- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

- Strengthening education systems and innovation

Getting all children in school and learning takes strong, innovative education systems.

Education systems are complex. Getting all children in school and learning requires alignment across families, educators and decision makers. It requires shared goals, and national policies that put learning at the centre. It also requires data collection and regular monitoring to help policymakers identify what’s working, who’s benefiting, and who’s being left behind.

Strong education systems are inclusive and gender-equitable. They support early learning and multi-lingual education, and foster innovations to extend education opportunities to the hardest-to-reach children and adolescents.

Innovation in education

Innovation in education is about more than new technology. It’s about solving a real problem in a fresh, simple way to promote equity and improve learning.

Innovation in education comes in many forms. Programmes, services, processes, products and partnerships can all enhance education outcomes in innovative ways – like customized games on solar-powered tablets that deliver math lessons to children in remote areas of Sudan. Or digital learning platforms that teach refugees and other marginalized children the language of instruction in Greece, Lebanon and Mauritania.

Innovation in education means solving a real problem in a new, simple way to promote equitable learning.

Innovation in education matches the scale of the solution to the scale of the challenge. It draws on the creativity and experience of communities – like a programme in Ghana that empowers local mothers and grandmothers to facilitate early childhood education – to ensure decisions are made by those most affected by their outcomes.

Many innovators are already at work in classrooms and communities. UNICEF collaborates with partners to identify, incubate and scale promising innovations that help fulfil every child’s right to learn.

UNICEF’s work to strengthen education systems

UNICEF works with communities, schools and Governments to build strong, innovative education systems that enhance learning for all children.

We support data collection and analysis to help Governments assess progress across a range of outcomes and strengthen national Education Management Information Systems. We also develop comprehensive guidelines for education sector analysis that are used in countries around the world to drive equity-focused plans and policies.

Our efforts promote transparency , shedding light on education systems so that students, parents and communities gain the information they need to engage decision makers at all levels and hold them to account.

More from UNICEF

Turning trash into building blocks for children's futures

Côte d'Ivoire’s innovative project to transform plastic waste into construction materials for new schools

Using data to improve education in Angola

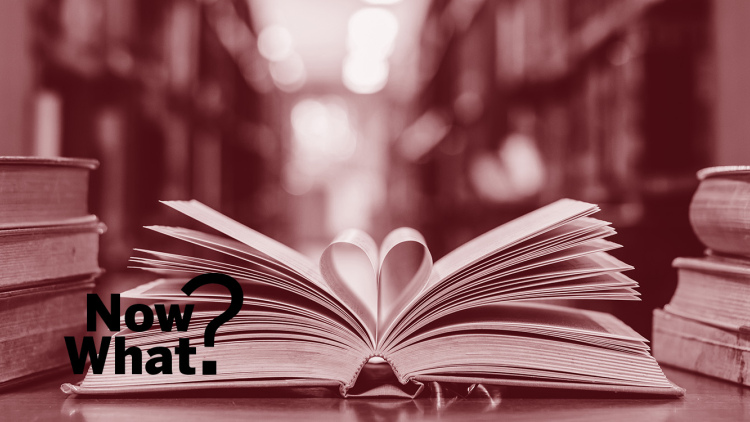

A digital application, developed with support from UNICEF, aims to bring back children outside the education system

How popularity and fashion promote environmental solutions

High school students in North Macedonia team up to clean up their school.

Children call for access to quality climate education

On Earth Day, UNICEF urges governments to empower every child with learning opportunities to be a champion for the planet

Education Sector Analysis Guidelines: Volume 1 ( English , French , Spanish , Portuguese and Russian )

These guidelines support ministries of education and their partners in undergoing sector analysis and developing education sector plans.

Education Sector Analysis Guidelines: Volume 2 ( English , French , Spanish , Portuguese and Russian )

The investment case for education and equity.

This report analyses the learning crisis and its determinants and makes the case for an increase in funding for education and for more equitable and efficient spending.

Education Data Solutions Roundtable

Explore the Global Partnership for Education’s roundtable to leverage partners’ expertise and improve the availability and use of accurate, timely education data.

Collecting Data on Foundational Learning Skills and Parental Involvement in Education

This methodological paper measures foundational learning skills and parental involvement in education through household surveys.

The Impact of Innovation in Education

Industry Advice Education

Organizations across industries today have come to rely on innovation to remain relevant and effective in our constantly evolving society. Whether by updating their products, processes, or business models or developing new ones from scratch, innovation allows companies to stay abreast of changing consumer needs and expectations, and to remain competitive against similar companies in their space.

The innovation process is responsible for many of the most popular products and services we know today, including app-ordered food delivery services , video streaming platforms , two-day shipping features from Amazon , and so much more. However, Karen Reiss Medwed , PhD—associate teaching professor and the assistant dean of networks, digital engagement, and partnerships in Northeastern’s Graduate School of Education —explains that innovation should be associated with more than just these large-scale projects. The education sector, for example, offers countless opportunities for change and evolvement that have the potential to impact students, parents, and educators for years to come.

Below, we explore the powerful significance of this innovative mindset among educators and offer tips for applying innovation in your educational institution today.

Download Our Free Guide to Earning Your EdD

Learn how an EdD can give you the skills to enact organizational change in any industry.

DOWNLOAD NOW

What is Innovation in Education?

In general, innovation is based in the creation or redesign of products, processes, or business models for the benefit of an organization. Innovation in education is similarly focused on making positive changes, but in this case, these changes will directly benefit a classroom, school, district, university, or even an organization’s training and learning practices.

Educators and administrators take a variety of both large- and small-scale approaches to this process. For instance, innovation in education might include:

- An educator recognizing a need for ideas to be better shared among other teachers in their district and developing processes that more easily facilitate that.

- A professor identifying a gap in understanding among the students in their classroom and brainstorming new, creative ways to approach that topic.

- An administrator identifying the need for better communication between teachers and parents, and working to create an online system that allows for more transparency into their child’s progress.

While each of these forms of innovation is very different, each involves an educator following the innovation process in an effort to improve the ways in which the educational system functions.

Why is Innovation in Education Important?

Innovation is a vital component of progress across industries, and education is no different. “Schools don’t exist in a silo, teachers don’t exist in a silo, [and] businesses don’t exist in a different realm,” Reiss Medwed says. “We’re all at a table together, trying to solve the world’s problems.”

Innovation in education is especially significant, considering the young minds molded by the education system today will be those leading the charge for innovation tomorrow. And if the rapidly changing needs of the current workforce are any indication of what’s to come for future generations, this investment will be necessary in order to continue making progress at the speed and quality that we are today.

“Industry is moving at a rapid pace,” Reiss Medwed explains. “We’re living in the space of digital transformation. There are needs in business and in [other] industries that ten years ago, we never anticipated for the workforce, and as that rate of change takes off…we must [work to] catch up.”

To catch up, educators must update the outdated processes and approaches defining schools and universities across the country, and introduce practices that better prepare students to function in the future. This includes, most prominently, changes in curricula and hands-on exposure to the expansive digital tools being used across industries today.

How to Innovate in the Education Sector

Many professionals have ideas about how they might improve the educational system, yet very few possess the tools and support needed to turn their passion from an abstract idea into a reality.

Reiss Medwed believes that innovation in education includes three key steps:

- Examine your current situation. This should include an examination of your experience followed by a mental exploration of how that experience could be improved upon. Ask yourself three questions to get this process going, including, “What is the problem?” “How can I address this problem to make it better?” and “What tools do I have at my disposal to assist in this process?”

- Make Small-Scale Changes. Once you’ve explored the above questions and the answers are formalized, you should try to make that change on a small-scale within your own world.

- Broaden Your Approach & Accept to Feedback. Analyze the outcomes of that experiment and identify what further support might be needed to either hone the idea or restructure it all together.

This final step is perhaps the most important and will require the most time and effort. Within it, you will likely lean on existing data about your subject, which might include examining past artifacts, doing research, speaking with those who have tried to innovate in this space before you, and, perhaps most importantly, identifying your stakeholders.

“One of the big [components] of innovation in education is making sure students and parents are at the table,” Reiss Medwed says. “There’s hierarchy [in place] to keep those stakeholders out, but how can you innovate without the people who are your learners sitting with you in the process of design?”

To properly innovate with all the appropriate voices being heard, Reiss Medwed suggests “rolling out a broader-scale experience with all of the stakeholders engaged,” followed by a feedback loop. She similarly stresses the importance of self-reflection, including acknowledging when you need to “re-tool,” pivot in your process, cancel it altogether, or bring your idea to scale.

“We always want to be able to try something new [as educators],” Reiss Medwed stresses, “but we also have to be willing to fail at it, let it go, and move onto the next thing. Because innovation without the capacity of sustainability is just another experiment.”

Pursuing an EdD as an Aspiring Innovator

Innovators who have the experience and skills necessary to self-regulate this process will likely be able to make an impact in their industry. However, not all educators have attained this advanced ability by the time they are ready to start effecting change. For these individuals, obtaining an advanced degree such as a Doctor of Education (EdD) will provide the necessary training and guidance needed to innovate in this complex sector.

Learn More: EdD vs. Phd in Education

Many students in EdD programs work full-time as education professionals, bringing with them problems that they’re excited to solve and ideas about how to begin that process. In these scenarios, faculty in a program like Northeastern’s EdD provide a set of courses and feedback processes through which these ideas can develop.

“In the [Northeastern’s] Graduate School of Education, you’ll see both explicit courses on innovation and experiential learning, but also courses such as curriculum engaging with design thinking methodology,” Reiss Medwed says. “This approach to [the] integration of these competencies across the curriculum is part of what I think helps us advance students who are then prepared in their practice to apply this to their own work and see immediate results.”

Northeastern’s EdD program strategically incorporates these two vital aspects of training through an “experiential lens.” As working professionals already functioning in the education sector, students in this program can take what they’re learning in the classroom and immediately apply it hands-on to real-world scenarios. This is an incredibly beneficial approach, as the industry-leading professors in this program can offer useful feedback and insight to students as they work, strategically guiding them toward a successful innovation experience.

Reiss Medwed recalls one specific example of a student who came through a program within Northeastern’s Graduate School of Education and left with a full innovation plan in place. The student’s idea was to “develop a website that could connect educators to one another around the subject area she was teaching,” Reiss Medwed says.

During this student’s time at Northeastern, the faculty within the Graduate School of Education connected the aspiring innovator with peers who asked her targeted questions about her idea and faculty who gave her feedback about legal issues, budget considerations, and other advanced insights. She was then able to use “design thinking to prototype an idea and turn it into a plan that she could actually take back with her into her work,” Reiss Medwed says. Today, this student has a “fully launched community of practice” that she was able to create through her work at Northeastern.

“I think that everyone who [applies to] a graduate school of education is looking to make a difference in the world,” Reiss Medwed says. “But…if you’re coming to Northeastern as a student in the Graduate School of Education , you’re seeking out the tools and the support to make that change more explicit.”

Learn more about how a Doctor of Education from Northeastern can assist in your path toward educational innovation today.

Subscribe below to receive future content from the Graduate Programs Blog.

About shayna joubert, related articles.

What is Learning Analytics & How Can it Be Used?

Reasons To Enroll in a Doctor of Education Program

Why I Chose to Pursue Learning Analytics

Did you know.

The median annual salary for professional degree holders is $97,000. (BLS, 2020)

Doctor of Education

The degree that connects advanced research to real-world problem solving.

Most Popular:

Tips for taking online classes: 8 strategies for success, public health careers: what can you do with an mph, 7 international business careers that are in high demand, edd vs. phd in education: what’s the difference, 7 must-have skills for data analysts, in-demand biotechnology careers shaping our future, the benefits of online learning: 8 advantages of online degrees, how to write a statement of purpose for graduate school, the best of our graduate blog—right to your inbox.

Stay up to date on our latest posts and university events. Plus receive relevant career tips and grad school advice.

By providing us with your email, you agree to the terms of our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Keep Reading:

The 8 Highest-Paying Master’s Degrees in 2024

Graduate School Application Tips & Advice

How To Get a Job in Emergency Management

Join Us at Northeastern’s Virtual Graduate Open House | March 5–7, 2024

5 Ways Educators Can Start Innovating

- Posted August 20, 2021

- By Jill Anderson

- Organizational Change

Innovation can be a powerful tool when it is built on the opportunities and challenges educators see on a daily basis. However, educators don’t often believe they have time to innovate and the idea of innovation can be daunting. What’s more, educators aren’t always given the necessary trust or ability to act independently to come up with new ideas for schools and see them through.

“The concept that you have to do something that is world changing or changes everything can be a barrier to teachers and school leaders,” says Andrea Sachdeva , senior project manager at Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) and an HGSE graduate. Instead, as she points out in Inquiry-Driven Innovation , the new book she cowrote with HGSE lecturer and Project Zero principal investigator Elizabeth Dawes Duraisingh , innovation can be something small.

Dedicating time to innovation, they say, can lead to positive school-based change and even reinvigorate practice. They saw this story play out in research they conducted for four years with Project Zero colleagues. “Educators found it energizing to create the time and work together with people they normally wouldn’t work with. It renewed their sense of purpose,” Dawes Duraisingh says. “It goes beyond, ‘Here’s my list of tasks,’ to thinking about what are we striving for and how can I build that into my work as a teacher and revitalize what I’m doing?”

Here are five principles Sachdeva and Dawes Duraisingh recommend for educators who want to make change in their schools:

- Be purposeful and intentional. Think about why you are pursuing innovation in your school or practice. Innovation can be a buzzword for many people, conjuring up major technological advances. It doesn’t have to be big, but it does need to be relevant and responsive to your local context.

- Include diverse perspectives. Create diverse study groups of educators and listen closely to everyone involved. Put together colleagues who don’t usually have the chance to work together — whether that’s educators from different subject areas or with different levels of authority or types of life experience — and be sure to pay attention to voices that are often left out of conversations about school change, such as students and their parents. By working to include diverse points of view and experiences, you’ll have different conversations than usual and are more likely to get beyond “to do” lists. Your innovation is also more likely to gain traction within your school.

- Push for local ownership. Make sure innovation is starting from needs and wishes in your local community, rather than defaulting to current trends in education or recommendations for change that come from outside. Help everyone involved to feel ownership, pride, and investment in the changes, for example, by giving your innovation a name that connects it to your school.

- Get your structures and support in place first. Educators can’t just innovate right away without the proper supports and structure in place to be successful. This means establishing working teams that enjoy support throughout the school including with leaders, and who are given permission to try new things out.

- Keep it going. Consider how to sustain the initiative even after the initial enthusiasm. Create supportive structures to help people keep developing and refining the innovation over time. Some of the professional development tools that can help with this process can take as little as 10 minutes a day in practice.

Additional resources:

- Register for a free online workshop for educators related to these ideas.

- Download free resources from the book.

- Read an excerpt from the book.

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Treat Students Like Human Beings

Leaving No Child Behind

Brennan, Bridwell-Mitchell Announced as Named Chairs

Education innovations are taking root around the world. What do they have in common?

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, rebecca winthrop and rebecca winthrop director - center for universal education , senior fellow - global economy and development @rebeccawinthrop adam barton adam barton cambridge international scholar, faculty of education - university of cambridge, former senior research analyst - center for universal education.

May 17, 2018

In the lead up to the Center for Universal Education’s annual research and policy symposium “ Citizens of the Future: Innovations to Leapfrog Global Education ” May 21, 2018 (livestream available), authors from the education innovations community have contributed their unique insights to this blog series on the topic. Access all of our content on innovations here .

When you think of education systems, what sorts of words come to mind? If you are anything like the many education practitioners, policymakers, and leaders who we meet every year throughout the world, you might be thinking of words and phrases like “political” or “resistant to change.” But we would wager that one word almost certainly did not cross your mind: “innovative.”

If a common educational narrative exists across the globe, it seems to be one of stagnation. In academic journals and on TV, in boardrooms and in statehouses, concerned citizens consistently and urgently call for “reinventing” and “reimagining” education. Education systems, they argue, are both outmoded and slow to change.

However, findings in our forthcoming book, Leapfrogging Inequality : Remaking Education to Help Young People Thrive , call this narrative into question. We spent the last three years studying education innovations, which we define as any tools, policies, programs, or ideas that break from previous practice. To be innovative, these diverse practices need not be new to the world, though they are often new in a particular context.

With this broad definition in mind, we found a flourishing group of teachers, school leaders, students, companies, community organizations, non-profits, parents, researchers, administrators, ministers, and politicians who are actively innovating in education. We call these actors engaged in supporting innovative education practices worldwide the “education innovations community.” Compiling a global catalog of almost 3,000 education innovations , the largest such collection to date, we discovered new practices in some 166 countries. These include some from the most remote and resource-strapped parts of the globe, as well as the wealthy urban centers of industrialized nations. Innovation in education, it seems, is alive and well.

Related Books

Rebecca Winthrop Adam Barton, Eileen McGivney

June 5, 2018

However, it appears that many of these actors do not yet feel part of a global education innovations community. They often innovate on the margins of formal education systems, in isolation and with little connection to or support from peers. Visibility is an additional challenge for innovators, as many struggle to showcase their work for actors who could make systems-wide changes.

This is why the organizations that we call “Innovation Spotters” play such an important role in creating and sustaining an education innovations community. We define Innovation Spotters as those groups that are searching the globe to find, highlight, and sometimes support education innovations. These Spotters vary widely in mission and mandate: some seek innovation across the globe, while others look only to the developing world; some prioritize specific types of innovation implementers, such as government actors, and still others consider only innovations with particular pedagogical features, such as those that teach 21st century skills, or those that use technology.

In our efforts to map the state of the global education innovations community, we studied the work of 16 Innovation Spotters:

- Results for Development’s Center for Education Innovations

- OECD’s Innovative Learning Environments project

- Graduate XXI

- UNICEF Innovation Fund

- Harvard’s Global Education Innovations Initiative

- Teach for All’s Alumni Incubator

- the mEducation Alliance

- All Children Reading: Grand Challenge for Development

- Development Innovation Ventures

- Humanitarian Education Accelerator

- Global Innovation Fund.

We relied heavily on lists and databases of innovations compiled by each of these Spotters to develop our global catalog of innovations. A relatively coherent picture of global spotting efforts emerged from our analysis of these Spotters’ activities. We found that, collectively, the Spotter community is heavily focused on new practices emerging from non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Indeed, NGOs implement over 60 percent of innovations in our global catalog. In contrast, for-profit organizations implement only 26 percent of cataloged innovations, and government actors fall farthest behind, leading only 12 percent. We also found that Spotters focused heavily on innovations serving the most marginalized children, such as low-income learners, out-of-school children, and orphans. Fifty-seven percent of all innovations serve such communities.

These Spotters seem keen to highlight innovations that are relatively young, with half of all cataloged interventions created or founded in the past 10 years, and one-quarter in or after 2012. In terms of pedagogy, we are pleased to see that nearly half of the spotted innovations aim to teach both academic competencies and 21st century skills at the same time. In doing so, nearly 70 percent make use of the playful, hands-on learning approaches needed to effectively develop a full range of learners’ abilities.

Still, we note that the Innovation Spotters have carved out quite specific niches for themselves. Indeed, only 10 percent of cataloged innovations appeared on the lists of more than one Spotter. This diversity of spotting practice aids in the effort to build an enduring education innovations community—one that can share learnings, inspire ideation, and support implementation within and between contexts around the world. While there are plenty of discussions to be had on the prospect of building this community and strengthening the networks within it, perhaps the most pressing question is around next steps: how can we translate this spotting effort into educational transformation on the ground?

This is a question we will explore at our May 21 symposium, Citizens of the future: Innovations to leapfrog global education (webcast available) , co-hosted with the Inter-American Development Bank. Grappling with the role of teaching and learning in educational transformation, we hope to map what comes next for the global education innovations community—and, in so doing, chart an accelerated path toward equitable and quality learning for all.

Related Content

Brookings Institution, Washington DC

9:00 am - 6:00 pm EDT

Alejandro Paniagua

February 8, 2018

Anna Penido

March 20, 2018

Education Technology Global Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Ariell Bertrand, Melissa Arnold Lyon, Rebecca Jacobsen

April 18, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon

April 15, 2024

Phillip Levine

April 12, 2024

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, innovation in education: what does it mean, and what does it look like.

Innovation. It’s such an overused term, isn’t it? Everyone these days is striving to be innovative, is promising innovation, is encouraging others to innovate. But if you think about it, it’s overused for a reason. It’s a single word that encapsulates everything that is exciting in any industry—a goal to shoot for because it means you’re different, your ideas are new, and your work is almost magical.

Our team uses the term a lot, and we say it proudly! Innovation in the education vertical is so very important. We want our students to love learning, we need them to! By being innovative, we can engage students in ways we never have before, and that’s pretty incredible.

We surveyed teachers and educators to respond to two questions: What does innovation in education mean to you? And, what’s the most innovative thing you have done—or have seen another teacher do—in the classroom? Some of our favorite responses are below. Read on and get inspired.

What does innovation in education mean to you?

“Innovation in education means doing what’s best for all students. Teachers, lessons, and curriculum have to be flexible. We have to get our students to think and ask questions. We need to pique their curiosity, and find ways to keep them interested. Innovation means change, so we have to learn that our students need more than the skills needed to pass the state assessments given every spring. We have to give them tools that will make them productive in their future careers.” – Kimberly

“Innovation, to me, means finding any way you can to reach all of your students. This means being willing and flexible to adjust what you teach and how you teach. We have to keep our students engaged and excited to learn. We have to create a safe place for them to make mistakes, take risks, and ask questions.” – Ashley

“Innovation in education is always seeking knowledge that will support new and unique ideas in instructional techniques that will reach the students in more effective and exciting ways.” – Mischelle

“Innovation in education is stepping outside of the box, challenging our methods and strategies in order to support the success of all students as well as ourselves. This transformation may be small or a complete overhaul, but it is done with purpose and supports the whole student.” – Whitney

“Innovation in education means allowing imagination to flourish and not be afraid to try new things. Sometimes these new things fail but it’s awesome when they are a success. Without the right attitude, innovation would just be a word and the art of education would miss out on some great accomplishments.” – Valerie

“Innovation means keeping yourself educated about new trends and technology in education. For example, I incorporated STEM bins into my classroom because their is a huge push for more STEM related activities in education. I think innovation is also being creative with the resources your given. Sometimes your building or district might not provide everything you need for a lesson so you need to be innovative and think on the fly of how you could make something work!” – Nadia

What’s the most innovative thing you have done—or have seen another teacher do—in the classroom?

“My team teacher and I used guest teacher certificates as part of our reward system. Kids had 10-15 minutes to teach the class anything they wanted. It was amazing to see them get up in front of their peers and share their passions!” – Marlene

“I set my math & science units for my third graders up like college classes. Students start with picking a particular major and at the end of the unit, we work on making connections on how each lesson relates to the real world and the job they each choose individually. My students absolutely love the opportunity to be treated like adults and explore future options.” – Jade

“We have at times had students begin creating graphic novels in order to have better recall regarding historical information!” – Misty

“My second graders grade their own tests using their tech devices. They get immediate feedback and take the time to understand the answers that are wrong.” – Jenifer

“The most innovative thing I’ve done in my classroom is using a TAP (Teacher Advancement Program) rubric in my whole lesson where there are 19 indicators to follow. Some of the indicators are standards and objectives, activities and materials, feedbacking, questioning, etc. These indicators are true testament that if this TAP rubric is done daily, I can move students daily. Move means students’ academic growth. There is nothing more rewarding for a teacher than to see his or her students academic grow, improve, or increase. That’s the beauty of the TAP rubric.” – Marlyn

What about you? Join us on Facebook.

You may also like to read

- Teacher Lesson Plans for Special Education Students

- 9 iPad Apps for the Special Education Classroom

- How to Bridge the Gap Between Technology and Special Education Students

- Three Education Technology Trends to Watch

- Should Technology Be Part of Early Childhood Education?

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Educational Technology , Giveaways , Social Media , STEAM

- Master's in PE, Sports & Athletics Administra...

- Certificates in Early Childhood Education

- STEAM Teaching Resources for Educators | Resi...

Education Innovation: What It Is and Why We Need More of It

- Share article

NOTE: This is a guest post from Jim Shelton, Assistant Deputy Secretary of the Office of Innovation and Improvement at the U.S. Department of Education.

Whether for reasons of economic growth, competitiveness, social justice or return on tax-payer investment, there is little rational argument over the need for significant improvement in U.S. educational outcomes. Further, it is irrefutable that the country has made limited improvement on most educational outcomes over the last several decades, especially when considered in the context of the increased investment over the same period. In fact, the total cost of producing each successful high school and college graduate has increased substantially over time instead of decreasing - creating what some argue is an inverted learning curve.

This analysis stands in stark contrast to the many anecdotes of teachers, schools and occasionally whole systems “beating the odds” by producing educational outcomes well beyond “reasonable” expectations. And, therein lies the challenge and the rationale for a very specific definition of educational innovation.

Education not only needs new ideas and inventions that shatter the performance expectations of today’s status quo; to make a meaningful impact, these new solutions must also “scale”, that is grow large enough, to serve millions of students and teachers or large portions of specific under-served populations. True educational innovations are those products, processes, strategies and approaches that improve significantly upon the status quo and reach scale.

Systems and programs at the local, state and national level, in their quest to improve, should be in the business of identifying and scaling what works. Yet, we traditionally have lacked the discipline, infrastructure, and incentives to systematically identify breakthroughs, vet them and support their broad adoption - a process referred to as field scans. Programs like the Department of Education’s Investing in Innovation Fund (i3) are designed as field scans; but i3 is tiny in comparison to both the need and the opportunity. To achieve our objectives, larger funding streams will need to drive the identification, evaluation, and adoption of effective educational innovations.

Field scans are only one of three connected pathways to education innovation, and they build on the most recognized pathway - basic and applied research. The time to produce usable tools and resources from this pathway can be long - just as in medicine where development and approval of new drugs and devices can take 12-15 years - but, with more and better leveraged resources, more focus, and more discipline, this pathway can accelerate our understanding of teaching and learning and production of performance enhancing practices and tools.

The third pathway focuses specifically on accelerating transformational breakthroughs, which require a different approach - directed development. Directed development processes identify cutting edge research and technology (technology generically, not specifically referring to software or hardware) and use a uniquely focused approach to accelerate the pace at which specific game changing innovations reach learners and teachers. Directed development within the federal government is most associated with DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), which used this unique and aggressive model of R&D to produce technologies that underlie the Internet, GPS, and the unmanned aircraft (drone). Education presents numerous opportunities for such work. For example: (1) providing teachers with tools that identify each student’s needs and interests and match them to the optimal instructional resources or (2) cost-effectively achieving the 2 standard deviations of improvement that one-to-one human tutors generate. In 2010, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology recommended the creation of an ARPA for Education to pursue directed development in these and other areas of critical need and opportunity.

Each of these pathways -the field scan, basic and applied research and directed development - will be essential to improving and ultimately transforming learning from cradle through career. If done well, we will redefine “the possible” and reclaim American educational leadership while addressing inequity at home and abroad. At that point, we may be able to rely on a simpler definition of innovation:

An innovation is one of those things that society looks at and says, if we make this part of the way we live and work, it will change the way we live and work." -Dean Kamen

-Jim Shelton

Note: The Office of Innovation and Improvement at the U.S. Department of Education administers more than 25 discretionary grant programs, including the Investing in Innovation Program, Charter Schools Program, and Technology in Education.

The opinions expressed in Sputnik are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Innovation in education: what works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it?

Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning

ISSN : 2397-7604

Article publication date: 3 April 2017

The purpose of this paper is to present an analytical review of the educational innovation field in the USA. It outlines classification of innovations, discusses the hurdles to innovation, and offers ways to increase the scale and rate of innovation-based transformations in the education system.

Design/methodology/approach

The paper is based on a literature survey and author research.

US education badly needs effective innovations of scale that can help produce the needed high-quality learning outcomes across the system. The primary focus of educational innovations should be on teaching and learning theory and practice, as well as on the learner, parents, community, society, and its culture. Technology applications need a solid theoretical foundation based on purposeful, systemic research, and a sound pedagogy. One of the critical areas of research and innovation can be cost and time efficiency of the learning.

Practical implications

Several practical recommendations stem out of this paper: how to create a base for large-scale innovations and their implementation; how to increase effectiveness of technology innovations in education, particularly online learning; how to raise time and cost efficiency of education.

Social implications

Innovations in education are regarded, along with the education system, within the context of a societal supersystem demonstrating their interrelations and interdependencies at all levels. Raising the quality and scale of innovations in education will positively affect education itself and benefit the whole society.

Originality/value

Originality is in the systemic approach to education and educational innovations, in offering a comprehensive classification of innovations; in exposing the hurdles to innovations, in new arguments about effectiveness of technology applications, and in time efficiency of education.

- Implementation

- Educational technology

- Time efficiency

Serdyukov, P. (2017), "Innovation in education: what works, what doesn’t, and what to do about it?", Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning , Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 4-33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-10-2016-0007

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2017, Peter Serdyukov

Published in the Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning . This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Necessity is the mother of invention (Plato).

Introduction

Education, being a social institution serving the needs of society, is indispensable for society to survive and thrive. It should be not only comprehensive, sustainable, and superb, but must continuously evolve to meet the challenges of the fast-changing and unpredictable globalized world. This evolution must be systemic, consistent, and scalable; therefore, school teachers, college professors, administrators, researchers, and policy makers are expected to innovate the theory and practice of teaching and learning, as well as all other aspects of this complex organization to ensure quality preparation of all students to life and work.

Here we present a systemic discussion of educational innovations, identify the barriers to innovation, and outline potential directions for effective innovations. We discuss the current status of innovations in US education, what educational innovation is, how innovations are being integrated in schools and colleges, why innovations do not always produce the desired effect, and what should be done to increase the scale and rate of innovation-based transformations in our education system. We then offer recommendations for the growth of educational innovations. As examples of innovations in education, we will highlight online learning and time efficiency of learning using accelerated and intensive approaches.

Innovations in US education

For an individual, a nation, and humankind to survive and progress, innovation and evolution are essential. Innovations in education are of particular importance because education plays a crucial role in creating a sustainable future. “Innovation resembles mutation, the biological process that keeps species evolving so they can better compete for survival” ( Hoffman and Holzhuter, 2012 , p. 3). Innovation, therefore, is to be regarded as an instrument of necessary and positive change. Any human activity (e.g. industrial, business, or educational) needs constant innovation to remain sustainable.

The need for educational innovations has become acute. “It is widely believed that countries’ social and economic well-being will depend to an ever greater extent on the quality of their citizens’ education: the emergence of the so-called ‘knowledge society’, the transformation of information and the media, and increasing specialization on the part of organizations all call for high skill profiles and levels of knowledge. Today’s education systems are required to be both effective and efficient, or in other words, to reach the goals set for them while making the best use of available resources” ( Cornali, 2012 , p. 255). According to an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report, “the pressure to increase equity and improve educational outcomes for students is growing around the world” ( Vieluf et al. , 2012 , p. 3). In the USA, underlying pressure to innovate comes from political, economic, demographic, and technological forces from both inside and outside the nation.

Many in the USA seem to recognize that education at all levels critically needs renewal: “Higher education has to change. It needs more innovation” ( Wildavsky et al. , 2012 , p. 1). This message, however, is not new – in the foreword to the 1964 book entitled Innovation in Education, Arthur Foshay, Executive Officer of The Horace Mann-Lincoln Institute of School Experimentation, wrote, “It has become platitudinous to speak of the winds of change in education, to remind those interested in the educational enterprise that a revolution is in progress. Trite or not, however, it is true to say that changes appear wherever one turns in education” ( Matthew, 1964 , p. v).

Yet, more than 50 years later, we realize that the actual pace of educational innovations and their implementation is too slow as shown by the learning outcomes of both school and college graduates, which are far from what is needed in today’s world. Jim Shelton, Assistant Deputy Secretary of the Office of Innovation and Improvement in the US Department of Education, writes, “Whether for reasons of economic growth, competitiveness, social justice or return on tax-payer investment, there is little rational argument over the need for significant improvement in US educational outcomes. Further, it is irrefutable that the country has made limited improvement on most educational outcomes over the last several decades, especially when considered in the context of the increased investment over the same period. In fact, the total cost of producing each successful high school and college graduate has increased substantially over time instead of decreasing – creating what some argue is an inverted learning curve […].”

“Education not only needs new ideas and inventions that shatter the performance expectations of today’s status quo; to make a meaningful impact, these new solutions must also “scale,” that is grow large enough, to serve millions of students and teachers or large portions of specific underserved populations” ( Shelton, 2011 ). Yet, something does not work here.

Lack of innovation can have profound economic and social repercussions. America’s last competitive advantage, warns Harvard Innovation Education Fellow Tony Wagner, its ability to innovate, is at risk as a result of the country’s lackluster education system ( Creating innovators, 2012 ). Derek Bok, a former Harvard University President, writes, “[…] neither American students nor our universities, nor the nation itself, can afford to take for granted the quality of higher education and the teaching and learning it provides” ( Bok, 2007 , p. 6). Hence it is central for us to make US education consistently innovative and focus educational innovations on raising the quality of learning at all levels. Yet, though there is a good deal of ongoing educational research and innovation, we have not actually seen discernable improvements in either school students’ or college graduates’ achievements to this day. Suffice it to mention a few facts. Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) evaluations keep revealing disappointing results for our middle school ( Pew Research Center, 2015 ); a large number of high school graduates are not ready for college ( College preparedness, 2012 ); and employers, in turn, are often dissatisfied with college graduates ( Thomson, 2015 ; Jaschik, 2015 ). No one, be they students, parents, academia, business, or society as a whole, are pleased with these outcomes. Could it be that our education system is not sufficiently innovative?

Danny Crichton, an entrepreneur, in his blog The Next Wave of Education Innovation writes expressly, “Few areas have been as hopeful and as disappointing as innovation in education. Education is probably the single most important function in our society today, yet it remains one of the least understood, despite incredible levels of investment from venture capitalists and governments. Why do students continue to show up in a classroom or start an online course? How do we guide students to the right knowledge just as they need to learn it? We may have an empirical inkling and some hunches, but we still lack any fundamental insights. That is truly disappointing. With the rise of the internet, it seemed like education was on the cusp of a complete revolution. Today, though, you would be excused for not seeing much of a difference between the way we learn and how we did so twenty years ago” ( Crichton, 2015 ).

Editors of the book Reinventing Higher Education: The Promise of Innovation , Ben Wildavsky, Andrew Kelly, and Kevin Carey write, “The higher education system also betrays an innovation deficit in another way: a steady decline in productivity driven by a combination of static or declining output paired with skyrocketing prices ( Wildavsky et al. , 2012 , p. 3). This despairing mood is echoed by Groom and Lamb’s statement in EDUCAUSE Review, “Today, innovation is increasingly conflated with hype, disruption for disruption’s sake, and outsourcing laced with a dose of austerity-driven downsizing” ( Groom and Lamb, 2014 ).

USA success has always been driven by innovation and has a unique capacity for growth ( Zeihan, 2014 ). Nevertheless, it is indeed a paradox: while the USA produces more research, including in education, than any other country ( Science Watch, 2009 ), we do not see much improvement in the way our students are prepared for life and work. The USA can be proud of great scholars, such as John Dewey, B.F. Skinner, Abraham Maslow, Albert Bandura, Howard Gardner, Jerome Bruner, and many others who have contributed a great deal to the theory of education. Yet, has this theory yielded any innovative approaches for the teaching and learning practice that have increased learning productivity and improved the quality of the output?

The USA is the home of the computer and the internet, but has the information revolution helped to improve the quality of learning outcomes? Where and how, then, are all these educational innovations applied? It seems, write Spangehl and Hoffman, that “American education has taken little advantage of important innovations that would increase instructional capacity, effectiveness, and productivity” (2012 , p. 21). “The new ‘job factory’ role American universities have awkwardly stuffed themselves into may be killing the modern college student’s spirit and search for meaning” ( Mercurio, 2016 ).

What is interesting here is that while we are still undecided as to what to do with our struggling schools and universities and how to integrate into them our advanced inventions, other nations are already benefiting from our innovations and have in a short time successfully built world-class education systems. It is ironic that an admirable Finnish success was derived heavily from US educational research. Pasi Sahlberg, a Finnish educator and author of a bestselling book, The Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change In Finland , said in an interview to the Huffington Post, “American scholars and their writings, like Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences, have been influential in building the much-admired school system in Finland” ( Rubin, 2015 ); so wrote other authors ( Strauss, 2014 ). Singapore, South Korea, China, and other forward-looking countries also learned from great US educational ideas.

We cannot say that US educators and society are oblivious to the problems in education: on the contrary, a number of educational movements have taken place in recent US history (e.g. numerous educational reforms since 1957 to this day, including recent NCLB, Race to the Top, and the Common Core). Universities and research organizations opened centers and laboratories of innovation (Harvard Innovation Lab, Presidential Innovation Laboratory convened by American Council on Education, Center for Innovation in Education at the University of Kentucky, NASA STEM Innovation Lab, and recently created National University Center for Innovation in Learning). Some institutions introduced programs focusing on innovation (Master’s Program in Technology, Innovation, and Education at Harvard Graduate School of Education; Master of Arts in Education and Innovation at the Webster University). New organizations have been set up (The International Centre for Innovation in Education, Innovative Schools Network, Center for Education Reform). Regular conferences on the topic are convened (AERA, ASU-GSV Summit, National Conference on Educational Innovation, The Nueva School for the Innovative Learning Conference). Excellent books have been written by outstanding innovators such as Andy Hargreaves (2003) , Hargreaves and Shirley (2009) , Hargreaves et al. (2010) , Michael Fullan (2007, 2010) , Yong Zhao (2012) , Pasi Sahlberg (2011) , Tony Wagner (2012) , Mihaliy Csikszentmihalyi (2013) , and Ken Robinson (2015) . There is even an Office of Innovation and Improvement in the US Department of Education, which is intended to “[…] drive education innovation by both seeding new strategies, and bringing proven approaches to scale” ( Office of Innovation and Improvement, 2016 ). And still, innovations do not take hold in American classrooms on a wide scale, which may leave the nation behind in global competition.

Society’s failure to anticipate the problems and their outcomes may have unpredictable consequences, as Pulitzer Prize winner and Professor Jared Diamond, University of California, Los Angeles, writes in his book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed ( Diamond, 2005 ). Yong Zhao interpreted Diamond’s findings as “[…] society’s inability to perceive or unwillingness to accept large and distant changes – and thus work to come up with the right response – is among one of the chief reasons that societies fail. This inability also leads human beings to look for short-term outcomes and seek immediate gratification” ( Zhao, 2012 , p. 162). It looks like the issue of educational innovation goes beyond the field itself and requires a strong societal response.

Three big questions arise from this discussion: why, having so many innovators and organizations concerned with innovations, does our education system not benefit from them? What interferes with creating and, especially, implementing transformative, life-changing, and much-needed innovations across schools and colleges in this country? How can we grow, support, and disseminate worthy innovations effectively so that our students succeed in both school and university and achieve the best learning outcomes that will adequately prepare them for life and work? Let us first take a look at what is an educational innovation.

What is educational innovation?

Creativity is thinking up new things. Innovation is doing new things (Theodore Levitt).

To innovate is to look beyond what we are currently doing and develop a novel idea that helps us to do our job in a new way. The purpose of any invention, therefore, is to create something different from what we have been doing, be it in quality or quantity or both. To produce a considerable, transformative effect, the innovation must be put to work, which requires prompt diffusion and large-scale implementation.

Innovation is generally understood as “[…] the successful introduction of a new thing or method” ( Brewer and Tierney, 2012 , p. 15). In essence, “[…] innovation seems to have two subcomponents. First, there is the idea or item which is novel to a particular individual or group and, second, there is the change which results from the adoption of the object or idea” ( Evans, 1970 , p. 16). Thus, innovation requires three major steps: an idea, its implementation, and the outcome that results from the execution of the idea and produces a change. In education, innovation can appear as a new pedagogic theory, methodological approach, teaching technique, instructional tool, learning process, or institutional structure that, when implemented, produces a significant change in teaching and learning, which leads to better student learning. So, innovations in education are intended to raise productivity and efficiency of learning and/or improve learning quality. For example, Khan’s Academy and MOOCs have opened new, practically unlimited opportunities for massive, more efficient learning.

Efficiency is generally determined by the amount of time, money, and resources that are necessary to obtain certain results. In education, efficiency of learning is determined mainly by the invested time and cost. Learning is more efficient if we achieve the same results in less time and with less expense. Productivity is determined by estimating the outcomes obtained vs the invested effort in order to achieve the result. Thus, if we can achieve more with less effort, productivity increases. Hence, innovations in education should increase both productivity of learning and learning efficiency.

Educational innovations emerge in various areas and in many forms. According to the US Office of Education, “There are innovations in the way education systems are organized and managed, exemplified by charter schools or school accountability systems. There are innovations in instructional techniques or delivery systems, such as the use of new technologies in the classroom. There are innovations in the way teachers are recruited, and prepared, and compensated. The list goes on and on” ( US Department of Education, 2004 ).

Innovation can be directed toward progress in one, several, or all aspects of the educational system: theory and practice, curriculum, teaching and learning, policy, technology, institutions and administration, institutional culture, and teacher education. It can be applied in any aspect of education that can make a positive impact on learning and learners.

In a similar way, educational innovation concerns all stakeholders: the learner, parents, teacher, educational administrators, researchers, and policy makers and requires their active involvement and support. When considering the learners, we think of studying cognitive processes taking place in the the brain during learning – identifying and developing abilities, skills, and competencies. These include improving attitudes, dispositions, behaviors, motivation, self-assessment, self-efficacy, autonomy, as well as communication, collaboration, engagement, and learning productivity.

To raise the quality of teaching, we want to enhance teacher education, professional development, and life-long learning to include attitudes, dispositions, teaching style, motivation, skills, competencies, self-assessment, self-efficacy, creativity, responsibility, autonomy to teach, capacity to innovate, freedom from administrative pressure, best conditions of work, and public sustenance. As such, we expect educational institutions to provide an optimal academic environment, as well as materials and conditions for achieving excellence of the learning outcomes for every student (program content, course format, institutional culture, research, funding, resources, infrastructure, administration, and support).

Education is nourished by society and, in turn, nourishes society. The national educational system relies on the dedication and responsibility of all society for its effective functioning, thus parental involvement, together with strong community and society backing, are crucial for success.

political (NCLB (No Child Left Behind Act), Race to the Top);

social (Equal Opportunities Act, affirmative action policy, Indivuals with Disabilities Education Act);

philosophical (constructivism, objectivism);

cultural (moral education, multiculturalism, bilingual education);

pedagogical (competence-based education, STEM (curriculum choices in school: Science, Technology, English, and Mathematics);

psychological (cognitive science, multiple intelligencies theory, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, learning style theory); and

technological (computer-based learning, networked learning, e-learning).

Though these innovations left a significant mark on education, which of them helped improve productivity and quality of learning? Under NCLB, we placed too much focus on accountability and assessment and lost sight of many other critical aspects of education. In drawing too much attention to technology innovations, we may neglect teachers and learners in the process. Stressing the importance of STEM at the expense of music, arts and physical culture ignores young people’s personal, social, emotional, and moral development. Reforming higher education without reforming secondary education is futile. Trying to change education while leaving disfunctional societal and cultural mechanisms intact is doomed. It is crucial, therefore, when innovating to ask, “What is this innovation for?” “How will it work?” and “What effect will it produce?”

Many of us educators naively believe grand reforms or powerful technologies will transform our education system. Did we not expect NCLB to change our schools for the better? Did we not hope that new information technologies would make education more effective and relieve teachers from tedious labor? However, again and again we realize that neither loud reforms nor wondrous technology will do the hard work demanded of teachers and learners.

Innovations can be categorized as evolutionary or revolutionary ( Osolind, 2012 ), sustaining or disruptive ( Christensen and Overdorf, 2000 ; Yu and Hang, 2010 ). Evolutionary innovations lead to incremental improvement but require continuity; revolutionary innovations bring about a complete change, totally overhauling and/or replacing the old with the new, often in a short time period. Sustaining innovation perpetuates the current dimensions of performance (e.g. continuous improvement of the curriculum), while disrupting innovation, such as a national reform, radically changes the whole field. Innovations can also be tangible (e.g. technology tools) and intangible (e.g. methods, strategies, and techniques). Evolutionary and revolutionary innovations seem to have the same connotation as sustaining and disruptive innovations, respectively.

When various innovations are being introduced in the conventional course of study, for instance Universal Design of Learning ( Meyer et al. , 2014 ); or more expressive presentation of new material using multimedia; or more effective teaching methods; or new mnemonic techniques, students’ learning productivity may rise to some extent. This is an evolutionary change. It partially improves the existing instructional approach to result in better learning. Such learning methods as inquiry based, problem based, case study, and collaborative and small group are evolutionary innovations because they change the way students learn. Applying educational technology (ET) in a conventional classroom using an overhead projector, video, or iPad, are evolutionary, sustaining innovations because they change only certain aspects of learning. National educational reforms, however, are always intended to be revolutionary innovations as they are aimed at complete system renovation. This is also true for online learning because it produces a systemic change that drastically transforms the structure, format, and methods of teaching and learning. Some innovative approaches, like “extreme learning” ( Extreme Learning, 2012 ), which use technology for learning purposes in novel, unusual, or nontraditional ways, may potentially produce a disruptive, revolutionary effect.

Adjustment or upgrading of the process: innovation can occur in daily performance and be seen as a way to make our job easier, more effective, more appealing, or less stressful. This kind of innovation, however, should be considered an improvement rather than innovation because it does not produce a new method or tool. The term innovative, in keeping with the dictionary definition, applies only to something new and different, not just better, and it must be useful ( Okpara, 2007 ). Educators, incidentally, commonly apply the term “innovative” to almost any improvement in classroom practices; yet, to be consistent, not any improvement can be termed in this way. The distinction between innovation and improvement is in novelty and originality, as well as in the significance of impact and scale of change.

Modification of the process: innovation that significantly alters the process, performance, or quality of an existing product (e.g. accelerated learning (AL), charter school, home schooling, blended learning).

Transformation of the system: dramatic conversion (e.g. Bologna process; Common Core; fully automated educational systems; autonomous or self-directed learning; online, networked, and mobile learning).

First-level innovations (with a small i ) make reasonable improvements and are important ingredients of everyday life and work. They should be unequivocally enhanced, supported, and used. Second-level innovations either lead to a system’s evolutionary change or are a part of that change and, thus, can make a considerable contribution to educational quality. But we are more concerned with innovations of the third level (with a capital I), which are both breakthrough and disruptive and can potentially make a revolutionary, systemic change.

qualitative: better knowledge, more effective skills, important competencies, character development, values, dispositions, effective job placement, and job performance; and

quantitative: improved learning parameters such as test results, volume of information learned, amount of skills or competencies developed, college enrollment numbers, measured student performance, retention, attrition, graduation rate, number of students in class, cost, and time efficiency.

Innovation can be assessed by its novely, originality, and potential effect. As inventing is typically a time-consuming and cost-demanding experience, it is critical to calculate short-term and long-term expenses and consequences of an invention. They must demonstrate significant qualitative and/or quantitative benefits. As a psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi writes, “human well-being hinges on two factors: the ability to increase creativity and the ability to develop ways to evaluate the impact of new creative ideas” (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013, p. 322).

In education, we can estimate the effect of innovation via learning outcomes or exam results, teacher formative and summative, formal and informal assessments, and student self-assessment. Innovation can also be computed using such factors as productivity (more learning outcomes in a given time), time efficiency (shorter time on studying the same material), or cost efficiency (less expense per student) data. Other evaluations can include the school academic data, college admissions and employment rate of school graduates, their work productivity and career growth.

singular/local/limited;

multiple/spread/significant; and

system-wide/total.

This gradation correlates with the three levels of innovation described above: adjustment, modification, and transformation. To make a marked difference, educational innovation must be scalable and spread across the system or wide territory. Prominent examples include Khan Academy in the USA, GEEKI Labs in Brazil (GEEKI), and BRIDGE International Academies in Kenya (BRIDGE). Along with scale, the speed of adoption or diffusion, and cost are critical for maximizing the effect of innovation.

Innovations are nowadays measured and compared internationally. According to the 2011 OECD report ( OECD, 2014 ), the USA was in 24th place in educational innovativeness in the world. This report singled out the use of student assessments for monitoring progress over time as the top organizational innovation, and the requirement that students were to explain and elaborate on their answers during science lessons as the top pedagogic innovation in the USA. Overall, the list of innovations selected by OECD was disappointingly unimpressive.

Innovations usually originate either from the bottom of the society (individual inventors or small teams) – bottom-up or grass root approach, or from the top (business or government) – top-down or administrative approach. Sometimes, innovations coming from the top get stalled on their way to the bottom if they do not accomplish their goal and are not appreciated or supported by the public. Should they rise from the bottom, they may get stuck on the road to the top if they are misunderstood or found impractical or unpopular. They can also stop in the middle if there is no public, political, or administrative or financial backing. Thus, innovations that start at the bottom, however good they are, may suffer too many roadblocks to be able to spread and be adopted on a large scale. Consequently, it is up to politicians, administrators, and society to drive or stifle the change. Education reforms have always been top-down and, as they near the bottom, typically become diverted, diluted, lose strength, or get rejected as ineffective or erroneous. As Michael Fullan writes in the Foreword to an exciting book, Good to Great to Innovate: Recalculating the Route to Career Readiness, K012+ , “[…] there is a good deal of reform going on in the education world, but much of it misses the point, or approaches it superficially” ( Sharratt and Harild, 2015 , p. xiii).

Innovations enriching education can be homegrown (come from within the system) or be imported (originate from outside education). Examples of imported innovations that result from revolution, trend, or new idea include the information technology revolution, social media, medical developments (MRI), and cognitive psychology. Innovations can also be borrowed from superior international theories and practices (see Globalization of Education chapter). National reform may also be a route to innovation, for instance when a government decides to completely revamp the system via a national reform, or when an entire society embarks on a new road, as has happened recently in Singapore, South Korea, and Finland.

Innovations may come as a result of inspiration, continuous creative mental activity, or “supply pushed” through the availability of new technological possibilities in production, or “demand led” based on market or societal needs ( Brewer and Tierney, 2012 , p. 15). In the first case, we can have a wide variety of ideas flowing around; in the second, we observe a ubiquitous spread of educational technologies across educational system at all levels; in the third, we witness a growth of non-public institutions, such as private and charter schools and private universities.

Innovation in any area or aspect can make a change in education in a variety of ways. Ultimately, however, innovations are about quality and productivity of learning (this does not mean we can forget about moral development, which prepares young people for life, work, and citizenship) ( Camins, 2015 ). Every innovation must be tested for its potential efficiency. The roots of learning efficiency lie, however, not only in innovative technologies or teaching alone but even more in uncovering potential capacities for learning in our students, their intellectual, emotional, and psychological spheres. Yet, while innovations in economics, business, technology, and engineering are always connected to the output of the process, innovation in education does not necessarily lead to improving the output (i.e. students’ readiness for future life and employment). Test results, degrees, and diplomas do not signify that a student is fully prepared for his or her career. Educational research is often disconnected from learning productivity and efficiency, school effectiveness, and quality output. Innovations in educational theories, textbooks, instructional tools, and teaching techniques do not always produce a desired change in the quality of teaching and learning. What, then, is the problem with our innovations? Why do not we get more concerned with learning productivity and efficiency? As an example, let us look at technology applications in teaching and learning.

Effects of technology innovations in education

A tool is just an opportunity with a handle (Kevin Kelly).

When analyzing innovations of our time, we cannot fail to see that an overwhelming majority of them are tangible, being either technology tools (laptops, iPads, smart phones) or technology-based learning systems and materials, e.g., learning management system (LMS), educational software, and web-based resources. Technology has always served as both a driving force and instrument of innovation in any area of human activity. It is then natural for us to expect that innovations based on ET applications can improve teaching and learning. Though technology is a great asset, nonetheless, is it the single or main source of today’s innovations, and is it wise to rely solely on technology?

The rich history of ET innovations is filled with optimism. Just remember when tape recorders, video recorders, TV, educational films, linguaphone classes, overhead projectors, and multimedia first appeared in school. They brought so much excitement and hope into our classrooms! New presentation formats catered to various learning styles. Visuals brought reality and liveliness into the classrooms. Information and computer technology (ICT) offered more ways to retrieve information and develop skills. With captivating communication tools (iPhones, iPads, Skype, FaceTime), we can communicate with anybody around the world in real time, visually, and on the go. Today we are excited about online learning, mobile learning, social networking learning, MOOCs, virtual reality, virtual and remote laboratories, 3D and 4D printing, and gamification. But can we say all this is helping to produce better learning? Are we actually using ET’s potential to make a difference in education and increase learning output?

Larry Cuban, an ET researcher and writer, penned the following: “Since 2010, laptops, tablets, interactive whiteboards, smart phones, and a cornucopia of software have become ubiquitous. We spent billions of dollars on computers. Yet has academic achievement improved as a consequence? Has teaching and learning changed? Has use of devices in schools led to better jobs? These are the basic questions that school boards, policy makers, and administrators ask. The answers to these questions are ‘no,’ ‘no,’ and ‘probably not.’” ( Cuban, 2015 ). This cautionary statement should make us all think hard about whether more technology means better learning.

Technology is used in manufacturing, business, and research primarily to increase labor productivity. Because integrating technology into education is in many ways like integrating technology into any business, it makes sense to evaluate technological applications by changes in learning productivity and quality. William Massy and Robert Zemsky wrote in their paper, “Using Information Technology to Enhance Academic Productivity,” that “[…] technology should be used to boost academic productivity” ( Massy and Zemsky, 1995 ). National Educational Technology Standards also addressed this issue by introducing a special rubric: “Apply technology to increase productivity” ( National Educational Technology Standards, 2004 ). Why then has technology not contributed much to the productivity of learning? It may be due to a so-called “productivity paradox” ( Brynjolfsson, 1993 ), which refers to the apparent contradiction between the remarkable advances in computer power and the relatively slow growth of productivity at the level of the whole economy, individual firms, and many specific applications. Evidently, this paradox relates to technology applications in education.

A conflict between public expectations of ET effectiveness and actual applications in teaching and learning can be rooted in educators’ attitudes toward technology. What some educational researchers write about technology in education helps to reveal the inherent issue. The pillars and building blocks of twenty-first century learning, according to Linda Baer and James McCormick (2012 , p. 168), are tools, programs, services, and policies such as web-enabled information storage and retrieval systems, digital resources, games, and simulations, eAdvising and eTutoring, online revenue sharing, which are all exclusively technological innovations. They are intended to integrate customized learning experiences, assessment-based learning outcomes, wikis, blogs, social networking, and mobile learning. The foundation of all this work, as these authors write, is built on the resources, infrastructure, quality standards, best practices, and innovation.

These are all useful, tangible things, but where are the intangible innovations, such as theoretical foundation, particularly pedagogy, psychology, and instructional methodology that are a true underpinning of teaching and learning? The emphasis on tools seems to be an effect of materialistic culture, which covets tangible, material assets or results. Similarly, today’s students worry more about grades, certificates, degrees, and diplomas (tangible assets) than about gaining knowledge, an intangible asset ( Business Dictionary, 2016 ). We may come to recognize that modern learning is driven more by technological tools than by sound theory, which is misleading.

According to the UNESCO Innovative Teaching and Learning (ITL) Research project conducted in several countries, “ICT has great potential for supporting innovative pedagogies, but it is not a magic ingredient.” The findings suggest that “[…] when considering ICT it is important to focus not on flash but on the student learning and 21st century skills that ICT can enable” ( UNESCO, 2013 ). As Zhao and Frank (2003) argue in their ecological model of technology integration in school, we should be interested in not only how much computers are used but also how computers are used. Evidently, before starting to use technology we have to ask first, “What technology tools will help our students to learn math, sciences, literature and languages better, and how to use them efficiently to improve the learning outcomes?”