Immigration and Multiculturalism in the United Kingdom

Immigration and multiculturalism in the United Kingdom

A multicultural society.

According to migration statistics published by the House of Commons Library in 2020, 6.2 million people living in the UK have the nationality of a different country, while 9.5 million are British citizens who were born abroad. In 2019, 677,000 people migrated to the UK, while 407,000 emigrated from the UK. Every year since 1998 the number of people moving into the UK has been larger than the number of people leaving by at least 100,000. In recent years there has been much debate about whether the UK is able to sustain this much immigration, and concern about what consequences immigration will have for the country.

How the UK became multicultural

Some would argue that multiculturalism exists in the very framework of the United Kingdom, as it is made up of four countries: Northern Ireland, Wales, Scotland and England, each with its own languages, cultures, and traditions. Another view is that the history of multiculturalism in the UK is closely linked to its past as a colonial power. The British Empire spanned the world, and imported not only raw materials, art, and new types of food and drink from the colonies; there were also people who came and settled, looking for greater opportunities in Britain. However, immigration to the UK on a large scale only started after World War II, in part related to the collapse of the British Empire. When colonies gained independence and came under new rule many saw a need to leave, and they sought a home in the UK. Post-war Britain needed manpower and welcomed immigrants from its former colonies, inspiring many to make their home there. Since 1960 the number of immigrants to the UK has typically been larger than the number of people emigrating.

Immigration as a source of conflict

All immigration has the potential to cause conflict. People who already live in an area may see newcomers as a threat to their way of life and worry that they will lose their livelihoods or that their culture will not be respected. When times are good most people will have a relaxed attitude to immigration, especially if there is a surplus of jobs and opportunities. In times of financial hardship or uncertainty people are more likely to take an aggressive stance against immigration.

Immigration as a factor in Brexit

Immigration was an important part of the decision for people who voted to leave the European Union in the 2016 Brexit referendum. Research done by the British Social Attitudes Survey showed that for those who voted to leave 73% were worried about immigration. In the years leading up to the referendum many wanted immigration reduced on economic, social, and cultural grounds. That the EU allowed large groups of immigrants to come and settle increased scepticism of the EU in the UK.

Shared values?

When many different cultures live side by side there may be culture clashes and disagreements about how to live. In the UK British culture is the majority culture, and there is an expectation that people who move to the UK accept certain core values of British society. These are values such as:

- Universal human rights – including rights for women and people of other faiths.

- Equality of all before the law.

- Democracy and the right of people to elect their own government.

Groups in society may reject some or all of these core values, causing conflict with the majority culture. After the 11 September attacks in the USA in 2001, the UK stood by the United States in the War on Terror. In the following years the UK saw several examples of domestic terrorism perpetrated by Islamists who had been born and raised in the country. The deadliest attack happened on 7 July 2005, when several bombs were detonated on buses and trains in London, killing 52 people. Terror attacks like this caused concern about the consequences of immigration and lack of integration.

In 2011, the then Prime Minister David Cameron spoke in favour of no longer tolerating that communities that live in the UK behaving in a manner that is not compatible with British core values. Cameron felt the UK had failed to provide:

"a vision of society to which they feel they want to belong […] a clear sense of shared national identity that is open to everyone […] Frankly, we need a lot less of the passive tolerance of recent years and a much more active, muscular liberalism. A passively tolerant society says to its citizens, as long as you obey the law we will just leave you alone. It stands neutral between different values. But I believe a genuinely liberal country does much more; it believes in certain values and actively promotes them. Freedom of speech, freedom of worship, democracy, the rule of law, equal rights regardless of race, sex or sexuality. It says to its citizens, this is what defines us as a society: to belong here is to believe in these things.”.

The road ahead

The decision to leave the European Union in 2016 was welcomed by immigration sceptics who believe that this will enable the UK to fully control its own borders. No longer bound by the 1992 Maastricht Treaty the UK will not have to welcome EU citizens to study or work in the country. The UK will also not have to obey any shared decisions the EU makes about immigration. However, this control comes at a price: there is concern that there will be a lack of doctors, nurses, and other essential personnel after Brexit is completed. It is also difficult for the UK to achieve complete control of their borders due to pre-existing agreements made about the border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. An open border between these two countries is regarded by many as essential to preserving peace in the area.

It is difficult to see what lies ahead for Britain, but what does seem clear is that immigration will continue to be a central political issue.

Bulman, M., 2017, Brexit: People voted to leave EU because they feared immigration, major survey finds, The Independent, retrieved from: Website for the newspaper the Independent.

Cameron, D., 2011, PM's speech at Munich Security Conference , retrieved from: UK government website.

Goodwin, M., 2017, Why immigration was key to Brexit vote, The Irish Times, retrieved from: The article on the website for the newspaper the Irish Times .

House of Commons Library, 2020, Migration statistics , retrieved from: Website for the House of Commons Library.

Quiz: Multiculturalism and Immigration in the UK

Relatert innhold.

Find out more about immigration to the UK.

Read excerpts from two speeches about multiculturalism in the UK.

Regler for bruk

Læringsressurser.

Immigration and Multiculturalism

The Migration Observatory informs debates on international migration and public policy. Learn more about us

- Publications

- Press & Commentary

Home / publications / briefings /

EU Migration to and from the UK

20 Nov 2023

How many EU migrants are there in the UK? How has the migration of EU citizens changed since Brexit? This briefing provides key statistics on EU migrants and migration in the UK.

- Net migration of EU citizens has been negative since the pandemic and under the post-Brexit immigration system, with immigration falling by almost 70% compared to its 2016 peak. More…

- In 2021, there were approximately 4 million EU-born residents in the UK, making up 6% of the population and 37% of all those born abroad. More…

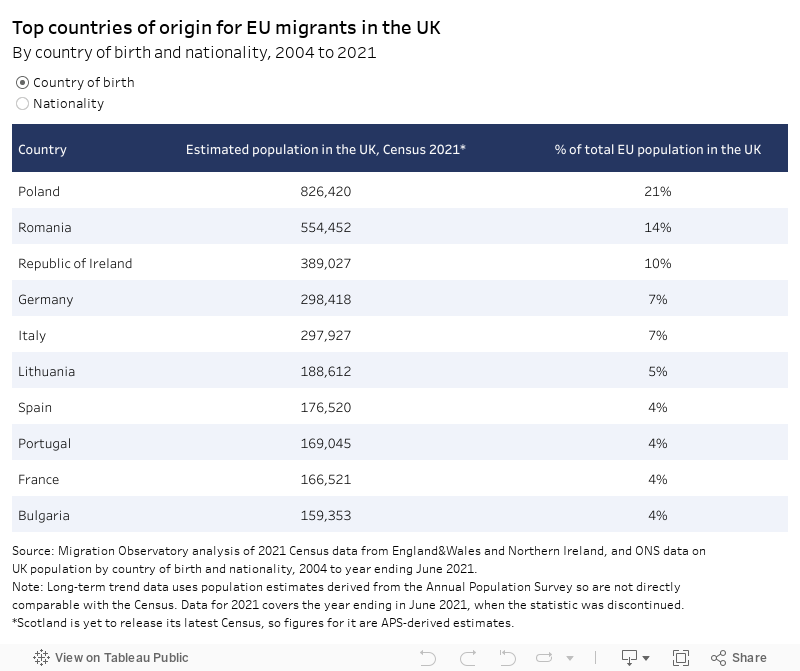

- The top origin country for EU-born residents is Poland (21%), followed by Romania (14%), the Republic of Ireland (10%), Germany (7%), and Italy (7%). More…

- EU Migrants in the UK are particularly concentrated in London, although to a lesser extent than those from outside the EU. More…

- EU nationals make up around 8% of employments in the UK, although their number has declined since 2019. More…

- An estimated 6.1 million individuals had applied to the EU Settlement Scheme by the end of June 2023, but not all of them are resident in the UK. More…

- As of June 2023, over 2.1 million people held pre-settled status and would need to reapply to EUSS to remain in the UK permanently. More…

- Since the post-Brexit immigration system was introduced in 2021, only 5% of all visas were granted to EU nationals. More…

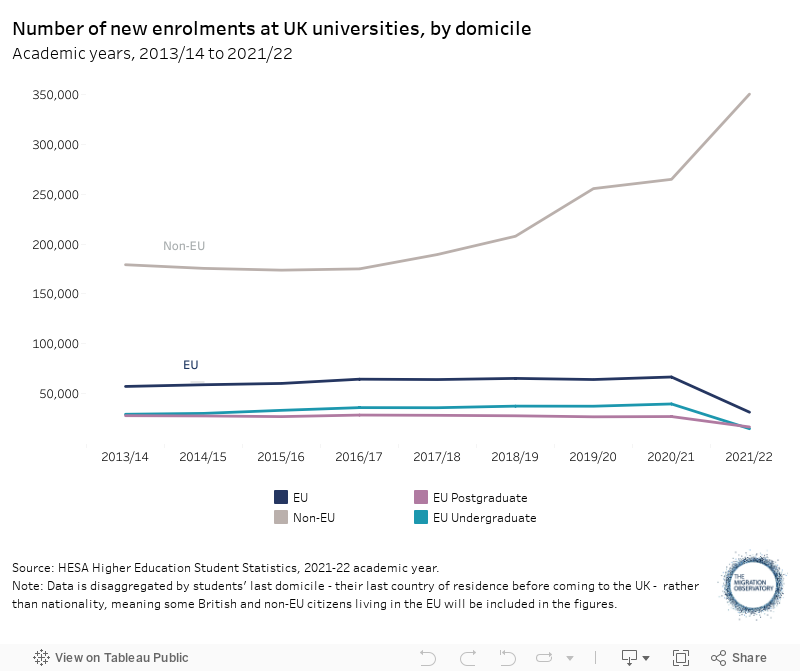

- New enrolments of EU students fell by 53% after post-Brexit rules took effect. More…

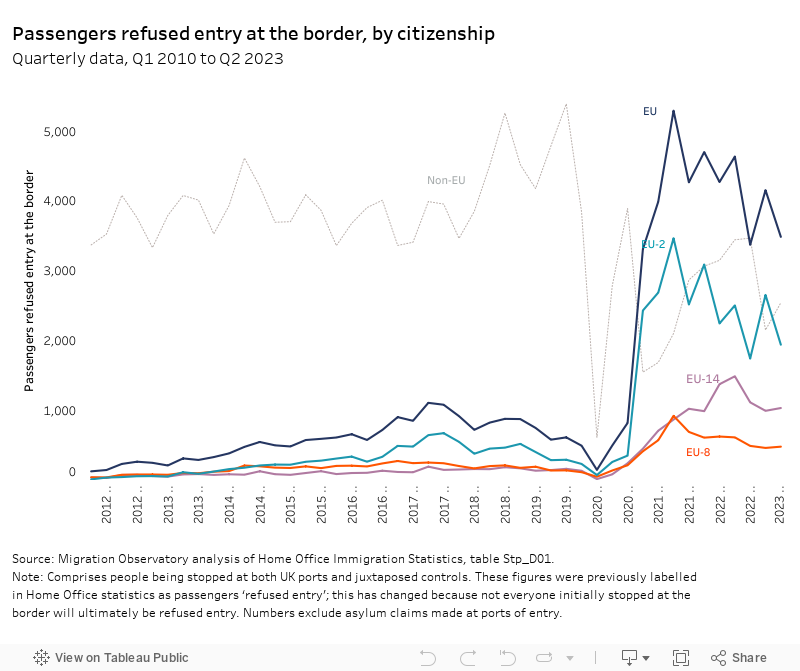

- EU citizens now make up a majority (53%) of those refused entry at the UK border. More…

The EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS)

The new immigration rules do not apply to EU citizens and their family members who were already living in the UK before free movement ended on 31 December 2020 (or eligible family members of EU citizens who can join them at any point after this date). These people instead had to apply to the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) and secure pre-settled or settled status (Irish citizens may apply to the EUSS but are not required to).

Settled status is a form of permanent residence in the UK, and is prerequisite for becoming a UK citizen. Pre-settled status is designed for people who have been living in the UK for less than 5 years, while settled status for those living in the UK for 5 years or more. A person with pre-settled status can apply again to EUSS to receive settled status once they have accrued the necessary 5 years’ residence. Under the initial EUSS policy, settled status was permanent but pre-settled status was designed to expire after 5 years. This meant that EU citizens who did not realise they had to reapply would have of losing their status entirely. Following a court decision in 2022, pre-settled status will no longer expire, although it may still be necessary for people to re-apply to the EUSS to demonstrate that they have settled status. Some (but not all) people with pre-settled status face restrictions on their access to certain benefits, such as Universal Credit.

Those living in the UK by 31 December 2020 were expected to apply to the EUSS by the deadline of 30 June 2021, although late applications are permitted where evidence is shown of reasonable grounds for missing the deadline. For more information about the EUSS, see the Migration Observatory report, Unsettled Status – 2020: Which EU Citizens are at Risk of Failing to Secure their Rights after Brexit?

The post-Brexit immigration system

Newly arriving EU citizens and their family members who are not eligible for the EUSS or entering the UK as visitors must obtain a visa in one of three main categories: work, family, or study. Under the rules for skilled workers, the main long-term work visa option for newly hired employees requires applicants to have a job offer for a role that is classified as a middle-skilled or high-skilled occupation. An overview of work-related migration policies and data are available in the Migration Observatory briefing, Work visas and migrant workers in the UK .

Under the new immigration rules, EU citizens joining family members settled in the UK must meet a £18,600 income threshold . The same requirement does not apply if the person they are joining has status under the EU Settlement Scheme, provided the relationship existed at the end of the transition period and continues to exist at the time of application, or relates to a child born after the end of the transition period.

Under free movement, EU students paid the same tuition fees as ‘Home’ students and were entitled to the same subsidised tuition fee loans. However, following the end of free movement, the academic year 2020/21 was the last year that EU citizens enjoyed these benefits. From 1 August 2021, new EU students must apply for a student visa and have generally been subject to higher international student tuition fees.

Citizens of countries that are in the EEA but not the EU (namely Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein), as well as Switzerland, face effectively the same immigration rules as EU citizens (with some small differences for Swiss citizens). We use the term ‘EU citizens’ throughout the briefing for ease of understanding and because some data sources refer specifically to EU citizens. Note, however, that although Ireland is an EU country and included in some EU data, it is part of the Common Travel Area and hence subject to free movement rules, unlike other EU countries.

In the meantime, we use a variety of sources to offer the best available overview of EU migrants in the UK. Note that different sources of data on migration often paint a slightly different picture, and there is often some uncertainty about exactly why they differ.

Estimates of migration flows to and from the UK come from the ONS’s new, experimental data on long-term international migration. Making use of administrative records, the new methods have the potential to improve migration statistics but are not yet labelled National Statistics, and still have important limitations. Slightly different methodologies are currently employed for measuring EU and non-EU migration.

The data on EU migration flows comes from the Registration and Population Interaction Database (RAPID). RAPID is based on administrative data on benefits and earnings datasets for anyone with a National Insurance number (NINo). It uses the UN definition of a long-term international migrant: a person who changes their country of usual residence for at least a year. The RAPID figures identify the nationality of the person at the time they registered for a NINo and thus include EU citizens who have subsequently naturalised as British citizens. They will exclude any EU citizens who did not register for a NINo until after naturalizing – although naturalisation rates have historically been low for EU citizens and remain relatively low despite recent increases ( Home Office, Section 4.2 ). While previous RAPID estimates offered a breakdown of flows by nationality groups, such data were discontinued in 2020. Where equivalent RAPID data are not available, we use estimates based on the International Passenger Survey (IPS). Readers should note that these figures are thought to underestimate EU immigration, however.

For non-EU citizens, recent ONS estimates rely on border data known as “exit checks” (although they also include entry data). Such data currently only meaningfully cover non-EU citizens, although this will change over time as more EU citizens moving to and from the UK are incorporated into the visa system (rather than, for example, the EU Settlement Scheme). More details can be found in the Migration Observatory briefing, Net migration to the UK .

For estimates of the UK’s resident EU population , this briefing primarily uses 2021 Census data from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. These figures are significantly more accurate than survey-based estimates from between censuses, such as those from the Annual Population Survey (APS). The latter are known to underestimate the migrant population, and their quality has declined over time, particularly since the pandemic. Except for Scotland, their use in this briefing is limited. However, Scotland has not yet released the results of its latest Census, meaning all Scottish data are derived from the APS. To produce our main estimates of the migrant population in 2021, we combine Census data from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland with estimates from the APS in Scotland for the year ending June 2021 (see Appendix).

Our labour market analysis of EU migrants is based on payroll employment estimates produced by the HMRC using administrative tax data. They are built by combining information from the pay-as-you-go (PAYE) real-time information (RTI) database and the Migrant Worker Scan. While they only cover workers on a payroll, and hence exclude the self-employed, such estimates are considerably more accurate in describing post-Covid dynamics on the labour market.

In this briefing, data on international students in UK higher education come from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). HESA categorises students by ‘domicile’: a person’s place of permanent residence before they start their course. This means that some non-UK nationals are UK-domiciled students. Data are sometimes restricted to “newly enrolled” students, to indicate annual inflows. In 2021, HESA changed its data to make it more comprehensive. This means that the statistics for 2021 are not strictly comparable with those for previous years.

This briefing follows the ONS classification that distinguishes between 4 different groups of EU countries based on the year they joined the EU: EU-14, EU-8, EU-2 and EU Other. The countries comprising these groups are available here .

The term ‘migrant’ is used differently in different contexts. In this briefing, we use ‘migrant’ to refer to people who were EU citizens when they moved to the UK. Some data sources provide country of birth, and some provide nationality. Each definition has limitations. Using country of birth has the drawback of including British citizens born abroad, such as the children of parents in the armed forces based overseas. However, defining migrants as the foreign-born has the benefit of including people who have come to the UK and naturalised – something that the nationality-based definition does not take into account. For further discussion of this terminology, see the Migration Observatory briefing, Who Counts as a Migrant: Definitions and their Consequences .

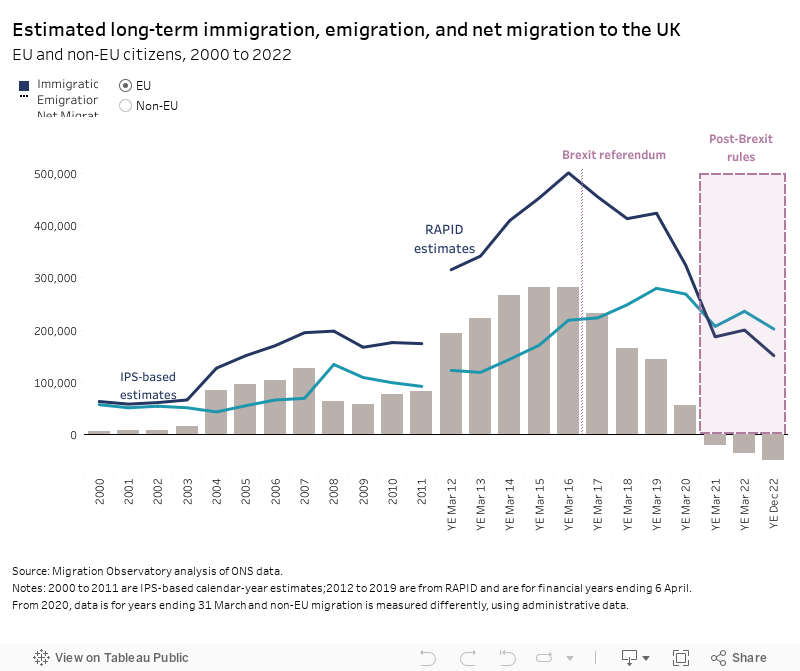

Net migration of EU citizens has been negative since the pandemic and under the post-Brexit immigration system, with immigration falling by almost 70% compared to its 2016 peak.

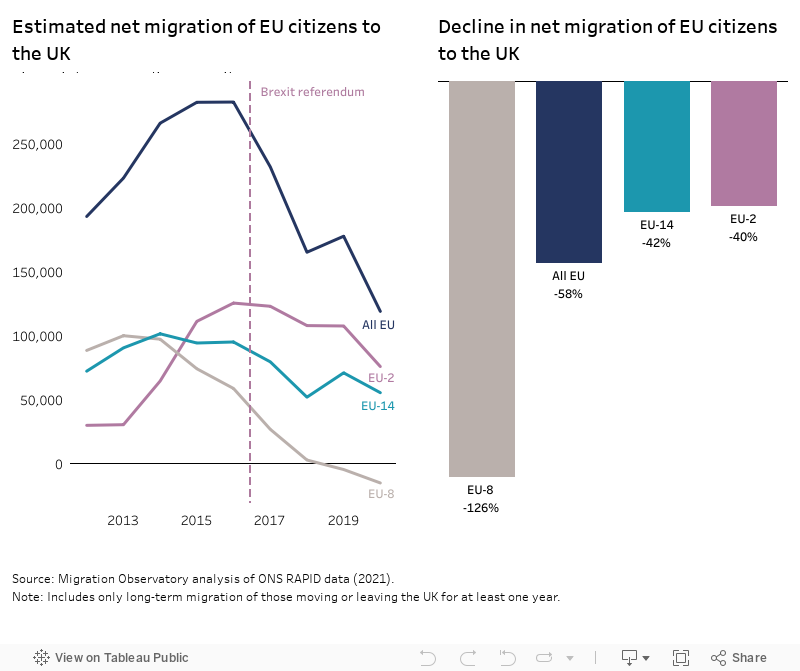

In the year ending December 2022, the long-term net migration of EU citizens to the UK was negative, at -51,000, according to Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates published in May 2023. Net migration from the EU turned negative in 2020, after the beginning of the pandemic, and continued falling in 2021 and 2022 (Figure 1). This marks a significant change compared to the previous two decades of positive EU net migration. In this time, there were two major peaks in migration from the EU. The first occurred shortly after the 2004 enlargement of the EU and ended following the financial crisis in 2008. The second came in 2013-15, mostly driven by an increase in immigration from the EU-2 countries (Romania and Bulgaria) after restrictions on their right to work in Britain were lifted. In the year ending March 2016, EU net migration peaked at over 280,000, with more than 500,000 EU nationals moving to the UK.

Most of the decline in net migration has occurred because of a sharp drop in immigration (Figure 2), which declined by almost 70% from 2016 to 2022. Long-term EU migration fell before any new policies restricting it came into force – between 2016 and 2020, immigration fell by 35% and net migration declined by more than 80%. Possible explanations for this decline include the fall in the value of the pound, reducing the value of money earned in the UK compared to other EU countries; uncertainty about the political and social situation in the UK after Brexit; and the fact that EU migration had been unusually high in the pre-referendum period and thus might be expected to have fallen anyway. Nonetheless, the figures available so far suggest that the large majority of EU migrants did not leave the UK.

In the same period, overall net migration into the UK continued to rise, reaching an estimated 606,000 in 2022. The fall in EU migration was compensated by a sharp rise in migration from non-EU citizens since 2021. For more information on net migration to the UK, see the Migration Observatory briefing, Net migration to the UK .

The decline in EU net migration particularly affected EU-8 nationals: those from Eastern European countries that joined the EU in 2004, such as Poland. Between the 2016 and 2020 fiscal years, net migration of EU-8 citizens fell by 126%, from 59,000 to -15,000. By contrast, net migration from both EU-14 and EU-2 countries fell by around 40% in the same period (Figure 2). It is unclear if this trend continued after 2020, when the sharpest drop in overall EU net migration was observed, as the pandemic disrupted the collection of migration statistics (for more detail, see Evidence Gaps and Limitations).

Return to top

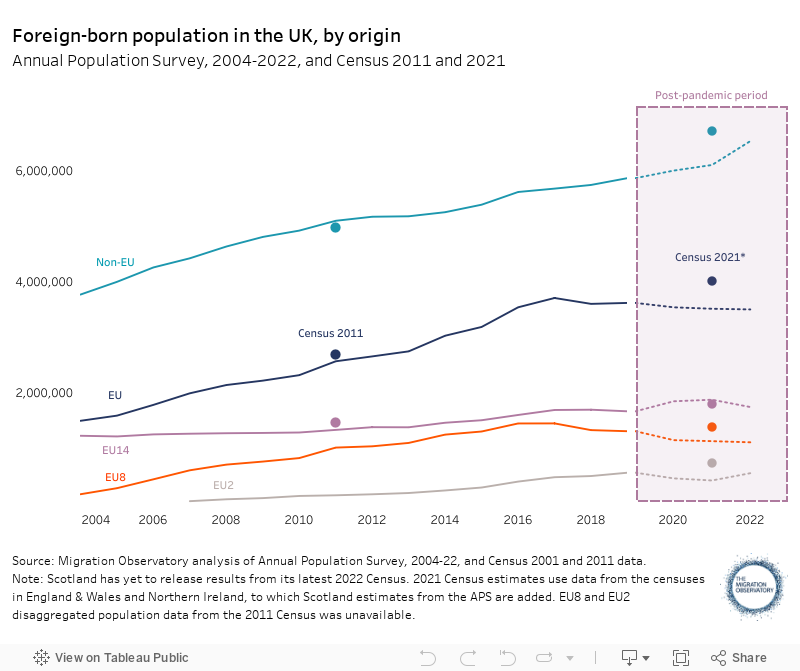

In 2021, there were approximately 4 million EU-born residents in the UK, making up 6% of the population and 37% of all those born abroad

In 2021, there were approximately 4 million EU-born residents in the UK, according to Census data from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and survey-based data from Scotland (see Understanding the Evidence). The number of EU-born residents in the UK increased by around 50% between the 2011 and 2021 Census (from 2.7 million), reflecting a decade of positive net migration. The EU-born population increased faster than the overall population, with its share rising from 4% to 6% by 2021. However, its share among the total foreign-born population rose only slightly, from 35% to 37%. This shows that even as net migration from the EU increased sharply, it continued to make up a little over a third of overall migration.

A large part of the growth in the EU-born population came from an increase in the number of residents from newer EU-8 and EU-2 member states in Central and Eastern Europe, which now make up a majority (52%) of the EU-born population (1.4 million and 700,000, respectively). The share of those born in older EU-14 member states in Western and Southern Europe fell from 54% in 2001 to 45% in 2021 (1.8 million).

While it is clear that the EU-born population increased significantly in the decade to 2021, changes in the size of this population in recent years are more uncertain. Estimates of the foreign-born population between censuses, based on data from the Annual Population Survey, are less accurate and can significantly underestimate the migrant population (see Evidence Gaps and Limitations). Estimates for the year ending June 2021 show the EU-born population at 3.5 million, around half a million lower than the figure found by the 2021 Census. The same data shows the EU-born population in the UK peaking in 2017 and declining since, although the ONS has separately estimated that net migration remained positive until 2020.

The top origin country for EU-born residents is Poland (21%), followed by Romania (14%), the Republic of Ireland (10%), Germany (7%), and Italy (7%)

According to our 2021 population estimates, about a fifth of EU-born residents in the UK are Polish (21%, 826,000). The next largest groups are people born in Romania (14%, 554,000), Ireland (10%, 389,000), Germany (7%, 298,000), and Italy (7%, 298,000). Compared to the previous census in 2011, by far the largest increase in population was seen among those born in the EU-2 countries, Romania and Bulgaria. The Romanian-born population increased almost 7-fold, from a little over 82,000 in 2011. Over the same period, the Bulgarian-born population grew from under 50,000 to around 159,000. The number of UK residents born in Southern European states like Italy, Spain, and Greece also more than doubled in the ten years to 2021. There was substantial variation among top origin countries (Table 1), with smaller increases in the number of people born in Poland and France, a relatively constant number of German-born residents, and a notable fall in the number of those born in the Republic of Ireland.

Yearly population estimates based on the APS seem to indicate a decline in population since 2017-19 among those born in top Eastern European origin countries like Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, and Lithuania that is not visible among those from Western or Southern European member states. However, data collection problems since the pandemic have made these estimates much more uncertain, meaning more data is needed to confirm the trends (see Evidence Gaps and Limitations).

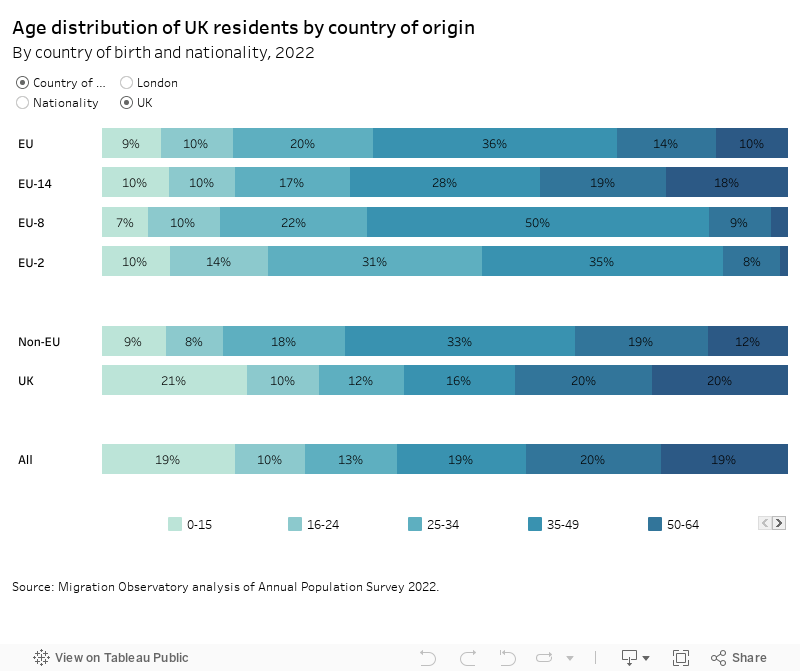

EU-born migrants are more likely to be in the 25 to 34-year-old age group compared to non-EU migrants, but especially compared to the UK-born (Figure 4). About 9% of EU-born migrants were children in 2022. However, the number of EU citizen children is much higher at 17%. This is because there is a substantial number of UK-born EU citizen children. (Some people born in the UK are automatically UK citizens, but this is not always the case and depends on the residence status of the parents at the time the child is born.) For more details on citizenship and children, see the Migration Observatory briefing, Citizenship and naturalisation for migrants in the UK .

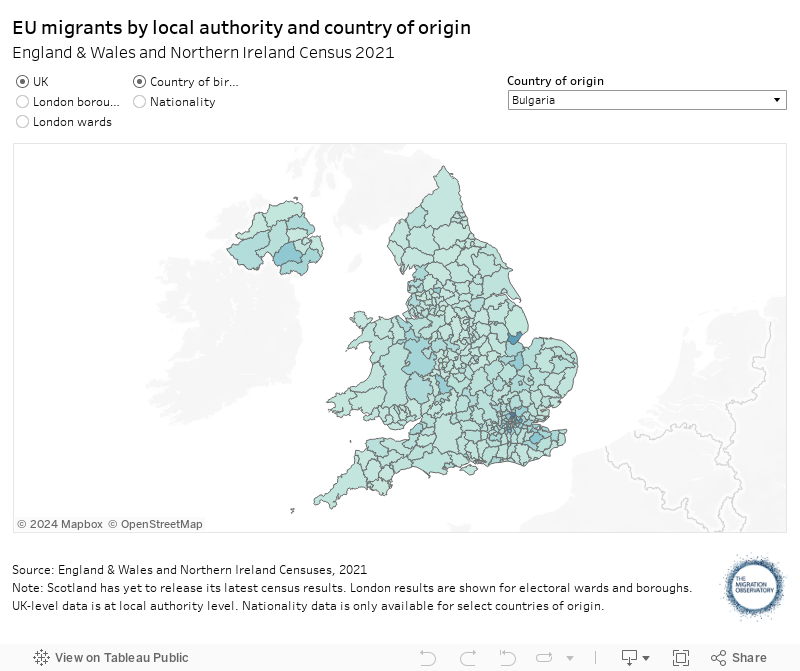

EU migrants in the UK are particularly concentrated in London, although to a lesser extent than those from outside the EU

According to the 2021 Census, the highest concentrations of EU-born residents relative to population can be found in London and the East of England (Figure 5). The local authority with the highest share of EU-born residents was Boston in Lincolnshire (20%). Of the top 10 local authorities by share of EU-born population, 7 were in London, including the rest of the top 5 – Kensington and Chelsea (19%), Haringey (18%), the City of London (18%), and Westminster (18%).

Compared to non-EU migrants, EU migrants are less likely to live in London. There are about 1.1 million EU-born residents in London, or 28% of the UK total; among non-EU migrants, the share that live in London is almost 37% (2.4 million). The EU-born are a minority of the migrant population in most local authorities, although there are some exceptions, particularly in the East of England. More information is available in the Migration Observatory briefing, Where do migrants live in the UK? and the Migration Observatory’s Local Data Guide .

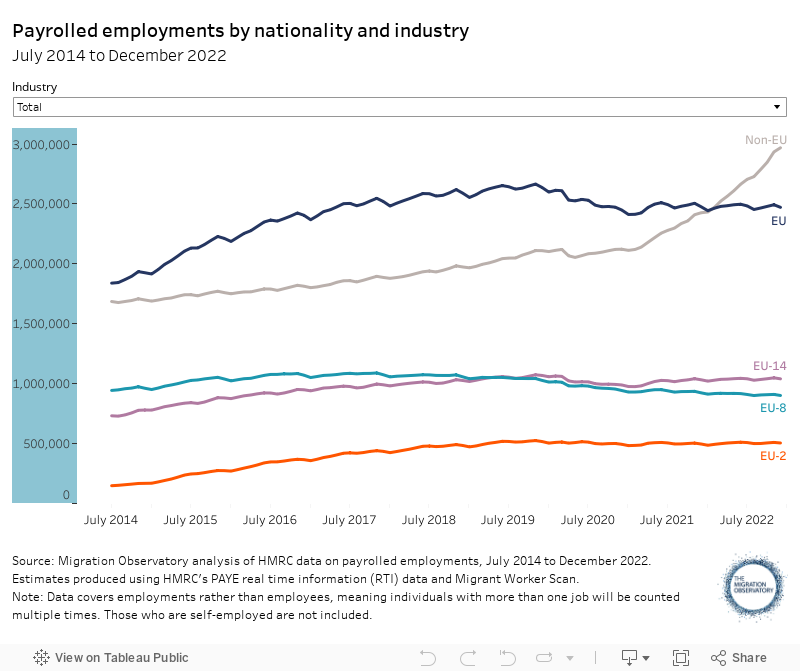

EU nationals make up around 8% of employments in the UK, although their number has declined since 2019

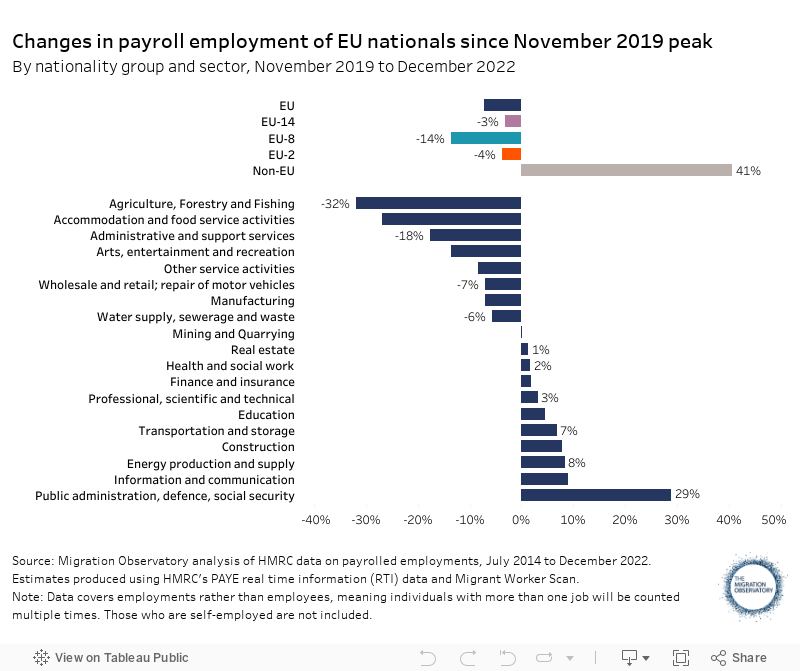

As of December 2022, almost 2.5 million EU nationals were in payrolled employment in the UK, making up about 8% of the total. Among them, the largest group were nationals of EU-14 countries (1 million), followed by those coming from EU-8 (900,000) and EU-2 (505,000) countries. Before the start of 2022, EU nationals made up a majority of foreign employees in the UK, yet their number has since been overtaken by those of non-EU migrants in the labour market (Figure 6). Migrants from the EU work in a wide range of occupations and industries – at the end of 2022, their largest employers in the UK were the administrative and support services (388,000), retail (318,000), hospitality (289,000), and manufacturing sectors (285,000).

Before 2019, the number of EU employments grew steadily – by 45% between July 2014 and November 2019, compared to a much smaller rise among non-EU migrants. Much of the increase was driven by EU-2 nationals from Romania and Bulgaria, whose number more than tripled over the same period of time. The employment of EU nationals, however, peaked in November 2019 at around 2.66 million, and declined sharply during the pandemic, falling by more than 7% as of December 2022. Once again, the sharpest decline in numbers was found among EU-8 nationals. For this group, employments in the UK plateaued around 2016-17 and fell by more than 14% between 2019 and 2022.

The decline in EU workers is likely to be a result of the combined effect of Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic. The employment of EU nationals dropped sharply during 2020 and has only partly recovered since. EU numbers did not bounce back as the economy recovered from the pandemic, as would have been expected had free movement continued. Indeed, take-up of the new immigration system among EU citizens in 2021 and 2022 was very slow (as discussed further below), in contrast to a sharp increase in migration from non-EU countries. At the same time as the employment of EU nationals fell, non-EU nationals’ employee numbers rose by more than 40%. This pattern can be seen across many key economic sectors (Figure 7).

Over time, Brexit and the new immigration system are also expected to shift the balance of jobs that EU workers do in the UK. Compared to free movement, the new system greatly restricted the options for EU citizens to work in occupations that are not classified as skilled (i.e. not requiring at least A-Level or equivalent education and meeting salary thresholds). The pandemic has also affected the balance of jobs available. Employment in some industries, like manufacturing , remains significantly lower than before the pandemic even in 2023, while the number of workers in sectors like health and care has continued to grow .

Employment figures from December 2022 reveal the first effects of this transformation. Compared to November 2019, employment of EU nationals fell particularly sharply in key sectors such as hospitality (-27%) and administrative services (-18%), but also retail and manufacturing (-7% each). In more highly skilled sectors like education, public administration, or information and communication, the number of workers from the EU continued to grow, albeit much more slowly than that of workers from outside the EU.

For more detail on the labour market situation of EU migrants in the UK, see the Migration Observatory briefing, Migrants in the UK Labour Market: An Overview .

An estimated 6.1 million individuals had applied to the EU Settlement Scheme by June 2023

Most EU citizens and their family members already living in the UK before the end of free movement were required to apply to the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) to continue living in the UK legally after 30 June 2021. (See the ‘Understanding the Policy’ section above for more details.)

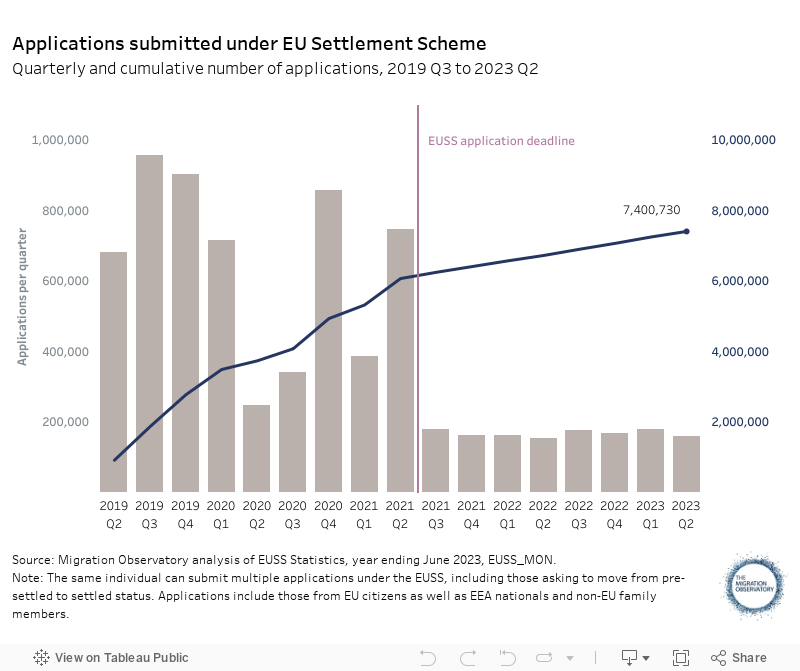

One unexpected outcome of this scheme was the high number of people who applied. By the end of June 2023, an estimated 6.1 million people had applied to EUSS. This includes 5.6m EU citizens, 62,000 EEA/Swiss citizens, and 487,000 non-EEA family members. These figures are lower than the 7.4 million applications during the same period, because around 1.1 million people had applied more than once. Indeed, people with pre-settled status are eventually required to apply again in order to secure settled status.

The original deadline for applications under the EUSS was 30 June 2021. Although most (82%) of the applications have been made by this date, another 1.3 million were submitted in the two years to 30 June 2023, at a relatively steady rate of around 50,000 applications a month (Figure 8). A large share of these are made by repeat applicants or joining family members. However, there were also about 500,000 late applications. Such applications can result in a grant of status if the applicant can prove they were in the UK before 31 December 2020. According to a response to a Freedom of Information request submitted by the Migration Observatory, 48% of late applications that had received a final decision by the end of 2022 resulted in a grant of status. Data from the same period also showed EU-2 nationals were over-represented in this group, making up almost half (47%) of all late applications.

It remains unknown how many people are in the UK without status despite having been eligible to apply for the EUSS, or how many might still apply in the future. The number of late applications has not consistently declined over time and remains at over 15,000 a month as of June 2023. For a more in-depth discussion of the number of people who have not applied to the EUSS, see What Now? The EU Settlement Scheme After the Deadline .

The 5.6 million EU citizen applicants by 30 June 2023 is 1.6 million higher than the official estimate of approximately 4 million EU citizens living in the UK in 2021. This difference is likely to be a combination of two main factors. On one hand, emigration means that some EUSS applicants no longer live in the UK. Anyone who lived in the UK before the end of 2020, no matter how briefly, was potentially eligible to apply to the scheme. Many such migrants have since left the country. On the other hand, official statistics may underestimate the size of the EU migrant population. More accurate estimates based on the Census partly address this, yet some uncertainties remain .

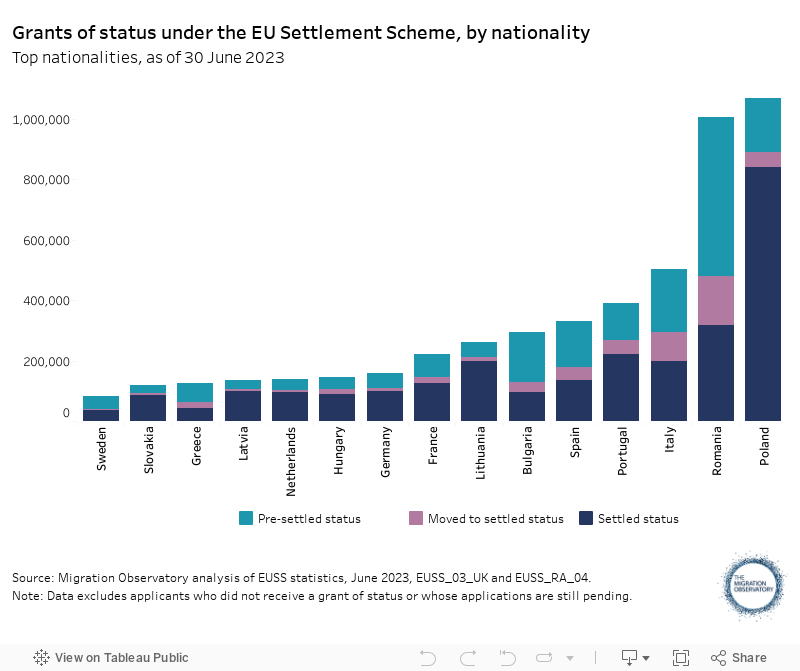

As of June 2023, over 2.1 million people held pre-settled status and may need to reapply to EUSS to remain in the UK permanently

By the end of June 2023, an estimated 2.2 million people held pre-settled status and thus may need to reapply to EUSS if they want to remain in the UK permanently (see ‘Understanding the Policy’, above, for details). The majority of these, 1.9 million, are EU citizens.

By the end of June 2023, approximately 608,000 people had moved from pre-settled to settled status, suggesting that around 22% of those granted pre-settled status had upgraded to settled status. This share varied by nationality, ranging from 8% of Swedish citizens to 31% of Italians. The largest number of people who held pre-settled status at the end of June 2023 were Romanians (529,000), followed by Italians (208,000) and Poles (178,000).

Note that the share of people with pre-settled status who upgrade to settled status will never reach 100%. This is because some people with pre-settled status have left the country with no plans to return, and others will break their period of continuous residence due to absences from the UK. Without further data to understand who is still living in the UK, it will not be possible to identify what share of pre-settled status holders who are still living in the UK have received settled status. At the time of writing, what would happen to people who did not reapply remained uncertain (see the ‘Understanding the Policy’ section).

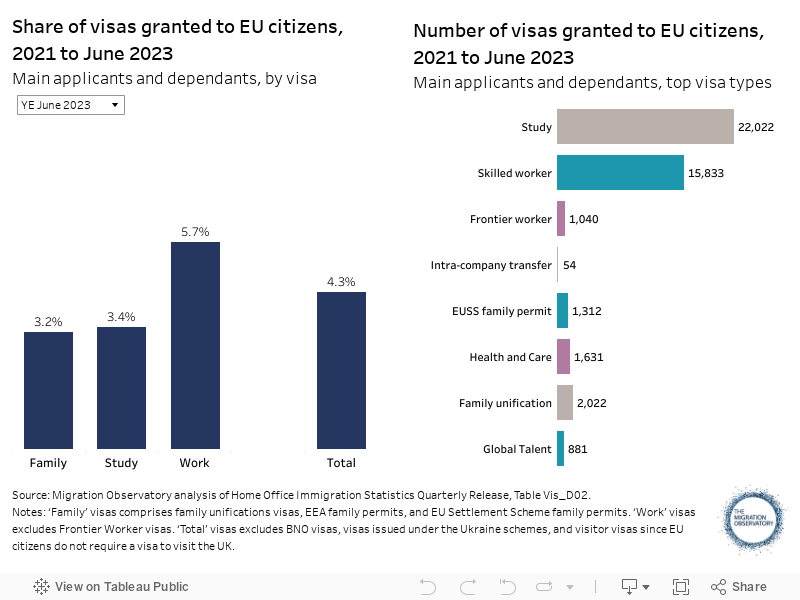

Since the post-Brexit immigration system was introduced in 2021, only 5% of visas were granted to EU nationals

Uptake of the post-Brexit immigration system remains very low among EU nationals. In the two-and-a-half years since free movement ended, from 1 January 2021 to 30 June 2023, EU citizens made up around 5% of all visas granted, excluding visitor visas and those issued under the BNO and Ukraine schemes. This includes around 129,000 EU citizens granted visas, a majority of whom (75,000 or 58%) were issued work visas.

These figures include short-term workers and “frontier workers”—a one-off cohort of people who do not live in the UK but conducted some work here before the end of 2020. Long-term immigration levels from EU citizens coming under the post-Brexit immigration system will thus be substantially lower. If we exclude frontier workers, around 63,000 EU citizens were issued a work visa between January 2021 and June 2023, making up more than 6% of the total. This included over 34,000 EU citizens who were granted skilled worker visas (including health and care visas). The number of EU citizens granted visas has somewhat increased since 2021 (Figure 10) but failed to keep up with the growth in visas issued to non-EU nationals. In 2021, EU migrants made up 6.4% of all visa grants and 8.6% of work visas issued; this had fallen to 4.3% and 5.7%, respectively, in the year ending June 2023.

By contrast, in the year ending March 2019, even after EU migration had already fallen substantially post-referendum, an estimated 410,000 EU citizens made up 58% of non-UK citizens moving long-term to the UK (see Figure 1, above). The share of EU citizens is thus substantially down compared to its trend before the pandemic and Brexit, although the figures may still change over time as people adjust to the new system.

New enrolments of EU students fell by 53% after post-Brexit rules took effect

Post-Brexit rule changes have also led to a sharp decline in the number of international students from the EU. In the 2021/22 academic year, the number of EU-domiciled students enrolling for a new degree in a UK university fell by 53% compared to the year before, from almost 67,000 to a little over 31,000. The decline has been particularly steep among new undergraduate students – new enrolments fell by 63% from 2020/21, compared to only 39% among post-graduate students (Figure 11).

Starting from the 2021/22 academic year, EU citizens have been subject to the same rules as non-EU citizens, including the need to apply for a study visa and pay higher international student tuition fees, without entitlement to government-subsidised loans. The increase in the cost of tuition has affected undergraduates more than post-graduates. Whereas post-graduate fees have always varied widely depending on the type of course, undergraduate fees for EU students were previously capped at the UK level of £9,250 a year; this has now increased by up to 345%, to between £11,400 and £32,000 a year.

While EU student numbers have declined, those of other international students in the UK rose significantly, reaching an all-time high of 350,000 in 2021-22 after a yearly increase of more than 32%. The number of non-EU students started growing in 2016/17 and has roughly doubled since. As a result, EU students now make up just 8% of new international students, compared to almost 27% in the 2016/17 academic year.

For more information on international students in the UK, see the Migration Observatory’s briefing on Student migration to the UK .

EU citizens now make up a majority (53%) of those refused entry at the UK border

In the first half of 2023, around 7,600 EU citizens were initially refused entry at the UK border, a majority (53%) of all those refused entry. This is the result of a sharp increase since post-Brexit rules took effect at the beginning of 2021 (Figure 12). The largest group among those stopped at the border in the first six months of 2021 were citizens of EU-2 countries, particularly Romanians (about 3,800 or 49% in the first half of 2023).

The end of free movement greatly increased the circumstances under which border officers could turn EU citizens away at the border. While EU citizens do not require a visa to enter the UK to visit, border officers have the discretion to turn them away if they believe that they are likely to break immigration rules, such as by working without permission. The sharp increase in EU nationals refused entry to the UK in 2021 sparked media controversy and concern in European capitals after reports of some EU citizens being detained and refused entry despite holding status under the EUSS. The Home Office responded with a clarification , stating that EU citizens refused entry to the UK should not be detained and instead released on immigration bail while they are arranging their return.

While there has been a decline in the number of EU nationals refused entry to the UK since 2021, it remains unclear whether this trend will continue as both officials and travellers better adapt to the new rules. A variety of factors can affect the number of people refused entry, including overall travel volumes, decision-making by border officers, and travellers’ knowledge and understanding of rules changes.

Our main estimates of the 2021 migrant population are obtained by combining data from the latest Census and the APS. The former are still not available in Scotland, meaning APS-derived estimates for the year ending June 2021 were used. The calculations are shown below for different nationality groups, by both country of birth and passport held.

Evidence Gaps and Limitations

The Covid-19 pandemic greatly reduced the quality of some of the UK’s key migration data sources. Survey-based estimates of the population, such as those from the APS, have been particularly affected. The overall response rate of the APS, already below 50% in 2019, fell further during the pandemic. Additionally, migrant non-response to government surveys increased more than that of the UK-born, making comparisons with previous data unreliable. Pending the development of new methodologies, the ONS discontinued their yearly population data on nationality and country of birth in June 2021.

New data sources are being developed that improve our understanding of EU migration. In particular, the new HMRC data on the number of payrolled employees by industry and nationality at the time of registering for a National Insurance Number, represent an important step forward. In future, there is scope to improve the published administrative data, for example with more detail on migration and employment by individual country or region of birth.

Different sources of data on migration and migrants in the UK are not always consistent with each other. There are various reasons for this, including differences in how data sources define migrants; known uncertainty in the estimates, which come with margins of error; and unknown sources of error, such as that arising from the fact that not everyone agrees to participate in official surveys. This means that it is often sensible to look at the overall picture across several data sources, rather than focusing on short-term changes in a single dataset.

Acknowledgements

This briefing was produced with the support of the Economic and Social Research Council and Trust for London. Thanks to Zachary Strain for help updating this briefing and to staff at the Home Office for helpful comments on a previous draft.

- Home Office (2021). How many people continue their stay in the UK or apply to stay permanently?

- Home Office (2021). EU Settlement Scheme quarterly statistics, June 2023.

- Office for National Statistics (2023). EMP13: Employment by industry , August 2023.

- Office for National Statistics (2023). Earnings and employment from Pay As You Earn Real Time Information, UK: September 2023 .

- Office for National Statistics (2021). Quality assurance of Census 2021.

- Complete University Guide (2022). Reddin Survey of university tuition fees .

- Vassiliou, John (2021). EU citizens are being denied entry to the UK – what are the visa rules for visitors? Free movement.

- USA Today (16 Mar 2017) Millions of exiles are caught in Brexit web

- CNN online (05 Oct 2016) UK could force firms to list foreign workers

- Vox (24 Jun 2016) Brexit isn’t about economics. It’s about xenophobia

- The Guardian (13 Jun 2016) Gordon to rescue remain? Then he must do better on immigration

- News.com.au (01 Jun 2016) Brexit campaigners want the UK to adopt an Australian-style points based immigration system

Mihnea V. Cuibus

Download Briefing

Press Contact

If you would like to make a press enquiry, please contact:

+ 44 (0)7500 970081 [email protected]

Contact Us

General Enquiries

T: +44 (0) 1865 612 375 E: [email protected]

Press Enquiries

T: +44 (0)7500 970 081 E: [email protected]

- Newsletter sign up

- Follow us on twitter

- Like us on facebook

- Watch us on vimeo

Connections

This Migration Observatory is kindly supported by the following organisations.

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy & Cookies

The Migration Observatory, at the University of Oxford COMPAS (Centre on Migration, Policy and Society) University of Oxford, 58 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 6QS

- © 2024 The Migration Observatory

- Website by REDBOT

To provide the best possible experience, this website uses cookies. By clicking 'Accept All' you accept our use of cookies.

Necessary Cookies

Necessary cookies are always on and are required to enable core functionality such as secure login. They don't contain personally identifiable data.

Analytical Cookies

Analytical cookies help us understand how visitors interact with our website, providing metrics such as the number of visitors and page views.

Migration to the UK: an introduction

Introduction.

- Background and history

- UK legislation 2010-

- Brexit Impact

- Migration stories

- Human Rights and Migration

- Organisations

This is a brief introduction on some areas of discussion on the topic of migration and immigration to the UK. It looks at the post-WWII era and more narrowly the period from 2010 under the Coalition and Conservative Governments and the Immigration Acts of 2014, 2016 and 2019 and further legislation under the post-2019 governments and Home Secretaries.

In a difficult and complex area, which has profound implications for society, this is an attempt to indicate some key points and to signpost to key sources of information and available resources.

For more information on migration topics and UK policies, see the subject guide to Government and Society and the Institute for Research into Superdiversity at the University of Birmingham (2019).

It is important to note that there are distinctions between the following groups: asylum seekers, refugees, migrants - or immigrants - considered illegal and those considered legal. However, these can often become blurred, both in general thinking and legislation: for example, those with refugee status who are later taken into the general immigration system.

Respected immigration lawyer Colin Yeo (2020) outlines the background and developments in UK Immigration laws and their effects on people's lives, offering a detailed but accessible introduction to the whole topic.

Please note that here are further guides and resource lists from the University of Birmingham on Equality, Diversity and related issues. See: Equality and Diversity Guide including the section on Resource Lists .

Some references to individual books or articles may require University of Birmingham membership and login for full access. It is intended that most material should be openly accessible where at all possible.

References:

Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham (2019) Institute for Research into Superdiversity. Available at: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/activity/superdiversity-institute/index.aspx (Accessed 19 June 2019)

Library Services, University of Birmingham (2020 )Equality and Diversity . Available at: https://libguides.bham.ac.uk/asc/equalityanddiversity (Accessed 29 June 2020)

Library Services, University of Birmingham (2019) Government and Society. Available at: http://libguides.bham.ac.uk/subjectsupport/govsoc (Accessed 28 June 2019)

Yeo, C. (2020) Welcome to Britain : fixing our broken immigration system . London:Biteback Publishing.

geralt / 21808 Images - Pixabay no attribution required. Available at: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/integration-welcome-shaking-hands-1777538/ (Accessed 29 June 2020)

- Next: Background and history >>

- Last Updated: Mar 28, 2024 3:16 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bham.ac.uk/asc/migrationuk

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2021

News media representation on EU immigration before Brexit: the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case

- Marta Martins 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 11 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

6 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

A higher level of mobility of people has marked the European Union (EU), with immigrants moving from one place to another, every year, looking for a better quality of life, often fleeing from war and poverty. In the wake of enlargement of the European Union, the United Kingdom (UK) experienced high inward migration. One of the main focuses of UK media coverage was immigration from Eastern European countries. The UK referendum on Brexit on 23 June 2016, was followed by an increase in hate crimes linked to migration issues and, subsequently, a media apparatus of toxic discourse and fear of the criminal ‘Other’. This paper aims to reveal how newspaper articles and personal comments written in response to these articles, represented creative and media-driven anxieties about ‘opening’ borders in the EU. The empirical sample builds on news media coverage of the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case, published in two UK newspapers—the Daily Mail and The Independent . Based on critical surveillance studies and cultural media studies, I elaborate on the notion of moral panic, dramatised by the media, which mobilises specific compositions of ‘otherness’ by constructing suspicion and criminalising inequality by particular social and ethnic groups and nationalities. I argue that the media portrays the dramatisation of transnational narratives of risk and (in)security, which redraws territorial borders and (re)define Britain’s global identity. The analysis shows how the news media in the Brexit vote continually raised and legitimised awareness related to the migration as a vehicle that enables the ‘folk-devil’ to cross borders. This context postulates an ideology that converges on a relationship of intransigence and criminal convictions, in the context of a politics of inclusion and exclusion. I conclude by emphasising how the media intersects different social and geographical spaces in which migration takes place. Media-constructed categories of suspicion targets have been previously created and ‘suspect communities’ have already been socially accepted, thereby confirming and reshaping understandings of their identities and communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Echoes of Empire: racism and historical amnesia in the British media coverage of migration

Ewa Połońska-Kimunguyi

Transmediatisation of the Covid-19 crisis in Brazil: The emergence of (bio-/geo-)political repertoires of (re-)interpretation

Jaime de Souza Júnior

“Our migrant” and “the other migrant”: migration discourse in the Albanian media, 2015–2018

Elona Dhëmbo, Erka Çaro & Julia Hoxha

Introduction

A broad level of mobility of people has marked the European Union (EU) with immigrants moving from one place to another, every year, looking for a better quality of life, driven primarily by economic factors, such as poverty and lack of employment, and also to escape from war. According to the 2020 report by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2019, it is estimated that there are 272 million immigrants in the world, equivalent to 3.5% of the global population (International Organization for Migration, 2020 ). According to the data, the majority of the population does not cross-national borders, and remains in its home country. The United Kingdom (UK) has had one of the highest levels of immigration, with the flow of immigrants increasing until 2016. With Britain as a member of the EU, EU migrants can relatively freely work and live in Britain under the right of free movement of people. However, contrary to media narratives, these inflows have significantly decreased since then (Clegg, 2019 , p. 8). Yet, the discussion of how immigration influenced (or not) the Brexit vote remains very uncertain. However, as expected, journalists show a greater interest in describing acts of violence committed by people that move around, whose mobility tend to be perceived as a contemporary security problem (see Curtice, 2017 ; Tong and Zuo, 2019 ; Walter, 2019 ).

In the wake of enlargement of the EU, the UK experienced substantial high inward migration. One of the main focuses of UK media coverage was immigration from Eastern European countries. Since 2007, after Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU, the media focused on symbolic, social and political mobility between citizens “inside” and “outside” the EU, reinforcing a pre-existing demarcation between West and East. The enduring public perceptions of these high inward migration was recreated by a persuasive media rhetoric concerning the overall negative impact of “immigration on jobs, wages, housing or the crowding out of public services” (Wadsworth, 2015 , p. 1). These developments in relation to anti-immigration feelings shaped the period during which the UK decided to leave the EU. The result of the UK’s Brexit referendum, held on June 23, 2016, was followed by an increase in hate crimes linked to migration issues and, subsequently, a media apparatus of toxic discourse and fear of the criminal ‘Other’ (Goodwin and Milazzo, 2017 ; Curtice, 2017 ; Eberl et al., 2018 ). The case of the ‘Euro-Ripper’, which is how the criminal case has become known in the UK press, is one example of the biased media coverage linked to migrants. The case received significant media coverage because of the efficacy of transnational exchange of DNA data in the EU to identifying the first serial killer who crossed borders to commit various crimes, which constitutes another dimension of my research Footnote 1 .

On May 21, 2015, the ‘Euro-Ripper’, named Dariusz Pawel Kotwica, a 29-year-old Polish citizen, brutally murdered an elderly couple in Vienna, Austria. This case had transnational dimensions: the investigations went beyond the crimes committed in Austria. It was also alleged that he committed other crimes in several countries across the EU, including the UK (Beckford, 2015 ). Media coverage of the case was incorporated within the referendum debate. The case sparked so much online interest that it can be considered to be a relevant and robust case concerning ‘porous borders’ and the fluidity of movement across the EU. The press has gradually tended to focus on the idea that ‘EU immigration’ concerns a local community that is moving across EU borders, the “not yet European” (Kuus, 2004 , p. 37). After 47 years, the UK has now left the EU. Until now, the British media has never ceased to stress the destructive impacts of the ‘migratory crisis’ (Griffiths, 2017 ; Fox, 2018 ; Hutching and Sullivan, 2019 ).

While several researchers have focused on traditional media portrayals of migrants and crime, in the context of assessments of Brexit (see Dorling, 2016 ; Gurminder 2017 ; Benson, 2019 ) there has been less research into its effects and practices that affect public attitudes (see Griffiths, 2017 ; Fox, 2018 ; Hutchings and Sullivan, 2019 ). This paper is interested in demonstrating how newspaper articles and personal comments written in response thereof, represented creative and media-driven anxieties about ‘opening’ borders in the EU. Precisely, I analyse how online audiences can reflect the “perspectives of a large segment of the population” (Henrich and Holmes, 2013 , p. 2) and therefore are the most suitable way for citizens to express their authentic opinion on a specific topic that is also discussed by other readers (see Da Silva, 2013 ; Coe et al., 2014 ). The study was inspired by the potential for critical discussion and a unique opportunity to provide a relevant case study about the context of the Brexit debate and EU immigration dialogue.

The empirical sample builds on a news media related to coverage of the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case. Based on critical surveillance studies and cultural media studies, I elaborate on the notion of moral panic (Cohen, 2002 ; Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 1994 ) dramatised by the media, which mobilises specific compositions of otherness by constructing suspicion and criminalising inequality by particular social and ethnic groups and nationalities. I analyse ‘moral panic’ as distortion and amplification of “significant others” (Dumitrescu, 2018 , p. 82) caused and legitimised by the media. The distorted image materialises the myth of “folk-devils ” characterised as “ agents responsible for the threat” (Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 1994 , p. 149). Once the figure of the “devil” has been formulated, through the creation of a moral panic, it is easily recognisable. In other words, “folk devils are deviants; they are engaged in wrongdoing; their actions are harmful to society; they are selfish and evil; they must be stopped, their actions neutralised” (Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 1994 , p. 29). These forms of anxiety generated by ‘moral panic’ represented by the media about who we should or should not fear (Krulichová, 2019 ). Thereby, media-constructed categories of previously created targets of suspicion and already socially accepted ‘suspect communities’, confirm and reshape understandings of their identities and communities (Pantazis and Pemberton, 2009 ; El‐Enany, 2018 ; Abbas, 2019 ).

The article is structured as follows: section “The context of the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case” outlines the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case in the media context, focusing on the online debate related to the interlocking reactions of EU immigration after Brexit. Section “Data and methods” explains the methods that guided the design of the study. Drawing on the work of Goode and Ben-Yehuda ( 1994 , p. 156) the analysis is conducted using “five crucial elements or criteria” of moral panic: Concern; Hostility; Consensus; Disproportionality and Volatility. The definition of moral panic stated by the five criteria it is the “most systematic historical and theoretical account of moral panic” (Ungar, 2001 , p. 275). My analysis, therefore, outlines that the public reactions to the EU immigration rhetoric can be analysed within the framework of Stan Cohen’s conceptualisation model, confirming the contemporary utility of moral panic analysis. I argue that the media portrays the dramatisation of transnational narratives of risk and (in)security, which redraws territorial borders and (re)defines Britain’s global identity. The analysis shows how the news media in the Brexit vote continually raised and legitimised awareness related to migration itself as a vehicle that enables the ‘folk-devil’ to cross borders. This context postulates an ideology that converges on a relationship of intransigence and criminal convictions in a politics of inclusion and exclusion. I conclude by emphasising how the media intersects different social and geographical spaces in which migration takes place.

The context of the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case

On May 21, 2015, the newspapers described the violent circumstances in which an elderly couple of 75 and 74 years had been raped, tortured, mutilated and murdered in Vienna, Austria. Following transnational exchange of DNA data in the EU, a 29-year-old Polish man, named Dariusz Pawel Kotwica, was identified (see Machado and Granja, 2018 ). Kotwica, or the ‘Euro-Ripper’, not only confessed to the crime, he also mentioned that several months earlier he had committed another murder in Sweden, near Gothenburg on April 23, of a 79-year old man. Additionally, he confessed that he robbed several stores in 2012 and committed another murder in Salzburg, Austria. Moreover, he admitted to causing grievous bodily harm in the Netherlands, in 2011. In 2015 he stole from a shop in Germany and committed a murder in Sweden. According to police reports, there is still the possibility of further possible murders in the Czech Republic and the Netherlands. Austrian police also found that Dariusz Pawel Kotwica remained in the UK for several years, and therefore suspicions were raised about the possibility that he may have committed other “serious crimes” there (Beckford, 2015 ; Khan, 2015 ). On June 8, 2015, the suspect was arrested at the Düsseldorf railway station in Germany and was immediately extradited to Austria, where he was tried.

The ‘Euro-Ripper’ immediately attracted major media attention. In particular, attention focused on his fluidity and flexibility of movement across six countries over several years. It is also suspected that he may have committed many crimes in the UK, where he lived for many years. Notably, his use of the EU’s open borders became the focus of extreme and harrowing media narratives at the time of the Brexit referendum. This discourse became more pronounced in the UK news media, which focused its attention on ‘Other migrants’ who are crossing borders to find new victims. The agenda-setting raised several public voices who argued that a European society which facilitates freedom of movement of people, goods and services, offers a major opportunity for criminality (Bigo, 2002 , 2014 ; El‐Enany, 2018 ; Abbas, 2019 ; Benson, 2019 ).

My focus in this paper is to show how newspapers articles related to the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case, and personal text comments written in response to the articles, represented processes of belonging, (re)producing pre-existing inequalities and vulnerabilities about a sense of national community that incorporates British identity. A crucial element of this approach is that the online bubble has significantly changed the way that people react to each story and how their beliefs are formulated, “creating new spaces for political expression and participation” (Da Silva, 2013 , p. 176). The following section describes the data and methods analysed in function of the selected newspapers.

Data and methods

For this study, I analysed the comments posted online in response to the two articles published in two UK newspapers related to the ‘Euro-Ripper’ case. The first article was circulated in the Daily Mail (Beckford, 2015 ) entitled “Europe’s first serial killer who raped and murdered his way across continent to Britain: Police investigate Pole who daubed bizarre phrases on woman’s naked body in sickening crime spree across six countries” on 28 November 2015. And the article “Dariusz Pawel Kotwica: ‘Europe’s first serial killer’ could have committed ‘serious crimes’ in Britain” published in The Independent (Khan, 2015 ) on 29 November 2015, after Dariusz Pawel Kotwica was arrested. These articles were selected due to extend and a variety of comments that it generated online. These offer a unique position to think about what inspired the commenters to write about the case.

As Ofcom released its annual report ( 2019 ) on news consumption in the UK, news users are more likely to access news through comments, news links and trends. Though these feature readers could create a conversation that strongly public deliberation of the online public sphere (see Dahlgren, 2009 , p. 168). As Henrich and Holmes ( 2013 , p. 2) explain, “comments cannot be taken as representative of the views of the general population. However, due to the high number of comments available on certain articles, they can reflect the perspectives of a large segment of the population”. I refined the analyses in order to focus on the articles that received the most significant comments. Therefore, due to its news value, the data collection took place exclusively online and provided the presence of 250 comments in the Daily Mail and 14 comments in The Independent . I believe that the approach was sufficient and that the news environment provides a satisfactory proxy that significantly impacts public understanding. Similar to other studies (see Da Silva, 2013 , 2015 ; Boyd, 2016 ), the selection was not made based on the newspapers with the largest circulation. An inclusion criterion was to embrace all comments directly related to the article.

The articles were posted under different platforms available for comments. Daily Mail is a daily newspaper, that is well-known amongst British citizens as a popular right-wing tabloid. In the broadsheet, The Independent , also a daily newspaper, tilted to the left of the political spectrum. Briefly, the tabloid press presents itself as a vehicle for news related to emotion, personal entertainment, with less relevance to politics, the economy, and society at large. The broadsheet press, predominantly, has the privilege of dealing with political, social, economic, and cultural themes with great celebrity to reflection and argumentation (Skovsgaard, 2014 ). At the European level and, according to Mihelj et al. ( 2008 ), both newspapers are general similarities and can be compared across countries.

The Daily Mail newspaper does not have a paywall, which therefore makes it easier for users to read and respond to articles. However, Daily Mail warns that all opinions expressed by users do not necessarily reflect the perspectives and views of the newspaper. It therefore adopts a pre-moderation strategy (see Da Silva, 2013 , p. 182). The administration of comments, prior to their publication, implies that journalists carefully evaluate the quality of all comments before they are published. In The Independent , the comments appear in a section to share thoughts, which is stated to be freely accessible. This uses a post-moderation strategy, in which there is careful evaluation of comments. As a result, abusive comments, even after they have been notified by other users as inappropriate, can remain online for an extended period of time, and, this dynamic may even disrupt the path of the discussion (Da Silva, 2013 , p. 183). In this specific circumstance, due to the undesirable course that many comments triggered, the newspaper progressively chose to delete some comments that did not obey with the established rules. Additionally, as a general rule, this type of interaction is a common way to provide “a truer insight into people’s opinion than those expressed in other contexts” (Henrich and Holmes, 2013 , p. 2), the vast majority of comments in both newspapers required registration, but the option to use a nickname made it possible to remain anonymous.

The analysis uses a grounded theory approach, with a “continuous interplay between analysis and data collection” (Strauss and Corbin, 1994 , p. 273). The unit analysis chosen for coding was the paragraph, coded on the themes addressed following the principles of content analysis in qualitative research, using an approach which combines manifest and latent analysis contexts. For this article, the analysis has directed a careful and critical look at the social and symbolic representations that the press assumes on procedures used in the coverage of the criminal case, where the ‘criminal other’ are the epicentres of the crime narrative.

Moral panic representations of EU immigration before Brexit

Since the original definition of ‘moral panic’ propounded by Cohen ( 1971 , p. 9), the concept has served as an analytical tool. The concept has direct resonance with British press coverage of ‘Euro-Ripper’ case, in particular:

“A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylised and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnosis and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (…) resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible. (…)”.

This concept, since its origin, has undergone a critical academic process. Other authors have followed its analytical conceptualisation. Besides the many advances derived from Cohen’s work, I apply the approach proposed by Goode and Ben-Yehuda ( 1994 ), a “historical and theoretical account of moral panic” (Ungar, 2001 , p. 275). The authors argue that it is possible to examine the potential existence to ‘moral panic’ through the existence (or absence) of five attributes: (1) concern —related to ‘Others’ behaviour and the possible consequences that can lead to action and mobilisation of fear-inducing practices; (2) consensus —that establishes a widespread belief that the problem is real and constitutes a threat; (3) hostility —that the persons responsible come from a group or category of people who have been subjected to inequalities and repulsion; (4) disproportionality —that applies when the issue is greater than the potential damage and, (5) volatility —when panic unexpectedly breaks out and then dissolves with stunning speed.

Table 1 provides an overview of the moral panic applied in the selected newspapers, by presenting the five attributes.

Concern and consensus

According to the UK newspapers , Daily Mail and The Independent , Dariusz Pawel Kotwica was the first criminal who benefited from the Schengen agreement of 14 June 1985, and, therefore, permeable borders have facilitated the ‘uncontrolled travels’ of criminals within the EU. A comment on the Daily Mail article states:

“The Schengen system is a farce and should be scrapped with immediate effect.” (Comment B, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

The media attention on the ‘need’ for border management of risky populations in search of the European dream (see Bigo, 2002 , 2014 ) claims that the volume and intensity of media discourse related to this particular criminal case (re)created a sense of ‘panic’ regarding the free movement of people. Didier Bigo ( 2002 ) makes this situation clear by stating that migration issues have been linked to statements centred on (in)security issues and the media are the ‘heroes’ in this thought-orientation. The newspapers emphasise that the criminal on the move can circulate to other countries with the same purpose in mind. Using a discourse that encourages action and order, the comments demand that borders must be closed immediately: “ Close our borders now !!!!!”, “ We should close our borders now .” (Comment C and E, Daily Mail , 28 November 2015). Similar to other studies related to moral panic in an enlarging EU (see Nellis, 2003 ; Mawby and Gisby, 2009 ; Walsh, 2017 ), the members of the public argue that only the reinstatement of borders can prevent these criminals from finding new victims. According to these comments, this type of criminal can ‘escape’ without punishment, as explained in the following comment:

“This goes to prove that a free of checks border less Europe is a bad thing. Freedom of movement gives people such as this despicable character a massive area to commit crimes, to target vulnerable people then slip away unnoticed. (…) The borders need to be reinstated (…).” (Comment D, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

It is important to recall that since 2015, discussion of Brexit has led to significant challenges for ethnic minorities in the UK. The referendum fuelled a major argument that with Brexit, the UK would have “more control over the flow of immigrants (…) many people are concerned that high levels of immigration may have hurt their jobs, wages and quality of life” (Wadsworth et al., 2015 , p. 2). Also, an increased number of crimes stand linked to migration issues, underlining the social apparatus of open borders in the UK (see Bigo, 2002 ; Clifford and White, 2017 ; Abbas, 2019 , p. 3; El‐Enany, 2018 ). As stated in the following comment:

“We used to have to deal just with our own murderers, rapists and terrorists. Now they come from all over the world thanks to the EU open borders policy.” (Comment F, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

As Elspeth Guild ( 2001 , p. 29) points out, the EU materialises itself as an ‘internal border’, without controls on the basis of nationalism. These norms mobilise a rhetoric based on the idea that borders function as walls. Nevertheless, the idea of belonging has intrinsically been linked to the concept of citizenship, which is called into question when citizens cross borders “leaving the spaces where they belong” (Bigo, 2005 , p. 80). Nevertheless, the comments, in particular in the Daily Mail , fans voices that urge the UK to leave the EU in order not to maintain open borders. The Brexit debate was marked and followed by a discourse that postulates who should belong and who has the right to stay, with a sense of governance:

“ Get us the hell out of the EU .” (Comment X, Daily Mail , 28 November 2015)

“ The referendum should hopefully see a big swing towards ‘NO’ and ‘OUT’ of the EU . Then, everyone will be checked as we won’t have ‘Open Borders’!!!!” (Comment E, Daily Mail , 28 November 2015)

After a string of comments, these voices also offer vivid displays of nationalism and unity, intersecting different social and geographical spaces, in which migration takes place. The data also demonstrates that borders “rather than fixed lines, (…) are now seen as processes, practices, discourses, symbols, institutions or networks through which power works” (Johnson et al., 2011 , p. 62). This framework supports both a State that cultivates social control and exclusion policies for some, as well as more open borders and greater mobility for the enemy, the ‘monsters’ others (Zaiotti, 2007 ; Bosworth and Guild, 2008 ; Bosworth, 2014 ). According to the comments, the political and social regime does not offer solutions. On the contrary, it presents criminals with a ‘ five-star hotel ’. For example:

“Kill and rape all over Europe. Come to Britain and get a five-star hotel.” (Comment H, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

“Thanks to open borders monsters like this exist.” (Comment I, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

People relate open borders to the increase in crime and migratory flows of immigration. One of the main concerns is the open borders made possible by the Schengen system. This framework reaffirms a “borderless world” (Bowling, 2015 , p. 1) in which there is no control and regulation of those who take advantage of the borders’ performance and then commit crimes across States. The outcome of Brexit highlights this context and produces a consensus “posted by (…) borders crossers” (Wonders, 2006 , p. 65) which establishes a rhetoric of threat amplification. Subsequently, measures to combat the problem are shaped by a border control industry, that aims to manage populations which are considered to be suspect. This circulation develops forms of identity that are mapped by specific social practices that can provide an “ideology of circulation” (Lee and LiPuma, 2002 , p. 195) as we will see below.

Hostility and disproportionality

Each country has followed its own cultural and historical development: Eastern European countries have developed for many years on the basis of a historical configuration and creation of a well-marked and incorruptible border between the East and the rest of Europe (see Bigo, 2002 , 2005 ; Kuus, 2004 ; Said, 2004 ; Abbas, 2019 ). As Mignolo and Tlostanova ( 2006 , p. 211) argue, “today, the split configuration of internal others is expressed in the continuing hierarchy of othering”. Over time, Eastern Europeans have been affected by unequal, political and media intolerance. Countries such as Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania, are connoted as messengers of “folk devils”, i.e. are linked to numerous criminal practices and illegal activities. As such, certain Eastern European countries are viewed as sending criminals to rich countries, such as the UK. This context suggests an ideology that converges on a relationship between intransigence and criminal convictions in a politics of inclusion and exclusion. This can be seen in the following comments:

“We have now more criminals entering UK from Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, what next???Albania???? (Capital of crime!!!!) And no one checks at borders!!!! Stupid.” (Comment J, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

“Seems that many don’t watch the amount of Eastern Europeans from Romania and such like that find the UK an easy touch for their crime activities such as pickpockets, shoplifters, burglary, metal theft, farm animal theft among many other illegal activities, and if caught they are let out on bail only to disappear back to Eastern Europe for a while before returning for more of the same. The insanity of the EU is turning the UK into a cesspit.” (Comment N, The Independent, 29 November 2015)

These public discourses instigate the idea that the solution is to control borders, under the same symbolic idea of fighting an “enemy”. In other words, the uncertainty of the unknown is materialised by shared representations about who must enter or leave, in the name of a European identity nationalism (Bigo, 2005 , p. 36). The social impact of this distorted, poorly informed and deeply contaminated media coverage, based on a political game of obscure and harmful interests, often leads to specific individuals and groups to being marginalised and labelled through police interventions and punitive repressions. It is not just a question of punishing or rehabilitating, but of identifying and managing “groups and populations at risk” (Cohen, 1971 ; Mawby and Gisby, 2009 ; Clifford and White, 2017 , p. 164). Several comments alluded to the need for stricter attitudes in the face of this irregular migratory context which is claimed to be linked to criminal practices. The comments point out that the most capable and convenient solution in this situation would be the death penalty, without any tolerance:

“And no European countries have the death penalty …” (…) “It’s a shame that the EU doesn’t have a death penalty . “(…) “And I wonder why the EU abolish penalty for ?!” (Comments R, S and T, Daily Mail , 28 November 2015)

The case of the ‘Euro-Ripper’ is a mediated criminal event, endorsed by the brushstrokes of (in) security. Discourses of vulnerability are consolidated and declared to be imposing when the media reinforces the discourse that fits into a “construction of otherness” (Kuus, 2004 , p. 473). The so-called “war on terror” (Balzacq et al., 2010 , p. 6) is triggering the action of vigilant mechanisms under the sharing of a global threat proliferated, necessarily by unfounded and disproportionate alarmism, identified under the version that the population must be protected:

“Makes me feel sick. Be vigilant people!!!!!” (Comment W, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)

In biopolitical terms, borders not only exercise power and discipline, they also identify circulations and flows considered to be dangerous. As Petit ( 2019 , p. 4) argues, security seems to be under a “backbone” that supports fear, with the ability to create scenarios of terror:

“Disgusting evil pervert, lock him up and let him rot and then throw away the key.” (Comment V, Daily Mail, 28 November 2015)