Proceedings of the First International Volga Region Conference on Economics, Humanities and Sports (FICEHS 2019)

Civilizations: Challenges and Answers of the Modern World

The article presents the analysis of one of the main components of modern society and state - civilization. According to the research on modern civilizations, the chronological framework of which falls on the XX-XXI centuries, this article considers the changes that have become epochal. The authors studied the scientific works of native and foreign scientists in the sphere of history, political science, cultural studies and sociology. The authors focus on the emergence of various challenges faced by modern civilization. They underline the need to study the civilizational processes that are a multifaceted phenomenon and have a significant impact on world history, world politics, world culture.

Download article (PDF)

Cite this article

The human challenge: Continuing civilization indefinitely

SAN FRANCISCO — Human beings have altered the Earth so much that human extinction is a real possibility if people continue on their current path. But if they can figure out a way to live sustainably, at least some human civilizations could become quasi-immortal, one researcher says.

The challenge is to change the societal outlook to one that is long-term and accounts for humanity's central role in shaping the planet's destiny, instead of one that reacts to immediate crises and thinks in the short term.

"For our civilization to become a new kind of entity on the planet, we need to live comfortably, over the long haul, with world-changing technology," David H. Grinspoon, an astrobiologist at the Library of Congress, said Dec. 12 here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Not everyone agrees that a long-term perspective is possible or that it will prevent Earth's demise. In fact, one astronomer said humans are hardwired to live in the world of the "immediate." [ Doomsday: 9 Real Ways Earth Could End ]

Human era For most of the last 4.5 billion years, Earth has been shaped by natural disasters, such as the dinosaur-killing asteroid , or biological forces, such as the rise of cyanobacteria that created the planet's oxygen-rich atmosphere, Grinspoon said.

But in the current epoch, humans are fundamentally altering the planet.

"The Earth is becoming unrecognizable from the planet it was before we became a geological force," a period that some have dubbed the Anthropocene Era , Grinspoon said.

Habitat destruction, unchecked population growth, global warming and other challenges of modern civilization have put humanity at risk. The problem is that right now, though humans have a large unintentional impact on the planet, they don't consciously control that impact, he said.

Civilizational crossroads Now, civilization is at a crossroads, Grinspoon says: If global warming and other Earth-altering phenomena continue unchecked, humanity could die out. But, if Homo sapiens can overcome those challenges, the people who do survive could build a longer-lived civilization than any that thrived in the past. In essence, at a bifurcation in history, civilizations could be capped at a few thousand years or, alternatively, last for hundreds of thousands — or even millions — of years.

"If even a small fraction of people come through the bifurcation in lifetime of civilizations, then they may become quasi-immortal," he said.

The good news, Grinspoon said, is that humans are now trying to shape the planet's future. For instance, nations consciously took political action to shrink the ozone hole , are working to curb carbon emissions and are looking for ways to prevent asteroids from bombarding Earth.

In the future, societies could learn to geoengineer their environment, prevent future Ice Ages, or even (in the distant future) stave off Earth's end, when the sun balloons into a red giant and engulfs the planet in scorching heat, Grinspoon said.

Central players In order for humanity to have any hope for survival, however, it must learn to harness technology wisely, Grinspoon said. Humanity must also shift from its short-term, regional outlook that denies humans' impact on the Earth to a multigenerational and global outlook that consciously accepts its crucial role in Earth's fate. [ Big Bang to Civilization: 10 Amazing Origin Events ]

That outlook may be disturbing for many people, including scientists accustomed to seeing humans as inconsequential specks in the vast story of the universe, and environmentalists who liken humanity to criminal interlopers guilty of destroying the Earth, Grinspoon said.

But Grinspoon argued that those views of humanity are counterproductive, because they make humanity's problems seem intractable.

"We are central to the story," Grinspoon said.

Instead, a better metaphor may be people who somehow awoke at the helm of a very large bus speeding down the highway, he said. "We have to figure out how to drive this thing to avoid the catastrophe," he said.

Civilization is facing a bottleneck, said Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer with the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

"Eventually, you either have to stabilize the population and reuse everything, or you have to do something else," such as go into space to live or mine for resources.

But Shostak questioned whether a more global, long-term outlook is reasonable to expect.

"The way we're wired is to be worried about the immediate problems," Shostak told LiveScience.

And it's not always possible to have a long-term perspective. For instance, London was engulfed in a miasma of toxic fumes from coal-fired home heating in the 1870s, and nobody could come up with a solution. Then, coal-fired heating gave way to other heat sources, and the problem solved itself, he said.

"You don't often see what's right around the corner," Shostak said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+ . Follow us @livescience , Facebook and Google+ . Original article on LiveScience.

- Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

- Doom and Gloom: Top 10 Post-Apocalyptic Worlds

- Crowded Planet: 7 (Billion) Population Milestones

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Civilization and Its Consequences

Professor of History & Politics and Director, International & Research, School of Humanities & Communication Arts, Western Sydney University

- Published: 11 February 2016

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article outlines the origins and meanings of the concept of civilization in Western political thought. In doing so it necessarily explores the nature of the relationship between civilization and closely related ideas such as progress and modernity. In exploring these concepts, some of their less savory aspects are revealed, including things done in the name of civilization, such as conquest and colonization under the guise of the “burden of civilization.” The article outlines other important aspects, including the relationships between civilization and war and between civilization and the environment. It concludes with a discussion about rethinking and restructuring some of our perspectives on civilization.

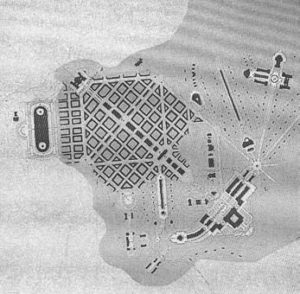

Civilization refers to both a process and a destination. It describes the process of a social collective becoming civilized, or progressing from a state of nature, savagery, or barbarism to a state of civilization. It describes a state of human society marked by significant urbanization, social and professional stratification, the luxury of leisure time, and corresponding advancements in the arts and sciences. The capacity for reasonably complex sociopolitical organization and self-government according to prevailing standards has long been thought of as a central requirement of civilization.

There is widespread greement in the Western world that civilization is a good thing, or at least that it is better than the alternatives: barbarism, savagery, or a state of nature of some sort. In theory, as time passes and the further we get away from the Big Bang and the primordial soup, the more we progress both as a species and as individual human beings; the more we progress, the more civilized we become individually and collectively; the more civilized we become, the further we are removed from the vestiges of savagery and barbarism. In fact, for many in the West civilization, progress, and modernity are by definition good things (e.g., Stark 2014 ). Samuel Huntington has summarized the state of debate rather succinctly: to be civilized is good, and to be uncivilized is bad (1998, 40).

As with so many debates, however, rarely are things so clearly black or white; there are usually many more shades of gray. For instance, in stark contrast to the rosy picture of civilization and modernity suggested above, Zygmunt Bauman (2001 , 4, 6) has alarmingly highlighted the dark side, suggesting that the Holocaust was not so much “a temporary suspension of the civilizational grip in which human behaviour is normally held” but a “‘paradigm’ of modern civilization” and modernity. This is not necessarily to suggest that civilization is “bad” or not worth having or being a part of; it is just to highlight that along with the upsides there are some potential downsides, even a “dark side” ( Alexander 2013 ).

To enable a better understanding of the various perspectives on civilization, this article begins by outlining what civilization means, particularly in the history of Western political thought (for other traditions of thought see, for example, Weismann 2014 ). It then examines the significance and nature of the rather symbiotic relationship between civilization and concepts such as progress and modernity. The article then explores some of the potential consequences that go along with or are outcomes of the pursuit of these ideals, the less commonly acknowledged darker side of civilization. Included here are other important dimensions of the relationship between civilization and progress, such as the relationship between civilization and war and the exploitative nature of the relationship between civilization and the environment or the natural world more generally. The conclusion proposes a slightly different way of thinking about civilization that might help us avoid some of the pitfalls that lead away from the light and into darkness.

The Meaning of Civilization

The word civilization has its foundations in the French language, deriving from words such as civil (thirteenth century) and civilité (fourteenth century), which in turn derive from the Latin civitas . Prior to the appearance of civilization , words such as poli or polite, police (which broadly meant law and order, including government and administration), civilizé , and civilité had been in wide use, but none could adequately meet the evolving and expanding demands on the French language. Upon the appearance of the verb civilizer sometime in the sixteenth century, which provided the basis for the noun, the coining of civilization was only a matter of time, because it was a neologism whose time had come. As Emile Benveniste states, “ [C]ivilité , a static term, was no longer sufficient,” requiring the coining of a term that “had to be called civilization in order to define together both its direction and continuity” (1971, 292).

The first known recorded use of civilization in French gave it a meaning quite different than what is generally associated with it today. For some time civilizer had been used in jurisprudence to describe the transformation of a criminal matter into a civil one; hence civilization was defined in the Trévoux Dictionnaire universel of 1743 as a “term of jurisprudence. An act of justice or judgement that renders a criminal trial civil. Civilization is accomplished by converting informations ( informations ) into inquests ( enquêtes ) or by other means” ( Starobinski 1993 , 1). Just when the written word civilization first appeared in its more modern sense is open to conjecture. Despite extensive enquiries, Lucien Febvre states that he has “not been able to find the word civilization used in any French text published prior to the year 1766,” when it appeared in a posthumous publication by M. Boulanger, Antiquité dévoilée par ses usages . The passage reads, “When a savage people has become civilized, we must not put an end to the act of civilization by giving it rigid and irrevocable laws; we must make it look upon the legislation given to it as a form of continuous civilization ” ( Febvre 1973 , 220–222). It is evident that from early on civilization was used to represent both an ongoing process and a state of development that is an advance on savagery.

An initial concern with the concept of civilization gave way to detailed studies of civilizations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in large part instigated by the foundation and development of the fields of anthropology and ethnography (e.g., Bagby 1959 ; Coulborn 1959 ; Quigley 1961 ; Sorokin 1957 ; Melko 1969 ). Such a shift led to claims that a broader concern with the normative aspects of civilization had “lost some of its cachet” ( Huntington 1998 , 41). The result of this shift was a preoccupation with narrower definitions such as that offered by Emile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss (1971 , 811): “A civilization constitutes a kind of moral milieu encompassing a certain number of nations, each national culture being only a particular form of the whole.” A leading exponent of the comparative study of civilizations was Arnold Toynbee , who did not completely set aside the ideal of civilization, for he noted, “Civilizations have come and gone, but Civilization (with a big ‘C’) has succeeded” or endured (1948a , 24; 1948b). Toynbee also endeavored to articulate the link between “civilizations in the plural and civilization in the singular,” noting that the former refers to “particular historical exemplifications of the abstract idea of civilization.” This is defined in “spiritual terms,” in which he “equate[s] civilization with a state of society in which there is a minority of the population, however small, that is free from the task, not merely of producing food, but of engaging in any other of the economic activities—e.g. industry and trade—that have to be carried on to keep the life of the society going on the material plane at the civilizational level” (1972, 44–45).

Toynbee’s argument concerning the organization of society as marked by the specialization of skills, the move toward elite professions, and the effective use of leisure time has long been held in connection with the advancement of civilization (and civilized society). Hobbes (1985 , 683), for example, insisted that the “procuring of the necessities of life … was impossible, till the erecting of great Common-wealths,” which were “the mother of Peace , and Leasure ,” which was in turn “the mother of Philosophy ; … Where first were great and flourishing Cities , there was first the study of Philosophy .” This general line of argument has been made time and again throughout history. Such accounts of the relationship among civilization, society, and government fit with Anthony Pagden’s (1988 , 39) claim that the “philosophical history of civilization was, then, a history of progressive complexity and progressive refinement which followed from the free expression of those faculties which men possess only as members of a community.”

R.G. Collingwood has outlined three aspects of civilization: economic, social, and legal. Economic civilization is marked not simply by the pursuit of riches—which might actually be inimical to economic civilization—but by “the civilized pursuit of wealth.” The realm of “social civilization” is the forum in which humankind’s sociability is satisfied by “the idea of joint action,” or what we might call community. The final mark of civilization is “a society governed by law,” and not so much by criminal law as by civil law—“the law in which claims are adjusted between its members”—in particular (1992, 502–511). For Collingwood , “Civilization is something which happens to a community …. Civilization is a process of approximation to an ideal state ” (1992, 283). In essence, Collingwood is arguing that civilized society—and thus civilization itself—is guided by and operates according to the principles of the rule of law. When we combine these three elements of civilization, what they amount to is what I would call sociopolitical civilization, or the capacity of a collective to organize and govern itself under some system of laws or constitution.

This article is more concerned with the normative dimensions of civilization, but it is interesting to note a recent resurgence in international relations (IR) of studies focusing on civilizations, and not just in response to Huntington’s clash thesis. For example, reflecting on Adda Bozeman’s Politics & Culture in International History , Donald Puchala (1997 , 5) notes that “the strutting and fretting of states, and their heroes, through countless conflicts over several millennia accomplished little more than to intermittently reconstruct political geography, desecrate a sizeable proportion of humankind’s artistic and architectural heritage, waste wealth, and extinguish hundreds of millions of lives.” He adds that “the history of relations among states—be they city-, imperial-, medieval-, westphalian-, modern-, super- or nation-states—has been rather redundant, typically unpleasant and more often than not devoid of much meaning in the course of human cultural evolution.” He insists that in contrast to relations between states, “the history of relations among peoples has been of much broader human consequence.” Or as Bozeman (2010 , xv) sought to explain, the “interplay … of politics and culture has intensified throughout the world,” and this has been taking place “on the plane of international relations as well as on that of intrastate social existence and governance.” She concluded that “the territorially bounded, law-based Western-type state is no longer [if it ever was by this reading] the central principle in the actual conduct of international relations, and it should therefore not be treated as the lead norm in the academic universe” ( Bozeman 2010 , xl). The kinds of relations that both Bozeman and Puchala are referring to are relations between civilizations (see also Hall and Jackson 2007 ; Katzenstein 2010 ; Bowden 2012 ).

The “Burden of Civilization”

Not too far removed from Collingwood’s concern with the elimination of physical and moral force via social civilization are accounts of civilized society concerned with the management of violence, if only by removing it from the public sphere. Such a concern is extended in Zygmunt Bauman’s account of civilization to the more general issue of producing readily governable subjects. The “concept of civilization ,” he argues, “entered learned discourse in the West as the name of a conscious proselytising crusade waged by men of knowledge and aimed at extirpating the vestiges of wild cultures” (1987, 93).

This proselytizing crusade in the name of civilization is worth considering further. Its rationale is not too difficult to determine when one considers Starobinski’s (1993 , 31) assertion: “Taken as a value, civilization constitutes a political and moral norm. It is the criterion against which barbarity, or non-civilization, is judged and condemned.” A similar sort of argument is made by Pagden (1988 , 33), who states that civilization “describes a state, social, political, cultural, aesthetic—even moral and physical—which is held to be the optimum condition for all mankind, and this involves the implicit claim that only the civilized can know what it is to be civilized.” It is out of this implicit claim and the judgments passed in its name that the notion of the “burden of civilization” was born. And this, many have argued, is one of the less desirable aspects and outcomes of the idea of civilization ( Anghie 2005 ; Bowden 2009 ).

The argument that only the civilized know what it means to be civilized is an important one, for as Starobinski (1993 , 32) notes, the “historical moment in which the word civilization appears marks the advent of self-reflection, the emergence of a consciousness that thinks it understands the nature of its own activity.” More specifically, it marks “the moment that Western civilization becomes aware of itself reflectively, it sees itself as one civilization among others. Having achieved self-consciousness, civilization immediately discovers civilizations.” But as Norbert Elias (2000 , 5) highlights, it is not a case of Western civilization being just one among equals, for the very concept of civilization “expresses the self-consciousness of the West…. It sums up everything in which Western society of the last two or three centuries believes itself superior to earlier societies or ‘more primitive’ contemporary ones.” He further explains that in using the term civilization, “Western society seeks to describe what constitutes its special character and what it is proud of: the level of its technology, the nature of its manners, the development of its scientific knowledge or view of the world, and much more.” It is not too difficult to see how the harbingers of civilization might gravitate toward a (well-meaning) “proselytising crusade,” driven, at least in part, by a deeply held belief in the “burden of civilization” (see Bowden 2009 ).

The issue is not only the denial of the value and achievements of other civilizations, but the implication that they are in nearly irreversible decline. From this perspective their contribution to “big C” Civilization is seen as largely limited to the past, out of which comes the further implication that if anything of value is to be retrieved, it cannot be done without the assistance of a more civilized tutor. Such thinking is only too evident, for example, in Ferdinand Schiller’s mistaken claim that “the peoples of India appear to care very little for history and have never troubled to compile it” (1926, vii; cf. Guha 2002 ). The British took it upon themselves to compile such uneven accounts as that which was prepared by James Mill and published as The History of British India in 1817. Despite never having actually visited India, Mill’s History relayed to European audiences a fundamentally mistaken image of Indian civilization as eternally backward and undeveloped.

Standards of Civilization

One of the primary justifications underpinning such thinking relates to the widely held view that a capacity for reasonably complex sociopolitical organization and self-government according to prevailing standards is a central requirement of civilization. The presence, or otherwise, of the institutions of society that facilitate governance in accordance with established traditions—originally European but now more broadly Western—has long been regarded as the hallmark of the makings of, or potential for, civilization. An exemplar of the importance of society to the qualification of civilization is J. S. Mill’s “ingredients of civilization.” Mill states that whereas

a savage tribe consists of a handful of individuals, wandering or thinly scattered over a vast tract of country: a dense population, therefore, dwelling in fixed habitations, and largely collected together in towns and villages, we term civilized. In savage life there is no commerce, no manufactures, no agriculture, or next to none; a country in the fruits of agriculture, commerce, and manufactures, we call civilized. In savage communities each person shifts for himself; except in war (and even then very imperfectly) we seldom see any joint operations carried on by the union of many; nor do savages find much pleasure in each other’s society. Wherever, therefore, we find human beings acting together for common purposes in large bodies, and enjoying the pleasures of social intercourse, we term them civilized. (1977, 120)

The often overlooked implications of this value-laden conception of civilization led to what Georg Schwarzenberger (1955) described as the “standard of civilization in international law,” or what Gerrit Gong (1984) later labeled the “standard of civilization in international society.” Historically, the standard of civilization was a means used in international law to distinguish between civilized and uncivilized peoples to determine membership in the international society of states. The concept entered international legal texts and practice in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries under the influence of anthropologists and ethnologists, who drew distinctions among civilized, barbarian, and savage peoples based on their respective capacities for social cooperation and organization. Operating primarily during the European colonial period, the standard of civilization was a legal mechanism designed to set the benchmark for the ascent of non-European states to the ranks of the civilized “Family of Nations,” and with it their full recognition under international law. A civilized state required (1) basic institutions of government and public bureaucracy; (2) the organizational capacity for self-defense; (3) a published legal code and adherence to the rule of law; (4) the capacity to honor contracts in commerce and capital exchange; and (5) recognition of international law and norms, including the laws of war ( Gong 1984 ; Bowden 2004 , 2009 ). If a nation could meet these requirements, it was generally deemed to be a legitimate sovereign state, entitled to full recognition as an international personality.

The inability of many non-European societies to meet these European criteria, and the concomitant legal distinction that separated them from civilized societies, led to the unequal treaty system of capitulations. The right of extraterritoriality, as it was also known, regulated relations between sovereign civilized states and quasi-sovereign uncivilized states in regard to their respective rights over, and obligations to, the citizens of civilized states living and operating in countries where capitulations were in force. As the Italian jurist Pasquale Fiore (1918 , 362) explains, in “principle, Capitulations are derogatory to the local ‘common’ law; they are based on the inferior state of civilization of certain states of Africa, Asia and other barbarous regions, which makes it impracticable to exercise sovereign rights mutually and reciprocally with perfect equality of legal condition.” In much of the uncivilized world this system of capitulations incrementally escalated, to the point that it became large-scale European civilizing missions, which in turn became colonialism. Following the end of the First World War, this legal rationale contributed to the establishment of the League of Nations mandate system.

Despite criticism of them, standards of civilization remain influential tools in the practice of international affairs. Some prominent recent discussions of standards of civilization in IR and international law have focussed on proposals for appropriate standards for the late twentieth or early twenty-first centuries, ranging from human rights, democracy, economic liberalism, and globalization to modernity more generally (see Donnelly 1998 ; Franck 1992 ; Fidler 2000 ; Mozaffari 2001 ; Gong 2002 ). Much of this literature is largely uncritical of the sometimes damaging consequences of applying standards of civilization, insisting that the new missionary zeal for promoting human rights, democracy, and economic liberalism is somehow quarantined from the “fatal tainting” associated with colonial exploitation and conquest. Other studies have highlighted the dark side of standards of civilization and their role in European expansion, such as mimicking in the case of Japan ( Suzuki 2009 ), or the effects of stigmatism on foreign policy making in the case of defeated powers such as Turkey, Japan, and Russia ( Zarakol 2011 ). As these studies demonstrate, a number of ongoing legacies continue to have an impact on the conduct of international affairs.

Civilization and Progress

One of the primary reasons sociopolitics is central to considerations of civilization is evident in the following, often quoted passage from Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1985, 186):

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continual feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

One of the important lessons generally drawn from this passage is that life lived outside of society in a state of nature is constantly under threat; there is little to no chance of peace among humans without society. A related point is that some degree of sociopolitical cooperation and organization is a basic necessity for the foundation of civilization. Social and political progress is said to come prior to virtually every other form of progress; moreover, progress within the other subelements of civilization is thought to be contingent upon it. Friedrich von Schiller (1972 , 329) later posited the situation in these terms: “Would Greece have borne a Thucydides, a Plato, and an Aristotle, or Rome a Horace, a Cicero, a Virgil, and a Livy, if these two states had not risen to those heights of political achievement which in fact they attained?”

The close relationship between civilization and progress is captured by Starobinski’s (1993 , 4) observation that the “word civilization , which denotes a process, entered the history of ideas at the same time as the modern sense of the word progress . The two words were destined to maintain a most intimate relationship.” This intimate relationship is also evident in Robert Nisbet’s (1980 , 9) questioning of “whether civilization in any form and substance comparable to what we have known … in the West is possible without the supporting faith in progress that has existed along with this civilization.” He adds, “No single idea has been more important than … the idea of progress in Western civilization for nearly three thousand years.” While ideas such as liberty, justice, equality, and community have their rightful place, he insists that “throughout most of Western history, the substratum of even these ideas has been a philosophy of history that lends past, present, and future to their importance” (1980, 4). Starobinski (1993 , 33–34) makes the related point that “ civilization is a powerful stimulus to theory,” and despite its ambiguities, there is an overwhelming “temptation to clarify our thinking by elaborating a theory of civilization capable of grounding a far-reaching philosophy of history.” Clearly the twin ideals of civilization and progress are important factors in our attempts to make sense of life through the articulation of some kind of all-encompassing or at least wide-reaching philosophy of history. Indeed, in recent centuries it has proved irresistible to a diverse range of thinkers from across the political spectrum.

The relationship between civilization and progress was central to François Guizot’s analysis of Europe’s history and its civilizing processes. In an account that captures both the sociopolitical and moral demands of civilization, Guizot (1997 , 16) insisted that “the first fact comprised in the word civilization … is the fact of progress, of development; it presents at once the idea of a people marching onward, not to change its place, but to change its condition; of a people whose culture is conditioning itself, and ameliorating itself. The idea of progress, of development, appears to me the fundamental idea contained in the word, civilization. ” As for Hobbes and others, for Guizot sociopolitical progress or the harnessing of society is only part of the picture that is civilization, on the back of which, “[l]etters, sciences, the arts, display all their splendor. Wherever mankind beholds these great signs, these signs glorified by human nature, wherever it sees created these treasures of sublime enjoyment, it there recognizes and names civilization.” For Guizot (1997 , 18), “[t]wo facts” are integral to the “great fact” that is civilization: “the development of social activity, and that of individual activity; the progress of society and the progress of humanity.” Wherever these “two symptoms” are present, “mankind with loud applause proclaims civilization.”

J. B. Bury (1960 , 2–5) similarly asserts that the “idea [of progress] means that civilization has moved, is moving, and will move in a desirable direction.” In keeping with the irresistibility of promulgating a grand theory, Bury contends that the “idea of human Progress then is a theory which involves a synthesis of the past and a prophecy of the future.” This theorizing is grounded in an interpretation of history that regards the human condition as advancing “in a definite and desirable direction.” It further “implies that … a condition of general happiness will be ultimately enjoyed, which will justify the whole process of civilization.” In short, the end of history is in close proximity to a state of humankinds’ individual and social perfectibility, in which the dangers and uncertainties of the Hobbesian war of all against all are left behind in favor of the relative safety and security of civil or civilized society.

One of the things that we have increasingly been confronted with and have fought to both survive and eradicate in centuries past is the scourge of war between communities, including civilized communities. In some ways this might seem a bit at odds with the ideas of civilization, progress, and human perfectibility, but just as there is a close relationship between civilization and progress, so too there is a close relationship between civilization and war, and between war and progress.

Civilization and War

Instinct would suggest that the more civilized we have become over time, or the further we have progressed from a brutish state of nature, the more likely it is that the violent and bloody realities of armed conflict will become ever more abhorrent and objectionable and to be avoided at almost any cost. Indeed, this is one of the key lessons we take from Hobbes (1985 , 186–188; see also Lorenz 1966 ; Keeley 1997 ) about the uncertainties and brevity of life in a state of nature, in which every man is an enemy to every man, and while not necessarily constantly at war with all others, is at least prepared for it. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on the other hand, claimed that the state of nature was the playground of the noble savage, who by and large lived in a state of harmony with his fellow beings and the natural world more generally. It was only with the coming of civilization that the Garden of Eden was disturbed by war and the other ills associated with civilized modernity. As Rousseau (1997 , 161) eloquently put it, “The first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, to who it occurred to say this is mine , and found people sufficiently simple to believe him, was the true founder of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders, how many miseries and horrors” would humankind “have been spared by him who, pulling up the stakes or filling in the ditch, had cried out to his kind: Beware of listening to this impostor; [y]ou are lost if you forget that the fruits are everyone’s and the Earth no one’s.” With these vastly different perspectives in mind, having studied the origins and evolution of war among humans across two million years, Azar Gat (2006 , 663) argues that of the two, “Hobbes was much closer to the truth.”

This conclusion fits nicely with assumptions about the spread of civilization underpinning an ever more orderly and peaceful, civilized international society in which resorting to armed conflict is becoming increasingly rare. But is the association between civilization and war really a straightforward, inverse linear relationship, or is there more to it than that? The suggestion that civilization and war share a common heritage, that “the cradle of civilization is also war’s cradle,” would seem to indicate that there is something more complex going on ( Meistrich 2005 , 85). As Ira Meistrich explains (2005 , 85), “War requires the kind of mass resources and organization that only civilization can provide, and so the fertile ground from which men harvested civilization’s first fruits also nurtured the dragon-tooth seeds of warfare.” Harry Holbert Turney-High (1971 , 23) makes a similar point, that the “war complex fits with the rest of the pattern of social organization.”

As Toynbee (1951 , viii) explains, the “possibility of waging war pre-supposes a minimum of technique and organization and surplus wealth beyond what is needed for bare subsistence.” At the same time, somewhat curiously, it is thought that war making is the all-important grit around which the pearl of civilization grows and acquires its luster. Robert R. Marrett (1920 , 36) suggests that it “is a commonplace of anthropology that at a certain stage of evolution—the half-way stage, so to speak—war is a prime civilizing agency.” Quincy Wright (1965 , 98–99) draws similar conclusions: “Primitive warfare was an important factor in developing civilization. It cultivated the virtues of courage, loyalty, and obedience; it created solid groups and a method for enlarging the area of these groups, all of which were indispensable to the creation of the civilizations which followed.”

William Eckhardt (1975 , 55–62; 1992 ) similarly argues that “anthropological evidence” points to the fact “that primitive warfare was a function of human development more than human instinct or human nature.” He further suggests that it “was only after we settled down to farming and herding that the land became of importance to us and, therefore, something worth fighting for.” In much the same way that Hobbes explains the process and outcomes of socially contracted civilized society, Eckhardt (1990 , 10–11) points out how the “agricultural revolution made available a surplus of food, which carried humans beyond the subsistence level of making a living to the point where the surplus could be used to pay some to govern others, and to engage in art, religion, and writing, and to engage in war in order to expand the benefits of civilization to others, or to get others to help pay for the process of civilization, or to defend oneself from those who might be tempted to take a short cut to civilization.” This suggests a rather different relationship between civilization and war than the argument that there is a direct correlation between civilized society and a propensity for peacefulness. On the contrary, it is claimed that “the more civilized people become, the more warlike we might expect them to be” ( Eckhardt 1990 , 15).

Wright (1965 , 99) makes the further point that as “primitive society developed toward civilization, war began to take on a different character. Civilization was both an effect and a cause of warlikeness.” Eckhardt (1990 , 9) makes a similar case, “that warfare really came into its own only after the emergence of civilization some 5,000 years ago.” Following Wright, Eckhardt (1990 , 14) concludes that in essence, “war and civilization, whichever came first, promoted each other in a positive feedback loop, so that the more of one, the more of the other; and the less of one, the less of the other.” This simultaneously civilized yet vicious circle forms the basis of Eckhardt’s (1990 , 9–11) “dialectical, evolutionary theory of warfare,” in which “more developed societies engaged in more warfare.” Moreover, “civilized peoples took to war like ducks take to water, judging by their artistic and historical records,” with “wars serving as both midwives and undertakers in the rise and fall of civilizations in the course of history.”

James Boswell (1951 , 35) once wrote, “How long war will continue to be practised, we have no means of conjecturing,” adding, “Civilization, which it might have been expected would have abolished it, has only refined its savage rudeness. The irrationality remains, though we have learnt insanire certa ratione modoque , to have a method in our madness.” Indeed, rather than civilization and all its trappings representing the antidote to or the antithesis of war, it would seem that civilization and war go hand in hand; mechanized industrial civilization in particular seems to be particularly adept and efficient in the art of war making. As Eckhardt (1990 , 15) put it, “war and civilization go and grow together.” And so “far as civilization gives birth to war or, at least, promotes its use, and so far as war eventually destroys its creator or promoter, then civilization is self-destructive, a process that obstructs its own progress.” A similar point is made by Toynbee (1951 , vii–viii), who concluded that while “War may actually have been a child of Civilization,” in the long run, the child has not been particularly kind to its creator, for “War has proved to have been the proximate cause of the breakdown of every civilization which is known for certain to have broken down.” This in effect brings us full circle in the relationship between civilization and war: war making gives rise to civilization, which in turn promotes more bloody and efficient war making, which in turn brings about the demise of civilization (or civilizations).

Civilization and the Environment

Anthropomorphic climate change, its associated consequences, and the delicate state of the natural world more generally are at the forefront of the new and emerging threats to civilization ( Fagan 2004 , 2008 ). In fact, the nature of humankind’s largely exploitative relationship with the wider natural world in general is being called into question and is forcing some of us to seriously rethink that relationship. While Rousseau might have characterized the relationship between human beings and the natural world as one marked by harmony and beneficence, for most the story of civilization has in large part been about humankind’s capacity to conquer nature: conquer the wild frontier, tame the animal world, and civilize the barbaric and savage peoples of our own species. As V. Gordon Childe (1948 , 1) explains, “progress” and “scientific discoveries promised a boundless advance in man’s control over Nature.” This attitude toward nature and natural resources has long predominated in European and Western thinking in particular. John Locke (1965 , 339/II:42), for instance, in his discussion of the Americas, Amerindians, and property rights, wrote, “Land that is left wholly to Nature, that hath no improvement of Pasturage, Tillage, or Planting, is called, as indeed it is, wast [waste].” The land was there to be improved and exploited in order to accommodate a greater number of people than the Amerindians were inclined to, and if they were not going to make appropriate use of it, then the British were entitled to take it—in fact, it was their duty to do so.

As outlined above in relation to progress, a significant aspect of civilization revolves around evolving or developing, whether from a state of nature, savagery, or barbarism, toward urbanized, scientific, technological civilization. A large part of this evolutionary process concerns society’s capacity to control nature and exploit its resources. This is illustrated by Adam Smith (1869 , 289–296) when he outlines four distinct stages of human social development: the first is “nations of hunters, the lowest and rudest state of society,” his prime example being the “native tribes of North America.” The second stage is “nations of shepherds, a more advanced state of society,” such as that of the Tatars and the Arabs. But such peoples still have “no fixed habitation” for any significant length of time, as they move about on the “whim” of their livestock and with the seasons in the endless search for feed. The third stage is that of agriculture, which “even in its rudest and lowest state, supposes a settlement [and] some sort of fixed habitation.” The fourth and most advanced stage is that of civilized, urbanized, commercial society, an efficient and effective exploiter of nature and all the fruits it has to offer. Similarly, Walter Bagehot (1875 , 17–19) argued that the “miscellaneous races of the world be justly described as being upon various edges of industrial civilization, approaching it by various sides, and falling short of it in various particulars.” The problem with those falling short, the uncivilized who were supposedly ruled by nature as opposed to rulers of it, was that they “neither knew nature, which is the clock-work of material civilization, nor possessed a polity, which is a kind of clock-work to moral civilization.”

In some ways, the relationship between civilization and nature is not so different from the dialectical relationship between civilization and war: the higher the level of civilization, the greater the exploitation of nature; the greater the exploitation of nature, the more civilization progresses. But as with civilization and war, this relationship cannot go on forever: natural resource extraction and exploitation is not a bottomless pit, but rather is finite and can only support so many people for so long. And of course as our planet is telling us, there are severe consequences associated with the processes of civilization, modernization, urbanization, and all that goes with them. The cycle of extracting more stuff from the ground, processing more stuff, building more stuff, producing more stuff, owning more stuff, throwing away more stuff, and buying more new stuff to replace it is proving unsustainable on such a large scale. The consequences of such excess, in the forms of environmental degradation and climate change, are many and varied; they include melting polar ice caps and rising sea levels, variations in air and sea temperatures, extended periods of drought in some parts of the world while others experience increased rainfall and flooding, and increasing frequency of extreme weather phenomena, to name just a few.

These environmental changes in turn impact our capacity to continue to inhabit certain parts of Earth and our abilityto continue to utilize and exploit resources as we have done for centuries. A knock-on effect is that these diverse changes and threats are often interrelated; one realm of security or insecurity can have a direct and dramatic impact on another, generating a kind of vicious cycle of insecurity. For instance, scarcity of and competition for essential resources such as land, food, water, and energy are potential catalysts for violent conflict ( Dyer 2008 ; Mazo 2010 ; Homer-Dixon 2001 ; Pumphrey 2008 ). And these are not just imaginary scenarios; the period 2007–2008 witnessed violent food riots in as many as thirty countries around the globe, some of them developed Western nations. If the dire predictions are correct, then this is just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

Rethinking Civilization

Just over a couple of hundred years ago, Edward Gibbon (1963 , 530) wrote that humankind may “acquiesce in the pleasing conclusion that every age of the world has increased and still increases the real wealth, the happiness, the knowledge, and perhaps the virtue, of the human race.” In many ways, the record of human history bears this out: for example, the life expectancy of a Roman during the days of the empire was around twenty-five years. Today the world average life expectancy is somewhere in the mid- to late sixties, and life expectancy is considerably higher in many parts of the world. Thanks in part to advances in science and technology, in the twentieth century alone, the “average national gain in life expectancy at birth [was] 66% for males and 71% for females, and in some cases, life expectancy … more than doubled” during the course of the century ( Kinsell 1992 ; Galor and Moav 2005 ). The twentieth century also witnessed unprecedented urbanization, a key marker of progress and development, with an increase from 220 million urban dwellers, or around 13% of the world’s population, at the beginning of the century to 732 million or 29% by mid-century and reaching around 3.2 billion people or 49% in 2005. With urbanization expected to continue apace, it is estimated that by 2030 almost 5 billion people will live in cities, equivalent to roughly 60% of the global population ( United Nations 2005 ).

In respect to the global economy, it has been calculated that in the past millennium, during which the global population increased some twenty-two-fold, global per capita income rose by approximately thirteen times, while global GDP expanded by a factor of almost 300. The vast majority of this growth can be attributed to advances made as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution; since 1820 the global population has grown by a factor of five, while per capita income has increased approximately eight-fold. This kind of development far outstrips the preceding millennium, when Earth’s population is estimated to have grown by as little as one-sixth, and during which time per capita income was largely stagnant ( Maddison 2006 ).

It might seem then that civilization is chugging along quite nicely, just as so many have imagined it; we live longer than our predecessors, we are better educated than ever before, and we have access to far more stuff than most of us will ever need. But at what cost have this civilization and progress come to us and our planet? The distinguished scientist, the late Frank Fenner—the man who announced to the world in 1980 that smallpox had been eradicated—recently stated that he is convinced that “ Homo sapiens will become extinct, perhaps within 100 years.” Like others, he argues that Earth has entered the Anthropocene, and while “climate change is just at the very beginning … we’re seeing remarkable changes in the weather already.” It is on this basis that he argues that humankind will collectively “undergo the same fate as the people of Easter Island.” The only things that will be left of us are our monuments to the excesses of a fallen civilization. Before then, as Earth’s “population keeps growing to seven, eight, or nine billion, there will be a lot more wars over food.” And not only are humans doomed, so are a “lot of other animals … too. It’s an irreversible situation” (Fenner in Jones 2010 ; Boulter 2002 ).

It is difficult to believe that the human condition is really that perilous, that the thin ice of civilization is melting away so quickly and so dramatically that its future is at risk. Are we really lurching toward some sort of post-apocalyptic world like that depicted in Mad Max or The Road ? While climate change skeptics might beg to differ, at the very least, all is not well in the world of civilization. I suggest that a good part of the problem may well be the very way in which we conceive of civilization and progress, which for so long now has been predominantly all about the social, political, and material dimensions of civilization at the expense of its ethical and other-regarding dimensions. In considering human progress, Ruth Macklin (1977 , 370) is slightly at odds with Gibbon in her claim that it “is wholly uncontroversial to hold that technological progress has taken place; largely uncontroversial to claim that intellectual and theoretical progress has occurred; somewhat controversial to say aesthetic or artistic progress has taken place; and highly controversial to assert that moral progress has occurred.”

The question of moral progress appears to be at the heart of the major challenges to civilization outlined above. In respect to both the relationship between civilization and war and that between civilization and the environment, we can see two potentially self-destructive processes in which civilization brings about its own demise as it cannibalizes itself in a kind of suicidal life cycle. The relationship between civilization and war is seemingly one in which war making gives rise to civilization, the organizational and technological advances of which in turn promote yet more bloody and efficient war making, which in turn eventually brings about the demise of civilization either through overstretch or internal collapse. Similarly, up to this point in human history, the march of civilization has largely been at the expense of the environment and the natural world more generally. And now, in turn, the environment is threatening the future of civilization through the potentially catastrophic consequences of climate change. In both cases this represents a sort of vicious circle in which civilization is ultimately its own worst enemy. On top of this are the less than savory things done in the name of civilization; for centuries civilization has proven to be hell bent on expunging that which is not civilized, or that which is deemed a threat to civilization. The consequences range from European conquest and colonization to the global war on terror.

The Nobel Peace Laureate of 1952, Albert Schweitzer , offers a different take on civilization that owes more to moral and ethical considerations than to sociopolitical and material concerns. He writes (1947, viii), “Civilization, put quite simply, consists in our giving ourselves, as human beings, to the effort to attain the perfecting of the human race and the actualization of progress of every sort in the circumstances of humanity and of the objective world.” This giving of ourselves is as much an attitude or frame of mind as it is a political, material, or cultural expression of civilization, for it necessarily “involves a double disposition: firstly, we must be prepared to act affirmatively toward the world and life; secondly, we must become ethical.” For Schweitzer (1967 , 20), the “essential nature of civilization does not lie in its material achievements, but in the fact that individuals keep in mind the ideals of the perfecting of man, and the improvement of the social and political conditions of peoples, and of mankind as a whole.” And as he put it slightly differently (1947, ix), “Civilization originates when men become inspired by a strong and clear determination to attain progress, and consecrate themselves, as a result of this determination, to the service of life and the world.” This call for service to life and the world is at the heart of Schweitzer’s philosophy of civilization, which in effect is also his account of ethics; it is what he referred to as the idea of Reverence for Life ( Ehrfurcht vor dem Leben ), which requires of us a “world-view” that is other-regarding and extends a right to life and an ethic of “responsibility without limits towards all that lives” (1967, 215; Cicovacki 2007 ). In the age of the “selfie” and the self-obsession that goes with it, perhaps this is too much to ask, but that should not and need not be the case.

Alexander, J. C. 2013 . The Dark Side of Modernity . Cambridge, UK, and Malden, MA: Polity.

Google Scholar

Google Preview