Chest X-ray - Pulmonary disease - Tuberculosis

Hover on/off image to show/hide findings

Tap on/off image to show/hide findings

- There are no radiological features which are in themselves diagnostic of primary mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (TB) but a chest X-ray may provide some clues to the diagnosis

- This image shows consolidation of the upper zone with ipsilateral hilar enlargement due to lymphadenopathy

- These are typical features of primary TB

- Note: The chest X-ray may be normal in primary TB, in fact most patients infected are never unwell enough to require a chest X-ray

Healed primary TB

- Following an immune response to primary infection, a caseating granuloma forms which calcifies over time – this is known as a ‘Ghon focus’ – TB has gone!

- A Ghon focus is a rounded, well-defined focus of calcific density (as dense as bone) usually located in the periphery of the lung

- This chest X-ray shows a large, rounded calcified focus near the right hilum

- The CT (not usually necessary) shows it is located in the lung peripherally

- This is a particularly large Ghon focus

Post-primary TB

- Post-primary TB (secondary TB or reactivation TB) is more common in immunocompromised individuals – for example those with HIV/AIDS, those on immunosuppressing drugs, or those with malnutrition or diabetes

- The upper lobes are more commonly affected

- Consolidation often extends to the hilum

- The hilar structures may be distorted due to volume loss of the upper lobe

Post-primary TB – Lung cavity

- (Same patient as image above – 4 months later)

- Cavities are a common finding in mycobacterial infection

Healed post-primary TB

- Following an immune response to post-primary infection, the affected area often becomes scarred (fibrotic) and calcified

- The combined fibrosis and calcification can be described as ‘fibro-calcific change’

- Miliary TB is due to disseminated spread of mycobacterial infection

- It can occur either at the time of primary infection or on disease reactivation – prognosis is poor

- Very fine nodules are typically seen scattered throughout the lungs

Page author: Dr Graham Lloyd-Jones BA MBBS MRCP FRCR - Consultant Radiologist - Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust UK ( Read bio )

Last reviewed: October 2019

Tuberculosis (summary)

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created Jeremy Jones had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Liz Silverstone had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- TB (summary)

This is a basic article for medical students and other non-radiologists

Tuberculosis ( TB ) is a mycobacterial airborne infection that is typically asymptomatic in children but can reactivate in later life causing a destructive cavitating contagious pneumonia. Occasionally TB spreads through the bloodstream to infect the brain and other organs.

On this page:

Reference article, radiographic features.

- Related articles

- Cases and figures

This is a summary article ; read more in our article on tuberculosis .

epidemiology

according to the WHO 2023 report 1 :

globally TB causes more deaths than any other infectious disease

in 2022 it was estimated that 10.6 million people became ill with TB

most cases were in Southeast Asia (46%), Africa (23%) and the Western Pacific (18%)

around 6.3% of cases occurred in people living with HIV

diagnosis and treatment were disrupted by the COVID pandemic

presentation

primary infection

usually asymptomatic

may feel generally unwell or have a small pleural effusion

post-primary infection

non-specific systemic symptoms can lead to delayed diagnosis

weight loss

night sweats

pulmonary symptoms

productive cough (mucopurulent or blood-stained)

shortness of breath

extrapulmonary symptoms

depends on location of disease

M. tuberculosis

aerobic mycobacterium

Gram staining ineffective due to waxy coating

primary infection

first exposure to M. tuberculosis

the lung infection may be occult or may be visible as an area of consolidation in the mid or lower zone ( Ghon focus )

more commonly hilar and/or paratracheal lymphadenopathy are seen

most primary infections are asymptomatic and are contained remaining dormant (latent TB)

occasionally the host immune system does not contain the bacterium, and this leads to progressive primary TB or hematogenous spread (miliary TB)

post-primary TB is due to reactivation of infection when the immune system is impaired due to old age, immunosuppressive drugs, etc.

dormant bacteria are no longer contained and multiply in the lungs causing:

destructive cavitating upper zone pneumonia

multiplication of organisms within the cavities

airway communication with cavities leading to:

endobronchial spread within the lungs

airborne spread to others

miliary tuberculosis

disseminated disease spreads through the blood

tuberculomas in brain, kidney, bone, etc

tuberculous meningitis

may follow primary or post-primary infection

poor prognosis

TB in HIV-AIDS presents with a primary pattern; immune compromise means that the body responds as if it is a first exposure

miliary disease is common

investigation

chest X-ray

sputum sample

Ziehl-Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli

culture for confirmation of diagnosis and sensitivity testing

blood tests

interferon gamma release assay (IGRA)

GeneXpert nucleic acid amplification test and antibiotic sensitivity

HIV serology

brain MRI (miliary TB)

lumbar puncture

investigation for TB meningitis

four-drug regimen of rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol (2 months)

continuation of rifampin and isoniazid (4 months)

rifampin and isoniazid (3 months)

OR isoniazid alone (9 months)

OR rifampin alone (4 months)

multidrug-resistant TB is an increasing problem

screening and prevention

when active TB is suspected, precautions need to be taken to avoid airborne spread

screening for latent TB

Mantoux test (tuberculin skin test)

BCG vaccine

recommended for high-risk groups

contact-tracing

TB is a notifiable disease

primary infection is the result of close contact with a contagious individual, often a family member

reactivation tuberculosis is associated with cavities in which organisms breed and these can be spread by coughing

genetic fingerprinting of the organisms has cast doubt on the reliability of imaging to distinguish primary infection from reactivation 2

The manifestations of TB are strongly influenced by host immunity.

Chest radiograph

parenchymal consolidation

lymphadenopathy - most frequent manifestation

- pleural effusion

Ghon complex (consolidation plus lymphadenopathy)

patchy consolidation and cavitation (upper zones)

healing results in fibrosis and calcification

innumerable 1-3 mm diameter miliary nodules

uniform size and distribution throughout both lungs

thoracic spine infection may be apparent as bone destruction and paraspinal mass

CT is far more sensitive and demonstrates lesion characteristics which are helpful in diagnosis:

central necrosis in lymph nodes

areas of consolidation which may be occult on CXR

endobronchial spread (tree in bud opacities)

miliary nodules

signs of latent disease such as calcified granulomata and upper zone fibrocalcific disease

- 1. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. (2023) ISBN: 9789240083851 - Google Books

- 2. Jeong Y & Lee K. Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Up-To-Date Imaging and Management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(3):834-44. doi:10.2214/ajr.07.3896 - Pubmed

Incoming Links

- Investigation of haemoptysis (summary)

- Bronchiectasis (summary)

- Tuberculosis - multisystem involvement

Related articles: Education: Medical student curriculum

- radiology for students

- US carotids

- midline shift

- mass effect

- hydrocephalus

- brain mass lesion

- cerebral edema

- intracranial hemorrhage

- extra-axial collection

- extradural hemorrhage

- subdural hemorrhage

- subarachnoid hemorrhage

- ischemic stroke

- hemorrhagic stroke

- intracranial tumors

- cerebral abscess

- multiple sclerosis

- skull fractures

- spinal cord compression

- head injury

- focal weakness

- severe headache

- altered consciousness

- cauda equina syndrome

- cardiac radiology

- chest x-ray

- air-space opacification

- atelectasis

- air bronchogram

- pneumothorax

- pleural fluid

- increased cardiothoracic ratio

- pneumomediastinum

- surgical emphysema

- lobar collapse

- pulmonary edema

- heart failure

- symptomatic pneumothorax

- tension pneumothorax

- pulmonary embolism

- lung cancer

- mesothelioma

- bronchiectasis (and CF)

- tuberculosis

- breathlessness

- pleuritic chest pain

- pneumoperitoneum

- bowel dilatation

- fat-stranding

- free intraperitoneal fluid

- esophageal cancer

- gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- peptic ulcer disease

- gastric cancer

- bowel perforation

- small bowel obstruction

- intestinal ischemia

- appendicitis

- inflammatory bowel disease

- large bowel obstruction

- colorectal cancer

- diverticulitis

- anorectal disease

- acute pancreatitis

- gallstone disease

- acute cholecystitis

- obstructive jaundice

- malignant biliary tract obstruction

- renal tract calculi

- prostate cancer

- aortic aneurysm

- peripheral arterial disease

- breast cancer

- abdominal pain

- nausea and vomiting

- PR bleeding

- limb ischemia

- clavicle series

- shoulder series

- humerus series

- elbow series

- forearm series

- wrist series

- scaphoid series

- hand series

- both hands series

- thumb series

- pelvis x-ray

- femur x-ray

- tib/fib x-ray

- ankle x-ray

- calcaneus x-ray

- fracture type

- fracture location

- fracture displacement

- fracture complications

- shoulder x-ray - an approach

- elbow x-ray - an approach

- wrist x-ray - an approach

- clavicle fracture

- shoulder dislocation

- proximal humeral fracture

- humeral shaft fracture

- proximal radial fracture

- forearm fracture

- distal radial fracture

- scaphoid fracture

- pelvic fractures

- proximal femoral fractures

- distal fibula fracture

- 5th metatarsal fracture

- supracondylar fracture

- slipped upper femoral epiphysis

- Perthes disease

- major trauma

- osteoarthritis

- rheumatoid arthritis

- septic arthritis

- shoulder injury

- fall onto an outstretched hand

- lower limb injury

- foot and ankle injury

- the limping child

- acute monoarthritis

- polyarthritis

- pelvic US - transabdominal

- pelvic US - transvaginal

- hysterosalpingogram

- endometrial thickening

- ovarian cysts

- pelvic inflammatory disease

- tubo-ovarian abscess

- ovarian torsion

- ovarian neoplasms

- endometriosis

- endometrial hyperplasia

- endometrial carcinoma

- cervical cancer

- normal pregnancy

- abnormal first trimester

- ectopic pregnancy

- heterotopic pregnancy

- PV bleeding

- pelvic pain

- PV discharge

- early pregnancy

- key findings

- presentations

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

REVIEW ARTICLE | VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 | OPEN ACCESS DOI: 10.23937/2469-5793/1510073

The radiological diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis (tb) in primary care, basem abbas al ubaidi.

Consultant Family Physician, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain

* Corresponding author: Basem Abbas Al Ubaidi, Consultant Family Physician, Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Bahrain, E-mail: [email protected]

Received: April 06, 2017 | Accepted: March 20, 2018| Published: March 22, 2018

Citation: Al Ubaidi BA (2018) The Radiological Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis (TB) in Primary Care. J Fam Med Dis Prev 4:073. doi.org/10.23937/2469-5793/1510073

Copyright: © 2018 Al Ubaidi BA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The Bahrain screening program depends primarly on the use of chest x-ray and PPD, while not using both symptom inquiry and Xpert MTB/RIF (XP). The essential keys are to teach and train all physicians in the detection of early symptoms with x-ray findings of active, inactive and diagnose latent pulmonary tuberculosis.

TB screening programme, Confirmatory test of TB, Radiological finding of TB, Sensitivity and specificity of TB screening tests

Introduction

Setting a nationally standardized TB screening program is essential in the early detection of active pulmonary TB in Bahrain and training all Primary Care Physicians (PCPs) is vital for early detection of active TB cases [ 1 ].

TB screening is the process of system identification for apparently healthy people with suspected active TB by using tests, examinations, or other procedures which should be applied to risky groups [ 2 , 3 ].

The best method for TB screening is both symptom inquiry and chest radiograph (CXR), which depends on resource availability, cost and the expected yield [ 4 , 5 ].

The conventional three screening tests of TB are symptoms inquiry questionnaire by asking about the existence of prolonged productive cough, haemoptysis, night fever, night sweating, weight loss, and pleuritic chest pain, besides chest x-ray (CXR) and PPD screening test. The sensitivity of symptoms inquiry and CXR is better than other methods, and it has mirrors for any CXR abnormality' in symptomatic persons [ 4 , 6 ].

The common two confirmatory tests of active TB are sputum-smear microscopy (SSM) and Xpert MTB/RIF (XP). Nonetheless, most clinician's judgment to reach a diagnosis of active TB is from symptoms inquiry questionnaire and chest radiography findings. Any patients who do not respond after a short course of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be re-assessed for hidden TB [ 7 ].

The sensitivity and specificity of symptoms inquiry screening questionnaire are 77%, 66% respectively, while it is better in PPD 89%, 80% respectively; though it is higher in CXR reaches to 86%, 89% respectively [ 8 ].

Whereas, the sensitivity and specificity of the two confirmatory tests are 61%, 98% in SSM, respectively; though it is higher in XP reaches to 90%, 99% respectively [ 9 ]. The sensitivity and specificity analysis depend on many factors; such as the presence of HIV status, the age of the patient, the disease severity, background epidemiology, sputum processing and staining techniques, and diagnostic quality [ 7 , 9 , 10 ].

There is no ideal universal algorithm exist in primary care; nonetheless, the solution could be a screening test followed by one confirmatory test; or one screening test followed by two sequential confirmatory tests; or two parallel screening test followed by one confirmatory test; or two subsequent screening test followed by one confirmatory test [ 11 ].

Active primary pulmonary tuberculosis is a disease of infancy, or young adult when they are not exposed to the Mycobacterium TB bacilli. It may manifest as pneumonic consolidation (homogenous dense opacity or patchy opacification mostly in middle and lower lobes with or without hilar lymphadenopathy called Ghon complex. Other radiological features of active primary TB are either miliary opacities or pleural effusion or pulmonary oedema (Kerely B line) (Figure 1-6) [ 12 , 13 ].

However, the chest x-ray finding of inactive TB are many such as fibrosis, persistent calcification (Ghon's focus), and a tuberculoma (persistent mass like opacities) [ 12 , 13 ].

The Ghon's focus is a small granulomatous TB lesion presents either in the superior part of the lower lobe or, the inferior part of the upper lobe, while the Ghon's complex is same Ghon's focus plus hilar lymph node adenopathy (Figure 7-9) [ 12 , 13 ].

On the other hand, active post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis (TB reactivation or secondary TB) been a disease of the adult when the patient had previously exposed to Mycobacterium TB bacilli within the last two years when patient's immunity is deteriorating. X-ray findings of post-primary TB either an ill-defined patchy consolidation with a cavitary lesion or fibroproliferative disease with coarse reticulonodular densities usually involving the posterior segments of the upper lobe, or the superior segment of the lower lobe spread to endobronchial given "tree-in-bud" appearance [ 13 - 15 ]. The nodular lesion with poorly defined margins and with round density within the lung parenchyma also called hazy tuberculoma (Figure 10-14) [ 15 ].

The end sequels of secondary TB are either fibrocalcific scar, fibronodular scar with lobar collapse, traction bronchiectasis mucoid impactions, pleural thickening, and pleural calcification (Figure 15-21) [ 15 ].

In general, the physician should have a high index of suspicion of active TB lesion and should differentiate it from inactive TB lesion (Table 1) [ 16 , 17 ].

Table 1: Radiological lesion of active and inactive pulmonary TB. View Table 1

Latent TB infection is an asymptomatic individual with a routine chest x-ray, and a negative sputum smear has a positive skin test (PPD/TST) (Table 2) or blood IGRA test result indicate previous TB infection [ 16 , 17 ].

Table 2: Classification of the positive tuberculin skin test (PPD) reaction [ 18 ]. View Table 2

The physician should know the causes of false-positive PPD reactions (e.g., Infection with non-tuberculosis mycobacteria, prior BCG vaccination, incorrect method of the administration, wrong interpretation of reaction, an incorrect bottle of antigen used). Likewise, the physician should detect causes of false-negative PPD reactions (e.g., low immunity, recent or ancient TB infection, early infancy ≤ six months, current live-virus vaccination or disease, incorrect method of PPD administration, and incorrect interpretation of reaction) [ 16 , 17 ].

PPD is contraindicated only for people who had a previous severe reaction (e.g., acute necrosis, blistering, anaphylactic shock, or ulcerations) to an earlier TST [ 18 ].

Treatment of latent TB infection is a once-weekly regimen of mixed rifapentine plus isoniazid for three months instead of 9 months INH treatment [ 19 ].

The minor X-ray findings that not suggestive of TB disease require no follow-up evaluation (e.g., Pleural thickening, diaphragmatic tenting, blunting of costophrenic angle, solitary calcified nodules or granuloma, minor musculoskeletal findings, and minor cardiac findings) [ 20 - 26 ].

Setting nationally standardized TB screening program is essential for early detection of active pulmonary TB. The best methods for TB screening are parallel to both the symptom inquiry and the chest radiography (CXR). Physicians should be trained for early diagnosis of active TB; they should differentiate between active and inactive radiological signs. The physician should provide diagnosis of latent TB infection and give the proper management. TB algorithm should be simplified and updated regularly

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Competing interest, sponsorship.

- Al Ubaidi BA (2015) Tuberculosis Screening Among Expatriate in Bahrain. Int J Med Invest 3: 282-288.

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/tuberculosis-screening

- Lonnroth K, Corbett E, Golub J, Godfrey-Faussett P, Uplekar M, et al. (2013) Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: rationale, definitions and critical considerations. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 17: 289-298.

- van't Hoog AH, Langendam MW, Mitchell E, Cobelens FG, Sinclair D, et al. (2013) A Systematic Review of the Sensitivity and Specificity of Symptom- and Chest-Radiography Screening for Active Pulmonary Tuberculosis in HIV-Negative Persons and Persons with Unknown HIV Status.

- van't Hoog AH, Meme HK, Laserson KF, Agaya JA, Muchiri BG, et al. (2012) Screening strategies for tuberculosis prevalence surveys: the value of chest radiography and symptoms. PLoS One 7: e38691.

- van't Hoog AH, Laserson KF, Githui WA, Meme HK, Agaya JA, et al. (2011) High prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis and inadequate case finding in rural western Kenya. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 1245-1253.

- Steingart KR, Henry M, Ng V, Hopewell PC, Ramsay A, et al. (2006) Fluorescence versus conventional sputum smear microscopy for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 6: 570-581.

- Steingart KR, Sohn H, Schiller I, Kloda LA, Boehme CC, et al. (2014) Xpert(R) MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults (updated). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD009593.

- Steingart KR, Ng V, Henry M, Hopewell PC, Ramsay A, et al. (2006) Sputum processing methods to improve the sensitivity of smear microscopy for tuberculosis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 6: 664-674.

- Cattamanchi A, Davis JL, Pai M, Huang L, Hopewell PC, et al. (2010) Does bleach processing increase the accuracy of sputum smear microscopy for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis? J Clin Microbiol 48: 2433-2439.

- van't Hoog AH, Onozaki I, Lonnroth K (2014) Choosing algorithms for TB screening: a modelling study to compare yield, predictive value and diagnostic burden. BMC Infect Dis 14: 532.

- Burrill J, Williams CJ, Bain G, Conder G, Hine AL, et al. (2007) Tuberculosis: a radiologic review. Radiographics 27: 1255-1273.

- http://radiopaedia.org/articles/primary-pulmonary-tuberculosis

- Harisinghani MG, Mcloud TC, Shepard JA, Ko JP, Shroff MM, et al. (2000) Tuberculosis from head to toe. Radiographics 20: 449-470.

- http://radiopaedia.org/articles/post-primary-pulmonary-tuberculosis-1

- Sanofi Receives FDA Approval of Priftin ® (Rifapentine) Tablets for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection.

- Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, Shang N, Gordin F, et al. (2011) Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 365: 2155-2166.

- http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.htm

- http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/general/LTBIandActiveTB.htm

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell R (2007) Robbins Basic Pathology. (8 th edn), Saunders Elsevier, 516-522.

- Rossi SE, Franquet T, Volpacchio M, Gimenez A, Aguilar G (2005) "Tree-in-Bud Pattern at Thin-Section CT of the Lungs: Radiologic-Pathologic Overview". Radiographics 25: 789-801.

- http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=Pleural+thickening+x+ray&FORM=HDRSC

- http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=diaphragmatic+tenting+x+ray&go=Submit+Query&qs=ds&form=QBIR

- http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=blunting+of+costophrenic+angle+x+ray&go=Submit+Query&qs=ds&form=QBIR

- http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=solitary+pulmonary+calcified+nodules++&go=Submit+Query&qs=ds&form=QBIR

- http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=+calcific+pulmonary+granuloma++&go=Submit+Query&qs=ds&form=QBIR

TB Testing & Diagnosis

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Heemskerk D, Caws M, Marais B, et al. Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. London: Springer; 2015.

Tuberculosis in Adults and Children.

Chapter 3 clinical manifestations.

In this chapter we will review the clinical manifestations of tuberculosis disease.

3.1. Primary Tuberculosis

Primary (initial) infection is usually indicated by tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) conversion, which reflects a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction to protein products of M. tuberculosis . TST conversion usually occurs 3–6 weeks after exposure/infection; guidelines for its correct interpretation can be found at: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.htm . Primary infection remains undiagnosed in the majority of cases, as symptoms are mild, non-specific and usually self-resolving. A primary (Ghon) complex is formed, consisting of a granuloma, typically in the middle or lower zones of the lung (primary or Ghon focus) in combination with transient hilar and/or paratracheal lymphadenopathy and some overlying pleural reaction. The primary complex usually resolves within weeks or months, leaving signs of fibrosis and calcification detectable on chest X-ray. In general the risk of disease progression following primary infection is low, but young children and immunocompromised patients are at increased risk.

The natural history of a re-infection event is not well described, since we have no good measure of its occurrence. We know it is likely to be common in TB endemic areas, since molecular epidemiological evidence suggests that many disease episodes (the vast majority in some settings) result from currently circulating strains, representing recent infection/re-infection. A re-infection event probably triggers very similar responses to those observed with primary (first-time) infection and the risk of subsequent disease progression seems to be substantially reduced. However, re-infection is likely to occur multiple times during the lifetime of an individual living in a TB endemic area, which explains its large contribution to the disease burden observed.

Reactivation disease or post-primary TB are often used interchangeably for TB occurrence after a period of clinical latency. However, since reactivation disease is clinically indistinguishable from progressive primary disease or re-infection disease (DNA fingerprinting is required to distinguish reactivation from re-infection) the terminology is not descriptive or clinically useful. True reactivation disease is often preceded by an immunological impetus. Patients with immunocompromise due to severe malnutrition, HIV-infection, chronic hemodialysis, immunosuppressive therapy, diabetes or silicosis etc. are at increased risk.

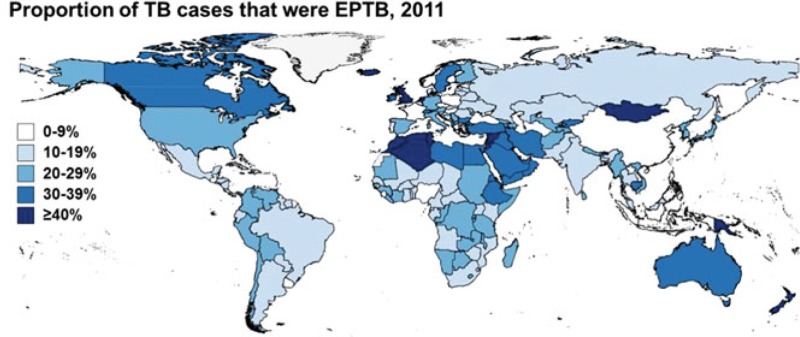

3.2. Pulmonary Tuberculosis

TB symptoms are usually gradual in onset and duration varying from weeks to months, although more acute onset can occur in young children or immunocompromised individuals. The typical triad of fever, nightsweats and weightloss are present in roughly 75, 45 and 55 % of patients respectively, while a persistent non-remitting cough is the most frequently reported symptom (95 %) ( Davies et al. 2014 ). Approximately 20 % of active TB cases in the US are exclusively extrapulmonary (EPTB), with an additional 7 % of cases having concurrent pulmonary and EPTB ( Peto et al. 2009 ).

3.2.1. Parenchymal Disease

Patients with cavitary lung disease typically present with (chronic) cough, mostly accompanied by fever and/or nightsweats and weightloss. Cough may be non-productive or the patient may have sputum, that can be mucoid, mucopurulent, blood-stained or have massive haemoptysis. Other symptoms may be chest pain, in patients with subpleural involvement, or dyspnoea, however rare. Upon auscultation, the findings in the chest may be disproportionally normal to the findings on chest X-ray. The results of the chest X-ray may be critical for treatment initiation for those patients who are sputum smear negative. In particular in low resource countries, chest X-ray interpretation is often done by non-expert medical staff, and missed diagnosis is common. Typical findings include normal chest X-ray, focal upper lobe opacities, diffuse opacities, consolidation, reticulonodular opacities, cavities ( Fig. 3.1a ), nodules, miliary pattern ( Fig. 3.1b ), intrathoracic lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion. In HIV-infected patients, smear yield is lower and radiological abnormalities may be less typical, frustrating diagnosis. Severely immune-suppressed patients and young children are less likely to present with cavitation on chest X-ray, and more frequently have miliary (disseminated) disease.

a Chest X-ray showing cavitary lung lesions ( white arrow ) and upper lobe opacities ( smaller red arrows ) in 46 year old male. b Chest X-ray with the classic ‘scattered millet seed’ appearance of milliaryTB 49 year old female. c Magnetic (more...)

3.2.2. Endobronchial Tuberculosis

Endobronchial TB is a specific form of pulmonary TB affecting the trachea and major bronchi. It is often misdiagnosed as bronchial asthma or bronchial malignancy. If unrecognized, the endobronchial lesions progress and cause stenosis. Symptoms are as those of pulmonary TB, however examination may include wheezing and dyspnoea may be more prominent. There may be a female predominance, with a male: female ratio of 1:2 ( Qingliang and Jianxin 2010 ; Xue et al. 2011 ). Bronchoscopy and biopsy is the most useful diagnostic tool and to establish a prognosis depending on which histological subtype is found. Sputum smear and culture should be performed, but varying test sensitivities are reported. Early therapy is needed in order to prevent strictures, treatment with standard first-line short-course regimen (see Treatment section), but treatment prolongation may be considered on a case by case basis, for those patients with intractable disease ( Xue et al. 2011 ).

3.2.3. Intra-Thoracic Lymphnode Disease

Following first-time infection the regional lymph nodes form part of the primary (Ghon) complex. Progressive disease may occur within these affected regional lymph nodes and is typically seen in young children. Symptoms are similar to those described for other forms of pulmonary TB, although the cough is rarely productive or the sputum blood-stained. Young children are unable to expectorate and the organism load is greatly reduced compared to adults with lung cavities, which complicates diagnosis ( Perez-Velez and Marais 2012 ). Enlarged peri-hilar and/or paratracheal lymph nodes may obstruct large airways with resultant collapse or hyperinflation of distal lung segments, form cold abscesses with persistent high fever, or erode into surrounding anatomical structures such as the pericardium leading to TB pericarditis. Peri-hilar and/or paratracheal lymph node enlargement with/without airway compression is the cardinal sign of intra-thoracic lymph node disease. Lymph nodes may also erupt into the airways with aspiration of infectious caseum leading to lobar consolidation and an expansile caseating pneumonia if the airway is completely obstructed.

3.3. Extra-Pulmonary Tuberculosis

3.3.1. Pleural Tuberculosis

Between 3 and 25 % of TB patients will have tuberculouspleuritis or pleural TB. As with all forms of extrapulmonary TB, incidence is higher in HIV-infected patients. In some high burden countries, TB is the leading cause of pleural effusions. Typical presentation is acute with fever, cough and localized pleuritic chest pain. It may follow recent primary infection or result from reactivation. If part of primary infection, the effusion may be self-limiting. However, if it occurs in pregnancy it signals a potential risk to foetus, since recent primary infection is frequently associated with the occult dissemination. TB pleural effusions are usually unilateral and of variable size. Approximately 20 % of patients have concurrent parenchymal involvement on chest X-ray, however CT-scans have higher sensitivity and may detect parenchymal lesions in up to 80 % of patients ( Light 2010 ). HIV infected patients may present with atypical symptoms, often with less pain and longer duration of illness and more generalized signs.

Pleural fluid is mostly lymphocytic with high protein content. Bacillary load is generally low and smear is typically negative, although this may be higher in HIV positive patients, in whom diagnostic yield from smear may be as high as 50 %. Elevated levels of adenosine deaminase (ADA) may be indicative; sensitivity and specificity estimates from a meta-analysis of published studies were 92 and 90 % respectively, with a cut-off value of 40U/l ( Liang et al. 2008 ). However ADA levels can be increased in other diseases, such as empyema, lymphomas, brucellosis, and Q fever, and the test cannot differentiate between these diseases. A negative result suggests that TB is unlikely, but should always be interpreted in the clinical context. Pleural biopsy may show granuloma in the parietal pleura and are highly suggestive of TB, even in the absence of caseation or AFB. Stain and culture of the pleural biopsy is reported to have a higher yield than pleural fluid (positive results in approximately 25 and 56 % of biopsies respectively) ( Light 2010 ).

3.3.2. Miliary Tuberculosis

Miliary TB can occur during primary infection and in post-primary disease. It indicates dissemination of disease and arises from the haematogenous spread of bacilli, which may occur shortly after primary infection or from any active disease site. Miliary granulomas are 1–3 mm in diameter (the size of a millet seed (Latin: milia)), are widespread and may be found in any visceral organ ( Davies et al. 2014 ). In immunocompetent patients, miliary TB accounts for approximately 3 % of TB cases and is more commonly found in immunocompromised patients (>10 % of HIV-infected patients) and in young children ( Sharma et al. 2005 ).

Clinical symptoms are mostly constitutional, including malaise, fever, weightloss, sweats, anorexia. Pulmonary signs may be similar but often less pronounced than in uncomplicated pulmonary TB. If the brain is involved, neurological symptoms may include headache, reduced consciousness and cranial nerve palsies. Involvement of other organs usually does not elicit localized symptoms. In immunocompromised patients physical signs may be less apparent and include dyspnoea, wasting, lymphnode enlargement, hepatosplenomegaly, cutaneous lesions. These patients are more at risk of meningeal involvement. Cutaneous involvement is rare (tuberculosis miliaria cutis), but if present may provide a valuable clue to the diagnosis. Rare complications including adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pneumothorax, cardiac and multi-organ dysfunction have been described. Due to the non-specific symptomatology, miliary TB is often only be discovered at post-mortem. A chest radiograph is pivotal in diagnosis, but is notoriously treacherous ( Fig. 3.1b ). A high index of suspicion is needed to be able to perceive the fine nodular lesions in more obscure cases. In uncertain cases, (high resolution) CT-scan is more sensitive in detecting the miliary lung nodularity ( Sharma et al. 2005 ). Miliary TB may be accompanied by consolidation (30 %), parenchymal lung cavities (3–12 %), or mediastinal and/or hilar lymphadenopathy (15 %) on chest X-ray ( Sharma et al. 2005 ). A missed diagnosis is grave, as untreated miliary TB often leads to TB meningitis and can be rapidly fatal.

Rapid diagnostic confirmation is not easily achieved, since cough is often non-productive, the sensitivity of conventional sputum smear is low. Smear may be performed on other bodily fluids such as gastric fluid, urine, cerebrospinal fluid, bronchial lavage and pleural fluid. Sputum culture may be positive in 30–60 % of patients. Tissue biopsy or fine needle aspiration may be indicated and should be sent for smear and biopsies examined for granulomatous disease. In tissue biopsies (liver, bonemarrow, transbronchial, pleura or lymphnode) confirmation rate is high and a diagnosis may be found in up to 83 % of cases.

3.3.3. Extra-Thoracic Lymphnode Disease

Cervical lymphadenitis (scrofula) is the most common form of extra-pulmonary TB. In the middle-ages it was known as ‘the King’s evil’ because it was believed the touch of royalty could cure the disease. Before the pasteurization of milk, the more likely causative agent was Mycobacterium bovis , which is non-distinguishable from M. tuberculosis on ZN stain. Some non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are known to cause lymphadenitis: Mycobacterium scrofulaceum, Mycobacterium avium-intracellular complex, Mycobacterium malmoense, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonei and Mycobacterium kansassi, of which Mycobacterium avium-intracellular complex is the most common causative agent ( Handa et al. 2012 ). The route of entry is thought to be through ingestion, via the oropharyngeal mucosa or tonsils, or through skin abrasions.

In the US, lymphadenitis accounts for 40 % of extra-pulmonary TB cases. The most common site is the cervical region, followed by mediastinal, axillary, mesenteric, hepatic portal, peripancreatic, and inguinal lymphnodes ( Rieder et al. 1990 ). Lymph node involvement may follow first-time infection as part of the primary (Ghon) focus, with subsequent haematogenous or lymphatic spread, with reactivation of a dormant focus or with direct extension of a contiguous focus.

The patient usually presents with a palpable (lymph node) mass greater than 2 × 2 cm and mostly in the cervical area (60 %), either in the jugular, posterior triangle or supraclavicular region, with or without fistula or sinus formation ( Handa et al. 2012 ). Other complications are overlying violaceous skin inflammation and cold abscess formation. Tenderness or pain is not typically described, unless there is secondary bacterial infection. Generalised constitutional symptoms and pulmonary symptoms or signs may be absent, but are more often reported in HIV-infected patients. The differential diagnosis includes bacterial adenitis, fungal infection, viral infection, toxoplasmosis, cat-scratch disease, neoplasms (lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma, Hodgkin’s disease, sarcoma), sarcoidosis, drug reactions and non-specific hyperplasia.

The history is important and chest X-ray should be obtained but may be normal in the majority. TST may be helpful in non-endemic countries, reported positive in over 85 % of patients, however it may be negative in patients with HIV infection and non-tuberculous lymphadenitis ( Razack et al. 2014 ).

Diagnosis is classically confirmed by excisional biopsy and histological and microbiological examination. Incisional biopsy has been associated with increased risk of sinus tract formation and is not recommended. Caseating granulomatous inflammation with Langhans and giant cells is highly suggestive of TB. Positive culture from biopsies are reported in between 60 and 80 %, with even higher rates reported fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), which has replaced more invasive biopsies as the diagnostic procedure of choice ( Handa et al. 2012 ). The diagnosis of lymph node TB can be achieved with a combination of FNAB cytology (detection of epithelioid cells), AFB smear, PCR and culture in over 80 % of cases ( Razack et al. 2014 ).

3.3.4. Central Nervous System Tuberculosis

The most common clinical manifestation of central nervous system (CNS) TB is tuberculous meningitis (TBM). Other entities are CNS tuberculoma, which may be present without symptoms or rarely with seizures, tuberculous encephalopathy (rare, only described in children) and tuberculous radiculomyelitis. Pathogenesis is thought to be through a two-step process, in which heamotogenous spread leads to a tuberculous focus (Rich focus) in the brain, which then invades and release bacilli in the subarachnoid space ( Donald et al. 2005 ). In HIV-infected patients and young children it is more often associated with miliary disease, which may indicate more direct haematogenous spread in these patients. TBM is the most lethal form of TB. Almost a third of HIV uninfected patients, and more than half of patients that are co-infected with HIV die from TBM, despite treatment. Half of the survivors suffer from permanent neurological impairment ( Thwaites et al. 2004 ).

Early recognition and appropriate treatment are key to improved outcome. Early symptoms are non-specific, including the suggestive triad of fever, nightsweats and weightloss and headache of increasing intensity. A duration of symptoms (headache and fever) of more than 5 days should prompt clinicians to include TBM in the differential diagnosis. In the more advanced stages patients become more confused, present with reduced consciousness, hemiplegia, paraplegia and urinary retention (seen with spinal involvement) and cerebral nerve palsies, most frequently involved is nerve VI (up to 40 % of cases), but also III and VII. Seizures are not frequently a presenting symptom in adults (seen in less than 5 % of cases), however often reported in children (50 % of TBM cases). Movement disorders may be seen and are associated with typical basal ganglia involvement. Upon examination, nuchal rigidity is typically less pronounced than in acute bacterial meningitis. Sixth nerve palsy is pathognomonic ( Thwaites and Tran 2005 ).

Diagnosis is often based on a clinical algorithm rather than mycobacterial isolation. Typical features on cerebral imaging on presentation are basal meningeal enhancement, hydrocephalus, and tuberculoma solitary or multiple (MRI shown in Fig. 3.1d ). Cerebral infarction may occur during treatment, mostly in the basal ganglia, or paradoxical tuberculoma may form. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is paucibacillary, thus diagnosis confirmed by AFB smear of the CSF is relatively rare (less than 20 % in most laboratories). CSF cellularity is typically lymphocytic (although neutrophils may predominate in the early stages), has raised protein content and moderately raised lactate (typically between 3 and 8 mmol/l), in contrast with bacterial meningitis in which lactate is generally higher. Raised ADA may aid diagnosis, however is not specific, particularly for the differentiation of bacterial meningitis ( Tuon et al. 2010 ). If TBM is suspected, large volumes (>6 ml) of CSF should be drawn and concentrated by centrifugation in order to facilitate microbiological confirmation. Meticulous examination of the smear for up to 30 min can significantly increase detection to over 60 % of those clinically diagnosed ( Thwaites et al. 2004 ).

In contrast to pulmonary TB where sputum smear is less often positive in HIV-infected individuals, CSF is more often positive in HIV-infected individuals with TBM. Liquid culture still provides the ‘gold standard’ (positive cultures found in approximately 65 % of clinical TBM cases), however results take 2–4 weeks and should not be awaited for treatment initiation. Xpert MTB/RIF is more sensitive than conventional smear and WHO currently recommends this PCR based test for the diagnosis of TBM ( Nhu et al. 2013 ; World Health Organization 2013 ). The current treatment guidelines are extrapolated from pulmonary regimens, with durations varying from 9 to 12 months of at least 4 first-line agents and including adjunctive corticosteroids ( Prasad and Singh 2008 ; Chiang et al. 2014 ). However a recent study suggests that the addition of fluoroquinolones and higher doses of rifampicin may improve treatment outcome, since CSF penetration of most of the first-line TB drugs (particularly rifampicin, streptomycin and ethambutol) is poor ( Ruslami et al. 2012 ). Surgical intervention may be indicated in cases with severe non-communicating hydrocephalus and large tuberculousabcesses.

3.3.5. Tuberculous Pericarditis

Cardiac TB most frequently involves the pericardium. TB endocarditis or involvement of the myocardium is extremely rare. Clinical progression is characterized by insidious onset, classically with a presentation with fever of unknown origin. Upon examination a pericardial friction rub may be auscultated. ECG changes consist of diffuse ST elevations, without reciprocal changes, T wave inversion, PR segment deviations. Typical changes as found in acute pericarditis (The PR-segment deviation and ST-segment elevation) are only found in roughly 10 % of cases ( Mayosi et al. 2005 ). Usually the rise in erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are less marked compared to the same parameters measured in viral or bacterial pericarditis. A chest X-ray may reveal left pleural effusion, however this is a non-specific finding. Echocardiogram is central in diagnosis, revealing effusion and if present, tamponade. Confirmation of diagnosis is by demonstration of AFB in the pericardial aspirate by smear. In pericardial TB the sensitivity of smear is 15–20 % and of mycobacterial culture 30–75 % ( Gooi and Smith 1978 ). The presence of cardiac tamponade is the most predictive sign of later development of constrictive pericarditis.

The optimal treatment duration remains uncertain, but suggested treatment regimens range from 6 to 12 months. The addition of corticosteroids as an adjuvant to prevent further accumulation of fluid and the development of constrictive pericarditis is recommended ( Fowler 1991 ; Mayosi et al. 2005 ). Open surgical drainage may be indicated to prevent tamponade, however little data exists on the benefit of closed percutaneous drainage ( Reuter et al. 2007 ).

3.3.6. Spinal Tuberculosis

Spinal TB can cause deformities, typically kyphosis, in extreme forming a gibbus, which can result in paraplegia. Depictions of sufferers are found originating from Ancient Egypt 5000 years ago. Since the late 18th century it became known as Pott’s disease. After haematogenous spread, tuberculous spondylitis develops, initially affecting a single vertebra, but with progressing of infection, softening may result in wedging or collapse of the vertebral body and subligamentous spread may involve adjacent vertebrae ( Jung et al. 2004 ). Cold abscesses formation or severe spinal angulation may cause compression of the spinal cord with neurological sequelae. In rare instances bacilli may be released into the subarachnoid space, leading to meningitis, or an abscess may drain externally with sinus formation ( Cheung and Luk 2013 ).

MRI is the imaging modality of choice ( Fig. 3.1c ) ( Jung et al. 2004 ). Evidence of pulmonary TB or other organ involvement, should heighten suspicion and provides an opportunity for the collection of samples for microbiological examination. Confirmation of diagnosis relies on the detection of AFB on CT-guided tissue biopsies or abscess aspirates. Treatment regimens are as for pulmonary TB, however some advocate longer duration of treatment. Based on the results of a series of randomized clinical trials conducted by the MRC Working party on TB of the spine, spanning a period of 15 year follow up, it is currently accepted that early and mild disease, without significant neurological deficits, may be treated conservatively with anti-tuberculous chemotherapy without operative intervention. Patients treated with debridement alone or combined with spinal fixation (with anterior strut graft) had the tendency to earlier resolution of abscesses, earlier bony fusion and less kyphotic deformity ( Mak and Cheung 2013 ). It is important to identify the poor prognostic factors that are associated with severe kyphosis development, such as the degree of vertebral body loss before treatment, and the separation of facet joints, to identify patients that would benefit for operative intervention by reducing kyphotic deformity.

3.3.7. Other Forms of Extra-Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Tuberculous arthritis, almost always affects only a single joint, usually the hip and knee. It can be diagnosed by examination of synovial fluid or synovial tissue biopsies. Gastrointestinal TB may mimic Crohn’s disease, both clinically and radiographically. Preferred sites are the ileocecum, ileum and jejunum and is usually associated with peritonitis. Barium contrast studies can reveal ulceration, strictures, bowel wall thickening, skip lesions and fistulae. In endemic countries, diagnosis is usually made on clinical suspicion. Biopsies may be useful in establishing the diagnosis ( Nagi et al. 2002 , 2003 ).

Urogenital TB is notoriously asymptomatic. TB of the urinary tract, occasionally causes flank pain or present with a renal or pelvic mass. Persistent “sterile” pyuria on urine analysis, especially early morning samples, require further investigation with urine AFB smear, PCR and culture. Further investigations include intravenous urography ( Merchant et al. 2013a , b ).

Laryngeal TB is one of the most infectious forms of TB. Sputum smear is reported positive in up to 70 % of cases. It can result from primary infection with infected droplet nuclei or secondary to pulmonary disease. Hoarseness and dysphagia can be among the presenting signs. Laryngeal TB can be primary, when bacilli directly invade the larynx or secondary from bronchial spread of advanced pulmonary TB ( Benwill and Sarria 2014 ). It presents with hoarseness and dysphagia, or chronic cough if associated with pulmonary TB ( Michael and Michael 2011 ). It should be differentiated from laryngeal malignancy. TB can potentially affect any organ in the human body, further discussion of all rare forms fall beyond the scope of this chapter.

All commercial rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.

This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Monographs, or book chapters, which are outputs of Wellcome Trust funding have been made freely available as part of the Wellcome Trust's open access policy

- Cite this Page Heemskerk D, Caws M, Marais B, et al. Tuberculosis in Adults and Children. London: Springer; 2015. Chapter 3, Clinical Manifestations.

- PDF version of this title (1.8M)

In this Page

- Primary Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- Extra-Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Other titles in this collection

- Wellcome Trust–Funded Monographs and Book Chapters

Recent Activity

- Clinical Manifestations - Tuberculosis in Adults and Children Clinical Manifestations - Tuberculosis in Adults and Children

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

COMMENTS

In primary pulmonary tuberculosis, the initial focus of infection can be located anywhere within the lung and has non-specific appearances ranging from too small to be detectable, to patchy areas of consolidation or even lobar consolidation. Radiographic evidence of parenchymal infection is seen in 70% of children and 90% of adults 1.

gas and this appears "blackest" on an x-ray (i.e., the least amount of x-ray absorption, therefore the greatest degree of x-ray transmission). Fat is slightly less dense than soft tissue and appears slightly darker than soft tissue. Note that soft tissue density includes numerous substances such as water, urine, blood, muscle, etc.—all of ...

Primary TB. There are no radiological features which are in themselves diagnostic of primary mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (TB) but a chest X-ray may provide some clues to the diagnosis. This image shows consolidation of the upper zone with ipsilateral hilar enlargement due to lymphadenopathy. These are typical features of primary TB.

Radiographic features. Primary pulmonary tuberculosis manifests as five main entities: parenchymal consolidation, often lower zone and typically subpleural 1,2. lymphadenopathy is often the dominant feature and the right hilar and paratracheal nodes are commonly affected 2. clustered parenchymal opacification may give a galaxy sign.

Summary. Chest X-rays are essential to the initial assessment and management of TB. They typically show characteristic features such as infiltrates, cavitation, pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy ...

Keywords: tuberculosis, chest imaging, children, X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging. 1. Introduction. ... AP chest radiograph of a child at presentation, who later was later confirmed to have pulmonary TB, demonstrates a right-sided lobulated cardio-mediastinal margin with filling of the right hilar point (white ...

Chest X-ray, chest CT and Ultrasound appearances of an organized effusion in a patient with post-primary TB. (A) Chest X-ray shows a right pulmonary opacity that is not in the gravity dependent location (red arrow). We are able to see the diaphragm medially (black arrow). ... and soft tissue of the chest wall. Typical presentations include ...

Chest X-ray (CXR) is a rapid imaging technique that allows lung abnormalities to be identified. CXR is used to diagnose conditions of the thoracic cavity, including the airways, ribs, lungs, heart and diaphragm. CXR has historically been one of the primary tools for detecting tuberculosis (TB), especially pulmonary TB.

USA.gov. 4. Chest X-Ray. The fourth component of a complete TB medical evaluation is a chest x-ray. A patient should have a chest x-ray if he or she has a positive blood test or skin test, or has signs and symptoms of TB disease, or been exposed to someone with TB disease. The chest x-ray is useful for diagnosing TB disease because TB disease ...

Chest tuberculosis (CTB) is a widespread problem, especially in our country where it is one of the leading causes of mortality. ... TB (PPT), each with corresponding radiological patterns, albeit with considerable overlap. The radiological features depend on age, underlying immune status, and prior exposure. Figure 1 depicts the natural history ...

OBJECTIVE. Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is a common worldwide infection and a medical and social problem causing high mortality and morbidity, especially in developing countries. The traditional imaging concept of primary and reactivation TB has been recently challenged, and radiologic features depend on the level of host immunity rather than the elapsed time after the infection. We aimed to ...

TB in HIV-AIDS presents with a primary pattern; immune compromise means that the body responds as if it is a first exposure. miliary disease is common. investigation. chest X-ray. sputum sample. Ziehl-Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli. culture for confirmation of diagnosis and sensitivity testing. blood tests. interferon gamma release assay ...

Tuberculosis creates cavities visible in x-rays like this one in the patient's right upper lobe. A posterior-anterior (PA) chest X-ray is the standard view used; other views (lateral or lordotic) or CT scans may be necessary. [citation needed] In active pulmonary TB, infiltrates or consolidations and/or cavities are often seen in the upper ...

TB disease is diagnosed by medical history, physical examination, chest x-ray, and other laboratory tests. TB disease is treated by taking several drugs as recommended by a health care provider. TB disease should be suspected in persons who have any of the following symptoms: Unexplained weight loss. Loss of appetite.

Radiological presentation of TB may be variable but in many cases is quite characteristic. Radiology also provides essential information for management and follow-up of these patients and is extremely valuable for monitoring complications. Chest X-ray is useful but is not specific for diagnosing pulmonary TB, and can be normal even when the ...

Figure 1: Chest x-ray showing dense homogenous opacity in right, middle and lower lobe of primary pulmonary TB. View Figure 1. Figure 2: Chest x-ray showing bilateral hilar adenopathy of primary pulmonary TB. View Figure 2. Figure 3: Chest x-ray showing patchy opacification on the upper right and mid-zone lung with fibrotic shadows, both hilar ...

A positive TB skin test or TB blood test only tells that a person has been infected with TB bacteria. It does not tell whether the person has latent TB infection (LTBI) or has progressed to TB disease. Other tests, such as a chest x-ray and a sample of sputum, are needed to see whether the person has TB disease. Diagnosis

Presentation This patient, a 60-year-old male presented with difficulty breathing, pain on the right side of chest and dry cough on and off. Past history: Taken ATT 8 years back for pulmonary TB with possibly pleural effusion. Documents not available but the patient describes both parenchymal disease as well as pleural effusion. The patient's ...

Miliary TB may be accompanied by consolidation (30 %), parenchymal lung cavities (3-12 %), or mediastinal and/or hilar lymphadenopathy (15 %) on chest X-ray (Sharma et al. 2005). A missed diagnosis is grave, as untreated miliary TB often leads to TB meningitis and can be rapidly fatal.

Basics of Diagnostic X‐ray Physics • X‐rays are directed at the patient and variably absorbed - When not absorbed • Pass through patient & strike the x‐ray film or - When completely absorbed • Don't strike x‐ray film or - When scattered • Some strike the x‐ray film.

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic lung disease that occurs due to bacterial infection and is one of the top 10 leading causes of death. Accurate and early detection of TB is very important, otherwise, it could be life-threatening. In this work, we have detected TB reliably from the chest X-ray images using image pre-processing, data augmentation, image segmentation, and deep-learning ...