What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

Looking into the underlying causes of the Salem Witch Trials in the 17th century.

In February 1692, the Massachusetts Bay Colony town of Salem Village found itself at the center of a notorious case of mass hysteria: eight young women accused their neighbors of witchcraft. Trials ensued and, when the episode concluded in May 1693, fourteen women, five men, and two dogs had been executed for their supposed supernatural crimes.

The Salem witch trials occupy a unique place in our collective history. The mystery around the hysteria and miscarriage of justice continue to inspire new critiques, most recently with the recent release of The Witches: Salem, 1692 by Pulitzer Prize-winning Stacy Schiff.

But what caused the mass hysteria, false accusations, and lapses in due process? Scholars have attempted to answer these questions with a variety of economic and physiological theories.

The economic theories of the Salem events tend to be two-fold: the first attributes the witchcraft trials to an economic downturn caused by a “little ice age” that lasted from 1550-1800; the second cites socioeconomic issues in Salem itself.

Emily Oster posits that the “little ice age” caused economic deterioration and food shortages that led to anti-witch fervor in communities in both the United States and Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Temperatures began to drop at the beginning of the fourteenth century, with the coldest periods occurring from 1680 to 1730. The economic hardships and slowdown of population growth could have caused widespread scapegoating which, during this period, manifested itself as persecution of so-called witches, due to the widely accepted belief that “witches existed, were capable of causing physical harm to others and could control natural forces.”

Salem Village, where the witchcraft accusations began, was an agrarian, poorer counterpart to the neighboring Salem Town, which was populated by wealthy merchants. According to the oft-cited book Salem Possessed by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Village was being torn apart by two opposing groups–largely agrarian townsfolk to the west and more business-minded villagers to the east, closer to the Town. “What was going on was not simply a personal quarrel, an economic dispute, or even a struggle for power, but a mortal conflict involving the very nature of the community itself. The fundamental issue was not who was to control the Village, but what its essential character was to be.” In a retrospective look at their book for a 2008 William and Mary Quarterly Forum , Boyer and Nissenbaum explain that as tensions between the two groups unfolded, “they followed deeply etched factional fault lines that, in turn, were influenced by anxieties and by differing levels of engagement with and access to the political and commercial opportunities unfolding in Salem Town.” As a result of increasing hostility, western villagers accused eastern neighbors of witchcraft.

But some critics including Benjamin C. Ray have called Boyer and Nissenbaum’s socio-economic theory into question . For one thing –the map they were using has been called into question. He writes: “A review of the court records shows that the Boyer and Nissenbaum map is, in fact, highly interpretive and considerably incomplete.” Ray goes on:

Contrary to Boyer and Nissenbaum’s conclusions in Salem Possessed, geo graphic analysis of the accusations in the village shows there was no significant villagewide east-west division between accusers and accused in 1692. Nor was there an east-west divide between households of different economic status.

On the other hand, the physiological theories for the mass hysteria and witchcraft accusations include both fungus poisoning and undiagnosed encephalitis.

Linnda Caporael argues that the girls suffered from convulsive ergotism, a condition caused by ergot, a type of fungus, found in rye and other grains. It produces hallucinatory, LSD-like effects in the afflicted and can cause victims to suffer from vertigo, crawling sensations on the skin, extremity tingling, headaches, hallucinations, and seizure-like muscle contractions. Rye was the most prevalent grain grown in the Massachusetts area at the time, and the damp climate and long storage period could have led to an ergot infestation of the grains.

One of the more controversial theories states that the girls suffered from an outbreak of encephalitis lethargica , an inflammation of the brain spread by insects and birds. Symptoms include fever, headaches, lethargy, double vision, abnormal eye movements, neck rigidity, behavioral changes, and tremors. In her 1999 book, A Fever in Salem , Laurie Winn Carlson argues that in the winter of 1691 and spring of 1692, some of the accusers exhibited these symptoms, and that a doctor had been called in to treat the girls. He couldn’t find an underlying physical cause, and therefore concluded that they suffered from possession by witchcraft, a common diagnoses of unseen conditions at the time.

The controversies surrounding the accusations, trials, and executions in Salem, 1692, continue to fascinate historians and we continue to ask why, in a society that should have known better, did this happen? Economic and physiological causes aside, the Salem witchcraft trials continue to act as a parable of caution against extremism in judicial processes.

Editor’s note: This post was edited to clarify that Salem Village was where the accusations began, not where the trials took place.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Taking Slavery West in the 1850s

- Webster’s Dictionary 1828: Annotated

- Life in the Islands of the Dead

- Charles Darwin and His Correspondents: A Lifetime of Letters

Recent Posts

- Performing Memory in Refugee Rap

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The salem witch trials.

- Emerson W. Baker Emerson W. Baker Department of History, Salem State University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.324

- Published online: 07 July 2016

The Salem Witch Trials are one of the best known, most studied, and most important events in early American history. The afflictions started in Salem Village (present-day Danvers), Massachusetts, in January 1692, and by the end of the year the outbreak had spread throughout Essex County, and threatened to bring down the newly formed Massachusetts Bay government of Sir William Phips. It may have even helped trigger a witchcraft crisis in Connecticut that same year. The trials are known for their heavy reliance on spectral evidence, and numerous confessions, which helped the accusations grow. A total of 172 people are known to have been formally charged or informally cried out upon for witchcraft in 1692. Usually poor and marginalized members of society were the victims of witchcraft accusations, but in 1692 many of the leading members of the colony were accused. George Burroughs, a former minister of Salem Village, was one of the nineteen people convicted and executed. In addition to these victims, one man, Giles Cory, was pressed to death, and five died in prison. The last executions took place in September 1692, but it was not until May 1693 that the last trial was held and the last of the accused was freed from prison.

The trials would have lasting repercussions in Massachusetts and signaled the beginning of the end of the Puritan City upon a Hill, an image of American exceptionalism still regularly invoked. The publications ban issued by Governor Phips to prevent criticism of the government would last three years, but ultimately this effort only ensured that the failure of the government to protect innocent lives would never be forgotten. Pardons and reparations for some of the victims and their families were granted by the government in the early 18th century, and the legislature would regularly take up petitions, and discuss further reparations until 1749, more than fifty years after the trials. The last victims were formally pardoned by the governor and legislature of Massachusetts in 2001.

- Massachusetts

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, American History. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 21 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

Character limit 500 /500

Salem Witch Trials — the Witchcraft Hysteria of 1692

February 1692–May 1693

The Salem Witch Trials are a series of well-known investigations, court proceedings, and prosecutions that took place in Salem, Massachusetts over the course of 1692 and 1693.

This illustration by Howard Pyle depicts one of the accusers pointing at the accused and saying, “There is a flock of yellow birds around her head.” It is an example of the spectral evidence that was permitted at the trials. Image Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections .

Salem Witch Trials Summary

The Salem Witch Trials took place in colonial Massachusetts in 1692 and 1693 when people living in and around the town of Salem, Massachusetts were accused of practicing witchcraft or dealing with the Devil. The accusations were initially made by two young girls in the early part of the year.

By May, William Phips had been named Governor of Massachusetts and a new charter had been implemented. Initially, Phips responded to the accusations by setting up a special court — the Court of Oyer and Terminer — to hear the cases and to determine the fate of the accused.

Unfortunately, the court was controversial because they allowed “spectral” evidence — visions of ghosts, demons, and the Devil — to be entered into the proceedings. It seemed to fuel the hysteria, which was likely elevated by King William’s War, which was going on in New England at the same time.

By the fall, 19 men and women had been convicted and hanged, and another was pressed to death . Another man died from having heavy stones placed on him. Somewhere between 150 and 200 were in prison or had spent time in prison.

Governor Phips ended the special court in October after accusations were made against well-respected members of the community. In January 1693, the trials resumed, but under the Supreme Court of Judicature. Spectral evidence was not allowed, and most of the accused were found innocent of the witchcraft charges and released.

A handful of the people accused of witchcraft were convicted, but Governor Phips intervened in May 1693 and agreed to release them as long as they paid a fine. By the time the proceedings ended, it was the largest outbreak of witchcraft in Colonial America .

Salem Witch Trials Facts

Facts about the accusers in the salem witch trials.

Two young girls, Elizabeth Paris and Abigail Williams started to act in a strange manner, which included making strange noises and hiding from their parents and other adults.

Elizabeth Paris, known as Betty, was 9 years old. Her father was the Reverend Samuel Paris.

Abigail Williams was 11 years old. Reverend Paris was her uncle.

More young girls in Salem Village started to show similar symptoms, including 12-year-old Anne Putnam and 17-year-old Elizabeth Hubbard.

Facts About the Accused in the Salem Witch Trials

The first people accused of witchcraft were Tituba, an enslaved woman, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osborne.

Dorothy Good was the youngest person to be accused of witchcraft. She was 4 years old.

Facts About the Role and Testimony of Tituba in the Salem Witch Trials

Tituba is believed to be an enslaved woman from Central America, possibly from Barbados.

She lived in the home of Reverend Paris and had been taken to Massachusetts by Paris in 1680.

Tituba confessed to using witchcraft.

She testified that four women, including Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good, along with a man, had told her to hurt the children.

Her testimony convinced the people of Salem Village that witchcraft was rampant in the town.

Facts About People Convicted and Executed During the Salem Witch Trials

The first person to be executed was Bridget Bishop.

Over the course of the Salem Witch Trials, 19 people were hanged at Proctor’s Ledge, near Gallows Hill.

Another one of the accused, Giles Corey, refused to enter a plea before the court and was ordered to be pressed to death. He was laid down on the ground and had heavy boards placed on top of him. Then heavy rocks were set on the boards until he was crushed by the weight.

The charges against all victims of the Salem Witch Trials were eventually cleared.

The Special Court

The Court of Oyer and Terminer was the special court ordered to oversee the trials, as ordered by Governor William Phips.

Salem Witch Trials Significance

The Salem Witch Trials were important because they showed how quickly accusations and hysteria could spread through Colonial America. At the time, the Witch Trials also threatened the authority and stability of the new charter and government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, while King William’s War raged across New England and Acadia .

Salem Witch Trials APUSH — Notes and Study Guide

Use the following links and videos to study the Salem Witch Trials, King Willilam’s War, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Salem Witch Trials APUSH Definition

The Salem Witch Trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions that occurred in colonial Massachusetts between 1692 and 1693. The trials were a dark chapter in American history, characterized by mass hysteria and accusations of witchcraft. Numerous individuals, predominantly women, were accused of practicing witchcraft, leading to the execution of 20 people — 13 women and 7 men. The trials were fueled by social, religious, and political factors, partially driven by King William’s War, resulting in tragic consequences for the victims and their families.

Salem Witch Trials Video for APUSH Notes

This video from the Daily Bellringer provides a detailed look at the Salem Witch Trials.

Salem Witch Trials APUSH Terms and Definitions

William Phips — William Phips was the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Salem Witch Trials. He played a significant role in bringing an end to the trials by dissolving the Court of Oyer and Terminer, which was responsible for the majority of the convictions. Phips was concerned about the growing public skepticism and criticism surrounding the trials, prompting him to take decisive action and promote a more rational approach to handling alleged witches. He was also worried about the public perception the trials had, during a time of war.

Court of Oyer and Terminer — The Court of Oyer and Terminer was a special court established in 1692 to handle the cases of alleged witches in Salem and surrounding areas. The court was led by several judges, including William Stoughton, and it operated under a unique legal process that allowed spectral evidence, or testimonies of dreams and visions, to be admitted as valid evidence. This, along with other factors, contributed to a biased and unjust environment during the trials.

William Stoughton — William Stoughton was a prominent judge and the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He presided over the Court of Oyer and Terminer during the Salem Witch Trials. He played a pivotal role in the harsh convictions and sentencing of numerous accused individuals. His unwavering support for spectral evidence and his lack of leniency exacerbated the severity of the trials’ outcomes. After Phips dismissed the cases, Stoughton worked to have him removed as Governor.

Samuel Paris — Reverend Samuel Paris was the minister of Salem Village and one of the central figures in the initial events that sparked the witch trials. He was the father of Elizabeth Paris and the uncle of Abigail Williams, two young girls who experienced mysterious fits and claimed to be afflicted by witchcraft. His role as a religious authority and his support for the accusations fueled the hysteria, contributing to the escalation of the trials.

Elizabeth Paris — Elizabeth Paris was the nine-year-old daughter of Samuel Paris and one of the first accusers in the Salem Witch Trials. With her cousin Abigail Williams, she exhibited peculiar behaviors, including seizures and strange utterances, which were attributed to witchcraft. Their accusations against various individuals, especially Tituba, were instrumental in initiating the investigations and subsequent arrests.

Abigail Williams — Abigail Williams, the eleven-year-old cousin of Elizabeth Paris, was another crucial accuser during the Salem Witch Trials. Like her cousin, she displayed symptoms of bewitchment and was among the first to accuse others, leading to a chain reaction of allegations.

Anne Putnam — Anne Putnam was a teenage girl from Salem Village who actively participated in the trials as an accuser. She made numerous accusations against various individuals, contributing to the mounting hysteria. Her motivations for involvement remain a topic of historical debate, with some suggesting that personal grievances and religious fervor influenced her actions.

Tituba — Tituba was an enslaved woman from the Caribbean who worked in the household of Reverend Samuel Paris. She became one of the first individuals accused of practicing witchcraft after Elizabeth and Abigail accused her of bewitching them. Tituba’s origin and cultural differences contributed to her status as an outsider in Salem, making her an easy target for accusations. Under pressure, she confessed to being a witch and provided testimonies that increased the intensity of the trials.

Bridget Bishop — Bridget Bishop was the first person to be tried and executed during the Salem Witch Trials. She was known for her unconventional lifestyle and had been accused of witchcraft once before.

John Proctor — John Proctor was a respected farmer in Salem Village and one of the central figures in Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible,” which was based on the events of the witch trials. Proctor was accused of witchcraft after he spoke out against the proceedings, expressing skepticism about the legitimacy of the trials. His refusal to falsely confess and his unwavering integrity ultimately led to his tragic execution.

Giles Corey — Giles Corey was an elderly farmer who became entangled in the witch trials when his wife, Martha Corey, was accused of witchcraft. In a notable act of protest against the unjust proceedings, Corey refused to enter a plea in court, leading to a brutal form of punishment known as pressing. Corey died during the punishment.

King William’s War — King William’s War was a conflict between England and France that occurred from 1689 to 1697, overlapping with the time of the Salem Witch Trials. The war was part of a larger conflict known as the Nine Years’ War or the War of the Grand Alliance. Its impact on the region, including heightened tensions and security concerns, likely contributed to the climate of fear and paranoia in Salem, potentially influencing the outbreak of the witch trials.

Salem Witch Trials — Primary and Secondary Sources

- The Witchcraft Delusion of 1692 by Thomas Hutchinson , William Frederick Poole, and Richard Frothingham

- The Wonders of the Invisible World : Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New-England by Cotton Mather

- Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits Personating Men, Witchcrafts, Infallible Proofs of Guilt in Such as are Accused with the Crime by Increase Mather

- Written by Randal Rust

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Salem Witch Trials: What Caused the Hysteria?

By: Elizabeth Yuko

Published: September 26, 2023

Though the Salem witch trials were far from the only persecutions over witchcraft in 17th-century colonial America, they loom the largest in public consciousness and popular culture today. Over the course of several months in 1692, a total of between 144 and 185 women, children and men were accused of witchcraft, and 19 were executed after local courts found them guilty.

As the witch panic spread throughout the region that year, increasing numbers of people became involved with the trials—as accusers, the accused, local government officials, clergymen, and members of the courts.

What was happening in late 17th-century Massachusetts that prompted widespread community participation, and set the stage for the trials? Here are five factors behind how accusations of witchcraft escalated to the point of mass hysteria, resulting in the Salem witch trials.

1. Idea of Witchcraft as a Threat Was Brought From England

By the time the Salem witch trials began in 1692, the legal tradition of trying people suspected of practicing witchcraft had been well-established in Europe, where the persecution of witches took place from roughly the 15th through 17th centuries.

“Salem came at the tail end of a period of witch persecutions in Europe , just as the Enlightenment took hold,” says Lucile Scott , journalist and author of An American Covenant: A Story of Women, Mysticism and the Making of Modern America . “The English colonists imported these ideas of a witch to America with them, and prior to the events in Salem , [many] people had been indicted for witchcraft in [other parts of] New England .”

The accusations in Salem began in early 1692, when two girls , ages nine and 11, came down with a mysterious illness. “They were sick for about a month before their parents brought in a doctor, who concluded that it looked like witchcraft,” says Rachel Christ-Doane, the director of education at the Salem Witch Museum .

Looking back from the 21st century, it may seem unthinkable that a doctor would point to witchcraft as the cause of a patient’s illness, but Scott says that it was considered a legitimate diagnosis at the time.

“It’s hard for us to understand how real the devil and witches and the threat they posed were to the Puritans—or how important,” she explains. “Witchcraft was the second capital crime listed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s criminal code .”

2. Puritan Worldview Was Mainstream

When the Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, the first governor, John Winthrop, delivered a sermon famously proclaiming the colony “a Citty [sic] upon a Hill” —in this case, meaning a model Christian society with no separation of church and state. But as growing numbers of Quakers and Christians of other denominations arrived in Massachusetts, it became more religiously diverse .

“By the 1690s, God-fearing Puritans represented a smaller proportion of the population of New England than at any point in the 17th century,” says Kathleen M. Brown, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania and author of Good Wives, Nasty Wenches and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race, and Power in Colonial Virginia . “Even though percentage-wise, the Puritan influence was weaker than it had been earlier in the century, it was still leaving a big imprint on society.”

This included mainstream acceptance of Providence: the Puritans’ belief that the events of everyday life on Earth happened in accordance with God’s will.

“This was particularly true when they were talking about the fate of colonial settlements in the land grab, or disease epidemics that would sweep through and kill people, or a terrible storm,” Brown explains. “Providence, along with the notion that there was evil at work through Satan—[including] through the activities of witches who might turn to the devil to exert supernatural power—informed the way Puritans understood the natural world and the spiritual world.”

Similarly, despite their waning power, the Puritans’ societal structure remained firmly in place when the Salem witch trials began. “The Puritan colony was a very patriarchal and hierarchical place,” Scott says, noting that this included the view that people, particularly women, who stepped outside of their prescribed roles in society were looked upon with suspicion.

3. Accusations Didn’t Follow the Usual Patterns

Though accusations of witchcraft themselves weren’t out of the ordinary in colonial New England, those made in Salem in 1692 stood out, likely contributing to the panic that spread throughout the community.

“Witchcraft accusations normally happened quite sporadically and in some isolation,” Brown explains. “They rarely snowballed into a mass accusation with increasing numbers of people accusing and being accused.”

“If you look at the larger history of witchcraft, not just in North America, but in England and Scotland, usually men are the accusers of witches, especially in an outbreak,” says Brown, whose latest book Undoing Slavery: Bodies, Race, and Rights in the Age of Abolition was published in February 2023. “You don't really ever get girls and young women doing the accusations: that's actually anomalous for Salem.”

Though theories abound, there is still no consensus as to why girls and young women became the central accusers , she notes.

When a rare witchcraft outbreak did occur, Brown says that it broadened the scope of who might qualify as a potential witch. “More people would fall into the category of ‘accused witch,’ and more people jumped on the bandwagon of accusation,” she notes.

As the trials wore on, no one was exempt from suspicion. “At a certain point, accusations in Salem flew so freely, anyone, no matter their Puritan purity, might find themselves facing the gallows,” Scott says.

HISTORY Vault: Salem Witch Trials

Experts, historians, authors, and behavioral psychologists offer an in-depth examination of the facts and the mysteries surrounding the court room trials of suspected witches in Salem Village, Massachusetts in 1692.

4. Decades of Ongoing Violence Had Taken a Toll

When the Salem witch trials began in 1692, King Philip’s War , also known as Metacom’s Rebellion, was still fresh in the minds of the colonial settlers. The Native Americans’ last-ditch attempt to stop English colonization of their land officially concluded in 1676 , but the violent conflict and bloodshed had never ended on the northern border of the Massachusetts colony.

“The colonial settlers were still encroaching on land that had been in the hands of Native Americans for thousands of years, and Native peoples were hitting back,” Brown explains. “It wasn’t hard for Massachusetts Puritans to think about the devil embodied in what the Native Americans were doing, because they're not Christian, they’re in a mortal combat with Puritan Christianity and the whole colonial settler enterprise, and the Massachusetts Puritans really believed in their own divine mission.”

Along the same lines, when the colony’s leaders reflected on the poor job they had done defending its northern boundary, Brown says that it’s not much of a stretch to think that they understood it all to mean that God was trying to tell them something, and “doesn't seem to be very happy.”

5. Accusations Came at Time of Political Uncertainty

It would have been one thing for the Puritans to view the contagion of both the mysterious illness spreading amongst the young women of Salem, and the subsequent accusations of witchcraft, as a sign that God is angry and the devil is at work. However, as Brown points out, in order for those accusations to gain the kind of traction they had in Salem—making it to trial, and, eventually, imprisoning and executing people—there had to be widespread buy-in from public officials.

“You need ministers saying, ‘Yes, these are signs of the devil in our midst,’” Brown explains. “You need magistrates doing interrogations and deciding to lock people up in jail and put them on trial. You need judges who are willing to believe the spectral evidence. You need all of the official apparatus of government and of justice to be on board with it to produce the kind of outcome you get at Salem.”

According to some scholars, most notably, historian Mary Beth Norton , local leaders in Salem were so receptive to the accusations of witchcraft, and on board with implementing draconian laws and policies in part because of the precariousness of the Massachusetts colonial settlement at that time.

High-ranking Puritans were concerned about their church’s dwindling numbers. “By the time [the Salem witch trials] take place, the Puritans are less dominant politically, religiously [and] culturally,” Brown explains.

The final decades of the 17th century were a time of political uncertainty in Salem as well. In 1684, King Charles II of England revoked the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s charter . Seven years later, the new ruling monarchs, King William III and Queen Mary II, issued a new charter establishing the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and, at the urging of influential Puritan clergyman Increase Mather , appointed Maine-born William Phips governor of the colony.

By the time Mather and Phips returned to Massachusetts with the new charter in May 1692, Salem’s jails were already filled with people accused of practicing witchcraft.

“You can make the argument that the legal system [in place prior to May 1692 ] made it possible for the witch trials to happen,” says Christ-Doane. “They [didn’t] have a charter, and their courts were dysfunctional, and that allows them to make unusual procedural decisions that lead to so many people being convicted of witchcraft.”

This included relying heavily, and sometimes exclusively, on spectral evidence —or, testimony from witnesses claiming that the accused person appeared to them and caused them harm in a vision or dream—even though it was widely considered unacceptable in legal practice at the time.

According to Brown, the legal situation didn’t improve when Phips took over. “Phipps, as governor, was a gatekeeper for certain judicial processes,” she explains. This included establishing the Court of Oyer and Terminer on May 27, 1692, specifically to try people accused of witchcraft. “That was the beginning of the convictions and the executions ,” Brown adds.

On June 2, Bridget Bishop became the first person convicted of practicing witchcraft during the Salem witch trials; eight days later, she was the first to be executed .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Pre-Colonial Mass

- 17th Century Mass

- 18th Century Mass

- 19th Century Mass

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

The exact cause of the Salem Witch Trials has long remained a mystery. Like many historical events, figuring out what happened is one thing but trying to figure out why it happened is much harder.

Most historians agree though that there were probably many causes behind the Salem Witch Trials, according to Emerson W. Baker in his book A Storm of Witchcraft:

“What happened in Salem likely had many causes, and as many responses to those causes…While each book puts forward its own theories, most historians agree that there was no single cause for the witchcraft that started in Salem and spread across the region. To borrow a phrase from another tragic chapter of Essex County history, Salem offered a ‘perfect storm’ a unique convergence of conditions and events that produced what was by far the largest and most lethal witchcraft episode in American history.”

When it comes to the possible causes of the trials, two questions come to mind: what caused the “afflicted girls” initial symptoms and, also, what caused the witch trials to escalate the way that they did?

Although colonists had been accused of witchcraft before in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, it had never escalated to the level that Salem did, with hundreds of people locked up in jail and dozens executed. Why did Salem get so bad?

What we do know is that witches and the Devil were a very real concern to the Salem Villagers, as they were to many colonists.

But since Salem had been experiencing a number of hardships at the time, such as disease epidemics, war and political strife, it wasn’t hard to convince some of the villagers that witches were to blame for their misfortune. Once the idea took hold in the colony, things seemed to quickly got out of hand.

The following is a list of these theories and possible causes of the Salem Witch Trials:

Conversion Disorder:

Conversion disorder is a mental condition in which the sufferer experiences neurological symptoms which may occur due to a psychological conflict. Conversion disorder is also collectively known as mass hysteria.

Medical sociologist Dr. Robert Bartholomew states, in an article on Boston.com, that the Salem Witch Trials were “undoubtedly” a case of conversion disorder, during which “psychological conflict and distress are converted into aches and pains that have no physical origin.”

Trial of George Jacobs of Salem for Witchcraft, painting by Tompkins Harrison Matteson, circa 1855

Bartholomew believes what happened in Salem was most likely an example of a “motor-based hysteria” which is one of the two main forms of conversion disorder.

Professor Emerson W. Baker also suggests conversion disorder as a possibility in his book A Story of Witchcraft:

“Conversion disorder, one of several psychological conditions that Abigail Hobbs and other afflicted people might have suffered from in 1692, shows heightened awareness of one’s surroundings. Scholars have long noted the connections between the witchcraft outbreak and King William’s War , which raged on Massachusetts’s northern frontier and was responsible for the war hysteria that seems to have been present in Salem Village and throughout Essex County.”

Baker goes on to explain that many of the afflicted girls, such as Abigail Hobbs, Mercy Lewis, Susannah Sheldon and Sarah Churchwell, were all war refugees who had previously lived in Maine and had been personally affected by the war to the point were some of them may have been experiencing post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Ergot Poisoning:

In 1976, in an article in the scientific journal Science, Linda R. Caporael proposed that ergot may have caused the symptoms that the “afflicted girls” and other accusers suffered from.

Ergot is a fungus (Claviceps purpurea) that infects rye and other cereal grains and contains a byproduct known as ergotamine, which is related to LSD.

Ingesting ergotamine is known to cause a number of cardiovascular and/or neurological effects, such as convulsions, vomiting, crawling sensations on the skin, hallucinations, gangrene and etc.

Ergot tends to grow in warm, damp weather and those conditions were present in the 1691 growing season. In the fall, the infected rye would have been harvested and used to bake bread during the winter months, which is when the afflicted girl’s symptoms began.

Not everyone agrees with this theory though. Later in 1976, another article was published in the same journal refuting Caporeal’s claims, arguing that epidemics of convulsive ergotism have occurred almost exclusively in settlements where the locals suffered from severe vitamin A deficiencies and there was no evidence that Salem residents suffered from such a deficiency, especially since they lived in a small farming and fishing village with plenty of access to vitamin A rich foods like fish and dairy products.

The article also argued that the absence of any symptoms of gangrene in the “afflicted girls” further debunked this theory as did the lack of convulsive ergotism symptoms in other children in the village, especially given that young children under 10 years of age are particularly susceptible to convulsive ergotism and most of the “afflicted girls” were teens or pre-teens.

Other similar medical conditions that historians have proposed could have caused the afflicted girls symptoms include Encephalitis Lethargica, epilepsy, Lyme disease and a toxic weed called Devil’s Trumpet or locoweed but there is little evidence to support these theories either, according to Baker:

“Several other diseases have been put forward as possible culprits, ranging from encephalitis and lyme disease to what is known as ‘artic hysteria,’ yet none of these seem to fit, either. Many experts question the very existence of Artic hysteria, which results in such behavior as people stripping off their clothes and running naked across the wild tundra. The accounts mention no such streaking in Salem, and while the supposed symptoms of witchcraft began in January, more people showed symptoms in the spring and summer…Encephalitis, the result of an infection transmitted by mosquito bite, does not really seem plausible, given that the first symptoms of bewitchment appeared during winter. And while the bull’s-eye rash often produced on the skin by Lyme disease might explain the devil’s mark or witch’s teat, it falls short of accounting for the behavior of the afflicted. None of these suggested diseases fit because a close reading of the testimony suggests that the symptoms were intermittent. The afflicted had stretches when they acted perfectly normal, intersperse with acute fits.”

Cold Weather:

Historical records indicate that witch hunts occur more frequently during cold periods. This was the theory cited in economist Emily Oster’s senior thesis at Harvard University in 2004.

The theory states that the most active era of witchcraft trials in Europe coincided with a 400-year-long cold period known as the “little ice age.”

In her paper, Oster explains that as the climate varied from year to year during this cold period, the higher numbers of witchcraft accusations occurred during the coldest temperatures.

Baker also discusses this theory in his book A Storm of Witchcraft:

“The 1680s and 1690s were part of the Maunder Minimum, the most extreme weather of the Little Ice Age, a period of colder temperatures occurring roughly from 1400 to 1800. Strikingly cold winters and dry summers were common in these decades. The result was not just personal discomfort but increasing crop failures. Starting in the 1680s, many towns that had once produced an agricultural surplus no longer did so. Mixed farming began to give way to pastures and orchards. Once Massachusetts had exported foodstuffs; by the 1690s it was an importer of corn, wheat, and other cereal crops. Several scholars have noted the high correlation between eras of extreme weather in the Little Ice Age and outbreaks of witchcraft in Europe; Salem continues this pattern.”

Factionalism, Politics and Socio-Economics:

Salem was very divided due to disagreements between the villagers about local politics, religion and economics.

One of the many issues that divided the villagers was who should be the Salem Village minister. Salem Village had gone through three ministers in sixteen years, due to disputes over who was deemed qualified enough to have the position, and at the time of the trials they were arguing about the current minister Samuel Parris.

Rivalries between different families in Salem had also begun to sprout up in the town as did land disputes and other disagreements which was all coupled with the fact that many colonists were also uneasy because the Massachusetts Bay Colony had its charter revoked and then replaced in 1691 with a new charter that gave the crown much more control over the colony.

In their book Salem Possessed, Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum attribute the witch trials to this political, economic, and religious discord in Salem Village:

“Predictably enough, the witchcraft accusations of 1692 moved in channels which were determined by years of factional strife in Salem Village.”

Boyer and Nissenbaum go on to provide examples, such as the fact that Daniel Andrew and Philip English were accused shortly after they defeated one of the Putnams in an election for Salem Town selectmen.

They also point out that Rebecca Nurse was accused shortly after her husband, Francis, became a member of a village committee that took office in October of 1691 that was vehemently against Salem Village minister Samuel Parris, whom the Putnams were supporters of.

Although this theory seems plausible, other historians such as Elaine Breslaw in her book Tituba, the Reluctant Witch of Salem, points out that other towns in Massachusetts were going through similar difficult times but didn’t experience any witch hunts or mass hysteria:

“There is no doubt that a peculiar combination of social tensions, exacerbated by the factional conflict within the community of Salem Village, contributed to the atmosphere of fear so necessary for the advent of a witchscare. Charles Upham suggested this as a major cause and Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum have provided a brilliant analysis of the Salem community to support that argument. Indian warfare and the uncertainties related to the arrival of a new charter and new Governor in the two years before the witchhunt also added to the level of social stress. But other towns in frontier Massachusetts that experienced the same socio-economic-political difficulties did not spark a similar witchscare. Several communities suffering from less stress did suffer from contact with Salem as the witchscare virus spread. This contagion too was a unique aspect of the 1692 episode.”

There is a small possibility and some evidence to back up the theory that some of the accusers were lying and faking their symptoms, although historians don’t believe this was the case with all of the accusers.

Baker suggests though that fraud may have been a bigger problem in the witch trials than we realize:

“Ultimately, the question is whether the afflictions, and therefore the accusations, were genuine or deliberate acts of fraud. Not surprisingly, there is no agreement on the answer. Most historians acknowledge that some fakery took place at Salem. A close reading of the surviving court records and related documents suggests that more fraud took place than many cared to admit after the trials ended.”

In Charles W. Upham’s book, Salem Witchcraft, Upham also suggests it was fraud, describing the afflicted girls as liars and performers but also admits that he doesn’t know how much of it was fake and how much of it was real:

“For myself, I am unable to determine how much may be attributed to credulity, hallucination, and the delirium of excitement, or to deliberate malice and falsehood. There is too much evidence of guile and conspiracy to attribute all their actions and deliberations to delusion; and their conduct throughout was stamped with a bold assurance and audacious bearing…It will be seen that other persons were drawn to act with these ‘afflicted children,’ as they were called, some from contagious delusion, and some, as quite well proved, from a false, mischievous, and malignant spirit.”

Many of the accused also stated that they believed that the afflicted girls were lying or only pretending to be ill. One of the accused, John Alden, later gave an account of his trial during which he described a moment that he believed to reveal fraud:

“those wenches being present, who plaid their jugling tricks, falling down, crying out, and staring in peoples faces. The magistrates demanded of them several times, who it was of all the people in the room that hurt them? One of these accusers pointed several times at one Captain Hill, there present, but spake nothing; the same accuser had a man standing at her back to hold her up; he stooped down to her ear, then she cried out. Aldin, Aldin afflicted her; one of the magistrates asked her if she had ever seen Aldin, she answered no, he asked her how she knew it was Aldin? She said, the man told her so.”

Another girl, who was not identified in the court records, was actually caught lying in court during Sarah Good’s trial when she claimed Good’s spirit stabbed her with a knife, which she said broke during the attack, and then presented the broken blade from her clothing where Good allegedly stabbed her.

After the girl made this claim though, a young man stood up in the court and explained that the knife was actually his and that he broke it himself the day before, according Winfield S. Nevins in his book Witchcraft in Salem Village in 1692:

“There-upon a young man arose in the court and stated that he broke that very knife the previous day and threw away the point. He produced the remaining part of the knife. It was then apparent that the girl had picked up the point which he threw and put it in the bosom of her dress, whence she drew it to corroborate her statement that some one had stabbed her. She had deliberately falsified, and used the knife-point to reinforce the falsehood. If she was false in this statement, why not all of it? If one girl falsified, how do we know whom to believe?”

Bernard Rosenthal also points out in his book, Salem Story, several incidents where the afflicted girls appeared to be lying or faking their symptoms, such as when both Ann Putnam and Abigail Williams claimed George Jacobs was sticking them with pins and then presented pins as evidence or when both girls testified that they were together when they saw the apparition of Mary Easty, which makes it unlikely that the vision was a result of a hallucination or psychological disorder since they both claimed to have seen it at the same time.

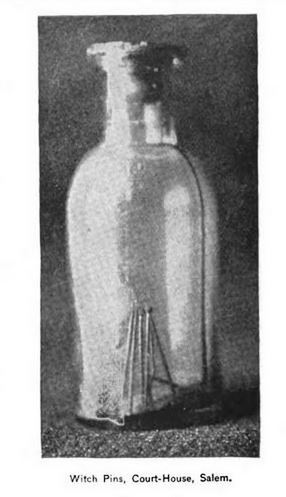

Witch Pins, Court House, Salem. Photo published in New England Magazine, vol. 12, circa 1892

Another example is various instances when the afflicted girls hands were found to be tied with rope while in court or when they were sometimes found bound and tied to hooks, according to Rosenthal:

“Whether the ‘afflicted’ worked these shows out among themselves or had help from others cannot be determined; but there is little doubt that such calculated action was deliberately conceived to perpetuate the fraud in which the afflicted were involved, and that the theories of hysteria or hallucination cannot account for people being bound, whether on the courtroom floor or on hooks.”

Reverend Samuel Parris:

Not only did some of the villagers believe the afflicted girls were lying, but they also felt that the Salem village minister, Reverend Samuel Parris , lied during the trials in order to punish his dissenters and critics.

Some historians have also blamed Reverend Samuel Parris for the witch trials, claiming he was the one who suggested to the Salem villagers that there were witches in Salem during a series of foreboding sermons in the winter of 1692, according to Samuel P. Fowler in his book An Account of the Life of Rev. Samuel Parris:

“We have been thus particular in relation to the settlement of Mr. Parris at Salem Village, it being one of the causes, which led to the most bitter parochial quarrel, that ever existed in New-England, and in the opinion of some persons, was the chief or primary cause of that world-wide famous delusion, the Salem Witchcraft.”

Parris, who was the latest in a series of Salem Village ministers that got caught in the middle of an ongoing dispute between the villagers, started to preach about infiltration and internal subversion of the church immediately after starting his new job, as can be seen in his very first sermon in which he preached “Cursed be he that doeth the work of the Lord deceitfully.”

Parris went on to preach to the villagers that the preservation of the church was “worth an hundred lives” and, during a sermon about Jehovah’s command to Samuel to destroy the Amalekites, he preached “a curse there is on such as shed not blood when they have a commission from God.”

Yet, Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, the authors of the book Salem Possessed, don’t agree that Parris started the witch hunt. They argue that while Parris had a significant role in the witch hysteria, he didn’t intentionally start a witch hunt:

“Samuel Parris did not deliberately provoke the Salem witchcraft episode. Nor, certainly, was he responsible for the factional conflict which underlay it. Nevertheless, his was a crucial role. He had a keen mind and a way with words, and Sunday after Sunday, in the little village meetinghouse, by the alchemy of typology and allegory, he took the nagging fears and conflicting impulses of his hearers and wove them into a pattern overwhelming in its scope, a universal drama in which Christ and Satan, Heaven and Hell, struggled for supremacy.”

After the trials were over, many of the Salem villagers felt Parris was responsible and some even protested by refusing to attend church while Parris was still minister there.

In February of 1693, these dissenters even presented a list of reasons they refused to attend the church, in which they accused Parris of dishonest and deceitful behavior during the trials and criticized his unchristian-like sermons:

“We found so frequent and positive preaching up some principles and practices by Mr. Parris, referring to the dark and dismal miseries of inquity, working amongst us, was not profitable but offensive…His approving and practicising unwarrantable and ungrounded methods, for discovering what he was desirous to know, referring to the bewitched or possessed persons, as in bringing some to others, and by and from them pretending to inform himself and others, who were the devil’s instruments to afflict the sick and pained…Sundry, unsafe, if sound, points of doctrine, delivered in his preaching, which we esteem not warrantable (if christian)…”

After two years of quarreling with parishioners, Parris was eventually dismissed sometime around 1696.

Although he was dismissed from his position, Parris refused to leave the Salem Village parsonage and after nine months the congregation sued him. During the lawsuit, the villagers again accused Parris of lying during the Salem Witch Trials, according to court records:

“We humbly conceive that he swears to more than he is certain of, is equally guilty of perjury with him that swears to what is false. And though they did fall at such a time, yet it could not be known that they did it, much less be certain of it; yet he did swear positively against the lives of such as he could not have any knowledge but they might be innocent. His believing the Devil’s accusations, and readily departing from all charity to persons, though of blameless and godly lives, upon such suggestions; his promoting such accusations; as also his partiality therein in stifling the accusations of some, and, at the same time, vigilantly promoting others, – as we conceive, are just causes for our refusal, & c.”

Parris responded by counter suing for the back pay the villagers had refused to pay him while he was minister. He eventually won the lawsuit and left Salem village shortly after.

Folk Magic:

English folk magic, which was the use of spells, ointments and potions to cure everyday ailments or solve problems, was often practiced in the Massachusetts Bay Colony even though it was frowned upon by most Puritans.

According to Beverly minister John Hale, in his book A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft, the afflicted girls symptoms began after one of them reportedly dabbled in a folk magic technique used to predict the future, known as the “Venus glass”:

“Anno 1692. I knew one of the afflicted persons, who (as I was credibly informed) did try with an egg and a glass to find her future husbands calling; till there came up a coffin, that is, a spectre in likeness of a coffin. And she was afterward followed with diabolical molestation to her death; and so died a single person. A just warning to others, to take heed of handling the Devils weapons, lest they get a wound nearby. Another I was called to pray with, being under some fits and vexations of Satan. And upon examination I found she had tried the same charm: and after her confession of it and manifestation of repentance for it, and our prayers to God for her, she was speedily released from those bonds of Satan.”

Cotton Mather, in his book Wonders of the Invisible World, also blamed folk magic as the cause of the Salem Witch Trials, stating that these practices invited the Devil into Salem:

“It is the general concession of all men that the invitation of witchcraft is the thing that has now introduced the Devil into the midst of us. The children of New England have secretly done many things that have been pleasing to the Devil. They say that in some towns it has been a usual thing for people to cure hurts with spells, or to use detestable conjurations with sieves, keys, peas, and nails, to learn the things for which they have an impious curiosity. ‘Tis in the Devil’s name that such things are done. By these courses ’tis that people play upon the hole of the asp, till that cruelly venomous asp has pulled many of them into the deep hole of witchcraft itself.”

Even though most colonists thought of folk magic as harmless, many well-known folk magic practitioners were quickly accused during the Salem Witch Trials, such as Roger Toothaker and his family who were self-proclaimed “witch killers” who used counter-magic to detect and kill witches.

Another accused witch who had dabbled in folk magic was Tituba, a slave of Samuel Parris who worked with her husband John and a neighbor named Mary Sibley to bake a witch cake, a cake made from rye meal and the afflicted girl’s urine, and then fed it to a dog in February of 1692 hoping it would reveal the name of whoever was bewitching the girls.

The girl’s symptoms took a turn for the worse after the incident and just a few weeks later, they named Tituba as a witch.

Tituba’s Confession:

The legal proceedings of the Salem Witch Trials began with the arrest of three women on March 1, 1692: Tituba, Sarah Good and Sarah Osbourne. After Tituba’s arrest, she was examined and tortured before confessing to the crime on March 5, 1692.

Although her confession doesn’t explain the afflicted girls initial symptoms, which is what led to her arrest in the first place, some historians believe that if it had not been for Tituba’s dramatic confession, during which she stated that she worked for the Devil and said that there were other witches like her in Salem, that the trials would have simply ended with the arrests of these three women.

When Tituba made her confession, the afflicted girls’ symptoms began to spread to other people and the accusations continued as the villagers began to seek out the other witches Tituba mentioned. According to Elaine G. Breslaw in her book Tituba, the Reluctant Witch of Salem, this was a pivotal moment in the trials:

“How she and her supposed conspirators, Sarah Osbourne and Sarah Good, responded to the accusations of the girls was of even greater importance to the course of events in March and the following months. Tituba’s confession is the key to understanding why the events of 1692 took on such epic significance.”

To learn more about the Salem Witch Trials, check out this article on the best books about the Salem Witch Trials .

Sources: Rosenthal, Bernard. Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692. Cambridge University Press, 1993. Nevins, Winfield S. Witchcraft in Salem Village in 1692: Together With Some Account of Other Witchcraft Prosecutions in New England and Elsewhere. Salem: North Shore Publishing Company, 1892. Breslaw, Elaine G. Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies. New York University Press, 1997 Upham, Charles W. Salem Witchcraft: With an Account of Salem Village and a History of Opinions on Witchcraft and Kindred Spirits. Wiggin and Lunt, 1867. 2 vols. Fowler, Samuel P. An Account of the Life, Character, & c. of the Rev. Samuel Parris, of Salem Village and Of His Connection With the Witchcraft Delusion of 1692. Salem: William Ives and George W. Pease, 1857. Baker, Emerson W. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience. Oxford University Press, 2014. Boyer, Paul and Stephen Nissenbaum. Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft. Harvard University Press, 1974. Spanos, Nicholas P. and Jack Gottlieb. “Ergotism and the Salem Witch Trials.” Science, 24 Dec. 1976, Vol. 194, Issue 4272, pp. 1390-1394. Edwards, Phil and Estelle Caswell. “The hallucinogens that might have sparked the Salem Witch Trials.” Vox, 29 Oct. 2015, www.vox.com/2015/10/29/9620542/salem-witch-trials-ergotism Sullivan, Walter. “New Study Backs Thesis on Witches.” New York Times, 29 Aug. 1992, www.nytimes.com/1982/08/29/us/new-study-backs-thesis-on-witches.html Mason, Robin. “Why Not Ergot and the Salem Witch Trials?” Witches of Massachusetts Bay, 23 April 2018, www.witchesmassbay.com/2018/04/23/why-not-ergot-and-the-salem-witch-trials/ “Witchcraft and the Indians.” Hawthorne in Salem, www.hawthorneinsalem.org/Literature/NativeAmericans&Blacks/HannahDuston/MMD2137.html Wolchover, Natalie. “Did Cold Weather Cause the Salem Witch Trials?” Live Science, 20 April 2012, www.livescience.com/19820-salem-witch-trials.html Norton, Mary Beth. In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. Vintage Books, 2003. Saxon, Victoria. “What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?” Jstor Daily, Jstor, 27 Oct. 2015, daily.jstor.org/caused-salem-witch-trials/

4 thoughts on “ What Caused the Salem Witch Trials? ”

I am a curious kid about the Salem Witch Trials, I’ve read many articles, and they mostly came from you, at least since 2011 until now. It’s impressive that you are still working really hard on this, I hope my comment can give you some more courage to keep this topic up.

aw how sweet.

Hello I think this is really informational. I do have a question though. Is there anyway the trials could of been caused by the fear of women?

Now that’s a proper article! I thought I’d never see such well-researched and well-written article!

And I don’t think it was the fear of women. I think it was the fear of unknown that caused this. The problem is that most of the actual witchcraft happened behind the scenes, so it’s hard to know what was really going on.

Comments are closed.

- Corrections

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

According to research, the Salem witch trials were triggered by a series of economic and physiological circumstances that created a perfect storm.

One of the most terrifying moments in our history, the Salem Witch trials took place in 1692 within the small village of Salem (present day Danvers) in Massachusetts. Around 200 men and women were accused of witchcraft, while 14 women, five men and even two dogs were found guilty and executed for a series of supposed supernatural crimes, a sequence of events that today have been attributed to a mass hysteria. But what caused the village to be whipped up into such a frenzy? Over the centuries, scholars have debated the possible causes that led to the infamous Salem witch trials , which range from the socio-economic to the physiological, as we outline below.

A Belief in Witches

The belief in humans acting as witches possessed by evil, supernatural powers had been around since at least the 14 th century. Running hand in hand with religions including Christianity, there was a widespread belief across Europe and the United States that witches received the power to cause ill intent through contact with the devil. The destructive ‘ witchcraft phase ’ was rampant across the Western world from the 14 th to the 17 th centuries, during which time many thousands of witches, predominantly women, were accused and executed. Within various early American communities, harsh living conditions such as illness, disease, bad weather and poverty were often attributed by community members to witchcraft , in a bid to make sense of the cruelties of the world in which they were living.

King William’s War

War broke out between English Monarchs William and Mary, and France in the American colonies in 1698, known today as King William’s War. Refugees fled from the worst affected areas in New York, Quebec and Nova Scotia into wider communities including Salem. This influx of new people put the small village of Salem under immense strain as the fight for limited resources turned bitter. The village’s most fundamental Puritans blamed the ensuing conflicts on the work of the devil, opening up an environment of terror.

Economic Hardships

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Various scholars believe the economic hardships caused by a “little ice-age” from 1550-1800 played a significant role in triggering the collective mindset that led to the Salem witch trials. The agricultural community of Salem was hit hard by these harsh weather conditions which destroyed many people’s livelihoods, led to mass food shortages, and slowed the population growth within the area. This, coupled with the belief that witches could control the forces of nature and even cause physical harm to people created a culture of fear, suspicion and scapegoating .

Divisions Between East and West Salem Village

In Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum’s book Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft, 1974, they argue that there was an east-west economic divide within the Village of Salem, with poorer families to the west, and wealthier families to the east, where they were nearer the town of Salem. In their version of events, it was Western villagers who became increasingly suspicious of their eastern neighbors, and began accusing them of witchcraft . They described this time period as a “mortal conflict involving the very nature of the community itself.” However, other critics have questioned this theory following deeper analysis of maps, arguing the socio-economic divisions between the village of Salem were not so clear cut.

Fungus Poisoning

When several young girls within Salem began experiencing strange, erratic behavior and unexplainable convulsive fits, locals immediately assumed the devil was at play. They blamed three women, including Tituba, an African slave, who confessed during a trial to signing a book with the devil in a bid to bring down the Christian communities of Salem. Her strange confession planted widespread fear and panic, leading to an ongoing ordeal of arrests and executions. The causes of the girls’ changes have been a subject of debate for centuries, but one of the most widespread and accepted theories is that the girls were suffering from a condition called convulsive ergotism, caused by a grain fungus prevalent in rye, which was one of Salem’s primary food sources.

Often stored in damp climates for extended periods, the infested grains could trigger a series of hallucinatory effects if consumed, including vertigo, seizures and skin-crawling sensations.

Brain Inflammation

Another possible cause for the girls’ symptoms as discussed by Laurie Winn Carlson in her book A Fever in Salem, 1999, was encephalitis lethargica, a brain inflammation caught from birds and insects. The symptoms of this rare phenomenon include behavioral changes, tremors and abnormal eye movements. Carlson notes that when a doctor was unable to explain the girls’ shared behaviors, he came to the conclusion that they had all been affected by witchcraft . Such medical diagnoses were unfortunately surprisingly common for unknown medical ailments, at a time when the fields of science and medicine were so full of fear and mystery.

6 Facts You Didn’t Know About the Salem Witch Trials

By Rosie Lesso MA Contemporary Art Theory, BA Fine Art Rosie is a contributing writer and artist based in Scotland. She has produced writing for a wide range of arts organizations including Tate Modern, The National Galleries of Scotland, Art Monthly, and Scottish Art News, with a focus on modern and contemporary art. She holds an MA in Contemporary Art Theory from the University of Edinburgh and a BA in Fine Art from Edinburgh College of Art. Previously she has worked in both curatorial and educational roles, discovering how stories and history can really enrich our experience of art.

Frequently Read Together

European Witch-Hunting (A Brief History)

Why Did Francisco Goya Paint Witches?

The Loudun Affair: Bizarre Witch Trials in France

The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear Thesis

Introduction, salem witch trials, explanation, works cited.

The most distinctive features of Modernism could be enumerated as Universality, development of Political thought, advent of technology and science, different inventions, approach towards Arts, literature, Specified Cultures, distinctive warfare and industry. There are several social and economic factors that make the Modern society different from the Pre Modern Society. Modernism a complex and intricate civilization but the Pre Modern society lacked all these elements and the major aspect of the society and religion was mostly superstition. The aspects of superstition, juxtaposed with entail of religion, was instrumental in every walks of life and this was an alter existence against clear thought process and science. (Knott, 188-9) This was the time in early American history when the fearsome cases of witch-hunt took place and one of the most terrifying incidents was the Salem Witch Trials.

In 1692 in the counties of the English ruled Massachusetts there were conducted a series of trials which meant to prosecute persons accused of practicing witchcraft in these areas. The outbreak began with the sudden and rather unusual illness of the daughter (Betty) and niece (Abigail) of the local Reverend Samuel Parris. Betty, aged 9 was the first to be affected and displayed what we would today call ‘hysterical’ behavior, often screaming and convulsing with pain, throwing things about and crawling around her room. She has also famously been quoted to have felt “pinched and pricked with pins”. To relive her of her strange affliction reverend Parris soon summoned the local doctor, (supposedly) William Griggs who sowed the first seed of trouble by suggesting that her illness was less physiological and more ‘supernatural’. (Kumar, 334)

Abigail Williams, 11, Parris’ orphaned niece complained of similar symptoms soon after Betty and promptly a handful of other girls all over the village displayed the same antics as Betty and Abigail. The people of the village of Salem were famous for their strict Puritanism. The neighboring revolutionary war (to which the Salem residents apparently contributed and war refugees from which probably took shelter in Salem) had left them even more attached to their faith. Death, war and a frantic return to religion provided a fertile ground for the re-emergence of some time tested superstitions. The timely intervention of the young girl’s ailment was exactly the sort of thing that would set a quiet village like Salem on fire.

Given their interest in the subject village girls often coupled together to ‘tell’ fortunes and practice divinations just to keep themselves busy during long idle evenings. Tituba, a young slave girl Parris had acquired from Barbados proved popular at such congregations due to her stock of mystical stories. Occasionally, she was also reported to have ‘told’ fortunes. Following Griggs’ ‘diagnosis’ the village quickly decided that Betty, Abigail and the other girl’s suffering was surely a result of witchcraft being practiced in the village. Residents quickly justified this allegation by referring to the recent loss of cattle and other such similar misfortunes and before long almost all the villagers were sure about witches inhabiting the same space as them.

Tituba was, predictably enough, the first person to be accused of practicing witchcraft. It could be stated that her sex, social status, proximity to the ‘victims’ and most importantly her ethnicity, though unfortunate, left her particularly vulnerable to the allegations. After her two other women Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, both social outcasts and unpopular were similarly accused of being witches. Ironically, while the two Sarah’s never accepted the allegations as true, Tituba soon confessed to being a witch. Sarah Osbourne later died in prison, the other two were later hanged to death. (Tyerman, 233-37)

Human Beings are naturally expressionistic. Thus, if repressed they consciously or subconsciously search for methods of self-expression. In an atmosphere as that of Salem in 1692 women were allowed little or no room to articulate their personal desires, as a result they remained eager to find means to attract attention and establish their existence. The unexplained affliction of the women in Salem has occupied much academic space. In the absence of any real medical evidence for this sort of collective suffering, most academicians and medical practitioners have time and again suggested that the symptoms exhibited by the girls were, in all probability an ‘act’, which the girls used to attract attention.

Young girls such as Abigail and Betty, who remain confined to their home doing little besides household chores such as sewing, cooking etc. crave the merriment of youth and the spotlight attached to it. Puritans however maintain that kids ‘should be seen and not heard’, and hence their values are often completely contradictory to what children usually want. Given the constant lack of attention received children often resort to tactics to attract the sort of attention they want. This tactics may be the sort that we are used to such as tantrums, crying, throwing things, holding their breath etc. or under certain circumstances it may also be what we otherwise call ‘pretension’ or ‘play acting’. (Prawer, 227-229)

The young girls in Salem were engaged, in all probability in such a mass play acting practice. It possibly began as an accident with Betty, but once she and those around her discovered the potential of being afflicted they too jumped into the bandwagon one by one. Each emulated the other and while in public eye used their sudden position of power to cause harm to and accuse everyone and anyone they despised or disliked in the most juvenile manner. It was a power play of the most childish kind, only it ended with about 19 innocent people being killed unnecessarily. (Powell, 49)

The witch hunt in Salem enflamed further with a sudden outbreak of a small pox epidemic, which many believed was the witches doing. As a result of these minor events the accusations flew till even the most unlikely of people came to be accused of being a witch. And then suddenly in 1693 the witch hunt died down much in the same way as it had begun, without a band but with a whimper. All those accused of practicing witchcraft were pronounced innocent (although this proclamation continued till early 20th century, until when the descendants of the accused fought to clear their ancestors’ name). Many of them were even accepted back within the folds of everyday life in Salem. Many others left forever and never returned to the place which maligned their reputation forever. (Manning, 115)

Not much is known of the Parris household except that they moved and that Abigail Williams never recovered from her affliction and died soon after. It can also be stated that the fact that Parris’ young son too died young and of insanity perhaps indicated a seed of lunacy which remained sown in the family. Academicians, psychologists and descendants of the accused and the victims have never quite figured out what happened during that rather eventful year in 1692 in the somnolent village of Salem. Even today it continues to intrigue people from all over the world like an unsolved mystery in the pages of time. (Powell, 53-55)

Knott, Paul. Development of Science: 15th C-17th C . Dakha: Dasgupta & Chatterjee, 1979.

Kumar, Hiranarayan. Power of Opportunity: Win Some, Lose None . Sydney: HBT & Brooks Ltd, 1988.

Manning, Charles. Principals and Practices: Human History . Wellington: National Book Trust, 1989.

Powell, Mark. Anatomy of Witch Hunts . Dunedin: ABP Ltd, 1991.

Prawer, Ali. Superstition’s Kingdom . Auckland: Allied Publishers, 2004.

Tyerman, John. Invention of the Crusades . Auckland: Allied Publications, 2001.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, July 6). The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-salem-witch-trials-a-time-of-fear/

"The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear." IvyPanda , 6 July 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-salem-witch-trials-a-time-of-fear/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear'. 6 July.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear." July 6, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-salem-witch-trials-a-time-of-fear/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear." July 6, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-salem-witch-trials-a-time-of-fear/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Salem Witch Trials: A Time of Fear." July 6, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-salem-witch-trials-a-time-of-fear/.

- Contrast Between Tituba and John Indian and Countering Racism

- Why Abigail Williams Is Blamed for the Salem Witch Trials

- A. Miller's "The Crucible" Play: Who Is to Blame?

- Analysis of the Movie The Crucible

- Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials

- The Grave Injustices of the Salem Witchcraft Trials

- Salem Witch Trials Causes

- Through Women’s Eyes: Salem Witch Trial

- Arthur Miller: Hypocrisy, Guilt, Authority, and Hysteria in "The Crucible"

- The Salem Witch Trials in American History

- US and Southeast Asia Affiliation

- Asian American Studies: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America

- Civilization’s ‘Blooming’ and Liberty Relationship

- U.S. Constitution, 17 September 1787

- Valley Forge in the Revolutionary War History

Did Cold Weather Cause the Salem Witch Trials?

Historical records indicate that, worldwide, witch hunts occur more often during cold periods, possibly because people look for scapegoats to blame for crop failures and general economic hardship. Fitting the pattern, scholars argue that cold weather may have spurred the infamous Salem witch trials in 1692.

The theory, first laid out by the economist Emily Oster in her senior thesis at Harvard University eight years ago, holds that the most active era of witchcraft trials in Europe coincided with a 400- year period of lower-than-average temperature known to climatologists as the "little ice age." Oster, now an associate professor of economics at the University of Chicago, showed that as the climate varied from year to year during this cold period, lower temperatures correlated with higher numbers of witchcraft accusations.

The correlation may not be surprising, Oster argued, in light of textual evidence from the period: popes and scholars alike clearly believed witches were capable of controlling the weather, and therefore, crippling food production.

The Salem witch trials fell within an extreme cold spell that lasted from 1680 and 1730 — one of the chilliest segments of the little ice age. The notion that weather may have instigated those trials is being revived by Salem State University historian Tad Baker in his forthcoming book, "A Storm of Witchcraft" (Oxford University Press, 2013). Building on Oster's thesis, Baker has found clues in diaries and sermons that suggest a harsh New England winter really may have set the stage for accusations of witchcraft.

According to the Salem News , one clue is a document that mentions a key player in the Salem drama, Rev. Samuel Parris, whose daughter Betty was the first to become ill in the winter of 1691-1692 because of supposed witchcraft. In that document, "Rev. Parris is arguing with his parish over the wood supply," Baker said. A winter fuel shortage would have made for a fairly miserable colonial home, and "the higher the misery quotient, the more likely you are to be seeing witches."

Psychology obviously played an important role in the Salem events; the young girls who accused their fellow townsfolk of witchcraft are believed to have been suffering from a strange psychological condition known as mass hysteria . However, the new theory suggests the hysteria may have sprung from dire economic conditions. "The witchcraft trials suggest that even when considering events and circumstances thought to be psychological or cultural, key underlying motivations can be closely related to economic circumstances," Oster wrote.