- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

Should the Death Penalty Be Abolished?

In its last six months, the United States government has put 13 prisoners to death. Do you think capital punishment should end?

By Nicole Daniels

Students in U.S. high schools can get free digital access to The New York Times until Sept. 1, 2021.

In July, the United States carried out its first federal execution in 17 years. Since then, the Trump administration has executed 13 inmates, more than three times as many as the federal government had in the previous six decades.

The death penalty has been abolished in 22 states and 106 countries, yet it is still legal at the federal level in the United States. Does your state or country allow the death penalty?

Do you believe governments should be allowed to execute people who have been convicted of crimes? Is it ever justified, such as for the most heinous crimes? Or are you universally opposed to capital punishment?

In “ ‘Expedited Spree of Executions’ Faced Little Supreme Court Scrutiny ,” Adam Liptak writes about the recent federal executions:

In 2015, a few months before he died, Justice Antonin Scalia said he w o uld not be surprised if the Supreme Court did away with the death penalty. These days, after President Trump’s appointment of three justices, liberal members of the court have lost all hope of abolishing capital punishment. In the face of an extraordinary run of federal executions over the past six months, they have been left to wonder whether the court is prepared to play any role in capital cases beyond hastening executions. Until July, there had been no federal executions in 17 years . Since then, the Trump administration has executed 13 inmates, more than three times as many as the federal government had put to death in the previous six decades.

The article goes on to explain that Justice Stephen G. Breyer issued a dissent on Friday as the Supreme Court cleared the way for the last execution of the Trump era, complaining that it had not sufficiently resolved legal questions that inmates had asked. The article continues:

If Justice Breyer sounded rueful, it was because he had just a few years ago held out hope that the court would reconsider the constitutionality of capital punishment. He had set out his arguments in a major dissent in 2015 , one that must have been on Justice Scalia’s mind when he made his comments a few months later. Justice Breyer wrote in that 46-page dissent that he considered it “highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment,” which bars cruel and unusual punishments. He said that death row exonerations were frequent, that death sentences were imposed arbitrarily and that the capital justice system was marred by racial discrimination. Justice Breyer added that there was little reason to think that the death penalty deterred crime and that long delays between sentences and executions might themselves violate the Eighth Amendment. Most of the country did not use the death penalty, he said, and the United States was an international outlier in embracing it. Justice Ginsburg, who died in September, had joined the dissent. The two other liberals — Justices Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — were undoubtedly sympathetic. And Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who held the decisive vote in many closely divided cases until his retirement in 2018, had written the majority opinions in several 5-to-4 decisions that imposed limits on the death penalty, including ones barring the execution of juvenile offenders and people convicted of crimes other than murder .

In the July Opinion essay “ The Death Penalty Can Ensure ‘Justice Is Being Done,’ ” Jeffrey A. Rosen, then acting deputy attorney general, makes a legal case for capital punishment:

The death penalty is a difficult issue for many Americans on moral, religious and policy grounds. But as a legal issue, it is straightforward. The United States Constitution expressly contemplates “capital” crimes, and Congress has authorized the death penalty for serious federal offenses since President George Washington signed the Crimes Act of 1790. The American people have repeatedly ratified that decision, including through the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994 signed by President Bill Clinton, the federal execution of Timothy McVeigh under President George W. Bush and the decision by President Barack Obama’s Justice Department to seek the death penalty against the Boston Marathon bomber and Dylann Roof.

Students, read the entire article , then tell us:

Do you support the use of capital punishment? Or do you think it should be abolished? Why?

Do you think the death penalty serves a necessary purpose, like deterring crime, providing relief for victims’ families or imparting justice? Or is capital punishment “cruel and unusual” and therefore prohibited by the Constitution? Is it morally wrong?

Are there alternatives to the death penalty that you think would be more appropriate? For example, is life in prison without the possibility of parole a sufficient sentence? Or is that still too harsh? What about restorative justice , an approach that “considers harm done and strives for agreement from all concerned — the victims, the offender and the community — on making amends”? What other ideas do you have?

Vast racial disparities in the administration of the death penalty have been found. For example, Black people are overrepresented on death row, and a recent study found that “defendants convicted of killing white victims were executed at a rate 17 times greater than those convicted of killing Black victims.” Does this information change or reinforce your opinion of capital punishment? How so?

The Federal Death Penalty Act prohibits the government from executing an inmate who is mentally disabled; however, in the recent executions of Corey Johnson , Alfred Bourgeois and Lisa Montgomery , their defense teams, families and others argued that they had intellectual disabilities. What role do you think disability or trauma history should play in how someone is punished, or rehabilitated, after committing a crime?

How concerned should we be about wrongfully convicted people being executed? The Innocence Project has proved the innocence of 18 people on death row who were exonerated by DNA testing. Do you have worries about the fair application of the death penalty, or about the possibility of the criminal justice system executing an innocent person?

About Student Opinion

• Find all of our Student Opinion questions in this column . • Have an idea for a Student Opinion question? Tell us about it . • Learn more about how to use our free daily writing prompts for remote learning .

Students 13 and older in the United States and the United Kingdom, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Nicole Daniels joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2019 after working in museum education, curriculum writing and bilingual education. More about Nicole Daniels

March 19, 2024

Evidence Does Not Support the Use of the Death Penalty

Capital punishment must come to an end. It does not deter crime, is not humane and has no moral or medical basis

By The Editors

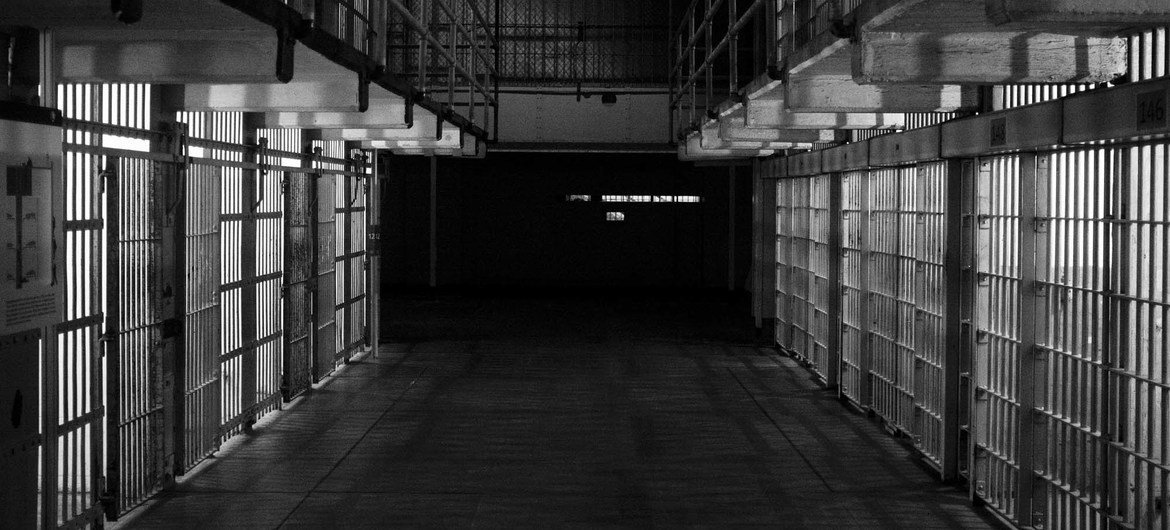

A death penalty vigil, held in 2021 outside an Indiana penitentiary.

Bryan Woolston/Reuters/Redux

It is long past time to abolish the death penalty in the U.S.

Capital punishment was halted in the U.S. in 1972 but reinstated in 1976, and since then, nearly 1,600 people have been executed. To whose gain? Study after study shows that the death penalty does not deter crime, puts innocent people to death , is racially biased , and is cruel and inhumane. It is state-sanctioned homicide, wholly ineffective, often botched, and a much more expensive punishment than life imprisonment. There is no ethical, scientifically supported, medically acceptable or morally justifiable way to carry it out.

The recent execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith demonstrates this barbarity. After a failed attempt at lethal injection by prison officials seemingly inexperienced in the placement of an IV, the state of Alabama killed Smith in January using nitrogen gas . The Alabama attorney general claimed that this method of execution was fast and humane , despite no supporting evidence. Eyewitnesses recounted that Smith thrashed during the nitrogen administration and took more than 20 minutes to die.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Opposition to the death penalty is growing among the American public , and the Biden administration must follow through on its promise to end this horror. The Department of Justice must heed its own admission that the death penalty doesn’t stop crime, and our legislators must continue to take up the issue on the congressional floor. The few states that still condemn people to death must follow the lead of states that have considered the evidence and rejected capital punishment.

Programs such as the Innocence Project have shown, over and over, that innocent people have been sentenced to death. Since 1973 nearly 200 people on death row have been exonerated, based on appeals, the reopening of cases, and the entrance of new and sometimes previously suppressed evidence. People have recanted testimony, and supposedly airtight cases have been poked full of evidentiary holes.

Through the death penalty, the criminal justice system has killed at least 20 people now believed to have been innocent and uncounted others whose cases have not been reexamined . Too many of these victims have been Black or Hispanic. This is not justice. These are state-sanctioned hate crimes.

Using rigorous statistical and experimental control methods, both economics and criminal justice studies have consistently found that there is no evidence for deterrence of violent crimes in states that allow capital punishment. One such study, a 2009 paper by criminology researchers at the University of Dallas, outlines experimental and statistical flaws in econometrics-based death penalty studies that claim to find a correlated reduction in violent crime. The death penalty does not stop people from killing. Executions don’t make us safer.

The methods used to kill prisoners are inhumane. Electrocution fails , causing significant pain and suffering. Joel Zivot, an anesthesiologist who criticizes the use of medicines in carrying out the death penalty, has found (at the request of lawyers of death row inmates) that the lungs of prisoners who were killed by lethal injection were often heavy with fluid and froth that suggested they were struggling to breathe and felt like they were drowning. Nitrogen gas is used in some veterinary euthanasia, but based in part on the behavior of rats in its presence, it is “unacceptable” for mammals , according to the American Veterinary Medical Association. This means that Smith, as his lawyers claimed in efforts to stop his execution, became a human subject in an immoral experiment.

Courts have often decided, against the abundant evidence, that these killings are constitutional and do not fall under the “cruel and unusual punishment” clause of the 8th Amendment or, in Smith’s appeal , both the 8th Amendment and the due process protection clause of the 14th amendment.

A small number of prosecutors and judges in a few states, mostly in the South, are responsible for most of the death sentences being handed down in the U.S. today. It’s a power they should not be able to wield. Smith was sentenced to life in prison by a jury before the judge in his case overruled the jury and gave him the death sentence.

A furious urge for vengeance against those who have done wrong—or those we think have done wrong—is the biggest motivation for the death penalty. But this desire for violent retribution is the very impulse that our criminal justice system is made to check, not abet. Elected officials need to reform this aspect of our justice system at both the state and federal levels. Capital punishment does not stop crime and mocks both justice and humanity. The death penalty in the U.S. must come to an end.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American .

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Capital punishment.

Capital punishment, or “the death penalty,” is an institutionalized practice designed to result in deliberately executing persons in response to actual or supposed misconduct and following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that the person is responsible for violating norms that warrant execution. Punitive executions have historically been imposed by diverse kinds of authorities, for an expansive range of conduct, for political or religious beliefs and practices, for a status beyond one’s control, or without employing any significant due process procedures. Punitive executions also have been and continue to be carried out more informally, such as by terrorist groups, urban gangs, or mobs. But for centuries in Europe and America, discussions have focused on capital punishment as an institutionalized, rule-governed practice of modern states and legal systems governing serious criminal conduct and procedures.

Capital punishment has existed for millennia, as evident from ancient law codes and Plato’s famous rendition of Socrates’s trial and execution by democratic Athens in 399 B.C.E. Among major European philosophers, specific or systematic attention to the death penalty is the exception until about 400 years ago. Most modern philosophic attention to capital punishment emerged from penal reform proponents, as principled, moral evaluation of law and social practice, or amidst theories of the modern state and sovereignty. The mid-twentieth century emergence of an international human rights regime and American constitutional controversies sparked anew much philosophic focus on theories of punishment and the death penalty, including arbitrariness, mistakes, or discrimination in the American institution of capital punishment.

The central philosophic question about capital punishment is one of moral justification: on what grounds, if any, is the state’s deliberate killing of identified offenders a morally justifiable response to voluntary criminal conduct, even the most serious of crimes, such as murder? As with questions about the morality of punishment, two broadly different approaches are commonly distinguished: retributivism, with a focus on past conduct that merits death as a penal response, and utilitarianism or consequentialism, with attention to the effects of the death penalty, especially any effects in preventing more crime through deterrence or incapacitation. Section One provides some historical context and basic concepts for locating the central philosophic question about capital punishment: Is death the amount or kind of penalty that is morally justified for the most serious of crimes, such as murder? Section Two attends to classic considerations of lex talionis (“the law of retaliation”) and recent retributivist approaches to capital punishment that involve the right to life or a conception of fairness. Section Three considers classic utilitarian approaches to justifying the death penalty: primarily as preventer of crime through deterrence or incapacitation, but also with respect to some other consequences of capital punishment. Section Four attends to relatively recent approaches to punishment as expression or communication of fundamental values or norms, including for purposes of educating or reforming offenders. Section Five explores issues of justification related to the institution of capital punishment, as in America: Is the death penalty morally justifiable if imperfect procedures produce mistakes, caprice, or (racial) discrimination in determining who is to be executed? Or if the actual execution of capital punishment requires unethical conduct by medical practitioners or other necessary participants? Section Six considers the moral grounds, if any exist, for the state’s authority to punish by death.

Table of Contents

- Historical Practices

- Philosophic Frameworks and Approaches

- Classic Retributivism: Kant and lex talionis

- Lex talionis as a Principle of Proportionality

- Retributivism and the Right to Life

- Retributivism and Fairness

- Challenges to Retributivism

- Classic Utilitarian Approaches: Bentham, Beccaria, Mill

- Empirical Considerations: Incapacitation, Deterrence

- Utilitarian Defenses: “Common Sense” and “Best Bet”

- Challenges to Utilitarianism

- Other Consequential Considerations

- Capital Punishment as Communication

- Procedural Issues: Imperfect Justice

- Discrimination: Race, Class

- Medicine and the Death Penalty

- Costs: Economic Issues

- State Authority and Capital Punishment

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

1. Context and Basic Concepts

A. historical practices.

Much philosophic focus on the death penalty is modern and relatively recent. The phrase ‘capital punishment’ is older, used for nearly a millennium to signify the death penalty. The classical Latin and medieval French roots of the term ‘capital’ indicate a punishment involving the loss of head or life, perhaps reflecting the use of beheading as a form of execution. The actual practice of capital punishment is ancient, emerging much earlier than the familiar terms long used to refer to it. In the ancient world, the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (circa 1750 B.C.E.) included about 25 capital crimes; the Mosaic Code of the ancient Hebrews identifies numerous crimes punishable by death, invoking, like other ancient law codes, lex talionis , “the law of retaliation”; Draco’s Code of 621 B.C.E. Athens punished most crimes by death, and later Athenian law famously licensed the trial and death of Socrates; the fifth century B.C.E. Twelve Tables of Roman law include capital punishment for such crimes as publishing insulting songs or disturbing the nocturnal peace of urban areas, and later Roman law famously permitted the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth. Even in such early practices, capital punishment was seen as within the authority of political rulers, embodied as a legal institution, and employed for a wide range of misconduct proscribed by law.

Medieval and early modern Europe retained expansive lists of capital crimes and notably expanded the forms of execution beyond the common ancient practices of stoning, crucifixion, drowning, beating to death, or poisoning. In the Middle Ages both secular and ecclesiastical authorities participated in executions deliberately designed to be torturous and brutal, such as beheading, burning alive, drawing and quartering, hanging, disemboweling, using the rack, using thumb-screws, pressing with weights, boiling in oil, publicly dissecting, and castrating. Such brutality was conducted publicly as spectacle and ritual—an important or even essential element of capital punishment was not only the death of the accused, but the public process of killing and dying on display. Capital punishment was varied in its severity by the spectrum of torturous ways by which the offender’s death was eventually effected by political and other penal authorities.

In “the new world” the American colonies’ use of the death penalty was influenced more by Britain than by any other nation. The “Bloody Code” of the Elizabethan era included over 200 capital crimes, and the American colonies followed England in using public, ritualized hangings as the common form of execution. Until the mid-18 th century, the colonies employed elaborate variations of the ritual of execution by hanging, even to the point of holding fake hangings. Stuart Banner summarizes the early American practices:

Capital punishment was more than just one penal technique among others. It was the base point from which all other kinds of punishment deviated. When the state punished serious crime, most of the methods …were variations on execution. Officials imposed death sentences that were never carried out, they conducted mock hangings…, and they dramatically halted real execution ceremonies at the last minute. These were methods of inflicting a symbolic death …. Officials also wielded a set of tools capable of intensifying a death sentence – burning at the stake, public display of the corpse, dismemberment and dissection – ways of producing a punishment worse than death. (54)

In early America “capital punishment was not just a single penalty,” but “a spectrum of penalties with gradations of severity above and below an ordinary execution” (Banner, 86).

The late 18th century brought a “dramatic transformation of penal thought and practice” that was international in scope (Banner, 89). The dramatic change came with the birth of publicly supported prisons or penitentiaries that allowed extended incarceration for large numbers of people (Banner, 99). Before prisons and the practical possibility of lengthy incarceration as an alternative, “the only available units of measurement for serious crime were degrees of deviation from an ordinary execution” (Banner, 70). After the invention of prisons, for serious crimes there was now an alternative to capital punishment and to the practiced spectrum of torturous executions: prisons allowed varying conditions of confinement (for example, hard labor, solitary confinement, loss of privacy) and a temporal measure, at least, for distinguishing degrees of punishment to address kinds of serious misconduct. Dramatic changes for capital punishment also came with the 1864 publication in Italy of Cesare Beccaria’s essay, “On Crimes and Punishments.” Very influential in Europe and the United States, Beccaria’s sustained, philosophic investigation of the death penalty challenged both the authority of the state to punish by death and the utility of capital punishment as a superior deterrent to lengthy imprisonment. Philosophic defenses of the death penalty, like that of Immanuel Kant, opposed reformers and others, who, like Beccaria, argued for abolition of capital punishment. During the 19th century the methods of execution were made less brutal and the number of capital crimes was much reduced compared to earlier centuries of practice. Discussions of the death penalty’s merits invoked divergent understandings of the aims of punishment in general and thus of capital punishment in particular.

By the mid-20th century, two developments prompted another period of focused philosophic attention to the death penalty. In the United States a series of Supreme Court cases challenged whether the death penalty falls under the constitutional prohibition of “cruel and unusual punishments,” including questions about the legal and moral import of a criminal justice process that results in mistakes, caprice, or racial discrimination in capital cases. Capital punishment also became a global concern with the post-World War II Nuremberg trials of Nazi leaders and after the 1948 Declaration of Universal Human Rights and subsequent human rights treaties explicitly accorded all persons a right to life and encouraged abolishing the death penalty worldwide. Most nations have now abolished capital punishment, with notable exceptions including China, North Korea, Japan, India, Indonesia, Egypt, Somalia, and the United States, the only western “industrialized” nation still retaining the death penalty.

b. Philosophic Frameworks and Approaches

Capital punishment is often explored philosophically in the context of more general theories of “the standard or central case” of punishment as an institution or practice within a structure of legal rules (Hart, “Prolegomenon,” 3-5). The philosopher’s interest in the death penalty, then, is embedded in broader issues about the moral permissibility of punishment . Any punishment – and certainly an execution – intentionally inflicts on a person significant pain, suffering, unpleasantness, or deprivation that it is ordinarily wrong for an authority like the state to impose. What conditions or considerations, if any, would morally justify such penal practices? Following a framework famously offered by H.L.A. Hart,

[w]hat we should look for are answers to a number of different questions such as: What justifies the general practice of punishment? To whom may punishment be applied? How severely may we punish? (“Prolegomenon,” 3)

These different questions are, respectively, about the general justifying aim of punishment, about the conditions of responsibility for criminal conduct and liability to punishment, and about the amount, kind, or form of punishment justifiable to address actual or supposed misconduct. It is the last of these questions of justification – about the justified amount, kind, or form of punishment – that is foremost in philosophic approaches to the death penalty. Almost all modern and recent discussions of capital punishment assume liability for the death penalty is only for the gravest of crimes, such as murder; almost all assume comparatively humane modes of execution and largely ignore considering obviously torturous or brutal killings of offenders; and it is assumed that some amount of punishment is merited for murderers. The central question, then, is not often whether punishing murderers is morally justifiable (rather than rehabilitation or release, for example), but whether it is morally justifiable to punish by death (rather than by imprisonment, for example) those found to have committed a grave offense, such as murder. Responses to this question about the death penalty often build on more general principles or theories about the purposes of punishment in general, and about general criteria for determining the proper measure or amount of punishment for various crimes.

Among philosophers there are typically identified two broadly different ways of thinking about the moral merits of punishment in general, and whether capital punishment is a proper amount of punishment to address serious criminal misconduct (see “ Punishment ”). Justifications are proposed either with reference to forward-looking considerations, such as various future effects or consequences of capital punishment, or with reference to backward-looking considerations, such as facets of the wrongdoing to be punished. The latter approach, if dominant, has, since the 1930s, been called ‘retributivism’; retributivist justifications “look back” to the offense committed in order to link directly the amount, kind, or form of punishment to what the offense merits as penal response. This linkage is often characterized as whether a punishment “fits” the crime committed. For retributivists, any beneficial effects or consequences of capital punishment are wholly irrelevant or distinctly secondary. Forward-looking justifications of punishment have been labeled ‘utilitarian’ since the 19th century and, since the mid-20th century, other versions are sometimes called ‘consequentialism’. Consequentialist or utilitarian approaches to the death penalty are distinguished from retributivist approaches because the former rely only on assessing the future effects or consequences of capital punishment, such as crime prevention through deterrence and incapacitation.

2. Retributivist Approaches

Retributivists approach justifying the amount of punishment for misconduct by “looking back” to aspects of the wrongdoing committed. There are many different versions of retributivism; all maintain a tight, essential link between the offense voluntarily committed and the amount, form, or kind of punishment justifiably threatened or imposed. Future effects or consequences, if any, are then irrelevant or distinctly secondary considerations to justifying punishments for misconduct, including the death penalty. Retributivism about capital punishment often prominently appeals to the principle of lex talionis , or “the law of retaliation,” an idea popularly familiarized in the ancient and biblical phrase, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” Forms of retributivism vary according to their interpretation of lex talionis or in their appealing to alternative moral notions, such as basic moral rights or a principle of fairness.

a. Classic Retributivism: Kant and lex talionis

A classic expression of retributivism about capital punishment can be found in a late 18th century treatise by Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysical Elements of Justice (99-107; Ak. 331-337). After dismissing Cesare Beccaria’s abolitionist stance and reliance on “sympathetic sentimentality and an affectation of humanitarianism,” Kant appeals to an interpretation of lex talionis , what he calls “ jus talionis ” or “the Law of Retribution,” as justifying capital punishment:

Judicial punishment… must in all cases be imposed on him only on the ground that he committed a crime.… He must first be found deserving of punishment… The law concerning punishment is a categorical imperative. (100; Ak. 331) What kind and degree of punishment does public legal justice adopt as its principle and standard? None other than the principle of equality…. Only the Law of Retribution ( jus talionis ) can determine exactly the kind and degree of punishment (101; Ak. 332).

Kant then explicitly applies these principles to determine the punishment for the most serious of crimes:

If… he has committed a murder, he must die. In this case, there is no substitute that will satisfy the requirements of legal justice. There is no sameness of kind between death and remaining alive even under the most miserable conditions, and consequently there is also no equality between the crime and retribution unless the criminal is judicially condemned and put to death (102; Ak. 333).

Kant then employs a hypothetical case to insist that any social effects of the death penalty, good or bad, are wholly irrelevant to its justification:

Even if a civil society were to dissolve… the last murderer in prison would first have to be executed so that each should receive his just deserts and that the people should not bear the guilt of a capital crime… [and] be regarded as accomplices in the public violation of justice (102; Ak. 333).

So, even if social effects are not possible, since the society no longer exists, the death penalty is justified for murder. Kant exemplifies a pure retributivism about capital punishment: murderers must die for their offense, social consequences are wholly irrelevant, and the basis for linking the death penalty to the crime is “the Law of Retribution,” the ancient maxim, lex talionis , rooted in “the principle of equality.”

The key to Kant’s defense of capital punishment is “the principle of equality,” by which the proper, merited amount and kind of punishment is determined for crimes. Whether the best interpretation of Kant or not, the idea behind this common approach seems to be that offenders must suffer a punishment equal to the victim’s suffering: “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth,” a life for a life. But as often noted, any literalism about lex talionis cannot work as a general principle linking crimes and punishments. It seems to imply that the merited punishment for rape is to be raped, for robbery to be stolen from, for fraud to be defrauded, for assault to be assaulted, for arson to be “burned out,” etc. For other crimes—forgery, drug peddling, serial killings or massacres, terrorism, genocide, smuggling—it is not at all clear what kind or form of punishment lex talionis would then license or require (for example, Nathanson 72-75). As C. L. Ten succinctly says, “it would appear that the single murder is one of the few cases in which the lex talionis can be applied literally” (151). Both practical considerations and moral principles about permissible forms of punishment, then, ground objections to invoking a literal interpretation of lex talionis to justify capital punishment for murder.

Some retributivists employ a less literal way of employing a principle of equality to justify death as the punishment for murder. The relevant equivalence is one of harms caused and suffered: the murder victim suffers the harm of a life ended, and the only equivalent harm to be imposed as punishment, then, must be the death of the killer. As a general way of linking kinds of misconduct and proper amounts, kinds, or forms of punishment, this rendition of lex talionis also faces challenges (Ten, 151-154). Furthermore, it is also often noted that, even in the case of murder, there is no equivalence between the penal experience of capital offenders and their victims’ suffering in being murdered. Albert Camus, in his “Reflections on the Guillotine,” makes the point in a rather dramatic way:

But what is capital punishment if not the most premeditated of murders, to which no criminal act, no matter how calculated, can be compared? If there were to be a real equivalence, the death penalty would have to be pronounced upon a criminal who had forewarned his victim of the very moment he would put him to a horrible death, and who, from that time on, had kept him confined at his own discretion for a period of months. It is not in private life that one meets such monsters. (199)

This inequality of experience claim is even more to the point since even Kant maintains that “the death of the criminal must be kept entirely free of any maltreatment that would make an abomination of the humanity residing in the person suffering it” (102; Ak. 333).

b. Lex talionis as a Principle of Proportionality

Most contemporary retributivists interpret lex talionis not as expressing equality of crimes and punishments, but as expressing a principle of proportionality for establishing the merited penal response to a crime such as murder. The idea is that the amount of punishment merited is to be proportional to the seriousness of the offense, more serious offenses being punished more severely than less serious crimes. So, one constructs an ordinal ranking of crimes according to their seriousness and then constructs a corresponding ranking of punishments according to their severity. The least serious crime is then properly punished by the least severe penalty, the second least serious crime by the second least severe punishment, and so on. The gravest misconduct, then, is properly addressed by the most severe of punishments, death.

To carry out such a general project of constructing scales of crimes and matching punishments is a daunting challenge, as even many retributivists admit. Aside from these concerns, as a defense of capital punishment this approach to lex talionis simply raises the question about the morality of the death penalty, even for the most serious of crimes. There is no reason to think that current capital punishment practices are the most severe punishment. Consider medieval practices of death with torture, or death “with extreme prejudice”; and are there not possible conditions of confinement that are possibly more severe than execution, such as years of brutal, solitary confinement or excessively hard labor? Such punishments would not likely now be on a list of morally permissible penal responses to even the most serious crimes. But then what is needed is some justification for setting an upper bound of morally permissible severity for punishments, “a theory of permissibility” (Finkelstein, “A Contractarian Approach…,” 212-213). But whether today’s death penalty is morally permissible is precisely the question at issue. The retributivist proportionality interpretation of lex talionis simply assumes capital punishment is morally permissible, rather than offering a defense of it.

One general concern about appeals to lex talionis , under any interpretation, is that relying on “the law of retaliation” can appear to make capital punishment tantamount to justified vengeance. But Kant and other retributivist defenders of the death penalty rightly distinguish principled retribution from vengeance. Vengeance arises out of someone’s hatred, anger, or desires typically aimed at another: there is no internal limit to the severity of the response, except perhaps that which flows from the personal perspective of the avenger. The avenger’s response may be markedly disproportionate to the offense committed, whereas retributivists insist that the severity of punishments must be matched to the misconduct’s gravity. Vengeance is typically personal, directed at someone about whom the avenger cares—it is personal. Retribution requires responses even to injuries of people no one cares about: its impersonality makes harms to the friendless as weighty as harms to the popular and justifies punishment without regard to whether anyone desires the offender suffer. The avenger typically takes pleasure in the suffering of the offender, whereas “we may all deeply regret having to carry out the punishment” (Pojman, 23) or only take “pleasure at justice being done” (Nozick, 367) as a retributivist moral principle requires. Even if desires for vengeance are satisfied by executing murderers, for retributivists such effects are not at the heart of the defense of capital punishment. And to the extent that such satisfactions are sufficient justification, then the defense is no longer retributivist, but utilitarian or consequentialist (see sections 3 and 4). For retributivists the morality of the death penalty for murder is a matter of general moral principle, not assuaging any desires for revenge or vengeance on the part of victims or others.

c. Retributivism and the Right to Life

Some forms of retributivism about capital punishment eschew reliance on lex talionis in favor of other kinds of moral principles, and they typically depart from Kant’s conclusion that murderers must be punished by death, regardless of any consequences. One approach employs the idea of basic moral rights, such as the right to life, an expression of the value of life that seems to work against justifying capital punishment. Yet John Locke, for example, in his Second Treatise on Government , posits both a natural right to life and defends the death penalty for murderers. Echoing a line of reasoning exhibited in Thomas Aquinas’s defense of capital punishment ( Summa Theologiae II-II, Q. 64, a.2), Locke claims that a murderer violates another’s right to life, and thereby “declares himself… to be a noxious creature… and therefore may be destroyed as a lion or a tiger, one of those wild savage beasts… both to deter others from doing the like injury… and also to secure men from the attempts of a criminal” ( Treatise , sections 10-11). For Locke, murderers have, by their voluntary wrongdoing, forfeited their own right to life and can therefore be treated as a being not possessing any right to life at all and as subject to execution to effect some good for society.

This retributivist position notably departs from Kant’s extreme view in concluding only that a murderer may be put to death, not must be, and by invoking utilitarian thinking as a secondary consideration in deciding whether capital punishment is morally justified for murderers who have forfeited their right to life. This form of retributivism—rights forfeiture and considering consequences of the death penalty—is also explicitly expressed by W. D. Ross in his 1930 book, The Right and the Good :

But to hold that the state has no duty of retributive punishment is not necessarily to adopt a utilitarian view of punishment.… [T]he main element in any one’s right to life or property is extinguished by his failure to respect the corresponding right in others.… [T]he offender, by violating the life or liberty or property of another, has lost his own right to have his life, liberty, or property respected, so that the state has no prima facie duty to spare him as it has a prima facie duty to spare the innocent. It is morally at liberty to injure him as he has injured others, or to inflict any lesser injury on him, or to spare him, exactly as consideration of both of the good of the community and of his own good requires. (60-61)

The retributivist argument, then, is that murderers forfeit their own right to life by virtue of voluntarily taking another’s life. Since a right to life, like other rights, logically entails a correlative duty of others (see Consequentialism and Ethics, section 2b ), by forfeiting their right to life murderers eliminate the state’s correlative duty not to kill them; the murderer’s forfeiture makes morally permissible the state’s putting them to death, at least as a means to some good. Thus, capital punishment is not a violation of an offender’s right to life, as the offender has forfeited that right, and the death penalty is then justifiable as a morally permissible way to treat murderers in order to effect some good for society.

This kind of retributivist approach to capital punishment raises philosophic issues, aside from its reliance on empirical claims about the effects of the death penalty as a way to deter or incapacitate offenders (see section 3b). First, though the idea of forfeiting a right may be familiar, it leaves “troubling and unanswered questions: To whom is it forfeited? Can this right, once forfeited, ever be restored? If so, by whom, and under what conditions” (Bedau, “Capital Punishment,” 162-3)? Second, given that the right to life is so fundamental to all rights and, as many maintain, held equally by each and all because they are humans, perhaps the right to life is exceptional or even unique in not being forfeitable at all: the right to life is actually a fundamental natural or human right. One’s actions cannot and do not alter one’s status as a human being, Locke and Aquinas notwithstanding; thus, the right to life is inalienable and not forfeitable. Even killers retain their right to life, the state remains bound by the correlative duty not to kill a murderer, and capital punishment, then, is a violation of the human right to life.

Developed in this way, as a matter of fundamental human rights, the merit of capital punishment becomes more about the moral standing of human beings and less about the logic and mobility of rights through forfeiture or alienation. The point of a human right to life is that it “draws attention to the nature and value of persons, even those convicted of terrible crimes.… Whatever the criminal offense, the accused or convicted offender does not forfeit his rights and dignity as a person” (Bedau, “Reflections,” 152, 153). This view reflects at least the spirit of the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights: the right to life is universal, is rooted in each person’s dignity, and is unalienable (Preamble; Article 3). But this view of offenders’ moral standing can be challenged if one considers the implication that, of equal standing with any of us, then, are masters of massacres or genocide (for example, Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot), serial killers, terrorists, rampant rapists, and pedophiliac predators. As one retributivist defender of capital punishment puts it, “though a popular dogma, the secular doctrine that all human beings have… worth is groundless. The notion… [is] perhaps the most misused term in our moral vocabulary.… If humans do not possess some kind of intrinsic value… then why not rid ourselves of those who egregiously violate… our moral and legal codes” (Pojman, 35, 36).

d. Retributivism and Fairness

A recently revived retributivism about the death penalty builds not on individual rights, but on a notion of fairness in society. Given a society with reasonably just rules of cooperation that bestow benefits and burdens on its members, misconduct takes unfair advantage of others, and punishment is thereby merited to address the advantage gained:

A person who violates the rules has something that others have—the benefits of the system—but by renouncing what others have assumed, the burdens of self-restraint, he has acquired an unfair advantage. Matters are not even until this advantage is in some way erased….[P]unishing such individuals restores the equilibrium of benefits and burdens. (Morris 478)

The morally justified amount, kind, or form of punishment for a crime is then determined by an “unfair advantage principle”:

His crime consists only in the unfair advantage… [taken] by breaking the law in question. The greater the advantage, the greater the punishment should be. The focus of the unfair advantage principle is on what the criminal gained.” (Davis 241)

In justifying an amount of punishment, then, an unfairness principle focuses on the advantage gained, whereas the lex talionis principle attends to the harm done to another (Davis 241).

The fairness approach to punishment reflects recent uses of “the principle of fairness” as a theory of political obligation: those engaged in a mutually beneficial system of cooperation have a duty to obey the rules from which they benefit (Rawls, 108-114). As applied to punishment, though, its roots run also to ancient, archaic notions of justice as re-establishing an equilibrium, to Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics treatment of justice as requiring state corrective action to rectify the imbalances created by criminal misconduct (Book V, Chapter 4), and to G.W.F. Hegel’s claim in The Philosophy of Right that to punish “is to annul the crime… and to restore the right” (69, 331n). Today’s popular parlance that punishment is how offenders pay for their crimes can also be seen as their paying for unfair advantages gained.

As a general approach to justifying the amount of punishment merited for misconduct, the fairness approach initially appears to work best for petty theft or possibly “free-loading” in cooperative schemes, such as penalizing tax evasion. In such cases one can perhaps see unfair advantage gained and see the amount of punishment as tied to what is unfairly gained. But for violent crimes such as murder, the fairness approach seems less plausible. How does lengthy incarceration or even execution erase the unfair advantage gained, annul the crime, or re-establish any prior balance between perpetrator and victim? To the extent that punishment affects such things, it risks conflating retribution with restitution or restoration. The unfair advantage principle also characterizes the wrong committed not in terms of its effects on a victim, but on third parties—society members who exercise self-restraint by obeying those norms the offender violates. This oddly places the victim of criminal misconduct, especially for violent crimes: the person assaulted or killed is not the focus in justifying the amount of punishment, but third parties’ burdens of self-restraint are. Additionally, taken by itself, the unfair advantage approach to establishing the proper amount of punishment can also have some odd consequences, as Jeffrey Reiman rather colorfully suggests:

For example, it would seem that the value of the unfair advantage taken of law-obeyers by one who robs a great deal of money is greater than the value of the unfair advantage taken by a murderer, since the latter gets only the advantage of ridding his world of a nuisance while the former will be able to make a new life… and have money left over for other things. This leads to the counterintuitive conclusion that such robbers should be punished more severely… than murderers. (“Justice, Civilization,…,” note 10)

The death penalty for murder, then, would not obviously be morally justified if the general criterion for the amount of punishment is an unfair advantage principle.

A defense of the death penalty for murder has been proposed by employing another version of this general approach to punishment. The key is seeing the kind of unfair advantage gained by a murderer. As Reiman suggests in the spirit of Hegelian retributivism, the act of killing another disrupts “the relations appropriate to equally sovereign individuals;” it is “an assault on the sovereignty of an individual that temporarily places one person (the criminal) in a position of illegitimate sovereignty over another (the victim)”; then there is “the right to rectify this loss of standing relative to the criminal by meting out a punishment that reduces the criminals’ sovereignty to the degree to which she vaunted it above her victim’s” (“Why…,” 89-90). So, if a murder is committed and a life taken, the idea is that the amount of permissible punishment is for the state, as the victim’s agent, to assert a supremacy over the criminal similar to that already asserted by the killer; and to do that it is permissible for the state to impose the death penalty for murder. So, on this interpretation of the fairness principle, the death penalty for murder is morally justified, though, for other crimes, it may not be “easy or even always possible to figure out what penalties are equivalent to the harms imposed by offenders” (Reiman, “Why…,” 69-90, 93). As with other forms of retributivism, the fairness approach, on either interpretation, is challenged by the plausibility of using a principle that adequately addresses both the merits of capital punishment for murder and also generates a system of penalties that “fit” or are equivalent to various crimes.

e. Challenges to Retributivism

Retributivist approaches to capital punishment are many and varied. But from even the small sample above, notable similarities are often cited as challenges for this way of thinking about the moral justification of punishment by death. First, retributivism with respect to capital punishment either invokes principles that are plausible, if at all, only for death as penalty for murder; or it relies on principles met only with reasoned skepticism about their general adequacy for constructing a plausible scale matching various crimes with proper penal responses.

Second, retributivists presuppose that persons are responsible for any criminal misconduct for which they are to be punished, but actually instituting capital punishment confronts the reality of some social conditions, for example, that challenge the presupposition of voluntariness and, in the case of the fairness approach, that challenge the presupposition of a reasonably just system of social cooperation (see section 5b). Third, it is often argued that, in addressing the moral merits of capital punishment, retributivists ignore or make markedly secondary the causal consequences of the practice. What if no benefits accrue to anyone from the practice of capital punishment? What if capital punishment significantly increases the rate of murders or violent crimes? What if the institution of capital punishment sometimes, often, or inevitably is arbitrary, capricious, discriminatory, or even mistaken in its selecting those to be punished by death (see section 5)? These and other possible consequences of capital punishment seem relevant, even probative. The challenge is that retributivists ignore or diminish their importance, perhaps defending or opposing the death penalty despite such effects and not because of them.

3. Utilitarian Approaches

A utilitarian approach to justifying capital punishment appeals only to the consequences or effects of death being the penalty for serious crimes, such as murder. A utilitarian approach, then, is a kind of consequentialism and is often said to be “forward looking,” in contrast to retributivists’ “backward looking” approach. More specifically, a utilitarian approach sees punishment by death as justified only if that amount of punishment for murder best promotes the total happiness, pleasure, or well-being of the society. The idea is that the inherent pain and any negative effects of capital punishment must be exceeded by its beneficial effects, such as crime prevention through incapacitation and deterrence; and furthermore, the total effects of the death penalty—good and bad, for offender and everyone else—must be greater than the total effects of alternative penal responses to serious misconduct, such as long-term incarceration. A utilitarian approach to capital punishment is inherently comparative in this way: it is essentially tied to the consequences of the practice being best for the total happiness of the society. It follows, then, that a utilitarian approach relies on what are, in principle, empirical, causal claims about the total marginal effects of capital punishment on offenders and others.

a. Classic Utilitarian Approaches: Bentham, Beccaria, Mill

A classic utilitarian approach to punishment is that of Jeremy Bentham. In chapters XIII and XIV of his lengthy work, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation , first published in 1789, Bentham addresses the appropriate amount of punishment for offenses, or, as he puts it, “the proportion between punishments and offences.” He begins with some fundamental features of a utilitarian approach to such issues:

The general object which all law have, or ought to have in common, is to augment the total happiness of the community.… But all punishment is mischief: all punishment in itself is evil. Upon the principle of utility, if it ought at all to be admitted, it ought only to be admitted in as far as it promises to exclude some greater evil. (XIII. I, ii.)

Bentham continues by noting the importance of attending to “the ends of punishment”:

The immediate principal end of punishment is to control action.… [T]hat of the offender it controls by its influence… on his will, in which case it is said to operate in the way of reformation ; or on his physical power, in which case it is said to operate by disablement : that of others it can influence no otherwise than by its influence over their wills; in which case it is said to operate in the way of example . (XIII. ii. fn. 1)

So, there are three major ends of punishment related to controlling people’s action in ways promoting the total happiness of the community through crime reduction or prevention: reformation of the offender, disablement (that is, incapacitation) of the offender, and deterrence (that is, setting an example for others). Of these three ends of punishment, Bentham says “example” – or deterrence – “is the most important end of all.” (XIII. ii. fn 1). Since “all punishment is mischief [and] an evil,” any amount of punishment, then, is justified only if that mischief is exceeded by the penalty’s good effects, and, most importantly for Bentham, only if the punishment reduces crime by deterring others from misconduct and does so better than less painful punishments. In other writings, Bentham explicitly applies his utilitarian approach to capital punishment, first allowing its possible justification for aggravated murder, particularly when the “effect may be the destruction of numbers” of people, and then, years later and late in life, calling for its complete abolition (Bedau, “Bentham’s Utilitarian Critique…”).

In his own writing about law, Bentham notably praises and acknowledges Cesare Beccaria’s On Crimes and Punishments , its utilitarian approach to penal reform, and its call for abolishing capital punishment. Beccaria called for abolition of the death penalty largely by appealing to its comparative inefficacy in reducing the crime rate. In Chapter XII of his essay, Beccaria says the general aim of punishment is deterrence and that should govern the amount of punishment to be assigned crimes:

The purpose of punishment… is nothing other than to dissuade the criminal from doing fresh harm to his compatriots and to keep other people from doing the same. Therefore, punishments and the method of inflicting them should be chosen that… will make the most effective and lasting impression on men’s minds and inflict the least torment on the body of the criminal. (23; Ch. XII)

He then argues that “capital punishment is neither useful nor necessary” in comparison to the general deterrent effects of lengthy prison sentences:

[T]here is no one who, on reflection, would choose the total and permanent loss of his own liberty, no matter how advantageous a crime might be. Therefore, the intensity of a sentence of servitude for life, substituted for the death penalty, has everything needed to deter the most determined spirit.… With capital punishment, one crime is required for each example offered to the nation; with the penalty of a lifetime at hard labor, a single crime affords a host of lasting examples” (49-50, 51; Ch. XXVIII).

The idea here is that an execution is a single, severe event, perhaps not long remembered by others, whereas life imprisonment provides a continuing reminder of the punishment for misconduct. In general, Beccaria says, “[i]t is not the severity of punishment that has the greatest impact on the human mind, but rather its duration, for our sensibility is more easily surely stimulated by tiny repeated impressions than by a strong but temporary movement” (49; Ch. XXVIII).

Beccaria adds to this thinking at least two claims about some bad social effects of capital punishment: first, for many the death penalty becomes a spectacle, and for some it evokes pity for the offender rather than the fear of execution needed for effective deterrence of criminal misconduct (49; Ch. XXVIII). Second, “capital punishment is not useful because of the example of cruelty which it gives to men.… [T]he laws that moderate men’s conduct ought not to augment the cruel example, which is all the more pernicious because judicial execution is carried out methodically and formally” (51; Ch. XXVIII). Thus, Beccaria opposes capital punishment by employing utilitarian thinking: the primary benefit of deterrence is better achieved through an alternative penal response of “a lifetime at hard labor,” and, furthermore, the cruelty of the death penalty affects society in ways much later called “the brutalization effect.”

Another major utilitarian, John Stuart Mill, also exemplifies distinctive facets of a utilitarian approach, but in defense of capital punishment. In an 1868 speech as a Member of Parliament, Mill argues that capital punishment is justified as penalty for “atrocious cases” of aggravated murder (“Speech…,” 268). Mill maintains that the “short pang of a rapid death” is, in actuality, far less cruel than “a long life in the hardest and most monotonous toil… debarred from all pleasant sights and sounds, and cut off from all earthly hope” (“Speech…,” 268). As Sorell succinctly summarizes Mill’s position, “hard labor for life is really a more severe punishment than it seems, while the death penalty seems more severe than it is” (“Aggravated Murder…,” 204). Since the deterrent effect of a punishment depends far more on what it seems than what it is, capital punishment is the better deterrent of others while also involving less pain and suffering for the offender. Such a combination “is among the strongest recommendations a punishment can have” (Mill, “Speech…,” 269). And so, Mill says, “I defend [the death penalty] when confined to atrocious cases… as beyond comparison the least cruel mode in which it is possible adequately to deter from the crime” (“Speech…, 268).

b. Empirical Considerations: Incapacitation, Deterrence

A utilitarian approach to capital punishment depends essentially on what are, in fact, the causal effects of the practice, whether the death penalty is, in fact, effective in incapacitating or deterring potential offenders. If, in fact, it does not effect these ends better than penal alternatives such as lengthy incarceration, then capital punishment is not justified on utilitarian grounds. In principle, at least, the comparative efficacy of capital punishment is therefore an empirical issue.

A number of social scientific studies have been conducted in search of conclusions about the effects of capital punishment, at least in America. With respect to the end of incapacitation, any crime prevention benefit of executing murderers depends on recidivism rates, that is, the likelihood that murderers again kill. Recent studies of convicted murderers—death row inmates not executed, prison homicides, parolees, and released murderers—indicate that the recidivism rate is quite low, but not zero: a small percentage of murderers kill again, either in prison or upon release (Bedau, The Death Penalty , 162-182). These crimes, of course, would not have occurred were capital punishment imposed, and, so, the death penalty does prevent commission of some serious crimes. On the other hand, for a utilitarian, these benefits of incapacitation through execution must exceed those for possible punitive alternatives. The data reflects recidivism rates under current practices, not other possible alternatives. If, for example, pardons and commutations were eliminated for capital crimes, if atrocious crimes were punished by a life sentence without any possibility of parole, or if conditions of confinement were such that prison murders were not possible (for example, shackled, solitary confinement for life), then the recidivism rate might approach or be zero. One issue, then, is how high or low a recidivism rate decides the justificatory issue for capital punishment. Another issue is the moral permissibility of establishing conditions of confinement so restrictive that even murders in prison are reduced to nearly zero.

Since the mid-twentieth century, in America a number of empirical studies have been conducted in order to assess the deterrent effects of capital punishment in comparison to those of life imprisonment. Scholars analyzed decades of data to compare jurisdictions with and without the death penalty, as well as the effects before and after a jurisdiction abolished or instituted capital punishment. Such analyses “do not support the deterrence argument regarding capital punishment and homicide” (Bailey, 140). Sophisticated statistical studies published in the mid-1970s claimed to show that each execution deterred seven to eight murders. This exceptional study and its methodology have been much criticized (Bailey, 141-143). Additional, more recent studies and analyses have “failed to produce evidence of a marginal deterrent effect for capital punishment” (Bailey, 155). As indicated by Jeffrey Reiman’s succinct summary and numerous, cited literature surveys (“Why…” 100-102), nearly all relevant experts claim there is no conclusive evidence that capital punishment deters murder better than substantial prison sentences.

Determining the deterrent effects of capital punishment does present significant epistemic challenges. In comparative studies of jurisdictions with and without the death penalty, “there simply are too many variables to be controlled for, including socio-economic conditions, genetic make-up,” demographic factors (for example, age, population densities), varying facets of law enforcement, etc. (Pojman, 139). Numerous variables may or may not explain the data attempting to link crime rates and the death penalty in different places or times (Pojman, 139). Second, as Beccaria notes, for example, deterrent effects plausibly depend importantly on the certainty, speed, and public nature of penal responses to criminal conduct. These factors have not been much evident in recent capital punishment practices in America, which may explain the lack of evidence revealed by recent statistical studies. Third, deterrence is a causal concept: the idea is that potential murderers do not kill because of the death penalty. So, the challenges are to measure what does not occur—murders – and to establish what causes the omission—the death penalty. The latter element is even more challenging to measure because most who do not murder do so out of habit, character, religious beliefs, lack of opportunity, etc., that is, for reasons other than any perceived threat or fear of execution by the state. Deterrence studies, then, attempt to establish empirically a causal relationship for a small minority of people and omitted homicides within a death penalty jurisdiction. Finally, there are disagreements about the importance of the studies’ conclusions. For example, abolitionists typically see that, despite numerous attempts, the failure to provide conclusive evidence strongly suggests there is no such effect: the death penalty, in fact, does not deter. Defenders of capital punishment are inclined to interpret the empirical studies as being inconclusive: it remains an open question whether the death penalty deters sufficiently to justify it. And all this is further complicated by the fact that some studies focus on the effects of capital statutes and others look for links between actual executions and crime rates.

c. Utilitarian Defenses: “Common Sense” and “Best Bet”

Regardless of the outcomes or probative value of statistical studies, justifying capital punishment on grounds of deterrence may still have merit. It would seem, some maintain, that “common sense” supports the notion that the death penalty deters. The deterrence justification of capital punishment presupposes a model of calculating, deliberative rationality for potential murderers. What people cherish most is life; what they most fear is being killed. So, given a choice between life in prison and execution by the state, most people much prefer life and therefore will refrain from misconduct for which death is the punishment. In short, “common sense” suggests that capital punishment does deter. But this kind of appeal to “common sense” ignores the essentially comparative aspect of appeals to deterrence as justification: though capital punishment may deter, it may not deter any more (or significantly more) than a long life in prison. We cannot equate “what is most feared” with “what most effectively deters” (Conway, 435-436; Reiman, “Why…,” 102-106).

Another way of looking at capital punishment in terms of deterrence relies on making the best decision under conditions of uncertainty. Given that the empirical evidence does not definitively preclude that capital punishment is a superior deterrent, “the best bet” is to employ the death penalty for serious crimes such as murder. If capital punishment is not, in fact, a superior deterrent, then some murderers have been unnecessarily executed by the state; if, on the other hand, death is not a possible punishment for murder and capital punishment is, in fact, a superior deterrent, then some preventable killings of innocent persons would occur. Given the greater value of innocent lives, the less risky, better option justifies capital punishment on grounds of deterrence. But the argument crucially depends on comparative risk assessments: if there is capital punishment, then certainly some murderers will be killed, whereas without the death penalty there is only a remote chance that more innocent lives would be victims of murder (Conway, 436-443). Furthermore, the argument openly assumes that not all lives are equal—those of the innocent are not to be risked as much as those who have murdered—and that, for some, is a fundamental moral issue at stake in justifying capital punishment (see section 2c; Pojman, 35-36).

d. Challenges to Utilitarianism

Utilitarian approaches to justifying punishment are controversial and problematic, perhaps most often with respect to possibly justifying punishment of the innocent as a means to preventing crime and promoting total happiness of a society. Even ignoring this issue and focusing only on justifying the proper amount of punishment for the guilty and the death penalty, in particular, there are concerns to be considered about a utilitarian approach. The objection is that a utilitarian approach to the death penalty relies on a suspect general criterion—deterrence—for establishing the proper amount of punishment for crimes. It is often argued that, for purposes of crime prevention through deterrence, a utilitarian is committed, at least in principle, to excessively severe punishments, such as torturous and gruesome executions in public even for crimes much less serious than murder (for example, Ten, 34-35, 143-145). The idea is that the pain of excessively severe and public punishments for minor crimes is more than counterbalanced by a significant reduction in a crime rate. It is also argued that significant crime rate reductions could perhaps be achieved, in some circumstances, by disproportionately minor punishments: if fines, light prison sentences, or even fake executions could deter as well as actual ones, then a utilitarian is committed to disproportionately mild penalties for grave crimes. Utilitarians respond to such possibilities by indicating additional considerations relevant to calculating the total costs of such disproportionate punishments, while critics continue creating even more elaborate, fantastic counterexamples designed to show the utilitarian approach cannot always avoid questions about the upper or lower limits of morally permissible penal responses to misconduct. As C. L. Ten summarizes succinctly, a utilitarian approach establishing a proper amount of punishment is “inadequate to account for both the strength of the commitment to the maintenance of a proportion between crime and punishment, and [to] the great reluctance to depart… from that proportion when required to so do by purely aggregative consequential considerations” (146).

Another common criticism of the utilitarian approach points to the very structure of justifications rooted in deterrence. As evident in Bentham’s classic statements, for example, the purpose of punishment “is to control action,” primarily through deterrence (see section 3a). Punishments deter and “control action” by example, by the demonstration to others that they, too, will suffer similarly should they similarly misbehave. Capital punishment, then, aims to deter actions of potential killers by inflicting death on actual ones: the technique works by threat, by instilling fear in others. A fundamental objection to this way of thinking is to see that, in effect, persons are being used as a means to controlling others’ actions; capital offenders are being used simply as a means to deter others and reduce the crime rate. Such a use of persons is morally impermissible, it is argued, echoing Immanuel Kant’s famous categorical imperative against treating any person merely as means to an end. No gain in deterrence, incapacitation, or other beneficial effects can justify deliberately killing a captive human being as a means to even such desirable ends as deterring others from committing grave crime. The argument, then, is that justifying capital punishment on grounds of deterrence is a morally impermissible way to treat persons, even those found to have committed atrocious crimes.

e. Other Consequential Considerations

In discussions of capital punishment, it is deterrence that receives much of the attention for those exploring a utilitarian approach to the moral justification of the practice. There are, however, other significant consequences of the death penalty that are relevant, as noted even by classic utilitarians. Beccaria, for example, asserts a brutalization effect on society: executions are cruel and are examples to others of the states’ cruelty. The suggestion seems to be that capital punishment increases people’s tolerance for another’s suffering, their callousness about human suffering, a willingness to impose suffering on another, even the rate of violent crimes (for example, assaults or homicides). In contrast, one recent defender of the death penalty, Jeffrey Reiman, argues that, for some developed societies, abolition of capital punishment for serious crimes shows restraint and thereby actually advances civilization by reducing our tolerance for others’ suffering. Such claims are, in principle, empirical ones about the causal effects of the practice of capital punishment. As with recent deterrence studies, there is no clear empirical evidence of any brutalizing or civilizing effects of capital punishment.

For classic utilitarian thinking, another important consequence of punishment is its effect on the offender. According to Jeremy Bentham, one of the three ends of punishment is reform of the offender through “its influence on his will” (XIII.ii. fn. 1). This penal aim of reform (or rehabilitation) may suggest capital punishment is not justifiable for any crime. But that need not be the case. The ancient Roman Stoic Seneca, for example, argues that proper punishment for criminal misconduct depends on its “power to improve the life of the defendant” (Nussbaum, 103). But he also defends capital punishment as a kind of merciful euthanasia: execution is “in the interest of the punished, given that a shorter bad life is better than a longer one” (Nussbaum, 103, note 43). Plato also defends capital punishment by looking to its impact on the offender. In his later works and as part of a general theory of penology, Plato maintains that the primary penal purpose is reform—to “cure” offenders, as he says. For crimes that show offenders are “incurable,” Plato argues execution is justifiable. In his late work, The Laws, Plato explicitly prescribes capital punishment for a wide range of offenses, such as deliberate murder, wounding a family member with the intent to kill, theft from temples or public property, taking bribes, and waging private war, among others (MacKenzie; Stalley). In a utilitarian approach to capital punishment, then, attending to the end of reforming offenders need not be irrelevant to possible moral justifications of the death penalty.

4. Capital Punishment as Communication

A cluster of distinctive approaches to issues of justifying punishment and, at least by implication, the death penalty, are united by taking seriously the idea of punishment as expression or communication. Often called “the expressive theory of punishment,” such approaches to punishment are sometimes classified as utilitarian or consequentialist, sometimes as retributivist, and sometimes as neither. The root idea is that punishment is more than “the infliction of hard treatment” by an authority for prior misconduct; it is also “a conventional device for the expression of attitudes of resentment and indignation, and of judgments of disapproval and reprobation…. Punishment, in short, has a symbolic significance ” (Feinberg, “The Expressive Function…,” 98). Hard treatment, deprivations, incarceration, or even death can be, and perhaps are, vehicles by which messages are communicated by the community. To see capital punishment as a deterrent is to see it as communicative: the death penalty communicates to the community—at least potential killers—that murder is a serious wrong and that execution awaits those who kill others. Various developments of punishment as communication, though, attend to other messages expressed, some emphasizing the sender and others the recipient of the message.

One version of this kind of approach emphasizes that, with capital punishment, a community is expressing strong disapproval or condemnation of the misconduct. Sometimes called “the denunciation theory,” the basic contention is evident in Leslie Stephens’ late 19th-century work, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (a reply to J.S. Mill’s On Liberty ), as well as by the oft-quoted remarks of Lord Denning recorded in the 1953 Report of the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment :

The punishment for grave crimes should adequately reflect the revulsion felt by the great majority of citizens for them. It is a mistake to consider the object of punishment as being deterrent or reformative or preventive and nothing else.… The ultimate justification of any punishment is not that it is a deterrent but that it is the emphatic denunciation by the community of a crime; and from this point of view, there are some murders which, in the… public opinion, demand the most emphatic denunciation of all, namely the death penalty. (As quoted in Hart, “Punishment…,” 170)

In the United States, Supreme Court decisions in death penalty cases have more than once employed such reasoning: a stable, ordered society is better promoted by capital punishment practices than risking “the anarchy of self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law” as ways of expressing communal outrage (Justice Stewart, in Furman v. Georgia (1972), as quoted in Gregg v. Georgia (1976)).

As a defense of capital punishment, at least, this “denunciation theory” leaves multiple questions not adequately addressed. For example, the approach presupposes some moral merit to popular sentiments of indignation, outrage, anger, condemnation, even vengeance or vindictiveness in response to serious misconduct. There are significant differences between expressing such emotions and punishing justly or morally (see section 2b). Secondly, the structure of the thinking seems entirely consequentialist or utilitarian: capital punishment is justified as effective means to communicate condemnation, or to satisfy others’ desires to see someone suffer for the crime, or as an outlet for strong, aggressive feelings that otherwise are expressed in socially disruptive ways. Such utilitarian reasoning would seem to justify executing pedophiles or even innocent persons in order to communicate condemnation or avoid an “anarchy of self-help, vigilante justice, and lynch law.” On the other hand, even Jeremy Bentham argues that “no punishment ought to be allotted merely to this purpose” because such widespread satisfactions or pleasures cannot ever “be equivalent to the pain… produced by punishment” (Bentham XIII. ii. fn. 1). Third, it leaves unanswered why the expression of communal outrage—even if morally warranted—is best or only accomplished through capital punishment. Why would not harsh confinement for life serve as well any desirable expressive, cathartic function? Or on what grounds are executions not to be conducted in ways torturous and prolonged, even publicly, as means of better communicating denunciation and expressing society’s outrage about the offenders’ misconduct? And does not the death penalty also express or communicate other, conflicting messages about, for example, the value of life? As a justification of capital punishment, even for the most heinous of crimes, a “denunciation theory” faces significant challenges.