An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE Open Med

Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers

Ylona chun tie.

1 Nursing and Midwifery, College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

Melanie Birks

Karen francis.

2 College of Health and Medicine, University of Tasmania, Australia, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Background:

Grounded theory is a well-known methodology employed in many research studies. Qualitative and quantitative data generation techniques can be used in a grounded theory study. Grounded theory sets out to discover or construct theory from data, systematically obtained and analysed using comparative analysis. While grounded theory is inherently flexible, it is a complex methodology. Thus, novice researchers strive to understand the discourse and the practical application of grounded theory concepts and processes.

The aim of this article is to provide a contemporary research framework suitable to inform a grounded theory study.

This article provides an overview of grounded theory illustrated through a graphic representation of the processes and methods employed in conducting research using this methodology. The framework is presented as a diagrammatic representation of a research design and acts as a visual guide for the novice grounded theory researcher.

Discussion:

As grounded theory is not a linear process, the framework illustrates the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and iterative and comparative actions involved. Each of the essential methods and processes that underpin grounded theory are defined in this article.

Conclusion:

Rather than an engagement in philosophical discussion or a debate of the different genres that can be used in grounded theory, this article illustrates how a framework for a research study design can be used to guide and inform the novice nurse researcher undertaking a study using grounded theory. Research findings and recommendations can contribute to policy or knowledge development, service provision and can reform thinking to initiate change in the substantive area of inquiry.

Introduction

The aim of all research is to advance, refine and expand a body of knowledge, establish facts and/or reach new conclusions using systematic inquiry and disciplined methods. 1 The research design is the plan or strategy researchers use to answer the research question, which is underpinned by philosophy, methodology and methods. 2 Birks 3 defines philosophy as ‘a view of the world encompassing the questions and mechanisms for finding answers that inform that view’ (p. 18). Researchers reflect their philosophical beliefs and interpretations of the world prior to commencing research. Methodology is the research design that shapes the selection of, and use of, particular data generation and analysis methods to answer the research question. 4 While a distinction between positivist research and interpretivist research occurs at the paradigm level, each methodology has explicit criteria for the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. 2 Grounded theory (GT) is a structured, yet flexible methodology. This methodology is appropriate when little is known about a phenomenon; the aim being to produce or construct an explanatory theory that uncovers a process inherent to the substantive area of inquiry. 5 – 7 One of the defining characteristics of GT is that it aims to generate theory that is grounded in the data. The following section provides an overview of GT – the history, main genres and essential methods and processes employed in the conduct of a GT study. This summary provides a foundation for a framework to demonstrate the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in a GT study as presented in the sections that follow.

Glaser and Strauss are recognised as the founders of grounded theory. Strauss was conversant in symbolic interactionism and Glaser in descriptive statistics. 8 – 10 Glaser and Strauss originally worked together in a study examining the experience of terminally ill patients who had differing knowledge of their health status. Some of these suspected they were dying and tried to confirm or disconfirm their suspicions. Others tried to understand by interpreting treatment by care providers and family members. Glaser and Strauss examined how the patients dealt with the knowledge they were dying and the reactions of healthcare staff caring for these patients. Throughout this collaboration, Glaser and Strauss questioned the appropriateness of using a scientific method of verification for this study. During this investigation, they developed the constant comparative method, a key element of grounded theory, while generating a theory of dying first described in Awareness of Dying (1965). The constant comparative method is deemed an original way of organising and analysing qualitative data.

Glaser and Strauss subsequently went on to write The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (1967). This seminal work explained how theory could be generated from data inductively. This process challenged the traditional method of testing or refining theory through deductive testing. Grounded theory provided an outlook that questioned the view of the time that quantitative methodology is the only valid, unbiased way to determine truths about the world. 11 Glaser and Strauss 5 challenged the belief that qualitative research lacked rigour and detailed the method of comparative analysis that enables the generation of theory. After publishing The Discovery of Grounded Theory , Strauss and Glaser went on to write independently, expressing divergent viewpoints in the application of grounded theory methods.

Glaser produced his book Theoretical Sensitivity (1978) and Strauss went on to publish Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists (1987). Strauss and Corbin’s 12 publication Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques resulted in a rebuttal by Glaser 13 over their application of grounded theory methods. However, philosophical perspectives have changed since Glaser’s positivist version and Strauss and Corbin’s post-positivism stance. 14 Grounded theory has since seen the emergence of additional philosophical perspectives that have influenced a change in methodological development over time. 15

Subsequent generations of grounded theorists have positioned themselves along a philosophical continuum, from Strauss and Corbin’s 12 theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism, through to Charmaz’s 16 constructivist perspective. However, understanding how to position oneself philosophically can challenge novice researchers. Birks and Mills 6 provide a contemporary understanding of GT in their book Grounded theory: A Practical Guide. These Australian researchers have written in a way that appeals to the novice researcher. It is the contemporary writing, the way Birks and Mills present a non-partisan approach to GT that support the novice researcher to understand the philosophical and methodological concepts integral in conducting research. The development of GT is important to understand prior to selecting an approach that aligns with the researcher’s philosophical position and the purpose of the research study. As the research progresses, seminal texts are referred back to time and again as understanding of concepts increases, much like the iterative processes inherent in the conduct of a GT study.

Genres: traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory

Grounded theory has several distinct methodological genres: traditional GT associated with Glaser; evolved GT associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke; and constructivist GT associated with Charmaz. 6 , 17 Each variant is an extension and development of the original GT by Glaser and Strauss. The first of these genres is known as traditional or classic GT. Glaser 18 acknowledged that the goal of traditional GT is to generate a conceptual theory that accounts for a pattern of behaviour that is relevant and problematic for those involved. The second genre, evolved GT, is founded on symbolic interactionism and stems from work associated with Strauss, Corbin and Clarke. Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that relies on the symbolic meaning people ascribe to the processes of social interaction. Symbolic interactionism addresses the subjective meaning people place on objects, behaviours or events based on what they believe is true. 19 , 20 Constructivist GT, the third genre developed and explicated by Charmaz, a symbolic interactionist, has its roots in constructivism. 8 , 16 Constructivist GT’s methodological underpinnings focus on how participants’ construct meaning in relation to the area of inquiry. 16 A constructivist co-constructs experience and meanings with participants. 21 While there are commonalities across all genres of GT, there are factors that distinguish differences between the approaches including the philosophical position of the researcher; the use of literature; and the approach to coding, analysis and theory development. Following on from Glaser and Strauss, several versions of GT have ensued.

Grounded theory represents both a method of inquiry and a resultant product of that inquiry. 7 , 22 Glaser and Holton 23 define GT as ‘a set of integrated conceptual hypotheses systematically generated to produce an inductive theory about a substantive area’ (p. 43). Strauss and Corbin 24 define GT as ‘theory that was derived from data, systematically gathered and analysed through the research process’ (p. 12). The researcher ‘begins with an area of study and allows the theory to emerge from the data’ (p. 12). Charmaz 16 defines GT as ‘a method of conducting qualitative research that focuses on creating conceptual frameworks or theories through building inductive analysis from the data’ (p. 187). However, Birks and Mills 6 refer to GT as a process by which theory is generated from the analysis of data. Theory is not discovered; rather, theory is constructed by the researcher who views the world through their own particular lens.

Research process

Before commencing any research study, the researcher must have a solid understanding of the research process. A well-developed outline of the study and an understanding of the important considerations in designing and undertaking a GT study are essential if the goals of the research are to be achieved. While it is important to have an understanding of how a methodology has developed, in order to move forward with research, a novice can align with a grounded theorist and follow an approach to GT. Using a framework to inform a research design can be a useful modus operandi.

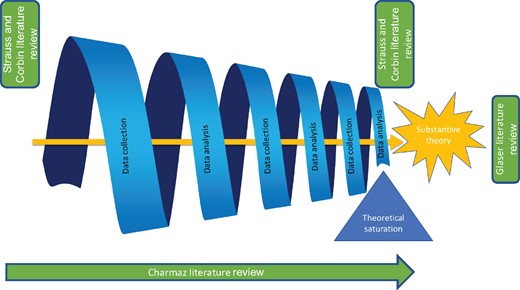

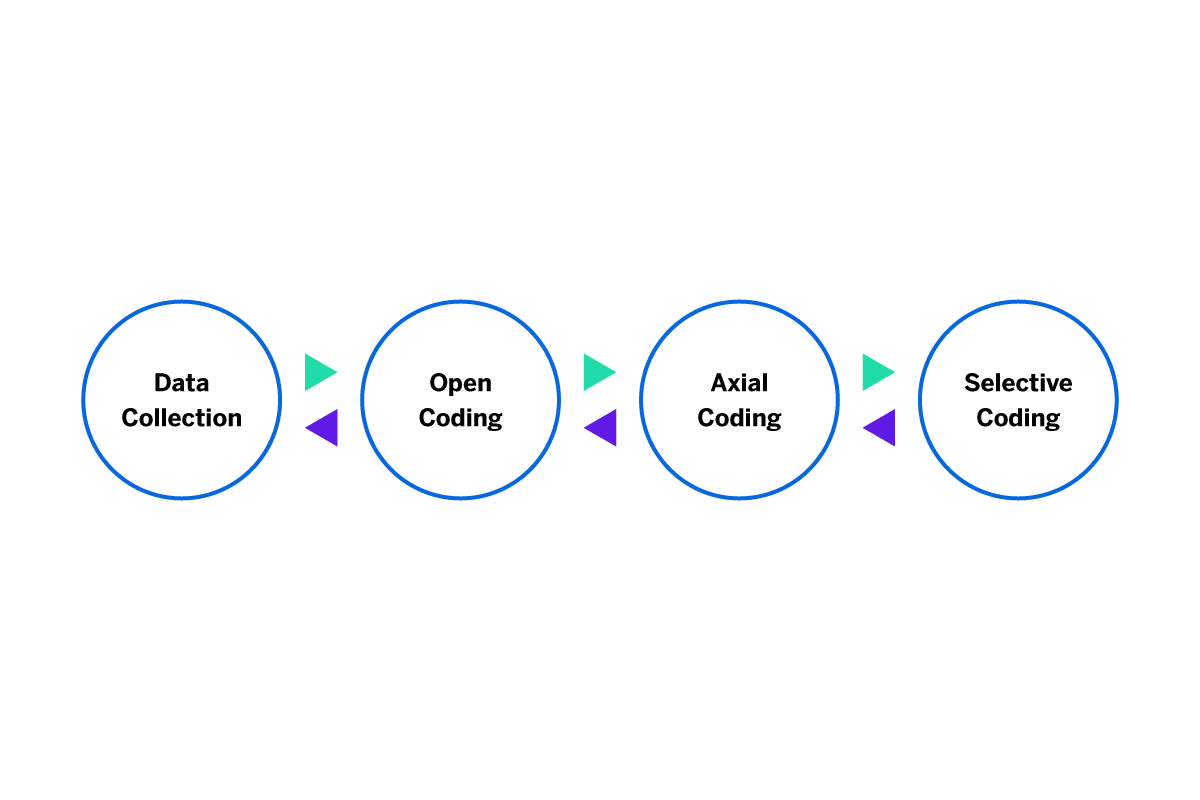

The following section provides insight into the process of undertaking a GT research study. Figure 1 is a framework that summarises the interplay and movement between methods and processes that underpin the generation of a GT. As can be seen from this framework, and as detailed in the discussion that follows, the process of doing a GT research study is not linear, rather it is iterative and recursive.

Research design framework: summary of the interplay between the essential grounded theory methods and processes.

Grounded theory research involves the meticulous application of specific methods and processes. Methods are ‘systematic modes, procedures or tools used for collection and analysis of data’. 25 While GT studies can commence with a variety of sampling techniques, many commence with purposive sampling, followed by concurrent data generation and/or collection and data analysis, through various stages of coding, undertaken in conjunction with constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling and memoing. Theoretical sampling is employed until theoretical saturation is reached. These methods and processes create an unfolding, iterative system of actions and interactions inherent in GT. 6 , 16 The methods interconnect and inform the recurrent elements in the research process as shown by the directional flow of the arrows and the encompassing brackets in Figure 1 . The framework denotes the process is both iterative and dynamic and is not one directional. Grounded theory methods are discussed in the following section.

Purposive sampling

As presented in Figure 1 , initial purposive sampling directs the collection and/or generation of data. Researchers purposively select participants and/or data sources that can answer the research question. 5 , 7 , 16 , 21 Concurrent data generation and/or data collection and analysis is fundamental to GT research design. 6 The researcher collects, codes and analyses this initial data before further data collection/generation is undertaken. Purposeful sampling provides the initial data that the researcher analyses. As will be discussed, theoretical sampling then commences from the codes and categories developed from the first data set. Theoretical sampling is used to identify and follow clues from the analysis, fill gaps, clarify uncertainties, check hunches and test interpretations as the study progresses.

Constant comparative analysis

Constant comparative analysis is an analytical process used in GT for coding and category development. This process commences with the first data generated or collected and pervades the research process as presented in Figure 1 . Incidents are identified in the data and coded. 6 The initial stage of analysis compares incident to incident in each code. Initial codes are then compared to other codes. Codes are then collapsed into categories. This process means the researcher will compare incidents in a category with previous incidents, in both the same and different categories. 5 Future codes are compared and categories are compared with other categories. New data is then compared with data obtained earlier during the analysis phases. This iterative process involves inductive and deductive thinking. 16 Inductive, deductive and abductive reasoning can also be used in data analysis. 26

Constant comparative analysis generates increasingly more abstract concepts and theories through inductive processes. 16 In addition, abduction, defined as ‘a form of reasoning that begins with an examination of the data and the formation of a number of hypotheses that are then proved or disproved during the process of analysis … aids inductive conceptualization’. 6 Theoretical sampling coupled with constant comparative analysis raises the conceptual levels of data analysis and directs ongoing data collection or generation. 6

The constant comparative technique is used to find consistencies and differences, with the aim of continually refining concepts and theoretically relevant categories. This continual comparative iterative process that encompasses GT research sets it apart from a purely descriptive analysis. 8

Memo writing is an analytic process considered essential ‘in ensuring quality in grounded theory’. 6 Stern 27 offers the analogy that if data are the building blocks of the developing theory, then memos are the ‘mortar’ (p. 119). Memos are the storehouse of ideas generated and documented through interacting with data. 28 Thus, memos are reflective interpretive pieces that build a historic audit trail to document ideas, events and the thought processes inherent in the research process and developing thinking of the analyst. 6 Memos provide detailed records of the researchers’ thoughts, feelings and intuitive contemplations. 6

Lempert 29 considers memo writing crucial as memos prompt researchers to analyse and code data and develop codes into categories early in the coding process. Memos detail why and how decisions made related to sampling, coding, collapsing of codes, making of new codes, separating codes, producing a category and identifying relationships abstracted to a higher level of analysis. 6 Thus, memos are informal analytic notes about the data and the theoretical connections between categories. 23 Memoing is an ongoing activity that builds intellectual assets, fosters analytic momentum and informs the GT findings. 6 , 10

Generating/collecting data

A hallmark of GT is concurrent data generation/collection and analysis. In GT, researchers may utilise both qualitative and quantitative data as espoused by Glaser’s dictum; ‘all is data’. 30 While interviews are a common method of generating data, data sources can include focus groups, questionnaires, surveys, transcripts, letters, government reports, documents, grey literature, music, artefacts, videos, blogs and memos. 9 Elicited data are produced by participants in response to, or directed by, the researcher whereas extant data includes data that is already available such as documents and published literature. 6 , 31 While this is one interpretation of how elicited data are generated, other approaches to grounded theory recognise the agency of participants in the co-construction of data with the researcher. The relationship the researcher has with the data, how it is generated and collected, will determine the value it contributes to the development of the final GT. 6 The significance of this relationship extends into data analysis conducted by the researcher through the various stages of coding.

Coding is an analytical process used to identify concepts, similarities and conceptual reoccurrences in data. Coding is the pivotal link between collecting or generating data and developing a theory that explains the data. Charmaz 10 posits,

codes rely on interaction between researchers and their data. Codes consist of short labels that we construct as we interact with the data. Something kinaesthetic occurs when we are coding; we are mentally and physically active in the process. (p. 5)

In GT, coding can be categorised into iterative phases. Traditional, evolved and constructivist GT genres use different terminology to explain each coding phase ( Table 1 ).

Comparison of coding terminology in traditional, evolved and constructivist grounded theory.

Adapted from Birks and Mills. 6

Coding terminology in evolved GT refers to open (a procedure for developing categories of information), axial (an advanced procedure for interconnecting the categories) and selective coding (procedure for building a storyline from core codes that connects the categories), producing a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 6 , 12 , 32 Constructivist grounded theorists refer to initial, focused and theoretical coding. 9 Birks and Mills 6 use the terms initial, intermediate and advanced coding that link to low, medium and high-level conceptual analysis and development. The coding terms devised by Birks and Mills 6 were used for Figure 1 ; however, these can be altered to reflect the coding terminology used in the respective GT genres selected by the researcher.

Initial coding

Initial coding of data is the preliminary step in GT data analysis. 6 , 9 The purpose of initial coding is to start the process of fracturing the data to compare incident to incident and to look for similarities and differences in beginning patterns in the data. In initial coding, the researcher inductively generates as many codes as possible from early data. 16 Important words or groups of words are identified and labelled. In GT, codes identify social and psychological processes and actions as opposed to themes. Charmaz 16 emphasises keeping codes as similar to the data as possible and advocates embedding actions in the codes in an iterative coding process. Saldaña 33 agrees that codes that denote action, which he calls process codes, can be used interchangeably with gerunds (verbs ending in ing ). In vivo codes are often verbatim quotes from the participants’ words and are often used as the labels to capture the participant’s words as representative of a broader concept or process in the data. 6 Table 1 reflects variation in the terminology of codes used by grounded theorists.

Initial coding categorises and assigns meaning to the data, comparing incident-to-incident, labelling beginning patterns and beginning to look for comparisons between the codes. During initial coding, it is important to ask ‘what is this data a study of’. 18 What does the data assume, ‘suggest’ or ‘pronounce’ and ‘from whose point of view’ does this data come, whom does it represent or whose thoughts are they?. 16 What collectively might it represent? The process of documenting reactions, emotions and related actions enables researchers to explore, challenge and intensify their sensitivity to the data. 34 Early coding assists the researcher to identify the direction for further data gathering. After initial analysis, theoretical sampling is employed to direct collection of additional data that will inform the ‘developing theory’. 9 Initial coding advances into intermediate coding once categories begin to develop.

Theoretical sampling

The purpose of theoretical sampling is to allow the researcher to follow leads in the data by sampling new participants or material that provides relevant information. As depicted in Figure 1 , theoretical sampling is central to GT design, aids the evolving theory 5 , 7 , 16 and ensures the final developed theory is grounded in the data. 9 Theoretical sampling in GT is for the development of a theoretical category, as opposed to sampling for population representation. 10 Novice researchers need to acknowledge this difference if they are to achieve congruence within the methodology. Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sampling as ‘the process of identifying and pursuing clues that arise during analysis in a grounded theory study’ (p. 68). During this process, additional information is sought to saturate categories under development. The analysis identifies relationships, highlights gaps in the existing data set and may reveal insight into what is not yet known. The exemplars in Box 1 highlight how theoretical sampling led to the inclusion of further data.

Examples of theoretical sampling.

Thus, theoretical sampling is used to focus and generate data to feed the iterative process of continual comparative analysis of the data. 6

Intermediate coding

Intermediate coding, identifying a core category, theoretical data saturation, constant comparative analysis, theoretical sensitivity and memoing occur in the next phase of the GT process. 6 Intermediate coding builds on the initial coding phase. Where initial coding fractures the data, intermediate coding begins to transform basic data into more abstract concepts allowing the theory to emerge from the data. During this analytic stage, a process of reviewing categories and identifying which ones, if any, can be subsumed beneath other categories occurs and the properties or dimension of the developed categories are refined. Properties refer to the characteristics that are common to all the concepts in the category and dimensions are the variations of a property. 37

At this stage, a core category starts to become evident as developed categories form around a core concept; relationships are identified between categories and the analysis is refined. Birks and Mills 6 affirm that diagramming can aid analysis in the intermediate coding phase. Grounded theorists interact closely with the data during this phase, continually reassessing meaning to ascertain ‘what is really going on’ in the data. 30 Theoretical saturation ensues when new data analysis does not provide additional material to existing theoretical categories, and the categories are sufficiently explained. 6

Advanced coding

Birks and Mills 6 described advanced coding as the ‘techniques used to facilitate integration of the final grounded theory’ (p. 177). These authors promote storyline technique (described in the following section) and theoretical coding as strategies for advancing analysis and theoretical integration. Advanced coding is essential to produce a theory that is grounded in the data and has explanatory power. 6 During the advanced coding phase, concepts that reach the stage of categories will be abstract, representing stories of many, reduced into highly conceptual terms. The findings are presented as a set of interrelated concepts as opposed to presenting themes. 28 Explanatory statements detail the relationships between categories and the central core category. 28

Storyline is a tool that can be used for theoretical integration. Birks and Mills 6 define storyline as ‘a strategy for facilitating integration, construction, formulation, and presentation of research findings through the production of a coherent grounded theory’ (p. 180). Storyline technique is first proposed with limited attention in Basics of Qualitative Research by Strauss and Corbin 12 and further developed by Birks et al. 38 as a tool for theoretical integration. The storyline is the conceptualisation of the core category. 6 This procedure builds a story that connects the categories and produces a discursive set of theoretical propositions. 24 Birks and Mills 6 contend that storyline can be ‘used to produce a comprehensive rendering of your grounded theory’ (p. 118). Birks et al. 38 had earlier concluded, ‘storyline enhances the development, presentation and comprehension of the outcomes of grounded theory research’ (p. 405). Once the storyline is developed, the GT is finalised using theoretical codes that ‘provide a framework for enhancing the explanatory power of the storyline and its potential as theory’. 6 Thus, storyline is the explication of the theory.

Theoretical coding occurs as the final culminating stage towards achieving a GT. 39 , 40 The purpose of theoretical coding is to integrate the substantive theory. 41 Saldaña 40 states, ‘theoretical coding integrates and synthesises the categories derived from coding and analysis to now create a theory’ (p. 224). Initial coding fractures the data while theoretical codes ‘weave the fractured story back together again into an organized whole theory’. 18 Advanced coding that integrates extant theory adds further explanatory power to the findings. 6 The examples in Box 2 describe the use of storyline as a technique.

Writing the storyline.

Theoretical sensitivity

As presented in Figure 1 , theoretical sensitivity encompasses the entire research process. Glaser and Strauss 5 initially described the term theoretical sensitivity in The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Theoretical sensitivity is the ability to know when you identify a data segment that is important to your theory. While Strauss and Corbin 12 describe theoretical sensitivity as the insight into what is meaningful and of significance in the data for theory development, Birks and Mills 6 define theoretical sensitivity as ‘the ability to recognise and extract from the data elements that have relevance for the emerging theory’ (p. 181). Conducting GT research requires a balance between keeping an open mind and the ability to identify elements of theoretical significance during data generation and/or collection and data analysis. 6

Several analytic tools and techniques can be used to enhance theoretical sensitivity and increase the grounded theorist’s sensitivity to theoretical constructs in the data. 28 Birks and Mills 6 state, ‘as a grounded theorist becomes immersed in the data, their level of theoretical sensitivity to analytic possibilities will increase’ (p. 12). Developing sensitivity as a grounded theorist and the application of theoretical sensitivity throughout the research process allows the analytical focus to be directed towards theory development and ultimately result in an integrated and abstract GT. 6 The example in Box 3 highlights how analytic tools are employed to increase theoretical sensitivity.

Theoretical sensitivity.

The grounded theory

The meticulous application of essential GT methods refines the analysis resulting in the generation of an integrated, comprehensive GT that explains a process relating to a particular phenomenon. 6 The results of a GT study are communicated as a set of concepts, related to each other in an interrelated whole, and expressed in the production of a substantive theory. 5 , 7 , 16 A substantive theory is a theoretical interpretation or explanation of a studied phenomenon 6 , 17 Thus, the hallmark of grounded theory is the generation of theory ‘abstracted from, or grounded in, data generated and collected by the researcher’. 6 However, to ensure quality in research requires the application of rigour throughout the research process.

Quality and rigour

The quality of a grounded theory can be related to three distinct areas underpinned by (1) the researcher’s expertise, knowledge and research skills; (2) methodological congruence with the research question; and (3) procedural precision in the use of methods. 6 Methodological congruence is substantiated when the philosophical position of the researcher is congruent with the research question and the methodological approach selected. 6 Data collection or generation and analytical conceptualisation need to be rigorous throughout the research process to secure excellence in the final grounded theory. 44

Procedural precision requires careful attention to maintaining a detailed audit trail, data management strategies and demonstrable procedural logic recorded using memos. 6 Organisation and management of research data, memos and literature can be assisted using software programs such as NVivo. An audit trail of decision-making, changes in the direction of the research and the rationale for decisions made are essential to ensure rigour in the final grounded theory. 6

This article offers a framework to assist novice researchers visualise the iterative processes that underpin a GT study. The fundamental process and methods used to generate an integrated grounded theory have been described. Novice researchers can adapt the framework presented to inform and guide the design of a GT study. This framework provides a useful guide to visualise the interplay between the methods and processes inherent in conducting GT. Research conducted ethically and with meticulous attention to process will ensure quality research outcomes that have relevance at the practice level.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Grounded Theory

Definition:

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that aims to generate theories based on data that are grounded in the empirical reality of the research context. The method involves a systematic process of data collection, coding, categorization, and analysis to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

The ultimate goal is to develop a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, which is based on the data collected and analyzed rather than on preconceived notions or hypotheses. The resulting theory should be able to explain the phenomenon in a way that is consistent with the data and also accounts for variations and discrepancies in the data. Grounded Theory is widely used in sociology, psychology, management, and other social sciences to study a wide range of phenomena, such as organizational behavior, social interaction, and health care.

History of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory was first introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s as a response to the limitations of traditional positivist approaches to social research. The approach was initially developed to study dying patients and their families in hospitals, but it was soon applied to other areas of sociology and beyond.

Glaser and Strauss published their seminal book “The Discovery of Grounded Theory” in 1967, in which they presented their approach to developing theory from empirical data. They argued that existing social theories often did not account for the complexity and diversity of social phenomena, and that the development of theory should be grounded in empirical data.

Since then, Grounded Theory has become a widely used methodology in the social sciences, and has been applied to a wide range of topics, including healthcare, education, business, and psychology. The approach has also evolved over time, with variations such as constructivist grounded theory and feminist grounded theory being developed to address specific criticisms and limitations of the original approach.

Types of Grounded Theory

There are two main types of Grounded Theory: Classic Grounded Theory and Constructivist Grounded Theory.

Classic Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Glaser and Strauss, and emphasizes the discovery of a theory that is grounded in data. The focus is on generating a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, without being influenced by preconceived notions or existing theories. The process involves a continuous cycle of data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories and subcategories that are grounded in the data. The categories and subcategories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that explains the phenomenon.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Charmaz, and emphasizes the role of the researcher in the process of theory development. The focus is on understanding how individuals construct meaning and interpret their experiences, rather than on discovering an objective truth. The process involves a reflexive and iterative approach to data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories that are grounded in the data and the researcher’s interpretations of the data. The categories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that accounts for the multiple perspectives and interpretations of the phenomenon being studied.

Grounded Theory Conducting Guide

Here are some general guidelines for conducting a Grounded Theory study:

- Choose a research question: Start by selecting a research question that is open-ended and focuses on a specific social phenomenon or problem.

- Select participants and collect data: Identify a diverse group of participants who have experienced the phenomenon being studied. Use a variety of data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to collect rich and diverse data.

- Analyze the data: Begin the process of analyzing the data using constant comparison. This involves comparing the data to each other and to existing categories and codes, in order to identify patterns and relationships. Use open coding to identify concepts and categories, and then use axial coding to organize them into a theoretical framework.

- Generate categories and codes: Generate categories and codes that describe the phenomenon being studied. Make sure that they are grounded in the data and that they accurately reflect the experiences of the participants.

- Refine and develop the theory: Use theoretical sampling to identify new data sources that are relevant to the developing theory. Use memoing to reflect on insights and ideas that emerge during the analysis process. Continue to refine and develop the theory until it provides a comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon.

- Validate the theory: Finally, seek to validate the theory by testing it against new data and seeking feedback from peers and other researchers. This process helps to refine and improve the theory, and to ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Write up and disseminate the findings: Once the theory is fully developed and validated, write up the findings and disseminate them through academic publications and presentations. Make sure to acknowledge the contributions of the participants and to provide a detailed account of the research methods used.

Data Collection Methods

Grounded Theory Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Interviews : One of the most common data collection methods in Grounded Theory is the use of in-depth interviews. Interviews allow researchers to gather rich and detailed data about the experiences, perspectives, and attitudes of participants. Interviews can be conducted one-on-one or in a group setting.

- Observation : Observation is another data collection method used in Grounded Theory. Researchers may observe participants in their natural settings, such as in a workplace or community setting. This method can provide insights into the social interactions and behaviors of participants.

- Document analysis: Grounded Theory researchers also use document analysis as a data collection method. This involves analyzing existing documents such as reports, policies, or historical records that are relevant to the phenomenon being studied.

- Focus groups : Focus groups involve bringing together a group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. This method can provide insights into group dynamics and social interactions.

- Fieldwork : Fieldwork involves immersing oneself in the research setting and participating in the activities of the participants. This method can provide an in-depth understanding of the culture and social dynamics of the research setting.

- Multimedia data: Grounded Theory researchers may also use multimedia data such as photographs, videos, or audio recordings to capture the experiences and perspectives of participants.

Data Analysis Methods

Grounded Theory Data Analysis Methods are as follows:

- Open coding: Open coding is the process of identifying concepts and categories in the data. Researchers use open coding to assign codes to different pieces of data, and to identify similarities and differences between them.

- Axial coding: Axial coding is the process of organizing the codes into broader categories and subcategories. Researchers use axial coding to develop a theoretical framework that explains the phenomenon being studied.

- Constant comparison: Grounded Theory involves a process of constant comparison, in which data is compared to each other and to existing categories and codes in order to identify patterns and relationships.

- Theoretical sampling: Theoretical sampling involves selecting new data sources based on the emerging theory. Researchers use theoretical sampling to collect data that will help refine and validate the theory.

- Memoing : Memoing involves writing down reflections, insights, and ideas as the analysis progresses. This helps researchers to organize their thoughts and develop a deeper understanding of the data.

- Peer debriefing: Peer debriefing involves seeking feedback from peers and other researchers on the developing theory. This process helps to validate the theory and ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Member checking: Member checking involves sharing the emerging theory with the participants in the study and seeking their feedback. This process helps to ensure that the theory accurately reflects the experiences and perspectives of the participants.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple sources of data to validate the emerging theory. Researchers may use different data collection methods, different data sources, or different analysts to ensure that the theory is grounded in the data.

Applications of Grounded Theory

Here are some of the key applications of Grounded Theory:

- Social sciences : Grounded Theory is widely used in social science research, particularly in fields such as sociology, psychology, and anthropology. It can be used to explore a wide range of social phenomena, such as social interactions, power dynamics, and cultural practices.

- Healthcare : Grounded Theory can be used in healthcare research to explore patient experiences, healthcare practices, and healthcare systems. It can provide insights into the factors that influence healthcare outcomes, and can inform the development of interventions and policies.

- Education : Grounded Theory can be used in education research to explore teaching and learning processes, student experiences, and educational policies. It can provide insights into the factors that influence educational outcomes, and can inform the development of educational interventions and policies.

- Business : Grounded Theory can be used in business research to explore organizational processes, management practices, and consumer behavior. It can provide insights into the factors that influence business outcomes, and can inform the development of business strategies and policies.

- Technology : Grounded Theory can be used in technology research to explore user experiences, technology adoption, and technology design. It can provide insights into the factors that influence technology outcomes, and can inform the development of technology interventions and policies.

Examples of Grounded Theory

Examples of Grounded Theory in different case studies are as follows:

- Glaser and Strauss (1965): This study, which is considered one of the foundational works of Grounded Theory, explored the experiences of dying patients in a hospital. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of dying, and that was grounded in the data.

- Charmaz (1983): This study explored the experiences of chronic illness among young adults. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained how individuals with chronic illness managed their illness, and how their illness impacted their sense of self.

- Strauss and Corbin (1990): This study explored the experiences of individuals with chronic pain. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the different strategies that individuals used to manage their pain, and that was grounded in the data.

- Glaser and Strauss (1967): This study explored the experiences of individuals who were undergoing a process of becoming disabled. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of becoming disabled, and that was grounded in the data.

- Clarke (2005): This study explored the experiences of patients with cancer who were receiving chemotherapy. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the factors that influenced patient adherence to chemotherapy, and that was grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory Research Example

A Grounded Theory Research Example Would be:

Research question : What is the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process?

Data collection : The researcher conducted interviews with first-generation college students who had recently gone through the college admission process. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis: The researcher used a constant comparative method to analyze the data. This involved coding the data, comparing codes, and constantly revising the codes to identify common themes and patterns. The researcher also used memoing, which involved writing notes and reflections on the data and analysis.

Findings : Through the analysis of the data, the researcher identified several themes related to the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process, such as feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of the process, lacking knowledge about the process, and facing financial barriers.

Theory development: Based on the findings, the researcher developed a theory about the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process. The theory suggested that first-generation college students faced unique challenges in the college admission process due to their lack of knowledge and resources, and that these challenges could be addressed through targeted support programs and resources.

In summary, grounded theory research involves collecting data, analyzing it through constant comparison and memoing, and developing a theory grounded in the data. The resulting theory can help to explain the phenomenon being studied and guide future research and interventions.

Purpose of Grounded Theory

The purpose of Grounded Theory is to develop a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, process, or interaction. This theoretical framework is developed through a rigorous process of data collection, coding, and analysis, and is grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory aims to uncover the social processes and patterns that underlie social phenomena, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these processes and patterns. It is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings, and is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

The ultimate goal of Grounded Theory is to generate a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, and that can be used to explain and predict social phenomena. This theoretical framework can then be used to inform policy and practice, and to guide future research in the field.

When to use Grounded Theory

Following are some situations in which Grounded Theory may be particularly useful:

- Exploring new areas of research: Grounded Theory is particularly useful when exploring new areas of research that have not been well-studied. By collecting and analyzing data, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the social processes and patterns underlying the phenomenon of interest.

- Studying complex social phenomena: Grounded Theory is well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that involve multiple social processes and interactions. By using an iterative process of data collection and analysis, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the complexity of the social phenomenon.

- Generating hypotheses: Grounded Theory can be used to generate hypotheses about social processes and interactions that can be tested in future research. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for further research and hypothesis testing.

- Informing policy and practice : Grounded Theory can provide insights into the factors that influence social phenomena, and can inform policy and practice in a variety of fields. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for intervention and policy development.

Characteristics of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research method that is characterized by several key features, including:

- Emergence : Grounded Theory emphasizes the emergence of theoretical categories and concepts from the data, rather than preconceived theoretical ideas. This means that the researcher does not start with a preconceived theory or hypothesis, but instead allows the theory to emerge from the data.

- Iteration : Grounded Theory is an iterative process that involves constant comparison of data and analysis, with each round of data collection and analysis refining the theoretical framework.

- Inductive : Grounded Theory is an inductive method of analysis, which means that it derives meaning from the data. The researcher starts with the raw data and systematically codes and categorizes it to identify patterns and themes, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these patterns.

- Reflexive : Grounded Theory requires the researcher to be reflexive and self-aware throughout the research process. The researcher’s personal biases and assumptions must be acknowledged and addressed in the analysis process.

- Holistic : Grounded Theory takes a holistic approach to data analysis, looking at the entire data set rather than focusing on individual data points. This allows the researcher to identify patterns and themes that may not be apparent when looking at individual data points.

- Contextual : Grounded Theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the context in which social phenomena occur. This means that the researcher must consider the social, cultural, and historical factors that may influence the phenomenon of interest.

Advantages of Grounded Theory

Advantages of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Flexibility : Grounded Theory is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings. It is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

- Validity : Grounded Theory aims to develop a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, which enhances the validity and reliability of the research findings. The iterative process of data collection and analysis also helps to ensure that the research findings are reliable and robust.

- Originality : Grounded Theory can generate new and original insights into social phenomena, as it is not constrained by preconceived theoretical ideas or hypotheses. This allows researchers to explore new areas of research and generate new theoretical frameworks.

- Real-world relevance: Grounded Theory can inform policy and practice, as it provides insights into the factors that influence social phenomena. The theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be used to inform policy development and intervention strategies.

- Ethical : Grounded Theory is an ethical research method, as it allows participants to have a voice in the research process. Participants’ perspectives are central to the data collection and analysis process, which ensures that their views are taken into account.

- Replication : Grounded Theory is a replicable method of research, as the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be tested and validated in future research.

Limitations of Grounded Theory

Limitations of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Grounded Theory can be a time-consuming method, as the iterative process of data collection and analysis requires significant time and effort. This can make it difficult to conduct research in a timely and cost-effective manner.

- Subjectivity : Grounded Theory is a subjective method, as the researcher’s personal biases and assumptions can influence the data analysis process. This can lead to potential issues with reliability and validity of the research findings.

- Generalizability : Grounded Theory is a context-specific method, which means that the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. This can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Lack of structure : Grounded Theory is an exploratory method, which means that it lacks the structure of other research methods, such as surveys or experiments. This can make it difficult to compare findings across different studies.

- Data overload: Grounded Theory can generate a large amount of data, which can be overwhelming for researchers. This can make it difficult to manage and analyze the data effectively.

- Difficulty in publication: Grounded Theory can be challenging to publish in some academic journals, as some reviewers and editors may view it as less rigorous than other research methods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and...

ANOVA (Analysis of variance) – Formulas, Types...

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory

- First Online: 29 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Robert E. White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8045-164X 3 &

- Karyn Cooper 4

1572 Accesses

4 Citations

Grounded theory may perhaps be one of the most widely known methodologies used to conduct qualitative research in the social sciences and beyond. Introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), grounded theory suggests that procedures once thought to be unacceptable with regards to traditional qualitative research have become perfectly acceptable, if not desirable and required. The methodology also provides justification for regarding qualitative research as a legitimate and rigorous form of inquiry (DePoy & Gitlin, 2016).

GT is multivariate. It happens sequentially, subsequently, simultaneously, serendipitously, and scheduled. Barney Glaser ( 1998 )

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aldiabat, K., & Le Navenec, C.-L. (2011a). Phiosophical roots of classical grounded theory: Its foundations in symbolic interactionism. The Qualitative Report, 16 (4), 1063–1080.

Google Scholar

Aldiabat, K., & Le Navenec, C.-L. (2011b). Clarification of the blurred boundaries between grounded theory and ethnography: Differences and similarities. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (3) Retrieved May 15, 2019, from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537796.pdf

Allan, G. (2003). A critique of using grounded theory as a research method. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 2 (1), 1–10.

Bernard, H. R. (2000). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Sage.

Bernard, H. R., & Ryan, G. W. (2010). Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches . Sage.

Bhaskar, R. (1998). Philosophy and scientific realism. In M. Archer, R. Bhaskar, A. Collier, T. Lawson & A, Norrie (Eds.), Critical realism: Essential readings, (pp. 16-47). : Routledge.

Campbell, J. (2011, January 2). Grounded theory video 34. Introduction to methods of qualitative research . Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved November 1, 2011, from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fZYlXMStdlo

Capper, C. A. (1993). Educational administration in a pluralistic society: A multiparadigm approach. In C. Capper (Ed.), Educational administration in a pluralistic society (pp. 7–35). SUNY Press.

Charmaz, K. (1990). Discovering chronic illness: Using grounded theory. Social Science & Medicine, 30 (11), 1161–1172.

Article Google Scholar

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 509–535). Sage.

Charmaz, K. (2004). Grounded theory. In M. S. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, & T. Futing Liao (Eds.), The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods (pp. 440–444). Sage.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . Sage.

DePoy, E., & Gitlin, L. N. (2016). Introduction to research (5th ed.). Elsevier.

Dey, I. (1999). Grounding grounded theory: Guidelines for qualitative inquiry . Emerald Group.

Fletcher-Watson, B. (2013). Toward a grounded dramaturgy: Using grounded theory to interrogate performance practices in theatre for early years. Youth Theatre Journal, 27 (2), 130–138.

Gibbs, G. (2010a, June 11). Core elements part 1. Grounded theory . University of Huddersfield. Retrieved November 4, 2011, from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4SZDTp3_New

Gibbs, G. (2010b, June 19). Core elements part 2. Grounded theory . University of Huddersfield. Retrieved May 22, 2019, from.: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dbntk_xeLHA

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory . The Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing . The Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing Grounded theory: Issues & Discussion . The Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2001). The grounded theory perspective: Conceptualization contrasted with description . The Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2007). All is data. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 2 (6) Retrieved May 21, 2019, from: http://groundedtheoryreview.com/2007/03/30/1194/

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1965/2005). Awareness of dying. Routledge.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Routledge.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). A response to the commentaries. Comparative Social Research, 16 , 121–132.

Haig, B. D. (2010). Abductive research methods. In P. Peterson, R. Tierney, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (3rd ed., pp. 77–82). Elsevier.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hernandez Blanco, H. J. & Alas-as, T. C. (n.d.). Grounded research methods . Retrieved May 21, 2019, from.: https://www.scribd.com/presentation/362248809/Grounded-theory-ppt

Holton, G. (2004). Robert K. Merton. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 148 (4), 505–517.

Holton, J. A. (2010). The coding process and its challenges. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 1 (9) Retrieved May 21, 2019, from: http://groundedtheoryreview.com/2010/04/02/the-coding-process-and-its-challenges/

James, P. (2006). Globalism, nationalism, tribalism: Bringing theory back in . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Kelle, U. (2005). “Emergence” vs. “forcing” of empirical data? A crucial problem of “grounded theory” reconsidered. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6 (2), Art 27. Retrieved, May 21, 2019, from: https://cdn.uclouvain.be/public/Exports%20reddot/spri/documents/FQS_2005_A_Crucial_Problem_of_Grounded_Theory_Reconsidered.pdf

Kempster, S., & Parry, K. W. (2011). Grounded theory and leadership research: A critical realist perspective. The Leadership Quarterly., 22 ( 1 ), 106–120.

Martin, P. Y., & Turner, B. A. (1986). Grounded theory and organizational research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 22 (2), 141–157.

Merton, R. K. (1936). The unanticipated consequences of purposive social action. American Sociological Review, 1 (6), 894–904.

Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure . The Free Press.

Merton, R. K., & Barber, E. (2004). The travels and adventures of serendipity: A study in sociological semantics and the sociology of science . Princeton University Press.

Mesly, O. (2015). Creating models in psychological research . Springer.

Mjøset, L. (2005). Can grounded theory solve the problems of its critics? Sosiologisk Tidsskrift, 13 , 379–408. Retrieved May 23, 2019, from: https://ieri.org.za/sites/default/files/Text_-_Building_Social_Science_on_case_studies_lessons_for_BRICS.pdf

Morse, J. M., & Niehaus, L. (2009). Mixed method design: Principles and procedures . Left Coast Press.

Parker, L. D., & Roffey, B. H. (1997). Methodological themes: Back to the drawing board: Revisiting grounded theory and the everyday accountant’s and manager’s reality. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 10 (2), 212–247.

Peirce, C. S. (2011). Philosophical writings of Peirce . Dover.

Pidgeon, N., & Henwood, K. (2009). Grounded theory . In M. Hardy & A. Bryman (Eds.), Handbook of data analysis (pp. 625–648). Sage.

Popper, K. R. (1979). Objective knowledge . Oxford University Press.

Potter, J. A. (1998). Qualitative and discourse analysis. In A. S. Bellack & M. Hersen (Eds.), Comprehensive clinical psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 117–144). Pergamon.

Ralph, N., Birks, M., & Chapman, Y. (2014). Contextual positioning: Using documents as extant data in grounded theory research. Sage Open, 4 (3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014552425

Ralph, N., Birks, M., & Chapman, Y. (2015). The methodological dynamism of grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915611576

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice . Routledge.

Scott, H. (2009). What is grounded theory? Grounded theory online. Retrieved May 20, 2019, from: http://www.groundedtheoryonline.com/what-is-grounded-theory/

Stanley, L., & Wise, S. (2002). Breaking out again: Feminist ontology and epistemology . Routledge.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists . Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques (2nd ed.). Sage.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (1st ed., pp. 273–284). Sage.

Thomas, G., & James, D. (2006). Reinventing grounded theory: Some questions about theory, ground and discovery. British Education Research Journal, 32 (6), 767–795.

Tolhurst, E. (2012). Grounded theory method: Sociology’s quest for exclusive items of inquiry. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13 (3), Art. 26. Retrieved May 23, 2019, from: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1860/3432

Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology . Open University Press.

Willis, J. W. (2007). Foundations of qualitative research: Interpretive and critical approaches . Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada

Robert E. White

OISE, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Karyn Cooper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert E. White .

Negotiating emotional order: a grounded theory of breast cancer survivors

Jennifer A. Klimek Yingling

Klimek Yingling, J. A. (2018). Negotiating emotional order: A grounded theory of breast cancer survivors. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal 17 (1), 12-27.

In this article, classic grounded theory captures the processes of 12 women who had completed initial treatment for breast cancer. The qualitative data analysis reveals the basic social process of negotiating emotional order that describe how breast cancer survivors perceive their illness and decide to take action. From the data, five stages of the process of negotiating emotional order emerge: 1) Losing Life Order, 2) Assisted Life Order, 3) Transforming 4) Accepting, and 5) Creating Emotional Order. This study may help healthcare providers who care for breast cancer survivors understand the depth of perpetual emotional impact that breast cancer survivors endure. This study will potentially serve as a path for future research and aid in the understanding of the psychological impact that breast cancer has upon survivors.

Keywords : breast cancer, survivor, chemotherapy, emotional order

What Sparked This Research

I cared for a patient who I had gotten to know as her child often visited the emergency department due to hemophilia. She was a pleasure to work with, strong, level headed, and upbeat. On this particular day she was the patient. Her complaint was simple: a cough and she clearly wasn’t herself emotionally. I was surprised to discover, when I took her past medical history, that she was a breast cancer survivor. After I discussed her chest x-ray results I sensed she was still upset and filled with uncertainty. Then the lightbulb went on. I asked her directly if she was concerned if the cancer was recurring. She said yes and her tears flowed. I do believe if I had not dug a little deeper into her emotional state she would have left the emergency department with much of the same emotional duress that she initially had. This interaction sparked my research as it was clear that breast cancer survivors endure a process after treatment ends. For these survivors the treatment is over but the emotional aspect of breast cancer is not. It also became evident to me that health care providers need to know more about this process on order to be able to treat patients holistically.

Negotiating Emotional Order: A Grounded Theory of Breast Cancer Survivors

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer found in women worldwide (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2016; Ferlay et al., 2104). In the United States, it is estimated that 3.5 million women have been diagnosed with breast cancer; 245,000 will be newly diagnosed; and, approximately 40,000 women will succumb to breast cancer annually (ACS, 2016; Breastcancer.org, 2016). Early detection and improved treatment is credited to the rising population of women who are breast cancer survivors (Howlader et al., 2015; McCloskey, Lee, & Steinburg, 2011). Concerns about the psychosocial ramifications of chronic illness have a long history. The Institute of Medicine (2009), American Cancer Society (2015), and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (2015) resonate concern about psychosocial hindrances regarding cancer patients, citing them as a critical area needing improvement within the nation’s health care system.

The literature suggests breast cancer survivors endure psychological stressors after the completion of treatment including the following: loneliness (Marroquin, Czamanski-Cohen, Weihs, & Stanton, 2016; Rosedale, 2009), anxiety and depression (Walker, Szanton, & Wenzel, 2015), uncertainty (Dawson, Madsen, & Dains, 2016; Mishel et al., 2005), and fear of recurrence (McGinty, Small, Laronga, & Jacobsen, 2016). The phenomenon of breast cancer survivorship has been identified with qualitative methods, yet is lacking explanatory theory (Allen, Savadatti & Levy, 2009; Pelusi, 1997). Qualitative analysis uses inductive rather than deductive investigation of a clinical phenomenon for capturing themes and patterns within subjective perceptions to generate an interpretive account to inform clinical understanding. Inductive methods are used by the researchers to discover and generate theory (Artinian, Giske, & Cone, 2009; Glaser, 2008). Therefore, grounded theory was chosen to study the process of survivorship in women who have completed treatment for breast cancer.

A Glaserian grounded theory design was chosen to explore the process of transition survivorship in women who have completed treatment for breast cancer. Grounded theory allows the researcher to explore a phenomenon and build theory from concepts going through processes and transitions (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Glaser, 2008). The ACS defines cancer survivor as “anyone with a history of cancer, from the time of diagnosis through the remainder of their life” (ACS, 2016, p. 3). This definition was used for inclusion criteria for this project. Prior to commencement of the research, approval from the university’s institutional review board was secured. A purposive sample was sought and participants were self-identified breast cancer survivors in a suburban community in Northeast United States. A presentation was made at a local breast cancer survivorship group. Flyers were posted in community centers, libraries, and public places including areas that reach numerous individuals. Based on these recruitment efforts, 12 women were interviewed during a four-month period.

Data Collection

All participants received written and verbal information about the study and gave informed consent. Data were collected by completing the following: a demographic data form, approximately one-hour individual in-depth interviews, observational notes, and field notes. All of the data was handled in a confidential manner. Each interview session lasted approximately one hour in length. Broad open-ended questions were used to stimulate discussion of thoughts and feelings about extended survivorship. Focused questions and prompts were used to elicit more specific information from participants about their actions to attain and maintain psychosocial health after the completion of breast cancer treatment. The focus questions also elicited information about processes used to modify and maneuver through adversities after completion of treatment. Each participant was asked to describe situations when she knew something had changed in her health and psychosocial status after the completion of treatment for breast cancer. Participants were asked to answer the questions until they felt they had no information to add to the topic.

Data Analysis

Data analysis took a Glaserian approach in which data collection, analysis, and memoing were ongoing and concurrent throughout the research. Each interview was digitally taped and transcribed. Atlas.ti software was used as a depository to code, store, and memo during analysis. Data was coded line by line to fracture the data into nouns formed from a verb or gerund. The interviews were re-coded on three different occasions. After the initial interview was coded, the second interview was coded in a similar fashion and the data were examined for common constructs that were clustered. Subsequent interviews were open-coded and compared with ideas and relationships described in the researcher’s memos. As the categories unfolded, some categories were re-coded or combined with other categories. At the conclusion of the last interview, all codes were sorted to certify fit. Once a core variable or category was identified, coding became selective. The researcher continued the interviews and coding until saturation of the core variable was achieved. On saturation, theoretical coding was used to intersect categories within the data. Exploration of the literature for substantive codes that were significant was conducted each day. Extensive memo taking was used via manual notes and also as freehand drawn visuals created by the researcher to capture the researcher’s mind set.

Trustworthiness

For the purpose of this paper, a conglomerate of trustworthiness criteria grounded from the recommendations of Glaser (1978, 1998, 2001) was employed. The researcher who conducted this study had scant exposure to extended breast cancer survivors in her personal and professional realm. Techniques to establish credibility included prolonged engagement and peer debriefing. Theoretical sampling and constant comparison took place when data, analytic categories, interpretations, and conclusions were discussed and tested with study participants throughout the interview process. Prolonged engagement developed rapport and participant trust. To address transferability, the following groups of data were included in an audit trail: 1) raw data, 2) data reduction and analysis notes, data reconstruction and synthesis products, 3) process notes, 4) materials related to intentions and dispositions, and 5) preliminary development information. The researcher kept a reflexive journal to record methodological decisions and the rationale for the decisions, the planning and management of the study, and reflection upon the researcher’s own principles, feelings, and interests. Lastly, external audits were conducted by several researchers not involved with the research process on several occasions.

The Theory of Negotiating Emotional Order

The main concern of the women is the struggle for emotional order. The meaning inherent in the basic social process of Negotiating Emotional Order is that women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer strive for emotional order by negotiating control of the negative feeling of threats to their mortality and to live their daily lives. The process described in the theory of Negotiating Emotional Order changes as the situation of the breast cancer survivors changes. As time passes, the women move from discovering an abnormality to a time after treatment ends. This process is dynamic and perpetual in nature because the threat of cancer recurrence remains until the end of the breast cancer survivor’s life. For some women, negotiating emotional order is achieved even when the cancer recurs or metastasizes.

The participants’ actions and decisions illuminate the perpetual struggle to negotiate emotional order. For some, order is compartmentalizing negative thoughts and emotions that they could not control. For others, they accept the fact that they cannot control cancer but project order onto other aspects of their lives. The struggle for emotional order is present from the time the survivor found the abnormality into long-term survivorship and at times is cyclic. Five stages of the process of negotiating emotional order emerges from the data: 1) Losing Life Order, 2) Assisted Life Order, 3) Transforming, 4) Accepting, and 5) Creating Emotional Order.

Losing Life Order

During this time period, the realization of the threat of breast cancer disrupts emotional order with intense fear and uncertainty of the future. The breast cancer survivor often makes decisions and acts on her instincts to placate the immediacy that she feels prior to starting treatment, often seeks information from the Internet, popular literature, media and from others who have experienced breast cancer. Unfortunately, their need for immediacy is often not met by the health care community, so they take matters into their own hands and act.

Many of the participants voice that this time period is difficult, as they have multifaceted family roles as wives, mothers, and children of parents of their own causing additional emotional turmoil. The participants continue or attempt to continue with their family roles by working, caring for children, and maintaining their households. The breast cancer survivors voice that they don’t have time to let cancer get in the way emotionally as they are too busy with family and work responsibilities. The participants speak of emotional duress when they see their families react to their illness and chose to protect their families by concealing their emotions. One participant talked about why she concealed her emotions: “The emotional impact it had on my family was horrible . . . I felt like I had to be strong for them . . . I would not show any emotions about being sick.”

Losing order encompasses two properties of disorder: losing emotional order and losing physical order. Upon discovering an abnormality, and then confirming breast cancer, the breast cancer survivors report loss of control of their bodies, which causes emotional duress. This stage marked the survivors’ first sense that cancer cannot be controlled. Loss of emotional order is represented by feelings of sadness, anger, immediacy, loneliness, fear, and uncertainty. This stage is hallmarked by emotional chaos and decision making. Approaches the women use in this stage are: taking matters into own hands and concealing to maintain family order.

Assisted Life Order

Surprisingly, although treatment is a physically draining endeavor, the breast cancer survivors voice that it is a time of respite when they focus on physical well-being rather than the emotional disruption that is occurring. During this phase, the women are often consumed with treatments of surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation. The participants state they feel proactive and protected while under the frequent care of health care providers. This participant’s narrative exemplifies the feeling of being assisted emotionally and physically by health care providers: “While you’re getting chemotherapy, you think you’re doing something to kill off any additional cancer that the surgery didn’t get. You have certain protection.”

The breast cancer survivors verbalize feeling lonely, despite having much social and family support, and purposely seek out other women who endured breast cancer for emotional support. Breast cancer survivors seek emotional support from formal and informal support persons. The participants also discuss a phenomenon where other breast cancer survivors would approach them after hearing about their diagnosis and come to their assistance to provide support. The importance of this camaraderie is evident in this narrative: “I didn’t know people that have been through this…people came out of the woodwork. People that I had known that I didn’t know that had cancer who shared their stories with me.” Some of the breast cancer survivors express the need to have a connection with someone who has experienced breast cancer. Some women seek formal support groups for this need and continue to use them after treatment is completed.

The second stage of negotiating emotional order is assisted life order that occurs when the breast cancer survivor enters treatment and focuses all of her energy into physical well-being. At the same time, survivors entrust their life order into the hands of health care providers and rely on social support to carry them through the time that they are in treatment. During this time, the breast cancer survivor keeps physically and emotionally occupied with the routine of appointments and treatment. During this time, the women feel treatment is a sanctuary and they express that during this time they feel lonely in their current experience. During the second period, they engage with others with formal training or personal experience with breast cancer to establish emotional order.

Transforming