- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Leadership →

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

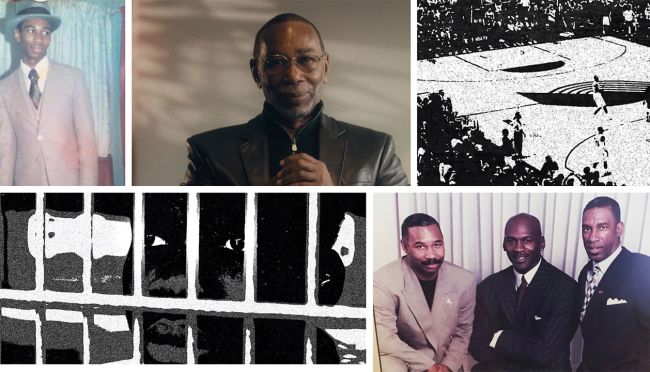

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 02 Jan 2024

- What Do You Think?

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

10 Trends to Watch in 2024

Employees may seek new approaches to balance, even as leaders consider whether to bring more teams back to offices or make hybrid work even more flexible. These are just a few trends that Harvard Business School faculty members will be following during a year when staffing, climate, and inclusion will likely remain top of mind.

- 12 Dec 2023

Can Sustainability Drive Innovation at Ferrari?

When Ferrari, the Italian luxury sports car manufacturer, committed to achieving carbon neutrality and to electrifying a large part of its car fleet, investors and employees applauded the new strategy. But among the company’s suppliers, the reaction was mixed. Many were nervous about how this shift would affect their bottom lines. Professor Raffaella Sadun and Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna discuss how Ferrari collaborated with suppliers to work toward achieving the company’s goal. They also explore how sustainability can be a catalyst for innovation in the case, “Ferrari: Shifting to Carbon Neutrality.” This episode was recorded live December 4, 2023 in front of a remote studio audience in the Live Online Classroom at Harvard Business School.

- 05 Dec 2023

Lessons in Decision-Making: Confident People Aren't Always Correct (Except When They Are)

A study of 70,000 decisions by Thomas Graeber and Benjamin Enke finds that self-assurance doesn't necessarily reflect skill. Shrewd decision-making often comes down to how well a person understands the limits of their knowledge. How can managers identify and elevate their best decision-makers?

- 21 Nov 2023

The Beauty Industry: Products for a Healthy Glow or a Compact for Harm?

Many cosmetics and skincare companies present an image of social consciousness and transformative potential, while profiting from insecurity and excluding broad swaths of people. Geoffrey Jones examines the unsightly reality of the beauty industry.

- 14 Nov 2023

Do We Underestimate the Importance of Generosity in Leadership?

Management experts applaud leaders who are, among other things, determined, humble, and frugal, but rarely consider whether they are generous. However, executives who share their time, talent, and ideas often give rise to legendary organizations. Does generosity merit further consideration? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Oct 2023

From P.T. Barnum to Mary Kay: Lessons From 5 Leaders Who Changed the World

What do Steve Jobs and Sarah Breedlove have in common? Through a series of case studies, Robert Simons explores the unique qualities of visionary leaders and what today's managers can learn from their journeys.

- 06 Oct 2023

Yes, You Can Radically Change Your Organization in One Week

Skip the committees and the multi-year roadmap. With the right conditions, leaders can confront even complex organizational problems in one week. Frances Frei and Anne Morriss explain how in their book Move Fast and Fix Things.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 01 Aug 2023

As Leaders, Why Do We Continue to Reward A, While Hoping for B?

Companies often encourage the bad behavior that executives publicly rebuke—usually in pursuit of short-term performance. What keeps leaders from truly aligning incentives and goals? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jul 2023

What Kind of Leader Are You? How Three Action Orientations Can Help You Meet the Moment

Executives who confront new challenges with old formulas often fail. The best leaders tailor their approach, recalibrating their "action orientation" to address the problem at hand, says Ryan Raffaelli. He details three action orientations and how leaders can harness them.

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Jun 2023

Every Company Should Have These Leaders—or Develop Them if They Don't

Companies need T-shaped leaders, those who can share knowledge across the organization while focusing on their business units, but they should be a mix of visionaries and tacticians. Hise Gibson breaks down the nuances of each leader and how companies can cultivate this talent among their ranks.

Four Steps to Building the Psychological Safety That High-Performing Teams Need

Struggling to spark strategic risk-taking and creative thinking? In the post-pandemic workplace, teams need psychological safety more than ever, and a new analysis by Amy Edmondson highlights the best ways to nurture it.

- 31 May 2023

From Prison Cell to Nike’s C-Suite: The Journey of Larry Miller

VIDEO: Before leading one of the world’s largest brands, Nike executive Larry Miller served time in prison for murder. In this interview, Miller shares how education helped him escape a life of crime and why employers should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance. Inspired by a Harvard Business School case study.

- 23 May 2023

The Entrepreneurial Journey of China’s First Private Mental Health Hospital

The city of Wenzhou in southeastern China is home to the country’s largest privately owned mental health hospital group, the Wenzhou Kangning Hospital Co, Ltd. It’s an example of the extraordinary entrepreneurship happening in China’s healthcare space. But after its successful initial public offering (IPO), how will the hospital grow in the future? Harvard Professor of China Studies William C. Kirby highlights the challenges of China’s mental health sector and the means company founder Guan Weili employed to address them in his case, Wenzhou Kangning Hospital: Changing Mental Healthcare in China.

- 09 May 2023

Can Robin Williams’ Son Help Other Families Heal Addiction and Depression?

Zak Pym Williams, son of comedian and actor Robin Williams, had seen how mental health challenges, such as addiction and depression, had affected past generations of his family. Williams was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a young adult and he wanted to break the cycle for his children. Although his children were still quite young, he began considering proactive strategies that could help his family’s mental health, and he wanted to share that knowledge with other families. But how can Williams help people actually take advantage of those mental health strategies and services? Professor Lauren Cohen discusses his case, “Weapons of Self Destruction: Zak Pym Williams and the Cultivation of Mental Wellness.”

- 11 Apr 2023

The First 90 Hours: What New CEOs Should—and Shouldn't—Do to Set the Right Tone

New leaders no longer have the luxury of a 90-day listening tour to get to know an organization, says John Quelch. He offers seven steps to prepare CEOs for a successful start, and three missteps to avoid.

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Research Support

- Stanford GSB Archive

Explore case studies from Stanford GSB and from other institutions.

Stanford GSB Case Studies

Other case studies.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2017

We generated a list of the 40 most popular Yale School of Management case studies in 2017 by combining data from our publishers, Google analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption. In compiling the list, we gave additional weight to usage outside Yale

We generated a list of the 40 most popular Yale School of Management case studies in 2017 by combining data from our publishers, Google analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption. In compiling the list, we gave additional weight to usage outside Yale.

Case topics represented on the list vary widely, but a number are drawn from the case team’s focus on healthcare, asset management, and sustainability. The cases also draw on Yale’s continued emphasis on corporate governance, ethics, and the role of business in state and society. Of note, nearly half of the most popular cases feature a woman as either the main protagonist or, in the case of raw cases where multiple characters take the place of a single protagonist, a major leader within the focal organization. While nearly a fourth of the cases were written in the past year, some of the most popular, including Cadbury and Design at Mayo, date from the early years of our program over a decade ago. Nearly two-thirds of the most popular cases were “raw” cases - Yale’s novel, web-based template which allows for a combination of text, documents, spreadsheets, and videos in a single case website.

Read on to learn more about the top 10 most popular cases followed by a complete list of the top 40 cases of 2017. A selection of the top 40 cases are available for purchase through our online store .

#1 - Coffee 2016

Faculty Supervision: Todd Cort

Coffee 2016 asks students to consider the coffee supply chain and generate ideas for what can be done to equalize returns across various stakeholders. The case draws a parallel between coffee and wine. Both beverages encourage connoisseurship, but only wine growers reap a premium for their efforts to ensure quality. The case describes the history of coffee production across the world, the rise of the “third wave” of coffee consumption in the developed world, the efforts of the Illy Company to help coffee growers, and the differences between “fair” trade and direct trade. Faculty have found the case provides a wide canvas to discuss supply chain issues, examine marketing practices, and encourage creative solutions to business problems.

#2 - AXA: Creating New Corporate Responsibility Metrics

Faculty Supervision: Todd Cort and David Bach

The case describes AXA’s corporate responsibility (CR) function. The company, a global leader in insurance and asset management, had distinguished itself in CR since formally establishing a CR unit in 2008. As the case opens, AXA’s CR unit is being moved from the marketing function to the strategy group occasioning a thorough review as to how CR should fit into AXA’s operations and strategy. Students are asked to identify CR issues of particular concern to the company, examine how addressing these issues would add value to the company, and then create metrics that would capture a business unit’s success or failure in addressing the concerns.

#3 - IBM Corporate Service Corps

Faculty Supervision: David Bach in cooperation with University of Ghana Business School and EGADE

The case considers IBM’s Corporate Service Corps (CSC), a program that had become the largest pro bono consulting program in the world. The case describes the program’s triple-benefit: leadership training to the brightest young IBMers, brand recognition for IBM in emerging markets, and community improvement in the areas served by IBM’s host organizations. As the program entered its second decade in 2016, students are asked to consider how the program can be improved. The case allows faculty to lead a discussion about training, marketing in emerging economies, and various ways of providing social benefit. The case highlights the synergies as well as trade-offs between pursuing these triple benefits.

#4 - Cadbury: An Ethical Company Struggles to Insure the Integrity of Its Supply Chain

Faculty Supervision: Ira Millstein

The case describes revelations that the production of cocoa in the Côte d’Ivoire involved child slave labor. These stories hit Cadbury especially hard. Cadbury's culture had been deeply rooted in the religious traditions of the company's founders, and the organization had paid close attention to the welfare of its workers and its sourcing practices. The US Congress was considering legislation that would allow chocolate grown on certified plantations to be labeled “slave labor free,” painting the rest of the industry in a bad light. Chocolate producers had asked for time to rectify the situation, but the extension they negotiated was running out. Students are asked whether Cadbury should join with the industry to lobby for more time? What else could Cadbury do to ensure its supply chain was ethically managed?

#5 - 360 State Real Options

Faculty Supervision: Matthew Spiegel

In 2010 developer Bruce Becker (SOM ‘85) completed 360 State Street, a major new construction project in downtown New Haven. Just west of the apartment building, a 6,000-square-foot pocket of land from the original parcel remained undeveloped. Becker had a number of alternatives to consider in regards to the site. He also had no obligation to build. He could bide his time. But Becker worried about losing out on rents should he wait too long. Students are asked under what set of circumstances and at what time would it be most advantageous to proceed?

#6 - Design at Mayo

Faculty Supervision: Rodrigo Canales and William Drentell

The case describes how the Mayo Clinic, one of the most prominent hospitals in the world, engaged designers and built a research institute, the Center for Innovation (CFI), to study the processes of healthcare provision. The case documents the many incremental innovations the designers were able to implement and the way designers learned to interact with physicians and vice-versa.

In 2010 there were questions about how the CFI would achieve its stated aspiration of “transformational change” in the healthcare field. Students are asked what would a major change in health care delivery look like? How should the CFI's impact be measured? Were the center's structure and processes appropriate for transformational change? Faculty have found this a great case to discuss institutional obstacles to innovation, the importance of culture in organizational change efforts, and the differences in types of innovation.

This case is freely available to the public.

#7 - Ant Financial

Faculty Supervision: K. Sudhir in cooperation with Renmin University of China School of Business

In 2015, Ant Financial’s MYbank (an offshoot of Jack Ma’s Alibaba company) was looking to extend services to rural areas in China by providing small loans to farmers. Microloans have always been costly for financial institutions to offer to the unbanked (though important in development) but MYbank believed that fintech innovations such as using the internet to communicate with loan applicants and judge their credit worthiness would make the program sustainable. Students are asked whether MYbank could operate the program at scale? Would its big data and technical analysis provide an accurate measure of credit risk for loans to small customers? Could MYbank rely on its new credit-scoring system to reduce operating costs to make the program sustainable?

#8 - Business Leadership in South Africa’s 1994 Reforms

Faculty Supervision: Ian Shapiro

This case examines the role of business in South Africa's historic transition away from apartheid to popular sovereignty. The case provides a previously untold oral history of this key moment in world history, presenting extensive video interviews with business leaders who spearheaded behind-the-scenes negotiations between the African National Congress and the government. Faculty teaching the case have used the material to push students to consider business’s role in a divided society and ask: What factors led business leaders to act to push the country's future away from isolation toward a "high road" of participating in an increasingly globalized economy? What techniques and narratives did they use to keep the two sides talking and resolve the political impasse? And, if business leadership played an important role in the events in South Africa, could they take a similar role elsewhere?

#9 - Shake Shack IPO

Faculty Supervision: Jake Thomas and Geert Rouwenhorst

From an art project in a New York City park, Shake Shack developed a devoted fan base that greeted new Shake Shack locations with cheers and long lines. When Shake Shack went public on January 30, 2015, investors displayed a similar enthusiasm. Opening day investors bid up the $21 per share offering price by 118% to reach $45.90 at closing bell. By the end of May, investors were paying $92.86 per share. Students are asked if this price represented a realistic valuation of the enterprise and if not, what was Shake Shack truly worth? The case provides extensive information on Shake Shack’s marketing, competitors, operations and financials, allowing instructors to weave a wide variety of factors into a valuation of the company.

#10 - Searching for a Search Fund Structure

Faculty Supervision: AJ Wasserstein

This case considers how young entrepreneurs structure search funds to find businesses to take over. The case describes an MBA student who meets with a number of successful search fund entrepreneurs who have taken alternative routes to raising funds. The case considers the issues of partnering, soliciting funds vs. self-funding a search, and joining an incubator. The case provides a platform from which to discuss the pros and cons of various search fund structures.

40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2017

Click on the case title to learn more about the dilemma. A selection of our most popular cases are available for purchase via our online store .

- Magazine Issues

- Magazine Articles

- Online Articles

- Training Day Blog

- Whitepapers

- L&D Provider Directory

- Artificial Intelligence

- Employee Engagement

- Handling Customer Complaints

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Leadership Development Case Studies

- Positive Relationships

- Teams and Teambuilding

- Awards Overview

- Training APEX Awards

- Emerging Training Leaders

- Training Magazine Network Choice Awards

- Online Courses

- Training Conference & Expo

- TechLearn Conference

- Email Newsletter

- Advertising

Leadership Case Studies

Here is a sample of three case studies from the book, Leadership Case Studies, that are most instructive and impactful to developing leadership skills.

For the past 30 years, I have conducted seminars and workshops and taught college classes on leadership.

I used a variety of teaching aids including books, articles, case studies, role-plays, and videos.

I recently created a book, Leadership Case Studies that includes some of the case studies and role-plays that I found to be most instructive and impactful.

Here is a sample of three case studies.

Peter Weaver Case Study

Peter Weaver doesn’t like to follow the crowd. He thinks groupthink is a common problem in many organizations. This former director of marketing for a consumer products company believes differences of opinion should be heard and appreciated. As Weaver states, “I have always believed I should speak for what I believe to be true.”

He demonstrated his belief in being direct and candid throughout his career. On one occasion, he was assigned to market Paul’s spaghetti-sauce products. During the brand review, the company president said, “Our spaghetti sauce is losing out to price-cutting competitors. We need to cut our prices!”

Peter found the courage to say he disagreed with the president. He then explained the product line needed more variety and a larger advertising budget. Prices should not be cut. The president accepted Weaver’s reasoning. Later, his supervisor approached him and said, “I wanted to say that, but I just didn’t have the courage to challenge the president.”

On another occasion, the president sent Weaver and 16 other executives to a weeklong seminar on strategic planning. Weaver soon concluded the consultants were off base and going down the wrong path. Between sessions, most of the other executives indicated they didn’t think the consultants were on the right path. The consultants heard about the dissent and dramatically asked participants whether they were in or out. Those who said “Out” had to leave immediately.

As the consultants went around the room, every executive who privately grumbled about the session said “In.” Weaver was fourth from last. When it was his turn, he said “Out” and left the room.

All leaders spend time in reflection and self-examination to identify what they truly believe and value. Their beliefs are tested and fine-tuned over time. True leaders can tell you, without hesitation, what they believe and why. They don’t need a teleprompter to remind them of their core beliefs. And, they find the courage to speak up even when they know others will disagree.

- What leadership traits did Weaver exhibit?

- If you were in Weaver’s shoes, what would you have done?

- Where does courage come from?

- List your three most important values.

Dealing with a Crisis Case Study

Assume you are the VP of Sales and Marketing for a large insurance company. Once a year your company rewards and recognizes the top 100 sales agents by taking them to a luxury resort for a four-day conference. Business presentation meetings are held during the morning. Afternoons are free time. Agents and spouses can choose from an assortment of activities including golf, tennis, boating, fishing, shopping, swimming, etc.

On day 2 at 3:00 p.m., you are at the gym working out on the treadmill, when you see Sue your administrative assistant rushing towards you. She says, “I need to talk to you immediately.”

You get off the treadmill and say, “What’s up?” Sue states, “We’ve had a tragedy. Several agents went boating and swimming at the lake. Randy, our agent from California died while swimming.”

(Background information – Randy is 28 years old. His wife did not come on the trip. She is home in California with their three children).

- Explain what you would communicate to the following people.

- Your Human Resources Department

- The local police

- The attendees at the conference (Would you continue the conference?)

- How will you notify Randy’s wife?

- If Randy’s wife and a few family members want to visit the location of Randy’s death, what would you do?

- What are some “guiding principles” that leaders need to follow in a crisis situation?

Arsenic and Old Lace Case Study

Review the YouTube video, “ I’ll show them who is boss Arsenic and Old Lace.”

Background Information

The Vernon Road Bleaching and Dyeing Company is a British lace dyeing business. It was purchased in bankruptcy by the father/son team of Henry and Richard Chaplin. Richard has been acting as “Managing Director” which is the same as a general manager or president of a company.

The company has had 50-to-150 employees with 35-to-100 being shop floor, production employees. The company produces and sells various dyed fabrics to the garment industry.

Gerry Robinson is a consultant who was asked to help transform methods of conducting business to save the company.

Jeff is the factory manager.

- What are Richard’s strengths and weaknesses as a leader?

- What could Richard have done to make the problems of quality and unhappy customers more visible to the workforce?

- What do you think Richard’s top three priorities should be for the next 12 months?

- What could Richard have done to motivate the workforce?

- Evaluate Jeff’s approach and effectiveness as a leader.

The book contains 16 case studies, four role-plays, and six articles. I hope you find some of the content useful and helpful in your efforts to teach leadership.

Click for additional leadership case studies and resources .

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

How to Use Outsourcing as a Lever for DE&I

Nurturing Talent in the Modern Workforce

Training apex awards best practice: two men and a truck’s b2b initiatives program, online partners.

Vote today for your favorite L&D vendors!

The Ethical Leadership Case Study Collection

The Ted Rogers Leadership Centre’s Case Collection, developed in collaboration with experienced teaching faculty, seasoned executives, and alumni, provides instructors with real-life decision-making scenarios to help hone students’ critical-thinking skills and their understanding of what good leaders do. They will be able to leverage the theories, models, and processes being advanced. Students come to understand that workplace dilemmas are rarely black and white, but require them to think through and address competing claims and circumstances. Crucially, they also appreciate how they can, as new leaders and middle managers, improve decisions by creating realistic action plans based on sound stakeholder analysis and communication principles. These case studies are offered free of charge to all instructors.

Cases come in both long and short forms. The long cases provide instructors with tools for delving deeply into subjects related to a variety of decision making and organizational development issues. The short cases, or “minis,” are quick in-class exercises in leadership.

For both the long cases and the minis, teaching-method notes are provided, which include not only recommended in-class facilitation methods, but also grading rubrics, references, and student feedback.

Testimonials

“I have been invited to judge the Leadership Centre’s Annual Ethical Leadership National Case Competition since its inception. Each year, competitors are given a Centre’s case to analyze and present. These cases are like nothing else. They bring the student into the heart of the situation. To excel, students must not only be able to cogently argue the options, but also demonstrate how to implement a decision based on a clear-eyed stakeholder analysis and an understanding of the dynamics of change.” Anne Fawcett, Special Advisor, Caldwell Partners

“I have worked with the Ted Rogers Leadership Centre to both develop and pilot test case materials. Feedback consistently shows that the Centre’s cases resonate with students, providing them with valuable learning experiences.” Chris Gibbs, BComm, MBA, PhD, Associate Professor

"As a judge in the recent national Ted Rogers Ethical Leadership Case Competition, I was very impressed with the quality of the case study prepared by the Leadership Centre. It was brief but well-composed. It exposed the students to ethical quandaries, of the sort they may well face in their business careers. It not only tested their reasoning, but it challenged them to develop a plan of action when faced with incomplete information and imminent deadlines.” Lorne Salzman, Lawyer

We value your feedback

Please inform us of your experience by contacting Dr. Gail Cook Johnson, our mentor-in-residence, at [email protected] .

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Teaching Resources Library

Case studies.

The teaching business case studies available here are narratives that facilitate class discussion about a particular business or management issue. Teaching cases are meant to spur debate among students rather than promote a particular point of view or steer students in a specific direction. Some of the case studies in this collection highlight the decision-making process in a business or management setting. Other cases are descriptive or demonstrative in nature, showcasing something that has happened or is happening in a particular business or management environment. Whether decision-based or demonstrative, case studies give students the chance to be in the shoes of a protagonist. With the help of context and detailed data, students can analyze what they would and would not do in a particular situation, why, and how.

Case Studies By Category

2022 Impact Factor

- About Publication Information Subscriptions Permissions Advertising Journal Rankings Best Article Award Press Releases

- Resources Access Options Submission Guidelines Reviewer Guidelines Sample Articles Paper Calls Contact Us Submit & Review

- Browse Current Issue All Issues Featured Latest Topics Videos

California Management Review

California Management Review is a premier academic management journal published at UC Berkeley

CMR INSIGHTS

Are we asking too much leadership from leaders.

by Herman Vantrappen and Frederic Wirtz

Image Credit | Nick Fewings

Leaders do not have an easy time. In the assumption that the headlines in the management literature are a reliable guide, leaders are expected not only to be brilliant but also servant, humble, transformational, vulnerable, authentic, emotionally intelligent, empathetic, unlocked and connecting – at the least. 1-9 That is a tall order, even for those who are labelled superhuman.

Related CMR Articles

“Transformational Leader or Narcissist? How Grandiose Narcissists Can Create and Destroy Organizations and Institutions” by Charles A. O’Reilly & Jennifer A. Chatman

Fortunately, leaders may not need to take all those exhortations too serious, or certainly not too literal. To begin with, some scholars warn of the shaky grounds of several leadership constructs. For example, Katja Einola et al. point to authentic leadership theory as an example of a “dysfunctional family of positive leadership theories celebrating good qualities in a leader linked with good outcomes and positive follower ‘effects’ almost by definition.” 10 They add that leadership studies should “raise the bar for what academic knowledge work is and better distinguish it from pseudoscience, pop-management, consulting, and entertainment.” Ouch!

Other scholars are adding precautions about the potentially detrimental effects of certain leader behaviors both for the leaders themselves and for the organizations they lead. For example, Joanna Lin et al. point to leader emotional exhaustion resulting from transformational leader behavior. 11 Charles O’Reilly et al. warn of the substantial overlaps of transformational leadership with grandiose narcissism. 12

Still other scholars emphasize that leadership skills are context-specific. For example, Raffaella Sadun emphasizes that the most effective leaders have social skills that are specific to their company and industry. 13 Nitin Nohria points out that charisma often is a liability, yet charismatic leaders can be especially useful at entrepreneurial startups and in corporate turnarounds. 14 Jasmin Hu et al. indicate that humble leaders are effective only when their level of humility matches to what team members expect. 15

The above tells us two things, whether we are a leader or a follower. First, the pertinence of a particular leader behavior depends on the situation. Second, we should temper our expectations of the effect of that behavior. But even then, the question remains: Are we demanding too much from leaders? The answer is nuanced: No, we cannot demand too much; but the real question is how we could lessen the need for those demands to emerge in the first place.

Reading the definitions of those leader behaviors, it would be hard to argue we are demanding too much. Just consider the following examples:

- Servant leaders “place the needs of their subordinates before their own needs and center their efforts on helping subordinates grow.” 1

- Humble leaders “are willing to admit it when they make a mistake, they recognize and acknowledge the skills of those they lead, and they continuously seek out opportunities to become better.” 16

- Vulnerable leaders “intentionally open themselves up to the potential of emotional harm while taking action (when possible) to create a positive outcome.” 4

- Emotionally intelligent leaders “are conscious about and responsive to their emotions, possessing the ability to harness and control them in order to deal with people effectively and make the best decisions.” 17

- Empathetic leaders “genuinely care for people, validate their feelings, and are willing to offer support.” 7

- Connecting leaders “concurrently contend with identities, actions, emotions of a leader and a follower.” 9

While these demands on leaders are pertinent, they are also taxing in terms of time and energy. To solve the quandary, we should look for ways to lessen the need for those demands to emerge in the first place. On many occasions, leaders at the top are led to activate the afore-mentioned behaviors because doubts, disagreements, tensions, trade-offs and eventually conflicts by and between people in the field are allowed to escalate. These frictions may emerge and escalate to the top for all kinds of reasons but they often land there due to organizational design faults: Some designs are intrinsically frictional; others lack mechanisms to resolve friction at origin. Precluding these design faults requires craftsmanship in organization design.

Let us take a stylized example. Laura is the commercial manager in charge of the Brazil region at Widget Inc. As sales this year are going more slowly than planned, she is desperately trying to win a specific new client. To have any chance of winning, she must be able to offer a special off-catalogue product. So she turns to Lucas, the global manager in charge of the product line concerned, who unfortunately has to tell her that the manufacturing plant is fully booked for the next six months, leaving no capacity for the mandatory testing of the special product for her client in Brazil. Tension rises, and the issue escalates to their respective bosses, the EVP Regions and the EVP Products. Unfortunately, these two do not manage to agree on a solution either. Even worse, the incident degenerates into an acrimonious confrontation at the company’s next executive team meeting, where the two blame each other for a chronic lack of flexibility.

The originally operational issue thus lands with a thick thud on the CEO’s desk. After suppressing a deep sigh, she activates various leader behaviors. She is empathetic (“I sense how strongly you both feel about this important matter …”), servant (“I don’t blame you for bringing this to my attention …”), humble (“I realize I should have put in place a way of preventing issues like this …”), vulnerable (“In fact, I once struggled myself with a similar issue …”), and more…

The CEO may be doing all the right things at that moment, but could she have been spared the onus of dealing with the originally operational friction if only the company’s organization had been designed differently? Widget Inc.’s organization architecture features two equally-weighted primary verticals, i.e., “region” and “product”, both having full P&L responsibility, hence competing with each other directly for resources, decision power and attention. While there is no general rule that such an architecture must not be chosen, in general it tends to be an intrinsically frictional design.

The general message for leaders is: When you seek remedies for pain points in your organization, do not count on leader behavior only, but check also for architectural design faults or ambiguities. Here are three examples, each linked to a variable that defines an organization’s architecture.

1. The primary vertical

Small mono-product and mono-market companies tend to have a function-based architecture (e.g., product development, purchasing, production, sales, distribution, after-sales). At large companies, that architecture can be intrinsically frictional. For example, if you are in the business of developing, constructing and maintaining power plants worldwide, the business development people, when they make a bid, might be tempted to foresee low maintenance costs so as to increase their chances of winning the bid. Alas, if the bid is won, the maintenance division will bear the brunt. Such operational tension is inherent to this type of business, but you do not want that tension to constantly manifest itself at the C-suite level. Therefore, consider having “region” rather than “function” as primary vertical and then setting up a function-based organization within each region. 18

2. The corporate parent

Each of a company’s business entities has specific objectives, challenges and priorities. Imagine your company has a mix of large businesses operating in its mature home market and small ventures in promising overseas markets. The latter may be keen to tap into the talent and knowledge that reside in the former, while the former may be reluctant to lend to the latter. Obviously, you do not want every such request and refusal to be elevated to the C-suite level. A global knowledge management and talent mobility system could solve the problem, and you might expect the businesses, out of enlightened self-interest, to set it up among themselves. Alas, that is unlikely to happen, as the benefits are contingent on participation by all businesses. Therefore, consider having a corporate function kick-start the initiative. 19

3. Lateral coordination

Imagine that your organization architecture consists of business entities focused on “product” and others on “customer segment”. Even though these entities by design are relatively self-contained, “product” and “customer segment” still need to coordinate daily on operational matters, such as defining product specs, setting price levels, launching commercial campaigns, etc. Hence you decide to create a matrix, with sales managers reporting both to a product line manager and a customer segment manager. And you expect these matrixed sales managers to make the best possible trade-offs between the partially diverging interests of their two bosses. Alas, a matrix between two verticals with P&L responsibility tends to be intrinsically frictional. 20 The matrixed manager’s anxiety about role conflict and their bosses’ fear of power loss may create festering conflicts escalating to the C-suite level. Therefore, in this case, consider a soft-wired coordination mechanism (such as a periodic joint planning cycle) instead of a hard-wired matrix.

There are many other examples of organization design faults or ambiguities, not only related to organizational architecture but also to governance, business processes, company culture, people and systems. Admittedly, the perfect organization design does not exist – tension and friction are a fact of corporate life. And we could hardly demand too much authenticity, emotional intelligence, empathy and other commendable behaviors from our leaders, as described at start. But there is an issue when senior leaders are compelled to activate these behaviors to resolve internal conflicts that should not have escalated to the top of the organization. By identifying and removing glaring design faults and ambiguities about roles, we can help lessen the emergence and escalation of such conflicts, and consequently reduce the opportunity cost of senior leaders devoting energy and time to resolving stoppable conflicts. Senior leaders had better focus on genuine people issues, external stakeholders, and the organization’s strategic choices.

References

R.C. Liden, S.J. Wayne, H. Zhao and D. Henderson, “Servant Leadership: Development of a Multidimensional Measure and Multi-Level Assessment,” The Leadership Quarterly 19, no. 2 (2008): 161-177..

E.H. Schein and P.A. Schein, “Humble Leadership: The Power of Relationships, Openness, and Trust,” 2nd ed. (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2018).

B.M. Bass, “Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1985).

J. Morgan, “Leading with Vulnerability: Unlock Your Greatest Superpower to Transform Yourself, Your Team, and Your Organization” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2023).

B. George, “Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value” (New York: Jossey-Bass, 2004).

D. Goleman, “The Emotionally Intelligent Leader” (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2019).

O. Valadon, “What We Get Wrong About Empathic Leadership,” Harvard Business Review, Oct. 17, 2023.

H. Le Gentil, “The Unlocked Leader: Dare to Free Your Own Voice, Lead with Empathy, and Shine Your Light in the World” (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2023).

“The Connecting Leader: Serving Concurrently as a Leader and a Follower,” ed. Z. Jaser (Charlotte: IAP, 2021).

K. Einola and M. Alvesson, “The Perils of Authentic Leadership Theory,” Leadership 17, no. 4 (2021): 483-490.

J. Lin, B.A. Scott and F.K. Matta, “The Dark Side of Transformational Leader Behaviors for Leaders Themselves: A Conservation of Resources Perspective,” Academy of Management Journal 62, no. 5 (2019): 1556-1582.

C.A. O’Reilly and J.A. Chatman, “Transformational Leader or Narcissist? How Grandiose Narcissists Can Create and Destroy Organizations and Institutions,” California Management Review 62, no. 3 (2020): 5-27.

R. Sadun, “The Myth of the Brilliant, Charismatic Leader,” Harvard Business Review, Nov. 23, 2022.s

N. Nohria, “When Charismatic CEOs Are an Asset — and When They’re a Liability,” Harvard Business Review, Dec. 1, 2023.

J. Hu, B. Erdogan, K. Jiang and T.N. Bauer, “Research: When Being a Humble Leader Backfires,” Harvard Business Review, April 4, 2018.

T.K. Kelemen, S.H. Matthews, M.J. Matthews and S.E. Henry, “Essential Advice for Leaders from a Decade of Research on Humble Leadership,” LSE Business Review, Jan. 17, 2023.

S.T.A. Phipps, L.C. Prieto and E.N. Ndinguri, “Emotional Intelligence: Is It Necessary for Leader Development?” Journal of Leadership, Accountability & Ethics 11, no.1 (2014): 73-89.

H. Vantrappen and F. Wirtz, “When to Change Your Company’s P&L Responsibilities,” Harvard Business Review, April 14, 2022.

H. Vantrappen and F. Wirtz, “How To Get a Corporate Parent That Is Better For Business,” California Management Review, March 5, 2024.

J. Wolf and W.G. Egelhoff, “An Empirical Evaluation of Conflict in MNC Matrix Structure Firms,” International Business Review 22, no. 3 (2013): 591-601.

Recommended

Current issue.

Volume 66, Issue 2 Winter 2024

Recent CMR Articles

The Changing Ranks of Corporate Leaders

The Business Value of Gamification

Hope and Grit: How Human-Centered Product Design Enhanced Student Mental Health

Four Forms That Fit Most Organizations

Dynamic Capabilities and Organizational Agility

Berkeley-Haas's Premier Management Journal

Published at Berkeley Haas for more than sixty years, California Management Review seeks to share knowledge that challenges convention and shows a better way of doing business.

- Study Guides

- Homework Questions

Journal of Business and Administrative Studies Journal / Journal of Business and Administrative Studies / Vol. 13 No. 2 (2021) / Articles (function() { function async_load(){ var s = document.createElement('script'); s.type = 'text/javascript'; s.async = true; var theUrl = 'https://www.journalquality.info/journalquality/ratings/2404-www-ajol-info-jbas'; s.src = theUrl + ( theUrl.indexOf("?") >= 0 ? "&" : "?") + 'ref=' + encodeURIComponent(window.location.href); var embedder = document.getElementById('jpps-embedder-ajol-jbas'); embedder.parentNode.insertBefore(s, embedder); } if (window.attachEvent) window.attachEvent('onload', async_load); else window.addEventListener('load', async_load, false); })();

Article sidebar.

Article Details

Main article content, organizational risk management practices in time of crisis: an exploratory case study of ethiopian airlines in the corona virus pandemic, g. nekerwon gweh, dejene mamo.

The purpose of this investigative case study research was to scrutinize the approaches of organizational risk management strategies applied by the Ethiopian Airlines throughout the global COVID-19 pandemic. It aimed at assessing and documenting risk management methodologies, best practices and lessons learned by the Airlines to survive the damaging impact the health crisis. The researcher limited the participants to six senior and middle level staff who are responsible to handle the Airlines risk management operations and the project management departments. The Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) and the Team Leadership Model (TLM) were the conceptual frameworks used as the basis for this study. Data triangulation was used to support the review and analysis of data gathered from various sources. Data analysis methods in conjunction with the NVivo software were used to support the identification of core themes. Situation Awareness and Decision Making, Leadership Presence Strategy, Strategic Internal Communication and Transparent Public Communication were the themes identified. A fundamental finding from the study revealed that Ethiopian Airlines’ Strategic Business Plan calls for the establishment of “multi-business units” as a key principle. This is seen in how the company has diversified its operations into tourism, hospitality and Aviation trainings in addition to the original passenger and cargo services it offers as an airline.

AJOL is a Non Profit Organisation that cannot function without donations. AJOL and the millions of African and international researchers who rely on our free services are deeply grateful for your contribution. AJOL is annually audited and was also independently assessed in 2019 by E&Y.

Your donation is guaranteed to directly contribute to Africans sharing their research output with a global readership.

- For annual AJOL Supporter contributions, please view our Supporters page.

Journal Identifiers

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

Crisis Leadership Lessons from Polar Explorer Ernest Shackleton

Discover lessons in building a team, learning from bad bosses, and cultivating empathy.

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

In early 1915, polar explorer Ernest Shackleton’s ship became trapped in ice, north of Antarctica. For almost two years, he and his crew braved those frozen expanses. Then, in December 1916, Shackleton led them all to safety.

Not a single life was lost, and Shackleton’s leadership has become one of the most famous case studies of all time.

In this episode, Harvard Business School professor and historian Nancy Koehn analyzes Shackleton’s leadership during those two fateful years that he and his men struggled to survive.

She explains how Shackleton carefully assembled a team capable of weathering a crisis and the important role empathy played in his day-to-day leadership. Koehn also shares the survival lessons that Shackleton learned from weak leaders he encountered early in his own career.

Key episode topics include: leadership, crisis management, motivating people, managing people.

HBR On Leadership curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock the best in those around you. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the original HBR IdeaCast episode: Real Leaders: Ernest Shackleton Leads a Harrowing Expedition (2020)

- Find more episodes of HBR IdeaCast

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR on Leadership , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock the best in those around you.

In early 1915, polar explorer Ernest Shackleton’s ship became trapped in ice, north of Antarctica. For almost two years, he and his crew braved those frozen expanses until Shackleton led them to safety in December 1916. Not a single life was lost, and Shackleton’s leadership has become one of the most famous case studies of all time.

In this episode, Harvard Business School professor and historian Nancy Koehn analyzes Shackleton’s leadership during those two fateful years that he and his men struggled to survive.

You’ll learn how to assemble a team capable of weathering a crisis, the lessons that Shackleton learned from bad leaders in his early career, and the important role empathy played in his own, leadership.

This episode originally aired on HBR IdeaCast in March 2020. Here it is.

ADI IGNATIUS: Welcome to the HBR IdeaCast from Harvard Business Review. I’m Adi Ignatius. This is Real Leaders , a special series that examines the lives of some of the world’s most compelling and effective leaders, past and present and offers lessons to all of us today.

NANCY KOEHN: Wanted, men for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful, honor and recognition in case of success.

ADI IGNATIUS: Legend has it that that’s the job and Ernest Shackleton used to recruit the crew for his expedition to Antarctica in 1914. If you know this story you know that Shackleton and his crew never set foot on that continent. Instead, their ship got trapped in ice. But it’s what happened when their original mission failed that has made Shackleton’s remarkable story of survival, one of the most famous case studies in leadership history. I’m Adi Ignatius, Editor in Chief of Harvard Business Review and I’m joined by historian and Harvard Business School Professor Nancy Koehn. Nancy’s case study about Ernest Shackleton is a classic and her book, Forged in Crisis , is a great account of Shackleton’s story. Nancy welcome.

NANCY KOEHN: Thank you, Adi. It’s a pleasure to be here.

ADI IGNATIUS: We’re starting this series with Ernest Shackleton, one of the great explorers in the age of polar exploration in the early 20th Century. To set the context in the U.S., Teddy Roosevelt is President. Ford Motor Company has just produced its first car and the race to discover the South Pole is on. So, to understand the context even more, Nancy, is this kind of the equivalent of the Space Race of the 1960s?

NANCY KOEHN: Absolutely. It’s a great analogy. It was a time when nations and patriotism were duking it out at some level in an international race, along exploration lines.

ADI IGNATIUS: So, Shackleton’s first expedition to Antarctica takes place in 1902. So, Nancy, what happened in that?

NANCY KOEHN: So, his first expedition which happens in the very first few years of the 20th Century, is an expedition under the command of a Naval Officer named Robert Falcon Scott. They’re trying to be the first to the Pole and that expedition goes terribly awry and Scott is forced to turn around and go back and they almost die on the way back for a number of reasons, primarily the most important of which is the temperatures and food supplies.

ADI IGNATIUS: OK. So, this fails, but Shackleton wants more. He goes back.

NANCY KOEHN: He wants more. When Scott publishes an account of the expedition that’s scathing toward Shackleton, that gets his dander up and he immediately begins planning for his own expedition. Having learned a lot of things from Scott that he thinks he won’t do.

ADI IGNATIUS: OK. So, here’s lesson number one. What do you do when you have a bad boss? I mean, to what extent does he learn lessons from an initial foray gone badly?

NANCY KOEHN: Extremely important lessons. One, make your decisions and stick with them. That’s something Scott has a lot of trouble with. And a lot of those decisions in leadership involve displeasing or not making everyone happy. That’s a second related lesson. Third lesson: make sure you have adequate food supplies and transport that you can depend on. He wasn’t a very good process engineer and planner. And so Shackleton learns from that and says I’m going to be very good about that. I’m never going to be in charge of an expedition that runs short on food supplies. Again, almost in intentional opposition to Scott. So, what’s important I think here for our time and for all of us that have worked for bad bosses or people we don’t agree with or people we feel frustrated by is what can I learn from this person about how I will not act as a manager and a leader.

ADI IGNATIUS: So Shackleton leads his own expedition to the South Pole in 1907. That fails to reach the South Pole. So, 1914 he returns to Antarctica for his third mission and this is the one that becomes so famous. So it’s interesting to think about Shackleton almost as an entrepreneur. He takes on some of the tasks that are at once both profound, but also mundane. Hiring a team, raising money. I think particularly the way in which he built his team is remarkable and weird and instructive.

NANCY KOEHN: That is exactly, that’s a great set of descriptives. So Shackleton didn’t use this language, but here’s what he did and I’ll say a word about how. He hired for attitude and trained for skill. That’s the essence of what he did. So, less about what have you got on your resume that makes you look like you’d be a good polar scientist, or a good polar navigator and more about what’s your attitude and how, what has that attitude affect your ability to deal with these very high-risk situations? So, the way he gets to attitude in the hiring process is he asks people to do things like sing a song. Do a dance. He tries to get at their underlying default kind of character, am I pessimistic, am I optimistic? How do I deal with different kinds of situations?

ADI IGNATIUS: So, was he hiring people who pleased him, or do you think he really was thinking at that high level about these attributes?

NANCY KOEHN: Absolutely the latter. Absolutely thinking about what have I got here? What have I got in this scientist? What have I got in this doctor? What have I got in this enlisted man? What kind of attitudes do I have? How are they suited to the environment that I know well in Antarctica? He’s knows it, he’s been there with good and bad and less good results. And very importantly, not just what attitudes, what collection of attitudes do I have, but how do they fit together? He was a brilliant kind of conductor if you will, of teams. Because teams aren’t just kind of set of resumes you’ve got. They’re the people and their attitudes and their experience, and how they work together. So, he was very careful about choosing his ensemble.

ADI IGNATIUS: When I interview people should I have them tell me a joke and sing a little song and just get a sense of their ability to respond to a weird request?

NANCY KOEHN: Absolutely. That’s exactly what he’s doing. That’s a very good way of characterizing it. You can also ask them, you know, when you hire people about what was their most confusing? What was their most, what was their greatest moment of self-doubt? Shackleton got that kind of thing as well. And he understood it long before we were writing about it here at places like the Harvard Business School.

ADI IGNATIUS: So, by now Shackleton has his team for the Endurance mission assembled. Now what happens first?

NANCY KOEHN: So, he sets off in August 1914 almost exactly at the time that World War I breaks out. And he has to ask the Assistant Lord of the Navy, Winston Churchill if he can go ahead and go or if they need the ship and the men for military service, and Churchill says, “Proceed.” And Shackleton hightails it out of Dodge and gets himself down, first to South America to take on supplies and then they head south and east to a small whaling station, this is their last outpost before they get to Antarctica, the continent. And the whalers say to Shackleton, “The icebergs are very far north this year and you’re going to have trouble getting through the jigsaw puzzle ice going down there.”

ADI IGNATIUS: Remember we’re heading south.

NANCY KOEHN: We’re heading south. And Shackleton waits a month, waiting for the ice to kind of clear and it doesn’t, and he sets off. He was arguably reckless, or a little bit cavalier. Maybe a little bit more than a little, but he heads south. They make their way through these, and there’s astounding pictures of this, through this jigsaw puzzle of ice to the coast of Antarctica. And in January. So, they left in August. In January, late January, just as they see the coast of Antarctica, but as they’re still 80 miles away, icebergs lock the ship in a vice. Tons and tons and tons of ice locking it in place. No one knows where they are. The radio doesn’t work. After a month or so it’s really clear that they’re not going to break free of the ice. They have to wait for it to melt, and if the ship survives being held in a vice that long, there’s very, if it survives they may get back to the coast, but he thinks increasingly as the days becomes weeks and the weeks become months into 1915, that their expedition is over. So very interesting leadership moment. I can’t get to my original goal. What in the heck do I do? And that is a very interesting pivot moment for Shackleton.

ADI IGNATIUS: We’re talking months and months locked in the ice, freezing temperature, no light at times. I mean it’s sort of unfathomable. It doesn’t even kind of register in today’s terms.