- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: Assignment- Narrative Essay—Prewriting and Drafting

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58194

- Lumen Learning

For this assignment, you will begin working on a narrative essay. At this stage, you will work through the prewriting and drafting steps of the writing process.

Narrative Essay Prompt

Choose one of the following topics to write your own narrative essay. The topic you decide on should be something you care about, and the narration should be a means of communicating an idea that ties to the essay’s theme. Remember in this essay, the narration is not an end in itself.

- Gaining independence

- A friend’s sacrifice

- A significant trip with your family

- A wedding or a funeral

- An incident from family legend

The World Around You

- A storm, a flood, an earthquake, or another natural event

- A school event

- The most important minutes of a sporting event

Lessons of Daily Life

- A time you confronted authority

- A time you had to deliver bad news

- Your biggest social blunder

- Your first day of school

- The first performance you gave

- A first date

Getting Started on Your Narrative Essay

STEP 1 : To get started writing, first pick at least one prewriting strategy (brainstorming, rewriting, journaling, mapping, questioning, sketching) to develop ideas for your essay. Write down what you do, as you’ll need to submit evidence of your prewrite.

Remember that “story starters” are everywhere. Think about it—status updates on social media websites can be a good place to start—you may have already started a “note” to post on social media, and now is your chance to develop that idea into a full narrative. If you keep a journal or diary, a simple event may unfold into a narrative. Simply said, your stories may be closer than you think!

STEP 2: Next, write an outline for your essay. Organize the essay in a way that:

- Establishes the situation [introduction] ;

- Introduces the complication(s) [body] ; and

- States the lesson you learned [conclusion]

STEP 3: Lastly, write a first draft of your essay. Remember, When drafting your essay:

- Develop an enticing title—but don’t let yourself get stuck on the title! A great title might suggest itself after you’ve begun the prewriting and drafting processes.

- Use the introduction to establish the situation the essay will address.

- Avoid addressing the assignment directly. (For example, don’t write “I am going to write about my most significant experience,” because this takes the fun out of reading the work!)

- Think of things said at the moment this experience started for you—perhaps use a quote, or an interesting part of the experience that will grab the reader.

- Let the story reflect your own voice. (Is your voice serious? Humorous? Matter-of-fact?)

- To avoid just telling what happens, make sure your essay takes time to reflect on why this experience is significant.

Assignment Instructions

- Choose a writing prompt as listed above on this page.

- Review the grading rubric as listed below this page.

- Create a prewrite in the style of your choice for the prompt.

- Create an outline for your essay.

- Minimum of 3 typed, double-spaced pages (about 600–750 words), Times New Roman, 12 pt font size

- MLA formatting

- Submit your prewriting and draft as a single file upload.

Requirements

Be sure to:

- Decide on something you care about so that the narration is a means of communicating an idea.

- Include characters, conflict, sensory details.

- Create a sequence of events in a plot.

- Develop an enticing title.

- Use the introduction to pull the reader into your singular experience.

- Avoid addressing the assignment directly. (don’t write “I am going to write about…”—this takes the fun out of reading the work!)

- Let the essay reflect your own voice (Is your voice serious? Humorous? Matter-of-fact?)

- Avoid telling just what happens by making sure your essay reflects on why this experience is significant.

If you developed your prewriting by hand on paper, scan or take a picture of your prewriting, load the image onto your computer, and then insert the image on a separate page after your draft.

Contributors and Attributions

- Authored by : Daryl Smith O' Hare and Susan C. Hines. Provided by : Chadron State College. Project : Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Organization

- Paragraph Types

- Timed Writing (Expectations)

- The Writing Process

- Writing Skill: Development

- Timed Writing (The Prompt)

- Integrated Writing (Writing Process)

- Narrative Writing

- Example Narrative Writing #1

- Writing Skill: Unity

- Example Narrative Writing #2

- Timed Writing (Choose a Position)

- Integrated Writing (TOEFL Task 1)

- Descriptive Writing

- Example Descriptive Writing #1

- Writing Skill: Cohesion

- Example Descriptive Writing #2

- Timed Writing (Plans & Problems)

- Integrated Writing (TOEFL Task 2)

- Introduction to Essays

- Introduction Paragraphs

- Conclusion Paragraphs

- Example Essay

- Body Paragraphs

- Personal Experience Essay

- Example Essay #1

- Writing Skill: Summary

- Timed Writing (Revising)

- Integrated Writing (Summary)

- More Writing Skills

- Punctuation & Capitalization

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences Part 1

- Teachers' Guide

- Teacher Notes

- Activity Ideas

- Translations

Choose a Sign-in Option

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

Understand the assignment

What is a narrative? The purpose of a narrative is to tell a story or to share an experience. The events in a narrative are usually told in chronological (time) order. Narratives use words that show time, like "after", "next", and "then." For a narrative to be complete, it should include all parts of a story.

Brainstorm to find a topic

Think about an event that was memorable for you. It could be a very happy event, an event that taught you something important, a time you were surprised, or another important day or event. Don't choose an event that is too big. For example, don't write about your entire last year of high school or a family member being ill for ten years. There will be too many things to write about for this assignment. Instead, choose a smaller event, like your first day of college or the time you won an award.

Example Topics

- A life-changing experience

- The first time I ...

- The happiest day of ...

- Overcoming an obstacle

- How I met my best friend

Choose a focus

If the experience is very long, you may need to focus on a more specific part of the story (e.g., "My first day at the ELC" instead of "My first semester at the ELC".). Do not choose a story that is too long or complicated. Think about the part of the story that is most interesting, important, or memorable.

Brainstorm for details

Once you have your topic chosen, think about the event or experience in as much detail as possible.

- Why was the event memorable?

- Where were you?

- Who was there?

- What did you see?

- What did you smell?

- What did you hear?

- How did you feel?

- Did you change? Why or why not? How?

Just like all writing, a narrative needs an introduction, supporting ideas (major details), and a conclusion.

Once you write your topic sentence, organize your story by the order of events or by another type of organization. There are many ways you can do that. Look at basic example outlines.

Example: Paragraph Outline #1

TS: The week of midterm exams was the most stressful week of my first semester of college.

SS: The week of midterms was stressful because I had six different tests to take.

- What were the tests?

- Why did I need to take them?

- Why were the tests stressful?

- How did I do on the tests?

- How did I prepare?

SS: The week of midterms was stressful because it was also the week of cleaning checks.

- What are cleaning checks?

- Why did we have them that week?

- Who else helped with the cleaning checks?

- Why did this add more stress to my life?

- How did I manage my stress?

C: I struggled with a lot of stress during my first midterm exam experience.

Example: Paragraph Outline #2

TS: My worst piano performance taught me a very valuable lesson.

SS: It was my worst performance ever.

- What happened?

- When was this?

- Where was the performance?

- Why was it so bad?

SS: I learned the value of having confidence.

- How did this teach me confidence?

- What were my experiences after like?

- Who helped me feel more confident?

- Was this a lesson you only learned for piano? Or did it impact you in other ways?

C: I learned how important confidence was from my worst performance ever.

Introduction

The introduction for a narrative should provide important information that readers need to know in order to understand the story that you will tell. These are the setting (place and time), the characters (people), and any other details readers need to understand your story (e.g., why you were there, or explaining what the event was). Your introduction may also include a hook —a sentence or question that catches readers' interest and makes them want to continue reading.

In a narrative paragraph, your introduction might be just one or two sentences: a topic sentence and maybe a hook, too. These will be at the beginning of your paragraph.

In a narrative essay, your introduction should be an entire paragraph. Usually, the introduction paragraph starts with a hook. Your thesis, or the sentence that tells the reader why the narrative is important (e.g., "The day I graduated from high school was the happiest day of my life."), might be right after the hook, with the other background information after it. Or, you might put the thesis at the end of the introduction paragraph, with the background information before it. Either way can be okay.

The body of a narrative contains the plot (the sequence of events, or what happens in the story). Divide your story up into major events and tell about each event in each of your supporting sentences. Each event you choose should support the thesis of your narrative.

The conclusion should tell how the story ended and re-emphasize the importance of the story. It should start by summarizing your main idea and end with a closing statement that in some way makes a prediction, suggestion, or opinion.

Exercise 1: Brainstorm for a topic

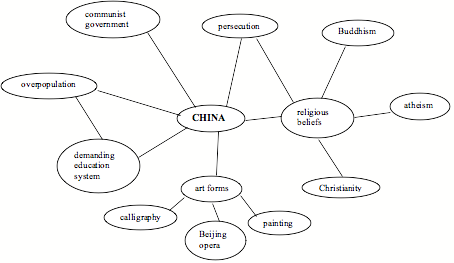

Think about some of the most memorable events in your life. Use the map below to complete a brainstorm activity.

Exercise 2: Brainstorm for details

Spend five minutes answering the questions in the Brainstorming section above.

This will help make the memory vivid in your mind. If you do not have a vivid memory, you will not be able to paint a clear picture for your reader. It's okay to start writing in short (or even incomplete) sentences

- Went to beach alone

- Felt peaceful

- Heard the waves

Exercise 3: Write your thesis

After choosing a topic and focus for your narrative, start outlining by thinking about why the event you chose is important. Use that information to write your thesis.

- The week of midterm exams was the most stressful week of my first semester of college.

- My graduation day was one of the most exciting days of my life.

- The most unforgettable experience was going skydiving.

- My worst piano performance taught me a very valuable lesson.

Your Thesis: ___________________________________________________

Exercise 4: Make an outline

Start your outline with your thesis sentence and your topic sentence.

You can add the other details after your outline is approved.

This content is provided to you freely by BYU Open Learning Network.

Access it online or download it at https://open.byu.edu/foundations_c_writing/prewritingW .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

An Overview of Academic Writing, Planning, and Prewriting

It can be tempting to dive into an essay immediately without taking the time to really think through what you are writing about and why you might be doing so. This can lead to essays that lack coherence and veer off topic, and not having an organized prewriting process can also create quite a bit of stress for the writer. The quality of writing without prewriting is often inconsistent, as the writer becomes trapped in simply writing and hoping that their initial instincts have set them on the correct course. As you move into your professional life, you will need to adopt a writing process that is consistent, creates effective papers, and, perhaps most importantly, minimizes the stress and anxiety that can come along with any writing endeavor.

Prewriting activities might be intimidating, especially if you have never spent much time on them in the past. However, an effective prewriting process, while perhaps requiring some additional time at the outset, will save you quite a bit of time and stress in the long run. The ideas covered in this chapter will help you map out your paper and consider how your intended audience might affect its structure, tone, and content. In doing so, it will help you escape the “writing and hoping” trap.

We Will Begin Our Journey By Exploring Basic Prewriting Concepts

Read through the following content on effective prewriting strategies, which has been adapted from Ann Inoshita, et al ‘s English Composition: Connect, Collaborate, Communicate. As you do so, try employing some of the strategies to plan out your papers for this course and beyond!

Prewriting is an essential activity for most writers. Through robust prewriting, writers generate ideas, explore directions, and find their way into their writing. When students attempt to write an essay without developing their ideas, strategizing their desired structure, and focusing on precision with words and phrases, they can end up with a “premature draft”—one that is more writer-based than reader-based and, thus, might not be received by readers in the way the writer intended.

In addition, a lack of prewriting can cause students to experience writer’s block. Writer’s block is the feeling of being stuck when faced with a writing task. It is often caused by fear, anxiety, or a tendency toward perfectionism, but it can be overcome through prewriting activities that allow writers to relax, catch their breath, gather ideas, and gain momentum.

The following exist as the goals of prewriting:

- Contemplating the many possible ideas worth writing about.

- Developing ideas through brainstorming, freewriting, and focused writing.

- Planning the structure of the essay overall so as to have a solid introduction, meaningful body paragraphs, and a purposeful conclusion.

Discovering and Developing Ideas

Quick prewriting activities.

Quick strategies for developing ideas include brainstorming, freewriting, and focused writing. These activities are done quickly, with a sense of freedom, while writers silence their inner critic. In her book Wild Mind , teacher and writer Natalie Goldberg describes this freedom as the “creator hand” freely allowing thoughts to flow onto the page while the “editor hand” remains silent. Sometimes, these techniques are done in a timed situation (usually two to ten minutes), which allows writers to get through the shallow thoughts and dive deeper to access the depths of the mind.

Brainstorming begins with writing down or typing a few words and then filling the page with words and ideas that are related or that seem important without allowing the inner critic to tell the writer if these ideas are acceptable or not. Writers do this quickly and without too much contemplation. Students will know when they are succeeding because the lists are made without stopping.

Freewriting is the “most effective way” to improve one’s writing, according to Peter Elbow, the educator and writer who first coined the term “freewriting” in pivotal book Writing Without Teachers , published in 1973. Freewriting is a great technique for loosening up the writing muscle. To freewrite, writers must silence the inner critic and the “editor hand” and allow the “creator hand” a specified amount of time (usually from 10 to 20 minutes) to write nonstop about whatever comes to mind. The goal is to keep the hand moving, the mind contemplating, and the individual writing. If writers feel stuck, they just keep writing “I don’t know what to write” until new ideas form and develop in the mind and flow onto the page.

Focused freewriting entails writing freely—and without stopping, during a limited time—about a specific topic. Once writers are relaxed and exploring freely, they may be surprised about the ideas that emerge.

Operation Beat Writer’s Block: Brainstorming

Let’s start with a basic brainstorming activity.

- Watch the following video from Wisconsin Technical College System (WTCS) and think about what makes brainstorming an essential prewriting activity. What are some of the potential costs of not brainstorming?

- Don’t have a topic yet or need to think through things more before you attempt the mind map? Try the brainstorming exercise embedded in the video itself (at the 1:50 mark).

Next Step: Create a Mind Map to Visualize Your Essay

Mind mapping is an early stage prewriting strategy that you can use to help generate ideas for an essay. It lets you visually map out an essay and then organize and expand these loose ideas into an increasingly coherent and nuanced project. As the following video will demonstrate, mind maps can take a variety of forms, but regardless of what your map looks like, mind maps offer an invaluable way to move past writer’s block and let your ideas flow.

- Watch the following video from Wisconsin Technical College System (WTCS) on mind mapping and free writing.

- When you’ve finished, use the template that follows to map out your essay! Don’t have a topic yet? Try the exercise embedded in the video itself.

Use This Mind Mapping Template to Map Out Your Paper!

Click Here to Download the PDF

Template Created by Scott Ortolano

Researching

Unlike quick prewriting activities, researching is best done slowly and methodically and, depending on the project, can take a considerable amount of time. Researching is exciting, as students activate their curiosity and learn about the topic, developing ideas about the direction of their writing. The goal of researching is to gain background understanding on a topic and to check one’s original ideas against those of experts. However, it is important for the writer to be aware that the process of conducting research can become a trap for procrastinators. Students often feel like researching a topic is the same as doing the assignment, but it’s not.

The two aspects of researching that are often misunderstood are as follows:

- Writers start the research process too late so the information they find never really becomes their own setting themselves up for way more quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing the words of others than is appropriate for the 70% one’s own words and 30% the words of others ratio necessary for college-level research-based writing.

- Writers become so involved in the research process that they don’t start the actual writing process soon enough so as to meet a due date with a well written, edited, and revised finished composition.

Being thoughtful about limiting one’s research time—and using a planner of some sort to organize one’s schedule—is a way to keep oneself from starting the research process too late to

See Part V of this book for more information about researching.

Audience and Purpose

It’s important that writers identify the audience and the purpose of a piece of writing. To whom is the writer communicating? Why is the writer writing? Students often say they are writing for whomever is grading their work at the end. However, most students will be sharing their writing with peers and reviewers (e.g., writing tutors, peer mentors). The audience of any piece of college writing is, at the very minimum, the class as a whole. As such, it’s important for the writer to consider the expertise of the readers, which includes their peers and professors). There are even broader applications. For example, students could even send their college writing to a newspaper or a legislator, or share it online for the purpose of informing or persuading decision-makers to make changes to improve the community. Good writers know their audience and maintain a purpose to mindfully help and intentionally shape their essays for meaning and impact. Students should think beyond their classroom and about how their writing could have an impact on their campus community, their neighborhood, and the wider world.

Planning the Structure of an Essay

Planning based on audience and purpose.

Identifying the target audience and purpose of an essay is a critical part of planning the structure and techniques that are best to use. It’s important to consider the following:

- Is the the purpose of the essay to educate, announce, entertain, or persuade?

- Who might be interested in the topic of the essay?

- Who would be impacted by the essay or the information within it?

- What does the reader know about this topic?

- What does the reader need to know in order to understand the essay’s points?

- What kind of hook is necessary to engage the readers and their interest?

- What level of language is required? Words that are too subject-specific may make the writing difficult to grasp for readers unfamiliar with the topic.

- What is an appropriate tone for the topic? A humorous tone that is suitable for an autobiographical, narrative essay may not work for a more serious, persuasive essay.

Hint: Answers to these questions help the writer to make clear decisions about diction (i.e., the choice of words and phrases), form and organization, and the content of the essay.

Use Audience and Purpose to Plan Language

In many classrooms, students may encounter the concept of language in terms of correct versus incorrect. However, this text approaches language from the perspective of appropriateness. Writers should consider that there are different types of communities, each of which may have different perspectives about what is “appropriate language” and each of which may follow different rules, as John Swales discussed in “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Essentially, Swales defines discourse communities as “groups that have goals or purposes, and use communication to achieve these goals.”

Writers (and readers) may be more familiar with a home community that uses a different language than the language valued by the academic community. For example, many people in Hawai‘i speak Hawai‘i Creole English (HCE colloquially regarded as “Pidgin”), which is different from academic English. This does not mean that one language is better than another or that one community is homogeneous in terms of language use; most people “code-switch” from one “code” (i.e., language or way of speaking) to another. It helps writers to be aware and to use an intersectional lens to understand that while a community may value certain language practices, there are several types of language practices within our community.

What language practices does the academic discourse community value? The goal of first-year-writing courses is to prepare students to write according to the conventions of academia and Standard American English (SAE). Understanding and adhering to the rules of a different discourse community does not mean that students need to replace or drop their own discourse. They may add to their language repertoire as education continues to transform their experiences with language, both spoken and written. In addition to the linguistic abilities they already possess, they should enhance their academic writing skills for personal growth in order to meet the demands of the working world and to enrich the various communities they belong to.

Use Techniques to Plan Structure

Before writing a first draft, writers find it helpful to begin organizing their ideas into chunks so that they (and readers) can efficiently follow the points as organized in an essay.

First, it’s important to decide whether to organize an essay (or even just a paragraph) according to one of the following:

- Chronological order (organized by time)

- Spatial order (organized by physical space from one end to the other)

- Prioritized order (organized by order of importance)

There are many ways to plan an essay’s overall structure, including mapping and outlining.

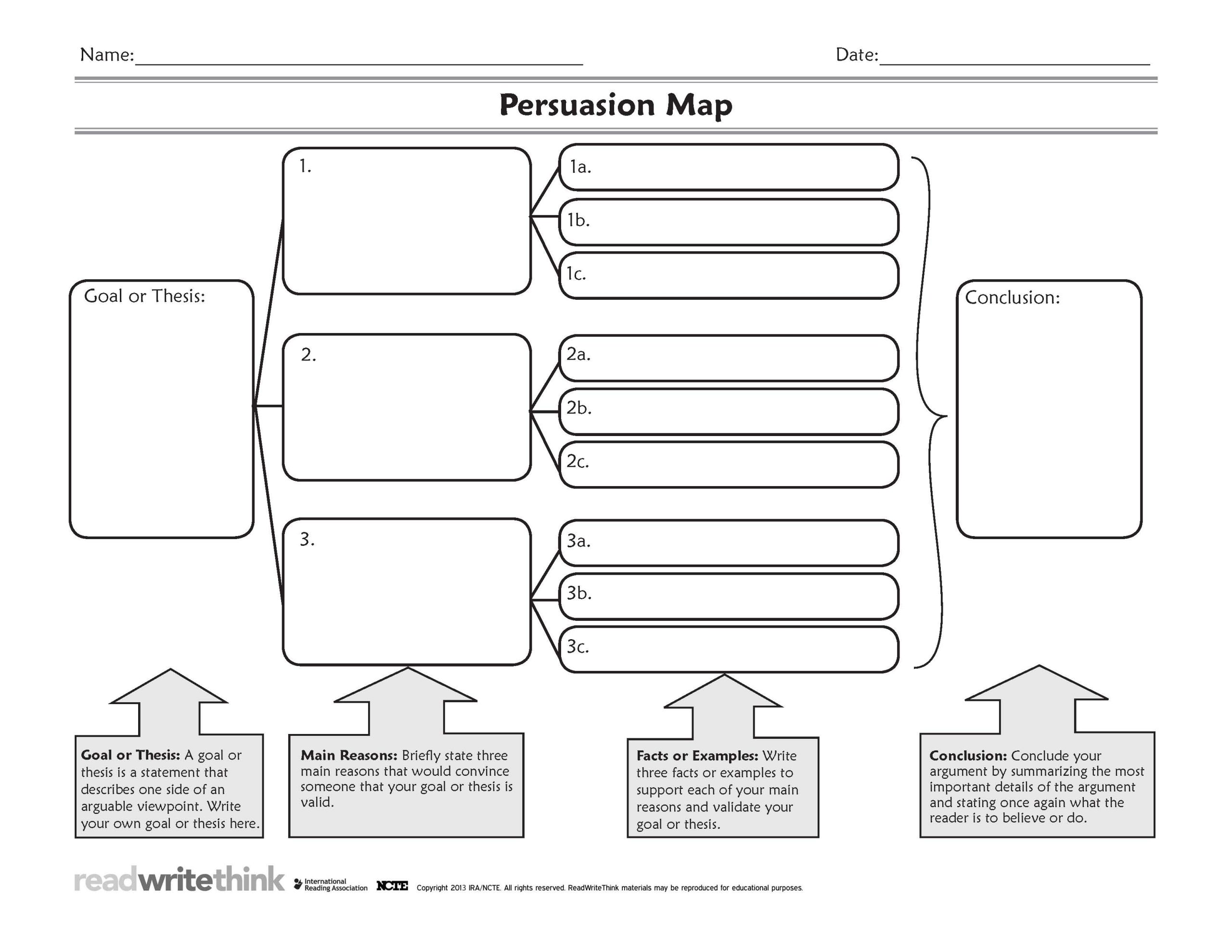

Mapping (which sometimes includes using a graphic organizer) involves organizing the relationships between the topic and other ideas. The following is example (from ReadWriteThink.org, 2013) of a graphic organizer that could be used to write a basic, persuasive essay:

Outlining is also an excellent way to plan how to organize an essay. Formal outlines use levels of notes, with Roman numerals for the top level, followed by capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters. Here’s an example:

- Hook/Lead/Opener: According to the Leilani was shocked when a letter from Chicago said her “Aloha Poke” restaurant was infringing on a non-Hawaiian Midwest restaurant that had trademarked the words “aloha” (the Hawaiian word for love, compassion, mercy, and other things besides serving as a greeting) and “poke” (a Hawaiian dish of raw fish and seasonings).

- Background information about trademarks, the idea of language as property, the idea of cultural identity, and the question about who owns language and whether it can be owned.

- Thesis Statement (with the main point and previewing key or supporting points that become the topic sentences of the body paragraphs): While some business people use language and trademarks to turn a profit, the nation should consider that language cannot be owned by any one group or individual and that former (or current) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups, and legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good of internal peace of the country.

- Legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good and internal peace of the country.

- Conclusion ( Revisit the Hook/Lead/Opener, Restate the Thesis, End with a Twist— a strong more globalized statement about why this topic was important to write about)

Note about outlines: Informal outlines can be created using lists with or without bullets. What is important is that main and subpoint ideas are linked and identified.

- Use 10 minutes to freewrite with the goal to “empty your cup”—writing about whatever is on your mind or blocking your attention on your classes, job, or family. This can be a great way to help you become centered, calm, or focused, especially when dealing with emotional challenges in your life.

- For each writing assignment in class, spend three 10-minute sessions either listing (brainstorming) or focused-writing about the topic before starting to organize and outline key ideas.

- Before each draft or revision of assignments, spend 10 minutes focused-writing an introduction and a thesis statement that lists all the key points that supports the thesis statement.

- Have a discussion in your class about the various language communities that you and your classmates experience in your town or on your island.

- Create a graphic organizer that will help you write various types of essays.

- Create a metacognitive, self-reflective journal: Freewrite continuously (e.g., 5 times a week, for at least 10 minutes, at least half a page) about what you learned in class or during study time. Document how your used your study hours this week, how it felt to write in class and out of class, what you learned about writing and about yourself as a writer, how you saw yourself learning and evolving as a writer, what you learned about specific topics. What goals do you have for the next week?

During the second half of the semester, as you begin to tackle deeper and lengthier assignments, the journal should grow to at least one page per day, at least 20 minutes per day, as you use journal writing to reflect on writing strategies (e.g., structure, organization, rhetorical modes, research, incorporating different sources without plagiarizing, giving and receiving feedback, planning and securing time in your schedule for each task involved in a writing assignment) and your ideas about topics, answering research questions, and reflecting on what you found during research and during discussions with peers, mentors, tutors, and instructors. The journal then becomes a record of your journey as a writer, as well as a source of freewriting on content that you can shape into paragraphs for your various assignments.

Works Cited

Elbow, Peter. Writing Without Teachers . 2nd edition, 1973, Oxford UP, 1998.

Goldberg, Natalie. Wild Mind : Living the Writer’s Life. Bantam Books, 1990.

Swales, John. “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings , 1990, pp. 21-32.

For more about discourse communities, see the online class by Robert Mohrenne “ What is a Discourse Community? ” ENC 1102 13 Fall 0027. University of Central Florida, 2013.

Sources Used to Create This Chapter

The majority of the content for this section has been adapted from OER Material from “Prewriting, ” in Ann Inoshita, et al’s English Composition: Connect, Collaborate, Communicate (2019). This work was published under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States (CC BY 3.0 US) License.

Media Resources

Remixed and Compiled by Scott Ortolano

An Overview of Academic Writing, Planning, and Prewriting Copyright © by Leonard Owens III; Tim Bishop; and Scott Ortolano is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Character Education

- Classroom Management

- Cultural Responsive

- Differentiation

- Distance Learning

- Explicit Teaching

- Figurative Language

- Interactive Notebooks

- Mentor Text

- Monthly/Seasonal

- Organization

- Social Emotional Learning

- Social Studies

- Step-by-Step Instruction

- Teaching Tips

- Testing and Review

- Freebie Vault Registration

- Login Freebie Album

- Lost Password Freebie Album

- FREE Rockstar Community

- In the News

- Writing Resources

- Reading Resources

- Social Studies Resources

- Interactive Writing Notebooks

- Interactive Reading Notebooks

- Teacher Finds

- Follow Amazon Teacher Finds on Instagram

- Rockstar Writers® Members Portal Login

- FREE MASTERCLASS: Turn Reluctant Writers into Rockstar Writers®

- Enroll in Rockstar Writers®

Are you ready to give your students a narrative writing prompt but don’t know where to start? The first step of the writing process is prewriting. This post will focus on ideas to use in your writing class to encourage prewriting in a narrative essay. This writing mini lesson along with several posts following it will scaffold through the writing process for narrative writing. They are linked to each other to provide you with a smooth transition from one lesson to the next! These ideas are ideal for any writing curriculum and writer’s workshop.

I love love love our notebooks and referring back to our previous lessons! I hold my little ones accountable for the skills already introduced! For example, since we’ve already covered complete sentence structure and paragraph writing , I expect my class to use these skills in their writing. I even have my Math/Science partner on board and she keeps them accountable too! Woo woo!

Step One of the Writing Process is PREWRITING . Let the writing begin!!!!!

Use the anchor chart to teaching student the meaning of brainstorming and using graphic organizers.

How to choose ideas. This is for the prompt A SHATTERED WINDOW. Talk out loud so students can hear your thinking. “There are many things that can shatter a window. If someone throws a baseball too wild or a bird who didn’t know a window was there or someone threw a rock to be mean. What else can shatter a window?” After students add some ideas say, “I am choosing “A shelf fell and broke the kitchen window” because I can come up with many ideas to go along with it. We have a big shelf in our kitchen and if it fell, it would definitely break a window in there.”

3. TAKE NOTES AND APPLY TO STUDENTS’ STORY

Have students write ideas for their stories and choose one. This is an example from the interactive writing notebooks. Students write their ideas on the front of the light bulb. Then lift the light bulb and choose one that they will use! When using interactive notebooks, I allow students to get creative. If they want to do theirs differently, go for it! They will take more ownership!

Students will enjoy coming up with ideas and working in their notebooks. Each little mini lesson will be the foundation for the next lesson. This is a scaffolding approach using the writing process. Explain to your students that it will take weeks and weeks to write one story so they could see each important step! It might seem drawn out, but it is so worth it in the end!

GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS: This is a good time to hand out a graphic organizer. Students will need a way to organize their writing. I have a variety packet of graphic organizers FREE HERE .

Check out my FREE writing masterclass! CLICK HERE

LAST LESSON: 3 STEPS TO PREPARE FOR NARRATIVE WRITING

NEXT LESSON: WRITING MINI LESSON #12- TASK, PURPOSE, AUDIENCE FOR NARRATIVE WRITING!

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL LIST OF WRITING MINI LESSONS

This lesson is also included in the STEP-BY-STEP WRITING ® Program with mini-lessons designed to scaffold through the writing process. Writing units included are sentence structure, paragraph writing, narrative writing, opinion writing, and informative writing. See what is included in the image below and click on it to learn more about them! You will turn your reluctant writers into ROCKSTAR WRITERS ™!

“I cannot praise this resource enough!!! I wanted to give it a 5-star rating in every category. It is truly the most comprehensive and engaging writing resource I have ever had the privilege of using. This purchase was worth every cent!!!! Thank you so much for making it available!” – Tina

Writing Mini Lesson #10- 3 Steps to Prepare for Narrative Writing

Mini lesson #12- task, purpose, audience for narrative writing.

Prewriting the Narrative Essay Composition 101

For Wednesday, we'll begin the process of writing the narrative essay by doing some Prewriting, the first stage in the three part process of writing: Prewriting, Writing, and Rewriting.

Many people try to skip over this Prewriting section, but it's impossible. It's just possible to do very little of it, or try to do it all in your head instead of on paper. But using paper (or a word-processor) can give you a chance to get things organized. People might not notice that a story told orally is loosely constructed, but they'll be able to tell if a written one was. Developing some strategies for prewriting can make a dramatic improvement in the quality of the organization and development of your papers.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that it's not writing; it's just exploring and mapping what you explore, and what you write there may or may not appear in the final draft. You want to collect as much as you can and sort it out later. Don't try to sort as you collect. That would be like sorting the berries by size as you pick them. Sort them later! Pick them now! Don't worry about whether it's a good idea to include it or a bad one; you can decide that later.

Within the Prewriting stage, some say there are other stages. We begin by choosing a topic, then we collect information on it, then we begin to focus , and then we put things in order . Once we've ordered things, we're ready to draft, or do the writing.

Here are some strategies for developing ideas about your narrative. They're strategies for collecting information and ideas. Each is demonstrated in a sample here .

Listing or Brainstorming: Listing is simply making a list of the things that come to mind when you consider the subject you're interested in. If you're telling a story about the first day of school, you might write your teacher's name, the name of the school, other classmates, where you lived, your sister's name, the kind of car you had. Maybe you remember a book or a tablet or the type of shirt or hat that a classmate was wearing. Whether they seem relevant or not, write them down.

Clustering: Clustering is very similar to Listing, but it's more graphical, and harder to do on a word processor without special software. Writers begin by writing a key word in the middle of a page, perhaps with a circle around it. Then they'll draw a line out and write a word that's related. From there they might another word at the same level or draw a line from the second word to something else that's related.

Freewriting: Freewriting is a kind of slap-dash writing, where you force yourself to keep going on a topic without thinking much about it. It's very loose writing, even more loose than a diary entry might be. The trick is to keep driving on. Give yourself a time limit--say ten minutes--and write like crazy on the topic you've picked. Don't let yourself stop or cross out or tell yourself that it's stupid. Again, don't edit as you go. Look at my example ! It wanders all over! But I was surprised in writing it that I got to thinking about what the town must have been like then. It's something I know now, but I didn't know then.

Once you have collected a lot of information, you have to begin to sort it out, bring it into focus. I like this stage because I can see something taking shape. I don't like to begin to draft an essay until I've got at least a simple outline of what I plan to do in what order. So I usually make a brief listing of words that I think will keep me on track. Then I write the draft. But not before!

Home Page | Schedule | Nelson's Home Page | Email Nelson | Pluto | Discussion Board | Mundt Library | Tutorial

GKT103: General Knowledge for Teachers – Essays

Pre-Writing

Sitting down for an exam and reading an essay prompt can be intimidating. One way to ease your nerves and help you focus on the task is to pre-write. Pre-writing is a way to think through the essay question, gather your thoughts, and keep yourself from becoming overwhelmed. This resource explains pre-writing and shows strategies you can practice now and use on exam day to help ensure that you start your essay writing off on the right foot!

Planning the Structure of an Essay

Planning based on audience and purpose.

Identifying the target audience and purpose of an essay is a critical part of planning the structure and techniques that are best to use. It's important to consider the following:

- Is the the purpose of the essay to educate, announce, entertain, or persuade?

- Who might be interested in the topic of the essay?

- Who would be impacted by the essay or the information within it?

- What does the reader know about this topic?

- What does the reader need to know in order to understand the essay's points?

- What kind of hook is necessary to engage the readers and their interest?

- What level of language is required? Words that are too subject-specific may make the writing difficult to grasp for readers unfamiliar with the topic.

- What is an appropriate tone for the topic? A humorous tone that is suitable for an autobiographical, narrative essay may not work for a more serious, persuasive essay.

Hint: Answers to these questions help the writer to make clear decisions about diction (i.e., the choice of words and phrases), form and organization, and the content of the essay.

Use Audience and Purpose to Plan Language

In many classrooms, students may encounter the concept of language in terms of correct versus incorrect. However, this text approaches language from the perspective of appropriateness. Writers should consider that there are different types of communities, each of which may have different perspectives about what is "appropriate language" and each of which may follow different rules, as John Swales discussed in "The Concept of Discourse Community". Essentially, Swales defines discourse communities as "groups that have goals or purposes, and use communication to achieve these goals".

Writers (and readers) may be more familiar with a home community that uses a different language than the language valued by the academic community. For example, many people in Hawai‘i speak Hawai‘i Creole English (HCE colloquially regarded as "Pidgin"), which is different from academic English. This does not mean that one language is better than another or that one community is homogeneous in terms of language use; most people "code-switch" from one "code" (i.e., language or way of speaking) to another. It helps writers to be aware and to use an intersectional lens to understand that while a community may value certain language practices, there are several types of language practices within our community.

What language practices does the academic discourse community value? The goal of first-year-writing courses is to prepare students to write according to the conventions of academia and Standard American English (SAE). Understanding and adhering to the rules of a different discourse community does not mean that students need to replace or drop their own discourse. They may add to their language repertoire as education continues to transform their experiences with language, both spoken and written. In addition to the linguistic abilities they already possess, they should enhance their academic writing skills for personal growth in order to meet the demands of the working world and to enrich the various communities they belong to.

Use Techniques to Plan Structure

Before writing a first draft, writers find it helpful to begin organizing their ideas into chunks so that they (and readers) can efficiently follow the points as organized in an essay.

First, it's important to decide whether to organize an essay (or even just a paragraph) according to one of the following:

- Chronological order (organized by time)

- Spatial order (organized by physical space from one end to the other)

- Prioritized order (organized by order of importance)

There are many ways to plan an essay's overall structure, including mapping and outlining.

Mapping (which sometimes includes using a graphic organizer) involves organizing the relationships between the topic and other ideas. The following is example (from ReadWriteThink.org, 2013) of a graphic organizer that could be used to write a basic, persuasive essay:

Outlining is also an excellent way to plan how to organize an essay. Formal outlines use levels of notes, with Roman numerals for the top level, followed by capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters. Here's an example:

- Hook/Lead/Opener: According to the Leilani was shocked when a letter from Chicago said her "Aloha Poke" restaurant was infringing on a non-Hawaiian Midwest restaurant that had trademarked the words "aloha" (the Hawaiian word for love, compassion, mercy, and other things besides serving as a greeting) and "poke" (a Hawaiian dish of raw fish and seasonings).

- Background information about trademarks, the idea of language as property, the idea of cultural identity, and the question about who owns language and whether it can be owned.

- Thesis Statement (with the main point and previewing key or supporting points that become the topic sentences of the body paragraphs): While some business people use language and trademarks to turn a profit, the nation should consider that language cannot be owned by any one group or individual and that former (or current) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups, and legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good of internal peace of the country.

- Legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good and internal peace of the country.

- Conclusion (Revisit the Hook/Lead/Opener, Restate the Thesis, End with a Twist - a strong more globalized statement about why this topic was important to write about)

Note about outlines: Informal outlines can be created using lists with or without bullets. What is important is that main and subpoint ideas are linked and identified.

Prewriting and Outline

Every author fears that dreadful paralysis in front of a blank computer screen or a stark, white sheet of paper. “What do I write?” “How do I express my scattered thoughts?” “How do I overcome my fear of this assignment?!”

Whether one is writing a narrative, persuasive argument, research essay, or almost anything else, prewriting is a vital part of the writing process. It is a helpful tool for stimulating thoughts, choosing a topic, and organizing ideas. It can help get ideas out of the writer’s head and onto paper, which is the first step in making the ideas understandable through writing. Writers may choose from a variety of prewriting techniques, including brainstorming, clustering, and freewriting.

Brainstorming

In thinking about the assignment, write down whatever thoughts enter your mind, no matter how strange or irrelevant they may seem. For example, if your assignment is to write an informative research paper on AIDS in Africa, you might write down anything that comes to mind about AIDS in Africa: STDs, few doctors, limited medicine, prostitution, despair, orphans, grandparents as guardians, need for physical and moral education, etc. Once on paper, you can use these phrases to help formulate your ideas and sentences.

Begin with a word, circle it, and draw lines from the circle to other ideas as they occur to you. You may circle these new ideas and look for relationships between the various ideas, connecting them with lines. The movement here is from a general topic (in the center circle) to specific aspects of that topic (in the off-shooting circles).

Freewriting

Set a time limit (ten to fifteen minutes is suggested) and write in complete sentences as quickly as possible. Do not pause for correction or wait for a deep thought. If nothing comes to mind, write, “Nothing comes to mind,” until a new thought strikes you. The purpose is to focus and generate material while postponing criticism and editing for later. Journal writing and rough drafts are often a form of freewriting.

No matter which method of prewriting you choose, the key to success is turning off the internal editor or critic within yourself and working as swiftly and freely as possible. Most writers have an inner critic which assesses their writing as they compose. Although this critic is valuable in rewriting a paper, its judgmental character hinders thought flow in the initial stages of writing. The best way to prewrite is to ignore the voice of your inner critic and to write fluidly without stopping to correct mistakes. Later, when you look at what you have written, you can begin to re-organize what you have written; crafting your paper into points that are clear, concise, and relevant.

Constructing an outline is one of the best organizational techniques in preparing to write a paper. In making a basic outline, begin with a thesis and decide on the major points of the paper. Under these major points list specific subpoints. According to section 1.8 in the MLA Handbook, the descending parts of an outline are normally labeled in the following order: I., A., 1., a., (1), (a). Remember that if an outline includes a I., logic requires that it include a II. If there is an A., then there needs to be a B. (This rule assures that there are no unnecessary categories in the outline—in other words, it forces the writer to keep his/her thoughts specific and in order.)

Thesis: Saga deserves a #1 rating in The Princeton Review. I. There is a wide variety of food. A. Pizza 1. Saga is always creating new types of pizza. a. Mushroom and Spinach b. Taco Pizza 2. The crust of the pizza is usually soft and tasty. B. Vegetarian Food C. Falafel D. Couscous E. Stuffed Portobello Mushrooms F. Cereal G. Ten different kinds are always available H. Saga is continually rotating the selection. II. Saga’s atmosphere is conducive to students’ social needs.

Common organizing principles include:

- Chronology (useful for historical discussions – e.g., how the Mexican War developed)

- Cause and Effect (e.g., what consequences a scientific discovery will have)

- Process (e.g., how a politician got elected)

- Logic (deductive or inductive)

A deductive line of argument moves from the general to the specific (e.g., from the problem of violence in the United States to violence involving handguns), and an inductive one moves from the specific to the general (e.g., from violence involving handguns to the problem of violence in the United States) (MLA Handbook 32).

Internet Resources:

>> OWL Purdue Invention Guid e >> >> OWL Purdue Outlining Guid e >> >> UNC Understanding Assignments Guide e >> >> UNC Reading to Write Guide

Copyright © 2009 Wheaton College Writing Center

Strategies for Writing a Personal Narrative Essay

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- EPUB 3 Student View

- PDF Student View

- Thin Common Cartridge

- Thin Common Cartridge Student View

- SCORM Package

- SCORM Package Student View

- 1 - Prewriting Strategies for a Personal Narrative

- View all as one page

Prewriting Strategies for a Personal Narrative

Lesson Objective: To generate ideas based on personal experiences and to begin writing a personal story focused on one particular moment in one's life.

Materials Needed : paper, pen or pencil, a computer or mobile device with word processor software or application

In order to write a personal narrative, you must choose a personal experience to write about. There are many different ways to choose the focus of your essay. Once you have selected a significant moment in your life, you must recall important information about the experience, and then organize the details to make a lasting impression. Prewriting strategies are writing techniques that help you generate and clarify ideas. In this lesson, we will explore four prewriting strategies that can help you choose an experience for your personal narrative essay and help you organize information before you write your first draft.

PREWRITING STRATEGIES covered in this lesson

- EXPLORE TOPICS USING STORY STARTERS

- Mind Mapping

USING STORY STARTERS CAN HELP YOU JUMP START YOUR THOUGHTS

Often the hardest part of writing a personal narrative essay is choosing what to write about. Unless you are given a very specific prompt, such as write about the most important person in your life and how they have impacted your growth , it can be challenging to choose an experience. Try using a few of the following sentence starters or all of them to generate a list of personal experiences you could describe in your essay. Once you generate a list of topics, choose the experience that is most interesting to you.

- My best day ever... or My worst day ever...

- The day my best friend and I met each other...

- My life was almost ruined when...

- My most embarassing moment happened when...

- A neighbor helped me... or I helped a neighbor....

- I remember a time I overcame a challenge and...

- When I was born...

- I told a secret, and... or My secret was revealed...

- I was afraid, but...

- The most exciting thing that has ever happen to me is...

Choose one of these sentence starters to begin your personal narrative, or if you have another experience in mind, start by freewriting for five to ten minutes or longer.

FREEWRITE

Once you write the first sentence, you can use freewriting to generate more informaton about that chosen moment in your life. The key to freewriting is to continue writing continuously for a set amount of time. I recommend using a timer, so you don't need to look at a clock as you write. Write, even if specific details don't come to mind at first. Here's my example: When I was born ... Actually, I don't remember much about when I was born, but my parents told me that I was born a month early. I was premature according to my folks and my birth records confirm I weighed 4 lbs,. 2 oz. My lungs were slighty underdeveloped and I had difficulty breating. I remained in the hospital until I gained weight. Once I was ovr seven pounds, my parents were allowed to take me home. The had to build a tent around my crib and keep a humidifier on in side th tent to help my breathe easier Later, I was diagnosed with asthma.

Freewriting is also known as stream-of-consciouness writing. The important part is to keep writing, even if some of the details of a moment in your life come from what others have told you about the experience. Writing about those details may trigger your own memories. Also, do not worry about grammar, spelling, or the mechanics of writing at this prewriting stage. Just write! The goal is to write down as much as you can remember about the experience from you own memories or from the details others have shared with you.

Brainstorming is when you freely write down all ideas about your topic in the order which the thoughts come to you. So, after you choose an experience, complete your first sentence using a sentence starter, and/or freely write about the experience for a few minutes, you can use brainstorming techniques to write down more information about any moment in your llife. There are several brainstorming techiniques. Listing, clustering, and mind mapping are three popular methods of brainstorming.

Listing is a helpful technique to use when your topic is broad. Your personal life experience is a very broad topic, and you need to narrow the topic to a memorable experience that made a lasing impression. To make a list of possible experiences, start by making a list of your life experiences that brought you the most joy, experiences that brought you pain (physical, emotional, or social), experiences that helped you grow, and experiences that changed your perspective. You can either keep writing your narrative about the experience generated from the sentence starter or you can choose a more impactful experience for the listing exercise. Never be afraid to throw out the first idea for you essay for a better, more interesting idea.

PRACTICE EXERCISE: Make a list of at least ten experiences that have contributed to your personal growth and development. Here's my short list:

- Receiving my first journal as a birthday gift in second grade and beginnging to write poems

- Baking chocolate chip cookies with my tutor to learn about fractions and ratios

- Traveling to another country for the first time, while I was in h.s., and staying with a host family

- Being a NC Teaching Fellows, Honors Student, and Black Student Union President and UNC Charlotte

- Becoming a disciple of Jesus and deeply studying the Word of God

- Being a member of the Bouncing Bulldogs International Jump Rope Team

- Moving to Florida and becoming a title processor, working in the real estate industry

- Teaching at Children's Comprehensive Services of Charlotte and PACE Academy

- Joining the Visioneers Toastmasters Club and participating regularly in club meetings

- Giving birth to my son at the age of 38

Most of these experiences are still too broad for a personal narrative essay, since I have multiple stories I can share for each. Listing can also be used to narrow the focus for a particular experience. Here's a demonstration:

Selected experience: Traveling to another country for the first time, while in h.s., and staying with a host family

A list of how I matured through the experience:

- I traveled with a team, so I learned how to work cooperatively with others to share our skills.

- I was a junior in high school, and I was paired with an elementary school student to stay with two different host families during the week-long trip. So, I learned to be responsible for guiding a younger student, set a positive example, and to be flexible. I also learned to trust others outside of my family.

- I learned to enjoy and appreciate other cultures, as we attended cultural events and dwelled with two families living on the island of Bermuda.

I could narrow this list of experiences that occurred on the island of Bermuda to focus on a particular event. For example: I traveled with a team to Berrmuda when I was a junior in high school to share our skills by:

- turning Double Dutch and traveler for members of the Bouncing Bulldogs and Double Dutch Forces teams, during school performances for Diabetes Awareness Week on the island

- teaching primary school students jump rope skills during workshops throughout the week

- developing new routines that members of both teams could perform for members of the island community

You can keep creating more focused lists (subllists) until you have enough specific detials to write the initial draft of your personal narrative.

MIND MAPPING

Mind mapping is a more visual brainstorming technique. It can be used to help you think about a particular personal experience more deeply, and well as help you organize details into main topics and subtopic. You can create a mind map in three easy steps:

- Start in the middle of a blank page , writing or drawing (a picture of), the personal expereinc you intend to write your essay about.

- Write down the related subtopics around the central experience , connecting each of them with a line.

- Repeat the same process for the subtopics , generating leveled subtopics, connecting each of those supporting details to the corresponding subtopic.

Watch the video tutorial provided in this lesson's resource library on "How to Create a Mind Map" , then use the Simple Personal Mind Map Template to create your own mind map for the personal experience you selected.

Once you have applied one or two of these prewriting strategies, use your list(s) and/or mind map to begin writing the first paragraph of your personal narrative essay. Look for themes present in your list or in the topics presented on my your mind map which can help you formulate your thesis.

Attached Resources

Listing Memories

How To Create a Mind Map Tutorial

T-Chart

File size 70.3 KB

Simple Personal Mind Map Template

File size 87.9 KB

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Academic writing

- A step-by-step guide to the writing process

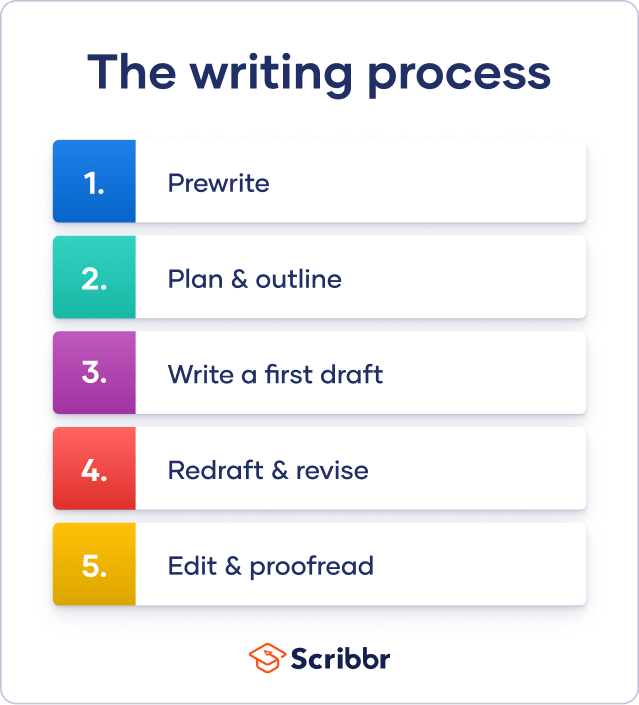

The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips

Published on April 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on December 8, 2023.

Good academic writing requires effective planning, drafting, and revision.

The writing process looks different for everyone, but there are five basic steps that will help you structure your time when writing any kind of text.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Table of contents

Step 1: prewriting, step 2: planning and outlining, step 3: writing a first draft, step 4: redrafting and revising, step 5: editing and proofreading, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about the writing process.

Before you start writing, you need to decide exactly what you’ll write about and do the necessary research.

Coming up with a topic

If you have to come up with your own topic for an assignment, think of what you’ve covered in class— is there a particular area that intrigued, interested, or even confused you? Topics that left you with additional questions are perfect, as these are questions you can explore in your writing.

The scope depends on what type of text you’re writing—for example, an essay or a research paper will be less in-depth than a dissertation topic . Don’t pick anything too ambitious to cover within the word count, or too limited for you to find much to say.

Narrow down your idea to a specific argument or question. For example, an appropriate topic for an essay might be narrowed down like this:

Doing the research

Once you know your topic, it’s time to search for relevant sources and gather the information you need. This process varies according to your field of study and the scope of the assignment. It might involve:

- Searching for primary and secondary sources .

- Reading the relevant texts closely (e.g. for literary analysis ).

- Collecting data using relevant research methods (e.g. experiments , interviews or surveys )

From a writing perspective, the important thing is to take plenty of notes while you do the research. Keep track of the titles, authors, publication dates, and relevant quotations from your sources; the data you gathered; and your initial analysis or interpretation of the questions you’re addressing.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Especially in academic writing , it’s important to use a logical structure to convey information effectively. It’s far better to plan this out in advance than to try to work out your structure once you’ve already begun writing.

Creating an essay outline is a useful way to plan out your structure before you start writing. This should help you work out the main ideas you want to focus on and how you’ll organize them. The outline doesn’t have to be final—it’s okay if your structure changes throughout the writing process.

Use bullet points or numbering to make your structure clear at a glance. Even for a short text that won’t use headings, it’s useful to summarize what you’ll discuss in each paragraph.

An outline for a literary analysis essay might look something like this:

- Describe the theatricality of Austen’s works

- Outline the role theater plays in Mansfield Park

- Introduce the research question: How does Austen use theater to express the characters’ morality in Mansfield Park ?

- Discuss Austen’s depiction of the performance at the end of the first volume

- Discuss how Sir Bertram reacts to the acting scheme

- Introduce Austen’s use of stage direction–like details during dialogue

- Explore how these are deployed to show the characters’ self-absorption

- Discuss Austen’s description of Maria and Julia’s relationship as polite but affectionless

- Compare Mrs. Norris’s self-conceit as charitable despite her idleness

- Summarize the three themes: The acting scheme, stage directions, and the performance of morals

- Answer the research question

- Indicate areas for further study

Once you have a clear idea of your structure, it’s time to produce a full first draft.

This process can be quite non-linear. For example, it’s reasonable to begin writing with the main body of the text, saving the introduction for later once you have a clearer idea of the text you’re introducing.

To give structure to your writing, use your outline as a framework. Make sure that each paragraph has a clear central focus that relates to your overall argument.

Hover over the parts of the example, from a literary analysis essay on Mansfield Park , to see how a paragraph is constructed.

The character of Mrs. Norris provides another example of the performance of morals in Mansfield Park . Early in the novel, she is described in scathing terms as one who knows “how to dictate liberality to others: but her love of money was equal to her love of directing” (p. 7). This hypocrisy does not interfere with her self-conceit as “the most liberal-minded sister and aunt in the world” (p. 7). Mrs. Norris is strongly concerned with appearing charitable, but unwilling to make any personal sacrifices to accomplish this. Instead, she stage-manages the charitable actions of others, never acknowledging that her schemes do not put her own time or money on the line. In this way, Austen again shows us a character whose morally upright behavior is fundamentally a performance—for whom the goal of doing good is less important than the goal of seeming good.

When you move onto a different topic, start a new paragraph. Use appropriate transition words and phrases to show the connections between your ideas.

The goal at this stage is to get a draft completed, not to make everything perfect as you go along. Once you have a full draft in front of you, you’ll have a clearer idea of where improvement is needed.

Give yourself a first draft deadline that leaves you a reasonable length of time to revise, edit, and proofread before the final deadline. For a longer text like a dissertation, you and your supervisor might agree on deadlines for individual chapters.

Now it’s time to look critically at your first draft and find potential areas for improvement. Redrafting means substantially adding or removing content, while revising involves making changes to structure and reformulating arguments.

Evaluating the first draft

It can be difficult to look objectively at your own writing. Your perspective might be positively or negatively biased—especially if you try to assess your work shortly after finishing it.

It’s best to leave your work alone for at least a day or two after completing the first draft. Come back after a break to evaluate it with fresh eyes; you’ll spot things you wouldn’t have otherwise.

When evaluating your writing at this stage, you’re mainly looking for larger issues such as changes to your arguments or structure. Starting with bigger concerns saves you time—there’s no point perfecting the grammar of something you end up cutting out anyway.

Right now, you’re looking for:

- Arguments that are unclear or illogical.

- Areas where information would be better presented in a different order.

- Passages where additional information or explanation is needed.

- Passages that are irrelevant to your overall argument.

For example, in our paper on Mansfield Park , we might realize the argument would be stronger with more direct consideration of the protagonist Fanny Price, and decide to try to find space for this in paragraph IV.

For some assignments, you’ll receive feedback on your first draft from a supervisor or peer. Be sure to pay close attention to what they tell you, as their advice will usually give you a clearer sense of which aspects of your text need improvement.

Redrafting and revising

Once you’ve decided where changes are needed, make the big changes first, as these are likely to have knock-on effects on the rest. Depending on what your text needs, this step might involve:

- Making changes to your overall argument.

- Reordering the text.

- Cutting parts of the text.

- Adding new text.

You can go back and forth between writing, redrafting and revising several times until you have a final draft that you’re happy with.

Think about what changes you can realistically accomplish in the time you have. If you are running low on time, you don’t want to leave your text in a messy state halfway through redrafting, so make sure to prioritize the most important changes.

Editing focuses on local concerns like clarity and sentence structure. Proofreading involves reading the text closely to remove typos and ensure stylistic consistency. You can check all your drafts and texts in minutes with an AI proofreader .

Editing for grammar and clarity

When editing, you want to ensure your text is clear, concise, and grammatically correct. You’re looking out for:

- Grammatical errors.

- Ambiguous phrasings.

- Redundancy and repetition .

In your initial draft, it’s common to end up with a lot of sentences that are poorly formulated. Look critically at where your meaning could be conveyed in a more effective way or in fewer words, and watch out for common sentence structure mistakes like run-on sentences and sentence fragments:

- Austen’s style is frequently humorous, her characters are often described as “witty.” Although this is less true of Mansfield Park .

- Austen’s style is frequently humorous. Her characters are often described as “witty,” although this is less true of Mansfield Park .

To make your sentences run smoothly, you can always use a paraphrasing tool to rewrite them in a clearer way.

Proofreading for small mistakes and typos

When proofreading, first look out for typos in your text:

- Spelling errors.

- Missing words.

- Confused word choices .

- Punctuation errors .

- Missing or excess spaces.

Use a grammar checker , but be sure to do another manual check after. Read through your text line by line, watching out for problem areas highlighted by the software but also for any other issues it might have missed.

For example, in the following phrase we notice several errors:

- Mary Crawfords character is a complicate one and her relationships with Fanny and Edmund undergoes several transformations through out the novel.

- Mary Crawford’s character is a complicated one, and her relationships with both Fanny and Edmund undergo several transformations throughout the novel.

Proofreading for stylistic consistency

There are several issues in academic writing where you can choose between multiple different standards. For example:

- Whether you use the serial comma .

- Whether you use American or British spellings and punctuation (you can use a punctuation checker for this).

- Where you use numerals vs. words for numbers.

- How you capitalize your titles and headings.

Unless you’re given specific guidance on these issues, it’s your choice which standards you follow. The important thing is to consistently follow one standard for each issue. For example, don’t use a mixture of American and British spellings in your paper.

Additionally, you will probably be provided with specific guidelines for issues related to format (how your text is presented on the page) and citations (how you acknowledge your sources). Always follow these instructions carefully.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, December 08). The Writing Process | 5 Steps with Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/writing-process/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, quick guide to proofreading | what, why and how to proofread, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Resources: Assignments

Assignment: narrative essay—prewriting and drafting.

Step 1: To view this assignment, click on Essay Assignment: Narrative Essay—Prewriting and Drafting.

Step 2: Follow the instructions in the assignment and submit your completed assignment into the LMS.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Authored by : Daryl Smith O' Hare and Susan C. Hines. Provided by : Chadron State College. Project : Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License : CC BY: Attribution

Jump to navigation

- Inside Writing

- Teacher's Guides

- Student Models

- Writing Topics

- Minilessons

- Shopping Cart

- Inside Grammar

- Grammar Adventures

- CCSS Correlations

- Infographics

Sign up or login to use the bookmarking feature.

Prewriting for Personal Narratives

Prewriting is your first step in writing a personal narrative. These prewriting activities will help you select a topic to write about, gather important details about the topic, and organize your thoughts before you begin a first draft.

Prewriting to Select a Topic

Explore topic ideas..

The goal for your narrative is to share a personal experience that taught you something or left a lasting impression. To help you think of topic ideas, complete as many of the sentence starters that follow as you can. Each complete sentence could become a topic for your narrative. Make a copy of this Google doc or download a Word template .

(Answers will vary.)

Choose your topic.

Choose a topic for your narrative. Pick from the topics suggested by the sentence starters above, or choose another topic you have in mind.

Prewriting to Gather Details

Before you can share a story, you need to remember all the important things that happened. Asking and answering the who? what? where? when? why? and how? ">5 W’s and H questions can activate your memory and help you record important details about your experience.

- Who was involved in the experience?

- Where did it happen?

- When did it happen?

- Why did it happen? (the background)

- How did you change because of the experience?

© 2024 Thoughtful Learning. Copying is permitted.

k12.thoughtfullearning.com

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

STEP 1: To get started writing, first pick at least one prewriting strategy (brainstorming, rewriting, journaling, mapping, questioning, sketching) to develop ideas for your essay. Write down what you do, as you'll need to submit evidence of your prewrite. Remember that "story starters" are everywhere.

Interactive example of a narrative essay. An example of a short narrative essay, responding to the prompt "Write about an experience where you learned something about yourself," is shown below. Hover over different parts of the text to see how the structure works. Narrative essay example.