- Translators

- Graphic Designers

- Editing Services

- Academic Editing Services

- Admissions Editing Services

- Admissions Essay Editing Services

- AI Content Editing Services

- APA Style Editing Services

- Application Essay Editing Services

- Book Editing Services

- Business Editing Services

- Capstone Paper Editing Services

- Children's Book Editing Services

- College Application Editing Services

- College Essay Editing Services

- Copy Editing Services

- Developmental Editing Services

- Dissertation Editing Services

- eBook Editing Services

- English Editing Services

- Horror Story Editing Services

- Legal Editing Services

- Line Editing Services

- Manuscript Editing Services

- MLA Style Editing Services

- Novel Editing Services

- Paper Editing Services

- Personal Statement Editing Services

- Research Paper Editing Services

- Résumé Editing Services

- Scientific Editing Services

- Short Story Editing Services

- Statement of Purpose Editing Services

- Substantive Editing Services

- Thesis Editing Services

Proofreading

- Proofreading Services

- Admissions Essay Proofreading Services

- Children's Book Proofreading Services

- Legal Proofreading Services

- Novel Proofreading Services

- Personal Statement Proofreading Services

- Research Proposal Proofreading Services

- Statement of Purpose Proofreading Services

Translation

- Translation Services

Graphic Design

- Graphic Design Services

- Dungeons & Dragons Design Services

- Sticker Design Services

- Writing Services

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

6 Steps to Mastering the Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation

As the pivotal section of your dissertation, the theoretical framework will be the lens through which your readers should evaluate your research. It's also a necessary part of your writing and research processes from which every written section will be built.

In their journal article titled Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your "house" , authors Cynthia Grant and Azadeh Osanloo write:

The theoretical framework is one of the most important aspects in the research process, yet is often misunderstood by doctoral candidates as they prepare their dissertation research study. The importance of theory-driven thinking and acting is emphasized in relation to the selection of a topic, the development of research questions, the conceptualization of the literature review, the design approach, and the analysis plan for the dissertation study. Using a metaphor of the "blueprint" of a house, this article explains the application of a theoretical framework in a dissertation. Administrative Issues Journal

They continue in their paper to discuss how architects and contractors understand that prior to building a house, there must be a blueprint created. This blueprint will then serve as a guide for everyone involved in the construction of the home, including those building the foundation, installing the plumbing and electrical systems, etc. They then state, We believe the blueprint is an appropriate analogy of the theoretical framework of the dissertation.

As with drawing and creating any blueprint, it is often the most difficult part of the building process. Many potential conflicts must be considered and mitigated, and much thought must be put into how the foundation will support the rest of the home. Without proper consideration on the front end, the entire structure could be at risk.

With this in mind, I'm going to discuss six steps to mastering the theoretical framework section—the "blueprint" for your dissertation. If you follow these steps and complete the checklist included, your blueprint is guaranteed to be a solid one.

Complete your review of literature first

In order to identify the scope of your theoretical framework, you'll need to address research that has already been completed by others, as well as gaps in the research. Understanding this, it's clear why you'll need to complete your review of literature before you can adequately write a theoretical framework for your dissertation or thesis.

Simply put, before conducting any extensive research on a topic or hypothesis, you need to understand where the gaps are and how they can be filled. As will be mentioned in a later step, it's important to note within your theoretical framework if you have closed any gaps in the literature through your research. It's also important to know the research that has laid a foundation for the current knowledge, including any theories, assumptions, or studies that have been done that you can draw on for your own. Without performing this necessary step, you're likely to produce research that is redundant, and therefore not likely to be published.

Understand the purpose of a theoretical framework

When you present a research problem, an important step in doing so is to provide context and background to that specific problem. This allows your reader to understand both the scope and the purpose of your research, while giving you a direction in your writing. Just as a blueprint for a home needs to provide needed context to all of the builders and professionals involved in the building process, so does the theoretical framework of your dissertation.

So, in building your theoretical framework, there are several details that need to be considered and explained, including:

- The definition of any concepts or theories you're building on or exploring (this is especially important if it is a theory that is taken from another discipline or is relatively new).

- The context in which this concept has been explored in the past.

- The important literature that has already been published on the concept or theory, including citations.

- The context in which you plan to explore the concept or theory. You can briefly mention your intended methods used, along with methods that have been used in the past—but keep in mind that there will be a separate section of your dissertation to present these in detail.

- Any gaps that you hope to fill in the research

- Any limitations encountered by past researchers and any that you encountered in your own exploration of the topic.

- Basically, your theoretical framework helps to give your reader a general understanding of the research problem, how it has already been explored, and where your research falls in the scope of it. In such, be sure to keep it written in present tense, since it is research that is presently being done. When you refer to past research by others, you can do so in past tense, but anything related to your own research should be written in the present.

Use your theoretical framework to justify your research

In your literature review, you'll focus on finding research that has been conducted that is pertinent to your own study. This could be literature that establishes theories connected with your research, or provides pertinent analytic models. You will then mention these theories or models in your own theoretical framework and justify why they are the basis of—or relevant to—your research.

Basically, think of your theoretical framework as a quick, powerful way to justify to your reader why this research is important. If you are expanding upon past research by other scholars, your theoretical framework should mention the foundation they've laid and why it is important to build on that, or how it needs to be applied to a more modern concept. If there are gaps in the research on certain topics or theories, and your research fills these gaps, mention that in your theoretical framework, as well. It is your opportunity to justify the work you've done in a scientific context—both to your dissertation committee and to any publications interested in publishing your work.

Keep it within three to five pages

While there are usually no hard and fast rules related to the length of your theoretical framework, it is most common to keep it within three to five pages. This length should be enough to provide all of the relevant information to your reader without going into depth about the theories or assumptions mentioned. If you find yourself needing many more pages to write your theoretical framework, it is likely that you've failed to provide a succinct explanation for a theory, concept, or past study. Remember—you'll have ample opportunity throughout the course of writing your dissertation to expand and expound on these concepts, past studies, methods, and hypotheses. Your theoretical framework is not the place for these details.

If you've written an abstract, consider your theoretical framework to be somewhat of an extended abstract. It should offer a glimpse of the entirety of your research without going into a detailed explanation of the methods or background of it. In many cases, chiseling the theoretical framework down to the three to five-page length is a process of determining whether detail is needed in establishing understanding for your reader.

Use models and other graphics

Since your theoretical framework should clarify complicated theories or assumptions related to your research, it's often a good idea to include models and other helpful graphics to achieve this aim. If space is an issue, most formats allow you to include these illustrations or models in the appendix of your paper and refer to them within the main text.

Use a checklist after completing your first draft

You should consider the following questions as you draft your theoretical framework and check them off as a checklist after completing your first draft:

- Have the main theories and models related to your research been presented and briefly explained? In other words, does it offer an explicit statement of assumptions and/or theories that allows the reader to make a critical evaluation of them?

- Have you correctly cited the main scientific articles on the subject?

- Does it tell the reader about current knowledge related to the assumptions/theories and any gaps in that knowledge?

- Does it offer information related to notable connections between concepts?

- Does it include a relevant theory that forms the basis of your hypotheses and methods?

- Does it answer the question of "why" your research is valid and important? In other words, does it provide scientific justification for your research?

- If your research fills a gap in the literature, does your theoretical framework state this explicitly?

- Does it include the constructs and variables (both independent and dependent) that are relevant to your study?

- Does it state assumptions and propositions that are relevant to your research (along with the guiding theories related to these)?

- Does it "frame" your entire research, giving it direction and a backbone to support your hypotheses?

- Are your research questions answered?

- Is it logical?

- Is it free of grammar, punctuation, spelling, and syntax errors?

A final note

In conclusion, I would like to leave you with a quote from Grant and Osanloo:

The importance of utilizing a theoretical framework in a dissertation study cannot be stressed enough. The theoretical framework is the foundation from which all knowledge is constructed (metaphorically and literally) for a research study. It serves as the structure and support for the rationale for the study, the problem statement, the purpose, the significance, and the research questions. The theoretical framework provides a grounding base, or an anchor, for the literature review, and most importantly, the methods and analysis. Administrative Issues Journal

Related Posts

How To Write a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

Understanding Dependent Variables

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Published on October 14, 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Tegan George.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your paper or dissertation topic is relevant and grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualizes your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis , or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalizations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyze The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviorist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

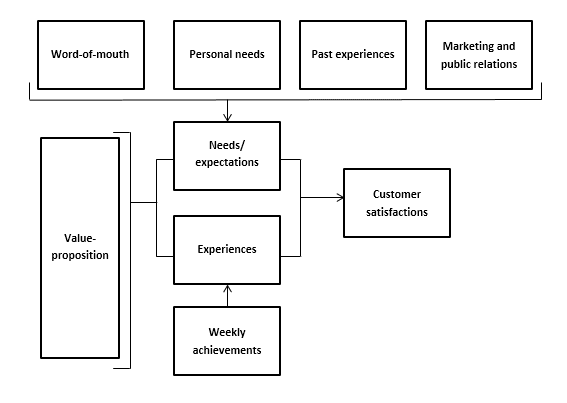

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarizing and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organize by theory cluster

- Organize by date

It’s important that the information in your theoretical framework is clear for your reader. Make sure to ask a friend to read this section for you, or use a professional proofreading service .

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis , or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing. Scribbr. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Coaching Services

- All Articles

- Is Dissertation Coaching for Me?

- Dissertation First Steps

- Research Strategies

- Writing Workshop

- Books & Courses & Other Resources

- Professional Development

- In The Media

What is Theory and How to Use it in Your Dissertation

A key question for many dissertation students just getting started on their proposals is, “what is theory in dissertations, anyway?”

A post on the topic of “what is theory” could expand to fill a whole book – and indeed, many books have been written on this topic. this post is your quick intro guide to theory for dissertation students..

What is theory?

Theory at the most basic level is an attempt to explain something..

When you conduct research, you will come across two types of source: theory and applied research. If you see a source that describes finding participants, gathering data, analyzing data, and so on, you are most likely looking at applied research. This type of research gathers data in an attempt to develop or test a theory.

On the other hand, if you see a source that attempts to provide an overarching explanation, you are looking at theory. There are a lot of theories out there. For example, feminist theory attempts to provide an overarching explanation for the unequal treatment of women in society. Addiction theory attempts to explain how and why people become addicted. And so on.

Theories are not set in stone. Researchers – including dissertation students – seek to test, disprove, or build theories. It’s worth remembering that you can never prove a theory correct with research, although you can add to its strength and validity.

What is a theoretical framework?

A theoretical framework is the particular theory you choose to give direction and focus to your dissertation research study..

Your chosen theory will determine how you present the context and problem statement, how you choose your research questions, what you include in your literature review, and how you interpret your data.

Theory and the Context, Research Questions, and Problem Statement

Theory will help you determine how you present the context of your study..

It provides a lens through which you filter the topic, allowing you to present the background information in a way that relates logically to your research questions. It also enables you to choose specific research questions that relate to a theory-specific problem.

For example, (some) feminist research focuses specifically on social problems as they relate to women. A researcher approaching the problem of underaged drinking via feminist theory might therefore choose to ask questions about the impact of underaged drinking on violence toward women, the impact of underaged drinking women’s professional trajectories, and so on. The researcher will most likely aim to address a problem relating to the social impact on women of underaged drinking.

The same researcher will probably choose to present background information relating to gender differences in underaged drinking convictions, drop-out rates for underaged female college students, and so on.

Theory and the Lit Review

Your literature review will need to begin by presenting your theoretical framework in detail..

Your reader needs to know what theory you have chosen to work with, why you have chosen it, how it addresses your chosen problem and questions, and whether you are seeking to test it, disprove it, or add to/replace it.

You should aim to summarize key ideas and historical developments in the theory, as well as presenting the main theorists and the work currently being done with the theory in your field.

Theory and the Study Design/Methodology

Theorists have also explored the question of how and why research happens, which means you will need to touch on theory in your methodology..

First, aim to explain the theory that underpins your chosen method. Why is that method perfect for the questions you are trying to answer, at a theoretical level? A good book on research design or theory of research will help enormously when it comes to answering this question.

Second, aim to show how your chosen theoretical framework can be applied to your study design. For example, a researcher using feminist theory might want to describe the appropriateness of qualitative methods for substantiating women’s voices and lived experiences.

Theory and Data Analysis

Finally, you will want to use your theoretical framework as a starting point for interpreting your data to answer your research questions..

You can start by asking yourself some basic questions, such as:

- Does my data support or refute some part of the theory?

- Does my data suggest a modification is needed to the existing theory?

- Is a new theory needed to explain my data?

- Can the theory help explain the significance of my data?

Assuming you chose a theoretical framework well aligned to your research questions, these sorts of approaches to the data will help you answer the research questions systematically and logically.

How to Get Good at Theory

Read. thank you and goodnight..

But seriously, the only way to get good at using theory is to get comfortable with it – read everything you can until you understand your theory inside and out. Read other studies in your field to see how others are engaging with the theory. Apply the theory to everything in your everyday life until your friends and family stop speaking to you.

Theory is complex and difficult – mastering it is part of what makes you a researcher.

Need more help?

Need some help developing your theoretical framework? Book a free session to find out how dissertation coaching can help.

Related Articles

- Current Issue

- Journal Archive

- Current Call

Search form

Building a Dissertation Conceptual and Theoretical Framework: A Recent Doctoral Graduate Narrates Behind the Curtain Development

Dr. Jordan Tegtmeyer

This article examines the development of conceptual and theoretical frameworks through the lens of one doctoral student’s qualitative dissertation. Using Ravitch and Carl’s (2021) conceptual framework guide, each key component is explored, using my own dissertation as an example. Breaking down each framework section step-by-step, my journey illustrates the iterative process that conceptual framework development requires. While not every conceptual framework is developed in the same way, this iterative approach allows for the production of a robust and sound conceptual framework.

Introduction

While progressing on my doctoral journey I struggled to learn, and then navigate, what it meant to do quality academic research. While I had worked in higher education for over 15 years when I entered into my doctoral program in Higher Education at Penn, and had earned multiple master’s degrees, I felt wholly unprepared to complete a dissertation. It felt, at first, beyond my reach. Now that I have completed the dissertation, my hope is to pay it forward by sharing reflections on the process as a guide to help other researchers navigate the development of a robust conceptual and theoretical framework for their own dissertations.

My journey into this doctoral inquiry began before I even realized it. I entered the program with a strong idea of what I wanted to study but no “academic” frameworks to help me chart the journey. Little did I know that that is in fact what conceptual frameworks do, they help guide you from early ideation to a finalized study. The turning point in my own learning, let’s call it an epiphany of sorts, happened in a qualitative research methods course that introduced Ravitch and Carl’s Qualitative Research: Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological. I was introduced to the basic concepts needed to turn my own research ideas into actionable research questions. While this was not the only source to guide me on this journey, conversations with peers and professionals, other courses and independent studies also moved me along, it was reading this text that gave me the academic terminology and frameworks I needed to build a robust and rigorous dissertation research design.

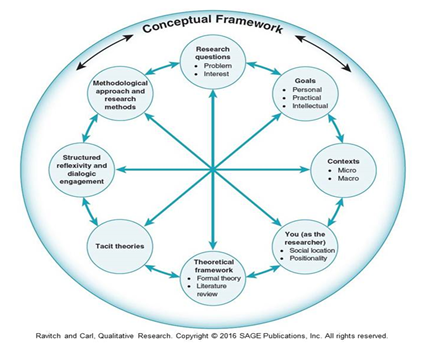

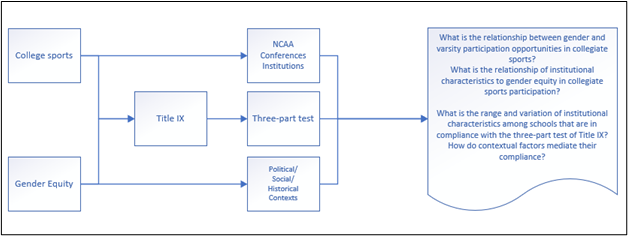

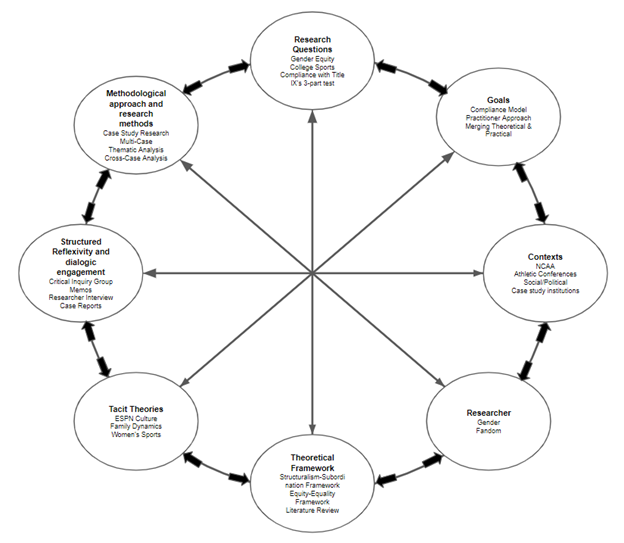

To guide the development of strong conceptual and theoretical frameworks I use Ravitch and Carl’s (2021) components of a conceptual framework graphic (p. 38) below:

Using this visual of the framework as a guide, I share how I developed and used theoretical frameworks in a case study dissertation and how the development of my conceptual framework played out in my study.

Building a Dissertation Study

For context, I describe my dissertation study to bridge the theoretical with the reality of my dissertation. Seeing these ideas and terms applied in a real-world context should provide some guidance on how to address them in the construction of your own conceptual framework.

My dissertation study examined gender equity in college sports, specifically examining institutional characteristics and their potential impact on Title IX compliance. Using case study research, I examined two institutions and then contrasted them to see if there were particular characteristics about those institutions that made them more likely to comply with Title IX’s three-part test. Overall, the study found that there are some institutional characteristics that impact Title IX compliance.

The evolution of a research idea into a study design is useful for understanding the impact that developing a conceptual framework has on this work. Adding the academic structure required to go from idea to fully realized conceptual framework is integral to a sound study. Going into the doctoral program I had a couple of broad ideas I wanted to bring together in a formal study. I knew I wanted to study college sports for a number of reasons including that I am a huge sports fan working in higher education who wanted to better understand the college sports context. I also wanted to integrate issues of gender disparities into my work to better understand disparities around athletic participation between the sexes as outlined by Title IX legislation. For me, the goal was to bring these broad topics and interests together. Turning these topics into a problem my study could address was critical. Once I made this shift to problem statement, it became about transitioning from problem to research questions from which I could use to drive the potential study.

Understanding this evolution, from a research idea into a study design, is important as it speaks to the understanding the two are not the same. A researcher has to work through an iterative process in order to take a research idea, and through developing their study’s conceptual framework, turn it into a study. Starting with research interests you are passionate about is important, but it is only the first step in a journey to a high-quality research study. For me this meant understanding what made my ideas important and how they could be studied. Why was gender equity in college sports important and what was causing the inequities in athletic participation between the genders? Say a bit more on this–how did you do this?

Developing Guiding Research Questions

I began with the Ravitch and Carl (2021) conceptual framework diagram as a guide, starting with the research questions positioned at the top. It's important to note that the development of research questions is an active and iterative process that evolves and changes over time. Looking back at notes I took throughout my dissertation journey, I found at least a dozen different iterations of my own research questions. Looking back at the evolution of my own research question, allowed me to see just how iterative of a process this really is. Second, developing research questions is largely about whittling down your broad ideas and interests into something that is scoped in such a way as to be doable.

For me, I started with these broad areas of interest and whittled them down from there, focusing and iterating. Next, I sought to understand the goals of my study and who the intended audiences were (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). I knew I wanted to develop something that was useful for practitioners. Being a higher education practitioner myself, I wanted something people in the field could use and learn from. Knowing this was extremely important to developing the study’s research questions since it helped me to map them onto the goals and audiences I imagined for the study.

The research questions should address the problem you are trying to solve and why it's important (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). For me, the goal was to explore what was causing gender athletic participation inequities and how that fit into broader gender disparities in higher education and the country .

My final research questions show how far they had come from my topics of interest.

- What is the relationship between gender and varsity participation opportunities in collegiate sports?

- What is the relationship of institutional characteristics to gender equity in collegiate sports participation?

Additional questions related to institutional characteristics are:

- What is the range and variation of institutional characteristics among schools that are in compliance with the three-part test of Title IX?

- How do contextual factors mediate their compliance?

At first these questions focused on understanding gender disparities in regards to athletic participation opportunities in college sports. I sought to understand the extent of the disparities and which institutions had them. From there I wanted to understand potential institutional characteristics that could serve as predictors of Title IX compliance. For this, I wanted to explore the impact general institutional characteristics like, undergraduate gender breakdown, might have on creating potential difficulties with navigating Title IX compliance. It was important to investigate the similarities and differences between the two cases in my study. This would help inform whether there were unique things about each institution that were having an effect on Title IX compliance at that institution. This was about understanding what is happening at each of the cases and the reason I chose the methodological approach I did.

Developing Study Goals

A study’s goals are the central part of the conceptual framework as they help turn an interest or concern into a research study. Goal mapping for a study is this process that maps out, or theoretically frames the key goals of the study (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). The study’s goals come from many different sources including personal and professional goals, prior research, existing theory, and a researcher’s own thoughts, interests, and values (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). In my dissertation study, it was a combination of all of those things, although I didn’t realize it at first. The truth is, I didn’t realize I was building conceptual and theoretical frameworks at the time, but in fact I was incrementally building up to them. I talked with experts, advisors, my professors, mentors, academic peers and practitioners to slowly build my own contextual understanding of the research questions, theory, and methodology along the way.

The study goals for my dissertation emerged from multiple vantage points. I thought it was senseless that after 50 years of Title IX, schools were still ignoring the law (willfully or not). Some of the best athletes I’ve known have been women, including my sister. This gave me an appreciation for women’s sports at an early age. From a practitioner-scholar’s standpoint, I didn’t see anything that was usable in “real life.” At least nothing that didn’t require a law degree or extensive knowledge of the law, something most people do not have. I had also come across Charles Kennedy’s 2007 Gender Equity Scorecard in a prior class that gave me the idea for the compliance model. This study was designed to measure schools’ compliance with various aspects of Title IX, but only examined the proportionality requirement of the three-part test (Kennedy, 2007). This was a good start because it provided a template from which to assess compliance when examining gender equity in college sports but helped me to see the need for an easy-to-understand model that covered all aspects of the three-part test that practitioners could use on their own campuses. As a way to better understand Title IX compliance among institutions I then built the compliance model that addressed the entire three-part test with a lawyer friend and used it to do an almost test run of the sampling.

Lastly, as I refined my topic, there seemed to be something missing from the literature. This missing piece gave me the idea for merging the theoretical and the practical dimensions of Title IX compliance within the context of college athletics. A compliance model, using a legal and statutory approach but also grounded in theory, that could be used by practitioners in real life. This model could then help researchers understand why Title IX non-compliance was still an issue today. For me and my study, applying this model to publicly available data, helped to understand why women athletes are not getting their fair share of athletic participation opportunities guaranteed by a law passed over 50 years ago. This process of having to seek out data, taught me the continued need for a proactive approach to measuring compliance with all the participation aspects of Title IX.

Understanding Contexts of the Work

Understanding the contexts of your intended study is critical as it helps set the stage for your study’s position in the real world. Knowing the actual setting of your study and its context are important as it speaks to the micro contexts. The who and what aspects of that setting are central to your research. It is this context within the context that helps us understand the aspects that influence what we study and how we frame the study (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). At the micro level, my study sought to focus on the institutional structures and workings of two universities. I chose case study research because it allowed me to focus on those two institutions, and that was very intentional, as I wanted to understand their specific institutional structures and their potential impacts on Title IX compliance.

Understanding the macro level contexts impacting my study was also important. It is the combination of social, historical, national, international, and global level contexts that create the conditions in which your study is conducted. As Ravitch and Carl (2021) state it is these broad contexts “that shape society and social interactions, influence the research topic, and affect the structure and conditions of the settings and the lives of the people at the center of your research and you” (p. 52). This has two important implications for conceptual framework development. First, it is important to investigate and thoroughly understand the setting of the study that reflects the conditions as lived by the stakeholders (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). As you design your study it is important to consider what’s happening in that moment and how your study is situated in a specific moment in time which impacts both the context and setting of your study but also how you come to view and approach it (Ravitch & Carl, 2021).

For my dissertation, understanding college sports and higher education in the broadest sense was important when thinking about the macro contexts influencing my study. Things like: how does the NCAA and conferences play a role in this area? How does higher education handle gender equity in college sports as it relates to the missions of the institutions? And even more broadly, how does this study fit into broader societal structures regarding equality? Given everything that was going on in college sports at the time (issues at the NCAA’s women’s basketball tournament, volleyball, softball), the contexts illustrated the broader need for understanding this issue in that moment of time. This illuminates the importance of taking the time to understand the different contexts impacting your study and why they are important.

Researcher Reflexivity

When thinking about social identity and positionality, it is vital to understand that the researcher is viewed as a vital part of the study itself, the primary instrument and filter of interpretation (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). Positionality refers to the researcher’s role and social identity in relationship to the context and setting of the research. I think of this as what we as researchers bring to the table—who we are and what we know and how that impacts what we do and how we do it. Understanding how these aspects of oneself all interact and make me who I am, while also understanding my potential impact on my research is critical to a strong conceptual framework.

For my study, I worried about my positionality in particular: my gender and my fandom. I was worried my various identities would influence my approach negatively in ways I would be unaware of. I, someone who identifies as male, wanted to be taken seriously while addressing a gender equity issue from a privileged gender position. I also didn’t want to overlook or discount anything because of who I am and how I viewed the world of college sports. This illuminates the importance of understanding one’s identities and their potential impact on the study. There were numerous ways I addressed this through the study including engaging my critical inquiry group, drafting memos, and using a researcher interview to elicit self-reflection.

Theoretical Framework Development

When working through the development of a theoretical framework within a conceptual framework, one must account for the integration of formal theory and the use of the literature review. Formal theory is those established theories that come together to create the frame for your research questions. The researcher must seek out formal theories to help understand what they are studying and why they are studying it (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). Ravitch & Carl said this best, “the theoretical framework is how you weave together or integrate existing bodies of literature…to frame the topic, goals, design, and findings of your specific study” (p. 58).

It is important to point out that the process of creating a theoretical framework is separate from a literature review. The theoretical framework does impact the literature review and the literature review impacts it, but they are separate. You may discover theories that strengthen your theoretical framework as you review literature, and you may seek out theories to validate a hypothesis you have related to your study. This is important because your formal theories do not encompass all the theories related to your topic, but the specific theories that bind your study together and give it structure.

For my study, formal theories ended up being an equity-equality framework developed by Espinoza (2007) and a structuralism-subordination framework derived from Chamallas (1994). The equity-equality framework was used to address what I had seen as confusion between the two terms, using them interchangeably, when reviewing literature examining Title IX. I wanted to understand if the confusion about the terms, equity and equality, led to a misunderstanding about the true intent of Title IX and intercollegiate athletics. For the structuralism-subordination framework, I wanted to understand if there were institutional structures that institutions had built that led to the subordination of women. I also wanted to understand if those structures manifest themselves in ways that hinder institutions’ Title IX compliance, leaving women without the participation opportunities required by law.

Both of these formal theories had an impact on and were impacted by my literature review. The structuralism-subordination framework was discovered after my initial review of Title IX literature, while the equity-equality framework was needed to reflect inconsistencies in the use of those terms in texts reviewed for the literature review. These formal theories also helped me refine my research questions and the purpose of my study. The formal theories impact on the different aspects of my conceptual framework then required me to refine and redefine by literature in order to incorporate their impact. This understanding of formal theory as the framework to construct a study is central to constructing a robust theoretical framework.

What helped me arrive at these theories in the great morass of theories was Title IX’s application to college sports, feminist scholar’s work related to college sports, and the use and misuse of the equity and equality in the literature.

Naming Tacit Theories

It is not just your role as the researcher that impacts your study, it is also all the informal ways in which we understand the world. We all have working hypotheses, assumptions, or conceptualizations about why things occur and how they operate (Ravitch & Carl, 2021). This is a result of how we were raised and socialized which has a direct impact on the ways that we see our work and the contexts in which it takes place. For me as the researcher for this study, three tacit theories emerged upon examination through memos and dialogic engagement with peers and advisors, described in the next section. One, was related to what I call, college sports fandom or the ESPN culture. For me, I grew up on ESPN as did many of my friends. We got most of our sports news through these mediums and it greatly impacted how we viewed and thought of college sports. The problem with this is that ESPN has helped propagate many false narratives and misconceptions about college sports. A few examples include: big time college sports and programs make money (most do not), men’s sports are more popular than women’s (men get the majority of airtime), and college sports make a lot of money (where it gets its “money” is not where you think). There was also the continual sexualization and diminishment of women athletes.

Family dynamics also played a major role in my sports fandom and its importance. Sports were big in my family as most members played but we also watched a lot together. It was a bonding mechanism for us. For our family, my sister was our best athlete. This meant attending a lot of her games which led to an appreciation of women’s sports at an early age. Lastly, I had a general lack of knowledge around gender equity in college sports, mostly related to my fandom described above. I didn’t develop a true understanding until graduate school when I went out of my way to do deep dives into the topic whenever I could. This process of self-discovery and reflection with my own tacit theories teaches the importance of examining oneself, our socialization and its impact on your research. The dissertation reflection process was cathartic, it brought together these various strands of my identity, history, and interests and helped me to identify and then reckon with my unconscious biases, assumptions, and drivers.

Structured Reflexivity and Dialogic Engagement

I relied on structured reflexivity and dialogic engagement as my main reflexivity strategy, reflecting on my research through purposeful engagement with others a lot throughout my study. I went back and forth many times between different aspects of my conceptual framework as “new” information was discovered. Sometimes this reflexivity was planned, for example, after completing one part of my conceptual framework I would review other aspects to consider the impact. This would help me to ensure the potential impact of this new information was assessed against all parts of the conceptual framework. Other times it was completely spontaneous such as an illuminating reading or discovery would spark me to think about a piece of conceptual framework differently and adjust. In one particular moment, I came across some conflicting information during one of the cases that required me to rethink aspects of my entire conceptual framework. This conflicting information indicated another approach to measuring Title IX compliance which was at conflict with mine. I met with various members of my critical inquiry group to decide on a path forward and then wrote a memo outlining what happened and the decision made. This incident caused me to not only conduct dialogic engagement but also structured reflexivity as I reviewed all aspects of my conceptual framework to ensure everything still made sense as it was structured given the new information.

The key structured reflexivity mechanisms I used in my study were memos, a critical inquiry group, a researcher interview and case reports. Each of these proved to be an invaluable resource when navigating the construction of my conceptual framework. I used different kinds of memos to highlight key decisions which were useful later when writing my dissertation.

My critical inquiry group, composed of college sports experts, peers, women’s rights advocates, Title IX consultants and lawyers, had multiple functions throughout my study. They challenged me on assumptions and decision making, helped me work through challenges and served as sounding boards to bounce ideas off of. My researcher interview, which is when the researcher is interviewed to pull out tacit knowledge and assumptions, was particularly useful as it allowed for a non-biased critique to focus on process, procedure, and theory (both the theoretical and conceptual). My interviewer also called out my tacit theories and biases which were helpful in structuring that section of my conceptual framework. Lastly, I used case reports as a way to summarize my cases individually in their own distinct process guaranteeing each received a deep dive. This also allowed me to make refinements after the first case and also helped lay the groundwork for a cross-case analysis. The entire process taught me that having these structured mechanisms adds validation points and reflection opportunities from which I could refine my work.

Methodological Approach and Research Methods

For any researcher the methodological approach is guided by the study’s research questions. This section is also partly shaped and derived from the conceptual framework. For some, they will arrive at the methodological approach that best fits their study along the way, picking it up from other pieces of their conceptual framework. For others, the approach is clear from the beginning and drives some of their conceptual framework decision making. For me, I arrived at my methodological approach as it became clear as my conceptual framework developed. As I worked through the interactions of my research questions, informed by my developing conceptual framework, it became clear that case study research was the right methodological approach for my study.

The methodological approach I chose for my dissertation was case study research, which made sense given that the primary goal was to gain a clear understanding of the “how” and “why” of each case, which is especially important when examining the two cases in this study (Yin, 2018). Understanding the complexities and contextual circumstances of Title IX cases is especially crucial given its real-world impact on universities (Yin, 2018). The in-depth focus of case study research allowed for a much richer understanding of the potential impacts of institutional and athletics department characteristics impacting Title IX compliance today (Yin, 2018).

I used a multi-case approach because I wanted to compare and contrast one school that was “good” at Title IX compliance and one that was not. Each case was completed separately for a deep dive and better understanding using thematic analysis for the data analysis. After each case report was completed, themes were reviewed. After both cases were completed a cross-case analysis was done to compare and contrast the cases using the themes derived from each case. For the data collection process, I used the following: archival records and documents including meeting minutes and institutional reports, memos for data collection and data analysis, dialogic engagement, and a researcher interview. My learning throughout the dissertation process illuminates the importance and generative value of using a methodological approach that aligns with the goals of the study and is guided by the research questions.

Key Takeaways

If you remember anything from this, please remember these three things:

- Developing a conceptual framework is an iterative process. It will feel like you are constantly making changes. That’s ok. That’s what good research is, constantly evolving and getting better. My research questions looked nothing like what they started as. They evolved and were informed by newer and better research over time. That is what this process is meant to do, make your research better as you move along.

- When you get a new piece of information, use it to inform the next part of your process and refine the last. You should use each new finding or insight to refine your work and inform the next piece.

- Engage your classmates and professors for guidance. You have access to incredible resources in these two populations, use them to help you along the way. And of course, be a resource to them as well. I can’t remember how many times I sought out a classmate who shared something insightful in class to find out more information. You are surrounded by smart, motivated people, who want you to succeed, actively use that support system.

Parting Wisdom

My last bits of wisdom as you are embarking on this journey are meant to serve as things that I wish I had known at the beginning that I wanted to be sure others knew too.

- First and foremost, love your topic. I cannot stress this enough. You are going to be spending a lot of time and investing a lot of energy in it, you should love it. That’s not to say you won’t be frustrated, tired and “over it” at times, but at the end of the day you should love it.

- Second, use your classmates as a resource and be a resource to them. Although they aren’t likely to know your topic as in-depth as you do, they can offer valuable insights, largely because they are not you. You can “stress test” your ideas, research questions, frameworks or just have a fresh set of eyes on your work. You should be the same for them as it only makes your own work stronger as well. Reciprocity is key.

- Third, don’t be afraid to ask questions. The old adage is true, there are no dumb questions. Ask all of your questions, in whatever manner you are comfortable doing so, just be sure to ask them. You’ll find that once you give them air, they do get answered and the path gets that much more clear.

- Fourth, don’t be afraid to admit possible mistakes or confusions and ask for help mid-concern. No one is perfect and mistakes happen. Acknowledging those mistakes sooner rather than later can only make your work stronger. I had a setback towards the end of my dissertation that at first froze me and I didn’t know what to do. It was only after I acknowledged the mistake and talked with my advisor and critical inquiry group that I could come up with a path forward. My work was better and stronger because of the help I received, even though in the moment I felt vulnerable fessing up.

- Fifth, memos are your best friends. I cannot stress this enough. I wish I could go back and tell myself this at the very beginning of my journey to chart more at that stage. Documenting decision making, mistakes, rationales, conversations and anything else of even possible importance to your methods is invaluable when you get to the writing stage. Being able to refer to those documents and reflect on them makes your methods more specific and your dissertation stronger.

- Sixth, know when to stop. This is especially true during your literature review. There is so much material out there, you will never read it all. Take that in. Knowing when you should stop and move on is extremely important. For me, I read about 2 months too long and it set me behind. I still had huge stacks of reading that I could have done but pulling more and more sources from more and more readings was a never-ending path. Get what you need, cover your ground, trust yourself to call it when it's covered. Ask people if you can stop if you aren’t sure.

Finally, and this may feel challenging, let yourself enjoy the ride! Parts will be smooth, others bumpy. By the end you will be tired, burnt out and just want to be done. But stop along the way and enjoy the moments of learning and connection. Those middle of the night texting sessions with your classmates about some obstacle or interesting article you found do matter. Those coffees with professors discussing your topic (and your passion for it) stay with you. Those classes with other really smart and engaged classmates continue to teach you. I can tell you that, looking back almost a year after defending, I miss it all. You will never have this moment in your life again, try to enjoy it.

Chamallas, M. (1994). Structuralist and cultural domination theories meet Title VII: Some contemporary influences. Michigan Law Review , 92(8), 2370–2409.

Espinoza, O. (2007). Solving the equity-equality conceptual dilemma: A new model for analysis of the educational process. Educational Research , 49(4), 343–363.

Kennedy, C. L. (2007). The Gender Equity Scorecard V. York, PA. Retrieved from http://ininet.org/the-gender-equity-scorecard-v.html .

Ravitch S. M. & Carl, M. N. (2021). Qualitative Research: Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological. (2nd Ed.). Sage Publications.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage.

Articles in this Volume

[tid]: building a dissertation conceptual and theoretical framework: a recent doctoral graduate narrates behind the curtain development, [tid]: family income status in early childhood and implications for remote learning, [tid]: the theater of equity, [tid]: including students with emotional and behavioral disorders: case management work protocol, [tid]: loving the questions: encouraging critical practitioner inquiry into reading instruction, [tid]: supporting the future: mentoring pre-service teachers in urban middle schools, [tid]: embracing diversity: immersing culturally responsive pedagogy in our school systems, [tid]: college promise programs: additive to student loan debt cancellation, [tid]: book review: critical race theory in education: a scholar's journey. gloria ladson-billings. teachers college press, 2021, 233 pp., [tid]: inclusion census: how do inclusion rates in american public schools measure up, [tid]: in pursuit of revolutionary rest: liberatory retooling for black women principals, [tid]: “this community is home for me”: retaining highly qualified teachers in marginalized school communities, [tid]: a conceptual proposition to if and how immigrants' volunteering influences their integration into host societies.

Report accessibility issues and request help

Copyright 2024 The University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education's Online Urban Education Journal

- Doctoral Writing Center

- Doctoral Support

- Dissertation Specific: Framework

What is a Theoretical Framework?

We know based on the word ‘theoretical’ that this framework will deal with theories (that is, principles set to explain phenomena that have already been tested and are supported by data). This type of framework will provide your readers with an idea of what you expect to find throughout your research by focusing on the principles that have already been established that will help you evaluate, connect, clarify, and identify limits within the existing knowledge surrounding your research.

Theory vs. Hypothesis

Steps to finding a theoretical framework.

Here are some ways that you can develop a solid theoretical framework:

There is a disconnect between the perception of beneficial/effective feedback by graduate students and their instructors

Possible factors affecting perception of quality feedback: practicality, usefulness, andragogy, timeliness, hierarchical cultural power dynamic, the review of the literature should cover research that has already been conducted on how students and instructors perceive quality feedback, the common factors that influence perception of quality, how adult learning influences expectations in learning (andragogy), and how the hierarchical cultural power dynamic in the united states has influenced teacher/student interactions..

Make a list of the constructs and variables.

What constructs/variables do you believe may be important to your study? These variables should be grouped into two categories: dependent and independent.

Dependent variables are the variables that you are testing in your study (how they are impacted). In this study, my dependent variable could be the perception of the effectiveness of feedback. Independent variables are variables that the researcher manipulates in order to figure out how a dependent variable is affected. In this study, my independent variables could be adult expectations and feedback techniques.

Consider what theories you have encountered in your readings and decide which theory would best explain the relationships between the most important variables in your study.

Andragogy theory

Discuss how your chosen theory will help you answer your research question. then, discuss how this theory will assist you as you conduct your research. in other words, how will your chosen theory serve as a basis for your work in this study, i would look at how andragogy theory stipulates that adult learners have different needs in the educational setting. i would look at how such needs influence students’ perceptions of feedback as useful or effective for this stage of their life., purpose of the framework.

Theory can assist you because it can guide your theoretical framework. This allows:

- New research data to be interpreted and coded for use in the future

- A possible solution to new problems for which solutions have not yet been discovered

- A way to put a name and definition to problems that are being researched

- A way to prescribe (advise) or evaluate solutions to problems that are being researched

- A way to learn about specific facts that are contained within the larger body of scholarship (and decide which are essential to a researcher’s project and which are not)

- A way of interpreting old data using new methods

- A way to identify new key issues and decide what are the key research questions that should be addressed to best understand the problem being studied

- A way of giving members of a specific discipline a universal language and a conceptual frame for defining their profession’s specific boundaries

- A way to give guidance and clarity to research so that it can assist researchers in their work and help them make improvements when practicing within their profession

Structure of a Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework is the basis of a certain theory.

If this is so, make sure your research tests whether or not that existing theory is valid in relation to a specified phenomena, event, or issue that is studied in your dissertation.

Questions to Consider

- What is the research problem or question?

- Why is the use of this framework a good solution to the problem?

Tips to Remember

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Theoretical Framework

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Theories are formulated to explain, predict, and understand phenomena and, in many cases, to challenge and extend existing knowledge within the limits of critical bounded assumptions or predictions of behavior. The theoretical framework is the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. The theoretical framework encompasses not just the theory, but the narrative explanation about how the researcher engages in using the theory and its underlying assumptions to investigate the research problem. It is the structure of your paper that summarizes concepts, ideas, and theories derived from prior research studies and which was synthesized in order to form a conceptual basis for your analysis and interpretation of meaning found within your research.

Abend, Gabriel. "The Meaning of Theory." Sociological Theory 26 (June 2008): 173–199; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (December 2018): 44-53; Swanson, Richard A. Theory Building in Applied Disciplines . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2013; Varpio, Lara, Elise Paradis, Sebastian Uijtdehaage, and Meredith Young. "The Distinctions between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework." Academic Medicine 95 (July 2020): 989-994.

Importance of Theory and a Theoretical Framework

Theories can be unfamiliar to the beginning researcher because they are rarely applied in high school social studies curriculum and, as a result, can come across as unfamiliar and imprecise when first introduced as part of a writing assignment. However, in their most simplified form, a theory is simply a set of assumptions or predictions about something you think will happen based on existing evidence and that can be tested to see if those outcomes turn out to be true. Of course, it is slightly more deliberate than that, therefore, summarized from Kivunja (2018, p. 46), here are the essential characteristics of a theory.

- It is logical and coherent

- It has clear definitions of terms or variables, and has boundary conditions [i.e., it is not an open-ended statement]

- It has a domain where it applies

- It has clearly described relationships among variables

- It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions

- It comprises of concepts, themes, principles, and constructs

- It must have been based on empirical data [i.e., it is not a guess]

- It must have made claims that are subject to testing, been tested and verified

- It must be clear and concise

- Its assertions or predictions must be different and better than those in existing theories

- Its predictions must be general enough to be applicable to and understood within multiple contexts

- Its assertions or predictions are relevant, and if applied as predicted, will result in the predicted outcome

- The assertions and predictions are not immutable, but subject to revision and improvement as researchers use the theory to make sense of phenomena

- Its concepts and principles explain what is going on and why

- Its concepts and principles are substantive enough to enable us to predict a future

Given these characteristics, a theory can best be understood as the foundation from which you investigate assumptions or predictions derived from previous studies about the research problem, but in a way that leads to new knowledge and understanding as well as, in some cases, discovering how to improve the relevance of the theory itself or to argue that the theory is outdated and a new theory needs to be formulated based on new evidence.

A theoretical framework consists of concepts and, together with their definitions and reference to relevant scholarly literature, existing theory that is used for your particular study. The theoretical framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research paper and that relate to the broader areas of knowledge being considered.

The theoretical framework is most often not something readily found within the literature . You must review course readings and pertinent research studies for theories and analytic models that are relevant to the research problem you are investigating. The selection of a theory should depend on its appropriateness, ease of application, and explanatory power.

The theoretical framework strengthens the study in the following ways :

- An explicit statement of theoretical assumptions permits the reader to evaluate them critically.

- The theoretical framework connects the researcher to existing knowledge. Guided by a relevant theory, you are given a basis for your hypotheses and choice of research methods.

- Articulating the theoretical assumptions of a research study forces you to address questions of why and how. It permits you to intellectually transition from simply describing a phenomenon you have observed to generalizing about various aspects of that phenomenon.

- Having a theory helps you identify the limits to those generalizations. A theoretical framework specifies which key variables influence a phenomenon of interest and highlights the need to examine how those key variables might differ and under what circumstances.

- The theoretical framework adds context around the theory itself based on how scholars had previously tested the theory in relation their overall research design [i.e., purpose of the study, methods of collecting data or information, methods of analysis, the time frame in which information is collected, study setting, and the methodological strategy used to conduct the research].

By virtue of its applicative nature, good theory in the social sciences is of value precisely because it fulfills one primary purpose: to explain the meaning, nature, and challenges associated with a phenomenon, often experienced but unexplained in the world in which we live, so that we may use that knowledge and understanding to act in more informed and effective ways.

The Conceptual Framework. College of Education. Alabama State University; Corvellec, Hervé, ed. What is Theory?: Answers from the Social and Cultural Sciences . Stockholm: Copenhagen Business School Press, 2013; Asher, Herbert B. Theory-Building and Data Analysis in the Social Sciences . Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1984; Drafting an Argument. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kivunja, Charles. "Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field." International Journal of Higher Education 7 (2018): 44-53; Omodan, Bunmi Isaiah. "A Model for Selecting Theoretical Framework through Epistemology of Research Paradigms." African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies 4 (2022): 275-285; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Trochim, William M.K. Philosophy of Research. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Jarvis, Peter. The Practitioner-Researcher. Developing Theory from Practice . San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

Strategies for Developing the Theoretical Framework

I. Developing the Framework

Here are some strategies to develop of an effective theoretical framework:

- Examine your thesis title and research problem . The research problem anchors your entire study and forms the basis from which you construct your theoretical framework.

- Brainstorm about what you consider to be the key variables in your research . Answer the question, "What factors contribute to the presumed effect?"

- Review related literature to find how scholars have addressed your research problem. Identify the assumptions from which the author(s) addressed the problem.

- List the constructs and variables that might be relevant to your study. Group these variables into independent and dependent categories.

- Review key social science theories that are introduced to you in your course readings and choose the theory that can best explain the relationships between the key variables in your study [note the Writing Tip on this page].

- Discuss the assumptions or propositions of this theory and point out their relevance to your research.

A theoretical framework is used to limit the scope of the relevant data by focusing on specific variables and defining the specific viewpoint [framework] that the researcher will take in analyzing and interpreting the data to be gathered. It also facilitates the understanding of concepts and variables according to given definitions and builds new knowledge by validating or challenging theoretical assumptions.

II. Purpose

Think of theories as the conceptual basis for understanding, analyzing, and designing ways to investigate relationships within social systems. To that end, the following roles served by a theory can help guide the development of your framework.

- Means by which new research data can be interpreted and coded for future use,

- Response to new problems that have no previously identified solutions strategy,

- Means for identifying and defining research problems,

- Means for prescribing or evaluating solutions to research problems,

- Ways of discerning certain facts among the accumulated knowledge that are important and which facts are not,

- Means of giving old data new interpretations and new meaning,

- Means by which to identify important new issues and prescribe the most critical research questions that need to be answered to maximize understanding of the issue,

- Means of providing members of a professional discipline with a common language and a frame of reference for defining the boundaries of their profession, and

- Means to guide and inform research so that it can, in turn, guide research efforts and improve professional practice.

Adapted from: Torraco, R. J. “Theory-Building Research Methods.” In Swanson R. A. and E. F. Holton III , editors. Human Resource Development Handbook: Linking Research and Practice . (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1997): pp. 114-137; Jacard, James and Jacob Jacoby. Theory Construction and Model-Building Skills: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Guilford, 2010; Ravitch, Sharon M. and Matthew Riggan. Reason and Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2017; Sutton, Robert I. and Barry M. Staw. “What Theory is Not.” Administrative Science Quarterly 40 (September 1995): 371-384.

Structure and Writing Style

The theoretical framework may be rooted in a specific theory , in which case, your work is expected to test the validity of that existing theory in relation to specific events, issues, or phenomena. Many social science research papers fit into this rubric. For example, Peripheral Realism Theory, which categorizes perceived differences among nation-states as those that give orders, those that obey, and those that rebel, could be used as a means for understanding conflicted relationships among countries in Africa. A test of this theory could be the following: Does Peripheral Realism Theory help explain intra-state actions, such as, the disputed split between southern and northern Sudan that led to the creation of two nations?

However, you may not always be asked by your professor to test a specific theory in your paper, but to develop your own framework from which your analysis of the research problem is derived . Based upon the above example, it is perhaps easiest to understand the nature and function of a theoretical framework if it is viewed as an answer to two basic questions:

- What is the research problem/question? [e.g., "How should the individual and the state relate during periods of conflict?"]

- Why is your approach a feasible solution? [i.e., justify the application of your choice of a particular theory and explain why alternative constructs were rejected. I could choose instead to test Instrumentalist or Circumstantialists models developed among ethnic conflict theorists that rely upon socio-economic-political factors to explain individual-state relations and to apply this theoretical model to periods of war between nations].