Working Papers

New research by NBER affiliates, circulated prior to peer review for discussion and comment. NBER Working Papers may not offer policy recommendations or normative judgments about policies, but may report analytic results on the effects of policies. The NBER distributes more than 1,200 Working Papers each year.

Papers issued more than 18 months ago are open access. More recent papers are available without charge to affiliates of subscribing academic institutions, employees of NBER Corporate Associates, government employees in the US, journalists, and residents of low-income countries. All visitors to the NBER website may access up to 3 working papers each year without a subscription.

The NBER endeavors to make its web content accessible to all. To request an accessible version of a Working Paper, please contact [email protected] and one will be provided within 5 business days.

The free New This Week email , which contains the abstracts of each new batch of working papers, is distributed every Monday morning. Account log-in or creation is required.

Sign-Up for the Email

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Does Working from Home Boost Productivity Growth?

Ethan Goode

Brigid Meisenbacher

Download PDF (255 KB)

FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-02 | January 16, 2024

An enduring consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is a notable shift toward remote and hybrid work. This has raised questions regarding whether the shift had a significant effect on the growth rate of U.S. productivity. Analyzing the relationship between GDP per hour growth and the ability to telework across industries shows that industries that are more adaptable to remote work did not experience a bigger decline or boost in productivity growth since 2020 than less adaptable industries. Thus, teleworking most likely has neither substantially held back nor boosted productivity growth.

The U.S. labor market experienced a massive increase in remote and hybrid work during the COVID-19 pandemic. At its peak, more than 60% of paid workdays were done remotely—compared with only 5% before the pandemic. As of December 2023, about 30% of paid workdays are still done remotely (Barrero, Bloom, and Davis 2021).

Some reports have suggested that teleworking might either boost or harm overall productivity in the economy. And certainly, overall productivity statistics have been volatile. In 2020, U.S. productivity growth surged. This led to optimistic views in the media about the gains from forced digital innovation and the productivity benefits of remote work. However, the surge ended, and productivity growth has retreated to roughly its pre-pandemic trend. Fernald and Li (2022) find from aggregate data that this pattern was largely explained by a predictable cyclical effect from the economy’s downturn and recovery.

In aggregate data, it thus appears difficult to see a large cumulative effect—either positive or negative—from the pandemic so far. But it is possible that aggregate data obscure the effects of teleworking. For example, factors beyond telework could have affected the overall pace of productivity growth. Surveys of businesses have found mixed effects from the pandemic, with many businesses reporting substantial productivity disruptions.

In this Economic Letter , we ask whether we can detect the effects of remote work in the productivity performance of different industries. There are large differences across sectors in how easy it is to work off-site. Thus, if remote work boosts productivity in a substantial way, then it should improve productivity performance, especially in those industries where teleworking is easy to arrange and widely adopted, such as professional services, compared with those where tasks need to be performed in person, such as restaurants.

After controlling for pre-pandemic trends in industry productivity growth rates, we find little statistical relationship between telework and pandemic productivity performance. We conclude that the shift to remote work, on its own, is unlikely to be a major factor explaining differences across sectors in productivity performance. By extension, despite the important social and cultural effects of increased telework, the shift is unlikely to be a major factor explaining changes in aggregate productivity.

Possible productivity effects of telework

Teleworking might affect output per hour in different ways. For example, in surveys, many workers claim to be more productive remotely (Barrero et al 2021). That said, some workers might face more disruptions, such as childcare demands or inferior equipment. In addition, idea sharing may be more difficult online, and workers may need to devote time to learning new skills. Alternatively, any association between the ability to telework and productivity performance could reflect other factors. For example, industries where the majority of work needs to be done in person could have faced more disruptions from social-distancing requirements or supply chain bottlenecks.

Thus, in theory the relationship between telework and productivity balances both positive and negative effects. The net effect may also change over time as businesses and workers adjust to new modes of working.

Empirical evidence tends to involve relatively narrow sets of tasks, such as call centers, where output can be easily measured. For example, Bloom et al. (2015) find that workers in a call center in China who were randomly assigned to remote work were more productive than in-person workers. In contrast, Emanuel and Harrington (2023) find that call-center workers at a Fortune 500 company were slightly less productive after they were forced to work remotely at the onset of the pandemic. Emanuel and Harrington (2023) discuss other literature that finds a mix of productivity gains and costs. Because of the narrow scope of the empirical evidence, we turn to industry data to provide more insight.

Measuring productivity growth by industry

In this Letter , we measure industry productivity by output, using value added, per hour. We focus on 43 industries that span the private economy, including, for example, chemical manufacturing, retail trade, and accommodation and food services. We exclude the real estate, rental, and leasing industry because a large fraction of output in this industry is imputed rather than directly measured.

We construct industry-level productivity by combining national accounts measures of output by industry from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and all-employee aggregate weekly hours from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Our industry-level productivity data set is available quarterly starting in the second quarter of 2006 and ending in the first quarter of 2023. For each industry, we calculate the average annualized growth in quarterly productivity to measure changes in industry productivity over the pandemic.

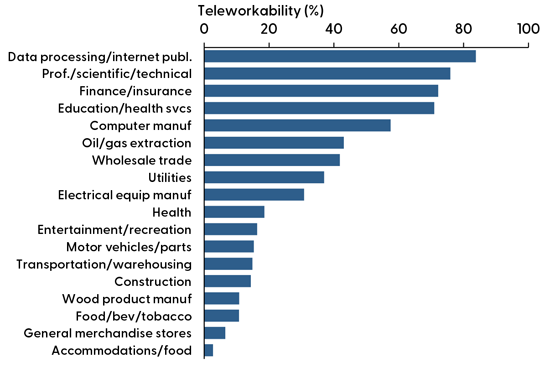

We measure teleworkability by industry using the occupational mix of different industries and the teleworkability of different occupations. For the latter, we rely on occupational teleworkability scores from Dingel and Neiman (2020), which assigns 462 occupations a score between zero and one based on the job characteristics reported in the O*NET survey. Occupations that cannot be done remotely, such as custodial workers and waiters, were given a score of zero, while entirely teleworkable jobs, such as mathematicians and research scientists, received scores of one. Occupations that fall between the poles include counselors and medical records technicians, which receive scores of 0.5. Bick, Blandin, and Mertens (2020) report that actual teleworking shares are highly related to the Dingel and Neiman measures.

We aggregate these occupation-level scores to an industry-level average by weighing the teleworkability score for each occupation by the 2018 share of industry employment from the BLS Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics. For example, we assign the data processing industry a score of 0.88 because most of the workers in this industry are in highly teleworkable occupations, such as software developers and programmers.

Figure 1 displays scores for a subset of industries ordered from the most teleworkable on the top to the least teleworkable on the bottom. The most teleworkable industries are data processing and professional services. The least teleworkable industries are accommodation and food services and some retailers. The figure demonstrates that teleworkability varies widely across industries, ranging from less than 10% to close to 90% of an industry’s workers.

Figure 1 Teleworkability by industry

Industry productivity and teleworkability

Since industries differ considerably in their adaptability to remote work, one would imagine that the shift to telework during the pandemic would affect industries differently. For example, if teleworking offered an important way to circumvent production disruptions brought on by the pandemic, teleworkable industries would have performed better because they faced lower costs to adopting teleworking.

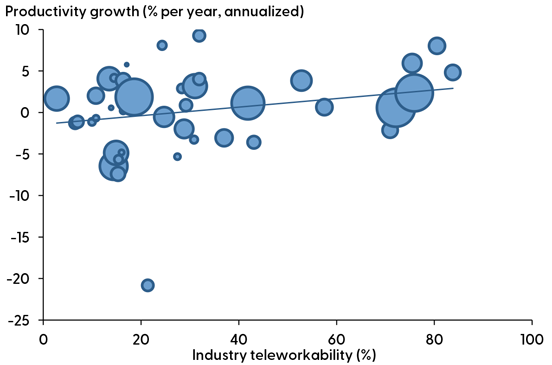

We next examine this relationship between teleworkability and industry productivity growth during and following the pandemic, shown in Figure 2. The horizontal axis measures teleworkability by industry, constructed from the Dingel and Neiman measures in Figure 1. The vertical axis is annualized quarterly productivity growth from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2023, measured in percentage points. The size of the bubbles conveys the pre-pandemic share of an industry’s contribution to total output, measured as industry value-added, as of the fourth quarter of 2019.

Figure 2 Industry productivity growth versus teleworkability

The blue fitted line reflects the average relationship between the two variables. The figure shows that more-teleworkable industries grew somewhat faster during the pandemic than less-teleworkable industries. A 1 percentage point increase in teleworkability is associated with a 0.05 percentage point increase in an industry’s predicted pandemic productivity growth rate. The relationship is statistically significant.

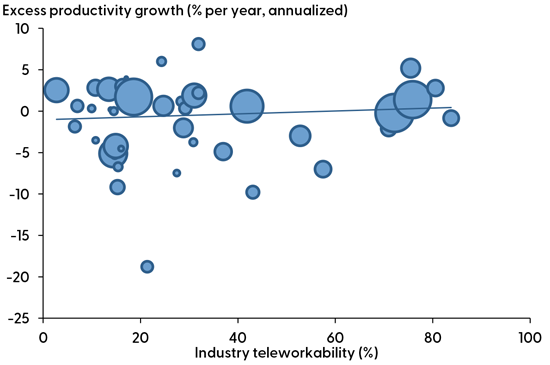

However, it turns out that more-teleworkable industries also grew faster before the pandemic. To better isolate the association with the shift to remote work during the pandemic, Figure 3 controls for pre-pandemic trends by removing each industry’s average annualized productivity growth for 2006–2019 from its pandemic average. Hence, the vertical axis now captures the amount by which an industry’s pandemic productivity growth exceeded or fell short of its pre-pandemic pace.

In Figure 3, the nearly flat blue line reflects that there is essentially no relationship between teleworkability and excess pandemic productivity growth. Although the association is still slightly positive, the relationship is much weaker than in Figure 2 and is not statistically significant.

Figure 3 Productivity growth, accounting for pre-pandemic trends

Both Figures 2 and 3, show that productivity growth varied significantly across industries. But based on Figure 3, it appears unlikely that the differences in performance during the pandemic across industries have much to do with differences in teleworking. Fernald and Li (2022) take the analysis one step further by considering that growth in work hours might be mismeasured to the extent that people are working more “off the clock” (Barrero et al. 2021). That analysis reinforces the conclusion from Figure 3, that there is essentially no relationship between teleworkability and pandemic productivity growth. We found similar results using only data during 2020 when firms were first adjusting to new work arrangements. The results are also similar for 2021-23, when firms had more experience with remote work and were also shifting to reopening office workspaces and, increasingly, to hybrid work.

The shift to remote and hybrid work has reshaped society in important ways, and these effects are likely to continue to evolve. For example, with less time spent commuting, some people have moved out of cities, and the lines between work and home life have blurred. Despite these noteworthy effects, in this Letter we find little evidence in industry data that the shift to remote and hybrid work has either substantially held back or boosted the rate of productivity growth.

Our findings do not rule out possible future changes in productivity growth from the spread of remote work. The economic environment has changed in many ways during and since the pandemic, which could have masked the longer-run effects of teleworking. Continuous innovation is the key to sustained productivity growth. Working remotely could foster innovation through a reduction in communication costs and improved talent allocation across geographic areas. However, working off-site could also hamper innovation by reducing in-person office interactions that foster idea generation and diffusion. The future of work is likely to be a hybrid format that balances the benefits and limitations of remote work.

Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicolas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. 2021. “Why Working from Home Will Stick.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. Updated survey results available from https://wfhresearch.com/ .

Bick, Alexander, Adam Blandin, and Karel Mertens. 2020. “ Work from Home before and after the COVID-19 Outbreak .” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 15(4), pp. 1-39.

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying. 2015. “Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 130(1), pp. 165¬-218.

Dingel, Jonathan I., and Brent Neiman. 2020. “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?” Journal of Public Economics 189(104235).

Emanuel, Natalia, and Emma Harrington. 2023. “ Working Remotely? Selection, Treatment, and the Market for Remote Work .” FRB New York Staff Report 1061 (May).

Fernald, John, and Huiyu Li. 2022. “ The Impact of COVID on Productivity and Potential Output .” Paper presented at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, WY, August 25.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to [email protected]

Hybrid is the future of work

Key takeaways.

- Hybrid working arrangements balance the benefits of being in the office with the benefits of working from home.

- Before implementing hybrid policies, executives and managers need to think through the implications of how and when employees work remotely.

- Issues of equity and equal treatment need to be carefully considered in a hybrid work arrangement.

As businesses and everyday life slowly return to pre-pandemic activity, one point is becoming clear: The home office isn’t about to shut down. In my research and discussions with hundreds of managers across different industries, I’m finding that about 70 percent of firms — from tiny companies to massive multinationals like Apple, Google, Citi and HSBC — plan to implement some form of hybrid working arrangements so their employees can divide their time between collaborating with colleagues on site and working from home.

Hybrid arrangements balance the benefits of being in the office in person — greater ability to collaborate, innovate and build culture — with the benefits of quiet and the lack of commuting that come from working from home. Firms often suggest employees work two days a week at home, focusing on individual tasks or small meetings, and three days a week in the office, for larger meetings, training and social events.

That chimes with the recent evidence from my research with Paul Mizen and Shivani Taneja that small meetings can be as efficient by video call as in person. In-person meetings are typically easier for communicating by visual cues and gestures. But video calls save the travel time required to meet in person. And since video calls for two to four people mean everyone occupies a large box on a Zoom screen, it is easy to be seen.

In contrast, almost half of respondents to our research survey reported large meetings of 10 or more people were worse by video call. People are allocated to smaller boxes in these situations so it is hard to see the faces and gestures of participants. And attendees normally have to mute, leading to stilted conversations.

A matter of choice?

But another question is controversial: How much choice should workers have in the days they work from home?

On the one hand, many managers are passionate that their employees should determine their own schedule. In my research with Jose Barrero and Steve Davis we surveyed more than 35,000 Americans since May 2020 and our research data show that post-pandemic 32 percent of employees say they never want to return to working in the office.

Figure 1: Small meetings can work by video conference; large meetings are best in person.

Question: "How do meetings compare by video call (Zoom, Teams, etc.) versus in person in terms of how efficient the meetings turn out to be?”

These are often employees with young kids who live in the suburbs and for whom the commute to work is painful. At the other extreme, 21 percent tell us they never want to spend another day working from home. These are often young, single employees or empty nesters in city-center apartments.

Figure 2: Employees are hugely varied in how many days per week they want to WFH.

Response to: "In 2022+ (after COVID) how often would you like to have paid work-days at home?"

Given such radically different views, it seems natural to let them choose. One manager told me, “I treat my team like adults. They get to decide when and where they work, as long as they get their jobs done.”

But I have three concerns — concerns, which after talking to hundreds of firms over the last year, have led me to change my advice from supporting to being against employees’ choosing their own WFH days.

A management nightmare?

One concern is managing a hybrid team, where some people are at home and others are at the office. Many workers are expressing anxiety about this generating an office in-group and a home out-group. For example, employees at home can see glances or whispering in the office conference room but can’t tell exactly what is going on. Even when firms try to avoid this by requiring office employees to take video calls from their desks, home employees have told me that they can still feel excluded. They know after the meeting ends the folks in the office may chat in the corridor or go grab a coffee together.

The second concern is what every firm has been fearing: [1] That given a choice, most employees will take Monday and Friday off. Indeed, only 36 percent of employees would choose to come in on Friday compared with 82 percent on Wednesday. This highlights the severe problems firms could face over effective use of office space if they let employees pick their days to work from home. Providing enough desks for every employee coming in on Wednesday would leave half of these desks empty on Monday and Friday.

Figure 3: Efficient use of office space will require central coordination.

Question: "If you got to work from home for two days per week which two days would you choose?"

The third concern is the risk to diversity in the workplace. It turns out that who wants to work from home after the pandemic is not random. In our research we find, for example, that among college graduates with young children, women want to work from home full time almost 50 percent more than men.

Figure 4: College-educated women and men with younger children differ in the number of days they want to WFH post-pandemic.

Note: College educated employees with children under 12.

This is worrying given the evidence that working from home while your colleagues are in the office can be highly damaging to your career.

In a 2015 study I conducted with a large multinational company based in China, my colleagues and I randomized 250 volunteers into a group that worked remotely for four days a week and another group that remained in the office full time. We found that WFH employees had a 50 percent lower rate of promotion after 21 months compared with their office colleagues. This huge WFH promotion penalty chimes with comments I’ve heard over the years from managers that home-based employees often get passed over on promotions.

Adding this up, you can see how allowing employees to choose their WFH schedules could exacerbate the lack of workplace diversity. Single young men could all choose to come into the office five days a week and rocket up the firm, while employees who live far from the office or have young children and choose to WFH most days are held back. This would be both a diversity loss and a legal time bomb for companies.

I changed my mind

Based on this evidence I changed my mind and started advising firms that managers should decide which days their team should WFH. For example, if the manager decides WFH days are going to be Wednesday and Friday, everyone should work from home on those days and everyone should come to the office on the other days. Importantly, this should apply to the CEO downwards. If the top managers start coming in on extra days, then the managers one level below start coming in on extra days to curry favor with their bosses, and then managers two levels down start coming in on extra days to curry favor with their bosses, and so on until the system will collapse.

The pandemic has started a revolution in how we work, and our research shows working from home can make firms more productive and employees happier. But like all revolutions, this is difficult to navigate. Firms need leadership from the top to ensure their work force remains diverse and truly inclusive.

1 “Empty offices on Monday and Friday spell trouble,” Financial Times , May 15, 2021, Pilita Clark.

Barrero, Jose, Nicholas Bloom and Steve Davis. "Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 28731, April 2021.

Bloom, Nicholas, Paul Mizen and Shivani Taneja. "Returning to the office will be hard," CEPR VOXEU, June 2021.

Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts and Zhichun Jenny Ying. "Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment," Quarterly Journal of Economics , 2015.

Related Topics

- Policy Brief

More Publications

The minimum wage and the market for low-skilled labor: why a decade can make a difference, policy options for food assistance in india: lessons from the united states, ceo compensation for major us companies in 2006.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Working from Home: Before and After the Pandemic

Hilary Silver on pandemic trends.

People have always worked at home. The spatial separation of workplace and residence, fueled by the Industrial Revolution and reinforced by zoning codes, has never been complete. Employers build worker housing, small businesspeople live above the store, and generations of women take in piecework while tending to their families. The family farm persists.

In the United States, as agriculture contracted and factories and offices expanded, paid work in the home did dwindle over time. This trend began to reverse in the 1980s with the increasing application of information technology to many types of service work. But working from home really took off with the coronavirus pandemic.

Trends in homework

Decennial censuses show home-working was declining, both absolutely and relatively, from 4.7 million in 1960 to 2.2 million in 1980 (at right, top). Between 1980 and 1990, however, the Census Bureau reports a 56% rise, to 3.4 million people. In the 2000 census, nearly 4.2 million, or 3.2% of American workers, labored where they lived. Since then, the American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates document a continuous rise. By 2020, over 11 million people, or 7.3% of the U.S. labor force, reported their primary job was mostly performed at home. The 2021 ACS one-year estimate was 27.6 million people primarily working from home nationwide, or 17.9% of employees.

The Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Surveys (HPS) were designed to collect data quickly and efficiently on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on American households. From August 2020 to July 2021, they asked, “Did any adults in this household substitute some or all of their typical in-person work for telework because of the coronavirus?“ Responses documented the rise in remote work, followed by a decline and levelling off above pre-pandemic levels (second Figure below).

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) asked a slightly different question in its Current Population Survey (CPS): “At any time in the last four weeks, did you telework or work at home for pay because of the coronavirus pandemic?” Approximately 20% of respondents answered affirmatively as pandemic lock-downs entered their sixth month, though that portion fell to 17% by November 2021. The BLS American Time Use Survey reported that in 2021, 38% of employed persons did some or all of their work at home on days they worked, for an average of 5.6 hours, and 68% did some or all of their work at their workplace, for 7.8 hours on average. This compared to 24% at home and 82% onsite, respectively, in 2019.

Number of people working at home (principal place of work in primary job)

Note: Prior to the 2010 Census, decennial censuses asked about commuting. Commuting data is no longer included in censuses, but rather in the ACS. Five year ACS estimates are averaged over the years included in the range, so the latest ACS mostly represents pre-pandemic practices. Source: U.S. Census Bureau. Decennial Censuses and the five-year American Community Survey 2010-15 and 2016-2020.

U.S. teleworkers due to the coronavirus pandemic, by week (August 2020-July 2021)

Note: Weeks 13-27 refers to “Some adult in household substituted some or all of their typical in-person work for telework because of the coronavirus pandemic.” Weeks 28-32 refer to “some adult in household teleworked in the last 7 days” and “because of the coronavirus pandemic,” excluding those teleworking not because of the pandemic.

Source: Household Pulse Surveys Week 13 August 19-31, 2020, through Week 27 March 17-29, 2021, and Week 28 April 14-26, 2021, through Week 31 July 23-August 8, 2021.

Government figures on homeworking diverge from those in private surveys. For example, Gallup’s State of the American Workforce Report, found that 43% of employees spent “at least some of their time” working remotely in 2016, up from 39% in 2012. Gallup’s June 2022 poll found 70 million or 56% of fulltime employees said they can do their job remotely. Of those, three in ten (21 million) currently worked exclusively at home, down from four in ten in February 2022, while another five in ten (35 million) worked at home part of the time.

The discrepancies in official statistics have a number of sources. First, the Census Bureau has concentrated on people’s usual means of transportation to their main job. Transportation data show a precipitous drop in commuting in the early pandemic, with taxis the only form of transit that increased. But many people have secondary, home-based jobs or businesses, or perform part of their primary job at home and part elsewhere. Some surveys confine attention to full-time, continuously employed, wage-and-salary employees, excluding part-time, moonlighting, and self-employed workers. Second, sample sizes, methodologies, and terminology differ. Online surveys oversample the more educated and can capture responses from business owners or employers right alongside employees. Vague language is a further complication. Using synonyms like remote work or telecommuting is consequential, as not everyone working remotely is doing so at home or via information technology.

Workers who teleworked or worked from home in the last 7 days, by days of home work

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. Household Pulse Survey. Weeks 46-48

A third reason for figures to vary is the unit of analysis. The new HPS surveys households, not individuals, so it undercounts homeworkers living with other homeworkers. The Census Bureau’s 2022 Annual Business Survey is based on employers, finding the percentage of businesses with employees who worked from home rose from 28.1 in 2019 to 41.9 in 2020, a huge surge even before the pandemic.

Finally, changes in survey wording over time complicate the data. HPS surveys, for instance, initially focused on substituting telework due to COVID-19, but in the summer of 2022, began to ask simply how many days in the last week people had teleworked or worked from home (see above). In these data, we see that since the early 2022 Omicron surge, the number of homeworkers stabilized. As of July 2022, 67,977,728 people, or more than a quarter of the U.S. labor force, were working at home at least one day a week. Over half of those (38 million individuals) reported working at home five or more days in the week (far exceeding the 11 million Americans who responded in the 2016-2020 wave of the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey that their primary place of work was their home). Still, full-time home-working is slowly declining compared to hybrid and workplace-based work.

Surveys conducted by non-government agencies do seem to confirm the Yes, 5 or more days trends seen in government data. For example, the monthly online Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes reported that less than 5% of days were worked at home before the pandemic, rising to a high watermark on May 1, 2020, with fully 61.5% of full-paid working days worked at home, then a decline to 37% by the end of the year and 29.5% by August 2022, holding steady since. (European data, by the way, also found increases in working from home, though the rises were relatively more modest: Eurofound’s fifth round of the Living, Working, and COVID-19 e-survey of EU workers reported just over 33% working exclusively from home in mid-2020, falling to 12% by spring 2022, and a fairly constant rate of hybrid home-working of 18%.)

A sociological profile of homeworkers

What do contemporary homework-ers look like? In the past, homeworkers were thought of as low-paid contingent workers, marginal small business owners, or independent contractors. Nowadays, they tend to have a slightly higher social status and be more engaged in privileged, well-paid occupations and knowledge industries than on-site workers (see next page). Homeworkers earn more and have more assets than the average worker. In general, they are older, non-Hispanic White, highly-educated, and in better health. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report for November 6, 2020 stated that teleworking significantly reduced the likelihood of testing positive for COVID-19.

Social profile of U.S. labor force and homeworkers

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2016-2020, five-year estimates.

Eleven percent of homeworkers are Hispanic or Latino American, in contrast to 17% of the American labor force. Eighteen percent of homeworkers are Black, compared to 12% of U.S. workers, and 7% are Asian. According to a November 2020 analysis of data from the second phase of the HPS by the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge, racial disparities in access to remote work were explained mainly, but not completely, by differences in income and education, age, and location. Similarly, with CPS data, a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) study found occupation explained more than 60% of the total effect of race on tele-working for Black and Hispanic workers.

Historically, women were more likely to work at home than men. During the early Industrial Revolution, women performed piece work at home and were paid a fixed rate for each unit produced or action performed instead of an hourly wage. This way, they could combine child care and earning in one place. In 1980, 53.6% of homeworkers were female; in 2020, just before the pandemic, 51% were. Coronavirus kept more men home.

If gender is defined more subtly, 49.1% of teleworkers were female “at birth.” According to the June 2022 HPS, 32% of cisgender males, 29% of cisgender females, and 30% of the 2 million transgender respondents teleworked in the last 7 days, compared to 30% of the entire labor force. When asked about one’s “sexual orientation” rather than gender, 39% of LGBT respondents teleworked at least one day in the last week, considerably more than the 30% of straight respondents. It is important to recall, however, that the HPS is still experimenting with measures of gender and sexual orientation and so, these figures should be regarded with caution.

Home work today, unlike in the past, is associated with higher than average pay. The ACS data at left show these workers’ median earnings in the past twelve months in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars was $51,673 compared to the national median of $40,122. Looked at another way, 24% of the U.S. labor force lives below the poverty line, but just 17% of homeworkers do.

Homeworkers have more assets, too. Perhaps unsurprising is the fact that nearly three-quarters of homeworkers own their homes compared to two-thirds of the overall labor force. More unexpected is the finding that, even though they do not commute to work, only 4% of homeworkers do not own a car, the same percentage as among the general labor force. In fact, like workers overall, three-quarters of their households own two or more cars.

Although pre-pandemic time use data show average full-time workers spent more time alone when they teleworked, which led to an increase in loneliness for some, recent ACS demographics imply that homeworkers are not especially isolated. Their households are somewhat larger than households of those who work on-site. Only 5% of homeworkers live alone, compared to 10% of non-homeworkers. In fact, 27% of teleworkers lived in two-person households, compared to 33% of non-teleworkers. Teleworkers are more likely to be married (60%) compared to non-teleworkers (51%), but are about as likely to have children (42% vs. 40%). Forty percent of the married households and 38% of the households with children teleworked. This implies that child care is not the only reason people are working at home.

An analysis of pre-pandemic time use diaries by Sabrina Pabilonia and Victoria Vernon examined hours of child care by homeworking mothers and fathers. While they saved time on commuting and grooming, fathers increased time on primary child care, while women increased household chores. Since the pandemic, these authors found with the 2021 American Time Use Survey, women were more likely than men to do some or all of their work at home on work days—42% of women, 35% of men. Parents in dual-career couples working from home alone increased childcare hours compared to on-site workers, but mothers also reduced paid work hours. When both parents worked from home, mothers and fathers maintained their paid hours and spent more time on childcare. Parents working from home did equally more household chores, although fathers working from home alone did more compared to on-site working fathers.

Class of worker of U.S. labor force and homeworkers

Industrial distribution of labor force and homeworkers

Occupational distribution of labor force and homeworkers

Workers 16 years and older

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey five-year estimates 2016-2020

When examining homeworkers’ employment, one distinction stands out: they are more likely to be self-employed. This has long been the case. In 1990, 54% of those working at home were self-employed, 10 times the rate of self-employment among those who worked away from home, while 17% were government workers, compared to 6% of non-homeworkers. In 2019, one-fourth of those working mainly from home were self-employed compared to 6% of the overall U.S. labor force. Only 7% of home-workers are government employees.

Homework does not compose a majority of any significant industry, but as the 2016-20 ACS shows, 11% of those working in agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, and mining; 14% in the information sector; 13.6% in finance, insurance, and real estate; and 15.5% in professional services work primarily at home. Indeed, compared to the 7.3% of the American labor force working at home just before the pandemic, home-workers are especially overrepresented in professional and financial services. While remote work increased in most industries, it is much more common in those with better educated and better paid labor (for instance, technology, communications, professional services, and finance and insurance workers).

Similarly, occupations that work with goods, whether producing, maintaining, or moving them, are much less likely to be performed at home. Three-fifths of all homeworking occupations are in management, business, science, and the arts.

Finally, the industrial distribution of homework is reflected in its bicoastal geography. Based on both the May 2020 and February 2021 CPS, workers in the New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Pacific regions, were most likely to be teleworking, while those in East South Central states were significantly least likely.

Prospects for homework

As the pandemic subsides, many firms are calling employees back to the workplace. Bosses worry about productivity and creativity. Two-thirds of executives in PwC’s Remote Work Survey said a typical employee should be in the office at least three days a week to maintain a distinct company culture. Cities are worrying about vacant office space and shuttered downtown businesses. But polls like Gallup’s or McKinsey’s American Opportunity Survey and job search data from Lightcast suggest a majority of workers would prefer to labor remotely all or part of the week, with many remote workers even willing to quit if forced to return to the workplace full time. Long commutes, care responsibilities, and lifestyle contribute to the resistance. Given the leveling off of homeworking trends, remote work—at least for part of the work week—may be here to stay.

Faced with worker shortages and the cost of office space, employers are also offering telework to broaden recruitment pools, reduce turnover, and moderate employee compensation. Around 40% of U.S. firms surveyed over the last year reported they had expanded opportunities to work from home or other remote locations (see chart). Eurofound’s e-survey found employers plan to permit an average of 0.7 days per week at home after the pandemic, although workers, especially women, parents, and those with longer commutes, want 1.7 days.

Days per week of working from home that employers are planning for after the pandemic, as of each survey wave

Source: Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes, Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, 2021. “Why working from home will stick,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. These data are made available under the CC-BY 4.0 license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

There are limits. Researchers Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman have estimated that 37% of jobs in the United States can be performed entirely at home. The Global Survey of Working Arrangements asked full-time workers in 27 countries whether their job could theoretically be done from home. Of the 22% of workers in totally teleworkable jobs, 43% worked exclusively at home already, but of the 28% who said their jobs are partially teleworkable, only 8% were totally homeworking (another 35% worked partially from home).

The downsides of homeworking should not be underestimated, though. It fragments the labor force and impedes teamwork and unionization. It can impose long hours and multi-tasking on employees, as well as parental overload or neglect of children or elders confined to the home. Rather than work flexibility, it can extend the workday and encroach into leisure and family time and space. An April 2022 Conference Board survey found 47% of remote workers in the United States were concerned about the blurred boundaries between their jobs and personal lives. Workers may demand a “right to disconnect.” Indeed, a new law in Portugal bans out-of-hours employer contact, requires employers to contribute to the increase in utility costs linked to working from home, and restricts remote monitoring of workers. At the same time, younger workers may feel cut off from pre-pandemic office life, unable to acquire the social capital and mutual learning needed to get ahead. The surge in loneliness and mental illness resulting from the pandemic lockdowns, social distancing, and greater reliance on social media may also have some home-workers simply pining for the office water cooler.

As the pandemic eases, all these factors will influence the desirability and practice of homework. The traditional separation of public and private spheres may yet reappear.

Hilary Silver is in the sociology department at George Washington University. She has studied paid home work since the 1990s.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Working from Home: Its Effects on Productivity and Mental Health

- Author & abstract

- 22 References

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

- KITAGAWA Ritsu

- KURODA Sachiko

- OKUDAIRA Hiroko

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Working Paper 28731 DOI 10.3386/w28731 Issue Date April 2021. COVID-19 drove a mass social experiment in working from home (WFH). We survey more than 30,000 Americans over multiple waves to investigate whether WFH will stick, and why. ... National Bureau of Economic Research. Contact Us 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 617-868-3900 ...

No 28731, NBER Working Papers from National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Abstract: COVID-19 drove a mass social experiment in working from home (WFH). We survey more than 30,000 Americans over multiple waves to investigate whether WFH will stick, and why. Our data say that 20 percent of full workdays will be supplied from home after the ...

"Why Working from Home Will Stick," NBER Working Papers 28731, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Handle: RePEc:nbr:nberwo:28731 ... Nicholas & Davis, Steven J., 2021. "Why working from home will stick," LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 113912, London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE Library. Barrero, Jose Maria ...

University of Chicago; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); Hoover Institution. Date Written: April 22, 2021. ... Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper Series. Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic FOLLOWERS. 8,333. PAPERS. 966. Economics of Networks eJournal ...

The NBER distributes more than 1,200 Working Papers each year. Papers issued more than 18 months ago are open access. More recent papers are available without charge to affiliates of subscribing academic institutions, employees of NBER Corporate Associates, government employees in the US, journalists, and residents of low-income countries. All ...

Abstract. COVID-19 drove a mass social experiment in working from home (WFH). We survey more than 30,000 Americans over multiple waves to investigate whether WFH will stick, and why. Our data say that 20 percent of full workdays will be supplied from home after the pandemic ends, compared with just 5 percent before.

Why Working from Home Will Stick. COVID-19 drove a mass social experiment in working from home (WFH). We survey more than 30,000 Americans over multiple waves to investigate whether WFH will stick, and why. Our data say that 20 percent of full workdays will be supplied from home after the pandemic ends, compared with just 5 percent before.

We construct industry-level productivity by combining national accounts measures of output by industry from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and all-employee aggregate weekly hours from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). ... "Why Working from Home Will Stick." National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. Updated survey ...

Jose Maria Barrero & Nicholas Bloom & Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why Working from Home Will Stick," NBER Working Papers 28731, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Jose Maria Barrero & Nicholas Bloom & Steven J. Davis, 2020. "Why Working From Home Will Stick," Working Papers 2020-174, Becker Friedman Institute for Research In Economics.

Barrero, Jose, Nicholas Bloom and Steve Davis. "Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 28731, April 2021. Bloom, Nicholas, Paul Mizen and Shivani Taneja. "Returning to the office will be hard," CEPR VOXEU, June 2021. Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts and Zhichun Jenny Ying.

Barrero Jose Maria, Bloom Nicholas, Davis Steven J. 2021. Why working from home will stick. NBER Working Paper No. 28731. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. ... NBER Working Paper No. 27344. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Crossref. Google Scholar. Cameron A. Colin, Miller Douglas L. 2015. A practitioner ...

The Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes (SWAA) is a monthly survey of between 2,500 to 10,000 US residents aged between 20 and 64. ... "Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. All our code and data are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. sign ...

Stanford University - Department of Economics; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Steven J. Davis. University of Chicago; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); Hoover Institution ... The Evolution of Work from Home (September 6, 2023). University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2023-116 ...

Days per week of working from home that employers are planning for after the pandemic, as of each survey wave. Source: Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes, Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731.

Jose Maria Barrero & Nicholas Bloom & Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why Working from Home Will Stick," NBER Working Papers 28731, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Jose Maria Barrero & Nicholas Bloom & Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why working from home will stick," POID Working Papers 011, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

WFH Research | Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes

"Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. However, the majority of workers work fully on site, with less than 15% being able to work only ...

Jose Maria Barrero & Nicholas Bloom & Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why Working from Home Will Stick," NBER Working Papers 28731, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Jose Maria Barrero & Nicholas Bloom & Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why working from home will stick," POID Working Papers 011, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

"Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. www.wfhresearch.com 2. The Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes •Monthly online survey since May 2020, >100,000 observations to date. ... Economic Research Working Paper 28731. 18.

University of Chicago; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); Hoover Institution. Date Written: July 21, 2021. ... Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper Series. Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic FOLLOWERS. 8,328. PAPERS. 973. Feedback. Feedback to SSRN ...