unless we understand race and racism, and the role of race and racism. And we certainly can't solve the problems that our children are going to be facing in the future unless we take seriously the role of race and racism in society. So thank you very much, and I turn it back over to Nick.

Thank you very much, Hasan. Our next speaker is Dr. Deondre Smiles, who'll discuss issues of race and racism in the context of Native Americans and Indigenous peoples. Dr. Smiles is a member of the Lekwungen Band of Ojibwe. He is an assistant professor of geography at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. Smiles' research centers around conversations of the political role of the Indigenous deceased in relationships between Indigenous communities and the state. Smiles also has broader interests in critical Indigenous geographies, political ecology, science and technology studies and tribal cultural resource preservation. Smiles earned his Ph.D. in geography from the Ohio State University, where he also spent a year as a President's Postdoctoral Scholar in the history department. I'll pass the floor over to Deondre.

Dr. Deondre Smiles