Essay Writing: A complete guide for students and teachers

P LANNING, PARAGRAPHING AND POLISHING: FINE-TUNING THE PERFECT ESSAY

Essay writing is an essential skill for every student. Whether writing a particular academic essay (such as persuasive, narrative, descriptive, or expository) or a timed exam essay, the key to getting good at writing is to write. Creating opportunities for our students to engage in extended writing activities will go a long way to helping them improve their skills as scribes.

But, putting the hours in alone will not be enough to attain the highest levels in essay writing. Practice must be meaningful. Once students have a broad overview of how to structure the various types of essays, they are ready to narrow in on the minor details that will enable them to fine-tune their work as a lean vehicle of their thoughts and ideas.

In this article, we will drill down to some aspects that will assist students in taking their essay writing skills up a notch. Many ideas and activities can be integrated into broader lesson plans based on essay writing. Often, though, they will work effectively in isolation – just as athletes isolate physical movements to drill that are relevant to their sport. When these movements become second nature, they can be repeated naturally in the context of the game or in our case, the writing of the essay.

THE ULTIMATE NONFICTION WRITING TEACHING RESOURCE

- 270 pages of the most effective teaching strategies

- 50+ digital tools ready right out of the box

- 75 editable resources for student differentiation

- Loads of tricks and tips to add to your teaching tool bag

- All explanations are reinforced with concrete examples.

- Links to high-quality video tutorials

- Clear objectives easy to match to the demands of your curriculum

Planning an essay

The Boys Scouts’ motto is famously ‘Be Prepared’. It’s a solid motto that can be applied to most aspects of life; essay writing is no different. Given the purpose of an essay is generally to present a logical and reasoned argument, investing time in organising arguments, ideas, and structure would seem to be time well spent.

Given that essays can take a wide range of forms and that we all have our own individual approaches to writing, it stands to reason that there will be no single best approach to the planning stage of essay writing. That said, there are several helpful hints and techniques we can share with our students to help them wrestle their ideas into a writable form. Let’s take a look at a few of the best of these:

BREAK THE QUESTION DOWN: UNDERSTAND YOUR ESSAY TOPIC.

Whether students are tackling an assignment that you have set for them in class or responding to an essay prompt in an exam situation, they should get into the habit of analyzing the nature of the task. To do this, they should unravel the question’s meaning or prompt. Students can practice this in class by responding to various essay titles, questions, and prompts, thereby gaining valuable experience breaking these down.

Have students work in groups to underline and dissect the keywords and phrases and discuss what exactly is being asked of them in the task. Are they being asked to discuss, describe, persuade, or explain? Understanding the exact nature of the task is crucial before going any further in the planning process, never mind the writing process .

BRAINSTORM AND MIND MAP WHAT YOU KNOW:

Once students have understood what the essay task asks them, they should consider what they know about the topic and, often, how they feel about it. When teaching essay writing, we so often emphasize that it is about expressing our opinions on things, but for our younger students what they think about something isn’t always obvious, even to themselves.

Brainstorming and mind-mapping what they know about a topic offers them an opportunity to uncover not just what they already know about a topic, but also gives them a chance to reveal to themselves what they think about the topic. This will help guide them in structuring their research and, later, the essay they will write . When writing an essay in an exam context, this may be the only ‘research’ the student can undertake before the writing, so practicing this will be even more important.

RESEARCH YOUR ESSAY

The previous step above should reveal to students the general direction their research will take. With the ubiquitousness of the internet, gone are the days of students relying on a single well-thumbed encyclopaedia from the school library as their sole authoritative source in their essay. If anything, the real problem for our students today is narrowing down their sources to a manageable number. Students should use the information from the previous step to help here. At this stage, it is important that they:

● Ensure the research material is directly relevant to the essay task

● Record in detail the sources of the information that they will use in their essay

● Engage with the material personally by asking questions and challenging their own biases

● Identify the key points that will be made in their essay

● Group ideas, counterarguments, and opinions together

● Identify the overarching argument they will make in their own essay.

Once these stages have been completed the student is ready to organise their points into a logical order.

WRITING YOUR ESSAY

There are a number of ways for students to organize their points in preparation for writing. They can use graphic organizers , post-it notes, or any number of available writing apps. The important thing for them to consider here is that their points should follow a logical progression. This progression of their argument will be expressed in the form of body paragraphs that will inform the structure of their finished essay.

The number of paragraphs contained in an essay will depend on a number of factors such as word limits, time limits, the complexity of the question etc. Regardless of the essay’s length, students should ensure their essay follows the Rule of Three in that every essay they write contains an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Generally speaking, essay paragraphs will focus on one main idea that is usually expressed in a topic sentence that is followed by a series of supporting sentences that bolster that main idea. The first and final sentences are of the most significance here with the first sentence of a paragraph making the point to the reader and the final sentence of the paragraph making the overall relevance to the essay’s argument crystal clear.

Though students will most likely be familiar with the broad generic structure of essays, it is worth investing time to ensure they have a clear conception of how each part of the essay works, that is, of the exact nature of the task it performs. Let’s review:

Common Essay Structure

Introduction: Provides the reader with context for the essay. It states the broad argument that the essay will make and informs the reader of the writer’s general perspective and approach to the question.

Body Paragraphs: These are the ‘meat’ of the essay and lay out the argument stated in the introduction point by point with supporting evidence.

Conclusion: Usually, the conclusion will restate the central argument while summarising the essay’s main supporting reasons before linking everything back to the original question.

ESSAY WRITING PARAGRAPH WRITING TIPS

● Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea

● Paragraphs should follow a logical sequence; students should group similar ideas together to avoid incoherence

● Paragraphs should be denoted consistently; students should choose either to indent or skip a line

● Transition words and phrases such as alternatively , consequently , in contrast should be used to give flow and provide a bridge between paragraphs.

HOW TO EDIT AN ESSAY

Students shouldn’t expect their essays to emerge from the writing process perfectly formed. Except in exam situations and the like, thorough editing is an essential aspect in the writing process.

Often, students struggle with this aspect of the process the most. After spending hours of effort on planning, research, and writing the first draft, students can be reluctant to go back over the same terrain they have so recently travelled. It is important at this point to give them some helpful guidelines to help them to know what to look out for. The following tips will provide just such help:

One Piece at a Time: There is a lot to look out for in the editing process and often students overlook aspects as they try to juggle too many balls during the process. One effective strategy to combat this is for students to perform a number of rounds of editing with each focusing on a different aspect. For example, the first round could focus on content, the second round on looking out for word repetition (use a thesaurus to help here), with the third attending to spelling and grammar.

Sum It Up: When reviewing the paragraphs they have written, a good starting point is for students to read each paragraph and attempt to sum up its main point in a single line. If this is not possible, their readers will most likely have difficulty following their train of thought too and the paragraph needs to be overhauled.

Let It Breathe: When possible, encourage students to allow some time for their essay to ‘breathe’ before returning to it for editing purposes. This may require some skilful time management on the part of the student, for example, a student rush-writing the night before the deadline does not lend itself to effective editing. Fresh eyes are one of the sharpest tools in the writer’s toolbox.

Read It Aloud: This time-tested editing method is a great way for students to identify mistakes and typos in their work. We tend to read things more slowly when reading aloud giving us the time to spot errors. Also, when we read silently our minds can often fill in the gaps or gloss over the mistakes that will become apparent when we read out loud.

Phone a Friend: Peer editing is another great way to identify errors that our brains may miss when reading our own work. Encourage students to partner up for a little ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’.

Use Tech Tools: We need to ensure our students have the mental tools to edit their own work and for this they will need a good grasp of English grammar and punctuation. However, there are also a wealth of tech tools such as spellcheck and grammar checks that can offer a great once-over option to catch anything students may have missed in earlier editing rounds.

Putting the Jewels on Display: While some struggle to edit, others struggle to let go. There comes a point when it is time for students to release their work to the reader. They must learn to relinquish control after the creation is complete. This will be much easier to achieve if the student feels that they have done everything in their control to ensure their essay is representative of the best of their abilities and if they have followed the advice here, they should be confident they have done so.

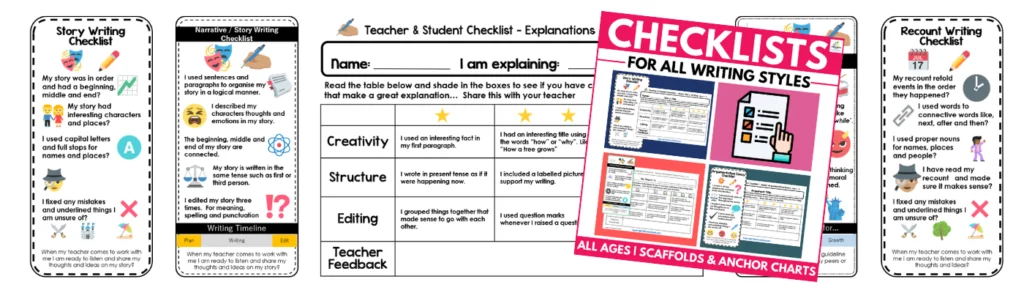

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

ESSAY WRITING video tutorials

Essay and dissertation writing skills

Planning your essay

Writing your introduction

Structuring your essay

- Writing essays in science subjects

- Brief video guides to support essay planning and writing

- Writing extended essays and dissertations

- Planning your dissertation writing time

Structuring your dissertation

- Top tips for writing longer pieces of work

Advice on planning and writing essays and dissertations

University essays differ from school essays in that they are less concerned with what you know and more concerned with how you construct an argument to answer the question. This means that the starting point for writing a strong essay is to first unpick the question and to then use this to plan your essay before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard).

A really good starting point for you are these short, downloadable Tips for Successful Essay Writing and Answering the Question resources. Both resources will help you to plan your essay, as well as giving you guidance on how to distinguish between different sorts of essay questions.

You may find it helpful to watch this seven-minute video on six tips for essay writing which outlines how to interpret essay questions, as well as giving advice on planning and structuring your writing:

Different disciplines will have different expectations for essay structure and you should always refer to your Faculty or Department student handbook or course Canvas site for more specific guidance.

However, broadly speaking, all essays share the following features:

Essays need an introduction to establish and focus the parameters of the discussion that will follow. You may find it helpful to divide the introduction into areas to demonstrate your breadth and engagement with the essay question. You might define specific terms in the introduction to show your engagement with the essay question; for example, ‘This is a large topic which has been variously discussed by many scientists and commentators. The principle tension is between the views of X and Y who define the main issues as…’ Breadth might be demonstrated by showing the range of viewpoints from which the essay question could be considered; for example, ‘A variety of factors including economic, social and political, influence A and B. This essay will focus on the social and economic aspects, with particular emphasis on…..’

Watch this two-minute video to learn more about how to plan and structure an introduction:

The main body of the essay should elaborate on the issues raised in the introduction and develop an argument(s) that answers the question. It should consist of a number of self-contained paragraphs each of which makes a specific point and provides some form of evidence to support the argument being made. Remember that a clear argument requires that each paragraph explicitly relates back to the essay question or the developing argument.

- Conclusion: An essay should end with a conclusion that reiterates the argument in light of the evidence you have provided; you shouldn’t use the conclusion to introduce new information.

- References: You need to include references to the materials you’ve used to write your essay. These might be in the form of footnotes, in-text citations, or a bibliography at the end. Different systems exist for citing references and different disciplines will use various approaches to citation. Ask your tutor which method(s) you should be using for your essay and also consult your Department or Faculty webpages for specific guidance in your discipline.

Essay writing in science subjects

If you are writing an essay for a science subject you may need to consider additional areas, such as how to present data or diagrams. This five-minute video gives you some advice on how to approach your reading list, planning which information to include in your answer and how to write for your scientific audience – the video is available here:

A PDF providing further guidance on writing science essays for tutorials is available to download.

Short videos to support your essay writing skills

There are many other resources at Oxford that can help support your essay writing skills and if you are short on time, the Oxford Study Skills Centre has produced a number of short (2-minute) videos covering different aspects of essay writing, including:

- Approaching different types of essay questions

- Structuring your essay

- Writing an introduction

- Making use of evidence in your essay writing

- Writing your conclusion

Extended essays and dissertations

Longer pieces of writing like extended essays and dissertations may seem like quite a challenge from your regular essay writing. The important point is to start with a plan and to focus on what the question is asking. A PDF providing further guidance on planning Humanities and Social Science dissertations is available to download.

Planning your time effectively

Try not to leave the writing until close to your deadline, instead start as soon as you have some ideas to put down onto paper. Your early drafts may never end up in the final work, but the work of committing your ideas to paper helps to formulate not only your ideas, but the method of structuring your writing to read well and conclude firmly.

Although many students and tutors will say that the introduction is often written last, it is a good idea to begin to think about what will go into it early on. For example, the first draft of your introduction should set out your argument, the information you have, and your methods, and it should give a structure to the chapters and sections you will write. Your introduction will probably change as time goes on but it will stand as a guide to your entire extended essay or dissertation and it will help you to keep focused.

The structure of extended essays or dissertations will vary depending on the question and discipline, but may include some or all of the following:

- The background information to - and context for - your research. This often takes the form of a literature review.

- Explanation of the focus of your work.

- Explanation of the value of this work to scholarship on the topic.

- List of the aims and objectives of the work and also the issues which will not be covered because they are outside its scope.

The main body of your extended essay or dissertation will probably include your methodology, the results of research, and your argument(s) based on your findings.

The conclusion is to summarise the value your research has added to the topic, and any further lines of research you would undertake given more time or resources.

Tips on writing longer pieces of work

Approaching each chapter of a dissertation as a shorter essay can make the task of writing a dissertation seem less overwhelming. Each chapter will have an introduction, a main body where the argument is developed and substantiated with evidence, and a conclusion to tie things together. Unlike in a regular essay, chapter conclusions may also introduce the chapter that will follow, indicating how the chapters are connected to one another and how the argument will develop through your dissertation.

For further guidance, watch this two-minute video on writing longer pieces of work .

Systems & Services

Access Student Self Service

- Student Self Service

- Self Service guide

- Registration guide

- Libraries search

- OXCORT - see TMS

- GSS - see Student Self Service

- The Careers Service

- Oxford University Sport

- Online store

- Gardens, Libraries and Museums

- Researchers Skills Toolkit

- LinkedIn Learning (formerly Lynda.com)

- Access Guide

- Lecture Lists

- Exam Papers (OXAM)

- Oxford Talks

Latest student news

CAN'T FIND WHAT YOU'RE LOOKING FOR?

Try our extensive database of FAQs or submit your own question...

Ask a question

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1900 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,008 quotes across 1900 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- June 2, 2022

- What is an essay?

What makes a good essay?

Typical essay structure, 7 steps to writing a good essay, a step-by-step guide to writing a good essay.

Whether you are gearing up for your GCSE coursework submissions or looking to brush up on your A-level writing skills, we have the perfect essay-writing guide for you. 💯

Staring at a blank page before writing an essay can feel a little daunting . Where do you start? What should your introduction say? And how should you structure your arguments? They are all fair questions and we have the answers! Take the stress out of essay writing with this step-by-step guide – you’ll be typing away in no time. 👩💻

What is an essay?

Generally speaking, an essay designates a literary work in which the author defends a point of view or a personal conviction, using logical arguments and literary devices in order to inform and convince the reader.

So – although essays can be broadly split into four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive – an essay can simply be described as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. 🤔

The purpose of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question and to persuade the reader that your position is credible, believable and reasonable. 👌

So, a ‘good’ essay relies on a confident writing style – it’s clear, well-substantiated, focussed, explanatory and descriptive . The structure follows a logical progression and above all, the body of the essay clearly correlates to the tile – answering the question where one has been posed.

But, how do you go about making sure that you tick all these boxes and keep within a specified word count? Read on for the answer as well as an example essay structure to follow and a handy step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay – hooray. 🙌

Sometimes, it is helpful to think about your essay like it is a well-balanced argument or a speech – it needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question in a coherent manner. ⚖️

Of course, essays can vary significantly in length but besides that, they all follow a fairly strict pattern or structure made up of three sections. Lean into this predictability because it will keep you on track and help you make your point clearly. Let’s take a look at the typical essay structure:

#1 Introduction

Start your introduction with the central claim of your essay. Let the reader know exactly what you intend to say with this essay. Communicate what you’re going to argue, and in what order. The final part of your introduction should also say what conclusions you’re going to draw – it sounds counter-intuitive but it’s not – more on that below. 1️⃣

Make your point, evidence it and explain it. This part of the essay – generally made up of three or more paragraphs depending on the length of your essay – is where you present your argument. The first sentence of each paragraph – much like an introduction to an essay – should summarise what your paragraph intends to explain in more detail. 2️⃣

#3 Conclusion

This is where you affirm your argument – remind the reader what you just proved in your essay and how you did it. This section will sound quite similar to your introduction but – having written the essay – you’ll be summarising rather than setting out your stall. 3️⃣

No essay is the same but your approach to writing them can be. As well as some best practice tips, we have gathered our favourite advice from expert essay-writers and compiled the following 7-step guide to writing a good essay every time. 👍

#1 Make sure you understand the question

#2 complete background reading.

#3 Make a detailed plan

#4 Write your opening sentences

#5 flesh out your essay in a rough draft, #6 evidence your opinion, #7 final proofread and edit.

Now that you have familiarised yourself with the 7 steps standing between you and the perfect essay, let’s take a closer look at each of those stages so that you can get on with crafting your written arguments with confidence .

This is the most crucial stage in essay writing – r ead the essay prompt carefully and understand the question. Highlight the keywords – like ‘compare,’ ‘contrast’ ‘discuss,’ ‘explain’ or ‘evaluate’ – and let it sink in before your mind starts racing . There is nothing worse than writing 500 words before realising you have entirely missed the brief . 🧐

Unless you are writing under exam conditions , you will most likely have been working towards this essay for some time, by doing thorough background reading. Re-read relevant chapters and sections, highlight pertinent material and maybe even stray outside the designated reading list, this shows genuine interest and extended knowledge. 📚

#3 Make a detailed plan

Following the handy structure we shared with you above, now is the time to create the ‘skeleton structure’ or essay plan. Working from your essay title, plot out what you want your paragraphs to cover and how that information is going to flow. You don’t need to start writing any full sentences yet but it might be useful to think about the various quotes you plan to use to substantiate each section. 📝

Having mapped out the overall trajectory of your essay, you can start to drill down into the detail. First, write the opening sentence for each of the paragraphs in the body section of your essay. Remember – each paragraph is like a mini-essay – the opening sentence should summarise what the paragraph will then go on to explain in more detail. 🖊️

Next, it's time to write the bulk of your words and flesh out your arguments. Follow the ‘point, evidence, explain’ method. The opening sentences – already written – should introduce your ‘points’, so now you need to ‘evidence’ them with corroborating research and ‘explain’ how the evidence you’ve presented proves the point you’re trying to make. ✍️

With a rough draft in front of you, you can take a moment to read what you have written so far. Are there any sections that require further substantiation? Have you managed to include the most relevant material you originally highlighted in your background reading? Now is the time to make sure you have evidenced all your opinions and claims with the strongest quotes, citations and material. 📗

This is your final chance to re-read your essay and go over it with a fine-toothed comb before pressing ‘submit’. We highly recommend leaving a day or two between finishing your essay and the final proofread if possible – you’ll be amazed at the difference this makes, allowing you to return with a fresh pair of eyes and a more discerning judgment. 🤓

If you are looking for advice and support with your own essay-writing adventures, why not t ry a free trial lesson with GoStudent? Our tutors are experts at boosting academic success and having fun along the way. Get in touch and see how it can work for you today. 🎒

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Akshat Biyani

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

The 12 Best GCSE Revision Apps to Supercharge Your Revision

More great reads:.

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

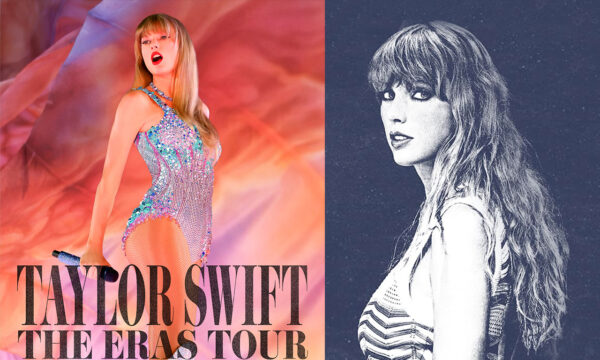

Ultimate Guide to Writing Your College Essay

Tips for writing an effective college essay.

College admissions essays are an important part of your college application and gives you the chance to show colleges and universities your character and experiences. This guide will give you tips to write an effective college essay.

Want free help with your college essay?

UPchieve connects you with knowledgeable and friendly college advisors—online, 24/7, and completely free. Get 1:1 help brainstorming topics, outlining your essay, revising a draft, or editing grammar.

Writing a strong college admissions essay

Learn about the elements of a solid admissions essay.

Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

Learn some of the most common mistakes made on college essays

Brainstorming tips for your college essay

Stuck on what to write your college essay about? Here are some exercises to help you get started.

How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

Learn how formal your college essay should be and get tips on how to bring out your natural voice.

Taking your college essay to the next level

Hear an admissions expert discuss the appropriate level of depth necessary in your college essay.

Student Stories

Student Story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

Get the perspective of a current college student on how he approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about personal identity

Get the perspective of a current college student on how she approached the admissions essay.

Student Story: Admissions essay about community impact

Student story: admissions essay about a past mistake, how to write a college application essay, tips for writing an effective application essay, sample college essay 1 with feedback, sample college essay 2 with feedback.

This content is licensed by Khan Academy and is available for free at www.khanacademy.org.

Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

Asking analytical questions, introductions, what do introductions across the disciplines have in common, anatomy of a body paragraph, transitions, tips for organizing your essay, counterargument, conclusions.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Essay Writing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Modes of Discourse—Exposition, Description, Narration, Argumentation (EDNA)—are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these approaches and students’ need to understand and produce them.

This resource begins with a general description of essay writing and moves to a discussion of common essay genres students may encounter across the curriculum. The four genres of essays (description, narration, exposition, and argumentation) are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres, also known as the modes of discourse, have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these genres and students’ need to understand and produce these types of essays. We hope these resources will help.

The essay is a commonly assigned form of writing that every student will encounter while in academia. Therefore, it is wise for the student to become capable and comfortable with this type of writing early on in her training.

Essays can be a rewarding and challenging type of writing and are often assigned either to be done in class, which requires previous planning and practice (and a bit of creativity) on the part of the student, or as homework, which likewise demands a certain amount of preparation. Many poorly crafted essays have been produced on account of a lack of preparation and confidence. However, students can avoid the discomfort often associated with essay writing by understanding some common genres.

Before delving into its various genres, let’s begin with a basic definition of the essay.

What is an essay?

Though the word essay has come to be understood as a type of writing in Modern English, its origins provide us with some useful insights. The word comes into the English language through the French influence on Middle English; tracing it back further, we find that the French form of the word comes from the Latin verb exigere , which means "to examine, test, or (literally) to drive out." Through the excavation of this ancient word, we are able to unearth the essence of the academic essay: to encourage students to test or examine their ideas concerning a particular topic.

Essays are shorter pieces of writing that often require the student to hone a number of skills such as close reading, analysis, comparison and contrast, persuasion, conciseness, clarity, and exposition. As is evidenced by this list of attributes, there is much to be gained by the student who strives to succeed at essay writing.

The purpose of an essay is to encourage students to develop ideas and concepts in their writing with the direction of little more than their own thoughts (it may be helpful to view the essay as the converse of a research paper). Therefore, essays are (by nature) concise and require clarity in purpose and direction. This means that there is no room for the student’s thoughts to wander or stray from his or her purpose; the writing must be deliberate and interesting.

This handout should help students become familiar and comfortable with the process of essay composition through the introduction of some common essay genres.

This handout includes a brief introduction to the following genres of essay writing:

- Expository essays

- Descriptive essays

- Narrative essays

- Argumentative (Persuasive) essays

H 1 . Introduction

This handbook is a brief yet comprehensive reference for you to consult as you write papers and other assignments for a college course. You can refer to it as you draft paragraphs and polish sentences for clarity, conciseness, and point of view. You can read it to learn how to identify and revise common sentence errors and confused words. You can use it to help you edit your writing and fine-tune your use of verbs, pronouns, punctuation, and mechanics. And you can have it open as you integrate and cite quotations as well as other source material in your papers in MLA or APA style.

Designed as a reference tool, the handbook is organized to help you get answers to your questions. You do not need to read the entire handbook to get helpful information from it. For example, if your instructor has noted that you need to work on comma splices, you can refer to Sentence Errors , before you turn in a final draft of your writing. If you know you frequently misuse commas, refer to Punctuation , and check your sentences against the advice there. And if you, like many writers, can’t remember which punctuation marks go inside and outside quotation marks, refer to Quotations . Becoming familiar with the handbook and the various topics will allow you to use it efficiently.

H 2 . Paragraphs and Transitions

Paragraphs help readers make their way through prose writing by presenting it in manageable chunks. Transitions link sentences and paragraphs so that readers can clearly understand how the points you are making relate to one another. (See Editing Focus: Paragraph and Transitions for a related discussion of paragraphs and transitions. See Evaluation: Transitions for a related discussion of transitions in multimodal compositions.)

Effective Paragraphs

Paragraphs are guides for readers. Each new paragraph signals either a new idea, further development of an existing idea, or a new direction. An effective paragraph has a main point supported by evidence, is organized in a sensible way, and is neither too short nor too long. When a paragraph is too short, it often lacks enough evidence and examples to back up your claims. When a paragraph is too long, readers can lose the point you are making.

Developing a Main Point

A paragraph is easier to write and easier to read when it centers on a main point. The main point of the paragraph is usually expressed in a topic sentence . The topic sentence frequently comes at the start of the paragraph, but not always. No matter the position, however, the other sentences in the paragraph support the main point.

Supporting Evidence and Analysis

All the sentences that develop the paragraph should support or expand on the main point given in the topic sentence. Depending on the type of writing you are doing, support may include evidence from sources—such as facts, statistics, and expert opinions—as well as examples from your own experience. Paragraphs also may include an analysis of your evidence written in your own words. The analysis explains the significance of the evidence to the reader and reinforces the main point of the paragraph.

In the following example, the topic sentence is underlined. The supporting evidence discussed through cause-and-effect reasoning comes in the next three sentences. The paragraph concludes with two sentences of analysis in the writer’s own words.

underline Millions of retired Americans rely on Social Security benefits to make ends meet after they turn 65. end underline According to the Social Security Administration, about 46 million retired workers receive benefits, a number that reflects about 90 percent of retired people. Although experts disagree on the exact numbers, somewhere between 12 percent and 40 percent of retirees count on social security for all of their income, making these benefits especially important (Konish). These benefits become more important as people age. According to Eisenberg, people who reach the age of 85 become more financially vulnerable because their health care and long-term care costs increase at the same time their savings have been drawn down. It should therefore come as no surprise that people worry about changes to the program. Social Security keeps millions of retired Americans out of poverty.

Opening Paragraphs

Readers pay attention to the opening of a piece of writing, so make it work for you. After starting with a descriptive title, write an opening paragraph that grabs readers’ attention and alerts them to what’s coming. A strong opening paragraph provides the first clues about your subject and your stance. In academic writing, whether argumentative, interpretative, or informative, the introduction often ends with a clear thesis statement , a declarative sentence that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic the rest of the paper will support.

Depending on the type of writing you’re doing, you can open in a variety of ways.

- Open with a conflict or an action. If you’re writing about conflict, a good opening may be to spell out what the conflict is. This way of opening captures attention by creating a kind of suspense: Will the conflict be resolved? How will it be resolved?

- Open with a specific detail, statistic, or quotation. Specific information shows that you know a lot about your subject and piques readers’ curiosity. The more dramatic your information, the more it will draw in readers, as long as what you provide is credible.

- Open with an anecdote. Readers enjoy stories. Particularly for reflective or personal narrative writing, beginning with a story sets the scene and draws in readers. You may also begin the anecdote with dialogue or reflection.

The following introduction opens with an anecdote and ends with the thesis statement, which is underlined.

Betty stood outside the salon, wondering how to get in. It was June of 2020, and the door was locked. A sign posted on the door provided a phone number for her to call to be let in, but at 81, Betty had lived her life without a cell phone. Betty’s day-to-day life had been hard during the pandemic, but she had planned for this haircut and was looking forward to it: she had a mask on and hand sanitizer in her car. Now she couldn’t get in the door, and she was discouraged. In that moment, Betty realized how much Americans’ dependence on cell phones had grown in the months she and millions of others had been forced to stay at home. underline Betty and thousands of other senior citizens who could not afford cell phones or did not have the technological skills and support they needed were being left behind in a society that was increasingly reliant on technology end underline .

Closing Paragraphs

The conclusion is your final chance to make the point of your writing stick in readers’ minds by reinforcing what they have read. Depending on the purpose for your writing and your audience, you can summarize your main points and restate your thesis, draw a logical conclusion, speculate about the issues you have raised, or recommend a course of action, as shown in the following conclusion:

Although many senior citizens purchased and learned new technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant number of older people like Betty were unable to buy and/or learn the technology they needed to keep them connected to the people and services they needed. As society becomes increasingly dependent on technology, social service agencies, religious institutions, medical providers, senior centers, and other organizations that serve the elderly need to be equipped to help them access and become proficient in the technologies essential to their daily lives.

Transitions

Transitional words and phrases show the connections or relationships between sentences and paragraphs and help your writing flow smoothly from one idea to the next.

A paragraph flows when ideas are organized logically and sentences move smoothly from one to the next. Transitional words and phrases help your writing flow by signaling to readers what’s coming in the next sentence. In the paragraph below, the topic sentence and transitional words and phrases are underlined.

underline Some companies court the public by mentioning environmental problems and pointing out that they do not contribute to these problems. end underline underline For example end underline , the natural gas industry often presents natural gas as a good alternative to coal. underline However end underline , according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, the drilling and extraction of natural gas from wells and transporting it through pipelines leaks methane, a major cause of global warming (“Environmental Impacts”). underline Yet end underline leaks are rarely mentioned by the industry. By taking credit for problems they don’t cause and being silent on the ones they do, companies present a favorable environmental image that often obscures the truth.

Transitional Words and Phrases

Following are some transitional words and phrases and their functions in paragraphs. Use this list when drafting or revising to help guide readers through your writing. (See Editing Focus: Paragraphs and Transitions for another discussion on transitions.)

H 3 . Clear and Effective Sentences

This section will help you write strong sentences that convey your meaning clearly and concisely. See Editing Focus: Sentence Structure for a related discussion and practice on effective sentences.

The most emphatic place in a sentence is the end. To achieve the strongest emphasis, end with the idea you want readers to remember. Place introductory, less important, or contextual information earlier in the sentence. Consider the differences in these two sentences.

Less Emphatic Angel underline needs to start now end underline if he wants to have an impact on his sister’s life. More Emphatic If Angel wants to have an impact on his sister’s life, he underline needs to start now end underline .

Concrete Nouns

General nouns name broad classes or categories of things ( man, dog, city ); concrete nouns refer to particular things ( Michael, collie, Chicago ). Concrete nouns provide a more vivid and lively reading experience because they create stronger images that activate readers’ senses. The examples below show how concrete nouns, combined with specific details, can make writing more engaging.

All General Nouns Approaching the library, I see underline people end underline and underline dogs end underline milling about underline outside end underline , but no subjects to write about. I’m tired from my underline walk end underline and go inside. Revised with Concrete Nouns Approaching underline Brandon Library end underline , I see underline skateboarders end underline and underline bikers end underline weaving through underline students end underline who talk in underline clusters end underline on the underline library steps end underline . A friendly underline collie end underline waits for its owner to return. Subjects to write about? Nothing strikes me as especially interesting. Besides, my heart is still pounding from the walk up the hill. I wipe my sweaty underline forehead end underline and go inside.

Active Voice

Active voice refers to the way a writer uses verbs in a sentence. Verbs have two “voices”: active and passive. In the active voice , the subject of the sentence acts—the subject performs the action of the verb. In the passive voice , the subject receives the action, and the object actually becomes the subject. Although some passive sentences are necessary and clear, a paper full of passive-voice constructions lacks vitality and becomes wordy.

Active-voice verbs make something happen. By using active verbs wherever possible, you will create stronger, clearer, and more concise sentences.

Passive Voice On the post-training survey, the anti-harassment tutorial underline was rated end underline highly informative underline by end underline employees. Revised in Active Voice On the post-training survey, underline employees end underline underline rated end underline the anti-harassment tutorial highly informative.

Conciseness

Concise writing considers the importance of every word. Editing sentences for emphasis, concrete nouns, and active voice will help you write clearly and precisely, as will the following strategies. To be concise, eliminate wasted words and filler— not ideas, information, description, or details that will interest readers or help them follow your thoughts. (For more on conciseness, see Editing Focus: Sentence Structure .)

Use Action Verbs

Using action verbs is one of the most direct ways to cut unneeded words. Whenever you find a phrase like the ones below, consider substituting an action verb.

Cut Unnecessary Words and Phrases

Eliminate words and phrases that do not add meaning. Consider the following sentences, which say essentially the same thing.

Wordy In almost every situation that I can think of, with few exceptions, it will make good sense for you to look for as many places as possible to cut out needless, redundant, and repetitive words and phrases from the papers, reports, paragraphs, and sentences you write for college assignments. (49 words) Concise Whenever possible, cut needless words and phrases from your college writing. (11 words)

The wordy sentence is full of early-draft language in three chunks. The first chunk comes at the beginning of the sentence. Notice how In almost every situation that I can think of, with few exceptions, it will make good sense for you to look for as many places as possible is reduced to Whenever possible in the concise sentence.

The second chunk of the wordy sentence is needless, redundant, and repetitive. The concise version reduces those four words to needless because the words have the same meaning. The third chunk of the wordy sentence comes at the end. Notice how papers, reports, paragraphs, and sentences you write for college assignments is reduced to your college writing. The meaning, although expanded to all writing, remains the same.

The following phrases are common fillers that add nothing to meaning. They should be avoided.

- a person by the name of

- for all intents and purposes

- in a manner of speaking

- more or less

Some common filler phrases have single-word alternatives, which are preferable.

Avoid there is/there are and it is

Starting a sentence with there is, there are, or it is can be useful to draw attention to a change in direction. However, starting a sentence with one of these phrases often forces you into a wordy construction. Wordiness means the presence of verbal filler; it does not mean the number of words, the amount of description, or the length of a composition. (For more on these constructions, see Editing Focus: Sentence Structure .)