Trending Articles

- Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Lancet. 2024. PMID: 38582094

- Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Shi Q, et al. Lancet. 2024. PMID: 38582569

- Cancer SLC6A6-mediated taurine uptake transactivates immune checkpoint genes and induces exhaustion in CD8 + T cells. Cao T, et al. Cell. 2024. PMID: 38565142

- Infant microbes and metabolites point to childhood neurodevelopmental disorders. Ahrens AP, et al. Cell. 2024. PMID: 38574728

- Gut bacteria-driven homovanillic acid alleviates depression by modulating synaptic integrity. Zhao M, et al. Cell Metab. 2024. PMID: 38582087

Latest Literature

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5)

- Gastroenterology (2)

- J Am Coll Cardiol (7)

- J Clin Endocrinol Metab (4)

- J Exp Med (4)

- J Neurosci (2)

- Nature (16)

- PLoS One (1)

- Pediatrics (2)

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Navigation group

Home banner.

Where scientists empower society

Creating solutions for healthy lives on a healthy planet.

most-cited publisher

largest publisher

2.5 billion

article views and downloads

Main Content

- Editors and reviewers

- Collaborators

Find a journal

We have a home for your research. Our community led journals cover more than 1,500 academic disciplines and are some of the largest and most cited in their fields.

Submit your research

Start your submission and get more impact for your research by publishing with us.

Author guidelines

Ready to publish? Check our author guidelines for everything you need to know about submitting, from choosing a journal and section to preparing your manuscript.

Peer review

Our efficient collaborative peer review means you’ll get a decision on your manuscript in an average of 61 days.

Article publishing charges (APCs) apply to articles that are accepted for publication by our external and independent editorial boards

Press office

Visit our press office for key media contact information, as well as Frontiers’ media kit, including our embargo policy, logos, key facts, leadership bios, and imagery.

Institutional partnerships

Join more than 555 institutions around the world already benefiting from an institutional membership with Frontiers, including CERN, Max Planck Society, and the University of Oxford.

Publishing partnerships

Partner with Frontiers and make your society’s transition to open access a reality with our custom-built platform and publishing expertise.

Policy Labs

Connecting experts from business, science, and policy to strengthen the dialogue between scientific research and informed policymaking.

How we publish

All Frontiers journals are community-run and fully open access, so every research article we publish is immediately and permanently free to read.

Editor guidelines

Reviewing a manuscript? See our guidelines for everything you need to know about our peer review process.

Become an editor

Apply to join an editorial board and collaborate with an international team of carefully selected independent researchers.

My assignments

It’s easy to find and track your editorial assignments with our platform, 'My Frontiers' – saving you time to spend on your own research.

Scientists call for urgent action to prevent immune-mediated illnesses caused by climate change and biodiversity loss

Climate change, pollution, and collapsing biodiversity are damaging our immune systems, but improving the environment offers effective and fast-acting protection.

Safeguarding peer review to ensure quality at scale

Making scientific research open has never been more important. But for research to be trusted, it must be of the highest quality. Facing an industry-wide rise in fraudulent science, Frontiers has increased its focus on safeguarding quality.

Chronic stress and inflammation linked to societal and environmental impacts in new study

Scientists hypothesize that as-yet unrecognized inflammatory stress is spreading among people at unprecedented rates, affecting our cognitive ability to address climate change, war, and other critical issues.

Tiny crustaceans discovered preying on live jellyfish during harsh Arctic night

Scientists used DNA metabarcoding to show for the first time that jellyfish are an important food for amphipods during the Arctic polar night in waters off Svalbard, at a time of year when other food resources are scarce.

Why studying astronauts’ microbiomes is crucial to ensure deep space mission success

In a new Frontiers’ guest editorial, Prof Dr Lembit Sihver, director of CRREAT at the Nuclear Physics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences and his co-authors explore the impact the microbiome has on human health in space.

Cake and cookies may increase Alzheimer’s risk: Here are five Frontiers articles you won’t want to miss

At Frontiers, we bring some of the world’s best research to a global audience. But with tens of thousands of articles published each year, it’s impossible to cover all of them. Here are just five amazing papers you may have missed.

2024's top 10 tech-driven Research Topics

Frontiers has compiled a list of 10 Research Topics that embrace the potential of technology to advance scientific breakthroughs and change the world for the better.

Get the latest research updates, subscribe to our newsletter

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

April 9, 2024

PLOS ONE

An inclusive journal community working together to advance science by making all rigorous research accessible without barriers

Calling all experts!

Plos one is seeking talented individuals to join our editorial board. .

Computational Biology

See Elegans: Simple-to-use, accurate, and automatic 3D detection of neural activity from densely packed neurons

Lanza and collagues presented a novel method (See Elegans) for automatic neuron sementation and tracking in C. elegans.

Image credit: Fig 2 by Lanza et al., CC BY 4.0

Pharmacology

Enhancing radioprotection: A chitosan-based chelating polymer is a versatile radioprotective agent for prophylactic and therapeutic interventions against radionuclide contamination

Durand and colleagues report the evaluation of a functionalized chitosan polymer for treating exposure to radioactive isotopes, including uranium, for which there are no suitable current countermeasures.

Image credit: Radioactive Materials Area by Kerry, CC BY 2.0

Mental Health

Cross-cultural variation in experiences of acceptance, camouflaging and mental health difficulties in autism: A registered report

In this Registered Report, Keating and colleagues explore the relationship between autism acceptance, camoflauging, and mental health in a cross-cultural sample of autistic adults.

Image credit: man-390342_1280 by PDPPics, Pixabay

The double-edged scalpel: Experiences and perceptions of pregnancy and parenthood during Canadian surgical residency training

Peters and colleagues survey female surgical trainees, who report experiencing higher rates of pregnancy complications when compared to non-surgical counterparts, more negative stigma and bias, and other social and logistical challenges. This highlights the need to create a culture where both birthing and non-birthing parents are empowered and supported.

Image credit: woman-1284353_1280 by Pexels, Pixabay

International Day of Women and Girls in Science – Interview with Dr. Swetavalli Raghavan

PLOS ONE Associate Editor Dr Johanna Pruller interviews Dr Swetavalli Raghavan, full professor and founder of Scientists & Co. about mentorship, role models, and the changing landscape for women in science.

Image credit: Dr Swetavalli Raghavan by EveryONE, CC BY 4.0

International Women’s Day – Interview with PLOS ONE Academic Editor Dr. Siaw Shi Boon

PLOS ONE Senior Editor Dr Jianhong Zhou interviews PLOS ONE Academic Editor Dr Siaw Shi Boon about her path to becoming a scientist, challenges facing women in science, and how to encourage more women to become scientists.

Image credit: Dr Siaw Shi Boon by EveryONE, CC BY 4.0

Editor Spotlight: Simon Porcher

In this interview, PLOS ONE Academic Editor Dr Simon Porcher discusses his role as editor, enhancing reproducibility in scientific reporting, and how we can act in future pandemics.

Image credit: Simon Porcher by EveryONE, CC BY 4.0

Child development

Childhood experiences and sleep problems: A cross-sectional study on the indirect relationship mediated by stress, resilience and anxiety

Ashour and colleagues investigate the relationship between childhood experiences and sleep quality in adulthood.

Image credit: Alarm Clock by Congerdesign, Pixabay

Sports and exercise medicine

Responsiveness of respiratory function in Parkinson’s Disease to an integrative exercise programme: A prospective cohort study

McMahon and colleagues report the effectiveness of an exercise intervention on respiratory function.

Image credit: Side view doctor looking at radiography by Freepik, Freepik

The great urban shift: Climate change is predicted to drive mass species turnover in cities

Filazzola and colleagues model how terrestrial wildlife within 60 Canadian and American cities will be affected by climate change.

Image credit: Fig 3 by Filazzola et al., CC BY 4.0

Accessibility

Color Quest: An interactive tool for exploring color palettes and enhancing accessibility in data visualization

Nelli presents an open-source tool for visualizing how various data plots appear to individuals with color blindness, towards improved accessibility.

Image credit: Fig 1 by Nelli et al., CC BY 4.0

Collections

Browse the latest collections of papers from across PLOS.

Watch this space for future collections of papers in PLOS ONE.

Conferences 2024

New opportunities to meet our editorial staff in 2024 will be announced soon.

Publish with PLOS ONE

- Submission Instructions

- Submit Your Manuscript

Connect with Us

- PLOS ONE on Twitter

- PLOS on Facebook

Get new content from PLOS ONE in your inbox

Thank you you have successfully subscribed to the plos one newsletter., sorry, an error occurred while sending your subscription. please try again later..

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2024

Predicting and improving complex beer flavor through machine learning

- Michiel Schreurs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9449-5619 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Supinya Piampongsant 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Miguel Roncoroni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7461-1427 1 , 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Lloyd Cool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9936-3124 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Beatriz Herrera-Malaver ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5096-9974 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Christophe Vanderaa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7443-5427 4 ,

- Florian A. Theßeling 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Łukasz Kreft ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7620-4657 5 ,

- Alexander Botzki ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6691-4233 5 ,

- Philippe Malcorps 6 ,

- Luk Daenen 6 ,

- Tom Wenseleers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1434-861X 4 &

- Kevin J. Verstrepen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3077-6219 1 , 2 , 3

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 2368 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

52k Accesses

856 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Chemical engineering

- Gas chromatography

- Machine learning

- Metabolomics

- Taste receptors

The perception and appreciation of food flavor depends on many interacting chemical compounds and external factors, and therefore proves challenging to understand and predict. Here, we combine extensive chemical and sensory analyses of 250 different beers to train machine learning models that allow predicting flavor and consumer appreciation. For each beer, we measure over 200 chemical properties, perform quantitative descriptive sensory analysis with a trained tasting panel and map data from over 180,000 consumer reviews to train 10 different machine learning models. The best-performing algorithm, Gradient Boosting, yields models that significantly outperform predictions based on conventional statistics and accurately predict complex food features and consumer appreciation from chemical profiles. Model dissection allows identifying specific and unexpected compounds as drivers of beer flavor and appreciation. Adding these compounds results in variants of commercial alcoholic and non-alcoholic beers with improved consumer appreciation. Together, our study reveals how big data and machine learning uncover complex links between food chemistry, flavor and consumer perception, and lays the foundation to develop novel, tailored foods with superior flavors.

Similar content being viewed by others

BitterSweet: Building machine learning models for predicting the bitter and sweet taste of small molecules

Rudraksh Tuwani, Somin Wadhwa & Ganesh Bagler

Sensory lexicon and aroma volatiles analysis of brewing malt

Xiaoxia Su, Miao Yu, … Tianyi Du

Predicting odor from molecular structure: a multi-label classification approach

Kushagra Saini & Venkatnarayan Ramanathan

Introduction

Predicting and understanding food perception and appreciation is one of the major challenges in food science. Accurate modeling of food flavor and appreciation could yield important opportunities for both producers and consumers, including quality control, product fingerprinting, counterfeit detection, spoilage detection, and the development of new products and product combinations (food pairing) 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Accurate models for flavor and consumer appreciation would contribute greatly to our scientific understanding of how humans perceive and appreciate flavor. Moreover, accurate predictive models would also facilitate and standardize existing food assessment methods and could supplement or replace assessments by trained and consumer tasting panels, which are variable, expensive and time-consuming 7 , 8 , 9 . Lastly, apart from providing objective, quantitative, accurate and contextual information that can help producers, models can also guide consumers in understanding their personal preferences 10 .

Despite the myriad of applications, predicting food flavor and appreciation from its chemical properties remains a largely elusive goal in sensory science, especially for complex food and beverages 11 , 12 . A key obstacle is the immense number of flavor-active chemicals underlying food flavor. Flavor compounds can vary widely in chemical structure and concentration, making them technically challenging and labor-intensive to quantify, even in the face of innovations in metabolomics, such as non-targeted metabolic fingerprinting 13 , 14 . Moreover, sensory analysis is perhaps even more complicated. Flavor perception is highly complex, resulting from hundreds of different molecules interacting at the physiochemical and sensorial level. Sensory perception is often non-linear, characterized by complex and concentration-dependent synergistic and antagonistic effects 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 that are further convoluted by the genetics, environment, culture and psychology of consumers 22 , 23 , 24 . Perceived flavor is therefore difficult to measure, with problems of sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility that can only be resolved by gathering sufficiently large datasets 25 . Trained tasting panels are considered the prime source of quality sensory data, but require meticulous training, are low throughput and high cost. Public databases containing consumer reviews of food products could provide a valuable alternative, especially for studying appreciation scores, which do not require formal training 25 . Public databases offer the advantage of amassing large amounts of data, increasing the statistical power to identify potential drivers of appreciation. However, public datasets suffer from biases, including a bias in the volunteers that contribute to the database, as well as confounding factors such as price, cult status and psychological conformity towards previous ratings of the product.

Classical multivariate statistics and machine learning methods have been used to predict flavor of specific compounds by, for example, linking structural properties of a compound to its potential biological activities or linking concentrations of specific compounds to sensory profiles 1 , 26 . Importantly, most previous studies focused on predicting organoleptic properties of single compounds (often based on their chemical structure) 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , thus ignoring the fact that these compounds are present in a complex matrix in food or beverages and excluding complex interactions between compounds. Moreover, the classical statistics commonly used in sensory science 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 require a large sample size and sufficient variance amongst predictors to create accurate models. They are not fit for studying an extensive set of hundreds of interacting flavor compounds, since they are sensitive to outliers, have a high tendency to overfit and are less suited for non-linear and discontinuous relationships 40 .

In this study, we combine extensive chemical analyses and sensory data of a set of different commercial beers with machine learning approaches to develop models that predict taste, smell, mouthfeel and appreciation from compound concentrations. Beer is particularly suited to model the relationship between chemistry, flavor and appreciation. First, beer is a complex product, consisting of thousands of flavor compounds that partake in complex sensory interactions 41 , 42 , 43 . This chemical diversity arises from the raw materials (malt, yeast, hops, water and spices) and biochemical conversions during the brewing process (kilning, mashing, boiling, fermentation, maturation and aging) 44 , 45 . Second, the advent of the internet saw beer consumers embrace online review platforms, such as RateBeer (ZX Ventures, Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV) and BeerAdvocate (Next Glass, inc.). In this way, the beer community provides massive data sets of beer flavor and appreciation scores, creating extraordinarily large sensory databases to complement the analyses of our professional sensory panel. Specifically, we characterize over 200 chemical properties of 250 commercial beers, spread across 22 beer styles, and link these to the descriptive sensory profiling data of a 16-person in-house trained tasting panel and data acquired from over 180,000 public consumer reviews. These unique and extensive datasets enable us to train a suite of machine learning models to predict flavor and appreciation from a beer’s chemical profile. Dissection of the best-performing models allows us to pinpoint specific compounds as potential drivers of beer flavor and appreciation. Follow-up experiments confirm the importance of these compounds and ultimately allow us to significantly improve the flavor and appreciation of selected commercial beers. Together, our study represents a significant step towards understanding complex flavors and reinforces the value of machine learning to develop and refine complex foods. In this way, it represents a stepping stone for further computer-aided food engineering applications 46 .

To generate a comprehensive dataset on beer flavor, we selected 250 commercial Belgian beers across 22 different beer styles (Supplementary Fig. S1 ). Beers with ≤ 4.2% alcohol by volume (ABV) were classified as non-alcoholic and low-alcoholic. Blonds and Tripels constitute a significant portion of the dataset (12.4% and 11.2%, respectively) reflecting their presence on the Belgian beer market and the heterogeneity of beers within these styles. By contrast, lager beers are less diverse and dominated by a handful of brands. Rare styles such as Brut or Faro make up only a small fraction of the dataset (2% and 1%, respectively) because fewer of these beers are produced and because they are dominated by distinct characteristics in terms of flavor and chemical composition.

Extensive analysis identifies relationships between chemical compounds in beer

For each beer, we measured 226 different chemical properties, including common brewing parameters such as alcohol content, iso-alpha acids, pH, sugar concentration 47 , and over 200 flavor compounds (Methods, Supplementary Table S1 ). A large portion (37.2%) are terpenoids arising from hopping, responsible for herbal and fruity flavors 16 , 48 . A second major category are yeast metabolites, such as esters and alcohols, that result in fruity and solvent notes 48 , 49 , 50 . Other measured compounds are primarily derived from malt, or other microbes such as non- Saccharomyces yeasts and bacteria (‘wild flora’). Compounds that arise from spices or staling are labeled under ‘Others’. Five attributes (caloric value, total acids and total ester, hop aroma and sulfur compounds) are calculated from multiple individually measured compounds.

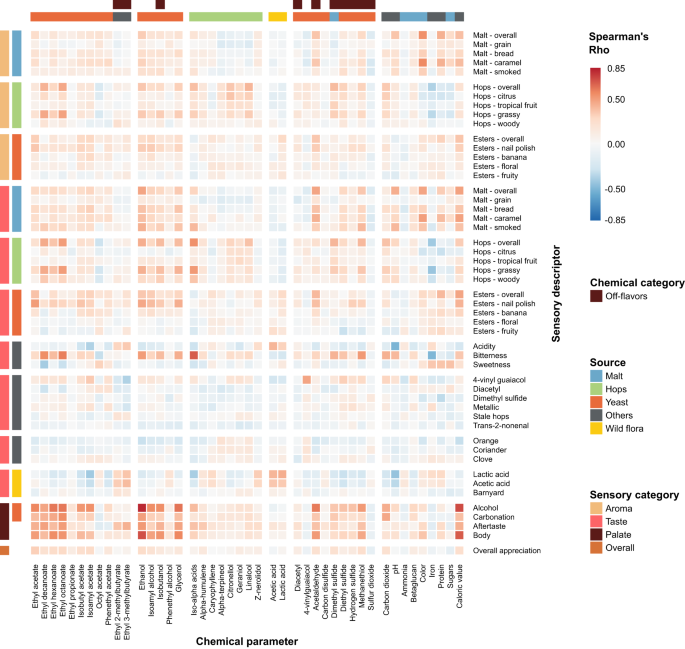

As a first step in identifying relationships between chemical properties, we determined correlations between the concentrations of the compounds (Fig. 1 , upper panel, Supplementary Data 1 and 2 , and Supplementary Fig. S2 . For the sake of clarity, only a subset of the measured compounds is shown in Fig. 1 ). Compounds of the same origin typically show a positive correlation, while absence of correlation hints at parameters varying independently. For example, the hop aroma compounds citronellol, and alpha-terpineol show moderate correlations with each other (Spearman’s rho=0.39 and 0.57), but not with the bittering hop component iso-alpha acids (Spearman’s rho=0.16 and −0.07). This illustrates how brewers can independently modify hop aroma and bitterness by selecting hop varieties and dosage time. If hops are added early in the boiling phase, chemical conversions increase bitterness while aromas evaporate, conversely, late addition of hops preserves aroma but limits bitterness 51 . Similarly, hop-derived iso-alpha acids show a strong anti-correlation with lactic acid and acetic acid, likely reflecting growth inhibition of lactic acid and acetic acid bacteria, or the consequent use of fewer hops in sour beer styles, such as West Flanders ales and Fruit beers, that rely on these bacteria for their distinct flavors 52 . Finally, yeast-derived esters (ethyl acetate, ethyl decanoate, ethyl hexanoate, ethyl octanoate) and alcohols (ethanol, isoamyl alcohol, isobutanol, and glycerol), correlate with Spearman coefficients above 0.5, suggesting that these secondary metabolites are correlated with the yeast genetic background and/or fermentation parameters and may be difficult to influence individually, although the choice of yeast strain may offer some control 53 .

Spearman rank correlations are shown. Descriptors are grouped according to their origin (malt (blue), hops (green), yeast (red), wild flora (yellow), Others (black)), and sensory aspect (aroma, taste, palate, and overall appreciation). Please note that for the chemical compounds, for the sake of clarity, only a subset of the total number of measured compounds is shown, with an emphasis on the key compounds for each source. For more details, see the main text and Methods section. Chemical data can be found in Supplementary Data 1 , correlations between all chemical compounds are depicted in Supplementary Fig. S2 and correlation values can be found in Supplementary Data 2 . See Supplementary Data 4 for sensory panel assessments and Supplementary Data 5 for correlation values between all sensory descriptors.

Interestingly, different beer styles show distinct patterns for some flavor compounds (Supplementary Fig. S3 ). These observations agree with expectations for key beer styles, and serve as a control for our measurements. For instance, Stouts generally show high values for color (darker), while hoppy beers contain elevated levels of iso-alpha acids, compounds associated with bitter hop taste. Acetic and lactic acid are not prevalent in most beers, with notable exceptions such as Kriek, Lambic, Faro, West Flanders ales and Flanders Old Brown, which use acid-producing bacteria ( Lactobacillus and Pediococcus ) or unconventional yeast ( Brettanomyces ) 54 , 55 . Glycerol, ethanol and esters show similar distributions across all beer styles, reflecting their common origin as products of yeast metabolism during fermentation 45 , 53 . Finally, low/no-alcohol beers contain low concentrations of glycerol and esters. This is in line with the production process for most of the low/no-alcohol beers in our dataset, which are produced through limiting fermentation or by stripping away alcohol via evaporation or dialysis, with both methods having the unintended side-effect of reducing the amount of flavor compounds in the final beer 56 , 57 .

Besides expected associations, our data also reveals less trivial associations between beer styles and specific parameters. For example, geraniol and citronellol, two monoterpenoids responsible for citrus, floral and rose flavors and characteristic of Citra hops, are found in relatively high amounts in Christmas, Saison, and Brett/co-fermented beers, where they may originate from terpenoid-rich spices such as coriander seeds instead of hops 58 .

Tasting panel assessments reveal sensorial relationships in beer

To assess the sensory profile of each beer, a trained tasting panel evaluated each of the 250 beers for 50 sensory attributes, including different hop, malt and yeast flavors, off-flavors and spices. Panelists used a tasting sheet (Supplementary Data 3 ) to score the different attributes. Panel consistency was evaluated by repeating 12 samples across different sessions and performing ANOVA. In 95% of cases no significant difference was found across sessions ( p > 0.05), indicating good panel consistency (Supplementary Table S2 ).

Aroma and taste perception reported by the trained panel are often linked (Fig. 1 , bottom left panel and Supplementary Data 4 and 5 ), with high correlations between hops aroma and taste (Spearman’s rho=0.83). Bitter taste was found to correlate with hop aroma and taste in general (Spearman’s rho=0.80 and 0.69), and particularly with “grassy” noble hops (Spearman’s rho=0.75). Barnyard flavor, most often associated with sour beers, is identified together with stale hops (Spearman’s rho=0.97) that are used in these beers. Lactic and acetic acid, which often co-occur, are correlated (Spearman’s rho=0.66). Interestingly, sweetness and bitterness are anti-correlated (Spearman’s rho = −0.48), confirming the hypothesis that they mask each other 59 , 60 . Beer body is highly correlated with alcohol (Spearman’s rho = 0.79), and overall appreciation is found to correlate with multiple aspects that describe beer mouthfeel (alcohol, carbonation; Spearman’s rho= 0.32, 0.39), as well as with hop and ester aroma intensity (Spearman’s rho=0.39 and 0.35).

Similar to the chemical analyses, sensorial analyses confirmed typical features of specific beer styles (Supplementary Fig. S4 ). For example, sour beers (Faro, Flanders Old Brown, Fruit beer, Kriek, Lambic, West Flanders ale) were rated acidic, with flavors of both acetic and lactic acid. Hoppy beers were found to be bitter and showed hop-associated aromas like citrus and tropical fruit. Malt taste is most detected among scotch, stout/porters, and strong ales, while low/no-alcohol beers, which often have a reputation for being ‘worty’ (reminiscent of unfermented, sweet malt extract) appear in the middle. Unsurprisingly, hop aromas are most strongly detected among hoppy beers. Like its chemical counterpart (Supplementary Fig. S3 ), acidity shows a right-skewed distribution, with the most acidic beers being Krieks, Lambics, and West Flanders ales.

Tasting panel assessments of specific flavors correlate with chemical composition

We find that the concentrations of several chemical compounds strongly correlate with specific aroma or taste, as evaluated by the tasting panel (Fig. 2 , Supplementary Fig. S5 , Supplementary Data 6 ). In some cases, these correlations confirm expectations and serve as a useful control for data quality. For example, iso-alpha acids, the bittering compounds in hops, strongly correlate with bitterness (Spearman’s rho=0.68), while ethanol and glycerol correlate with tasters’ perceptions of alcohol and body, the mouthfeel sensation of fullness (Spearman’s rho=0.82/0.62 and 0.72/0.57 respectively) and darker color from roasted malts is a good indication of malt perception (Spearman’s rho=0.54).

Heatmap colors indicate Spearman’s Rho. Axes are organized according to sensory categories (aroma, taste, mouthfeel, overall), chemical categories and chemical sources in beer (malt (blue), hops (green), yeast (red), wild flora (yellow), Others (black)). See Supplementary Data 6 for all correlation values.

Interestingly, for some relationships between chemical compounds and perceived flavor, correlations are weaker than expected. For example, the rose-smelling phenethyl acetate only weakly correlates with floral aroma. This hints at more complex relationships and interactions between compounds and suggests a need for a more complex model than simple correlations. Lastly, we uncovered unexpected correlations. For instance, the esters ethyl decanoate and ethyl octanoate appear to correlate slightly with hop perception and bitterness, possibly due to their fruity flavor. Iron is anti-correlated with hop aromas and bitterness, most likely because it is also anti-correlated with iso-alpha acids. This could be a sign of metal chelation of hop acids 61 , given that our analyses measure unbound hop acids and total iron content, or could result from the higher iron content in dark and Fruit beers, which typically have less hoppy and bitter flavors 62 .

Public consumer reviews complement expert panel data

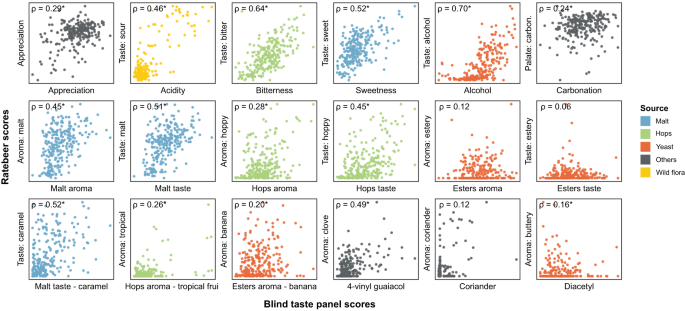

To complement and expand the sensory data of our trained tasting panel, we collected 180,000 reviews of our 250 beers from the online consumer review platform RateBeer. This provided numerical scores for beer appearance, aroma, taste, palate, overall quality as well as the average overall score.

Public datasets are known to suffer from biases, such as price, cult status and psychological conformity towards previous ratings of a product. For example, prices correlate with appreciation scores for these online consumer reviews (rho=0.49, Supplementary Fig. S6 ), but not for our trained tasting panel (rho=0.19). This suggests that prices affect consumer appreciation, which has been reported in wine 63 , while blind tastings are unaffected. Moreover, we observe that some beer styles, like lagers and non-alcoholic beers, generally receive lower scores, reflecting that online reviewers are mostly beer aficionados with a preference for specialty beers over lager beers. In general, we find a modest correlation between our trained panel’s overall appreciation score and the online consumer appreciation scores (Fig. 3 , rho=0.29). Apart from the aforementioned biases in the online datasets, serving temperature, sample freshness and surroundings, which are all tightly controlled during the tasting panel sessions, can vary tremendously across online consumers and can further contribute to (among others, appreciation) differences between the two categories of tasters. Importantly, in contrast to the overall appreciation scores, for many sensory aspects the results from the professional panel correlated well with results obtained from RateBeer reviews. Correlations were highest for features that are relatively easy to recognize even for untrained tasters, like bitterness, sweetness, alcohol and malt aroma (Fig. 3 and below).

RateBeer text mining results can be found in Supplementary Data 7 . Rho values shown are Spearman correlation values, with asterisks indicating significant correlations ( p < 0.05, two-sided). All p values were smaller than 0.001, except for Esters aroma (0.0553), Esters taste (0.3275), Esters aroma—banana (0.0019), Coriander (0.0508) and Diacetyl (0.0134).

Besides collecting consumer appreciation from these online reviews, we developed automated text analysis tools to gather additional data from review texts (Supplementary Data 7 ). Processing review texts on the RateBeer database yielded comparable results to the scores given by the trained panel for many common sensory aspects, including acidity, bitterness, sweetness, alcohol, malt, and hop tastes (Fig. 3 ). This is in line with what would be expected, since these attributes require less training for accurate assessment and are less influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, serving glass and odors in the environment. Consumer reviews also correlate well with our trained panel for 4-vinyl guaiacol, a compound associated with a very characteristic aroma. By contrast, correlations for more specific aromas like ester, coriander or diacetyl are underrepresented in the online reviews, underscoring the importance of using a trained tasting panel and standardized tasting sheets with explicit factors to be scored for evaluating specific aspects of a beer. Taken together, our results suggest that public reviews are trustworthy for some, but not all, flavor features and can complement or substitute taste panel data for these sensory aspects.

Models can predict beer sensory profiles from chemical data

The rich datasets of chemical analyses, tasting panel assessments and public reviews gathered in the first part of this study provided us with a unique opportunity to develop predictive models that link chemical data to sensorial features. Given the complexity of beer flavor, basic statistical tools such as correlations or linear regression may not always be the most suitable for making accurate predictions. Instead, we applied different machine learning models that can model both simple linear and complex interactive relationships. Specifically, we constructed a set of regression models to predict (a) trained panel scores for beer flavor and quality and (b) public reviews’ appreciation scores from beer chemical profiles. We trained and tested 10 different models (Methods), 3 linear regression-based models (simple linear regression with first-order interactions (LR), lasso regression with first-order interactions (Lasso), partial least squares regressor (PLSR)), 5 decision tree models (AdaBoost regressor (ABR), extra trees (ET), gradient boosting regressor (GBR), random forest (RF) and XGBoost regressor (XGBR)), 1 support vector regression (SVR), and 1 artificial neural network (ANN) model.

To compare the performance of our machine learning models, the dataset was randomly split into a training and test set, stratified by beer style. After a model was trained on data in the training set, its performance was evaluated on its ability to predict the test dataset obtained from multi-output models (based on the coefficient of determination, see Methods). Additionally, individual-attribute models were ranked per descriptor and the average rank was calculated, as proposed by Korneva et al. 64 . Importantly, both ways of evaluating the models’ performance agreed in general. Performance of the different models varied (Table 1 ). It should be noted that all models perform better at predicting RateBeer results than results from our trained tasting panel. One reason could be that sensory data is inherently variable, and this variability is averaged out with the large number of public reviews from RateBeer. Additionally, all tree-based models perform better at predicting taste than aroma. Linear models (LR) performed particularly poorly, with negative R 2 values, due to severe overfitting (training set R 2 = 1). Overfitting is a common issue in linear models with many parameters and limited samples, especially with interaction terms further amplifying the number of parameters. L1 regularization (Lasso) successfully overcomes this overfitting, out-competing multiple tree-based models on the RateBeer dataset. Similarly, the dimensionality reduction of PLSR avoids overfitting and improves performance, to some extent. Still, tree-based models (ABR, ET, GBR, RF and XGBR) show the best performance, out-competing the linear models (LR, Lasso, PLSR) commonly used in sensory science 65 .

GBR models showed the best overall performance in predicting sensory responses from chemical information, with R 2 values up to 0.75 depending on the predicted sensory feature (Supplementary Table S4 ). The GBR models predict consumer appreciation (RateBeer) better than our trained panel’s appreciation (R 2 value of 0.67 compared to R 2 value of 0.09) (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Table S4 ). ANN models showed intermediate performance, likely because neural networks typically perform best with larger datasets 66 . The SVR shows intermediate performance, mostly due to the weak predictions of specific attributes that lower the overall performance (Supplementary Table S4 ).

Model dissection identifies specific, unexpected compounds as drivers of consumer appreciation

Next, we leveraged our models to infer important contributors to sensory perception and consumer appreciation. Consumer preference is a crucial sensory aspects, because a product that shows low consumer appreciation scores often does not succeed commercially 25 . Additionally, the requirement for a large number of representative evaluators makes consumer trials one of the more costly and time-consuming aspects of product development. Hence, a model for predicting chemical drivers of overall appreciation would be a welcome addition to the available toolbox for food development and optimization.

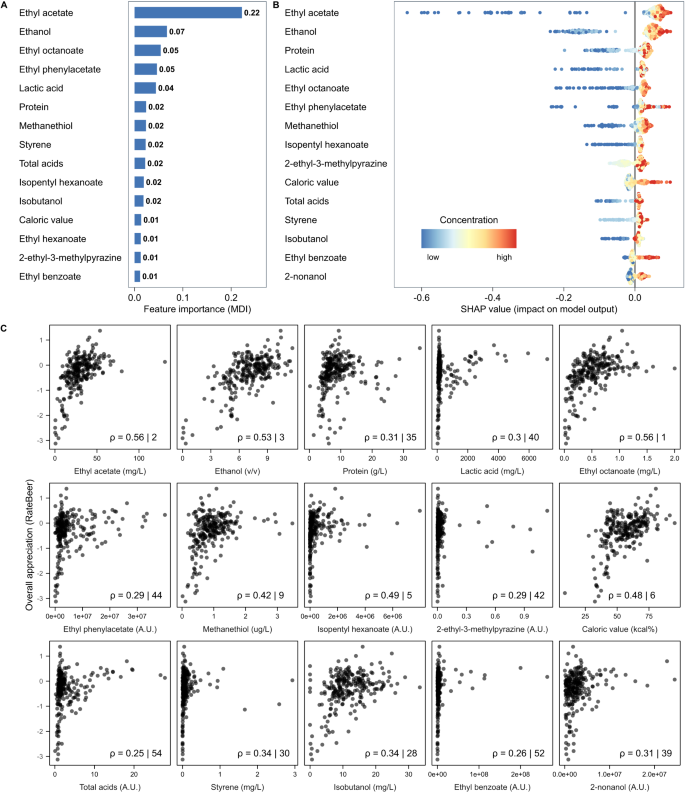

Since GBR models on our RateBeer dataset showed the best overall performance, we focused on these models. Specifically, we used two approaches to identify important contributors. First, rankings of the most important predictors for each sensorial trait in the GBR models were obtained based on impurity-based feature importance (mean decrease in impurity). High-ranked parameters were hypothesized to be either the true causal chemical properties underlying the trait, to correlate with the actual causal properties, or to take part in sensory interactions affecting the trait 67 (Fig. 4A ). In a second approach, we used SHAP 68 to determine which parameters contributed most to the model for making predictions of consumer appreciation (Fig. 4B ). SHAP calculates parameter contributions to model predictions on a per-sample basis, which can be aggregated into an importance score.

A The impurity-based feature importance (mean deviance in impurity, MDI) calculated from the Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR) model predicting RateBeer appreciation scores. The top 15 highest ranked chemical properties are shown. B SHAP summary plot for the top 15 parameters contributing to our GBR model. Each point on the graph represents a sample from our dataset. The color represents the concentration of that parameter, with bluer colors representing low values and redder colors representing higher values. Greater absolute values on the horizontal axis indicate a higher impact of the parameter on the prediction of the model. C Spearman correlations between the 15 most important chemical properties and consumer overall appreciation. Numbers indicate the Spearman Rho correlation coefficient, and the rank of this correlation compared to all other correlations. The top 15 important compounds were determined using SHAP (panel B).

Both approaches identified ethyl acetate as the most predictive parameter for beer appreciation (Fig. 4 ). Ethyl acetate is the most abundant ester in beer with a typical ‘fruity’, ‘solvent’ and ‘alcoholic’ flavor, but is often considered less important than other esters like isoamyl acetate. The second most important parameter identified by SHAP is ethanol, the most abundant beer compound after water. Apart from directly contributing to beer flavor and mouthfeel, ethanol drastically influences the physical properties of beer, dictating how easily volatile compounds escape the beer matrix to contribute to beer aroma 69 . Importantly, it should also be noted that the importance of ethanol for appreciation is likely inflated by the very low appreciation scores of non-alcoholic beers (Supplementary Fig. S4 ). Despite not often being considered a driver of beer appreciation, protein level also ranks highly in both approaches, possibly due to its effect on mouthfeel and body 70 . Lactic acid, which contributes to the tart taste of sour beers, is the fourth most important parameter identified by SHAP, possibly due to the generally high appreciation of sour beers in our dataset.

Interestingly, some of the most important predictive parameters for our model are not well-established as beer flavors or are even commonly regarded as being negative for beer quality. For example, our models identify methanethiol and ethyl phenyl acetate, an ester commonly linked to beer staling 71 , as a key factor contributing to beer appreciation. Although there is no doubt that high concentrations of these compounds are considered unpleasant, the positive effects of modest concentrations are not yet known 72 , 73 .

To compare our approach to conventional statistics, we evaluated how well the 15 most important SHAP-derived parameters correlate with consumer appreciation (Fig. 4C ). Interestingly, only 6 of the properties derived by SHAP rank amongst the top 15 most correlated parameters. For some chemical compounds, the correlations are so low that they would have likely been considered unimportant. For example, lactic acid, the fourth most important parameter, shows a bimodal distribution for appreciation, with sour beers forming a separate cluster, that is missed entirely by the Spearman correlation. Additionally, the correlation plots reveal outliers, emphasizing the need for robust analysis tools. Together, this highlights the need for alternative models, like the Gradient Boosting model, that better grasp the complexity of (beer) flavor.

Finally, to observe the relationships between these chemical properties and their predicted targets, partial dependence plots were constructed for the six most important predictors of consumer appreciation 74 , 75 , 76 (Supplementary Fig. S7 ). One-way partial dependence plots show how a change in concentration affects the predicted appreciation. These plots reveal an important limitation of our models: appreciation predictions remain constant at ever-increasing concentrations. This implies that once a threshold concentration is reached, further increasing the concentration does not affect appreciation. This is false, as it is well-documented that certain compounds become unpleasant at high concentrations, including ethyl acetate (‘nail polish’) 77 and methanethiol (‘sulfury’ and ‘rotten cabbage’) 78 . The inability of our models to grasp that flavor compounds have optimal levels, above which they become negative, is a consequence of working with commercial beer brands where (off-)flavors are rarely too high to negatively impact the product. The two-way partial dependence plots show how changing the concentration of two compounds influences predicted appreciation, visualizing their interactions (Supplementary Fig. S7 ). In our case, the top 5 parameters are dominated by additive or synergistic interactions, with high concentrations for both compounds resulting in the highest predicted appreciation.

To assess the robustness of our best-performing models and model predictions, we performed 100 iterations of the GBR, RF and ET models. In general, all iterations of the models yielded similar performance (Supplementary Fig. S8 ). Moreover, the main predictors (including the top predictors ethanol and ethyl acetate) remained virtually the same, especially for GBR and RF. For the iterations of the ET model, we did observe more variation in the top predictors, which is likely a consequence of the model’s inherent random architecture in combination with co-correlations between certain predictors. However, even in this case, several of the top predictors (ethanol and ethyl acetate) remain unchanged, although their rank in importance changes (Supplementary Fig. S8 ).

Next, we investigated if a combination of RateBeer and trained panel data into one consolidated dataset would lead to stronger models, under the hypothesis that such a model would suffer less from bias in the datasets. A GBR model was trained to predict appreciation on the combined dataset. This model underperformed compared to the RateBeer model, both in the native case and when including a dataset identifier (R 2 = 0.67, 0.26 and 0.42 respectively). For the latter, the dataset identifier is the most important feature (Supplementary Fig. S9 ), while most of the feature importance remains unchanged, with ethyl acetate and ethanol ranking highest, like in the original model trained only on RateBeer data. It seems that the large variation in the panel dataset introduces noise, weakening the models’ performances and reliability. In addition, it seems reasonable to assume that both datasets are fundamentally different, with the panel dataset obtained by blind tastings by a trained professional panel.

Lastly, we evaluated whether beer style identifiers would further enhance the model’s performance. A GBR model was trained with parameters that explicitly encoded the styles of the samples. This did not improve model performance (R2 = 0.66 with style information vs R2 = 0.67). The most important chemical features are consistent with the model trained without style information (eg. ethanol and ethyl acetate), and with the exception of the most preferred (strong ale) and least preferred (low/no-alcohol) styles, none of the styles were among the most important features (Supplementary Fig. S9 , Supplementary Table S5 and S6 ). This is likely due to a combination of style-specific chemical signatures, such as iso-alpha acids and lactic acid, that implicitly convey style information to the original models, as well as the low number of samples belonging to some styles, making it difficult for the model to learn style-specific patterns. Moreover, beer styles are not rigorously defined, with some styles overlapping in features and some beers being misattributed to a specific style, all of which leads to more noise in models that use style parameters.

Model validation

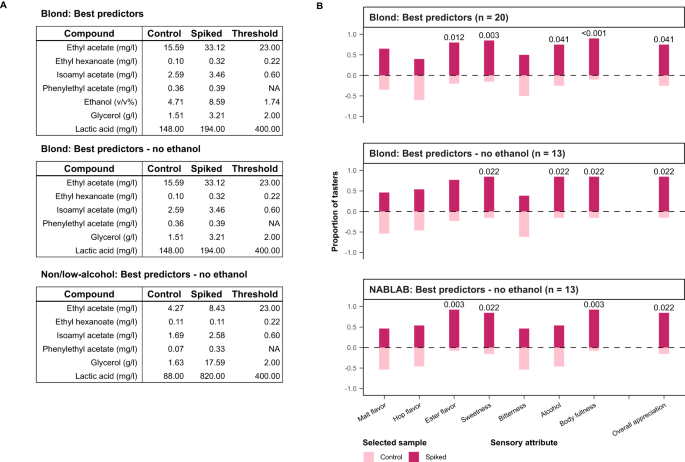

To test if our predictive models give insight into beer appreciation, we set up experiments aimed at improving existing commercial beers. We specifically selected overall appreciation as the trait to be examined because of its complexity and commercial relevance. Beer flavor comprises a complex bouquet rather than single aromas and tastes 53 . Hence, adding a single compound to the extent that a difference is noticeable may lead to an unbalanced, artificial flavor. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of combinations of compounds. Because Blond beers represent the most extensive style in our dataset, we selected a beer from this style as the starting material for these experiments (Beer 64 in Supplementary Data 1 ).

In the first set of experiments, we adjusted the concentrations of compounds that made up the most important predictors of overall appreciation (ethyl acetate, ethanol, lactic acid, ethyl phenyl acetate) together with correlated compounds (ethyl hexanoate, isoamyl acetate, glycerol), bringing them up to 95 th percentile ethanol-normalized concentrations (Methods) within the Blond group (‘Spiked’ concentration in Fig. 5A ). Compared to controls, the spiked beers were found to have significantly improved overall appreciation among trained panelists, with panelist noting increased intensity of ester flavors, sweetness, alcohol, and body fullness (Fig. 5B ). To disentangle the contribution of ethanol to these results, a second experiment was performed without the addition of ethanol. This resulted in a similar outcome, including increased perception of alcohol and overall appreciation.

Adding the top chemical compounds, identified as best predictors of appreciation by our model, into poorly appreciated beers results in increased appreciation from our trained panel. Results of sensory tests between base beers and those spiked with compounds identified as the best predictors by the model. A Blond and Non/Low-alcohol (0.0% ABV) base beers were brought up to 95th-percentile ethanol-normalized concentrations within each style. B For each sensory attribute, tasters indicated the more intense sample and selected the sample they preferred. The numbers above the bars correspond to the p values that indicate significant changes in perceived flavor (two-sided binomial test: alpha 0.05, n = 20 or 13).

In a last experiment, we tested whether using the model’s predictions can boost the appreciation of a non-alcoholic beer (beer 223 in Supplementary Data 1 ). Again, the addition of a mixture of predicted compounds (omitting ethanol, in this case) resulted in a significant increase in appreciation, body, ester flavor and sweetness.

Predicting flavor and consumer appreciation from chemical composition is one of the ultimate goals of sensory science. A reliable, systematic and unbiased way to link chemical profiles to flavor and food appreciation would be a significant asset to the food and beverage industry. Such tools would substantially aid in quality control and recipe development, offer an efficient and cost-effective alternative to pilot studies and consumer trials and would ultimately allow food manufacturers to produce superior, tailor-made products that better meet the demands of specific consumer groups more efficiently.

A limited set of studies have previously tried, to varying degrees of success, to predict beer flavor and beer popularity based on (a limited set of) chemical compounds and flavors 79 , 80 . Current sensitive, high-throughput technologies allow measuring an unprecedented number of chemical compounds and properties in a large set of samples, yielding a dataset that can train models that help close the gaps between chemistry and flavor, even for a complex natural product like beer. To our knowledge, no previous research gathered data at this scale (250 samples, 226 chemical parameters, 50 sensory attributes and 5 consumer scores) to disentangle and validate the chemical aspects driving beer preference using various machine-learning techniques. We find that modern machine learning models outperform conventional statistical tools, such as correlations and linear models, and can successfully predict flavor appreciation from chemical composition. This could be attributed to the natural incorporation of interactions and non-linear or discontinuous effects in machine learning models, which are not easily grasped by the linear model architecture. While linear models and partial least squares regression represent the most widespread statistical approaches in sensory science, in part because they allow interpretation 65 , 81 , 82 , modern machine learning methods allow for building better predictive models while preserving the possibility to dissect and exploit the underlying patterns. Of the 10 different models we trained, tree-based models, such as our best performing GBR, showed the best overall performance in predicting sensory responses from chemical information, outcompeting artificial neural networks. This agrees with previous reports for models trained on tabular data 83 . Our results are in line with the findings of Colantonio et al. who also identified the gradient boosting architecture as performing best at predicting appreciation and flavor (of tomatoes and blueberries, in their specific study) 26 . Importantly, besides our larger experimental scale, we were able to directly confirm our models’ predictions in vivo.

Our study confirms that flavor compound concentration does not always correlate with perception, suggesting complex interactions that are often missed by more conventional statistics and simple models. Specifically, we find that tree-based algorithms may perform best in developing models that link complex food chemistry with aroma. Furthermore, we show that massive datasets of untrained consumer reviews provide a valuable source of data, that can complement or even replace trained tasting panels, especially for appreciation and basic flavors, such as sweetness and bitterness. This holds despite biases that are known to occur in such datasets, such as price or conformity bias. Moreover, GBR models predict taste better than aroma. This is likely because taste (e.g. bitterness) often directly relates to the corresponding chemical measurements (e.g., iso-alpha acids), whereas such a link is less clear for aromas, which often result from the interplay between multiple volatile compounds. We also find that our models are best at predicting acidity and alcohol, likely because there is a direct relation between the measured chemical compounds (acids and ethanol) and the corresponding perceived sensorial attribute (acidity and alcohol), and because even untrained consumers are generally able to recognize these flavors and aromas.

The predictions of our final models, trained on review data, hold even for blind tastings with small groups of trained tasters, as demonstrated by our ability to validate specific compounds as drivers of beer flavor and appreciation. Since adding a single compound to the extent of a noticeable difference may result in an unbalanced flavor profile, we specifically tested our identified key drivers as a combination of compounds. While this approach does not allow us to validate if a particular single compound would affect flavor and/or appreciation, our experiments do show that this combination of compounds increases consumer appreciation.

It is important to stress that, while it represents an important step forward, our approach still has several major limitations. A key weakness of the GBR model architecture is that amongst co-correlating variables, the largest main effect is consistently preferred for model building. As a result, co-correlating variables often have artificially low importance scores, both for impurity and SHAP-based methods, like we observed in the comparison to the more randomized Extra Trees models. This implies that chemicals identified as key drivers of a specific sensory feature by GBR might not be the true causative compounds, but rather co-correlate with the actual causative chemical. For example, the high importance of ethyl acetate could be (partially) attributed to the total ester content, ethanol or ethyl hexanoate (rho=0.77, rho=0.72 and rho=0.68), while ethyl phenylacetate could hide the importance of prenyl isobutyrate and ethyl benzoate (rho=0.77 and rho=0.76). Expanding our GBR model to include beer style as a parameter did not yield additional power or insight. This is likely due to style-specific chemical signatures, such as iso-alpha acids and lactic acid, that implicitly convey style information to the original model, as well as the smaller sample size per style, limiting the power to uncover style-specific patterns. This can be partly attributed to the curse of dimensionality, where the high number of parameters results in the models mainly incorporating single parameter effects, rather than complex interactions such as style-dependent effects 67 . A larger number of samples may overcome some of these limitations and offer more insight into style-specific effects. On the other hand, beer style is not a rigid scientific classification, and beers within one style often differ a lot, which further complicates the analysis of style as a model factor.

Our study is limited to beers from Belgian breweries. Although these beers cover a large portion of the beer styles available globally, some beer styles and consumer patterns may be missing, while other features might be overrepresented. For example, many Belgian ales exhibit yeast-driven flavor profiles, which is reflected in the chemical drivers of appreciation discovered by this study. In future work, expanding the scope to include diverse markets and beer styles could lead to the identification of even more drivers of appreciation and better models for special niche products that were not present in our beer set.

In addition to inherent limitations of GBR models, there are also some limitations associated with studying food aroma. Even if our chemical analyses measured most of the known aroma compounds, the total number of flavor compounds in complex foods like beer is still larger than the subset we were able to measure in this study. For example, hop-derived thiols, that influence flavor at very low concentrations, are notoriously difficult to measure in a high-throughput experiment. Moreover, consumer perception remains subjective and prone to biases that are difficult to avoid. It is also important to stress that the models are still immature and that more extensive datasets will be crucial for developing more complete models in the future. Besides more samples and parameters, our dataset does not include any demographic information about the tasters. Including such data could lead to better models that grasp external factors like age and culture. Another limitation is that our set of beers consists of high-quality end-products and lacks beers that are unfit for sale, which limits the current model in accurately predicting products that are appreciated very badly. Finally, while models could be readily applied in quality control, their use in sensory science and product development is restrained by their inability to discern causal relationships. Given that the models cannot distinguish compounds that genuinely drive consumer perception from those that merely correlate, validation experiments are essential to identify true causative compounds.