RELATED TOPICS

- Technical Writing Overview

- Types of Technical Writing

- Technical Writing Examples

- Freelance Technical Writing

- Technical Writer Style Guide Examples

- Technical Writing Jobs

- Subject Matter Expert

- Document Development Lifecycle

- Darwin Information Typing Architecture

- Technical Writer Career Path

- How to Become a Technical Writer

- Technical Writer Education Requirements

- English Teacher to Technical Writer

- Software Engineer to Technical Writer

- Technical Writer Salary

- Technical Writer Interview Questions

- Google Technical Writer Interview Questions

- Technical Writer Resume

- Technical Writer Cover Letter

- Technical Writer LinkedIn Profile

- Technical Writer Portfolio

- Senior Technical Writer Salary

- Senior Technical Writer Job Description

- Content Strategist

- How to Become a Content Strategist

- Content Strategist Skills

- Content Strategist Interview Questions

- Content Strategy Manager Overview

- Content Strategy in UX

- Content Strategist Portfolio Examples

- Content Design Overview

- Content Designer

- Content Designer Skills

- Content Design Books

- Technical Documentation

- Knowledge Base Documentation

- Product Documentation

- User Documentation

- Process Documentation

- Process Documentation Templates

- Good Documentation Practices

- HR Document Management Best Practices

- Software Documentation Examples

- How to Test Documentation Usability

- Document Control Overview

- Document Control Process

- Document Control Procedures

- Document Control Numbering

- Document Version Control

- Document Lifecycle Management

- Document Management Software Workflow

- Document Management Practices

- Github Document Management

- HR Document Management

- Confluence Document Management

- What is a Document Management System?

- Document Control Software

- Product Documentation Software

- HR Document Management Software

- Knowledge Base Software

- Internal Knowledge Base Software

- API Documentation Software Tools

- Knowledge Management Tools

- Document Management Software

- What is Software Documentation?

- How to Write Software Documentation

- How to Write API Documentation

- Document Manager

- Documentation Manager

- Documentation Specialist

- Document Control Manager Salary

- Business Writing Overview

- Business Writing Principles

- Best Business Writing Examples

- Best Business Writing Skills

- Best Business Writing Tips

- Types of Business Writing

- Best Business Writing Books

- What is Grant Writing?

- Grant Writing Process

- Grant Writing Templates

- Grant Writing Examples

- Grant Proposal Budget Template

- How to Write a Grant Proposal

- How to Write a Grant Proposal Cover Letter

- Grant Writing Books

- Grant Writer Role

- How to Become a Grant Writer

- Grant Writer Salary

- Grant Writer Resume

- Grant Writing Skills

- Grant Writer LinkedIn Profile

- Grant Writer Interview Questions

- Proposal Writing Overview

- How to Become a Proposal Writer

- Proposal Writer Role

- Proposal Writer Career Path

- RFP Proposal Writer

- Freelance Proposal Writer

- Remote Proposal Writer

- Government Proposal Writer

- Proposal Writer Salary

- Proposal Writer Job Description Example

- Proposal Writer Interview Questions

- How to Write a Proposal

- Proposal Writer LinkedIn Profile

- Business Proposal Examples

- UX Writing Overview

- Information Architecture

- Information Architecture vs Sitemap

- UX Writing Books

- UX Writing Examples

- UX Writer Overview

- Freelance UX Writer Overview

- UX Writer Career Path

- How to Become a UX Writer

- Google UX Writer

- UX Writer Interview Questions

- Google UX Writer Interview Questions

- UX Writer vs Copywriter

- UX Writer vs Technical Writer

- UX Writer Skills

- UX Writer Salary

- UX Writer Portfolio Examples

- UX Writer LinkedIn Profile

- UX Writer Cover Letter

- Knowledge Management Overview

- Knowledge Management System

- Knowledge Base Examples

- Knowledge Manager Overview

- Knowledge Manager Resume

- Knowledge Manager Skills

- Knowledge Manager Job Description

- Knowledge Manager Salary

- Knowledge Manager LinkedIn Profile

- Medical Writing Overview

- How to Become a Medical Writer

- Entry-Level Medical Writer

- Freelance Medical Writer

- Medical Writer Resume

- Medical Writer Interview Questions

- Medical Writer Salary

- Senior Medical Writer Salary

- Technical Writer Intern Do

- Entry-level Technical Writer

- Technical Writer

- Senior Technical Writer

- Technical Writer Editor

- Remote Technical Writer

- Freelance Technical Writer

- Software Technical Writer

- Pharmaceutical Technical Writer

- Google Technical Writer

- LinkedIn Technical Writer

- Apple Technical Writer

- Oracle Technical Writer

- Salesforce Technical Writer

- Amazon Technical Writer

- Technical Writing Certification Courses

- Certified Technical Writer

- UX Writer Certification

- Grant Writer Certification

- Proposal Writer Certification

- Business Writing Classes Online

- Business Writing Courses

- Grant Writing Classes Online

- Grant Writing Degree

Home › Writing › What is Technical Writing? › 8 Technical Writing Examples to Inspire You

8 Technical Writing Examples to Inspire You

Become a Certified Technical Writer

TABLE OF CONTENTS

As a technical writer, you may end up being confused about your job description because each industry and organization can have varying duties for you. At times, they may ask for something you’ve never written before. In that case, you can consider checking out some technical writing examples to get you started.

If you’re beginning your technical writing career, it’s advisable to go over several technical writing examples to make sure you get the hang of it. You don’t necessarily have to take a gander over at industry-specific examples; you can get the general idea in any case.

This article will go over what technical writing is and some of the common technical writing examples to get you started. If you’re looking to see some examples via video, watch below. Otherwise, skip ahead.

If you’re looking to learn via video, watch below. Otherwise, skip ahead.

Let’s start by covering what technical writing is .

What Exactly is Technical Writing?

Technical writing is all about easily digestible content regarding a specialized product or service for the public. Technical writers have to translate complex technical information into useful and easy-to-understand language.

There are many examples of technical writing, such as preparing instruction manuals and writing complete guides. In some cases, technical writing includes preparing research journals, writing support documents, and other technical documentation.

The idea is to help the final user understand any technical aspects of the product or service.

In other cases, technical writing means that the writer needs to know something. For example, pharmaceutical companies may hire medical writers to write their content since they have the required knowledge.

If you’re interested in learning more about these technical writing skills, then check out our Technical Writing Certification Course.

8 Technical Writing Examples to Get You Started

As a technical writer, you may have to learn new things continually, increase your knowledge, and work with new forms of content. While you may not have experience with all forms of technical writing, it’s crucial to understand how to do it.

If you learn all the intricacies of technical writing and technical documents, you can practically work with any form of content, given that you know the format.

Therefore, the following examples of technical writing should be sufficient for you to get an idea. The different types of technical writing have unique characteristics that you can easily learn and master effectively.

1. User Manuals

User manuals or instruction manuals come with various products, such as consumer electronics like televisions, consoles, cellphones, kitchen appliances, and more. The user manual serves as a complete guide on how to use the product, maintain it, clean it, and more. All technical manuals, including user manuals, have to be highly user-friendly. The technical writer has to write a manual to even someone with zero experience can use the product. Therefore, the target audience of user manuals is complete novices, amateurs, and people using the product/s for the first time.

Traditionally, user manuals have had text and diagrams to help users understand. However, user manuals have photographs, numbered diagrams, disclaimers, flow charts, sequenced instructions, warranty information, troubleshooting guides, and contact information in recent times.

Technical writers have to work with engineers, programmers, and product designers to ensure they don’t miss anything. The writer also anticipates potential issues ordinary users may have by first using the product. That helps them develop a first-hand experience and, ultimately, develop better user manuals.

The point of the user manual isn’t to predict every possible issue or problem. Most issues are unpredictable and are better handled by the customer support or help desk. User manuals are there to address direct and common issues at most.

You can check out some user manual examples and templates here . You can download them in PDF and edit them to develop an idea about how you can write a custom user manual for your product.

2. Standard Operating Procedures (SOP)

Standard operating procedures are complete processes for each organization’s various tasks to ensure smoother operations. SOPs help make each process more efficient, time-saving, and less costly.

An SOP document can include:

- Everything from the method of processing payroll.

- Hiring employees.

- Calculating vacation time to manufacturing guidelines.

In any case, SOPs ensure that each person in an organization works in unison and uniformly to maintain quality.

SOPs help eliminate irregularities, favoritism, and other human errors if used correctly. Lastly, SOPs make sure employees can take the responsibilities of an absent employee, so there’s no lag in work.

Therefore, developing SOPs requires a complete study of how an organization works and its processes.

Here are some examples of standard operating procedures you can study. You can edit the samples directly or develop your own while taking inspiration from them.

3. Case Studies & White Papers

Case studies and white papers are a way of demonstrating one’s expertise in an area. Case studies delve into a specific instance or project and have takeaways proving or disproving something. White papers delve into addressing any industry-specific challenge, issue, or problem.

Both case studies and white papers are used to get more business and leads by organizations.

Technical writers who write white papers and case studies need to be experts in the industry and the project itself. It’s best if the technical writer has prior experience in writing such white papers.

The writing style of white papers and case studies is unique, along with the formatting. Both documents are written for a specific target audience and require technical writing skills. Case studies are written in a passive voice, while white papers are written in an active voice. In any case, it’s crucial to maintain a certain level of knowledge to be able to pull it off.

You can check out multiple white paper examples here , along with various templates and guides. You can check out some examples here for case studies, along with complete templates.

4. API Documentation

API documentation includes instructions on effectively using and integrating with any API, such as web-API, software API, and SCPIs. API documentation contains details about classes, functions, arguments, and other information required to work with the API. It also includes examples and tutorials to help make integration easier.

In any case, API documentation helps clients understand how it works and how they can effectively implement API. In short, it helps businesses and people interact with the code more easily.

You can find a great example of proper API documentation in how Dropbox’s API documentation works. You can learn more about it here .

5. Press Releases

Press releases are formal documents issued by an organization or agency to share news or to make an announcement. The idea is to set a precedent for releasing any key piece of information in a follow-up press conference, news release, or on a social media channel.

The press release emphasizes why the information is important to the general public and customers. It’s a fact-based document and includes multiple direct quotes from major company stakeholders, such as the CEO.

Usually, press releases have a very specific writing process. Depending on the feasibility, they may have an executive summary or follow the universal press release format.

You can find several examples of press releases from major companies like Microsoft and Nestle here , along with some writing tips.

6. Company Documents

Company documents can include various internal documents and orientation manuals for new employees. These documents can contain different information depending on their use.

For example, orientation manuals include:

- The company’s history.

- Organizational chart.

- List of services and products.

- Map of the facility.

- Dress codes.

It may also include employee rights, responsibilities, operation hours, rules, regulations, disciplinary processes, job descriptions, internal policies, safety procedures, educational opportunities, common forms, and more.

Writing company documents requires good technical writing skills and organizational knowledge. Such help files assist new employees in settling into the company and integrating more efficiently.

Here are some great examples of orientation manuals you can check out.

7. Annual Reports

Annual reports are yearly updates on a company’s performance and other financial information. Annual reports directly correspond with company stakeholders and serve as a transparency tool.

The annual reports can also be technical reports in some cases. However, mostly they include stock performance, financial information, new product information, and key developments.

Technical writers who develop annual reports must compile all the necessary information and present it in an attractive form. It’s crucial to use creative writing and excellent communication skills to ensure that the maximum amount of information appears clearly and completely.

If the company is technical, such as a robotics company, the technical writer needs to develop a technical communication method that’s easy to digest.

You can check out some annual report examples and templates here .

8. Business Plans

Every company starts with a complete business plan to develop a vision and secure funding. If a company is launching a new branch, it still needs to start with a business plan.

In any case, the business plan has a few predetermined sections. To develop the ideal business plan, include the following sections in it.

- Executive Summary – includes the business concept, product, or service, along with the target market. It may also include information on key personnel, legal entity, founding date, location, and brief financial information.

- Product or Service Description – includes what the offering is, what value it provides, and what stage of development it is in currently.

- Team Members – includes all the information on the management team.

- Competitor and Market Analysis – includes a detailed analysis of the target market and potential competitors.

- Organizational System – includes information on how the organizational structure would work.

- Schedules – include start dates, hiring dates, planning dates, and milestones.

- Risks and Opportunities – include profit and loss predictions and projections.

- Financial Planning – includes planned income statements, liquidity measures, projected balance sheet, and more.

- Appendix – includes the organizational chart, resumes, patents, and more.

The technical writer needs to work closely with the company stakeholders to develop a complete business plan.

According to your industry, you can check out hundreds of business plan samples and examples here .

Becoming an Expert Technical Writer

Becoming an expert technical writer is all about focusing on your strengths. For example, you should try to focus on one to two industries or a specific form of technical writing. You can do various writing assignments and check out technical writing samples to understand what you’re good with.

You can also check out user guides and get online help in determining your industry. Once you’ve nailed down an industry and technical writing type, you can start to focus on becoming an expert in it.

In any case, it always helps to check out technical writing examples before starting any project. Try to check out examples of the same industry and from a similar company. Start your writing process once you have a complete idea of what you need to do.

Since technical writing involves dealing with complex information, the writer needs to have a solid base on the topic. That may require past experience, direct technical knowledge, or an ability to understand multiple pieces of information quickly and effectively.

In becoming a technical writer, you may have to work with various other people, such as software developers, software engineers, human resources professionals, product designers, and other subject matter experts.

While most organizations tend to hire writers with a history in their fields, others opt for individuals with great writing skills and team them up with their employees.

Technical writers may also work with customer service experts, product liability specialists, and user experience professionals to improve the end-user experience. In any case, they work closely with people to develop digestible content for the end customers.

Today, you can also find several technical writers online. There is an increasing demand for technical writing because of the insurgence of SaaS companies, e-commerce stores, and more.

In the end, technical writers need to have a strong grasp of proper grammar, terminology, the product, and images, graphics, sounds, or videos to explain documentation.

If you are new to technical writing and are looking to break-in, we recommend taking our Technical Writing Certification Course , where you will learn the fundamentals of being a technical writer, how to dominate technical writer interviews, and how to stand out as a technical writing candidate.

We offer a wide variety of programs and courses built on adaptive curriculum and led by leading industry experts.

- Work on projects in a collaborative setting

- Take advantage of our flexible plans and community

- Get access to experts, templates, and exclusive events

Become a Certified Technical Writer. Professionals finish the training with a full understanding of how to guide technical writer projects using documentation foundations, how to lead writing teams, and more.

Become a Certified UX Writer. You'll learn how to excel on the job with writing microcopy, content design, and creating conversation chatbots.

Become a Certified Grant Writer. In this course, we teach the fundamentals of grant writing, how to create great grant proposals, and how to stand out in the recruiting process to land grant writing jobs.

Please check your email for a confirmation message shortly.

Join 5000+ Technical Writers

Get our #1 industry rated weekly technical writing reads newsletter.

Your syllabus has been sent to your email

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Understanding Assignment Expectations

Dawn Atkinson

Chapter Overview

To craft a well-written technical document, you must first understand expectations for the piece in terms of purpose, audience, genre, writing style, content, design, referencing style, and so forth. This same truth applies to an academic assignment: you will be able to proceed with your writing task in a more straightforward way if you dedicate some time to understanding what the assignment asks before you begin to plan and write it. This chapter aims to help you deconstruct writing assignment prompts—in other words, carefully consider them by looking closely at their component parts—and use specifications, feedback, and rubrics to meet assignment requirements. Using the definition provided by Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation (2019, para. 1), a rubric specifies how levels of skillfulness on an assignment relate to grading criteria and, thus, to performance standards.

What does the assignment ask you to do?

College professors oftentimes provide students with directions or prompts that outline requirements for assignments. Read these instructions thoroughly when you first receive them so that you have time to clear up any uncertainties before the assignment is due. While reading, look for words that will help you focus on the task at hand and define its scope; many assignment instructions use key words or phrases, such as those presented in the following list, which is adapted from Learn Higher (2015, “Key Words in the Title”), to establish expectations.

The words and phrases listed indicate the purpose for an assignment and communicate what it should contain (its content). Use the list to clarify your task for the assignment; however, if you are still not sure what the assignment asks you to do after identifying its key words and phrases and defining their meanings, arrange an appointment with your instructor to discuss your questions. Think of your instructor as a vital resource who can help to clarify your uncertainties and support your academic success.

What are the assignment specifications?

In addition to looking for key words and phrases in your assignment directions, also pay attention to other specifics that communicate expectations. The following list, adapted from Learn Higher (2019, “Be Practical”), identifies such specifics.

- When is the assignment due?

- Do you need to submit a draft before you submit the final copy for grading? If so, when is the draft due?

- Are you required to submit a paper copy of the assignment, an electronic copy, or both?

- What is the word limit?

- Are you required to use sources? If so, what kind and how many?

- What referencing style are you required to use?

- Who is the audience for the assignment?

- What design requirements do you need to follow?

- Does the assignment specify that you should use a certain document type (a genre)?

Although the directions for your assignment may not provide specific directions about writing style, you can likely determine the level of formality expected in the document by identifying its genre. For example, essays, letters, and reports tend to use formal language to communicate confidently and respectfully with readers, whereas emails and social media posts may use less formal language since they offer quick modes of interaction.

What does past assignment feedback indicate about the instructor’s priorities?

If you have received feedback on past papers, look through the comments carefully to determine what the instructor considers important in terms of assignment preparation and grading. You may notice similar comments on multiple assignments, and these themes can point to things you have done well—and should thus aim to demonstrate in future assignments—and common areas for improvement. While reviewing the feedback, make a note of these themes so you can consult your notes when preparing upcoming assignments.

To avoid feeling overwhelmed by feedback, you might also prioritize the themes you intend to address in your next writing assignment by using a template, such as that provided in Figure 1, when making notes. If you have questions about past feedback comments when making notes, seek help before preparing your upcoming assignment.

What positive aspects of your past assignments do you want to demonstrate in your next assignment?

Punctuation (area for improvement): Which three punctuation issues do you intend to address when writing your next assignment? Record your responses below. In addition, locate pages in your textbook that will help you address these issues, and record the pages below.

Sentence construction (area for improvement): Which three sentence construction issues do you intend to address when writing your next assignment? Record your responses below. In addition, locate pages in your textbook that will help you address these issues, and record the pages below.

Citations and references (area for improvement): Which three citation and referencing issues do you intend to address when writing your next assignment? Record your responses below. In addition, locate pages in your textbook that will help you address these issues, and record the pages below.

Figure 1. Template for prioritizing feedback comments on past assignments

Most college writing instructors spend considerable time providing feedback on assignments and expect that students will use the feedback to improve future work. Show your instructor that you respect his or her effort, are invested in your course, and are taking responsibility for your own academic success by using past feedback to improve future assignment outcomes.

What assessment criteria apply to the assignment?

If your instructor uses a rubric to identify the grading criteria for an assignment and makes the rubric available to students, this resource can also help you understand assignment expectations. Although rubrics vary in format and content, in general they outline details about what an instructor is looking for in an assignment; thus, you can use a rubric as a checklist to ensure you have addressed assignment requirements.

Table 1 presents a sample rubric for a writing assignment. Notice that performance descriptions and ratings are identified in the horizontal cells of the table and grading criteria are listed in the vertical cells on the left side of the table.

Table 1. A sample writing assignment rubric

Although the rubrics you encounter may not look exactly like Table 1, the language used in a rubric can provide insight into what an instructor considers important in an assignment. In particular, pay attention to any grading criteria identified in the rubric, and consult these criteria when planning, editing, and revising your assignment so that your work aligns with the instructor’s priorities.

What can you determine about assignment expectations by reading an assignment sheet?

Spend a few minutes reviewing the example assignment sheet that follows, or review an assignment sheet that your instructor has distributed. Use the bullet list under the heading “What are the assignment specifications? ” to identify the specifics for the assignment.

Book Selection Email

Later this semester, you will be asked to produce a book review. To complete the assignment, you must select and read a non-fiction book about a science topic written for the general public. The current assignment requires you to communicate your book selection in an email message that follows standard workplace conventions.

Content Requirements

Address the following content points in your email message.

- Identify the book you intend to read and review.

- Tell the reader why you are interested in the book. For example, does it relate to your major? If so, how? Does it address an area that has not been widely discussed in other literature or in the news? Does it offer a new viewpoint on research that has already been widely publicized?

- Conclude by offering to supply additional information or answer the reader’s questions.

You will need to conduct some initial research to address the above points.

Formatting Requirements

Follow these guidelines when composing your email message.

- Provide an informative subject line that indicates the purpose for the communication.

- Choose an appropriate greeting, and end with a complimentary closing.

- Create a readable message by using standard capitalization and punctuation, skipping lines between paragraphs, and avoiding fancy typefaces and awkward font shifts.

- Use APA style when citing and referencing outside sources in your message.

Your instructor will read your email message. Please use formal language and a respectful tone when communicating with a professional.

Grading Category

This assignment is worth 10 points and will figure into your daily work/participation grade.

Submission Specifications and Due Date

Send your email to your instructor by noon on _______.

How will you respond to a case study about understanding assignment expectations?

We will now explore a case study that focuses on the importance of understanding assignment expectations. In pairs or small groups, examine the case and complete the following tasks:

- Identify what the student argues in his email and the reasoning and evidence he uses to support his argument.

- Discuss whether you agree with the student’s argument, and supply explanations for your answers.

- Identify possible solutions or strategies that would have prevented the problems discussed in the case study and the benefits that would have been derived from implementing the solutions.

- Present your group’s findings in a brief, informal presentation to the class.

Casey: The Promising Student Who Deflected Responsibility

Casey, a student with an impressive high school transcript, enrolled in an introduction to technical writing course his first semester in college. On the first day of class, the instructor discussed course specifics stated on the syllabus, and Casey noticed that she emphasized the following breakdown of how assignments, daily work/participation, and quiz grades would contribute to the students’ overall grades.

Instructions Assignment 10%

Report Assignment 15%

Critical Review Assignment 15%

Researched Argument Assignment 20%

Performance Evaluation Assignment 15%

Daily Work/Participation 10%

Quizzes 15%

Casey also noticed that the instructor had an attendance policy on the syllabus, so he decided that he should attend class regularly to abide by this policy.

During the semester, the instructor distributed directions for completing the five major course assignments listed above; these sheets provided details about the purpose, audience, genre, writing style, content, design, and referencing format for the assignments. Casey dutifully read through each assignment sheet when he received it and then filed it in his notebook. Although he completed all his course assignments on time, he did not earn grades that he considered acceptable in comparison to the high marks he received on his papers in high school.

When Casey did not receive the final grade he thought he deserved in his introduction to technical writing class, he sent his instructor an email that included the following text.

I am writing to you about why I deserve an A for my writing class. In my opinion, the requirements for an A should be attendance, on-time submission of assignments, and active participation in class activities.

Attendance is the most important factor in obtaining an A . Being in class helps with understanding course content—students can ask for clarification during class when they have doubts about topics covered in class. I think I deserve an A because I attended 27 out of 28 total class meetings during the semester.

On-time submission of assignments is another aspect that I feel I should be graded on. During the semester, I turned in all my assignments well before deadlines.

The third aspect that I think should be used in determination of my grade is active participation for all in-class activities. My consistent attendance in class indicates that I actively participated in all activities during class time.

After reviewing all the aspects I think are the prerequisites for an A , I feel that I deserve an A for my writing class.

After his instructor replied to the email by suggesting that Casey review the syllabus for further information about how his final grade was calculated, he complained bitterly to his friends about the instructor.

The university that Casey attended required students to complete end-of-course evaluations at the end of each semester. Upon receiving his final course grade in introduction to technical writing, he gave the instructor a poor review on the evaluation. In the review, he indicated that he oftentimes did not understand assignment requirements and was not sure who to turn to for help.

How will you demonstrate adherence to APA conventions?

To understand how to construct APA in-text citations and references in accordance with established conventions, review the following online modules.

- “APA Refresher: In-Text Citations 7th Edition” (Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020a) at https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-refresher/apa-refresher/in-text-citations/

- “APA Refresher: References 7th Edition” (Excelsior Online Writing Lab, 2020b) at https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-refresher/apa-refresher/references/

How will you relate the case study to points made in the rest of the chapter and in an essay?

Read an essay entitled “So You’ve Got a Writing Assignment. Now What?” (Hinton, 2010) at https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces1/hinton–so-youve-got-a-writing-assignment.pdf ; this essay expands upon a number of ideas raised in the current textbook chapter. Afterwards, write a response memo for homework. Address the items listed below in your memo, and cite and reference any outside sources of information that you use.

- Explain how the case study presented in this chapter relates to points made elsewhere in the chapter and in the essay in terms of understanding assignment expectations.

- Explain how this chapter, the case study, and the essay are relevant and useful to your own work in college. Do the texts offer new ways to approach writing assignments? Do they call into question unhelpful beliefs you hold about your own success in writing courses or in college? Do they offer solutions to problems you have encountered in college classes? How might you combine the points made in the texts with helpful practices you already demonstrate?

Consult the “Writing Print Correspondence” chapter of this textbook for guidance when writing and formatting your memo.

Remember to edit, revise, and proofread your document before submitting it to your instructor. The following multipage handout, produced by the Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo (n.d.), may help with these efforts.

https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/active_and_passive_voice_0.pdf

Active / Passive Voice

Strong, precise verbs are fundamental to clear and engaging academic writing. However, there is a rhetorical choice to be made about whether you are going to highlight the subject that performs the action or the action itself. In active voice , the subject of the sentence performs the action. In passive voice , the subject of the sentence receives the action. Recognizing the differences between active and passive voice, including when each is generally used, is a part of ensuring that your writing meets disciplinary conventions and audience expectations.

Helpful Tip: traditionally, writers in STEM fields have used passive voice because the performer of an action in a scientific document is usually less important than the action itself. In contrast, arts and humanities programs have stressed the importance of active voice. However, these guidelines are fluid, and STEM writers are increasingly using active voice in their writing. When in doubt, consult academic publications in your field and talk to your instructor – doing these things should give you a good sense of what’s expected.

Active voice explained

Active voice emphasizes the performer of the action, and the performer holds the subject position in the sentence. Generally, you should choose active voice unless you have a specific reason to choose passive voice (see below for those instances).

e.g., Participants completed the survey and returned it to the reader.

In the above sentence, the performer of the action (participants) comes before the action itself (completed).

Passive voice explained

Passive voice emphasized the receiver of the action, and the subject of the sentence receives the action. When using passive voice, the performer of the action may or may not be identified later in the sentence.

- e.g. The survey was completed. In the above sentence, the people who performed the action (those who completed the survey) are not mentioned.

Helpful Tip: One popular trick for detecting whether or not your sentence is in passive voice is to add the phrase by zombies after the verb in your sentence; if it makes grammatical sense, your sentence is passive. If not, your sentence is active. Passive: The trip was taken [by zombies]. Active: Mandy taught the class [by zombies].

When to choose passive voice

Deciding whether or not you should use passive voice depends on a number of factors, including disciplinary conventions, the preferences of your instructor or supervisor, and whether the performer of the action or the action itself is more important. Here are some general guidelines to help you determine when passive voice is appropriate:

- The performer is unknown or irrelevant e.g., The first edition of Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams was published in 1900.

- The performer is less important than the action e.g., The honey bees were kept in a humidified chamber at room temperature overnight.

The first sentence in the above quotation is active voice (where the performers want to be highlighted).

Helpful Tip: rhetorical choices often have an ethical dimension. For instance, passive voice may be used by people, organizations, or governments to obscure information or avoid taking direct responsibility. If someone says “the money was not invested soundly,” the decision to not identify the performer of the action (“the accountant did not invest the money soundly”) may be a deliberate one. For this reason, it is crucial that we question the choices we make in writing to ensure that our choices results in correct, clear, and appropriate messaging.

Converting passive voice to active voice

If you are proofreading in order to convert passive voice to active voice in your writing, it is helpful to remember that

- Active = performer of action + action

- Passive = action itself (may or may not identify the performer afterwards)

Here are some sample revisions:

- Passive: It is argued that… Active: Smith argues that…

- Passive: A number of results were shown… Active: These results show…

- Passive : Heart disease is considered the leading cause of death in North America. Active: Research points to heart disease as the leading cause of death in North America.

Eberly Center, Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation, Carnegie Mellon University. (2019). Grading and performance rubrics . https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/rubrics.html

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020a). APA Refresher: In-Text Citations 7th Edition [PowerPoint slides]. License: CC-BY 4.0 . https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-refresher/apa-refresher/in-text-citations/

Excelsior Online Writing Lab. (2020b). APA Refresher: References 7th Edition [PowerPoint slides]. License: CC-BY 4.0 . https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-refresher/apa-refresher/references/

Hinton, C.E. (2010). So you’ve got a writing assignment. Now what? In C. Lowe, & P. Zemliansky (Eds.), Writing spaces: Readings on writing (Vol. 1, pp. 18-32). Parlor Press. License: License: CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 . https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces1/hinton–so-youve-got-a-writing-assignment.pdf

Learn Higher. (2015). Instruction words in essay questions . License: CC-BY-SA 3.0 . http://www.learnhigher.ac.uk/learning-at-university/assessment/instruction-words-in-essay-questions/

Learn Higher. (2019). Assessment: Step-by-step . License: CC-BY-SA 3.0 . http://www.learnhigher.ac.uk/learning-at-university/assessment/assessment-step-by-step/

Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Active and passive voice . License: CC-BY-SA 4.0 . https://uwaterloo.ca/writing-and-communication-centre/sites/ca.writing-and-communication-centre/files/uploads/files/active_and_passive_voice_0.pdf

Mindful Technical Writing Copyright © 2020 by Dawn Atkinson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Technical Writing 101: What is it and How to Get Started

Technical writing is a specialized form of written communication that aims to make complex concepts understandable and accessible to a specific audience. As a freelancer, understanding and mastering this skill can significantly widen your career prospects. In this post, we’ll explore what technical writing is, why it’s important, and how you can get started. The world of technical writing can seem daunting at first, but with the right guidance and resources, anyone can learn how to effectively communicate complex information in a clear, concise manner.

Unpacking the Concept of Technical Writing

So, what exactly is technical writing? At its core, technical writing is a type of communication that uses language to convey technical or specialized topics in a way that is easy to understand. Think of it as the bridge between complex information and the people who need to understand that information. It’s all about breaking down complex concepts and presenting them in a way that is accessible to a specific audience.

One of the key characteristics of technical writing is its focus on clarity and accuracy. Technical writing is not about showcasing your vocabulary or using flowery language. Instead, it’s about getting straight to the point and providing accurate, useful information. This makes it different from other types of writing, such as creative writing or journalism, which may prioritize storytelling or persuasion.

Technical writing can take many forms, including user manuals, how-to guides, technical reports, white papers, and more. The goal is always the same: to make complex information understandable and usable.

Importance of Technical Writing in Today’s Digital Age

In our increasingly digital world, technical writing has become more important than ever. As technology continues to evolve and become more complex, the need for clear, understandable documentation and guides has increased. Whether it’s a user manual for a new piece of software, a technical report on a scientific study, or a guide to using a new piece of machinery, technical writing plays a crucial role in our society.

Technical writing is particularly important in sectors such as IT, healthcare, and manufacturing. In these industries, where complex machinery or software is common, the need for clear, concise instructions and documentation is paramount. A well-written user manual or guide can make the difference between a product being used correctly and efficiently, or not at all.

Moreover, in today’s digital age, businesses are increasingly relying on technical writers to help communicate their products and services to customers. Whether it’s through online help guides, product descriptions, or instructional videos, technical writers play a key role in helping businesses connect with their customers.

Skills Required for Effective Technical Writing

Technical writing is not just about understanding complex concepts and simplifying them for the audience. It also requires a unique set of skills that differentiate technical writers from other types of writers. In this section, we will discuss the essential skills that you need to develop to become an effective technical writer.

Written Communication Skills

At the core of technical writing is the ability to communicate effectively through written words. But what does this mean in practice? Let’s break it down.

Impeccable grammar: Technical writing is all about precision and clarity. Therefore, having a solid grasp of grammar is paramount. Errors in grammar can lead to confusion and misinterpretation, which is a big no-no in technical writing.

Good sentence structure: It’s not just what you say, but how you say it. A well-structured sentence can convey a complex idea simply and effectively. On the other hand, a poorly constructed sentence can make even a simple concept seem complicated.

Rich vocabulary: A good technical writer has a wide vocabulary at their disposal. This allows them to choose the most precise words to express their ideas, enhancing the clarity and effectiveness of their writing.

Are you confident in your grammar, sentence structure, and vocabulary? If not, don’t worry. These are skills that can be improved with consistent practice and learning.

Understanding of Technical Concepts

As a technical writer, you’ll often be tasked with explaining complex technical concepts to a non-technical audience. This requires a deep understanding of these concepts. But why is this so important?

Firstly, it allows you to break down complex information into simple, digestible chunks. Secondly, it gives you the ability to translate technical jargon into everyday language that your audience can understand. Lastly, it enables you to anticipate potential questions or confusion from your audience and address them proactively in your writing.

Understanding technical concepts doesn’t mean you need to be an expert in every field. Instead, it’s about having the curiosity and willingness to learn about new technologies and concepts, and the ability to understand them at a level that allows you to explain them simply and accurately.

Tools Used by Technical Writers

Technical writing is not just about the skills of the writer. It also involves the use of specific tools that help create, manage, and deliver technical information. Let’s take a look at some of the most commonly used tools in technical writing.

Microsoft Word: This is a staple in the toolkit of most writers, not just technical writers. It offers a wide range of features for creating and formatting documents, making it a versatile tool for many writing tasks.

Google Docs: This is a popular choice for collaborative writing projects. It allows multiple writers to work on a document simultaneously, making it easier to share ideas and make changes in real-time.

Diagramming tools: Diagrams are a common feature in technical documents, used to illustrate processes, systems, and relationships between concepts. Tools like Microsoft Visio, Lucidchart, and Draw.io can help you create clear and effective diagrams.

These are just a few examples of the tools used by technical writers. Depending on your specific needs and the nature of your work, you may also use other specialized software for tasks such as project management, version control, and document design.

Steps to Becoming a Technical Writer

Technical writing can seem intimidating at first, but it’s a skill that can be learned and honed over time. If you’re looking to transition into a career in technical writing, here’s a step-by-step guide to get you started:

1. Get a Degree: Although it’s not always required, having a degree in English, Journalism, Communications, or a related field can give you a leg up. Some technical writers also have degrees in fields like Engineering or Computer Science.

2. Gain Technical Knowledge: Depending on the industry you want to write for, you might need to learn specific technical skills or knowledge. For example, if you’re writing for a software company, you’ll need to understand how the software works.

3. Build Your Portfolio: Start creating samples of your technical writing. This could be anything from instruction manuals to how-to guides. A strong portfolio can show potential employers your writing ability and understanding of technical concepts.

4. Gain Experience: Look for internships or entry-level jobs that involve technical writing. This will help you gain practical experience and make valuable connections in the industry.

5. Keep Learning: The field of technical writing is always evolving. Stay updated with the latest trends and tools in the industry.

Tips for Improving Your Technical Writing Skills

Once you’ve made the decision to become a technical writer, you’ll want to continuously improve your skills. Here are some practical tips and strategies for enhancing your technical writing skills:

- Practice Makes Perfect: The more you write, the better you’ll get. Practice writing about different topics and in different formats.

- Get Feedback: Don’t be afraid to have others review your work. Constructive criticism can help you identify areas for improvement.

- Stay Organized: Good technical writing is clear and easy to follow. Make sure your writing is well-structured and logical.

- Keep It Simple: Remember, the goal of technical writing is to make complex information easy to understand. Avoid jargon and keep your language simple and direct.

- Keep Learning: Stay updated with the latest trends in the industry. This can help you stay relevant and improve your writing.

The Role of a Technical Writer in Project Management

In the realm of project management, the role of a technical writer is often underestimated. They are the silent heroes, diligently working behind the scenes to ensure smooth and effective communication within the team and with clients. Their contributions range from documenting project requirements to creating user manuals.

Firstly, technical writers play a crucial role in documenting project requirements . They work closely with project managers and stakeholders to understand and articulate the project’s objectives, specifications, and deliverables. This documentation serves as the backbone of the project, providing a clear roadmap for the team and ensuring everyone is on the same page.

Secondly, technical writers are responsible for creating user manuals and guides . These documents are essential for guiding end-users in navigating and utilizing the product or service. A well-written user manual can significantly enhance the user experience and contribute to the product’s success.

A table showing the tasks of a technical writer in project management.

Future Trends in Technical Writing

As we look to the future, several trends are set to shape the field of technical writing. These trends are largely driven by advancements in technology, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

One key trend is the rise of AI and machine learning in technical writing. These technologies are being used to automate routine tasks and improve the efficiency of technical writers. For example, AI can assist in generating content, proofreading, and even translating documents into different languages.

Another trend is the growing demand for interactive and multimedia content . As users increasingly expect engaging and interactive experiences, technical writers will need to adapt by incorporating elements such as videos, graphics, and interactive diagrams into their work.

A list of future trends in technical writing.

- AI and Machine Learning: Automating routine tasks and improving efficiency.

- Interactive and Multimedia Content: Incorporating engaging elements such as videos and interactive diagrams.

- Mobile-First Writing: Prioritizing mobile users by creating content that is easily readable on small screens.

- Personalized User Assistance: Using data to deliver personalized content and help to users.

- Localization: Adapting content to suit different cultures, languages, and regions.

Related posts:

- Fiverr Level 1 vs Fiverr Level 2 – What’s The Difference?

- How to Get Started in Voice Acting

- How Much Does Fiverr Charge Sellers?

- What to Include in an Email Signature

- Starting a Freelance Writing Career with No Experience

Get Organized & Win More Clients

Kosmo has everything you need to run your freelancing business.

Technical Writing for Beginners – An A-Z Guide to Tech Blogging Basics

If you love writing and technology, technical writing could be a suitable career for you. It's also something else you can do if you love tech but don’t really fancy coding all day long.

Technical writing might also be for you if you love learning by teaching others, contributing to open source projects and teaching others how to do so, too, or basically enjoy explaining complex concepts in simple ways through your writing.

Let's dive into the fundamentals and learn about what you should know and consider when getting started with technical writing.

Table of Contents

In this article, we’ll be looking at:

- What Technical writing is

Benefits of Technical Writing

- Necessary skills to have as a Technical Writer

The Technical Writing Process

- Platforms for publishing your articles

Technical Writing Courses

- Technical Writing forums and communities

- Some amazing technical writers to follow

- Final Words and references

What is Technical Writing?

Technical writing is the art of providing detail-oriented instruction to help users understand a specific skill or product.

And a technical writer is someone who writes these instructions, otherwise known as technical documentation or tutorials. This could include user manuals, online support articles, or internal docs for coders/API developers.

A technical writer communicates in a way that presents technical information so that the reader can use that information for an intended purpose.

Technical writers are lifelong learners. Since the job involves communicating complex concepts in simple and straightforward terms, you must be well-versed in the field you're writing about. Or be willing to learn about it.

This is great, because with each new technical document you research and write, you will become an expert on that subject.

Technical writing also gives you a better sense of user empathy. It helps you pay more attention to what the readers or users of a product feel rather than what you think.

You can also make money as a technical writer by contributing to organizations. Here are some organizations that pay you to write for them , like Smashing Magazine , AuthO , Twilio , and Stack Overflow .

In addition to all this, you can contribute to Open Source communities and participate in paid open source programs like Google Season of Docs and Outreachy .

You can also take up technical writing as a full time profession – lots of companies need someone with those skills.

Necessary Skills to Have as a Technical Writer

Understand the use of proper english.

Before you consider writing, it is necessary to have a good grasp of English, its tenses, spellings and basic grammar. Your readers don't want to read an article riddled with incorrect grammar and poor word choices.

Know how to explain things clearly and simply

Knowing how to implement a feature doesn't necessarily mean you can clearly communicate the process to others.

In order to be a good teacher, you have to be empathetic, with the ability to teach or describe terms in ways suitable for your intended audience.

If you can't explain it to a six year old, you don't understand it yourself. Albert Einstein

Possess some writing skills

I believe that writers are made, not born. And you can only learn how to write by actually writing.

You might never know you have it in you to write until you put pen to paper. And there's only one way to know if you have some writing skills, and that's by writing.

So I encourage you to start writing today. You can choose to start with any of the platforms I listed in this section to stretch your writing muscles.

And of course, it is also a huge benefit to have some experience in a technical field.

Analyze and Understand who your Readers are

The biggest factor to consider when you're writing a technical article is your intended/expected audience. It should always be at the forefront of your mind.

A good technical writer writes based on the reader’s context. As an example , let's say you're writing an article targeted at beginners. It is important not to assume that they already know certain concepts.

You can start out your article by outlining any necessary prerequisites. This will make sure that your readers have (or can acquire) the knowledge they need before diving right into your article.

You can also include links to useful resources so your readers can get the information they need with just a click.

In order to know for whom you are writing, you have to gather as much information as possible about who will use the document.

It is important to know if your audience has expertise in the field, if the topic is totally new to them, or if they fall somewhere in between.

Your readers will also have their own expectations and needs. You must determine what the reader is looking for when they begin to read the document and what they'll get out of it.

To understand your reader, ask yourself the following questions before you start writing:

- Who are my readers?

- What do they need?

- Where will they be reading?

- When will they be reading?

- Why will they be reading?

- How will they be reading?

These questions also help you think about your reader's experience while reading your writing, which we'll talk about more now.

Think About User Experience

User experience is just as important in a technical document as it is anywhere on the web.

Now that you know your audience and their needs, keep in mind how the document itself services their needs. It’s so easy to ignore how the reader will actually use the document.

As you write, continuously step back and view the document as if you're the reader. Ask yourself: Is it accessible? How will your readers be using it? When will they be using it? Is it easy to navigate?

The goal is to write a document that is both useful to and useable by your readers.

Plan Your Document

Bearing in mind who your users are, you can then conceptualize and plan out your document.

This process includes a number of steps, which we'll go over now.

Conduct thorough research about the topic

While planning out your document, you have to research the topic you're writing about. There are tons of resources only a Google search away for you to consume and get deeper insights from.

Don't be tempted to lift off other people's works or articles and pass it off as your own, as this is plagiarism. Rather, use these resources as references and ideas for your work.

Google as much as possible, get facts and figures from research journals, books or news, and gather as much information as you can about your topic. Then you can start making an outline.

Make an outline

Outlining the content of your document before expanding on it helps you write in a more focused way. It also lets you organize your thoughts and achieving your goals for your writing.

An outline can also help you identify what you want your readers to get out of the document. And finally, it establishes a timeline for completing your writing.

Get relevant graphics/images

Having an outline is very helpful in identifying the various virtual aids (infographics, gifs, videos, tweets) you'll need to embed in different sections of your document.

And it'll make your writing process much easier if you keep these relevant graphics handy.

Write in the Correct Style

Finally, you can start to write! If you've completed all these steps, writing should become a lot easier. But you still need to make sure your writing style is suitable for a technical document.

The writing needs to be accessible, direct, and professional. Flowery or emotional text is not welcome in a technical document. To help you maintain this style, here are some key characteristics you should cultivate.

Use Active Voice

It's a good idea to use active voices in your articles, as it is easier to read and understand than the passive voice.

Active voice means that the subject of the sentence is the one actively performing the action of the verb. Passive voice means that a subject is the recipient of a verb's action .

Here's an example of passive voice : The documentation should be read six times a year by every web developer.

And here's an example of active voice : Every web developer should read this documentation 6 times a year.

Choose Your Words Carefully

Word choice is important. Make sure you use the best word for the context. Avoid overusing pronouns such as ‘it’ and ‘this’ as the reader may have difficulty identifying which nouns they refer to.

Also avoid slang and vulgar language – remember you're writing for a wider audience whose disposition and cultural inclinations could differ from yours.

Avoid Excessive Jargon

If you’re an expert in your field, it can be easy to use jargon you're familiar with without realizing that it may be confusing to other readers.

You should also avoid using acronyms you haven't previously explained.

Here's an Example :

Less clear: PWAs are truly considered the future of multi-platform development. Their availability on both Android and iOS makes them the app of the future.

Improved: Progressive Web Applications (PWAs) are truly the future of multi-platform development. Their availability on both Android and iOS makes PWAs the app of the future.

Use Plain Language

Use fewer words and write in a way so that any reader can understand the text. Avoid big lengthy words. Always try to explain concepts and terms in the clearest way possible.

Visual Formatting

A wall of text is difficult to read. Even the clearest instructions can be lost in a document that has poor visual representation.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. This rings true even in technical writing.

But not just any image is worthy of a technical document. Technical information can be difficult to convey in text alone. A well-placed image or diagram can clarify your explanation.

People also love visuals, so it helps to insert them at the right spots. Consider the images below:

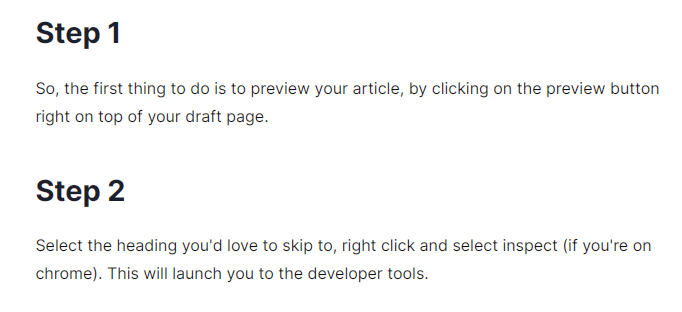

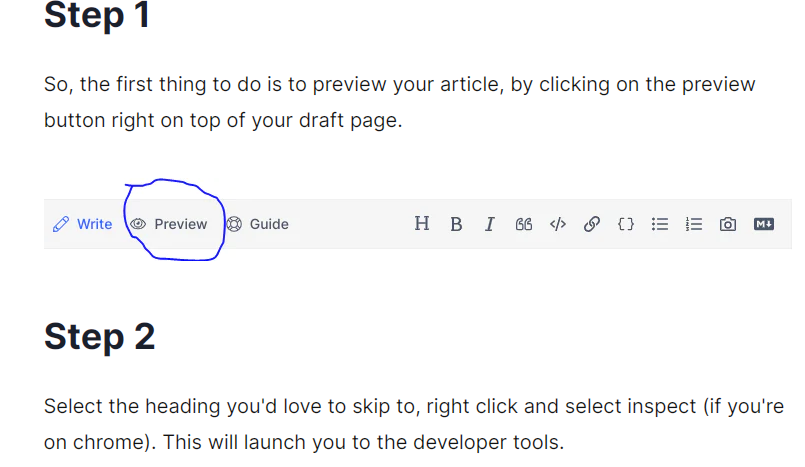

First, here's a blog snippet without visuals:

Here's a snippet of same blog, but with visuals:

Adding images to your articles makes the content more relatable and easier to understand. In addition to images, you can also use gifs, emoji, embeds (social media, code) and code snippets where necessary.

Thoughtful formatting, templates, and images or diagrams will also make your text more helpful to your readers. You can check out the references below for a technical writing template from @Bolajiayodeji.

Do a Careful Review

Good writing of any type must be free from spelling and grammatical errors. These errors might seem obvious, but it's not always easy to spot them (especially in lengthy documents).

Always double-check your spelling (you know, dot your Is and cross your Ts) before hitting 'publish'.

There are a number of free tools like Grammarly and the Hemingway app that you can use to check for grammar and spelling errors. You can also share a draft of your article with someone to proofread before publishing.

Where to Publish Your Articles

Now that you've decided to take up technical writing, here are some good platforms where you can start putting up technical content for free. They can also help you build an appealing portfolio for future employers to check out.

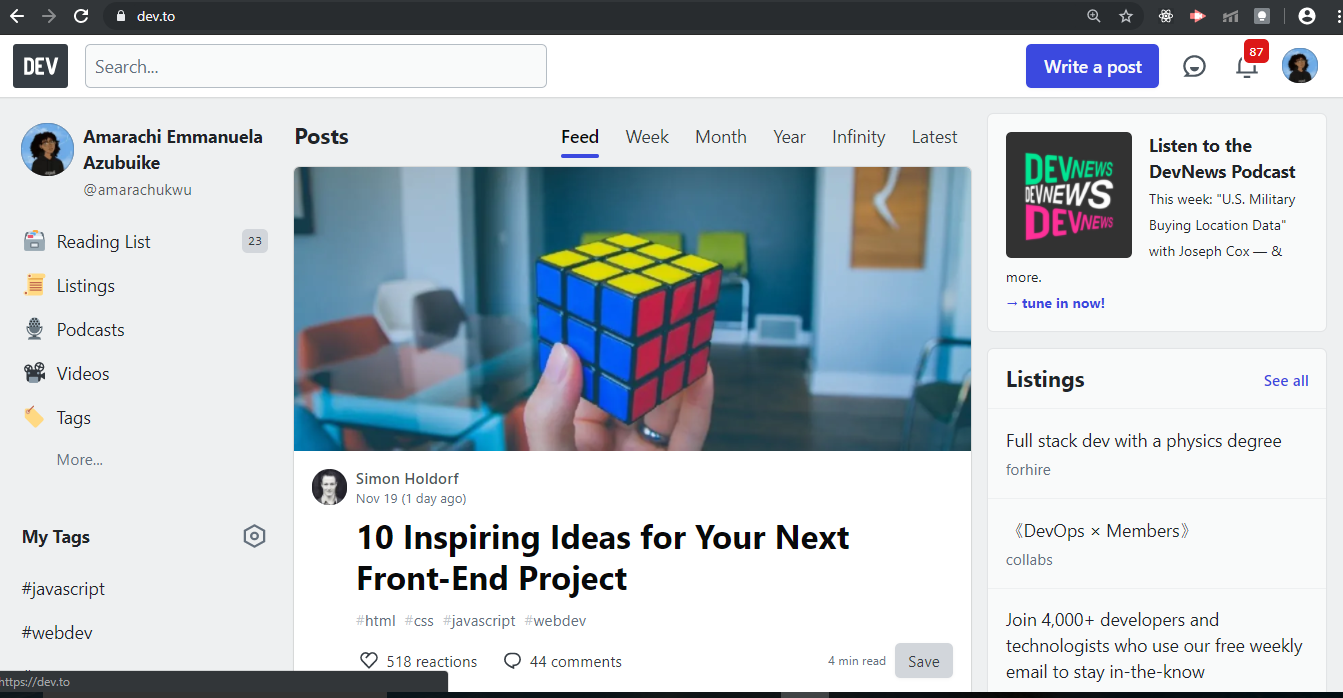

Dev.to is a community of thousands of techies where both writers and readers get to meaningfully engage and share ideas and resources.

Hashnode is my go-to blogging platform with awesome perks such as custom domain mapping and an interactive community. Setting up a blog on this platform is also easy and fast.

freeCodeCamp has a very large community and audience reach and is a great place to publish your articles. However, you'll need to apply to write for their publication with some previous writing samples.

Your application could either be accepted or rejected, but don't be discouraged. You can always reapply later as you get better, and who knows? You could get accepted.

If you do write for them, they'll review and edit your articles before publishing, to make sure you publish the most polished article possible. They'll also share your articles on their social media platforms to help more people read them.

Hackernoon has over 7,000 writers and could be a great platform for you to start publishing your articles to the over 200,000 daily readers in the community.

Hacker Noon supports writers by proofreading their articles before publishing them on the platform, helping them avoid common mistakes.

Just like in every other field, there are various processes, rules, best practices, and so on in Technical Writing.

Taking a course on technical writing will help guide you through every thing you need to learn and can also give you a major confidence boost to kick start your writing journey.

Here are some technical writing courses you can check out:

- Google Technical Writing Course (Free)

- Udemy Technical Writing Course (Paid)

- Hashnode Technical Writing Bootcamp (Free)

Technical Writing Forums and Communities

Alone we can do so little, together, we can do so much ~ Helen Keller

Being part of a community or forum along with people who share same passion as you is beneficial. You can get feedback, corrections, tips and even learn some style tips from other writers in the community.

Here are some communities and forums for you to join:

- Technical Writing World

- Technical Writer Forum

- Write the Docs Forum

Some Amazing Technical Writers to follow

In my technical writing journey, I've come and followed some great technical writers whose writing journey, consistency, and style inspire me.

These are the writers whom I look up to and consider virtual mentors on technical writing. Sometimes, they drop technical writing tips that I find helpful and have learned a lot from.

Here are some of those writers (hyperlinked with their twitter handles):

- Quincy Larson

- Edidiong Asikpo

- Catalin Pit

- Victoria Lo

- Bolaji Ayodeji

- Amruta Ranade

- Chris Bongers

- Colby Fayock

Final words

You do not need a degree in technical writing to start putting out technical content. You can start writing on your personal blog and public GitHub repositories while building your portfolio and gaining practical experience.

Really – Just Start Writing.

Practice by creating new documents for existing programs or projects. There are a number of open source projects on GitHub that you can check out and add to their documentation.

Is there an app that you love to use, but its documentation is poorly written? Write your own and share it online for feedback. You can also quickly set up your blog on hashnode and start writing.

You learn to write by writing, and by reading and thinking about how writers have created their characters and invented their stories. If you are not a reader, don't even think about being a writer. - Jean M. Auel

Technical writers are always learning . By diving into new subject areas and receiving external feedback, a good writer never stops honing their craft.

Of course, good writers are also voracious readers. By reviewing highly-read or highly-used documents, your own writing will definitely improve.

Can't wait to see your technical articles!

Introduction to Technical Writing

How to structure a technical article

Understanding your audience, the why and how

Technical Writing template

I hope this was helpful. If so, follow me on Twitter and let me know!

Amarachi is a front end web developer, technical writer and educator who is interested in building developer communities.

If you read this far, thank the author to show them you care. Say Thanks

Learn to code for free. freeCodeCamp's open source curriculum has helped more than 40,000 people get jobs as developers. Get started

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7. COMMON DOCUMENT TYPES

7.7 Writing Instructions

One of the most common and important uses of technical writing is to provide instructions, those step-by-step explanations of how to assemble, operate, repair, or do routine maintenance on something. Although they may seems intuitive and simple to write, instructions are some of the worst-written documents you can find. Most of us have probably had many infuriating experiences with badly written instructions. This chapter will show you what professionals consider the best techniques in providing instructions.

An effective set of instruction requires the following:

- Clear, precise, and simple writing

- A thorough understanding of the procedure in all its technical detail

- The ability to put yourself in the place of the reader, the person trying to use your instructions

- The ability to visualize the procedure in detail and to capture that awareness on paper

- Willingness to test your instructions on the kind of person you wrote them for.

Preliminary Steps

At the beginning of a project to write a set of instructions, it is important to determine the structure or characteristics of the particular procedure you are going to write about. Here are some steps to follow:

1. Do a careful audience and task analysis

Early in the process, define the audience and situation of your instructions. Remember that defining an audience means defining the level of familiarity your readers have with the topic.

2. Determine the number of tasks

How many tasks are there in the procedure you are writing about? Let’s use the term procedure to refer to the whole set of activities your instructions are intended to discuss. A task is a semi-independent group of actions within the procedure: for example, setting the clock on a microwave oven is one task in the big overall procedure of operating a microwave oven.

A simple procedure like changing the oil in a car contains only one task; there are no semi-independent groupings of activities. A more complex procedure like using a microwave oven contains several semi-independent tasks: setting the clock; setting the power level; using the timer; cleaning and maintaining the microwave, among others.

Some instructions have only a single task, but have many steps within that single task. For example, imagine a set of instructions for assembling a kids’ swing set. In my own experience, there were more than a 130 steps! That can be a bit daunting. A good approach is to group similar and related steps into phases, and start renumbering the steps at each new phase. A phase then is a group of similar steps within a single-task procedure. In the swing-set example, setting up the frame would be a phase; anchoring the thing in the ground would be another; assembling the box swing would be still another.

3. Determine the best approach to the step-by-step discussion

For most instructions, you can focus on tasks, or you can focus on tools (or features of tools). In a task approach (also known as task orientation) to instructions on using a phone-answering service, you’d have these sections:

- Recording your greeting

- Playing back your messages

- Saving your messages

- Forwarding your messages

- Deleting your messages, and so on

These are tasks—the typical things we’d want to do with the machine.

On the other hand, in a tools approach to instructions on using a photocopier, there likely would be sections on how to use specific features:

- Copy button

- Cancel button

- Enlarge/reduce button

- Collate/staple button

- Copy-size button, and so on

If you designed a set of instructions on this plan, you’d write steps for using each button or feature of the photocopier. Instructions using this tools approach are hard to make work. Sometimes, the name of the button doesn’t quite match the task it is associated with; sometimes you have to use more than just the one button to accomplish the task. Still, there can be times when the tools/feature approach may be preferable.

4. Design groupings of tasks

Listing tasks may not be all that you need to do. There may be so many tasks that you must group them so that readers can find individual ones more easily. For example, the following are common task groupings in instructions:

- Unpacking and setup tasks

- Installing and customizing tasks

- Basic operating tasks

- Routine maintenance tasks

- Troubleshooting tasks.

Common Sections in Instructions

The following is a review of the sections you’ll commonly find in instructions. Don’t assume that each one of them must be in the actual instructions you write, nor that they have to be in the order presented here, nor that these are the only sections possible in a set of instructions.

For alternative formats, check out the example instructions .

Introduction: plan the introduction to your instructions carefully. It might include any of the following (but not necessarily in this order):

- Indicate the specific tasks or procedure to be explained as well as the scope (what will and will not be covered)

- Indicate what the audience needs in terms of knowledge and background to understand the instructions

- Give a general idea of the procedure and what it accomplishes

- Indicate the conditions when these instructions should (or should not) be used

- Give an overview of the contents of the instructions.

General warning, caution, danger notices : instructions often must alert readers to the possibility of ruining their equipment, screwing up the procedure, and hurting themselves. Also, instructions must often emphasize key points or exceptions. For these situations, you use special notices —note, warning, caution, and danger notices. Notice how these special notices are used in the example instructions listed above.

Technical background or theory: at the beginning of certain kinds of instructions (after the introduction), you may need a discussion of background related to the procedure. For certain instructions, this background is critical—otherwise, the steps in the procedure make no sense. For example, you may have had some experience with those software applets in which you define your own colors by nudging red, green, and blue slider bars around. To really understand what you’re doing, you need to have some background on color. Similarly, you can imagine that, for certain instructions using cameras, some theory might be needed as well.

Equipment and supplies: notice that most instructions include a list of the things you need to gather before you start the procedure. This includes equipment , the tools you use in the procedure (such as mixing bowls, spoons, bread pans, hammers, drills, and saws) and supplies , the things that are consumed in the procedure (such as wood, paint, oil, flour, and nails). In instructions, these typically are listed either in a simple vertical list or in a two-column list. Use the two-column list if you need to add some specifications to some or all of the items—for example, brand names, sizes, amounts, types, model numbers, and so on.

Discussion of the steps: when you get to the actual writing of the steps, there are several things to keep in mind: (1) the structure and format of those steps, (2) supplementary information that might be needed, and (3) the point of view and general writing style.

Structure and format: normally, we imagine a set of instructions as being formatted as vertical numbered lists. And most are in fact. Normally, you format your actual step-by-step instructions this way. There are some variations, however, as well as some other considerations:

- Fixed-order steps are steps that must be performed in the order presented. For example, if you are changing the oil in a car, draining the oil is a step that must come before putting the new oil. These are numbered lists (usually, vertical numbered lists).