Using Conceptual Scaffolding to Foster Effective Problem Solving

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Lin Ding , Neville Reay , Albert Lee , Lei Bao; Using Conceptual Scaffolding to Foster Effective Problem Solving. AIP Conf. Proc. 5 November 2009; 1179 (1): 129–132. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3266695

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Traditional end‐of‐chapter problems often are localized, requiring formulas only within a single chapter. Students frequently can solve these problems by performing “plug‐and‐chug” without recognizing underlying concepts. We designed open‐ended problems that require a synthesis of concepts that are broadly separated in the teaching time line, militating against students’ blindly invoking locally introduced formulas. Each problem was encapsulated into a sequence with two preceding conceptually‐based multiple‐choice questions. These conceptual questions address the same underlying concepts as the subsequent problem, providing students with guided conceptual scaffolding. When solving the problem, students were explicitly advised to search for underlying connections based on the conceptual questions. Both small‐scale interviews and a large‐scale written test were conducted to investigate the effects of guided conceptual scaffolding on student problem solving. Specifically, student performance on the open‐ended problems was compared between those who received scaffolding and those who did not. A further analysis of whether the conceptual scaffolding was equivalent to mere cueing also was conducted.

Sign in via your Institution

Citing articles via, publish with us - request a quote.

Sign up for alerts

- Online ISSN 1551-7616

- Print ISSN 0094-243X

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

- Distance Learning

- Print Resource Orders

Subscribe to our Creative Problem Solving Online Learning Course today!

About problem solving styles.

Knowledge of style is important in education in a number of ways. It contributes to adults’ ability to work together effectively in teams and in large groups. It provides information that helps educators understand their own personal strengths and how to put them to work as effectively as possible across many tasks and challenges. It helps educators communicate more effectively with each other, but also with parents, community members, and, of course, with students. In addition to its importance for adults, style can also be important in designing and differentiating instruction.

The VIEW Model

Our approach to problem solving style (the VIEW model) represents and assesses three dimensions and six specific styles that are unique and important in understanding and guiding the efforts of individuals and groups to manage their creative problem solving and change management as effectively as possible.

Orientation to Change

The first VIEW dimension involves your preferences in two general styles for managing change and solving problems creatively. We identify this as “Orientation to Change;” its two contrasting styles are the “Explorer” and the “Developer.” Explorers thrive on and seek out novelty and original ideas (“thinking out of the box”), and they may find externally imposed procedures and structures confining and limiting to their imagination and energy. Developers are concerned with practical applications and the reality of the task, and they use their creative and critical thinking in ways that are clearly recognized by others as being helpful and valuable. They’re good at finding workable possibilities and guiding them to successful implementation. They are creative in “thinking better inside the box.”

Manner of Processing

The second dimension of VIEW, Manner of Processing describes the person’s preference for working externally (i.e., with other people throughout the process) or internally (i.e., thinking and working alone before sharing ideas with others) when managing change and solving problems.

Ways of Deciding

The third dimension of VIEW describes the major emphasis the person gives to people (i.e., maintaining harmony and interpersonal relationships) or to tasks (i.e., emphasizing logical, rational, and appropriate decisions) when making decisions during problem solving or when managing change.

Through our research and development efforts, our instrument, VIEW: An Assessment of Problem Solving Style, translates the VIEW model of style into measurable dimensions. The VIEW assessment is a practical and useful tool for anyone who wishes to understand his or her own approach to change or problem solving. Contact us for more information about the VIEW instrument.

Practical Applications of VIEW

Understanding problem solving styles can be helpful in many ways to individuals, teams, small groups, and organizations. VIEW: An Assessment of Problem Solving Style is a carefully researched, but simple and easy-to-use tool that can enable people to understand their style preferences and to use that knowledge in many powerful ways. These pages illustrate briefly a variety of practical applications of the VIEW assessment that cut across many settings or contexts (including, for example: large, global organizations; smaller business and professional settings; educational institutions, hospitals, religious organizations, arts organizations, or other non-profits). VIEW can be a valuable tool for individuals who are concerned with understanding their personal style preferences and improving their problem solving effectiveness, for teams or groups who need to work together successfully, and to organizations in their efforts to build a constructive work climate, to recognize and value diversity, and to manage change for long-term success. Click on any of the following ten applications of VIEW to see examples for that area. (You may also click here to Download a PDF file with all the applications examples in one file.)

- Improving Problem Solving

- Communicating Effectively

- Enhancing Personal Productivity

- Providing and Receiving Feedback

- Facilitating Groups

- Managing Change

- Developing Leadership

- Designing Instruction

- Building Teams

- Coaching and Mentoring

Free Resources

Click here to find a number of free resources that will explain CPS, to obtain articles that deal with both research and practice, and to obtain an extensive bibliography to give you direction for future reading and study.

Online Resources:

Click here for advanced online resources in PDF format that deal with applications of the VIEW Problem Solving Style model. These resources are available at a reasonable cost for immediate download. The cost of each one includes permission to duplicate the file for up to three other individuals at no additional charge.

Distance Learning Resources:

Click here for information about our extensive (newly revised and updated) distance learning modules on CPS.

Print Resources:

We also have print publications about problem-solving style that you can purchase. Click here to view those publications.

Workshops, Training, Consulting Services:

Our CPS programs and services are custom-tailored to meet your needs and interests. We will confer with you, create a complete proposal to meet your unique needs, and work closely with you to carry out our collaborative plan. Click here for more.

We believe that all people have strengths and talents that are important to recognize, develop, and use throughout life. Read more.

- https://sodo-group.com

- s999 casino

- sodo casino

- link sodo66

- trang chu sodo66

- 79sodo đăng nhập

- nhà cái s666

- BONG DA LUUU

- CV88 CASINO

- ZM88 TẶNG 100K

- VZ99 TẶNG 100K

- QH88 TẶNG 100K

- xổ số miền bắc 500 ngày

- nhà cái J88

- nhà cái SV88

- BAYVIP club

- KEN88 game bài

- nhà cái 6BET

- nhà cái 8DAY

- lô khung 1 ngày

- dàn de 16 số khung 5 ngày

- bạch thủ kép

- kèo nhà cái hôm nay

- nhà cái 8kbet

- lk88 casino

- BETLV casino

- trực tiếp 3s

- soi kèo ngoại hạng anh

- https://vj9999.site

- https://uw88.online

- https://vwinbets.com

- xổ số đại phát

- xổ số miền bắc đại phát

- xổ số miền nam đại phát

- kqxs đại phát

- xổ số thiên phú

- Xổ số phương trang

- linkviva88.net

- đăng ký w88

- casino trực tuyến uy tín

- tải game tài xỉu online

- xoc dia online

- top nhà cái uy tín

- nhà cái uy tín

- sp666 casino

- nhà cái bwing

- nha cai tk88

- https://tk886.com

- trang chu sodo

- nhà cái mb88

- app baby live

- app tiktok live

- https://one88vn.net/

- https://vb68.live/

- https://nhacaivb68.org/

- https://vb68.info/

- https://vb68.one/

- https://mu88gamebai.com/

- https://dulieunhacai.com/

- https://vn89nhacai.com/

- https://tk88vnd.com/

- https://tk88a.org/

- https://tk88pro.net/

- https://tk88a.net/

- https://tk88viet.com/

- https://tk88viet.org/

- https://tk88vietnam.com/

- https://tk88vietnam.org/

- https://kimsa88no1.com/

- https://sm66link.com/

- https://bet168no1.com/

- https://tk860.com/

- https://richditch.com/

- https://zb-bet.com/

- https://vivanau.net/

- https://fiyrra.com/

- https://tf88vn.fun/

- https://365rrd.com/

- https://78wed.com/

- https://ee8881.com/

- https://tk66live.live/

- https://qh888.net/

- https://funews.net/

- https://rodball.com/

- https://shbenqi.com/

- https://888wpc.com/

- https://3344ys.com/

- https://m88q.com/

- https://w88ap.net/

- https://jun-room.com/

- https://me8e.com/

- https://xsvwines.com/

- https://fbk8.com/

- https://jbohm.com/

- https://scotlandroyalty.org/

- https://newsbd7.com/

- skylush.net

- https://123bno1.com/

- https://188betno1.com/

- https://789betno1.com/

- https://78winno1.com/

- https://79sodono1.com/

- https://bet66no1.com/

- https://ttk86.com/

- https://hr99link.com/

- https://lixi88no1.com/

- https://mu88link.com/

- https://mu88no1.com/

- https://qh88link.com/

- https://qh88no1.com/

- https://s666no1.com/

- https://sm66no1.com/

- https://sodo66no1.com/

- https://vb138betno1.com/

- https://vx88no1.com/

- link sodo casino

- nhà cái jbo

- link ole777

- đăng ký vz99

- xổ số miền bắc minh chính

- sm66 nha cai

- soi cầu xổ số miền bắc

- trực tiếp kết quả xổ số

- lô đề online

- d9bet casino

- nhà cái pog79

- tỷ số trực tuyến 7m

- link vao fb88

- nha cai 188bet

- nha cai vn88

- nha cai m88

- trang chủ 789bet

- bet88vn.net

- soi kèo world cup 2022

- nhà cái bet88

- https://xocdia.biz/

- soi cầu xổ số

- fb88next.com

- fb88thai.com

Leadership Team

Our work builds on more than five decades of research, development, and practical experience in organizations. Learn more about our team .

Contact Information

Center for Creative Learning, LLC 2015 Grant Place Melbourne, Florida, 32901 USA Email: [email protected]

- deneme bonusu veren siteler

- geres-cambodia.org

- capitalhillrealty.net

- bahis siteleri

- johnacarroll.com ile En güvenilir deneme bonusu veren bahis siteleri listesine erişin.

- beautyskinlaserga.com ile 2024 yeni deneme bonusu veren siteler listesine erişin.

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 10 August 2016

Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model

- John A C Hattie 1 &

- Gregory M Donoghue 1

npj Science of Learning volume 1 , Article number: 16013 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

169k Accesses

178 Citations

681 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social sciences

The purpose of this article is to explore a model of learning that proposes that various learning strategies are powerful at certain stages in the learning cycle. The model describes three inputs and outcomes (skill, will and thrill), success criteria, three phases of learning (surface, deep and transfer) and an acquiring and consolidation phase within each of the surface and deep phases. A synthesis of 228 meta-analyses led to the identification of the most effective strategies. The results indicate that there is a subset of strategies that are effective, but this effectiveness depends on the phase of the model in which they are implemented. Further, it is best not to run separate sessions on learning strategies but to embed the various strategies within the content of the subject, to be clearer about developing both surface and deep learning, and promoting their associated optimal strategies and to teach the skills of transfer of learning. The article concludes with a discussion of questions raised by the model that need further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

The science of effective learning with spacing and retrieval practice

Shana K. Carpenter, Steven C. Pan & Andrew C. Butler

Profiles of learners based on their cognitive and metacognitive learning strategy use: occurrence and relations with gender, intrinsic motivation, and perceived autonomy support

Diana Kwarikunda, Ulrich Schiefele, … Joseph Ssenyonga

What makes the difference? An empirical comparison of critical aspects identified in phenomenographic and variation theory analyses

Mona Holmqvist & Per Selin

There has been a long debate about the purpose of schooling. These debates include claims that schooling is about passing on core notions of humanity and civilisation (or at least one’s own society’s view of these matters). They include claims that schooling should prepare students to live pragmatically and immediately in their current environment, should prepare students for the work force, should equip students to live independently, to participate in the life of their community, to learn to ‘give back’, to develop personal growth. 1

In the past 30 years, however, the emphasis in many western systems of education has been more on enhancing academic achievement—in domains such as reading, mathematics, and science—as the primary purpose of schooling. 2 Such an emphasis has led to curricula being increasingly based on achievement in a few privileged domains, and ‘great’ students are deemed those who attain high levels of proficiency in these narrow domains.

This has led to many countries aiming to be in the top echelon of worldwide achievement measures in a narrow range of subjects; for example, achievement measures such as PISA (tests of 15-year olds in mathematics, reading and science, across 65 countries in 2012) or PIRLS (Year-5 tests of mathematics, reading and science, across 57 countries in 2011). Indeed, within most school systems there is a plethora of achievement tests; many countries have introduced accountability pressures based on high levels of testing of achievement; and communities typically value high achievement or levels of knowledge. 3 The mantra underpinning these claims has been cast in terms of what students know and are able to do; the curriculum is compartmentalised into various disciplines of achievement; and students, teachers, parents and policy makers talk in terms of success in these achievement domains.

Despite the recent emphasis on achievement, the day-to-day focus of schools has always been on learning—how to know, how to know more efficiently and how to know more effectively. The underlying philosophy is more about what students are now ready to learn, how their learning can be enabled, and increasing the ‘how to learn’ proficiencies of students. In this scenario, the purpose of schooling is to equip students with learning strategies, or the skills of learning how to learn. Of course, learning and achievement are not dichotomous; they are related. 4 Through growth in learning in specific domains comes achievement and from achievement there can be much learning. The question in this article relates to identifying the most effective strategies for learning.

In our search, we identified >400 learning strategies: that is, those processes which learners use to enhance their own learning. Many were relabelled versions of others, some were minor modifications of others, but there remained many contenders purported to be powerful learning strategies. Such strategies help the learner structure his or her thinking so as to plan, set goals and monitor progress, make adjustments, and evaluate the process of learning and the outcomes. These strategies can be categorised in many ways according to various taxonomies and classifications (e.g., references 5 , 6 , 7 ). Boekaerts, 8 for example, argued for three types of learning strategies: (1) cognitive strategies such as elaboration, to deepen the understanding of the domain studied; (2) metacognitive strategies such as planning, to regulate the learning process; and (3) motivational strategies such as self-efficacy, to motivate oneself to engage in learning. Given the advent of newer ways to access information (e.g., the internet) and the mountain of information now at students’ fingertips, it is appropriate that Dignath, Buettner and Langfeldt 9 added a fourth category—management strategies such as finding, navigating, and evaluating resources.

But merely investigating these 400-plus strategies as if they were independent is not defensible. Thus, we begin with the development of a model of learning to provide a basis for interpreting the evidence from our meta-synthesis. The argument is that learning strategies can most effectively enhance performance when they are matched to the requirements of tasks (cf. 10 ).

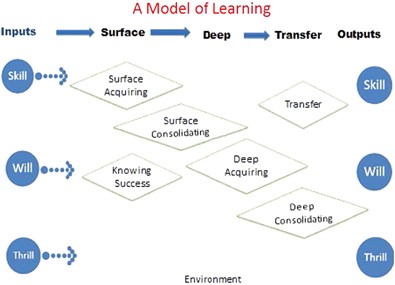

A model of learning

The model comprises the following components: three inputs and three outcomes; student knowledge of the success criteria for the task; three phases of the learning process (surface, deep and transfer), with surface and deep learning each comprising an acquisition phase and a consolidation phase; and an environment for the learning ( Figure 1 ). We are proposing that various learning strategies are differentially effective depending on the degree to which the students are aware of the criteria of success, on the phases of learning process in which the strategies are used, and on whether the student is acquiring or consolidating their understanding. The following provides an overview of the components of the model (see reference 11 for a more detailed explanation of the model).

A model of learning.

Input and outcomes

The model starts with three major sources of inputs: the skill, the will and the thrill. The ‘skill’ is the student’s prior or subsequent achievement, the ‘will’ relates to the student’s various dispositions towards learning, and the ‘thrill’ refers to the motivations held by the student. In our model, these inputs are also the major outcomes of learning. That is, developing outcomes in achievement (skill) is as valuable as enhancing the dispositions towards learning (will) and as valuable as inviting students to reinvest more into their mastery of learning (thrill or motivations).

The first component describes the prior achievement the student brings to the task. As Ausubel 12 claimed ‘if I had to reduce all of educational psychology to just one principle, I would say this ‘The most important single factor influencing learning is what the leaner already knows. Ascertain this and teach him accordingly. Other influences related to the skills students bring to learning include their working memory, beliefs, encouragement and expectations from the student’s cultural background and home.

Dispositions are more habits of mind or tendencies to respond to situations in certain ways. Claxton 13 claimed that the mind frame of a ‘powerful learner’ is based on the four major dispositions: resilience or emotional strength, resourcefulness or cognitive capabilities, reflection or strategic awareness, and relating or social sophistication. These dispositions involve the proficiency to edit, select, adapt and respond to the environment in a recurrent, characteristic manner. 14 But dispositions alone are not enough. Perkins et al. 15 outlined a model with three psychological components which must be present in order to spark dispositional behaviour: sensitivity—the perception of the appropriateness of a particular behaviour; inclination—the felt impetus toward a behaviour; and ability—the basic capacity and confidence to follow through with the behaviour.

There can be a thrill in learning but for many students, learning in some domains can be dull, uninviting and boring. There is a huge literature on various motivational aspects of learning, and a smaller literature on how the more effective motivational aspects can be taught. A typical demarcation is between mastery and performance orientations. Mastery goals are seen as being associated with intellectual development, the acquisition of knowledge and new skills, investment of greater effort, and higher-order cognitive strategies and learning outcomes. 16 Performance goals, on the other hand, have a focus on outperforming others or completing tasks to please others. A further distinction has been made between approach and avoidance performance goals. 17 – 19 The correlations of mastery and performance goals with achievement, however, are not as high as many have claimed. A recent meta-analysis found 48 studies relating goals to achievement (based on 12,466 students), and the overall correlation was 0.12 for mastery and 0.05 for performance goals on outcomes. 20 Similarly, Hulleman et al. 21 reviewed 249 studies ( N =91,087) and found an overall correlation between mastery goal and outcomes of 0.05 and performance goals and outcomes of 0.14. These are small effects and show the relatively low importance of these motivational attributes in relation to academic achievement.

An alternative model of motivation is based on Biggs 22 learning processes model, which combines motivation (why the student wants to study the task) and their related strategies (how the student approaches the task). He outlined three common approaches to learning: deep, surface and achieving. When students are taking a deep strategy, they aim to develop understanding and make sense of what they are learning, and create meaning and make ideas their own. This means they focus on the meaning of what they are learning, aim to develop their own understanding, relate ideas together and make connections with previous experiences, ask themselves questions about what they are learning, discuss their ideas with others and compare different perspectives. When students are taking a surface strategy, they aim to reproduce information and learn the facts and ideas—with little recourse to seeing relations or connections between ideas. When students are using an achieving strategy, they use a ‘minimax’ notion—minimum amount of effort for maximum return in terms of passing tests, complying with instructions, and operating strategically to meet a desired grade. It is the achieving strategy that seems most related to school outcomes.

Success criteria

The model includes a prelearning phase relating to whether the students are aware of the criteria of success in the learning task. This phase is less about whether the student desires to attain the target of the learning (which is more about motivation), but whether he or she understands what it means to be successful at the task at hand. When a student is aware of what it means to be successful before undertaking the task, this awareness leads to more goal-directed behaviours. Students who can articulate or are taught these success criteria are more likely to be strategic in their choice of learning strategies, more likely to enjoy the thrill of success in learning, and more likely to reinvest in attaining even more success criteria.

Success criteria can be taught. 23 , 24 Teachers can help students understand the criteria used for judging the students’ work, and thus teachers need to be clear about the criteria used to determine whether the learning intentions have been successfully achieved. Too often students may know the learning intention, but do not how the teacher is going to judge their performance, or how the teacher knows when or whether students have been successful. 25 The success criteria need to be as clear and specific as possible (at surface, deep, or transfer level) as this enables the teacher (and learner) to monitor progress throughout the lesson to make sure students understand and, as far as possible, attain the intended notions of success. Learning strategies that help students get an overview of what success looks like include planning and prediction, having intentions to implement goals, setting standards for judgement success, advance organisers, high levels of commitment to achieve success, and knowing about worked examples of what success looks like. 23

Environment

Underlying all components in the model is the environment in which the student is studying. Many books and internet sites on study skills claim that it is important to attend to various features of the environment such as a quiet room, no music or television, high levels of social support, giving students control over their learning, allowing students to study at preferred times of the day and ensuring sufficient sleep and exercise.

The three phases of learning: surface, deep and transfer

The model highlights the importance of both surface and deep learning and does not privilege one over the other, but rather insists that both are critical. Although the model does seem to imply an order, it must be noted that these are fuzzy distinctions (surface and deep learning can be accomplished simultaneously), but it is useful to separate them to identify the most effective learning strategies. More often than not, a student must have sufficient surface knowledge before moving to deep learning and then to the transfer of these understandings. As Entwistle 26 noted, ‘The verb ‘to learn’ takes the accusative’; that is, it only makes sense to analyse learning in relation to the subject or content area and the particular piece of work towards which the learning is directed, and also the context within which the learning takes place. The key debate, therefore, is whether the learning is directed content that is meaningful to the student, as this will directly affect student dispositions, in particular a student’s motivation to learn and willingness to reinvest in their learning.

A most powerful model to illustrate this distinction between surface and deep is the structure of observed learning outcomes, or SOLO, 27 , 28 as discussed above. The model has four levels: unistructural, multistructural, relational and extended abstract. A unistructural intervention is based on teaching or learning one idea, such as coaching one algorithm, training in underlining, using a mnemonic or anxiety reduction. The essential feature is that this idea alone is the focus, independent of the context or its adaption to or modification by content. A multistructural intervention involves a range of independent strategies or procedures, but without integrating or orchestration as to the individual differences or demands of content or context (such as teaching time management, note taking and setting goals with no attention to any strategic or higher-order understandings of these many techniques). Relational interventions involve bringing together these various multistructural ideas, and seeing patterns; it can involve the strategies of self-monitoring and self-regulation. Extended abstract interventions aim at far transfer (transfer between contexts that, initally, appear remote to one another) such that they produce structural changes in an individual’s cognitive functioning to the point where autonomous or independent learning can occur. The first two levels (one then many ideas) refer to developing surface knowing and the latter two levels (relate and extend) refer to developing deeper knowing. The parallel in learning strategies is that surface learning refers to studying without much reflecting on either purpose or strategy, learning many ideas without necessarily relating them and memorising facts and procedures routinely. Deep learning refers to seeking meaning, relating and extending ideas, looking for patterns and underlying principles, checking evidence and relating it to conclusions, examining arguments cautiously and critically, and becoming actively interested in course content (see reference 29 ).

Our model also makes a distinction between first acquiring knowledge and then consolidating it. During the acquisition phase, information from a teacher or instructional materials is attended to by the student and this is taken into short-term memory. During the consolidation phase, a learner then needs to actively process and rehearse the material as this increases the likelihood of moving that knowledge to longer-term memory. At both phases there can be a retrieval process, which involves transferring the knowing and understanding from long-term memory back into short-term working memory. 30 , 31

Acquiring surface learning

In their meta-analysis of various interventions, Hattie et al. 32 found that many learning strategies were highly effective in enhancing reproductive performances (surface learning) for virtually all students. Surface learning includes subject matter vocabulary, the content of the lesson and knowing much more. Strategies include record keeping, summarisation, underlining and highlighting, note taking, mnemonics, outlining and transforming, organising notes, training working memory, and imagery.

Consolidating surface learning

Once a student has begun to develop surface knowing it is then important to encode it in a manner such that it can retrieved at later appropriate moments. This encoding involves two groups of learning strategies: the first develops storage strength (the degree to which a memory is durably established or ‘well learned’) and the second develops strategies that develop retrieval strength (the degree to which a memory is accessible at a given point in time). 33 ‘Encoding’ strategies are aimed to develop both, but with a particular emphasis on developing retrieval strength. 34 Both groups of strategies invoke an investment in learning, and this involves ‘the tendency to seek out, engage in, enjoy and continuously pursue opportunities for effortful cognitive activity. 35 Although some may not ‘enjoy’ this phase, it does involve a willingness to practice, to be curious and to explore again, and a willingness to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty during this investment phase. In turn, this requires sufficient metacognition and a calibrated sense of progress towards the desired learning outcomes. Strategies include practice testing, spaced versus mass practice, teaching test taking, interleaved practice, rehearsal, maximising effort, help seeking, time on task, reviewing records, learning how to receive feedback and deliberate practice (i.e., practice with help of an expert, or receiving feedback during practice).

Acquiring deep learning

Students who have high levels of awareness, control or strategic choice of multiple strategies are often referred to as ‘self-regulated’ or having high levels of metacognition. In Visible Learning , Hattie 36 described these self-regulated students as ‘becoming like teachers’, as they had a repertoire of strategies to apply when their current strategy was not working, and they had clear conceptions of what success on the task looked like. 37 More technically, Pintrich et al. 38 described self-regulation as ‘an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate and control their cognition, motivation and behaviour, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features in the environment’. These students know the what, where, who, when and why of learning, and the how, when and why to use which learning strategies. 39 They know what to do when they do not know what to do. Self-regulation strategies include elaboration and organisation, strategy monitoring, concept mapping, metacognitive strategies, self-regulation and elaborative interrogation.

Consolidating deep learning

Once a student has acquired surface and deep learning to the extent that it becomes part of their repertoire of skills and strategies, we may claim that they have ‘automatised’ such learning—and in many senses this automatisation becomes an ‘idea’, and so the cycle continues from surface idea to deeper knowing that then becomes a surface idea, and so on. 40 There is a series of learning strategies that develop the learner’s proficiency to consolidate deeper thinking and to be more strategic about learning. These include self-verbalisation, self-questioning, self-monitoring, self-explanation, self-verbalising the steps in a problem, seeking help from peers and peer tutoring, collaborative learning, evaluation and reflection, problem solving and critical thinking techniques.

There are skills involved in transferring knowledge and understanding from one situation to a new situation. Indeed, some have considered that successful transfer could be thought as synonymous with learning. 41 , 42 There are many distinctions relating to transfer: near and far transfer, 43 low and high transfer, 44 transfer to new situations and problem solving transfer, 5 and positive and negative transfer. 45 Transfer is a dynamic, not static, process that requires learners to actively choose and evaluate strategies, consider resources and surface information, and, when available, to receive or seek feedback to enhance these adaptive skills. Reciprocal teaching is one program specifically aiming to teach these skills; for example, Bereiter and Scardamalia 46 have developed programs in the teaching of transfer in writing, where students are taught to identify goals, improve and elaborate existing ideas, strive for idea cohesion, present their ideas to groups and think aloud about how they might proceed. Similarly, Schoenfeld 47 outlined a problem-solving approach to mathematics that involves the transfer of skills and knowledge from one situation to another. Marton 48 argued that transfer occurs when the learner learns strategies that apply in a certain situation such that they are enabled to do the same thing in another situation when they realise that the second situation resembles (or is perceived to resemble) the first situation. He claimed that not only sameness, similarity, or identity might connect situations to each other, but also small differences might connect them as well. Learning how to detect such differences is critical for the transfer of learning. As Heraclitus claimed, no two experiences are identical; you do not step into the same river twice.

Overall messages from the model

There are four main messages to be taken from the model. First, if the success criteria is the retention of accurate detail (surface learning) then lower-level learning strategies will be more effective than higher-level strategies. However, if the intention is to help students understand context (deeper learning) with a view to applying it in a new context (transfer), then higher level strategies are also needed. An explicit assumption is that higher level thinking requires a sufficient corpus of lower level surface knowledge to be effective—one cannot move straight to higher level thinking (e.g., problem solving and creative thought) without sufficient level of content knowledge. Second, the model proposes that when students are made aware of the nature of success for the task, they are more likely to be more involved in investing in the strategies to attain this target. Third, transfer is a major outcome of learning and is more likely to occur if students are taught how to detect similarities and differences between one situation and a new situation before they try to transfer their learning to the new situation. Hence, not one strategy may necessarily be best for all purposes. Fourth, the model also suggests that students can be advantaged when strategy training is taught with an understanding of the conditions under which the strategy best works—when and under what circumstance it is most appropriate.

The current study

The current study synthesises the many studies that have related various learning strategies to outcomes. This study only pertains to achievement outcomes (skill, on the model of learning); further work is needed to identify the strategies that optimise the dispositions (will) and the motivation (thrill) outcomes. The studies synthesised here are from four sources. First, there are the meta-analyses among the 1,200 meta-analyses in Visible Learning that relate to strategies for learning. 36 , 49 , 50 Second, there is the meta-analysis conducted by Lavery 51 on 223 effect-sizes derived from 31 studies relating to self-regulated learning interventions. The third source is two major meta-analyses by a Dutch team of various learning strategies, especially self-regulation. And the fourth is a meta-analysis conducted by Donoghue et al. 52 based on a previous analysis by Dunlosky et al. 53

The data in Visible Learning is based on 800 meta-analyses relating influences from the home, school, teacher, curriculum and teaching methods to academic achievement. Since its publication in 2009, the number of meta-analyses now exceeds 1,200, and those influences specific to learning strategies are retained in the present study. Lavery 51 identified 14 different learning strategies and the overall effect was 0.46—with greater effects for organising and transforming (i.e., deliberate rearrangement of instructional materials to improve learning, d =0.85) and self-consequences (i.e., student expectation of rewards or punishment for success or failure, d =0.70). The lowest effects were for imagery (i.e., creating or recalling vivid mental images to assist learning, d =0.44) and environmental restructuring (i.e., efforts to select or arrange the physical setting to make learning easier, d =0.22). She concluded that the higher effects involved ‘teaching techniques’ and related to more ‘deep learning strategies’, such as organising and transforming, self-consequences, self-instruction, self-evaluation, help-seeking, keeping records, rehearsing/memorising, reviewing and goal-setting. The lower ranked strategies were more ‘surface learning strategies’, such as time management and environmental restructuring.

Of the two meta-analyses conducted by the Dutch team, the first study, by Dignath et al. 9 analysed 357 effects from 74 studies ( N =8,619). They found an overall effect of 0.73 from teaching methods of self-regulation. The effects were large for achievement (elementary school, 0.68; high school, 0.71), mathematics (0.96, 1.21), reading and writing (0.44, 0.55), strategy use (0.72, 0.79) and motivation (0.75, 0.92). In the second study, Donker et al. 54 reviewed 180 effects from 58 studies relating to self-regulation training, reporting an overall effect of 0.73 in science, 0.66 in mathematics and 0.36 in reading comprehension. The most effective strategies were cognitive strategies (rehearsal 1.39, organisation 0.81 and elaboration 0.75), metacognitive strategies (planning 0.80, monitoring 0.71 and evaluation 0.75) and management strategies (effort 0.77, peer tutoring 0.83, environment 0.59 and metacognitive knowledge 0.97). Performance was almost always improved by a combination of strategies, as was metacognitive knowledge. This led to their conclusion that students should not only be taught which strategies to use and how to apply them (declarative knowledge or factual knowledge) but also when (procedural or how to use the strategies) and why to use them (conditional knowledge or knowing when to use a strategy).

Donoghue et al. 52 conducted a meta-analysis based on the articles referenced in Dunlosky et al. 53 They reviewed 10 learning strategies and a feature of their review is a careful analysis of possible moderators to the conclusions about the effectiveness of these learning strategies, such as learning conditions (e.g., study alone or in groups), student characteristics (e.g., age, ability), materials (e.g., simple concepts to problem-based analyses) and criterion tasks (different outcome measures).

In the current study, we independently assigned all strategies to the various parts of the model—this was a straightforward process, and the few minor disagreements were resolved by mutual agreement. All results are presented in Appendix 1.

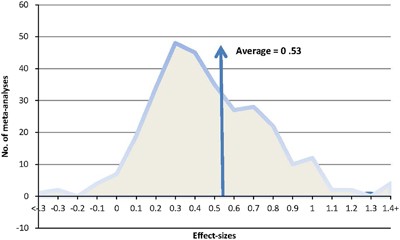

Results: the meta-synthesis of learning strategies

There are 302 effects derived from the 228 meta-analyses from the above four sources that have related some form of learning strategy to an achievement outcome. Most are experimental–control studies or pre–post studies, whereas some are correlations ( N =37). There are 18,956 studies (although some may overlap across meta-analyses). Only 125 meta-analyses reported the sample size ( N =11,006,839), but if the average (excluding the outlier 7 million from one meta-analysis) is used for the missing sample sizes, the best estimate of sample size is between 13 and 20 million students.

The average effect is 0.53 but there is considerable variance ( Figure 2 ), and the overall number of meta-analyses, studies, number of people (where provided), effects and average effect-sizes for the various phases of the model are provided in Table 1 . The effects are lowest for management of the environment and ‘thrill’ (motivation), and highest for developing success criteria across the learning phases. The variance is sufficiently large, however, that it is important to look at specific strategies within each phase of the model.

The average and the distribution of all effect sizes.

Synthesis of the input phases of the model

The inputs: skills.

There are nine meta-analyses that have investigated the relation between prior achievement and subsequent achievement, and not surprisingly these relations are high ( Table 2 ). The average effect-size is 0.77 (s.e.=0.10), which translates to a correlation of 0.36—substantial for any single variable. The effects of prior achievement are lowest in the early years, and highest from high school to university. One of the purposes of school, however, is to identify those students who are underperforming relative to their abilities and thus to not merely accept prior achievement as destiny. The other important skill is working memory—which relates to the amount of information that can be retained in short-term working memory when engaged in processing, learning, comprehension, problem solving or goal-directed thinking. 55 Working memory is strongly related to a person’s ability to reason with novel information (i.e., general fluid intelligence. 56

The inputs: will

There are 28 meta-analyses related to the dispositions of learning from 1,304 studies and the average effect-size is 0.48 (s.e.=0.09; Table 3 ). The effect of self-efficacy is highest ( d =0.90), followed by increasing the perceived value of the task ( d = 0.46), reducing anxiety ( d =0.45) and enhancing the attitude to the content ( d =0.35). Teachers could profitably increase students’ levels of confidence and efficacy to tackle difficult problems; not only does this increase the probability of subsequent learning but it can also help reduce students’ levels of anxiety. It is worth noting the major movement in the anxiety and stress literature in the 1980s moved from a preoccupation on understanding levels of stress to providing coping strategies—and these strategies were powerful mediators in whether people coped or not. 57 Similarly in learning, it is less the levels of anxiety and stress but the development of coping strategies to deal with anxiety and stress. These strategies include being taught to effectively regulate negative emotions; 58 increasing self-efficacy, which relates to developing the students conviction in their own competence to attain desired outcomes; 59 focusing on the positive skills already developed; increasing social support and help seeking; reducing self-blame; and learning to cope with error and making mistakes. 60 Increasing coping strategies to deal with anxiety and promoting confidence to tackle difficult and challenging learning tasks frees up essential cognitive resources required for the academic work.

There has been much discussion about students having growth—or incremental—mindsets (human attributes are malleable not fixed) rather than fixed mindsets (attributes are fixed and invariant). 61 However, the evidence in Table 3 ( d =0.19) shows how difficult it is to change to growth mindsets, which should not be surprising as many students work in a world of schools dominated by fixed notions—high achievement, ability groups, and peer comparison.

The inputs: thrill

The thrill relates to the motivation for learning: what is the purpose or approach to learning that the student adopts? Having a surface or performance approach motivation (learning to merely pass tests or for short-term gains) or mastery goals is not conducive to maximising learning, whereas having a deep or achieving approach or motivation is helpful ( Table 4 ). A possible reason why mastery goals are not successful is that too often the outcomes of tasks and assessments are at the surface level and having mastery goals with no strategic sense of when to maximise them can be counter-productive. 62 Having goals, per se , is worthwhile—and this relates back to the general principle of having notions of what success looks like before investing in the learning. The first step is to teach students to have goals relating to their upcoming work, preferably the appropriate mix of achieving and deep goals, ensure the goals are appropriately challenging and then encourage students to have specific intentions to achieve these goals. Teaching students that success can then be attributed to their effort and investment can help cement this power of goal setting, alongside deliberate teaching.

The environment

Despite the inordinate attention, particularly by parents, on structuring the environment as a precondition for effective study, such effects are generally relatively small ( Table 5 ). It seems to make no differences if there is background music, a sense of control over learning, the time of day to study, the degree of social support or the use of exercise. Given that most students receive sufficient sleep and exercise, it is perhaps not surprising that these are low effects; of course, extreme sleep or food deprivation may have marked effects.

Knowing the success criteria

A prediction from the model of learning is that when students learn how to gain an overall picture of what is to be learnt, have an understanding of the success criteria for the lessons to come and are somewhat clear at the outset about what it means to master the lessons, then their subsequent learning is maximised. The overall effect across the 31 meta-analyses is 0.54, with the greatest effects relating to providing students with success criteria, planning and prediction, having intentions to implement goals, setting standards for self-judgements and the difficulty of goals ( Table 6 ). All these learning strategies allow students to see the ‘whole’ or the gestalt of what is targeted to learn before starting the series of lessons. It thus provides a ‘coat hanger’ on which surface-level knowledge can be organised. When a teacher provides students with a concept map, for example, the effect on student learning is very low; but in contrast, when teachers work together with students to develop a concept map, the effect is much higher. It is the working with students to develop the main ideas, and to show the relations between these ideas to allow students to see higher-order notions, that influences learning. Thus, when students begin learning of the ideas, they can begin to know how these ideas relate to each other, how the ideas are meant to form higher order notions, and how they can begin to have some control or self-regulation on the relation between the ideas.

Synthesis of the learning phases of the model

There are many strategies, such as organising, summarising, underlining, note taking and mnemonics that can help students master the surface knowledge ( Table 7 ). These strategies can be deliberately taught, and indeed may be the only set of strategies that can be taught irrespective of the content. However, it may be that for some of these strategies, the impact is likely to be higher if they are taught within each content domain, as some of the skills (such as highlighting, note taking and summarising) may require specific ideas germane to the content being studied.

While it appears that training working memory can have reasonable effects ( d =0.53) there is less evidence that training working memory transfers into substantial gains in academic attainment. 63 There are many emerging and popular computer games that aim to increase working memory. For example, CogMed is a computer set of adaptive routines that is intended to be used 30–40 min a day for 25 days. A recent meta-analysis (by the commercial owners 64 ) found average effect-sizes (across 43 studies) exceed 0.70, but in a separate meta-analysis of 21 studies on the longer term effects of CogMed, there was zero evidence of transfer to subjects such as mathematics or reading 65 . Although there were large effects in the short term, they found that these gains were not maintained at follow up (about 9 months later) and no evidence to support the claim that working memory training produces generalised gains to the other skills that have been investigated (verbal ability, word decoding or arithmetic) even when assessment takes place immediately after training. For the most robust studies, the effect of transfer is zero. It may be better to reduce working memory demands in the classroom. 66

The investment of effort and deliberate practice is critical at this consolidation phase, as are the abilities to listen, seek and interpret the feedback that is provided ( Table 8 ). At this consolidation phase, the task is to review and practice (or overlearn) the material. Such investment is more valuable if it is spaced over time rather than massed. Rehearsal and memorisation is valuable—but note that memorisation is not so worthwhile at the acquisition phase. The difficult task is to make this investment in learning worthwhile, to make adjustments to the rehearsal as it progresses in light of high levels of feedback, and not engage in drill and practice. These strategies relating to consolidating learning are heavily dependent on the student’s proficiency to invest time on task wisely, 67 to practice and learn from this practice and to overlearn such that the learning is more readily available in working memory for the deeper understanding.

Acquiring deeper learning