Case studies

.css-7qmtvr{overflow:hidden;max-height:108px;text-indent:0px;} How to train world-champion cardiologists

Gellér László, Zoltán Salló, Nándor Szegedi

Semmelweis University

A framework to teach library research skills

Anna Hvass, Karen Rolfe, Siân Furmage , Michael Latham

University of Southampton

Going for gold: how to craft a winning TEF submission

Emily Pollinger , Julian Chaudhuri

University of Bath

Creating an impactful social group for neurodivergent students

Brooke Szücs, Ben Roden-Cohen

The University of Queensland

Sharing qualitative research through open access

Nathaniel D. Porter

Virginia Tech

Using storybooks to share research with a wider audience

Dominic Petronzi , Dean Fido, Rebecca Petronzi

University of Derby

Making higher education accessible for students with unmet financial need

A food pantry can help support your campus through the cost-of-living crisis

Lauren Dinour, Fatima deCarvalho, Karina Escobar

Montclair State University

Nourishing bodies and minds: the vital role of a student food pantry

Isabelle Largen

Support for faculty on long-term leave is a career lifeline

Theresa Mercer , Jim Harris, Ron Corstanje, Chhaya Kerai-Jones

Cranfield University

Use design thinking principles to create a human-centred digital strategy

Joe Holland

University of Exeter

Film storytelling can enhance learning in STEM subjects

Arijit Mukhopadhyay

University of Salford

Creating safe spaces for students to talk about financial difficulties

Caroline Deylaud Koukabi, Joanna West

University of Luxembourg

How our Study Together programme promotes belonging and improves well-being

Gemma Standen

University of East Anglia

Use Etherpad to improve engagement in large transnational classes

Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University

How to harness community knowledge to tackle complex policy challenges

Saffron Woodcraft, Joseph Cook

University College London

What we learned from a pilot study aimed at getting first-generation students into pharmacy

Carl Harrington, Rosemary Norton

Fostering student co-creation to give back to the community

Martha Sullivan

How to keep first-generation students engaged throughout the academic year

Araceli Martinez , Athina Cuevas

Chapman University

We used a hybrid escape room to dramatically boost student attendance

Erick Purwanto, Na Li, Ting Ting Tay

A road map for advancing digital inclusion for your students, staff and community

Raheel Nawaz

Staffordshire University

Building trust in research: how effective patient and public involvement can help

Gary Hickey

Community organising: a case study in parent engagement

Michael Bennett

King’s College London

Designing 24/7 hubs for students

Kieron Broadhead

Using partnerships to establish and build on project success

Dominic Wood

Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM)

Case study: how to do an independent evaluation on homelessness on six continents

Suzanne Fitzpatrick

Heriot-Watt University

Embrace the chaos of real-world learning experiences

Jim Entwistle

Teesside University

Teaching business students how to prepare sustainability reports for SMEs

Ven Tauringana

How storytelling boosts environmental impact and engagement

Denise Baden

Bring the SDGs into the classroom through role play and gamification

Shelini Surendran, Kat Mack, Anand Mistry

University of Surrey

How to support international students’ smooth transition to a new country

Mengping Cheng

Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha | University of Canterbury

Dealing with abuse after public commentary

Michael Head, Larisa Yarovaya , Ashton Kingdon , Millie Downer

Messy decisions and creative science in the classroom

Charlotte Dodson, Steve Flower

Transforming the classroom through experiential learning

Kate Williams

Georgia Tech’s Center for 21st Century Universities

How to combat the mental health crisis on campus

Jonathan Koppell

Using the power of debate to enhance critical thinking

M. C. Zhang

Macau University of Science and Technology

A case study in developing the next STEM generation

Michael Head, Jessica Boxall, Winfred Dotse-Gborgbortsi, Kathryn Woods-Townsend

Why we need a new model for professional development credentials

Mick Grimley

Lessons learned from a fellowship year as a dentist and early career researcher

Dániel Végh

Learning to learn: developing students into effective lifelong learners

Kevinia Cheung

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Using co-creation to make young people equal research partners

Kathryn Woods-Townsend

Six lessons from facilitating a formalised mentoring programme

Karen Mather

Perfect doesn’t exist and other lessons from developing a whole-university well-being strategy

Ben Goose, Cassie Wilson

Using film to prompt discussion in legal studies

Michael Randall

University of Strathclyde

How supported social groups create safe spaces

Hannah Moore

A practical approach to tackling eco-anxiety

Helen Hicks, Dawn Lees

Nudge technology can help students re-engage

A whole-campus approach to boost belonging for student success

Lorett Swank, Catherine Thomas

Using VR to change medical students’ attitudes towards older patients

János Kollár

Recognising First Nations through place: creating an inclusive university environment

Angela Leitch

Queensland University of Technology

Undergraduate research to enrich teacher education

Molly Riddle, Jacquelyn J. Singleton, Cathy Johnson

Indiana University Southeast

How to make dual-enrolment programmes work

Laura Brown Simmons

A case for bringing ethics of friendship and care to academic research

Noam Schimmel

University of California, Berkeley

Co-creation as a liberating activity

Terry Greene

Trent University

Steps to address the operational challenges of widening participation

Angus Howat

From cohort to community: how to support student-led initiatives

Ranita Thompson, Joanne Walmsley, Ben Graham

How to sustain a journal and beat the academic publishing racket

James Williams, Asma Mohseni

Grow your own accessibility allies

Luke Searle

A colour matrix to make visual content more accessible

Matthew Deeprose

What is authentic enquiry learning?

Kate Black, Jonny Hall

Northumbria University

You wake up in a locked room… Using digital escape rooms to promote student engagement

Steven Montagu-Cairns

University of Leeds

Charting a shared path to net zero universities

Shreejan Pandey, Rebecca Powell

Monash University

Creating a reusable takeout dish programme on campus

Rojine McVea

University of Alberta

Power to the people through automation of peer support programmes

Amanda Pocklington

How can universities get more school pupils enthusiastic about science?

Carl Harrington

Unifying theoretical and clinical education in a medical curriculum

László Köles

A campaign to communicate the impact of university research

Paul M. Rand

The University of Chicago

‘I just wish all lecturers would use the VLE in the same way’

Alison Torn

Leeds Trinity University

A ‘grocery store’ model can help your campus food bank reduce waste

Erin O’Neil

Advice for lecturers on how to keep students’ attention

Kinga Györffy, András Matolcsy

Individual consultations can help PhD students to complete their studies

Szabolcs Várbíró , Judit Réka Hetthéssy, Marianna Török

How to support students considering self-employment

Victoria Prince

Nottingham Trent University

Silence is golden when you ‘shut up and write’ together

Kelly Louise Preece, Jo Sutherst

Why we start undergraduate transdisciplinary research from day one

Gray Kochhar-Lindgren, Julian Tanner

The University of Hong Kong

Raising aspirations: lessons in running a young scholars programme

Valsa Koshy

Brunel University London

Restructuring a university, part one

Bill Flanagan

Restructuring a university, part two

How to write better awards entries

Sam Russell

Arden University

Using gamification as an incentive for revision

Teegan Green, Iliria Stenning, Rasheda Keane

Phenomenon-based learning: what, why and how

Sue Lee, Kate Cuthbert

Student support takes a village – but you need to create one first

Melissa Leaupepe

University of Auckland

AI or VR? Matching emerging tech to real-world learning

Martin Brown , Philip Poronnik, Claudio Corvalan-Diaz, William Havellas

University of Sydney

Virtually writing together: creating community while supporting individual endeavour

Karen Kenny

Supporting LGBTQ+ aspiring leaders in universities

Catherine Lee, Daniel Burman

Anglia Ruskin University

Making space for innovation: a higher education challenge

Michelle Prawer

Victoria University

Can online oral exams prevent cheating?

Temesgen Kifle, Anthony Jacobs

A help desk to protect intellectual property

Frank Soodeen

The University of the West Indies

Autonomy, fun and other benefits of student-centred learning design

A tool to navigate information overload

Shonagh Douglas

Robert Gordon University

How university leaders can use an ‘innovation for’ mindset to drive enrolment

Nivine Megahed

National Louis University

To improve the admission process, get faculty involved

The power of events to build belonging among students

Xiaotong Lu

Full circle: using the cycle of teaching, module design and research

Glenn Fosbraey

University of Winchester

Matching technology training to industry needs: a case study

Daniel Garrote

Nuclio Digital School

My experience of speaking in front of a select committee

Nicola Searle

Goldsmiths, University of London, Universities Policy Engagement Network (UPEN)

A holistic approach to student support

Fran Hornsby, Rebecca Clark

University of York

Peer mentoring to support staff well-being: lessons from a pilot

Fiona Cust, Jessica Runacres

Decolonising learning through access to primary sources

June Barrow-Green , Brigitte Stenhouse

The Open University

Mini virtual writing retreats to support and connect tutees

Aspasia Eleni Paltoglou

Manchester Metropolitan University

A model for deploying AI across a university and region

Cheryl Martin

A collective action framework to help Ukraine’s universities survive and rebuild

Charles Cormack, Blanca Torres-Olave

Cormack Consultancy Group

How to train university staff to become anti-racist agents of change

Adam Danquah

University of Manchester

A guide to promoting equity in HE for refugees and asylum seekers

Yeşim Deveci, Claire Mock-Muñoz de Luna , Jess Oddy

University of East London

Mix technology and personal contact to support students

Jonathan Powles

University of the West of Scotland

Virtual mobility: a first step to creating global graduates

Coventry University

Home labs and simulations to spark curiosity and exploration

Francesco Fornetti

University of Bristol

Food for thought: advice for building a university-community collaboration

]oshua Gruver

Ball State University

Flip the script: why listening is the best form of outreach

Lynne Bianchi

How a sustainable internship programme can support social mobility

Fiona Hudson, Inís Fitzpatrick , Cathy Mcloughlin

Dublin City University

Collective voices, zero tolerance

Louise Crowley

University College Cork

So, you want to reach out? Lessons from a ‘science for all’ programme

Mary Gagen , Will Bryan, Rachel Bryan

Swansea University

Counter-mapping as a pedagogical tool

Daniel Gutiérrez-Ujaque , Dharman Jeyasingham

Brunel University London , University of Manchester

The practicalities of delivering a multi-institutional online workshop

Kelly Edmunds , Richard Bowater

Experiential education through a simulated summit to combat human trafficking

Clara Chapdelaine-Feliciati

How professional practitioners help connect crime theory with real-world investigations

Paul McFarlane

Lessons from completing an award-winning knowledge transfer project

Rachel McCrindle, Richard Mitchell, Yota Dimitriadi

University of Reading

In the loop: how formative feedback supports remote teaching

Jonna Lee , Meryem Yilmaz Soylu

Tutor training for architect-educators: twinning, observation, reflection and testing

Martin W. Andrews, Mary Caddick

The University of Portsmouth

Planning forward: whole system support for marginalised learners in higher education

Carrie Bauer, Cindy Bonfini-Hotlosz, Charley Wright

Arizona State University, Centreity

How to develop a code of conduct for ethical research fieldwork

Catherine Fallon Grasham, Laura Picot

University of Oxford

Pedagogical wellness specialist: the role that connects teaching and well-being

Andrea Aebersold

University of California, Irvine

Bridges to study: how to create a successful online foundation course

Jane Habner , Pablo Munguia

Flinders University

What’s the story? Creative ways to communicate your research

Steven Beschloss

Arizona State University

A STEAM adventure: running a hybrid English immersion camp

Rossana Mántaras , Eugenia Balseiro, Lorena Calzoni

Technological University of Uruguay (UTEC)

Creative projects as a way of bringing students together

Karen Amanda Harris

University of the Arts London

Block to the future: why block scheduling has taken so long to catch on

Carl Flattery, Simon Thomson

Leeds Beckett University, University of Manchester

Outside in: use your students’ curiosity to invigorate your teaching

M. C. Zhang, Aliana Leong

The role of complementary higher education pathways for refugees

Manal Stulgaitis , Gül İnanç

UNHCR, University of Auckland

Lessons in helping remote students obtain practical work experience

Ewout van der Schaft, Alex Mackrell

Education for humanity: designing learner-centric solutions for refugee students

Nicholas Sabato, Joanna Zimmerman

How to turn a PhD project into a commercial venture

Manjinder Kainth, Nicola Wilkin

Graide, University of Birmingham

Increasing access to higher education for refugees through digital learning

Rabih Shibli

American University of Beirut

Helping refugees get their qualifications recognised

Sjur Bergan

Council of Europe

Embedding equality, diversity and inclusion within public policy training for academics

Making undergraduate access to research experience transparent and inclusive

Saloni Krishnan, Nura Sidarus

Royal Holloway, University of London

How a rich extracurricular campus life nurtures well-rounded individuals

How we used a business management theory to help students cope with uncertainty

Zheng Feei Ma, Jian Li Hao, Yu Song, Peng Liu

Eight ways UK academics can help students and researchers from Ukrainian universities

Anna K. Bobak, Valentina Mosienko, Igor Potapov

University of Stirling, University of Bristol, University of Liverpool

How can universities support Ukrainian students? Advice from a Polish institution

Paweł Śpiechowicz

University of Lodz

Blended professionals: how to make the most of ‘third space’ experts

Emily McIntosh, Diane Nutt

Middlesex University

How universities can support refugee students and academics

Naimatullah Zafary

University of Sussex

Recruiting university tutors using an interactive group activity

Carl Sherwood

Tackling climate change requires university, government and industry collaboration – here’s how

Anna Skarbek

Monash University, Climateworks Centre

The challenges of creating a multidisciplinary research centre and how to overcome them

Andrew Tobin, Laura Tyler

University of Glasgow

Revolving roles: creating inclusive, engaging, participant-led learning activities

Pablo Dalby

Asynchronous communication strategies for successful learning design partnerships

Rae Mancilla , Nadine Hamman

University of Pittsburgh, University of Cape Town

Developing a faculty-IT partnership for seamless teaching support

Decolonising medicine, part two: empowering students

Musarrat Maisha Reza

The evolution of activeflex learning: why and how

Athens State University

Lessons for universities from using ‘bots’ in the NHS

Carol Glover

KFM, a subsidiary of King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

A guide to using open educational resources: an experiential case study

Innocent Chirisa

University of Zimbabwe

Catering to Gen Z’s needs: creating a flexible and adaptable education programme

Eric Chee, Roy Ying, Winnie Chan

The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong

Mind the gap: creating a pathway for post-doctoral researchers to gain teaching experience

Students supporting educators: are you harnessing the talent of your own graduates?

Lisa Harris, Caitlin Kight

How to change the default settings that exclude women in sub-Saharan Africa from higher education

Angeline Murimirwa

CAMFED (Campaign for Female Education)

Embedding gender equality: building momentum for change

Eileen Drew

Trinity College Dublin

Widening access to postgraduate studies: from research to strategy to action

The University of Edinburgh

How to use storytelling-based assessment to increase student confidence

Accelerating towards net zero emissions: how to mobilise your university on climate action

John Madden

University of British Columbia

‘Embrace messiness’: how to broker global partnerships to tackle the Sustainable Development Goals

Annelise Riles, Meghan Ozaroski

Northwestern University

How to design early college programmes that foster success for under-represented students

David Dugger

Eastern Michigan University

How using digital workbooks can increase student engagement and help institutions go green

Yan Wei, Paul Tuck

Working with student activists to speed up progress towards a sustainable future

Jaime Toney

Unmasking the scientist: breaking down anonymity to build relationships when teaching online

Kelly Edmunds , Bethan Gulliver

Online exams are growing in popularity: how can they be fair and robust?

Nicholas Harmer, Alison Hill

Co-creating an interdisciplinary well-being module for all students

Elena Riva, Wiki Jeglinska

The University of Warwick

Study trips and experiential learning: from preparation to post-trip reflection

Rebecca Wang

University of Westminster

Building an inclusive learning community to deliver a race equality curriculum

Ricardo Barker , Syra Shakir

Lessons from organising a virtual international student camp to develop the next generation of leaders in sustainability

Yhing Sawheny, Ashutosh Mishra

Siam University

Using community-based research projects to motivate learning among engineering students

Trithos Kamsuwan

Creating equitable research partnerships across continents

Shabbar Jaffar

Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Changing lives through community engagement and outreach

Josephine Bleach

National College of Ireland

Talking about taboos: how to create an open atmosphere for discussing difficult subjects

Lindsay Morgan

Edinburgh Napier University

How to revitalise student knowledge exchange with local communities

Patrick McGurk, Joanne Zhang, Fezzan Ahmed, Olivia Reid

Queen Mary University of London

Collaborative learning cases: a fresh approach to applied learning

Dujeepa Samarasekera

National University of Singapore

Engaging students in applied research to tackle Sustainable Development Goals

Jen O'Brien

A model for developing global expertise in blended learning

Daniella Bo Ya Hu

The Association of Commonwealth Universities

How a community of practice can foster virtual collaboration

Eugene Schulz, Dagmar Willems

German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)

Generating immersive, large-scale teaching experiences in video games

Richard Fitzpatrick, Thomas Little

Students as educators: the value of assessed blogs to showcase learning

Matt Davies

University of Chester

Make yourself presentable

Richard Gratwick

Three lessons from exhibiting final-year projects online

Dechanuchit Katanyutaveetip

Three steps to successful rapid-response civic engagement with students

Kathleen Riach

Developing an educational app to engage students in the world around them

Kate Bowell, Niki Vermeulen

Co-creation of curricula with students: a case study

High tech and high touch: designing a bridging system to help students prepare for STEM studies

Karin Avnit , Victor Wang, Prasad Iyer

Singapore Institute of Technology

It’s a game changer: using design thinking to find solutions to the Sustainable Development Goals

Rachel Bickerdike

Durham University

Global virtual exchange: promoting international learning

Christopher Brighton

Making the most of online educational resources: a case study

Pascal Grange

Using online coaching to support student well-being

Lessons from gamification to enhance students’ capacity for learning

Oran Devilly, May Lim

Using tech to connect refugees with pathways to higher education: an emerging case study

Kate Symons, Georgia Cole, Foundations for All team

The University of Edinburgh, Foundations for All

Greener assessment: transitioning to online marking

Ling Angela Xia , Yao Wu

Lessons in developing digital capability courses for students

Gunter Saunders

Sparking entrepreneurship online

Laura-Jane Silverman

The London School of Economics and Political Science

Building peer support networks to help staff navigate digital teaching

Kay Yeoman, Alicia McConnell

Developing academic writing skills to boost student confidence and resilience

Andrew Struan

How I fostered multilingual student discussion in asynchronous online classes

Ioannis Gaitanidis

Chiba University

How to tackle fieldwork and real-world training online

Francine Ryan

Creating online teaching principles that actually help faculty

Amanda Sykes

Creating a centralised advice resource to help faculty adapt to new teaching modalities

Ingrid Novodvorsky , Lisa Elfring

University of Arizona

How to support staff across all departments to design quality online courses

Helen Carmichael, Bobbi Moore

Innovative approaches to moving practical learning online

Lesley Saunders , Lucy Kirkham

Sheffield Hallam University

Socio-emotional learning online: boosting student resilience and well-being

Benjamin Tak Yuen Chan, Kathleen Chim

Hong Kong Metropolitan University

How Duke Kunshan University transitioned to online learning in two weeks

Kevin Guthrie, Catharine Bond Hill, Martin Kurzweil, Cindy Le

Ithaka S+R , Duke Kunshan University

Accelerating Education for the SDGs in Universities: 2021 case studies out now!

Global Schools Launches Fifth Cohort of the Advocates Program to Build Capacity of Educators to Teach Sustainable Development

Finance Consultant, Science Panel for the Amazon

April 2024 Employee Spotlight - Celebrating Gaëlle Descloîtres!

Junior full stack web developer, strategic advisor.

SDSN Newsletter - March 2024

April 2024 Employee Spotlight - Celebrating Daniel Bernstein!

SDSN Kenya Co-hosts Carbon Markets Clinic and Debate

Science Panel for the Amazon (SPA) Launches First-of-its-kind Massive Open Online Course (MOOC): "The Living Amazon: Science, Cultures and Sustainability in Practice"

Sign up for sdsn updates.

Get our latest insights, opportunities to engage with our networks, and more.

SDSN mobilizes global scientific and technological expertise to promote practical solutions for sustainable development, including the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement.

The SDG Academy

Join the SDSN

News & Even ts

Privacy Policy

19 rue Bergère

75009 Paris

+33 (0) 1 84 86 06 60

New York 475 Riverside Drive

New York NY 10115 USA

+1 (212) 870-3920

Kuala Lumpur Sunway University

Sunway City Kuala Lumpur

5 Jalan Universiti

Selangor 47500

+60 (3) 7491-8622

How research universities are evolving to strengthen regional economies

Subscribe to the brookings metro update, case studies from the build back better regional challenge, joseph parilla and joseph parilla senior fellow & director of applied research - brookings metro @joeparilla glencora haskins glencora haskins senior research analyst and applied research manager - brookings metro @glencorah.

February 9, 2023

When asked how to build a great city, the late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “Create a great university and wait 200 years.” Indeed, America’s network of research universities is one of its greatest sources of talent, entrepreneurship, and research and development—three inputs that in combination can fuel prosperity in the regions that surround those universities.

Yet, while most strong regional economies have a leading research university, the reverse is not always true. That is because the link between university research, commercialization, and broader regional development is neither automatic nor immediate. Some universities are better at engaging with their surrounding industries and communities, and some regions have industries and communities that are more ready to translate the knowledge universities produce into economic development.

The reality is that regional economies are complex, and their outcomes are influenced by countless interactions between markets and institutions—including but not limited to large research universities. Many inputs matter to regional economic development (e.g., business growth, job creation, skilled workers, well-planned built environments), but each is determined by separate regional systems that too often remain unintegrated. In other words, economic development is a “multi-system” process, but regions struggle with effective multi-system governance.

A new wave of federal place-based economic policies led by the Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA) and the National Science Foundation is seeking to change this dynamic through larger-scale, longer-term competitive challenge grants that bring together networks of institutions, including research universities, around a targeted economic opportunity. And in addition to their sizable resources, these challenge grants are designed to catalyze multi-system strategies by requiring a lead regional entity to coordinate organizations across those systems.

While many types of regional institutions could serve this function, research universities are increasingly embracing this role because they understand that regional economic impact requires blending university-based research and talent, industry partnerships, and coordinated governance. Drawing on one of those programs—the EDA’s $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge —this post explores some of the most promising multi-system economic strategies that research universities are leading.

Research universities’ regional economic impact depends on their relevance to surrounding industries and communities

There is a wide body of literature documenting the positive economic impact of research universities. Regions that became home to a land grant university over a century ago have stronger economies today as a result. Increasing state funding to research universities leads to higher levels of local patenting and entrepreneurship. And for each new university patent, researchers estimate 15 additional jobs are created outside the university in the local economy. Indeed, as Daniel P. Gross and Bhaven N. Sampat write , major national research and development efforts (such as those during World War II) tend to shape the geography of American innovation via research universities.

In a nation plagued by regional economic divides, research universities are a uniquely distributed innovation asset. Unlike innovation sector employment , high-growth startups , and venture capital , research universities are spread across the entire nation. Over 200 research universities located in all 50 states expend more than $50 million annually on research and development.

Yet, there are limits to universities’ impact. In a comprehensive review of the literature, economists E. Jason Baron, Shawn Kantor, and Alexander Whalley offer three takeaways: “First, universities’ ability to affect their local economies solely through the supply of college graduates is limited. Second, the main channel by which universities can affect their local economies is through highly localized knowledge spillovers. Third, the literature provides little evidence that establishing a new university in the 21st century is sufficient to revitalize a lagging community and transform its economy. To help revive struggling regions, using existing nearby universities could be a far more cost-effective policy tool.”

In other words, knowledge spillovers to surrounding firms and industries are strongest when university-generated knowledge is highly complementary to industry needs.

Federal place-based industrial policies are linking research universities with local industry clusters and surrounding communities

Against this backdrop, new federal programs are pushing research universities to deploy their talent and knowledge in ways that strengthen the industry clusters that surround them. Finding that knowledge-industry nexus was a central strategic exercise for the 60 finalists in the EDA’s $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) , which asked applicants to craft five-year strategies that invest in advanced industry clusters in ways that benefit historically excluded communities.

Research universities played a fundamental role in the competition. [1] Among the 60 finalist coalitions, research universities served as the quarterback organization in 12, and participated in a supporting role in another 29. Over one-third of the EDA’s investments were awarded to research universities (although many universities are passing those resources on to partners).

How did research universities propose to use that money? In our recent report analyzing the BBBRC, we categorized cluster projects into five categories: talent development; research and commercialization; infrastructure and placemaking; entrepreneurship and capital access; and governance. While research universities are, unsurprisingly, most heavily concentrated in research (41% of overall funding) and talent development (26%), they also proposed a significant number of projects related to tailored infrastructure and innovation facilities, entrepreneurship accelerators and incubators, and regional governance.

The BBBRC exemplifies how research universities can anchor multi-system economic strategies

Catalyzing and growing clusters requires investing in talent, research and development, entrepreneurship, and infrastructure. But regions often struggle to marshal the fiscal, political, and institutional capacity needed to overcome fragmentation in innovation, entrepreneurship, research, workforce, and industry leadership systems and act at a multi-system scale.

Operating at a multi-system scale requires a quarterback organization to coordinate goals, strategies, and investments across those systems. Many types of entities can play this role, but research universities are natural candidates due to their relatively large scale and critical role in fueling innovation ecosystems.

University utilization of BBBRC dollars signifies the potential for research universities to be a fulcrum for multi-system strategies. Indeed, one-third of the research universities in the BBBRC finalist coalitions proposed multi-system strategies, meaning they proposed to lead investments in at least three of the five project categories listed above.

For example, through the New Energy New York (NENY) coalition , Binghamton University is seeking to reorganize the Southern Tier area of upstate New York into a hub for battery manufacturing and energy storage. The university’s multi-system approach will advance the cluster’s talent pool, supply chain, and supportive physical infrastructure. And through the NENY Workforce Development Initiative, the university will partner with other coalition members in higher education to expand existing workforce development programs and develop new training curricula. This partnership will implicate many of the region’s community colleges (including State University of New York [SUNY] Corning and SUNY Broome) and other research universities (including the Rochester Institute of Technology) in reducing the cluster’s barriers to entry and cultivating a diverse pool of well-trained employees to move into its high-wage jobs.

Binghamton University will supplement these workforce development efforts through their NENY Supply Chain Program, where they will partner with the Alliance for Manufacturing and Technology (AMT), NY-BEST, Empire State Development, New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), and other coalition members and industry partners to expand and improve the cluster’s supply chain. The expansion of this supply chain will enhance the region’s demand for skilled talent in the battery sector and create high-wage jobs for participants in the Workforce Development Initiative. These initiatives will support Battery-NY, the NENY coalition’s hub of infrastructure and industry experts working to advance energy storage technology, support cluster manufacturers, and attract businesses to the region.

Georgia Tech has also proposed operating across multiple systems to bolster advanced manufacturing across the state through the Georgia AI Manufacturing (GA-AIM) coalition. To prepare the state’s future workforce, Georgia Tech will partner with Spelman College and the Technical College System of Georgia on degree and non-degree training options in artificial intelligence. As a complement, the Georgia Tech Enterprise Innovation Institute’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership (GaMEP) will promote the adoption of AI technology among small and medium-sized enterprises in rural communities across the state, creating demand for those newly trained workers. On governance, the Enterprise Innovation Institute’s Connect to Hire program will seek to connect historically excluded communities to these talent development and innovation initiatives. Finally, Georgia Tech is investing in new physical centers to enable commercialization and startup growth.

Further west, the University of Nebraska is a major implementation partner to Invest Nebraska in the Heartland Robotics Cluster ’s efforts to accelerate the state’s agricultural technology sector. The Nebraska Manufacturing Extension Partnership (NM-EP) at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources will identify small, medium-sized, and startup manufacturers in rural and urban communities across the state and create a supply chain database connecting them to high-quality suppliers. In addition, the NM-EP will help these manufacturers integrate new robotics technologies into their existing production systems. And as part of the Heartland Robotics Cluster’s commitment to workforce development, the NM-EP’s technology adoption program will provide credentialing and certification to participating manufacturers for cooperative robotic technologies.

In future work, we will profile the implementation of comprehensive university approaches to learn more about how these strategies play out. But these three examples suggest that several elements are necessary to work at a multi-system scale. First, universities must have existing innovation assets that industries value; in each example above, universities are working from existing strengths, not trying to build from scratch. Second, those universities need to have the staff, systems, and staying power to work with other organizations in the region, from government agencies to economic development organizations to community colleges, workforce boards, and community-based organizations. Often, this requires an entrepreneurial leader that can create and sustain strong working and personal relationships with other community leaders. And third, there typically needs to be an external funding source, such as a federal or state program, to rally regional actors around a more ambitious strategy. In this case, the BBBRC provided exactly that type of “jump-ball” funding effect.

While multi-system approaches will not be feasible in every region, the BBBRC illustrates that when the conditions are ripe, universities, industry, and communities can pursue a more systemic approach to regional economic development.

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

1.“Research universities” include universities that award a minimum of 20 research-based doctoral degrees and spend at least $5 million on research per academic year. Universities are categorized according to the 2021 Carnegie Classifications of Higher Education Institutions based on data collected in the National Science Foundation’s Higher Education Research and Development Survey.

Economic Development

Brookings Metro

Promoting equitable and effective climate action in every community

Kirsten Kaschock, Ayana Allen-Handy, Barbara Dale, Lauren Lowe, Carol Richardson McCullough, Rachel Wenrick

April 25, 2023

Mark Muro, Robert Maxim, Yang You

October 20, 2022

Andre M. Perry, Anthony Barr, Carl Romer

December 3, 2021

This New Year, our focus is clearer. Wiley Education Services is now Wiley University Services. Explore our flexible, career-connected services.

Higher Education Case Studies

Want to know how we’ve collaborated with universities to support their learners? Look no further.

From enhancing course quality to building operational efficiency in areas such as enrollment and retention, our higher education case studies detail a few ways we’ve tailored services for our university partners and improved outcomes for their learners.

Case Studies

The Power of Flexible Partnership: Case Studies of a Diverse Group of Institutions

Putting community first: growing nursing program enrollments at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University

University of Birmingham: Increasing enrollments through simplified processes and teamwork

Gaining a Global Presence Through Technological Innovation and Expert Strategy

Enabling Students to Succeed through One-on-One Care and Field Placement Support

Elevating Course Quality After a Fast Pivot to Online Learning

Fee-For-Service Projects Give You the Right Support — Right Now

Just What You Need: Accelerated Project Delivers for Faculty Development Program

At Northern Illinois University, Shaping A Partnership To Fit

Growing Online Enrollments Through a Data-Driven Approach

Improving the Online Learning Experience: The Benefits of Enhanced Student Evaluations

Creating a Meaningful Online Learning Experience for Students Amid Campus Closures

Overcoming Declining Enrollments: How a Unified Partnership Facilitated University Growth

Let's Talk.

Complete the form below, and we’ll be in contact soon to discuss how we can help.

If you have a question about textbooks, please email [email protected].

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Organization *

- Country * Afghanistan Albania Algeria American Samoa Andorra Angola Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Brunei Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Colombia Comoros Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Costa Rica Côte d'Ivoire Croatia Cuba Curaçao Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Polynesia Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Greenland Grenada Guam Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati North Korea South Korea Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Laos Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Mauritania Mauritius Mexico Micronesia Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Morocco Mozambique Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Palestine, State of Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Russia Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Saint Martin Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Sint Maarten Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Sudan, South Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Togo Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City Venezuela Vietnam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S. Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

- I'm interested in * Wiley University Services Wiley Beyond Advancement Courses Wiley Edge Other

- What would you like to learn more about—partnership models, technology services, media request assistance, etc.? *

By submitting your information, you agree to the processing of your personal data as per Wiley's privacy policy and consent to be contacted by email.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Higher Education Case Studies: ACUE Partnerships Impact Institutions Nationwide

A robust and growing body of impact studies speaks to the transformative effects of acue certification on faculty, students, and institutions. .

Higher Student Retention and Stronger, More Equitable Outcomes Through Quality Teaching

Elevate Your Mission

From the rural community college to the urban liberal arts university, every institution has a unique story. ACUE partnership is a shared guarantee that—no matter what attributes define your mission—it will be elevated by excellent teaching.

Privacy Policy

Terms and Conditions

Statement of Accessibility

Building operational excellence in higher education

When colleges and universities think about building academic enterprises for the 21st century, they often overlook one of the most critical aspects: the back-office structures needed to run complex organizations. By failing to modernize and streamline administrative functions (including HR, finance, and facilities), universities put themselves at a serious disadvantage, making it harder to fulfill their academic missions.

Take faculty recruitment and retention. The perceived level of the administrative burden is often a major factor in the attractiveness of an academic job offer. In 2018, the administrative burden on productive research faculty was measured at 44 percent of their workload (up from 42 percent in 2012). 1 Sandra Schneider, “Results of the 2018 FDP faculty workload survey: Input for optimizing time on active research,” Federal Demonstration Partnership, January 2019, thefdp.org. For faculty members, the prospect of moving to an institution where they would have a lighter administrative load is a huge selling point, since “institutional procedures and red tape” ranks as one of the top five sources of stress. 2 Ellen Bara Stolzenberg et al., “Undergraduate teaching faculty: The HERI faculty survey 2016-2017,” Higher Education Research Institute, February 2019, heri.ucla.edu. Something similar happens with students: studies show that the need to jump through administrative hoops is an important driver of “summer melt,” when students admitted to a school fail to matriculate for the upcoming year. 3 Emily Arnim, “Why summer melt happens—and how to freeze it,” EAB, April 30, 2019, eab.com.

Outdated and ineffective administrative operations can have more direct effects on an institution’s reputation. Financial fraud, ineffective or unfair personnel practices, and grants lost as a result of poor research administration can all lead to negative press reports—or worse. The 115-year-old College of New Rochelle, in New Rochelle, NY, recently closed its doors after fraud decimated its finances and reputation, making any chance of recovery impossible. 4 Dave Zucker, “As College of New Rochelle closes, Mercy steps in to take on displaced students,” Westchester Magazine , March 5, 2019, westchestermagazine.com.

A vast challenge

In our experience, most colleges and universities that set out to improve their administrative operations fail to meet their stated goals and in some cases take a step backward. There are several reasons, many relating to the unique constraints of academic institutions:

- Starting from the top down. Universities are essentially confederations of departments and functions, each with its own internal organization and power structure. Rather than gathering input and alignment from these constituencies, many new administrative plans are run centrally and fail to gain traction.

- Putting the answer before the problem. Another common pitfall is starting with a solution and looking for ways to solve a problem for that answer rather than doing the work needed to gain a deep understanding of the problem on the ground and building a solution collaboratively with stakeholders.

- Focusing on dollars rather than sense. Other change programs flounder because they focus primarily on cost savings rather than on improving service levels or the experience of the administrative staff.

A failed program is more than just a loss of time and money. By raising the expectations of faculty and staff and then failing to follow through on them, such failures stoke resentment and make it harder for future programs to gain traction.

While improving administrative operations remains a vast challenge for many universities, a few are taking a new approach—and posting meaningful results. In some cases, institutions that transformed their back offices have managed to halve the time needed to hire new staff or have reduced wasteful procurement transactions by more than 50 percent.

A new approach for a university in gridlock: A case study

A major public research university knew it had reached the breaking point. Its outdated administrative operations were holding it back on several fronts. Slow response times, red tape, and time-consuming administrative tasks had generated resentment and frustration among faculty. Some had already left for other universities, citing a lack of support for research administration, an inability to hire critical lab staff in less than six months, and difficulty keeping labs stocked with supplies.

Part of the problem was that no one seemed to be accountable. The schools and other units blamed the central administration. Central staff, meanwhile, thought the schools and units weren’t doing their part. In this stalemate, nothing got fixed.

Things only got worse when university leaders decided to create a shared-services effort intended to deliver multimillion-dollar savings. When frustrated deans and faculty heard about the effort, they made it clear that any plan conceived without their input would not have their support. With no resolution in sight, and core functions such as hiring and procurement in jeopardy, university leaders realized they needed to find a new approach.

Would you like to learn more about our Social Sector Practice ?

Rethinking administrative operations from the ground up.

The leadership realized that instead of once again creating a solution they would then impose on a diverse system, they had to understand the problems from the point of view of the various stakeholders and then design targeted fixes. With that fundamentally different perspective, the change team created a carefully thought out road map and began the hard work of redesigning systems and processes:

- The first step was a listening tour to hear directly from faculty and staff on the problems they encountered. What were their pain points? Where exactly were the bottlenecks? The team got unvarnished feedback. From the director of a research center: “We had to hire temporary employees just to complete our normal tasks because the hiring time is so slow.” From a dean: “The university felt like it was in gridlock.”

- Next, the change team convened a group of design teams, made up of members from both the schools and the central staff, to break down the problems, reimagine the processes from a blank sheet of paper, and implement changes.

- The team started the redesign process with two specific initial goals: reducing the time needed to hire administrative staff from an average of more than 80 days to 45 days and reducing the number of procurement vouchers—tens of thousands of them—that wasted thousands of hours of staff time and failed to capture the right data.

- As the team worked through each service, it followed a fast, structured process, designing new solutions in about two months, piloting them for two to three months, and then rolling them out to the campus in waves of schools and units over the following six months.

The results were unequivocal: time to hire fell by 46 percent for nonfaculty positions, and improper procurement (measured by the volume of unnecessary vouchers) fell by 57 percent (Exhibit 1).

So far, the improvement in hiring time has had significant downstream effects. For example, 96 percent of hiring managers report acceptances by their first-choice candidates. In the past, many first choices had dropped out of the process to pursue other opportunities as their names sat in the queue during the months-long hiring process. Just as important, the change team created a community of faculty, staff, and academic leaders who fully embraced the new ways of working. Over the course of the redesign effort, the process involved more than 400 staff and faculty, held more than 50 listening sessions, convened more than 30 design workshops, and generated a list of dozens of initiatives to pursue in the future (Exhibit 2).

The team is currently pursuing transformational initiatives in research administration, travel, student-worker support, and academic personnel. Its ambitions are equally transformative. For example, its goal in research administration is to cut the time to set up awards in half. This collaborative, bottom-up process led many staff members to tell the leadership that “this feels different” from previous change efforts.

Understanding the elements of success

A few key elements helped make a big difference.

Involve faculty and staff as true collaborators. Don’t drive the change from the central administration down to schools and units. Instead, raise the quality and adoption rate of operational solutions by converting faculty and staff from sideline observers into true collaborators. Start with listening to end users, understanding the obstacles they face, and jointly identifying where and how the current system fails them. In that way, a university can bypass the tendency to consider overarching organizational solutions and focus on solving the actual problems at hand.

Have central administrators work side by side with employees of schools or units. For creating solutions, a partnership between the central administration and the faculty and staff of schools or units is even more critical. It is essential to develop solutions by having representatives from schools and units work together with central staff. Besides gaining a deeper understanding of the problems by including these stakeholders, leaders can begin to convert possible naysayers among faculty and staff into allies.

Focus on the university’s mission. While efficiencies and cost savings are important, they are notoriously hard to capture and reinvest. In addition, any sense that the real goal is to cut costs is unlikely to build internal allies among faculty and staff who already feel undersupported. Instead, leaders should communicate a message of improved service levels that can help further the university’s academic and community-impact missions.

Transformation 101: How universities can overcome financial headwinds to focus on their mission

Show an impact early. There’s a saying that nothing succeeds like success. By starting with one or two services that can be improved quickly and showing an impact within six months, leaders can build belief in the effort. Winning over skeptical constituents will make the rest of it move forward more easily.

Invest in a continuous-improvement team. Staff volunteers committing many hours a week on top of their day jobs can’t sustain changes and expand into other areas of the university entirely by themselves. Creating a small team dedicated to executing transformation initiatives across administrative functions can help accelerate and sustain the momentum for change across the university. A high-functioning team will have a catalog of services (such as training, facilitation, and full-on process redesign) that helps it tailor its support to the specific details of a given problem.

Focus on a transformational rather than incremental impact. Redesigning administrative operations across a university is a big effort. Leaders should take full advantage of the opportunity by thinking about a total transformation, not incremental change. Typical efforts aim for a 20 percent improvement. When leaders set their sights on improvements of more than 50 percent, they can free themselves from the status quo. That magnitude of change will force the change team to start with a truly blank slate and to reimagine a dramatically improved future one.

Taking an important step in transforming a university

A final insight: the work this university did enabled leaders of the administrative functions to shift their sights beyond fighting fires to the truly strategic parts of their work. The progress on hiring, for example, helped surface the challenges the university faces in attracting and retaining talent—particularly underrepresented minority faculty. Furthermore, conversations about improving the performance of the administrative functions highlighted the aspirations of leaders and staff to use machine learning, automation, and other advanced techniques in their work.

Although administrative operations are often overlooked, efficient and effective ones can lead to much broader changes. When universities can hire the high-potential candidates they seek, eliminate wasted time of faculty and staff, and unlock the power of data, they can catapult ahead in their ability to meet their educational and research missions.

Stay current on your favorite topics

Suhrid Gajendragadkar is a senior partner in McKinsey’s Washington, DC, office, where Ted Rounsaville is an associate partner and Jason Wright is a partner; Duwain Pinder is a consultant in the New Jersey office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Universities and the conglomerate challenge

How higher-education institutions can transform themselves using advanced analytics

New IHEP Case Studies of Minority-Serving Institutions Offer Actionable Strategies for Increasing Value in Postsecondary Education

Washington, DC (March 28, 2024) – Institutional policies and practices shape which students have access to college, who persists and completes, who borrows, and who experiences economic and social mobility. In two new case studies, IHEP spotlights how two Minority-Serving Institutions – University of North Texas and LaGuardia Community College – employ innovative strategies that help more students receive measurable returns on their investment in higher education.

Using the Equitable Value Explorer , an interactive data dashboard that allows users to analyze and compare student outcomes, IHEP found that the typical student at both UNT and LaGuardia meet s the minimum economic return – meaning they earn at least as much as a high school graduate in their state plus enough to recoup their investment within ten years. Students who leave these campuses also tend to have post-college earnings that exceed the median earnings for their degree level in their state. UNT’s median earnings also exceed an economic mobility threshold. The typical UNT student earnings exceed the 60th percentile of earnings for prime-age workers in Texas. Institutions of all types can look to the Equitable Value Explorer to assess the economic value they provide to students.

The new case studies are informed by interviews with administrators, faculty, staff, and students at both institutions, and share lessons other institutions can apply to strengthen student-centered and data-informed approaches to promoting student success. The research offers recommendations including fostering a student-centered approach, utilizing data to drive informed decision-making, and proactively identifying and removing barriers that hinder student success.

Believing in the Potential of Every Student: A Case Study on LaGuardia Community College

LaGuardia Community College, a public two-year institution located in Long Island City, New York, exemplifies a commitment to student-centered learning. “If we really believe in the potential of each individual student, no matter where they come from and where they want to go, what they want to get out of their LaGuardia experience—we have to be committed to helping them realize their full potential,” said President Kenneth Adams.

LaGuardia’s success hinges on several key strategies:

- Prioritize a student-centered culture: Building and maintaining a student-centered culture requires leaders who explicitly commit to and embody this mindset in every facet of their work. Where an institution invests its money, time, and energy shapes students’ experiences. Leaders at LaGuardia encourage collaboration between administrators, faculty, and staff to explore the impact of policies and practices through a student lens.

- Leverage data to drive change and innovation: LaGuardia utilizes data analytics to identify areas for improvement and implement targeted interventions. As one example, data on enrollment trends helped pinpoint students in nondegree programs who were potential candidates for degree programs and provided the students with additional support.

- Proactively identify barriers and take opportunities to smooth student pathways: At LaGuardia, this includes establishing connections between nondegree and academic programs, developing articulation agreements with four-year institutions, and ensuring that students have targeted support before, during, and after transition points.

Creating a Culture of Data Use: A Case Study on the University of North Texas

The University of North Texas (UNT), a public four-year Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI), exemplifies how data-driven decision-making can improve outcomes for all students. Revamping its data infrastructure , led to several improvements and key lessons:

- Use disaggregated data to inform outcome-driven decision-making: UNT created a centralized data system integrating information from various departments to allow for a more holistic view of student progress. Disaggregated data can reveal opportunities to make policy and practice changes that ensure all students succeed.

- Consider everyone on campus a data user and design systems to meet their needs: UNT deliberately engages stakeholders across campus – faculty, staff, and administrators – to use data in their day-to-day work serving students. The university provides training and support to equip staff with data analysis skills.

- Invest in culture as well as data tools and systems: Data tools are just that—tools individuals must use effectively to produce strong student outcomes. UNT’s Insights 2.0 project ensured stakeholders across campus had the training, capacity, and support to use data to make informed and student-centered decisions.

“The data is just data; that’s not going to change your institution, just by having data. It’s having literacy around the data. It’s having people know how to understand what data means,” said Jason Simon, Associate Vice President for Data, Analytics, and Institutional Research. Taking inspiration from these campuses, leaders, faculty, and staff at institutions of all types and sizes can intentionally construct valuable learning experiences, increase graduation rates, and strengthen career pathways to ensure all students develop the knowledge, skills, and networks needed to be successful in work and life.

To read more IHEP research featuring institutions moving the needle on postsecondary value, check out our case study of Northern Arizona University .

Investing in Student Success: IHEP’s Federal Funding Priorities for FY25

Celebrating Success: 2024 federal funding bill keeps National Postsecondary Student Aid Study data collection intact

Global Case Studies. Digital Transformation in Higher Education.

HolonIQ’s Global Case Studies share the process of digital transformation with snapshots of how institutions are building digital capabilities along the student lifecycle.

Education Intelligence Unit

Global Case Studies provide brief snapshots of the different ways that institutions are tackling digital transformation challenges and building digital capabilities all along the student lifecycle. Each case study aligns with one or more digital capabilities identified in the four Dimensions of the Higher Education Digital Capability (HEDC) framework.

🇲🇽 tecnológico de monterrey.

Tecnológico de Monterrey is one of only 45 universities in the world ranked with 5 QS Stars, and is widely recognized as one of the most prestigious universities in Latin America.

During their undergraduate registration period, they would receive over 14,000 enquiries from students, requiring a team of 10 people to respond to and support these questions.

In this global case study, we showcase how a virtual chatbot with AI functionality was established to create a better experience for students during enrollment, and the outcomes enabling Tecnológico de Monterrey staff to focus on more complex enquiries.

Download the full Global Case Studies series .

🇺🇸 University of Rochester

The University of Rochester gives undergraduates exceptional opportunities for interdisciplinary study and close collaboration with faculty through its unique cluster-based curriculum.

In this global case study, we explore how the university addressed the challenge of expanding and scaling student access to jobs and internships across diverse industries and geographies. Through the development of a student-centric approach to democratize employment and internship opportunities across the university, a Platform partnership was established to ensure student access to employment and internship opportunities.

🇦🇺 University of Queensland

The University of Queensland consistently ranks among the world’s top universities, reflecting UQ’s global standing and the high quality of its researchers, teaching staff and alumni.

This global case study from The University of Queensland and UniQuest demonstrates how partnering with students as content creators and evaluators can personalize the learning experience in large undergraduate courses.

Explore more about how this project used adaptive learning as a supplementary tool to teaching, whilst also putting students front and centre in their learning journey.

🌍 Honoris United Universities

Honoris United Universities is the largest Pan-African network of private higher education institutions with operations across 10 countries and 32 cities in Africa.

The institutions which form part of the Honoris United Universities network encompass 40+ nationalities with diverse cultures and backgrounds. With employability a core focus in the region, learners have high aspirations for global career development.

Read about how the Honoris United Universities network challenge traditional approaches to internships, envisaging a ‘digital career center’ for Honoris institutions to better suit the needs and ambitions of today’s learners in a rapidly changing world of work.

🇲🇾 Wawasan Open University

Wawasan Open University (WOU) is a private university in Penang, Malaysia. In addition to its main campus in Penang, WOU operates 4 regional centres in Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, Johor Bahru and Kuching for distance learners located in and around those cities.

In this global case study, read about how the combined strengths of faculty knowledge and partnerships enabled effective re-thinking in design and curation of digital learning content to support transformation of distance learning delivery in Computer Science.

🇮🇪 University College Dublin Professional Academy

University College Dublin ranks in the top 1% of higher education institutions worldwide. The UCD Professional Academy is an extension of the university, focused on professional development.

In order to build closer links with workforce and industry and grow new sources of revenue, new product strategies and business models had to be explored outside traditional boundaries. In this Case Study we share how the University responded to the needs of working professionals and employers, building a successful, profitable business in the alternative credential space and delivering high quality learning to the workforce.

HEDC Framework

Each case study aligns with one or more digital capabilities identified in the four Dimensions of the Higher Education Digital Capability framework ; Demand and Discovery (DD), Learning Design (LD), Learner Experience (LX), Work & Lifelong Learning (WL).

The Framework is a learner-focused, practical and flexible approach to mapping and measuring digital capability in higher education institutions. Get in touch to share a case study from your institution .

Latest Insights

Global Insights from HolonIQ’s Intelligence Unit. Powered by our Global Impact Intelligence Platform.

April 12, 2024

2024 North America EdTech 200

April 2, 2024

Applications open for the Indo-Pacific Climate Tech 100, connecting leading startups with 100 global investors

April 1, 2024

EdTech VC collapse at $580M for Q1. Not even an AI tailwind could hold up this 10 year low.

March 15, 2024

Webinar. Innovation & Growth in Higher Education in the Era of AI

March 7, 2024

The 2024 Global State of Women's Leadership

February 8, 2024

Australia & New Zealand Climate Tech 100

.png)

Sign Up for our Newsletters

We provide you with relevant and up-to-date insights on the global impact economy. Choose out of our newsletters and you will find trending topics in your inbox.

Weekly Newsletter

Climate Technology

Education Technology

Health technology.

Higher Education

Daily Newsletter

Chart of the Day

Impact Capital Markets

Advertisement

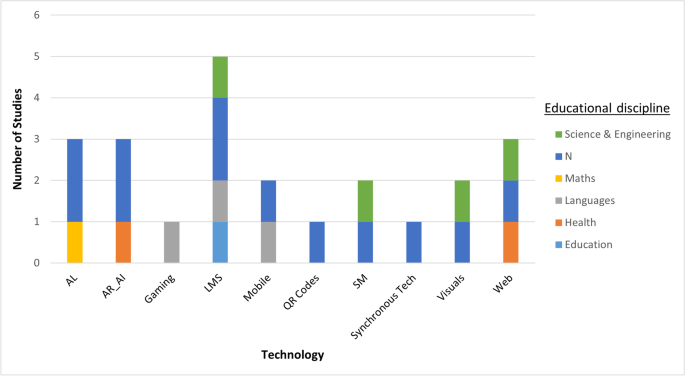

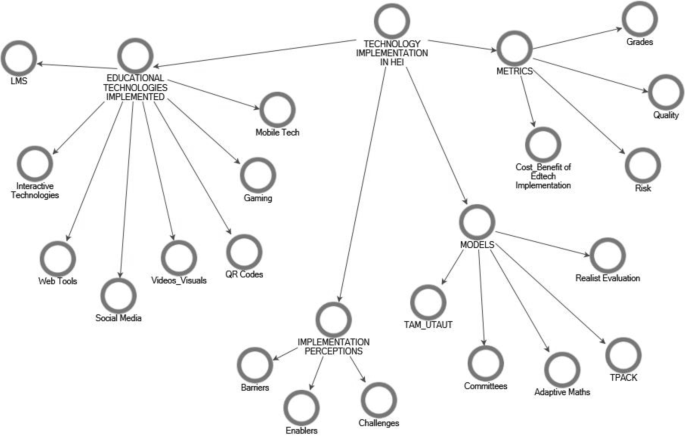

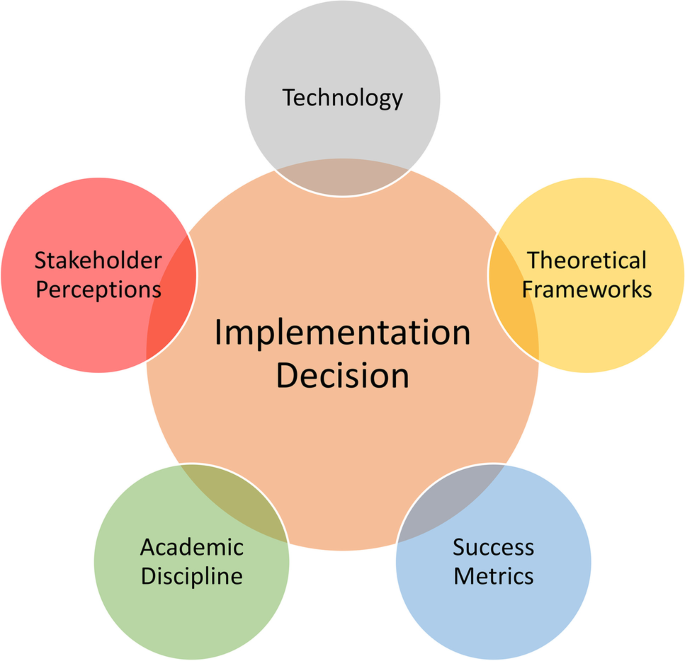

Implementing educational technology in Higher Education Institutions: A review of technologies, stakeholder perceptions, frameworks and metrics

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2023

- Volume 28 , pages 16403–16429, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ritesh Chugh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0061-7206 1 ,

- Darren Turnbull ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0509-8564 1 ,

- Michael A. Cowling ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1444-1563 1 ,

- Robert Vanderburg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0439-1806 2 &

- Michelle A. Vanderburg ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3769-0394 2

5774 Accesses

7 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In a world driven by constant change and innovation, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are undergoing a rapid transformation, often driven by external factors such as emerging technologies. One of the key drivers affecting the design and development of educational delivery mechanisms in HEIs is the fast pace of educational technology development which not only impacts an institution’s technical capacity to infuse hardware and software solutions into existing learning infrastructure but also has implications for pedagogical practice, stakeholder acceptance of new technology, and HEI administrative structures. However, little is known about the implementation of contemporary educational technology in HEI environments, particularly as they relate to competing stakeholder perceptions of technology effectiveness in course delivery and knowledge acquisition. This review fills that gap by exploring the evidence and analyses of 46 empirical research studies focussing on technology implementation issues in a diverse range of institutional contexts, subject areas, technologies, and stakeholder profiles. This study found that the dynamic interplay of educational technology characteristics, stakeholder perceptions on the effectiveness of technology integration decisions, theoretical frameworks and models relevant to technology integration in pedagogical practices, and metrics to gauge post-implementation success are critical dimensions to creating viable pathways to effective educational technology implementation. To that end, this study proposes a framework to guide the development of sound implementation strategies that incorporates five dimensions: technology, stakeholder perceptions, academic discipline, success metrics, and theoretical frameworks. This study will benefit HEI decision-makers responsible for re-engineering complex course delivery systems to accommodate the infusion of new technologies and pedagogies in ways that will maximise their utility to students and faculty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools' digital capacity and transformation: A literature review

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

A Systematic Review of Research on Personalized Learning: Personalized by Whom, to What, How, and for What Purpose(s)?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Educational technology implementations in higher education institutions are becoming increasingly popular as a way to improve learning and teaching. The Association for Educational Communications and Technology defines educational technology as “the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using and managing appropriate technological processes and resources” (Januszewski & Molenda, 2008 , p. 1). Simply put, educational technology (EdTech) is the use of technology in different educational settings to enhance learning and improve educational outcomes.

Globally, higher education institutions (HEIs) are using technology-based learning tools such as learning management systems or virtual learning environments (Turnbull et al., 2022 ), virtual and augmented reality (Jantjies et al., 2018 ), chatbots (Neumann et al., 2021 ), videoconferencing (Al-Samarraie, 2019 ), social media (Chugh & Ruhi, 2019 ) and mobile learning (Kaliisa & Picard, 2017 ). EdTech tools like these help instructors create engaging learning experiences for their students, leading to several short and long-term academic and social outcomes (Bond & Bedenlier, 2019 ). Additionally, EdTech can be used to facilitate communication between students and instructors, as well as to provide individualised feedback to students (Bower, 2019 ).

However, it is important to note that the implementation of EdTech in HEIs is not without its challenges (Cabaleiro-Cerviño & Vera, 2020 ; Laufer et al., 2021 ). Hence, it is crucial for HEIs to carefully evaluate the effectiveness and impact of these technologies before adopting them. Implementation research involves understanding the factors that influence implementation and a ‘scientific inquiry into questions concerning implementation’ (p. 1), such as those related to diverse stakeholders, the environment, and the strategies that can facilitate implementation (Peters et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, implementation research explores whether educational efforts are achieving the expected goals and objectives by asking questions that focus on ‘What are we doing? Is it working? For whom? Where? When? How? And, Why?’ (Century & Cassata, 2016 , p. 169). Often implementation outcomes focus on ‘acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, coverage, and sustainability’ (p. 2), which serve as indicators of the success or failure of the implementation efforts (Peters et al., 2013 ). Accordingly, our research questions were formulated with an emphasis on implementation outcomes.

Literature reviews over the past decade have explored the role of educational technology on stress and anxiety (Fernandez-Batanero et al., 2021 ), e-leadership (Arnold & Sangrà, 2018 ), acceptance (Granić & Marangunić, 2019 ), effectiveness (Delgado et al., 2015 ), and creativity (Henriksen et al., 2021 ), but none have specifically focused on ‘implementation of EdTech’ in ‘HEIs’ settings. To fill the gap, this study provides both a quantitative measure of attributes such as region, discipline, data collection method, technology, and methodology, as well as a further qualitative review of the body of literature about EdTech implementations in HEIs. Literature was collated using the PRISMA process, and qualitative data were thematically grouped using NVIVO. For the purposes of this study, we will not focus on any one specific technology but use EdTech as an overarching term that refers to the use of any EdTech.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The following section outlines the research methodology adopted in this study. The results are presented in tabular and graphic format in the next section. This is followed by the qualitative analysis, which outlines the coding scheme developed from an iterative inductive analysis of the shortlisted articles. Then a brief discussion is presented, along with a framework to guide the future implementation of EdTech in HEIs. Finally, a summary is provided in the conclusion section, and the limitations are outlined.

2 Research methodology

Exploratory implementation research that focuses on exploring an idea, such as EdTech implementation in HEIs, can utilise historical literature reviews as its research method (Peters et al., 2013 ). Hence, we adopt a systematic-narrative hybrid literature review strategy that combines elements of both systematic and narrative literature reviews. Like systematic reviews, this hybrid approach employs a methodical and transparent search method, including identifying the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of the literature, and then uses a qualitative narrative approach for the analysis focusing on the main findings and themes (Turnbull et al., 2023 ).

In line with implementation research and the identified gap, we structure our study around the following research questions to conduct an in-depth analysis of the literature:

RQ1. What are the common EdTechs implemented in HEIs?

RQ2. How do HEI stakeholders perceive the implementation of EdTech?

RQ3. What theoretical frameworks and models are relevant to EdTech implementations in HEIs and the metrics to gauge post-implementation success?

Based on the research questions and the scope of the review, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1 ) were developed.