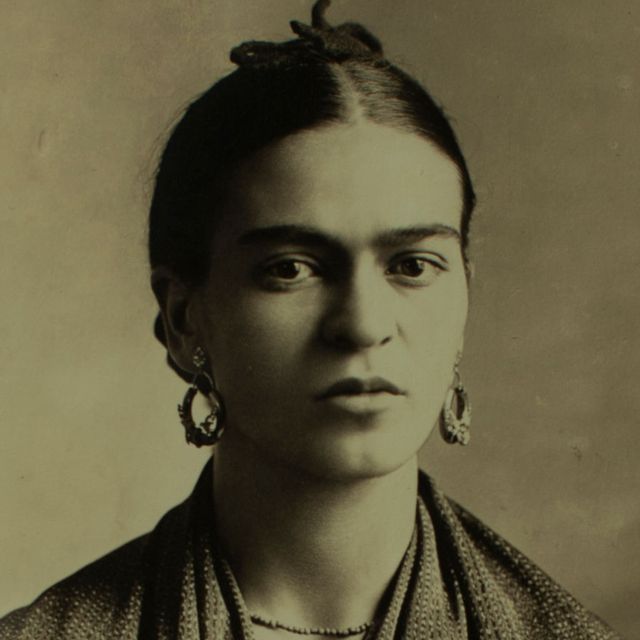

Frida Kahlo

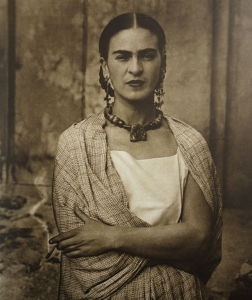

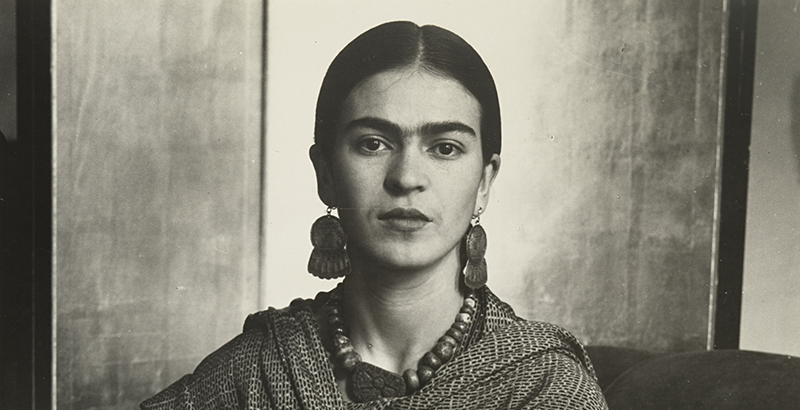

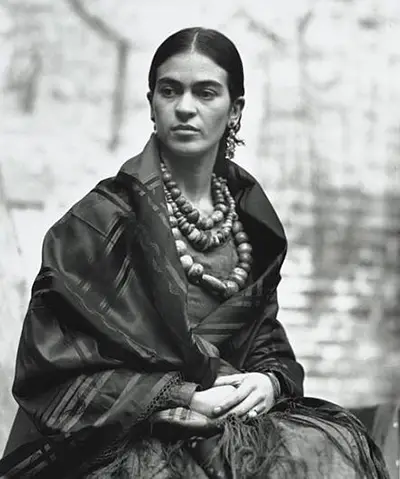

Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

(1907-1954)

Who Was Frida Kahlo?

Artist Frida Kahlo was considered one of Mexico's greatest artists who began painting mostly self-portraits after she was severely injured in a bus accident. Kahlo later became politically active and married fellow communist artist Diego Rivera in 1929. She exhibited her paintings in Paris and Mexico before her death in 1954.

Family, Education and Early Life

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico.

Kahlo's father, Wilhelm (also called Guillermo), was a German photographer who had immigrated to Mexico where he met and married her mother Matilde. She had two older sisters, Matilde and Adriana, and her younger sister, Cristina, was born the year after Kahlo.

Around the age of six, Kahlo contracted polio, which caused her to be bedridden for nine months. While she recovered from the illness, she limped when she walked because the disease had damaged her right leg and foot. Her father encouraged her to play soccer, go swimming, and even wrestle — highly unusual moves for a girl at the time — to help aid in her recovery.

In 1922, Kahlo enrolled at the renowned National Preparatory School. She was one of the few female students to attend the school, and she became known for her jovial spirit and her love of colorful, traditional clothes and jewelry.

While at school, Kahlo hung out with a group of politically and intellectually like-minded students. Becoming more politically active, Kahlo joined the Young Communist League and the Mexican Communist Party.

Frida Kahlo's Accident

After staying at the Red Cross Hospital in Mexico City for several weeks, Kahlo returned home to recuperate further. She began painting during her recovery and finished her first self-portrait the following year, which she gave to Gómez Arias.

Frida Kahlo's Marriage to Diego Rivera

In 1929, Kahlo and famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera married. Kahlo and Rivera first met in 1922 when he went to work on a project at her high school. Kahlo often watched as Rivera created a mural called The Creation in the school’s lecture hall. According to some reports, she told a friend that she would someday have Rivera’s baby.

Kahlo reconnected with Rivera in 1928. He encouraged her artwork, and the two began a relationship. During their early years together, Kahlo often followed Rivera based on where the commissions that Rivera received were. In 1930, they lived in San Francisco, California. They then went to New York City for Rivera’s show at the Museum of Modern Art and later moved to Detroit for Rivera’s commission with the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kahlo and Rivera’s time in New York City in 1933 was surrounded by controversy. Commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller , Rivera created a mural entitled Man at the Crossroads in the RCA Building at Rockefeller Center. Rockefeller halted the work on the project after Rivera included a portrait of communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the mural, which was later painted over. Months after this incident, the couple returned to Mexico and went to live in San Angel, Mexico.

Never a traditional union, Kahlo and Rivera kept separate, but adjoining homes and studios in San Angel. She was saddened by his many infidelities, including an affair with her sister Cristina. In response to this familial betrayal, Kahlo cut off most of her trademark long dark hair. Desperately wanting to have a child, she again experienced heartbreak when she miscarried in 1934.

Kahlo and Rivera went through periods of separation, but they joined together to help exiled Soviet communist Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia in 1937. The Trotskys came to stay with them at the Blue House (Kahlo's childhood home) for a time in 1937 as Trotsky had received asylum in Mexico. Once a rival of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin , Trotsky feared that he would be assassinated by his old nemesis. Kahlo and Trotsky reportedly had a brief affair during this time.

Kahlo divorced Rivera in 1939. They did not stay divorced for long, remarrying in 1940. The couple continued to lead largely separate lives, both becoming involved with other people over the years .

Artistic Career

While she never considered herself a surrealist, Kahlo befriended one of the primary figures in that artistic and literary movement, Andre Breton, in 1938. That same year, she had a major exhibition at a New York City gallery, selling about half of the 25 paintings shown there. Kahlo also received two commissions, including one from famed magazine editor Clare Boothe Luce, as a result of the show.

In 1939, Kahlo went to live in Paris for a time. There she exhibited some of her paintings and developed friendships with such artists as Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso .

Kahlo received a commission from the Mexican government for five portraits of important Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to finish the project. She lost her beloved father that year and continued to suffer from chronic health problems. Despite her personal challenges, her work continued to grow in popularity and was included in numerous group shows around this time.

In 1953, Kahlo received her first solo exhibition in Mexico. While bedridden at the time, Kahlo did not miss out on the exhibition’s opening. Arriving by ambulance, Kahlo spent the evening talking and celebrating with the event’s attendees from the comfort of a four-poster bed set up in the gallery just for her.

After Kahlo’s death, the feminist movement of the 1970s led to renewed interest in her life and work, as Kahlo was viewed by many as an icon of female creativity.

Frida Kahlo's Most Famous Paintings

Many of Kahlo’s works were self-portraits. A few of her most notable paintings include:

'Frieda and Diego Rivera' (1931)

Kahlo showed this painting at the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists, the city where she was living with Rivera at the time. In the work, painted two years after the couple married, Kahlo lightly holds Rivera’s hand as he grasps a palette and paintbrushes with the other — a stiffly formal pose hinting at the couple’s future tumultuous relationship. The work now lives at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

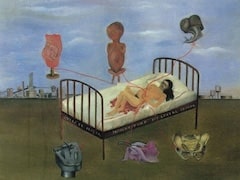

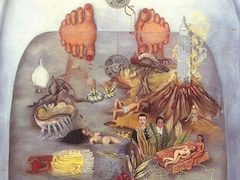

'Henry Ford Hospital' (1932)

In 1932, Kahlo incorporated graphic and surrealistic elements in her work. In this painting, a naked Kahlo appears on a hospital bed with several items — a fetus, a snail, a flower, a pelvis and others — floating around her and connected to her by red, veinlike strings. As with her earlier self-portraits, the work was deeply personal, telling the story of her second miscarriage.

'The Suicide of Dorothy Hale' (1939)

Kahlo was asked to paint a portrait of Luce and Kahlo's mutual friend, actress Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide earlier that year by jumping from a high-rise building. The painting was intended as a gift for Hale's grieving mother. Rather than a traditional portrait, however, Kahlo painted the story of Hale's tragic leap. While the work has been heralded by critics, its patron was horrified at the finished painting.

'The Two Fridas' (1939)

One of Kahlo’s most famous works, the painting shows two versions of the artist sitting side by side, with both of their hearts exposed. One Frida is dressed nearly all in white and has a damaged heart and spots of blood on her clothing. The other wears bold colored clothing and has an intact heart. These figures are believed to represent “unloved” and “loved” versions of Kahlo.

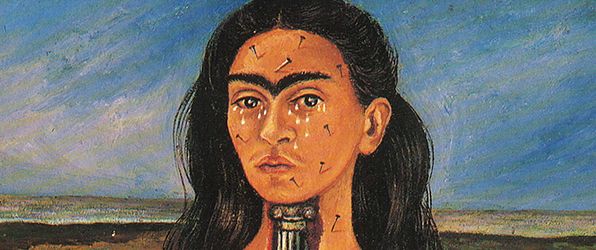

'The Broken Column' (1944)

Kahlo shared her physical challenges through her art again with this painting, which depicted a nearly nude Kahlo split down the middle, revealing her spine as a shattered decorative column. She also wears a surgical brace and her skin is studded with tacks or nails. Around this time, Kahlo had several surgeries and wore special corsets to try to fix her back. She would continue to seek a variety of treatments for her chronic physical pain with little success.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S FRIDA KAHLO FACT CARD

Frida Kahlo’s Death

About a week after her 47th birthday, Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, at her beloved Blue House. There has been some speculation regarding the nature of her death. It was reported to be caused by a pulmonary embolism, but there have also been stories about a possible suicide.

Kahlo’s health issues became nearly all-consuming in 1950. After being diagnosed with gangrene in her right foot, Kahlo spent nine months in the hospital and had several operations during this time. She continued to paint and support political causes despite having limited mobility. In 1953, part of Kahlo’s right leg was amputated to stop the spread of gangrene.

Deeply depressed, Kahlo was hospitalized again in April 1954 because of poor health, or, as some reports indicated, a suicide attempt. She returned to the hospital two months later with bronchial pneumonia. No matter her physical condition, Kahlo did not let that stand in the way of her political activism. Her final public appearance was a demonstration against the U.S.-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala on July 2nd.

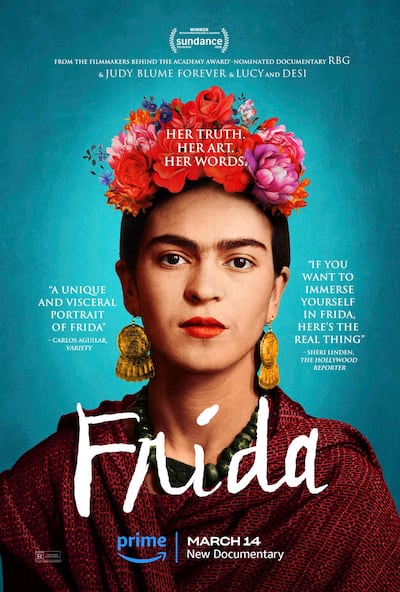

Movie on Frida Kahlo

Kahlo’s life was the subject of a 2002 film entitled Frida , starring Salma Hayek as the artist and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Directed by Julie Taymor, the film was nominated for six Academy Awards and won for Best Makeup and Original Score.

Frida Kahlo Museum

The family home where Kahlo was born and grew up, later referred to as the Blue House or Casa Azul, was opened as a museum in 1958. Located in Coyoacán, Mexico City, the Museo Frida Kahlo houses artifacts from the artist along with important works including Viva la Vida (1954), Frida and Caesarean (1931) and Portrait of my father Wilhelm Kahlo (1952).

Book on Frida Kahlo

Hayden Herrera’s 1983 book on Kahlo, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo , helped to stir up interest in the artist. The biographical work covers Kahlo’s childhood, accident, artistic career, marriage to Diego Rivera, association with the communist party and love affairs.

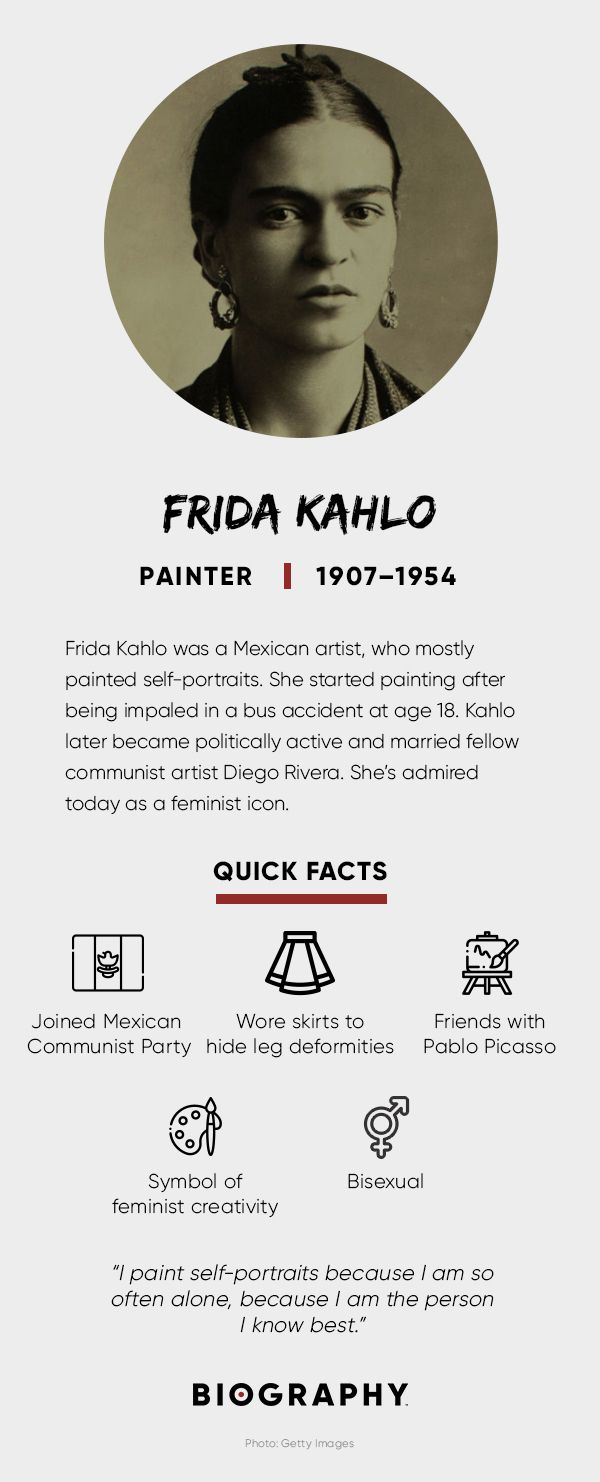

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Frida Kahlo

- Birth Year: 1907

- Birth date: July 6, 1907

- Birth City: Mexico City

- Birth Country: Mexico

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Painter Frida Kahlo was a Mexican artist who was married to Diego Rivera and is still admired as a feminist icon.

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- National Preparatory School

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Frida Kahlo met Diego Rivera when he was commissioned to paint a mural at her high school.

- Kahlo dealt with chronic pain most of her life due to a bus accident.

- Death Year: 1954

- Death date: July 13, 1954

- Death City: Mexico City

- Death Country: Mexico

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Frida Kahlo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/frida-kahlo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.

- My painting carries with it the message of pain.

- I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.

- I think that, little by little, I'll be able to solve my problems and survive.

- The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to, and I paint whatever passes through my head without any other consideration.

- I was born a bitch. I was born a painter.

- I love you more than my own skin.

- I am not sick, I am broken, but I am happy as long as I can paint.

- Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?

- I tried to drown my sorrows, but the bastards learned how to swim, and now I am overwhelmed with this decent and good feeling.

- There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.

- I hope the end is joyful, and I hope never to return.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Famous Painters

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Andy Warhol

Frida Kahlo

Mexican Painter

Summary of Frida Kahlo

Small pins pierce Kahlo's skin to reveal that she still 'hurts' following illness and accident, whilst a signature tear signifies her ongoing battle with the related psychological overflow. Frida Kahlo typically uses the visual symbolism of physical pain in a long-standing attempt to better understand emotional suffering. Prior to Kahlo's efforts, the language of loss, death, and selfhood, had been relatively well investigated by some male artists (including Albrecht Dürer , Francisco Goya , and Edvard Munch ), but had not yet been significantly dissected by a woman. Indeed not only did Kahlo enter into an existing language, but she also expanded it and made it her own. By literally exposing interior organs, and depicting her own body in a bleeding and broken state, Kahlo opened up our insides to help explain human behaviors on the outside. She gathered together motifs that would repeat throughout her career, including ribbons, hair, and personal animals, and in turn created a new and articulate means to discuss the most complex aspects of female identity. As not only a 'great artist' but also a figure worthy of our devotion, Kahlo's iconic face provides everlasting trauma support and she has influence that cannot be underestimated.

Accomplishments

- Kahlo made it legitimate for women to outwardly display their pains and frustrations and to thus make steps towards understanding them. It became crucial for women artists to have a female role model and this is the gift of Frida Kahlo.

- As an important question for many Surrealists , Kahlo too considers: What is Woman? Following repeated miscarriages, she asks: to what extent does motherhood or its absence impact on female identity? She irreversibly alters the meaning of maternal subjectivity. It becomes clear through umbilical symbolism (often shown by ribbons) that Kahlo is connected to all that surrounds her, and that she is a 'mother' without children.

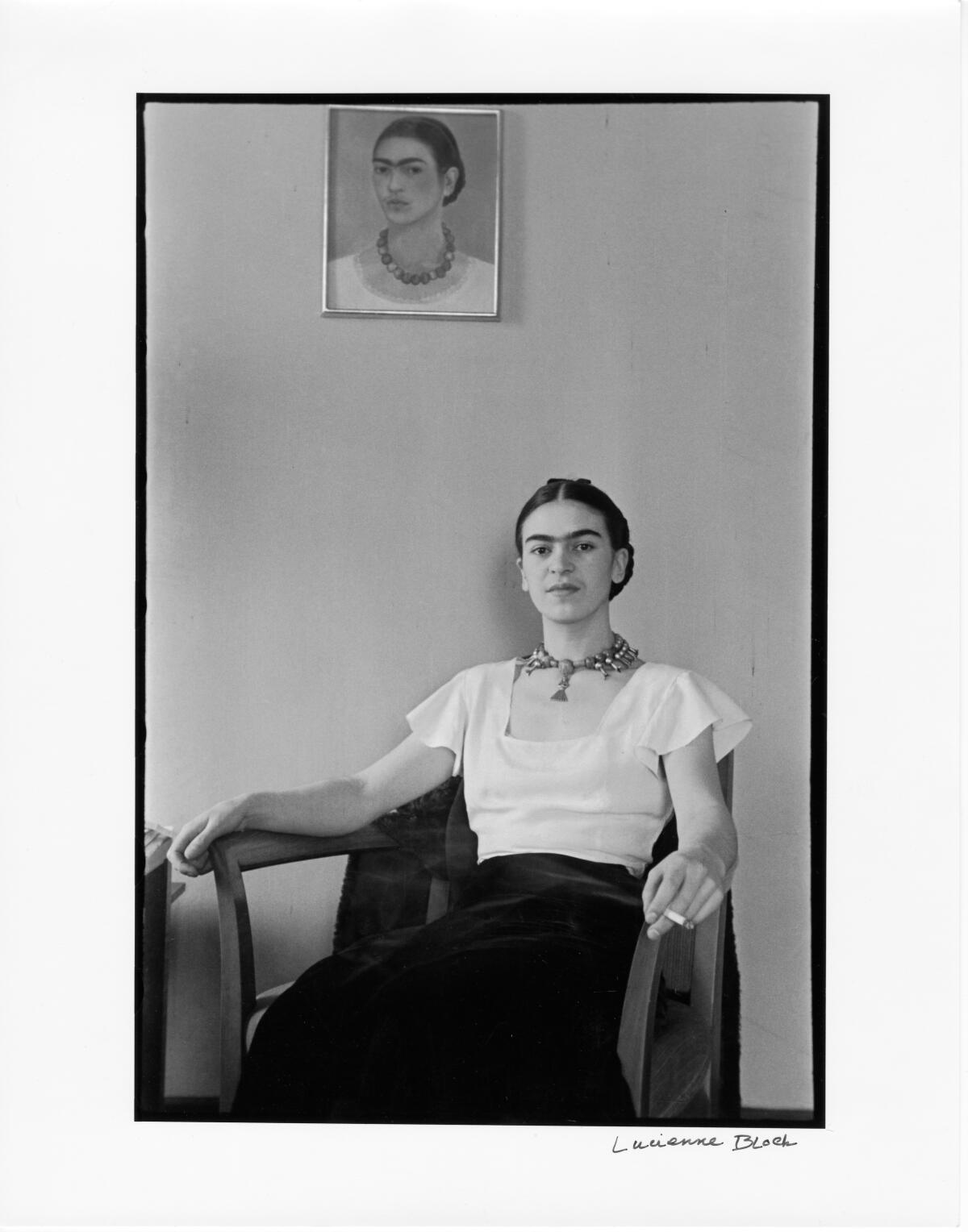

- Finding herself often alone, she worked obsessively with self-portraiture. Her reflection fueled an unflinching interest in identity. She was particularly interested in her mixed German-Mexican ancestry, as well as in her divided roles as artist, lover, and wife.

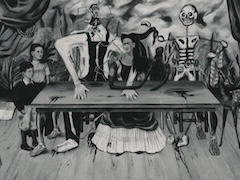

- Kahlo uses religious symbolism throughout her oeuvre . She appears as the Madonna holding her 'animal babies', and becomes the Virgin Mary as she cradles her husband and famous national painter Diego Rivera . She identifies with Saint Sebastian, and even fittingly appears as the martyred Christ. She positions herself as a prophet when she takes to the head of the table in her Last Supper -style painting, and her depiction of the accident which left her impaled on a metal bar (and covered in gold dust when lying injured) recalls the crucifixion and suggests her own holiness.

- Women prior to Kahlo who had attempted to communicate the wildest and deepest of emotions were often labeled hysterical or condemned insane - while men were aligned with the 'melancholy' character type. By remaining artistically active under the weight of sadness, Kahlo revealed that women too can be melancholy rather than depressed, and that these terms should not be thought of as gendered.

The Life of Frida Kahlo

"I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone... because I am the subject I know best." From battles with her mind and her body, Kahlo lived through her art.

Important Art by Frida Kahlo

Frieda and Diego Rivera

It is as if in this painting Kahlo tries on the role of wife to see how it fits. She does not focus on her identity as a painter, but instead adopts a passive and supportive role, holding the hand of her talented and acclaimed husband. It was indeed the case that during the majority of her painting career, Kahlo was viewed only in Rivera's shadow and it was not until later in life that she gained international recognition. This early double-portrait was painted primarily to mark the celebration of Kahlo's marriage to Rivera. Whilst Rivera holds a palette and paint brushes, symbolic of his artistic mastery, Kahlo limits her role to his wife by presenting herself slight in frame and without her artistic accoutrements. Kahlo furthermore dresses in costume typical of the Mexican woman, or "La Mexicana," wearing a traditional red shawl known as the rebozo and jade Aztec beads. The positioning of the figures echoes that of traditional marital portraiture where the wife is placed on her husband's left to indicate her lesser moral status as a woman. In a drawing made the following year called Frida and the Miscarriage , the artist does hold her own palette, as though the experience of losing a fetus and not being able to create a baby shifts her determination wholly to the creation of art.

Oil on canvas - San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Henry Ford Hospital

Many of Kahlo's paintings from the early 1930s, especially in size, format, architectural setting and spatial arrangement, relate to religious ex-voto paintings of which she and Rivera possessed a large collection ranging in date over several centuries. Ex-votos are made as a gesture of gratitude for salvation, a granted prayer or disaster averted and left in churches or at shrines. Ex-votos are generally painted on small-scale metal panels and depict the incident along with the Virgin or saint to whom they are offered. Henry Ford Hospital , is a good example where the artist uses the ex-voto format but subverts it by placing herself centre stage, rather than recording the miraculous deeds of saints. Kahlo instead paints her own story, as though she becomes saintly and the work is made not as thanks to the lord but in defiance, questioning why he brings her pain. In this painting, Kahlo lies on a bed, bleeding after a miscarriage. From the exposed naked body six vein-like ribbons flow outwards, attached to symbols. One of these six objects is a fetus, suggesting that the ribbons could be a metaphor for umbilical cords. The other five objects that surround Frida are things that she remembers, or things that she had seen in the hospital. For example, the snail makes reference to the time it took for the miscarriage to be over, whilst the flower was an actual physical object given to her by Diego. The artist demonstrates her need to be attached to all that surrounds her: to the mundane and metaphorical as much as the physical and actual. Perhaps it is through this reaching out of connectivity that the artist tries to be 'maternal', even though she is not able to have her own child.

Oil on canvas - Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City, Mexico

This is a haunting painting in which both the birth giver and the birthed child seem dead. The head of the woman giving birth is shrouded in white cloth while the baby emerging from the womb appears lifeless. At the time that Kahlo painted this work, her mother had just died so it seems reasonable to assume that the shrouded funerary figure is her mother while the baby is Kahlo herself (the title supports this reading). However, Kahlo had also just lost her own child and has said that she is the covered mother figure. The Virgin of Sorrows , who hangs above the bed suggests that this is an image that overflows with maternal pain and suffering. Also though, and revealingly, Kahlo wrote in her diary, next to several small drawings of herself, 'the one who gave birth to herself ... who wrote the most wonderful poem of her life.' Similar to the drawing, Frida and the Miscarriage , My Birth represents Kahlo mourning for the loss of a child, but also finding the strength to make powerful art because of such trauma. The painting is made in a retablo (or votive) style (a small traditional Mexican painting derived from Catholic Church art) in which thanks would typically be given to the Madonna beneath the image. Kahlo instead leaves this section blank, as though she finds herself unable to give thanks either for her own birth, or for the fact that she is now unable to give birth. The painting seems to bring the message that it is important to acknowledge that birth and death live very closely together. Many believe that My Birth was heavily inspired by an Aztec sculpture that Kahlo had at home representing Tiazolteotl, the Goddess of fertility and midwives.

Oil and tempera on zinc - Private Collection

My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree)

This dream-like family tree was painted on zinc rather than canvas, a choice that further highlights the artist's fascination with and collection of 18 th -century and 19 th -century Mexican retablos. Kahlo completed this work to accentuate both her European Jewish heritage and her Mexican background. Her paternal side, German Jewish, occupies the right side of the composition symbolized by the sea (acknowledging her father's voyage to get to Mexico), while her maternal side of Mexican descent is represented on the left by a map faintly outlining the topography of Mexico. While Kahlo's paintings are assertively autobiographical, she often used them to communicate transgressive or political messages: this painting was completed shortly after Adolf Hitler passed the Nuremberg laws banning interracial marriage. Here, Kahlo simultaneously affirms her mixed heritage to confront Nazi ideology, using a format - the genealogical chart - employed by the Nazi party to determine racial purity. Beyond politics, the red ribbon used to link the family members echoes the umbilical cord that connects baby Kahlo to her mother - a motif that recurs throughout Kahlo's oeuvre .

Oil and tempera on zinc - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

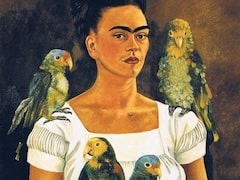

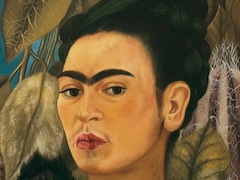

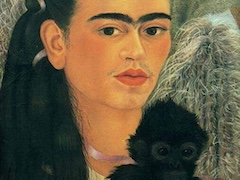

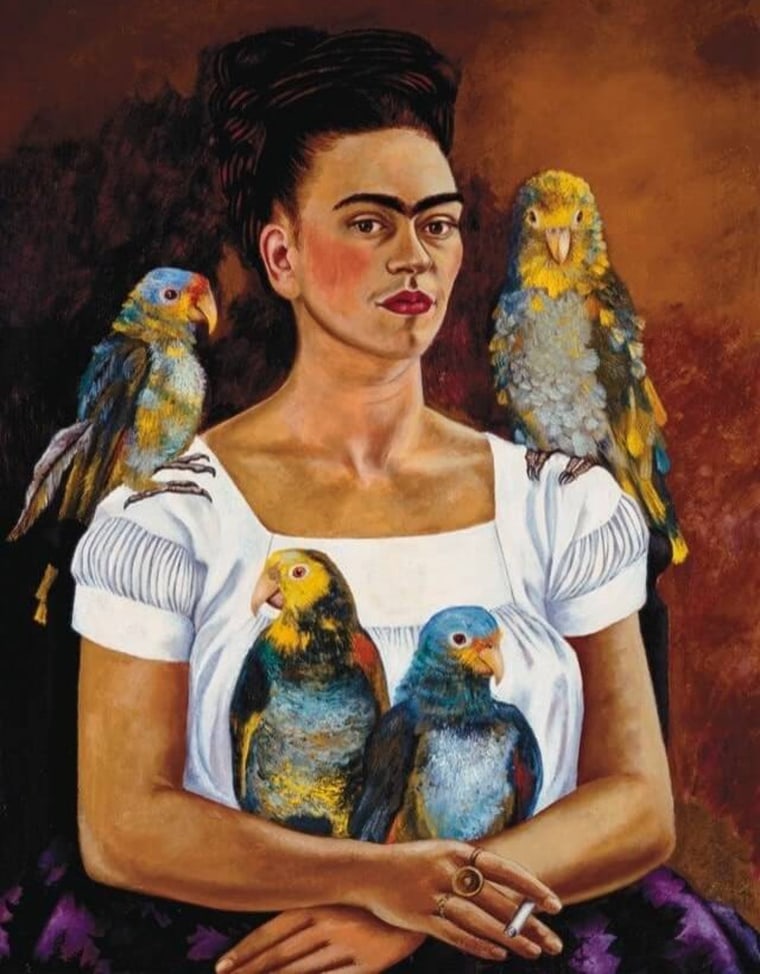

Fulang-Chang and I

This painting debuted at Kahlo's exhibition in Julien Levy's New York gallery in 1938, and was one of the works that most fascinated André Breton, the founder of Surrealism. The canvas in the New York show is a self-portrait of the artist and her spider monkey, Fulang-Chang, a symbol employed as a surrogate for the children that she and Rivera could not have. The arrangement of figures in the portrait signals the artist's interest in Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and child. After the New York exhibition, a second frame containing a mirror was added. The later inclusion of the mirror is a gesture inviting the viewer into the work: it was through looking at herself intensely in a mirror in her months spent at home after her bus accident that Kahlo first began painting portraits and delving deeper into her psyche. The inclusion of the mirror, considered from this perspective, is a remarkably intimate vision into both the artist's aesthetic process and into her personal introspection. In many of Kahlo's self-portraits, she is accompanied by monkeys, dogs, and parrots, all of which she kept as pets. Since the Middle Ages, small spider monkeys, like those kept by Kahlo, have been said to symbolize the devil, heresy, and paganism, finally coming to represent the fall of man, vice, and the embodiment of lust. These monkeys were depicted in the past as a cautionary symbol against the dangers of excessive love and the base instincts of man. Kahlo again depicts herself with her monkey in both 1939 and 1940. In a later version in 1945, Kahlo paints her monkey and also her dog, Xolotl. This little dog that often accompanies the artist, is named after a mythological Aztec god, known to represent lightning and death, and also to be the twin of Quetzalcoatl, both of who had visited the underworld. All of these pictures, including Fulang-Chang and I include 'umbilical' ribbons that wrap between Kahlo's and the animal's necks. Kahlo is the Madonna and her pets become the holy (yet darkly symbolic) infant for which she longs.

In two parts, oil on composition board (1937) with painted mirror frame (added after 1939) - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

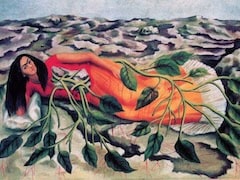

What the Water Gave Me

In this painting most of Kahlo's body is obscured from view. We are unusually confronted with the foot and plug end of the bath, and with focus placed on the artist's feet. Furthermore, Kahlo adopts a birds-eye view and looks down on the water from above. Within the water, Kahlo paints an alternative self-portrait, one in which the more traditional facial portrait has been replaced by an array of symbols and recurring motifs. The artist includes portraits of her parents, a traditional Tehuana dress, a perforated shell, a dead humming bird, two female lovers, a skeleton, a crumbling skyscraper, a ship set sail, and a woman drowning. This painting was featured in Breton's 1938 book on Surrealism and Painting and Hayden Herrera, in her biography of Kahlo, mentions that the artist herself considered this work to have a special importance. Recalling the tapestry style painting of Northern Renaissance masters, Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the figures and objects floating in the water of Kahlo's painting create an at once fantastic and real landscape of memory. Kahlo discussed What the Water Gave Me with the Manhattan gallery owner Julien Levy, and suggested that it was a sad piece that mourned the loss of her childhood. Perhaps the strangled figure at the centre is representative of the inner emotional torments experienced by Kahlo herself. It is clear from the conversation that the artist had with Levy, that Kahlo was aware of the philosophical implications of her work. In an interview with Herrera, Levy recalls, in 'a long philosophical discourse, Kahlo talked about the perspective of herself that is shown in this painting'. He further relays that 'her idea was about the image of yourself that you have because you do not see your head. The head is something that is looking, but is not seen. It is what one carries around to look at life with.' The artist's head in What the Water Gave Me is thus appropriately replaced by the interior thoughts that occupy her mind. As well as an inclusion of death by strangulation in the centre of the water, there is also a labia-like flower and a cluster of pubic hair painted between Kahlo's legs. The work is quite sexual while also showing preoccupation with destruction and death. The motif of the bathtub in art is one that has been popular since Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Marat (1793), and was later taken up many different personalities such as Francesca Woodman and Tracey Emin.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

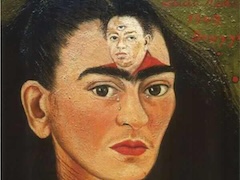

The Two Fridas

This double self-portrait is one of Kahlo's most recognized compositions, and is symbolic of the artist's emotional pain experienced during her divorce from Rivera. On the left, the artist is shown in modern European attire, wearing the costume from her marriage to Rivera. Throughout their marriage, given Rivera's strong nationalism, Kahlo became increasingly interested in indigenism and began to explore traditional Mexican costume, which she wears in the portrait on the right. It is the Mexican Kahlo that holds a locket with an image of Rivera. The stormy sky in the background, and the artist's bleeding heart - a fundamental symbol of Catholicism and also symbolic of Aztec ritual sacrifice - accentuate Kahlo's personal tribulation and physical pain. Symbolic elements frequently possess multiple layers of meaning in Kahlo's pictures; the recurrent theme of blood represents both metaphysical and physical suffering, gesturing also to the artist's ambivalent attitude toward accepted notions of womanhood and fertility. Although both women have their hearts exposed, the woman in the white European outfit also seems to have had her heart dissected and the artery that runs from this heart is cut and bleeding. The artery that runs from the heart of her Tehuana-costumed self remains intact because it is connected to the miniature photograph of Diego as a child. Whereas Kahlo's heart in the Mexican dress remains sustained, the European Kahlo, disconnected from her beloved Diego, bleeds profusely onto her dress. As well as being one of the artist's most famous works, this is also her largest canvas.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Modern Art, Mexico City, Mexico

Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair

This self-portrait shows Kahlo as an androgynous figure. Scholars have seen this gesture as a confrontational response to Rivera's demand for a divorce, revealing the artist's injured sense of female pride and her self-punishment for the failures of her marriage. Her masculine attire also reminds the viewer of early family photographs in which Kahlo chose to wear a suit. The cropped hair also presents a nuanced expression of the artist's identity. She holds one cut braid in her left hand while many strands of hair lie scattered on the floor. The act of cutting a braid symbolizes a rejection of girlhood and innocence, but equally can be seen as the severance of a connective cord (maybe umbilical) that binds two people or two ways of life. Either way, braids were a central element in Kahlo's identity as the traditional La Mexicana , and in the act of cutting off her braids, she rejects some aspect of her former identity. The hair strewn about the floor echoes an earlier self-portrait painted as the Mexican folkloric figure La Llorona , here ridding herself of these female attributes. Kahlo clutches a pair of scissors, as the discarded strands of hair become animated around her feet; the tresses appear to have a life of their own as they curl across the floor and around the legs of her chair. Above her sorrowful scene, Kahlo inscribed the lyrics and music of a song that declares cruelly, "Look, if I loved you it was for your hair, now that you are hairless, I don't love you anymore," confirming Kahlo's own denunciation and rejection of her female roles. In likely homage to Kahlo's painting, Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus photographed Wedding Portraits in 1997. On the occasion of her marriage, Brotherus cuts her hair, the remains of which her new husband holds in his hands. The act of cutting one's hair symbolic of a moment of change happens in the work of other female artists too, including that of Francesca Woodman and Rebecca Horn.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

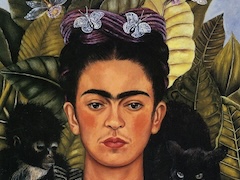

Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird

The frontal position and outward stare of Kahlo in this self-portrait directly confronts and engages the viewer. The artist wears Christ's unraveled crown of thorns as a necklace that digs into her neck, signifying her self-representation as a Christian martyr and the enduring pain experienced following her failed marriage. A dead hummingbird, a symbol in Mexican folkloric tradition of luck charms for falling in love, hangs in the center of her necklace. A black cat - symbolic of bad luck and death - crouches behind her left shoulder, and a spider monkey gifted from Rivera, symbolic of evil, is included to her right. Kahlo frequently employed flora and fauna in the background of her bust-length portraits to create a tight, claustrophobic space, using the symbolic element of nature to simultaneously compare and contrast the link between female fertility with the barren and deathly imagery of the foreground. Typically a symbol of good fortune, the meaning of a 'dead' hummingbird is to be reversed. Kahlo, who craves flight, is perturbed and disturbed by the fact that the butterflies in her hair are too delicate to travel far and that the dead bird around her neck, has become an anchor, preyed upon by the nearby cat. In failing to directly translate complex inner feelings it as though the painting illustrates the artist's frustrations.

Oil on canvas on masonite - Nikolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

The Broken Column

The Broken Column is a particularly pertinent example of the combination of Kahlo's emotional and physical pain. The artist's biographer, Hayden Herrera, writes of this painting, 'A gap resembling an earthquake fissure splits her in two. The opened body suggests surgery and Frida's feeling that without the steel corset she would literally fall apart'. A broken ionic column replaces the artist's crumbling spine and sharp metal nails pierce her body. The hard coldness of this inserted column recalls the steel rod that pierced the artist's abdomen and uterus during her streetcar accident. More generally, the architectural feature now in ruins, has associations of the simultaneous power and fragility of the female body. Beyond its physical dimensions, the cloth wrapped around Kahlo's pelvis, recalls Christ's loincloth. Indeed, Kahlo again displays her wounds like a Christian martyr; through identification with Saint Sebastian, she uses physical pain, nakedness, and sexuality to bring home the message of spiritual suffering. Tears dot the artist's face as they do many depictions of the Madonna in Mexico; her eyes stare out beyond the painting as though renouncing the flesh and summoning the spirit. It is as a result of depictions like this one that Kahlo is now considered a Magic Realist. Her eyes are never-changing, realistic, while the rest of the painting is highly fantastical. The painting is not overly concerned with the workings of the subconscious or with irrational juxtapositions that feature more typically in Surrealist works. The Magic Realism movement was extremely popular in Latin America (especially with writers such as Gabriel García Márquez), and Kahlo has been retrospectively included in it by art historians. The notion of being wounded in the way that we see illustrated in The Broken Column , is referred to in Spanish as chingada . This word embodies numerous interrelated meanings and concepts, which include to be wounded, broken, torn open or deceived. The word derives from the verb for penetration and implies domination of the female by the male. It refers to the status of victimhood. The painting also likely inspired a performance and sculptural piece made by Rebecca Horn in 1970 called Unicorn . In the piece Horn walks naked through an arable field with her body strapped in a fabric corset that appears almost identical to that worn by Kahlo in The Broken Column . In the piece by the German performance artist, however, the erect, sky-reaching pillar is fixed to her head rather than inserted into her chest. The performance has an air of mythology and religiosity similar to that of Kahlo's painting, but the column is whole and strong again, perhaps paying homage to Kahlo's fortitude and artistic triumph.

Oil on masonite - Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City, Mexico

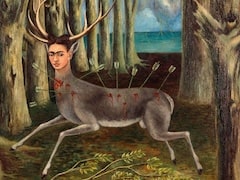

The Wounded Deer

The 1946 painting, The Wounded Deer , further extends both the notion of chingada and the Saint Sebastian motif already explored in The Broken Column . As a hybrid between a deer and a woman, the innocent Kahlo is wounded and bleeding, preyed upon and hunted down in a clearing in the forest. Staring directly at the viewer, the artist confirms that she is alive, and yet the arrows will slowly kill her. The artist wears a pearl earring, as though highlighting the tension that she feels between her social existence and the desire to exist more freely alongside nature. Kahlo does not portray herself as a delicate and gentle fawn; she is instead a full-bodied stag with large antlers and drooping testicles. Not only does this suggest, like her suited appearance in early family photographs, that Kahlo is interested in combining the sexes to create an androgyne, but also shows that she attempted to align herself with the other great artists of the past, most of whom had been men. The branch beneath the stag's feet is reminiscent of the palm branches that onlookers laid under the feet of Jesus as he arrived in Jerusalem. Kahlo continued to identify with the religious figure of Saint Sebastian from this point until her death. In 1953, she completed a drawing of herself in which eleven arrows pierce her skin. Similarly, the artist Louise Bourgeois, also interested in the visualization of pain, used Saint Sebastian as a recurring symbol in her art. She first depicted the motif in 1947 as an abstracted series of forms, barely distinguishable as a human figure; drawn using watercolor and pencil on pink paper, but then later made obvious pink fabric sculptures of the saint, stuck with arrows, she like Kahlo feeling under attack and afraid.

Oil on masonite - Private Collection

Weeping Coconuts (Cocos gimientes)

This still life is exemplary of Kahlo's late work. More frequently associated with her psychological portraiture, Kahlo in fact painted still lifes throughout her career. She depicted fresh fruit and vegetable produce and objects native to Mexico, painting many small-scale still lifes, especially as she grew progressively ill. The anthropomorphism of the fruit in this composition is symbolic of Kahlo's projection of pain into all things as her health deteriorated at the end of her life. In contrast with the tradition of the cornucopia signifying plentiful and fruitful life, here the coconuts are literally weeping, alluding to the dualism of life and death. A small Mexican flag bearing the affectionate and personal inscription "Painted with all the love. Frida Kahlo" is stuck into a prickly pear, signaling Kahlo's use of the fruit as an emblem of personal expression, and communicating her deep respect for all of nature's gifts. During this period, the artist was heavily reliant on drugs and alcohol to alleviate her pain, so albeit beautiful, her still lifes became progressively less detailed between 1951 and 1953.

Oil on board - Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Biography of Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo Calderon was born at La Casa Azul (The Blue House) in Coyoacan, a town on the outskirts of Mexico City in 1907. Her father, Wilhelm Kahlo, was German, and had moved to Mexico at a young age where he remained for the rest of his life, eventually taking over the photography business of Kahlo's mother's family. Kahlo's mother, Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, was of mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry, and raised Frida and her three sisters in a strict and religious household (Frida also had two half sisters from her father's first marriage who were raised in a convent). La Casa Azul was not only Kahlo's childhood home, but also the place that she returned to live and work from 1939 until her death. It later opened as the Frida Kahlo Museum.

Aside from her mother's rigidity, religious fanaticism, and tendency toward outbursts, several other events in Kahlo's childhood affected her deeply. At age six, Kahlo contracted polio; a long recovery isolated her from other children and permanently damaged one of her legs, causing her to walk with a limp after recovery. Wilhelm, with whom Kahlo was very close, and particularly so after the experience of being an invalid, enrolled his daughter at the German College in Mexico City and introduced Kahlo to the writings of European philosophers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and Arthur Schopenhauer. All of Kahlo's sisters instead attended a convent school so it seems that there was a thirst for expansive learning noted in Frida that resulted in her father making different decisions especially for her. Kahlo was grateful for this and despite a strained relationship with her mother, always credited her father with great tenderness and insight. Still, she was interested in both strands of her roots, and her mixed European and Mexican heritage provided life-long fascination in her approach towards both life and art.

Kahlo had a horrible experience at the German School where she was sexually abused and thus forced to leave. Luckily at the time, the Mexican Revolution and the Minister of Education had changed the education policy, and from 1922 girls were admitted to the National Preparatory School. Kahlo was one of the first 35 girls admitted and she began to study medicine, botany, and the social sciences. She excelled academically, became very interested in Mexican culture, and also became active politically.

Early Training

When Kahlo was 15, Diego Rivera (already a renowned artist) was painting the Creation mural (1922) in the amphitheater of her Preparatory School. Upon seeing him work, Kahlo experienced a moment of infatuation and fascination that she would go on to fully explore later in life. Meanwhile she enjoyed helping her father in his photography studio and received drawing instruction from her father's friend, Fernando Fernandez - for whom she was an apprentice engraver. At this time Kahlo also befriended a dissident group of students known as the "Cachuchas", who confirmed the young artist's rebellious spirit and further encouraged her interest in literature and politics. In 1923 Kahlo fell in love with a fellow member of the group, Alejandro Gomez Arias, and the two remained romantically involved until 1928. Sadly, in 1925 together with Alejandro (who survived unharmed) on their way home from school, Kahlo was involved in a near-fatal bus accident.

Kahlo suffered multiple fractures throughout her body, including a crushed pelvis, and a metal rod impaled her womb. She spent one month in the hospital immobile, and bound in a plaster corset, and following this period, many more months bedridden at home. During her long recovery she began to experiment in small-scale autobiographical portraiture, henceforth abandoning her medical pursuits due to practical circumstances and turning her focus to art.

During the months of convalescence at home Kahlo's parents made her a special easel, gave her a set of paints, and placed a mirror above her head so that she could see her own reflection and make self-portraits. Kahlo spent hours confronting existential questions raised by her trauma including a feeling of dissociation from her identity, a growing interiority, and a general closeness to death. She drew upon the acute pictorial realism known from her father's photographic portraits (which she greatly admired) and approached her own early portraits (mostly of herself, her sisters, and her school friends) with the same psychological intensity. At the time, Kahlo seriously considered becoming a medical illustrator during this period as she saw this as a way to marry her interests in science and art.

By 1927, Kahlo was well enough to leave her bedroom and thus re-kindled her relationship with the Cachuchas group, which was by this point all the more political. She joined the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) and began to familiarize herself with the artistic and political circles in Mexico City. She became close friends with the photojournalist Tina Modotti and Cuban revolutionary Julio Antonio Mella. It was in June 1928, at one of Modotti's many parties, that Kahlo was personally introduced to Diego Rivera who was already one of Mexico's most famous artists and a highly influential member of the PCM. Soon after, Kahlo boldly asked him to decide, upon looking at one of her portraits, if her work was worthy of pursuing a career as an artist. He was utterly impressed by the honesty and originality of her painting and assured her of her talents. Despite the fact that Rivera had already been married twice, and was known to have an insatiable fondness for women, the two quickly began a romantic relationship and were married in 1929. According to Kahlo's mother, who outwardly expressed her dissatisfaction with the match, the couple were 'the elephant and the dove'. Her father however, unconditionally supported his daughter and was happy to know that Rivera had the financial means to help with Kahlo's medical bills. The new couple moved to Cuernavaca in the rural state of Morelos where Kahlo devoted herself entirely to painting.

Mature Period

By the early 1930s, Kahlo's painting had evolved to include a more assertive sense of Mexican identity, a facet of her artwork that had stemmed from her exposure to the modernist indigenist movement in Mexico and from her interest in preserving the revival of Mexicanidad during the rise of fascism in Europe. Kahlo's interest in distancing herself from her German roots is evidenced in her name change from Frieda to Frida, and furthermore in her decision to wear traditional Tehuana costume (the dress from earlier matriarchal times). At the time, two failed pregnancies augmented Kahlo's simultaneously harsh and beautiful representation of the specifically female experience through symbolism and autobiography.

During the first few years of the 1930s Kahlo and Rivera lived in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York whilst Rivera was creating various murals. Kahlo also completed some seminal works including Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931) and Self-Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and The United States (1932) with the latter expressing her observations of rivalry taking place between nature and industry in the two lands. It was during this time that Kahlo met and became friends with Imogen Cunningham , Ansel Adams , and Edward Weston . She also met Dr. Leo Eloesser while in San Francisco, the surgeon who would become her closest medical advisor until her death.

Soon after the unveiling of a large and controversial mural that Rivera had made for the Rockefeller Centre in New York (1933), the couple returned to Mexico as Kahlo was feeling particularly homesick. They moved into a new house in the wealthy neighborhood of San Angel. The house was made up of two separate parts joined by a bridge. This set up was appropriate as their relationship was undergoing immense strain. Kahlo had numerous health issues while Rivera, although he had been previously unfaithful, at this time had an affair with Kahlo's younger sister Cristina which understandably hurt Kahlo more than her husband's other infidelities. Kahlo too started to have her own extramarital affairs at this point. Not long after returning to Mexico from the States, she met the Hungarian photographer Nickolas Muray, who was on holiday in Mexico. The two began an on-and-off romantic affair that lasted 10 years, and it is Muray who is credited as the man who captured Kahlo most colorfully on camera.

While briefly separated from Diego following the affair with her sister and living in her own flat away from San Angel, Kahlo also had a short affair with the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi . The two highly politically and socially conscious artists remained friends until Kahlo's death.

In 1936, Kahlo joined the Fourth International (a Communist organization) and often used La Casa Azul as a meeting point for international intellectuals, artists, and activists. She also offered the house where the exiled Russian Communist leader Leon Trotsky and his wife, Natalia Sedova, could take up residence once they were granted asylum in Mexico. In 1937, as well as helping Trotsky, Kahlo and the political icon embarked on a short love affair. Trotsky and his wife remained in La Casa Azul until mid-1939.

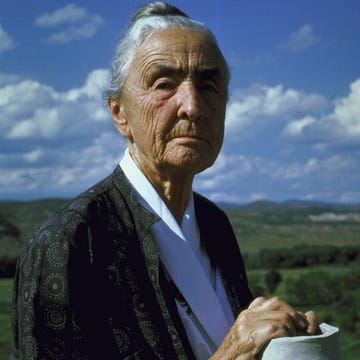

During a visit to Mexico City in 1938, the founder of Surrealism , André Breton , was enchanted with Kahlo's painting, and wrote to his friend and art dealer, Julien Levy , who quickly invited Kahlo to hold her first solo show at his gallery in New York. This time round, Kahlo traveled to the States without Rivera and upon arrival caused a huge media sensation. People were attracted to her colorful and exotic (but actually traditional) Mexican costumes and her exhibition was a success. Georgia O'Keeffe was one of the notable guests to attend Kahlo's opening. Kahlo enjoyed some months socializing in New York and then sailed to Paris in early 1939 to exhibit with the Surrealists there. That exhibition was not as successful and she became quickly tired of the over-intellectualism of the Surrealist group. Kahlo returned to New York hoping to continue her love affair with Muray, but he broke off the relationship as he had recently met somebody else. Thus Kahlo traveled back to Mexico City and upon her return Rivera requested a divorce.

Later Years and Death

Following her divorce, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul. She moved away from her smaller paintings and began to work on much larger canvases. In 1940 Kahlo and Rivera remarried and their relationship became less turbulent as Kahlo's health deteriorated. Between the years of 1940-1956, the suffering artist often had to wear supportive back corsets to help her spinal problems, she also had an infectious skin condition, along with syphilis. When her father died in 1941, this exacerbated both her depression and her health. She again was often housebound and found simple pleasure in surrounding herself by animals and in tending to the garden at La Casa Azul.

Meanwhile, throughout the 1940s, Kahlo's work grew in notoriety and acclaim from international collectors, and was included in several group shows both in the United States and in Mexico. In 1943, her work was included in Women Artists at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century Gallery in New York. In this same year, Kahlo accepted a teaching position at a painting school in Mexico City (the school known as La Esmeralda ), and acquired some highly devoted students with whom she undertook some mural commissions. She struggled to continue making a living from her art, never accommodating to clients' wishes if she did not like them, but luckily received a national prize for her painting Moses (1945) and then The Two Fridas painting was bought by the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1947. Meanwhile, the artist grew progressively ill. She had a complicated operation to try and straighten her spine, but it failed and from 1950 onwards, she was often confined to a wheelchair.

She continued to paint relatively prolifically in her final years while also maintaining her political activism, and protesting nuclear testing by Western powers. Kahlo exhibited one last time in Mexico in 1953 at Lola Alvarez Bravo's gallery, her first and only solo show in Mexico. She was brought to the event in an ambulance, with her four-poster bed following on the back of a truck. The bed was then placed in the center of the gallery so that she could lie there for the duration of the opening. Kahlo died in 1954 at La Casa Azul. While the official cause of death was given as pulmonary embolism, questions have been raised about suicide - either deliberate of accidental. She was 47 years old.

The Legacy of Frida Kahlo

As an individualist who was disengaged from any official artistic movement, Kahlo's artwork has been associated with Primitivism , Indigenism , Magic Realism , and Surrealism . Posthumously, Kahlo's artwork has grown profoundly influential for feminist studies and postcolonial debates, while Kahlo has become an international cultural icon. The artist's celebrity status for mass audiences has at times resulted in the compartmentalization of the artist's work as representative of interwar Latin American artwork at large, distanced from the complexities of Kahlo's deeply personal subject matter. Recent exhibitions, such as Unbound: Contemporary Art After Frida Kahlo (2014) at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago have attempted to reframe Kahlo's cultural significance by underscoring her lasting impact on the politics of the body and Kahlo's challenge to mainstream aesthetics of representation. Dreamers Awake (2017) held at The White Cube Gallery in London further illustrated the huge influence that Frida Kahlo and a handful of other early female Surrealists have had on the development and progression of female art.

The legacy of Kahlo cannot be underestimated or exaggerated. Not only is it likely that every female artist making art since the 1950s will quote her as an influence, but it is not only artists and those who are interested in art that she inspires. Her art also supports people who suffer as result of accident, as result of miscarriage, and as result of failed marriage. Through imagery, Kahlo articulated experiences so complex, making them more manageable and giving viewers hope that they can endure, recover, and start again.

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Frida Kahlo

- Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo Our Pick By Hayden Herrera

- Frida Kahlo: Her Photos By Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

- Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up Our Pick By Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa

- Frida Kahlo at Home Our Pick By Suzanne Barbezat

- Frida Kahlo: The Last Interview: and Other Conversations (The Last Interview Series) By Hayden Herrera

- Frida Kahlo I Paint My Reality By Christina Burrus

- Frida & Diego: Art, Love, Life By Cateherine Reef

- The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait Our Pick By Carlos Fuentes

- Frida by Frida By Frida Kahlo and Raquel Tibol

- Frida Kahlo: The Paintings Our Pick By Hayden Herrera

- Frida Kahlo By Emma Dexter, Tanya Barson

- Frida Kahlo Retrospective By Peter von Becker, Ingried Brugger, Salamon Grimberg, Cristina Kahlo, Arnaldo Kraus, Helga Prignitz-Poda, Francisco Reyes Palma, Florian Steininger, Jeanette Zqingenberger

- Frida Kahlo Masterpieces of Art By Julian Beecroft

- Kahlo (Basic Art Series 2.0) Our Pick By Andrea Kettenmann

- Frida Kahlo's Gadren Our Pick By Adriana Zavala

- The Museum of Modern Art: Discussion of Portrait with Cropped Hair by Frida Kahlo

- Frida Kahlo: The woman behind the legend - TED_Ed

- Frida Kahlo's 'The Two Fridas” - Great Art Explained Our Pick

- Frida Kahlo: Life of an Artist - Art History School Our Pick

- A Tour of Frida Kahlo’s Blue House – La Casa Azul

- La Casa Azul - Museo Frida Kahlo in Mexico City Our Pick The artist's house museum

- Works from La Casa Azul - Museo Frida Kahlo in Mexico City Our Pick By The Google Cultural Institute

- Frida Kahlo at the Tate Modern Website of the 2005 Exhibition

- Why Contemporary Art Is Unimaginable Without Frida Kahlo By Priscilla Frank / The Huffington Post / April 29, 2014

- Diary of a Mad Artist By Amy Fine Collins / Vanity Fair / July 2011

- The People's Artist, Herself a Work of Art Our Pick By Holland Cotter / The New York Times / February 29, 2008

- Let Fridamania Commence By Adrian Searle / The Guardian / June 6, 2005

- The Trouble with Frida Kahlo By Stephanie Mencimer / Washington Monthly / June 2002

- Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist Reading Our Pick By Liza Bakewell / Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies / 1993

- Frida Kahlo: Portrait of Chronic Pain By Carol A. Courtney, Michael A. O'Hearn, and Carla C. Franck / Physical Therapy / January 2017

- Medical Imagery in the Art of Frida Kahlo Our Pick By David Lomas, Rosemary Howell / British Medical Journal / December 1989

- Fashioning National Identity: Frida Kahlo in “Gringolandia" Our Pick By Rebecca Block and Lynda Hoffman-Jeep / Women’s Art Journal / 1999

- Art Critics on Frida Kahlo: A Comparison of Feminist and Non-Feminist Voices By Elizabeth Garber / Art Education / March 1992

- NPR: Mexican Artist Used Politics to Rock the Boat Artist Judy Chicago discusses the book she co-authored: "Frida Kahlo: Face to Face"

- Frida Our Pick A 2002 Biographical Film on Frida Kahlo, Starring Salma Hayek

- The Frida Kahlo Corporation A Company with Products Inspired by Frida Kahlo

- How Frida Kahlo Became a Global Brand By Tess Thackara / Artsy.com / Dec 19, 2017 /

Similar Art

Portrait of Lupe Marin (1938)

Egg in the church or The Snake (Date Unknown)

Self-Portrait (c. 1937-38)

Einhorn (Unicorn) (1970-72)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Katlyn Beaver

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Rebecca Baillie

- Earth and Environment

- Literature and the Arts

- Philosophy and Religion

- Plants and Animals

- Science and Technology

- Social Sciences and the Law

- Sports and Everyday Life

- Additional References

- Latin American Art: Biographies

Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was a Mexican painter often associated with the European Surrealists as well as with her husband, Mexican muralist Diego Rivera . She was noted for her intense autobiographical paintings.

Frida Kahlo, was born in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City , in 1907, the daughter of a German-Jewish photographer and an Indian-Spanish mother. Despite her European background, Kahlo identified all her life with New World, Mexican heritage, dressing in native clothing wherever she travelled. Injured in a bus accident at the age of 15, Kahlo was disabled for life. After numerous operations to correct her spinal and internal injuries, she eventually became an invalid prior to her death at the age of 47. Like her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera , Kahlo maintained a life-long commitment to leftist politics, and in the 1930s she accompanied him on several trips to the United States where he was commissioned to do murals in New York , Detroit, and San Francisco . The most controversial of these was a mural for Rockefeller Center which was cancelled because it included a portrait of Lenin that Rivera refused to remove. Kahlo died in Mexico City in 1954.

Unlike Rivera's murals, which were grandiose and filled with political ideology, Kahlo's work was intimate, personal, and in the tradition of easel painting. Usually autobiographical, she painted the events of her life with symbolic elements and situations, creating a dreamlike reality, frighteningly real but fantastic and magical. One painting, Broken Column (1944), shows the artist against a bleak desert landscape with her flesh cut away to reveal a cracked classical column in place of her spine, a painful record of her life-long struggle with the psychological and physical aftermath of her accident. Another, The Wounded Deer (1946), shows Kahlo as a deer with her own human head, shot full of arrows in a mysteriously forlorn forest with a body of water in the background. She painted many self-portraits throughout her life.

Kahlo incorporated elements of Mexican folk art into her paintings. Thematic content often takes precedence over a fidelity to realism, and the scale of things represents symbolic relationships rather than physical ones. Reoccurring themes of earthly suffering and the redemptive cycle of nature reflect the mixture of Spanish Catholicism and Indian religion prominent in Mexican culture. Kahlo's color, while naturalistic, is flat and dramatic.

The French Surrealist poet Andre Breton , who lived for a while in Mexico, claimed Kahlo as a Surrealist. She bristled at this association with artists living thousands of miles away and working with psychoanalytic theories of the subconscious. She claimed, "Breton thought I was a Surrealist but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality." She did, however, show at the Julian Levy Gallery in New York , known for showing Surrealism, and she travelled to Paris at Breton's urging to show her work.

Early in her life her work and reputation as an artist were overshadowed by her relationship to Rivera, who was older and famous before they met. She also seemed conflicted by her sense of duty to him as a wife. In the late 1930s she asserted her independence from him, and in 1939 they were divorced, only to be remarried a short time later. This event served as an important theme in her work of the period. In contrast to Rivera, who was relatively wealthy from his work, Kahlo had great difficulties supporting herself from the sale of her paintings.

Together they led a flamboyant life in Mexico and during their trips to the United States . They were at the center of Mexican cultural life in the 1920s and 1930s when Mexican artists and intellectuals were rediscovering their own heritage and rejecting European ties. This desire for a Mexican art came in part from an interest in leftist politics. Kahlo was a life-time member of the Communist Party , which believed that art should serve the Mexican masses rather than a European elite. Unlike Rivera, Kahlo was not a muralist, but later in her life, when she was asked to teach in an important state art school, she organized teams of students to execute public works.

During her life Frida Kahlo received more recognition as a painter in the United States than in Mexico. She was included in several important group exhibitions, including "Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art" at the Museum of Modern Art and a show of women artists at Peggy Guggenheim 's Art of This Century Gallery in New York. Her first one-person show in Mexico at the Galeria Arte Contemporaneo occurred only one year before her death and in part because her death was anticipated. After her death in 1954 her reputation grew in Mexico and diminished in the United States, a time when communists and their sympathizers were discredited. Diego Rivera himself is less known in the United States now than in the 1930s.

Like many prominent women artists of her generation, such as Louise Nevelson and Georgia O'Keefe, Frida Kahlo's art was individualistic and stood apart from mainstream work. They were often overlooked by critics and historians because they were women and outsiders and because their art was difficult to fit into movements and categories. Kahlo has received increased attention since the 1970s as objections to her politics have softened and as interest grows about the role of women artists and intellectuals in history. Concepts of modernism are also being expanded to encompass an uninterrupted strain of figurative art throughout the 20th century, into which Kahlo's painting smoothly fits. Frida Kahlo was the subject of major retrospective exhibitions in the United States in 1978-1979 and in 1983 and in England in 1982.

Further Reading

Hayden Herrera published Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (1983), an extensive work that focuses on her life. Her painting is discussed more historically and critically in Whitney Chadwick's Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (1985), which focuses on women artists who worked within Surrealist circles but were seldom recorded in its history. □

Cite this article Pick a style below, and copy the text for your bibliography.

" Frida Kahlo . " Encyclopedia of World Biography . . Encyclopedia.com. 18 Mar. 2024 < https://www.encyclopedia.com > .

"Frida Kahlo ." Encyclopedia of World Biography . . Encyclopedia.com. (March 18, 2024). https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/frida-kahlo

"Frida Kahlo ." Encyclopedia of World Biography . . Retrieved March 18, 2024 from Encyclopedia.com: https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/frida-kahlo

Citation styles

Encyclopedia.com gives you the ability to cite reference entries and articles according to common styles from the Modern Language Association (MLA), The Chicago Manual of Style, and the American Psychological Association (APA).

Within the “Cite this article” tool, pick a style to see how all available information looks when formatted according to that style. Then, copy and paste the text into your bibliography or works cited list.

Because each style has its own formatting nuances that evolve over time and not all information is available for every reference entry or article, Encyclopedia.com cannot guarantee each citation it generates. Therefore, it’s best to use Encyclopedia.com citations as a starting point before checking the style against your school or publication’s requirements and the most-recent information available at these sites:

Modern Language Association

http://www.mla.org/style

The Chicago Manual of Style

http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html

American Psychological Association

http://apastyle.apa.org/

- Most online reference entries and articles do not have page numbers. Therefore, that information is unavailable for most Encyclopedia.com content. However, the date of retrieval is often important. Refer to each style’s convention regarding the best way to format page numbers and retrieval dates.

- In addition to the MLA, Chicago, and APA styles, your school, university, publication, or institution may have its own requirements for citations. Therefore, be sure to refer to those guidelines when editing your bibliography or works cited list.

More From encyclopedia.com

About this article, related topics, you might also like.

- Kahlo, Frida: 1907—1954: Artist

- Kahlo, Frida (1907–1954)

- Guerrero, Xavier (1896–1975)

- Romero, Alejandro: 1948—: Painter and Muralist

- Kahlo, Frida 1907–1954

- Mexican art and architecture

- Retablos and Ex-Votos

NEARBY TERMS

My painting carries with it the message of pain.

- Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo and her paintings

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo is remembered for her self-portraits, pain and passion, and bold, vibrant colors. She is celebrated in Mexico for her attention to Mexican and indigenous culture and by feminists for her depiction of the female experience and form.

Kahlo, who suffered from polio as a child, nearly died in a bus accident as a teenager. She suffered multiple fractures of her spine, collarbone and ribs, a shattered pelvis, broken foot and a dislocated shoulder. She began to focus heavily on painting while recovering in a body cast. In her lifetime, she had 30 operations.

Life experience is a common theme in Kahlo's approximately 200 paintings, sketches and drawings. Her physical and emotional pain are depicted starkly on canvases, as is her turbulent relationship with her husband, fellow artist Diego Rivera , who she married twice. Of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits.

The devastation to her body from the bus accident is shown in stark detail in The Broken Column . Kahlo is depicted nearly naked, split down the middle, with her spine presented as a broken decorative column. Her skin is dotted with nails. She is also fitted with a surgical brace.

Kahlo's first self-portrait was Self-Portrait in a Velvet Dress in 1926. It was painted in the style of 19th Century Mexican portrait painters who themselves were greatly influenced by the European Renaissance masters. She also sometimes drew from the Mexican painters in her use of a background of tied-back drapes. Self-Portrait - Time Flies (1929), Portrait of a Woman in White (1930) and Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937) all bear this background.

I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best." - Frida Kahlo

In her second-self portrait, "Time Flies," Kahlo uses a folk style and vibrant colors. She wears peasant clothing, and the red, white and green in the painting are the colors of the Mexican flag.

During her life, self portrait is a subject that Frida Kahlo always returns to, as artists have always returned to their beloved themes - Rembrandt his Self Portrait , Vincent van Gogh his Sunflowers , and Claude Monet his Water Lilies .

Frida and Diego: Love and Pain

Kahlo and Rivera had a tumultuous relationship, marked by multiple affairs on both sides. Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair (1940), Kahlo is depicted in a man's suit, holding a pair of scissors, with her fallen hair around the chair in which she sits. This represents the times she would cut the hair Rivera loved when he had affairs.

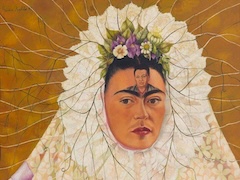

The 1937 painting Memory, the Heart , shows Kahlo's pain over her husband's affair with her younger sister Christina. A large broken heart at her feet shows the intensity of Kahlo's anguish. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera divorced in 1939, but reunited a year later and remarried. The Two Fridas (1939) depicts Kahlo twice, shortly after the divorce. One Frida wears a costume from the Tehuana region of Mexico, representing the Frida that Diego loved. The other Frida wears a European dress as the woman who Diego betrayed and rejected. Later, she is back in Tehuana dress in Self-Portrait as a Tehuana (1943) and Self Portrait (1948).

Pre-Columbian artifacts were common both in the Kahlo/Rivera home (Diego collected sculptures and idols, and Frida collected Jewelry) and in Kahlo's paintings. She wore jewelry from this period in Self-Portrait - Time Flies (1926), Self-Portrait With Monkey (1938) and Self-Portrait With Braid (1941), among others. Other Pre-Columbian artifacts are found in The Four Inhabitants of Mexico City (1938), Girl With Death Mask (1938) and Self-Portrait With Small Monkeys (1945).

My painting carries with it the message of pain." - Frida Kahlo

Surreal or Realist?

Frida Kahlo participated in the "International Exhibition of Surrealism" in 1940 at the Galeria de Arte, Mexicano. There, she exhibited her two largest paintings: The Two Fridas and The Wounded Table (1940). Surrealist Andrew Breton considered Kahlo a surrealistic, a label Kahlo rejected, saying she just painted her reality. However, In 1945, when Don Jose Domingo Lavin asked Frida Kahlo to read the book Moses and Monotheism by Sigmund Freud - whose psychoanalysis works Surrealism is based on - and paint her understanding and interpretation of this book. Frida Kahlo painted Moses , and this painting was recognized as second prize at the annual art exhibition in the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Kahlo did not sell many paintings in her lifetime, although she painted occasional portraits on commission. She had only one solo exhibition in Mexico in her lifetime, in 1953, just a year before her death at the age of 47.

Today, her works sell for very high prices. In May 2006, Frida Kahlo self-portrait, Roots , was sold for $5.62 million at a Sotheby's auction in New York, sets a record as the most expensive Latin American work ever purchased at auction, and also makes Frida Kahlo one of the highest-selling woman in art.

Widely known for her Marxist leanings, Frida, along with Marxism Revolutionary Che Guevara and a small band of contemporary figures, has become a countercultural symbol of the 20th century, and created a legacy in art history that continues to inspire the imagination and mind. Born in 1907, dead at 47, Frida Kahlo achieved celebrity even in her brief lifetime that extended far beyond Mexico's borders, although nothing like the cult status that would eventually make her the mother of the selfie, her indelible image recognizable everywhere.

At the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City, her personal belongings are on display throughout the house, as if she still lived there. Kahlo was born and grew up in this building, whose cobalt walls gave way to the nickname of the Blue House. She lived there with her husband for some years, and she died there. The facility is the most popular museum in the Coyoacan neighborhood and among the most visited in Mexico City.

The Two Fridas

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace & Hummingbird

Viva la Vida, Watermelons

The Wounded Deer

Henry Ford Hospital

Without Hope

Me and My Parrots

What the Water Gave Me

Frida and Diego Rivera

The Wounded Table

Diego and I

My Dress Hangs There

Self Portrait with Monkey

Self Portrait as a Tehuana

Fulang Chang and I

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Modernisms 1900-1980

Course: modernisms 1900-1980 > unit 7, frida kahlo, introduction.

- Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera

- Kahlo, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas)

- Kahlo, The Two Fridas

- Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey

- Rosa Rolanda, Self-Portrait

- Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence

- Lam, The Jungle

- Hector Hyppolite, Ogou Feray also known as Ogoun Ferraille

- Latin American Modernism

The Two Fridas

Self-portrait with cropped hair.

- Adriana Zavala, Becoming Modern, Becoming Tradition: Women, Gender, and Representation in Mexican Art (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), p. 3

Want to join the conversation?

Encyclopedia of Humanities

The most comprehensive and reliable Encyclopedia of Humanities

Frida Kahlo

We explain who Frida Kahlo was, and explore her childhood and the development of her works. In addition, we discuss her style and death.

Who was Frida Kahlo?

Frida Kahlo, original name Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón, was a Mexican painter born in Coyoacán on July 6, 1907 . She died on July 13, 1954.

As a child, Frida contracted polio and, at the age of 18, she suffered a severe bus accident that nearly took her life . As a result, she had to undergo 32 surgeries over the years. The hardships she faced are vividly reflected in her artwork.

She was the wife of renowned Mexican painter Diego Rivera , who introduced her to the circle of the most prominent artists of the time, and received acclaim from notable art figures such as Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, Wassily Kandinsky, and Pablo Picasso.

Frida Kahlo’s works also convey her political and social commitment. Widespread recognition came posthumously , especially from the 1970s onward, and she is now regarded as one of the major artists in Latin America .

- See also: Eva Perón

Birth and childhood of Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo was born in Coyoacán, Mexico, on July 6, 1907. Her father, German photographer Guillermo Kahlo, was of Hungarian-Jewish descent, and her mother, Matilde Calderón, was Mexican of Spanish and indigenous ancestry, born in Mexico City.

As a child, Frida learned to develop, retouch, and color photographs under her father's guidance , which later influenced her passion for painting.

At the age of six, she contracted polio , and her father took care of her during the six months of her recovery. As a consequence of the disease, she was afflicted with a limp throughout her life.

Accident and painting of Frida Kahlo

In 1922, Frida entered the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, her intention being to study medicine. However, on September 17, 1925, the bus in which she was traveling collided with a streetcar , and Frida was severely injured.

Although she managed to survive, she suffered multiple injuries that would shape her life. Her spine suffered several fractures and, over the years, she underwent over 30 surgeries and had to wear plaster corsets. During the initial months of convalescence, she was bedridden; she abandoned the idea of studying medicine and began painting . In 1926, she painted her first self-portrait.

Frida Kahlo and the Communist Party

Two years after the accident, Frida had recovered sufficiently to reconnect with friends and associate with personalities in the fields of art, thought, and politics. She identified with a cultural movement seeking to recover elements of the Mexican popular tradition , including indigenous influences.

In 1928, her friend Germán del Campo introduced her to Cuban communist leader Julio Antonio Mella, who was in exile in Mexico with his partner, Italian photographer Tina Modotti. Frida began attending meetings of the Mexican Communist Party and became romantically involved with Diego Rivera, who had been a member of the party since 1922.

Following a stay in the United States between 1930 and 1933 with Rivera, whom she had married in 1929, she returned to Mexico City. Between 1937 and 1939, she provided refuge to Russian communist exile Leon Trotsky , persecuted by the Stalinist government, who was eventually assassinated in 1940.

Frida maintained her adherence to communism for the rest of her life . Upon her death, her coffin was draped with the flag of the Mexican Communist Party.

Frida Kahlo's marriage to Diego Rivera

Frida met muralist Diego Rivera in 1922 , when he was painting a mural at the National Preparatory School she attended. However, their romantic relationship only began in 1928 when they were introduced by communist activists Julio Antonio Mella and Tina Modotti.

Frida shared her artwork with Rivera, who encouraged her to continue painting. They married in 1929. She was 22 years old and he was 42 . The marriage was tumultuous, marred by extramarital affairs from both parties, most notably Rivera's relationship with Frida's younger sister, which led to their divorce in 1939. However, they remarried at the end of 1940.

Frida's relationship with Rivera influenced not only her artistic style but also the way she dressed. She usually wore colorful garments characteristic of indigenous women in some regions of Mexico, particularly the Tehuana dresses, which pleased her husband. These included necklaces, ornamental combs, or flower headdresses, which became a hallmark of Frida Kahlo's image.

Attempts at motherhood and death

Frida became pregnant with Rivera's child on three occasions but, due to her health problems, she lost each pregnancy . Some of her artwork conveys her thwarted desire for motherhood and the pain from the lost pregnancies.

Throughout her life, Frida continued to suffer from ailments and medical treatments. Her health deteriorated towards 1950, and she eventually died on July 13, 1954 at the age of 47 , due to a pulmonary embolism. Some versions suggested it might have been a suicide, but no evidence has ever appeared to support this theory.

She had expressed her wish not to be buried , on the grounds that she had been bedridden for many years. Her body was cremated and her ashes were placed in a pre-Columbian urn at The Blue House (La Casa Azul) in Coyoacán, where she had lived most of her life and which today houses the Frida Kahlo Museum.